The economy is performing well with strong economic growth and a tightening labour market. The near-term outlook remains positive but risks and uncertainty are high. On the other hand, population ageing will lead to a smaller and older work force, which means that sustaining economic growth and income convergence will increasingly rely on improving labour allocation, raising human capital and facilitating the adoption of new technologies, and in particular digitalisation. In addition, rising ageing-related public spending pressures threaten fiscal sustainability, while problems of access and adequacy issues need to be addressed in the health and pension systems.

OECD Economic Surveys: Slovenia 2022

1. Key Policy Insights

Abstract

The recovery continues but is subject to high uncertainty

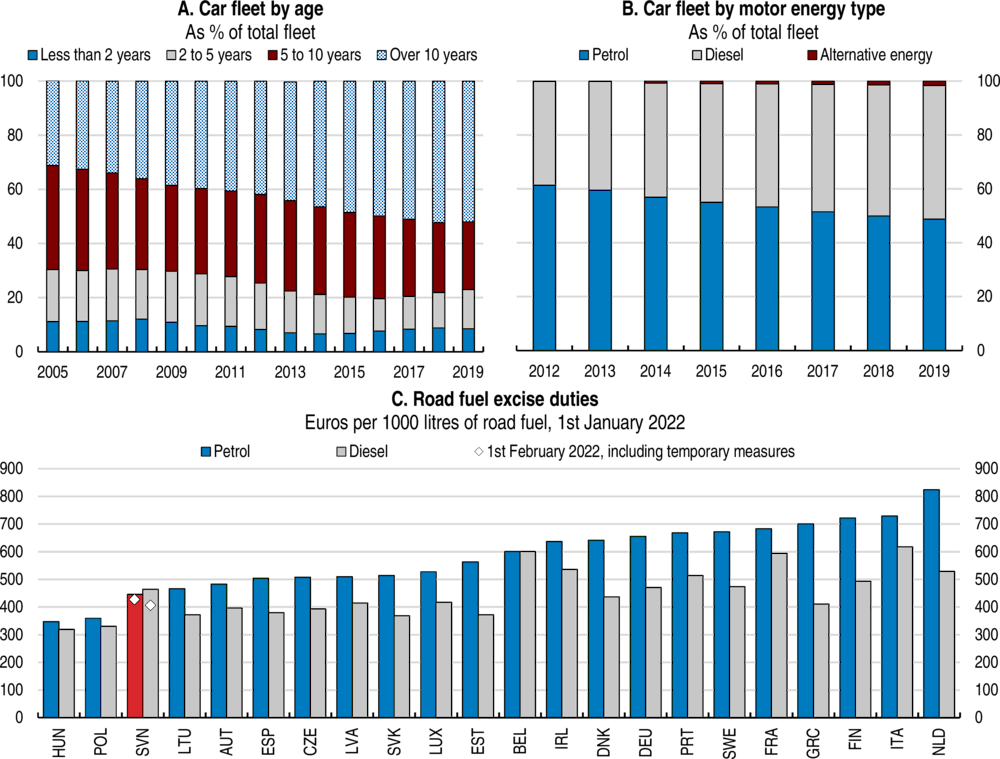

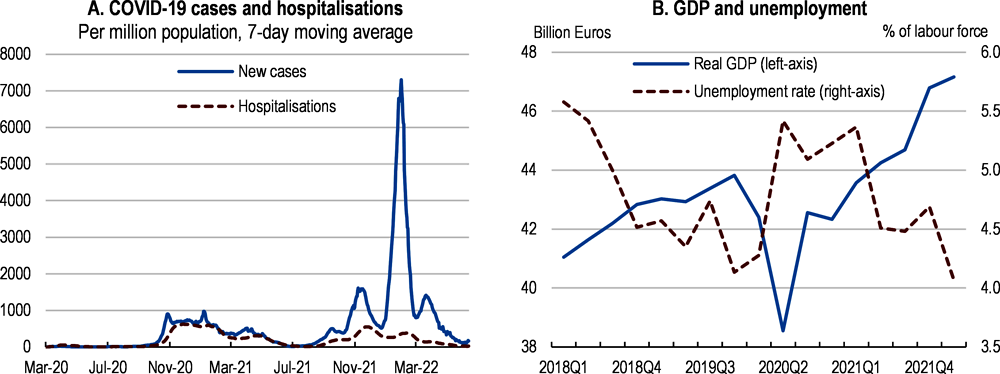

The war in Ukraine interrupted the strong post-pandemic recovery, although headwinds in the form of international supply chain bottlenecks and higher energy prices were building up. Until then, economic activity surpassed its pre-pandemic levels in 2021. The labour market performance was strong with historically high employment and a low unemployment rate (Figure 1.1). At the beginning of 2022, wage growth slowed, reflecting the withdrawal of pandemic-related one-off government measures. Nonetheless, the tight labour market is expected to put pressures on wages throughout 2022 and 2023. Together with high food and energy prices, this will keep headline inflation elevated. The pace and strength of the recovery remain subject to considerable uncertainty, related to the impacts of the war in Ukraine. The conflict could create an energy crisis, which together with stronger wage growth could fuel a further rise in inflation expectations.

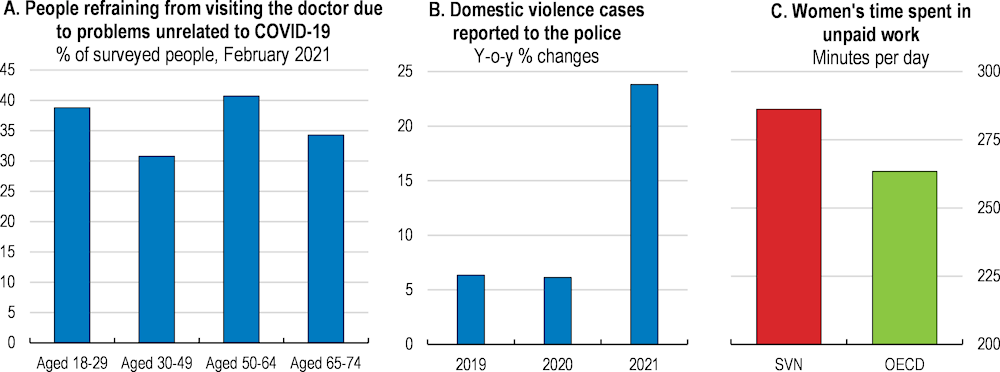

Figure 1.1. The COVID-19 pandemic had severe health and economic impacts

Source: OECD calculations based on Ourworldindata; and OECD Economic Outlook: Statistics and Projections database.

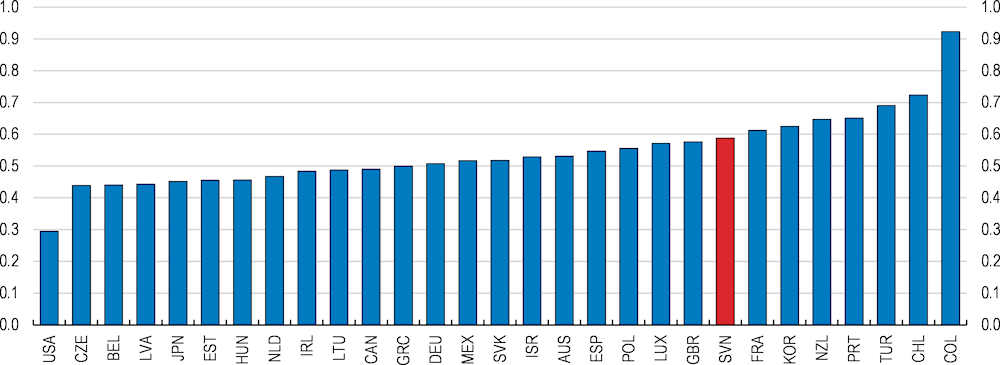

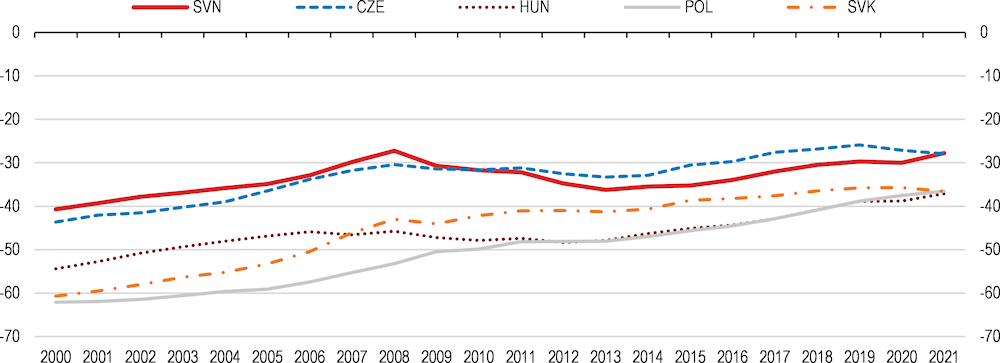

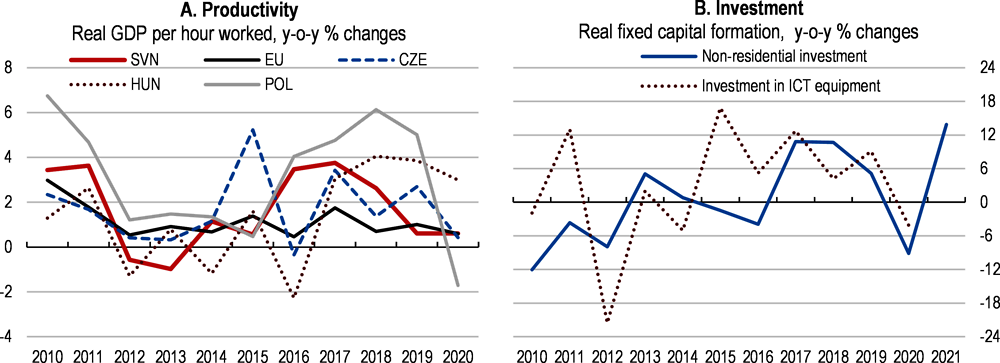

Income continued to converge towards richer OECD members (Figure 1.2). This reflected mostly strong employment increases, whereas the contribution from higher real wages was lower than in other Central and Eastern European economies. Growth was initially supported by faster productivity growth in 2016-2018, but productivity growth slowed prior to the pandemic. Vacancies were mostly filled through migration while potential domestic labour resources remained underutilised as reflected in the low labour force participation of people older than 60.

The COVID-19 pandemic has entailed large social costs, whose effects are still unfolding, as the pandemic has assumed a syndemic relevance, through the impact on social, economic, and psychological aspects of people’s lives. According to the regularly conducted COVID-19 survey of the National Institute of Public Health, young people experienced a particularly large deterioration in their financial situation, likely related to the increase in youth unemployment (see below) (NIJZ, 2021[1]). More generally, financial security was among the most negatively affected areas during the pandemic. Those reporting a worse financial situation were also more likely to report mental health issues, with the share of persons reporting symptoms of anxiety and depression being highest among the 18-29 age group (NIJZ, 2021[2]).

Figure 1.2. Incomes are catching up

GDP per capita gaps to the upper half of OECD countries. Upper half is weighted by the population, % difference

Source: OECD National Accounts database; OECD Economic Outlook: Statistics and Projections database; and OECD calculations.

In 2020, the overall share of people at risk of poverty or social exclusion increased. This was particularly observed for the most disadvantaged groups, such as those with lower education, one-member households and retired women, but also, to a lesser extent, for people with tertiary education and households with more than one income (SURS, 2021[3]) (EAPN, 2021[4]). The pandemic also affected women’s employment, given their high presence in the sectors most impacted by the crisis, such as health care (due to the over-exploitation of a limited workforce capacity), elderly home-care (due to high shares of women’s unpaid work at home) and food and tourism (due to job losses) (Figure 1.3, Panel C) (EAPN, 2020[5]). Another area of concern is education, where results of the national knowledge assessments (NPZ) for 9-grade students for 2020-21 were lower than the average results in 2015-2019 in mathematics, although the number of tested students was too low to derive conclusions on average student performance (RIC, 2021[6]). The pandemic has also entailed a surge in domestic violence, especially against women and children. Police records show that such cases increased by almost 24% by mid-2021 – four times higher than the increases observed in the previous two years in the same period (Figure 1.3, Panel B) (EAPN, 2021[4]) (UNODC, 2021[7]).

Looking ahead, public authorities should not underestimate the long-term consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic on the population’s health and well-being. The National Institute of Public Health expects increasing pressure on the health sector due to mental health problems and a possible rise in chronic non-communicable diseases related to the pandemic (see below). Moreover, social disparities may increase as the social effects of the pandemic have affected groups with weaker socio-economic backgrounds (NIJZ, 2021[8]).

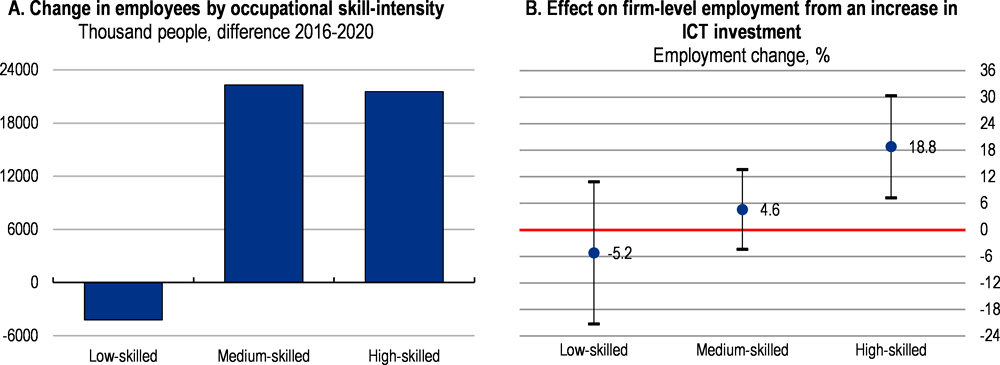

Sustaining recent gains in employment and incomes in the face of an older and smaller workforce requires markedly improved productivity growth. Looking ahead, a key structural challenge is to improve the employment prospects of low-income and older workers through better incentives for life-long learning and improved mobility. Such efforts should be complemented by measures to shift to cleaner energy and new technologies, and accelerate the digital transformation of the economy. These policies should be implemented alongside measures to prepare public finances for the fiscal challenges associated with population ageing.

Figure 1.3. The social costs of the pandemic are still unfolding

Note: In Panel B, data refer to the first 7 months of the year.

Source: NIJZ, Results of the COVID-19 Survey (SI-PANDA); EAPN (2021), Report on monitoring poverty and social exclusion in Slovenia; and OECD Gender database.

Against this background, the Survey has three main messages:

Fiscal consolidation is needed to reduce demand pressures. This does not rule out additional support for most affected households by the energy crisis. But additional support will have to be financed by cuts to other government recurrent spending. Such efforts should be implemented alongside structural reforms to prepare public finances for the fiscal challenges associated with population ageing. This will require first and foremost measures to promote later retirement and longer working lives.

Promoting productivity growth entails measures to raise investment in new technologies, particularly to foster the digital transformation of the economy. Such efforts need to be complemented by measures to improve the employment prospects of low-income and older workers.

Greener growth necessitates further efforts to reduce emissions in a cost-efficient manner by realigning incentives embodied in environmental policies. This calls for the introduction of carbon taxes in non-ETS sectors, notably the residential, commercial and industrial sectors, and the phasing out of exemptions from excise duties.

