There is a general consensus among policy makers that an open organisational culture is needed to promote integrity, encourage transparency and detect misconduct. An open organisational culture empowers employees to voice their concerns and to feel comfortable to discuss ethical dilemmas, integrity concerns or errors freely. This allows public officials to feel comfortable to report misconduct. This chapter proposes a set of actions for consideration to create an open organisational culture in the public sector entities in Mexico City. In addition, this chapter recommends that Mexico City enact a dedicated whistle-blower protection law to encourage public officials to report misconduct.

OECD Integrity Review of Mexico City

Chapter 4. Creating an open organisational culture in the public sector in Mexico City

Abstract

The statistical data for Israel are supplied by and under the responsibility of the relevant Israeli authorities. The use of such data by the OECD is without prejudice to the status of the Golan Heights, East Jerusalem and Israeli settlements in the West Bank under the terms of international law.

4.1. Introduction

A key component of a culture of integrity in the public sector is the development and promotion of an open organisational culture. An open organisational culture engages employees and helps them develop and improve their work environment. Moreover, it is one in which employees see their ideas being acted upon. In turn, open communication and commitment to organisational values by management creates a safe and encouraging environment where employees can voice their opinions, and feel comfortable freely discussing ethical dilemmas, integrity concerns and errors.

Creating an open organisational culture has three main benefits: Firstly, it can build trust in the organisation. Secondly, it can cultivate pride of ownership and motivation, which increases efficiency (Martins and Terblanche, 2003[1]). Thirdly, in such cultures, problems can be addressed before they become potentially damaging risks and the perception of informing on other people, in discussing integrity concerns, is reduced. However, even in the most open organisational cultures, employees do not always feel comfortable enough to report integrity violations. A clear whistle-blowing policy and legal framework is crucial to enable employees to report suspected violations of integrity standards as a last port of call.

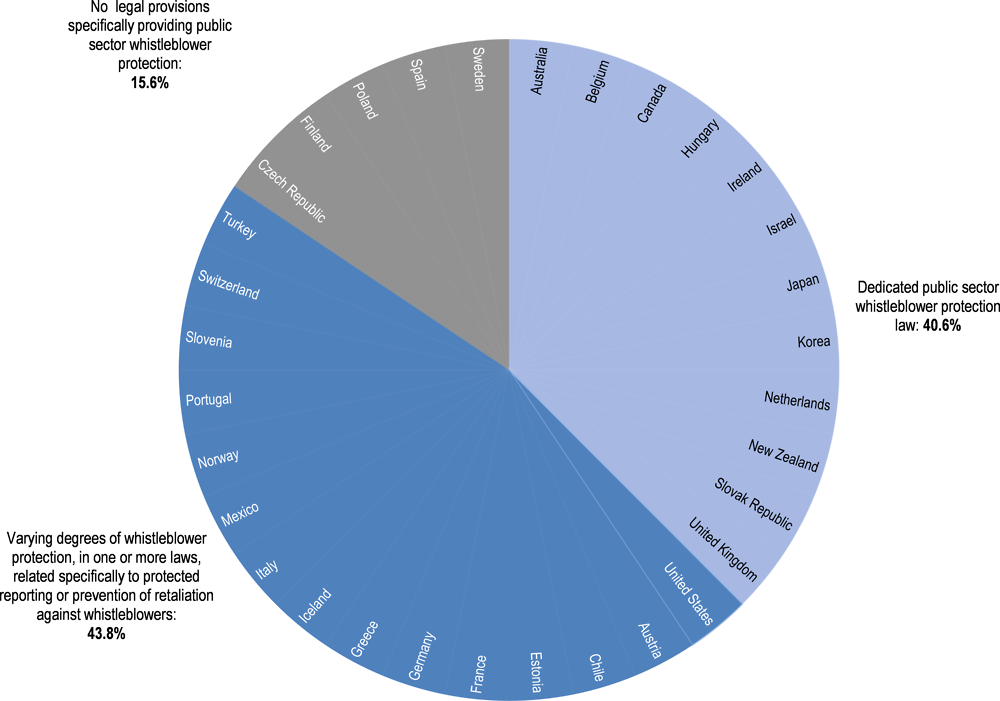

Measures supporting an open organisational culture responsive to integrity operate on several dimensions: engagement, credibility/trust, empowerment and courage (Figure 4.1). These can be addressed by organisational measures encouraging an open-door culture, by promoting trust and by setting the right example from top management. Whistle-blower protection legislation with clear guidance on reporting procedures and criteria for investigation can facilitate the reporting of misconduct, fraud and corruption. The right combination of all these measures promotes a culture of accountability and integrity.

Figure 4.1. Dimensions of an open organisational culture

Source: Adapted from (Berry, 2004[2]): “Organizational culture: A Framework and Strategies for Facilitating Employee Whistle-blowing”, Employee Responsibilities and Rights Journal, Vol. 16/I, pp. 1-12.

