This chapter examines the Slovak Republic's efforts to cultivate a whole-of-society culture of integrity. It assesses the current integrity issues facing Slovak society, drawing from perception surveys describing the impact of corruption on society. This chapter clarifies how integrity standards are an essential tool for civil society organisations, and highlights the necessity of providing clear guidance to the private sector on their roles and responsibilities for public integrity. In addition, this chapter explores existing avenues to mainstream public integrity into the curriculum at the primary, secondary and post-secondary levels.

OECD Integrity Review of the Slovak Republic

4. Strengthening a whole-of-society approach to public integrity in the Slovak Republic

Abstract

Introduction

Public integrity is not just an issue for the public sector: individuals, civil society and companies shape interactions in society, and their actions can harm or foster integrity in their communities. A whole-of-society approach asserts that as these actors interact with public officials and play a critical role in setting the public agenda and influencing public decisions, they also have a responsibility to promote public integrity (OECD, 2020[1]). As the 2017 OECD Recommendation on Public Integrity stipulates: adherents should “promote a whole-of-society culture of public integrity, partnering with the private sector, civil society and individuals, in particular through:

Recognising in the public integrity system the role of the private sector, civil society and individuals in respecting public integrity values in their interactions with the public sector, in particular by encouraging the private sector, civil society and individuals to uphold those values as a shared responsibility.

Engaging relevant stakeholders in the development, regular update and implementation of the public integrity system.

Raising awareness in society of the benefits of public integrity and reducing tolerance of violations of public integrity standards and carrying out, where appropriate, campaigns to promote civic education on public integrity, among individuals and particularly in schools.

Engaging the private sector and civil society on the complementary benefits to public integrity that arise from upholding integrity in business and in non-profit activities, sharing and building on, lessons learned from good practices” (OECD, 2017[2]).

A “whole-of- society” approach to public integrity requires companies, civil society organisations and individuals to ensure that their engagement with the public sector respects the shared ethical norms, principles and values of society (OECD, 2020[1]). How this materialises depends on the role each actor has in society. For companies, it can involve complying with environmental and human rights standards when carrying out their business activities, paying their fair share in taxes, refraining from offering bribes, and ensuring that lobbying activities align with the long-term sustainability goals set by the company. For civil society organisations, it can include ensuring that they adhere to standards of public integrity when acting as a service provider or advocating for policy issues. For individuals, it can mean respecting the rules governing interactions with public officials and access to public monies, including respecting public property, not engaging in fraudulent social benefit schemes or avoiding taxes, and reporting corruption and fraud when they encounter it (OECD, 2020[1]).

Corruption is a major concern of Slovak citizens and they are aware of corruption issues within government and society. According to the latest 2020 Eurobarometer Survey, 87% of individuals consider corruption to be widespread in the Slovak Republic, compared to an EU average of 37% (European Commission, 2019[3]). In addition, 52% of Slovaks believe that corruption has increased over the last three years (4% decreased from 2017) and 41% of Slovaks believe they are personally affected by corruption in their daily life (-1% from 2017) (European Commission, 2019[3]). The perception of corruption is thus pervasive and extends into a lack of trust in politicians and the wider governmental system.

Corruption is also a concern of companies doing business in the Slovak Republic. For example, 88% of companies consider corruption to be widespread (EU average 63%) and 53% of companies consider that corruption is a problem when doing business compared to an EU average of 37% (European Commission, 2020[4]). According to the 2020 Global Competitiveness Report, the Slovak Republic is ranked 42 among 140 countries (Schwab, Zahidi and World Economic Forum, 2020[5]).

These numbers demonstrate that the government alone cannot eradicate corruption, but that a broader co‑operation is needed across sectors, involving CSOs, the private sectors and citizens. The National Anti-Corruption Policy of the Slovak Republic 2019–2023 recognises this challenge and states explicitly: “It is taken into consideration that the effectiveness and efficiency of the implementation of any anti-corruption policy is increased when it covers all sectors of public authority, civil society and business. Successful implementation of the Anti-Corruption Policy requires active involvement of and co‑operation between all stakeholders and shall be supported by their proactive and trustful commitment to act against corruption practices so that room and opportunities for corruption are restricted.” (ACP, p.4)

In line with these objectives, this chapter focuses on fostering integrity in civil society organisations and companies, as well as how the education system can contribute to a cultural change towards public integrity values.

Ensuring public integrity standards in civil society organisations

The impact and credibility of CSOs goes hand in hand with their own adherence to public integrity standards. The lack of transparency in their mission and sources of funding can lead to perceptions that CSOs are a vehicle for the pursuit of private interests, linked to certain industries, companies or political actors. Furthermore, fraud, waste and poor management practices in a CSO can detrimentally affect not only the CSO in question, but also the reputation of the entire civil society sector.

Establishing proportionate rules and controls in line with the civil society organisations’ characteristics

Governments can use legislative frameworks to promote integrity within CSOs in various ways, such as by subjecting them to anti-corruption laws in which they are considered legal persons, and by requiring them to have a sound governance structure. This structure can include clear lines of accountability, integrity standards, internal control and risk management measures, as well as transparency regarding their activities and the use of funds (OECD, 2020[1]).

At a minimum, CSOs could deploy basic governance structures, such as an elected board, confirm accountability and transparency requirements through financial audits and the issuing of annual reports, establish clear rules for avoiding conflicts of interest, and adhere to their legal statutes and other guidelines of duty (Global Standard for CSO Accountability, n.d.[6]).

In the Slovak Republic, there are currently no transparency requirements related to funding sources and activities. Some CSOs publish their annual reports and funding sources, while others do not. Ensuring structural transparency in CSOs should be a priority, as failure to do so negatively impacts the CSOs’ credibility as anti-corruption advocates and limits their capacity to represent the interests of citizens.

One way to enhance transparency is requiring CSOs to publish and disclose information relevant to integrity and good governance, including funding sources, annual reports, annual activities, and staff members. In recent years, the Slovak government has taken steps towards establishing audit and financial reporting standards for CSOs. For example, it has imposed restrictions on political donations to CSOs (The Electoral Knowledge Network, 2021[7]).

In addition, the Slovak government could establish a set of proportionate rules and controls that take into account the size of CSOs. At the moment, CSOs are subject to the same reporting requirements regardless of their size. This approach does not take into account proportionality and may limit the capacity of smaller CSOs as anti-corruption stakeholders due to their lack of expertise, human and financial resources.

Furthermore, the need to establish proportionate rules and controls represents a good opportunity for the Slovak Republic to open a dialogue with CSOs and consult them on transparency and publication requirements. This will enhance co‑operation with the sector and enable smaller CSOs to voice their demands to be treated according to their available resources.

