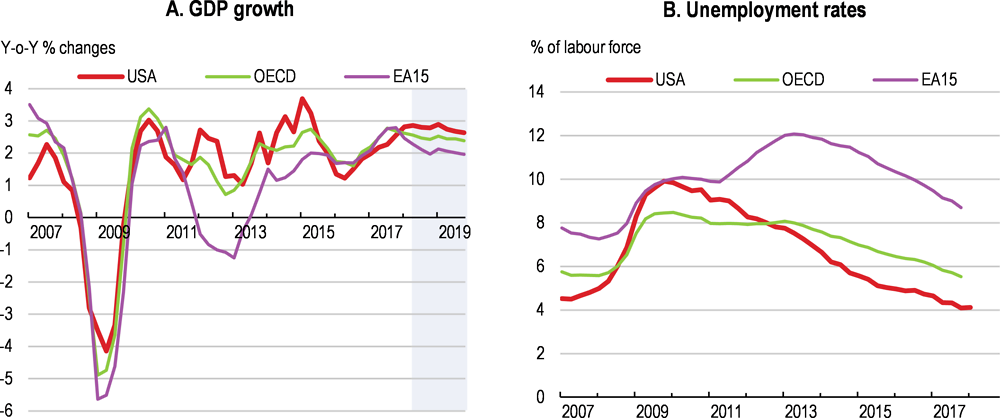

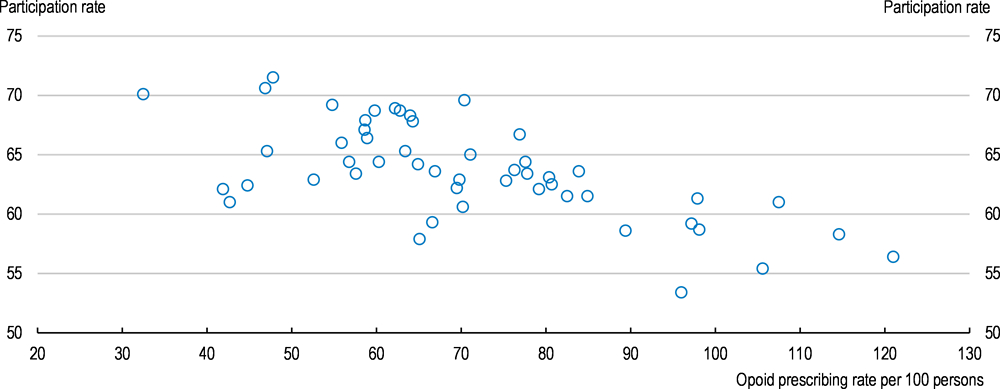

The current expansion is now one of the longest on record and amongst the strongest recoveries in the OECD. Only the expansions during the 1960s and 1990s are of comparable length since records began in 1854. The expansion has been job rich and has helped bring people back into the labour market, but the rate of output growth has been modest (Figure 1). While well-being has benefited from job growth, the legacy of the great recession and past structural shocks - such as globalisation and automation - remains painfully visible across the country, notably in the industrial heartland. Joblessness, non-participation and poverty are concentrated in distressed cities, notwithstanding robust job growth in coastal areas and well-connected metropolitan areas (Weingarden, 2017[1]; Austin, Glaeser and Summers, 2018[2]). This has been exacerbated by fewer opportunities to thrive irrespective of one’s origin, which is central to the American social model. The dislocation of opportunities is also associated with the opioid epidemic, which tends to be most pronounced in areas suffering from employment loss. In addition, not all families have enjoyed the benefits of economic growth and workers are worried about the impact of automation on their lives (Smith and Anderson, 2017[3]).

OECD Economic Surveys: United States 2018

Key policy insights

The expansion is now one of the longest on record

Figure 1. The economy has grown steadily and unemployment has fallen

In a rapidly changing global environment, competitiveness remains a challenge. Measures to support faster productivity growth, boost investment, raise labour force participation and improve skills will be important for sustaining the expansion in the future. As the labour force ages and the baby boom generation retires, bringing people currently on the side-lines into employment could mitigate some of the demographic pressures and further boost incomes, particularly of lower-income households.

After a long period of monetary accommodation, a number of concerns have accumulated with debt in the non-financial corporate sector elevated relative to historical norms and by various measures house prices are high in some cities (though not nationally). Bloated levels of public debt are a legacy of the financial crisis and the federal government continues to run a deficit. Finally, the current account records a deficit, reflecting low national savings. Although none of these factors is currently a problem, they could be problematic in case of a severe shock.

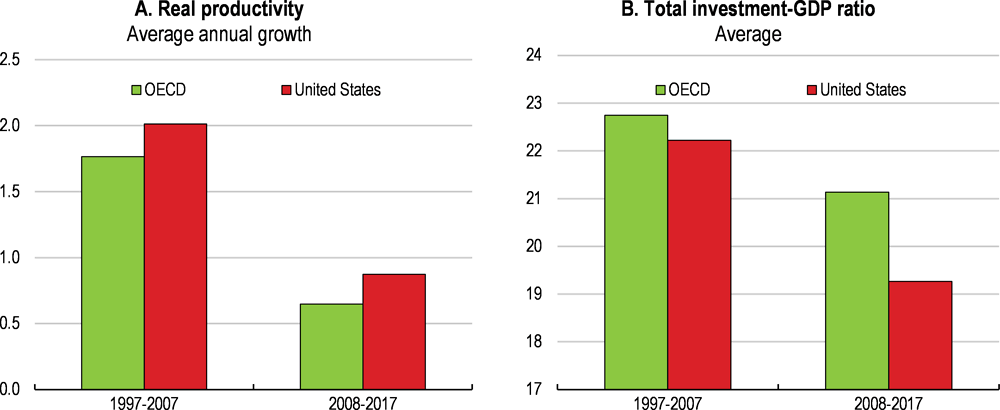

With little remaining observable labour slack, sustaining future growth in living standards will require stronger productivity growth (Figure 2). In the current expansion, labour productivity growth has averaged only 1.2%, well below those observed in the previous expansion (2.6%) and over the past half century (around 2%). Why productivity is anaemic despite the abundance of digital innovation is not fully understood; contributing factors include the slow pace of non-residential investment, weak rates of business entry and exit, tighter regulations and the lack of knowledge spillovers among firms.

Figure 2. Labour productivity growth remains weak

In view of these challenges, the Administration has focused on a new set of priorities intended to improve the business environment, boost productivity and improve work opportunities. The priorities set out by the Administration in the Economic Report of the President include initiatives to reform taxes, reduce the regulatory burden and boost the supply of infrastructure (CEA, 2018[4]). The initiatives also target the labour market to improve opportunities for workers as well as to combat opioid addiction. Against this background, this report focusses on:

How to rebalance macroeconomic policy as monetary policy is gradually tightened and fiscal policy loosens while ensuring that financial market risks remain contained.

How to raise living standards by bringing workers into the labour force and boosting productivity growth;

How to improve the employment opportunities for workers facing adverse shocks and prevent dislocations in outcomes;

The expansion is supporting wellbeing

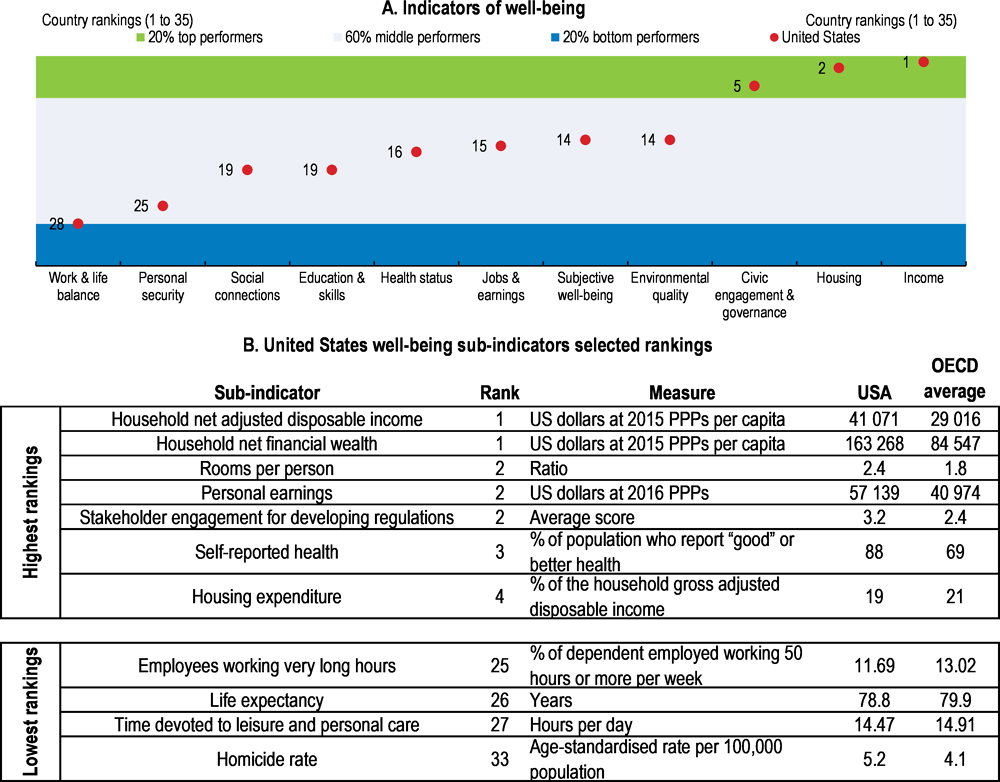

Wellbeing is high and Americans are doing well on average in comparison with residents of other OECD countries (Figure 3), particularly for disposable income and household wealth, long-term unemployment and good housing conditions. On the other hand, housing represents a substantial cost for lower-income families. Work-life balance remains a weakness of the U.S. ranking, particularly when measured by time off from work. The United States also ranks relatively poorly for life expectancy (Box 1.1) and the personal security measure with the third highest age-adjusted homicide rate after Mexico and Latvia.

Figure 3. Well-being rankings

Box 1. How's life expectancy?

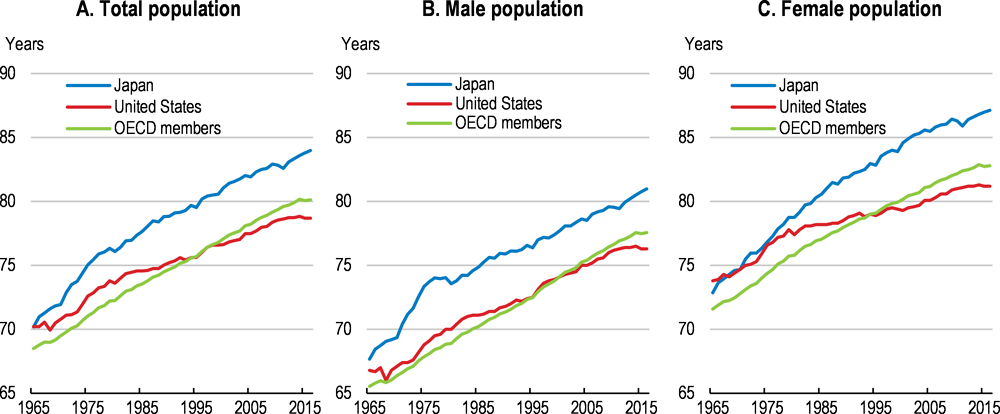

Gains in life expectancy since the 1960s have been moderate in comparison with other OECD countries. Life expectancy at birth is now around 79 years, but that is one year below the OECD average, whereas it was over a year and half above the average in the 1960s (Figure 4). The relative slide in longevity is particularly true for women, who have experienced weaker life expectancy increases since the 1970s. In part, the relative performance is linked to weaker progress in improving child health outcomes (Thakrar et al., 2018[5]). However, life expectancy at later ages has also not improved as much as in many other countries. Absolute, albeit small, declines in life expectancy in 2015 and 2016 continue these developments.

Figure 4. Gains in life expectancy have stalled recently

There is some evidence suggesting that the relatively modest gains in life expectancy is linked to developments in the non-Hispanic white population (Case and Deaton, 2017[6]), particularly amongst women (Gelman and Auerbach, 2016[7]). Relatively sluggish gains in life expectancy appears to be linked to weaker progress in reducing mortality from metabolic diseases and rising drug-related mortality (Masters et al., 2017[8]). Unintentional poisonings rates have increased nine-fold between 1980 and 2015 for non-Hispanic whites (and slightly less for indigenous American Indian or Alaskan Native populations). The opioid epidemic has contributed to sharp upticks in overdose deaths since the beginning of the decade, which was initially concentrated in the white population but is now affecting other demographic groups.

The near-term outlook is for continued solid growth

The near-term outlook is strong. Private consumption remains solid, driven by strong job gains and buttressed by wealth gains from buoyant asset prices and high levels of consumer confidence. Financial conditions generally remain supportive, though they have been tightening more recently. The strengthening of growth in the world economy is supporting export growth.

