Risk-focus and risk-proportionality have been increasingly used by governments and regulators when designing and delivering regulation. Risk helps improve the effectiveness and efficiency of regulation. It is crucial in the perspective of achieving public outcomes at every step of the regulatory policy cycle, while minimising burden and unintended side effects of regulation and rules. The use of risk is however unequally spread across countries and regulatory area. Also, many impediments to its utilisation exist, ranging from resistance in institutions to the over-estimation of the effectiveness of “non-risk-based” regulation. The COVID-19 crisis has shown the obstacles that regulation can pose to response needs when it is not in line with a risk-based approach, nor flexible enough. The chapter discusses how risk prioritisation, objective and data-driven risk assessment, use of new technologies to improve data sharing and analysis, and adequate flexibility/agility can dramatically improve regulatory outcomes.

OECD Regulatory Policy Outlook 2021

6. Risk-based regulation

Abstract

Key findings

Designing and delivering regulation in a risk-focused and risk-proportional way is an essential approach to improving efficiency, strengthening effectiveness, and reducing administrative burden.

“Risk” is understood as the combination of the likelihood of harm of any kind, and the potential magnitude and severity of this harm. Risk-based regulation is, crucially, about focusing on outcomes rather than specific rules and process as the goal of regulation.

Adoption of risk-based regulatory approaches is unequally spread across countries and regulatory functions, and is often limited to phases of the regulatory policy cycle, sectors, etc. This is confirmed by data collected from the pilot questions in the iREG survey.

Risk-assessment can serve to prioritise regulatory efforts and tailor the choice and design of regulatory instruments – within and across regulatory domains. It is not only about understanding the level of risk, but the characteristics of each risk so as to design the adequate regulatory response.

Obstacles to uptake of risk-based regulation include resistance in institutions with a “risk-averse” culture, public pressure, path dependency, lack of necessary tools and resources etc. A number of these stem from misconceptions about risk-based regulation, as well as an over-estimation of how effective “non-risk-based” regulation actually is.

As a first (useful) step, risk prioritisation can be done by sector or by type of activity, –but when data for risk analysis and prioritisation is available, a more differentiated, data-driven approach to risk assessment and targeting is essential.

Risk should be assessed in an objective and data-driven way. Significant advances have been made in recent years including through the use of Machine Learning to improve data analysis, and many jurisdictions and services have introduced new risk-based tools and practices, including in the Covid-19 context.

Specifically, the Covid-19 crisis has shown the obstacles that regulation can pose to crisis response when it is not proportionate to risk, or when trade-offs between different risks are not adequately foreseen. It also has shown the importance of allowing and managing regulatory flexibility in emergency situations, and to leverage new technologies.

New technologies can facilitate data sharing and improve analysis, including through the use of a combination of private and public data, but this requires to adequately manage issues of trust and privacy.

Introduction

Risk (and specifically public risk), in addition to its growing use in industry and business, as well as in safety management overall, has over the last couple of decades become increasingly used in a regulatory context (Burgess, 2009[1]). Indeed, in the perspective of trying to improve regulations’ ability to achieve their intended outcomes, and of minimising the burden and unintended side-effects they create, risk is a key tool. It allows to better formulate what it is that a given regulation is trying to address (reducing or managing a risk), to better design the contents and mechanisms of the regulation (based on the causes and characteristics of the risks being addressed), to target enforcement and implementation efforts more efficiently (on the areas, sectors, businesses etc. that pose the highest risk). Thus, risk helps to improve the effectiveness and efficiency regulation at every step of the regulatory policy cycle, including ex post assessment (have the risks been effectively managed?) – and also improves accountability, as it allows to formulate in a clear and often measurable way what the regulation or regulator is supposed to achieve (and what are its limits).

In recent years, overall, much progress has been done in extending risk-based regulation to new countries, sectors, regulatory areas etc. – and in applying innovative practices and tools to improve the understanding and assessment of risk (e.g. data integration and Machine Learning), and use it more consistently from the strategic level to the “regulatory frontline”. This chapter seeks to reflect such progress, and particularly practices that involve novel applications of digital technologies, and incorporation of behavioural insights.

Over time, “risk and regulation” and “risk-based regulation” have become complementary aspects of an increasingly well-established topic, studied by several important academic and practitioners’ networks,1 referenced in numerous pieces of legislation,2 covered by major international publications3 with gradual development over close to 40 years (National Research Council, 1983[2]); (IRGC, 2017[3]) – including previous work by the OECD (OECD, 2010[4]). Still, in spite of risk, risk-focus, risk-proportionality, and risk-management all being referenced in studies and guidance that apply or relate to specific areas of regulation4 (Khwaja, Awasthi and Loeprick, 2011[5]), there is no consolidated guidance on “risk and regulation” as such at the international level. Risk-proportionality is central to international agreements such as the World Trade Organization’s (WTO) Technical Barriers to Trade Agreement (TBT), Sanitary and Phyto-Sanitary Measures Agreement (SPS) and more recent Trade Facilitation Agreement, with relevant clauses5 requiring applied trade-restricting “measures” to be based on risk, and indicating fundamental elements of such an approach, but interpretation and implementation are far from undisputed (Goldstein and Carruth, 2004[6]); (Wagner, 2016[7]); (Russell Graham and Hodges Christopher, 2019[8]); (Russell Graham and Hodges Christopher, 2019[8]). While addressing this “interpretation gap” goes beyond the scope of this chapter, it is important to acknowledge it, as it helps explain some of the implementation difficulties.

Indeed, notwithstanding the considerable progress over time, the remain a significant implementation gap in risk-based regulation – even in some jurisdictions and regulatory areas where apparently binding legislation exists, and/or where official proclamations of being “risk-based” exist. If adequate understanding and assessment of risks, and consistent application of risk-focus and risk-proportionality, are to deliver their expected benefits in regulation, it is essential to more systematically assess the current situation, and spread best practices. The application of “risk assessment, risk management, and risk communication”, point 9 of the OECD 2012 Recommendation on Regulatory Policy and Governance,6 is thus being given increased attention in this edition of the Regulatory Policy Outlook – with results of a series of pilot questions administered along the iREG survey, and an overview of prominent initiatives in the area of risk-based regulation, as well as preliminary findings from research on the application of risk-based methods in regulatory delivery.

Survey results: risk-based regulation is unevenly and incompletely applied

Data from the pilot questions collected with the iREG survey confirms this general finding of uneven and incomplete diffusion and uptake of risk-based approaches – but also of their slowly taking root in the regulatory landscape. Out of the 39 countries (with the EU being included as a country) surveyed and responding overall to the questionnaire, only 32 provided a response on the new “pilot” risk-based regulation questions, potentially indicating some perplexity and/or lack of awareness or interest about the topic. For some countries, the respondents left some questions unanswered or with a negative reply, even though the OECD team independently had information that some practice existed at the sectoral level, suggesting that knowledge about risk-based approaches is insufficiently shared across the government and even within ministries (since respondents queried other ministries, and some evidently did not reply or replied “no” in spite of risk-based approaches existing within their own ministry).