The pandemic strained the health system

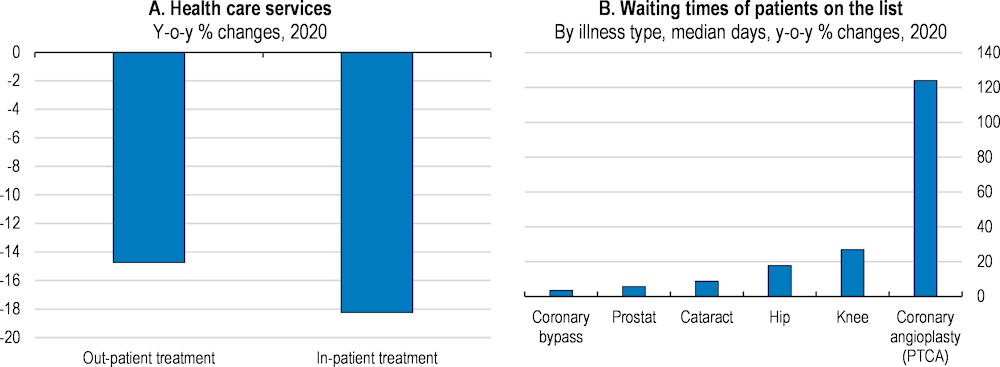

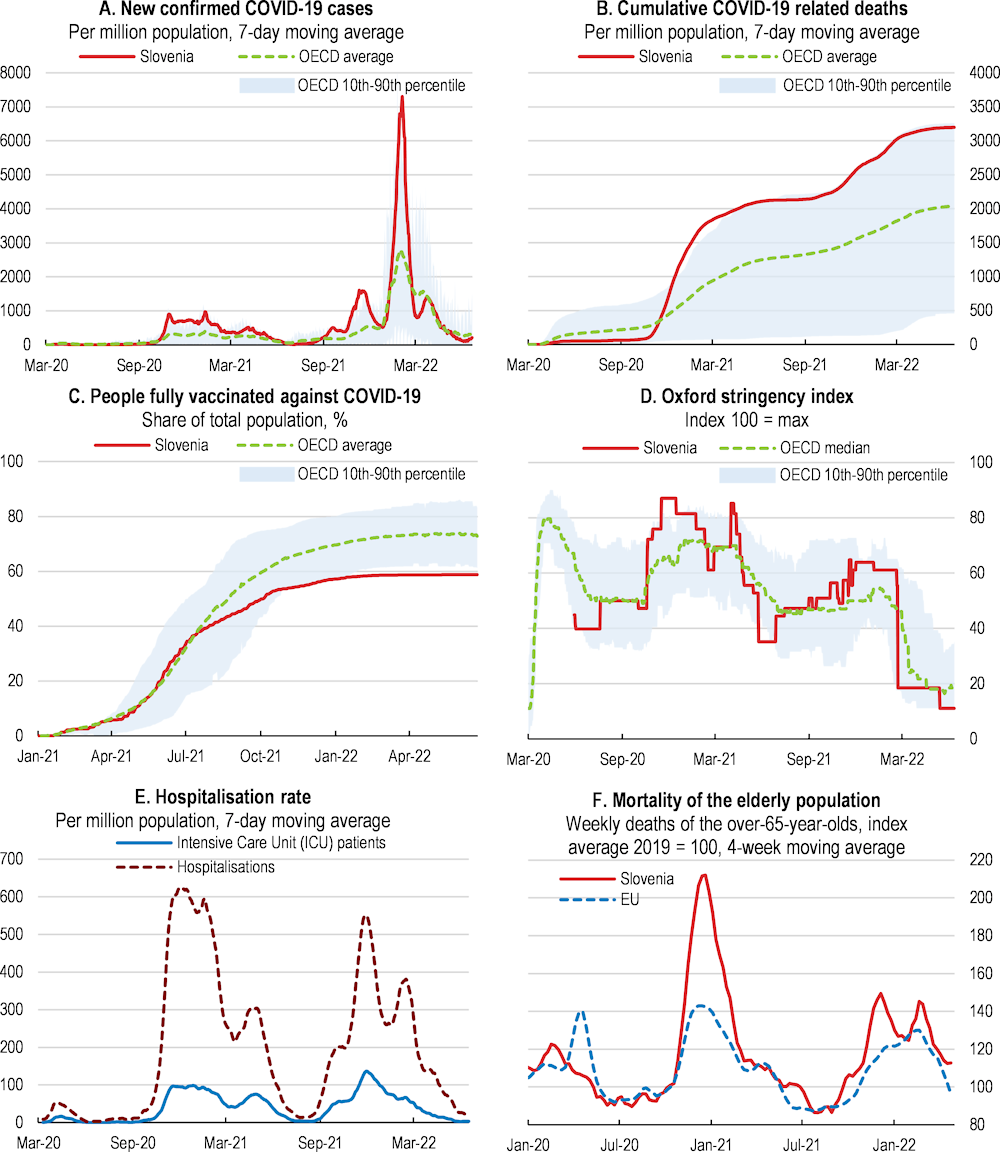

The vaccination rollout in early 2021 initially progressed fast but slowed down by summer 2021 (see below). This contributed to severe fourth and fifth waves in late 2021 and early 2022 (Figure 1.4). The reallocation of health resources to the treatment of COVID patients reduced outpatient and inpatient treatments (Figure 1.5, Panel A). For instance, 51% and 70% fewer patients were referred to inpatient care during the first wave of the pandemic in March and April 2020, respectively (Kuhar, Gabrovec and Albreht, 2021[9]). A consequence was a substantial increase in waiting times for elective surgeries, such as heart problems (Panel B). This suggests a reduced capacity to detect symptoms for many illnesses, such as cardiovascular problems. A concern is that foregone early treatments may potentially lead to more costly treatments in the future and higher mortality, putting additional strains on the health sector. Looking ahead, capacity constraints in hospitals should be addressed by enhancing outpatient care as was discussed in the last Survey (OECD, 2020[10]).

Figure 1.4. The healthcare situation worsened in late stages of the pandemic

Note: In Panel D, the index is a composite measure based on nine response indicators including school closures, workplace closures, and travel bans, rescaled to a value from 0 to 100 (100 = strictest). Unweighted averages for OECD aggregate in Panels A, B and C. In Panel F, the EU aggregate includes all 27 member economies with the exception of Ireland.

Source: Oxford Coronavirus government response tracker; OurWorldinData; Eurostat Demography and Migration database; and OECD calculations.

Figure 1.5. Capacity reallocation may increase mortality from other causes in the future

The pandemic limited physical activity, which potentially compounded the health effects of a general increase in unhealthy lifestyle choices and reduced prevention. The increase in consumption of tobacco, alcohol and unhealthy food was notably high for young people. Looking ahead, such changes are major risk factors for non-communicable diseases (NCDs), such as cardiovascular disease, cancer, diabetes and chronic lung disease (responsible for nearly three-quarter all deaths) (WHO, 2020[11]). Such potential negative long-term health effects are compounded by the decline in health promotion and prevention during the pandemic. For example, in early 2021, nearly 40% of the surveyed population refrained from visiting the doctor due to problems unrelated to COVID-19 (Figure 1.3, Panel A) (NIJZ, 2021[2]) (OECD, 2017[12]). A recent European study on cancer treatment disruptions during the pandemic shows that large numbers of patients were affected by treatment delays (European Cancer Organisation, 2021[13]). While specific data on untreated cancers are not yet available for Slovenia, evidence shows that patients’ waiting times for selected elective surgeries (unrelated to cancer) picked up by almost four months in 2020, reaching some of the highest levels in the OECD (OECD, 2021[14]).

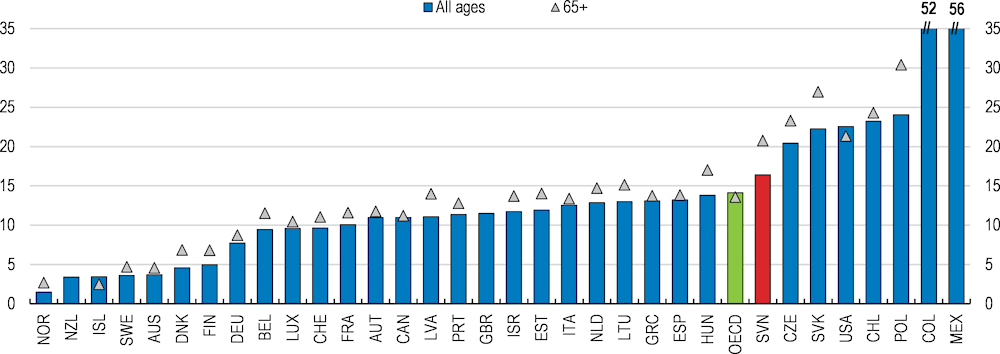

The pandemic had relatively severe health implications as Slovenia registered comparatively high excess mortality, leading to at least one year of lower life expectancy (Figure 1.6) (OECD, 2021[15]). Looking ahead, there are signs that the pandemic is becoming endemic (World Health Organization, 2022[16]), with seasonal COVID-19 outbursts, similar to the flu. According to the World Health Organisation, the best way to treat an endemic disease is to raise vaccination uptake among the population (World Health Organization, 2022[17]). However, vaccine hesitancy is high: only 60% of the population was fully vaccinated by March 2022. Moreover, vaccine scepticism goes beyond COVID-19 as illustrated by low flu vaccination rates and low confidence in vaccination already before the pandemic (OECD, 2022[18]). Better preparedness for future mass vaccinations calls for greater flexibility of the healthcare system. A way forward is to incentivise general practitioners to raise vaccination rates. In the United Kingdom, for instance, the National Health Service provides higher temporary reimbursement rates for COVID vaccinations to general practitioners during peak seasons. Efforts to increase the vaccination rate should be continued.

Figure 1.6. Excess mortality has been high

Excess mortality 2020-2021, %

Note: Excess mortality is calculated by dividing the actual number of deaths by the average number of deaths over 2015-19.

Source: OECD Health Statistics database.

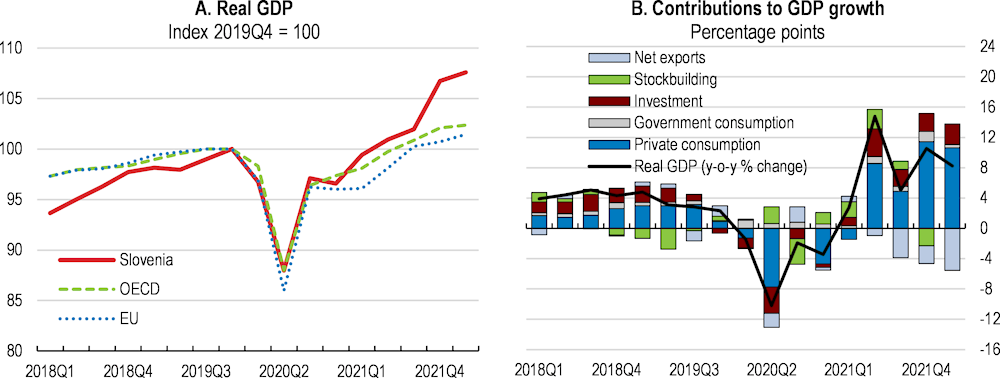

Economic prospects remain good despite elevated risks

The war in Ukraine is having negative impacts on economic activity. The conflict adds to the already high inflation through higher energy and food prices, putting pressure on the outlook for private consumption and investment. Until the outbreak of the war, the economy had experienced a strong recovery. Economic activity surpassed its pre-pandemic level by mid-2021 (Figure 1.7). The economic recovery benefitted from strong private consumption, reflecting fiscal support to households such as pandemic-related wage bonuses in the public sector and the government’s short-time work and furlough schemes. Public consumption also contributed to growth as the government raised pension benefits. Together with stronger international demand, the rebound in domestic demand benefited manufacturing and many service sectors, leaving tourism as the most negatively affected sector. The demand recovery, together with increasing capacity constraints, bolstered investment. Imports grew stronger on the back of buoyant domestic demand, leading to a negative contribution of net exports to growth and a declining current account surplus.

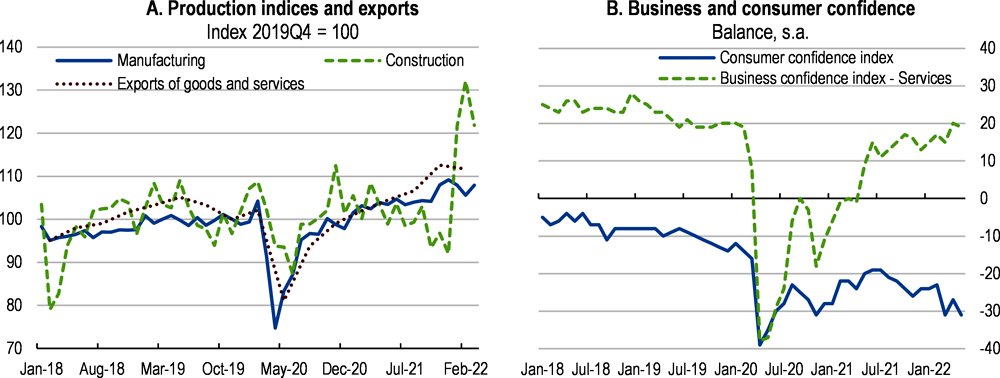

The pandemic caused a number of supply-chain bottlenecks. Nonetheless, industrial production bounced back and by early 2021, output was already higher than before the onset of the pandemic (Figure 1.8, Panel A). Since then, industrial output continued to rise on the back of buoyant demand. Business confidence rose to an all-time high in summer 2021, but has been volatile since then, reflecting prolonged supply-chain disruptions. Consumer confidence continued to recover until summer 2021, when higher inflation started to dampen confidence (Panel B). The war in Ukraine is a key source of uncertainty. Direct trade with Russia and Ukraine is low, although nearly 100% of gas and 17% of oil and petroleum imports come from Russia (Figure 1.9, Panel A). Higher energy prices and disruptions to supply-chains are already weighing on consumer and business confidence. There might be more indirect effects, such as a further rise in energy costs and continued disruptions to international supply chains in the important automotive sector (Panel B). To ensure gas supplies in the event of a stop of Russian gas flows, the government is in contact with other foreign suppliers and is taking steps to secure LNG capacity in neighbouring countries. The war in Ukraine has also led to an inflow of about 18 000 Ukrainian refugees to Slovenia by May 2022. This is significantly less than in other Central European countries such as Poland, Hungary or the Slovak Republic (United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, 2022[19]). Nevertheless, the government expressed its willingness to host more refugees and granted Ukrainian refugees immediate residence and working permits (Government of Slovenia, 2022[20]; Euractiv, 2022[21]).

Figure 1.7. Economic activity surpassed its pre-pandemic level

Figure 1.8. Production and business confidence bounced back before the war in Ukraine

Note: In Panel A, manufacturing and construction refer to seasonally adjusted production indices, while exports of goods and services are expressed in real terms.

Source: OECD Economic Outlook: Statistics and Projections database; and OECD Main Economic Indicators database.

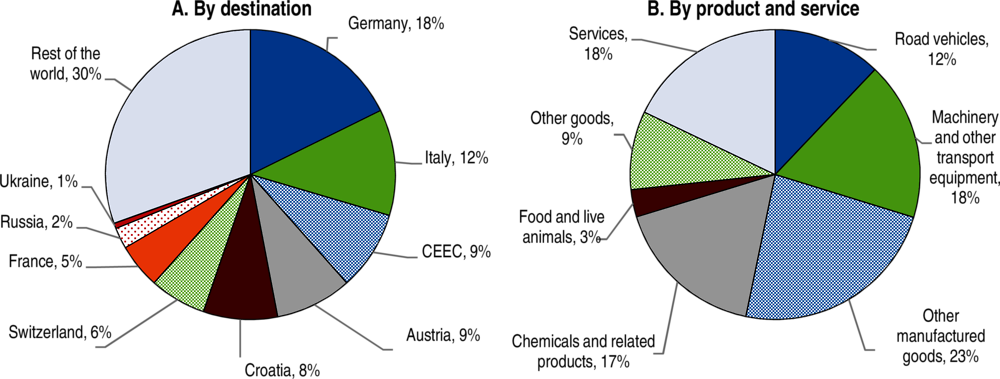

Figure 1.9. Exports are well diversified

Exports of goods and services, % of total, 2019

Note: In Panel A, the CEEC (Central and Eastern Europe Countries) aggregate includes Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland and Slovak Republic. In Panel B, the category "Machinery and other transport equipment" includes "Other transport equipment" (i.e. "Railway vehicles & associated equipment", "Aircraft & associated equipment; spacecraft, etc." and "Ships, boats & floating structures") and "Machinery" (i.e. "Power generating machinery and equipment", "Specialised machinery", "Metal working machinery", "Other industrial machinery and parts", "Office machines and automatic data processing machines", "Telecommunication and sound recording apparatus", and "Electrical machinery, apparatus and appliances, n.e.s."), in line with the Standard International Trade Classification (SITC) Revision 3, https://unctadstat.unctad.org/en/Classifications/DimSitcRev3Products_Official_Hierarchy.pdf. In Panel A and B, exports to Switzerland are less important once re-export of chemicals and related products are taken into account (only around 1.3% in 2019) (Bank of Slovenia, 2022[22]).

Source: OECD International Trade by Commodity Statistics (ITCS) database; OECD International Balanced Trade Statistics database; and OECD calculations.

