This chapter assesses Mexico City’s internal control and risk management frameworks and draft internal control legislation against international models and better practices. It provides an overview of the strengths and weaknesses of the internal control and risk management framework in Mexico City, and how this could be reinforced to align with good OECD country practices in the areas reflected in the OECD 2017 Recommendation of the Council on Public Integrity.

OECD Integrity Review of Mexico City

Chapter 6. Improving internal control and risk management in Mexico City

Abstract

6.1. Introduction

An effective internal control and risk management framework is essential in public sector organisations to safeguard integrity, enable effective accountability and prevent corruption. This framework should include internal control measures, risk management and internal audit. The OECD’s 2017 Recommendation of the Council on Public Integrity encourages establishing an internal control and risk management framework that includes:

a control environment with clear objectives that demonstrate managers’ commitment to public integrity and public service values, and that provides a reasonable level of assurance of an organisation’s efficiency, performance and compliance with laws and practices;

a strategic approach to risk management that includes assessing risks to public integrity, addressing control weaknesses, as well as building an efficient monitoring and quality assurance mechanism for the risk management system;

control mechanisms that are coherent and include clear procedures for responding to credible suspicions of violations of laws and regulations, and facilitating reporting to the competent authorities without fear of reprisal (OECD, 2017[1]).

An effective internal control and risk management framework includes policies, structures, procedures, and processes that enable an organisation to identify and appropriately respond to risks.

Mexico City faces a number of challenges in the areas of internal control and risk management. These include: an environment where no comprehensive internal control legislation is currently in force (although a bill was recently adopted in the package of secondary laws); limited or outdated guidelines for staff on how to implement internal control measures; a framework that blurs areas of responsibilities, with auditors taking responsibility for internal control when senior management should be taking ownership; the absence of a systematic risk management framework; a culture where integrity is not strongly supported or promoted, because public officials have not brought in the initiatives they have launched; weak internal control measures; and an internal audit system where the independence of the Comptroller-General and the processes for audit planning and following up on audit recommendations could be strengthened.

Similar to the federal Organic Law for the Federal Public Administration (Ley Orgánica de la Administración Pública Federal) – which is part of the broader National Anti-corruption System, Mexico City’s draft legislation contains information on internal control and audit, and transparency. Article 3 of the draft law states: “The functions of auditing, internal control and other interventions shall be exercised under the principles of ethics, austerity, moderation, honesty, efficiency, effectiveness, economy, rationality, transparency, openness, accountability, citizen participation, accountability and will be executed in accordance with the guidelines that are issued for that purpose”. It would be beneficial to ensure that the related guidelines are consistent with the federal law and international better practices for internal control and audit activities, such as the “three lines of defence” model (outlined in the following section).

6.2. Establishing an effective internal control framework in Mexico City

6.2.1. Mexico City could draft a strategy for communications and capacity building to publicise the new guidelines for internal control, audits and interventions in public administration.

Mexico City has launched its own anti-corruption system through the Decree by which various provisions of the Organic Law of Public Administration of the Federal District are reformed and added (Decreto por el que se reforman y adicionan diversas disposiciones de la Ley Orgánica de la Administración Pública del Distrito Federal) published in the Official Gazette of Mexico City on 1 September, which gives the Comptroller-General of Mexico City (Contraloría General) a prominent role in internal control and audit as part of the anti‑corruption system. Officials indicated that they have already had some positive results from their internal control system, with some assets and funds recovered and the government using recovered funds for designated programmes.

Mexico City’s internal control framework is regulated by Articles 105, 106, 108 and 110-113 of the Internal Regulation of the Public Administration of the Federal District (Reglamento Interior de la Administración Pública del Distrito Federal) and includes both vertical and horizontal co-ordination mechanisms. The Internal Regulation provides for auditors from the Comptroller-General of Mexico City to be attached to municipal public institutions. Only 28 of the 45 government entities have internal control units, and half of these internal control units have a complaints division that performs audits, resolves complaints and substantiates administrative or disciplinary proceedings. The other 14 internal units transfer files to the Directorate of Legal Affairs and Responsibilities if they discover any administrative irregularities in performing audits. The 17 public entities with no internal control units are assisted by the Directorate of Internal Control Units in Entities (Dirección General de Contralorías Internas en Entidades) to which cases of administrative irregularities are handed off. The Comptroller-General of Mexico City undertakes and oversees internal audits in accordance with a range of standards and guidelines, as outlined in Annex 6.A.

Officials indicated that the internal control system is established separately in each agency. In September 2017, a decree was passed issuing the Law on Audit and Internal Control of the Public Administration of Mexico City (Ley de Auditoría y Control Interno de la Administración Pública de la Ciudad de México). This assigns responsibilities to designated officials in the executive branch for internal control, risk management, and corruption and fraud. The Law modifies the allocation of responsibilities. Section 5 of this bill requires Mexico City government entities to adopt an internal control system that includes plans, methods, principles, norms, procedures and mechanisms of verification and evaluation on internal control. The guidelines established for staff on how to execute these new legislative requirements appear to be clear and consistent. On 8 January 2018, the guidelines for Audit, Internal Control and Interventions of the Public Administration of Mexico City (Lineamientos de Auditoría, Control Interno y de las Intervenciones de la Administración Pública de la Ciudad de México) were published in the Official Gazette of Mexico City.

The purpose of the Audit Guidelines is to regulate the planning and execution of internal audits, and the deadlines, procedures and forms that must be observed in practice. They are mandatory for the Secretariat of the Office of the Comptroller-General of Mexico City and its administrative units when carrying out internal audits.

The Internal Control Guidelines regulate the activities for the implementation and application of internal control. It also establishes the functions, activities and operations as well as the techniques and methods to be used for internal control within the Secretariat of the General Comptroller’s Office of Mexico City and its administrative units, as well as in the delegations or mayor’s offices, dependencies, parastatal entities and decentralised bodies of the public administration.

Lastly, the Guidelines for the interventions of the Public Administration of Mexico City refer to the visits, inspections, advisory services and other activities requested by the Secretariat of the Comptroller-General’s Office or its administrative units for special reviews, verifications and operations.

