This chapter assesses how the public administration works at the regional and local levels in the Czech Republic and suggests ways to improve its effectiveness, including multi-level governance mechanisms to support more efficient policy delivery. For this, the chapter describes the subnational governance structure and the system of the delegation of competences. Considering the strong administrative fragmentation at the local level, the chapter focuses particularly on inter-municipal co-operation, co-ordination among levels of government and strategic planning practices at all levels. The chapter also assesses subnational governments’ capacity and their ability to engage local stakeholders.

OECD Public Governance Reviews: Czech Republic

4. Public Administration at the Local and Regional Level in the Czech Republic

Abstract

A complex multi-level governance system

After 1989, the Czech Republic transitioned from a centralised system towards a decentralised system of self-governing subnational governments. Since the change in the political regime in 1989, the Czech Republic has undergone several changes to its territorial administrative structure (Box 4.1). As of 2022, the country has a two-tier subnational system, that was established in 2003, with 6 254 municipalities (obce) and 14 regions (kraje – 13 regions and the City of Prague). At the regional level, the regional assembly (zastupitelstvo kraje) is each region’s elected deliberative body. The regional assembly approves the region’s budget and grants to municipalities (for amounts over CZK 200,000) and can also submit draft legislation to the national chamber of deputies. The regional committee (rada kraje) represents the region’s executive body and is composed of the president (hejtman), vice-presidents and other members elected by and from within the regional assembly for four years. It is assisted by a regional authority led by a director. At the local level, the municipal council (zastupitelstvo obce) is the municipality’s deliberative assembly and is composed of members elected by direct universal suffrage for a four-year term. The members of the municipal council elect (from within the municipal council) the members of the municipal committee (rada obce), which is the executive body of the municipality. The mayor (starosta in smaller municipalities and primátor in statutory cities), who is the head of the municipal committee, is also elected by the municipal council from among its members for a four-year mandate.

The capital City of Prague has a unique dual status as both a region and a municipality. Prague has 57 self‑governing city districts (boroughs) with their own elected local authority and council. In addition, since 2003 (Decree No. 346/2020), Prague is divided into 22 administrative districts. The central Prague municipal government level decides, on the basis of the generally binding Decree No. 55/2000 Coll., which responsibilities are decentralised to boroughs. For example, Prague municipality owns real estate but decentralises the management of certain properties, such as public housing, to boroughs. Urban planning, on the other hand, is done at the central municipal level (OECD, 2018[1]). The board of the capital City of Prague is the executive body for independent or autonomous competences (see below).

There are different categories of municipalities, dependant on their size. In 2021, the municipal level comprised 6 258 municipalities of several categories, 604 cities/towns (mĕsto), 26 statutory cities (statutarni mĕsto) and 223 market towns (mĕstys). If a municipality reaches the threshold of at least 3 000 inhabitants, it can apply for the status of a city, which is approved and determined by the chairman of the Chamber of Deputies of the Parliament of the Czech Republic following the government’s statement (Ministry of the Interior of the Czech Republic, 2018[2]). There are specific criteria for a municipality to be designated as a city. For example, it must have a concentrated urban area in the centre, and a greater part of the municipality must be equipped with public water sewage systems, among others. Still, there are around 200 cities with less than 3 000 inhabitants, as historically, before the 2001 resolution, the criteria for being designated as a city were simpler (Ministry of the Interior of the Czech Republic, 2018[2]). Statutory cities have a special status granted by Act No. 128/2000, allowing them to define their own charter and internal organisation. In particular, they are free to establish districts at the sub-municipal level with their own mayor, council and assembly. It is worth noting that, independently from the category, cities/towns, statutory cities and market towns exercise the same range of autonomous competences (see below).

Box 4.1. From a centralised regulation towards a decentralised territorial organisation in the Czech Republic

The Czech Republic has a long tradition of self-government, dating back to the old administrative feudal system (Plaček et al., 2020[3]). Before the change of the Czech political regime in 1989, the country had a three-tier centralised system of planning and organisation, with regions, districts and municipalities. After the Velvet Revolution in 1989, a series of discussions led to a shift away from the three-tier centralised system, introducing changes to the number of units; their names, powers, relations with the central authorities; and how to structure regional competencies.

The first wave of administrative reforms was mainly focused on creating self-government. In 1990, the Constitution recognised the right to self-government of the local communities and defined municipalities as the basic structure of the new local self-government (Constitutional Law No. 294/1990). Some state powers were slowly delegated to municipalities and the first municipal elections were held in 1990.

Law No. 369/1990 Coll., on Municipal Administration from 1 January 1991 (currently the Law on Municipalities 128/2000 and the Law on the Capital Prague 131/2000) established self-governing municipalities, with the same administrative boundaries as the previous local administrative units. The law provided them with a high level of independence. Within the limits set by the law, municipalities have their own budgets and assets and independently manage them. Law No. 369/1990 did not specify any constraints or limits for establishing a new municipality (e.g. minimum number of inhabitants, size of the territory, etc.). As a result, between 1990 and 1993, the number of municipalities increased by 50% compared to before the Revolution.

In the 2000s, another important wave of reforms took place with the creation of self-governed regions. While the 14 self-governing regions were created by law in 1997, the de facto establishment of autonomous regions only occurred in 2000, with the adoption of other laws governing the position of regional governments. Regions were established and recognised as higher territorial self‑governing units in part to take over responsibility for European Union (EU) policy implementation. To complete these regionalisation and decentralisation processes, a reform, effective since January 2003, replaced district offices by municipalities with extended competences (see below), which took over most of their functions. The old districts still exist as territorial units and remain as seats of some of the offices, especially courts, police and archives. The Act on Territorial Division of the State, passed in 2020 and effective since 2021, aims to simplify the system of state territorial administration by completing the transition from the system of districts to the delegation of functions at the municipal level (OECD-UCLG, 2022[4]).

Since 2015, a process of recentralisation has been taking place to overcome the high levels of fragmentation. Some municipal responsibilities have been transferred from small municipalities to larger ones (to overcome municipal fragmentation) as well as to the central government in the framework of the social reform.

The allocation of responsibilities to local governments is complex, with asymmetric delegated competencies among three types of municipalities. The Czech public administration operates as a combined or mixed model of public administration. This means that the state administration is exercised not only by the state, but also by territorial self-governing units – the municipalities and regions. Thus, municipalities and regions exercise both their own or autonomous competencies (self-government) as well as competencies delegated by the central level (state) – the delegated powers. While the autonomous competencies are the same for all municipalities, and municipalities enjoy a high degree of autonomy for executing them, depending on their size and capacity, the delegated powers transferred to them by law by the central level differ, as set by Article 105 of the Constitution. There are three categories of municipalities, which vary according to the extent of delegated competences. At the upper level is a network of 205 municipalities with “extended powers” that fulfil several administrative functions delegated by the central government on behalf of smaller surrounding municipalities (e.g. civil registers, issuance of identity cards and driving licences; co-ordination of the provision of social services). At the intermediate level, 388 municipalities (including 205 municipalities with “extended powers”) with an “authorised municipal authority” perform delegated functions, but on a smaller scale (e.g. building authority, registry office, social assistance, administration of war graves, specific agenda on environment and agriculture). At the lower level, municipalities have basic delegated powers (e.g. elections, population records, water management). Smaller municipalities can also delegate additional functions to the municipalities with “extended powers” or municipalities with designated municipal authority by public law contracts if they do not want or cannot provide them due to a lack of capacity (OECD-UCLG, 2022[4]).

This complex system results in some overlaps in the allocation of responsibilities and calls for strong co‑ordination among levels of government (Table 4.2). This is the case, for example, in waste management, where the national level prepares legislation and national plans, regions have their own regional plans, and municipalities implement them. Indeed, municipalities have only a small range of purely local competencies established by law, such as property management, the establishment of nurseries and primary schools, or sidewalk cleaning. Since most responsibilities are shared, it is crucial to establish vertical co-ordination mechanisms to manage those joint responsibilities (OECD, 2019[6]) (see below). However, given the high number of local self-governments, this vertical co-ordination represents a significant challenge for the country. This is why the central public administration tends to only work with the largest grouping of municipalities (Type III, 205 municipalities) when organising and monitoring the provision of delegated powers.

While the system appears complex, the asymmetry has allowed adapting to the very different local realities and facilitated the proximity between citizens and the public administration. The Czech public administration and citizens have gradually learnt to navigate within it. The asymmetry has allowed responding to the specific characteristics of small units, which have very different realities. This, in turn, has enabled the Czech administration, via local governments, proximity to citizens, who have a personal and direct relationship with mayors and elected representatives. This proximity between the public administration and citizens might play a role in the high trust gap between local/regional and national authorities: in the Czech Republic, while trust in national government only reaches 30%, trust in regional and local public authorities is 57%, according to the Eurobarometer (European Commission, 2022[7]).

Table 4.1. Different types of municipalities in the Czech Republic and their own and delegated competencies

|

Type I: Municipalities with basic delegated powers (6 258) |

Type II: Municipalities with authorised municipal authority (338) |

Type III: Municipalities with extended powers (205) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

|

Autonomous powers |

Management of municipal property and issuance of generally binding decrees Territorial and regulatory plan of the municipality Establishing/regulating local fees Creating and managing nursery and primary education, basic art education |

||

|

Delegated powers |

|

Type I + Type II competencies plus: |

Type I + Type II competencies plus:

|

1. Some of the municipalities with basic delegated powers have this responsibility.

2. Currently going through reforms to move the authority away from the lower level municipalities to become a competency of the municipalities with extended powers.

