A Digital Supply and Use Tables (SUTs) framework consistent with the System of National Accounts (SNA) is needed to improve the visibility of digitalisation in macroeconomic statistics. This chapter discusses the recent growth of the digital economy, existing work to measure digitalisation, and the proposal to include Digital SUTs in the 2025 update of the SNA.

OECD Handbook on Compiling Digital Supply and Use Tables

1. Overview

Abstract

The purpose of the handbook

This handbook and the Digital Supply and Use Tables (Digital SUTs) framework it advocates have been created to respond to demand for more information on the impact of digitalisation on the economy, and how this may be represented in the System of National Accounts (SNA). The handbook has been developed under the auspices of the Informal Advisory Group (IAG) on Measuring GDP in a Digitalised Economy, a body established by the OECD Committee on Statistics and Statistical Policy in 2017 to progress the digitalisation measurement agenda.

The handbook serves two broad purposes:

To define clearly the various concepts used, list the high priority indicators, and set out expectations for compilers and users of Digital SUTs.

To document and share the work currently being undertaken by national and international organisations to make digitalisation more visible in macroeconomic statistics. This work will assist countries in their efforts to populate the Digital SUTs (OECD, 2016[1]).

Compilation of the Digital SUTs is still in its infancy and the handbook, like the Digital SUT framework, is not a finished product. The handbook is intended to be kept updated to maintain its relevance and keep abreast of the most recent developments in the compilation of the Digital SUTs. It has not been written solely as a reference tool, but also as a way of highlighting this important work and encouraging efforts to improve data collection and compilation practices associated with the framework.

The need for the Digital SUTs framework

Digitalisation has fundamentally altered the production and consumption of goods and services worldwide. Firms have been able to leverage digitalisation in order to disrupt established markets and improve the efficiency of their production processes. At the same time, digital transformation has permitted consumers to access a larger variety of goods and services, while exercising greater control over the characteristics of the transaction processes.1

The increasing impact of digitalisation on the economy can be seen, for example, in the automation of tasks previously done by humans and the growing reliance on digital tools to communicate and carry out professional work. The growth of digitalisation of the production and consumption of goods and services is visible when looking at indicators such as the percentage of businesses with a presence on the internet, and the percentage of consumers using the internet to make purchases.

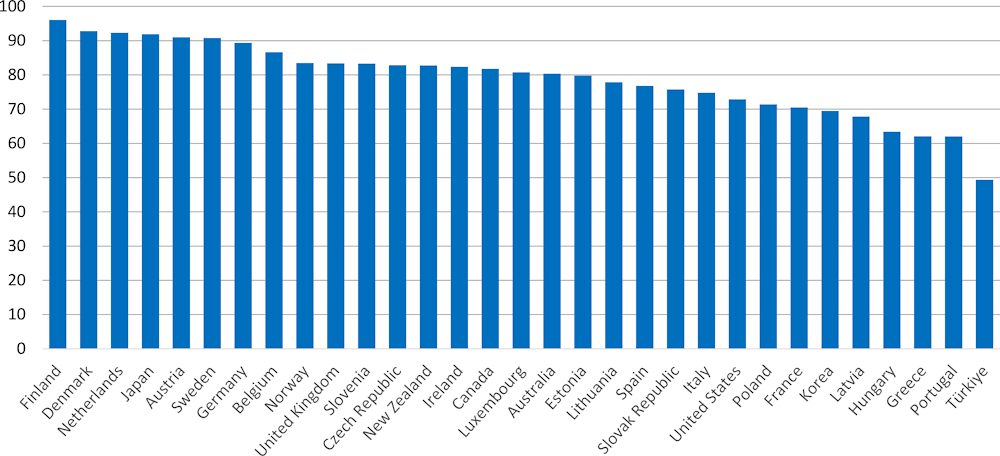

The high proportion of firms within OECD countries with a web presence provides clear evidence that a digital presence has now become a fundamental requirement for most businesses. Importantly, the percentages shown in Figure 1.1 include all (non-micro) businesses with a web presence, regardless of industry or business activity. This demonstrates that this requirement is not only for new firms or “digital natives” for whom digital interaction is fundamental to their business model, but rather, for all firms, including those that now use digitalisation to enhance existing business models.