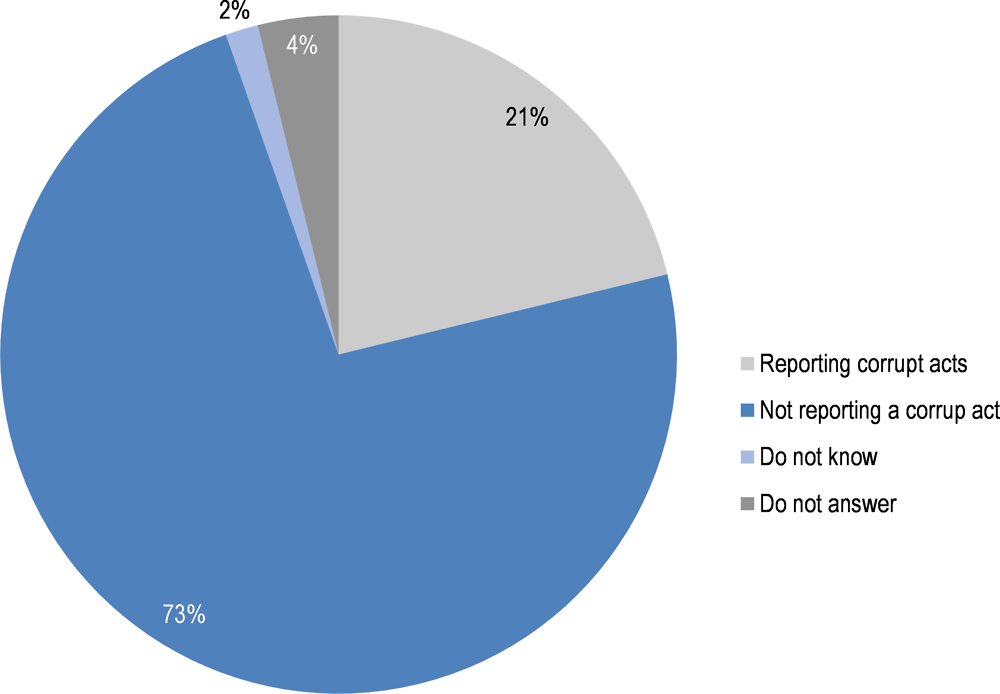

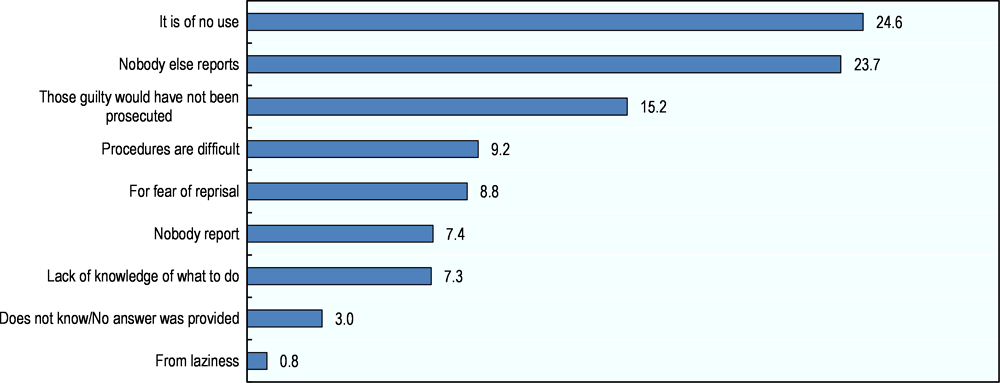

In Mexico City, 95% of citizens think of corruption as a frequent occurrence (INEGI (Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía), 2015[3]) . Given this high perception of corruption across all levels of government, it can be assumed that public officials and citizens alike do not feel confident to report corruption or other integrity violations, for fear of reprisal and the assumption that their reports will not be followed up. Indeed, only 21% of Mexicans reported acts of corruption in the past year (Figure 4.2). The main reason for not reporting acts of corruption in Mexico City and the state of Mexico is that, as survey participants report, it “is of no use” (24.6%), followed by a sense that they do not have the proof to confirm these acts (23.7%). In addition, many individuals dare not speak up out of fear and threats of reprisal (Figure 4.3). Interviews conducted for this Integrity Review show a similar picture throughout the public service in Mexico City, which show that the government entities’ degree of openness is limited.

Figure 4.2. Percentage of victims who report corruption

Source: (Marván Laborde, 2015[4]), La corrupción en México: Percepción, prácticas y sentido ético, Encuesta Nacional de Corrupción y Cultura de la Legalidad, Colección Los mexicanos vistos por sí mismos- Los grandes temas nacionales 24, Universidad Autónoma de Méxicohttp://www.losmexicanos.unam.mx/corrupcionyculturadelalegalidad/libro/index.html (accessed 14 June 2017), p.140.

Figure 4.3. Reasons for not reporting corruption

Source: (Marván Laborde, 2015[4]), La corrupción en México: Percepción, prácticas y sentido ético, Encuesta Nacional de Corrupción y Cultura de la Legalidad, Colección Los mexicanos vistos por sí mismos- Los grandes temas nacionales 24, Universidad Autónoma de México, http://www.losmexicanos.unam.mx/corrupcionyculturadelalegalidad/libro/index.html (accessed 14 June 2017), p. 140.

4.2. Encouraging an open organisational culture

4.2.1. To ensure that senior management act as role models, integrity could be included as a performance indicator to incentivise the application of the Code of Ethics.

Open organisational culture has a direct link to organisational vision, values and behaviour. Senior civil servants exemplify and transmit public service and organisational values. Staff compares leadership behaviour and beliefs embedded in the organisational culture with desirable behaviour under the formal policies and procedures. By translating the values in the code of conduct and acting accordingly, the leadership builds credibility in the norms and standards. Their consistent application demonstrates the value of ethical behaviour, clarifies standards and models openness. Above all, it can build trust in the processes. If they trust in their superiors, it is more likely that employees will be confident enough to report any integrity concerns or ethical dilemmas to their managers (Brown, Treviño and Harrison, 2005[5]).

Mexico City has not yet introduced measures to incentivise the implementation and consistent application of the code of ethics in the public administration (see Chapter 3). It could therefore consider incorporating integrity and public ethics as a formal assessment criterion for senior management. Aligning leadership behaviour with formal policies and promoting consistent modelling of values encourages credibility. This personal commitment to organisational values strengthens trust and creates a safe environment where employees can discuss integrity concerns and report any suspected violation internally (Berry, 2004[2]). For example, performance objectives could focus on the means as well as the ends, by asking not only if the performance objectives have been achieved, but how the public official achieved the objectives. If they are achieved by adhering to the highest standards of integrity, this should be recognised. Special recognition could be given to public officials who consistently engage in meritorious behaviour or help build a climate of integrity in their department. This might, for example, consist in identifying new processes or procedures that promote the ethics code (OECD, 2017[6]).

4.2.2. To encourage public officials to voice their concerns about integrity, the Comptroller’s Office could engage senior public officials to provide guidance, advice and counsel.

The openness of an organisation depends on the extent to which ethical issues, for example ethical dilemmas and suspicions about violations of integrity, can be discussed internally. Feeling free to discuss ethical concerns and potential wrongdoing freely means that the barriers to communication have been overcome. In organisations where a ‘‘code of silence’’ (Rothwell and Baldwin, 2007[7]) prevails, employees believe that speaking up is undesirable (Near and Miceli, 1985[8]). However, in organisations where dialogue and feedback are appreciated by management, the willingness of employees to discuss and report suspected misconduct internally is greater (Heard, E. and Miller, W., 2006[9]). An open-door policy by management to provide advice and counsel for public servants on ethical dilemmas and potential conflicts of interest can help increase the perception that the organisation is open.

However, high staff turnover, lack of guidance and a weak tone from the top are impediments to an open organisational culture. When staff rotation is high, less importance may be placed on strong ethical standards in the workplace, because employees are not employed long enough to apply these measures in practice. Generally, senior civil servants set the prevailing tone of an organisational culture (OECD, 2016[10]). In Mexico City, this presents a particular challenge, given the higher turnover and the fact that fewer officials are part of the civil service regime (OECD, 2017[11]). Longevity, continuity and institutional memory can help promote an appreciation of and collective commitment to substance, content and an ethics-oriented workplace that ensures respect of integrity every day.

In addition to advising employees on ethical challenges, management also needs to listen and act upon employees’ suggestions for improving processes and reports of misconduct. Entrenched hierarchical status and wide power differentials can lead to an environment in which management neither listens to nor acts on reports of misconduct (John Cuellar and John, 2009[12]). Ensuring that managers are responsive to employees’ concerns and creating space for alternative perspectives can instil courage (Berry, 2004[2]). To increase employees’ willingness to seek advice, managers should also be instructed to acknowledge errors and to turn negatives into lessons learned for future projects. This way, employees will not be afraid to approach management with their concerns for fear of punishment.

As a result, many OECD countries focus on senior civil servants to create an open organisational culture. Guidance in the form of advice and counsel for public servants to resolve ethical dilemmas at work and potential conflict-of-interest situations can be provided by immediate hierarchical superiors and managers or dedicated individuals available either in person, over the phone, via email or through special central agencies or commissions. Similarly, guidance, advice and counselling can be provided by senior officials, as in Canada (Box 4.1.). In turn, senior officials can issue guidance on how to react in situations that are ethically challenging and can communicate the importance of these elements as a means of safeguarding public sector integrity.

In Mexico City, on-site interviews revealed an apparently closed organisational culture. Employees express a marked reluctance to report any misconduct to their superiors or to other authorities, thanks to previous bad experiences and a lack of trust. The Comptroller’s Office (Contraloría General de la Ciudad de México) could consider engaging senior officials to promote openness and actively encourage employees to seek guidance and counselling. This could be in the form of annual performance evaluations and regular feedback throughout the year, creating a space where employees can voice grievances and concerns.

Box 4.1. Canada: Senior officials for public service values and ethics and departmental officers for conflict-of-interest and post-employment measures

Senior officials for public service values and ethics

The senior official for values and ethics supports the deputy head in ensuring that the organisation exemplifies public service values at every level of their organisations. The senior official promotes awareness, understanding and the capacity to apply the code amongst employees, and ensures that management practices support values-based leadership.

Departmental officers for conflict-of-interest and post-employment measures

Departmental officers for conflicts of interest and further employment are specialists in their respective organisations who have been identified to advise employees on the conflict-of-interest measures in Chapter 2 of the Values and Ethics Code.

Source: Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat (2012), Policy on Conflict of Interest and Post-Employment, http://www.tbs-sct.gc.ca/pol/doc-eng.aspx?id=25178§ion=html.