Since its establishment in 2011 as part of the Ministry of Interior, the Office of the Plenipotentiary for the Development of the Civil Society has focused on strengthening the participation of CSOs in the public matters of the Slovak Republic. Given its experience and role, the Office may continue to play a leadership role and spearhead the consultation process with CSOs on proportionate rules and controls.

Engaging with the private sector to strengthen public integrity

Corruption negatively affects the business environment, as it distorts markets, undermines competition, and discourages investments. Addressing corruption and integrity challenges in the private sector is beneficial, not only for the business sector itself, but for governments and society at large. In this regard, a whole-of-society culture of integrity requires governments partnering with the private sector to ensure that its engagement with the public sector respects the shared ethical norms, principles and values of society (OECD 2017). This approach involves the close collaboration between the government and the private sector actors to understand each other’s needs and demands, and mutually support each other. For these reasons, the private sector plays a key role in the public integrity system.

The business integrity challenges in the Slovak Republic are significant. Commonly faced problems by companies doing business in the Slovak Republic include fast-changing legislation and policies (77%), complexity of administrative procedures (74%), and corruption (53%) (European Commission, 2020[4]). These challenges, and the high levels of perceived corruption in particular, undermine economic growth and hamper the business environment of companies operating in the Slovak Republic.

These challenges are reflected in the Slovak Republic’s fight against corruption. As stated in the “Anti-Corruption Policy of the Slovak Republic for 2019 - 2023”, the Slovak Republic has a strong commitment to improve the business environment, by reducing the opportunities for corruption and promoting integrity in the interface between private and public sectors, such as in public procurement, licensing, concessions, subsidies. The following recommendations aim at supporting the Slovak Republic in promoting a culture of integrity in the private sector.

The Slovak Republic could update the legal framework to include incentives for corporate compliance with public integrity standards

Establishing a coherent legislative framework for public integrity is an essential step to support integrity in companies. The legal framework can both set legal requirements and standards for business integrity practices, and provide incentives for companies to implement those practices, for example related to risk management, codes of conduct, whistleblower protection, and compliance systems.

An example of a standard-setting law is the Sapin II law in France (see Box 4.1). The law established the French Anti-Corruption Agency (AFA), which facilitates and controls the implementation of anti-corruption and compliance frameworks under the Sapin II law (OECD, 2020[1]). The law requires companies of a certain size to establish an anti-corruption programme, to identify and manage corruption risks, and to apply sanctions for non-compliance. Moreover, under specific circumstances the Sapin II law requires the implementation of corporate compliance programmes and permits corporations to enter into a court settlement of public interest (Convention judiciaire d'intérêt public) (AFA, 2021[8]).

Box 4.1. Sapin II Law in France promoting business integrity

On December 9th 2016, the French government promulgated a new anti-corruption law, called the “Loi Sapin II pour la transparence de la vie économique” (“Sapin II”), to significantly strengthen and improve the anti-corruption framework in France.

Under Sapin II, a compliance programme to fight corruption is a legal requirement for companies of a certain size. It requires these companies to establish an anti-corruption programme and to identify and manage corruption risks. Essential components of a corporate compliance programme include setting the company’s top management’s commitment to preventing and detecting corruption, having an anti-corruption code of conduct, developing an internal whistleblowing system, establishing an internal and monitoring system, and developing third-party due diligence procedures, among others.

Furthermore, the law establishes the French Anti-Corruption Agency (AFA), which operates under the French Minister of Justice and the Minister of Budget. AFA is responsible for monitoring the implementation of anti-corruption and compliance frameworks in the private and public sectors, with powers to control and levy sanctions.

AFA has a three-fold mission: first, to assist to the competent authorities and persons concerned with the prevention and detection of acts of corruption in the broad sense of the term; second, to control the proper implementation of an anti-corruption compliance programmes for companies; and, third, to ensure compliance with the French Blocking Statute (Law no. 68-678/1968), which governs the procedure for communicating sensitive information outside France. Within this scope, AFA can hold companies liable for failure to implement an efficient anti-corruption programme even if no corrupt activity has taken place (OECD, 2020[1]).

Source: (AFA, 2020[9])

Furthermore, legal sanctions and incentives both signal to the private sector a government’s commitment to strengthening corporate integrity and reducing the incidence of corruption involving the private sector. Legal sanctions and incentives for business integrity may therefore serve as tools to drive cultural change and promote integrity in the private sector (see Box 4.2; (UNODC, 2013[10])).

Box 4.2. Legal sanctions and incentives for business integrity

Governments across the world are using both legal sanctions and incentives to promote business integrity practices.

Sanctions

Sanctions need to be “effective, proportionate and dissuasive” and may consist of a mix, including monetary fines, incarceration, confiscation of ill-gotten gains, and remedial measures that compensate victims of corruption. Suspension and debarment can also be used, as a measure to prevent an individual or company from participating in government contracts, subcontracts, loans, grants and other assistance programmes. Other sanctions fall under the category of contract remedies, for example by terminating a contract on grounds of legal breaches.

Taken together, these sanctions should be of sufficient magnitude to deter future misconduct. In this regard, organisational size will often be a critical factor. Measures adequate to deter future violations by a small local business generally would be inadequate for a larger company. Conversely, the substantial penalties appropriate to a large national or multinational company would be disproportionate for a smaller enterprise.

Incentives

Incentives that reward a company for good practice are an important complement to enforcement sanctions. They recognize that meaningful commitment to and investment in anti-corruption programmes and other measures that strengthen corporate integrity are largely voluntary and can be encouraged through inducements that signal their priority to company leadership. Four main types of incentives can be identified:

Penalty mitigation: Companies that have made a significant effort to detect and deter corruption may be rewarded with a reduction in fines, reduced charges or even a defence against liability for the misconduct of an employee or agent. In a settlement context, the perception that a company is serious about countering corruption can substantially ease the conditions for resolving an investigation.

Procurement incentives: Companies that demonstrate a meaningful commitment to integrity practices can benefit in procurement procedures, in the form of an eligibility requirement or and affirmative competitive preference.

Preferential access to government benefits: government benefits can be made available on a preferential basis to individuals and companies that are able to demonstrate a commitment to good practices of business integrity. This incentive may take the form of an eligibility requirement, for example, that an applicant for government benefits meets specified minimum programme standards.

Reputational incentives: These are a type of benefit that encourage corporate integrity, through public acknowledgement of a company’s commitment to integrity and combating corruption.

Source: UNODC (2013[10]), A Resource Guide on State Measures for Strengthening Corporate Integrity, https://www.unodc.org/documents/corruption/Publications/2013/Resource_Guide_on_State_Measures_for_Strengthening_Corporate_Integrity.pdf

In the Slovak Republic, the legal framework for corruption prevention in the private sector is covered in the Slovak Penal Code (Act No. 301/2005 Coll., as amended), and the code of Criminal Procedure (Act No. 301/2005 Coll., as amended). These laws criminalise corruption, extortion, active and passive bribery, bribery of foreign officials, conflicts of interest, facilitation payments, giving and receiving gifts, and money laundering. Furthermore, the Slovak Republic introduced criminal liability for legal entities in 2016 by adopting the Act on Criminal Liability of Legal Persons (Act No. 91/2016 Coll).