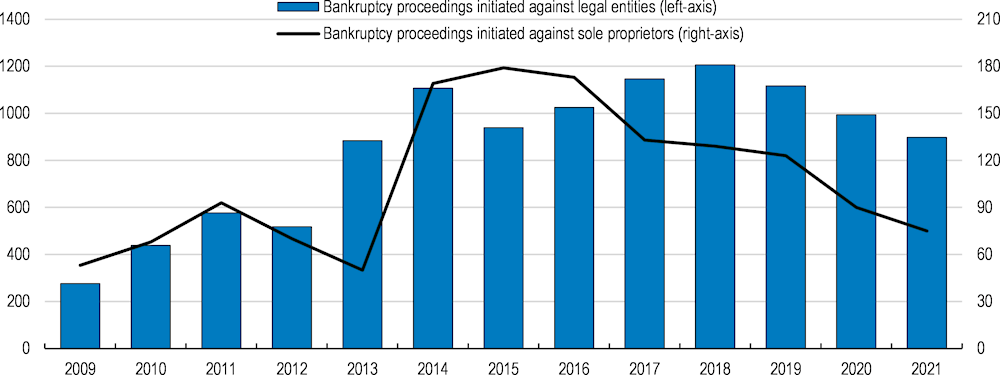

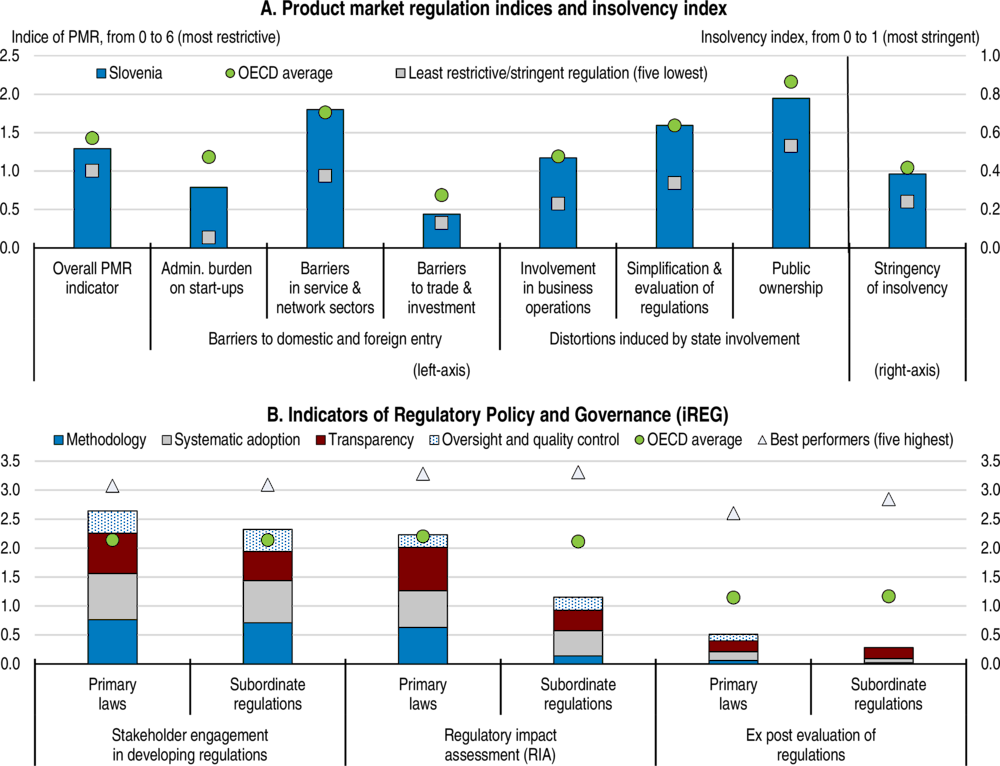

Bankruptcies remain below their pre-pandemic levels, reflecting generous COVID-19 related business support, a loan payment moratorium and the temporary halt of insolvency proceedings in 2020 and 2021 (Figure 1.10). Looking ahead, bankruptcies are expected to rise as government support has been withdrawn and the loan repayment moratorium has expired. This will affect in particular the hospitality sector, where non-performing loans have been rising since mid-2021. In addition, bankruptcies may rise in response to higher raw material and energy prices, leading to increasing producer prices. Given the current tight labour market, such a development can free up labour resources for the benefit of firms facing labour shortages. For this to happen, more efficient bankruptcy rules are needed to facilitate the transfer of under-utilised resources back into the productive part of the economy as well as a decentralised wage-setting process that improves the allocative efficiency of the labour market (see below).

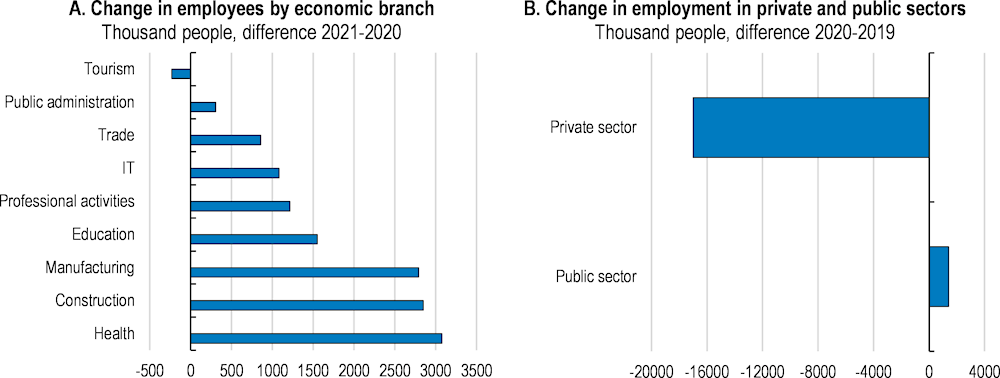

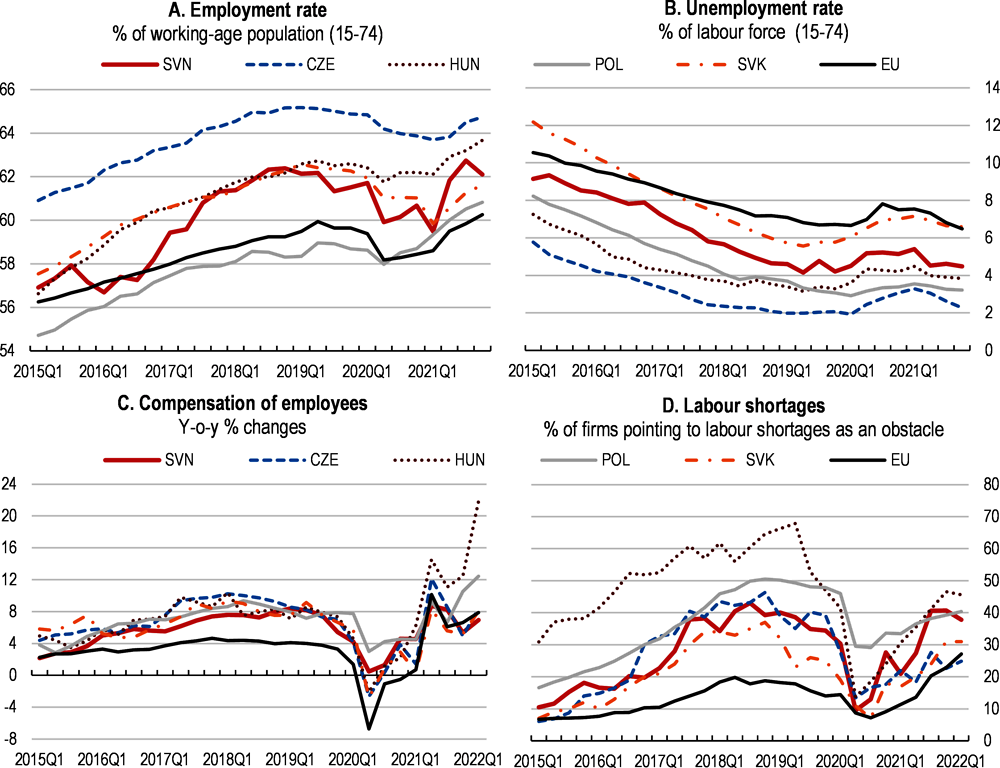

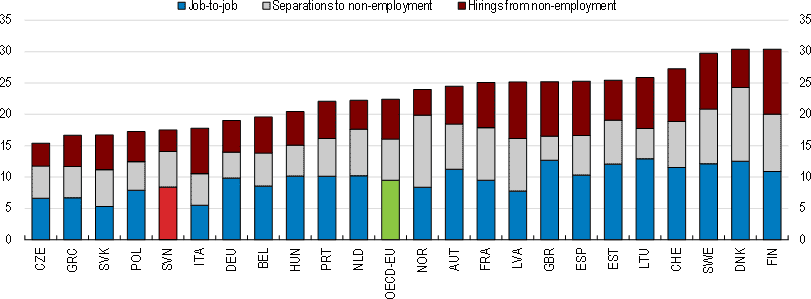

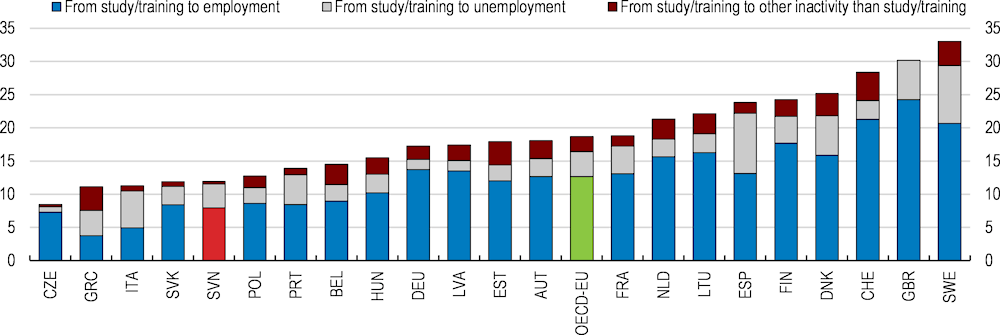

Government measures, including the short-time work and the furlough schemes, kept workers in employment during the first waves in 2020 and 2021. This kept the increase in the unemployment rate to only 1 percentage point between early 2020 and early 2021, or nearly 2 percentage points lower than during the similarly sized financial crisis. Another contributing factor was that the public health sector expanded employment (Figure 1.11). Thereafter, strong foreign demand and reduced restrictions allowed the labour market to return to its favourable pre-pandemic situation. Employment growth was broad-based with the exception of tourism. The labour market is very tight. By the end of 2021, employment reached a historic height, while the unemployment rate returned to its pre-pandemic level. The tight labour market is also reflected in rising labour shortages (Figure 1.12) (see below).

Figure 1.10. Government support averted bankruptcies

Number

Figure 1.11. Employment growth is broad-based

Figure 1.12. The labour market is tight

Note: Data are seasonally adjusted.

Source: OECD Main Economic Indicators database; OECD Labour Statistics database; OECD National Accounts database; and OECD calculations.

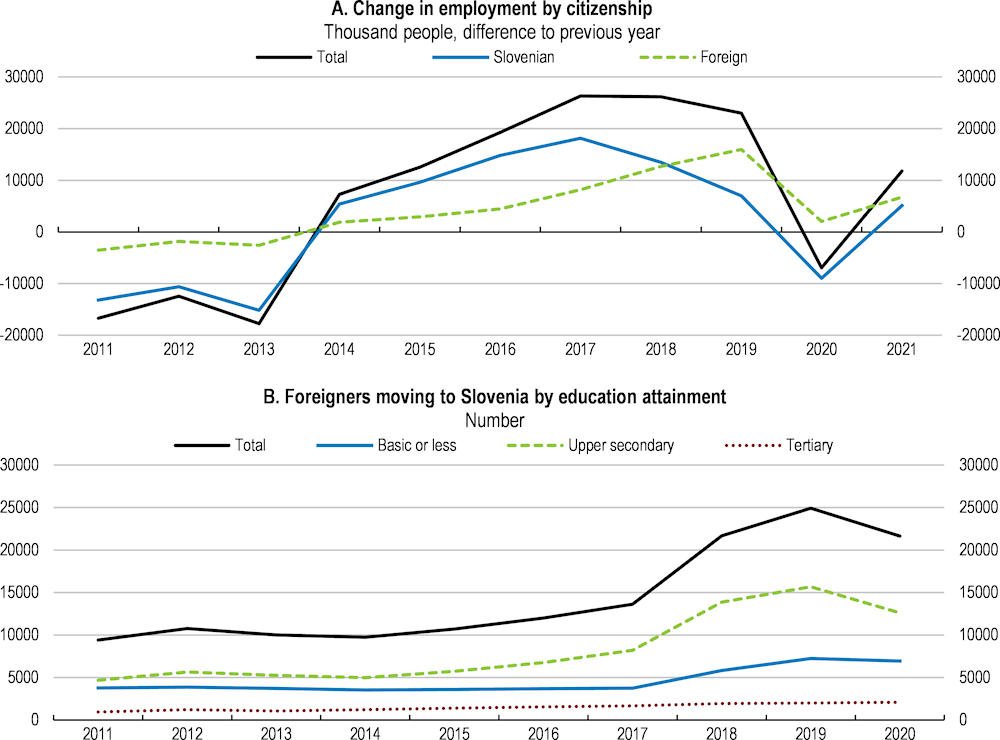

The inflow of mainly low- and medium-skilled immigrants was reduced in 2020 as the pandemic led the government to close the border (Figure 1.13). Thereafter, the inflow of foreign workers rose sharply again to levels seen before the pandemic as COVID-related restrictions were eased and labour demand grew strongly. Given the shortage of domestic labour, immigrants and cross-border commuters accounted for more than 50 per cent of new hires in 2021 (Statistical Office of Slovenia, 2022[23]). However, the inflow of low- and medium-skilled workers from neighbouring ex-Yugoslavian economies is not sufficient to meet strong labour demand, especially in the construction and tourism sectors. Looking ahead, Slovenia will face stronger competition for foreign workers as labour shortages continue to materialise in richer OECD countries.

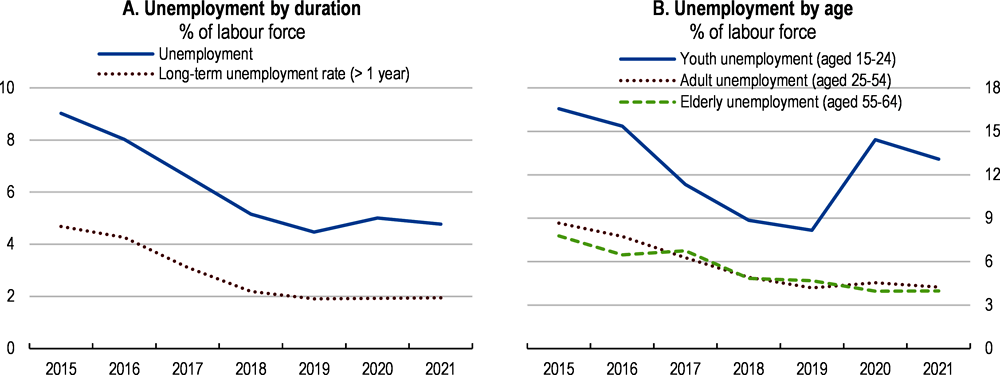

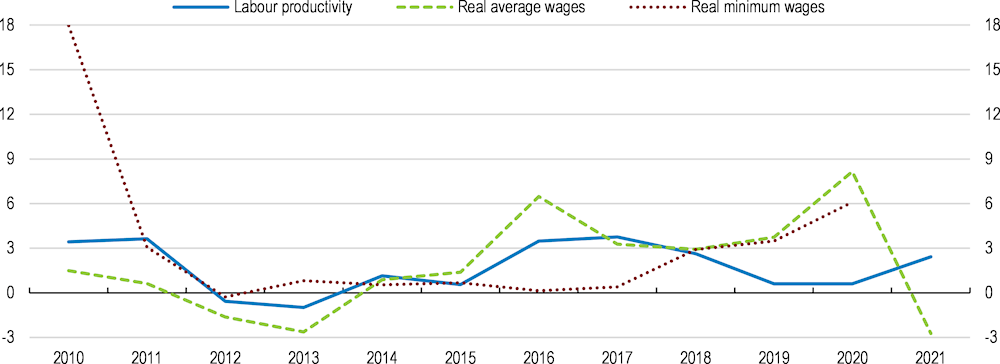

Figure 1.13. The number of foreign workers is rising again

The crisis interrupted strong nominal wage growth 2020, which resumed again in 2021, reflecting the pandemic-related short-time work and furlough schemes as well as wage supplements in the public sector (Bank of Slovenia, 2022[24]). Wage growth slowed in early 2022 as these one-off measures were withdrawn before picking up again in spring 2022 on the back of higher wage growth in the private sector. The tightening labour market is expected to contribute to higher wage inflation in 2022 and 2023. Another driver of wage pressures is the minimum wage increase of 5% in early 2022, which affected 15% of all workers (Tax Administration of the Republic of Slovenia, 2021[25]). Earlier increases in the minimum wage relative to other wages reduced the job prospects of mainly low-skilled young unemployed (Laporšek, Vodopivec and Vodopivec, 2019[26]; Laporšek et al., 2019[27]) (OECD, 2020[10]). The strong minimum wage hike may have contributed to keeping their unemployment high during the post-pandemic labour market upswing as well (Figure 1.14). Yet real wage growth turned negative by end-2021 as consumer price inflation reached a 20-year high (Figure 1.15) (see below). Until then, real wage growth had outpaced labour productivity growth since 2019, reducing the sustainability of continued rapid wage increases (Figure 1.15). Other emerging Central and Eastern European economies had similar price dynamics, helping to preserve external competitiveness. On the other hand, dynamic wage and price developments could fuel a wage-price spiral. Such a development would erode external competitiveness.