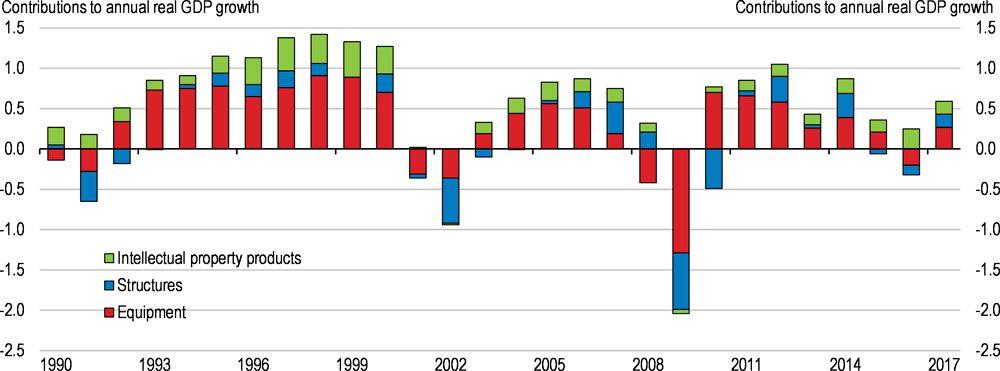

In the business sector, confidence is also robust and business fixed investment is picking up. Business investment began to pick up partly due to oil exploration and drilling activity recovering with the oil price rising, but the recovery now appears more broadly based, particularly for equipment (Figure 5). Residential investment remains relatively subdued though it began to strengthen in late 2017.

After 35 quarters of recovery, the policy mix is supportive. The fiscal stance after the introduction of tax reform and higher spending ceilings for 2018 and 2019 has become expansionary. Monetary policy remains accommodative though this is being reduced as the Federal Reserve raises interest rates and gradually reduces the size of its balance sheet.

Figure 5. Business fixed investment is picking up

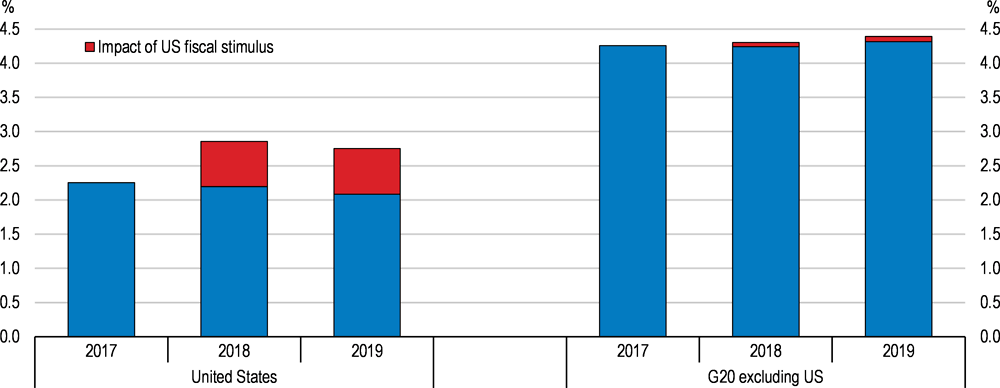

Against this backdrop, economic growth is projected to increase in 2018 and 2019. The newly introduced tax cuts will spur business investment and raising the spending ceilings will lead to a sizeable fiscal impulse, which will give a modest boost to other countries (Figure 6). Federal government fiscal positions over the next few years will weaken and government debt will rise. Stronger wage growth as the labour market tightens further and the impact of tax reforms will raise real disposable income supporting consumption growth. Robust output growth and tighter labour markets will create inflationary pressures, and the Federal Reserve will have to reduce the degree of support accordingly. The supply-side effects of the tax reform will act to offset the inflationary pressures. To the extent that the demand-side effects of the tax reform and raising spending ceilings give a pro-cyclical impulse, macroeconomic policy needs to rebalance with the reduction of monetary policy accommodation.

Figure 6. The fiscal stimulus is boosting growth

Risks to the outlook remain sizeable. A sustained and widespread global upturn could lift activity further, underpinning stronger export growth and investment. Stronger business investment may support a stronger-than-projected pick-up in productivity growth and boost wages further. In these cases, even stronger labour market tightening may stoke inflationary pressures, ultimately requiring the Federal Reserve to tighten more rapidly. On the other hand, there are a number of financial market risks. Elevated leverage ratios in the corporate sector need careful monitoring and action to ensure that these risks are contained. Emerging interest rate differentials between the United States and other major currency areas may contribute to an appreciation of the dollar and possibly increased financial market tensions and turbulence due to unpredictable currency flows. Finally, a rise of trade protectionism could disrupt global supply chains and dent growth (Box 2).

Table 1. Macroeconomic projections

Annual percentage change, volume (2009 prices)

|

|

2014 |

2015 |

2016 |

2017 |

2018 |

2019 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

Current prices (USD billion) |

|||||

|

Gross domestic product (GDP) |

17 428 |

2.9 |

1.5 |

2.3 |

2.9 |

2.8 |

|

Private consumption |

11 864 |

3.6 |

2.7 |

2.8 |

2.5 |

2.2 |

|

Government consumption |

2 563 |

1.3 |

1.0 |

0.1 |

2.2 |

4.3 |

|

Gross fixed capital formation |

3 433 |

3.5 |

0.6 |

3.4 |

4.9 |

4.7 |

|

Housing |

570 |

10.2 |

5.5 |

1.8 |

2.9 |

4.2 |

|

Business |

2 268 |

2.3 |

-0.6 |

4.7 |

6.0 |

5.0 |

|

Government |

594 |

1.6 |

-0.2 |

0.1 |

3.0 |

3.9 |

|

Final domestic demand |

17 859 |

3.3 |

2.1 |

2.5 |

2.9 |

3.0 |

|

Stockbuilding1 |

78 |

0.2 |

-0.4 |

-0.1 |

0.1 |

0.0 |

|

Total domestic demand |

17 937 |

3.5 |

1.7 |

2.4 |

3.0 |

3.0 |

|

Exports of goods and services |

2 374 |

0.4 |

-0.3 |

3.4 |

4.8 |

4.4 |

|

Imports of goods and services |

2 883 |

5.0 |

1.3 |

4.0 |

5.3 |

5.3 |

|

Net exports1 |

- 510 |

-0.8 |

-0.2 |

-0.2 |

-0.2 |

-0.3 |

|

Other indicators (growth rates, unless specified) |

|

|||||

|

Potential GDP |

1.7 |

1.6 |

1.5 |

1.6 |

1.7 |

|

|

Output gap2 |

-1.7 |

-1.8 |

-1.1 |

0.1 |

1.2 |

|

|

Employment |

1.7 |

1.7 |

1.3 |

1.4 |

1.2 |

|

|

Unemployment rate |

5.3 |

4.9 |

4.3 |

3.9 |

3.6 |

|

|

GDP deflator |

1.1 |

1.3 |

1.8 |

2.0 |

2.2 |

|

|

Consumer price index |

0.1 |

1.3 |

2.1 |

2.7 |

2.3 |

|

|

Core consumer prices |

1.3 |

1.8 |

1.5 |

2.0 |

2.2 |

|

|

Household saving ratio, net3 |

6.1 |

4.9 |

3.4 |

3.7 |

4.7 |

|

|

Trade balance4 |

-4.2 |

-4.0 |

-4.2 |

. . |

. . |

|

|

Current account balance4 |

-2.4 |

-2.4 |

-2.4 |

-2.8 |

-3.1 |

|

|

General government fiscal balance4 |

-4.3 |

-5.0 |

-3.6 |

-5.5 |

-6.1 |

|

|

Underlying government primary fiscal balance2 |

-1.0 |

-1.2 |

-1.4 |

-2.4 |

-3.4 |

|

|

General government gross debt 4 |

105.1 |

107.0 |

105.4 |

107.1 |

109.3 |

|

|

General government net debt4 |

80.4 |

81.3 |

80.3 |

82.1 |

84.3 |

|

|

Three-month money market rate, average |

0.5 |

0.9 |

1.3 |

2.3 |

3.2 |

|

|

Ten-year government bond yield, average |

2.1 |

1.8 |

2.3 |

3.1 |

4.1 |

|

|

Memorandum items |

||||||

|

Federal budget surplus/deficit4 |

-2.4 |

-3.2 |

-3.5 |

-4.0 |

-4.6 |

|

|

Federal debt held by the public4 |

73.3 |

77.0 |

76.5 |

78.0 |

79.3 |

1. Contribution to changes in real GDP.

2. As a percentage of potential GDP.

3. As a percentage of household disposable income.

4. As a percentage of GDP.

Source: OECD Economic Outlook 103 database; and Congressional Budget Office.

Box 2. Vulnerabilities to the outlook

|

Vulnerability |

Possible outcome |

|---|---|

|

Financial market difficulties |

Systemically-important financial institutions are creating too-big-to-fail problems for the regulators. |

|

Intensified weather variability and storm activity |

Coastal areas are already heavily exposed to sometimes devastating storm damage. Extreme natural disasters may have long-term negative effects on local economies and require large responses in disaster relief, putting a strain on State and federal fiscal positions. |

|

An intensification of geo-political tensions and threats of terrorist activity |

Heightened insecurity could undermine consumer confidence. Addressing potential threats would likely require substantial public spending and may disrupt economic activity, notably through tighter border controls. |

|

A retreat from internationalism |

While countries share the objective of lowering barriers to trade in goods and services, differences have emerged in strategies, with many countries stressing multilateral frameworks. The recent announcement of trade measures, if unsuccessful in leading to a lowering of trade barriers, may give rise to increased protectionist behavior. Retaliatory actions could lead trade to shrink and jeopardise economic growth. |

|

Political gridlock |

An intensification of past difficulties in forging consensus on the budget and economic policy more broadly may result in gridlock. Risks of default on federal debt or underfunding of essential activities could risk sharp shocks to the economy and financial sector. |

Keeping the expansion on track

Fiscal policy has generally been less expansionary than monetary policy in recent years, but that is changing as fiscal policy has begun to relax while monetary policy is removing accommodation gradually. The changing stances should help act against some of the high valuations seen in the financial markets.

Ensuring fiscal sustainability

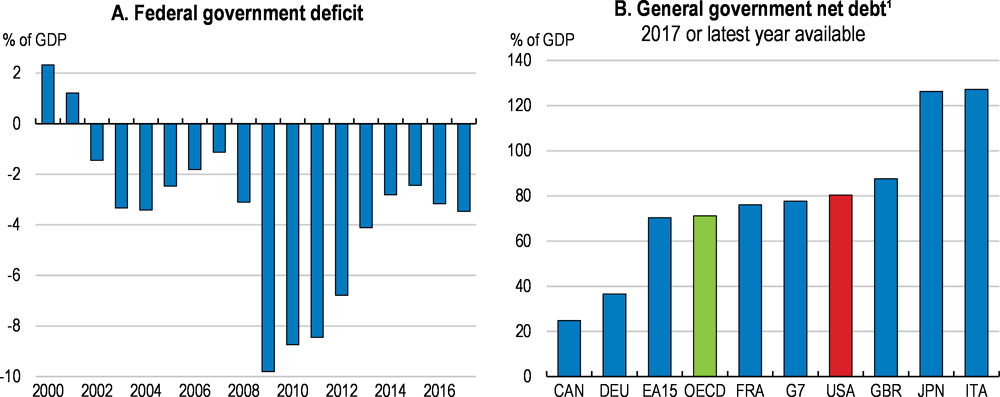

Reflecting the gravity of the financial crisis, general government net debt-to-GDP (which includes State and local government debt) remains high in comparison with other OECD countries (Figure 7). Fiscal policy did gradually rein in deficits until 2014. Subsequently, the federal government deficit relative to GDP has remained relatively stable.

Fiscal policy relaxed substantially in early 2018. Tax reform combined with Congress raising spending ceilings in 2018 and 2019 provides a considerable fiscal stimulus of around 1% of GDP in both years and gives a sizeable short-term boost to growth. The official scoring of the Joint Committee on Taxation see the effects of the bill reducing revenues with a cumulative cost over the next decade of a little over $1,000 billion. Even with macroeconomic feedbacks boosting tax revenue, the tax reform will contribute to a higher deficit. As such, federal debt held by the public would rise (Figure 8). The economic assumptions underlying the Administration's budget projections see growth being sustained at around 3% for the next ten years, which would begin to stabilise federal government debt (OMB, 2018[5]).

Figure 7. Deficits have begun to rise and debt levels are quite high

1. General government shows the consolidated (i.e. with intra-government amounts netted out) accounts for all levels of government (central plus State/local) based on OECD national accounts. This measure differs from the federal debt held by the public, which was 76.5% of GDP for the 2017 fiscal year.

Source: Congressional Budget Office; and OECD Analytical Database.

In the longer-run, pressures are emerging from rising mandatory spending. Between 2018 and 2028 spending on health (primarily Medicare, Medicaid) is expected to rise by 1.3 percentage point of GDP and Social Security by 1.1 percentage point of GDP. These pressures are offset partially by expected declines in other areas of spending, mainly discretionary spending. Health spending has been affected by successfully expanding population coverage, notwithstanding underlying healthcare price inflation slowing. Further efforts to rein in spending growth, such as the recent initiative to reform pharmaceutical pricing, are advisable and actions to relax regulations that raise drug prices for Americans will help in this regard (CEA, 2018[6]).