However, there is no specific Slovak legislation on the establishment and implementation of anti-corruption and compliance programmes in the private sector. Therefore, the Slovak Republic may update its legal framework to set the legal standards, sanctions and incentives for business integrity, as well as to create the institutional conditions for supporting, controlling and monitoring the implementation of the law. This is in line with the ACP 2019-2023, which stipulates under Priority 3: Improve conditions for entrepreneurship:

Measure 3.3. In co‑operation with the representatives of the Rule of Law Initiative, establish criteria and measures to reduce corruption in companies’ commercial relations with State entities and the organisations established thereby.

Measure 3.4. Entail an anti-corruption clause in contracts concluded with State entities and the organisations established thereby.

As with the example of Sapin II, the legislation may need to take into account the principle of proportionality, as it is for SMEs not feasible to meet the same standards as large companies. The latter benefit from economies of scale to conduct the required legal, administrative and operational work that comes with setting up and running an effective anti-corruption and compliance programme. SMEs often do not have these capacities.

The Slovak Republic could provide guidance to help companies implement business integrity practices

Beyond a set of legal requirements, sanctions and incentives, governments can also provide guidance and support to companies for establishing anti-corruption and compliance programmes. These support measures can take various forms. In France, the AFA offers a wide range of support services, from knowledge products such as guidelines on the legal framework, to training and tailor-made support (see Box 4.3).

Box 4.3. AFA’s guidance to support business integrity in France

The French Anti-Corruption Agency AFA holds a double mission to strengthen business integrity. On the one hand, as part of its control mandate, AFA verifies the existence and quality of the anti-corruption and compliance systems set up by companies in accordance with the Sapin II Law. On the other hand, AFA provides assistance and advisory services to businesses, to support them in implementing anti-corruption and compliance measures.

In particular, in line with this second mission, AFA activities include:

Development of recommendations and practical guides for companies, which, together with the Sapin II law and its implementing decrees, constitute the French anti-corruption framework. All publications aimed at private sector actors have been subject to a public consultation process. Practical examples of these include:

The anti-corruption and compliance function in companies.

Anti-corruption checks in the context of mergers and acquisitions.

Gifts and hospitality policy in private companies, public companies, associations and foundations.

Awareness-raising and training activities for various types of private actors. These actions are aimed at strengthening the private sector’s ownership in the fight against corruption and the challenges it faces when navigating the French anti-corruption framework. Practical examples of these include:

General presentations of anti-corruption issues and the French anti-corruption legal framework.

Technical workshops organised for professionals (e.g. on internal control systems, corporate gifts and invitations).

Workshops organised together with professional organisations and associations and participation at events organised by the private sector (e.g. conferences, seminars).

Specialised training courses aimed at both beginner and advanced audiences.

Helpdesk-style legal and technical support in response to questions from private sector actors regarding corruption prevention and compliance programmes.

Tailored, on-demand support to private sector actors in the implementation of anti-corruption compliance programmes on a voluntarily basis. These individual support actions for companies are provided depending on the private sector actor’s technical needs and the required scope of the support. Support is offered for free and for a limited time period, ranging from a few months to a year. Independent of its control action, the individual support actions carried out by the agency do not lead to any certification or labelling. Since 2018, AFA has supported around 20 private sector actors of different sizes and sectors of activity.

Source: Information directly provided by the French Anti-Corruption Agency AFA; (AFA, 2021[8])

Similarly, in the UK, the Business Integrity Initiative targets specifically micro, small and medium-sized enterprises (MSMEs), and offers practical guidance and even financial incentives (see Box 4.4).

Box 4.4. The UK Business Integrity Initiative

The UK Business Integrity Initiative is a cross-government collaboration launched in 2018 to promote integrity in the private sector. The goal of the initiative is to provide practical guidance to micro, small and medium-sized enterprises (MSMEs) trading with and investing in new markets on issues such as corruption and human rights.

As part of the Business Integrity Initiative, practical anti-corruption guidance is provided to MSMEs in the following three areas:

Prevention guidance: Services can include consultation on how to assess a company’s bribery and corruption risks and the status of current controls, as well as information on corruption risks in specific countries or sectors.

Compliance guidance: Services can include training and guidance on how to comply with the UK Bribery Act and other relevant anti-corruption laws and regulations. The aim is to reduce the risks of legal liability and penalties for firms and individuals, and guide on remedial strategies to address situations when things go wrong.

Collective Action guidance: Anti-corruption Collective Action involves multi-stakeholder collaboration to promote fair competition and tackle corruption risks in overseas markets. Services can include hands-on support for launching new anti-corruption Collective Action Initiatives, engaging in existing Initiatives and setting up sustainable public-private dialogue mechanisms to advocate for policy reforms in target countries.

Business Integrity Consultancy Service

As part of the Business Integrity Initiative, the UK government committed to provide match funding between 60% and 80%, depending on company size, for up to five days of consultancy guidance (or ten days in the case of Collective Action guidance). To be eligible for these services, a business should qualify as an MSME (up to 250 employees with a turnover of up to GBP 44 million) and invest in or trade with countries that receive official development assistance. The consultancy services are provided by the Basel Institute on Governance, and include:

Help to improve companies’ compliance with the UK Bribery Act.

Detailed information on corruption risks in specific countries or sectors and assistance in developing mitigation strategies.

guidance on how to do due diligence assessments on supply chain partners.

Source: UK Government (2019) Anti-corruption newsletter, Summer 2019; FCPA, 2019. https://fcpablog.com/2019/05/07/resource-alert-guidance-from-uk-government-and-basel-institu/

In Greece, various business integrity resource materials for companies have been developed, including guidelines on risk management, codes of conduct and whistleblower protection (see Box 4.5).

Box 4.5. Business integrity guidelines in Greece

In 2016, Greece, the OECD, and the European Commission launched a project to increase integrity and reduce corruption in Greece through technical empowerment of the Greek authorities for the implementation of the National Anti-Corruption Action Plan (NACAP). The project was completed in January 2018. As part of this project, the OECD, together with Greece and the European Commission, developed a series of documents to help fight corruption in the private sector in Greece. These publications include:

Anti-Corruption Guidelines on Compliance, Internal Controls and Ethics for Companies in Greece: These Guidelines have been developed to help companies in Greece implement effective compliance measures to tackle corruption and bribery. They also contain recommendations on how the public and private sector can work together to ensure the fight against corruption is sustainable.