3. Reforms to expand the number of municipalities with authorised municipal authority.

Source: Author’s elaboration based on OECD (2020[8]).

Table 4.2. Distribution of power between different levels of government in the Czech Republic

|

Legislation |

Regulation |

Funding |

Provision |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Defence |

|

|

|

|

|

External affairs |

||||

|

Internal affairs |

||||

|

Justice |

||||

|

Finance/tax |

||||

|

Economic affairs |

||||

|

Environmental protection |

|

|

|

|

|

Public utilities |

|

|

|

|

|

Social welfare |

|

|

|

|

|

Health |

|

|

|

|

|

Education |

|

|

|

|

|

Science and research |

|

|

Source: Authors’ elaboration based on: https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/251c368a-960c-11e8-8bc1-01aa75ed71a1/language-en.

Regional governments also have autonomous and delegated competences. Regional governments were established by Constitutional Law in 1997 (Act 347/1997) but acquired actual competences in 2000 by Regional Act No. 129/2000, which transferred a series of responsibilities to the new entities. The act entered into force in 2003, after creating the conditions for the regions to function effectively. Regions are responsible for several functions related to the development of their own territory; for example, they approve planning and zoning documents and are responsible for regional economic development and environmental protection. They are also responsible for regional transport. They can establish measures to develop regional tourism. In some instances, regions and municipalities bear responsibilities for the same policy areas; however, their competencies are divided between the funding of programmes and overarching policy in the case of regions, and the delivery of services in the case of municipalities. For example, regions fund sports activities, but municipalities deliver them (OECD, 2017[5]).

Ensuring the successful implementation of multi-level governance reforms

The Czech Republic has made important efforts to enhance the efficiency of the public administration system. The current public governance reform agenda, known as the Public Administration Reform (PAR) Strategy: Client-oriented Public Administration 2030 (Government Resolution No. 562/2020), is a step in the same direction, by enhancing the efficiency of the public administration system (see Chapter 2 for more details on the PAR). One of the strategy’s key objectives is to improve the accessibility and quality of public services. For this, it considers that only municipalities with sufficient personnel and expertise should exercise delegated powers. To achieve this objective, the strategy contemplates the definition of a new structure of delegated powers by transferring some of the competencies of delegated powers to the Type II municipalities, at the same time, the number of Type II municipalities will increase. With this reform, the Czech public administration aims to ensure sufficient and more efficient service delivery and reduce the administrative burdens of the smallest municipalities. Still, it is important to mention that efforts to decentralise or recentralise responsibilities are dependent on the government of the day.

Box 4.2. The Czech Client-Oriented Public Administration 2030 strategy

The Client-Oriented Public Administration 2030 strategy is the current reform framework in the Czech Republic. It aims to reform the Czech public administration through its vision statement, “in 2030, the public administration will be as client-oriented as possible and will thus contribute to further increase the quality of life of the citizens and the growth of the prosperity of the Czech Republic”. The strategy looks to improve how local public authorities manage public administration and how it is accessed and perceived by the Czech population. The reform strategy has five main goals: 1) accessible and quality public services; 2) efficient system of public administration; 3) effective public institutions; 4) qualified human resources; 5) informed and engaged citizens.

Accessible and quality public services

Under this goal, the Czech Republic looks to improve the availability of public services online and in line with the Digital Czech Republic Strategy. Czech authorities are also looking to reform the current system of municipal delegated powers by placing more municipalities under the Type II list of competences. It aims to improve the overall efficiency of the public administration in the Czech Republic

Efficient system of public administration

This objective looks to make the public administration much more efficient by introducing a new Competency Law. There is also an expectation to remove the various “duplications” or overlaps of competences that exist in the state administration. To improve efficiency, the reform aims to improve horizontal co-operation between its municipalities and between the bodies of the central state administration. The management of public funds is also expected to be improved and the Czech environment for innovation and the development of artificial intelligence enhanced.

Effective public institutions

Under this goal, the Czech Republic will create analytical teams to support evidence-informed decision-making in the public administration. There will also be stronger awareness of sustainable development for civil servants and in the state subsidy policies. To increase the efficiency of public institutions, more emphasis will be placed on implementing effective strategic management and systemic approaches to quality management.

Qualified human resources

This objective is to improve the human capital of elected representatives and officials at the subnational level. To attain a minimum level of expertise in the municipal and regional civil service, the goal is to improve and modernise civil service education in the country by introducing modern tools for educating the civil service. Within the new training programme, the Special Professional Competence exam would be simplified and focused on the professional activities of officials of territorial self-governing units. The control of the training process would also be strengthened while maintaining state supervision.

Informed and engaged citizens

The strategy highlights the decreasing interest in political participation, which is evidenced by voter turnout and political party membership. To combat this dynamic, the Czech strategy looks to boost citizen awareness of the functions of the public administration through enhanced communication methods. The central government is also looking to improve the Czech population’s awareness of the public administration’s functions to improve the perception of the public administration.

Source: Ministry of the Interior of the Czech Republic (2022[9]).

Building consensus and buy-in from different stakeholders is crucial to implement the reforms successfully. The Czech Republic has a history of strong centralisation – before the Velvet Revolution, power was concentrated at the central level. The decentralisation efforts of the last years are thus viewed as a step forward in ensuring proximity with citizens and for policy implementation that responds better to local needs. As is the case in several OECD countries, recentralising some responsibilities is generally met with pushback from municipal associations and representatives. Indeed, multi-level governance reform processes often stall, fail and may be cancelled, postponed or even reversed. They may not go according to plan, and may be only partly implemented, adjusted or even circumvented during the implementation phase, without producing instant results or the expected outcomes. This is why it is crucial to accompany multi-level governance reforms with the appropriate consultations, negotiations and communication efforts to gain support from local actors and civil society (Box 4.3).

Box 4.3. Key elements to ensure successful multi-level governance reforms

Multi-level governance reforms are particularly sensitive and difficult to conduct. These reforms are complex, as they involve several layers of government and refer to reshaping vertical and horizontal interactions between the central government and subnational governments, and also within subnational governments. They concern elected politicians and civil servants from central and subnational levels, as well as various other stakeholders, who sometimes have conflicting interests. In addition, gaining public support is often a challenge. There is either a lack of social demand from citizens or a lack of interest or, when they do express interest, public resistance is still often observed. Reforms tend to be perceived as threats to the existing social order and a risk of loss compared to previous situations, as witnessed by the failure of institutional and territorial reforms (e.g. municipal mergers, regional reforms and decentralisation).

Reshaping the multi-level system of government takes a long time and may need to be adapted. To generate the expected benefits, additional and complementary reforms are often needed to correct for potential deviations and improve multi-level governance mechanisms. Moreover, this is a never-ending process: the challenge of multi-level reforms is not merely to adapt to a new, stable and definitive situation, but to enable public administration at all levels of government to adapt continually to a permanently evolving environment.

OECD countries have adopted a diverse set of strategic levers to enable the successful implementation of multi-level governance reforms. Some of these levers are:

Pilot programmes, experiments and place-based approaches can demonstrate the effectiveness of reforms and pave the way for change on a larger scale.

Development of a multi-level co-operation culture and practice, wide-reaching consultations and negotiations at a preliminary stage and during the whole reform process to overcome opposition from local governments. Beyond organising consultations, multi-level governance reforms can be facilitated by associating local governments with the reform design and implementation, through negotiations with local associations and/or ad hoc commissions, at a preliminary stage and during the whole process. Other tools can be mobilised to “compensate losers” and offer trade-offs, such as temporary transition funds or mechanisms in the case of fiscal reforms, fiscal incentives, provisional guarantees or political compensation. Associations of subnational governments are essential to public administration reform processes, as these intermediation bodies regroup information and provide stable negotiating partners for the government, hence helping to reduce substantial information asymmetries and high transaction costs.

Ensuring good communication practices, incentives, compensation and training activities to mobilise and generate acceptance from central and local civil servants. As decentralisation reforms affect central government structures at ministerial and self-governing units’ levels, they can be perceived as a threat (loss of power and jobs) and there may be resistance. Difficulties can also arise from local civil servants, hence generating opposition to the reform. This dimension is key and should be addressed with appropriate responses.

Establishing expert committees to reach greater political adhesion across party boundaries. This may be especially crucial to keep the momentum for reform going despite changes in government. Parliaments may have an essential role to play in this respect to reconcile different points of view and reach a consensus between different stakeholders. Ad hoc parliamentary committees to consult, prepare and monitor the progress of reforms can be key success factors. Such approaches can also include consultation through permanent multi-level co-ordination commissions or forums or the reliance on ad hoc expert advisory committees.

Providing expertise, guidelines, technical support and prefiguring tools to local governments and stakeholders in the context of the reform can help to achieve its objectives. In contrast, a lack of guidance from the central government has been identified as a problem in several countries.

Sources: OECD (2017[10]; 2017[11]).

