Urban Sila

OECD Economic Surveys: Switzerland 2024

2. Macroeconomic developments and policy challenges

Abstract

The economy is facing uncertain prospects. Activity and trade have weakened. Monetary policy has tightened appropriately but uncertainty around the persistence of inflation remains. Rising interest rates globally also heighten risks and vulnerability in the financial system, highlighting the need for sustained vigilance. Fiscal policy is facing hard choices to meet growing spending needs due to heightened geopolitical tensions, ageing, and the green transition. Structural reform will be needed to slow increases in expenditure and/or strengthen tax revenues.

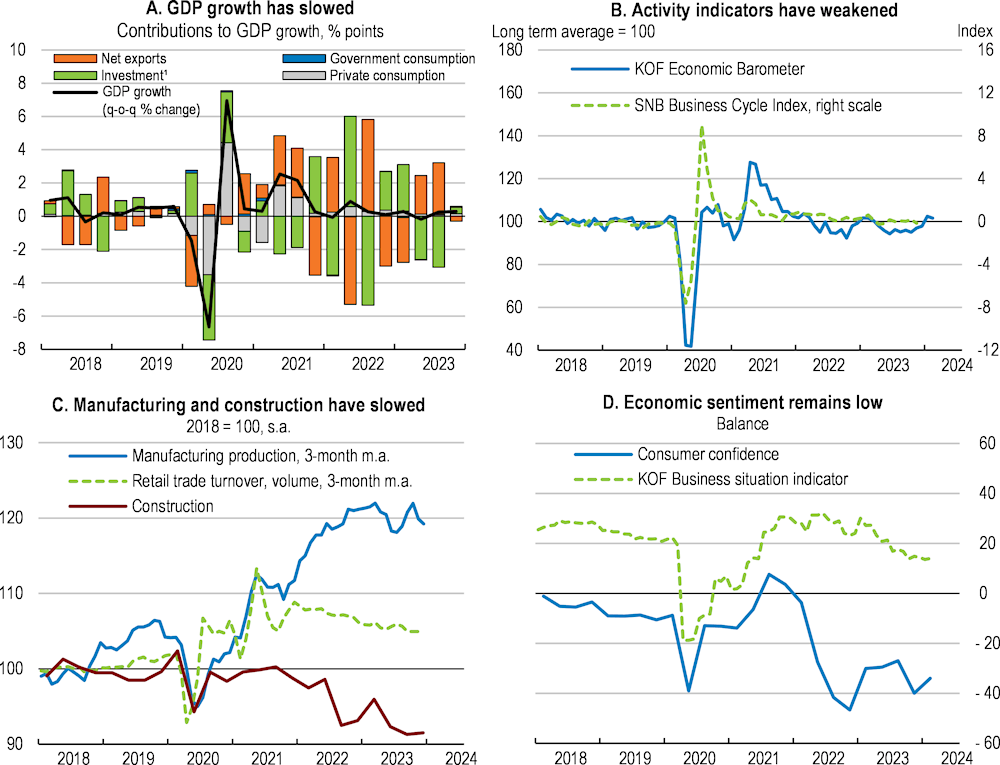

The economy has slowed amid slower global growth

Economic activity has slowed over the past year. Weak foreign demand, adverse impact of inflation on domestic purchasing power and tightened financing conditions weigh on activity. The KOF economic barometer and the SNB’s business cycle indicator point to a loss of momentum in the economy (Figure 2.1). Manufacturing production has stalled and prospects are subdued, due to slowing demand in trading partners. Weak exports and muted prospects hamper investment in equipment and construction. Growth in household consumption remains solid, supporting growth in services, despite consumer confidence remaining low (Figure 2.1).

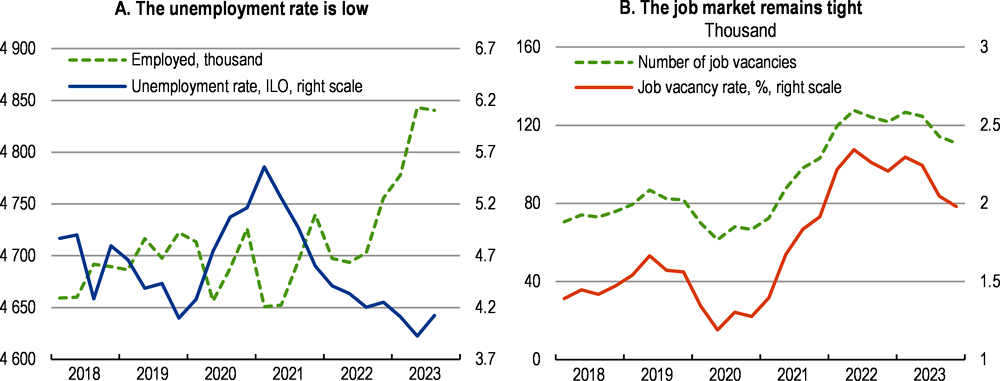

The labour market has been robust, notwithstanding some recent weakening. Employment growth has been strong and broad-based across economic sectors during 2023. The ILO unemployment rate stood at 3.9% in the second quarter of 2023, the lowest level in 15 years, before inching up in the third quarter (Figure 2.2). The number of job vacancies remains elevated. The job market remains tight, despite some recent easing (Figure 2.2), and companies continue reporting difficulties in recruiting personnel (SNB, 2023a and 2023b).

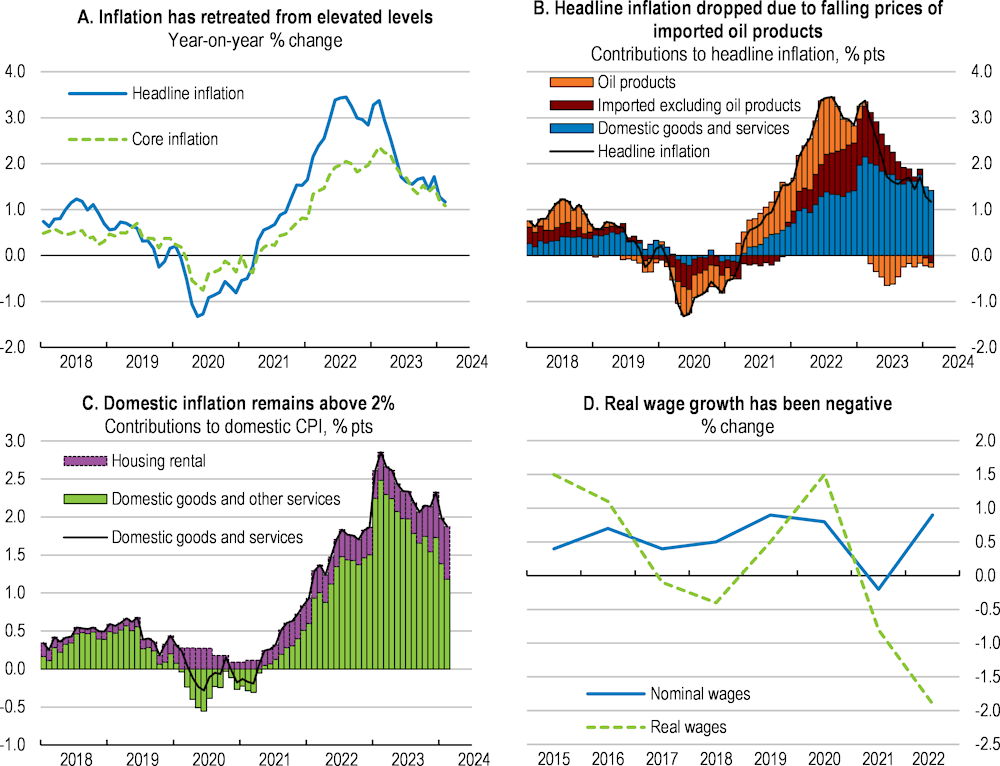

Consumer price inflation has retreated but inflationary pressures remain. Headline inflation returned to within the 0-2% target range in June of 2023, after peaking at 3.5% in August 2022 (Figure 2.3). The decline largely reflected lower prices (year-on-year) of imported oil products and decreasing inflation of other imported products. On the other hand, consumer price inflation of domestic goods, services and housing rents has remained above - or close to - two percent. Core inflation has also retreated (Figure 2.3). Despite growth in nominal wages, real wages have continued to fall. Short-term inflation expectations rose above the 0-2% range. In the fourth quarter of 2023 companies still expected inflation to stay at 1.8%, close to the upper end of the target range. In contrast, longer-term expectations have remained within the 0-2% range of price stability (SNB, 2023a, 2023b).

Figure 2.1. The Swiss economy has slowed over the past year

Figure 2.2. The labour market has been robust

Figure 2.3. Consumer price inflation has retreated but inflation pressures remain

GDP will grow only modestly

Real GDP growth is projected to remain below potential in 2024, reflecting the impact of tighter monetary policy on global economic activity and domestic demand. The economy is projected to grow by 0.9% in 2024 and 1.4% in 2025 (Table 2.1). In 2024, Switzerland’s GDP will be boosted by international sports events, indicating an even weaker underlying growth momentum. Rent increases linked to the rising mortgage reference rate, rising VAT rates and increases in electricity prices in the domestic retail market in 2024 will push inflation higher. Consumer price inflation is projected to temporarily go above 2% over the course of 2024, before moderating again in early 2025. Higher inflation will slow domestic consumption growth. Given modest growth going forward, the unemployment rate will increase slightly. Real wage growth will turn positive in 2025.

Uncertainty surrounding the outlook is high. Risks in relation to energy supply and prices remain, notably for the 2023/24 winter. Energy shortages could push energy prices up again, further dampening purchasing power and slowing the economy. There is also uncertainty around the persistence of inflation and the impact of tighter global monetary policy on global growth. Further monetary tightening worldwide or in Switzerland, if needed, could heighten the risks surrounding high indebtedness and repricing of real estate, with repercussions on the financial sector. On the other hand, favourable resolution of geopolitical tensions would result in higher trade, revived confidence and higher growth and stability.