Corruption Risk Review and Risk Assessment Guidelines for Companies in Greece: This document analyses corruption risks in Greece. It also provides guidance to companies in Greece to help them successfully conduct a risk assessment and implement effective anti-corruption measures based on the results of the risk assessment.

Guidelines on Whistleblower Protection for Companies in Greece: These Guidelines are designed to assist companies in Greece in developing and implementing effective internal reporting mechanisms. The Guidelines reflect current international standards and good practices in whistleblower protection and should also be relevant and adaptable for companies operating in numerous jurisdictions.

In the Slovak Republic, partly due to the absence of advanced business integrity legislation, there are currently no specific guidelines issued by the government to support the establishment and implementation of business integrity practices in companies. However, there are a number of organisations, such as the Rule of Law Initiative and the Slovak Compliance Circle, that have provided training and guidance on an ad-hoc basis to Slovak companies on business integrity standards and practices.

While acknowledging these valuable activities, the government itself may step up its efforts in providing guidance and support to companies on business integrity. As highlighted by the examples above, this guidance can take various shapes and forms, including providing a template for a code of conduct for companies, guidelines on risk management, repository of good practices and examples on anti-corruption due diligence and on responsible business conduct, business coaching, and training. Furthermore, both online and physical peer learning events such as forums and roundtables can serve as a stocktaking of emerging challenges and business needs. Particular guidance may be offered to SMEs, given their limited capacity to deal with legal, administrative and operational aspects of anti-corruption and compliance systems. For all these support activities, sufficient resources need to be foreseen and earmarked in the budget (cfr. Chapter 1).

The need to develop guidance for the business sector represents a good opportunity for the Slovak Republic to strengthen the dialogue with private sector actors and consult them about the risks, needs and feasibility of measures. The Government Office, as co‑ordinating body for corruption prevention, and the Ministry of Economy can play a leadership role and spearhead this consultation process, ensuring involvement of all relevant actors, including the Slovak Business Agency SBA, the Rule of Law Initiative, chambers of commerce and civil society organisations. The proposed dialogue has the potential to become a permanent platform on business integrity. Overall, this suggestion is in line with point No. B.10 of the Government Resolution No. 426 of 4 September 2019 to the National Anti-Corruption Programme, which obliges the Ministers of Economy, Justice, Finance, Interior and the Head of the Government Office to “identify and analyse the causes of corrupt behaviour in the private sector and propose relevant anti-corruption measures thereto”. The suggestion also relates to point B.12, which obliges the Head of the Government Office and the members of the Government, [...] “in co‑operation with the entities associated within the Rule of Law Initiative, and with the academic community, to identify shortcomings of compliance with principles of the rule of law; to propose and adopt specific remedial measures; and to incorporate them into sectoral anti-corruption programs.”

To support companies in adopting anti-corruption and compliance programmes into core business operations, the Slovak Republic could incorporate an “integrity culture” perspective when providing guidance to companies. This entails moving beyond a focus on formal compliance, and encouraging companies to address the informal aspects of their organisational culture that could undermine public integrity (OECD, 2020[1]). For instance, this would include, but not limited to, management commitment, rewards and bonus structures, organisational voice and silence factors, internal team dynamics, and external relationships with stakeholders (Taylor, 2017[11]). Table 4.1 provides further details on each of these factors. This approach is in line with the Slovak ACP 2019-2023, which seeks to promote a culture of integrity.

Table 4.1. Business Integrity: the five levels of an ethical culture

|

Level |

Description |

|---|---|

|

Individual |

How individual employees are measured and rewarded is a key factor that sustains or undermines ethical culture. In the face of pressure to meet growth targets by any means necessary – a belief that the ends justify the means – unethical behaviour is to be expected. Therefore, the rewards system is an excellent place to start. Diversity and inclusion initiatives enable individual employees to bring their whole selves to work: employees who feel it unnecessary to hide aspects of their social identity to fit into the dominant culture will experience less conflict between personal and organisational values and will express themselves more confidently – making them more inclined to raise concerns about ethics. |

|

Interpersonal |

Organisations can also focus on how employees interact across the hierarchy. Abuse of power and authority is a key factor that degrades organisational culture. When decisions around promotions and rewards seem unfair and political, employees disregard organisational statements about values and begin pursuing their own agendas. Building an ethical culture from an interpersonal perspective requires meaningful protections that empower all employees and stakeholders, even the least powerful, to raise concerns and express grievances. Leaders must recognise the outsized role they play in setting culture and driving adherence to ethics, and they must learn to exercise influence carefully. |

|

Group |

Socialisation into group membership and relationship is a core aspect of human culture. At work, the key determinant tends to be an employee’s group or team. As organisations become more geographically diffuse and loosely aligned, it becomes harder to set and define consistent organisational culture. Focusing on team conditions an empower middle managers to feel responsible for changing culture and group dynamics to foster more effective ways of working. |

|

Intergroup |

The quality of relationships among groups is critical to consider in any attempt to build an ethical culture. Celebrating a team whose high performance may stem from questionable conduct gives it the power and a mystique that is difficult to challenge, and this can undermine values across the organisation. Teams working in sustainability or compliance often need to scrape for power and resources; when members are attached to matrixed working groups, accountability can get watered down. |

|

Inter-organisational |

Most discussions of organisational culture focus on internal relationships. Still, employees are keenly conscious of how a company treats suppliers, customers, competitors, and civil society stakeholders, so building and maintaining stakeholder trust will improve organisational culture. Moreover, companies need to ensure that their values and mission statements amount to more than words on a website. Business success and core values are not contradictory concepts. That said, building an ethical culture sometimes means walking away from lucrative opportunities. Companies can be sure their employees will notice. |

Source: (Taylor, 2017[11])

The Ministry of Economy could strengthen the evidence base on business integrity practices and challenges

In order to develop effective legislation and policy measures for business integrity, information and data are needed related to the understanding of companies of integrity risks, the prevalence of compliance systems, and the specific needs and challenges for various categories of companies, depending on size and sector. Data and information also allow to measure progress over time and to identify where additional attention and resources should be spent. Lastly, recurrent measurement can also assess progress in terms of implementation of (forthcoming) domestic legislation and international standards.

In the Slovak Republic, there is currently no government information available about business integrity practices and challenges. As presented above, certain perception data are available from the EU Corruption Barometer, and the Faculty of Management of Comenius University in Bratislava has published a relatively small number of studies on business integrity with support from the government.1 Further data on the extent to which companies have anti-corruption and compliance programmes in place, disaggregated by size and sector, as well as on the quality of those programmes, would be insightful for prospective policies. Similarly, the motivations for corrupt behaviour could be better understood, and well as the difficulties in implementing anti-corruption and compliance programmes. Furthermore, it is not yet well-documented what companies of different sizes and sectors expect in terms of government support for business integrity.