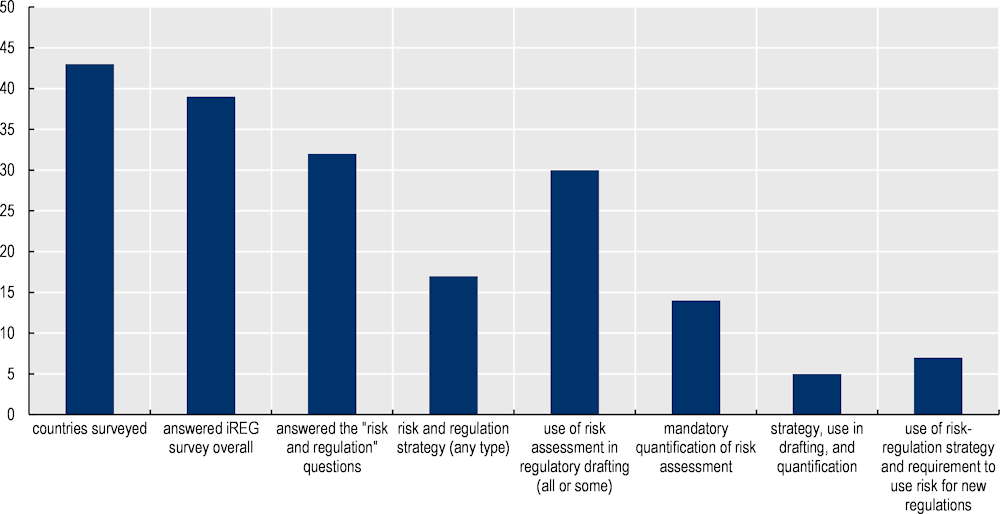

Moreover, the answers suggest that risk-based regulation is often a perspective that is “confined” to some aspects of regulation and regulatory policy, rather than forming a strong framework for the whole of regulatory functions. Indeed, while relatively few countries responded positively on the question of whether they had “a ‘whole-of-government’ strategy on “risk and regulation” (9 out of 39 surveyed) or a “sector‑specific one” (16 positive answers for sector-specific strategy, and 17 in total having either a ‘whole-or-government’ or sector-specific strategy, or both), a significantly larger number indicated that risk assessment was “required when developing regulation” (either for all regulatory areas, or for some only – 28 countries in total having such a requirement for at least some regulations). However, only a subset of these (14 countries) required risk assessment to involve quantitative analysis, meaning that the level of rigour required in the assessment remains often relatively light. Overall, only 5 countries responded “yes”at all 3 key “risk” questions, i.e. whether a “whole-of-government” risk-based regulation exists, whether risk‑assessment is required when developing regulations, and whether this assessment has to involve quantitative analysis (see Figure 6.1).

Figure 6.1. Use of risk and regulation tools according to iREG survey data

Defining and understanding “risk” in a regulatory context

The term “risk” can be confusing, because of its different meanings (both in different contexts, and even within the same context), but also of the different ways in which it can be assessed. “Risk” is often used interchangeably with “hazard” or with “probability (of harm)”. Overall, however, the prevailing consensus when it comes to discussing “public risk” broadly considered, and specifically risk in a regulatory context, is that it is distinct both from “hazard” and from “probability/likelihood”. In this usage, “hazard” is used to refer to the existence of possible harm and its potential severity, but does not convey any information on how likely it is that harm will be materialised. On the other hand, “probability” and “likelihood” refer only to how likely it is that something (e.g. a regulatory violation) happens, without consideration to the severity or scope of this adverse event.

The definition of “risk” as the combination of the likelihood and potential magnitude and severity of harm, as used here, reflects also its use in previous OECD work on the issue, and in many relevant international, scholarly, and national documents and legislation (OECD, 2010[4]); (BRDO, 2012[9]); (Blanc, 2013[10]); (OECD, 2015[11]); (IRGC, 2017[3]). While, inside some countries and institutions, use occasionally diverge (officially or in practice only) from these definitions, consensus is now broad and established for the use of the following definitions in this chapter and elsewhere in this edition of the Regulatory Policy Outlook (Rothstein et al., 2017[12]):

Risk is defined as the combination of the likelihood and potential magnitude and severity of harm. This can also be expressed as the combination of the likelihood and degree of hazard. Thus, risk combines a) probability, b) scope of the harm (number of people affected etc.) and c) degree of harm (type of damage).

Hazard is used as the potential type, magnitude and severity of harm, but without taking into account the likelihood of harm actually happening.

Harm is any form of damage done to people (their life, health, property etc.), the environment (natural and human), or other public interests (e.g. tax fraud harms state revenue). Not all types of harm are of the same nature, and some harm is irreversible (e.g. death), whereas other (e.g. financial) can be corrected once identified.

Unpredictability and uncertainty are distinct from risk and from estimations of probability of harm. They are inherent limitations in the process of risk assessment and thus likewise limitations of risk-based regulation, that should be acknowledged as such. Approaches on how to handle unpredictability and uncertainty are not always explicitly stated or consistent, which is an issue discussed further in this chapter.

Regulations address a number of different potential harms (bodily, environmental, financial etc.), not all of which are of equal seriousness – in particular, reversibility or its absence creates a key difference. Likewise, regulation addresses many hazards – industrial pollution and explosions, food poisoning, building fires and collapses, marketing fraud, tax evasion etc. Again, not all of these are of the same severity, and the likelihood of each of these actually happening varies greatly. Thus, comparing the level of priority of regulating different, but also different economic sectors or establishments, based on the harm caused, is inherently difficult.

Risk can allow to consider allocation of resources at a strategic level (between different domains such as environmental protection, food safety, state revenue, technical safety etc.), even though this is rarely done – as well as to prioritise regulatory interventions in a given domain, between different economic sectors and establishments, which is a much more frequent practice. In this way, risk can function as a kind of common measurement unit, allowing easy conversion and comparison of the relative “value” of different regulatory interventions in terms of lives saved, environmental impact, economic impact etc. – but this is only possible if a common approach to risk assessment across regulatory domains and sectors exists.

Comparing the relative levels of risk, and deciding on the appropriate type and intensity of regulatory response, requires having gone through risk assessment – i.e. estimating the relative level of different risks in terms of combined probability and severity of harm. To allow full comparison across different regulatory domains, not only should there be a unified approach for risk assessment – but also a method to convert different types of harm. While this is theoretically possible (there exist many approaches in law and economics to estimate the economic value of life, health, the environment etc.), it is rarely done in practice with that level of precision. Most often, comparisons of risk levels are done within a given category of harm – e.g. potential losses of life, or potential financial losses. In any case, regardless of the level and scope to which risk is applied, it is an instrument of comparison, and thus prioritisation.

Finally, while risk prioritisation done solely by sector or type of activity can be a useful first step of improvement in situations where risk assessment is starting “from scratch” and with limited or no data to support the exercise, it is not optimal, and insufficient in the longer run. In advanced economies, and where data needed for risk analysis and prioritisation are available to regulatory delivery authorities, a more differentiated approach to risk assessment and targeting can be expected – e.g. so as to be applied to each business entity or object (facility, establishment) individually, based on inherent characteristics and track record.

Why risk matters: the importance of prioritisation, and proportionality

Risk-assessment is thus a useful instrument to prioritise regulatory efforts. While the OECD 2012 Recommendation, and the entire set of regulatory good practices starting from the use of regulatory impact assessment, all emphasise the importance of cost-benefit analysis and selectivity in regulation, risk provides a key instrument to exercise these and also to assess which regulatory instrument to use, given the specific characteristics of each risk. While risk-based prioritisation looks specifically at focusing resources where the highest risk level is, risk-proportionality considers both the level and the characteristics of the risk to determine the most suitable content for regulations (level of standards, degree of prescriptiveness, etc.) and the choice of regulatory instruments (e.g. ex ante permitting, ex post controls, certification, registration, etc.). However, some may contend that regulation should not prioritise and rather (following the requests of a number of different stakeholders) try to regulate all potential hazards, regardless of e.g. likelihood or actual prevalence of harm.