6.3. Adopting the “three lines of defence” model

6.3.1. Mexico City could apply the principles of the “three lines of defence” model in refining the internal control framework.

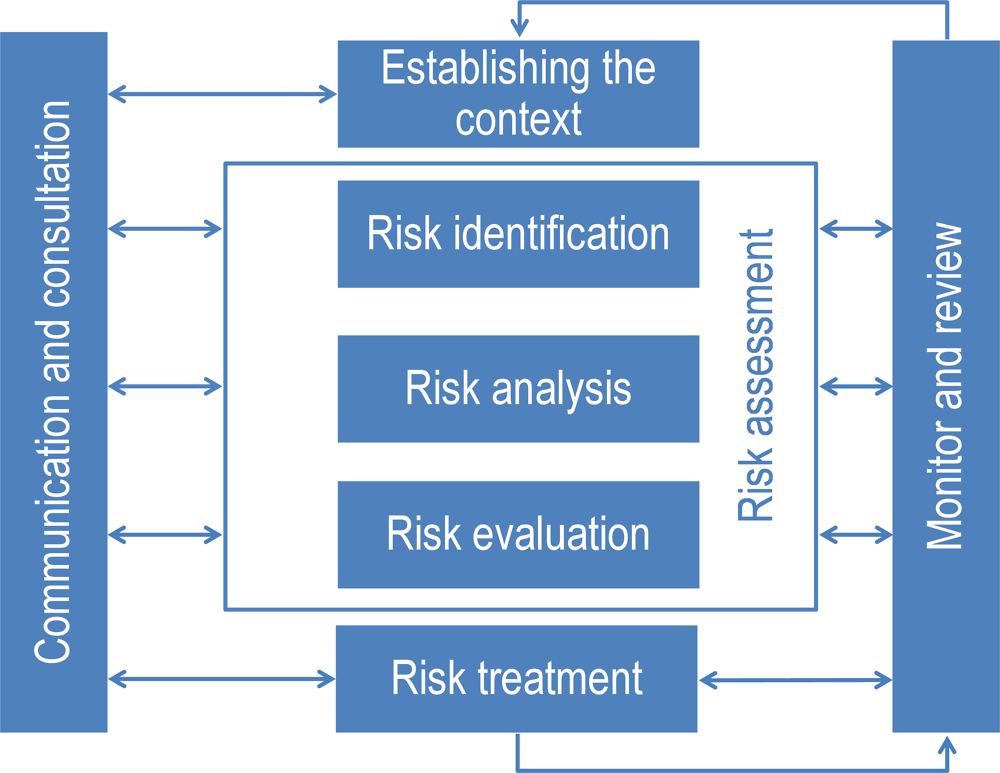

The leading fraud and corruption risk management models used in OECD member and partner countries stress that the primary responsibility for preventing and detecting corruption rests with the staff and management of public entities. Such corruption risk-management models often have similarities with the Institute of Internal Auditors’ (IIA) “Three Lines of Defence” Model (Figure 6.1).

Figure 6.1. The “Three Lines of Defence” Model

Source: IIA (2013), “IIA Position Paper: The Three Lines of Defense in Effective Risk Management and Control”, Institute of Internal Auditors, Altamont Springs, Florida, p. 2, https://na.theiia.org/standards-guidance/Public%20Documents/PP%20The%20Three%20Lines%20of%20Defense%20in%20Effective%20Risk%20Management%20and%20Control.pdf.

The first line of defence is operational management and personnel. Those on the frontline naturally serve as the first line of defence, because they are responsible for maintaining internal controls and for executing risk and control procedures on a daily basis. Operational management identifies, assesses, controls and mitigates risks, guiding the development of internal policies and procedures and ensuring that activities are consistent with goals and objectives.

Senior managers are primarily responsible for managing risk and implementing internal controls, but all officials in a public organisation – from the most senior to the most junior – can play a role in identifying risks and deficiencies and ensuring that internal controls address and mitigate these risks. Every staff member should be encouraged to help develop better systems and procedures that enhance the organisation’s integrity and help it to fight corruption.

The second line of defence includes the next level of management, those responsible for overseeing delivery. These are responsible for establishing a risk management framework, monitoring, identifying emerging risks, and regular reporting to senior executives. The third line of defence is the internal audit function. Its main role is to provide senior management with independent, objective assurance over the first and second lines of defence arrangements (IIA, 2013[2]).

The external audit office and external regulators provide additional layers of defence. Although not officially part of the three lines of defence model, they are essential elements of the overall accountability and anti-corruption framework in the public sector.

Mexico City has elements of the three lines of defence model in its framework, but responsibilities overlap and the lines of defence are blurred. The Comptroller-General, for example, is responsible for internal controls as well as conducting and reviewing internal audit reports. This blurs the lines of defence, since auditors should not be put in the position of auditing internal controls that they themselves have implemented – since this would present a conflict. Mexico City could consider applying the principles of the three lines of defence model as it refines its internal control framework. This would ensure that responsibilities are appropriately separated and that management takes greater ownership over the everyday implementation of internal controls and the management of risk. The evolution of the French internal control system, which focuses on managerial responsibility, may provide some useful insight, as illustrated in Box 6.1.

Box 6.1. The French internal control system: Basic elements

In 2006, the entry into force of the Organic Law Governing Budget Laws (La loi organique relative aux lois de finances) of 1 August 2001 offered an opportunity to rethink the management of public expenditure in France. It was accompanied by a shift in the role of the main actors involved in the control and management of public finance.

Goal-based public policy management, a results-oriented budget, a new system of responsibility, strengthened accountability and a new accounting system are the key features of the reform.

The Decree of 28 June 2011 on internal audits in the administration is the culmination of a decision to limit the risks the ministries incur in managing public policy. This reform has made it possible to extend the scope of internal control to all “professions” and functions in ministerial departments and to establish an effective internal audit policy in the government administration.

Effective governance of public management

The French system focuses on managerial responsibility. The programme manager is the central link of public management, and helps to integrate political responsibility, borne by the minister, and managerial responsibility, borne by the programme manager. Under the minister’s authority, programme managers are involved in drafting the strategic objectives of the programme they are responsible for: they guarantee operational implementation and undertake to fulfil the relevant objectives. The minister and the programme manager become accountable for the objectives and indicators specified in the Annual Performance Plans. These national objectives are adapted, if necessary, for each government service. The programme manager delegates the management of the programme by establishing operational programme budgets that are assigned to managers.