Figure 1.1. Proportion of businesses with a web presence, OECD countries

% of businesses, 2021 or latest year

Note: All business (10 employees or more).

Source: (OECD, 2022[2]) OECD Going Digital Toolkit, based on United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) core indicators on Information and Communication Technology (ICT) use by business and the OECD ICT Access and Usage by Businesses Database, http://oe.cd/bus.

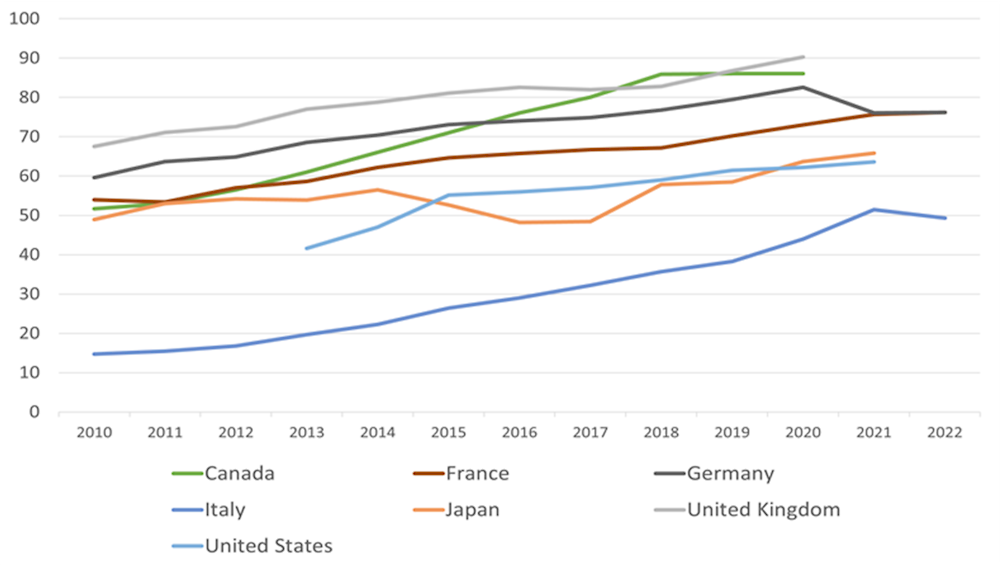

The increasing impact of digitalisation on consumers is also clear; one example is purchasing goods and services online. The percentage of consumers making e-commerce purchases has grown significantly since 2010, increasing by 42 percentage points in Canada and 22 percentage points in the United States (see Figure 1.2). In the United Kingdom in 2020, 90% of people aged 16 to 74 purchased something online.

Figure 1.2. Proportion of internet users who have made e-commerce purchases, G7 countries

% of users, 2010 to 2022

Note: An e-commerce purchase describes the purchase of goods or services conducted over computer networks by methods specifically designed for the purpose of receiving or placing orders.

Source: (OECD, 2022[2]) OECD Going Digital Toolkit, based on OECD ICT Access and Usage by Households and Individuals Database, http://oe.cd/hhind.

The production of businesses with a web presence and the value of the e-commerce purchases are included within countries’ national accounts, which are compiled according to the international standards of the 2008 System of National Accounts (SNA). However, their explicit impacts are not visible in the conventional accounts produced by countries.

To improve the visibility of digitalisation in macroeconomic statistics, the Digital SUT framework was developed. The framework, which will be explained in detail in Chapter 2, supplements the conventional Supply and Use Tables (SUTs) of the 2008 SNA by delineating product rows based on the nature of the transaction: digitally ordered / digitally ordered via intermediation platform / not digitally ordered; and by adding columns to reflect the proportion digitally delivered. In addition, Information and Communication Technology (ICT) products are aggregated to provide a simpler representation of firms’ and consumers’ increasing reliance on these products. Two specific products, digital intermediation services and cloud computing services, are separately identified due to their fundamental importance to the digital economy. Finally, by classifying firms to seven new “digital industries” based on the extent to which their businesses depend on digitalisation, it is possible to produce estimates of output, value added or even employment of digital industries.

