Erik Frohm

OECD Economic Surveys: Switzerland 2024

5. Strengthening economic resilience within global value chains

Abstract

Switzerland has shown remarkable strength during past economic downturns. A comprehensive risk planning and monitoring system, as well as essential-goods stockpiles has effectively bridged temporary supply disruptions. Yet, rising geopolitical tensions and a global shift towards protectionism pose significant challenges for the Swiss economy. To raise its resilience and productivity, Switzerland should refrain from relying on distortive industrial policies or trade restrictions, and rather continue to commit to international trade and cooperation, strengthen ties with key trading partners and enhance domestic competition. Resuming negotiations with the EU is key to safeguard access to the single market and deepen the economic partnership. Reducing trade barriers and lowering the administrative burden could reduce trade costs, which would allow companies to diversify supply chains while raising productivity.

Adapting to a changing global economic landscape

Escalating geopolitical tensions and recent crises, such as the COVID-19 pandemic and Russia's war of aggression against Ukraine, have put economic resilience (namely, society’s ability to function and recover from crises without lasting damages, as well as a country’s capacity to adapt to structural changes) at the top of the policy agenda. As a country that relies heavily on global markets to sustain its high living standards, Switzerland can be particularly affected by changes in the global economic landscape or disruptions in complex global value chains (GVCs). Adverse shocks can rapidly propagate through trade and financial linkages, underscoring the imperative to detect and address risks and dependencies. Systemically building economic resilience can dampen the adverse effects of crises on the domestic economy, help protect vulnerable households, ensure a rapid economic recovery and raise long-term growth (OECD, 2021a).

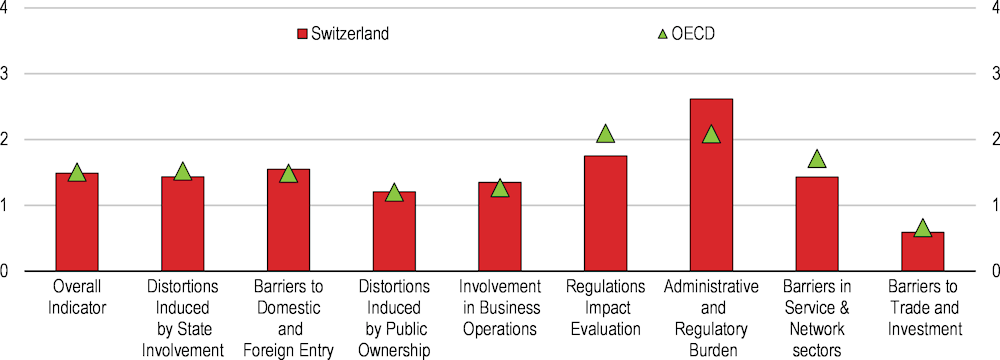

Waning global support for economic openness poses sizable risks. While key indicators of global openness remain at elevated levels (Goldberg and Reed, 2023; Franco-Bedoya, 2023; Di Sano, Gunnella and Lebastard, 2023), eroding trust in the international community has given rise to protectionist sentiments that are starting to be reflected in global trade (WTO, 2023). Global uncertainty surged over the 2010s and in the 2020s, fuelled by specific events like Brexit, the US-China dispute in 2018, the COVID-19 pandemic and most recently Russia’s war against Ukraine. The share of global imports covered by trade-restrictive measures have also risen significantly since the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) from covering less than 1% of imports in 2009 to over 9% in 2022 (Figure 5.1, panel A). Protectionist pressures increased through the COVID-19 crisis and led to severe bottlenecks in supply chains (Figure 5.1, panel B), initially affecting medical and protective equipment and subsequently impacting other intermediate inputs as economies worldwide reopened (Frohm et al., 2021; Attinasi et al., 2021). Furthermore, Russia’s war against Ukraine has severely limited the availability of natural gas in Europe, thus raising concerns about the future energy supply and raising awareness of potential vulnerabilities and risks in other energy and commodity markets. As a result, companies see geopolitical tensions and deglobalisation as key risks in the medium term (Oxford Economics, 2023)

Eroded trust in the international community, successive crises that uncovered potentially excessive dependencies and concerns for national security, have intensified calls for reshoring of production and active industrial policies, particularly among the world’s largest economic blocks. Direct policy support has been stepped up for the transition towards achieving net zero greenhouse gas emissions in the United States through the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) and in the EU through the Green Deal Industrial Plan. Other recent examples include attempts to develop a domestic semiconductor industry in the United States (The White House, 2022) and the European Union (European Commission, 2023a) while China has adopted a so-called dual circulation strategy to become self-sufficient (Herrero-García, 2021). Overall, the number of subsidies that distort trade and competition have risen throughout the 2010s (Global Trade Alert, 2023).

Switzerland needs to adapt to the evolving global economic landscape and the actions of its trading partners. This entails a comprehensive review of its international position and framework conditions, the identification of trade dependencies, policies to bridge temporary disruptions and a heightened focus on enhancing economic integration with strategic trading partners and lowering trade costs.

While the source of disruptions might vary (financial, pandemic or war), their economic consequences are often transmitted via international linkages. The stability and resilience of supply chains are thus key in shaping the societal consequences of economic disruptions. Yet, investing in resilience comes with costs as well as benefits, and decision makers must carefully weigh the trade-offs. The next section analyses Switzerland’s openness towards the rest of the world, as well as the economy’s performance during the last two global crises. The following section reviews the country’s policies to address supply chain disruptions in the shorter term and discusses effective ways of anticipating vulnerabilities and tools to bridge supply shortages. The last section analyses policies that foster the resilience of GVCs in the longer term and boost productivity.

Figure 5.1. Protectionism and supply disruptions have been rising

Notes: for panel A, the chart denotes the cumulative trade coverage of restrictions on goods estimated by the WTO Secretariat, based on information available in the TMDB on import measures recorded since 2009 and considered to have a trade-restrictive effect. The estimates include import measures for which HS codes were available. The figures do not include trade remedy measures. The import values were sourced by the UN Comtrade database.

Sources: Federal Reserve Bank of New York, Global Supply Chain Pressure Index, https://www.newyorkfed.org/research/gscpi.html; WTO November 2022 Report.

Switzerland’s high living standards are underpinned by a highly open economy

Switzerland records some of the highest per capita incomes in the OECD, reinforced by a dynamic market-based economy, highly skilled workforce and prudent macroeconomic policies. Much of this success is driven by its position in global markets. Vast amounts of goods, services, labour, capital and knowledge cross Swiss borders, resulting in very high levels of productivity. As protectionism rises, a high degree of openness may expose Switzerland to disruptions in complex GVCs that can reinforce logistical, economic and policy risks (Crowe and Rawdanowicz, 2023). A sector-specific shock in one part of the world can potentially propagate quickly through supplier networks and disrupt economic activity (Acemoglu et al., 2012; Acemoglu, 2016; Frohm and Gunnella, 2021).

Openness to trade, capital and migration is high

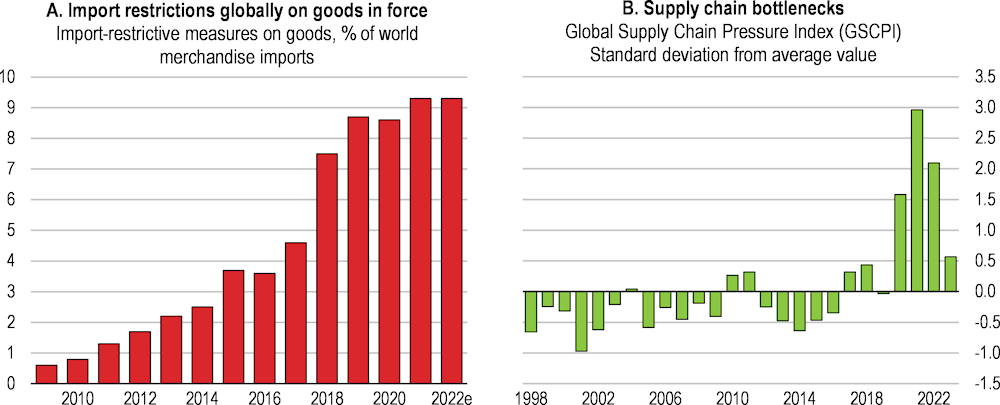

Switzerland is markedly more open to trade than the OECD Europe median. Alongside the rest of the world, Switzerland has experienced a significant increase in the trade of goods and services in earlier decades. Swiss exports and imports rose from 76% of GDP in 1995 to 134% in 2013, and stood at 138% in 2022 (Figure 5.2, panel A). Global trade growth was fuelled by advancements in transport and communication technologies, alongside considerable trade liberalisation efforts (Gunnella et al., 2021; Franco‐Bedoya and Frohm, 2022). Trade slowed in the early 2010s, due to sluggish global investment growth, rebalancing of growth in emerging market economies and a partial unwinding of GVCs (Haugh et al., 2016). It is too early to tell whether the trade growth since the pandemic represents a return to earlier trends, or simply reflects the post-pandemic surge in global demand. With a high trade share, Switzerland relies heavily on foreign demand and imports to sustain its economy (Figure 5.2, panel B). The largest linkages are with neighbouring countries in Europe, Germany, France and Italy but also the United States and China (Figure 5.2, panel C).

Figure 5.2. Switzerland is highly open to global markets

Notes: OECD is a simple average across OECD countries and EU is a simple average across OECD EU member countries. Backward participation is measured by foreign value-added share of gross exports. Forward participation is measured by domestic value-added share of foreign final demand.

Sources: OECD National Accounts database; OECD TiVA database – 2021 edition.

Foreign direct investment (FDI) plays a substantial role in the Swiss economy, with inward and outward FDI stocks representing 125% and 175% of Swiss GDP, respectively. Intellectual property protection, a favourable tax environment, and a highly skilled workforce have attracted multinational companies, leading to the establishment of regional or global headquarters in the country. This has stimulated GVC participation (Figure 5.2, panel D). Swiss companies have also invested in production, distribution and research facilities abroad (SECO, 2023a). In the manufacturing sector, the chemicals and pharmaceuticals industries contribute 50% to total goods exports and account for 10% of GDP, whereas other manufacturing sectors, including machinery, watches and precision instruments account for an additional 11% of GDP. In services, financial services and insurance account for 25% of services exports and 10% of GDP, among the highest in the OECD.