Figure 1.14. Youth unemployment has been slow to come down

Figure 1.15. Wage growth outpaced productivity improvements

Wages and productivity, y-o-y % changes

Note: Labour productivity refers to real GDP (2019 prices) per total hours worked. Real average wages refers to the national-accounts-based total wage bill divided by the number of hours worked in the total economy, deflated by a price deflator for private final consumption expenditures in 2019 prices. Real minimum wages refers to the hourly minimum wage deflated by the consumer price index taking 2019 as the base year.

Source: OECD National Accounts database; OECD Labour Statistics database; and OECD calculations.

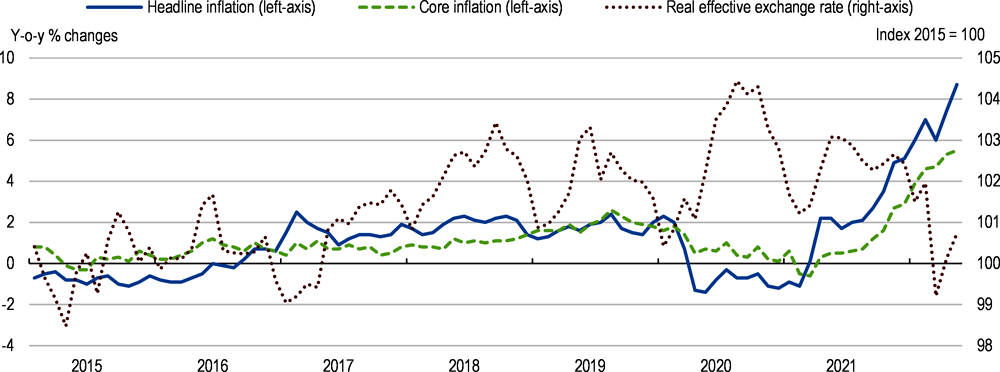

Inflation has remained consistently above the ECB’s 2% target since summer 2021 and reached with 8.7% a 20-year high in spring 2022 (Figure 1.16). Initially, the increase in inflation reflected mostly higher energy prices in early 2021. Inflation has continued to increase as domestic price pressures have been rising sharply since mid-2021. Goods price inflation began to accelerate as consumer demand shifted from services to consumer goods and was fuelled further by global supply chain problems. This was followed by a sharp acceleration of service price inflation since end-2021. The tight labour market is expected to contribute to wage pressures and thus service price inflation throughout 2022 and 2023. The depreciation in the effective exchange rate in early 2022 further added to higher inflation by raising import prices. Since February 2022, the war in Ukraine has accelerated inflationary pressures stemming from higher energy prices. Energy price increases were dampened by the introduction of a temporary cap on fuel prices between mid-March and end-April 2022, before energy prices continued to rise. The price cap is set to increase contingent liabilities from state-owned energy companies by up to 0.2% of GDP. A better targeted measure is direct income support for low-income households, as introduced in April 2022 (OECD, 2022[28]).

Figure 1.16. Inflation pressures remain high

Note: Core inflation excludes food, energy, tobacco, alcohol.

Source: OECD Main Economic Indicators database.

GDP growth is projected to moderate in 2022 and 2023, mostly reflecting the negative impact from the war in Ukraine (Table 1.1). The conflict will add to the already high inflation through higher energy and food prices, putting pressure on private consumption and investment. Nonetheless, economic activity will continue to expand and is projected to close the output gap in 2022. Economic growth will mostly be driven by private demand. Private consumption will benefit from real income increases on the back of a tight labour market. Investment will continue to expand on the back of inflows of EU funds. The labour market is expected to remain tight, with historically high employment and low unemployment rates continuing to put pressure on wages. Together with high and rising fuel and food prices, this will lead to higher headline inflation. The projections are based on the assumption that the Ukraine war will last a year. Additional support to households should be financed by spending cuts elsewhere as the current expansionary fiscal stance risks prolonging demand pressures. On the other hand, a short-lived conflict would remove the need for additional fiscal stimulus.

Table 1.1. Macroeconomic indicators and projections

|

|

2019 |

2020 |

2021 |

2022¹ |

2023¹ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

Current prices (EUR billion) |

Annual percentage change, volume (2015 prices) |

|||

|

Gross domestic product (GDP) |

48.4 |

-4.2 |

8.1 |

4.6 |

2.5 |

|

Private consumption |

25.4 |

-6.6 |

11.6 |

10.5 |

2.1 |

|

Government consumption |

8.9 |

4.2 |

3.9 |

2.2 |

1.1 |

|

Gross fixed capital formation |

9.5 |

-8.2 |

12.3 |

11.8 |

4.3 |

|

Housing |

1.1 |

-0.2 |

0.5 |

10.3 |

6.2 |

|

Final domestic demand |

43.7 |

-4.7 |

10.0 |

9.0 |

2.4 |

|

Stockbuilding² |

0.5 |

0.1 |

0.8 |

0.0 |

-0.0 |

|

Total domestic demand |

44.2 |

-4.6 |

10.8 |

7.0 |

2.4 |

|

Exports of goods and services |

40.6 |

-8.7 |

13.2 |

5.4 |

3.4 |

|

Imports of goods and services |

36.4 |

-9.6 |

17.4 |

10.5 |

3.3 |

|

Net exports² |

4.2 |

-0.1 |

-1.6 |

-3.7 |

0.2 |

|

Memorandum items |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Potential GDP |

. . |

2.5 |

2.5 |

2.5 |

2.3 |

|

Output gap (% of potential GDP) |

. . |

-7.1 |

-2.1 |

-0.0 |

0.1 |

|

Employment |

. . |

-0.5 |

-0.7 |

2.3 |

0.5 |

|

Unemployment rate (% of labour force) |

. . |

5.0 |

4.8 |

3.9 |

3.7 |

|

GDP deflator |

. . |

1.2 |

2.6 |

5.4 |

6.0 |

|

Harmonised index of consumer prices |

. . |

-0.3 |

2.0 |

7.6 |

6.0 |

|

Harmonised index of core inflation³ |

. . |

0.8 |

0.9 |

6.4 |

5.2 |

|

Household saving ratio, net (% of household disposable income) |

. . |

16.3 |

11.0 |

5.2 |

7.2 |

|

Current account balance (% of GDP) |

. . |

7.4 |

3.3 |

-1.5 |

-1.1 |

|

General government fiscal balance (% of GDP) |

. . |

-7.8 |

-5.2 |

-3.7 |

-3.6 |

|

Underlying general government fiscal balance (% of potential GDP) |

. . |

-4.3 |

-4.8 |

-4.5 |

-4.3 |

|

Underlying government primary fiscal balance (% of potential GDP) |

. . |

-3.0 |

-3.7 |

-3.3 |

-2.8 |

|

General government debt, Maastricht definition (% of GDP) |

. . |

79.8 |

74.7 |

73.5 |

73.3 |

|

General government net debt (% of GDP) |

. . |

40.2 |

34.5 |

35.0 |

35.8 |

|

Three-month money market rate, average |

. . |

-0.4 |

-0.5 |

-0.2 |

0.9 |

|

Ten-year government bond yield, average |

. . |

0.1 |

0.1 |

1.5 |

2.1 |

1. OECD estimates.

2. Contribution to changes in real GDP.

3. Index of consumer prices excluding food, energy, alcohol and tobacco.

Source: OECD Economic Outlook 111 database.

A major downside risk is that a combination of stronger wage growth and the energy price shock could further de-anchor inflation expectations and lead to a wage-price spiral. Another important risk is an embargo on Russian gas supply. On the upside, faster digitalisation, higher-than-expected productivity increases, and better labour utilisation could raise growth prospects. A more intensive use of labour resources and increased immigration could help to reduce wage pressures.

Table 1.2. Events that could lead to major changes in the outlook

|

Global energy and food crisis |

An intensification of global trade tensions with large energy and food supply disruptions would lead to a further acceleration of inflation and a contraction of global trade, leading to stagflation. |

|

Major international financial crisis |

Markedly higher long-term yields could trigger domestic banking sector stress. |

|

Outbreak of a new vaccine-resistant COVID variant |

Further waves of infections could potentially lead to new lockdown measures and lower domestic spending. |

Monetary conditions remain accommodative

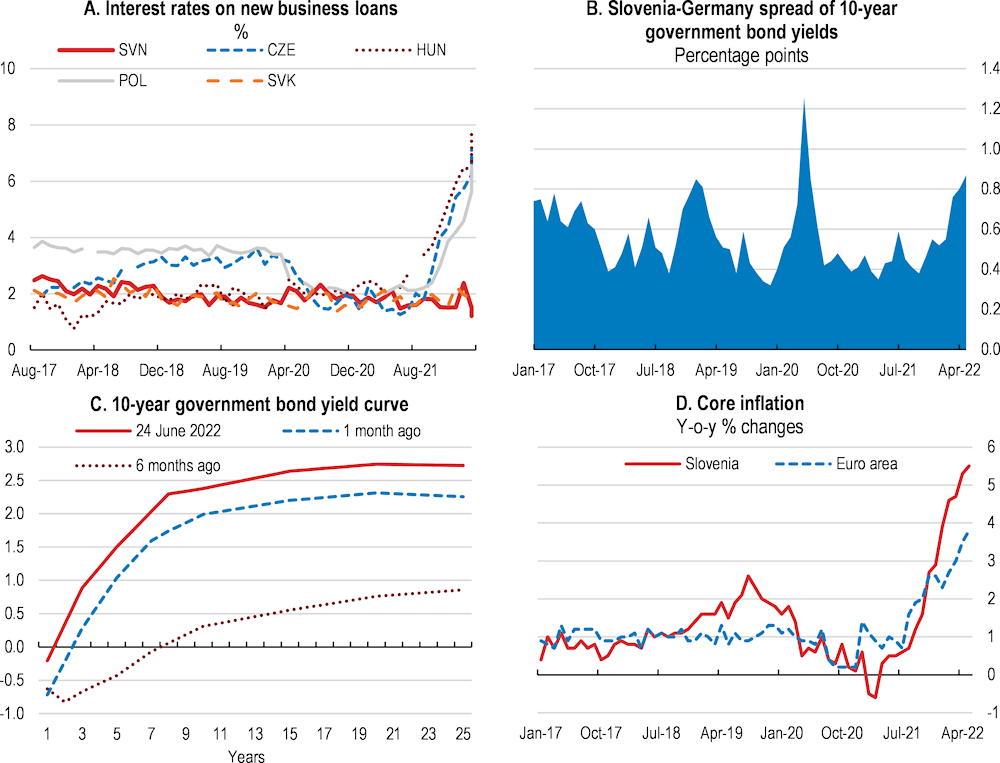

Monetary conditions have been accommodative with low interest rates on business loans and low spreads over German 10-year government bonds until early 2022, when long-term interest rates started to increase (Figure 1.17). The ECB’s accommodative monetary policy stance was appropriate for Slovenia, as inflationary pressures were low and the economy still recovering. However, strong growth since mid-2021 and a labour market showing signs of overheating suggest that the monetary policy stance fell short of anchoring Slovenian inflation expectations. Indeed, inflation has remained consistently above the ECB’s target since summer 2021. The initial increase in inflation reflected external factors, such as higher energy prices, which were believed to be transitory. However, inflation has continued to increase as domestic inflation pressures, particularly service prices, have continued to rise. Another contributing factor to rising inflation was the depreciation in the real effective exchange rate since the end of 2021, followed by the strong rise in commodity prices resulting from the Ukraine war in early 2022. This supports the notion that inflation expectations have increased and that a price-wage spiral could be emerging, which eventually would lead to a steeper yield curve.

Figure 1.17. Monetary conditions remain accommodative despite inflationary pressures

Note: In Panel A, data refer to loans other than revolving loans and overdrafts, convenience and extended credit card debt.

Source: European Central Bank (ECB) database; Refinitiv Datastream; World Government Bonds.

Looking forward, the European Central Bank is set to raise its policy rate in response to high European inflation. However, Slovenian core inflation is already above the Euro level. Should monetary conditions remain too loose, tighter fiscal would help to contain inflation expectations and avoid higher long-term interest rates with negative consequences for public finances, while also laying the ground for securing fiscal sustainability.

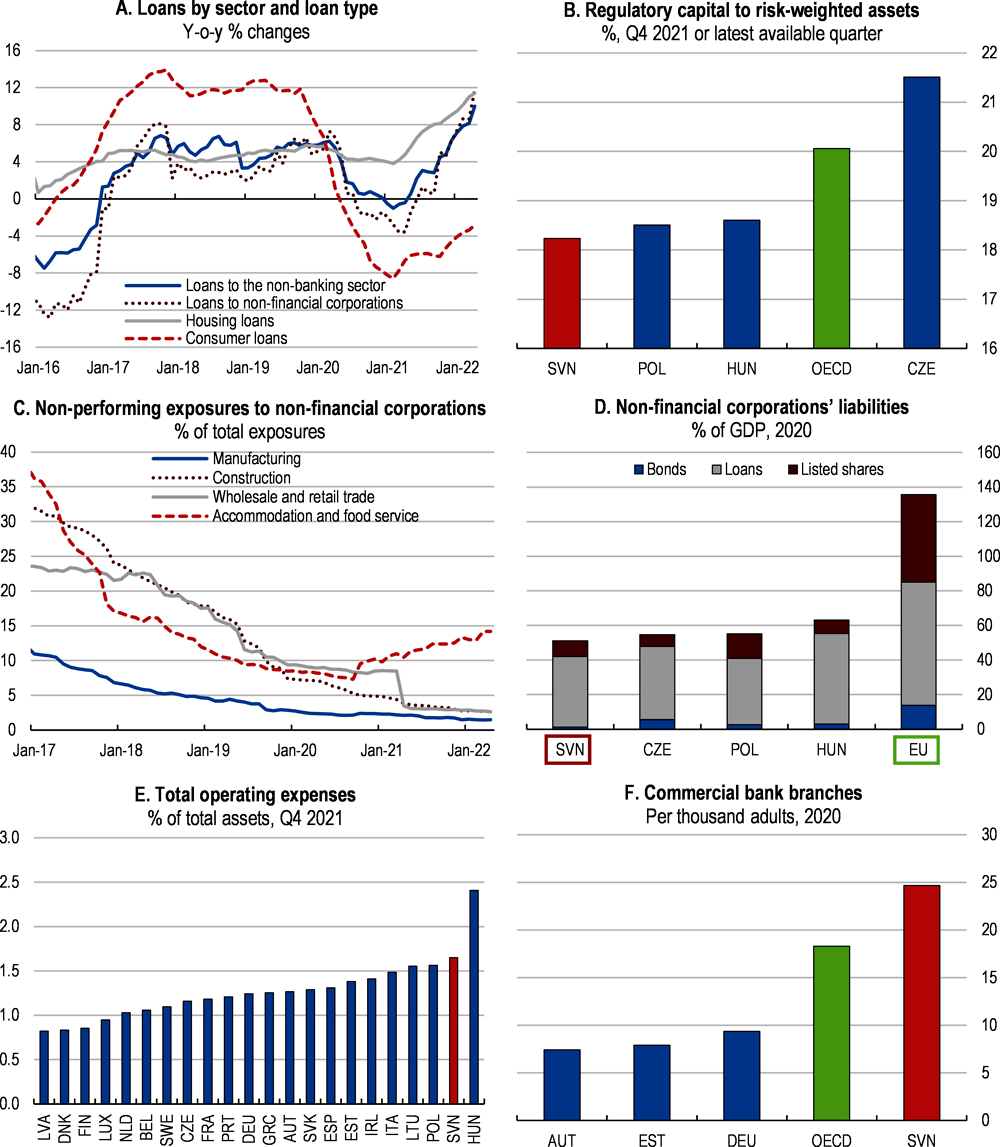

A deeper capital market can support digitalisation

Financial risks in the banking sector are low. Banks remain well capitalised with an average capital adequacy ratio of 18.5%, above national and international regulatory requirements. The sector has been able to continue to provide credit to the private sector in spite of the COVID crisis (Figure 1.18, Panel A and B). Nevertheless, the pandemic has had an impact as the downward trend in the share of non-performing loans slowed since mid-2021, reflecting lower creditworthiness in the heavily affected hospitality sector (Panel C). At the same time, the quality of banks’ loan portfolio declined, as the share of loans with higher default risk began to rise in the professional services and entertainment sectors. There is also a higher default risk of loans that were under the loan repayment moratoria in 2020 and 2021. Another risk to the quality of banks’ loan portfolio stems from rising raw material and energy prices that might lead to a rise in bankruptcies. An additional concern for banks is that increasing interest rates could lead to higher defaults in the housing sector. So far, banks have not reacted by increasing provisions (Bank of Slovenia, 2022[29]). Looking ahead, banks should prepare for the likely increase in loan losses.

