This country note provides an overview of the labour market situation in Japan drawing on data from OECD Employment Outlook 2024. It also looks at how the transition to net-zero emissions by 2050 will affect the labour market and workers’ jobs.

OECD Employment Outlook 2024 - Country Notes: Japan

Labour markets have been resilient and remain tight

Labour markets continued to perform strongly, with many countries seeing historically high levels of employment and low levels of unemployment. By May 2024, the OECD unemployment rate was at 4.9%. In most countries, employment rates improved more for women than for men, compared to pre‑pandemic levels. Labour market tightness keeps easing but remains generally elevated.

Over the past year, both unemployment and employment have been stable in Japan. In May 2024, the unemployment rate remained unchanged at 2.6%, and is projected to decline to 2.4% in 2025. The level of employment has been sustained as more older people are employed, offsetting the decline in the working-age population. While the employment rate for men has remained stable at around 84%, the female employment rate has continued to increase over the last two decades, reaching 73.7% in May 2024. However, Japan’s total fertility rate has been falling for eight consecutive years, reaching a record low of 1.20 in 2023, calling for greater policy efforts to ease the burden on Japanese women who often struggle to reconcile their careers with childbearing.

According to the OECD Gender Dashboard, Japan outperforms most OECD countries in terms of PISA scores for girls, and their participation in tertiary education. However, gender inequalities emerge once they enter the labour market. The gender pay gap is the fourth highest of all OECD countries (21.3%) and that on time spent on unpaid care and domestic work is also one of the highest, reflecting a disproportionate burden of care on women. The Basic Policy on Gender Equality and Empowerment of Women 2024 acknowledges a significant share of women switching to non-regular employment contracts after childbirth as a major issue. On these grounds, the government is currently considering expanding the application of the existing wage transparency rule to firms with between 101 and 300 regular employees.

Real wages are now growing but there is still ground to be recovered

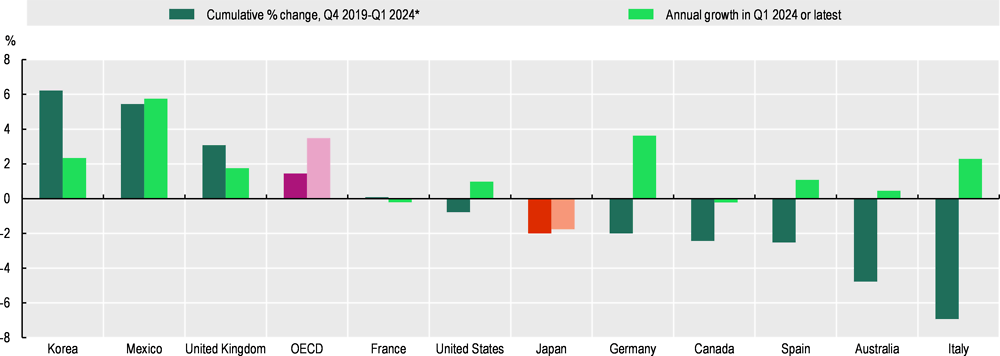

Real wages are now growing year-on-year in most OECD countries, in the context of declining inflation. they are, however, still below their 2019 level in many countries. As real wages are recovering some of the lost ground, profits are beginning to buffer some of the increase in labour costs. In many countries, there is room for profits to absorb further wage increases, especially as there are no signs of a price‑wage spiral.

From Q4 2019 to Q4 2023, real hourly wages cumulatively dropped 2% in Japan (Figure 1). Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine and the weakened yen have contributed to pushing headline inflation above 2% since April 2022. In this context, real wages per capita have declined in Japan continuously for 25 months up to April 2024.

This year’s annual spring wage negotiations (or Shunto) showed greater momentum. The negotiated nominal pay rise was up from 3.6% to about 5% according to the Japan Trade Union Confederation (Rengo). The results of Shunto are expected to gradually take effect by August. To ease the impact of rising prices, the Japanese Government introduced a new tax deduction of JPY 40 000 per person from June and it is also planning to effectively reinstate the subsidy for electricity and gas bills from August to October, which was initially terminated in May. Overall, inflationary pressures are expected to continue eating into nominal wage growth.

There is little evidence of a wage‑price spiral in Japan. The GDP deflator, which accounts for domestic price inflation, increased 3.4% on a year-on-year basis in Q1 2024 but the contribution coming from compensation of employees (or unit labour costs) was 1.6%, whereas unit profits accounted for 1.8%. Unit labour costs have not significantly contributed to domestic inflation since Q1 2023. This suggests that the Japanese average firm was able to more than adjust for prices, while remunerations paid to workers did not increase at the same rate as prices.