Table 2.1. Macroeconomic indicators and projections

Annual percentage change, volume (2015 prices)

|

2020 |

2021 |

2022 |

Estimates and projections |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Current prices (billion CHF) |

2023 |

2024 |

2025 |

|||

|

Gross domestic product (GDP) |

695.8 |

5.4 |

2.7 |

0.8 |

0.9 |

1.4 |

|

Private consumption |

361.3 |

1.8 |

4.2 |

2.1 |

0.9 |

1.1 |

|

Government consumption |

84.5 |

3.3 |

-0.8 |

-0.5 |

0.9 |

0.8 |

|

Gross fixed capital formation |

187.9 |

2.8 |

1.2 |

-2.0 |

-2.9 |

0.7 |

|

Housing |

21.7 |

-1.9 |

-2.3 |

-2.4 |

-3.0 |

0.7 |

|

Business |

142.8 |

4.5 |

2.2 |

-1.9 |

-2.9 |

0.7 |

|

Government |

23.4 |

-3.1 |

-2.6 |

-2.2 |

-2.0 |

0.9 |

|

Final domestic demand |

633.7 |

2.3 |

2.6 |

0.6 |

-0.2 |

0.9 |

|

Stockbuilding1 |

18.4 |

-2.1 |

-0.6 |

0.5 |

-1.3 |

0.0 |

|

Total domestic demand |

652.1 |

0.0 |

1.8 |

1.0 |

-1.7 |

1.0 |

|

Exports of goods and services |

445.9 |

13.6 |

6.3 |

2.7 |

2.9 |

3.5 |

|

Imports of goods and services |

402.2 |

5.6 |

6.0 |

3.7 |

-0.2 |

3.3 |

|

Net exports1 |

43.7 |

5.4 |

0.9 |

-0.2 |

2.3 |

0.6 |

|

Other indicators (growth rates, unless specified) |

||||||

|

GDP (sport events adjusted) |

704.4 |

5.1 |

2.5 |

1.3 |

0.5 |

1.8 |

|

Potential GDP |

. . |

1.5 |

1.5 |

1.4 |

1.3 |

1.2 |

|

Output gap² |

. . |

0.0 |

1.2 |

0.5 |

0.2 |

0.4 |

|

Employment |

. . |

-0.2 |

0.6 |

2.8 |

0.6 |

0.4 |

|

Unemployment rate (% of labour force) |

. . |

5.1 |

4.3 |

4.0 |

4.4 |

4.4 |

|

GDP deflator |

. . |

1.2 |

2.5 |

1.0 |

1.6 |

1.5 |

|

Consumer price index |

. . |

0.6 |

2.8 |

2.1 |

1.9 |

1.4 |

|

Core consumer price index³ |

. . |

0.3 |

1.7 |

1.8 |

1.6 |

1.3 |

|

Household saving ratio, net (% of disposable income) |

. . |

20.5 |

19.3 |

19.3 |

19.4 |

19.3 |

|

Current account balance (% of GDP) |

. . |

6.9 |

9.4 |

7.6 |

6.7 |

7.4 |

|

General government financial balance (% of GDP) |

. . |

-0.3 |

1.2 |

0.9 |

0.7 |

0.6 |

|

Underlying government primary financial balance² |

. . |

-0.3 |

0.8 |

0.8 |

0.7 |

0.6 |

|

General government gross debt (% of GDP) |

. . |

41.5 |

37.7 |

36.8 |

36.3 |

35.8 |

|

General government net debt (% of GDP) |

. . |

-20.3 |

-4.4 |

-5.2 |

-5.8 |

-6.3 |

|

Three-month money market rate, average |

. . |

-0.7 |

-0.1 |

1.5 |

1.5 |

0.9 |

|

Ten-year government bond yield, average |

. . |

-0.2 |

0.8 |

1.0 |

0.9 |

1.1 |

1. Contribution to changes in real GDP.

2. Percentage of potential GDP.

3. Consumer price index excluding food and energy.

Source: OECD Economic Outlook database.

Table 2.2. Events that could lead to major changes in the outlook

|

Shock |

Possible impact |

|---|---|

|

Global energy and food crisis |

An intensification of energy and food supply disruptions would push inflation up and cause a contraction in global trade, leading to a recession. |

|

Further heightening of geopolitical tensions |

Geopolitical instability would increase uncertainty and weaken both domestic and external demand, slowing growth. |

|

Global trade tensions may deteriorate further, with an extension of export restrictions |

Further fragmentation of global supply chains and barriers to trade would weigh on growth and contribute to inflationary pressures. |

|

Sudden steep rises in interest rates and major house price correction |

A large correction in housing prices could expose vulnerabilities in the financial system, causing a crisis in the financial sector that could feed back to the real economy. In addition, sudden rises in interest rates would sharply increase debt-servicing costs for highly leveraged households and investors, raising the risk of defaults. |

Monetary policy should remain tight

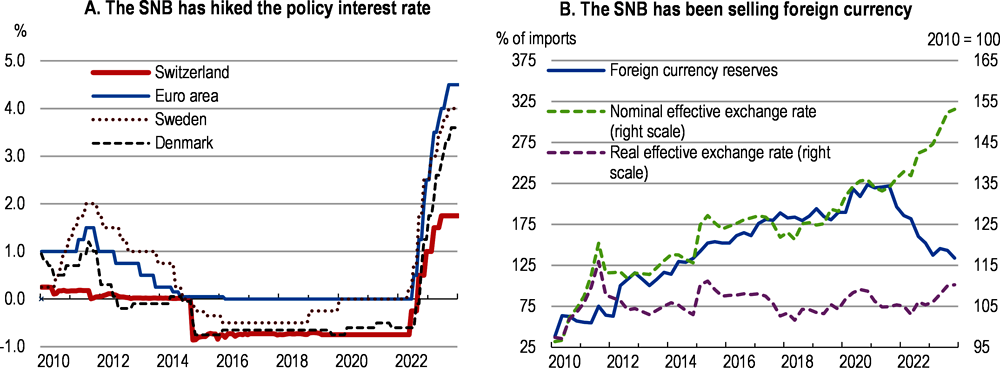

Between June 2022 and June 2023, the Swiss National Bank (SNB) hiked the policy interest rate by 250 basis points, from -0.75% to 1.75% (Figure 2.4), exiting the negative interest environment after seven years. To steer the money market rate close to the policy rate, the SNB has undertaken steps to absorb liquidity – via repo transactions and the issuance of SNB Bills – and adjusted its policy of tiering sight deposits. Bank sight deposits held at the SNB are remunerated at the SNB policy rate only up to a certain threshold, and for the rest banks are now remunerated at a 0.5 percentage point discount. With such tiered remuneration the SNB facilitates trading of sight deposits in the money market and ensures interest rates stay close to the policy rate.

The monetary policy stance should remain tight until inflation is durably within the 0-2% band. Monetary policy should continue to closely follow inflation and economic developments in Switzerland and abroad. Under current conditions, inflation is still expected to return temporarily above the target band over 2024 due to expected rent and VAT increases, as well as rises in electricity prices. Volatile energy prices could trigger new pressures on import prices.

The SNB has remained active in the foreign exchange market. To ensure appropriate monetary conditions, foreign exchange interventions by the SNB over recent quarters focused mostly on selling foreign currency (Figure 2.4), contributing to the monetary policy tightening. As a welcome side effect, this has contributed to reducing the large balance sheet of the SNB.

Figure 2.4. Monetary policy has been tightened

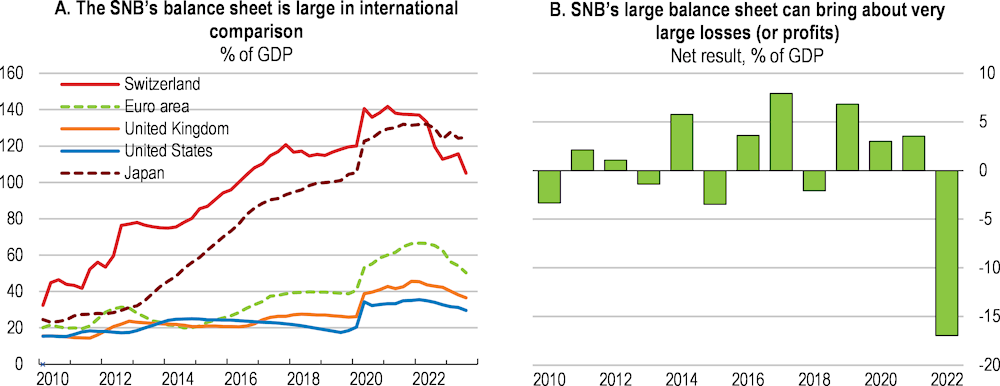

The still large size of the SNB’s balance sheet raises risks and challenges, as changes in valuations can bring about very large losses or profits. This in turn can affect the SNB’s equity and raises uncertainty about profit distribution. The SNB’s balance sheet rose steeply after 2010, reaching 140% of GDP in 2020, before declining to 105% in the second quarter of 2023, still high in international comparison (Figure 2.5). In 2022, after several years of large profits, the SNB posted a loss of CHF 132 billion (17% of GDP), largely due to valuation changes of foreign currency positions (SNB, 2023c), precluding a profit distribution in 2023. In 2023, the SNB reported another loss in the order of CHF 3.2 billion, precluding profit distribution in 2024. Most notably, there is to be no transfer to the federal budget or the cantons. However, recent large losses are not expected to disturb effective policymaking by the SNB in safeguarding price and financial stability (Zeng and Li, 2023).

Box 2.1. The SNB’s investment strategy

In applying its investment policy, the SNB has two main objectives. The first is to ensure that its balance sheet can be used for monetary policy purposes at any time. This means that the SNB must be able to expand or shrink the balance sheet as necessary to maintain appropriate monetary conditions. The second objective is to preserve the value of currency reserves in the long term.

The SNB’s balance sheet amounts to more than 100% of Swiss GDP and the assets consist mostly of investments in foreign currencies (91%), gold (6%) and, to a lesser extent, financial assets in Swiss francs (1%) and other assets (2%). Most foreign currency holdings are in USD or EUR.

The bond portfolio had an average duration of 4.4 years at the end of 2022 and mainly comprises government bonds. Investments are broadly diversified in each market across maturities, so that large volumes can be either bought or sold with a minimal impact on prices. Swiss franc bonds are passively managed and primarily contains bonds issued by the Confederation, cantons, municipalities and foreign borrowers, as well as the Swiss Pfandbriefe. The average duration of the portfolio was 7.6 years in 2022. Equities are managed passively based on a benchmark, consisting largely of equity indices in mainly advanced economies.

Source: SNB (2022).

Figure 2.5. The large size of the SNB’s balance sheet raises risks and challenges

Source: OECD Economic Outlook database; Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System; ECB; Bank of Japan; Bank of England; SNB and OECD calculations.

The SNB has taken steps to strengthen the resilience of its balance sheet. It has limited profit distributions and revised its provisioning for currency reserves to help maintain adequate capital. It has also strengthened communication by transparently communicating about its investment strategy and potential volatility in profits. The SNB should continue reviewing its investment strategy and maintain adequate safeguards to dampen risks arising from its large balance sheet.

Countering risks to financial stability

Ensuring sufficient buffers and adequate supervision in the banking sector

Steep rises in interest rates, a weakening economy and overall uncertainty heighten risks and vulnerability in the financial system. The exit from the negative interest rate environment and rising interest rates generally boost net interest income of banks. However, steep interest rate increases can trigger substantial repricing of assets, causing losses for investors and financial institutions. In addition, the weakening economy impacts the viability of businesses and worsens the loan portfolios of financial institutions. The SNB’s stress scenario analysis (done in 2023 only for domestically focused banks, as comprehensive analysis was not yet possible for the combined UBS/Credit Suisse bank) suggests that capital buffers should ensure adequate resilience overall of domestically focused banks’ (SNB, 2023d). Adequate capital buffers and effective risk management need to be maintained to counter the risks.

The state-facilitated acquisition of Credit Suisse by UBS, announced in March 2023, effectively stabilised the growing crisis within Credit Suisse and tamed risks of spill-overs, thus safeguarding financial stability, but it raises new risks and challenges. The holders of wiped-out AT1 securities and a group of Credit Suisse shareholders have filed lawsuits against the Swiss authorities, which might lead to costly litigation and uncertain outcomes. The restructuring of Credit Suisse’s business will entail sizable job losses. UBS announced 3 000 jobs would be cut in Switzerland alone, but it is likely that currently tight labour market will absorb much of this workforce. With the two largest banks now being combined, questions of competition arise. UBS operates and competes in the global market for financial services, but domestically, the new combined bank will have roughly 25% market share in domestic deposits and loans (SNB, 2023d). The Swiss Competition Authority is reviewing the takeover and submitted its first report to the Swiss Financial Market Supervisory Authority (FINMA) in September 2023.

UBS – already a global systemically important bank before the merger – has thus become even larger and according to the “too big to fail” (TBTF) regulations, it must meet even stricter regulatory requirements. FINMA has granted UBS a transitory period from end-2025 to the beginning of 2030 at the latest, to comply with the capital requirements that reflect the increase in its size and domestic market share. During the integration and restructuring process, the authorities should continue with close supervision and monitoring of the merged bank.