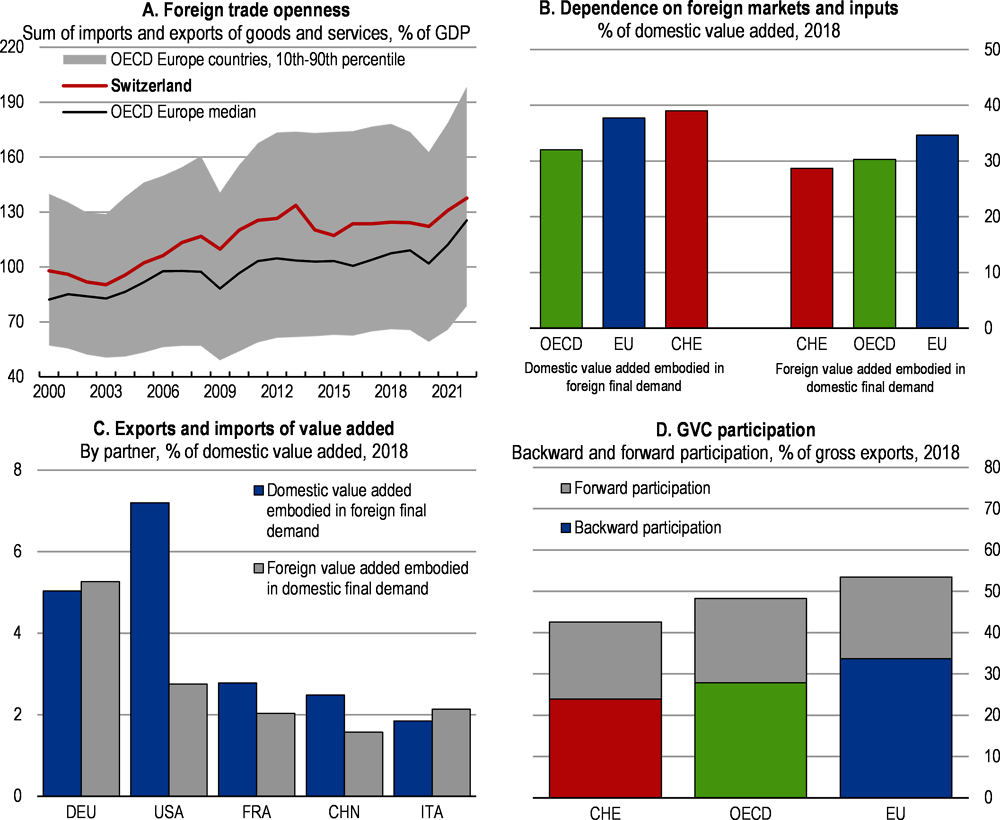

The openness of the Swiss economy extends beyond goods, services and FDI flows. Approximately one in three persons in Switzerland aged 15 or over are foreign born, one of the highest proportions in the OECD (Figure 5.3, panel A). Although immigrants are more likely than the native-born to have only completed mandatory education, foreign-born people that arrived in Switzerland after the age of 15 are also more likely to hold a tertiary degree than natives (OECD, 2023a). High skills are particularly needed in Switzerland, where only a low share of work is in low-skilled occupations (OECD, 2022a). As such, Switzerland boasts one of the highest shares of foreigners that work in professional jobs (largely STEM-fields) in the OECD (OECD, 2023b). Nearly one-third of the employees in the information and communication technology (ICT) sector are foreign workers (SECO, 2022a) and about 40% of researchers are born in another country. The high share of immigrants has been instrumental in addressing labour and skills shortages, including in the healthcare sector, facilitated by the agreement on free movement of persons between the EU and Switzerland.

Close to a quarter of global cross-border assets are managed in Switzerland, making it one of the world’s leading international financial centres. As such, external assets and liabilities reach more than 1400% of GDP (Figure 5.3, panel B), markedly higher than most OECD countries. The country is a leader in transaction financing, a key international location for insurance and reinsurance companies and hosts some of the world’s largest commodity trading companies. The large financial sector exposes Switzerland to global financial risks, as was highlighted in March 2023 when the authorities facilitated a take-over of Credit Suisse by UBS (see the first chapter).

Figure 5.3. The movement of people and capital is very high

Sources: Milesi-Ferretti, Gian Maria, 2022, “The External Wealth of Nations Database,” The Brookings Institution (based on Lane, Philip R. and Gian Maria Milesi-Ferretti, 2018, “The External Wealth of Nations Revisited: International Financial Integration in the Aftermath of the Global Financial Crisis,” IMF Economic Review 66, 189-222.); OECD International Migration Database.

Switzerland has weathered recent global shocks relatively well

Switzerland has exhibited resilience during past economic crises, despite its high dependence on foreign trade, GVCs and integration in the global financial sector. Following Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine, Swiss manufacturing activity receded amid weaker global trade. Energy prices affecting households rose by 23% and 94% for companies in 2022, the largest annual increase in recorded history, pushing inflation above the Swiss National Bank’s (SNB) target band in February 2022. While Switzerland experienced higher inflation, price pressures were significantly less than in other OECD countries, and inflation returned to below 2% in the summer of 2023 (see the first chapter).

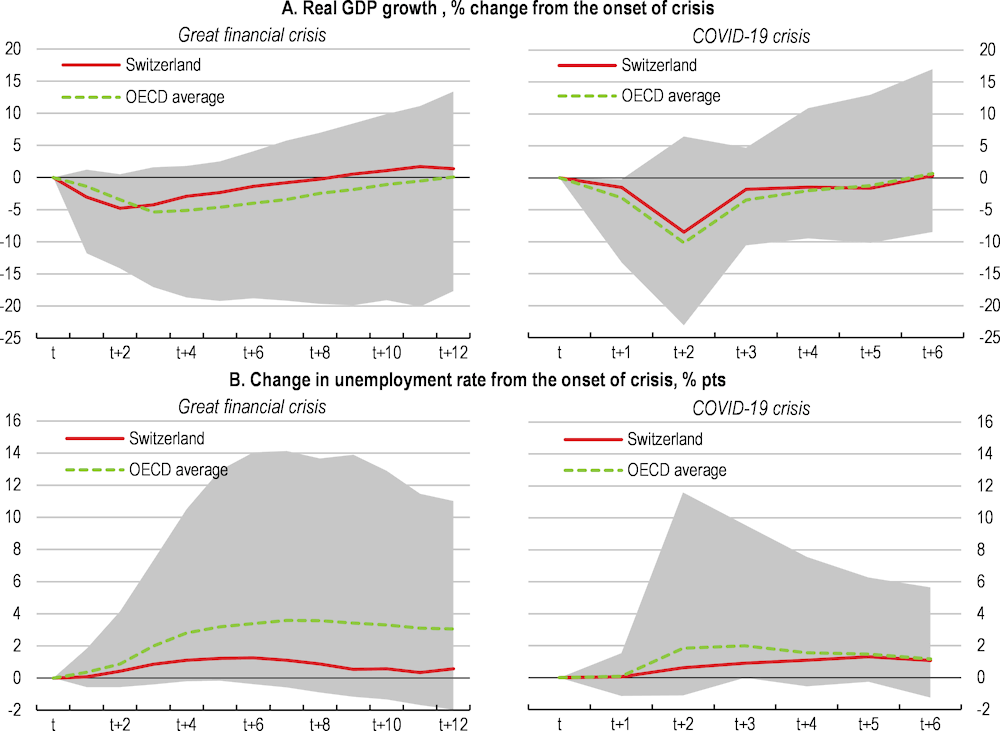

In past crises (the 2008/2009 Global Financial Crisis (GFC) and the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic), Switzerland fared better in terms of GDP and unemployment than most other OECD economies. Labour market developments followed a similar trajectory, with Switzerland experiencing lower increases in unemployment than the OECD average during the GFC (Figure 5.4).

Figure 5.4. Switzerland has managed to perform relatively well during the past two crises

Note: Gray areas represent the range of performance across OECD countries. OECD average is an unweighted average of OECD countries.

Source: OECD calculations based on OECD Economic Outlook database.

However, resilience to shocks at the aggregate level can obscure disparities across regions, sectors, and individuals. Unemployment rose more in the south-western part of the country, and more for lower skilled individuals during the GFC. The COVID-19 pandemic widened economic and health inequalities, disproportionately affecting low-income households (KOF Swiss Economic Institute, 2021). Additionally, foreign-born workers faced a more pronounced increase in their already higher unemployment rate compared to Swiss-born workers. Hijzen and Salvatori (2022) emphasised that women experienced more frequent reductions in working hours compared to men. They also noted a greater utilisation of short-term work schemes among low- to middle-skilled workers and a higher likelihood of job loss for low-skilled workers and those on temporary contracts. These findings indicate that the crisis had a particularly severe impact at the lower end of the wage distribution, underlining the need for temporary and targeted support measures for the most vulnerable people. The Swiss government has implemented numerous extraordinary measures to support vulnerable people, including broader access to short-time work compensation, extended unemployment benefits and the establishment of a special coronavirus income replacement scheme (Felder et al., 2023).

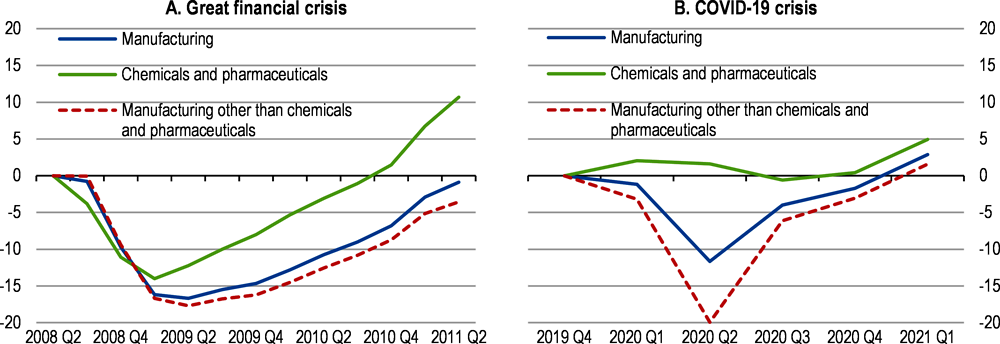

The GFC and the COVID-19 pandemic were very different in nature and had different impacts on the economy. The GFC primarily impacted aggregate demand, with bank failures and global financial sector disruptions severely weakening the real economy. In contrast, the pandemic caused international travel restrictions, global lockdowns, and a suspension of economic activity to contain the virus's spread. As such, the two crises hit some specific sectors very strongly (the financial sector during the GFC and the hospitality sectors during COVID-19), as well as the cyclically sensitive manufacturing sector. Some of Switzerland’s more favourable performance during large downturns in foreign demand is due to its specialisation in advanced manufacturing that is less sensitive to changes in the global economic landscape. For example, the pharmaceutical industry’s performance has helped dampen the impact of shocks to foreign demand on Swiss manufacturing (OECD, 2009). This was the case both during the Great Recession and the COVID-19 pandemic (Figure 5.5).

Figure 5.5. Pharmaceuticals manufacturing in Switzerland is less sensitive to cyclical conditions

Real value added, % change from the onset of the crisis

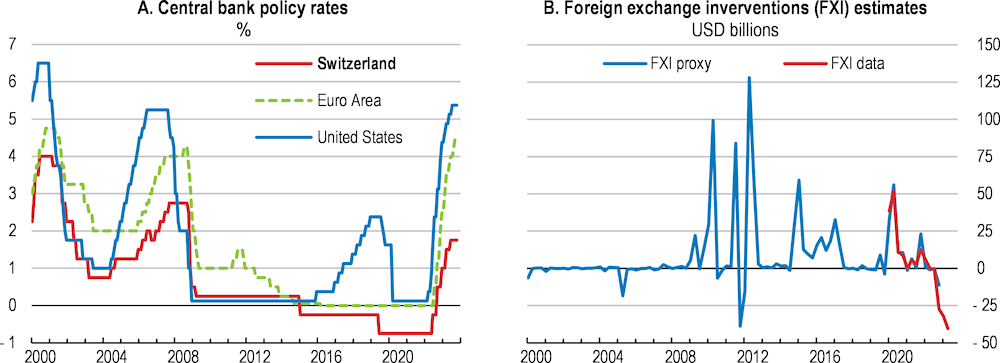

The SNB, the Federal government and the cantons have successfully deployed macroeconomic stabilisation tools to counteract the adverse effects of past crises. The SNB has responded swiftly to changing economic conditions through its policy rate (Figure 5.6, panel A). As a “safe haven” in times of global instability, Switzerland often experiences substantial inflows of foreign currency, leading to upward pressure on the value of the Swiss franc. Consequently, the SNB has resorted to foreign exchange interventions to prevent undue monetary tightening during a time of crisis. Estimates (Adler et al., 2021) suggest that interventions were large in the period after the GFC, which helped prevent further Swiss franc appreciation (Figure 5.6, panel B). Similarly, the SNB sold Swiss francs at the onset of the COVID-19 crisis and reverted to selling foreign currencies in 2022 to ensure that the value of the Swiss Franc did not exacerbate existing inflationary pressures.