Regulating every hazard may be possible on paper (though it leads to massive inflation of the volume of legislation), but allocating resources to control and implement these regulations can only be done within limits set by state budgets and levels of economic activity. Staff numbers and material resources (transport, testing etc.) needed for inspections conducted by state agencies are limited by budget resources, and competing against many other demands. Even when control over regulatory compliance is delegated to third parties (e.g. through requirements for mandatory third-party certification a.k.a. “conformity assessment”), these have a cost. While such controls are not anymore constrained by state budget size, they impose a direct cost to business operators (which, were possible, will seek to recover it from consumers). Thus, such use of third-party controls is also inherently limited – because of the costs it creates to consumers and businesses, and the negative effect it can have on competitiveness and growth.

An excessive number and range of rules means that it ends up being impossible in practice for most economic operators to know about all of them, and to comply with all. An excessively large scope of regulation thus can be setting itself for failure, and in turn harming the rule of law because it is widely accepted that full compliance is impossible (Baldwin, 1990[13]); (Hampton, 2005[14]); (Anderson, 2009[15]). An excessive number of rules and controls means that regulators may be “submerged” by an excessive amount of data – even with the help of modern data analytics tools and increased computing power, over‑abundance of information makes effective decision making more difficult (Roetzel, 2018[16]).

Crucially, it has been found through repeated studies that levels of control that are perceived as “excessively high” actually end up decreasing compliance (Kirchler, 2006[17]), in addition to the perceived control burden creating disincentives to investment and growth. Instead of responding to increased controls by higher compliance, businesses and citizens can end up “resisting” when they face very high burden, that they perceive as unfair, thus reducing voluntary compliance. Such effect is predicted by “procedural justice” compliance models (Tyler, 2003[18]), which have also shown that people react negatively to processes where they feel disrespected, where they do not think decisions are being taken in a manner that is understandable and ethical. Excessively broad regulation tends to produce such effects because it is often practically impossible to comply fully with it, and it imposes restrictions in situations where actors do not see any meaningful risk or actual harm. As a result, excessively broad regulation can increase the overall level of risk in a jurisdiction because it reduces compliance (Blanc, 2018[19]).

At the outer limit, such an excessively risk-averse regulatory approach can have a negative impact on the aggregate risk level even if it manages to achieve compliance, if the negative economic impact is particularly high, while the direct positive safety impact is low. Indeed, as life expectancy is related to income and to overall GDP levels, the negative aggregate impact on life expectancy may exceed whatever gains are achieved through the regulation (Helsloot, 2012[20]). While this corresponds to extreme cases, they are documented and not fictional. More broadly, these findings indicate that risk-based regulation should not be seen as an approach that trades-off safety for economic growth. While, of course, trade-offs in regulation exist and should be properly acknowledged, for a given chosen level of protection and regulation, risk-based design and enforcement of regulation will, based on available research, achieve better outcomes both in terms of safety and in economic and social terms (Coglianese, 2012[21]).

Taking stock: unequal and often limited implementation

While there are many pieces of legislation that mandate a risk-based approach, and a number of institutions that claim to be using one, the level to which risk-based regulation is effectively implemented is not easy to assess – be it in breadth (across jurisdictions and regulatory functions) or in depth (in terms of how consistent and rigorous the approach is). While some elements of good regulatory practices are, to an extent, directly observable relatively easily (e.g. the existence and level of uptake of a consultation mechanism), it typically requires more expert investigation to assess the degree to which risk is actually and rigorously taken into account in regulatory policy. Looking into the application of risk at the regulatory delivery stage is even more painstaking, for high-level statements of delivery institutions do not necessarily match practices “on the ground”, and the number and variety of institutions involved is considerable. Still, in this edition of the Regulatory Policy Outlook, we attempt a first, preliminary and tentative stock-taking of the current uptake of risk-based regulation, both at the regulatory design and delivery stages.

To this aim, the OECD Secretariat developed pilot questions on “risk and regulation” that were sent to participating countries along with the iREG survey that forms the core basis of this Outlook. While limited in details, and not reflecting an in-depth assessment, they provide a first glimpse of the degree to which different countries acknowledge the importance of risk in the regulatory process, and effectively follow-up at least for some areas of regulation. The survey questions also look into the application of risk assessment and management in the COVID-19 context. In this initial pilot, the survey looks primarily at the breadth of application of risk-based approaches, i.e. at whether they exist and are applied in a given country and, if so, across all of government or only in some sector(s). Looking at the depth of implementation would require additional research work, and the chapter will only provide some snapshots of specific cases.

In addition, to provide an initial view of the “delivery” stage, the Secretariat gathered data on regulatory inspections and enforcement staffing resources in as many OECD member countries as possible, focusing on selected regulatory functions that are particularly prominent in terms both of public perceptions and of actual share resources. These provide a first indication, not only of the importance of the issue including in terms of public expenditure, but of the degree to which regulatory delivery systems differ in the relative weight given to different risks (ratios of resources between different functions vary from country to country), and in the overall importance they give to regulatory enforcement (ratios of enforcement resources to population, businesses, etc.). Again, this is by no means an in-depth research of the variety of regulatory delivery practices in regard to risk, but reflects the broad situation at the strategic level (resource allocation).

Risk and regulation implementation: challenges in data collection, large variations in approaches

As reported in the opening section of this chapter, responses to the iREG survey provide a first glimpse of the uptake of risk-based regulatory approaches, and overall show that less than half of the surveyed countries report having any form of risk and regulatory strategy, while around ¾ of them use risk assessment in some way during regulatory drafting, but only around 1/3 have a requirement to quantify risk in such a process. Such high-level survey data is limited to formal rules and processes, and does not allow to assess implementation of risk-based approaches.

Properly assessing whether risk-based approaches are reflected at different levels and steps of regulatory delivery requires an in-depth investigation of each institution or service, and of the applicable regime for approvals and licensing, inspections and enforcement, etc. While the OECD’s Toolkit for Regulatory Inspections and Enforcement (OECD, 2018[22]) provides a framework for conducting such work, it would require considerable resources to systematically conduct in each country included in this Outlook, even were we to research only selected regulatory areas. Instead, in this section we briefly report the preliminary results from an analysis of available data on regulatory inspections and enforcement resources. Indeed, such work has the first benefit to highlight the importance of the regulatory enforcement function in terms of public administration staff (and thus of budgetary resources). In addition, it allows to compare both between regulatory areas (how different risks are “weighted” against each other at the strategic level of resource allocation), and between countries (how much “intensity” of regulatory enforcement is deemed adequate to deal with a given set of risks).

In spite of data on employment in public administrations being generally public, many countries, institutions or services do not keep specific track of inspectors or staff with inspection powers and functions, or do not have consolidated information on all the institutions involved in a given regulatory field. This is made particularly complex because, in a number of countries, general and/or specialised police and law enforcement bodies also have inspection powers and mandates, though only a part of their staff is actively involved in such activities. Obtaining precise data on this point is sometimes impossible, and doing estimates is not always possible. The complexity of regulatory delivery systems where national/federal, state/regional, local/municipal services all can be simultaneously active in a given field makes the task even more challenging. So does the fact that a given regulatory area can be covered by several services, but also that one given service or institution can be, in some countries, active across more than one regulatory field – in which case estimates of resource allocation between these different mandates is not always available.