This need for further evidence and insights to inform policy making is reflected in point No. B.10 of the Government Resolution No. 426 of 4 September 2019 to the National Anti-Corruption Programme, which obliges the Ministers of Economy, Justice, Finance, Interior and the Head of the Government Office to “identify and analyse the causes of corrupt behaviour in the private sector and propose relevant anti-corruption measures thereto” (by 31 December 2022).

Given its prominent role for business integrity in the Slovak Republic, the Ministry of Economy could take the lead in further strengthening the evidence base on business integrity practices and challenges. The French experience of a national survey on business integrity run by the French Anti-Corruption Agency may serve as an example of a government-led survey (see Box 4.6).

Box 4.6. The AFA’s efforts to measure business integrity practices in France

In order to better understand the challenges related to business integrity practices in France, the French Anti-Corruption Agency AFA carried out a national survey in 2020, a first of its kind. The survey analyses the understanding of corruption risks and the legal framework, as well as the maturity of the anti-corruption compliance programmes among private sector companies in France.

Open to companies regardless of their size, the survey consisted of an anonymous questionnaire that was accessible online. Professional organisations were key partners in the dissemination of the survey and actively engaged in communication activities mobilising their membership. As a result, more than 2 000 companies were reached, and around 400 companies, including SMEs, provided actionable responses.

The survey resulted in key insights on the business integrity landscape in France, including:

While companies reported that they were familiar with corruption offences stipulated in the Sapin II law and that 70% of them have an anti-corruption compliance programme in place, these compliance programmes tended to be incomplete in areas such as risk mapping and third party risk management.

The position of the head of the compliance function is crucial in the implementation of effective compliance systems and needs to be strengthened.

SMEs (who are not subject to the compliance obligations set out in Article 17 of the Sapin II law) seemed to be lagging behind in the implementation of the anti-corruption compliance programmes.

The results of the 2020 survey will serve as a benchmark for measuring progress and gaps in business integrity in the future, and have already informed the 2021 priorities and recommendations of the AFA on business integrity.

Source: Information directly provided by the AFA; AFA (2020) National diagnostic survey of anti-corruption systems in businesses, https://www.agence-francaise-anticorruption.gouv.fr/files/2021-03/National%20Diagnostic.pdf

Alternatively, in particular given the scepticism from the private sector towards the government in the Slovak Republic, the Ministry of Economy could take the lead in further strengthening the co‑operation with the academic community. Research on business integrity could be part of a multi-annual agreement that allows for a recurrent measurement of the business integrity practices and challenges faced by domestic and foreign companies in the Slovak Republic. The research package may also focus on particular risk areas, such as service delivery (permits, licenses) or customs, specific sectors, or types of companies (e.g. SMEs). The academic partner or consortium may serve as a safeguard of the independence and methodological soundness of the research, whereas other stakeholders such as sector federations, unions of employers, and civil society organisations can help disseminate both the surveys and the results.

The Corruption Prevention Department, together with the Ministry of Economy, could develop an awareness raising campaign on business integrity

Within the private sector in the Slovak Republic, knowledge about the benefits of integrity and compliance programmes remains limited, particularly amongst domestic companies and SMEs. To that end, the Corruption Prevention Department, together with the Ministry of Economy, could implement an awareness raising campaign on public integrity responsibilities for the private sector.

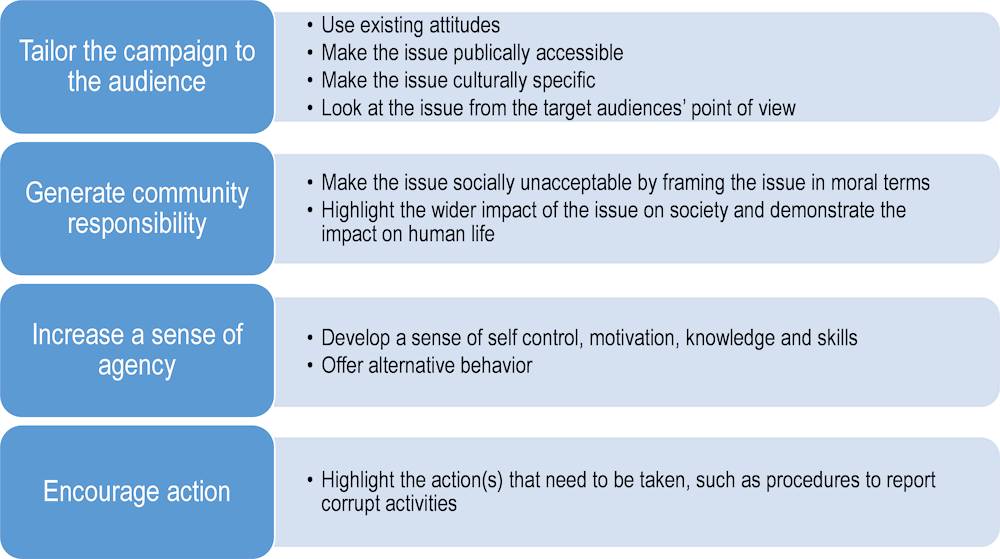

As there is reportedly widespread justification for integrity breaches in the business sector in Slovak Republic, the strategy of awareness raising should be twofold. The first aim should be to generate community responsibility among the private sector, focusing on corruption’s costs to the economy and society (see Figure 4.1). The awareness-raising campaigns should not sensationalise the issue and instead employ credible and authentic evidence, to enable recipients to identify with the core messages. Moreover, challenging the social norms that justify integrity breaches, bribery, and the reliance on corrupt business practices will be crucial, as much as it will be important to create a link between one’s own integrity and the wider public benefit. In the case of corrupt behaviour, the damage done often remains abstract and not directly linked to another individual, thereby facilitating justification. Challenging these behavioural caveats therefore requires linking awareness-raising to actual dilemmas where citizens and companies understand how their actions can have a negative impact on the business environment and on society (OECD, 2020[1]).

The second aim should be to increase business’ agency by developing individual motivation and encouraging action (see Figure 4.1). This should go beyond communicating about the prevalence of corruption and the government’s efforts to prevent it, and offer tangible solutions and benefits for companies to uphold public integrity. This could be accomplished for example by offering different solutions (such as how to report corruption or how to work with public officials to uphold integrity), identifying alternative behaviours to corruption, or highlighting reputational benefits for the company as a business advantage.

Figure 4.1. Success factors in behaviour changing campaigns

Furthermore, given the general distrust among companies towards the government, an awareness raising campaign would need to be founded in both facts and policies in order to be perceived as credible, and not merely as public relations by the government. The research mentioned above could inform the facts, for example on frequent corruption offences or common integrity challenges among companies. The policies would help demonstrate that the government is taking action itself as well, including to eradicate corruption in the public sector. For example, new policies and initiatives on business integrity incentives, whistleblower protection or lobbying could provide a suitable momentum for communication, underlining the responsibilities of both public and private sectors. For each of the (sub)campaigns, the strategy should identify the expected outcomes (e.g. attitudes or behaviours to change, skills to develop), the target audiences, the key messages and the communication channels (e.g. television, web, social media, print media) as well as the evaluation mechanisms (e.g. opinion surveys, web analytics, participation in events, number of complaints submitted, etc.).