Figure 5.6. Monetary policy has adjusted quickly and flexibly to sharp downturns

Sources: OECD Economic Outlook database; Adler, Gustavo, Kyun Suk Chang, Rui C. Mano, and Yuting Shao. 2021. “Foreign Exchange Intervention: A Dataset of Public Data and Proxies,” IMF Working Paper Series 21/47, International Monetary Fund, Washington D.C.

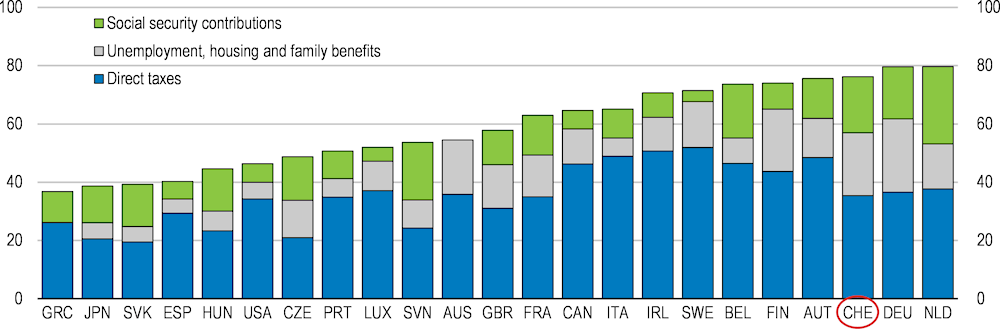

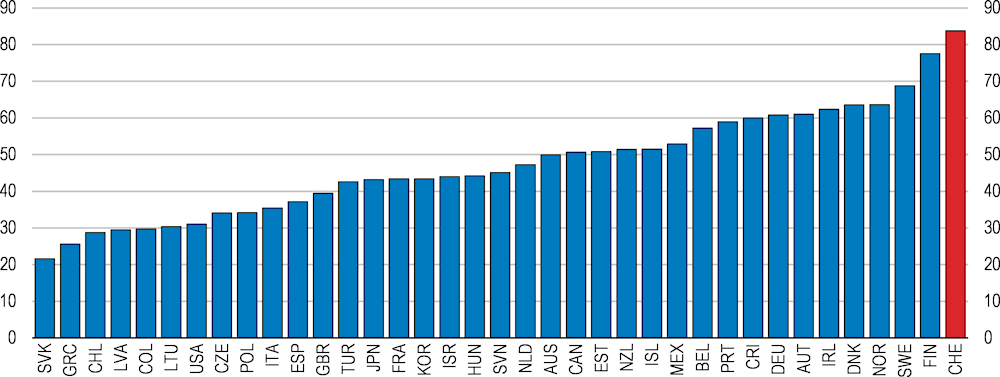

Switzerland has strong automatic fiscal stabilisers and a Short-Time Work Compensation (STWC) scheme that has been instrumental in dampening the adverse consequences of economic downturns on employment (see Box 5.1). Approximately 70-80% of Swiss household disposable income is effectively buffered by automatic changes in government spending and revenues when market income falls Figure 5.7), among the highest level in the OECD (Maravalle and Rawdanowicz, 2020b). The automatic stabilisers consist mainly of direct government taxes (on income, profits and wealth), accounting for roughly 70% of total tax revenues, that adjust in response to economic fluctuations without the need for discretionary policy decisions, as well as an increase in various social benefits. Switzerland’s unemployment benefits maintain more than 80% of the net market income when people become unemployed, among the highest in the OECD (Maravalle and Rawdanowicz, 2020a).

Strong automatic stabilisers are advantageous as they are temporary and do not impact the structural fiscal balance, thereby reducing the risk of pro-cyclical fiscal measures. However, automatic stabilisers might not be enough to mitigate the adverse effects of a very severe economic downturn (Maravalle and Rawdanowicz, 2020a). Switzerland’s ability to deploy substantial discretionary support measures during economic crises has been bolstered by its substantial fiscal buffers and low debt levels. For example, the Swiss authorities extended several discretionary support measures during the COVID-19 pandemic, including federal government credit guarantees for SMEs, loans, guarantees or grants to companies that were closed more than 40 days due to mandates – or that saw their sales drop by 40% or more. Additional sector-specific support to industries particularly affected by COVID-19 was also provided. Many cantons extended additional support to companies in the hardest hit sectors (OECD, 2022a). These policies played a crucial role in restoring confidence and avoiding lasting adverse effects on jobs and incomes from the crisis. Yet, discretionary policies come with risks and may delay the necessary adjustment among households and companies. Such support should be provided only in severe circumstances and be temporary and targeted to those most in need. In this context, the Federal Council decided against extending extraordinary support to households and companies during the energy crisis triggered by Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine (see Box 2.2 in the first chapter).

The government’s capacity to deploy extraordinary measures as crises arose has been guaranteed by responsible fiscal policies in normal times and modest debt levels that allow for increased spending. In this context, the Swiss fiscal framework ensures adequate fiscal buffers are built and is flexible to deal with extraordinary circumstances (OECD, 2022a; Brändle and Elsener, 2023). The framework should be safeguarded to guarantee space to handle future crises.

Figure 5.7. Automatic stabilisation of shocks to household disposable income

Share of an income shock offset by automatic stabilisers

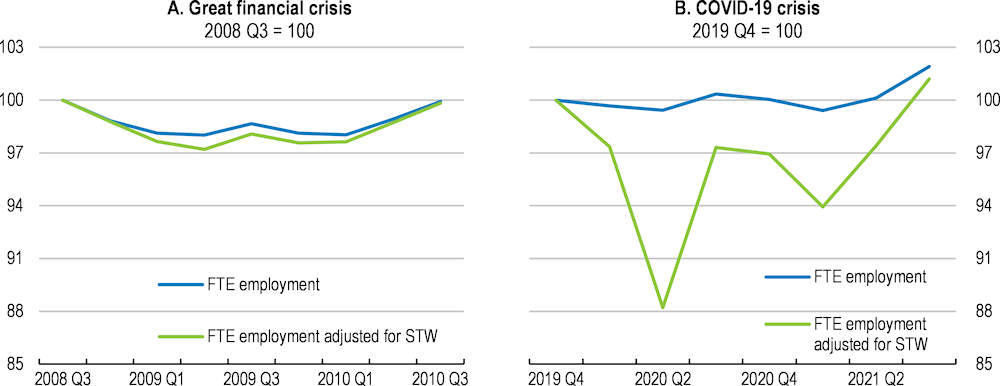

Box 5.1. The short time work compensation schemes protect employment during severe crises

The short time working compensation (STWC) scheme is the main instrument for bridging loss of work due to crises in Switzerland. Unemployment insurance (through which the scheme is administrated and funded) temporarily covers 80% of the loss of earnings attributable to the reduction in hours worked, capped at CHF 196 per day. In 2020, CHF 20.2 billion of additional funding was transferred to the unemployment insurance fund to cover the associated expenditures, of which CHF 10.8 billion (1.5% of GDP) was used. Companies experiencing a temporary downturn in activity could request it through the cantonal employment office. In March 2020, the application process was shortened and simplified, and the “waiting period” (period of two or three days per month during which an employer had to cover the full cost of employees on STWC) was abolished. The coverage of the STWC was also extended to types of employees not eligible within the usual legal framework: those with fixed-term employment contracts, temporary workers and apprentices). In addition, for low-income workers (earning less than CHF 3470 per month), the generosity of the compensation was raised in December 2020 to represent 100% of the loss of salaries (from 80%) (OECD, 2022a).

The STWC allows companies facing temporary reductions in demand to adjust employee working hours. During the GFC, full-time equivalent (FTE) employment fell by roughly 2%, while it would have fallen by roughly 2.8% in the absence of the STWC (Figure 5.8). However, the STWC was used substantially more during the COVID-19 crisis and safeguarded employment. FTE-employment dropped by only 0.6% but would have fallen by 11.8% in the absence of STWC (Figure 5.8). The STWC effectiveness was further enhanced during COVID-19 through simplified administrative processes and increased compensation for low-income workers (Hijzen and Salvatori, 2022).

Figure 5.8. Short time work compensation schemes have been used during past crises

Active labour market policies (ALMPs) play a vital role in matching job seekers with emerging opportunities. Switzerland invests significantly in ALMPs and training, although there is room for increased allocation in line with OECD best performers in this regard. The decentralised nature of activation policies, with cantons managing public employment services, allows for local responsiveness. However, greater adoption of targeted measures for specific groups of jobseekers across cantons can yield more positive outcomes in terms of job placements (OECD, 2022a). Furthermore, Switzerland can benefit from clearer placement strategies within cantons, particularly as regions lacking such strategies tend to underperform (The Federal Council, 2016aa). Effective coordination, evaluation, and adaptation of ALMPs at both the federal and cantonal levels are crucial to support workforce transitions effectively. The new “Strategy Public Employment Services 2030” adopted in June 2023 is a step in the right direction. The strategy outlines 12 objectives, including further developing targeted placement services, training, contact with employers and job seekers, as well as integrated digital solutions to improve matching and reduce the administrative burden. The strategy should be implemented as planned to improve the effectiveness of public employment services.

Overall, macroeconomic stabilisation policies have been deployed successfully to dampen the adverse effects of sharp downturns and have supported economic recoveries in Switzerland. However, other crisis management tools can be needed to safeguard the functioning of society in the event of temporary disruptions in GVCs. A case in point is the COVID-19 pandemic when supply bottlenecks reduced production (Frohm et al., 2021; Attinasi et al., 2021) and limited trade in necessary personal protective equipment. These disruptions threatened governments capability in limiting the spread of the virus. Resilience to temporary supply disruptions can be achieved through good private and public sector risk management practices, risk assessments and preventive measures. However, there are important trade-offs between resilience and efficiency. Increasing resilience may require private investments into larger inventories to ensure operations in the case of adverse shocks. Such investments come with costs that need to be borne by the company or the consumer. Furthermore, government spending on emergency stocks can cause moral hazard, whereby private companies underinvest in their own resilience as the public sector takes a larger role. These trade-offs need to be carefully balanced to optimise resilience and efficiency. In the medium to longer term, policy can facilitate companies’ diversification of supply chains through deeper international integration, lower barriers to trade, higher investment into research and development (R&D) and by fostering domestic competition.

Addressing supply disruptions

A successful strategy to mitigate risks related to supply disruptions must address problems before they occur, as well as when they materialise. Developing scenarios and contingency plans to deal with vulnerabilities, utilising monitoring systems to detect problems ahead of time and preparing to buffer shocks as they arise are key components of a comprehensive framework to increase supply resilience (OECD, 2021b). Mitigating risk also involves identifying policy settings and mechanisms that can be put in place to enhance preparedness and help with the absorption of the impact of acute disruptions. Encouraging some redundancy or spare capacity in production in areas of critical importance for the absorption of shocks is another example. Yet, efforts to strengthen resilience must be carefully balanced with their fiscal costs and potential adverse impact on the functioning of markets. As countries work to address resilience, trust in governance structures, and institutions are critical for public acceptance and adherence to necessary measures.

Switzerland has developed an advanced crisis preparedness strategy to deal with temporary disruptions to the economic supply, which is rooted in its experiences of food shortages, civil unrest, and significant state intervention during the First and Second World Wars (see Box 5.2). Article 102 of the Swiss Constitution enshrines the government’s obligation to ensure the economic supply during times of severe distress or crisis and this responsibility is implemented via the National Economic Supply Act (NESA). Through effective public-private cooperation, regular risk assessments and the monitoring of supply chains, coupled with substantial stockpiles of essential goods, Switzerland is well-equipped to overcome temporary disruptions in essential goods supply chains. Outside extraordinary events that prevent the functioning of economy, such as wars, pandemics or very significant disruptions, the guiding principle in Switzerland is that the private sector bears responsibility for supplying its citizens with goods and services.