The preliminary results of this work (see Table 6.1) show several important points. First, the resources at stake are often considerable, representing quite a significant share of overall state employment and resources, and deserve more systematic attention than has often been the case. Second, the allocation of resources can differ sharply between different regulatory fields, without clarity on whether this reflects a proportional difference in the supervision workload or in the underlying risks. Third, there are sharp variations in “intensity” of supervision in terms of number of inspectors by inhabitant, worker, or enterprise, even between neighbouring and otherwise comparable data. This all shows the importance not only of continuing such research and covering more countries and regulatory fields, as well as obtaining more detailed data, but also for countries to conduct such exercises periodically and systematically to review whether the institutional framework and resources are still fit-for-purpose.

For these reasons, the study has so far been unable to present full data for all OECD members, and even when data is available in some areas, it is not always present for all. To make the research more realistic in scope, the focus has been on food safety, occupational safety and health (OSH), and environmental protection. If we set aside revenue agencies (which have been largely covered through research and OECD literature), these are typically the most important regulatory fields from a “delivery” perspective, be it in terms of number of controls conducted, enterprises regulated, staffing, financial resources – or public perceptions (Blanc, 2012[23]).

As seen below, the allocation of resources can differ sharply between different regulatory fields, without clarity on whether this reflects a proportional difference in the supervision workload or in the underlying risks (e.g. there are from 2.5 to over 20 times more food safety than environmental inspectors, depending on the country). In addition, there are sharp variations in “intensity” of supervision in terms of number of inspectors by inhabitant, worker, or enterprise, even between neighbouring and otherwise comparable countries (Austria has significantly more than Germany, Italy has way more than Germany and France, etc.). This all shows the importance not only of continuing such research and covering more countries and regulatory fields, as well as obtaining more detailed data, but also for countries to conduct such exercises periodically and systematically to review whether the institutional framework and resources are still fit-for-purpose.

Table 6.1. Comparison of inspection staff resources in selected countries and regulatory fields

|

Country |

Food Safety |

OSH |

Env’t |

Total |

Total population |

Total businesses |

Businesses w 10 or more employees |

Inspectors / 100 000 population |

Inspectors / 10 000 businesses |

Inspectors / 10 000 businesses w >10 empl. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Austria |

2 648 |

311 |

120 |

3 079 |

8 901 064 |

410 934 |

41 940 |

34.6 |

74.9 |

734.1 |

|

Finland |

810 |

320 |

753 |

1 883 |

5 525 292 |

302 901 |

21 206 |

34.1 |

62.2 |

888.0 |

|

France |

10 598 |

2 566 |

1 890 |

15 054 |

67 098 824 |

3 981 673 |

160 638 |

22.4 |

37.8 |

937.1 |

|

Germany |

10 338 |

5 218 |

4 374 |

20 063 |

83 166 711 |

2 801 787 |

361 943 |

24.0 |

71.1 |

550.6 |

|

Greece |

1 581 |

629 |

104 |

2 314 |

10 709 739 |

770 002 |

29 741 |

21.6 |

30.1 |

778.1 |

|

Italy |

13 446 |

6 691 |

1 002 |

21 139 |

60 244 639 |

3 834 079 |

176 038 |

35.1 |

55.1 |

1 200.8 |

|

Lithuania |

720 |

231 |

38 |

989 |

2 974 090 |

212 893 |

13 831 |

33.3 |

46.5 |

715.1 |

This situation, combined with other research on specific countries, regulatory areas, etc., suggests that path dependency is important, and that there is a lack of regular, systematic reconsideration of the risks addressed by regulatory delivery structures and resources (Blanc, 2012[23]); (Blanc, 2018[19]). This has contributed to extremely complex, convoluted institutional landscapes (as directly observed when collecting the data, the difficulty of which came precisely from the vast number of institutions with overlapping or mixed functions, frequent unavailability of precise numbers on inspecting staff, etc.), and made resource allocation and expenditure very difficult to track and assess, and mostly unrelated to risk analysis or assessment. From this perspective, the path towards truly risk-based, risk-focused, and risk-proportional regulatory delivery is still a very long one. Nonetheless, important progress has been made, and major initiatives taken in recent years to improve the situation, which are detailed in the following section of this chapter.

Towards risk-based regulation: overcoming obstacles

There are many reasons why the uptake of risk-based regulation principles in policy making and regulatory delivery is far from universal, and implementation often incomplete. This is due to a variety of factors, including resource and capacity constraints (changing regulatory approaches requires expertise and skills), but also public perceptions, and legal systems (Rothstein, Borraz and Huber, 2012[24]); (Rothstein et al., 2017[12]). Public perceptions (both those of the “general public”, of the media, and of decision-makers in the political and economic spheres) can create considerable difficulties for risk-based approaches – both in terms of accepting the idea of “less-than-complete” protection from harms, of assessing and weighing risks, and of accepting proportionality in risk-response. This has been covered extensively in important publications, including on the risk of “knee-jerk” responses to major accidents or emerging hazards (Blanc, 2015[25]); (Balleisen et al., 2017[26]), the psychological determinants of the risk response (Tversky and Kahneman, 1974[27]); (Weyman, 2016[28]); (Burgess, 2019[29]), the variations in risk perception between experts and general population (Fischhoff, Slovic and Lichtenstein, 1982[30]); (Slovic, 1986[31]); (Flynn, Slovic and Mertz, 1993[32]), and the possibility to engage the public to try and make risk perceptions and response more “nuanced” (Helsloot and Groenendaal, 2017[33]).

While engaging with public perceptions and opinion requires a complex and longer-term approach, there are shorter-term issues that governments can try and address to “unlock” the potential benefits of risk-based regulation. In particular, there are useful examples of how governments can work to overcome doubts and resistance from regulatory institutions to risk-based approaches (Box 6.1). Indeed, many institutions may be reluctant to adopt these or even downright hostile, because of a variety of issues: cultural resistance in institutions with a strong “risk-averse” or “safety at any cost” culture, public pressure (or fear of public pressure) making regulators wary of being seen as at risk of “regulatory capture” or “softness”, path dependency and scepticism towards change (sometimes driven by past, disappointing experience), lack of tools and resources. Simply “legislating from above” to promote risk-based regulation, while important, does not usually succeed in achieving practical change if such engagement work with regulators is not done effectively.

Box 6.1. Overcoming “passive resistance” to risk-based inspections: political support and capacity building as crucial drivers

Political support

International experience shows that policy makers’ commitment and support is essential to adopt the legal and institutional changes needed to introduce risk-based regulations. A paramount example is the first phase of the inspections reform in Lithuania (2008-2012), where the Prime Minister at the time, as well as the Ministries of Economy and Justice, provided strong political support. Similar examples on the need to have champions with strong political clout in public administration can be found during the regulatory reform process in Mexico (Comisión Nacional de Reforma Regulatoria, CONAMER, and Agencia de Seguridad, Energía y Ambiente, ASEA) and in Bogotá (Inspección Vigilancia y Control, IVC system), or in the Netherlands with regard to the preparation and adoption of an Internal regulation on the position of inspectorates.