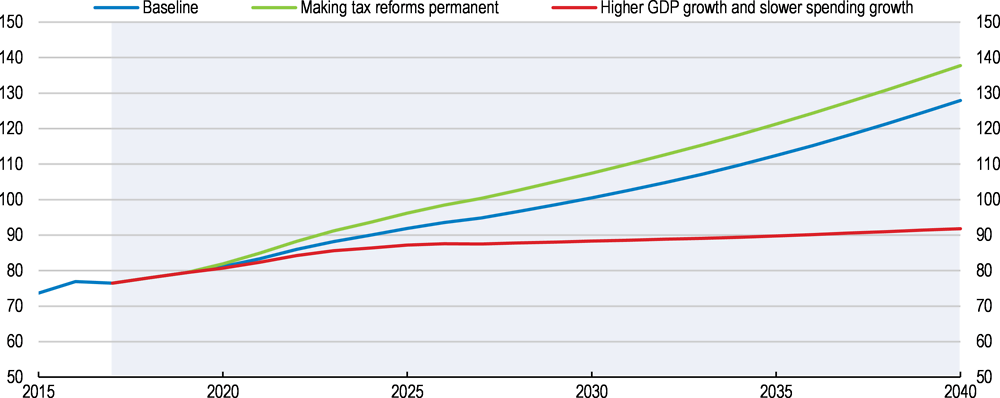

Figure 8. Higher growth is needed to stabilise debt levels

Federal debt held by the public, % of GDP, fiscal years

Note: The Baseline scenario is the CBO's projection from April 2018, which is augmented beyond 2027 using the assumptions from the 2017 long-term projections. The making reforms permanent scenario reduces the tax share aby 0.8 percent of GDP relative to the baseline. The scenario raises the spending ceilings for 2018 and 2019 by around $150 billion in each year. These reforms are assumed to raise real GDP growth to 3% in both 2018 and 2019. The path thereafter takes the Barro and Furman (2018) calculations that the tax reforms will raise annual growth by 0.12 percentage points over the rest of the scenario with respect to the CBO GDP projection. The higher output growth and slower spending growth scenario builds on the previous scenario, raising the average growth rate over the scenario to 3.4% and constraining the rise in non-interest spending to 1.6% of GDP over the simulation.

Source: OECD calculations.

The growth effects of the fiscal stimulus are expected to boost revenues and the taxation on the deemed repatriation of foreign profits will give a temporary boost to revenues. In addition, the tax reform may attract inward investment and reduce corporate inversions and outward investment. However, if revenue and spending growth fail to attain the rates underpinning the Administration's budget forecasts, action will be needed to ensure fiscal sustainability. The policy recommendations made in this Survey would also entail additional fiscal costs (Box 3). The CBO has identified opportunities to reduce spending by increasing efficiency (CBO, 2016[7]). If additional revenue is required, moving to sources that are more growth friendly, such as consumption taxes, or acting against environmental externalities, would be preferable.

Box 3. Quantifying fiscal policy recommendations

The following OECD estimates roughly quantify the fiscal impact of selected recommendations. The estimated fiscal effects abstract from short-term behavioural responses that could be induced by the given policy change.

Table 2. Illustrative fiscal impact of recommended reforms

|

Policy |

Measure |

Impact on the fiscal balance, % of GDP |

|---|---|---|

|

EITC |

Expand the earned income tax credit to the childless poor with weak labour force attachment (permanent increase) |

0.03% |

|

Infrastructure investments |

Boost investment in infrastructure, including mass transit (temporary increase over 10 years) |

0.10% |

|

Active labour market policies |

Increase spending on job placement services (permanent increase) |

0.02% |

|

Treatment of opioids |

Expand access to life-saving drugs and support medically assisted treatments for addiction(temporary increase) |

0.02% - 0.10% |

|

Tax reform |

Make expensing permanent |

0.2% |

|

Possible offsetting measures |

||

|

Subsidies |

Reduce crop insurance subsidies |

0.01% |

|

Fees |

Raise Fannie Mae's and Freddie Mac's guarantee fees and decrease their eligible loan limits |

0.01% |

|

Indexation |

Use an alternative measure of inflation to index social security and other mandatory programmes |

0.09% |

|

Tax |

Increase excise tax on motor fuels by 35 cents and index for inflation |

0.24% |

|

Tax |

Increase the excise tax on cigarettes by 50 cents per pack |

0.02% |

Normalising monetary policy

After almost 10 years of exceptional support, monetary policy remains supportive, though is in the process of normalising. The Federal Reserve began to raise policy rates in December 2015 and started to reduce slowly the size of its balance sheet in October 2017. The Federal Reserve is projected to continue to remove policy accommodation at a gradual pace as the labour market tightens further and stronger wage growth becomes more apparent. As monetary policy normalises, care is needed to manage some areas of risk, such as in the corporate debt market and elevated asset prices.

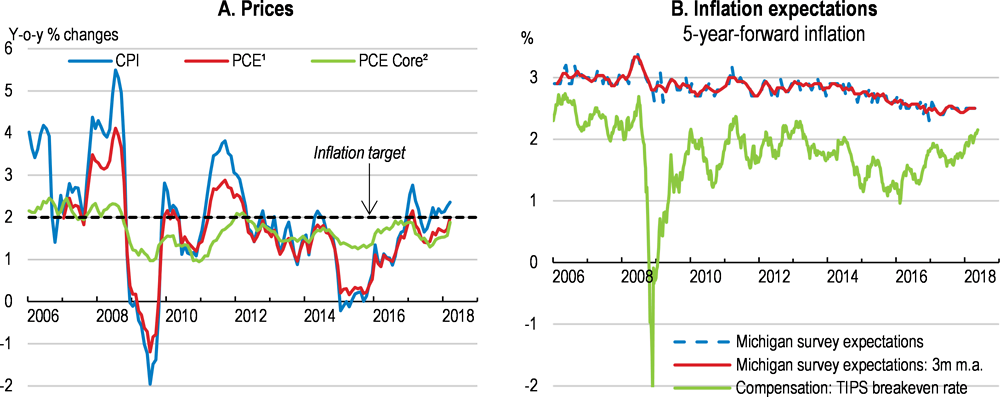

Even with the unemployment rate dipping below what observers previously estimated was the natural rate, at which point inflationary pressures should begin to mount, price inflation has run below target. In part, this outcome appears to reflect a number of idiosyncratic and transitory shocks, one-off factors such as reforms to mobile phone pricing plans. In OECD empirical estimates of the link between unemployment and inflation, the impact of the unemployment rate and the estimated natural rate on inflation is estimated to be relatively weak, even compared to other OECD countries. However, the unemployment gap does have an influence on core inflation (Rusticelli, Turner and Cavalleri, 2015[1]). In the estimates of factors determining inflation, expectations of future inflation play an important role in explaining developments. In recent years, measures of inflation expectations have remained relatively steady and measures of inflation compensation have risen somewhat but remain low in comparison with historical norms (Figure 9).

Figure 9. Inflation is returning to target but expectations remain lower than the past

1. Personal Consumption Expenditures price index.

2. Personal Consumption Expenditures excluding food and energy price index.

Source: OECD Analytical Database and Thomson Reuters.

The Federal Reserve faces challenges in managing raising interest rates as inflation returns to target. Moving too quickly could further entrench weak inflation expectations, making the attainment of the target more difficult if it is perceived as a ceiling rather than a symmetrical target over the medium term. Furthermore, critics have called for more aggressive interest rate hikes over the past few years on the basis of the labour market tightness. Following that course would have choked off payroll growth and put a halt to the rise in the employment-to-population ratio. As the ratio of employment to population remains below past norms an argument can be made that more people can be drawn back into the labour force and employment. However, sustained low interest rates could lead inflation to move undesirably higher and may exacerbate existing financial distortions requiring attention from prudential regulation. In particular, leverage in the corporate sector has increased and in some vulnerable firms it is close to historic highs.

As the normalisation of monetary policy proceeds, there has been discussion about reforming the monetary policy framework. Part of the backdrop has been providing monetary room to act against future shocks. Expectations of long-run policy interest rates are currently only around 3%, whereas in the past rates of around 6% were common. Given that policy interest rates have typically been lowered by 5 percentage points during a downturn, this implies that the Federal Reserve will have limited room to react to future shocks. Proposals addressing this include raising the inflation target from its current 2%. An alternative approach is to switch the monetary policy target temporarily to a price-level target during harsh downturns (Bernanke, 2017[8]). In essence, this approach would strengthen forward guidance by buttressing commitment to meeting the medium-term inflation target more symmetrically.

Addressing financial market risks

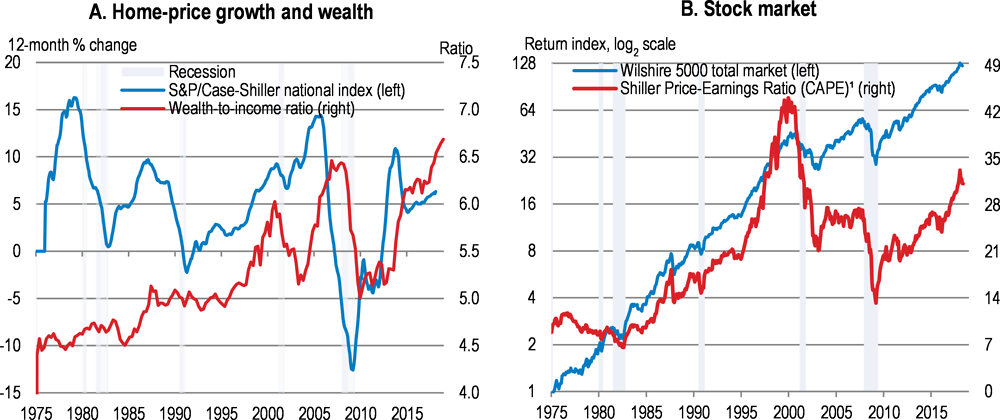

Partly as a consequence of sustained very low interest rates, asset prices are elevated and risks have built up in a number of areas, such as the corporate sector (Figure 10). Cyclically-adjusted price earnings ratios are now at levels not seen since the financial market crisis. This has led to increasing talk about overvaluation and bubbles, though currently these do not appear to be a major risk to the expansion (Box 1.4).

Figure 10. Asset prices are elevated

On the other hand, some risks appear less pronounced or the transmission is likely to be more muted in current conditions. For example, the recovery of asset prices combined with households on aggregate not building up consumer credit too rapidly has led to household balance sheets improving significantly. The ratio of household net worth relative to disposable income reached 6.7 years in 2017, a ratio not seen since 1947. On the flip side, the rise in asset prices may mean that non-homeowners face greater difficulties in purchasing a house. In addition, financial stability is protected by the capital buffers held by financial firms and regulation and measures of risk premia are declining as interest rates are rising.

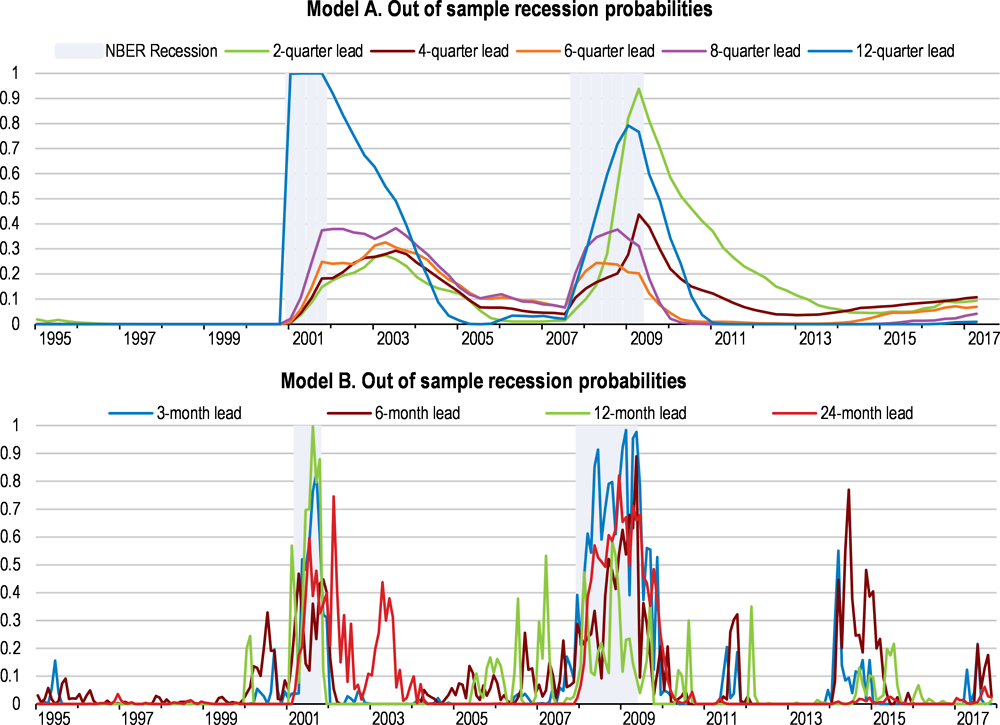

Box 4. Recession probabilities

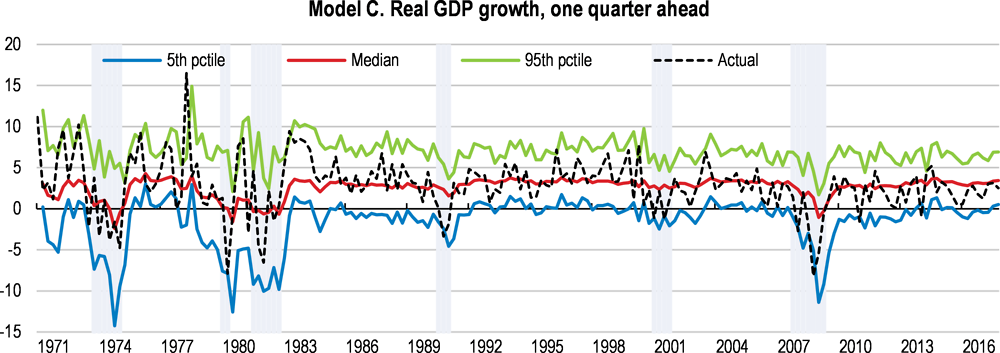

While risks are present, they do not seem to be threatening the outlook (Azzopardi and Sutherland, 2018[13]). Recession probabilities have been rising slightly recently using data from the OECD resilience database. These data consist of variables that have proven to be associated with past cyclical downturns across OECD economies (Hermansen et al., 2016[14]). Several models were estimated using principal components of the resilience data to assess the probabilities of recessions at different horizons using quarterly data (Figure 11, Panel A). The recent rises in recession probabilities remain below previous downturns.