The absence of key trends associated with digitalisation within the national accounts has sometimes caused confusion about what is (and is not) included in the production boundary of the national accounts2 and who is (or is not) benefiting from digitalisation. For example, Coyle (2017, 2018) and others3 have suggested that GDP may be understated because digitalisation is not being appropriately recorded in the national accounts. Conversely, others4 have argued that the challenges caused by digitalisation are not a new or unique measurement concern, and mismeasurement, if any, is minor. While the discussion on (mis)measurement focuses on a range of issues, not all of which will be solved by the construction of the Digital SUTs,5 it is clear that additional information and statistics on the size and influence of digital activity would be beneficial for users. The IMF summed up the sentiment in a 2018 report on the digital economy: “Data users need more extensive and more granular statistics on the scale and structure of the digital activity to understand economic developments in a digitalised economy” (IMF, 2018[3]).

This need for more information has been picked up by other international groups such as the G20 Digital Economy Task Force (DETF), which in 2018, 2020 and 2021 requested a greater focus on measuring digitalisation and its impact on the economy. The task force called for the development of satellite accounts focusing on the digital economy (G20 DETF, 2018[4]). It also advocated the G20 Roadmap toward a Common Framework for Measuring the Digital Economy including Digital SUTs as a means to improve the visibility of digitalisation in the national accounts (G20 DETF, 2020[5]), (OECD, 2020[6]). Finally, it emphasised the need for co-operation and sharing of best practices amongst national statistical offices to delineate and improve the integration of the digital economy in macroeconomic statistics (G20 DETF, 2021[7]).

This handbook attempts to achieve both of the aims laid out by the G20 DETF:

to clearly outline a framework whereby meaningful indicators of digital activity can be produced consistent with the national accounts, and

to provide an outlet where methods and statistical approaches can be shared in order to improve capability across the statistical community.

Meeting the needs of policy makers is, of course, central to the design of new statistics and statistical standards. Therefore, this handbook is designed both to address concerns about mismeasurement, which might cast doubt on the reliability of the accounts, and also, more generally, to increase the usefulness of the national accounts for policy making purposes.

Existing work to measure digitalisation and how this relates to the Digital SUTs

An absence of frameworks or a definitive definition of the digital economy has meant that work has been undertaken on a relatively ad hoc basis, with different countries using different definitions and methodology for generating estimates of the digital economy.6 The United States (Barefoot et al., 2018[8]), Canada (Statistics Canada, 2019[9]) and Australia (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2019[10]) have all published estimates of the digital economy. These estimates were created by identifying certain products as “digital” and then calculating the value added associated with the production of these products. This has the benefit of producing replicable estimates consistent with the national accounts. However, by simply grouping products, they struggle to capture the full impact of digitalisation on the economy, including ordering and delivery of non-digital products via digital channels.

Conversely, estimates that focus solely on e-commerce and the amount of consumption taking place via digital channels (including digital intermediation platforms) may overlook the important impact that ICT goods and services are having on the production of digital and non-digital products. Some publications have tried to be more comprehensive. For example, one estimate of the digital economy for China combined production contributing to digital outputs and “value added and employment generated through the use of digital technology in sectors other than ICT” (Miura, 2018[11]). The resulting estimate was a much higher proportion of GDP than those discussed above for the US, Canada and Australia.

The Informal Advisory Group on Measuring GDP in a Digitalised Economy sees the digital economy as a multidimensional phenomenon. It acknowledges that compilers in national statistical offices, policy makers and other users hold different views on any single definition of the digital economy and resulting estimates such as total output, value added or employment of the digital economy. This handbook does not advocate a single definition of the digital economy, but instead presents a Digital SUT framework that aims to provide different perspectives on how digitalisation affects the economy.

By adopting this approach, the Digital SUTs can produce a suite of indicators on different aspects of digital activity in the economy. These include the value of products ordered or delivered digitally, the importance of digital products to firms during production, and the output and value added of specific types of producer that are significantly impacted by or completely reliant on digital technology. Chapter 2 provides further details.