To equip management to guide and counsel employees on work-related concerns, the General Co-ordination of Evaluation and Professional Development (Coordinación General de Evaluación y Desarrollo Profesional) in the Comptroller’s Office could develop a specific training course for senior public officials, similar to the training course for the proposed Integrity Contact Points in Chapter 3. However, this course could go beyond providing advice on integrity concerns and ethical dilemmas. For example, in the case of the Integrity Contact Points, they could familiarise management with measures for building trust among employees to express any grievances or concerns.

4.2.3. Staff champions for openness could consult with staff on improving employee well-being, work processes and openness in order to empower and engage them.

In a closed organisation, lower-ranking employees can feel powerless, and as though they have no ability to bring about change. In fact, senior-level managers are more likely to report misconduct than lower-level managers (Keenan, 2002[13]). To create an open organisational culture, employees must feel empowered and believe that their voices are being heard, whether in improving work processes and structures or reporting misconduct. By encouraging and valuing employees’ contributions, staff will become confident in developing and improving their work environment. This can cultivate a pride of ownership and motivation, in which employees are more likely to offer more than the minimum demanded of their jobs (Berry, 2004[2]). It is increasingly likely they will see themselves as an important part of the organisation, and accept responsibility for voicing their ideas and concerns (Stamper and Van Dyne, 2003[14]), including speaking out against organisational misconduct. Negative experiences that communicate that the organisation does not value employee involvement or does not tolerate employee dissent will weaken employee trust. As a result, employees will feel powerless.

In interviews with public officials of Mexico City, many people confirmed that they did not feel able to change entrenched working processes and would feel reluctant to report misconduct. The risk of reprisals against them is perceived to be greater than being heard and making a positive change. In the short term, the directorates in the Comptroller’s Office could elect “champions of openness”, who would consult staff on measures to improve work processes, well-being and general openness. This could also identify hot spots where focused attention is needed. The “champions” of the different directorates could exchange good practices with one another. In the long term, this pilot project could be rolled out to other government entities, according to needs assessments.

4.2.4. A mentoring programme for junior public officials could guide and support employees and create an ethical management cadre.

Instilling a formal mentoring programme is another measure for motivating ethical behaviour in an organisation. Senior managers are responsible for assisting public officials in junior positions who show potential for advancing to leadership positions (Shacklock and Lewis, 2007[15]). This not only supports junior public officials, but can strengthen the senior public officials’ ethical convictions and contribute to an open organisational culture in which public officials feel comfortable to report wrongdoing (OECD, 2017[6]).

Mentors could help their colleagues to think through situations where they have recognised the potential of conflicting values. They help to identify measures to engage employees and develop ethical awareness, so that the mentee is able to anticipate and avoid ethical dilemmas. The Comptroller’s Office could pilot a mentoring programme in its own ranks, before expanding it to other government entities in the public sector. Mentors’ commitment could be positively assessed in performance evaluations.

4.3. Instituting a legal framework to encourage reporting and to guarantee protection for whistle-blowers

Even in very open organisations, public officials may be faced with situations in which they do not feel confident reporting integrity violations, for fear of retaliation or because the process is unclear. Establishing a clear and comprehensive whistle-blower protection framework is a safeguard for an open organisation. In Mexico City, fear of reprisals and the difficulty in following the procedures are two reasons cited for why corruption is not reported (Figure 4.2). This calls into question the effectiveness of the current protections.

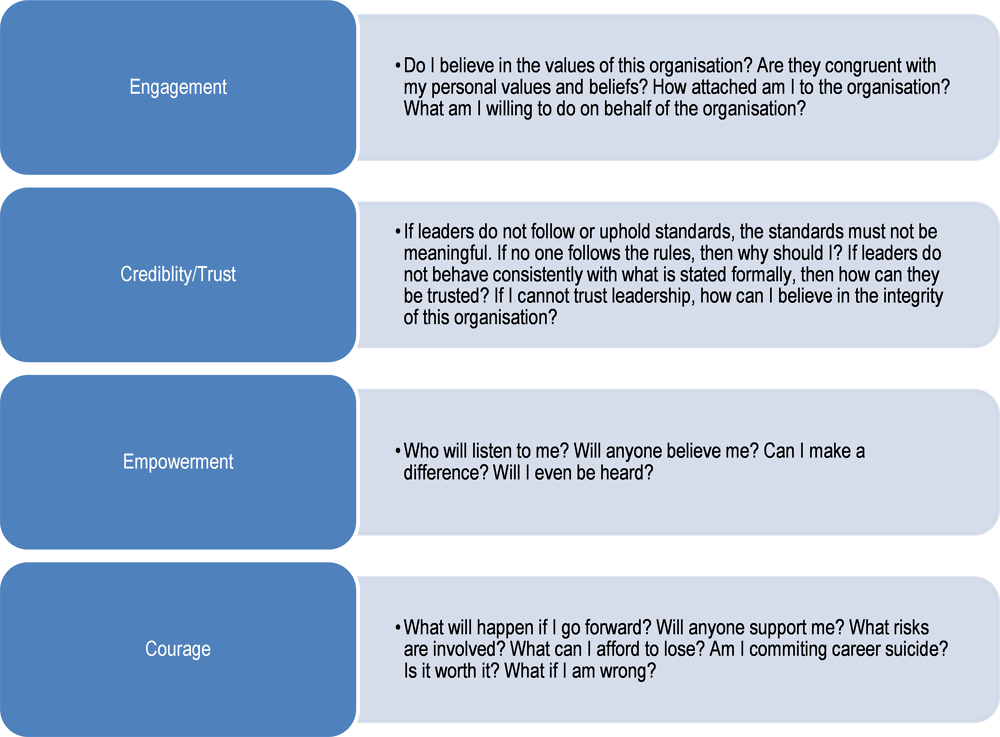

In the past decade, the majority of OECD countries have introduced whistle-blower protection laws that facilitate the reporting of misconduct and protect whistle-blowers from reprisals, not only in the private sector, but especially in the public sector. In OECD countries, such protections are provided through several different laws, such as specific anti-corruption laws, competition laws or laws regulating public servants, or through a dedicated public sector whistle-blower protection law (Figure 4.4).

Figure 4.4. Legal protection for whistle-blowers in the public sector in OECD countries

Similar to the regulations at the federal level, Mexico City does not have a dedicated whistle-blower protection law, but relies on provisions in one or more laws:

Law of Administrative Responsibilities of Mexico City (Ley de Responsabilidades Administrativas de la Ciudad de México, or LRA): Under Article 49, public servants have the obligation to report any misconduct as defined in the law. The article states that public officials should refrain from preventing such reporting. Furthermore, specific units receiving complaints and reports need to be established in each government entity, with the follow-up procedure clearly regulated by the entity. The complaints and reports need to include details identifying the alleged misconduct.

Mexico’s Federal Criminal Code (Código Penal: Article 2 191) provides that a crime of intimidation is committed when a civil servant, or a person acting on his behalf, uses physical violence or moral aggression to intimidate another person to prevent him or her from reporting, lodging a criminal complaint or providing information on the alleged criminal act.

Mexico City’s Law on Access to Information and Protection of Personal Data (Ley de Transparencia, Accesso a la Información Pública y Rendición de Cuentas de la Ciudad de México) protects the anonymity of whistle-blowers by classifying it as confidential (Article 186) and by classifying it as privileged information if there is a risk to the person’s security (Article 183).

Agreement A/007/03 of Mexico City’s Attorney General’s Office (Acuerdo A/007/ del Procurador General de Justicia del Distrito Federal por el cual se establecen areas de espera exclusivas para denunciantes, victimas, ofendidos y testigos de cargo en delitos graves): establishes dedicated waiting areas for whistle-blowers, offenders, victims and witnesses in serious crime cases.