The credibility of an awareness raising campaign may also benefit from mobilising, or even outsourcing to, reliable partners, such as the Rule of Law Initiative, or sector federations, and private sector role models, to disseminate the key messages. Various outlets and media channels of these partners could be used and combined, from newsletters of sector federations to social media accounts of respected thought leaders.

Mainstreaming public integrity into the curriculum

A whole-of-society approach to public integrity also includes engaging young people through the education system. Evidence has found that civic education programmes can increase the likelihood of young people rejecting corruption in government, as well as diminish their likelihood of accepting or participating in lawbreaking activities (Ainley, Schulz and Friedman, 2011[13]; Fraillon, Schulz and Ainley, 2009[14]). To this end, incorporating integrity education into school curriculum is a key tool, as it equips young people with the knowledge and skills needed to face the challenges of society, including corruption.

Education about public integrity and anti-corruption can help challenge entrenched social norms that enable corruption to flourish. Such education can be found in the schools (e.g. in the existing curriculum or through extra-curricular activities), or through tools offered independently (such as initiatives by civil society organisations). Education about public integrity and anti-corruption generates new common knowledge about the expected norms and behaviours to prevent corruption. It also cultivates lifelong skills and values for integrity, encouraging young citizens to accept their roles and responsibilities for rejecting corruption.

The National Institute for Education (SPU) and the Stop Corruption Foundation could establish a multi-stakeholder group with responsibilities for strengthening current efforts on education for integrity

The education system in the Slovak Republic is a two-level model of education, which comprises the state and school levels. At the state level, the National Institute for Education (SPU) (an expert group under the Ministry of Education, Research and Sport) sets out the state educational programme (SEP), which is the main curriculum document for the country. The SEP is then developed into school specific education, through the school educational programme (SchEP). The SchEP is prepared by the pedagogical professionals within each school, in consultation with each school’s pedagogical council and school board. Each school’s headteacher issues the final SchEP.

The current SEP is comprised of seven educational areas: language and communication; mathematics and work with information; man and nature; man and society; man and values; arts and culture; and health and movement. Cross-cutting issues are also included in the SEP, and feature topics such as personal and social development (e.g. marriage and parenthood education), environmental education, media education, multicultural education and protection of life and health.

Recognising the existing entry points in the current SEP, the SPU and the Stop Corruption Foundation signed a memorandum of understanding in 2020 to prepare values education for Slovak schools.2 In particular, the project takes an interdisciplinary approach, including by incorporating education about integrity and values into the existing “Man and values” educational area, as well as across the six other educational areas. The aim of the project is to collect good practices from schools in educating about public integrity, values and anti-corruption. The good practices will be shared online as inspiration for other schools looking to implement public integrity, values and anti-corruption education into their curriculum, and will also be used to inform the development of new educational standards by the SPU. This project builds on existing work carried out by the SPU and the Stop Corruption Foundation, including developing a school ‘code of conduct’ for each school class, as well as a webinar on anti-corruption methodologies to build teacher knowledge.

Given the interdisciplinary nature of this work and focus on using the existing curriculum structure, the SPU and the Stop Corruption Foundation are encouraged to continue this work. Appropriate funding should be assigned, and key stakeholders should be involved to ensure that the revised standards reflect good practices and relevant anti-corruption and integrity knowledge. To that end, the SPU could convene a multi-stakeholder working group, consisting of representatives from the Corruption Prevention Department, the Interdepartmental Expert Group for Financial Literacy, local pedagogical councils, and CSOs (including the Stop Corruption Foundation). The example of Lithuania in Box 4.7 could serve as inspiration.

Box 4.7. Stakeholder co-operation to integrate integrity in the curriculum in Lithuania

A multi-stakeholder working group was established in Lithuania to strengthen the co-operation between stakeholders on education for anti-corruption and public integrity. This group included the anti-corruption body (the Special Investigation Service or STT), the Modern Didactics Centre (MDC), [a non-governmental centre of excellence for curriculum and teaching methods], and a select group of teachers, who worked together to integrate anti-corruption concepts into core subjects like history, civics and ethics.

This effort was part of the Anti-Corruption Education Project, an initiative launched under the guidelines of the Law of Corruption Prevention, which states that ‘Raising anti-corruption awareness is an integrated part of society’s education in order to develop individual ethics and citizenship, understanding of personal rights and responsibilities for society and State, in order to maintain the implementation of corruption prevention goals’.

From 2002, the group designed a training course for teachers on anti-corruption to familiarise them with the anti-corruption laws and legislation, definitions and concepts. Following this, the group mapped the national curriculum to identify areas where concepts about values (fairness, honesty, and impact on community) and anti-corruption could be integrated naturally.

Once the initial curriculum was developed, teachers tested the curriculum in their classrooms over a 6 month pilot period and refined the lessons based on the responses of the students. Over the years, the programme has expanded from classroom-based learning to engaging students with local anti-corruption NGOs and municipal governments to apply their knowledge in a tangible way. For example, students in one city were involved in working with a civil servant, inspecting employee logs to check for irregularities and potential areas of abuse of public resources, such as government vehicles and fuel cards.

Sources: (OECD, 2019[15]; Poisson, 2003[16])

The working group could be tasked with using the lessons learned and good practices to develop new learning outcomes and guidance material for schools, such as suggested lesson plans and tasks. The learning outcomes could build on what has worked already, and could also take inspiration from the OECD education for integrity learning outcomes (see Table 4.2). The guidance material could build on the learning outcomes, and incorporate lesson plans built around an inquiry-based learning model, to emphasise engaging students in a practical way, so they are able to see the impact of integrity actions. For example, activities such as games, role-play scenarios and debates could be incorporated into lesson plans. Good practice also includes the adaption of materials to the local situation and the pursuit of community-based projects, examples of which include a visit to a local government office to oversee reporting registers, or the preparation of an access to information request (OECD, 2018[17]).