The acquisition was carried out without making use of the existing TBTF resolution regime, raising questions on optimal regulation and supervision of large banks going forward: How could a global systemically important bank that met regulatory requirements destabilise so rapidly and when, how and on what legal basis can a supervisor intervene in a bank that meets the quantitative regulatory requirements? Important lessons should be drawn from this case to strengthen regulation in Switzerland as well as internationally. The Federal Council is undertaking a review of the TBTF framework, with the final report and conclusions to be published in spring 2024. A parliamentary inquiry commission will investigate the management and responsibilities of the authorities in the management of the takeover.

Box 2.2. The takeover of Credit Suisse by UBS

In March 2023, the authorities – Federal Council, FINMA and the SNB – facilitated a take-over of ailing Credit Suisse by UBS. After years of risk management issues, inadequate internal controls, financial losses, top management overhauls and restructuring attempts, the failure of two otherwise unrelated US banks in March 2023 triggered severe pressure on Credit Suisse. While Credit Suisse met the regulatory capital and liquidity requirements, it became increasingly likely that it would not be able to stabilise by itself. The package of measures announced on 19 March 2023, centring around the acquisition by UBS and ample liquidity support, rapidly stabilised the situation and prevented further spill-overs to the Swiss and global financial system.

In addition to the existing liquidity-shortage financing facility (LSFF) and emergency liquidity assistance (ELA), two new instruments – additional emergency liquidity assistance (ELA+) and a liquidity assistance loan secured by a federal default guarantee (public liquidity backstop) – were introduced under emergency law to provide ample liquidity assistance. In addition, the federal government provided UBS with a second-tranche loss protection guarantee of up to CHF 9 billion (available only after a UBS first loss tranche of CHF 5 billion) for a specific portfolio of difficult-to-assess Credit Suisse assets. The acquisition was expedited under emergency law and speedy approval of the transaction, without Credit Suisse and UBS shareholders voting on it. The public intervention triggered a full (CHF 15 billion) write-down of Credit Suisse’s Additional Tier 1 (AT1) securities, while Credit Suisse shareholders benefited from the purchase price of UBS for Credit Suisse shares.

The take-over was formally completed in June 2023. UBS announced significant downsizing of previous Credit Suisse business, most notably a reduction of its investment banking business. In August 2023, UBS announced that it terminated the CHF 9 billion loss-protection guarantee it received from the Federal government. Moreover, the liquidity assistance under the additional emergency liquidity assistance (ELA+) and the public liquidity backstop has been repaid in full.

The SNB reported some preliminary observations and lessons learnt in its 2023 Financial Stability Report (SNB, 2023d). In the report, the SNB highlighted the need for a review of the TBTF framework to facilitate early intervention. In times of stress, focus on regulatory metrics such as capital and liquidity ratios proved to be too narrow. Moreover, Credit Suisse was confronted with deposit outflows which were more severe than assumed under the liquidity regulations. The SNB called for the need for banks to cancel the interest payments on AT1 instruments when incurring losses and be able to write down AT1-securities earlier to absorb losses and increase the chance of revival. In addition, banks should have higher liquidity buffers and a higher level of assets on balance sheets that can be pledged to the SNB as collateral to obtain emergency liquidity assistance. The Federal Department of Finance, in collaboration with FINMA and the SNB, is conducting a more in-depth investigation into the Credit Suisse crisis which will also be delivered to Swiss parliamentarians in spring 2024.

FINMA likewise issued a report on the Credit Suisse crisis in December 2023 (FINMA, 2023a). In the report FINMA notes that it took “far-reaching and invasive” measures to rectify the deficiencies in Credit Suisse’s corporate governance and risk management before the crisis in early 2023. FINMA assesses that in intensifying its supervisory and enforcement activities at Credit Suisse, it reached the limits of its legal options and it therefore calls for a stronger legal basis for intervention. More specifically, it calls for instruments such as the Senior Managers Regime (clear allocation of responsibilities, violations attributable to individuals, and the need for awareness on the part of top management of biggest risks), the power to impose fines, and more stringent rules regarding corporate governance. FINMA also indicated that it was ready to strengthen its supervisory practice and would step up its review of stabilisation measures, which would be welcome.

Monitoring vulnerabilities in the housing market

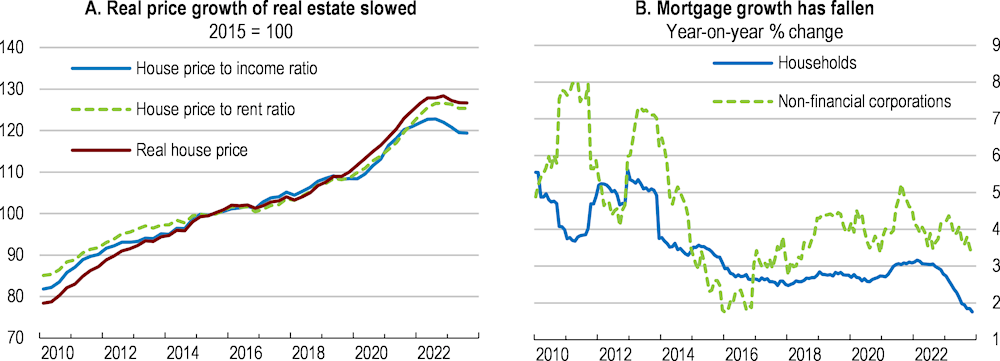

The housing market has started to show signs of cooling, after years of steep growth in real estate prices (Figure 2.6). In real terms, residential real estate price growth has declined in the owner-occupied segment and turned negative in the investment property segment (SNB, 2023d and 2023b). Mortgage growth has fallen, too. Past rises of interest rates will still take time to be fully reflected in market dynamics and mortgage growth will likely slow further. According to various indicators and model-based estimates of the SNB, taking into account the state of the economy, interest rates, incomes and rents, current apartment prices imply overvaluation of Swiss real estate of up to 40% (SNB, 2023d). Demographic factors and supply constraints have contributed to this.

Figure 2.6. The housing market has started to cool

Vulnerabilities in the residential real estate market persist, despite some cooling. Given stretched valuations, large interest rate hikes or other shocks could result in steep price corrections, leading to deteriorated mortgage portfolios of banks. In addition, the proportion of loans with a repricing maturity of less than six months (the time before the interest rate on a mortgage is reset) has been on the rise. Vulnerabilities are particularly acute in the residential investment property segment, where commercial investors are more likely to default on their debt than owner-occupiers. In this segment, in 2022, a significant share of new loans (15%) was characterised by both a short repricing maturity and high loan-to-income ratio (above 20), making them particularly vulnerable to rising interest rates (SNB, 2023d).

Close monitoring of risks stemming from the housing market and adequate buffers should be maintained. The sectoral countercyclical capital buffer (CCyB) was reactivated in September 2022 at 2.5% of risk-weighted exposures secured by residential property in Switzerland, a welcome step that will help ensure the banking sector’s resilience (the CCyB stance is proposed by the SNB – after consulting with FINMA – and then the Federal Council makes the decision). Earlier, with effect from January 1st, 2020, the Swiss Bankers Association tightened self-regulation for mortgage loans on the investment property market, by requiring higher down-payments and faster mortgage repayment. Switzerland would however benefit from a broader toolkit of macroprudential measures that consider affordability, for instance debt-to-income and debt-service-to-income limits on mortgage loans. As recommended in previous Surveys (OECD 2017, 2019, 2022a), the framework for setting macroprudential rules should be strengthened, with the authorities given clear and strong mandates to propose and calibrate the tools. Currently, the rules are set in agreement with the Swiss Bankers Association, which may impact timeliness and stringency (IMF, 2019).

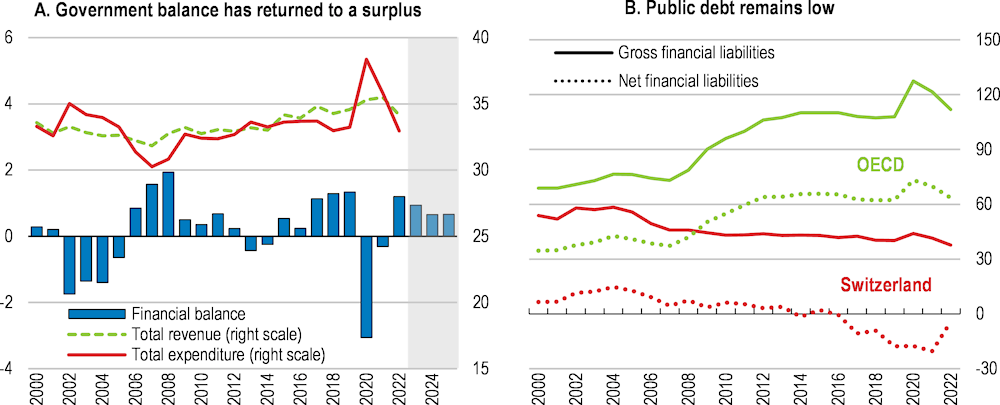

A broadly neutral fiscal stance is warranted

After extraordinary measures during the COVID-19 crisis and two years of fiscal deficits, the general government recorded a surplus of 1.2% of GDP in 2022 (Figure 2.7). Despite weakening GDP growth, another general-government surplus is expected for 2023, while the federal government ran a deficit. Although the federal government had to write off expected profit sharing from the SNB (0.25% of GDP) due to balance sheet losses, the rescue mechanism for the electricity industry (0.5% of GDP) was not needed (Federal Council, 2023a). In addition, in August 2023, UBS announced that it terminated the loss-protection guarantee it received from the Federal government in the amount of CHF 9 billion (1.1% of GDP) upon the take-over of Credit Suisse. The guarantee did not represent an immediate financial burden to the federal budget, but its termination eliminates contingency risks to government finances.

Figure 2.7. Government balance has returned to a surplus and the fiscal position is robust

General government, % of GDP

Public finances remain robust with ample fiscal buffers. Gross general government debt at 37% of GDP in 2022 is low in international comparison (Figure 2.7). The public debt ratio has remained stable at around 40-45% of GDP for the past 15 years, in contrast to many other OECD economies. This has been achieved within the framework of the federal debt brake rule (along with cantonal fiscal rules) that aims to use fiscal policy as a stabilisation tool over the economic cycle (while allowing for extraordinary needs) as well as to pursue fiscal sustainability by keeping nominal debt stable (i.e., a declining debt-to-GDP ratio).

Box 2.3. Switzerland refrained from discretionary support measures during the energy crisis

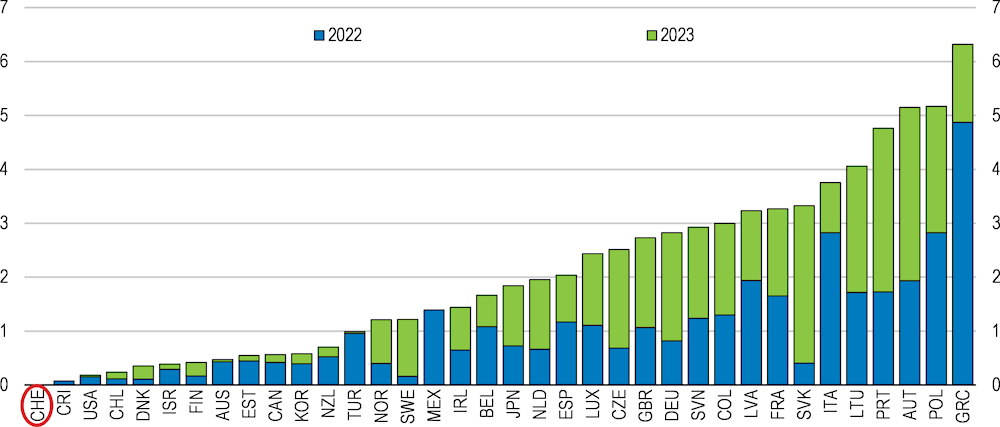

Russia’s aggression against Ukraine led to steep rises in energy and commodity prices, as well as severe supply disruptions in energy markets. Absent domestic natural gas production, and with gas accounting for 16% of energy consumption (IEA, 2020), Switzerland was affected by the shock. However, the authorities refrained from introducing the support measures to households and companies that were common among other European countries (Figure 2.8).