Agreement A/010/2002 of Mexico City’s Attorney General’s Office (Acuerdo A/010/2002 del Procurador General de Justicia del Distrito Federal por el cual se establecen lineamientos para los Agentes del Ministerio Público en relación a los domicilios de los denunciantes, víctimas y ofendidos y testigos de cargo en delitos graves) establishes that public prosecutors who initiate preliminary investigations for serious crimes will record victims, offenders, whistle-blowers or witnesses addresses or telephone numbers in a separate, sealed document.

Agreement A/018/2011 of Mexico City’s Attorney General’s Office (Acuerdo A/018/2011 del C. Procurador General de Justicia del Distrito Federal que establece el procedimiento a seguir por los Agentes del Ministerio Público investigadores para hacer saber los derechos a las personas que comparezcan ante ellos a declarar en calidada de denunciantes, querellantes, ofendidos, víctimas del delito, testigos e imputados) instructs public prosecutors to read whistle-blowers, offenders, victims and witnesses their rights in accordance with the Bill of Rights (carta de derechos).

Notice on the creation of a Personal Data System for whistle-blowers of the Environmental and Territorial Order Prosecutor’s Office (Aviso por el que se da a conocer la creación del Sistema de Datos Personales de Denunciantes de la Procuraduría Ambiental y del Ordenamiento Territorial del Distrito Federal): The notice creates the personal data system collecting personal data (name, address and telephone) of the whistle-blower, through which the whistle-blower can be contacted. If requested by the whistle-blower, this information will remain confidential.

Circular OC/ 009 /2009 (Oficio Circular OC/009/2009 por el que instruye a los Oficiales Secretarios y Agentes del Ministerio Público que integran averiguaciones previas, que informen mediante acuerdo a los denunciantes, querellantes, testigos e imputados, sobre el derecho que les asiste para presentar quejas en la Dirección General de Derechos Humanos): all ministerial personnel are instructed to inform whistle-blowers, plaintiffs, witnesses and defendants of their right to file complaints with the General Directorate of Human Rights.

While this piecemeal approach is positive in the sense that it applies to the whole public sector, including state-owned enterprises, the extent of Mexico City’s protection can be considered limited and insufficient, as it is primarily designed to report integrity violations, with few explicit protections set out in the laws (OECD, 2017[16]).

4.3.1. Mexico City could enact a dedicated whistle-blower protection law to avoid duplication, ensure clarity of the kind of protections applicable and to ultimately create higher confidence in the protection framework.

Overall, the recently passed LRA of Mexico City strengthens the whistle-blower protection framework by requiring the creation of reporting channels to the competent authorities, as well as within the organisations, and by guaranteeing the anonymity of those who report integrity violations. Another strength of this law is the broad definition of “whistle-blowers”. It applies to any legal or natural person or public official who reports any conduct that could constitute or be linked to an administrative fault, as defined in the LRA of Mexico City. This clearly defines what constitutes an appropriate disclosure to the investigative authorities. In this way, public officials and the public alike have a clear guideline on what may be disclosed and under what circumstances. Moreover, the law proposes mechanisms that seek to ensure that the recipients of whistle-blower disclosures take the appropriate (investigative) action warranted by each specific disclosure, including protecting the identity of the whistle-blower and informing the whistle-blower of the outcome of the investigation, if possible. However, the law has a strong focus on the investigative process following a whistle-blower report. It does not specify the protections available to whistle-blowers and under what circumstances, which limits its clarity and reliability in its application. Rather than strengthening the current fragmented protection framework, a dedicated whistle-blower protection would ensure universally applicable protection provisions, which bring clarity and make it easier to raise awareness of the existence of these provisions (Banisar, 2011[17]). Translating whistle-blower protection into a dedicated law legitimises and structures the mechanisms under which individuals can disclose actual or perceived wrongdoing. It also protects them against reprisals and can at the same time encourage them to come forward and report wrongdoing. For example, the whistle-blower protection law in the Canadian province of Alberta creates reporting mechanisms, details the protections available and the investigative process and details how the framework is monitored and evaluated (Box 4.2).

Box 4.2. Whistle-blower protection in Alberta, Canada

Alberta’s whistle-blower protection law came into force on 1 June 2013; with the enactment of the Public Interest Disclosure (Whistle-blower Protection) Act. The goal of the legislation is to protect public sector employees from job reprisal, such as termination, if they report wrongdoing. The new law applies to the Alberta public service, provincial agencies, boards and commissions, as well as academic institutions, school boards and health organisations.

The law also creates processes for the disclosure of wrongdoing. It also provides for the Office of the Public Interest Disclosure Commissioner to investigate and resolve complaints by public sector employees who report violations of provincial or federal law, acts or omissions that create a danger to the public or environment, and gross mismanagement of public funds.

The penalty for offences under the Act is CAD 25 000 for the first conviction to a maximum of up to CAD 100 000 for subsequent offences.

Source: https://yourvoiceprotected.ca/.

Adopting a dedicated whistle-blower protection law would send a strong message to public servants and the general public alike that it is safe to speak up and report wrongdoing, and that reprisals against whistle-blowers are not tolerated.

4.3.2. The distinction between witness and whistle-blower protection should be clearly delineated, to ensure that disclosures that do not lead to a full investigation or to prosecution are eligible for legal protection.

There is a potential overlap between whistle-blowers and witnesses. Some whistle-blowers may possess solid evidence and eventually become witnesses in legal proceedings (Transparency International, 2013[18]). When whistle-blowers testify during court proceedings, they can be covered under existing witness protection laws. The Mexican framework offers witness protection pursuant to Article 109 of the National Code of Criminal Procedures (Código Único Nacional de Procedimientos Penales), which also applies in Mexico City.

However, if the subject matter of a whistle-blower report does not result in criminal proceedings, or the whistle-blower is never called as a witness, witness protection will not be provided. Basing the eligibility for such protection on the decision to investigate disclosures and subsequently prosecute related offences reduces the certainty surrounding legal protections against reprisals. This is because such decisions are often taken on the basis of considerations that are not divulged to the public. Indeed, it may be more effective, in terms of detecting misconduct, to facilitate measures by which whistle-blowers may report relevant facts that could lead to an investigation or prosecution. Whistle-blowers will then be more likely to report relevant facts if they know they will be protected regardless of the decision to investigate or prosecute. Furthermore, whistle-blowers may face risks that are not covered by witness protection programmes, such as demotion or dismissal. In terms of remedies for retaliation, they may need compensation for salary losses and career opportunities. As such, witness protection laws are not sufficient to protect whistle-blowers (Transparency International, 2009[19]).

A dedicated whistle-blower law or a proposal for an amended law would therefore need to modify Code of Criminal Procedures. It would need to establish protection for those disclosing information about an act of corruption that might not be recognised as a crime, but that could be subject to administrative investigations.

4.3.3. Mexico City could consider specifically prohibiting the dismissal of whistle-blowers without a cause, or any other kind of formal or informal work-related penalty in response to the disclosure.

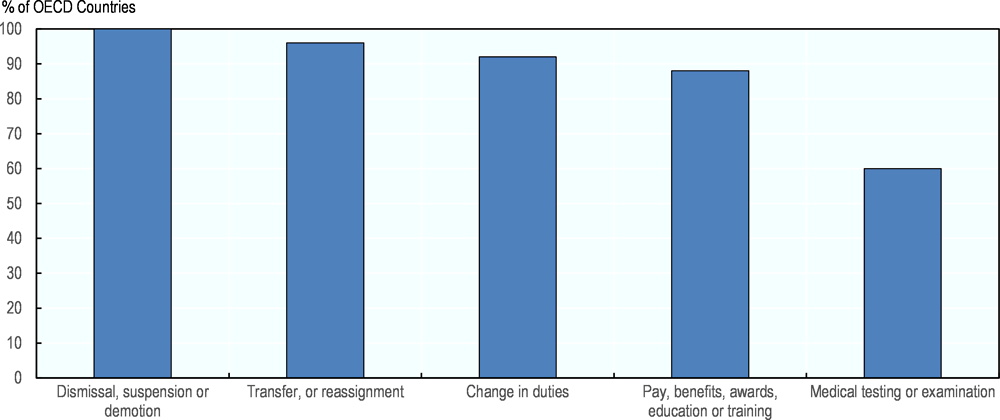

Whistle-blowers face the risk of retaliation when exposing wrongdoing. Such retaliation usually takes the form of disciplinary action or harassment in the workplace. Whistle-blower protection frameworks should provide protection against discriminatory or retaliatory personnel action. The majority of OECD countries (Figure 4.5) provide protection for whistle-blowers from a broad range of reprisals, ranging from dismissal to medical testing and examination.