Table 4.2. Suggested learning outcomes for education about public integrity

|

Core Learning Outcome 1: Students can form and defend public integrity value positions and act consistently upon these, regardless of the messaging and attractions of other options. |

||

|---|---|---|

|

Sub-learning outcomes and indicators for achievement |

Students can explain their own public integrity values, those of others, and of society, and what they look like when they are applied |

|

|

Students can identify the public integrity values that promote public good over private gain Students can describe the institutions and processes that are designed to protect public good |

|

|

|

Students can construct and implement processes that comply with their own public integrity value positions and those of society |

|

|

|

Students can apply intellectual skills in regards to the defence of public integrity values |

|

|

|

Core Learning Outcome 2: Students can apply their value positions to evaluate for possible corruption and take appropriate action to fight it |

||

|

Sub-learning outcomes and indicators for achievement |

Students can define corruption and compare it with immoral or illegal behaviour |

|

|

Students can compare and determine the major different mechanisms in corruption |

|

|

|

Students can describe and evaluate consequences of corruption on a whole country |

|

|

|

Students can identify the likely signs of corruption |

|

|

|

Students can describe ways to, and suggest strategies for, fighting corruption |

|

|

|

Students can identify who and/or to which organisations corruption should be reported |

|

|

|

Students can explain the purpose and function of integrity policies |

|

|

Source: (OECD, 2018[17])

The multi-stakeholder working group could be tasked with developing training for educators and a corresponding framework to monitor and evaluate the impact of the training programme

The successful implementation of education about public integrity is dependent upon teachers who can effectively deliver the curriculum in the classroom. Teacher training on anti-corruption and integrity concepts, as well as on how to address difficult social topics in the classroom, is therefore a crucial component to the curriculum efforts. Teacher training can equip trainee and experienced professionals with the skills, knowledge and confidence to counter contemporary social problems, such as corruption (Starkey, 2013[18]). Training on integrity and anti-corruption can also introduce normative standards to teachers, such as the norm that they have moral obligations to challenge corruption and help their students navigate the difficult ethical dilemmas they encounter. Teacher training can take many forms, ranging from courses taken during teacher trainee programmes and professional raining, to seminars and resource kits prepared by government institutions and/or civil society actors.

In the Slovak Republic, several anti-corruption training events for teachers have been organised. In 2018, the “Ethical and Civic Dimension of Corruption and Fraud in Schools” was organised as part of the 2018 Advocacy Week to disseminate knowledge and raise awareness among teachers. Funded by the Council of Europe (ETINED platform), the event included two modules on the “Ethics and Corruption in the School Environment” for ethics teachers and the “Legal Instruments for the Fight against Corruption” for civics teachers.

As part of the ongoing project with SPU and the Stop Corruption Foundation, additional training on public integrity and anti-corruption for educators are under development. Indeed, successful implementation depends on regular training that is available for all teachers involved in delivering public integrity education. To that end, as part of the efforts to update the guidance on integrity education, the working group could develop a training course for educators. This training course could incorporate up-to-date knowledge on integrity values and anti-corruption, guidance on how to deliver the material in a relevant and engaging manner, and guidance on how to ensure an open classroom environment and handle difficult and sensitive conversations (see Box 4.8).

Box 4.8. Creating an open classroom and school environment

An open classroom and school environment are core components of an effective education about public integrity and anti-corruption programme. An open environment has been found to encourage learning, with students sharing their personal experiences and learning from one another. Additionally, an open environment can model the expected behaviours and norms of a democratic society, which can have a positive influence on assimilating these values and future civic behaviour (Ainley, Schulz and Friedman, 2009[19]). Experience from successful educational interventions highlights the role of an open school and classroom environment and identifies four core interrelated components for the planning and delivery of effective learning:

Facilitating an open classroom discourse and a dialogic pedagogy to enable students to open up about their values and insights.

Valuing and respecting students and their experiences, allowing them to leverage their contextual knowledge and experiences to inspire their citizenship action and engagement.

Ensuring a whole-of-school approach, where the school environment accords genuine rights and responsibilities to all its members, modelling democratic and respectful behaviours in all its actions. This component also advocates for a student voice that is not just listened to, but trusted and honoured.

Creating and sustaining a structure that supports teachers and other staff to engage in these processes and support the whole-of-school transformation, is also a critical element of an open school and classroom environment (Deakin Crick, Taylor and Ritchie, 2004[20]).

Evidence has also found that students who learn in an open classroom environment develop qualities of empathy, critical thinking, the ability to understand the beliefs, interests and vies of others, as well as the ability to reason about controversial issues and choose different alternatives (Van Driel, Darmody and Kerzil, 2016[21]).

To help build knowledge on effective training initiatives, the working group could accompany the training with a monitoring and evaluation framework, with indicators to measure teacher knowledge and skills relating to integrity and anti-corruption. The monitoring and evaluation framework would enable the government to identify which training form, content and deliver system works best; which are the specific challenges teachers face when delivering the anti-corruption education programmes in schools, and any potential regional differences that need to be addressed across the Slovak Republic. Indeed, as part of this framework, teachers could provide feedback on the received training courses and material, as well as any potential room for improvement.

Universities in the Slovak Republic could consider integrating courses on public integrity and anti-corruption into degree programmes

Students, researchers and universities play a key role in generating and disseminating knowledge on corruption. In addition, as future professionals, university students constitute a strategic target of anti-corruption training and awareness-raising activities. There is a wide range of best practices, including universities that have developed anti-corruption courses or integrated anti-corruption lectures into their regular study programmes. Evidence has found that integrating ethics education into university curricula can increase student exposure to a range of ethical issues and improve their ethical sensitivity, a critical component of the ethical decision-making process (Martinov-Bennie and Mladenovic, 2015[22]).

Given the autonomous nature of universities, the Ministry of Education, Research and Sports does not have jurisdiction over degree programmes. Therefore, including content on public integrity and anti-corruption into degree programmes is the responsibility of each university.

In this context, Slovak universities could consider developing develop modules on integrity and anti-corruption and mainstreaming these into existing programmes, such as law, economics, business, engineering and architecture, and public administration. Universities could draw on good practice and resources developed by the UN Anti-Corruption Initiative (ACAD) and Education for Justice (Box 4.9). These initiatives include extensive resource material which universities can draw upon to design their own modules. Where appropriate, the Ministry of Education, Research and Sports and the Corruption Prevention Department could support universities by sharing lessons learned, good practices and expertise on developing curricula at the primary and secondary school level.

Box 4.9. UNODC: Anti-Corruption Academic Initiative (ACAD) and Education for Justice

The ACAD initiative aims to facilitate exchange of curricula and best practices between university educators. ACAD is a collaborative academic project that aims to provide anti-corruption academic support mechanisms such as academic publications, case studies and reference materials that can be used by universities and other academic institutions in their existing academic programmes. In this manner, ACAD hopes to encourage the teaching of anti-corruption issues as part of courses across various disciplines such as law, business, criminology and political science and to mitigate the present lack of inter-disciplinary anti-corruption educational materials suitable for use at both undergraduate and graduate levels. ACAD has developed a full model course on anti-corruption, a thematically organised menu of resources and a variety of teaching tools; all availed freely on the web.

Similarly, UNODC’s Education for Justice (E4J) initiative includes a module series for universities on anti-corruption. The modules are developed for lecturers and connect theory to practice, encourage critical thinking, and use innovative and interactive teaching approaches such as experiential learning and group-based work. The modules cover a range of topics, including public sector corruption, private sector corruption, corruption and human rights, corruption and gender, and citizen participation in anti-corruption.