Source: (OECD, 2015[3]), “Budget reform before and after the global financial crisis,” 36th Annual OECD Senior Budget Officials Meeting, http://www.oecd.org/officialdocuments/publicdisplaydocumentpdf/?cote=GOV/PGC/SBO(2015)7&docLanguage=En;

(European Commission, 2014[4]), Compendium of the Public Internal Control Systems in the EU Member States (2nd ed), http://ec.europa.eu/budget/pic/lib/book/compendium/HTML/index.html (9 May 2017).

6.4. Establishing internal control measures

Internal control measures constitute checks and balances that are the responsibility of management and are carried out by staff on a daily basis. Internal controls include a wide range of processes and checks intended to ensure that employees and managers exercise their duties within parameters established by the government entity. The overall goal of internal control is to implement the internal rules and values of the organisation in accordance with senior management’s vision and for meeting the organisation’s strategic objectives.

Mexico City’s new law on audit and internal control, issued in September 2017, describes internal control (Article 29) as “the verification and evaluation process with a preventive approach and in accordance with the applicable legal norms, implemented to guarantee good administration and open government in the government entities of the Public Administration of Mexico City, concerning the activities, operations, actions, programmes, plans, projects, goals, institutional activities, application of human, material, financial and computer resources, as well as the administration of the information”. It stipulates that internal control will consist of five stages: planning, programming, checking, results and conclusion. Some additional clarification could be useful, to ensure that the internal control framework will include tangible everyday controls to prevent and detect potential fraudulent behaviour. Controls could include, for example: authorisation and approval procedures; spending limits; segregation of duties; reconciliations; system passwords; and ongoing monitoring and review.

6.4.1. Mexico City could create a system of accountability for procedural manuals to ensure they are consistent, regularly updated and reflect efficient procedures.

In Mexico City, each line ministry, delegation and government entity has its own procedure manuals, which are approved by senior management and registered with the Public Administration of the Federal District (Mexico City, 2014[5]) . The General Co-ordination of Administrative Modernisation (Coordinación General de Modernización Administrativa, CGMA) provides advice on the design of manuals and is responsible for determining if each manual meets basic requirements, but it does not provide oversight on the implementation (or regular update) of the manuals. Manuals are to be written in accordance with the state’s Technical Guide for the Manufacturing of Manuals of the Government of the Federal District, which provides guidance on content and formatting.

Senior management does not supervise the implementation of manuals. The implementation of manuals is thus not overseen except when they are subject to an audit. There was some indication that these manuals are created more to comply with requirements (and “protect” the government entity from negative findings if they were subject to an audit) than to serve as practical guidance for public officials.

Officials reported that they consider these procedure manuals to be a form of control, in that they outline the expected standardised procedures for key processes. However, they indicated that the manuals are complicated, contain irregularities and can make processes inefficient. They are not based on the government entity’s strategic vision, and they do not outline what should be done and why. Further, the manuals do not contain procedures for conducting risk assessments or undertaking internal control activities. As a result, the manuals are not systematically referred to for guidance in making key decisions. Mexico City could consider creating a system to ensure these manuals are consistent, are regularly updated and reflect efficient procedures.

6.5. Refining the role of Internal Control Units and strengthening the independence of the Comptroller-General

6.5.1. Mexico City could clearly separate the lines of defence, with senior management, rather than internal auditors, charged with implementing risk management and designing and implementing internal controls.

Internal audit (the third line of defence) serves as a key control to detect corruption, but its main purpose is to provide objective assurance that risk management and internal controls (the first and second lines of defence) are functioning properly. An effective internal audit function also ensures that internal control deficiencies are identified and communicated in a timely manner to those responsible. Internal audit is also a necessary ingredient for effective accountability and better management. It helps hold officials accountable for their actions and to report on performance and management gaps. Institutional responses to negative audit findings and integrity breaches may strongly influence the institutional culture, the tone at the top and the overall effectiveness of the internal control framework.

Mexico City’s internal control structures do not clearly align with the three lines of defence model, as the Comptroller-General of Mexico City is responsible for implementing internal controls as well as undertaking and reviewing internal audit reports. In addition, the Comptroller-General of Mexico City holds regular meetings with internal control units to review the progress of the implementation of the audit plan and of other matters falling under their responsibility. This structure blurs the distinctions between the lines of defence. International standards note that it is preferable that the first and second lines of defence do not involve the internal auditors (third line of defence).

Typically, there is a clear separation between the internal audit function (the third line of defence) and the second line of defence, which consists of management oversight functions to ensure that first line controls are properly designed, in place and operating as intended. When senior management considers that it is more efficient for internal audit to also perform risk management, compliance or other second line of defence functions, it becomes difficult to clearly separate second and third lines of defence.

To avoid institutional conflicts of interest in such cases, public organisations must set up appropriate safeguards to ensure the effectiveness of the internal audit function is not compromised. For instance, if the internal audit is involved in second line of defence activities, the task of providing assurance on these activities must be outsourced either externally or internally to other departments. The internal audit function should not assume any managerial responsibilities concerning the matter subject to the audit. In such cases, the internal audit can facilitate and support the responsible actors, but should not assume ownership.

Likewise, should internal auditors uncover irregularities that suggest corrupt or fraudulent activities, the case should be forwarded to qualified investigators, whose duties will be to assess whether such fraudulent or corrupt acts have indeed taken place. Once again, to avoid any institutional conflicts of interests and to reinforce the internal control framework, auditors should not be responsible for leading internal investigations.

In Mexico City, internal audits are generally conducted by auditors from the Comptroller-General’s office who are posted to government entities’ internal control units. Although most Mexico City ministries and delegations have an internal control unit, only 28 of the 45 government entities have one. The Comptroller-General aims to send an audit team at least annually to entities that do not have an internal control unit.