Capacity-building

Experience demonstrates that training enables understanding and adherence to risk-based enforcement systems into inspections’ models with positive outcomes for regulatory delivery. When inspectors adopt a risk-based approach and start providing advice to businesses, the number of non-conformities and incidents decreases. Well-educated and well-trained inspectors are capable of providing useful advice to businesses and ultimately promote compliance and risk-management. Training in, and improvement of, the inspectors’ social competencies is considered as an essential dimension of reform experiences in Australia, Bogotá, the Netherlands and the United Kingdom.

In Bogotá, Colombia, an initiative to promote world-class practices on inspections was launched between 2016 and 2019 in order to boost public confidence in the government. The initiative comprises in particular risk-based inspections planning, the establishment of an IT platform and a capacity-building programme on the following topics: risk-based methods, decent treatment of entrepreneurs, service to citizens, resolution of conflicts, transparency, rights and duties of inspected subjects and technical processes during the conduct of inspection activities.

In the Netherlands, the set-up of the Academy for Supervision aims at introducing a generic training programme for inspectors to strengthen the harmonisation of inspection practices. Risk-based enforcement lays at the core of the training. The philosophy of the approach is to concentrate on understanding of risks and on how to respond to, and handle them.

Source: (World Bank Group, 2021[34]).

In the United Kingdom the 2008 and 2014 Regulators Codes provided the legal basis for the so-called “Primary Authority” scheme (see Box 6.8), which enables businesses to receive advice from inspectorates on how to meet regulation through a single contact authority. The whole approach underlying Primary Authority relies on a high level of professionalism of inspectors, and in particular on them having fully internalised (and being fully proficient) in risk assessment and management. It also requires inspectors to know how to work with businesses in a co-operative way, how to explain and convince – but also how to investigate and spot hidden problems. The foundation of this approach is that inspectors (regulators) need a set of “core skills” (related to risk-based regulation and regulatory delivery) in addition to specific technical skills depending on their domain of activity. These core skills are organised in several groups, including “risk assessment”, “understanding those you regulate”, “planning activities”, “checking compliance”, “supporting compliance”, “responding to non-compliance” and “evaluation”.

Source: OECD Secretariat interviews and research.

Beyond working on perceptions and culture change through engagement with regulators, it is also often indispensable to establish legal foundations for risk-based regulation through enabling legislation. In some cases, existing legislation and constitutional principles may make risk-based approaches difficult or impossible to apply without specifically authorising clauses in law (Rothstein, Borraz and Huber, 2012[24]); (OECD, 2015[11]); (Rothstein et al., 2017[12]). In others, such “horizontal” legislation is used not so much to make risk-proportionality possible as to push it further, introducing directly applicable provisions or mandating regulators to introduce e.g. risk-based targeting or risk-proportional enforcement, etc. Box 6.2 presents some diverse examples of “enabling” legislation for risk-based regulation.

Box 6.2. The risk-based approach in national legislation

Lithuania: Law on Administrative Procedures 2012

An inspection reform towards a risk-based approach was implemented in Lithuania since 2008, which involved changes to adopt strong and legally binding instruments to inspections’ practices. The amendments to the framework law included a risk-based approach to inspections, the means to make it possible, and a balance between inspectors and inspected subjects, by foreseeing their respective rights and duties.

Three key documents were adopted: i) Amendments to the Law on Public administration; ii) Governmental Decree 511 on the inspection reform; iii) Guidelines on various tools of the reform (on development of guidance tools, of performance indicators for inspectorates, etc.). The legal foundations for the reform were set first by a Government Resolution of May 2010 (subsequently amended and strengthened in 2011 and 2012), and by the adoption of a set of amendments to the Law on Public Administration at the end of 2010 – in particular the introduction a new chapter on “Supervision of Activities of Economic Entities”. The provisions of the chapter on supervision are considered as best practice, as they apply to all regulatory areas and emphasise provision of guidance and of assured advice to regulated subjects. One of the innovations of the law is the concept of “supervision”, which comprises provision of consultations, inspection visits, analysis of available information (for risk assessment etc.), and enforcement measures. The amended Law on Public Administration provides for risk assessment and risk focus as foundations for inspections. In addition, the law includes guiding principles such as strict proportionality of inspection and enforcement measures, neutrality and transparency, inspectorates’ obligation to provide advice and assistance to inspected subjects, among others.

Source: (World Bank Group, 2021[34]).

Mexico: National Commission of Regulatory Improvement (Comisión Nacional de Mejora Regulatoria, CONAMER)

Following a constitutional reform establishing that authorities at all levels of government must implement regulatory improvement policies to promote the simplification of formalities, regulations, procedures, and services, among others, the General Law on Regulatory Improvement enabled the transformation of the Mexican Federal Commission on Regulatory Improvement (COFEMER, for its acronym in Spanish) into the National Commission on Regulatory Improvement (CONAMER) as the Regulatory Improvement Authority in 2018. CONAMER’s main mandate is to promote transparency in the process of issuing and implementing regulations, with the ultimate goal of ensuring that regulations create benefits for society that outweigh their costs (OECD, 2018[35]).

In 2019, through the “AC-004-08/2019 Agreement” CONAMER approved an updated regulatory policy for the following years. Regarding inspections, the Agreement foresees that new mechanisms should be implemented to enhance greater co-operation between citizens and authorities. Likewise, it was stated that new tools should be introduced enhance the rationalisation and legality of inspections by means of rigorous risk-based regulatory methodologies, the implementation of better regulation principles and the strengthening of public trust (Source: Acuerdo CONAMER 004-08/2019).

In January 2020, a “New Law for the Promotion of Citizen Trust” was approved to introduce the bases for the development of a risk-based inspection system. According to the law, CONAMER must assure that risk-based planning methods are developed so as to determine the purpose and frequency of inspections based on risk analysis. The law specifically foresees that risk analysis must consider both intrinsic risks and the business ‘trajectory’. CONAMER is working on the development of an information system to support the implementation of the risk-based approach (OECD, 2020[36]).

Slovenia: Inspection Act 2014

In 2002 Slovenia adopted two framework laws, the Civil Servants Act (CSA) and the Inspection Act (IA), accompanied by specific laws regulating each regulatory delivery area. The IA provided common rules to be applied by all inspection bodies and specific principles of the new approach to inspections – in particular proportionality (selecting the measures to be applied against the objectives being pursued), preventive approach, transparency (informing in a timely fashion the public on findings and measures applied during inspections), the possibility to conduct extraordinary inspections to businesses when needed based on risk, and efficiency of inspections. In 2014 a number of amendments to the IA were adopted to enable a more rational (evidence-based, risk-based etc.) inspection system. Based on IA and on the principles introduced through it, specific inspection acts were further adopted to regulate different inspection areas. The Inspection Act provides now for additional/complementary elements needed to strengthen the foundation for a risk-based approach to regulatory delivery: risk identification, efficiency of inspection bodies, risk-based inspection planning, among others.

Source: (World Bank Group, 2021[34])

United Kingdom: 2014 Regulators Code

In Great Britain, the 2014 Regulators Code (which replaced the 2008 Regulators Compliance Code) sets a number of key principles for regulators to follow, including risk-focus and risk-proportionality, the emphasis on providing guidance and advice to promote compliance, the need to always consider the social and economic effects of regulatory decisions and to look for the enforcement decision that will help businesses grow. Among other elements, the 2014 Code (and the 2008 Code before this) also provides the legal basis for the “Primary Authority” scheme, which enables businesses to receive advice from inspectorates on how to meet regulation through a single contact authority (see Box 6.8). The scheme is based on a risk-based approach that allows inspectorates to promote regulatory compliance. The code also included the common inspiration for the way such Authority scheme works and empowers the Office for Product Safety and Standards to manage it.