Source: (UNODC, n.d.[23]; UNODC, n.d.[24])

Proposals for action

Ensuring public integrity standards in civil society organisations

The Slovak Republic could establish proportionate rules and controls in line with the civil society organisations’ characteristics.

Engaging with the private sector to strengthen public integrity

The Slovak Republic could update the legal framework to include incentives for corporate compliance with public integrity standards.

The Slovak Republic could provide guidance to help companies implement business integrity practices.

The Ministry of Economy could strengthen the evidence base on business integrity practices and challenges.

The Corruption Prevention Department, together with the Ministry of Economy, could develop an awareness raising campaign on business integrity.

Mainstreaming public integrity into the curriculum

The National Institute for Education (SPU) and the Stop Corruption Foundation could establish a multi-stakeholder group with responsibilities for strengthening current efforts on education for integrity.

The National Institute for Education (SPU) could task the multi-stakeholder working group with developing training for educators and a corresponding framework to monitor and evaluate the impact of the training programme.

Universities in the Slovak Republic could consider integrating courses on public integrity and anti-corruption into degree programmes.

References

[8] AFA (2021), La convention judiciaire d’intérêt public, https://www.agence-francaise-anticorruption.gouv.fr/fr/convention-judiciaire-dinteret-public (accessed on 13 December 2021).

[9] AFA (2020), The French Anti-Corruption Agency Guidelines, https://www.agence-francaise-anticorruption.gouv.fr/files/files/French%20AC%20Agency%20Guidelines%20.pdf (accessed on 13 December 2021).

[13] Ainley, J., W. Schulz and T. Friedman (2011), ICCS 2009 Latin American Report: Civic knowledge and attitudes among lower-secondary students in six Latin American countries, IEA, Amsterdam.

[19] Ainley, J., W. Schulz and T. Friedman (2009), ICCS 2009 Encyclopedia Approaches to civic and citizenship education around the world, IEA, Amsterdam, http://pub.iea.nl/fileadmin/user_upload/Publications/Electronic_versions/ICCS_2009_Encyclopedia.pdf (accessed on 12 March 2018).

[20] Deakin Crick, R., M. Taylor and S. Ritchie (2004), A systematic review of the impact of citizenship education on the provision of schooling, EPPI-Centre, Social Science Research Unit, Institute of Education, https://eppi.ioe.ac.uk/cms/Portals/0/PDF%20reviews%20and%20summaries/cit_rv1.pdf?ver=2006-03-02-124739-170 (accessed on 12 March 2018).

[4] European Commission (2020), Flash Eurobarometer 482: Businesses’ attitudes towards corruption in the EU, European Commission , Brussels.

[3] European Commission (2019), Special Eurobarometer 502: Corruption, European Commission, Brussels, https://europa.eu/eurobarometer/surveys/detail/2247 (accessed on 16 December 2021).

[14] Fraillon, J., W. Schulz and J. Ainley (2009), ICCS 2009 Asian Report: Civic knowledge and attitudes among lower-secondary students in five Asian countries, IEA, Amsterdam, http://www.iea.nl/fileadmin/user_upload/Publications/Electronic_versions/ICCS_2009_Asian_Report.pdf.

[6] Global Standard for CSO Accountability (n.d.), Guidance Material, http://www.csostandard.org/guidance-material/#clusterc (accessed on 9 July 2019).

[12] Mann, C. (2011), Behaviour changing campaigns: success and failure factors, U4 Anti-Corruption Resource Centre, Bergen, http://www.u4.no/publications/behaviour-changing-campaigns-success-and-failure-factors/.

[22] Martinov-Bennie, N. and R. Mladenovic (2015), “Investigation of the impact of an ethical framework and an integrated ethics education on accounting students’ ethical sensitivity and judgment”, Journal of Business Ethics, Vol. 127/1.

[1] OECD (2020), OECD Public Integrity Handbook, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/ac8ed8e8-en.

[15] OECD (2019), OECD Integrity Review of Argentina: Achieving Systemic and Sustained Change, OECD Public Governance Reviews, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/g2g98ec3-en.

[17] OECD (2018), Education for Integrity: Teaching on Anti-Corruption, Values and the Rule of Law, OECD, Paris, http://www.oecd.org/governance/ethics/education-for-integrity-web.pdf (accessed on 19 April 2018).

[2] OECD (2017), OECD Recommendation of the Council on Public Integrity, http://www.oecd.org/gov/ethics/recommendation-public-integrity.htm.

[16] Poisson, M. (2003), Study Tour: What can be learnt from the Lithuanian experience to improve transparency in education?, UNESCO IIEP, Paris, https://etico.iiep.unesco.org/sites/default/files/2003_lithuania_study_tour_the_lithuanian_experience_to_improve_transparency_in_education_eng.pdf (accessed on 30 November 2021).

[5] Schwab, K., S. Zahidi and World Economic Forum (2020), The Global Competitiveness Report: How Countries are Performing on the Road to Recovery, World Economic Forum, https://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_TheGlobalCompetitivenessReport2020.pdf (accessed on 16 December 2021).

[18] Starkey, H. (2013), “Teaching the teachers”, in Sweeney, G., K. Despota and S. Lindner (eds.), Global Corruption Report: Education, Routledge.

[11] Taylor, A. (2017), “The Five Levels of an Ethical Culture About This Report”, BSR, San Francisco, https://www.bsr.org/reports/BSR_Ethical_Corporate_Culture_Five_Levels.pdf (accessed on 21 July 2017).

[7] The Electoral Knowledge Network (2021), Slovakia, https://aceproject.org/electoral-advice/CDCountry?set_language=en&topic=PC&country=SK (accessed on 13 December 2021).

[10] UNODC (2013), A Resource Guide on State Measures for Strengthening Corporate Integrity, https://www.unodc.org/documents/corruption/Publications/2013/Resource_Guide_on_State_Measures_for_Strengthening_Corporate_Integrity.pdf.

[24] UNODC (n.d.), E4J: University Module Series, https://www.unodc.org/e4j/en/tertiary/anti-corruption.html (accessed on 9 November 2021).

[23] UNODC (n.d.), Education, https://www.unodc.org/unodc/en/corruption/education.html (accessed on 9 November 2021).

[21] Van Driel, B., M. Darmody and J. Kerzil (2016), Education policies and practices tto foster tolerance, respect for diversity and civic responsibility in children and young people in the EU, Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg, https://doi.org/10.2766/46172.

Notes

← 1. The project Development of Business Ethics in the Slovak Business Environment can be found at the following website: https://www.fm.uniba.sk/en/research/research-projects-and-cooperation/national-projects/apvv-16-0091/.