The Comptroller-General does not conduct performance audits, but internal audits include a second phase that looks at control effectiveness. Effectiveness is thus not assessed in a systematic way, but only in areas where there was reason to trigger traditional audits. However, there appears to be confusion between the concepts of compliance audits and audits seeking to measure effectiveness, since most examples given by Mexico City officials pertained to the former rather than to the latter.

Public officials indicated during interviews conducted that internal controllers have sometimes been considered to be strict, lacking in perspective and overly focused on the implementation of procedure manuals (which are often out of date). Controllers were also seen to be lacking in the softer skills required to advise public officials on ethical dilemmas and difficult situations. Further, the perception among staff is that if they seek guidance, there is a chance they could be audited or punished. Some of those interviewed suggested that another unit could perhaps be responsible for providing ethics advice and training. This group could collaborate with the Internal Control unit, but remain separate.

6.5.2. Given Comptroller-General Guidelines require that the audit programme be based on priorities and a risk assessment, Mexico City could develop and implement a risk-based approach to internal audit topic selection.

In November 2011, the Comptroller-General published audit guidelines: General Guidelines for the Planning, Preparation and Presentation of Audit Programmes of the General Office of the Federal District. The guidelines state that one of the priorities of the Public Administration of the Federal District is to have a public administration that is modern, technologically innovative, with the faculties and resources necessary to meet citizen demands with efficiency, simplicity and without excessive procedures. The guidelines also outline specific objectives for internal auditors, such as:

Develop audit programmes based on a proactive approach that integrates the results of the study on the objectives, priorities and needs of the government entity and the risk assessment and management, as well as strategic aspects dictated by the Comptroller-General;

Support government entities in innovation, improvement and administrative modernisation, as well as in the development and diffusion of internal control schemes;

Promote the achievement of institutional goals and objectives with efficiency, honesty and transparency and be a strategic contributor to the Public Administration of the District;

Promote training programmes for Internal Comptrollers, so that they have current knowledge that allows them to achieve high-quality interventions.

Audit plans are to be linked to the entities’ objectives and are prepared by internal control units in each ministry or delegation. Officials indicated that the majority of internal audits are triggered by citizens rather than following a risk-based planning system. They do, however, use four criteria to prioritise audits: importance; presence; amount of funds; and pertinence. Risk analysis and prioritisation is important in the internal audit planning process to ensure resources are allocated to areas of greatest need and to ensure the greatest impact.

The new Audit and Internal Control Law of Mexico City of 2017 contains more guidelines for audit planning. It includes (Article 22) that the planning stage will consider, among other things, “the importance and risk of the operations of the public entity audited”. It also provides (Article 8) for audits to be performed at any time determined by the Secretariat of the Comptroller-General or its administrative unit, independent of the times included in the annual audit programme. It is beneficial to give auditors this independence to adjust their audit plan, as this allows for more timely review if issues or challenges come to light.

Mexico City could consider the approach taken by Mexico’s Supreme Audit Institution (Auditoria Superior de la Federación, or ASF). ASF’s strategic and operational agility, including its capacity to manage a high volume of audits, relies in part on the effectiveness of its audit programming, which it calls, the “Annual Programme of Audits for the Public Account” (Programa Anual de Auditorías para la Fiscalización Superior de la Cuenta Pública, or PAAF). The PAAF is ASF’s methodological framework for identifying the audits it will conduct for the duration of one year. The PAAF’s audit-programming processes take into account a number of factors, such as ASF’s technical and managerial autonomy, the relative importance of audited entities, the variation in the amount allocated in relation to the previous public account, audit history, and complaint or requests from the Chamber of Deputies. It also involves consideration of available resources, types of audits to be conducted, and staff experience (OECD, 2017[6]).

Individual audit units in ASF propose audits or studies for inclusion in the programming process. The units have some flexibility to define their programming methodology according to the nature of their duties, but they must comply with the provisions of the overall methodological framework. The PAAF incorporates a risk assessment to identify and select audit priorities, which includes quantitative and qualitative methodologies for scoring risks based on 16 risk factors, and making risk-based comparisons to prioritise work. Effective risk-based audit programming can be a useful approach for audit institutions to direct audit resources to areas it deems to be most critical, based on a predetermined set of criteria. Risk-based audit programming can contribute not only to economical use of resources, but also to the evidence-based prioritisation of policy objectives and the effective use of tax revenue (OECD, 2017[6]), p. 32.

6.5.3. Mexico City could strengthen mechanisms for internal control units to monitor implementation of audit recommendations.

Internal auditors indicated that there are no mechanisms for following up on the implementation of recommendations or for ensuring that negative cases do not repeat themselves. Auditors also indicated that there were sometimes issues with government entities interfering with audit findings. Audit recommendations are only effective if they are implemented. The SAIs for other OECD member countries have methods for following-up recommendations. For example, the Australian National Audit Office (ANAO) conducts a selection of follow-up performance audits each year to assess government entities’ implementation of performance audit recommendations from previous years. Australian government entities also have Audit Committees that meet regularly to, among other things, monitor the implementation of audit recommendations, and the ANAO can attend these meetings as an observer and/or request the meeting minutes.

In Canada, the office of the Auditor General of British Columbia, a sub-national audit office, has published follow-up reports based on self-assessments from audited government entities and conducted follow-up audits on a selected number of them (Box 6.2). Mexico City could strengthen processes to allow for the follow-up of recommendations, such as through a selection of follow-up audits or by organising annual self-assessments.

Box 6.2. Office of the Auditor General of British Columbia: Following up Audit Recommendations

The Office of the Auditor General of British Columbia (OAG) published a report, Follow-Up Report: Updates on the Implementation of Recommendations from Recent Reports, in June 2014. According to the then Auditor General of British Columbia, it was critical that the OAG follow up on the recommendations to ensure that citizens receive full value for money from the OAG’s work, because the recommendations identify areas where government entities can become more effective and efficient.

The OAG then published a follow-up report including self-assessment forms completed by audited government entities. These forms were published unedited and were not audited. The June 2014 report contained 18 self-assessments, two of which reported that the entity had fully or substantially addressed all of the recommendations in their reports.