Higher-frequency data and a data set more tailored to the United States may give better warnings of emerging risks. Using a wide set of monthly indicators used in previous studies (Hatzius et al., 2010[15]), estimated recession probabilities again show some sign of a recent uptick but they remain inconclusive and not indicative of a mounting threat to the expansion (Figure 11, Panel B). A complementary approach exploring the possibility of a downturn using quintile regressions can capture increasing downside risks (Adrian, Boyarchenko and Giannone, 2017[16]). Again the latest estimation using this approach is inconclusive (Figure 11, Panel C).

Figure 11. Early warning indicators

Model A: Probability that the U.S economy is in recession based on real-time quarterly data.

Model B: Probability that the U.S economy is in recession based on real-time monthly data.

Model C: Full sample real GDP growth prediction. Quantile regression of 1-quarter lead GDP growth against current GDP growth and NFCI indicator (National Financial Conditions Index).

Shaded regions: dates of recessions as determined by NBER

Source: OECD calculations.

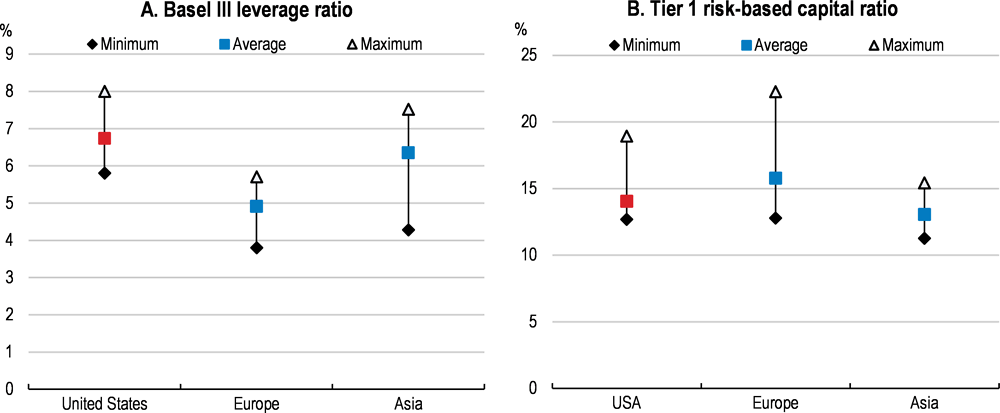

Overall, the banking system, in part as a consequence of the reforms implemented under the Dodd-Frank Act, seems healthy. Leverage in the financial sector is at historically low levels. Large banks overall have sufficient capital levels to resist a severe crisis without disrupting credit provision (Figure 12). Indeed, regulatory capital at large banks is now at multi-decade highs. Tier 1 common equity capital more than doubled from early 2009 to 2017. Annual stress-testing has contributed to improvements in capital and risk management procedures amongst participating banks.

Figure 12. Banks are better able to withstand shocks

Note: The Basel III leverage ratio is a non-risk-weighted leverage ratio also taking into account off balance sheet exposure. The minimum requirement is 3%. Tier 1 risk-based capital ratio is the relationship between a bank's core equity capital and total risk-weighted assets.

Source: Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC): Global Capital Index of capitalization ratios for Global Systemically Important Banks (as of December 31, 2017).

Vulnerabilities associated with liquidity and maturity transformation appear to have decreased. Large banks have cut their reliance on short-term wholesale funding essentially in half and hold more high-quality liquid assets. In addition, the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) has reformed money market mutual fund regulations. The market will need to be monitored to ensure that substitutes for the money market mutual funds do not emerge creating similar risks.

On the other hand, vulnerabilities in the non-banking financial sector, or shadow banking, could ultimately undermine banks that are heavily connected to non-banks through derivatives and other financial instruments. For example, credit risk appears elevated in nonfinancial corporate debt. In addition, tools for the orderly resolution of systemic non-bank financial firms, such as central counterparties or insurance companies, are not well developed. The treatment of derivatives obligations of a failing financial firm presents a conundrum for policymakers seeking to balance contagion and run risks against moral hazard concerns.

Reform initiatives

A legacy of the financial crisis is that the largest banking groups became larger. Financial supervision has strengthened prudential regulation for these institutions. However, such a complex piece of legislation as Dodd-Frank creates unintended side-effects and efforts to address unwarranted regulatory burdens are appropriate. In particular, concern has been expressed about the regulatory burden on small community banks. Nonetheless, efforts to reduce regulatory burdens should be mindful not to re-introduce vulnerabilities. Any financial market reform, particularly those affecting larger financial institutions, needs to be cautious. The ongoing process launched by the Financial Stability Board to evaluate post-crisis regulatory reforms provides a suitable framework to assess prudential regulation currently in place and a timetable to move ahead with further reforms that are deemed appropriate.

Despite stronger resilience associated with improved regulation, there is room to limit even more possibilities of systemic risk associated with the failure of the largest financial institutions. Notably, the resolution process under either U.S. bankruptcy law or a special resolution authority has potential weaknesses for handling global systemically important bank (G-SIB) failures. Given their importance and the risks of too-big-to-fail an important question is whether current capital and liquidity regiments are sufficient. A number of recent studies suggest that optimal capital levels are somewhat higher than those currently observed in the United States, though uncertainties about these estimates are large (Firestone, Lorenc and Ranish, 2017[9]; The Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis, 2017[10])

The government sponsored enterprises (GSEs) Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac were subject to severe stress during the 2008 financial crisis and had to be put under temporary conservatorship and recapitalised. While some reforms were introduced to bolster risk sharing with the mortgage originators when they purchase loans and to impose tighter prudential standards for the loans they can purchase, the GSEs remain essentially unreformed. In addition, the Federal Housing Administration creates another set of liabilities from their loan portfolio. As a result, the federal government still plays a leading role in housing finance as the overwhelming majority of new mortgages are issued with government backing through these agencies. This continues to entail very large risks both in terms of contingent liabilities and financial stability (Powell, 2017[11]).

The GSEs have not been subject to the tighter prudential requirements imposed on large banks, notably higher equity capital requirements, rigorous annual stress tests, and the mandatory filing of resolution plans. The rebound of the housing market and fall in mortgage loan defaults helped the GSEs return to profitability and pay the Treasury large dividends. However, the tax reform enacted in late-2017 will put once again the GSEs under financial pressure because the reduction in the corporate tax rate will trigger a large write-down on their tax-deferred assets. In order to normalize housing finance, the last Economic Survey recommended leaving the securitisation of mortgages to the private sector. This would entail privatising the GSEs, cutting off their access to preferential lending facilities with the federal government, subjecting them to the same regulation and supervision as other issuers of mortgage-backed securities, and dividing these entities into smaller companies that are not too big to fail. While promoting affordable housing is a key role played by the GSEs, this should use more targeted instruments, aimed at low-income households, and include the funding of rental properties, rather than homeownership. This would bring the US home mortgage market in line with the practices of other OECD countries. The Senate is preparing a bill that goes in this direction.

A final area where reform initiatives are warranted is to support regulatory experimentation for new financial technology initiatives. These technologies may offer credit to groups who have traditionally found access difficult (Fareed et al., 2018[12]). There are large differences in access to banking services between metropolitan areas and more isolated locations, largely reflecting differences in population densities. Other factors leading to individuals not using banking services are insufficient funds to save, trust in banks and the fees banks charge. Individuals without traditional banking relationships are not necessarily cut off from credit as FinTech is creating opportunities as well as challenges (Box 5).

Box 5. Blockchain technologies and financial stability

Innovations in the financial sector using new technologies "FinTech" are creating new opportunities that may transform the sector. For example, the development of blockchain, or distributed ledger technology, promises to introduce considerable efficiency gains by amongst other benefits allowing transactions to occur without the need for a trusted intermediary. Automation of services can cut the needs for back-office personnel. Furthermore, traditional banks will face threats to their existing business models as new companies will potentially attract clients to faster and cheaper services.

Yet, while FinTech will challenge traditional financial institutions, it may also create new markets for financial services or broaden existing ones. Innovations create new possibilities for individuals who have hitherto lacked access to traditional financial institutions, thereby enhancing financial inclusion. For example, online lenders make use of machine learning and big data to evaluate credit risk for personal unsecured loans rather than using existing standardised credit scores (Jagtiani and Lemieux, 2017[21]). In this light, innovation can help reduce barriers to access credit for groups - either individuals or firms – that have had limited access in the past.

The development of these potentially disruptive technologies raises concerns about privacy. Recent cyber thefts also underline issues surrounding digital security. Innovative uses of artificial intelligence to financial services also create challenges for the regulators in assessing risk.

Regulators will need to find ways to ensure a level playing field between traditional financial institutions and the new entrants. To the extent that increasing returns to scale are important and that firms may want to remain outside the regulatory environment (and thus operate as shadow banks) the task of the regulator will be complicated. Regulators will need to underwrite trust in the financial system in the face of an increasingly fissured financial sector. Against this background, other countries are preparing the regulatory framework cautiously. The regulatory sandbox in the United Kingdom (allowing businesses to test innovative products, services or delivery mechanisms in a controlled regulatory environment) is one approach to facilitate innovation while developing the framework to manage risks when these technologies are ready to challenge existing financial institutions. A sandbox should encourage innovation with the ultimate aim of better financial services for consumers.

Table 3. Past OECD recommendations on monetary and financial policy

|

Recommendation |

Actions taken since the 2016 Survey |

|---|---|

|

Raise policy interest rates at a pace that gradually tightens financial conditions so as not to jeopardise the recovery and to promote a return of inflation to the Fed’s target. |

Interest rates have been increased gradually and inflation is returning to target |

|

Continue to implement Dodd Frank and Basel III requirements. |

The financial regulators have implemented Dodd Frank and Basel III requirements. |

Sustaining higher growth rates

Sustaining the expansion will require actions to offset slowing employment growth and to boost productivity. Sluggish productivity growth has been a consequence of various factors such as limited capital deepening and onerous regulations. While employment gains have been robust, a slowdown of employment gains due to ageing and slowing labour force growth is projected and also as people with relatively strong attachment have already returned to the labour market.

Deregulation and boosting investment to support productivity

Boosting productivity through polices that improve the business environment would also help to sustain the recovery. This should include enhancing competition, freeing up resource allocation and raising investment (including in infrastructure). The Administration has launched an initiative to reduce the regulatory burden and government agencies are now highlighting and proposing to remove cumbersome regulation. Progress is complicated by the interaction of Federal, State and local regulations.

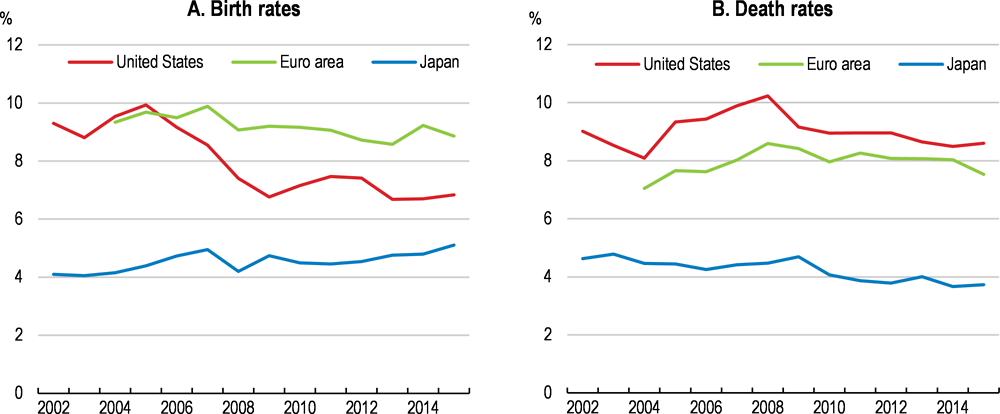

Improving the business environment by reducing the regulatory burden could help reanimate firm creation and their subsequent growth. This is not only related to slower start-up rates (as well as exit rates), which have declined toward the OECD average (Figure 13). Firms and sectors have become less responsive to productivity shocks, whereas in the past a firm would tend to grow rapidly after a boost to productivity (Decker et al., 2018[13]). As discussed in the last Economic Survey, this contributes to sluggish productivity growth.

Figure 13. Business dynamism has slowed

Notes: Number of enterprise births and deaths in year t over number of active enterprises in year t. Data for the United States are estimated in 2013-15, using separate data from the US Census Bureau. The Euro Area estimates are an unweighted average of birth and death rates in member states.

Source: OECD Economic Outlook, Volume 2017 Issue 2.