The Japan Fair Trade Commission (JFTC) special survey revealed that a significant share of firms report difficulties in negotiating prices with buyers on the grounds of rising labour costs, resulting in the publication of JFTC guidelines about passing on labour costs during price negotiations. This is important for SMEs to gain some leeway for wage increases while enjoying a fair share of profit, as their struggles of balancing rising labour costs and diminishing profits are well documented.

Figure 1. Real wages remain below 2019 levels in most countries

Note: * For Canada, Japan, Korea and Mexico, the annual growth refers to Q4 2022‑Q4 2023 and the cumulative percentage change to Q4 2019‑Q4 2023. OECD is the unweighted average of 35 OECD countries (not including Chile, Colombia and Türkiye).

Source: OECD Employment Outlook 2024, Chapter 1.

Climate change mitigation will lead to substantial job reallocation

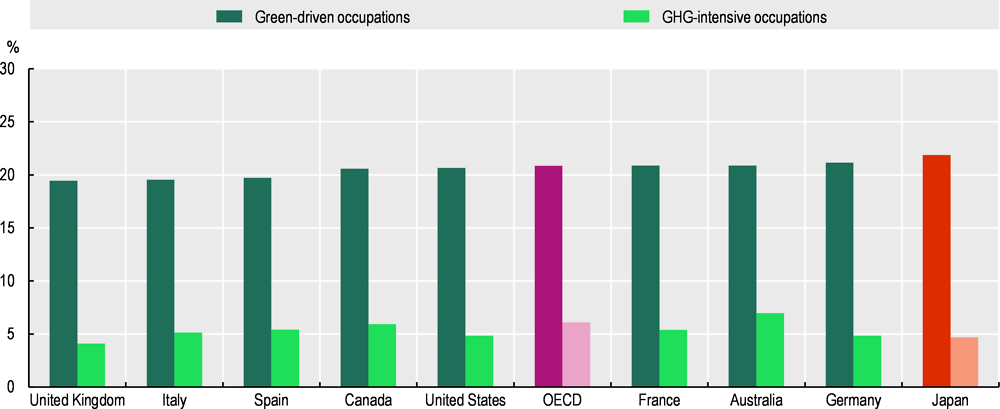

The ambitious net-zero transitions currently undergoing in OECD countries are expected to have only a modest effect on aggregate employment. However, some jobs will disappear, new opportunities will emerge, and many existing jobs will be transformed. Across the OECD, 20% of the workforce is employed in green-driven occupations, including jobs that do not directly contribute to emission reductions but are likely to be in demand because they support green activities. Conversely, about 7% is in greenhouse gas (GHG)-intensive occupations.

Japan displays a higher than average share of green-driven occupations and a lower than average share of GHG-intensive occupations, suggesting potentially high demand for skills relevant to green-driven occupations and lower costs of job replacement from GHG-intensive occupations. Indeed, 21.9% of total employment is classified as green-driven occupations and 4.7% as GHG-intensive ones on average during the period of 2015 to 2019 (Figure 2). Moreover, Japanese men are more likely to be employed in green-driven occupations than Japanese women.

The Green Transformation (called “GX” in Japanese) is gaining more policy attention. The Basic Policies for Economic and Fiscal Management and Reform 2024 highlight a commitment to increase GX investment to more than 150 trillion yen in the coming decade and to lay out a national strategy within FY2024. Also, an Emissions Trading System will be rolled out from FY2026 and fossil fuel levies are expected to be introduced from FY2028.

The co‑ordination of green policy and labour market or skill policy across ministries can be further improved. For instance, there are several training programmes on decarbonisation targeted at local municipalities, local enterprises, local financial institutions, and universities. They are organised individually by different ministries (including the Ministry of Environment, Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications, Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry and Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology). Although these programmes may be fit for purpose on their own, enhancing cross-cutting collaboration and linking them collectively to high-level goals (e.g. carbon neutrality by 2050) could better align policy efforts with desired outcomes and milestones. The Central and Regional Consortiums for Vocational Abilities Development Promotion, established by the Ministry of Health Labour and Welfare in 2022, can be a starting point to discuss green skills for skill policy planning and assessment.

Figure 2. One out of five workers is employed in green-driven occupations

Percentages, average 2015‑19

Source: OECD Employment Outlook 2024, Chapter 2, Figure 2.3.

Contact

Satoshi ARAKI (✉ Satoshi.araki@oecd.org)

Glenda QUINTINI (✉ Glenda.quintini@oecd.org)

This work is published under the responsibility of the Secretary-General of the OECD. The opinions expressed and arguments employed herein do not necessarily reflect the official views of the Member countries of the OECD.

This document, as well as any data and map included herein, are without prejudice to the status of or sovereignty over any territory, to the delimitation of international frontiers and boundaries and to the name of any territory, city or area.