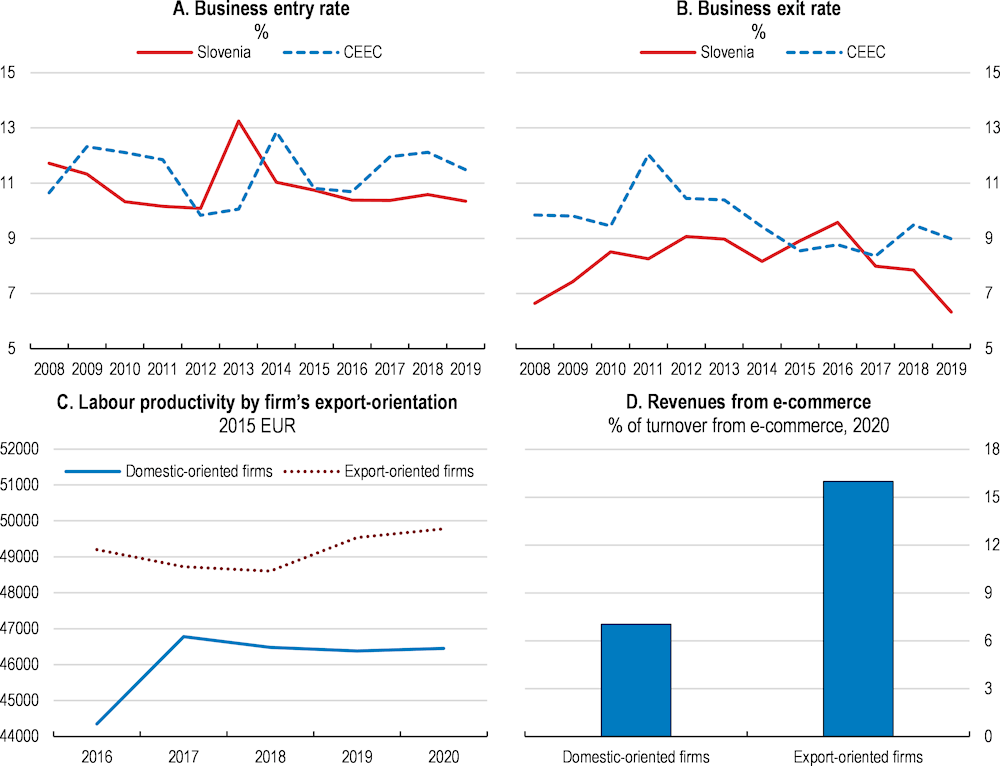

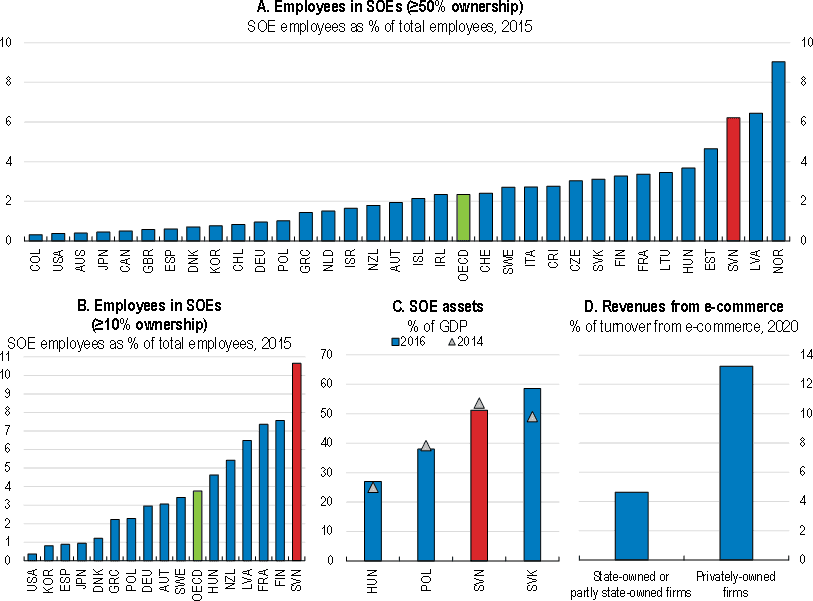

More structurally, the overreliance of businesses on bank credit remains a concern for securing financing for new and innovative firms, particularly in the service sector, which is key for faster digitalisation (Figure 1.18, Panel D). The traditional banking sector is not well suited to provide credit to new and riskier digital start-ups with innovative business models but little collateral (Chapter 2). Moreover, banks are also unlikely to step up lending for riskier activities given their declining profitability, which reflects high operating costs and low digitalisation (Bank of Slovenia, 2021[30]) (Panel E).

Public ownership may affect efficiency in the banking sector. For example, the number of commercial bank branches per population remains high (Figure 1.18, Panel F). Currently, the government continues to be the largest shareholder in the biggest bank. State involvement limits private investors’ ability to restructure the bank’s operations. Remaining public shareholdings in the largest bank should be re-examined.

Underdeveloped capital markets hold back digitalisation. Stock market capitalisation remains among the lowest in the EU and the OECD (World Bank, 2022[31]). A factor behind low capital market investment is the limited role of institutional investors, notably insurance companies. In contrast to most other OECD countries, the insurance sector is dominated by state-owned companies, although it is not obvious which market failures are addressed by state-ownership. Moreover, state-owned insurers are less active as institutional investors compared to their privately owned peers in Slovenia. Their investment portfolios consist mostly of low-risk government bonds, leaving investment in equity below levels of insurance sectors in most other OECD countries in 2021 (European Commission, 2019[32]; OECD, 2021[33]). To bolster capital market investment, privatisation efforts should go beyond banks into other areas of the financial sector, notably the insurance sector. This requires reviewing public ownership in the insurance sector to identify which areas can be privatised and following up by developing a privatisation programme for the insurance sector. Other sectors without obvious market failures that would justify state-ownership include tourism (see below).

Figure 1.18. Bank lending is strong but capital markets remain underdeveloped

Note: In Panel B, regulatory capital to risk-weighted assets ratio is calculated using total regulatory capital as the numerator and risk-weighted assets as the denominator. It measures the capital adequacy of deposit takers. Capital adequacy and availability ultimately determine the degree of robustness of financial institutions to withstand shocks to their balance sheets.

Source: Bank of Slovenia; IMF, Financial Soundness Indicators (FSIs) database; Eurostat Financial Balance Sheets database; European Central Bank (ECB) database; and World Bank database.

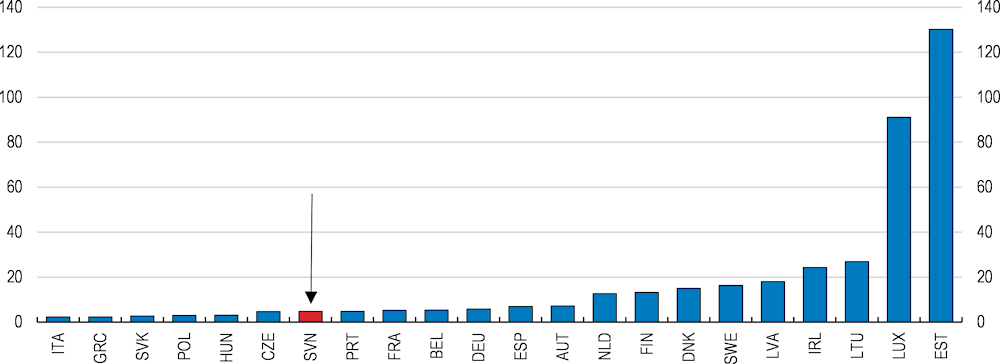

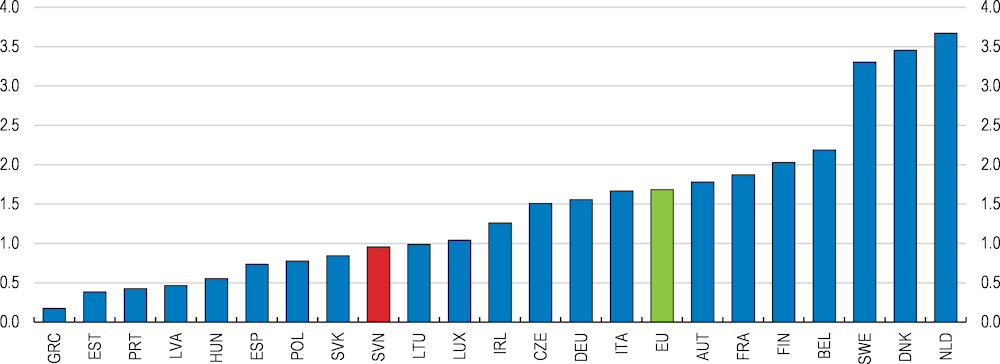

Financial innovation remains low

Financial innovation is lagging other countries and new market entry by FinTech start-ups is low (Figure 1.19). A concern is the limited progress in reducing entry barriers. For instance, efforts by the central bank to stimulate market entry in Fintech via regulatory waivers have had limited success (Bank of Slovenia, 2019[34]). The Bank of Slovenia established an Innovation Hub, which is dedicated to sharing knowledge and experiences among financial regulators and companies. Other countries have taken a much more proactive stance to favour entry of Fintech companies. In Lithuania, for instance, Fintech start-ups can apply for a Special Purpose Bank licence with lower capital requirements, which allows them to offer basic banking services. The Bank of Lithuania ensures a smooth licencing process not exceeding twelve months, and applications can be submitted in English (Invest Lithuania, 2022[35]). To bolster financial innovation, the regulatory burden, including the lowering of entry barriers, should be evaluated.

Figure 1.19. FinTech development is slow

Number of start-ups per million population, 2021

Note: Based on search “FinTech” in the field “description keywords”.

Source: Crunchbase (database), https://www.crunchbase.com, accessed on 17 March 2022; OECD Demographic Statistics database; and OECD calculations.

The government has taken only some action to accommodate latest FinTech developments (IFLR, 2020[36]). For instance, the government plan to make Slovenia a “Blockchain Hub”, which includes a 2018 action plan to implement blockchain technology and to create a regulatory framework for cryptocurrencies, has remained largely unimplemented. Cryptocurrencies remain unregulated and a specific regulatory framework for Initial Coin Offerings does not exist. A draft law was adopted by the government in spring 2022 that introduced the taxation of capital gains from cryptocurrency assets by five per cent starting at EUR 10 000 (once transferred in a Slovenian bank account), but the objective is to increase fiscal gains rather than to promote a regulatory framework conducive to innovation. To ease the regulatory burden on FinTech companies, a regulatory sandbox could be introduced at the central bank, as done in many other OECD countries (ESAS, 2022[37]). Such a regulatory sandbox allows the supervisor to waive certain financial regulations to ease market entry and strengthen innovation. Regulatory sandboxes can be effective in spurring innovation. In the United Kingdom, for instance, FinTech start-ups entering the regulatory sandbox saw a 15 percent increase in their capital raised after they entered the sandbox, relative to FinTech firms that did not enter the sandbox (Cornelli et al., 2020[38]).

At the international level, Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania harmonised their regulations regarding e-money and payment licenses in 2018 to facilitate market entry of new financial players. Since then, the number of new Fintech start-ups entering the market grew by 70% (Laidroo et al., 2022[39]; Swedbank, 2021[40]; Invest Lithuania, 2022[41]). Regional integration efforts should also go beyond FinTech markets, including more traditional financial instruments such as covered bonds. An example of successful regional integration is again the Baltic area, which led to the creation of a pan-Baltic capital market for covered bonds with a volume of 20% of regional GDP in 2018 (EBRD, 2020[42]; Scope Ratings, 2018[43]). A closer alignment of FinTech regulations with Central European countries would help bolster financial innovation. More generally, the Survey recommended a stronger regional integration of financial markets as another way to strengthen financial innovation (OECD, 2020[10]). So far, however, progress has been slow since 2016 when the Zagreb stock exchange acquired the Ljubljana stock exchange.

Green financing also remains underdeveloped (OECD, 2021[44]). A factor behind the low green investment is the lack of transparency about the criteria necessary to obtain green investment status. To strengthen green financing, regulation is needed to improve the financial disclosure of climate-change related risks. A first step forward is to align the rules for the financial disclosure of environmental costs with the European classification on green investment. Going beyond European legislation in this area could further promote green financing, for example by giving the central bank the regulatory power to verify climate-related risks in ’ the financial statements of financial institutions as in the United Kingdom.

Table 1.3. Past recommendations on easing competition in the financial sector

|

Recommendations in previous Surveys |

Action taken since the 2020 Survey |

|---|---|

|

Use the Bank Asset Management Company (BAMC) to ensure swift restructuring of companies and effective liquidation of assets. |

BAMC’s mandate has been extended until 2022. NKBM and Abanka merged in 2020. |

|

Transfer all assets in a company group to the Bank Asset Management Company. |

The transferal of non-performing assets to BAMC has been completed. |

|

The Bank Asset Management Company should remain independent, with the highest standards of corporate governance and transparency. |

The BAMC has been strengthened by prohibiting its non-executive directors from having any managerial role in the BAMC. |

|

Privatise state-owned banks without retaining blocking minority shareholdings. |

Share sale of the largest state-own bank (Nova Ljubljanska Banka) has left the government a stake of 25% + 1 share. Full privatisation of the second-largest (ABANKA) has been completed. |

|

Implement the new insolvency regulation system, and improve institutional capacity by training judges and insolvency administrators. |

The new insolvency regulation system has been implemented. |

|

Make out-of-court restructuring faster and more attractive. |

No action taken. |

Adopting a forward-looking fiscal policy

Fiscal policy is becoming pro-cyclical

Fiscal policy has been expansionary since the onset of the pandemic. In 2020, the government implemented a comprehensive fiscal stimulus package of around 5% of GDP to support economic activity and protect people and firms. Adding the effects of automatic stabilisers, the budget balance turned negative and deteriorated by 8 percentage points, leading to a budget deficit of 7.8% of GDP in 2020 (Table 1.4). The bulk of the fiscal expansion was COVID-related and consisted of wage support and direct subsidies to businesses, while discretionary spending on health was less sizeable. On the revenue side, tax deferrals and the exemption of employers’ social security contributions reduced government revenues on a cash basis by nearly 1% of GDP.

In 2021, the composition of the fiscal stimulus changed. COVID-related discretionary spending was scaled back while there was a structural expansion of public investment and consumption. The latter reflected higher pension benefits due to a higher pension indexation and replacement rates, which were not financed by revenue-raising measures or cuts to government spending (see below). As a result, the budget deficit fell only marginally in 2021, reflecting discretionary budgetary measures of 5% of GDP and the continued operation of automatic stabilisers.

The composition of fiscal support changed again in 2022. The fiscal expansion now reflects a large increase in public investment in infrastructure, health and the green transition, which has a limited impact on the structural deficit. However, expansionary fiscal policy is also linked to an expansion of public transfers, which raised the structural deficit. Public transfers are set to increase in spite of lower spending on unemployment benefits. This reflects an increase in pension benefits due to a higher pension indexation and higher replacement rates. Additional temporary public transfers include targeted subsidies to households and businesses to mitigate the effects of increasing energy prices. These measures are expected to maintain the budget deficit at -3.5% in 2022, implying a fiscal consolidation of about ½ % of GDP.

A concern in the current situation is that the labour market shows signs of overheating (see above). This suggests that there is a need for policy measures to contain demand pressures. A faster fiscal consolidation should be implemented to contain demand pressures and prepare public finances for expected ageing-related spending increases. This does not rule out additional support for households most vulnerable to high food and energy prices. But additional support should be financed by cuts to other government spending. Prioritisation can be helped by government spending reviews as done in the United Kingdom for example.

Table 1.4. Fiscal indicators

Per cent of GDP

|

|

2019 |

2020 |

2021 |

20221 |

20231 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Spending and revenue |

|||||

|

Total revenue |

43.8 |

43.5 |

43.9 |

45.2 |

44.5 |

|

Total expenditure |

43.3 |

51.3 |

49.1 |

48.9 |

48.0 |

|

Net interest payments |

1.5 |

1.4 |

1.1 |

1.2 |

1.5 |

|

Budget balance |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Fiscal balance |

0.4 |

-7.8 |

-5.2 |

-3.7 |

-3.6 |

|

Cyclically adjusted fiscal balance2 |

0.7 |

-4.3 |

-4.2 |

-3.7 |

-3.6 |

|

Underlying primary fiscal balance2 |

2.2 |

-3.0 |

-3.7 |

-3.3 |

-2.8 |

|

Public debt |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Gross debt (Maastricht definition) |

65.6 |

79.8 |

74.7 |

73.5 |

73.3 |

|

Gross debt (national accounts definition)3 |

86.6 |

109.7 |

94.6 |

93.0 |

92.8 |

|

Net debt |

26.4 |

40.2 |

34.5 |

35.0 |

35.8 |

1. OECD estimates unless otherwise stated.

2. As a percentage of potential GDP.

3. National Accounts definition includes state guarantees, among other items.

Source: OECD Economic Outlook 111 database.