Enhancing inter-municipal co-operation to foster efficiency in the regional and local public administration

A highly fragmented territorial organisation affects public services and investment efficiency

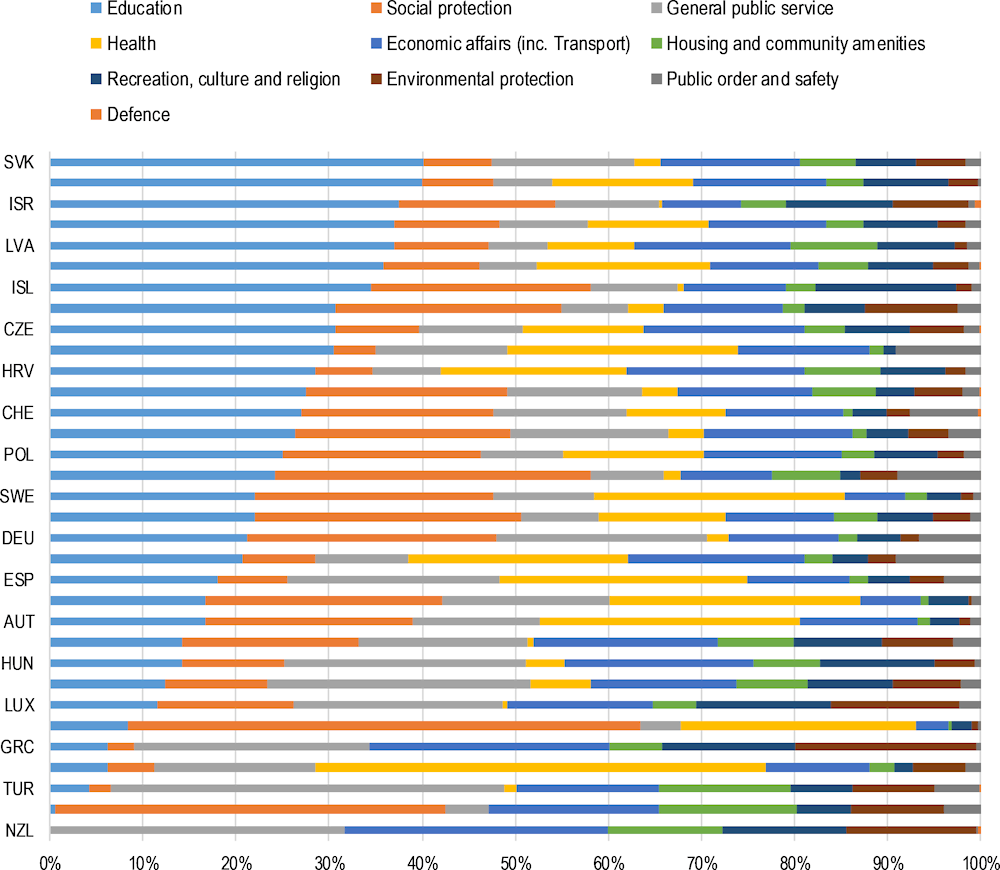

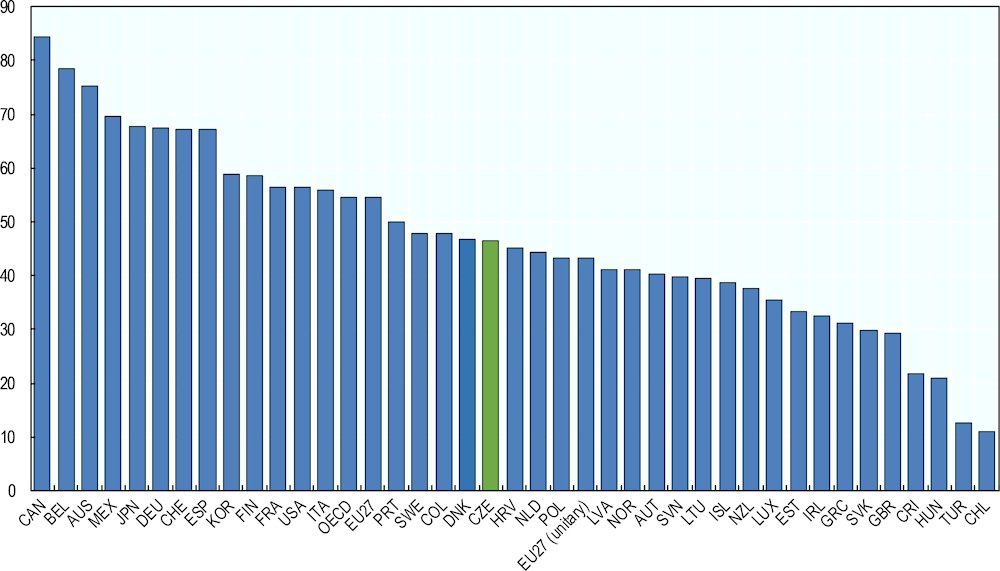

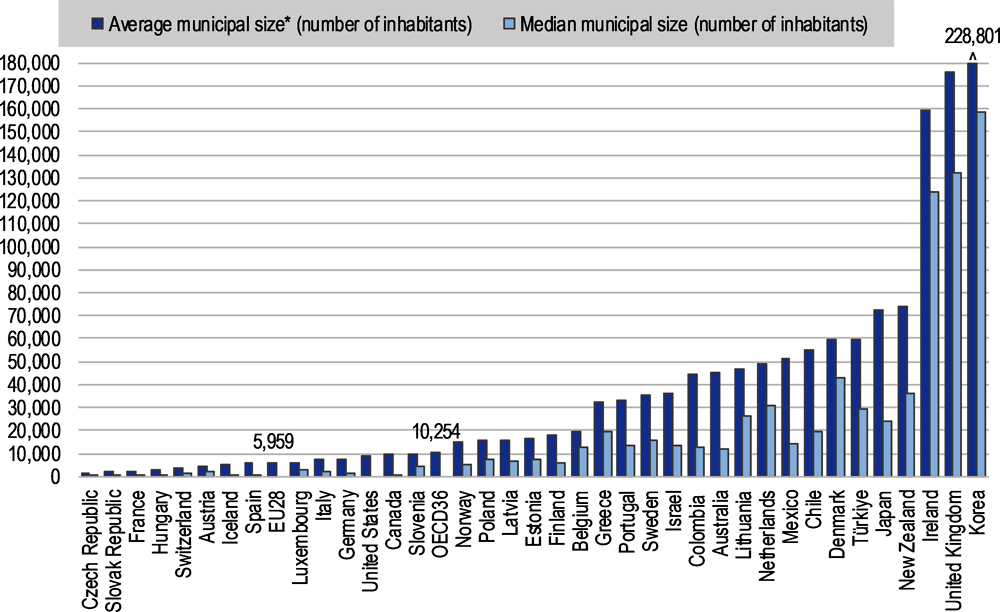

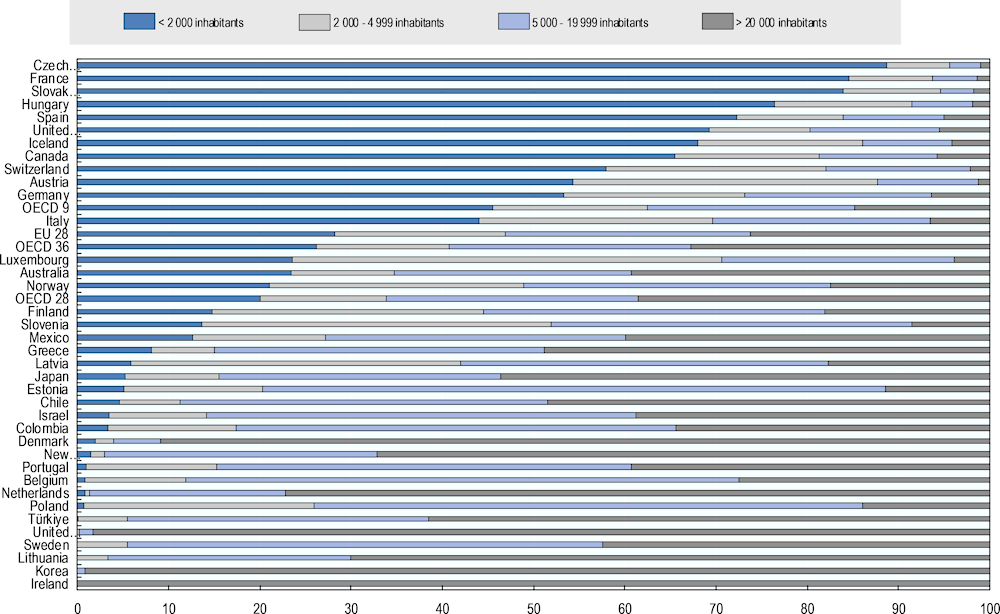

The Czech Republic’s administrative organisation is highly fragmented, with a large number of very small municipalities in terms of area and population. This is due to a law passed in the early 1990s that enabled municipalities to split. In 2020, the average municipal size was the smallest among OECD countries (1 710 inhabitants per municipality on average), well below the OECD average of 10 250 and the EU average of 5 960. While the median size of Czech municipalities is 442 inhabitants, 95.7% of municipalities had fewer than 5 000 inhabitants and 88.6% had fewer than 2 000 inhabitants in 2021. The average municipal area is also the lowest in the OECD: on average, Czech municipalities have an area of 13 km2 compared to 234 km2 on average across the OECD. In the 1990s, and contrary to many OECD countries where mergers have been the rule, municipal fragmentation in the Czech Republic sharply increased – from 4 100 municipalities in 1990 to 6 230 in 1994. In 2000, the rising fragmentation ended with the 2000 Act on Municipalities, which introduced a requirement of having at least 1 000 inhabitants to create a new municipality and includes an option for voluntary municipal mergers, but without any concrete incentive for municipalities to do so. To minimise the effects of municipal fragmentation, the 2000 Act on Municipalities also promotes inter-municipal co-operation through public contracts for performing certain functions and voluntary municipal associations.