Source: OECD Secretariat desk research.

Highlights: major initiatives and innovations in risk-based regulation

The uneven and less-than-fully-consistent spread and application of risk-based regulation does not mean, far from it, that there has not been significant progress in recent years, or that there are no worthwhile innovations to report on. In fact, there are many important initiatives that can provide very useful examples of how to apply risk-based approaches concretely and effectively, how to facilitate their use, and how to apply them in innovative ways. Moreover, there also has been a consolidation in knowledge, with increased sharing of experiences, an increased number of good-practice examples, and further development of international guidance (in particular (OECD, 2018[22])). Significant advances in computing power (and decrease in computing costs) have also made the application of risk-based analysis and planning far easier, compared e.g. to a decade ago.

In this section, we thus look successively at improvements in the use of data for risk-based regulation and specifically regulatory delivery, at the use of risk as a guiding principle to make regulation more outcomes-focused, and at the application of risk in the COVID-19 context (including the actual and potential application of digital technologies e.g. for remote surveillance and inspections).

Implementing risk-based regulation through better use of data

The very foundation of risk-based regulation is the reliance on data, because risk should be assessed in an objective, data-driven way, as much as possible. In past years, availability of data has often been issue for more systematic and thorough risk analysis, in particular when it came to applying risk-based planning to regulatory inspections. Indeed, detailed data on entities and establishments under supervision was often not available, or not digitised, or not updated, etc. Different services held parts of the relevant data, and were not communicating. Findings from inspection records were frequently impossible to analyse systematically to update risk assessment methods because they were paper- or text-based, or insufficiently detailed, etc. Digital government developments, progress in computing power and methods, spread of technology and skills, evolution of systems in public administration etc. have led to a situation where these constraints are much reduced, and both “already known” good practices can be taken up more widely, and new, innovative practices can be implemented successfully.

Earlier reviews of international practice had already allowed to define objectives for information systems to enable risk-based inspections and enforcement (OECD, 2014[37]), and to establish desirable key elements for inspections information management systems, as well as essential implementation requirements etc. (Wille, 2013[38]); (OECD, 2015[11]); (Mangalam, 2020[39]). Ideally, such systems should provide updated data needed for risk assessment and planning on facilities, businesses and activities, and allow targeting and prioritising the selection of businesses subject to inspection in line with their risk level. They should enable recording of inspection results in a way that makes further analysis and follow-up easy and automatable. They should also either rely on a single data repository for multiple services, or enable and facilitate data exchanges between them, and offer support for reporting, performance monitoring, etc.

Recently, several jurisdictions have introduced or further developed information systems which address all or several of these requirements, in ways that correspond to the applicable context and constraints. A selection of such systems is presented in Box 6.3.

Box 6.3. Information systems for inspections

United Kingdom: “Find it”

The Health and Safety Executive (HSE) is a regulatory delivery agency which conducts inspections and promote inspections with a risk-based approach and methodology (see Box 6.7). In order to improve its regulatory targeting capability, so as to secure the greatest impact on reducing work-related risk, HSE developed a web application called Find-It, which enables authorities to make better use of data, demonstrate accountability, deploy resources optimally and improve their overall efficiency (Source: Find-It flyer, HSE). Inspectors no longer have to self-select sites – i.e. spending time looking at lots of different data from various sources to identify high-risk premises which they will inspect. A variety of algorithms match: GIS information about the site location, the numerous names used by a business, regulatory and administrative data about a business kept in various databases within and across organisations. The risk for facilities is calculated, whenever needed, based on indicators, such as past enforcement measures, time since last inspection, accident records, etc. Decision-making on targeting is partly centralised by HSE intelligence officers. One such officer provides directions to around 350 inspectors to choose the best options for actions in areas and with facilities posing the highest risk. It also enables choosing when to combine HSE inspections with those of other inspectorates.

Source: (World Bank Group, 2021[34]).

Italy: information systems for regional inspection services

At the core of Campania Region’s reform on food safety inspections lays a risk-based IT System called GISA (Gestione Integrata Servizi e Attività, see http://www.gisacampania.it/). Currently, it supports risk assessment of businesses and locations/facilities for the purposes of inspection planning. It automatically calculates risk levels based on risk models using the results of controls and checklists. Risk levels are periodically reviewed depending on the type of activity and “surveillance” inspections. ‘Surveillance’ means a technical method of examination that focuses of the structural, managerial, and contextual aspects in order to assign a risk level to the business and facility/location. Non-compliances found in inspection visits are also recorded into the System, and used as an additional indicator in “surveillance” inspections when determining risk levels. GISA is used not only by the food safety and veterinary services of the region, but also by the Carabinieri units in charge of sanitary surveillance, providing a first step at data integration. The system is “free to reuse” for all Italian public institutions, and its adoption is considered both by other regions for food safety inspections (Valle d’Aosta and Liguria), but also by both national and regional services for environmental protection.

In the Autonomous Province of Trento, a unified platform to register and plan inspections has been developed over the past 3 years, called the RUCP (Registro Unico Controlli Provinciali, Unified Registry of Provincial Controls). Right now, the RUCP is operational for a couple of services only, but provides early support for “mobile inspections” (pre-defined check-lists used on tablets). At its core is a single database where, eventually, the results of all inspections will be accessible to all services, at least in aggregated form, and help them avoid duplication and increase their “intelligence” on establishments, thus updating and refining their risk analysis. In addition, a module is under development to support risk-based analysis and rating of establishments, and support risk-based planning, which will start being operational in 2021.

Source:; (OECD, 2021, forthcoming[40]).

Netherlands: creating an interface and interconnection between all inspection systems

Inspection View, initiated in 2013 and developed for different sectors, designates a virtual platform in which inspectors can consult information on inspection objects. Such information is available in data systems of other inspectorates they use to conduct inspections and record inspection outcomes, and Inspection View is an integration platform which enable data exchange and horizontal co-ordination between the inspectorates. The leading idea behind the solution is that inspection and enforcement should be carried out from the perspective by government as a whole, and not by individual inspectorates. Inspection View enables national, regional and local inspectors to consult each other’s data on inspection objects, being now used by over 500 inspectors. It is developed as a government-owned platform, with outsourced maintenance and support.

The external information systems are used to support conducting risk assessment, inspection scheduling and collecting inspection outcomes. Than the information from all external sources is presented to the user of Inspection View in an integrated file. Since no data is duplicated, the user always gets the most recent set of data. With Inspection View inspection results can be analyzed for a particular object, or can be exported as a bulk data to be analyzed using some external software (e.g. Excel). Two versions of Inspection View are being developed: a generic version, accessible to all inspectors, and specific versions for inspectors in co-operative networks, with access only for participants in those networks. Until today, three versions of Inspection View have been developed: Companies, Environment and Inland Shipping Inspection View. The Inland Shipping Inspection View has proven to be very successful, as all inspection authorities participate in the System.

Source: World Bank Group (forthcoming 2021), Publication on Integrated Inspections Reforms; https://www.ilent.nl/onderwerpen/toegang-tot-inspectieview/documenten/publicaties/2019/1/31/gebruikershandleiding-inspectieview.https://www.ilent.nl/onderwerpen/toegang-tot-inspectieview/documenten/publicaties/2019/1/31/gebruikershandleiding-inspectieview.