A high degree of institutional trust help ensure compliance with public policies in Switzerland (Figure 5.9), especially in times of disruptions to society (OECD, 2021c). This aids collaboration between authorities and the private sector and helps in deploying measures to address emerging problems. In many countries, the COVID-19 crisis challenged the relationship between citizens and their governments in unprecedented ways (OECD, 2021a) and Switzerland experienced its share of protests and vocal opposition to official measures to counter the pandemic. Yet, Switzerland continues to enjoy very high levels of trust on the back of a stable and consensus-seeking political system (Szvircsev Tresch et al., 2023). For example, the Swiss people voted in favour of an extension of the COVID-19 law in a June 2021 referendum and voted to expand income support, increase testing, and introduce a COVID-19 certificate in a November 2021 referendum. A further extension of the COVID-19 law was passed via referendum in June 2023. This extension allows the government to swiftly deploy restrictive measures if new variants of COVID-19 occur by, for example, reactivating COVID-certificates and the SwissCovid app to curb the spread (The Federal Council, 2023a).

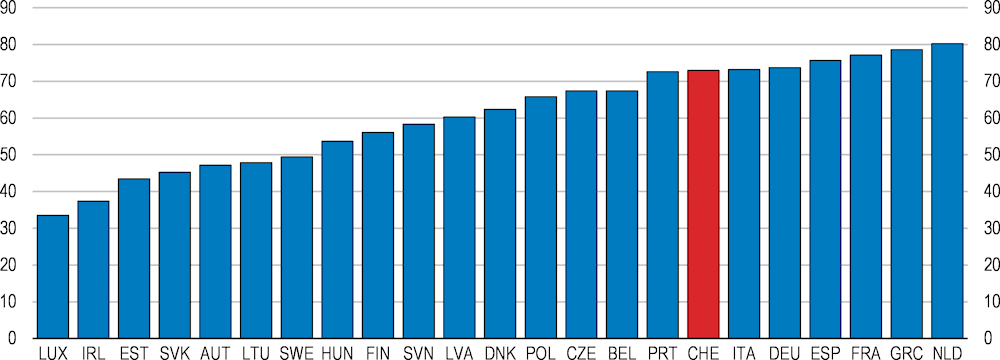

Figure 5.9. The public’s trust in the government is the highest in the OECD

Trust in government, % of all survey respondents, 2022 or latest available year

Notes: “Trust in government” refers to the share of people who report having confidence in the national government. The data shown reflect the share of respondents answering “yes” (the other response categories being “no”, and “don’t know”) to the survey question: “In this country, do you have confidence in… national government?

Source: OECD Government at a Glance database.

Box 5.2. Crisis preparedness has been elevated since the two World Wars

Switzerland relies heavily on imports for various goods and services. During the First World War, the country faced severe shortages of essential goods when neighbouring nations redirected their economies towards the war effort and imposed trade restrictions. To address the sudden halt in imports, particularly of foodstuff, the Swiss authorities established the Federal Food Office, which was responsible for rationing, supply, and procurement tasks. During the Second World War, the Federal Council used extensive powers to intervene in the economy and ensure the availability of essential goods.

Switzerland enacted several laws to secure its economic supply during the second half of the 20th century. For instance, the 1953 Navigation Act empowered the Confederation to acquire Swiss deep-sea vessels, while the 1955 Federal Act on Economic Provisions mandated compulsory stockpiling for the private sector. Following the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, the focus shifted from war-related events to addressing supply shortages caused by complex supply processes, environmental crises, epidemics, and trade conflicts.

In 2016, the Federal Assembly revised the National Economic Supply Act (NESA), assigning the Federal Office for the National Economic Supply (FONES) the responsibility of conducting regular risk assessments and preparing strategies to manage adverse events, including overseeing and monitoring private sector stockpiles (FONES, 2021b). Furthermore, Switzerland also has a well-developed National Risk Assessment process, coordinated by the FOCP (FOCP, 2021).

The Swiss Federal government has also actively encouraged individuals to build up their own emergency provisions. The “Kluger Rat – Notvorrat!” campaign, which has been running for the past 50 years through various media channels, advises people to maintain stocks of essential items to last at least a week (FOCP, 2021). Furthermore, Switzerland hosts over 370 000 shelters (essentially bunkers) that can cover the whole Swiss population in the case of armed conflict or natural disasters. The cantons and municipalities must plan and regularly update the allocation of the public to shelter places.

Sources: (Réservesuisse, 2023), (FONES, 2021a).

Anticipating supply disruptions

The Swiss Federal Office of National Economic Supply (FONES) plays a key role in identifying and evaluating potential risks that could disrupt the country’s economic supply of essential goods and services (Box 5.3). FONES is tasked with taking precautionary measures to address risks, which can include political tensions abroad, environmental changes, infrastructure failures, strikes or boycotts, and pandemics. These preparations align broadly with the OECD Recommendation on the Governance of Critical Risks (see Box 5.4).

FONES is also responsible for coordinating with other federal agencies, including the armed forces - the Federal Office for Defence Procurement (armasuisse) - and the Federal Office of Civil Protection (FOCP) as well as for disseminating information to the population. Key risk assessments and plans for shortages are consolidated in the Swiss National Economic Supply and Risks to the National Economic Supply reports, released every four years and annually respectively. These reports outline measures that the government can implement in case of disruptions, as was the case during the recent energy crisis (see Box 2.2 in the second chapter of this survey). From 2024, the two reports will be merged into one and released annually. The FOCP is responsible for ensuring the functioning of critical infrastructures, together with the operators of the infrastructure, supervisory and regulatory authorities and the cantons, that are instrumental to ensure the flow of goods, services, communication, energy and people. The armed forces and other governmental institutions involved in state security follow principles set out in the Principles of the Swiss Federal Council for the Armament Policy of the Federal Department of Defence, Civil Protection and Sport (DDPS). It outlines the main features of the collaboration between the armed forces and the private sector, and describes how access to crucial knowledge is to be facilitated in times of tension concerning security policy or armed conflict. The policy also states which principles are applied when collaborating with other countries and international organisations. Furthermore, armasuisse has developed an armaments strategy. The strategy focuses on securing modern, operational systems and related competences, as well as strengthening an innovative and efficient security-relevant technological and industrial base (STIB).

Box 5.3. The Swiss Federal Office for Economic Supply (FONES)

In Switzerland, FONES is responsible for ensuring the nation’s economic supply in the event of severe shortages that the economy cannot by itself counteract. Private-public sector cooperation lies at the heart of FONES’s organisational structure. It is led by a delegate from the private sector and staffed by experts from both the private and public sectors, totalling around 250 individuals. This collaboration ensures a deep understanding and expertise of the economy’s inner workings, enabling a swift response in the event of severe shortages.

FONES is divided into six sections: energy, foodstuff, therapeutic products, logistics, ICT, and industry. Experts in each field are responsible for planning and implementing measures to ensure supply within their respective sections. Their tasks are broadly categorized into two phases: prevention and intervention. During the prevention phase, the focus is on enhancing the resilience of private supply processes to curtail the need for government intervention. For instance, the organisation promotes dialogue among stakeholders to alleviate potential shortages. Simultaneously, measures are put in place for the intervention phase. The degree of intervention varies based on the severity of the shortages.

For example, at the outset of the COVID-19 pandemic, FONES together with the Federal Office of Public Health (FOPH) were informed by public hospitals of a shortage of certain essential medicines. After the first wave of COVID-19 in 2020, the FOPH and FONES monitored the pandemic situation and developed a catalogue of 50 active ingredients that were relevant to fight COVID-19. The list of products in inventories was under strict monitoring and updated on a weekly basis. Hospitals were also asked to deliver a weekly report on their inventories. Although the federal government assumed the lead in distribution, the pharmaceutical industry remained responsible for procuring the products. The industry was also granted a return guarantee for any additional supplies that exceeded the usual level of demand and were not sold, allowing the country to bridge shortages while limiting waste.

Box 5.4. The OECD Recommendation on the Governance of Critical Risks

The OECD Recommendation on the Governance of Critical Risks recognises the escalating damages that occur due to extreme events and for economies that are dependent on GVCs. The Recommendation proposes actions that governments can take at all levels of government, in collaboration with the private sector and with each other, to better assess, prevent, respond to and recover from the effects of extreme events, as well as take measures to build resilience to rebound from unanticipated events.

Identification and assessment of risks takes interlinkages and knock on effects into account. This helps set priorities and inform allocation of resources.

More investment in risk prevention and mitigation such as investments in protective infrastructure, but also non-structural policies such as land use planning.

Flexible capacities for preparedness, response and recovery help manage unanticipated and novel types of crises.

Good risk governance via transparent and accountable risk management systems that learn continuously and systematically from experience and research.

Source: OECD (2014).

Identifying vulnerabilities through good monitoring systems

Detailed monitoring of supply chain vulnerabilities is an integral part of effective crisis management (OECD, 2021a). Private companies normally have enough incentives to reduce risks of costly disruptions to their production. Prolonged delays in the delivery of inputs makes production and sales difficult which can lead to financial and/or reputational losses. Moreover, supply chain resilience when competitors struggle with resuming operation can help a company gain market share and earn extra profits. However, while the private sector bears the responsibility for identifying and addressing vulnerabilities that may threaten their individual operations, they can overlook the broader consequences of their actions on the overall economy and society (Acemoglu et al., 2012). In such cases, there might be scope for the government to monitor risks and disseminating information to the private sector actors to help them prevent supply chain issues from becoming systemic.

Different sources of data can be utilised to detect vulnerabilities and each have their own advantages and limitations. Timely private sector data can be used to track developments close to real time and global input-output tables provide an understanding of sectoral interlinkages across the global economy, whereas harmonised international trade statistics give a detailed view of vulnerabilities at the product level. However, private sector data often lack harmonised statistical classifications, making it difficult to reconcile with official sources and the construction and release of global input-output tables requires strong assumptions, large amounts of data and often takes several years, even though new statistical techniques may pave the way for updating GVC indicators before official data is available (Knutsson et al., 2023). Product-level trade data only capture direct trading relationships and do not consider the fact that much of modern trade takes place in GVCs. A good monitoring system of vulnerabilities in supply chains should draw on all types of available data, bearing in mind their strengths and weaknesses and share information with private and public sector actors about emerging problems.

Private sector data help monitoring bottlenecks in near real-time

Pressing problems have incentivised private actors to produce innovative data, as was highlighted during the COVID-19 pandemic (OECD, 2021d). In Switzerland, the website drugshortage.ch monitors the supply situation for prescription drugs for example. On the website, users can analyse data on delivery bottlenecks since autumn 2015. Only prescription medicines and over-the-counter drugs that are officially approved in Switzerland are listed in the database and it does not cover data on contract manufacturing or imported products. Since late summer 2022, the number of products in shortage has increased rapidly, highlighting the sharp increase in medical product shortages (see the next sub-section). Since 2016, the Federal Council also tracks official data on medical goods shortages. The latest report published in May 2023 registered a record number of shortages.

Timely data on medical supply bottlenecks serves as a good example of how the private sector can contribute to the monitoring of specific supply chains. To stimulate discussions with the private and public sector internationally, Switzerland organized an OECD conference on medical supply chains in 2023 to discuss the relevance and availability of data for efficient and targeted policy making (see also later in this section). The Swiss authorities should encourage private actors to maintain and further develop such systems and consider cooperating to ensure harmonised definitions and quality checks. One way to ascertain continuing production of data can be by setting up trusted data intermediary platforms, or appropriate contractual provisions.