At the same time as the development of the framework for the Digital SUTs, there has been work taking place on improving the measurement of digital trade. The first edition of the Handbook on Measuring Digital Trade, published in 2020, outlined the basic digital trade framework (OECD, WTO and IMF, 2020[12]). This has now been revised and updated (IMF, OECD, UNCTAD, WTO, 2023[13]) in close coordination with the work on the Digital SUT handbook. Importantly, the approach to digital trade measurement and the framework for the Digital SUTs are both centred around delineating transactions based on the nature of the transaction, so estimates of digitally ordered and delivered imports and exports produced for digital trade tables should provide useful inputs for the Digital SUTs.

The use of Digital SUTs in the updated SNA

The development of a Digital SUT framework consistent with the SNA and compilation by countries was first suggested by the OECD IAG on Measuring GDP in a Digitalised Economy, which was set up in 2017. The main objective of the group was to “advance the digitalisation measurement agenda” while at the same time, serving as “a forum and focal point to share ideas and experiences; and to develop best practice”.7

Digitalisation was also picked up as a key research topic within the formal revision process of the 2008 SNA coordinated by the Inter Secretariat Working Group on National Accounts (ISWGNA) and Advisory Expert Group on National Accounts (AEG)8 (ISWGNA, 2020[14]). The Digital SUT framework, developed by the IAG on Measuring GDP in a Digitalised Economy, was put forward as a possible solution to this challenge. A formal Guidance Note, DZ.5 Increasing the Visibility of Digitalisation in Economic Statistics Through the Development of Digital Supply-Use Tables, was prepared and a Global Consultation with (mainly) national statistical offices was undertaken. The Guidance Note was endorsed at the 17th meeting of the Advisory Expert Group on National accounts in November 2021 (ISWGNA, 2021[15]). It recommends that the framework be included as a supplementary table in the update of the SNA, to be published in 2025 (ISWGNA, 2021[16]).

The Global Consultation provided strong support for the Digital SUT framework with a majority of respondents considering the compilation of Digital SUTs as “very relevant” or “somewhat relevant” for their country. Furthermore, around two-thirds of respondents indicated an intention to compile Digital SUTs in the next three to five years. However, a majority also indicated that they would need help with capacity building, methodological or practical guidance (ISWGNA, 2021[17]). Such feedback, which came from all regions of the world, strengthened the case for a handbook to provide examples of how Digital SUTs can be compiled.

As with many changes incorporated into the 2025 update of the SNA, there will be a need for complementary information such as guidelines, handbooks on methodology and material from expert groups and task forces to support production of the new or revised estimates outlined in the SNA. This handbook is one such output.

Digital SUTs as a foundation for digital economy satellite (thematic) account

The Digital SUT framework includes rows for products that are not within the 2008 SNA production and asset boundary and are not expected to be included in the 2025 SNA. These include the consumption of free digital services created by private corporations and communities.

In the Digital SUTs, the values in these rows may be added to the totals recorded in the conventional SUTs. Their inclusion also provides a basis for the compilation of a Digital Economy Satellite Account (DESA). Satellite accounts (or thematic accounts as they will be called in the updated SNA) are a fundamental component of the SNA. They may use different production and asset boundaries to those of the central framework (also known as “core accounts”) in order to “make apparent and to describe in more depth aspects that are hidden in the accounts of the central framework” §2.166 (UNSD, Eurostat, IMF, OECD, World Bank, 2009[18]). Possible outputs that might be included in a DESA are labour or occupation indicators for the new “digital industries”, the value of “free” digital services provided in exchange for access to personal information, the value of data assets held by firms, or the amount of time consumers spend using digital platforms.

As it is an extension of the core national accounts tables, measurement in a DESA can go beyond that used for the basic accounts and include methods that may differ from the core principles of the SNA. For example, several researchers have produced studies on values associated with the consumption of certain free digital services (Brynjolfsson, Eggers and Gannamaneni, 2018[19]) (Brynjolfsson et al., 2019[20]) (Coyle and Nguyen, 2020[21]). These valuations are not at market value and the interaction they describe is not considered an economic flow from the perspective of the SNA; but the value that consumers assign to these services, some of which they previously may have had to pay for, is of high analytical interest to users. Therefore, national statistical offices may wish to produce a satellite (thematic) account that incorporates such values. The non-prescriptive nature of a DESA would allow countries to focus on specific topics that are of importance to them and measure them in a way that the available data allows.