Slovak Republic: The Financial Reliability Index

The Slovak Financial Administration was created in 2012 through the merger of the former Tax Administration and Customs Administration. In 2018, the Administration has started to use a new “Financial Reliability Index” to support risk assessment. The conditions for the functioning of the Index were created in 2018 through an amendment to Act No. 563/2009 Coll. on tax administration. The risk assessment of supervised entities is based on an internal automatic analytical tool. It allows to identify “reliable” tax entities for which the periodicity of tax controls is reduced, and improve targeting of excise tax controls.

Source: research by the OECD Secretariat.

Another way, in which data management and use can be considerably improved by technology, and lead to improved regulation of risk, is the analysis of existing data. While revenue agencies had long started to systematically use data analysis techniques to identify risk indicators and their relative importance, this had until recently been difficult to replicate for non-revenue inspections (Khwaja, Awasthi and Loeprick, 2011[5]). Data was insufficiently digitalised, too complex, or on the contrary too narrow – or historical records were insufficiently long, as new systems had been introduced too recently. In some cases, data systems with historical inspection records existed earlier, but their scope was narrow. Specific staff competences and capacity were also often missing. The rising understanding of risk-based regulation and of the importance of accurate risk-assessment (as opposed to relying on “traditional” assessments of where priorities lay) have opened the way for a more systematic, data-driven approach. In spite of remaining challenges in terms of assessing the “severity” dimension of risk, recent Machine Learning applications are very promising in terms of significantly improving the understanding of which characteristics of businesses and establishments are the best predictors of risk, and thus considerably improve the effectiveness of risk-based targeting (see Box 6.4).

Box 6.4. Machine learning and risk indicators

While defining risk abstractly is relatively straightforward, developing robust methods to predict the level of risk of different businesses or establishments is far more difficult. Until recently, challenges in data availability and methods for analysis meant that defining risk criteria and their relative weights based on “data mining” or similar mathematical approaches was mostly reserved to tax and customs inspections (where the objects of regulation and control are inherently numerical, and computerisation was done earliest and in the most systematic way) – in technical, safety and similar fields, risk identification and weighting was done through a combination of scientific and technical findings, regulators’ experience and “trial-and-error”, but in a much less systematic and precise way.

The spread of information management systems to record inspection results, and thus the increasing availability of detailed historical data, combined with advances in data processing power and analytical tools (e.g. machine learning) now make it increasingly possible. In Italy, the regions of Trento, Lombardy and Campania are currently piloting the use of Machine Learning for risk assessment. Based on historical data analysis, the system can identify which characteristics are the best predictors of risks, which helps make risk-based planning of inspections far more precise and reliable. In Lombardy, the work focuses on occupational safety and health, in Trento the analyses covers labour law inspections, and in Campania food safety controls.

In addition to such work to better assess “operational-level” risk, work at the “strategic level” is also increasingly data-driven. In 2017, Canada’s CFIA launched a review of its risk management model in order to ensure the allocation of resources where it can have the greatest impact on reducing risks. The first challenge of the model is to enable comparison among different kinds of risks, which entails converting different types of risks into comparable data. Based on this, the Agency is able to consider trade-offs among all of them, across different organisational levels This work has entailed considerable efforts to gather and consolidate data from all parts of CFIA’s work.

Along similar lines, the Risk Assessment Directorate of Environment and Climate Change Canada has developed the Threat-Risk Assessment (TRA) model, based on a large review of available data to estimate the probabilities and potential impact of known sources of harms for the environment. Data is gathered from the industry, government partners and, international actors. Outcomes from the strategic risk assessment are used by the Climate Change and Environment of Canada for project planning and allocation of resources. Likewise, it is shared with enforcement officers to inform their work.

Notes: on the experience in tax inspections targeting see (Khwaja, Awasthi and Loeprick, 2011[5]) (OECD, 2004[41]) (OECD, 2009[42])

Source: (OECD, 2021, forthcoming[40]), direct interviews with and presentations from CFIA and Environment and Climate Change Canada.

Beyond the definition of risk indicators and risk assessment algorithms, up-to-date and reasonably comprehensive data on supervised entities is essential to ensure that targeting of regulatory control measures (inspections and enforcement) is really based on risks, and that regulators can react in a timely and effective way when new risks appear or accidents occur. To this aim, it is essential that regulatory agencies have adequate data management tools, and that they share data with each other as much as possible. Data sharing between regulators and other entities (non-regulatory, such as e.g. health-care providers or private certifiers) is likewise important to improve the effectiveness and efficiency of the entire regulatory system. In a number of countries, such improvements in data-sharing are made difficult by privacy regulations, or by the way in which they are interpreted and enforced. Given the importance of the issue in terms both of efficiency and effectiveness, it appears crucial to promote further research and experience sharing on good practices that allow to effectively protect individual privacy, but allow essential information to be shared by regulatory services, particularly about economic entities (and not relating to private persons). Furthermore, much of the information, which is important to improve risk analysis and assessment and might have privacy implications (like, say, health care or accidents data) can be anonymised fully before any analysis, as what matters for studying risk in that case are not the individual cases but the patterns.

New technologies make such data sharing and effective analysis increasingly easy, and some initiatives can be used as particularly valuable examples (see Box 6.5). These can include the use of a centralised database and common system by a number of regulators and possibly by health-care providers too, or tools to exchange information in an automated way between different systems. Sharing information between different regulatory agencies allows them to ensure that data on supervised entities is as up-to-date and comprehensive as possible, and also to avoid duplication of control activities. Information sharing with the healthcare system allows regulatory agencies to better assess the emergence of new risks and evolution of known ones, and thus target their interventions better, both in terms of which establishments they visit, and which industries, products, etc. they focus on. For instance, systematic reporting from health care institutions on accidents due to failures in product safety, or food-borne contaminations, can greatly improve the ability of regulatory agencies to target their activities (and does not need to convey any personal, sensitive data – as what matters for risk assessment are patterns of cases, not individual specifics).

In addition, data sharing agreements e.g. with private certifiers active in areas of interest to regulators (for instance food safety) can likewise allow to have more comprehensive and updated information on sectors with vast numbers of operators (like food). Finally, the use of “non-traditional” data sources such as social media or reviews from e-commerce sites can help assess food safety or product safety risks. Using such sources requires automation to handle vast amounts of data (machine learning), but can be both effective and cost-efficient,7 and provides information that is broader and more timely than regulatory bodies themselves can obtain through traditional methods such as inspections.

Box 6.5. Sharing and using data to better manage risks

A number of Italian regions and institutions have, in recent years, worked on improving data sharing, analysis, and usage, to reduce the burdens and inefficiencies created by duplications and lack of co-ordination between different services, and better support regional economies.

In Lombardy, the Mo.Ri.Ca system for risk monitoring in construction sites uses data emerging from notifications, surveillance and accidents (collected via Impres@BI) and estimates the risk level of a given site on this basis. Risk criteria and weights, previously defined empirically, are now being improved through Machine Learning (cf. Box 6.4). The key strength of the system is that it integrates data from a number of sources, including notifications from the health care system, and considerably improves risk management at a very limited cost.