Figure 4.5. OECD countries providing protection from all discriminatory or retaliatory personnel actions

Source: (OECD, 2016[10]), Committing to Effective Whistle-blower Protection, OECD Publishing, Paris.

The Administrative Responsibilities Law foresees limited protection for whistle-blowers. In addition to the protection of anonymity, public officials can request reasonable protection measures (Article 64). While this expands the previous framework, some weaknesses concerning the scope of the protection remain. The law does not detail what measures are considered to be “reasonable”. This leaves a large degree of uncertainty for a potential whistle-blower on the scope of protection available. To clarify what measures are available, Mexico City could add a non-exhaustive list of specific protective measures. Such protection should extend beyond the protection from physical harm and include protection from discriminatory or retaliatory actions. In this way, Mexico City would set a benchmark for other Mexican states. Specifically, Mexico City may consider prohibiting the dismissal without cause of public sector whistle-blowers, as well as other work-related reprisals such as demotion, suspension and harassment. For example, according to the United States’ Project on Government Oversight, typical forms of retaliation from which whistle-blowers are protected include (Project on Government Oversight, 2005[20]):

taking away job duties so that the employee is marginalised.

taking away an employee’s national security clearance so that he or she is effectively fired.

blacklisting an employee so that he or she is unable to find gainful employment.

conducting retaliatory investigations in order to divert attention from the waste, fraud or abuse the whistle-blower is trying to expose.

questioning a whistle-blower’s mental health, professional competence or honesty.

setting the whistle-blower up by giving impossible assignments or seeking to entrap him or her.

reassigning an employee geographically so he or she is unable to do the job.

Anchoring similar protections within the Mexican City legal framework will give whistle-blowers more confidence in the procedures. Similarly, Korea’s Protection of Public Interest Whistle-blowers Act provides a comprehensive list of what disadvantageous measures whistle-blowers should be protected against, including financial or administrative disadvantages, such as the cancellation of a permit or licence, or the revocation of a contract (Box 4.3).

Box 4.3. Comprehensive protection in Korea

In Korea, the term “disadvantageous measures” means an action that falls into any of the following categories:

removal from office, release from office, dismissal or any other unfavourable personnel action equivalent to the loss of status at work.

disciplinary action, suspension from office, reduction in pay, demotion, restriction on promotion and any other unfair personnel actions.

work reassignment, transfer, denial of duties and rearrangement of duties or any other personnel actions that are against the whistle-blower’s will.

discrimination in the performance evaluation, peer review, etc. and subsequent discrimination in the payment of wages and bonuses.

cancellation of education, training or other self-development opportunities; the restriction or removal of budget, workforce or other available resources, suspension of access to security information or classified information; cancellation of authorisation to handle security information or classified information; or any other discrimination or measure detrimental to the working conditions of the whistle-blower.

Putting the whistle-blower’s name on a blacklist, as well as the release of such a blacklist, bullying, the use of violence and abusive language towards the whistle-blower, or any other action that causes psychological or physical harm to the whistle-blower.

Unfair audit or inspection of the whistle-blower’s work, as well as the disclosure of the results of such an audit or inspection.

The cancellation of a licence or permit, or any other action that causes administrative disadvantages to the whistle-blower.

Source: Korea’s Act on the Protection of Public Interest Whistle-blowers (2011), Act No. 10 472, 29 March 2011. Article 2 (6).

In addition, the law does not specify the duration of the protection available. As reprisals are not always immediate, the length of the time during which a whistle-blower is protected against reprisals needs to be regulated within the legislation and clearly communicated. In Belgium, the period for protection against reprisal is two years following the conclusion of the investigation of the report.

4.3.4. By explicitly including civil remedies for public officials who suffer reprisals after disclosing misconduct, Mexico City could add another layer of protection to the whistle-blower protection framework.

To provide more clarity on the measures available if a whistle-blower experiences reprisal after disclosing misconduct, whistle-blower protection systems include specific remedies, as opposed to leaving enforcement entirely up to enforcement authorities. This may cover all direct, indirect and future consequences of reprisal. They range from return to employment after unfair termination, job transfers or compensation, or damages if there was harm that cannot be remedied by injunctions, such as difficulty in finding a new job. Such remedies may take into account not only lost salary but also compensatory damages for suffering (Banisar, 2011[17]). For example, Canada’s Public Servants Disclosure Protection Act (PSDPA) includes a comprehensive list of remedies (Box 4.4). Moreover, the availability of effective civil remedies may help mitigate professional marginalisation of whistle-blowers by providing an opportunity for rehabilitation by civil courts (OECD, 2017[16]).

Box 4.4. Remedies in Canada for public sector whistle-blowers

To provide an appropriate remedy to the complainant, the Tribunal may, by order, require the employer or the appropriate chief executive, or any person acting on their behalf, to take all necessary measures to:

permit the complainant to return to his or her duties.

reinstate the complainant or pay compensation to the complainant in lieu of reinstatement if, in the Tribunal’s opinion, the relationship of trust between the parties cannot be restored.

pay to the complainant compensation in an amount not greater than the amount that, in the Tribunal’s opinion, is equivalent to the remuneration that would, but for the reprisal, have been paid to the complainant.

rescind any measure or action, including any disciplinary action, and pay compensation to the complainant in an amount not greater than the amount that, in the Tribunal’s opinion, is equivalent to any financial or other penalty imposed on the complainant.

pay to the complainant an amount equal to any expenses and any other financial losses incurred by the complainant as a direct result of the reprisal.

compensate the complainant, by an amount of not more than USD 10 000, for any pain and suffering that the complainant experienced as a result of the reprisal.

Source: Canada’s Public Servants Disclosure Protection Act of 2005, 21.7 (1).

In Mexico City, the current framework does not provide any remedies for public officials who suffer reprisals after reporting misconduct. By explicitly stating the remedies available following retaliatory action, whistle-blowers have clearer expectations which protectionary measures are available to them. This builds trust in the system. The Administrative Justice Tribunal (Tribunal de Justicia Administrativa), which will be established according to the governance structure of the Local Anti-corruption System, could take on the role of deciding over civil remedies in such cases. Such remedies could also compensate whistle-blowers for prospective revenue losses. Finally, allowing whistle-blowers to introduce their own recourse before courts, instead of relying on the availability of resources from public authorities, could reinforce public trust in the whistle-blowing framework. Combined with effective public awareness-raising campaigns, appropriate civil remedies can significantly improve public perceptions about whistle-blowers and indirectly mitigate professional marginalisation and prospective financial losses (OECD, 2017[16]).

4.3.5. Mexico City could consider shifting the burden of proof to the employer to present evidence that any penalty exercised against a whistle-blower is not related to the actual or potential disclosure.