Figure 4.1. Average and median municipal sizes in the OECD and European Union, 2020

Note: Average calculations are based on population data as of 2019. Calculations do not comprise Indian Reserves and unorganised territories for Canada, Indian reservations areas for United States and French Guyana for France. For Türkiye, average and median municipal sizes exclude metropolitan municipalities in order to avoid double counting.

Source: OECD (2021[12]).

Czech regions are also small by international standards. The average size of Czech regions is 2.5 smaller than the average size of the EU28 NUTS 2 regions in terms of inhabitants and 4 times smaller in terms of area (Ministry of the Interior of the Czech Republic, 2018[2]). Only 3 of the 14 regions are large enough to be qualified as NUTS 2 regions for EU regional funding purposes (Prague, Central Bohemian and Moravian-Silesian region). The remaining 11 regions are NUTS 3 regions which, for statistical purposes, are joined to form 5 additional NUTS 2 regions (OECD, 2020[8]). It is for this reason that the Czech Republic has created “association of regions” at the NUTS 2 level, which are purely statistical units. The creation of cohesion regions has added some complexity to the functions of public administration systems and policymaking (OECD, 2020[8]).

The administrative fragmentation resulting in many small municipalities affects the cost efficiency of public service delivery. Due to the strong administrative fragmentation, most Czech municipalities are too small to ensure a cost-effective provision of public services (OECD, 2018[1]). Indeed, as has been highlighted by previous OECD work, international evidence suggests a U-shaped relationship between the costs of providing services and the size of municipalities (OECD, 2020[8]). In Spain, for example, per capita total expenditure has been estimated to be 20% higher in municipalities with 1 000 inhabitants compared to those with 5 000 inhabitants; in Switzerland, costs have been found to be higher and service quality lower in municipalities with less than 500 residents (OECD, 2020[8]). In addition, in the Czech Republic, many of these small municipalities are remote and sparsely populated, increasing even more the cost of public service provision (OECD, 2017[13]). The costs of providing services in places with smaller and more dispersed populations are higher due to lower economies of scale and scope, higher transportation costs, and potential financial incentives for service professionals (OECD, 2021[14]). In addition, the population tends to be older in rural areas compared to cities, requiring different and potentially more expensive public services, as has been further revealed during the COVID-19 pandemic. This is set to worsen over time as remote and rural areas face a number of megatrends, including depopulation and an ageing population, that will shape the availability and quality of public services (OECD, 2021[14]).

Figure 4.2. Municipalities by population class size, % of municipalities, 2019-2020*

Notes: Previous years may have been used for some countries (based on last available census)

For the United States: size-classes are slightly different: less than 2 499 inhabitants, 2 500 to 4 999, 5 000 to 24 999, 25 000 or more

For Türkiye metropolitan municipalities are not included to avoid double counting.

1. OECD 28 refers to the average of unitary countries

2. OECD 9 refers to the average of federal or quasi-federal countries

Source: OECD (2021[12]).

Box 4.4. The COVID-19 pandemic has revolutionised service provision

The COVID-19 pandemic has had deep and indirect impacts on the provision of services in OECD countries and elsewhere. The pandemic was infamous for its effects on the increasing mortality rates due to high death counts, as well as disproportionate effects on rural populations. Disrupting the global economy, the pandemic is also likely to have drastic effects on the availability of public resources for social spending in the next years. The pandemic also forced 1.6 billion students out of school across 190 countries and affected financially distressed persons and their ability to receive medical care. This dynamic opened the door for the digitalisation of public services such as education and healthcare. Although the digitalisation of medicine and distance learning education filled the gaps in public service provision, it also highlighted inequalities between rural and urban populations as well as between income levels and broadband access. Amidst the COVID-19 pandemic, telemedicine filled a gap in service provision, proving that the digitalisation of services is an important aspect for service provision, whether during a crisis or not.

Source: OECD (2021[14]).

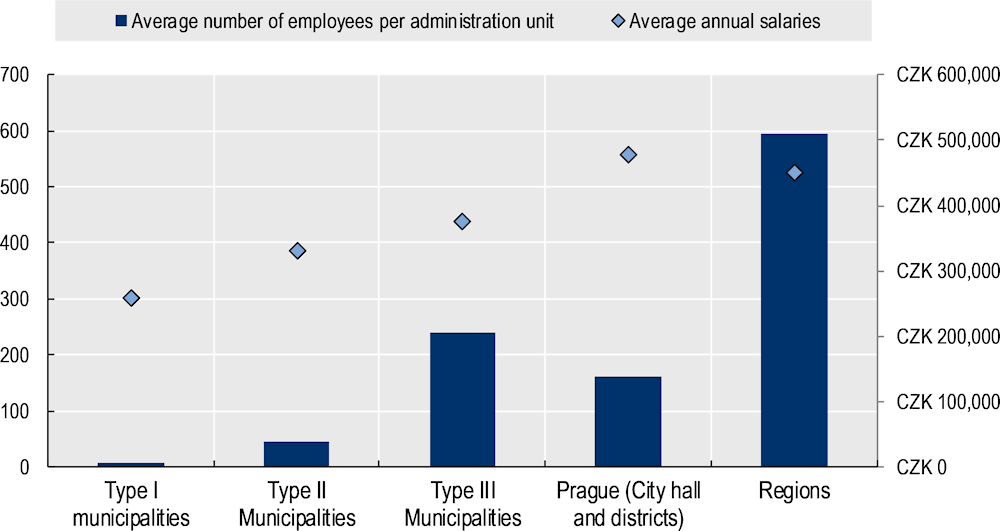

The small size of municipalities also brings challenges due to low capacity. As has been highlighted by previous OECD work and reaffirmed for this assessment, subnational governments in the Czech Republic face an acute gap in adequate skills and administrative capacity. This is particularly true at the local level where, in addition to the skill gaps, they confront difficulties attracting talent (see below).

In this context, local governments would greatly benefit from a rigorous estimation of the cost and quality of public service provision across the country. The Czech Republic lacks an accurate indicators system for assessing the cost and quality of public service delivery, making it difficult to assess the impact of administrative fragmentation on service effectiveness. Some OECD countries such as Australia, Denmark, Italy and Norway compile and publish such indicators (Mizell, 2008[15]). The most well-known system is the KOSTRA system in Norway, which has provided municipalities with a tool for internal planning, budgeting and benchmarking. It has also helped the central government assess if municipalities comply with national standards and regulations (OECD, 2020[8]). In Italy, the OpenCivitas portal provides a large number of detailed data on the performance of local governments (municipalities, provinces and regions) based on actual expenditures and public services provided (OECD, 2020[8]). Chile has adopted a complementary approach, by setting minimum standards for municipal services. Setting minimum standards for service provision at the local level could be a complementary tool for the Czech Republic to encourage municipalities to co-operate in order to attain the minimum and common set of services to which all citizens should have access regardless of where they live (Box 4.5).

Box 4.5. Improving services at the local level: Developing indicators and minimum standards

The KOSTRA system in Norway

The KOSTRA system (Municipal State Reporting derived from the name KOmmune-STat-RApportering) is the information-reporting database for municipalities and counties in Norway. The system started in 1995 to provide a platform for municipal and county data to improve the organisation of planning and management and the realisation of national objectives (Statistics Norway, 2022[16]). In 2001, reporting to the KOSTRA system became mandatory for Norwegian municipalities and counties (Government of Norway, 2019[17]). The KOSTRA system can publish input and output indicators on local public services and finances, and provide online publication of municipal priorities, productivity and needs. The database integrates information from local government accounts and service and population statistics. It includes indicators on production, service coverage, needs, quality and efficiency. The information in the KOSTRA database is also easily accessible to public stakeholders for data analysis and independent research. The KOSTRA system is also used by local governments to compare practices, thereby promoting “bench-learning”. The KOSTRA system is regulated under the Local Government Act, which stipulates the obligation for municipalities and counties to report to the state through the KOSTRA system (Government of Norway, 2019[17]).

At the central level, the KOSTRA system has rationalised data collection and processing, contributing to uniform standards, thereby enhancing comparability across municipalities and services sectors. Additionally, the database has also served as a tool to ensure that municipalities comply with national standards and regulations and facilitated a common assessment of the local economic situation, which is used as the basis of a parliamentary discussion on the transfer of resources to municipalities. For municipalities, the KOSTRA system effectively minimised the administrative burden associated with reporting and acted as a tool for planning, budgeting and communication. The KOSTRA system, having the local government budgeting information, has permitted municipal governments to compare how money is spent in other municipalities and provides a comparison on a variety of indicators for benchmarking.