Dominance of renewable power in electricity production, a relatively small share of energy in households’ total consumption, the strength of the Swiss franc and regulation of the retail market helped reduce the adverse impact of rising energy prices in Switzerland. Existing contingency plans for energy shortages (including recommendations to reduce natural gas and electricity use) also helped the authorities to effectively address the situation, although the cause of the disruption turned out to be very different from what had been envisaged in past risk assessments (FONES, 2021).

Figure 2.8. : No new government support measures during the energy crisis

Energy support measures, % of GDP

Notes: Support measures are taken in gross terms, i.e., not accounting for the effect of possible accompanying energy-related revenue increasing measures, such as windfall profit taxes on energy companies. Where government plans have been announced but not legislated, they are incorporated if it is deemed clear that they will be implemented in a shape close to that announced. Gross fiscal costs reflect a combination of official estimates and assumptions on how energy prices and energy consumption may evolve when the support measures are in place. Costs are estimates for both 2022 and 2023, naturally subject to greater uncertainty in the current year. Measures corresponding to categories “Credit and equity support” and “Other” have been excluded. When a given measure spans more than one year, its total fiscal costs are assumed to be uniformly spread across months. For measures with no officially announced end-date, an expiry date is assumed and the fraction of the gross fiscal costs that pertains to 2022-23 has been retained.

Source: Castle, et al. (2023).

A broadly neutral fiscal stance is appropriate over 2024 and 2025 given the moderately growing economy. This translates into low general government surpluses over this period. Automatic stabilisers are strong in Switzerland and have historically been successful in dampening the effects of adverse shocks on the Swiss economy (see Chapter 5). The stabilisers mainly consist of direct government taxes (on income, profits and wealth), accounting for roughly 70% of total tax revenues, that adjust in response to economic fluctuations without the need for discretionary policy decisions, as well as an increase in various social benefits. The automatic stabilisers should operate freely to cushion the growth slowdown and a slight uptick in unemployment. However, fiscal policy should not get in the way of monetary policy in driving down inflation and inflation expectations. The decision to extend the amortisation period (the prescribed time within the debt brake rule during which extraordinary deficit needs to be compensated through the ordinary budget) for reducing the “COVID debt” from 6 years to 12 years is welcome and will avert overly tight fiscal policy over the coming years.

Box 2.4. The debt brake rule

The debt brake rule is a central element of the Swiss fiscal framework at the federal level. It subjects the Confederation’s fiscal policy to a binding rule. Its principles were accepted by popular vote in December 2001 and its core provisions are enshrined in the Federal Constitution (article 126). Details are set out in the Financial Budget Act.

The debt brake is designed to ensure that fiscal policy remains sustainable over the long term by aiming to keep nominal debt stable (i.e. a declining debt-to-GDP ratio). The rule also considers the economic cycle to help smooth growth fluctuations. It is a structural deficit rule that limits expenditures to the amount of structural (i.e. cyclically adjusted) revenues. Thus, the debt brake does not require budgets to be balanced on an annual basis, but only over an economic cycle. Within this mechanism, total federal government expenditures are kept relatively independent from the cycle whereas tax revenues act as automatic stabilizers. Actual deviations from the limit set by the rule result in a credit or debit to the so-called “compensation account”. Deficits in this account must be considered when setting the new expenditures ceiling for the following year and eliminated in the subsequent years. Moreover, in principle, positive balances from underspending can only be used to reduce debt.

In extraordinary circumstances (such as severe recessions, pandemics or natural disasters), the expenditures ceiling can be raised by a qualified majority of both chambers of parliament, whereby a binding rule also applies for the extraordinary budget. Extraordinary receipts and expenditures are recorded on an amortisation account and any deficits on the amortisation account due to extraordinary expenditures must be covered over the course of six years by means of surpluses in the ordinary budget. In special situations, the parliament has the power to extend the six-year deadline.

Source: OECD (2022a).

Growing spending needs call for reviewing expenditures and strengthening revenues

Switzerland needs to find a way of addressing its growing spending needs. Spending needs for climate change adaptation and to meet greenhouse gas reduction commitments are growing. The need for spending on defence has risen. Interest rates on new public debt are going up. In the longer term, public spending faces significant pressures due to population ageing (see below). Accordingly, Switzerland needs to curb growth in public spending or find new sources of public revenue to abide by the debt brake rule and safeguard fiscal sustainability.

The government estimates that from 2025 to the end of 2027, the equivalent of 0.9% of GDP in savings will have to be found in the federal budget to observe the debt brake rule (Federal Council, 2023b). Spending for Ukrainian refugees, which was previously (2022-2024) recorded as extraordinary are included in this figure.

In early 2023, the Federal Council announced a set of measures to cut spending and improve revenue of the Federal budget. These include among others, slowing growth in army spending, waiving the contribution for Horizon Europe in favour of transitional measures until agreement is found with the EU, reducing contributions to the railway infrastructure funds and linear cuts to other expenditures. At the same time, the federal contribution to unemployment insurance is to be reduced (in view of accumulating surpluses of the unemployment insurance), the cantonal share of direct federal tax to be reduced (in favour of the federal government) and taxes on imported electric vehicles to be introduced starting in 2024. Some of these measures need to be passed by parliament. The overall effort is commendable, and some measures might raise efficiency (the cut to railway funds). However, other measures will not necessarily have an impact on the general government finances as they distribute between the levels of government. Moreover, the cut to Horizon Europe is expected to be only temporary. More structural measures are therefore needed in the medium to long term.

Relying on spending reviews as part of the budgeting process can help to realise fiscal savings. Switzerland has a tradition of carefully evaluating the economic rationale and the cost and benefits of introducing new policies. However, tools to systematically and regularly review existing expenditures are lacking. Several OECD countries have benefitted from regular spending reviews that helped to identify savings or expenditure reallocation measures or to improve effectiveness within programmes and policies. In Denmark, spending reviews have been undertaken for more than 20 years. They are led by the Ministry of Finance and inform budget negotiations and decisions on multi-annual budget agreements. In Ireland, spending reviews – integrated with the annual budget process – aim to improve the allocation of public expenditure across all areas of government, by systematically assessing the efficiency and effectiveness. In Norway, recommendations from the final spending review report have a direct effect on the budget process. In the UK, spending reviews are the main mechanism through which departmental budgets are set. Having a strong spending review framework that builds on OECD Best Practices for Spending Reviews (Tryggvadottir, 2022) can make the administration better equipped to face emerging fiscal pressures and enable it to better respond to changing government priorities.

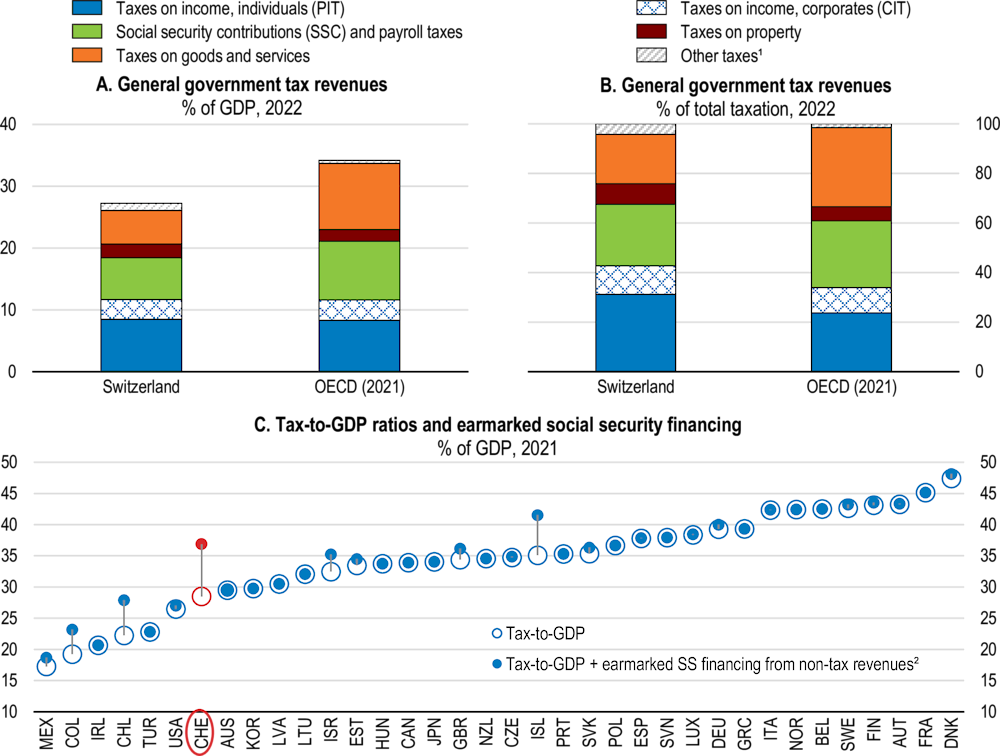

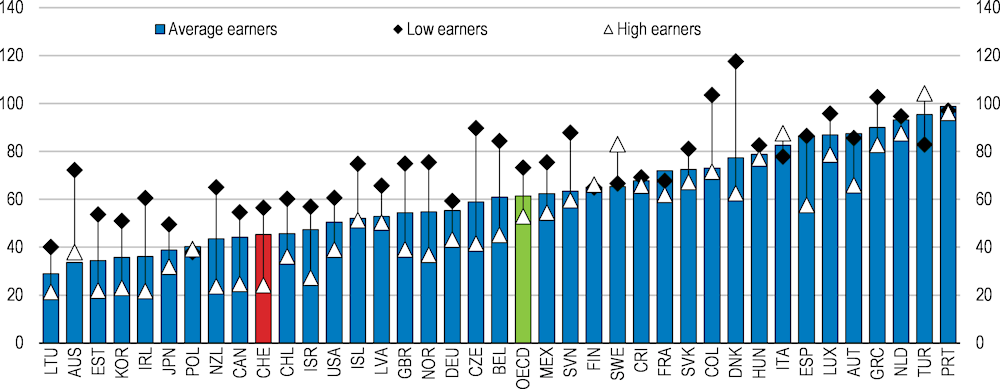

Strengthening tax revenues can also help to conform with the debt brake rule while meeting growing spending needs related to defence, ageing and climate change. As discussed in the last Survey (OECD, 2022a), Switzerland’s tax revenues as a share of GDP are relatively low (Figure 2.9), although when including also the financing of health care costs through compulsory private insurance, the burden on households is markedly higher (Figure 2.9, panel C). Tax revenues are titled towards direct taxation (personal income tax, corporate income tax and social security contributions). The standard VAT rate is 8.1% and the GDP share of VAT revenues is among the lowest in the OECD. Broadening the base of the VAT, improving compliance (as planned) and increasing the standard VAT rate (in addition to the 0.4 percentage point hike to help finance the first pension pillar), could raise revenues. There is also room to increase revenues from real estate taxation, notably the recurrent tax on immovable property which is low in international comparison. Lowering disincentives to work for second earners, for example by moving from family- to individual-based taxation (more on this below), could raise labour participation and hence tax revenues. Switzerland has adopted the OECD-initiated global minimum 15% corporate tax on multinational companies, effective from 1 January 2024 onwards. However, the exact impact on tax revenues in Switzerland is uncertain, depending on behavioural responses of companies and policy steps of cantons.