Given that reprisals are often very subtle, an employee may find it difficult to prove that reprisals were a consequence of the disclosure (Chêne, 2009[21]). To mitigate this, several whistle-blower protection systems provide a reversed burden of proof and assume that retaliation has occurred where adverse action against a whistle-blower cannot be clearly justified by management on grounds unrelated to the disclosure (OECD, 2016[10]). The system in the United States applies a burden-shifting scheme whereby a federal employee who is a purported whistle-blower must first establish that she or he:

disclosed conduct that meets a specific category of wrongdoing set forth in the law.

made the disclosure to the “right” type of party (depending on the nature of the disclosure, the employee may be limited in selecting the person to whom to bring the report).

had a reasonable belief that the information is evidence of wrongdoing (the employee does not have to be correct, but the belief must be one that could be shared by a disinterested observer with knowledge and background equivalent to that of the whistle-blower).

suffered a personnel action, the agency’s failure to take a personnel action, or the threat to take or not to take a personnel action.

demonstrated that the disclosure was a contributing factor for the personnel action, failure to take a personnel action, or the threat to take or not take a personnel action (in practice, this is largely equivalent to a modest relevance standard).

has sought redress through the proper channels.

If the employee establishes each of these elements, the burden shifts to the employer to establish by clear and convincing evidence that it would have taken the same action in the absence of the whistle-blowing, in which case relief to the whistle-blower would not be granted (United States Merit Systems Protection Board, 2011[22]). Clear and convincing evidence means that it is substantially more likely than not that the employer would have taken the same action in the absence of whistle-blowing (OECD, 2016[10]).

If Mexico City modifies the current administrative responsibilities law or passes a dedicated whistle-blower protection law, it could shift the burden of proof to the employer if an employee who has made a protected disclosure is subject to any type of penalty. However, this would have implications for legislation on the federal level. Article 281 of the Civil Procedure Code (Código Procedimientos Civiles) would need to be modified accordingly. Similarly, the Labour Law would need to be adjusted.

4.4. Ensuring effective review and investigation of reports

4.4.1. To increase trust in the whistle-blower protection framework, Mexico City could create an independent agency to receive and investigate reports on misconduct.

As evident from the on-site interviews, even if there were strong legal protections guaranteed for whistle-blowers, public officials would not necessarily feel comfortable to come forward to report misconduct, given the culture of mistrust and lack of a professional civil service scheme protecting whistle-blowers from unlawful termination of contract.

As a long-term priority, Mexico City could send a strong signal to public officials and the public about its commitment to fight corruption and protect whistle-blowers. This would entail creating an independent agency or position with the mandate to receive, investigate, and provide remedies for complaints of retaliation. Mexico City could introduce an anti-corruption commissioner or trust attorney that allows whistle-blowers to report anonymously, as in several German states (Box 4.5). This would provide individuals with a channel for disclosing wrongdoing that they may feel more comfortable with than the alternatives. In some cases, hotlines or online platforms provide potential whistle-blowers with the option of disclosing information anonymously, a practice that should be coupled with the allocation of a unique identification number to callers that allows them to call back later anonymously to receive feedback or answer follow-up questions from investigators.

Box 4.5. External reporting channels in German states

German states have established different external channels to facilitate reporting:

Schleswig-Holstein: Anti-corruption Commissioner. In 2007, the government of Schleswig-Holstein, Germany, set up a contact point for combating corruption (KBK-SH), which was established as a permanent institution after a two-year pilot phase. It has been created as a point of contact for whistle-blowers and is independent from the administration. An Anti-corruption Commissioner for the state of Schleswig-Holstein was appointed to carry out the tasks. The Anti-corruption Commissioner acts as an independent mediator between whistle-blowers, the administration and law enforcement agencies. Whistle-blowers can report to him anonymously or under confidentiality. The Anti-corruption Commissioner is enjoined to total discretion and to fully protect the identity of the whistle-blowers. Reports that are not within the area of responsibility of the contact point are forwarded to the respective office responsible. The Anti-corruption Officer can be contacted by telephone, e-mail or post. Detailed information is made available on the website of the state government of Schleswig-Holstein.

Lower Saxony: Internet-based information system. Since 2003, the State Office of Criminal Investigation has been using an Internet-based information system to receive anonymous reports of corruption and economic crime (BKMS system). It is also possible to use a virtual mailbox to communicate anonymously with the police officer and answer follow-up questions on the report.

Baden-Wurttemberg: Trust Attorney. In September 2009, the position of trust attorney was introduced to improve the handling of reports of corruption. The attorney can be contacted as an independent contact point outside the administration, to receive reports on corruption. The attorney accepts anonymous reports and examines them for their credibility and criminal relevance. If sufficient evidence emerges of misconduct of employees or third parties at the expense of the state government, the report will be referred to the highest state authority. The authority will be in charge of further investigations and may, if necessary, ask the attorney to forward questions to the whistle-blower. If the report does not fall under the purview of the authority, it will be referred to the respective local authority, unless employees of the local authority are accused. It is then sent to the next highest-ranking body. In addition, the State Office of Criminal Investigation operates an Internet-based interactive system.

Source: (Müller, 2012[23]), Korruptionsbekämpfung in Deutschland: Institutionelle Ressourcen der Bundesländer im Vergleich, Transparency International, available from https://www.transparency.de/fileadmin/Redaktion/Publikationen/2012/Korruptionsbekaempfung_in_Deutschland_TransparencyDeutschland_2012.pdf, accessed on 27 February 2017.

In Canada, the Public Sector Integrity Commissioner, an independent office receiving and investigating disclosures is required to report annually to Parliament and has the power to give recommendations to the heads of public offices. The Public Servants Disclosure Protection Tribunal is in charge of determining remedies and penalties when violations of whistle-blowers’ rights occur (Box 4.6).

Box 4.6. Office of the Public Interest Commissioner Alberta, Canada

The Office of the Public Interest Commissioner is an independent office of the Alberta Legislature providing advice and investigating disclosures of wrongdoing and complaints of reprisals made by employees of jurisdictional public entities covered by Alberta’s Public Interest Disclosure Act. The Public Interest Commissioner is a nonpartisan officer of the Legislature appointed by the Lieutenant Governor in Council on the recommendation of the Legislative Assembly, for a term of five years with the possibility of reappointment. On its website, the Office provides clear guidance on whom the whistle-blower legislation applies to, what is defined as a wrongdoing, what is a reprisal, and how public officials are protected. An online disclosure form is made available through the website.

The Office of the Public Interest Commissioner also gives advice to public entities by providing examples of whistle-blower policies and procedural guidelines and checklists. The Office also provides recommendations on the legislation and possible improvements.

Its annual budget, which is approved by the legislative assembly, was CAD 1.196 million in 2014-15.

4.5. Strengthening awareness

4.5.1. An intensive communication strategy, within government entities and in society at large, could increase the knowledge of the reporting channels and protections available.

To promote a culture of openness and integrity in which public officials trust that their reports will be followed up and that they will be protected from reprisals, the legislation will need to be supported by an open organisational culture in government entities. This will include awareness-raising, communication and training efforts. Assuring whistle-blowers that their concerns are being heard and that they are supported in their choice to come forward is paramount to the integrity of an organisation, and to how whistle-blowers are viewed by society as a whole. There are multiple measures that organisations can take to encourage the detection and disclosure of wrongdoing. These steps would encourage an open organisational culture, help reinforce trust and working relationships, and boost staff morale.

Mexico City does not at present offer training for senior managers on how to create an open organisational culture within their area of management. The Directorate for Complaints and Reports (Dirección de Quejas y Denuncias) of the Comptroller’s Office, in co-ordination with Human Resources, could develop an annual training course for senior management on how to create such a culture, how to be receptive to reports of misconduct, and how to proceed when receiving such reports. In addition, Mexico City could oversee annual training and notices to public officials on their rights and the available protection under the whistle-blower legislation. For example, the US Office of the Special Counsel (OSC) has a Certification Programme developed under section 5 U.S.C. § 2 302(c), which has made efforts to promote outreach, investigations and training as the three core methods for raising awareness. The OSC offers training to federal agencies and non-federal organisations in each of the areas within its jurisdiction, including reprisal for whistle-blowing. To ensure that public officials understand their whistle-blower rights and how to make protected disclosures, agencies must complete OSC’s programme to certify compliance with the Whistle-blower Protection Act’s notification requirements (Box 4.7).