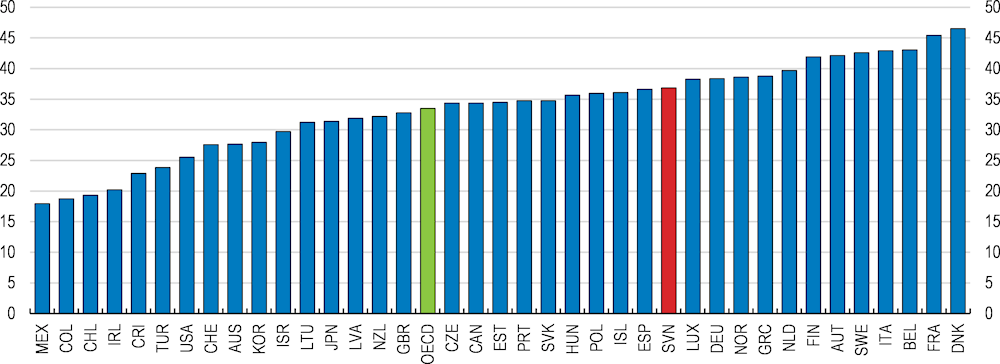

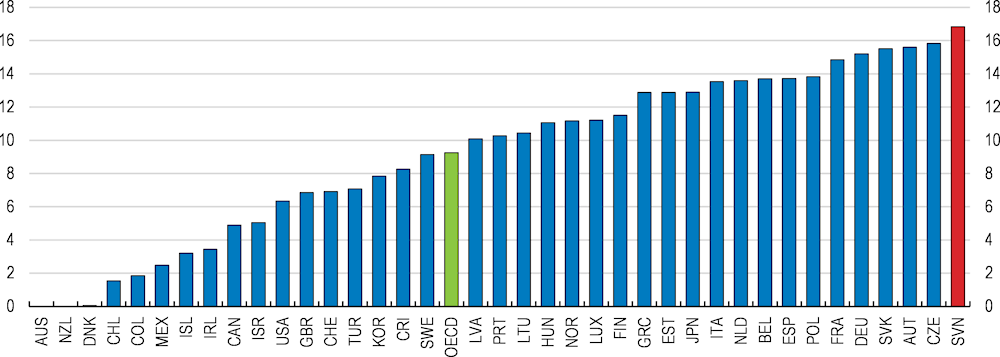

The structural deficit is high. This reflects the above-mentioned increase in pension benefits. In addition, the government passed a labour tax reform in spring 2022 to lower labour costs, which will see an increase in personal income tax allowances and lower personal income taxation for the highest income tax bracket (see below). Plans to raise the currently low property taxation to compensate the associated revenue loss were abandoned. Lower labour taxes are welcome as they will raise the labour force participation and support growth, especially since the tax burden is relatively high compared to other Central European economies (Figure 1.20). Moreover, the tax structure is heavily skewed towards social security contributions (Figure 1.21). However, lower labour taxes also lead to a rise in the structural deficit by 0.7 percentage point in 2022, which eventually will have to be financed.

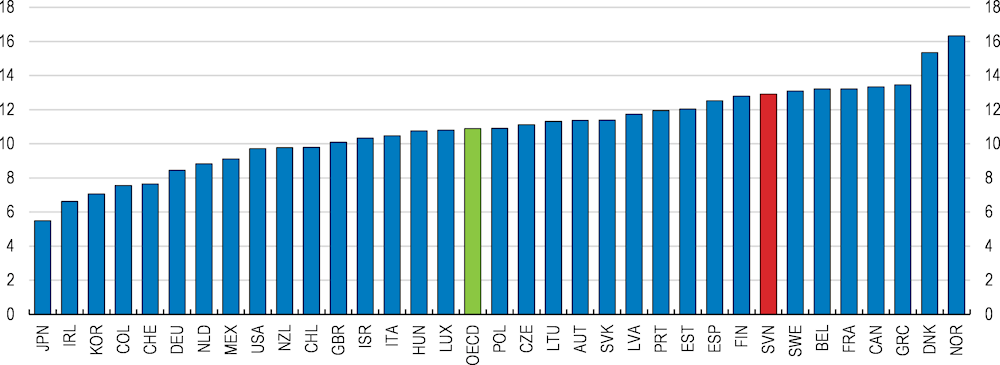

Figure 1.20. The tax burden is relatively high

Total tax revenue, as % of GDP, 2020 or latest available year

Figure 1.21. Revenues from social security contributions are the highest in the OECD

Tax revenue from social security contributions, as % of GDP, 2020

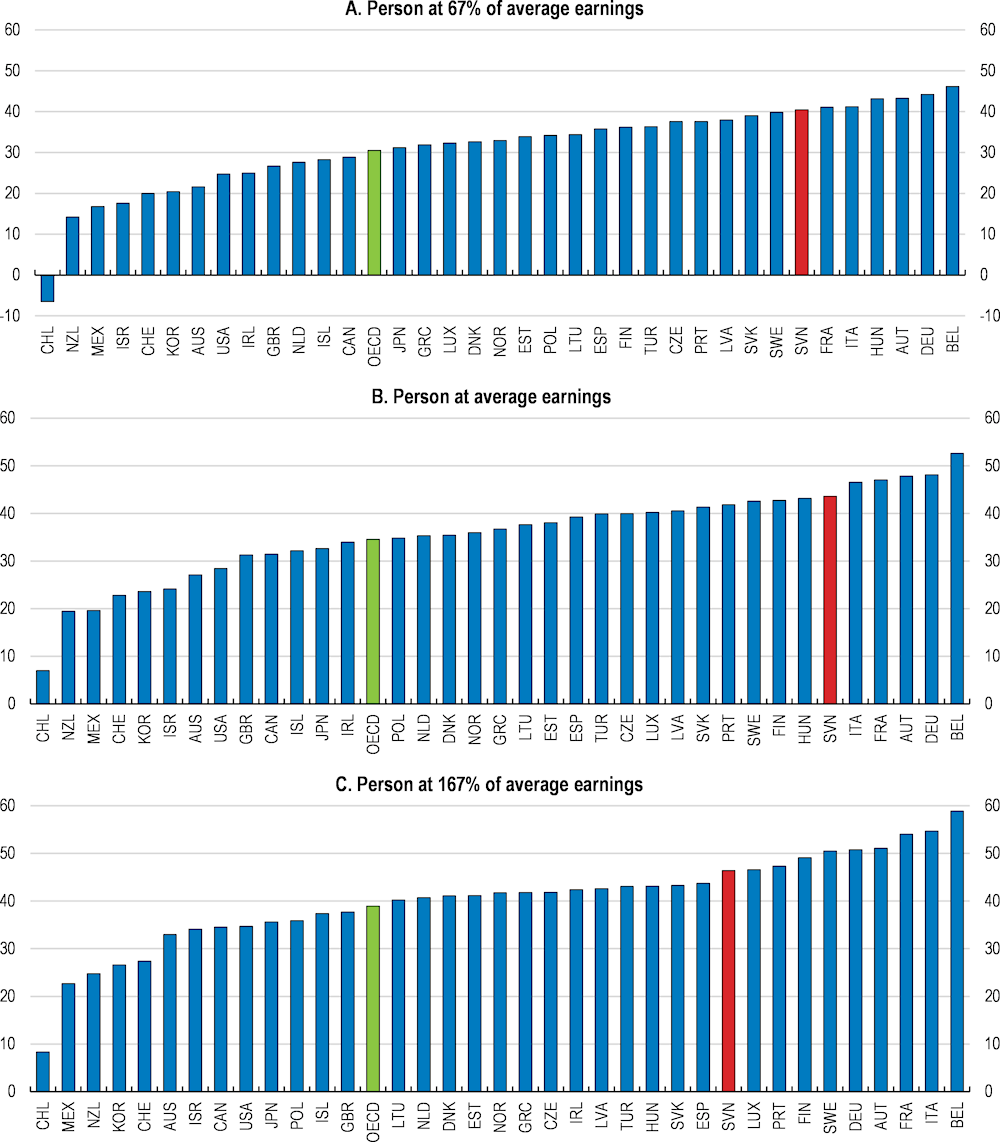

The labour tax burden is high for all income groups, which discourages moving into employment and up the income ladder (Figure 1.22, Panel A and B). About 87% of additional gross earnings are lost to higher taxes and lower social benefits when a jobless single person takes up employment, which is 11 percentage point higher than the OECD average (OECD, 2018[45]). This means that unemployed workers have fewer incentives to move into employment than elsewhere. Further reducing the high taxes on labour will strengthen work incentives (see above).

High labour taxation also affects the mobility of high-skilled workers. The average tax rates on higher incomes is high, although reforms in 2022 saw the reduction of the tax rate in the top tax bracket from 50% to 45%. Nonetheless, the high tax burden erodes wage gains for high-income workers, making it more difficult to attract and retain high-skilled workers (Figure 1.22, Panel C). In fact, immigration of high-skilled workers is low (see above). To attract foreign talent and Slovenians living abroad, the government could provide a lower, time-limited flat income tax for qualified workers starting from a certain income threshold, as in Denmark, the Netherlands or Spain. For instance, Denmark introduced in 1992 a flat income tax rate of 32% for high-earning foreigners (with monthly earnings above a EUR 9 356 in 2022), limited to seven years. Absent the special tax scheme, workers with earnings above the threshold would face a marginal tax rate of up to 52%. The scheme was very successful in attracting high-skilled foreign workers, with the number of foreigners paid above the eligibility threshold doubling relative to the number of foreigners paid slightly below the threshold after the scheme was introduced (Kleven et al., 2013[46]). Other options to attract foreign talent include easing immigration rules for high-skilled workers from outside the European Union. For example, residence and work permissions could be granted immediately for high-skilled workers (Chapter 2).

Making the tax mix more growth-friendly through further reducing labour taxes, including lower social security contribution rates, and implementing the announced property tax rise would help reduce the structural deficit and secure fiscal sustainability. Such a revenue-neutral reform could be implemented without hurting the poor by having a minimum threshold below which houses are not taxed. This would be relatively straightforward to implement as Slovenia has a system in place to value immovable property using market values. Other options to finance the cuts to labour taxes include raising indirect taxation and removing income tax exemptions. Currently, the standard VAT rate is 22%, although reduced rates of 5% and 9.5% apply for a wide range of goods and services, leading to an effective average VAT rate of 17%. Similarly, the personal income tax base is narrow, reflecting many exemptions and special tax provisions. In total, applying the standard VAT rate to all goods and services to achieve a broader-based VAT rate, and broadening the personal income tax base by reducing personal income tax allowances by 25% could finance an additional 10-percentage point reduction in social security contributions (OECD, 2018[47]).

The relatively high and growing wage bill in the public sector is another concern for the sustainability of public finances (Figure 1.23). This reflects a general lack of a structural approach to wage setting. Austerity measures after the financial crisis led to pay freezes for public sector employees. Then came strong wage hikes as public finances improved on the back of stronger economic growth in the mid-2010s. The government continued to increase public wages in the health sector throughout the pandemic, which might result in a structural expansion of public consumption if wages in other parts of the public sector catch up as foreseen by the unitary public pay system (see below). The result of this stop-and-go approach is that public wage policy has become pro-cyclical. A more structural approach to managing public wages would be to make public wage increases subject to private sector developments and sound budget constraints to moderate the growth of the wage bill as a share of GDP. This could be achieved through cash limits for the overall public wage bill as done, for instance, in the United Kingdom.

Figure 1.22. The labour tax wedge is high

Average tax wedge, for a single person (no child), as a % of labour cost, 2021

Note: The tax wedge is the sum of personal income tax and employee plus employer social security contributions together with any payroll tax less cash transfers.

Source: OECD Taxing Wages database.

Figure 1.23. The wage bill is comparatively high

Compensation of government employees, as % of GDP, 2020 or latest available year

The uniform public sector pay system is too rigid as pay rises in one sector trigger pay rises in all other sectors. For instance, public wages increased due to large COVID-related bonuses in the health sector in 2021 (see below). Higher wages in the health sector will help keep the sector competitive. However, this may have an impact on public finances by leading to strong wage increases in other public sectors (Fiscal Council of the Republic of Slovenia, 2022[48]). A more differentiated approach to public wages would allow to raise wages for occupations with recruitment problems such as in health and IT. In the United Kingdom, for instance, government departments can set higher wages for occupations with recruitment and retention problems such as in IT or health while overall wage negotiations remain subject to departmental spending limits set out by the Treasury (OECD, 2021[49]). Another approach is to link payment to performance as in France, as discussed in the last Survey (OECD, 2020[10]).

EU funds are providing an important economic stimulus. Additional money from the Recovery and Resilience Facility funds will finance investment in areas that the Survey identified as important for growth, notably in the green and digitalisation transformations, boosting the inflow of total EU funds to an average of 2.2% of GDP per year over 2021-26 (Box 1.1). However, a concern is that insufficient strategic planning, the fragmentation of public sector bodies, and weak inter-ministerial coordination are slowing down the implementation of key legislation, which is a pre-condition for the transfer of EU funds (OECD, 2018[50]; IMAD, 2021[51]) (see Chapter).

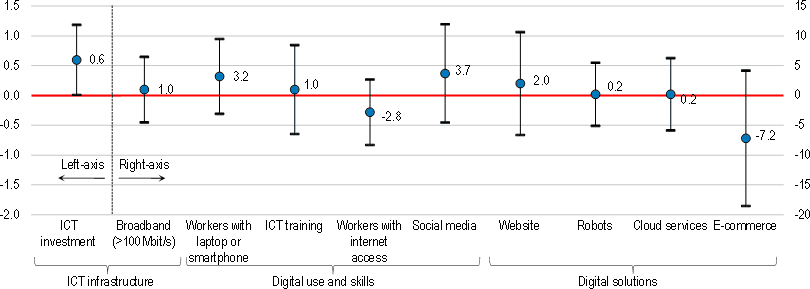

To secure the best use of EU funds, spending efficiency should be strengthened. In this respect, an issue is the top-down approach in allocating EU funds. First, priorities are identified at the EU level. Then, the government develops programmes to qualify for EU funding. In practical terms, this means that the government focuses on qualifying for EU funding, and subsequently identifies which areas to focus on. An example for such a top-down approach is the government’s digitalisation strategy, which relies heavily on financing from the EU’s Recovery and Resilience Facility funds to raise investment in ICT. However, relatively little efforts have been put into identifying market failures and other explanations for why firms are investing comparatively little in ICT. For instance, support is provided to both large firms and SMEs that have a digital strategy in place. In contrast, business surveys point to skill shortages as well as burdensome product market regulations as barriers to investment (European Investment Bank, 2022[52]). Better cost-benefit analysis will help make most out of EU funds, along the lines of the different social and economic needs as set out in the government’s digital strategy. To raise spending efficiency, project planning and selection should be improved. A way forward could be the use of input and output benchmarking to identify areas of relative weakness (see Chapter).

Table 1.5. Past recommendations on fiscal policy

|

Recommendations in previous Surveys |

Action taken since the 2020 Survey |

|---|---|

|

Maintain spending ceilings, pursue efficiency improvements, and adjust the structure of public spending |

No action taken. |

|

Focus fiscal consolidation on structural measures to increase cost efficiency. |

Consolidation was mostly based on temporary measures that are now expiring. A substantial rise in pension benefits was agreed. |

|

Increase recurrent taxes on real estate. |

No action taken. |

|

Adopt a credible and transparent expenditure rule, and appoint an independent and effective fiscal council to assess adherence. |

A fiscal council has been appointed. |

|

Focus fiscal consolidation on structural measures to increase cost efficiency in education, public administration and local government. |

Some social spending measures have been made contingent on GDP and employment growth. Public procurement was centralised. |

|

Avoid across-the-board cuts in the public-sector wage bill. Reinstate performance-related pay provisions, and use non-monetary incentives for public-sector workers. When cutting employment, reductions should avoid aggravating shortages of skills and competences. |

The freeze in promotions and annual conditional pay increments of public servants has been lifted. |

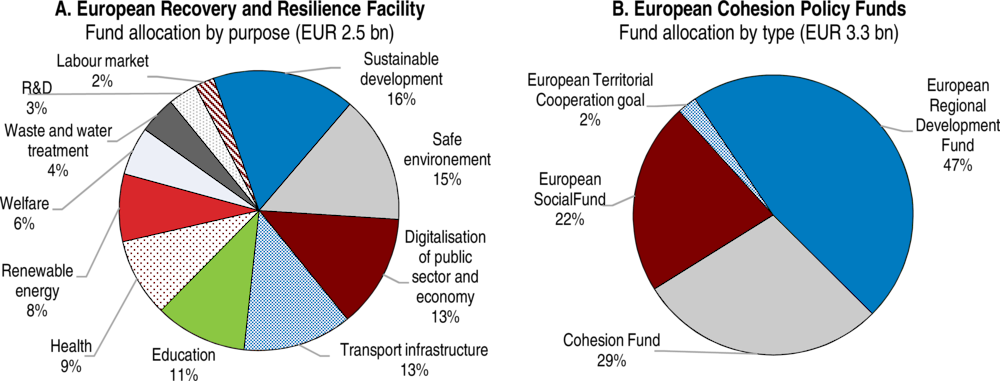

Box 1.1. EU funds will support the green and digital transitions

During the 2021-2027 programming period, Slovenia will receive European structural funds amounting to EUR 5.1 billion (6.4% of 2021 GDP). Nearly two-thirds of the funds are from the Cohesion Policy allocations, encompassing the European Regional Development Fund, the European Social Fund, the Cohesion Fund (for countries with a gross national income per capita below 90% EU-27 average), Just Transition Funds and the smaller European Interregional Fund, while the rest is related to the Common Agricultural Policy (European Commission, 2020[53]).