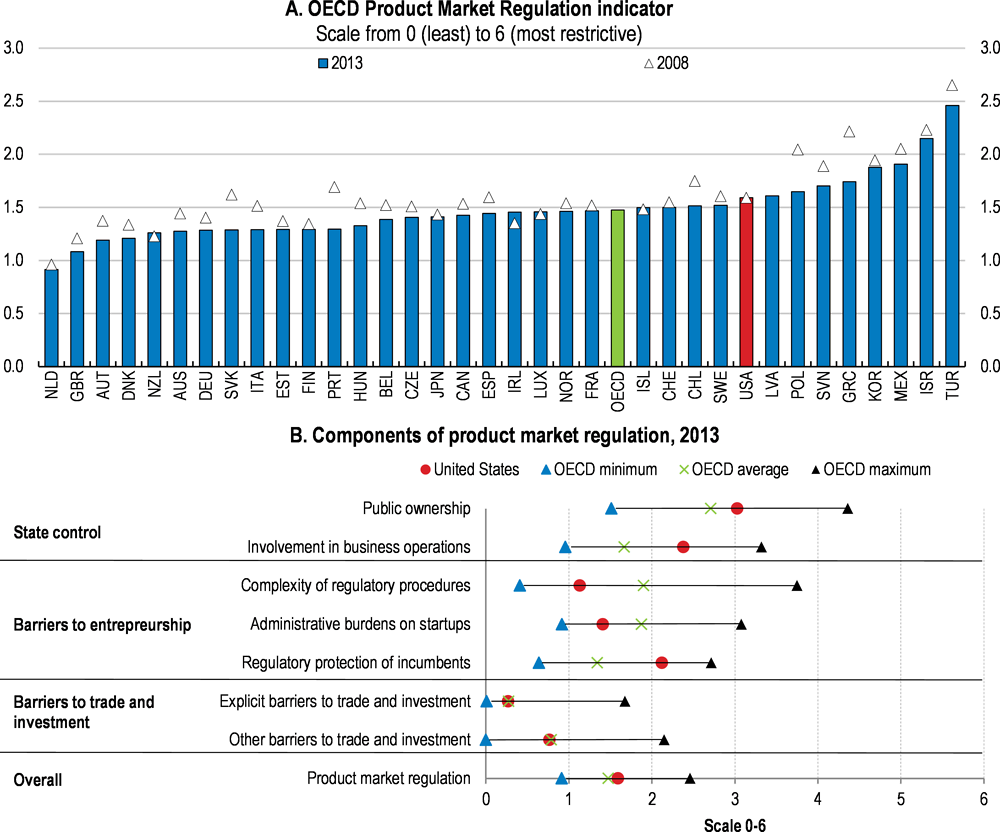

In several domains of product market regulation, the United States is amongst the less restrictive in the OECD. Measures of barriers to trade and investment are low and administrative burdens on start-ups are light. However, the overall measure is around average for the OECD (Figure 14). Regulatory protection of incumbents is high, almost completely due to exclusions or exemptions from anti-trust law for publicly-controlled firms or undertakings. Removing such exemptions and exclusions for abuse of dominance and horizontal cartels or vertical restraints would level the playing field for existing firms and new entrants. Other major areas where regulations are more restrictive than on average elsewhere in the OECD include direct control over business enterprises (either where the government has special voting rights in a private enterprise or restraints on sales of stakes in publicly-controlled firms) and governance of state-owned enterprises, which either insulate them from market discipline or influence their management. These arise due to State-level ownership of firms in the energy and transportation sectors (which in the indicators reflects the situation in New York State and may not be representative for the whole country). OECD analysis of the impact of structural reforms suggests that reforms in these areas could improve performance and boost productivity (Égert and Gal, 2017[14]) (Box 6).

Figure 14. Product market regulation is around average

Box 6. Quantification of structural reforms

Reforms that are proposed in the Survey are quantified in the table below. Some of the estimates reported are based on empirical relationships between past structural reforms and productivity, employment and investment. These relationships allow the potential impact of some structural reforms to be gauged. These estimates assume swift and full implementation and are based on cross-country estimates, not reflecting the particular institutional settings of the United States. This includes how representative changes in policies under the control of the States are for the whole country. As such, these estimates are illustrative.

Table 4. Potential impact of structural reforms on per capita GDP

|

Reform |

10 year effect |

Long-run effect |

|---|---|---|

|

Product market Regulations |

|

|

|

Governance of state owned enterprises |

0.7% |

1.4% |

|

Direct Control over business enterprises |

0.3% |

0.7% |

|

Labour market policies |

||

|

Enhancing job placement for workers |

0.1% |

0.2% |

|

Tax reform |

||

|

Making corporate tax reforms permanent |

0.8% |

2.2% |

|

Infrastructure spending |

||

|

Raising infrastructure spending |

0.9% -2.0% |

Notes: The policy changes that are assumed for the scenarios in the table are:

1. Reducing direct control over business enterprises to the top quartile of OECD economies; 2. Reducing direct control over business enterprises to the top quartile of OECD economies; 3. Enhance job placement for workers involves raising spending on active labour market programmes to help workers back into employment equivalent to 0.02% of GDP;

2. The tax reform scenario is based on making the reforms to the corporate tax reform permanent, such as full expensing for investment;

3. The infrastructure spending scenario is based on the assumptions used in the Economic Report of the President.

Source: OECD calculations based on (Égert and Gal, 2017[14]), (Barro and Furman, 2018[15]), (CEA, 2018[4]).

On the basis of other cross-country empirical relationships moving to best practice by reducing the costs of closing a business could potentially raise the level of productivity by around one percentage point in the long run (Adalet McGowan and Andrews, 2017[24]).

The spread of occupational licensing at the State and local level creates another set of regulations that can inhibit business dynamism. In 2017, around one quarter of workers possessed certification or a licence. Occupational licensing is often based on public interest grounds, but this is not always the case. Furthermore, the local specificity of licensing can effectively create a barrier to entry and inhibit the ability of workers to move to employment opportunities elsewhere as they may have to incur significant costs in acquiring new licences. Empirical evidence suggests that there are means to protect the public interest while easing the deadweight losses they impose on the economy. For example, mutual recognition of licenses by different States, as encouraged by the Administration in its recent infrastructure initiative, appears to promote inter-State migration (Abdul Ghani, 2018[16]).

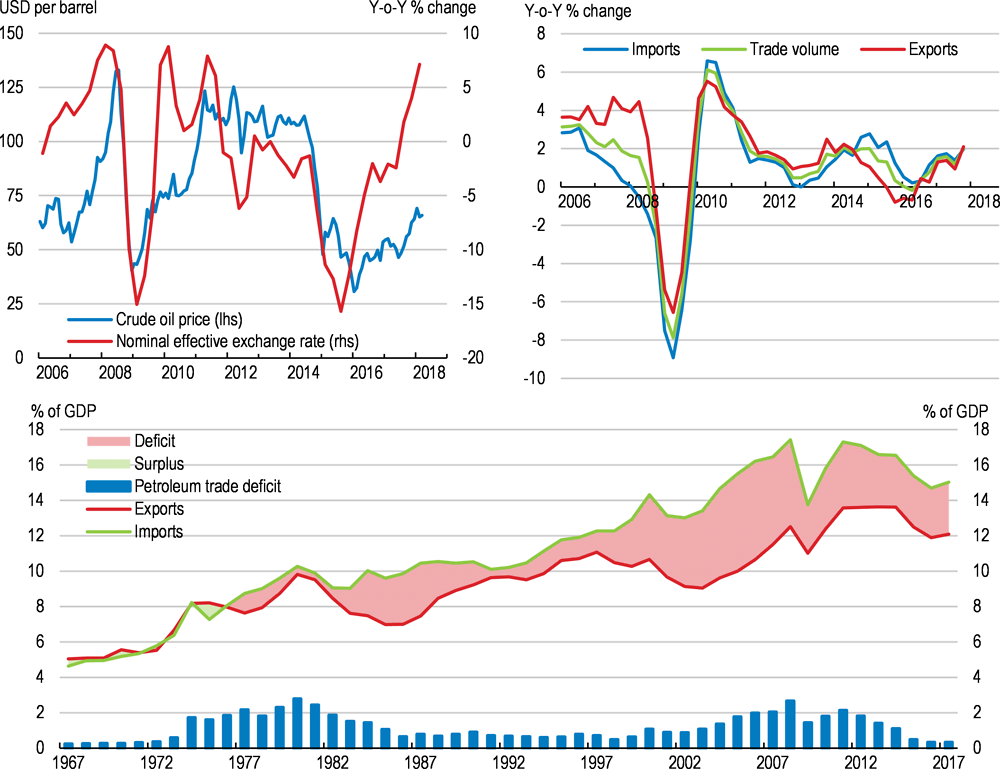

International trade

Trade volumes have grown relatively modestly since the great recession, reflecting weaker growth rates in major trading partners as well as exchange rate and oil price developments. The development of hydraulic fracturing technologies in oil production has boosted domestic production in recent years and brought the trade balance on petroleum products close to balance as exports have increased strongly and imports have declined (Figure 15). Around two-thirds of world trade involves global value chains, with products crossing borders during production. The expansion of global value chains has brought large benefits to consumers and workers through economies of scale, comparative advantages, technology spillovers, and job creation – including indirect job gains in the services sector (OECD, 2016[17]).

Figure 15. Trade growth has been sluggish since the crisis

The United States' global value chains are strong with NAFTA partners and have been strengthening over time (Escobar, 2018[18]). These value chains are particularly important in sectors such automobiles, which are organised around hubs (Criscuolo and Timmis, 2018[19]). Global value chain linkages are also strong with some Asian countries. When measured by trade in value added the importance of Canada, Mexico and China diminish in comparison with gross exports. This arises due to large shares of US value-added being embodied in their exports to other countries. The trade deficit in manufacturing for the United States shrinks by 60% when considering value added, due to large contributions of services to trade.

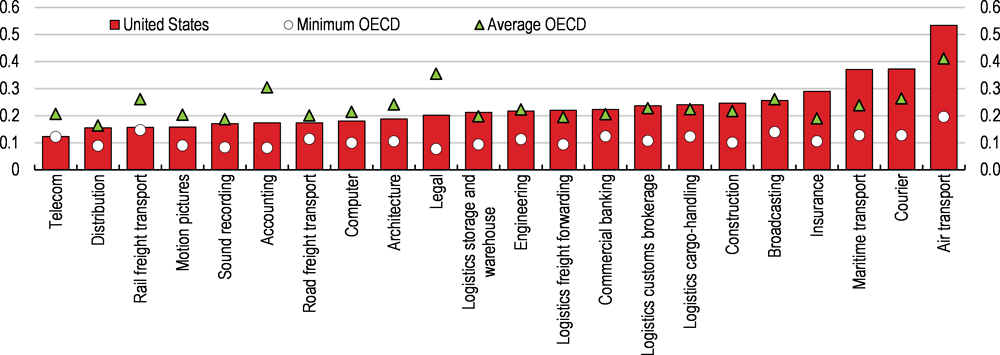

Reducing barriers to trade in goods has outstripped progress in reducing barriers to trade in services. Measures of trade restrictions in services are relatively high in the United States (Figure 15). The United States would benefit more given that the composition of exports in many advanced countries has shifted towards a greater role for services. In the United States services already account for over half of valued added exported. Countries tend to specialise more in tradable services when high-skilled labour is relatively plentiful and digital infrastructure is more developed. As the U.S. economy has moved towards greater importance of services, knowledge-based capital has risen in importance, including in international trade (Box 8). Against this background, making further progress multilaterally in reducing trade impediments would benefit the United States and the world economy (Box 7).

Figure 16. Trade in services is not very open

The indices take values between zero and one (the most restrictive)¹, 2017.

1. The index includes regulatory transparency, barriers to competition, other discriminatory measures, restrictions on movement of people and restrictions on foreign entry.

Source: OECD Services Trade Restrictiveness Index (STRI).

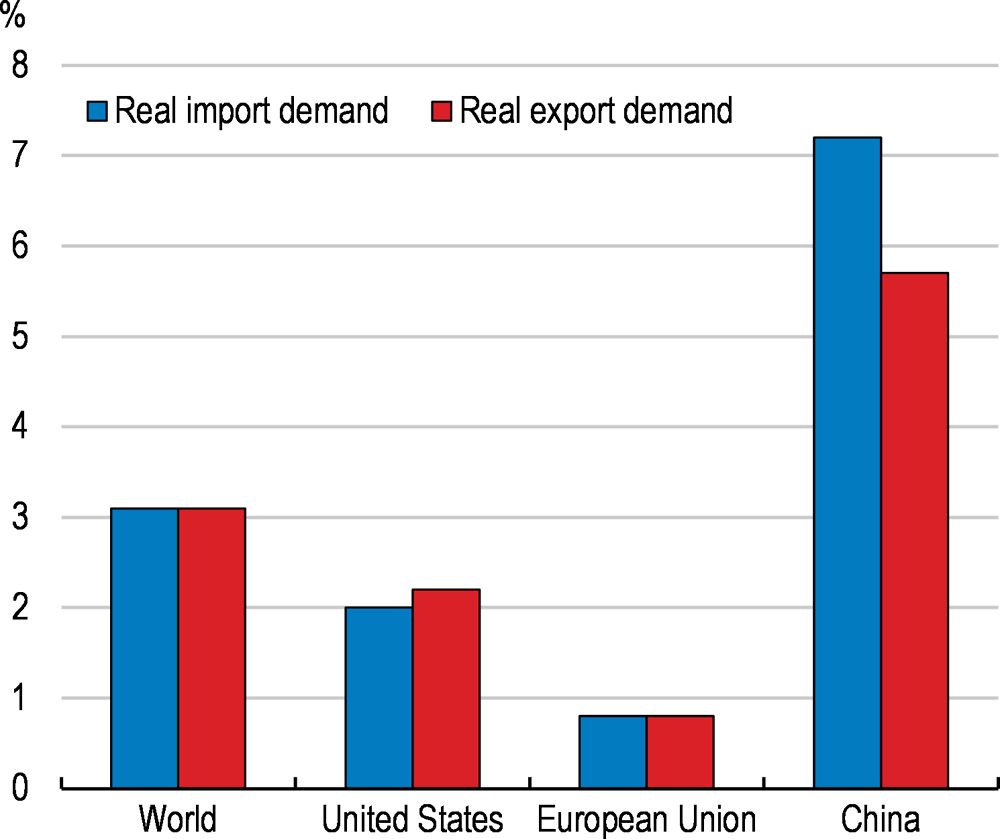

Box 7. Reducing barriers to trade would boost the global economy

The effects of multilateral tariff liberalisation are explored in a scenario where tariffs were reduced to the lowest level applied across G20 economies for each sector examined using the OECD METRO model (2015a). The majority of sectors have the minimum rate of 0%, with other foods (1%) and textiles (2%) being the exceptions. If such a reduction were adopted, (which is equivalent to a weighted average reduction of 2% for all economies) global trade would expand by more than 3% (Figure 17). China experiences the largest increases in trade, having relatively higher initial tariffs. Its imports (where the relatively greater benefits are found) increase slightly more than exports. Both the US and EU experience an increase as well, with the US experiencing greater increases in trade.