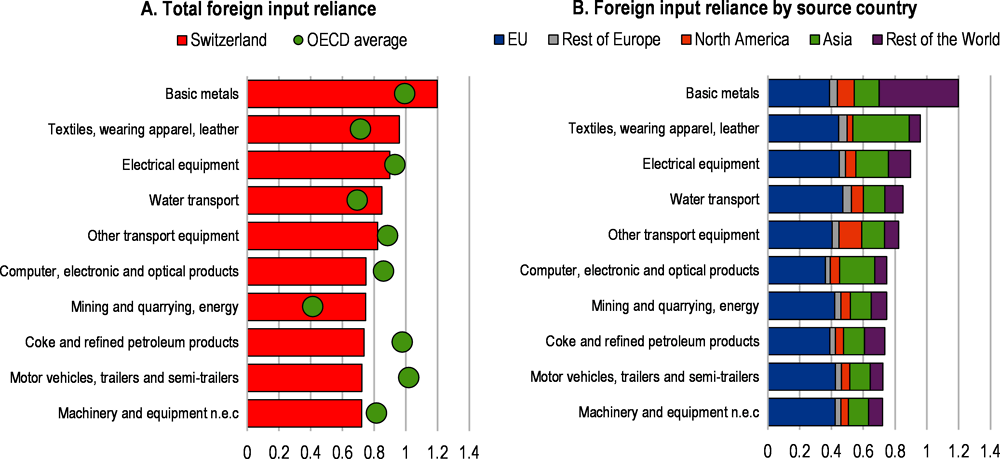

Global input-output tables outline sectors’ exposure to supply disruptions

To capture dependencies in GVCs, Schwellnus et al. (2023) constructs a new indicator of foreign input reliance (FIR), based on Baldwin and Freeman (2022) and the OECD’s Trade in Value Added (TiVA) database. The FIR broadly captures a sector’s exposure to foreign supply disruptions and considers the degree of exposure and the complexity of the value chain (i.e., they consider both direct trade and trade through second and higher order trading partners). According to the FIR, Swiss companies rely less on foreign inputs than the OECD average across most sectors (Figure 5.11, panel A).

The top sectors are manufacturing of basic metals, manufacture of textiles, apparels, and leather and related products, manufacture of electronic, electrical and optical equipment, water transport and the manufacture of other transport equipment. Inputs are mainly sourced from suppliers within the EU (54% of the total). Asian countries account for 17% on average, 10% are from North America, 8% from the rest of Europe and 11% from the rest of the world (see Figure 5.10, panel B).

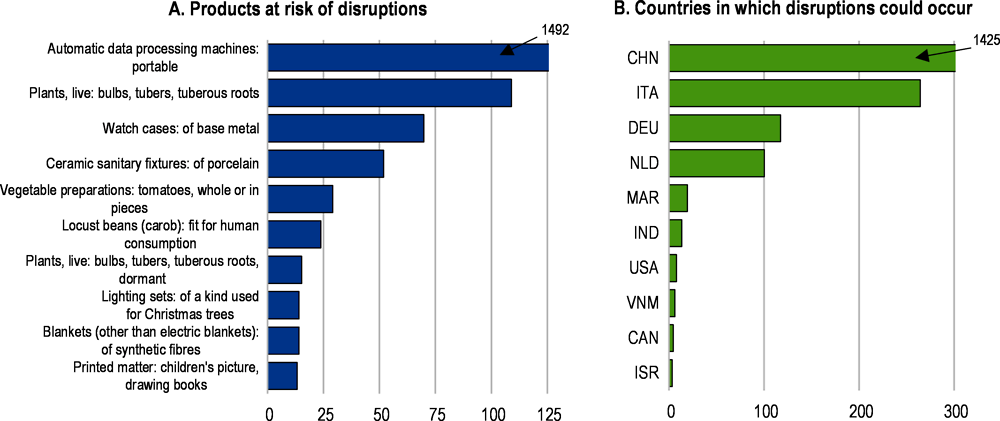

Product-level data provides a detailed view of trade dependencies

The Swiss State Secretariat for Economic Affairs (SECO) has developed a method to monitor import dependencies at highly disaggregated product levels (Lukaszuk and Ferreira, Forthcoming), inspired by the European Commission’s Supply-Chain Alert Notification (SCAN) system (European Commission, 2021). Applying SECO’s methodology on data from CEPII’s BACI database for the most recent year before the crisis (2019) and tracking products that are still at risk of disruptions two years after (by 2021) provides a list of about 60 country-product combinations. Figure 5.11, panel A shows the top 10 products in terms of import values and the countries contributing to them in Figure 5.11, panel B. The products range from foodstuff or plants, as well as high-tech data processing machines, mainly sourced from China, and to a less extent from EU countries.

Figure 5.10. Reliance on foreign inputs is generally lower than the OECD average

Percent, 2018

Source: Global value chain dependencies under the magnifying glass, OECD Science, Technology and Industry Policy Papers, March 2023 No.142.

Figure 5.11. Swiss product-level dependencies mainly come from China

Current USD, millions, 2021

Overall, Switzerland relies on several public and private data sources, as well as the private sector experts in FONES to monitor the supply situation and to identify risks. The use of private sector expertise guarantees detailed knowledge about sectors and products and facilitates contacts with companies that might be affected. Furthermore, FONES gathers company-specific information and merges it with market data and public statistics to create reports, dashboards and alert systems for centralised monitoring. This system should be continuously maintained to ensure that risk monitoring is up to date.

Bridging supply shortages through inventory management

Stockpiles of critical intermediate inputs and final products can help bridge a temporary shortage and dampen their adverse consequences (Crowe and Rawdanowicz, 2023). For example, natural gas storage facilities helped European economies cope with the risk of supply disruptions following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine (Bruegel, 2023). The stockpiling of medical devices and products facilitated the Swiss authorities fight against COVID-19 (OECD, 2023c). Several countries hold “buffer stocks” to influence commodity prices or to ensure availability in times of severe distress. Member states (including Switzerland) of the International Energy Agency (IEA) are committed to keep oil reserves to last at least 90 days of net imports (IEA, 2023).

The COVID-19 crisis raised interest in stockpiling a broader set of intermediate inputs and final goods for emergencies, both in the public sector and among companies (Alicke, Barriball and Trautwein, 2021). Since 2020, the United States has raised funding for the Strategic National Stockpile (SNS) from USD 727 million to 909 USD million (The Council of Foreign Relations, 2023). The European Union created “rescEU” in 2019, an EU-funded strategic stockpile of, among other things, medical items such as antidotes, antibiotics, vaccines and specific equipment (for example gas masks and protection suits) (European Commission, 2019). The stockpile has recently been expanded and now holds medical stockpiles worth around EUR 546 million (European Commission, 2023b). Finland, another small and open economy, holds large stocks of essential goods through its National Emergency Supply Agency (NESA) (see Box 5.5 and NESA, 2023).

Box 5.5. The National Emergency Supply Agency in Finland

Finland operates a national stockpiling system of essential goods through its National Emergency Supply Agency (NESA), which operates under the Ministry of Economic Affairs and Employment. Two Acts regulate its activities: The Act on the Measures Necessary to Secure Security of Supply (1390/1992) and the Government Decree on the National Emergency Supply (1048/2018).

NESA is tasked with planning and operative measures related to developing and maintaining security of supply. In cooperation with other authorities and the private sector, NESA’s primary objective is to safeguard the functioning of critical infrastructure, production and services so that they can meet the most vital basic needs of the population, economy and national defence.

Several tools are available to the authority, such as stockpiling of essential goods and medical equipment, or laws and regulations that require operators to ensure the continuity of their critical processes amid disruptions and emergencies. Emergency stockpiles of for example medical equipment and fuels are held by relevant companies but are mandated by NESA. Currently, the balance position of the National Emergency Supply Fund is EUR 2 billion, with most of the amount tied up in stockpiles.

Source: https://www.huoltovarmuuskeskus.fi/en/

However, it can be difficult to stockpile for every specific event, as was highlighted during the COVID-19 crisis and inventories will still be exhausted by a severe or prolonged disruption (Feinnman, 2021). Maintaining stockpiles or excess capacity can be costly, lead to waste and create inefficiencies. Another risk is that the existence of compulsory stocks may create “moral hazard” – that companies and households hold less inventories than they otherwise would – leaving overall economic resilience unchanged while increasing the burden for the public sector. A successful stockpiling strategy needs to address such concerns to effectively support the economy during a disruption without unwarranted burden on the private and public sector.

In Switzerland, roughly 300 companies are required to hold separate stocks of products deemed critical for the functioning of society (see Box 5.5). An advantage of the system is that it relies on the management and logistics of private companies, thus ensuring cost efficiency. The compulsory stocks consist of essential goods such as foodstuff, energy sources, therapeutical products and industrial goods. The Federal Council can – at its discretion – also sign voluntary stock agreements with companies for essential goods that are either in relatively low demand or have few suppliers, like raw material for yeast production, blood bag systems, plastic granules and uranium fuel elements. Currently, the voluntary stocks make up about 2% of the total stockpile. The items included in the system and their quantities are designed to cover a large disruption in various supply chains and to cover demand for roughly three months of the year, depending on the product. The market value of the stockpile is CHF 3.8 billion, which is roughly 20% higher than that of Finland in per capita terms.

The list of stockpiled items and their quantity is continuously reviewed by FONES together with federal and cantonal governments as well as companies. Moreover, the Federal Council has proposed to expand Federal guarantees from CHF 540 million to CHF 750 million over the next ten years, to finance the build-up of new reserves (The Federal Council, 2023b). Although heightened trade tensions may call for larger inventories, the current stockpiles can already maintain the country’s demand for three to four months in case of a “full stop” in imports. To ensure that the private sector maintains its responsibility for ensuring safe and resilient supply chains, the list of items in compulsory stockpiles should remain focussed on essential goods and not be expanded to cover longer disruptions.

Since 2015, the release of compulsory stockpiles largely concerns pharmaceuticals (and especially anti-infectives). Even if one excludes the COVID-19 pandemic, the release of medical products has taken place more than a hundred times. The regular release of medical products from the compulsory stockpile reflects persistent problems in the global pharmaceutical supply chain (OECD, 2023c). This may motivate larger inventories than before, to better prepare for disruptions. Yet, the frequent disbursements could also signal that actors on the market are not holding enough inventories themselves, in particular regarding anti-infectives.

Problems in the medical supply chains have long been known. To improve their functioning, the Swiss authorities have conducted a series of analyses and prepared policy proposals (FOPH, 2022). Still, the problems remain. The authorities should thus continue to review, evaluate and implement appropriate recommendations included in (FOPH, 2022), to alleviate shortages and improve the functioning of the market. In this respect, it is key to collaborate and coordinate internationally with main trading partners, as well as improve monitoring and define roles of stakeholders. In this respect, Switzerland is strongly involved in fostering a dialogue within the OECD’s Trade Committee among government and private sector representatives on the resilience of medical supply chains.

Improving market access by simplifying authorisation procedures and by easing the imports of medicinal products that are already authorised in countries with equivalent standards could help ease shortages. In the case of a severe disruption, imports of medical products that are not already approved in Switzerland could be considered. This is already possible following legislative changes in January 2019. However, these provisions could be used more frequently and expanded to handle emerging shortages. Lastly, to be efficient and effective, the Swiss stockpiling strategy for pharmaceuticals should be planned and coordinated with trading partners (OECD, 2023c).