In addition, the NextGenerationEU temporary instruments will provide EUR 2.8 billion to boost the recovery from the pandemic’s social and economic damages as well as facilitate the green and digital transformation. The key component of the NextGenerationEU is the Recovery and Resilience Facility (RRF) which will provide EUR 2.5 billion, of which EUR 1.8 billion are grants and EUR 0.7 billion loans (Figure 1.24). Slovenia will also receive EUR 0.3 billion from the NextGenerationEU’s REACT programme (Recovery Assistance for Cohesion and the Territories of Europe) (Government of Slovenia, 2020[54]). The government plans to utilise the RRF in four priority areas: 1) the green transition, 2) the digital transformation, 3) the smart, sustainable and inclusive growth and 4) the health and welfare area, including investments and reforms in long-term care and social housing (Government of Slovenia, 2020[55]).

Nearly half of the funds will be allocated to the green transition (divided into grants and loans in equal proportions). Half of this will be used to secure a clean and safe environment. This includes investments to reduce environmental-related disasters, improve water infrastructure and services and strengthen the long-term resilience of forests to climate change. Funds will also be used to invest in sustainable mobility, by enhancing public transport infrastructures and increasing the use of alternative transport fuels, as well as improve energy efficiency and reduce greenhouse emissions, by raising the share of renewable energy sources. The rest of the funds will be used to improve energy efficiency in public buildings and support the circular economy.

Figure 1.24. EU resilience funds support many activities

Note: The Recovery and Resilience Facility (EUR 2.5 billion) consists of grants (EUR 1.8 billion) and loans (EUR 0.7 billion).

Source: Government of Slovenia; and European Commission.

A third of allocated funds (mostly as grants) goes to the development of smart, sustainable and inclusive growth. Resources will be devoted to investments in R&D and innovation, boost productivity and improve the business environment conditions to attract investments, as well as support structural reforms in the labour market and pension schemes to respond to challenges posed by the ageing population. Moreover, funds will also be used to reform the education system and vocational training to improve the future workforce’s competences in digitalisation and sustainable development. In addition, resources will be allocated to education and research infrastructures. Investments in the tourism sector and cultural heritage protection are also foreseen in this fund category.

Resources allocated to the health and welfare sector account for 15% of the RRF (mostly as grants). This will primarily focus on measures to support the digital transformation of the health system, improve skills of the healthcare personnel and ensure quality of care. Funds will also be used to strengthen long-term care and make it more accessible and inclusive. The plan also foresees investments in social housing to foster housing mobility and support disadvantaged social groups, such as deprived individuals and the young population.

The digital transformation will be entirely funded through grants (13% of the total RRF plan), including the digital transformation of the public sector and the economy. At the beginning of 2022, the government adopted the Digital Strategy for 2030 (Chapter 2) which was a pre-condition for the disbursement of the EU’s RRF funds.

As argued above, improvements in EU funds spending efficiency are necessary to ensure a full absorption of the allocations. For example, at the beginning of 2022 the ratio of spent over planned EU funds (i.e., Cohesion Policy funds allocated over the 2014-2020 programming period) ranged between 70 and 80% (depending on the type of funds) (European Commission, 2022[56]).

Long-term fiscal challenges need to be addressed

Reducing public debt is a primary concern for many governments. Public debt increased after the financial crisis and again after the COVID crisis. Since 2019, public debt has increased by more than 10 percentage points of GDP. Fiscal consolidation that can lead to a reduction in public debt, and thus to more fiscal space, has only started in 2022. More importantly, there is no medium-term plan to address ageing-related fiscal spending increases, although the Resilience and Recovery Fund Plan set milestones for health and pension reforms to be adopted in the medium term. A faster fiscal consolidation will be needed to prepare for rising pension spending, and restore fiscal space to respond to future crises. Much more decisive and timely action is needed in face of ageing-related spending pressures (see below).

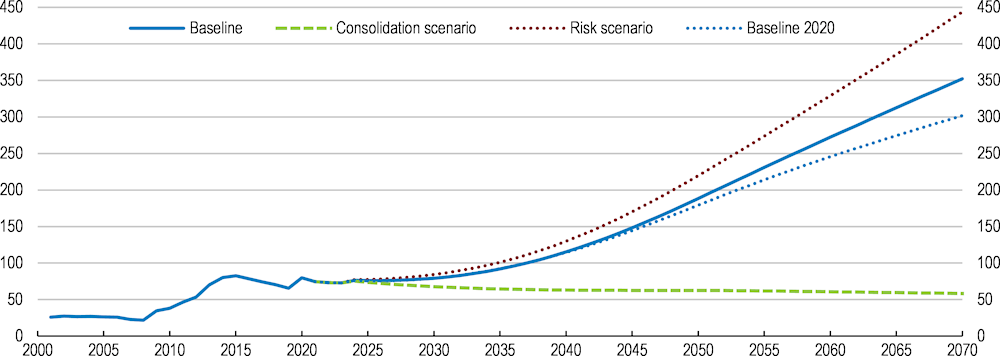

The public debt-to-GDP ratio will only increase moderately over the next decade, before rising considerably if some of the largest ageing-related spending pressures in the OECD are not contained (see below) (Figure 1.25, Baseline scenario). Compared with the last Survey, the public debt-to-GDP ratio is projected to worsen by more than 50 percentage points as a result of recent pension reforms that provided unfunded increases in pension benefit generosity (Baseline 2020 scenario) (OECD, 2020[10]; European Commission, 2021[57]). Public debt could be even higher in case long-term growth is lower than expected (Figure 1.25, Risk scenario).

Structural reforms are needed to secure fiscal sustainability. This includes the containment of projected ageing-related spending of around 7% of GDP by 2050, and which requires an improvement in the structural budget deficit of 3.7% of GDP by 2024, and thereafter a balanced primary balance (Figure 1.25, Consolidation scenario). Such a large fiscal challenge requires measures to sustain growth and reduce ageing-related spending, notably measures to incentivise longer working lives. In addition to increasing the statutory retirement age by 5 years, the tightening of eligibility criteria in unemployment benefit systems would raise the employment rate of older workers (+50) to the EU average, reducing fiscal spending by 3.5% of GDP as discussed in the last Survey (OECD, 2020[10]; OECD, 2022[58]). This would suffice to cover the projected increase in pension spending. However, additional efforts are needed to finance future health-related spending increases.

The recommended reforms in this Survey would substantially strengthen economic growth. The reforms would expand the tax base, creating fiscal space over the medium-term as structural fiscal gains amount to 5.1% of GDP (Box 1.2). For instance, aligning property taxation with the OECD average and broadening the VAT tax base by reducing exemptions would raise revenues by 1.2% of GDP and 1.8% of GDP, respectively. In addition, broadening the personal income tax base by reducing tax allowances by 25% could boost revenues by 0.8% of GDP (OECD, 2018[47]). The resulting fiscal space could be used to strengthen growth through lower labour taxes, or to counter the fiscal challenges associated with population ageing.

Figure 1.25. Spending pressures related to population ageing need to be addressed

General government debt, Maastricht definition, as % of GDP

Note: The baseline scenario assumes that increased spending on health and pensions will add an additional 8.2 percentage point of GDP to annual government spending by 2070, in line with European Commission (2021). The consolidation scenario assumes a primary balance of 0% of GDP from 2024, complying with medium-term objective from the government's Convergence Programme, which is subject to change. The risk scenario assumes that real GDP growth is 1 percentage point lower than currently projected for the entire simulation period, for example if structural reforms fail to raise productivity growth.

Source: Adapted from OECD (2021), OECD Economic Outlook: Statistics and Projections (database), June; Guillemette, Y. and D. Turner (2018), "The Long View: Scenarios for the World Economy to 2060", OECD Economic Policy Paper No. 22., OECD Publishing, Paris; and European Commission (2018), "The 2018 Ageing Report - Economic and Budgetary Projections for the 28 EU Member States (2016-2070)" Directorate-General for Economic and Financial Affairs.

Box 1.2. The impact of selected policy recommendations

Table 1.6 presents estimates of the fiscal impact of selected recommended reforms based on the OECD Economics Department Long-term Model. The results are merely indicative and do not allow for behavioural responses. Table 1.6 quantifies the impact on growth of the main reforms recommended in this Survey.

Table 1.6. Illustrative fiscal impact of recommended reforms

Fiscal savings (+) and costs (-) after 10 years

|

% of GDP |

|

|---|---|

|

Reduce labour taxes to the OECD average. |

-2.2 |

|

Broadening the personal income tax base by reducing tax allowances by 25%. |

+0.8 |

|

Align property taxation with the OECD average. |

+1.2 |

|

Reduce VAT exemptions to have a broader-based VAT rate. |

+1.8 |

|

Total revenues |

+1.6 |

|

Tighten eligibility criteria in unemployment benefit systems so as to align the employment rate of older workers with the EU average. |

+1.0 |

|

Gradually increase the statutory retirement age to 67 and change the pension indexation from today’s mix of 60% of wages and 40% of prices to full price indexation. |

+2.5 |

|

Total expenditures |

+3.5 |

Source: Simulations based on the OECD Economics Department Long-term Model and (OECD, 2018[47]).

Table 1.7. Illustrative impact on GDP per capita from structural reforms

Difference in GDP per capita level from the baseline 10 years after the reforms, %

|

% |

|

|---|---|

|

Competition reforms |

|

|

Reduce state-ownership and increase competition in service and network industries to levels of 5 best performing OECD countries. |

+2.5 |

|

Labour market reforms |

|

|

Reduce labour taxes to the OECD average while increasing less distortive taxes. |

+1.9 |

|

Tighten eligibility criteria in unemployment benefit systems and raise the minimum years of contributions required to retire so as to increase the effective retirement age by 2 years. |

+2.0 |

|

Ensure that minimum wages grow slower than the median wage. |

+1.1 |

|

Total impact on GDP per capita |

+7.5 |

Source: Simulations based on the OECD Economics Department Long-term Model.

Pension reforms are needed to secure fiscal sustainability

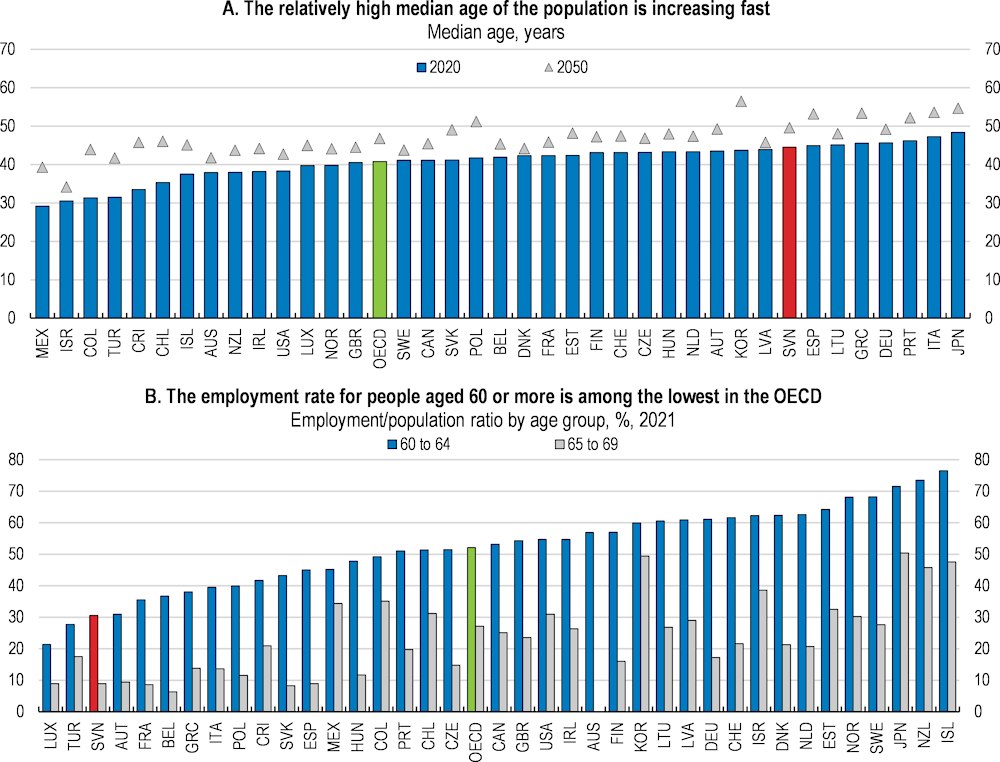

Population ageing is leading to a smaller and older workforce with negative impacts on the sustainability of the pension system. By 2050, the already relatively high median age of the population will further increase to around 50 years, implying that a larger share of the population will have reached 50 years than almost anywhere else in the OECD (Figure 1.26, Panel A).

A key challenge is one of the lowest effective retirement ages in the EU despite recent increases, leaving Slovenians with longer retirement spans than elsewhere. The employment rate for the age cohort 60-64 remains only half the OECD average while almost no member of the age cohort 65-69 continues to work (Figure 1.26, Panel B). This reflects a retirement age of 60 for workers with a full 40 years contribution period (OECD, 2021[15]). Longer retirement spans combined with the higher old-age dependency ratio will feed into higher spending pressures in both the pension and health systems. Indeed, the projected pension and health-related spending is already among the highest in the OECD and is expected to reach 16% of GDP by 2050 (European Commission, 2021[57]). Only a rise in the labour participation of older workers can bring the pensions system back on a sustainable track. This requires measures to work past the age of 65, including increasing the statutory retirement age and linking it to gains in life expectancy, raising the minimum years of contributions required to retire, and using lifetime incomes to determine pension benefits as opposed to the currently best 24 consecutive years of contributions as discussed in the last Survey (OECD, 2020[10]). In addition, there are other options to finance future pension spending increases, such as higher contribution rates, but such a measure might have negative impacts on labour supply (OECD, 2022[58]).

In addition, many older workers are using unemployment as pathway to early retirement as discussed in the last Survey (OECD, 2020[10]).Unlike in other OECD countries, the older unemployed are treated favourably as their benefit duration increases with age and they have their pension contributions paid longer than younger unemployed, reducing work incentives. Since 2020, older unemployed workers (58+) with an accumulated 28 years of contribution can receive unemployment benefits for 25 months, compared to 12 months for other workers with equal contributions. In order to strengthen work incentives for older workers, the last Survey recommended removing these pathways (OECD, 2020[10]). So far, however, no substantial measures have been taken (Table 1.8). In Austria and Germany, for instance, lower unemployment benefits duration for older unemployed persons led to higher transition rates to employment as discussed in the last Survey (OECD, 2020[10]). Curtailing age specific rules for unemployed would contain ageing-related spending pressures and would help align the employment rate of older workers with the OECD average. Such efforts should be implemented alongside measures to raise labour demand for older workers, including the abolition of seniority bonuses (see below).

Higher pension costs stem mainly from the generous annual pension indexation, which links pensions to 40 percent wage inflation and 60 percent price inflation, and allows for annual discretionary allowances as happened in 2021. As a result, the deficit in the pension system is projected to reach 2.3 percent of GDP in 2022, before doubling by 2030 (European Commission, 2021[57]). To reduce the need for intergenerational transfers, the government should link pension benefits entirely to price developments and eliminate annual discretionary allowances, as recommended in the last Survey.

The deficit of the pension system also reflects that most workers contribute less over their work lives than they receive in pension benefits. As a result, low-and middle-income groups contribute much less than they receive in pension benefits, leading to large transfers in the system, and reducing working and saving incentives (OECD, 2020[10]). This reflects policy measures such as a minimum pension. In consequence, low-income earners with a full career receive a very high net replacement rate of 95% compared with an OECD average of 69% (OECD, 2022[58]). To reduce the deficit, lowering the minimum reference wage is one option to be considered.