The structure of the handbook

It is important to stress that this handbook has been prepared to encourage and assist countries to compile estimates consistent with the Digital SUT framework. It does not pretend to be the final and definitive voice on the subject. International compilation of the Digital SUTs is still in its infancy, with only a few countries having already compiled estimates. Therefore, many of the examples in the handbook are “work in progress”. This is particularly relevant for Chapters 3 to 6, which discuss indicators that may be used to complement the conventional Supply and Use estimates published by countries. Even the components of the framework are not set in stone. Improvements may be made following lessons learned during their implementation.

The handbook is set out as follows.

Chapter 2 outlines the framework. It explains the additional rows and columns within the Digital SUTs compared to the conventional SUTs. It describes how certain outputs not only have high analytical value but are also easier for compilers to produce and therefore more likely to be targeted first during the compilation process.

Chapters 3 to 6 cover in more detail the different transactions, discuss how the various digital products are represented in the framework and describe the new digital industries. It also contains examples of how countries collect relevant information, as well as how this data can be used as indicators in the construction of the Digital SUTs. Specifically:

Chapter 3 focuses on the nature of the transaction (based on ordering and delivery of products), and how this is shown in the Digital SUTs.

Chapter 4 focuses on digital products, both those that are aggregated to provide a simple metric of digitalisation in the production process and those that are shown separately.

Chapter 5 focuses on the digital industries that are to be shown separately in the Digital SUTs.

Chapter 6 discusses how some countries have combined the information in the indicators with conventional SUT estimates to create new Digital SUT outputs. It also introduces the templates that countries can use to produce consistent estimates of high priority indicators.

Notes

← 1. The terms “digitisation”, “digitalisation” and “digital transformation” may sometimes appear to be used interchangeably, however they each represent something slightly different to each other. “Digitisation” is the conversion of analogue data and processes into a machine-readable format. “Digitalisation” is the use of digital technologies and data as well as interconnections that result in new activities or changes to existing activities. “Digital transformation” refers to the economic and societal effects of digitisation and digitalisation (OECD, 2019[124]).

← 2. The production boundary of the national accounts includes “all production actually destined for the market, whether for sale or barter. It also includes all goods or services provided free to individual households or collectively to the community by government units or NPISHs” (2008 SNA §1.40; (UNSD, Eurostat, IMF, OECD, World Bank, 2009[18]). What is not included is goods or services provided free by private enterprise. NPISHs = non-profit institutions serving households.

← 3. There is a range of documents that have addressed the impact of digitalisation on the measurement of GDP, ranging from concern regarding the increasing wedge between GDP and consumer surplus (Brynjolfsson and Collis, 2019[120]) to concluding that current GDP estimates are understated (Feldstein, 2017[119]).

← 4. Papers that have suggested that mismeasurement is not cause of the productivity slowdown include (Aeberhardt et al., 2020[123]) (Ahmad, Ribarsky and Reinsdorf, 2017[125]) (Ahmad and Schreyer, 2016[122]) and (Byrne, Fernald and Reinsdorf, 2016[121]).

← 5. Concerns regarding the impact of digitalisation on GDP can normally be placed into one of three categories; (i) whether the conceptual boundary of GDP should be altered to reflect behavioural changes brought in by digitalisation, (ii) whether the prices of new and improved digital products are being accurately measured, (iii) whether the output of new digital services are being appropriately incorporated. The Digital SUTs will assist in addressing (ii) and (iii).

← 6. For a full discussion on different definitions of the digital economy, see (OECD, 2020[6]) which build on the work of (Bukht and Heeks, 2017[26]).

← 7. Creation of the advisory group as well as the terms of reference are outlined in the following document. https://one.oecd.org/document/STD/CSSP(2016)16/en/pdf.

← 8. The ISWGNA is a multi-organisation body that provides strategic vision, direction and coordination for the methodological development and implementation of the SNA. The AEG is made up of national account experts whose task is to support the ISWGNA in its work.