The OAG also followed up on its recommendations by auditing four self-assessments to verify their accuracy. The OAG found that in almost all cases, government entities had accurately portrayed the progress that they had made to implement the recommendations. While it sometimes found that recommendations were partially rather than fully or substantially implemented as self-reported, the discrepancy usually resulted from a difference in understanding of what fully or substantially implemented meant. In those cases, the OAG worked with the ministries and agencies to clarify expectations and reach agreement on the status of the implementation.

Source: OAG (2014[7]), Follow-Up Report: Updates on the Implementation of Recommendations from Recent Reports, Office of the Auditor General of British Columbia, June, http://www.bcauditor.com/sites/default/files/publications/2014/report_19/report/OAGBC%20Follow-up%20Report_FINAL.pdf.

6.5.4. Mexico City could revise the audit planning process for the Comptroller-General to help increase its independence from the government.

The Office of the Comptroller-General is responsible for the audit, evaluation and control of the public management of the dependencies, delegations and government entities of the Government of Mexico City. The Comptroller-General sits within the organisation structure for the state-level Audit Office (Auditoría Superior de la Ciudad de México) and is appointed by the Head of Government, with the appointment ratified by the Legislative Assembly. The Comptroller-General does not have full independence to determine his own priorities and internal audit work plans. Greater independence would give the Comptroller-General greater credibility, which would, in turn, promote better outcomes.

The Mexican Institute for Competitiveness (IMCO) and the Centre for Economic and Administrative Sciences of the University of Guadalajara (CUCEA) found that lack of autonomy is a weakness among superior state audit offices in Mexico. OECD’s work with supreme audit institutions (SAIs) helps to illustrate one of the practical effects that this lack of independence has on accountability. In a survey of ten leading SAIs, OECD explored ways in which SAIs contribute to the policy cycle, including formulation, implementation and evaluation of policies and programmes. The findings suggest that SAIs require autonomy and flexibility to engage across the policy cycle at their own discretion (OECD, 2016[8]). Applying this to Mexico, external factors that limit the independence of audit offices are likely to result in less extensive contributions to policies and programmes, and therefore to limit the uptake of their work by the executive branch.

The International Organization of Supreme Audit Institutions (INTOSAI) has published a number of documents – including INTOSAI GOV 9100: Guidelines for Internal Control Standards for the Public Sector – that stress the importance of independence for internal and external auditors (see Box 6.3).

Box 6.3. International standards for ensuring independence of audit institutions

Ensuring audit institutions are free from undue influence is essential to ensure the objectiveness and legitimacy of their work, and principles of independence are therefore embodied in the most fundamental standards concerning public sector audit. The International Organization of Supreme Audit Institutions (INTOSAI), for example, has two fundamental declarations citing the importance of independence. Specifically the “Lima Declaration of Guidelines on Auditing Precepts” and the “Mexico Declaration on SAI Independence” draw attention to the importance of organisational, functional and administrative dimensions of independence (INTOSAI, 1977[9]; INTOSAI, 2007[10]).

Organisational independence is closely related with the SAI leadership – i.e. the SAI head or members of collegial institutions – including security of tenure and legal immunity in the normal discharge of their duties.

Functional independence requires that SAIs have a sufficiently broad mandate and full discretion in the discharge of their assignments, including sufficient access to information and powers of investigation. Functional independence also requires that SAIs have the freedom to plan audit work, to decide on the content and timing of audit reports and to publish and disseminate them.

Administrative independence requires that SAIs be provided with appropriate human, material and monetary resources as well as the autonomy to use these resources as they see fit.

Independence is equally important for internal audit institutions. INTOSAI GOV 9100: Guidelines for Internal Control Standards for the Public Sector and INTOSAI GOV 9120 – Internal Control: Providing a Foundation for Accountability in Government (which includes a checklist), both stress the importance of the independence of internal auditors from an organisation’s management: “for an internal audit function to be effective, it is essential that the internal audit staff be independent from management, work in an unbiased, correct and honest way and that they report directly to the highest level of authority within the organisation (INTOSAI, 2010[11]; INTOSAI, 2001[12]). This allows the internal auditors to present unbiased opinions on their assessments of internal control and objectively present proposals aimed at correcting the revealed shortcomings”.

More specific guidelines with respect to independence are provided in INTOSAI GOV 9140: Internal Audit Independence in the Public Sector, which adopt principles from ISSAI 1610: Using the Work of Internal Auditors) in defining independence (INTOSAI, 2010[13]). Criteria outlined in both documents include whether the internal audit institution is established by legislation or regulation, is accountable and reports directly to top management and has access to those charged with governance, is located organisationally outside the staff and management function and has responsibilities segregated from management, has clear and formally defined responsibilities, has adequate payment and grading, adequate freedom in developing audit plans, and is involved in the recruitment of its own audit staff.

Sources: International Organization of Supreme Audit Institutions: (INTOSAI, 2010[13]; INTOSAI, 2010[11]; INTOSAI, 2007[10]; INTOSAI, 1977[9]; INTOSAI, 2001[12]).

6.6. Implementing a risk management framework

6.6.1. Mexico City could implement a systematic risk management framework to strengthen the internal control framework.

Mexico City’s framework and supporting legislation, which was valid until 1 September 2017, did not include a systematic risk management strategy, an essential element of the second line of defence and of an effective internal control framework – particularly in relation to combating fraud and corruption. The Public Administration's Internal Control Guidelines (Lineamientos de Control Interno de la Administración Pública de la CDMX), issued on 8 January 2018, created a risk management system. Its implementation will be challenging for Mexico City and will require political commitment from senior management of the units.

Good governance practices among OECD countries indicate that risk management must be considered an integral part of the institutional management framework rather than managed in isolation. Risk management should permeate the organisation’s culture and activities in such a way that it becomes the business of everyone within the organisation.