Figure 17. Increase in trade from tariff reductions

Note: Simulation results on trade are from the OECD’s METRO model, a global computable general equilibrium model of trade with a high degree of sectoral disaggregation. The increase in trade is the medium term effects

Source: Arriola and Stone, (2018 [forthcoming]).

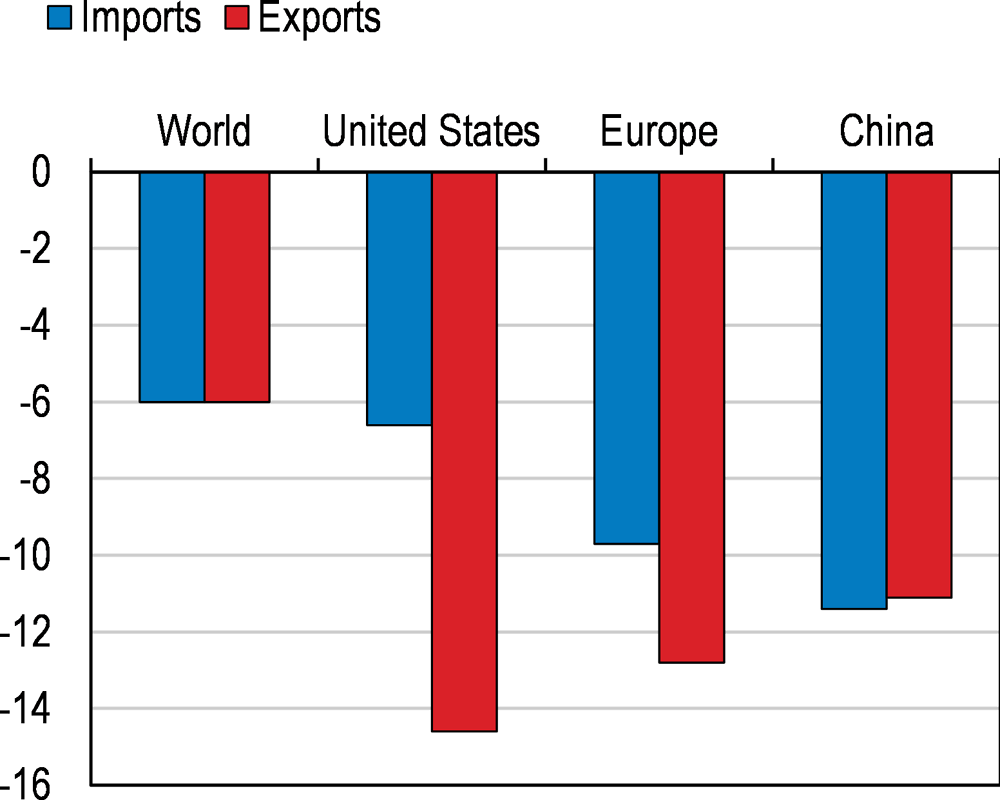

The benefits from multilateral reductions in trade barriers can be contrasted with the trade-reducing effects of implementing wide-ranging new trade restrictions. In this hypothetical scenario China, Europe and the United States are assumed to increase trade costs against all partners on all goods (but not services) by 10 percentage points. The effects would have a major adverse impact on trade, with those countries that imposed new trade barriers being the most severely affected (Figure 18).

While the change in protection shown here is illustrative, changes of a different magnitude might be expected to have correspondingly smaller or larger macroeconomic effects, although some likely adverse effects may not be captured here. For example, retaliatory actions could generate additional adverse effects on trade from disruption to global value chains, and the uncertainty introduced by protectionist trade policies would likely result in a slowdown of investment, leading to further drops in incomes and productivity.

Figure 18. The effect of increased trade costs on trade

Note: Effect of a rise in trade protection by the United States, China and European Union which raises trade costs by 10 percentage points. Europe includes the European Union, Switzerland and Norway. Trade results for Europe exclude intra-European trade. Simulation results on trade are from the OECD’s METRO model, a global computable general equilibrium model of trade with a high degree of sectoral disaggregation (OECD 2015d).

Source: OECD Economic Outlook, November 2016, Box 1.3.

Beyond tariffs, important policy levers for trade liberalisation include lifting actionable non-tariff measures and reducing services trade costs. Given that multilateral and regional liberalisation has proceeded at a slower pace for services and non-tariff measures than for tariffs over the past decades, the scope for gains from liberalising trade in these areas is expected to be large. Besides pure market access effects, regulatory reforms that reduce related trade costs would also be expected to result in significant competition-enhancing effects and productivity gains in the economies concerned – both in the sectors being liberalised and in downstream sectors in local and global value chains.

Box 8. Knowledge-based capital is increasingly important for international trade

Business investment in knowledge-based capital is linked to growth and higher productivity (OECD, 2015[30]). That link exists for two main reasons. First, in contrast to physical capital, once the initial cost of developing some types of knowledge is borne, the cost is not re-incurred when the knowledge is used again (in other words, knowledge-based capital is “non-rivalrous”). That feature can create substantial economies of scale in production. Second, investments create knowledge spillovers, which allow the benefits from an original investment to reverberate throughout multiple sectors of an economy. Studies have shown that business investment in knowledge-based capital contributes one-fifth of average labour productivity growth in the European Union and the United States.

Knowledge-based capital is becoming a more tradable asset that is taking over the core of the global economy. Most of the value in technology products and medicines is not in the physical materials with which those goods are made, but in the continuum of activities around the research, testing, and innovation required to develop them. Even manufacturing staples like apparel can include substantial knowledge-based capital, such as the design, in their value. As globalisation continues, the knowledge based capital inherent in those products is reaching, as well as emanating from, more and more markets. In countries such as Australia, Canada, Japan, the United Kingdom and the United States, the significance of investment in knowledge-based capital relative to investment in tangible capital has been steadily increasing over time.

While intellectual property’s prominence has been growing, a number of developments have been significantly changing the way intellectual property is created, disseminated, appropriated and used. Some of those developments, such as advances in digital technologies, have helped to make information more abundant, easier to access, and easier to store and copy. Those developments have also made it easier to obtain and distribute intellectual property illegally. That accentuates the fact that intellectual property rights are now more important than ever, as it is in everyone’s long-term interest for stakeholders who create knowledge and artistic works to have well-defined, enforceable rights to exclude third parties from appropriating their ideas or the expression of their ideas without permission.

Competition policy

Attention is needed regarding competition policy. While there are concerns that the economy is becoming less competitive, evidence based on rising concentration at the industry level are not convincing (Shapiro, 2018[20]).Recent empirical work suggests that merger and acquisition activity tends to result in higher markups and not increases in firm-level productivity (Blonigen and Pierce, 2016[21]), which may bear closer scrutiny.

A particular challenge in ensuring competitive outcomes and protecting consumer welfare arises with technological change allowing firms and markets to transform themselves rapidly. The potential for new entrants in some dynamic areas to capture markets should keep firms innovating to maintain their position. However, companies with access to big data from their customers can create more targeted market segments. These innovations have hitherto increased consumer welfare, but may have the potential to be used anti-competitively, especially in the presence of network effects (which make it difficult for new entrants to attract customers away from established incumbents). In this light, the competition authorities may have to act or promote tools that will allow consumers to counter abusive market dominance, such as portability of customer ratings. Some commentators have suggested rethinking how to define "monopolists" and "potential entry" to prevent incumbent dominant firms creating barriers to entry (Mcsweeny and O 'Dea, 2018[22]; Shapiro, 2018[20]).

More recently concern has been growing over the use by firms of non-compete contracts for employers (which prevent employees working for competing firms) and firms agreeing amongst themselves no poaching agreements of employees in these firms. These actions undermine labour market competition and hinder workers' ability to move to better paying jobs (Krueger and Posner, 2018[23]). The competition authorities have begun to act, bringing cases against healthcare and technology companies, amongst others, issuing guidance to ensure hiring practices comply with antitrust laws. A number of States are also acting to limit the ability of firms to impose non-compete clauses in contracts.

Table 5. Past OECD recommendations on competition policy

|

Recommendation |

Actions taken since the 2016 Survey |

|---|---|

|

Adapt antitrust policy to new trends in digitalisation, financial innovation and globalisation. Strengthen compliance with merger remedies. |

The anti-trust agencies are reacting to the changes in digitalisation including through preparing studies to examine the issues. |

|

Continue to strengthen pro-competitive policies, including in telecoms. |

The Federal Communications Commission assesses the wireless market as being competitive. With respect to broadband deployment, progress has slowed. The President has signed an Executive Order to promote rural broadband development. |

|

Use federal funding to remove unnecessary occupational licensing requirements and make others more easily portable across States. |

The competition authorities have been supporting the reduction of licensing, including through "friends of the court" briefings. The infrastructure initiative also supports this. |

Infrastructure investment

Public investment in infrastructure has slowed from the beginning of the 2000s and the growth rate of the capital stock, such as highways and streets, has not kept pace with the economy and changing demands on infrastructure, leading to rising congestion and bottlenecks. Furthermore, deferred maintenance of existing infrastructure has led to deteriorating quality, prompting calls for investment to upgrade infrastructure assets, such as roads and bridges (ASCE, 2017[24]).

The administration has unveiled plans for raising infrastructure investment by making better use of private sector investment to leverage Federal spending of $200 billion over ten years to $1.5 trillion. However, the appropriations have not yet been made to push this plan forward. A second strand of the Administration's efforts to boost investment is through streamlining the permitting process with the aim of reducing the length of time between project initiation and completion.

Improving the investment climate and boosting the provision of infrastructure should support higher productivity. The CBO and CEA estimate that improvements to core infrastructure could in some circumstances generate a marginal return on public capital in the range of 8 % to 13% (CEA, 2018[4]). Given the current financing of key infrastructure, it is also important that conditions ensure sustainability by supporting the ongoing maintenance of infrastructure assets. In the road transportation sector, in particular, quality can be poor and backlogs of maintenance work have built up. Deferred maintenance is also an important issue for other infrastructure sectors, including mass transit and drinking water and wastewater treatment.

Financing for the road transportation network has been insufficient to ensure the necessary expansion and maintenance of existing structures. Notably, the gasoline tax is the major source of dedicated revenue for the Highway Trust Fund, which supports highway and intermodal infrastructure assets as well as mass transit. The gasoline tax has proven resistant to uprating and remains amongst the lowest in the OECD (Figure 19); as a result, revenues have fallen short of outlays, threatening the Fund's solvency. More fuel efficient cars and electric vehicles exacerbate the situation by undermining the tax base, while still causing wear and tear and contributing to congestion. Funding infrastructure spending with user fees, more common in OECD countries than in the United States, may help to ensure that investment corresponds to transportation needs and reduce the risk of projects with negative expected value.

An important element of the Administration’s infrastructure initiative is attracting private investors to participate in public infrastructure projects; this may require the use of flexible risk- and profit-sharing arrangements that go beyond the basic user fee or availability payments models typically used in public-private partnerships. Particularly when future demand is highly uncertain, flexible incentive structures that incorporate sharing of risks and rewards at both the low and high-end of the demand spectrum can create additional options for private investors that benefit both taxpayers and private sector investors.

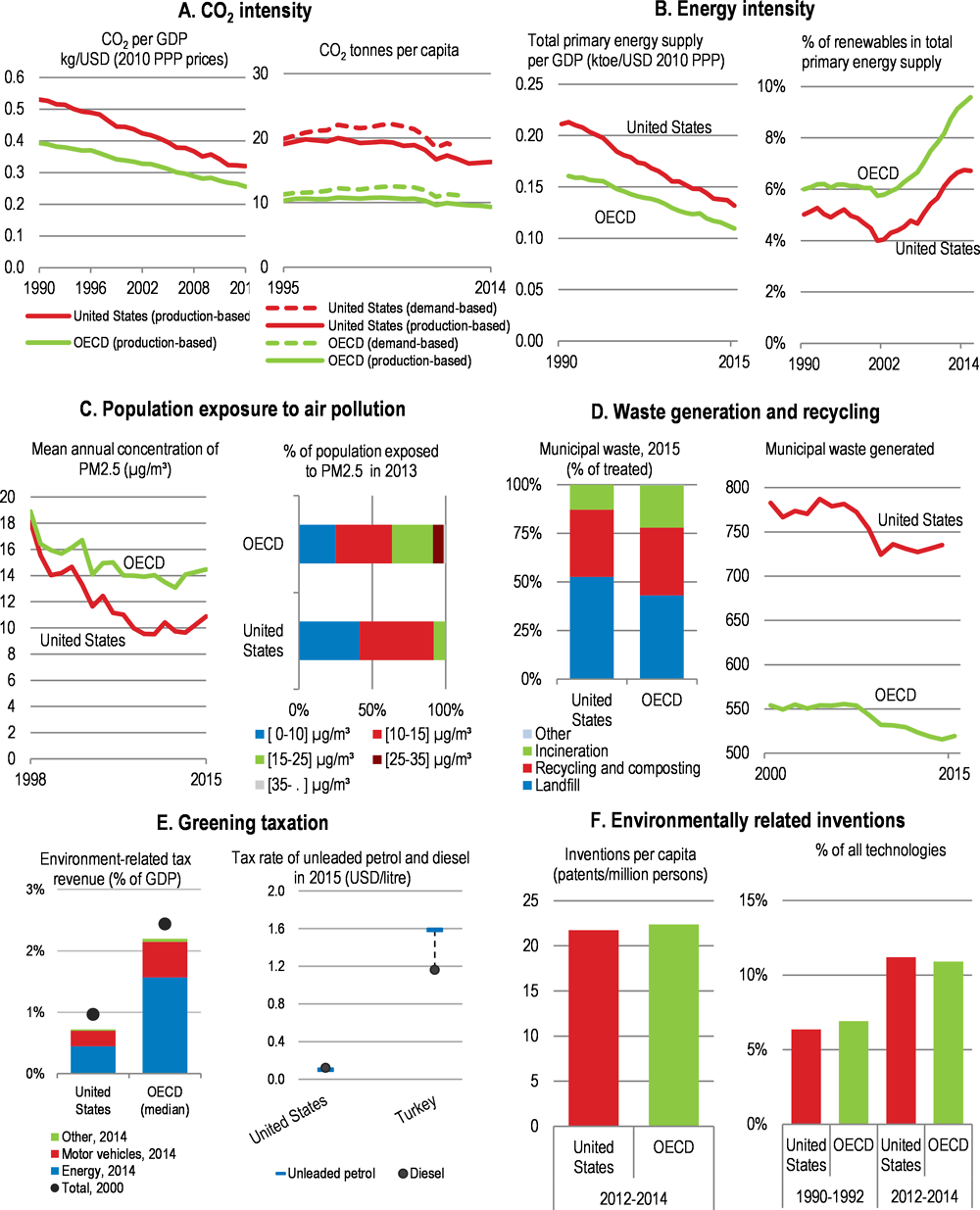

Figure 19. Environment-related taxation is low in comparison with the OECD average