Figure 2.9. Tax revenues are titled towards direct taxation

1Includes unallocable between personal and corporate income tax.

2Earmarked financing of social security financing from non-tax revenues includes voluntary contributions to government and compulsory contributions to the private sector.

Source: OECD Revenue Statistics database; OECD (2023), Revenue Statistics 2023.

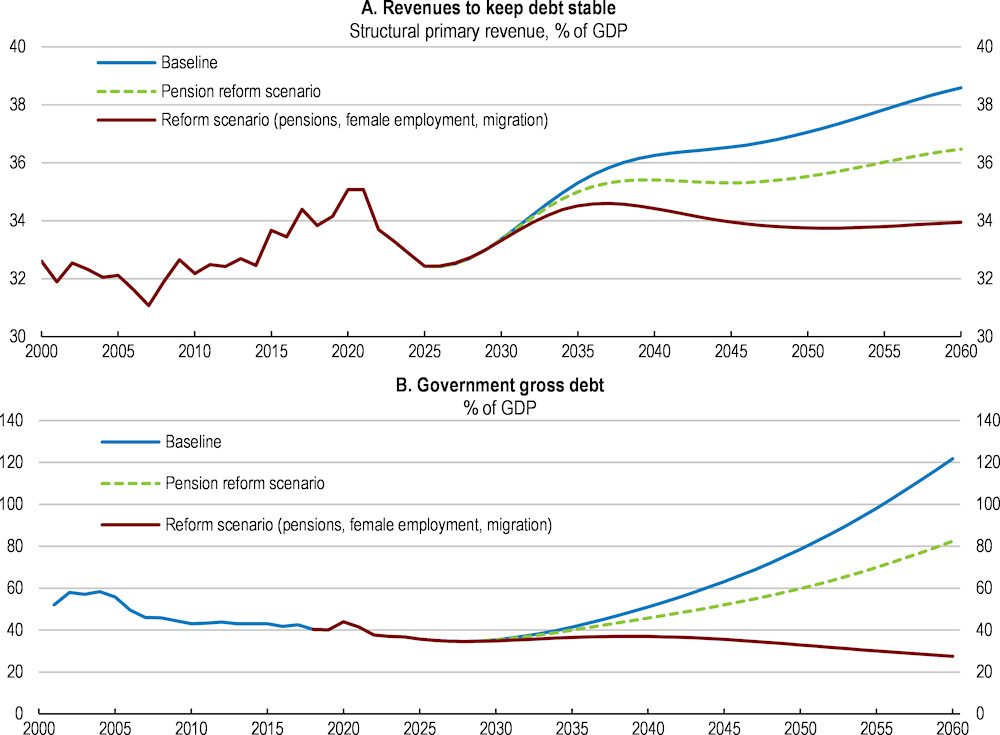

Addressing the long-term sustainability of pensions

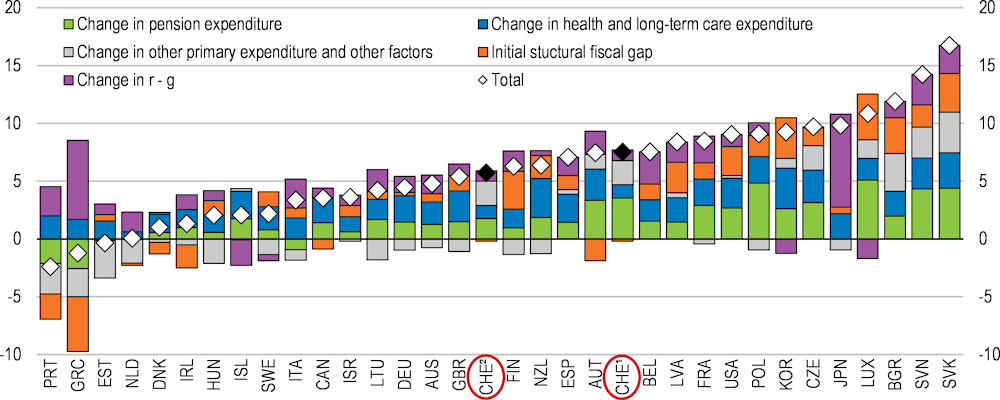

Switzerland faces looming fiscal pressures, despite internationally low public debt and a positive net asset position. Although projections far into the future are subject to significant uncertainty, long-term scenarios based on Guillemette and Turner (2021) suggest that to hold the debt-to-GDP ratio steady at current levels, without policy changes, fiscal pressure would increase by close to 6% percentage points of GDP by 2060 while maintaining current public service standards and benefits (Figure 2.10). National projections by the Federal Department of Finance (FDF 2021) indicate lower fiscal pressures. A major source of pressures comes from population ageing that raises costs related to pensions, healthcare and long-term care (Figure 2.12). To safeguard fiscal sustainability, Switzerland must either significantly raise public revenues, e.g., taxes, undertake structural reform to limit increases in ageing costs or seriously cut other primary spending. An ambitious reform package combining labour market reforms to raise employment rates with reforms to the pension system to lengthen working lives and keep the effective retirement age rising could help cut the projected increase in fiscal pressure (see also Chapter 3). Labour market reforms to increase employment rates of women and attract more migrant workers to counter declines in domestic workforce would put public debt on a sustainable path (Figure 2.10).

Figure 2.10. Ageing creates fiscal pressures

Note: The projections are illustrative and differ substantially from the latest national projections (FDF, 2021). The OECD Long-term model considers demographics but also the Baumol effect – i.e., the tendency for the relative price of services to increase over time. It is also assumed that other primary expenditures (other than health and pensions) are affected by ageing. The assumption is that governments would seek to provide a constant level of services in real per capita terms. This translates into higher fiscal pressure when the employment / population ratio falls. This component adds about 2 pp of GDP by 2060 (see Box 1.1 and Figure 1.13 in Guillemette and Turner, 2021). In addition, the scenarios assume that public pensions will grow at ½ the pace of wages, in line with the current Swiss law. The simulations use population projections of the United Nations. Panel A shows the required increase in public revenues to keep debt-to-GDP ratio steady amid rising costs due to ageing. Panel B assumes that rising ageing costs are financed with deficits (applied on a zero structural primary balance scenario). In both cases, pension reform entails the following: The retirement age gradually rises to 67 in 2034, and by two thirds of the expected gain in life expectancy thereafter. The reform scenario entails the pension reform, the female prime-age (25-54) employment rate converging with that of men by 2050 and net immigration rising from 45 000 annually to 75 000 by 2030.

Source: OECD Long-term Economic Model, OECD calculations.

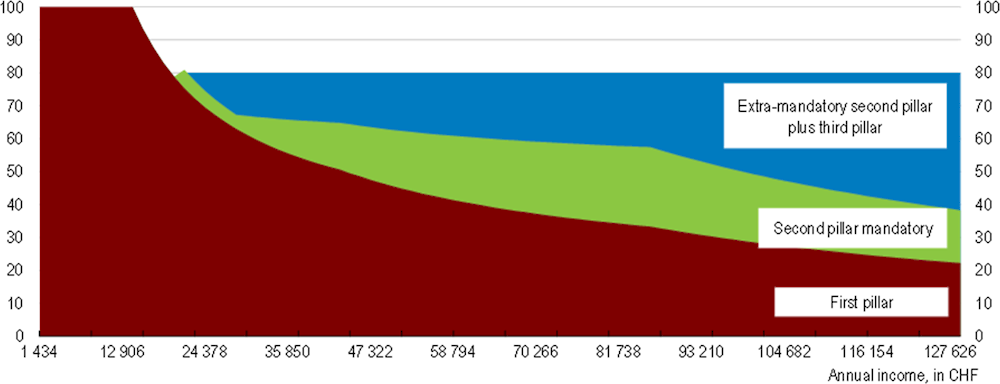

Box 2.5. The pension system

The Swiss pension system is organised around three pillars, to mitigate individual and public finance risks. The first two pillars together amount to at least 60% of the beneficiary's last income. As income rises, the share of the second and third-pillar in total pensions rises and the share of the first pillar falls (see Figure 2.11).

The first pillar is a public pay-as-you-go system, which is the main source of income for low-income earners. The contribution rate is the same for all employees at 8.7% of gross earnings (half of it being paid by employers). Pension benefits depend on the number of contribution years, the average salary over the career and some potential bonuses. To get a full pension, a worker should contribute every year from age 20. Each missing year implies a penalty of 1/44th. In addition, a couple cannot receive more than 150% of the maximum benefit. There are bonuses to compensate for years taking care of children and relatives.

The second pillar is an occupational scheme and many firms choose to provide a voluntary component. The second pillar grew out of employer initiatives that began in the 19th century and became mandatory in 1985. It is mostly akin to a defined-contribution scheme. Most pension funds are private. Consolidation within the sector reduced their number from around 3 600 in 1985 to about 1 500 in 2018 and increased their average size. The scheme complements the replacement rate from the first pillar for a large share of the population.

The third pillar offers tax incentives to contribute to pension savings managed by banks and insurance companies. The scheme provides incentives with a maximum contribution of CHF 7 056 per year for those having a second pillar plan or up to 20% of income (maximum CHF 35 280) per year for others (mainly self-employed). Contributions in the voluntary plans can be deducted from personal income tax. Earnings (interest and surpluses) are exempt from income tax.

Figure 2.11. Replacement rate across the income distribution

Figure 2.12. Population ageing raises costs related to pensions, health-care and long-term care

Change in fiscal pressure to keep public debt ratio at current level in the baseline scenario, between 2024 and 2060, % pts of potential GDP

1. Shows cost of pensions under the standard assumption by Guillemette and Turner (2021) of a constant benefit ratio, i.e., public pensions will grow in step with wages.

2. Shows cost of pensions under the assumption that public pensions in Switzerland will grow at ½ the pace of wages, in line with the current Swiss law and consistent with the Figure 2.10 above.

Source: OECD Long-Term Model.