Minimum standards for municipal services in Chile

Chile’s framework for Quality Management Programme for Municipal Services (Programa Gestión de Calidad de los Servicios Municipales) has been in place for a long time. In 2006, the Certification System of the Quality of Municipal Services (Sistema de Acreditación de la Calidad de Servicios Municipales) was adopted by almost 100 municipalities with 2 management models: 1) the Management Model of Municipal Service Quality that defined three “management levels” through a scoring system; and 2) the Model for the Progressive Improvement of Municipal Management, a simplified version of the first model targeted to municipalities with intermediate or low “management levels”. The system was structured around a set of procedures and methods to support, guide and encourage municipalities to undertake continuous performance improvements.

In 2015, the Chilean government started revising the Certification System, moving towards a System for Strengthening and Measuring the Quality of Municipal Services to create a structure that better meets municipalities’ needs and requirements. The new system focuses particularly on the definition of guaranteed minimum standards to reduce territorial disparities (servicios municipales garantizados, SEMUG). At first, the SEMUG comprised seven municipal services, “the first generation of guaranteed minimum services”, that represented either a high impact for the community or high costs or income for the municipality. These minimum standards have been defined as a basic level of provision in terms of quantity and quality, which has been conceived to be guaranteed by all municipalities in the country – a common set of services to which all citizens should have access regardless of where they live. The 7 selected services included 22 standards and 47 indicators. To define the baseline values for each indicator, the Chilean government worked on a pilot implementation programme with 60 municipalities.

Sources: (Statistics Norway, 2022[16]); (Government of Norway, 2019[17]); OECD (2017[10]; 2012[18]): Mizell (2008[15]).

Inter-municipal co-operation in the Czech Republic is fundamental for investments and service provision at the right scale

Czech municipalities increasingly co-operate for investments and service delivery to counterbalance high administrative fragmentation. Inter-municipal co-operation in the Czech Republic is becoming increasingly common thanks to a vast legislative framework that enables formal and voluntary co-operation among neighbouring municipalities, in particular for autonomous competences (Table 4.3). Voluntary associations of municipalities (VAMs) are the basic form of inter-municipal cooperation (Bakoš et al., 2021[19]; Sedmihradská, 2018[20]). The number of VAMs has been growing steadily since 1990, with significant growth around 2000 due to the adoption of the Law on Municipalities (128/2000) that introduced public-law forms of inter-municipal cooperation and restricted the use of some private-law forms (Sedmihradská, 2018[20]). In 2022, there were 702 VAMs registered in the country, but some of them do not perform any activities. Still, as most of the existing VAMs are single purpose associations and bring only a few members, there is some overlap in the functions carried out by each association, as there aren’t any overarching legislative rules and recommendations in place. A new draft amendment to Act No. 128/2000 Coll. is however under discussion. This amendment creates a new form of VAM, larger than the existing ones: the Community of Municipalities. Such Community of Municipalities should ideally be join the majority of municipalities with “extended powers” (Type III) from the same administrative district. The objective is to strengthen inter-municipal cooperation at a larger scale, that of “micro-region”, to ensure coordination of public services (e.g. social services), joint delivery of administrative activities and territorial strategic development, including strategic and spatial planning. While the draft law establishes a minimum number of members1, it envisages only voluntary membership at this stage.

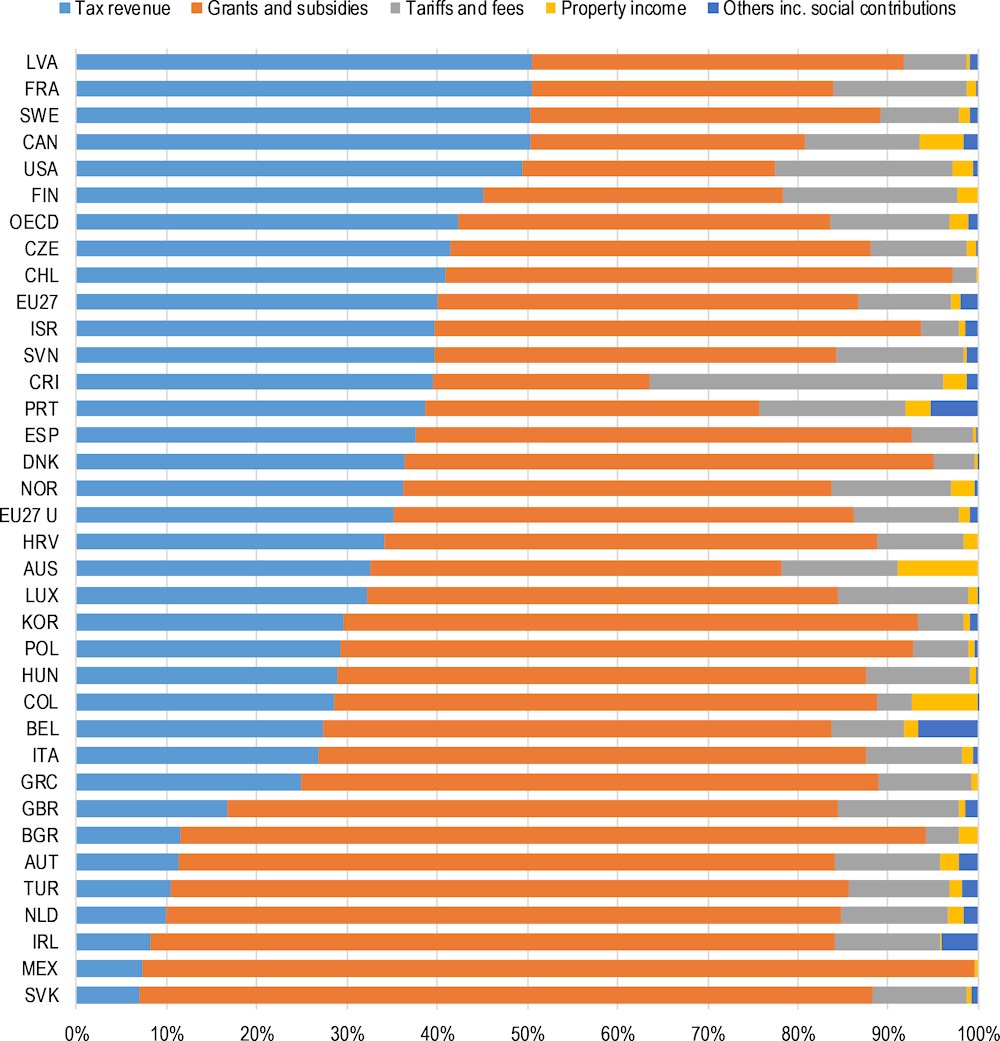

While in some cases, inter-municipal co-operation is for planning and investment purposes, the majority of co-operation focuses on public service provision. In some cases, VAMs can be multi-purpose, covering several functions, mostly to help with the strategic development of its members (OECD, 2020[8]). However, as highlighted by several stakeholders and the Ministry of the Interior, a majority of VAMs are single‑purpose and may focus on a one-time investment project or the ongoing provision of services. Indeed, local representatives most often refer to inter-municipal co-operation for waste management, water and sewerage systems, sports facilities, social care, and home care services, among others. Indeed, across the country, VAMs are mainly established to carry out autonomous competences such as education, cleaning, infrastructure, municipal property management, among others. Multipurpose VAMs have often been considered to be good examples for further promoting this type of co-operation, especially by the Ministry of the Interior. However, as with other VAMs, their set-up does not guarantee stability. VAMs often importantly rely on external, temporary sources of financing, such as from the state budget or EU funds rather than funding provided by member municipalities or own revenues from service provision (OECD, 2020[8]). They also receive funds from their members, but mayors are reluctant to raise membership fees to ensure adequate and stable financing (OECD, 2020[8]).