Box 4.7. The United States’ approach to increasing awareness through the Whistle-blower Protection Enhancement Act

Under 5 U.S.C. § 2 302(c) of the Whistle-blower Protection Enhancement Act (WPEA) stipulates that “the head of each agency shall be responsible for the prevention of prohibited personnel practices, for the compliance with and enforcement of applicable civil service laws, rules, and regulations, and other aspects of personnel management, and for ensuring (…) that agency employees are informed of the rights and remedies available to them, including how to make a lawful disclosure of information that is specifically required by law or Executive order to be kept classified in the interest of national defence or the conduct of foreign affairs to the Special Counsel, the Inspector General of an agency, Congress, or other agency employee designated to receive such disclosures.”

Furthermore, Section 117 of the Act “designates a Whistle-blower Protection Ombudsman who shall educate agency employees”:

1. about prohibitions on retaliation for protected disclosures; and

2. who have made or are contemplating making a protected disclosure about the rights and remedies against retaliation for protected disclosures.

Source: (American Bar Association, 2012[24]), Section of Labor and Employment Law, “Congress Strengthens Whistle-blower Protections for Federal Employees,” Issue: November-December.

Furthermore, all government entities within the administration, co-ordinated by the Directorate for Complaints and Reports (Dirección de Quejas y Denuncias) of the Comptroller’s Office, could introduce awareness-raising campaigns. These would underscore whistle-blowers’ role in promoting the public interest by shedding light on misconduct that harms the effective management and delivery of public services and ultimately, the fairness of the whole public service. Such campaigns will counter any perception that whistle-blowing constitutes a lack of loyalty to the organisation. For example, the Public Interest Commission of Alberta designed a series of posters and distributed them to public entities to be displayed in employee workspaces. The posters show messages such as “Make a change by making a call. Be a hero for Alberta’s public interest”. Public officials should feel that they should remain loyal to the public interest, and not to public officials who have been appointed by the government of the day. The UK Civil Service Commission suggests including a statement in staff manuals to assure them that it is safe to raise concerns (Box 4.8). Mexico City may consider similar statements and materials.

Box 4.8. Example of a statement to staff reassuring them to raise concerns

“We encourage everyone who works here to raise any concerns they have. We encourage ‘whistle-blowing’ within the organisation to help us put things right if they are going wrong. If you think something is wrong, please tell us and give us a chance to properly investigate and consider your concerns. We encourage you to raise concerns and will ensure that you do not suffer a detriment for doing so.”

Source: UK Civil Service Commission: http://civilservicecommission.independent.gov.uk/wp-content/uploads/2014/02/Whistle-blowing-and-the-Civil-Service-Code.pdf.

By introducing and implementing such measures, Mexico City can facilitate awareness of the importance of an open organisation culture and whistle-blower protection, which not only enhances understanding of these mechanisms, but is also an important mechanism used to correct the often negative perceptions associated with the term whistle-blower. Communicating such messages publicly can enhance the perception of whistle-blowers as important safeguards for the public interest. Moreover, demonstrating the importance of whistle-blowers and showing how they are protected in practice can help restore trust in the government. In the United Kingdom, public understanding of the term whistle-blower shifted considerably after the adoption of the Public Interest Disclosure Act in 1998 (Box 4.9).

Box 4.9. Changing cultural connotations in the United Kingdom of the concept of whistle-blowing

In the United Kingdom, a research project commissioned by Public Concern at Work from Cardiff University examined national newspaper reporting on whistle-blowing and whistle-blowers over the period from 1 January 1997 to 31 December 2009. This includes the period immediately before the introduction of the Public Interest Disclosure Act and tracks how the culture has changed since then. The study found that whistle-blowers were overwhelmingly represented in a positive light in the media. Over half (54%) of the newspaper stories represented whistle-blowers in a positive light, with only 5% of stories being negative. The remainder (41%) were neutral. Similarly, a study by YouGov found that 72% of workers view the term “whistle-blowers” as neutral or positive.

Source: (Public Concern at Work, 2010[25]), “Where’s whistle-blowing now? Ten years of legal protection for whistle-blowers”, Public Concern at Work, London, p. 17, YouGov (2013), YouGov/PCAW Survey Results, YouGov, London, p. 8.

4.6. Conducting evaluations and increasing the use of metrics

4.6.1. Regular staff climate surveys could assess the effectiveness of the measures taken to promote an open organisational culture

Employee surveys can review staff awareness, trust and confidence in whistle-blowing mechanisms. In Colombia, for example, the National Statistics Department (Departamento Administrativo Nacional de Estadística) conducts surveys with public officials that include questions on the organisational climate, why a public official would not report corruption, whether there is knowledge of the existence of protection mechanisms, and if public officials would seek protection. Such efforts play a key role in assessing progress – or lack thereof – in creating an open organisational culture.

Under the guidance of the Executive Commission of the Local Anti-corruption System, each government entity could regularly survey staff on the organisational climate, to assess the outcome of policies intended to promote an open climate. Collecting these surveys centrally and ranking the results could encourage entities to increase their efforts to improve the organisational culture.

4.6.2. Mandating a periodic review of whistle-blower protection legislation could assess the implementation, effectiveness and relevance of the legislation.

Following the OECD’s recommendation on the federal level (OECD, 2017[16]), Mexico City could consider periodically reviewing the Administrative Responsibilities Law and, if it is enacted, the dedicated whistle-blower protection legislation, to assess whether the mechanisms in place are meeting their intended objectives and whether the law is adequately implemented. This would allow for adjustments, if necessary. Provisions on the review of effectiveness, enforcement and impact of whistle-blower protection laws have been introduced by a number of OECD countries, such as Australia, Canada, Japan, and the Netherlands. Japan’s Whistle-blower Protection Act specifically outlines that the government must take the necessary measures based on the findings of the review. At the federal level and in the provinces of Canada, the review of the legislation enacted to protect disclosure of wrongdoings and for protecting public servants who disclose wrongdoings must be presented before the Legislative Assembly.

4.6.3. To evaluate the effectiveness of the whistle-blower framework, Mexico City could consider systematically collecting data and establishing robust indicators.

Mexico City could gather information on 1) the number and types of disclosures received; 2) the government entities receiving most disclosures; 3) the outcomes of cases (i.e. if the disclosure was dismissed, accepted, investigated and validated, and on what grounds); 4) whether the misconduct came to an end as a result of the disclosure; 5) whether the organisation’s policies were changed as a result of the disclosure if gaps were identified; 6) whether penalties were exercised against wrongdoers; 7) the scope, frequency and target audience of awareness-raising mechanisms; and 8) the time it takes to process cases (Transparency International, 2013[18]; Apaza and Chang, 2011[26]).

This data can help assess how effective the policies supporting an open organisation culture are and, more specifically, make possible an assessment of the effectiveness of whistle-blower protection mechanisms. To measure the effectiveness of protective measures for whistle-blowers, additional data could be collected on cases where whistle-blowers claimed that they experienced reprisals. This could include whether allegations of reprisals were investigated, by whom, and how reprisals were exercised, whether and how whistle-blowers were compensated, the basis for these decisions, the time it takes to compensate whistle-blowers, and whether they were employed during the judicial process.

Proposals for action

An open organisational culture, responsive to integrity concerns, ensures integrity and encourages employees to express their concerns without fear of persecution. Legitimising and structuring mechanisms through a legal framework is essential to this approach, as are organisational policies that allow public officials to disclose actual or perceived wrongdoings.

Encouraging an open organisational culture

To ensure that senior managers act as role models, integrity could be included as a performance indicator to incentivise the application of the Code of Ethics.