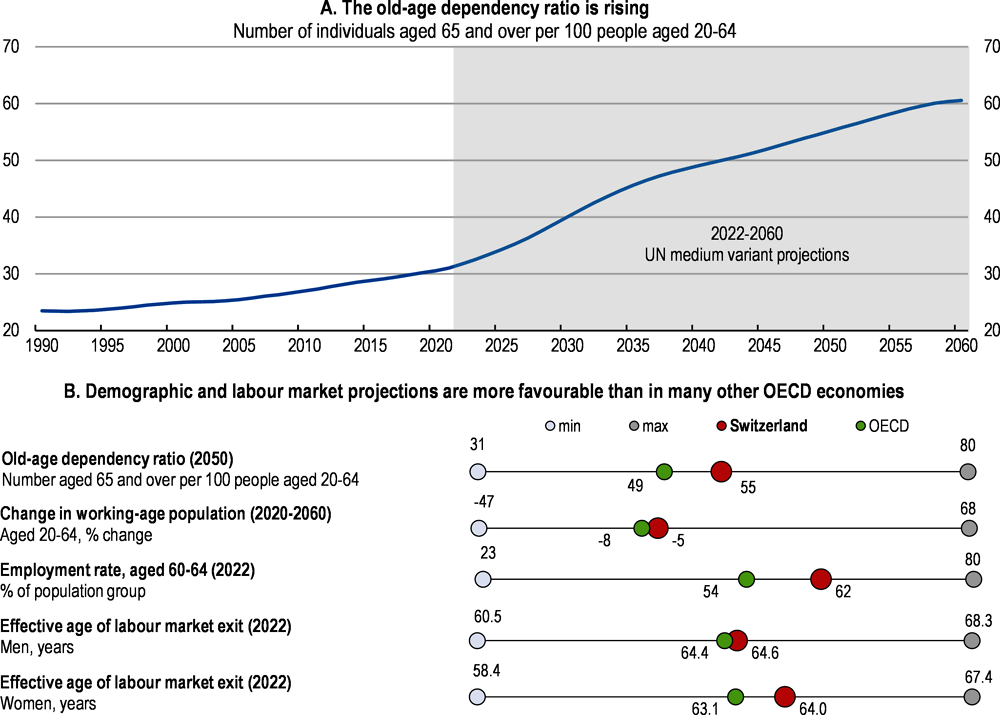

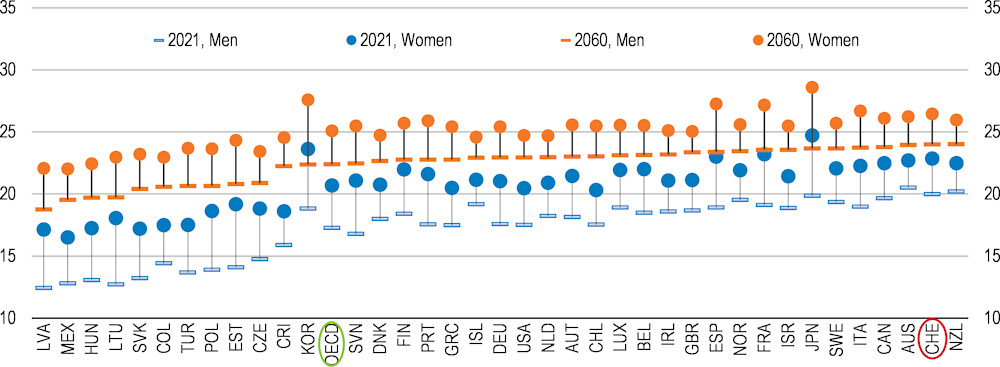

The population is ageing rapidly and the old-age dependency ratio is rising (Figure 2.13). The number of people aged 80 or over will more than double by 2045. Demographic and labour market projections are more favourable for Switzerland than many other OECD economies thanks to high employment rates and a slower projected decline in the working age population (Figure 2.13). However, these are subject to uncertainty and rely on sufficient net immigration of workers (OECD, 2021a). Furthermore, while the effective age of retirement is slightly above the OECD average, high longevity leads to high remaining life expectancy at labour market exit (Figure 2.14). With the statutory age of retirement currently fixed at 65 and life expectancy at 65 projected to increase by four years for both men and women by 2060 (OECD, 2021b), more and more time will be spent in retirement, raising pension expenditures.

Figure 2.13. Population ageing impacts the labour market

Note: The UN medium variant of demographic projections for Switzerland is more pessimistic than national projections by the Federal Statistical Office (FSO). According to the FSO’s reference scenario, the old-age-dependency ratio increases from 31% in 2020 to 50% in 2060 (FDF, 2021).

Source: United Nations (2022), World Population Prospects: The 2022 Revision, Online Edition; OECD Labour Force Statistics; OECD (2023), Pensions at a Glance 2023: OECD and G20 Indicators.

Figure 2.14. Time spent in retirement is long and set to lengthen further

Remaining life expectancy at age 65

Source: United Nations (2022), World Population Prospects: The 2022 Revision, Online Edition.

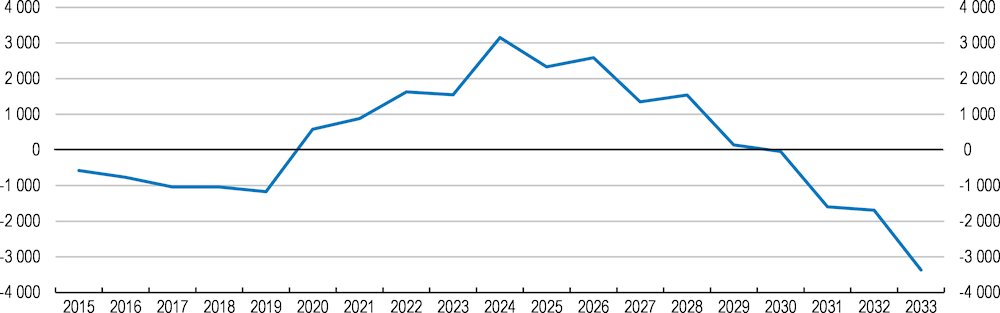

Population ageing and a lack of bold reform threaten the sustainability of the Swiss pension system and the adequacy of benefits. After years of attempting reform and rejections in referenda, two recent reforms (one effective from 2020 and one from 2024) only temporarily ease pressures. The reforms raise social security contributions by 0.3 percentage points, earmark additional revenues to the first pillar from a 0.4 percentage point increase in the standard VAT rate, and raise the federal government’s contribution from 19.6% to 20.2% of total expenses. In addition, the retirement age of women will be gradually equalised with that of men at 65 (by 2027). Yet, the first pillar’s funding still faces serious pressures. The compensation fund managing first pillar assets and liabilities ran rising deficits (excluding investment returns) between 2014 and 2019 (FSIO, 2022 and 2023a) until the recent boost to revenues, but spending pressures are set to continue growing. According to projections by the Federal Social Insurance Office (FSIO, 2023b), the fund (balance excluding investment returns) will return to deficit in 2030 (Figure 2.15). Further measures are therefore needed.

Figure 2.15. Recent reform has only temporarily eased financing pressures on the 1st pillar

Old-age and survivor's insurance, balance excluding investment income, CHF million (2022 prices)

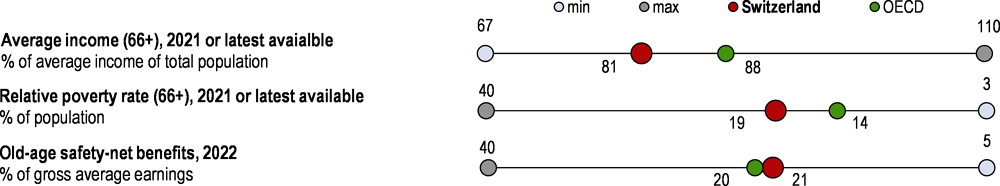

According to the OECD’s Pension Model, future beneficiaries will face low replacement rates from the mandatory pension system (the first pillar and the mandatory part of the second pillar) (Figure 2.16). Mandatory pensions are indexed to the average of wage growth and price inflation. Net income of a person entering the labour market aged 22 in 2022 and working a full career at average earnings will more than halve at the moment of retirement if not supplemented with benefits from the voluntary employer pension schemes (OECD, 2023, 2021a and 2021b). However, fewer than one in ten people belong to a compulsory-only scheme. While the role of mandatory pensions is to provide adequate living standards in old age, Swiss retirees have low incomes compared to the rest of the population (Figure 2.17). The old-age relative income poverty rate is above the OECD average. At the same time, the median net wealth of households with at least one retired person is six times higher than for the active population. Yet, 18% of households with retirees have no or negative net wealth (Wanner, 2023). With falling replacement rates, the income in old age of those who will not save enough in voluntary schemes, will worsen.

Raising the statutory retirement age and linking it to increases in life expectancy, as well as improving incentives to work beyond that age are key reforms that would raise revenues, ease spending pressures and help sustain growth. This would also help increase replacement rates in the mandatory second pillar. Other OECD countries such as Denmark, Italy and the Netherlands for example, have already instituted reforms to lift the statutory retirement age and subsequently link it to life expectancy. In the Netherlands, the retirement age is automatically increased by two-thirds of the increase in life expectancy, roughly keeping constant the ratio of years spent in retirement compared to years in the labour market.

The mandatory part of the second pillar faces pressures from unsustainable minimum conversion rates (the rate at which capital is converted into an annual pension benefit). The framework for the second pillar is set with the aim of achieving target replacement rates of 60 percent together with the first pillar, whereby a minimum return on assets (currently at 1 percent) along with a fixed conversion rate (currently 6.8 percent) are set by law. The conversion rate remained unchanged between 2004 and 2023 despite rising life expectancy and a long period of low investment returns. At 6.8% it was well above an actuarially fair rate, which in 2020 was estimated at 4.5-5% (Helvetia, 2020).

Figure 2.16. Beneficiaries will face low replacement rates from mandatory pension schemes

Future net pension replacement rates, men, %

Note: The values of all pension system parameters reflect the situation in 2022 and onwards. The OECD calculations show the pension benefits of a worker who enters the system that year at age 22 – that worker is thus born in 2000 – and retires after a full career.

Source: OECD (2023), Pensions at a Glance 2023.

Figure 2.17. Older Swiss people have low incomes compared to the rest of the population

Source: OECD Income Distribution Database (IDD); OECD (2023), Pensions at a Glance 2023: OECD and G20 Indicators.

At the end of 2022, the coverage ratio (assets to liabilities) stood on average at 107% for private pension funds, but 16% of funds had coverage ratios below 100% (OPSC, 2023a). Among public pension funds that benefit from government guarantees, 94% had a coverage ratio below 100% (OPSC, 2023b). To meet steep financial obligations amid low returns, over a period of ten years, pension funds lowered returns accruing to current contributors, resulting in significant intergenerational transfers (OPSC, 2023b). Many funds lowered effective conversion rates by lowering conversion rates from the voluntary part of the second pillar. Such measures and the recent rise in interest rates have eased pressures on funds’ finances, but funds that rely mostly on the mandatory scheme still face difficulties in meeting obligations.

In March 2023, Parliament passed a reform to reduce the conversion rate from 6.8% to 6%, together with some measures to cushion the transition and protect low-income workers from the resulting drop in pensions. This can in part ease financial pressures further, but the bill is expected to be subject to referendum. Lowering the minimum conversion rate and making it a more flexible parameter (not set by law as it is now) is crucial to safeguard the sustainability of the second pillar. The earliest age to enter retirement in the second pillar (currently 58 years) could be revised up in line with the first pillar retirement age (63), and subsequently linked to life expectancy. Contributions to the second pillar only begin at age 25, even though the employment rate is already 70% for the 20-24 age group. Lengthening the contribution period – lowering the starting age below 25 (currently set by law) and extending it beyond 65 – would help maintain adequate benefits while improving the sustainability of the pension system.

Box 2.6. Potential impact of reforms

Structural reforms can boost economic growth and incomes. Table 2.3 quantifies the impact on growth of some of the reforms recommended in this Survey (quantification is not feasible for all of them) based on the OECD long-term model and OECD estimates of relationships between reforms and total factor productivity, capital deepening and the employment (Égert, 2017). The estimates are illustrative and to be interpreted with caution.

The analysis suggests that if Switzerland implemented the selected set of reforms proposed in this Economic survey, per capita income could increase by about 3% in 10 years and up to 12% in 25 years. Improving the business environment boosts multifactor productivity as well as labour participation, with the strongest impact on GDP per capita. Other reforms boost labour market participation. Attracting foreign workers has a slightly negative effect on the GDP per capita in the short term as it simultaneously boosts population. However, the impact on the GDP per capita builds up over time due to assumed higher employment rates of migrants.