While the government can help bridge temporary disruptions, the overarching principle in Switzerland is that individual companies are responsible for building resilience of supply chains, as they are best positioned to decide the acceptable level of risk and how to organise themselves to reduce vulnerabilities. Indeed, Swiss companies have been able to deal with supply disruptions during the COVID-19 crisis by increasing inventories to make their production less susceptible to bottlenecks (SNB, 2023). Additionally, three out of four Swiss industrial companies indicated their intent to adapt supply chains due to the bottlenecks. One third of those companies mainly sought diversification among global suppliers, with a focus on increased purchases from European and Swiss sources, while reducing reliance on Asian counterparts (Föllmi, 2023). Furthermore, some Swiss companies that buy critical inputs from China have reduced their sourcing recently, largely by increasing purchases from the rest of Europe, and to a lesser extent by increasing own production in Europe or adapting production processes (Eichenauer and Domjahn, 2023).

Box 5.6. Switzerland stockpiles essential goods and materials

In Switzerland, private companies are mandated to hold stocks of essential goods and critical inputs. The list of products included in the stockpiling system is proposed by private sector experts and approved by the Federal Council. The organisation of the stockpiling of the listed products is supervised by FONES and implemented by the private sector. However, the federal government is not the owner of the compulsory stock; it remains the property of the companies (decentralised stockpiling). If the economy can no longer meet the demand for vital goods due to a shortage, the stock can be released by order of the federal government.

Once a company is mandated to hold compulsory stocks, FONES signs an agreement with the company, which is then ordered to join an industry-level stockpiling organisation that is supervised by FONES: (Réservesuisse (Foodstuff), Agricura (Fertilisers), CARBURA (Liquid fuels), Provisiogas (Naturalgas) and Helvecura (Therapeutic products). The five stockpiling organisations are in turn responsible for supervising the individual companies and to manage the “guarantee funds”. These funds are financed via levies on imports, which finance the stockpiling system and are used to reimburse companies for expenses related to storage, capital and administrative costs, as well as price losses related to the stocking of goods. The Swiss authorities also guarantee bank loans (worth around CHF 540 million) that can be used to finance compulsory or voluntary stocks. These loans face the interest rates of the Swiss Average Rate Overnight (SARON) or 0% if the SARON is negative. The costs of the whole stockpiling system are estimated to be in the range 12-14 CHF per person and year (FONES, 2023).

The list of items and prescribed quantities (in terms of demand coverage) has changed since the early 1990s. The coverage of the compulsory stocks has declined substantially – for some products like sugar, rice and cooking oils from 10-12 months to 3-4 months of demand – reflecting the increased integration of the global economy and better developed commodity markets. Currently, most essential products in the system are expected to fully cover demand for the Swiss population for roughly one quarter of the year.

Compulsory stocks are only to be released in times of severe shortages. The situation is first analysed by FONES private sector experts, who may request the Federal Department of Economic Affairs, Education and Research (EAER) to order a release of the stocks. If warranted, the EAER may then order the release and FONES amends the compulsory stock agreements accordingly. Measures typically relate to the release of various fuel oils in connection to freight disruptions, or problems in the supply of medical products.

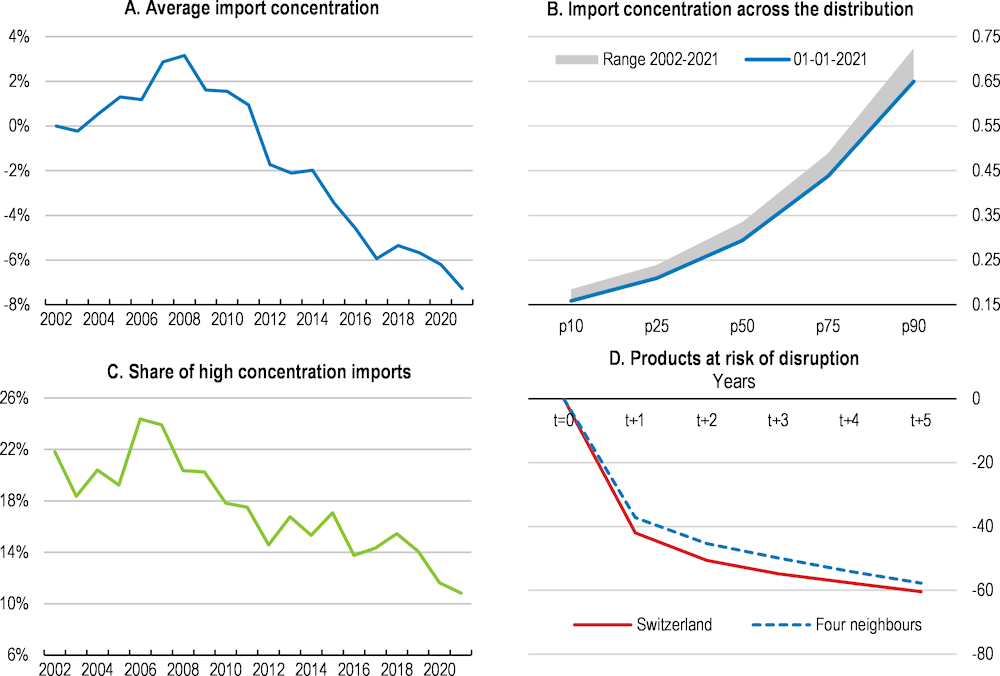

Furthermore, the average level of import concentration in Switzerland, as measured by the Herfindahl-Hirschman Index (HHI) of Swiss imports, has fallen by 7% since 2002 (Figure 5.12, panel A) and has decreased for both low and high concentration products (Figure 5.12, panel B). Products with high concentration (measured by an import HHI over 0.4, an analytical threshold used by the European Commission (2021), now represent a significantly lower share of total imports than in the early 2000s (Figure 5.12, panel C). The share of products imported to Switzerland that may be more at risk of supply disruptions (products with an import HHI above 0.4, imports are higher than exports and where the global export HHI is above 0.4) tends to be reduced by roughly 50% percent after two years (Figure 5.12, panel D) (Lukaszuk and Ferreira, Forthcoming). After five years, the number of products at risk of disruption have fallen by another 10 percentage points on average. This underscores companies’ adeptness at reducing dependencies, by diversifying their suppliers, substituting production processes or adopting technological innovation.

Requests by companies for FONES to release compulsory stocks are frequently denied by the authorities, on grounds that the disruptions are not deemed critical enough at a national level and may distort competition and the functioning of markets. Nonetheless, there are concerns that companies may be increasingly expecting government support in times of crisis, diminishing the private sector’s incentives to implement adequate risk management practices. For example, close to half of all the companies surveyed in 2023 expect the government to support them financially in the event of a crisis (Credit Suisse, 2023). Switzerland should maintain its current guiding principles whereby it is up to the private sector to safeguard the stability of supply, while continuing its private-public cooperation to handle severe and temporary disruptions. Maintaining a conservative view of when compulsory stocks are released will help ensure private sector accountability and public acceptability and continue to minimise moral hazard.

Figure 5.12. Swiss companies have effectively resolved risky dependencies

Notes: Panel A shows the average HHI for Swiss imports over time, indexed to 0 in 2002. Panel B shows the import HHI in 2021 compared to earlier periods over the distribution of the HHI. Panel C shows the share of imports of products that are highly concentrated (above HHI 0.4). Panel D shows the time evolution of products that are at risk of disruption (defined by Lukaszuk and Ferreria (Forthcoming) as import HHI >0.4, global export HHI > 0.4 and imports>exports). The y-axis shows the % change from the first year the products passed the filter and are considered at risk of disruption.

Sources: CEPII and OECD calculations.

Increasing resilience through deeper trade integration

Stable, transparent and predictable trade and investment regimes reduce uncertainty and trade costs. These conditions empower companies to build long-term relationships, efficiently adjust their supply chains while retaining their access to foreign markets, thereby fostering flexibility if the need for change in production or supply arises. Although greater integration in the global economy can heighten a company’s exposure to adverse foreign shocks through the supply chain (Frohm and Gunnella, 2021), limiting participation also comes at a cost. Recent studies emphasise that in the event that trade tensions would result in a “block divided” global landscape, the welfare cost could range from 1-12% (Cerdeiro et al., 2021; Góes and Bekkert, 2022; Attinasi, Boeckelmann and Meunier, 2023). Furthermore, studies underscore that countries have more volatile GDP when trade is more restricted and conversely less volatile GDP when trade is more open (Arriola et al., 2020; OECD, 2021e; IMF, 2022).

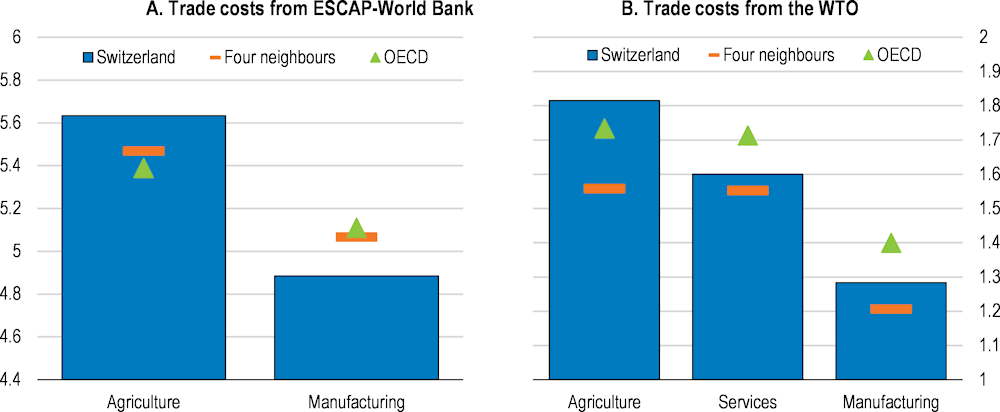

Lower trade costs would enhance Swiss companies’ ability to discover new ways of increasing the resilience of their supply chains in a cost-effective manner. This is because open trade makes markets “thicker”, by expanding the number of possible suppliers and buyers, helping companies to deal with supply-related risks if – and when – they occur (IMF, 2022). Effective trade costs represent all factors constraining international trade versus domestic trade and can be calculated in different ways (Arvis et al., 2016; Rubínová and Sebti, 2021). Yet depending on method and assumptions, the level of trade costs varies across sources. According to the UN/World Bank ESCAP database, agricultural trade costs are higher in Switzerland than its four neighbours (Austria, Germany, France and Italy and the OECD average, while lower in manufacturing (Figure 5.13, panel A). According to the WTO’s Trade Cost Database, which has a more granular sectoral dimension and also includes services, effective trade costs are lower in Switzerland than the OECD average in manufacturing and services, yet higher than in the four neighbouring countries (Austria, Germany, France and Italy), see Figure 5.13, panel B. While there is uncertainty on the level of trade costs, there appear to be scope to reduce them in particular in agricultural and services trade.

Lower trade costs could be achieved by signing new free trade agreements, and deepening existing ones, by improving at-the-border regulations and procedures, as well as further investments into digital infrastructure. Besides the longer-term welfare gains widely documented in the literature (Bernard et al., 2012; Melitz and Trefler, 2012; Bloom, Draca and Van Reenen, 2016; Feenstra and Weinstein, 2017), new estimates show that lower trade costs would also boost economic activity in the short term, with more pronounced effects in sectors that are more integrated in GVCs, see (Box 5.6) and (Frohm, Forthcoming).

Figure 5.13. There is scope to reduce effective trade costs

Notes: The effective trade costs are estimates of the costs involved with international trade relative to domestic activity. Panel A shows trade costs derived from ESCAP-World Bank for agriculture and manufacturing, averaged across destination economies in 2021. Panel B shows trade cost estimates from the WTO, average across ISIC Rev. 4 sub-sectors in 2018. The trade costs are expressed as ad-valorem equivalents, in logarithms. This is the additional cost (in %) that is associated with trade between countries relative to within countries. These costs involve transport and travel costs, information and transaction costs, ICT connectedness, trade policy and regulatory differences, governance quality and other factors like geography. Rubínová and Sebti (2021) shows that transport and travel costs, trade policy and regulatory differences and information and communication technology is especially important for the variation in trade costs. Four neighbours refer to Austria, Germany, France and Italy. OECD is a simple average of OECD countries.