Table 4.3. Different types of formal inter-municipal co-operation in the Czech Republic

|

Inter-municipal co‑operation structures |

Regulatory/funding frameworks |

Key characteristics |

|---|---|---|

|

Voluntary association of municipalities (VAM) |

Law on Municipalities (128/2000 Coll.) regulates their formation and activity Law on Budgetary Rules of Local Governments (250/2000 Coll.) |

The Law on Municipalities 128/2000 outlines the right to and regulation for co-operation between municipalities. It lays out the appropriate services the VAMs might serve in the country as well as their required makeup. The Law on Budgetary Rules of Local Governments 250/2000 regulates the management of VAMs and local governments. It lays out the budgetary guidelines by which VAMs and subnational governments must abide. A VAM can be founded by two or more municipalities based on a contract approved by the municipal councils of all participating municipalities. VAMS are financed through member contributions, non-tax revenues resulting from their operations and external resources (grants). In the Czech Republic, most VAMs are used for service provision in waste management and sewer and water management (Sedmihradská, 2018[20]). |

|

Joint registered companies: joint stock companies, limited companies |

Act No. 89/2012 Coll., Civil Code Act No. 90/2012 Coll., on commercial companies and cooperatives (Commercial Corporations Act) |

The possibility of using contractual cooperation and setting up joint non-profit institutions and enterprises. |

|

European groupings of territorial cooperation (EGTC) |

European Council Regulation 1082/2006 |

EC Regulation 1082/2006 sets out the legal regulatory framework for the creation and purpose of EGTCs. The regulation establishes EGTCs as legal personalities in the European Union and defines the requirements for their makeup. |

|

Act on Regional Development 154/2009 |

The Act on Regional Development 154/2009 regulates the creation of EGTCs in the Czech Republic. It gives the Ministry of Regional Development the duty of registering the EGTC in the Czech Republic and outlines the reasons for the annulment of the EGTC. |

|

|

Law on Municipalities (128/2000 Section 55) |

Section 55 of the Law on Municipalities 128/2000 lays out the right for municipalities to engage in cross-border co-operation with municipalities of other countries. |

|

|

INTERREG Europe |

INTERREG Europe is one of the funding frameworks accessible to EGTCs under the European Regional Development Fund of EU Cohesion Policy. The programme funds national and subnational entities for regional development projects. There are many INTERREG organisations based on type: cross-border, transnational, interregional. EGTCs in the Czech Republic have been used for increasing co‑operation and regional attractiveness between border municipalities. Some examples of EGTCs in the Czech Republic are: EGTC NOVUM, Dresden Prag EVTZ, Regionálna rozvjová agentúra Senica. |

Co-operation among municipalities for advocacy purposes has also proven effective in the Czech Republic. In a highly fragmented country, municipalities need to group to facilitate dialogue among levels of government and ensure that local voices and priorities are represented and taken into account when setting priorities. Two main associations of municipalities have a strong history in the Czech Republic: the Association of Local Governments and the Union of Towns and Municipalities (Box 4.6). The Ministry of the Interior, which leads the co-ordination with subnational governments, has made important efforts to communicate with these institutions – efforts that are recognised by local representatives that manifest they are periodically informed by the ministry of planned changes that may affect their territory. The associations of municipalities are also consulted when a decision will have a local impact, even though their priorities are not always taken into account. The communication channels established by the Ministry of the Interior are particularly important for taking small municipalities’ priorities into consideration – as the associations are the only way they can manifest them.

Box 4.6. Association of municipalities for advocacy purposes in the Czech Republic

The Association of Local Governments

The Association of Local Governments of the Czech Republic is a non-governmental organisation that promotes the interests of Czech municipalities and cities. It has been in operation since 2008 and has a membership of over 2 200 municipalities. The association also prides itself on being a “strong partner of the government, parliament and regions in the Czech Republic” while also defending the collective interests of Czech municipalities.

The organisation’s aim is to support municipalities in the development of the rural economy and to advocate for municipalities at the national level. The Municipality 2030 (Obec 2030) agenda is also an initiative that was started by the association in 2021. It aims to assist local governments with their progress on the fronts of decentralised energy and its effects on rural development by advising municipal representatives. The Municipality 2030 agenda provides municipalities with financial/funding advice as well as infrastructural support in areas such as public lighting, the circular economy, electromobility, etc. Additionally, the association partners with private companies, such as Skoda and EKO-KOM, as well as state ministries like the Ministry of the Environment, the Ministry of Culture and the Ministry of Regional Development.

Union of Towns and Municipalities

The Union of Towns and Municipalities is also a non-governmental advocacy organisation made up of Czech municipalities. It unofficially started in 1907 when 210 representatives from 100 Czech towns convened for the First Congress of Czech Towns of the Czech Kingdom in Kolín. The union was formally established in Brno on 16 January 1990, after the Czech Republic officially decentralised and later became a partner of the central government two years later. The union is currently made up of over 2 700 towns and municipal governments, which collectively cover a population of 8 million (approximately 80% of the Czech population). The union also advocates for Czech municipalities and oftentimes acts as an intermediary to streamline the concerns of Czech municipalities to the Czech central administration and the European Union. The union lists its main objectives as promoting the “interests and rights” of its members and the education of members’ representatives, among other things. Like the Association of Local Governments, the union assists municipalities in finding additional funding for its members as well as possible partnerships. The union is also a member of the Council of European Municipalities and Regions and the United Cities and Local Governments, international organisations for subnational governance.

Association of Voluntary Associations of Municipalities of the Czech Republic

The Association was formed on the initiative from below, originally as an association of voluntary associations of municipalities of the Central Bohemia Region. It was subsequently joined by voluntary associations from other regions, and the association established itself nationwide. It brings together multi-agency voluntary associations of municipalities that have in the past been supported by funds from projects co-financed by the EU with a view to developing administrative capacity and strategic planning. Its members have an ambition to become Communities of Municipalities.

Sources: Association of Local Governments (n.d.[21]); Union of Towns and Municipalities of the Czech Republic (n.d.[22]); Sedmihradská (2018[20]).

Stronger inter-municipal co-operation can be an adequate response to fragmentation, given the strong political resistance to municipal mergers. While the Czech administrative fragmentation is a prominent challenge, neither Czech municipalities nor political representatives have made a concerted effort to solve it through municipal merges, neither from top-down nor bottom-up approaches. While very few municipalities have merged (Musilová and Heřmánek, 2015[23]), many remain hesitant about the idea of municipal amalgamation. One of the reasons behind this political resistance might be the recent history of centralisation in the Czech Republic (Bakoš et al., 2021[19]). Indeed, the increase by 50% of the number of municipalities after the Velvet Revolution was, to a certain extent, a response to the previous centralised system. Merging municipalities may be perceived as a setback in that conquest for greater local democracy. This contrasts with the experience of many OECD countries, which over the last 20 years have planned, launched or completed municipal mergers (Box 4.7). Still, as is the case in several countries that have implemented municipal mergers, the strong political resistance comes from local actors who see their political powers rebalanced. In this context, strengthening inter-municipal co‑operation – and encouraging associations in a more concrete and explicit way – might be an intermediary solution to at least partially overcome fragmentation, which remains a key challenge for effective policymaking at the local level.

Local governments, especially smaller, would greatly benefit from long-term and stable inter‑municipal co‑operation across the whole policy cycle. Currently, co-operation between municipalities is mainly done on a project basis, lacking a comprehensive territorial development approach to co‑operation and planning. In general, given the financing structure, co-operation takes place for particular investment projects or the delivery of certain services for which municipalities see an advantage for acting together, as external grants are project-based. This is the case for road construction or waste management services. However, Czech municipalities would strongly benefit from longer term partnerships that would allow them to set common territorial development objectives, to plan and implement projects with a long-term horizon and at the relevant scale. This particularly benefits small municipalities, that should group together for strategic planning purposes (see below). Some VAMs have already adopted this practice; municipalities across the country could further learn and benefit from those experiences. The associations representing municipalities or the Ministry of the Interior could promote peer learning in this regard.

Long-term, stable partnerships should target co-operation at the functional scale to improve the effectiveness of public policies. Focusing on functional areas at the urban scale, but also in rural areas, enhances the understanding of key economic trends that unfold on a spatial scale that is not properly captured by small administrative geographies (OECD, 2020[24]). Indeed, administrative boundaries – especially in a strongly fragmented country like the Czech Republic – do not necessarily capture or reflect the geographic reality of economic activity. In urban and rural areas, investment and services are best planned when seen from the perspective of functional service areas with networked villages, towns and more dispersed areas. Indeed, economic relations and flows of goods and people do not stop at the administrative border, but inherently connect different areas (OECD, 2020[24]). This is in line with the perception of some local actors who highlight the need for a “large geographical area or population” for a VAM to reach its potential (Bakoš et al., 2021[19]). For this to happen, it is crucial to develop data on functional areas that can produce a more accurate picture of actual circumstances than administrative areas (OECD, 2020[24]).

Inter-municipal co-operation would benefit from concrete incentives to establish co-operation arrangements. While the voluntary basis of the Czech inter-municipal co-operation schemes is a way of ensuring that co-operation arrangements more effectively target local needs, transaction costs might be important for some municipalities, especially when the VAMs involve the participation of a large number of small municipalities. Some recent evidence points in this direction, showing that large Czech municipalities do not consider inter-municipal co-operation to be cost-effective (Bakoš et al., 2021[19]). Some evidence from France – a highly fragmented country like the Czech Republic – goes in the same direction (Tricaud, 2021[25]). Establishing financial incentives for municipalities to co-operate, from the planning phase, may help overcome these costs.

Many OECD countries have recently introduced financial incentives to encourage inter-municipal co‑operation. For instance, France offers special grants and a special tax regime in some cases; other countries, like Estonia and Norway, provide additional funds for joint public investments. Slovenia introduced a financial incentive in 2005 to encourage inter-municipal co-operation by reimbursing 50% of staff costs of joint management bodies – which led to a notable rise in the number of such entities. In Galicia, Spain, investment projects that involve several municipalities get priority for regional funds (Mizell and Allain-Dupré, 2013[26]; OECD, 2019[27]) (Box 4.7). Poland is also gradually moving in this direction by providing additional funding for municipalities of the functional area that prepare a joint strategic plan (OECD, 2021[28]). These incentives may also help overcome political costs linked to co-operation and the sustainability of an association or agreement that usually depends on the political will of the mayor or local administration.