Table 2.3. Potential impact of structural reforms on GDP per capita

|

10 years |

25 years |

|

|---|---|---|

|

Reform the pension system |

0.6% |

3.1% |

|

Boost female labour participation |

0.4% |

2.0% |

|

Attract foreign workers |

-0.5% |

0.6% |

|

Improve the business environment (less state involvement, lower barriers to trade and investment). |

1.7% |

6.1% |

|

Boost active labour market policies. |

0.9% |

1.6% |

|

Package of reforms |

3.1% |

13.4% |

Note: Simulations based on the OECD Economics Department Long-term Model. A no policy change scenario is used as the baseline. The following changes in policy/outcomes are assumed. The pension reform entails the following: The retirement age gradually rises to 67 in 2034, and by two thirds of the expected gain in life expectancy thereafter. A boost to female labour participation assumes the female prime-age (25-54) employment rate converging with that of men by 2050. Boost to employment of foreign workers assumes net immigration rising from 45 000 annually to 75 000 by 2030 and staying at that level thereafter. The Product Market Regulation (PMR) components where Switzerland underperforms are brought to the OECD average (reduced state ownership in the economy, less regulation in network sectors and lower barriers to trade and investment). Active labour market policies are boosted to reach the average of top five performers in the OECD (as % of GDP per capita per unemployed person).

Source: OECD Long-term Model and OECD calculations.

The estimates in Table 2.4 quantify the direct fiscal impact of selected recommendations included in the Survey, and do not seek to incorporate dynamic effects. The estimates are illustrative.

Table 2.4. Illustrative annual direct fiscal impact of selected recommended reforms in 25 years

|

Reform |

Fiscal impact (savings (+)/ costs (-)) (% of GDP) |

|---|---|

|

Expenditures |

|

|

Reform the pension system (includes dynamic effects) |

+1.5% (by 2049) |

|

Expanding the supply of affordable childcare |

-0.4% |

|

Attract foreign workers |

Negligible |

|

Improve the business environment (less state involvement, lower barriers to trade and investment) |

Negligible |

|

Boost active labour market policies - expanding upskilling courses and improving recognition of foreign qualifications for migrants |

-0.2% |

|

Fiscal cost of investment to reach net zero |

-0.2%-0% |

|

Growth in primary expenditure after pension and labour reform by 2049 (includes dynamic effects) |

-0.9% |

|

Total expenditures |

-0.2%-0% |

|

Revenues |

|

|

Reform of taxes/benefits to boost female employment |

Revenue neutral |

|

Strengthen tax revenues, including by raising revenues from VAT and the recurrent tax on immovable property. |

0%-0.2% |

|

Total fiscal impact of revenue and spending related measures |

0% |

Note: The fiscal dividend of the pension reform is computed by taking a difference between the required increase in government revenues to keep the debt-to-GDP ratio stable in “baseline” and “pension reform” scenarios. See also Figure 2.10. Based on simulations of the OECD Economics Department Long-term Model. Reform of taxes/benefits to boost female employment refers to the introduction of individual-based taxation or adjustments to taxes/ benefits that provide better incentives to work for second earners. The estimated illustrative fiscal cost of investment to reach net zero by 2050 looks at various estimates of such costs (Federal Council, 2021; SBA, 2020, Panos et al., 2023, and WWF CHE, 2022) and applies a 13% share for public investment (an average over 1990-2021). The growth in primary expenditure after pension and labour reform is estimated as the difference between revenues to keep debt stable between 2024 and 2049. The estimated need for additional tax revenues implies an unchanged level of public expenditures as a share of GDP.

Source: OECD calculations.

Table 2.5. Past recommendations on fiscal sustainability

|

Recommendations in previous Surveys |

Action taken |

|---|---|

|

Limit mortgage interest deductibility in personal income tax and broaden the capital gains tax base. |

No action taken. |

|

Consider reforming the design of the net wealth tax to make it more progressive, limit debt deductibility and improve coordination across cantons. |

No action taken. |

Fighting corruption and money laundering

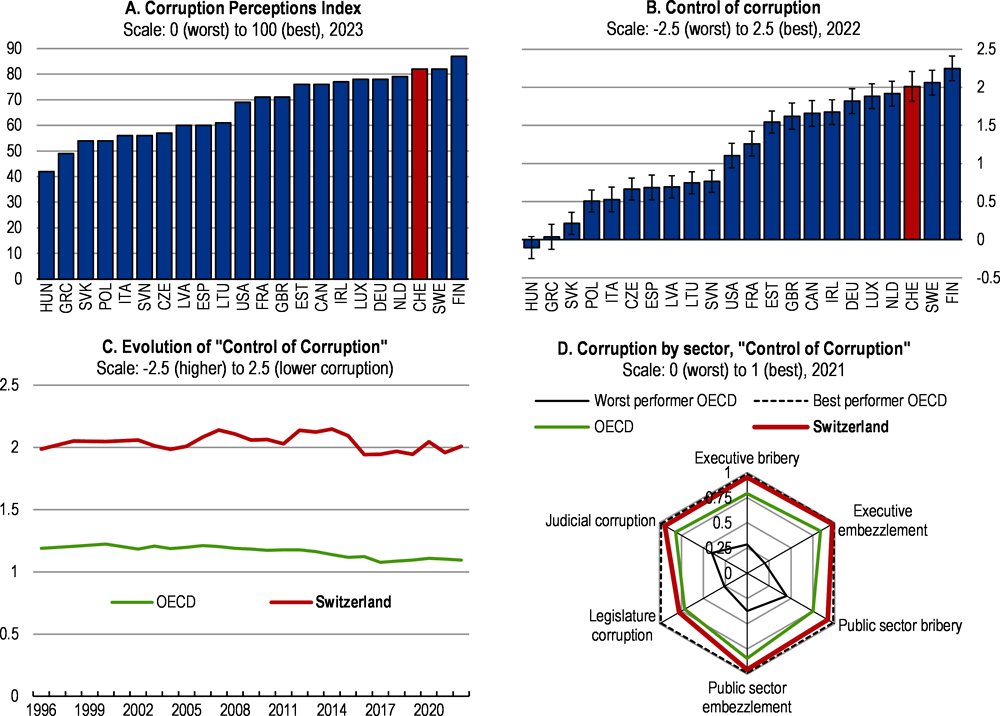

Switzerland consistently scores among the best-performing OECD member countries, next to Finland and Sweden, on control and perceived risks of corruption in the public sector (Figure 2.18). It scores above the OECD average in all sectors for control of corruption and is on par with best performers in judicial corruption, executive bribery, executive embezzlement and public sector embezzlement. In its Corruption Perceptions Index for 2023, Transparency international ranked Switzerland 6th out of 180 countries. Efforts continue to strengthen further Switzerland’s approach to public integrity and corruption prevention across all branches of government through the Anti-Corruption Strategy 2021-24 (Federal Council, 2020), also with the aim to maintain the reputation of Switzerland as the world-renowned business centre with high integrity.

In its fourth evaluation round, the Council of Europe anti-corruption body, the Group of States against Corruption (GRECO) listed twelve recommendations to Switzerland to prevent corruption and improve public integrity in respect of members of parliament, judges and prosecutors (Council of Europe, 2017). Five years later, GRECO (Council of Europe, 2023) concluded that there was limited progress in the overall implementation of the recommendations. Switzerland has still only implemented satisfactorily or dealt in a satisfactory manner with five of the twelve recommendations contained in the Fourth Round Evaluation Report.

With respect to members of parliament, progress since the 2021 compliance report (Council of Europe, 2021) has been limited. It is welcome that the staff of Members of Parliament must now take a mandatory online ethics course and MPs must certify electronically that their declarations of interest are up to date, but further steps are needed to progress in implementing the recommendations. GRECO notes that MPs still do not have a dedicated body to advise on issues relating to integrity and do not receive any training in this area, their declarations of interest still do not contain quantitative data or information on their liabilities, and they are still not monitored by the Parliamentary Services.

Figure 2.18. Switzerland performs well in control of corruption

Note: Panel B shows the point estimate and the margin of error. Panel D shows sector-based subcomponents of the “Control of Corruption” indicator by the Varieties of Democracy Project.

Source: Panel A: Transparency International; Panels B & C: World Bank, Worldwide Governance Indicators; Panel D: Varieties of Democracy Project, V-Dem Dataset v12.

With respect to judges, GRECO finds the additional measures taken to implement the recommendations more encouraging. The Federal Assembly’s Judicial Committee is currently working on a regulation that would contribute to making the pre-selection of judges more transparent and a draft legal basis is being prepared to create an advisory committee specialising in pre-selection to make the process more objective. The Federal Patent Court has adopted and published a code of conduct, while the Federal Administrative Court has set up a working group to develop a draft code of conduct to supplement the existing ethical charter with concrete examples and/or explanatory comments. However, federal judges still pay part of their salary to political parties that supported their election, against GRECO’s recommendations. Also, no measures have been taken to introduce formal sanctions for less serious violations – that do not merit removal from office – for judges who commit a breach of their official duties.

A prominent international position, high export orientation and focus on global finance expose Switzerland to a relatively high risk of foreign bribery and money laundering. Switzerland has one of the world’s highest ratios of multinationals to inhabitants and many operate in sectors that are highly prone to foreign bribery including pharmaceuticals and trade in raw materials such as agricultural products, stone and metals, and energy products. Moreover, the international status of Switzerland’s financial sector and focus on wealth management make the sector prone to greater risk of use for criminal purposes, particularly through money laundering, including the laundering of foreign bribery (OECD, 2018).

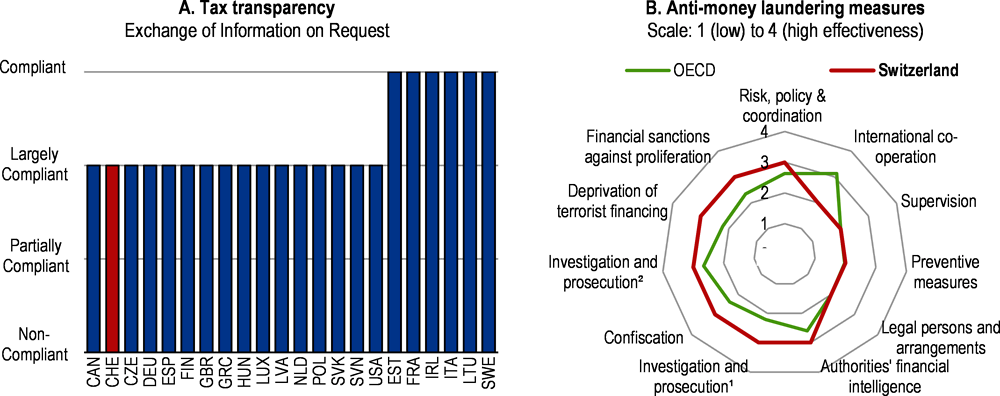

FINMA’s Risk Monitor (FINMA, 2022 and 2023b) identifies money laundering as one of the principal risks to the Swiss financial sector and linked it to a growing number of customers of the Swiss asset management industry that come from emerging markets. Financial flows associated with corruption and embezzlement can involve not just affluent private clients but also state or quasi-state organisations and sovereign wealth funds. Complex and opaque structures reduce transparency and raise risks further. Moreover, risks in the crypto area are becoming increasingly apparent, whereby the threats of money laundering and the financing of terrorism are heightened due to the potential for greater anonymity along with the speed and cross-border nature of transactions. The Financial Action Task Force (FATF), an independent inter-governmental body that promotes policies to protect the global financial system against money laundering, terrorist financing and the financing of proliferation of weapons of mass destruction, produces regular evaluations of its member countries policies and practices. In its October 2023 report on Switzerland, FATF recognised Switzerland’s progress in addressing most of the technical compliance shortcomings identified in its Mutual Evaluation Report (MER) from 2016 on anti-money laundering and counter-terrorist financing. FATF changed Switzerland’s rating from partially compliant to largely compliant on these issues.