Sources: ESCAP and the WTO.

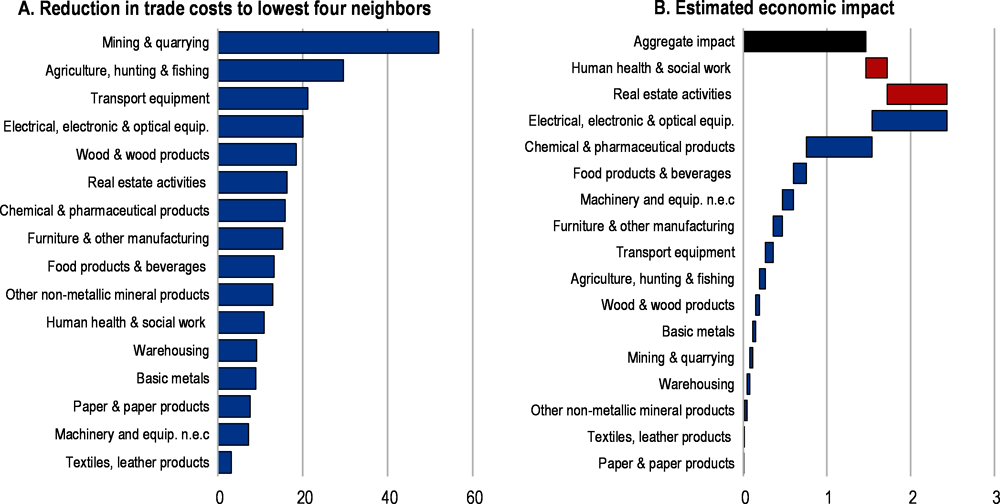

Box 5.7. Lower effective trade costs would yield significant economic gains

Lowering trade costs can generate substantial economic gains by improving access to final markets and intermediate inputs. Frohm (Forthcoming) estimates that a decrease in sectoral trade costs is associated with higher economic activity, but the impact is heterogeneous across sectors and depend on their participation in GVCs and trade in intermediate inputs (Taylor et al., 2023). This box provides illustrative estimates of the economic impact of Switzerland lowering its trade costs towards the sector with the lowest trade costs in its four neighbouring countries (Austria, Germany, France and Italy). The scenario includes trade cost reductions of 73%, based on Rubínová and Sebti, (2021), considering that some costs are driven by geographics.

Three factors shape the estimated impact on real value added: 1) Sectors’ participation in GVCs, 2) their share in Swiss real value added and 3) their current trade cost relative to the benchmark. The illustrative scenarios assume that trade costs are reduced by 16% on average, ranging from 52% in mining and quarrying to 3% in textiles and wearing apparel (Figure 5.14, panel A). The estimated aggregate impact of lowering trade costs towards the frontier in each sector, amounts to an increase 1.5% in real value added, driven primarily by increased value added in electrical, electronic and optical equipment as well as chemical and pharmaceutical industries (Figure 5.14, panel B). Some of the estimated economic gains are hampered by lower activity in services sectors like real estate and human, health and social work.

Figure 5.14. Lower trade costs could boost Swiss economic activity

Trade cost reduction (in %) and estimated impact on real value added (in %)

Notes: The figures utilise estimates and data (Frohm, Forthcoming). It assumes that all sectors lower their current trade costs to the benchmark (equivalent to the figures in panel A). Only trade costs that are not related to geographical factors, based on estimates from Rubínová and Sebti, (2021), are assumed to be lowered. This corresponds to reducing trade costs by 73% compared to benchmark sectors in the four countries bordering Switzerland (Austria, Germany, France and Italy). Panel B shows the contribution by sector to the estimated aggregate impact.

Source: (Frohm, Forthcoming).

The results are only illustrative and subject to several caveats. First, it is assumed that the association between trade costs and real value added is linear and the same irrespective of policies used to lower trade costs. Second, there may be non-linear threshold effects in the relationship between trade costs and economic activity. Third and finally, GVC participation and the contribution of sectors to national real value added could change over time, which would alter the estimated effect.

Deepening and expanding free trade agreements

To reinforce supply chains, limit risks and support open trade, Switzerland should deepen its international cooperation with key trading partners. In July 2022, many OECD and non-OECD countries united to address supply disruptions through the Supply Chain Ministerial Forum. Based on the Joint Statement, the signatories will work together to alleviate short-term disruptions and bottlenecks in transport and logistics, as well as address the long-term challenges of supply and value chain resilience in line with regulatory frameworks and the participants’ international commitments. Switzerland’s adoption of the Joint Statement in May 2023 signals its commitment to international cooperation. The government should continue to work for open trade in international fora.

Signing new free trade agreements (FTAs), deepening existing ones and reducing remaining tariffs would offer Switzerland’s economy further flexibility in adjusting to future disturbances by allowing companies to diversify suppliers. The geographical composition of trade has changed in recent years, as Swiss companies have diversified imports across countries and regions. Since 2010, the import shares from North America, Central and South America, Asia, Africa and Oceania have increased.

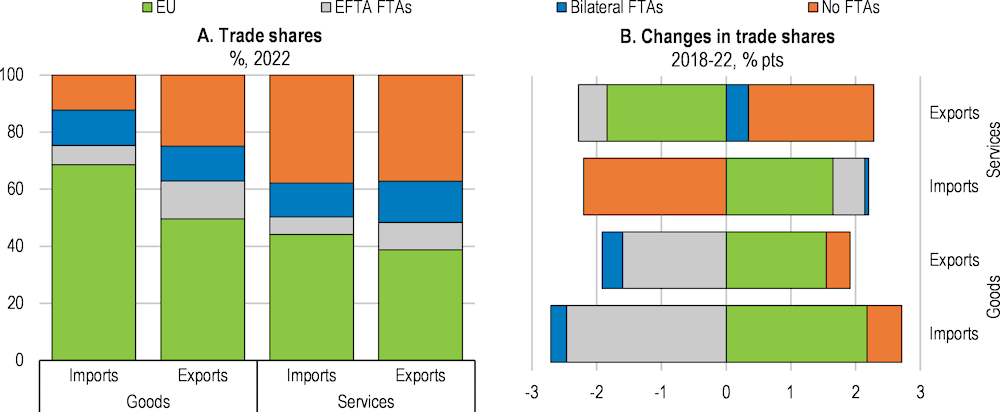

Most Swiss exports and imports already flow within FTAs (Figure 5.15). Nonetheless, there is scope to increase the usage of the existing FTAs by improving administrative procedures and providing more information about them (Box 5.7). Clearly structured and understandable information in a centralised location can help increase the use of FTAs and reduce the effort that companies need to use them. Moreover, making it easier for companies to comply with preferential rules of origin could facilitate the use of FTAs for imports (EY, 2022). Furthermore, existing and new FTAs could be amended to include provisions on security of supply and maintaining trade open when there is a crisis. An example is the Australia-Japan FTA, where the parties commit to co-operate and not to introduce measures that would reduce supply of energy and minerals in the partner economy in the event of a shortage (Department for Foreign Affairs and Trade, 2015).

Figure 5.15. The EU is Switzerland’s largest trading partner

Notes: Partners included in EFTA for services are approximated with imports/exports to Norway, Canada, Mexico, South Africa, Israel, North Africa, Gulf Arabian countries, Hong Kong, Türkiye, and Singapore.

Sources: OECD calculations based on Federal Office of Customs and Border Security (FOCBS) and SNB data portal.

Switzerland’s largest trading partner is the EU (seeFigure 5.15) and most of the gains from trade are derived from trade with the members states (Hepenstrick, 2016). The bilateral relationship with the EU is currently governed by roughly 120 treaties that have been signed over the years. Switzerland is a member of the border-free Schengen Area, is closely integrated with the EU in areas such as transport, research, higher education (through participation in EU-programmes) and enjoys access to the single market in different sectors. While efforts to conclude a more encompassing “framework agreement” came to a standstill in May 2021 when the Federal Council officially ended negotiations, a draft mandate for negotiations with the EU on a new broad package was finalized in December 2023. Switzerland should pursue efforts to stabilise relations with the EU and further increase economic integration. An erosion of the Switzerland-EU partnership would raise uncertainty, be harmful for Switzerland’s external trade and competitiveness and decrease its economic resilience.

Box 5.8. The use of Switzerland’s free trade agreements

In addition to the free trade agreement (FTA) with the European Union (EU) and the European Free Trade Association (EFTA) Convention, Switzerland has a network of 33 FTAs signed with 43 partners. The FTAs are usually negotiated and concluded together with the EFTA-partners – Norway, Iceland and Liechtenstein. Yet, Switzerland has the possibility to also conclude bilateral agreements, as it has with the Faroe Islands (in 1994), Japan (in 2009), China (in 2014) and the United Kingdom (in 2021).

The FTAs are well used by Swiss companies, with a usage rate of 73% for imports (SECO, 2023b). The usage rate is better than for the EU average yet lagging behind the best performing countries (Figure 5.16). There are several reasons why companies may choose not to use an FTA, depending on the products that are traded and their preferential rules of origin. For certain products that are produced in highly fragmented international value chains, it is sometimes difficult for companies to fulfil the preferential origin rules. Furthermore, companies must document the manufacturing process and, if necessary, adapt it to achieve preferential origin (SECO, 2022b). Companies may therefore decide against the use of FTAs if the costs of these adjustments exceed the potential benefits. Generally, tariff savings through FTAs allow Swiss companies to offer their products at lower prices on final markets (SECO, 2022b).

Figure 5.16. There is scope to increase the use of FTAs, primarily for imports

Preference Utilisation Rate, on imports, 2021, %

Note: The preference utilisation rate (usage rate) indicates the value of trade that takes place under preferences as a share of the total value of trade that is preference eligible in an FTA.

Sources: European Commission and SECO.

The United States is the second most important trading partner of Switzerland, yet progress on an FTA has stalled. An FTA would eliminate remaining tariffs and provide legal certainty to Swiss and US companies operating in both countries. It could generate additional cost savings, and boost trade and productivity. Since 2021, Switzerland has a bilateral FTA with the United Kingdom, encompassing primarily goods trade, including provisions on preferential tariffs, non-tariff measures including sanitary and phytosanitary measures and government procurement. Moreover, the two countries concluded a Services Mobility Agreement in 2020, allowing for temporary work permits, and a Mutual Recognition Agreement (MRA) in 2022, allowing a set of goods to be sold in both countries but only being subject to regulation in one of the jurisdictions. Despite these advancements, there is scope to deepen integration, notably in services and digital trade, investment flows and intellectual property rights. In February 2023, the Federal Council approved a negotiating mandate to enhance the bilateral trade agreement with the United Kingdom. Additionally, Switzerland should continue to work together with its partners in the European Free Trade Association (EFTA) to deepen its existing free trade agreements and pursue new ones, including finalising the ongoing negotiations with Latin American countries in MERCOSUR, India and Thailand.

In January 2024, Switzerland unilaterally eliminated all tariffs of industrial goods. This decision was made by the Federal Council in February 2022, after an amendment to the Customs Tariff Act was passed by Parliament in October 2021. Beside reducing import costs, companies are expected to face less administrative costs for importing industrial goods, with welfare gains estimated at CHF 860 million (SECO, 2023c). The Federal government plans to monitor the effects of the policy change, by assessing whether cost advantages accrued by companies are passed on to consumers (Meyer, Mergele and Lehmann, 2023).