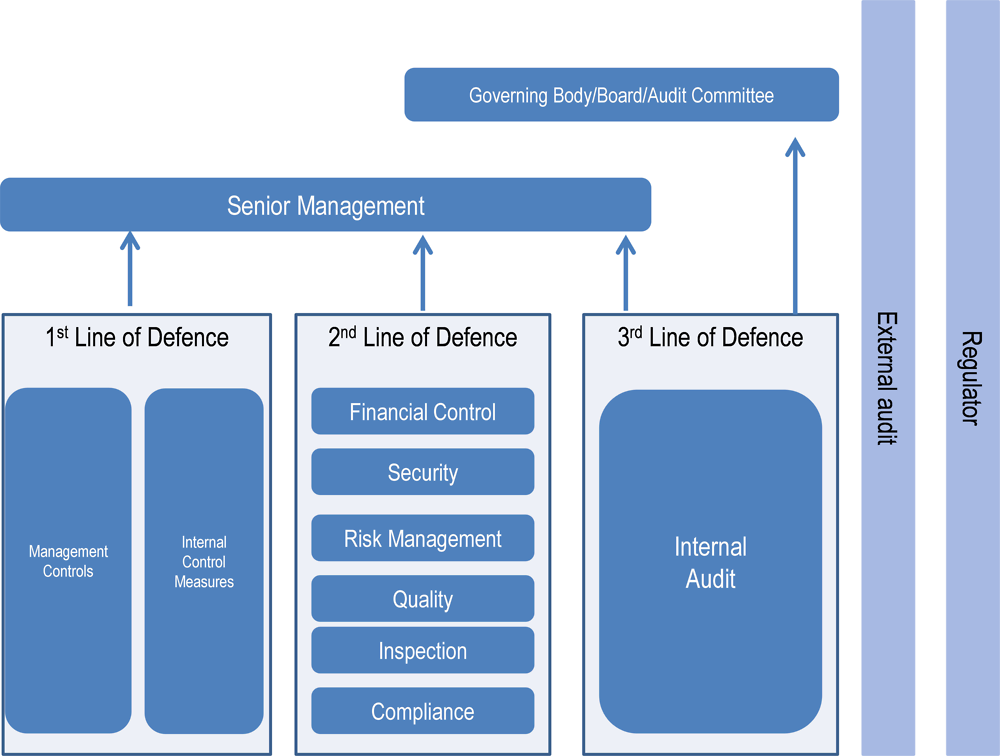

Operational risk management begins with establishing the context and setting an organisation’s objectives. It continues by identifying events that might have an impact on reaching them. Events with a potentially negative impact represent risks. Risk assessment is a three-step process that starts with risk identification and is followed by risk analysis, which involves developing an understanding of each risk, its consequences, the likelihood of those consequences, and the severity of the risk. The third step is risk evaluation, which involves determining the tolerability of each risk and whether the risk should be accepted or treated. Risk treatment is the process of adjusting existing internal controls, or developing and implementing new controls, to reduce the severity of the risk to a tolerable level (Figure 6.2).

Figure 6.2. Risk management cycle according to ISO 31000:2009

The process of establishing context and assessing and treating risk is linear, while communication and consultation, monitoring, and reviewing are continuous. Monitoring and reviewing helps identify new risks and reassess existing ones when there are changes in the organisation’s objectives or in its internal and external environment. This involves scanning for possible new risks and learning lessons about risks and controls from an analysis of successes and failures (OECD, 2013[15]).

An effective risk management framework is essential to managing public fraud and corruption. The US Government Accountability Office (GAO) has established a risk management framework for managing fraud risks in federal programmes. Its practical ongoing practices and activities are outlined in Box 6.4.

Box 6.4. Fraud and corruption risk management framework in the United States

The United States’ Government Accountability Office (GAO) has developed a framework for managing fraud risks in federal programmes. It includes control activities, as well as structures and environmental factors that help managers mitigate fraud risks. The framework includes four components for effectively managing fraud risks.

1. Commit to combating fraud by creating an organisational culture and structure conducive to fraud risk management.

Demonstrate senior-level commitment to combat fraud and involve all levels of the programme in setting a tone that does not tolerate fraud.

Designate a government entity within the programme office to lead fraud risk management activities.

Ensure the government entity has defined responsibilities and the necessary authority to serve its role.

2. Assess: Plan regular fraud risk assessments and assess risks to determine a fraud risk profile.

Tailor the fraud risk assessment to the programme, and involve relevant stakeholders.

Assess the likelihood and impact of fraud risks and determine risk tolerance.

Examine the suitability of existing controls, prioritise residual risks, and document a fraud risk profile.

3. Design and implement a strategy with specific control activities to mitigate assessed fraud risks and collaborate to ensure effective implementation.

Develop, document and communicate an antifraud strategy, focusing on preventive control activities.

Consider the benefits and costs of controls to prevent and detect potential fraud, and develop a fraud response plan.

Establish collaborative relationships with stakeholders and create incentives to help ensure effective implementation of the anti-fraud strategy.

4. Evaluate and adapt: Evaluate outcomes using a risk-based approach and adapt activities to improve fraud risk management.

Conduct risk-based monitoring and evaluation of fraud risk management activities, with a focus on outcome measurement.

Collect and analyse data from reporting mechanisms and instances of detected fraud for real-time monitoring of fraud trends.

Use the results of monitoring, evaluations and investigations to improve fraud prevention, detection and response.

As outlined under each of these components, ongoing practices and activities can help an organisation maintain the monitoring and feedback mechanisms and ensure that the framework remains dynamic and staff remain engaged in the processes.

Source: (Government Accountability Office (GAO), 2015[16]), A Framework for Managing Fraud Risks in Federal Programs, Washington, Government Accountability Office 15-593SP, http://www.gao.gov/products/GAO-15-593SP.

6.6.2. Mexico City could set up the risk management framework by assigning clear responsibility for managing risk to senior managers, providing risk management training for staff and updating risk management systems, tools and processes.

After a risk management framework is developed, it needs to be put into effect. Appropriate and accurate risk management information needs to be collected, senior management need to be assigned clear responsibility for the ongoing management and monitoring of risk, and all staff need to be aware of the risk management framework and how to incorporate risk management into daily work and decision-making.

Appropriate and accurate risk information is essential for operating a risk management framework. Without it, effectively assessing, monitoring and mitigating risk would be difficult. Information to support risk management can derive from a number of internal and external sources, depending on the programme or area of work. A consistent approach to sourcing, recording and storing risk information will improve the reliability and accuracy of the information needed.