Figure 1.26. The median age is high while employment rates among older people remain low

Table 1.8. Past recommendations on the pension system

|

Recommendations in previous Surveys |

Action taken since the 2020 Survey |

|---|---|

|

Increase the statutory retirement age to 67 for both men and women. Link further increases, if needed, to gains in life expectancy. |

Part of early retirement period for child-caring can be substituted with higher annual accruals. |

|

Index pension benefits to price developments. |

No action taken. |

|

Adjust the parameters of the public pension system to better align contributions and benefits for all contributors. |

No action taken. |

|

Make bonuses and maluses symmetric and applicable at a fixed point, such as the statutory retirement age. |

No action taken. |

|

Make enrolment in the second pillar an opt-out choice. |

No action taken. |

|

Increase the ceiling for tax exempt contributions and reduce the associated tax advantages; introduce matching contributions for low wage workers. |

No action taken. |

|

Increase the statutory and minimum pension (for workers with qualifying contribution periods) ages, and link them to life expectancy. |

No action taken. |

|

Calculate pension rights based on lifetime contributions. |

No action taken. |

Preparing the health and long-term care systems for ageing-related challenges

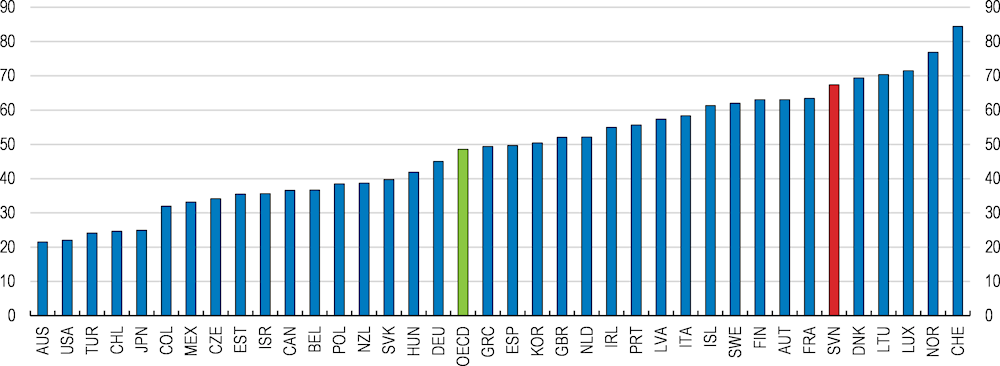

Addressing structural issues in the health sector is key to fiscal sustainability. This includes ensuring competitive wages in the health sector. Moreover, public long-term care spending as a share of GDP is relatively low (Figure 1.27). Ageing will lead to different and higher demand for health and long-term care services. Providing needed services while containing cost pressures will require reforms that promote efficiency and satisfy changing health demands.

Figure 1.27. Public long-term care spending is relatively low

Public long-term care spending as % of GDP, 2019

Source: European Commission (2021), The 2021 Ageing Report: Economic and Budgetary Projections for the EU Member States (2019-2070), Directorate-General for Economic and Financial Affairs, Institutional Paper 079, Luxembourg.

Wages in the healthcare sector wages experienced a rise in 2021 due to large COVID-related bonuses. Keeping wages in the health care sector competitive is necessary to avoid health care specialists leaving for better paying jobs elsewhere. However, the rigid and uniform public pay system foresees that the strong wage hike in the health sector may have an impact on public finances by leading to strong wage increases in other public sectors (Fiscal Council of the Republic of Slovenia, 2022[48]). As argued above, a more flexible approach is needed to wage setting in the public sector. This entails wage increases for occupations with recruitment problems such as health. To keep the public wage bill from spiralling out, overall public sector wage increases be subject to sound budget constraints as argued above.

The long-term care system is underdeveloped and fragmented. There are many different providers with their own eligibility criteria and financing, leading to uneven access (IMAD, 2018[59]). Home care is underdeveloped and there is little rehabilitation to enable people to stay in or return to their home (Oliveira Hashiguchi and Llena-Nozal, 2020[60]). To create a level playing field and allow people to organise their own care, the parliament passed a Long-Term Care Act in 2021 that provides a unified framework for long-term care, including a single point of access with common eligibility criteria. A new insurance will come into force in 2025 with pooled funding from the health and pension insurance. However, transfers from the state budget will be necessary to bridge funding gaps for long-term care. Instead, the system should be based on sustainable long-term funding. This entails strengthening health insurance for long-term care. In addition, equal access for all should be secured. This could entail complementing health insurance with vouchers for low-income individuals, as done in Germany.

Table 1.9. Past recommendations on health care

|

Recommendations in previous Surveys |

Action taken since the 2020 Survey |

|---|---|

|

Make the per-patient payment (capitation) and the fees-for-services cost reflective. |

No action taken. |

|

Use the per-patient payment to attract GPs to underserved areas. |

No action taken. |

|

Establish required minimum interventions for maintaining services, while giving management greater responsibility in service supply decisions. |

No action taken. |

|

Create a nation-wide monitoring system of quality, safety and efficiency. |

No action taken. |

|

Introduce selective public tenders for health services. |

No action taken. |

|

Use updated reimbursements for all acute services. |

No action taken. |

|

Ensure competitive salaries and performance incentives for doctors. |

Salaries have been increased in 2022 but the implementation has been halted by the Constitutional Court. |

|

Introduce integrated long-term care with common financing mechanisms and eligibility criteria. |

The Long-Term-Care Act was adopted in 2021, providing common financing mechanisms and eligibility criteria. |

|

Facilitate entry of private home care providers through quality and output-focused tenders. |

Long Term Care Act has been adopted in 2021, integrating assessment criteria. |

|

Equalise the contribution rates to the health fund. |

No action taken. |

|

Allow hospitals to adjust their health services to changing demand, including by closing under-performing departments. |

No action taken. |

|

Give hospitals greater scope to engage in multi-year investments and to keep their realised cost savings. |

The Act on Provision of Funds for Investments in Slovenian Healthcare 2021-2031 has been adopted. |

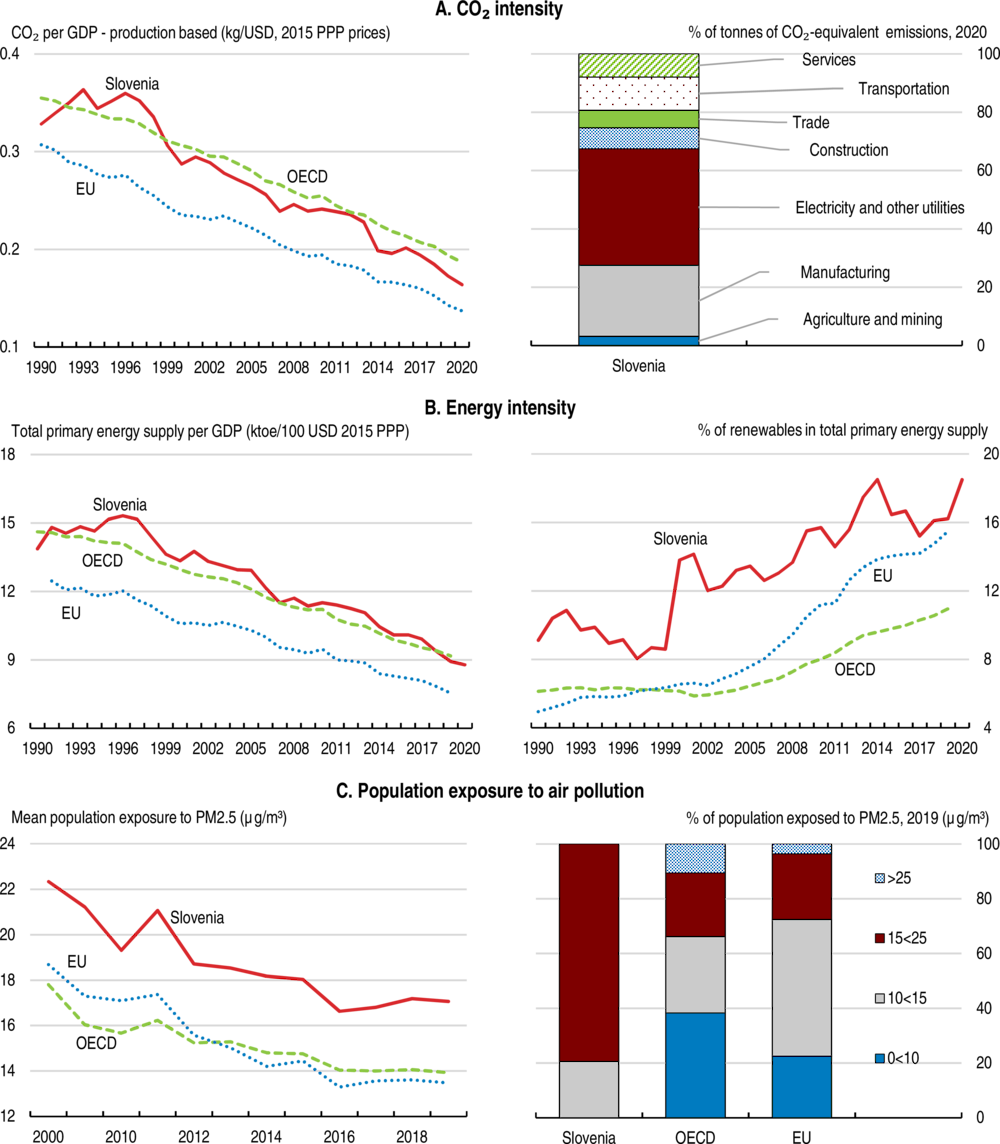

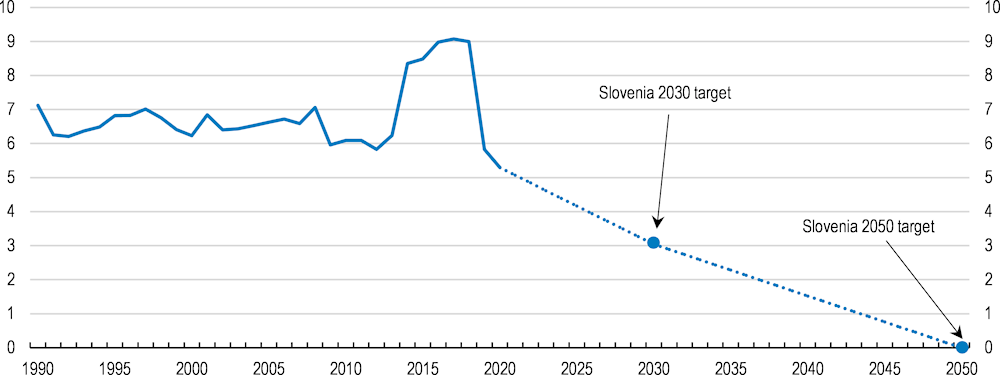

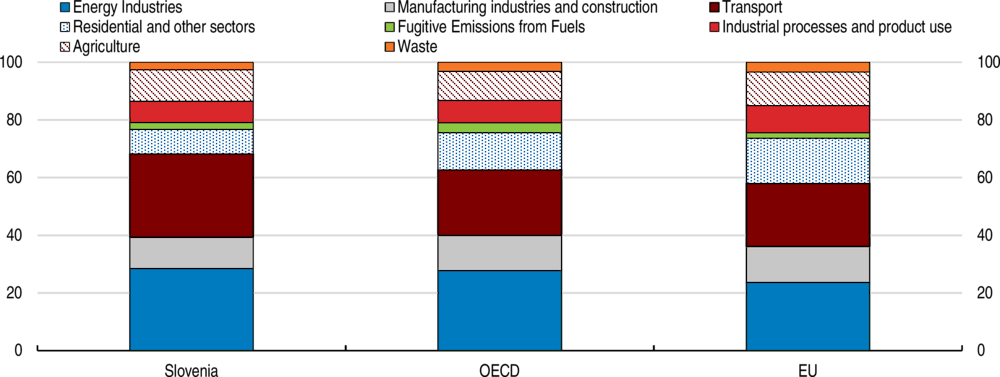

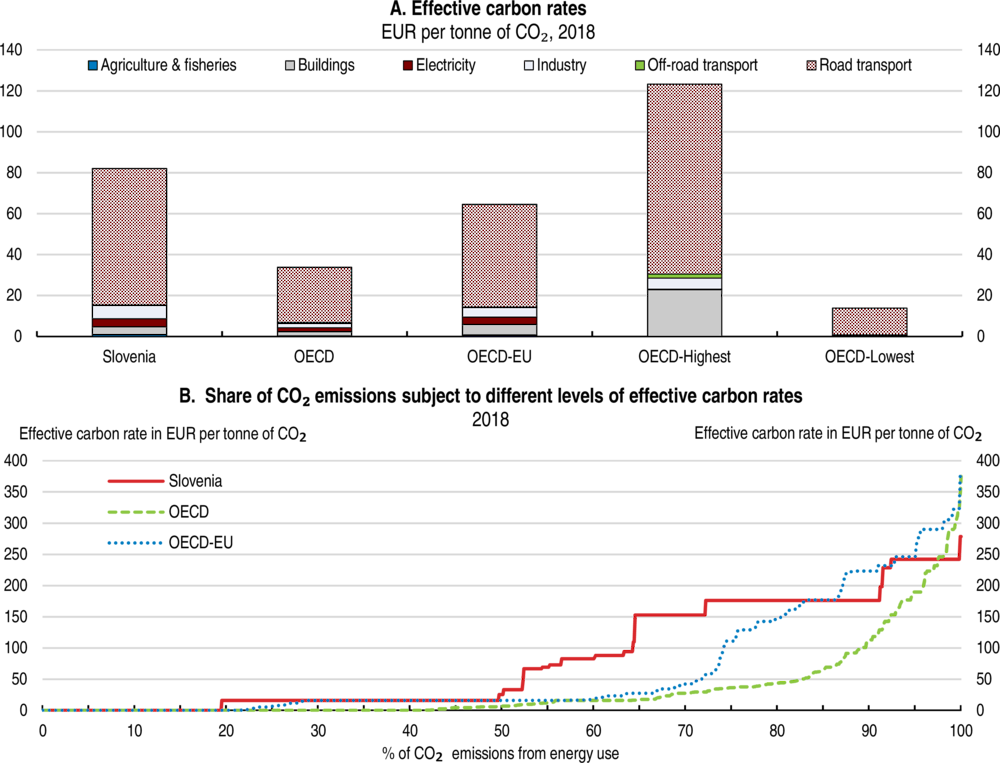

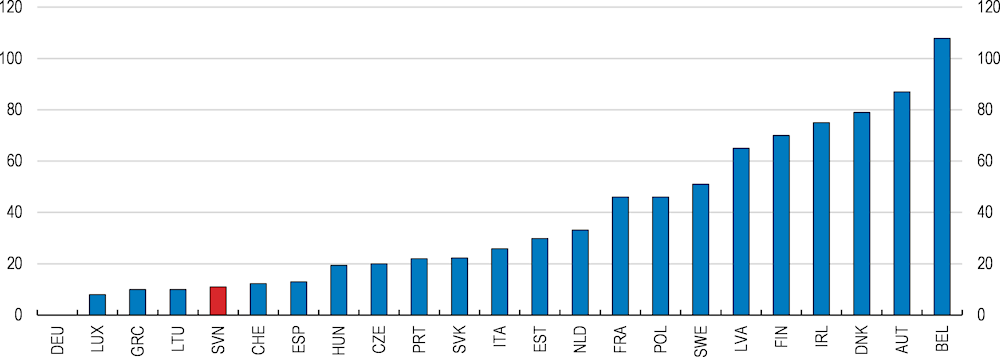

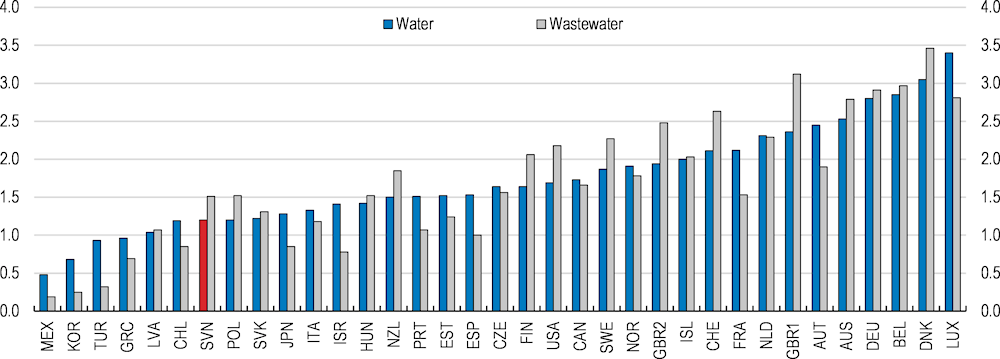

Promoting more environmentally sustainable growth