Box 4.7. Financial incentives for cross-jurisdictional co-operation

Most of the time, inter-municipal co-operation is promoted on a voluntary basis. Incentives are created to enhance inter-municipal dialogue and networking, information sharing, and sometimes to help create these entities. These incentives can be financial or more practical in nature (consulting and technical assistance, producing guidelines, measures promoting information sharing, such as in Canada, Norway and the United States). Several countries have also implemented new types of contracts and partnership agreements to encourage inter-municipal co-operation.

France has almost 35 000 communes, the basic unit of local governance. Although many are too small to be efficient, France has long resisted mergers. Instead, the national government has encouraged municipal co-operation. In 2022, there were about 1 254 inter-municipal structures with own-source tax revenues to facilitate horizontal co-operation. All communes are involved in them. Each grouping of communes constitutes a “public establishment for inter-municipal co-operation” (EPCI). EPCIs assume limited, specialised and exclusive powers transferred to them by member communes. They are governed by delegates of municipal councils and must be approved by the state to exist legally. To encourage municipalities to form an EPCI, the national government provides a basic grant plus an “inter-municipality grant” to preclude competition on tax rates among participating municipalities. EPCIs draw on budgetary contributions from member communes and/or their own tax revenues.

Inter-municipal co-operation has risen in recent years in Slovenia, particularly on projects that require a large number of users. In 2005, amendments to the Financing of Municipalities Act provided financial incentives for joint municipal administration by offering national co-financing arrangements: 50% of the joint management bodies’ staff costs are reimbursed by the national government to the municipality during the next fiscal period. The result has been an increase in municipal participation in such entities, from 9 joint management bodies in 2005 to 42 today, exploding to 177 municipalities. The most frequently performed tasks are inspection (waste management, roads, space, etc.), municipal warden service, physical planning and internal audit.

At the sub-regional level in Italy, there is a long tradition of horizontal co-operation among municipalities, which takes the form of Unione di Comuni, intermediary institutions grouping adjoining municipalities to reach critical mass, reduce expenditure and improve the provision of public services. A law from April 2014 established new financial incentives for municipal mergers and unions of municipalities. Functions to be carried out in co-operation include all the basic functions of municipalities. All municipalities with up to 5 000 inhabitants are obliged to participate in the associated exercise of fundamental functions.

Source: OECD (2020[29]).

Further resorting to peer learning would also benefit inter-municipal co-operation. Peer learning and the creation of capacities are other crucial processes to further encourage municipalities to co-ordinate across the whole policy cycle. As the economic benefits of inter-municipal co-operation arrangements might not be seen in the short term or by municipalities that have never experienced them, in some cases, municipalities need to be persuaded of the benefits and meaningfulness of inter-municipal co-operation. As is the case in other countries such as Chile or Poland, diffusion and imitation seem to be key elements for the success of inter-municipal co-operation (OECD, 2021[28]).

Some OECD countries have opted to encourage collaboration by providing consulting and technical assistance, promoting information sharing, or providing specific guidelines on how to manage such collaboration. Arrangements to solve capacity issues have been prevalent among the Nordic countries (Denmark, Finland, Norway and Sweden), but they have also been practised in Chile, France, Italy and Spain, among others. Czech municipalities with successful stories can share their experience and encourage other municipalities to enter into such arrangements by showing that, through partnerships, municipalities can achieve more efficient and better results. Regions might play a key role in this task by organising peer learning, offering technical support and acting as political facilitators. The elaboration of a clear toolbox or guidelines on how to deal with the administrative procedures when establishing co‑operative arrangements should accompany this process. Capacity-building processes might particularly focus on strategic planning at the supra-municipal level, either by peer learning or through external experts that can support municipalities in assessing the needs of a group of municipalities (see below).

Identifying and legislating on a specific set of tasks that should be performed by a group of municipalities could be an interesting way forward to ensure more efficient services and investments across the country. Joining inter-municipal associations in the Czech Republic are all on a voluntary basis. Sometimes small local governments only perceive the costs of inter-municipal arrangements (Box 4.7), reducing the incentives to establish VAMs. As has been highlighted by previous OECD analysis, mandating inter-municipal co-operation over a legally defined set of public services, delegated or independent competences can be an effective way of improving the quality and efficiency of service delivery and supporting wider use of inter-municipal co-operation schemes (OECD, 2020[8]). In Italy, for example, some evidence suggests that small municipalities benefit from cost reductions and better public services when participating in mandatory inter-municipal co-operation arrangements (Giacomini, Sancino and Simonetto, 2018[30]). Other countries, such as Finland, France or Germany, are also good examples of how mandatory inter-municipal co-operation has raised the stability of co-operation (Box 4.8). In any case, establishing mandatory and legally established tasks for inter-municipal co‑operation schemes would need to be accompanied by appropriate financing mechanisms to execute those tasks, in particular with specific transfers, funding or financing for municipal associations.

Box 4.8. Mandatory inter-municipal co-operation in OECD countries

PARAS Reform in Finland

Intermunicipal co-operation in Finland has gone through many changes throughout different reform periods. Initially, from 2005 to 2007, the Finnish government decided to move forward with the PARAS reform, which aimed to improve the various functions at the subnational, municipal level. These changes were designed to overcome increasing subnational spending, improve productivity, strengthen municipal and service structures, and boost local service provision. During the reforms, municipalities were left the choice to merge or to join a “co-management area” based on a compulsory threshold. In a bottom-up manner, the central government allowed municipalities to choose how to organise themselves while also incentivising municipal mergers through financial grants from 2008 to 2013. With the Finnish government mandating that all municipalities merge or join a local co-management area, the local governments need to reach a population in either scenario of 20 000 inhabitants for primary healthcare services and 50 000 inhabitants for vocational education and training.

In Finland, inter-municipal co-operation is, in fact, voluntary. However, for vocational education and health services, the government requires municipalities to engage in municipal mergers or to join a co‑management area. The use of compulsory inter-municipal co-operation for some services allows the country to go without an intermediate level of government. With the structural regulation and reforms in Finland through the PARAS framework, the ex post analysis found that the integration of social welfare and healthcare services improved at the national level.

NOTRe Reform in France

Before recent reforms of the French municipal arrangements, the system of inter-municipal co-operation was complex. Like many other countries with high municipal fragmentation, the French government, like others, understood that municipalities preferred inter-municipal co‑operation over municipal mergers. In 2014, the French government passed the NOTRe Law (New Territorial Organisation of the Republic) to overcome the existing fragmentation of its roughly 35 000 municipalities. The government set a set of regulations and reforms to facilitate the inter-municipal co-operation agreements. For instance, it mandated that municipalities that were not part of an intermunicipal co-operation agreement join one considering the additional requirements as a result of the reform. The government set up a minimum population threshold of 15 000 inhabitants for inter-municipal co-operation, up from the previous threshold of 5 000. The law highlighted the delegated mandatory responsibilities of the inter-municipal co-operation, known as communautés de communes (communities of communes). The groupings are obligated to work in the framework of seven responsibilities and must work on three responsibilities from a list of seven. Though France, like Finland, has a voluntary dynamic for inter-municipal co-operation, the state makes membership is mandatory and makes some aspects of service provision compulsory.

Strengthening incentives to encourage municipal mergers may still be a way forward worth debating in the Czech Republic. While municipal mergers have met strong resistance in the country, several stakeholders at all levels still manifest that the high fragmentation puts the efficiency of the public administration at stake. Mergers meet strong resistance not only in the Czech Republic, but in several OECD countries. Still, several OECD countries have opted for municipal mergers. Municipal mergers in OECD countries respond to different objectives, such as reducing the mismatch between obsolete municipal administrative boundaries and socio-economic functional areas, achieving economies of scale and scope in the provision of local public services, or increasing municipal administrative capacity (OECD, 2017[11]). In the Netherlands and Switzerland, municipal mergers have been a gradual process and Nordic countries have implemented successive waves of mergers (e.g. Denmark, Norway, Sweden); in other countries, mergers have been mandatory (e.g. Denmark, Japan, New Zealand). Some countries encouraged mergers by keeping the former municipal administration with a sub-municipal status, like in Ireland, Korea, New Zealand, Portugal, the United Kingdom or in France, with the delegate mayors (OECD, 2020[8]; 2017[11]). Several OECD countries have used incentives to encourage municipal mergers, such as providing financial subsidies, guidance and technical assistance, introducing a special status for larger cities (Box 4.9). The Czech Republic could benefit from these countries’ experiences to more effectively encourage municipal mergers, especially in the current context in which, in many areas, population decline is set to continue (OECD, 2020[8]).

Box 4.9. What incentives are there for municipal mergers?

When problems arise from having a fragmented subnational make-up, countries look to respond to these difficulties by merging municipalities. However, instead of forcing municipal mergers, several countries have provided their subnational governments with financial or institutional incentives to merge. While national laws allow municipal mergers to take place, municipalities may not do so for a variety of reasons. Therefore, one mechanism to increase voluntary amalgamations of municipalities has been through improved incentives from the national government for the subnational bodies.

Financial subsidies

When looking to respond to fragmentation, many countries have offered financial incentives, such as subsidies, for municipalities to merge. In Norway, such incentives took the form of a five-year financial support to help municipalities reorganise services and administration, as well as special aid for smaller municipalities. In Switzerland, funds for consulting, guidance and technical assistance were introduced to prepare the ground for mergers. In France, merging municipalities benefited from lesser cuts in grants than other municipalities.