For a risk management framework to function effectively, responsibility for specific risks needs to be clearly assigned to the appropriate senior managers. These managers need to take ownership of the risks that could affect their institutional objectives, use risk information to inform decision-making and actively monitor and manage their assigned risks. These managers should also be held accountable to the executive through regular reporting on risk management, including on successes, lessons learned and areas that could be improved.

Staff should be made aware of the risk management framework and key requirements through training and awareness-raising activities. Communication and consultation with staff is also a key step towards securing input in the risk management process and giving them ownership of the outputs of risk management. Informed employees who can recognise and deal with corruption risks are more likely to identify situations that can undermine the achievement of institutional objectives. Australia has developed guidance on building risk management capability in government entities, which provides useful insights (Box 6.5).

Box 6.5. Building Risk Management Capability: Australian government

The Australian Federal Department of Finance has developed guidance for government officials on how to build risk management capability in their government entities. The guidance indicates that entities should consider each of the areas outlined below to determine where improvements may be made to their risk capability.

People capability – A consistent and effective approach to risk management is a result of well skilled, trained and adequately resourced staff. All staff have a role to play in the management of risk. Therefore, it is important that staff at all levels of the government entity have clearly articulated and well communicated roles and responsibilities, access to relevant and up-to-date risk information, and the opportunity to build competency through formal and informal learning and development programmes. Building the risk capability of staff is an ongoing process. With the right information and learning and development, an entity can build a culture among its staff that is cognizant of risk and can improve the understanding and management of risk across the entity. Considerations include:

Are risk roles and responsibilities explicitly detailed in job descriptions?

Have you determined the current risk management competency levels and completed a needs analysis to identify learning needs?

Do induction programmes incorporate an introduction to risk management for all levels of staff?

Is there a learning and development programme that incorporates ongoing risk management training tailored to the government entity’s different roles and levels?

Managing risk information – Successfully assessing, monitoring and treating risks across the government entity is dependent on the quality, accuracy and availability of risk information and supporting documentation. A consistent approach to the sourcing, recording and storage of information will improve the reliability and availability of information required by different audiences. Considerations include:

Have you identified the data sources to provide you with the necessary information for a complete view of risk across the government entity?

What is the frequency of collating risk information for delivery to different audiences across the government entity?

Do you have readily available risk information accessible to all staff?

How would you rate the integrity and accuracy of the available data?

Risk management processes – The effective documentation and communication of the risk management processes that support the government entities’ approach to managing risk will provide a consistent approach to risk management and allow for clear, concise and frequent presentation of risk information to support decision making. Considerations include:

When was the last time your risk processes were reviewed?

Are your risk management processes well documented and available to all staff?

Are your risk management processes aligned with your risk management framework?

Is there training available, tailored to different audiences, in the use of your risk processes?

Source: (Australian Government Department of Finance, 2016[17]), “Building risk management capability”, https://www.finance.gov.au/sites/default/files/comcover-information-sheet-building-risk-management-capability.pdf.

6.7. Reinforcing the professionalism of internal auditors

6.7.1. Mexico City could provide further training on ethics and integrity for internal auditors.

Internal auditors also play a key role in reinforcing a culture of integrity and accountability in the organisation. They act as agents of change, assessing the control environment as part of their assurance mandate, and motivating management to address flaws and inefficiencies in the effectiveness and the maturity of the control environment.

A key element for maintaining an effective internal control environment is ensuring the merit, professionalism, stability and continuity of audit staff. Public entities should develop mechanisms to attract, develop and retain competent individuals with the right set of skills and ethical commitment to work in the control and audit area. Training, certification and the improvement of auditing and investigative competences help enhance the effectiveness of the third line of defence, as it reinforces the credibility of the auditor.

The new Law of Audit and Internal Control for the Public Administration of Mexico City, issued on 1 September 2017, provides for a certification process for internal controllers, as well as for specific conditions that such officials should meet (Articles 16-17). Moreover, the Comptroller-General provides that a number of training activities on ethics, integrity and conflict of interest were undertaken by the School of Public Administration (see Chapter 3). The content of the training courses offered to public officials does refer to ethics, but it is often more theoretical than practical. Courses that provide more examples and are tailored to the specific responsibilities of public officials would strengthen the overall awareness-raising strategy. Higher-level efforts to address the issue of weak professional expertise and capacity of internal comptrollers could include developing customised training modules in co-operation with the National School of Public Administration, training centres located in relevant ministries, audit institutions, professional associations and universities.

The Comptroller-General and internal controllers provide some training to operational staff. They conduct some ethics awareness-raising activities (although there is no legislative requirement to do so) and are available to provide public servants with guidance and advice. However, as noted, staff have the perception seeking guidance might expose them to audit or punishment. It would thus be convenient for this function to be carried out by a unit responsible for advising them to prevent conflict of interest and corrupt acts from arising.

The Comptroller-General (in particular, the Dirección de Coordinación general de Evaluación y Desarrollo Profesional) emphasises induction training and contacts government entities to ensure that training has been organised to raise the awareness of new staff of ethics, conflict of interest, security and integrity. Some officials indicated that these training materials are often out of date. The level of training provided varies from entity to entity and is dependent on the initiative of the local internal controller.

Proposals for action

Mexico City has launched its own anti-corruption system and instituted a number of elements of an internal control and risk management framework. However, more could be done to strengthen and build capacity in the internal control and risk management environment. Specific proposals for action that Mexico City could consider undertaking are outlined below.

Establishing an effective internal control framework

Mexico City could draft a strategy for communications and capacity building to publicise the new guidelines for internal control, audits, and interventions in the public administration.

Adopting the “three lines of defence” model

Mexico City could apply the principles of the “three lines of defence” model in refining the internal control framework.

Establishing internal control measures

Mexico City could create a system of accountability for procedural manuals to ensure they are consistent, regularly updated and reflect efficient procedures.

Refining the role of Internal Control Units and strengthening the independence of the Comptroller-General

Mexico City could clearly separate the lines of defence, with senior management, rather than the internal auditors, charged with implementing risk management and designing and implementing internal controls.

Given that Comptroller-General guidelines require that the audit programme be based on priorities and a risk assessment, Mexico City could develop and implement a risk-based approach to internal audit topic selection.