The unilateral elimination of industrial tariffs is a welcome step, yet there is room to further reduce barriers to trade, particularly in agriculture. Switzerland has reduced some of its government backing to the agricultural sector in recent years but support to producers remains at around 50% of gross farm receipts compared to 19% for the European Union and almost three times the OECD average (OECD, 2022c). As recommended in the past (OECD,2017, 2019 and 2022a), less direct support and more import competition would raise agriculture productivity and lower prices. Continuing efforts to decouple income support from farm output would also decrease pressure on the environment and strengthen competitiveness and resilience in the sector (OECD, 2022c).

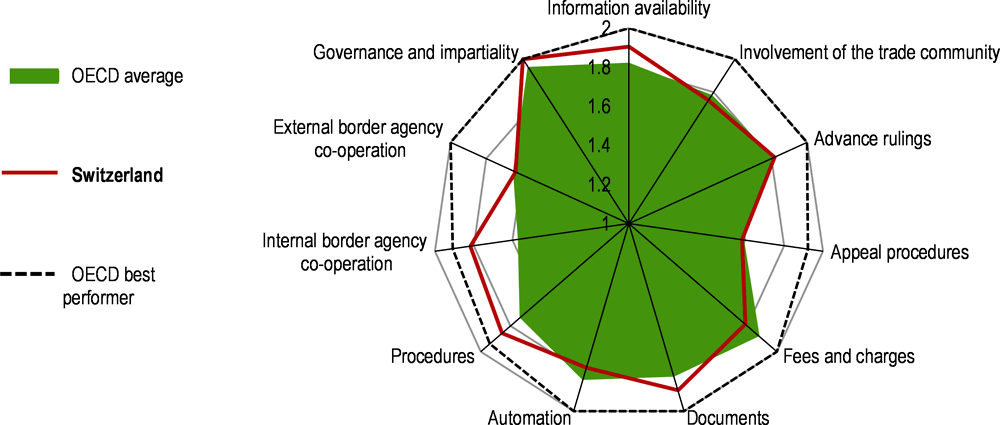

Improving trade facilitation and reducing barriers to trade and capital flows

Behind and at-the-border regulation, the quality of infrastructure and digital connectedness can act as barriers or enablers of trade (Moïsé, Orliac and Minor, 2011; Novy, 2013; Ohnsorge and Quaglietti, 2023). Some of these factors are captured by OECD’s Trade Facilitation Indicators, where Switzerland fares better than the OECD average but lags best performers (Figure 5.17). In particular, fees and charges, automation of process and external border agency co-operation is worse than the OECD average. Increasing information availability and procedures relating to pre-arrival processing of imports would help. For example, the way in which information is made available are likely to have an incidence on trade costs. Access to import/export requirements and the relevant administrative forms from a distance, without the need to physically visit government agencies’ offices, reduce the time and cost of obtaining information. While both small and large companies tend to benefit from improvements in the overall trade facilitation environment, small companies tend to benefit more (López González and Sorescu, 2019). Improving trade facilitation can thus help SMEs internationalise further and enable them to diversify supply chains. Simplifying and accelerating customs clearance of goods, by further digitalising processes, can help lower costs for companies.

The Swiss authorities are currently working on a complete revision of the Customs Act to simplify and standardise processes concerning the controls of goods and collection of fees. Reforms will focus on the successful modernisation and digitalisation of custom procedures. The revision is currently discussed in the Swiss Parliament. As such, the details of the changes to the draft legislation are yet to be determined. In this context, it is imperative that any revised legislation goes in the direction of reducing the administrative burden.

Figure 5.17. There is scope to improve trade facilitation measures

OECD Trade Facilitation Indicators, from 0 to 2 (best performance), 2022

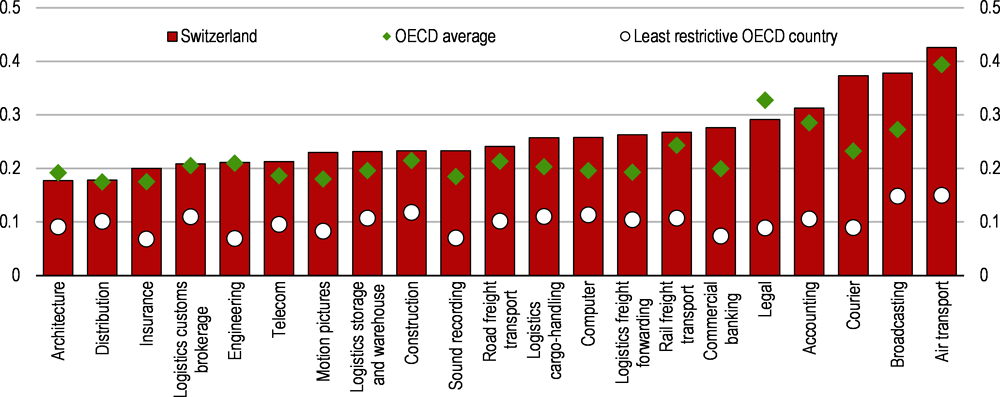

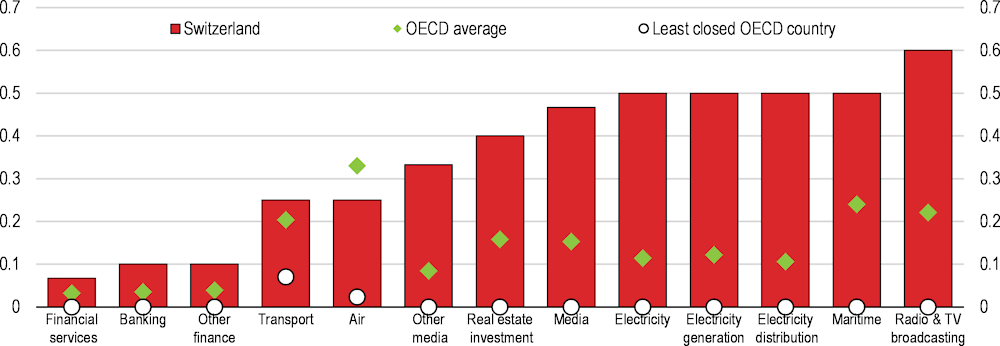

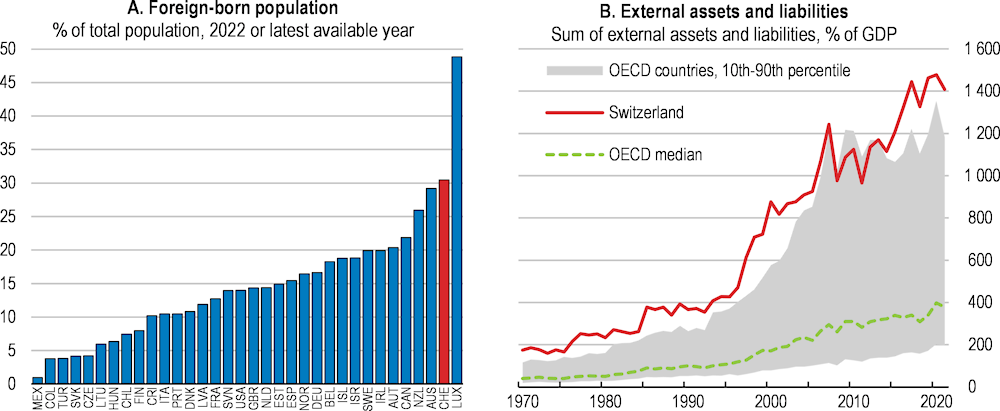

Switzerland is restricting services trade more than other OECD countries (Figure 5.18) and has only made moderate progress over the past decade. Despite some liberalisation efforts, restrictions on movement of people remain for independent services suppliers, constituting a cross-sectoral barrier to services trade. Quotas and labour market tests are applied for workers seeking to provide services in the country on a temporary basis, contractual services suppliers or independent services suppliers. Procedures to register a company are also relatively burdensome.

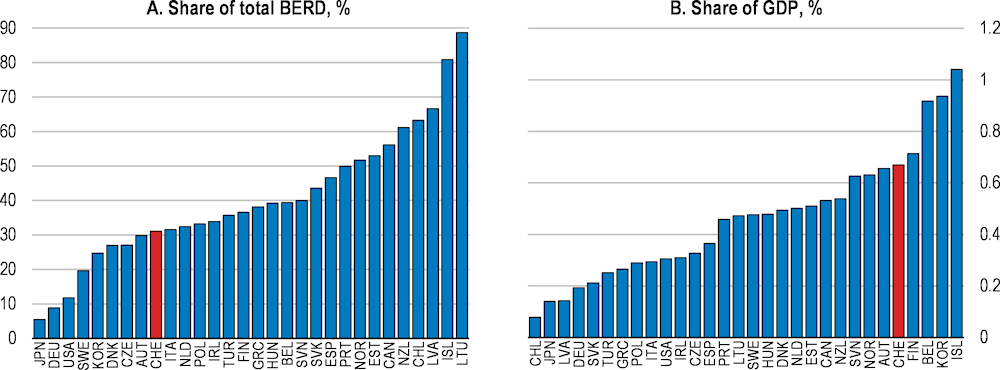

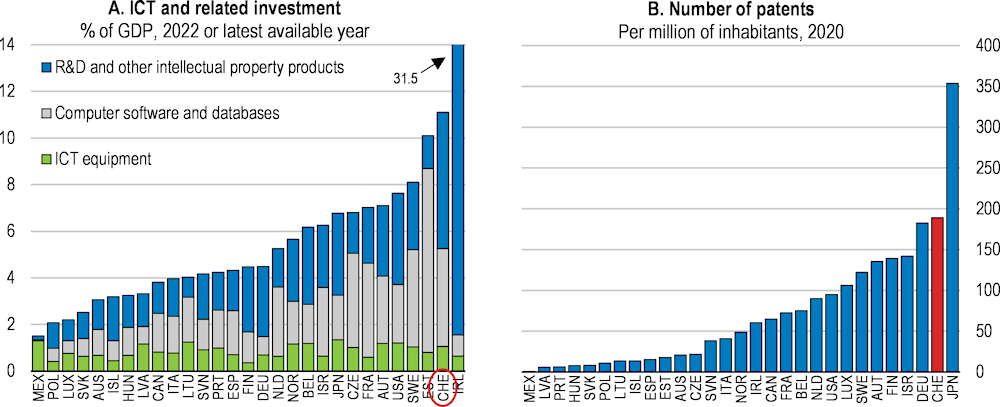

As mentioned in the first chapter of this Survey, as well as in previous surveys (OECD, 2017, 2019 and 2022a), easing immigration requirements from non-EU countries would help ensure Switzerland access to high-skills workers and lower barriers to services providers (Siegenthaler, 2023). The complete removal of immigration restrictions of EU workers in 2004 was controversial, yet their removal did not cause unemployment nor depress wages (SECO, 2023d). Furthermore, evidence shows that the removal of restrictions on cross-border workers (CBW) positively affected Swiss companies and workers: the reform is found to have increased wages of highly educated native workers by around 5% and led to substantial gains in labour productivity (Beerli et al., 2021), especially for companies that reported to labour shortages prior to the reform. The policy change is also found to have increased patent applications, product innovations and an increase in the net entry of establishments (Beerli et al., 2021). Further liberalising migration could strengthen innovation and productivity, and thereby increase the resilience of the Swiss economy.

The 2021 reform on the Federal Law on Public Procurement represents an important step in the direction of greater harmonization between federal and cantonal legislation, as well as a modernised policy regime on public procurement. The reform introduced a new channel for the Swiss Contracting Authority to allow foreign providers to participate in tenders for procurement outside the scope of international treaties. While this widens the potential participation from foreign actors, the measure may be weakened by reducing the scope to challenge the Authority’s decisions only to instances where reciprocal conditions are demonstrated for Swiss tenderers.