Mix of different types of incentives

Countries looking to encourage their municipalities to merge often also offer a number of incentives to promote municipal amalgamation. In the Netherlands, municipalities that decided to merge were given guidance with the adoption of the “Policy Framework for Municipal Redivision”. Merging municipalities were assisted by the Dutch provinces in the merger process and also received an adjusted and expended merger grant to compensate the newly merged municipalities for the “friction costs”. In Estonia, the government planned to fund consultancy and expertise costs to help municipalities prepare for the merger process. It was planned that the merger grant be double for voluntary mergers, with its end date in January 2017, and included a bonus if the size of the merged municipality exceeded 11 000 inhabitants. In Italy, Law 56/2014 encourages municipal mergers through state and regional financial incentives. The Stability Law 2015 also introduced additional incentives for municipal amalgamations by excluding merged municipalities from the limitations set for hiring personnel. In Finland, the PARAS reform (see Box 4.8) offered financial and organisational support as well as consultation tools. The state also promised that subnational staff in the merging municipality would not be subject to lay-offs for at least five years after the merger took place.

Special status for larger cities

An additional incentive for municipal mergers is by granting larger cities a special status after the merger. In Japan, the central government introduced a third tier of special city status (known as core cities) to promote municipal mergers. It did this in the hope that municipalities would amalgamate, reaching the status, in order to gain new responsibilities under this tier. This status concerned cities of more than 300 000 inhabitants which met a few other requirements. There is some evidence that this strategy may have been successful in Japan.

Creating sub-municipal structures

Another incentive for municipal mergers is allowing the former municipal administration to be introduced as a sub-municipal structure (i.e. local deconcentrated units). The sub-municipal structures are generally given legal status under the municipality and have a deliberative assembly, a delegated executive body (mayor, council) elected by the population, an independent budget, etc., even if they depend on the municipalities. This structure of sub-municipal organisation maintains local accountability despite a comparatively large municipal size in terms of population. The representation of the local stakeholders is also increased through this sub-municipal structure, as it keeps the local identity of the previous administration and protects historical legacies, traditions and democracies. For example, there are many instances of sub-municipal structures in OECD countries: parish and community councils in the United Kingdom; Eup and Myeon in Korea; freguesias in Portugal; settlements in Slovenia, etc.

Source: OECD (2017[11]).

Recommendations to strengthen inter-municipal co-operation

Develop an indicators’ system that allows assessing the cost and quality of public service delivery at the local level. This would help assess the impact of the administrative fragmentation on service effectiveness and, at the same time, would help ensure a minimum standard for service provision across the country.

Develop data on functional areas (in functional microregions and agglomerations) to be able to establish long-term and stable inter-municipal co‑operation schemes at the functional scale. In urban and rural areas, investment and services are best planned when seen from the perspective of functional service areas with networked villages, towns and more dispersed areas. For this to happen, it is crucial to develop data on functional areas that can produce a more accurate picture of actual circumstances than administrative areas. This will, in turn, facilitate joint strategic planning by a group of municipalities at the functional scale.

Introduce financial incentives, such as special grants or a special tax regime for inter-municipal co‑operation bodies, to encourage inter-municipal co-operation. These incentives may also help overcome political costs linked to co-operation and the sustainability of an association or agreement that usually depends on the political will of the mayor or local administration. These incentives should focus, in particular, on encouraging long-term partnerships that allow these bodies to set common territorial development objectives, planning and implementing projects with a long‑term horizon and at the relevant scale.

Resort to peer-learning activities to encourage inter-municipal co-operation. Municipalities sometimes need to be persuaded about the benefits and meaningfulness of inter-municipal co‑operation. Czech municipalities with successful stories can share their experience and encourage others to enter into such arrangements. A particular focus might be given to peer learning through joint strategic planning by a group of municipalities. Regions might play a key role here by organising peer learning, offering technical support and acting as political facilitators. The associations of municipalities or the Ministry of the Interior can also promote peer learning in this regard. The elaboration of a clear toolbox or guidelines on dealing with the administrative procedures when establishing co-operative arrangements should accompany this process.

Identify a specific set of tasks that could be performed by a group of municipalities. Mandating inter-municipal co-operation over a legally defined set of public services, delegated or independent competences can be an effective way of improving the quality and efficiency of service delivery and support wider use of inter-municipal co-operation schemes. This would need to be accompanied by appropriate financing mechanisms to execute those tasks, in particular with specific transfers, funding or financing for municipal associations.

Debate establishing concrete incentives to encourage municipal mergers. While municipal mergers have met strong resistance in the Czech Republic, they can still be a way forward to bridge efficiency gaps at the local level. For this, a voluntary approach to mergers, with concrete incentives for municipalities, could be a way forward. This would need to be accompanied by the appropriate consultations, negotiations and communication efforts to gain support from local actors and civil society and ensure buy-in.

Enhancing strategic planning at all levels of government to pursue a client‑oriented public administration

Strategic planning helps public administrations at all levels articulate their development vision, objectives and priorities and provides guidance for allocating public resources. In the Czech Republic, ensuring the overall high quality of municipal-level strategic planning can substantially contribute to advancing the Client‑oriented Public Administration 2030 agenda. Good strategic planning could help municipalities deliver public services that target local needs, and strategically prioritise projects that have the most impact on supporting local development, hence optimising the use of public resources. However, despite having a clear planning system in place, several challenges remain in subnational strategic planning. First, the weak cross-sectoral co-ordination at that national level makes it difficult for regions and municipalities to align with national frameworks and reconcile different sectoral interests when planning regional and local development. Second, local and supra-local development strategies are not widely considered or used as an instrument to address local needs and, at the same time, contribute to regional and national development objectives. Third, most Czech municipalities are small and lack planning capacity, which has a direct impact on the quality of the local and supra-local strategic plans. It is unrealistic for the central government to provide support to over 6 000 municipalities. This thus requires seeking an optimised and more efficient solution to enhance local/supra strategic planning capacity. This section assesses the strengths and weaknesses of strategic planning in Czech subnational governments and explores potential ways forward, in particular, how to promote joint local planning, exploit the potential of functional urban areas (FUAs) in planning, and build local planning capacity in a more efficient and systematic manner.

Strengthening a place-based approach to regional and local development strategic planning

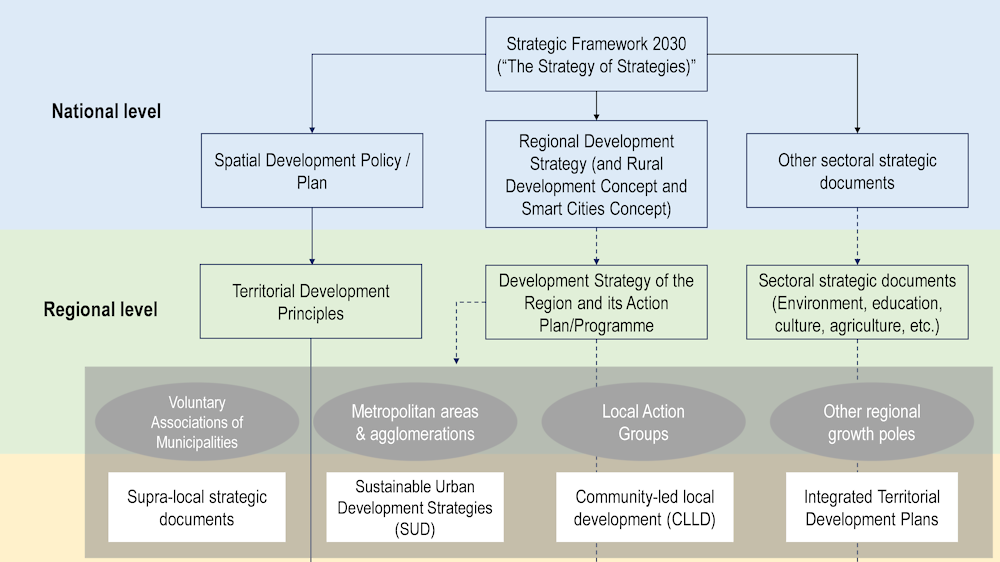

The Czech Republic has a clear multi-level strategic planning system, with the Strategic Framework Czech Republic 2030 being the “strategy of strategies” (Figure 4.3). Regional and local government strategic planning should take into account three key national documents, as listed below, as well as sectoral strategies. While the first two are non-binding for subnational governments, subnational government zoning and land-use plans must comply with the national spatial development policy. All regions and municipalities have land-use plans (mandatory). All regions are also mandated to have a regional development strategy, but municipalities are not obliged to have a municipal development strategy.

The Strategic Framework Czech Republic 2030, originally co-ordinated by the Office of the Government (Prime Minister’s Office) and then by the Ministry of Environment, was approved by a government resolution in 2017.2 It serves as the “strategy of strategies”, setting out the vision for the country by 2030 under six areas: 1) people and society; 2) economic model; 3) resilient ecosystems; 4) municipalities and regions; 5) global development; and 6) good governance. While all areas are relevant to subnational strategic planning, the vision for municipalities and regions3 is the most pertinent to subnational strategic planning.