Mexico City could strengthen mechanisms for internal control units to monitor implementation of audit recommendations.

Mexico City could revise the audit planning process for the Comptroller-General to help ensure greater independence from the government.

Implementing a risk management framework

Mexico City could implement a systematic risk management framework to strengthen internal control.

Mexico City could set up the risk management framework by assigning clear responsibility for managing risk to senior managers, providing risk management training for staff and updating risk management systems, tools and processes.

Reinforcing the professionalism of internal auditors

Mexico City could provide further training on ethics and integrity for internal auditors.

References

[17] Australian Government Department of Finance (2016), Building Risk Management Capability, https://www.finance.gov.au/sites/default/files/comcover-information-sheet-building-risk-management-capability.pdf.

[4] European Commission (2014), Compendium of the Public Internal Control Systems in the EU Member States (second edition), http://ec.europa.eu/budget/pic/lib/book/compendium/HTML/index.html (accessed on 09 May 2017).

[16] Government Accountability Office (GAO) (2015), A Framework for Managing Fraud Risks in Federal Programs, https://www.gao.gov/products/GAO-15-593SP.

[2] IIA (2013), IIA Position Paper: The Three Lines of Defense in Effective Risk Management and Control, https://na.theiia.org/standards-guidance/Public%20Documents/PP%20The%20Three%20Lines%20of%20Defense%20in%20Effective%20Risk%20Management%20and%20Control.pdf.

[11] INTOSAI (2010), GOV 9100 – Guidelines for Internal Control Standards for the Public Sector, International Organization of Supreme Audit Institutions, Copenhagen, http://www.intosai.org/issai-executive-summaries/view/article/intosai-gov-9100-guidelines-for-internal-control-standards-for-the-public-sector.html.

[13] INTOSAI (2010), GOV 9140 – Internal Audit Independence in the Public Sector, International Organization of Supreme Audit Institutions, Copenhagen, http://www.intosai.org/issai-executive-summaries/view/article/intosai-gov-9140-internal-audit-independence-in-the-public-sector.html.

[10] INTOSAI (2007), “Mexico Declaration on SAI Independence”, International Standards of Supreme Audit Institutions (ISSAI), No. 10, INTOSAI Professional Standard Committee Secretariat, Copenhagen, http://www.issai.org.

[12] INTOSAI (2001), GOV 9120 – Internal Control: Providing a Foundation for Accountability in Government, International Organization of Supreme Audit Institutions, Copenhagen, http://www.intosai.org/en/issai-executive-summaries/detail/detail/News/intosai-gov-9120-internal-control-providing-a-foundation-for-accountability-in-government.html.

[9] INTOSAI (1977), “Lima Declaration of Guidelines on Auditing Precepts”, International Standards of Supreme Audit Institutions (ISSAI), No. 1, INTOSAI Professional Standard Committee Secretariat, Copenhagen, http://www.issai.org.

[14] ISO (2009), ISO 31000-2009 Risk Management, https://www.iso.org/iso-31000-risk-management.html.

[5] Mexico City (2014), Lineamientos generales para el registro de manuales administrativos y específicos de operación de la administración pública del distrito federal el 30 de diciembre de 2014, Publicado en la gaceta oficial del distrito federa, http://cgservicios.df.gob.mx/prontuario/vigente/5393.pdf (accessed on 12 October 2018).

[6] OECD (2017), Mexico's National Auditing System: Strengthening Accountable Governance, OECD Public Governance Reviews, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264264748-en.

[1] OECD (2017), OECD Recommendation of the Council on Public Integrity, http://www.oecd.org/gov/ethics/Recommendation-Public-Integrity.pdf.

[8] OECD (2016), Supreme Audit Institutions and Good Governance: Oversight, Insight and Foresight, OECD Public Governance Reviews, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264263871-en.

[3] OECD (2015), Budget reform before and after the global financial crisis: 36th Annual OECD Senior Budget Officials Meeting, http://www.oecd.org/officialdocuments/publicdisplaydocumentpdf/?cote=GOV/PGC/SBO(2015)7&docLanguage=En.

[15] OECD (2013), OECD Integrity Review of Italy: Reinforcing Public Sector Integrity, Restoring Trust for Sustainable Growth, OECD Public Governance Reviews, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264193819-en.

[7] Office of the Auditor General of British Columbia (2014), Follow-Up Report: Updates on the Implementation of Recommendations from Recent Reports, http://www.bcauditor.com/sites/default/files/publications/2014/report_19/report/OAGBC%20Follow-up%20Report_FINAL.pdf.

Annex 6.A. Mexico City’s Standards and Guidelines for Internal Audit and Control

The Comptroller-General of Mexico City must implement internal controls and review the audit reports prepared by internal control and audit bodies in accordance with a range of standards and guidelines, as outlined below.

|

Document Title |

Title in English |

|

|---|---|---|

|

1 |

Normas Generales de Auditoría de la Contraloría General |

General Auditing Standards of the General Comptroller-General’s Office |

|

2 |

Lineamientos Generales para la Planeación, Elaboración y Presentación de Programas de Auditoría |

General Guidelines for Planning, Preparation and Presentation of Audit Programmes |

|

3 |

Lineamientos Generales para las Intervenciones 2010 |

General Guidelines for Interventions, 2010 |

|

4 |

Lineamientos para la Supervisión de Auditorías y Revisiones que ordena la Contraloría General |

Guidelines for the Supervision of Audits and Reviews ordered by the Comptroller-General |

|

5 |

Lineamientos para la Atención de Quejas, Denuncias y la promoción de Financiamiento de Responsabilidad Administrativa derivado de Auditorías |

Guidelines for Complaints, Denunciations and the Promotion of Administrative Responsibility Financing Derived from Audits |

|

6 |

Acuerdo por el que se emiten lineamentos en material de control interno para el ejercicio de recursos federales que se apliquen en la administración pública de la Ciudad de México |

Agreement for the issuance of guidelines on internal control and the use of federal resources for Mexico City’s public service |

|

7 |

Acuerdo por el que se emiten lineamentos en material de control interno para la administración pública de la Ciudad de México |

Agreement for the issuance of guidelines on internal control for Mexico City’s public service |