Indicators also show that Switzerland’s anti-money laundering measures are quite effective in most aspects (Figure 2.19). According to the OECD Working Group on Bribery in International Business Transactions (OECD WG), Switzerland, through the continued action of the Office of the Attorney General, continues to play an important and active role in enforcing foreign bribery (OECD, 2018 and 2020, 2022b). Based on the number and significance of commenced and concluded investigations, Transparency International (2022) categorised Switzerland and the United States as countries with active foreign bribery enforcement (as opposed to moderate, limited or no enforcement).

Figure 2.19. Anti-money laundering measures are effective in most aspects

Note: Panel A summarises the overall assessment on the exchange of information in practice from peer reviews by the Global Forum on Transparency and Exchange of Information for Tax Purposes. Peer reviews assess member jurisdictions' ability to ensure the transparency of their legal entities and arrangements and to co-operate with other tax administrations in accordance with the internationally agreed standard. The figure shows results from the ongoing second round when available, otherwise first round results are displayed. Panel B shows ratings from the FATF peer reviews of each member to assess levels of implementation of the FATF Recommendations. The ratings reflect the extent to which a country's measures are effective against 11 immediate outcomes. "Investigation and prosecution¹" refers to money laundering. "Investigation and prosecution²" refers to terrorist financing.

Source: OECD Secretariat’s own calculation based on the materials from the Global Forum on Transparency and Exchange of Information for Tax Purposes; and OECD, Financial Action Task Force (FATF).

However, the OECD WG, in its recent assessments (OECD 2020 and 2022b), noted the absence of legislative reforms in two key areas where Switzerland received explicit recommendations: (i) appropriate regulatory framework to compensate and protect private sector employees (whistleblowers) who report suspicions of foreign bribery from any discriminatory or disciplinary action; ii) the increase in the maximum level of fines against companies convicted of foreign bribery to make them effective, proportionate and dissuasive (this amount is currently set at CHF 5 million, which is very low compared to the amounts at stake in foreign bribery).

Table 2.6. Recommendations

|

MAIN FINDINGS |

RECOMMENDATIONS |

|

Ensuring price and financial stability |

|

|

Inflation has retreated within the target 0-2% range. However, short-term inflation expectations remain at the top of the target band. Expected rent and electricity price increases will temporarily push inflation above 2% in 2024. |

Keep a tight monetary policy stance until inflation is durably within the 0-2% band. |

|

The large size of the SNB balance sheet raises risks and challenges, as changes in valuation can bring about large losses (or profits). |

The SNB should continue reviewing its investment strategy and maintain adequate safeguards to dampen risks arising from its large balance sheet. |

|

The acquisition of Credit Suisse by UBS effectively safeguarded financial stability, but it raises new risks and challenges. UBS – already a global systemically important bank before the merger – has become even larger and according to the “too big to fail” (TBTF) regulations, it must meet even stricter regulatory requirements. |

Continue close supervision and monitoring of the merged bank during the integration and restructuring process. |

|

Credit Suisse was a global systemically important bank that met regulatory requirement, yet it destabilised quickly. Although the existing “too big to fail” framework was available, the solution was found outside the resolution regime. |

Conduct an in-depth review of the Credit Suisse crisis event and propose measures to strengthen regulation and supervision of systemically important banks and the “too big to fail” framework. |

|

Vulnerabilities on the residential real estate market persist. Large interest rate hikes or other shocks could result in steep price corrections, leading to deteriorated mortgage portfolios of banks. |

Continue to closely monitor risks on the housing market and ensure that adequate buffers are maintained. Consider a broader toolkit of macroprudential measures that would take account of affordability (e.g., debt-to-income and debt-service-to-income limits on mortgage loans). Give the authorities clear and strong mandates to propose and calibrate macroprudential tools. |

|

Addressing pressures from rising public spending |

|

|

Real GDP growth is projected to remain below potential in 2023 and gather pace in 2024. The unemployment rate will pick up slightly. |

Pursue a broadly neutral fiscal stance over the short term with automatic stabilisers operating freely. |

|

Fiscal policy is facing hard choices to meet growing spending needs. Systematic spending reviews can help find fiscal savings. Strengthening tax revenues can also help to safeguard fiscal sustainability. Switzerland relies significantly more on direct taxation while revenues from VAT and from the recurrent tax on immovable property are low. |

Conduct systematic reviews of spending and tax expenditures and strengthen tax revenues, including by raising revenues from VAT and the recurrent tax on immovable property. |

|

Population is ageing rapidly. With the statutory retirement age at 65, time in retirement will rise steeply. Rising pension expenditures are putting pressures on fiscal sustainability and the adequacy of pension benefits. |

Link future rises in the statutory retirement age to increases in life expectancy. |

|

The conversion rate (at 6.8%) in the second pillar is set by law and has been unchanged since 2004 despite rising life expectancy and a long period of low investment returns. To meet financial obligations, pension funds had to reduce returns to current contributors, resulting in substantial redistribution within the second pillar from younger to older workers and retirees. Pension funds face financial pressures and many have coverage ratios below 100%. |

Lower (as planned) the parameter used to calculate annuities (“minimum conversion rate”) and make it a more flexible technical parameter set by ordinance. Subsequently link it to life expectancy. Raise the earliest age to enter retirement in the second pillar (currently at 58 years) in line with the first pillar retirement age (63). Lengthen the contribution period – lowering the starting age below 25 (currently set by law) and extend it beyond 65. |

|

Fighting corruption and money laundering |

|

|

The prominent international position, high export orientation and focus on global finance expose Switzerland to a relatively high risk of foreign bribery and money laundering. A large number of multinationals operate in sectors highly prone to foreign bribery including pharmaceuticals and trade in raw materials. In the private sector, whistleblowers continue to expose themselves to criminal proceedings after reporting cases involving corruption and foreign bribery. |

Strengthen protection for whistleblowers in the private sector. Increase the statutory maximum fine for companies in foreign bribery cases to ensure that sanctions are effective, proportionate and dissuasive. |

References

Castle, C., Hemmerlé, Y., Sarcina, G., Sunel, E., d’Arcangelo, F. M., Kruse, T., Haugh, D., Pina, A., Pisu, M. (2023), Aiming better: Government support for households and firms during the energy crisis, OECD Economic Policy Papers 32.

Council of Europe (2023), Group of States against Corruption (GRECO) Fourth Evaluation Round: Corruption prevention in respect of Members of Parliament, Judges and Prosecutors. Addendum to the Second Compliance Report: Switzerland. GrecoRC4 (2022)23.

Council of Europe (2021), Group of States against Corruption (GRECO) Fourth Evaluation Round: Corruption prevention in respect of Members of Parliament, Judges and Prosecutors. Second Compliance Report: Switzerland. GrecoRC4 (2021)7.

Council of Europe (2017), Group of States against Corruption (GRECO) Fourth Evaluation Round: Corruption prevention in respect of Members of Parliament, Judges and Prosecutors. Evaluation Report: Switzerland.

Federal Council (2023a), First extrapolation for 2023: smaller financing deficit expected, Press Release, 16.8.2023.

Federal Council (2023b), Le Conseil fédéral fixe les grandes lignes du plan financier pour la prochaine legislature, Press Release, 22.11.2023.

Federal Council (2021), Switzerland’s Long-Term Climate strategy.

Federal Council (2020), The Federal Council's Anti-Corruption Strategy 2021-24.

FDF (2021), 2021 report on the long-term sustainability of public finances in Switzerland, Federal Department of Finance, Bern.

FINMA (2023a), Lessons Learned from the CS Crisis. FINMA Report. Bern, 19 December 2023. The Swiss Financial Market Supervisory Authority (FINMA).

FINMA (2023b), FINMA Risk Monitor 2023. The Swiss Financial Market Supervisory Authority (FINMA).

FINMA (2022), FINMA Risk Monitor 2022. The Swiss Financial Market Supervisory Authority (FINMA).

FONES (2021), Report on Risks to National Economic Supply.

FSIO (2023a), Assurances sociales 2021, Rapport annuel selon l’article 76 LPGA, Federal Social Insurance Office, Bern.

FSIO (2023b), Perspectives financières de l’AVS, Federal Social Insurance Office, Bern.

FSIO (2022), Statistiques des Assurances Sociales Suisses 2022, Federal Social Insurance Office, Bern.

Guillemette, Y. and D. Turner (2021), The Long Game: Fiscal Outlooks to 2060 Underline Need for Structural Reform, OECD Economics Department Policy Papers, No. 29.

Helvetia (2020), Le Taux de Conversion [The Conversion Rate], Helvetia Prévoyance professionnelle.

IEA (2020), Country profile - Switzerland, https://www.iea.org/countries/switzerland (accessed on 30 October 2023).

IMF (2019), Switzerland - Financial Sector Assessment Program, IMF Country Report No. 19/183.

OECD (2023), Pensions at a Glance 2023: OECD and G20 Indicators, OECD Publishing, Paris.

OECD (2022a), OECD Economic Surveys: Switzerland 2022, OECD Publishing, Paris.

OECD (2022b), Switzerland should urgently take concrete steps to adopt key legislative reforms. The OECD Working Group on Bribery New Release, 20 July 2022.

OECD (2021a), Pensions at a Glance 2021: OECD and G20 Indicators, OECD Publishing, Paris.

OECD (2021b), Pensions at a Glance 2021. How does Switzerland compare?, OECD Publishing, Paris.

OECD (2020), Implementing the OECD Anti-Bribery Convention: Phase 4 Two-Year Follow-up Report Switzerland.

OECD (2019), OECD Economic Surveys: Switzerland 2019, OECD Publishing, Paris.

OECD (2018), Implementing the OECD Anti-Bribery Convention. Phase 4 Report: Switzerland.

OECD (2017), OECD Economic Surveys: Switzerland 2017, OECD Publishing, Paris.

OPSC (2023a), Conférence de presse annuelle. Berne, le 9 mai 2023, Dossier de presse, Occupational Pension Supervisory Commission.

OPSC (2023b), Rapport sur la situation financière des institutions de prévoyance en 2022, Occupational Pension Supervisory Commission.

Panos, E., Kannan, R., Hirschberg, S. and Kober, T., (2023), An assessment of energy system transformation pathways to achieve net-zero carbon dioxide emissions in Switzerland. Communications Earth & Environment, 4(1), p.157.

SBA (2020), Sustainable finance - Investment and financing needed for Switzerland to reach net zero by 2050, Swiss Banking Association.

SNB (2022), Accountability report. Swiss National Bank.

SNB (2023a), Quarterly Bulletin 2/2023 June. Swiss National Bank.

SNB (2023b), Quarterly Bulletin 3/2023 September. Swiss National Bank.

SNB (2023c), 115th Annual Report. Swiss National Bank 2022.

SNB (2023d), Financial Stability Report 2023. Swiss National Bank.

Transparency International (2023), Corruption Perception Index 2022.

Transparency International (2022), Exporting corruption 2022. Assessing enforcement of the OECD Anti-Bribery Convention.

Tryggvadottir, Á. (2022), “OECD Best Practices for Spending Reviews”, OECD Journal on Budgeting, Vol. 22/1.

Wanner, P. (2023), En Suisse, les retraités sont plus riches que les actifs, La Vie économique. 21.02.2023.

WWF (2022), Climate transition finance needs and challenges: insights from Switzerland.

Zeng, L., and Li, G. (2023), Underlying and beyond the numbers – assessing SNB balance sheet changes in 2022. Switzerland – Selected issues. IMF Country Report No. 23/197. June 2023.