To encourage public officials to voice concerns and discuss integrity concerns, the Comptroller’s Office could engage senior public officials to provide guidance, advice and counsel.

To empower and engage employees, staff champions for openness could consult with staff on measures to improve employee well-being, work processes and openness.

A mentoring programme for junior public officials could be developed to guide and support employees and create a future ethical management cadre.

The right legal framework can encourage reporting and guarantee protection for whistle-blowers.

Mexico City could enact a dedicated whistle-blower protection law to avoid duplication, ensure clarity of the kind of protections applicable and to ultimately create greater confidence in the protection framework.

The difference between witness and whistle-blower protection needs to be clearly delineated, to ensure that disclosures that do not lead to a full investigation or to prosecution are still eligible for legal protection.

Mexico City could consider specifically prohibiting the dismissal of whistle-blowers without cause, or any other kind of formal or informal work-related penalty that has been exercised in response to the disclosure.

By explicitly including civil remedies for public officials who suffer reprisals after disclosing misconduct, Mexico City would add another layer of protection to the whistle-blower protection framework.

Mexico City could consider shifting the burden of proof to the employer, to provide evidence that any penalty imposed on a whistle-blower is not related to the actual or potential disclosure.

Ensuring effective review and investigation of reports

To strengthen trust in the procedures and guarantees of the whistle-blower protection framework, Mexico City could create an independent agency mandated to receive and investigate reports on misconduct and provide remedies as necessary.

Strengthening awareness

A communication strategy and increased awareness-raising efforts, both within the different government entities as well as externally, would increase the knowledge of the available reporting channels and protections.

Conducting evaluations and increasing the use of metrics

Regular staff climate surveys could assess the effectiveness of the measures taken to promote an open organisational culture.

Mandating a periodic review of the whistle-blower protection legislation would ensure an assessment of the implementation, effectiveness and relevance of the legislation.

To evaluate the effectiveness of the whistle-blower framework, Mexico City could consider systematically collecting data and establishing robust indicators.

References

[24] American Bar Association (2012), “Congress Strengthens Whistleblower Protections for Federal Employees”, https://www.americanbar.org/content/newsletter/groups/labor_law/ll_flash/1212_abalel_flash/lel_flash12_2012spec.html.

[26] Apaza, C. and Y. Chang (2011), “What Makes Whistleblowing Effective”, Public Integrity, Vol. 13/2, pp. 113-130, http://dx.doi.org/10.2753/PIN1099-9922130202.

[17] Banisar, D. (2011), “Whistleblowing: International Standards and Developments”, in Corruption and Transparency: Debating the Frontiers between State, Market and Society, I. Sandoval, ed., World Bank-Institute for Social Research, UNAM, Washington, D.C, https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1753180.

[2] Berry, B. (2004), “Organizational Culture: A framework and strategies for facilitating employee whistleblowing”, Employee Responsibilities and Rights Journal, Vol. 16/1, pp. 1-11, http://dx.doi.org/10.1023/B:ERRJ.0000017516.40437.b1.

[5] Brown, M., L. Treviño and D. Harrison (2005), “Ethical leadership: A social learning perspective for construct development and testing”, Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, Vol. 97/2, pp. 117-134, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/J.OBHDP.2005.03.002.

[21] Chêne, M. (2009), Good Practice in Whistleblowing Protection legislation (WPL), U4 Anti-corruption Resource Centre, Bergen, Norway, http://www.u4.no/publications/good-practice-in-whistleblowing-protection-legislation-wpl.pdf.

[9] Heard, E. and Miller, W. (2006), “Effective code standards on raising concerns and retaliation”, Journal of Business Ethics Review.

[3] INEGI (Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía) (2015), Encuesta Nacional de Calidad e Impacto Gubernamental (ENCIG) 2015, http://www.beta.inegi.org.mx/proyectos/enchogares/regulares/encig/2015/default.html (accessed on 17 October 2018).

[12] John Cuellar, M. and M. John (2009), An Examination of the Deaf Effect Response to Bad News Reporting in Information Systems Projects, https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/cis_diss/32.

[13] Keenan, J. (2002), “Whistleblowing: A Study of managerial differences”, Employee Responsibilities and Rights Journal, Vol. 14/1, pp. 17-32, http://dx.doi.org/10.1023/A:1015796528233.

[1] Martins, E. and F. Terblanche (2003), “Building organisational culture that stimulates creativity and innovation”, European Journal of Innovation Management, Vol. 6/1, pp. 64-74, http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/14601060310456337.

[4] Marván Laborde, M. (2015), “La corrupción en México: Percepción, prácticas y sentido ético - Encuesta Nacional de Corrupción y Cultura de la Legalidad”, in Los mexicanos vistos por sí mismos, Los grandes temas nacionales, Universidad Autónoma de México, http://www.losmexicanos.unam.mx/corrupcionyculturadelalegalidad/encuesta_nacional.html (accessed on 14 June 2017).

[23] Müller, D. (2012), Korruptionsbekämpfung in Deutschland: Institutionelle Ressourcen der Bundesländer im Vergleich, Transparency International, Berlin, https://www.transparency.de/fileadmin/Redaktion/Publikationen/2012/Korruptionsbekaempfung_in_Deutschland_TransparencyDeutschland_2012.pdf.

[8] Near, J. and M. Miceli (1985), “Organizational dissidence: The case of whistle-blowing”, Journal of Business Ethics, Vol. 4/1, pp. 1-16, http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/BF00382668.

[6] OECD (2017), OECD Integrity Review of Colombia: Investing in Integrity for Peace and Prosperity, OECD Public Governance Reviews, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264278325-en.

[16] OECD (2017), OECD Integrity Review of Mexico: Taking a Stronger Stance Against Corruption, OECD Public Governance Reviews, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264273207-en.

[11] OECD (2017), OECD Integrity Review of Peru: Enhancing Public Sector Integrity for Inclusive Growth, OECD Public Governance Reviews, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264271029-en.

[10] OECD (2016), Committing to Effective Whistleblower Protection, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264252639-en.

[20] Project on Government Oversight (2005), Homepage, https://www.pogo.org/ (accessed on 20 June 2016).

[25] Public Concern at Work (2010), Where’s whistle-blowing now? 10 years of legal protection for whistle-blowers, https://www.pcaw.org.uk/documents/whistleblowing-beyond-the-law/pida_10year_final_pdf/.

[7] Rothwell, G. and J. Baldwin (2007), “Ethical climate theory, whistle-blowing, and the code of silence in police agencies in the State of Georgia”, Journal of Business Ethics, Vol. 70/4, pp. 341-361, http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10551-006-9114-5.

[15] Shacklock, A. and M. Lewis (2007), Leading with Integrity: A fundamental principle of integrity and good governance, Griffith University, http://hdl.handle.net/10072/18843.

[14] Stamper, C. and L. Van Dyne (2003), “Organizational citizenship: A comparison between part-time and full-time service employees”, The Cornell Hotel and Restaurant Administration Quarterly, Vol. 44/1, pp. 33-42, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0010-8804(03)90044-9.

[18] Transparency International (2013), Whistleblowing in Europe: Legal protections for whistleblowers in the EU, https://www.transparency.org/whatwedo/publication/whistleblowing_in_europe_legal_protections_for_whistleblowers_in_the_eu (accessed on 21 October 2015).

[19] Transparency International (2009), Alternative to silence: whistleblower protection in 10 European countries by Transparency International - Issuu, Transparency International, Berlin, http://issuu.com/transparencyinternational/docs/2009_alternativetosilence_en?mode=window&backgroundColor=%23222222 (accessed on 12 January 2018).

[22] United States Merit Systems Protection Board (2011), Blowing the Whistle: Barriers to Federal Employees Making Disclosures, https://www.mspb.gov/netsearch/viewdocs.aspx?docnumber=662503&version=664475.