Furthermore, moving towards greater use of user fees, congestion pricing, and pricing based on distance travelled encourage users to take into account the costs of congestion and road wear and tear, while providing information on where infrastructure is needed as well as financing. Greater reliance on user fees and congestion charges will also impact on locational choices and ultimately make urban areas more compact by reducing the amount of sprawl. This not only potentially affects the emissions of greenhouse gases (which are typically larger in less dense urban areas) but improve the accessibility of jobs to American workers. These objectives would be further promoted by urban development taking into account the needs for mass transit systems and accessibility. There is also scope for Federal programmes to encourage greater co-ordination across State and local jurisdictions, the absence of which can undermine city-level productivity and potential economies in large multi-jurisdictional infrastructure projects.

Another infrastructure challenge is improving access to fixed broadband, particularly in rural areas (OECD, 2018b). This is important not only in rolling out modern technology that can better integrate localities into wider economic networks, but can also provide access to healthcare and education in the most remote locations. The Federal Communications Commission (FCC) has allocated $2 billion in 2018 to use in competitive bidding auctions to expand access to nearly 1 million homes. Municipal networks have also been created in some cities, often using existing infrastructure to cut costs. These initiatives have been supported by the FCC, which is also identifying unreasonable regulatory barriers to broadband deployment. A recent Executive Order also promotes the deployment of rural broadband.

Table 6. Past OECD recommendations on environmental policy

|

Recommendation |

Actions taken since the 2016 Survey |

|---|---|

|

Work towards putting a price on carbon, such as by implementing the proposed $10 per barrel tax on oil and the Clean Power Plan. |

No action taken |

Tax reforms are changing the business environment

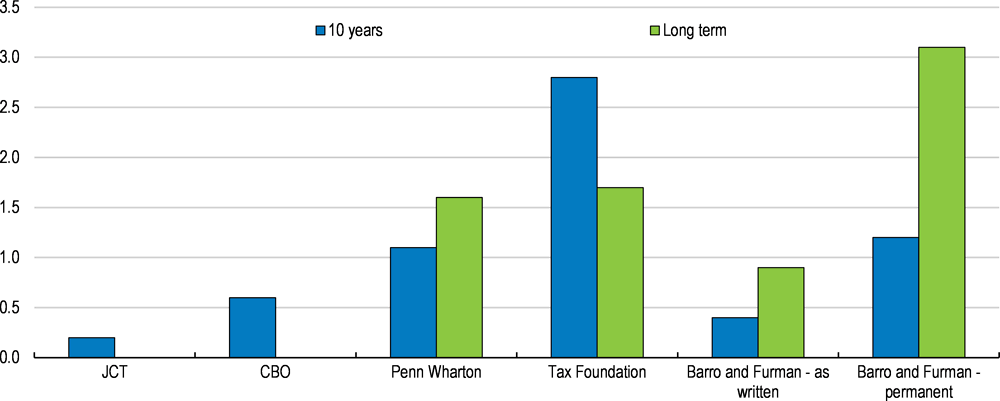

Tax reforms in late 2017 introduced significant changes, which had been discussed for many years and advocated in previous Economic Surveys (Table 7). The main thrust of the reforms reduced marginal statutory tax rates for personal and corporate income, which combined with simplification will reduce distortions embedded in the tax system and spur greater investment (Box 9).

Assessments of the impact of the reforms on corporate taxation suggest they will boost capital investment and raise the level of GDP (Figure 20). Official scoring by The Joint Committee on Taxation suggests the reforms will raise the level GDP by around 0.7% on average over the next decade though falling to just 0.1-0.2% by the end of the decade (JCT, 2017[25]). In part this is due to the removal of 100% expensing on investment (and rising interest rates). If on the other hand these provisions were permanent, the estimates made by Barro and Fuman (2018[15]) suggest that the impact on the level of GDP could be substantial, particularly when taking into account dynamic feedback. One concern is that the structure of the tax reform will reduce incentives to invest in research and development as the R&D amortisation provision is set to expire.

The tax reform introduces important innovations, particularly on the international side (Box 10). The shift towards a semi-territorial tax system and the associated measures to discourage moving intellectual property to book profits in low-tax jurisdictions should reduce aggressive tax planning and discourage corporate inversions. The extent to which these moves contribute to multinationals increasing capital investment in the United States is less certain given that these are major changes and past experience gives little guidance. A review of the literature suggests that in some cases the effects could be sizeable (CEA, 2018[4]).

Bearing in mind the uncertainty over the impact on investment decisions, the tax reforms is estimated to lead to budget shortfalls. These could see deficits expand by 0.6-0.8 percentage point and see Federal government debt rising by up to six percentage points over the next ten years, other things being equal. The distributional consequences are complex, in particular as under current law many of the provisions are set to expire, and will only be known over time.. In the near term, the increase in the standard allowance and the Child Tax Credit will provide a boost to low-income households while the reduction of some regressive tax expenditures, such as mortgage interest deduction, will tend to have a larger negative impact on higher-income households. On the other hand, the absolute average net tax reductions are larger for high-income households (Auerbach, Kotlikoff and Koehler, 2018[2]).

Figure 20. Estimated impact of tax reforms on GDP

Effect on the level of GDP

Note: The JCT and CBO estimates are based on the tax reform act as written in law. The Penn Wharton estimate embody assumptions that the sunset clauses occur unexpectedly. The Tax Foundation estimate takes into account that provisions expire. The Barro and Furman estimates make assumptions that the corporate tax reforms expire as planned or remain in place.

Source: OECD compilation.

Box 9. The 2017 tax reform

A major tax reform was signed into law at the end of December 2017. The Act is a complex mixture of permanent and temporary elements. The main domestic elements are:

Personal income tax rates are reduced from 2018, but changes expire in 2025. The top marginal rate is reduced from 39.6% to 37%. Tax rates are lowered for most of the remaining tax brackets. The standard deduction is increased and the Child Tax Credit is expanded. The threshold for the estate tax is doubled to $22 million. A change in the method of indexation of personal income tax brackets to reflect inflation more accurately will see people moving into higher brackets more quickly

The reform eliminates personal exemptions, and limits State and Local tax deductions to $10,000. Mortgage interest deduction is capped at interest on $750,000 worth of loans (down from $1 million). Deductions for education and medical expenses are reduced.

Changes to the taxation of business income include cutting the federal government's statutory corporate income tax rate from 35% to 21%. The rate of bonus depreciation is increased to 100% in 2018 to 2022, after which it is phased out by 2026.

Individuals receiving income from pass-through businesses can deduct 20% of that income from their taxable personal income tax. In line with other changes to personal income taxation, this will expire in 2025.

Business interest deductions are disallowed for interest in excess of 30% of measures of business income (EBITDA until 2021 and EBIT thereafter). A carryback treatment of the net operating loss deduction is repealed.

A tax on un-repatriated foreign earnings will be levied at either 8% or 15.5%, depending on whether the earnings are illiquid or liquid.

Table 7. Past OECD recommendations on fiscal policy

|

Recommendation |

Actions taken since the 2016 Survey |

|---|---|

|

Cut the marginal corporate income tax statutory rate and broaden its base, notably by phasing out tax allowances. |

Significant reforms were introduced in 2018 |

|

Boost public investment spending with long-term benefits: infrastructure, skills, innovation, health and environmental protection. |

Plans have been announced |

|

Boost investment in, and maintenance of infrastructure; in particular, promote mass transit. Use federal programmes to encourage co-ordination across State and local jurisdictions. |

Plans have been announced |

|

Make R&D tax credits refundable for new firms. |

No action taken |

Box 10. Tax reform and international taxation regimes

The Act contains a number of international tax provisions that will align the US tax system with international standards and practice. The Act incorporates multiple recommendations of the OECD/G20 Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (BEPS) project. Important anti-BEPS measures include provisions enhancing controlled foreign corporations rules (CFC) to expand the circumstances in which a foreign corporation will be treated as a CFC, including in situations where a US person owns “low vote” stock that represents at least 10% of the value of the foreign corporation. The Act also includes provisions against hybrid mismatch arrangements, and limitation of interest deductibility.

The tax reform introduces a minimum tax on “global intangible low-taxed income” (GILTI); this regime requires US shareholders that are 10% owners of CFCs to include in income excess returns earned by those CFCs, but allows a 50% deduction and a partial foreign tax credit that reduces the effective US rate on GILTI. The GILTI is intended to stop US corporations from shifting assets to low-tax jurisdictions.

The Act includes a “base erosion and anti-abuse tax” (BEAT), which is an anti-base erosion rule in the form of an alternative minimum tax that requires US corporations and permanent establishments of foreign corporations to pay an additional amount of tax to the extent their liability computed on a “modified taxable income” base (which disallows foreign-related party deductions) with a reduced BEAT rate exceeds their regular CIT liability. The BEAT only applies to large taxpayers with average annual consolidated US gross receipts of greater than $500 million. Additionally, the BEAT only applies if a taxpayer’s base erosion payments exceed 3% of all deductible payments (2% for banks and securities dealers). The BEAT would apply to US corporations that make deductible payments (other than cost of goods sold) to related foreign corporations. The BEAT generally would not have a significant effect on foreign MNEs selling goods to related US distributors, as the cost of goods sold is not included in the modified tax base. It could, however, have a significant effect on foreign MNEs selling services or licensing intangibles in the US market through a US distributor.

In addition to the GILTI rule, which provides a minimum tax on intangible income, another provision included in the Act provides for a reduced rate on “foreign-derived intangible income” (FDII). US corporations may deduct an amount equal to 37.5% (until 2025; 21.875% afterwards) of its FDII from taxable income that US companies earn from serving foreign markets; the FDII is calculated by multiplying the U.S. corporation’s “deemed intangible income”, or excess returns, by the fraction of its deduction-eligible income that is foreign-derived, resulting after deductions in an effective tax rate of 13.125% on the FDII, compared with the 21% corporate income tax rate. The FDII is a special regime designed to keep US companies’ intellectual property in the US, as the FDII rate is similar to the effective rate on CFC income from mobile factors under the GILTI regime. The FDII regime will be reviewed in 2018 by the OECD's Forum on Harmful Tax Practices to determine whether it is compatible with BEPS Action 5 on harmful tax practices.

The US has gone a long way in implementing the BEPS measures. Importantly, the US tax reform shows that the US is serious about providing a competitive tax system while at the same time protecting its tax base.

Improving employment opportunities

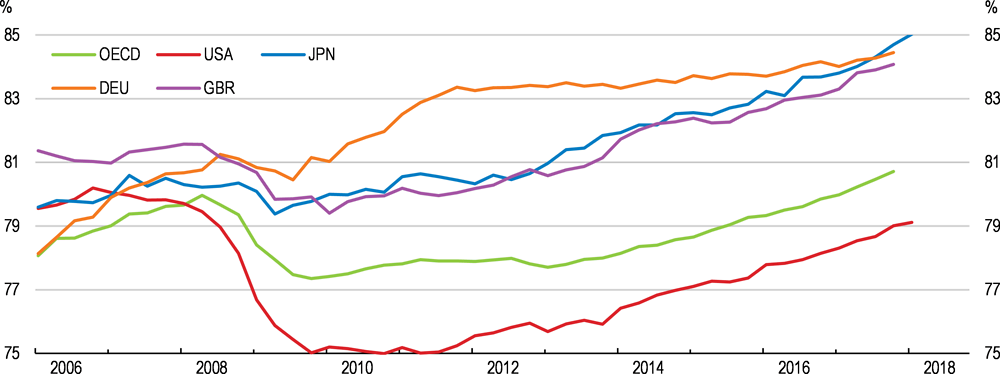

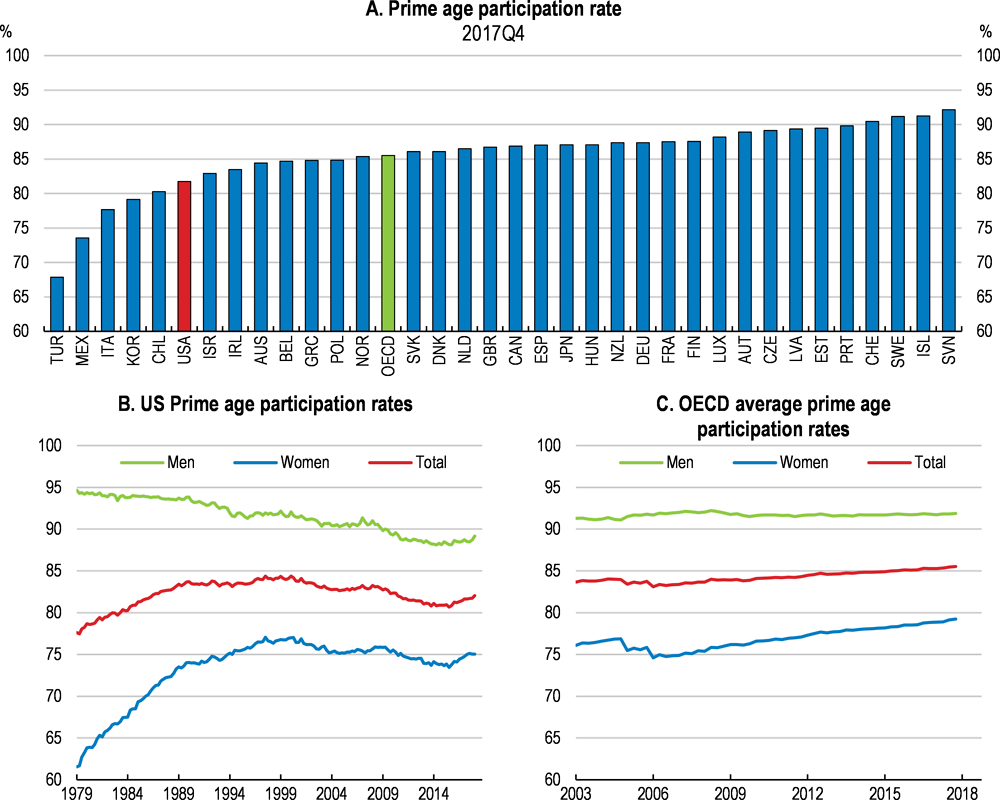

The current expansion has reversed past job losses and has brought many people back to employment. Although unemployment is historically low, this does not mean that all available workers are employed. In fact, employment-to-population rates remain below the pre-crisis peak in 2007, which in turn remained below the pre-2000 crisis peak. As the population ages, the retirement of the baby boomers continues and the inflow of new workers slows, the prospects for employment-led growth correspondingly weaken (Lacey, Toossi and Dubina, 2017[26]). While the employment to population ratio is around the OECD average for prime age workers it is lower than many other high-income countries notably Germany, Japan and the United Kingdom (Figure 21), suggesting scope to increase employment further. In this context, policies that assist people back into employment could help offset demographic pressures and further boost incomes, with potentially significant effects on lower-income households.

Figure 21. The employment to population rate is relatively low, though recovering

Note: Prime age adults are those aged 25-54 year-old. The employment rate for a given age group is measured as the number of employed people of a given age as a ratio of the population in that same age group. OECD refers to a simple average.

Source: OECD Employment and Labour Market Statistics.

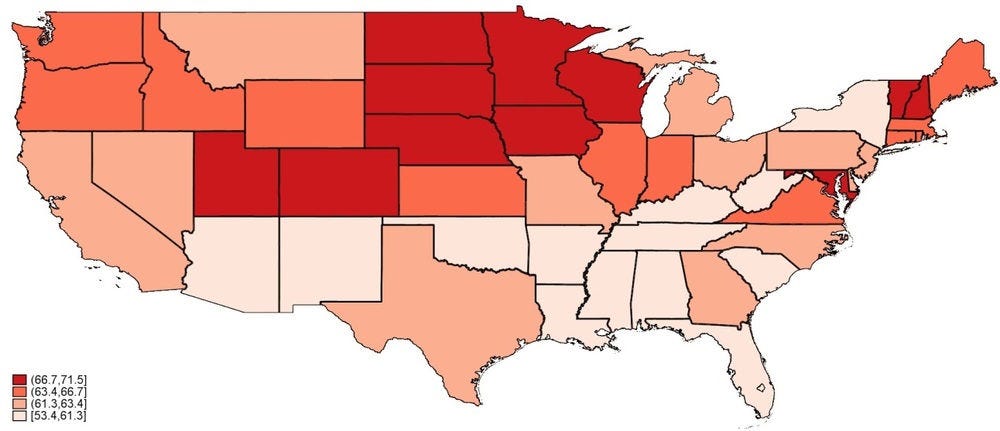

In comparison with many other OECD countries, a large share of the population remains at the fringes of the labour market (Figure 22). Participation is particularly low for some groups, including those with lower educational attainment. There are also demographic differences with participation amongst black men and Hispanic women lower than other groups. Non participation is also regionally quite heterogeneous (Figure 23) (Guichard, 2018[27]). A worrying dynamic has been declining participation of prime age workers, especially men. The participation of women has recovered somewhat recently, while males that are no longer participating tend to remain out of the labour force (Varghese and Sutherland, 2018[28]). A number of factors behind this drop have been advanced, including the pay-off from job experience becoming more muted over time for some lower-skilled individuals (Elsby and Shapiro, 2012[29]) to young men living with close relatives and occupying themselves by playing video games (Aguiar et al., 2017[30]). This is especially the case for young men with no more than high school education.

Figure 22. Prime age labour force participation is low

Note: Prime age adults are those aged 25-54 year-old. The labour force participation rate is calculated as the active population (employed plus unemployed) divided by the population in that same age group. OECD refers to a simple average.

Source: OECD Labour Force Statistics.

Figure 23. Participation varies significantly across States

Note: Civilian noninstitutional population ages 16 and older.

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics.

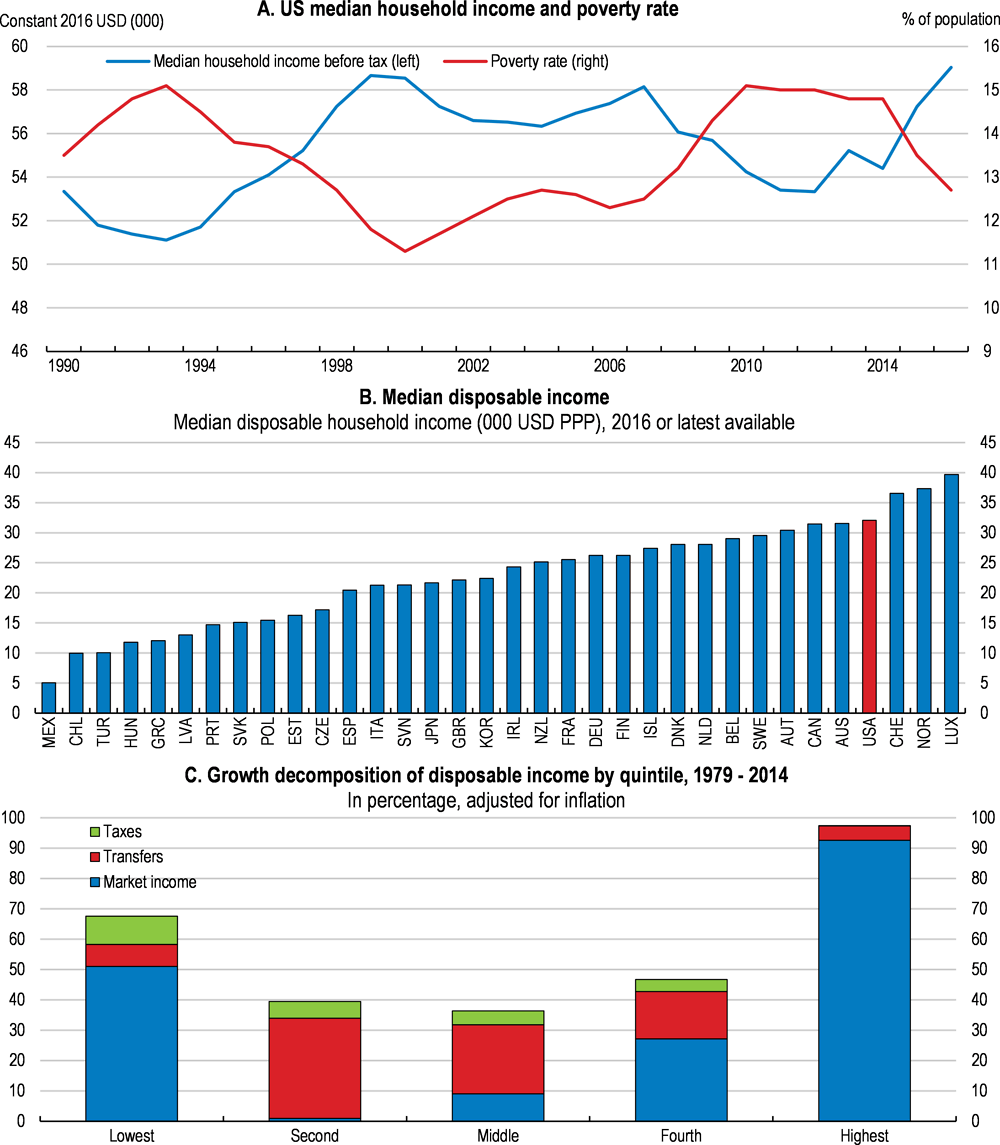

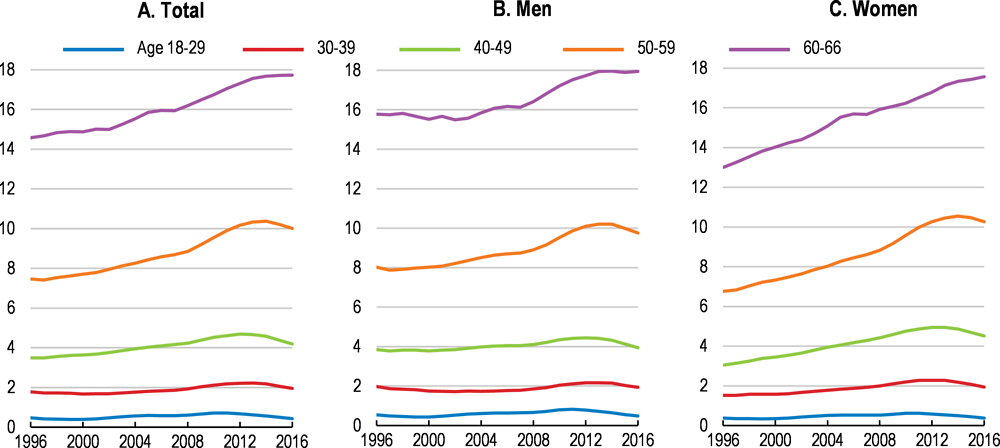

Robust employment growth above the rates needed to account for new entrants into the labour force has reduced unemployment near historically-low levels, which has resulted in tight labour markets for fast-growing locations and occupations. Together with stronger wage gains, these trends have helped reverse the decline in real median household income after the recession. At the same time, the share of the population below the official poverty line declined in both 2015 and 2016. The OECD measure of relative poverty of disposable income also fell in 2015, the latest year for which data are available. Over a longer period, gains in the middle of the income distribution have been modest in comparison to those at the bottom and top (Denk et al., 2013[31]) (Figure 24).

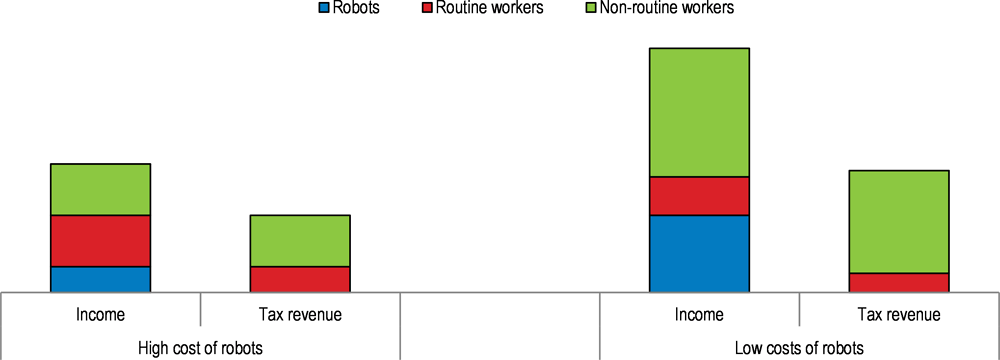

The acceleration in wage growth foreseen over the next few years will be important in inducing additional inactive workers to return to work, boosting incomes further. Helping more vulnerable groups into employment would likely lower costs to government budgets, through reduction in spending on benefits, healthcare and in some cases criminal justice, while raising additional tax revenue. Success will also help mitigate shocks from automation, when there is a danger of unemployment leading to non-participation (Daubanes and Yanni, 2018[32]) (Box 11). Getting people into employment needs to work on several margins, including reattaching discouraged workers that are currently out of the labour force, reducing the disincentives due to disability and other government programmes, and helping overcome drug addiction.

Figure 24. Median disposable income is high and is recovering

Note: The official poverty definition (panel A) uses money income before taxes and does not include capital gains or noncash benefits (such as public housing, Medicaid, and food stamps). In panel C, households are ranked by "income before transfers and taxes" and not "before tax income" as in (Denk et al., 2013[31]).

Source: CBO; OECD IDD database; and Thomson Reuters.

Box 11. Taxing robots

Concerns about how robots can displace workers and lead to heightened inequality have given rise to arguments to slow down technological progress, including by imposing taxes on robots. In addition to the direct effect on employment, others have worried about the ability of the government to raise revenue and the scope it can give for tax avoidance.