In Campania, in addition to the existing GISA system to plan and manage all food safety inspections, the region partnered with the University of Naples Parthenope to develop MytiluSE, a system to predict the quality of waters so as to secure safety of mussels produced in the bay of Naples. Rather than expending large resources on ex post controls to find potential contamination, the system works pre-emptively, enabling to know which days the harvesting of mussels would be unsafe. Once fully operational, it can both inform producers and guide inspectors’ work. Developing the system involved investigating the currents of the bay of Naples, mapping contamination sources, and developing a reliable predictive model, but it is potentially completely transformative for regulatory delivery. It was also adapted to predict air pollution by fumes, which can affect feed for bovine herds. The predictive approach for mussels is not only better for the economy and public service efficiency, but it also avoids health hazards far more effectively, because microbiological testing and sampling takes time, and results can come too late (leading to potential contaminations from other products harvested the same day).

Source: Montella R, Riccio A, di Luccio D, Mellone G, de Vita, C G (2020), MytiluSE: Modelling mytilus farming System with Enhanced web technologies, Università degli Studi di Napoli Parthenope, Sciences and Technology Dipartiment, commissioned by Campania Region, Unità Operativa Dirigenziale Prevenzione e Sanità Pubblica Veterinaria (presentation) – for other cases: (OECD, 2021, forthcoming[40]).

Outcomes-focused instead of process-focused regulation

Although increasing work is being carried out in institutions, processes and methods that aim to administer, control, and implement regulations so as to better realise risk-based approaches, differences in regulatory delivery styles between one country and another, but also between regulatory delivery agencies within the same country, are still considerable8 (Blanc, 2012[23]); (Hadjigeorgiou et al., 2013[43]); (OECD, 2015[11]). The way their goals are devised – some stressing control of legal compliance and punishment of non-compliance, whereas others focus on risk mitigation or improvement of public welfare – are among the most ubiquitous differences. The latter aim at meeting public outcomes rather than processes and/or formal conformity. Outcome-focused regulation is another aspect of risk-based regulation – because risk is the indicator through which outcomes can be defined and measured, and thus the criterion used to prioritise actions and take decisions, rather than focusing on rigid processes.

While the use of outcome-oriented approaches has gained a growing profile, work is still needed to change what still seems to be the prevailing perception that these approaches are an alternative to traditional command and control schemes, rather than something that should be used in delivering regulations. This is an overly restrictive perspective of what outcome-focused approaches, and regulatory delivery, are about. In fact, approaches, methods, and tools focused on achieving regulatory outcomes are at the core of efforts to make regulatory delivery more effective, and efficient.

In practice focusing on outcomes entails an actual paradigm shift from a traditional conception of regulatory enforcement based on finding and punishing violations towards a understanding of regulatory delivery where the primary and ultimate purpose is the protection of safety, health, the environment, and other key elements of the public good. Implementing this approach relies heavily in promoting meaningful compliance – i.e. compliance that actually helps achieve regulatory goals – including by regularly using behavioral insights. It also requires i.a. effective risk communication and information to regulated subjects, development of, and investment in, methods and tools focused on delivering expected outcome, and adequate measurement of the level of protection of the relevant public welfare good. Regulated subjects should not be expected to know everything about what to do and how, but are to be guided, advised and informed. Finally, focusing on outcomes is inherently connected to having the right performance indicators and metrics – not measuring outputs or sanctions, but tracking the outcomes in terms of improved performance, reduced risks etc. (Blanc, 2018[44]); (Blanc, 2021[45]).

Some regulatory delivery agencies see as one of their main functions to support regulated subjects as risk creators in managing the risks they generate. This involves working in partnership with all stakeholders able to produce sustained change. Inspectors in Britain’s Health and Safety Executive have long relied on an approach where law is the last resort and whereby they seek to engage with regulated businesses and push them towards safer practices through a variety of behavioural tools (i.e. personal relations, advice, comparisons with others, indication of potential risks and costs, hints at possible sanctions etc.) (Hawkins, 2003[46]). Results show better outcomes (in terms e.g. fatal and major accidents) than before the change of approach and/or in other sectors not using this new approach to the same extent.9

A decade ago, Britain’s Health and Safety Executive issued the Enforcement Management Model, a detailed guidance of how inspectors should take enforcement decision based on risk assessment, compliance record of economic operator, specificity of rules etc.10 A number of other inspection and enforcement services in various countries have developed and adopted principles or guidelines regarding their enforcement approach. Guidelines of this sort will be essential, going forward, to enable regulatory systems to cope with complexity and change, and situations “on the ground” that may be increasingly be difficult to fully forecast at rulemaking-stage. In a positive development, some countries are seeking to make such approaches and guidelines more consistently used across regulatory areas (see Box 6.6).11

Box 6.6. Outcomes-focused checklists within the “Rating Audit Control” (RAC) project in Italy

The RAC project in Italy, funded by the European Commission and implemented by the OECD, aims at supporting regional and national governments in improving the business environment and investment climate and the efficiency of the use of public funds through improved regulatory predictability and confidence, and reduced burden on lower-risk activities. To achieve better outcomes in regulatory delivery, inspection methods and practices on the ground are being transformed, consistency of inspections improved, and efforts towards clearer and more understandable regulatory requirements for business operators undertaken.

One key tool to achieve this goal is work on risk-based checklists for inspections, which are being prepared in different regulatory areas so as to ensure development and consistency in methods, and to make a valuable contribution to improving matters in terms of outcomes. New checklists are being adapted to regional realities. They include a risk-based scoring system, and their results are being linked to an update in risk rating. By including the “static” risk of the establishment, its “dynamic” risks (actual risk management, such as the use of HACCP in food safety), and its compliance history (including measures imposed by inspectors because of violations leading to immediate risks), they yield a comprehensive picture of the establishment in terms of actual level of risk, and of most significant elements that need to be addressed to achieve the desired outcomes in terms of regulatory goals.

Source: internal OECD research – (OECD, 2021, forthcoming[40]).

Because the implementation of a more outcomes-, risk-focused approach entails important technical and professional dimensions, many prominent and successful initiatives are made in a specific sector or regulatory agency, rather than in a cross-cutting programme of reform. Some of the most interesting examples are presented below in Box 6.7, and typically include a variety of complementary tools and interventions to make the regulatory delivery work more effective and efficient.

Box 6.7. Sector specific risk based approaches

United Kingdom: Health and Safety

The Health and Safety Executive (HSE) is a non-departmental (i.e. not directly part of the Ministry’s services, but autonomous) public body reporting to the Department for Work and Pensions with the core purpose to reduce work related injuries and ill-health. The HSE collaborates with a range of stakeholders in UK involved in health and safety and share responsibilities for regulatory control with local authorities. The HSE is both a regulator in the rule-setting sense, and a “regulatory delivery” agency, conducting inspections, investigations, developing and providing guidance and advice, and co-operating intensively with the industries it supervises so as to proactively manage and reduce risks. Internationally, the HSE has long been at the forefront of innovation in regulatory delivery methods, in particular in terms of compliance promotion (through guidance, collaboration with industry, long-term engagement etc.), risk-based targeting and risk-proportional enforcement. Risk-based targeting and planning methods are mainly enabled by “Find-it” application, an IT tool developed by HSE to enhance its regulatory delivery task.

Campania Region, Italy: Food safety

Between 2007 and 2010, Campania Region undertook a reform of the food safety inspection system, moving from a regulatory delivery regime mostly focused on deterring non-compliant behaviours to a risk-based system based on the requirements set in the EU Hygiene Package. The reform initiative took place based on a specific regulatory demand, following some major accidents and a breakdown of trust of the private sector and the public (due to insufficient official communication on risks and to the lack of effectiveness of the control activities related to risk management). The underlying systemic problems that prompted the reform initiative were, among others, the lack of a planning system of controls based on risk categorisation.

In order to address these problems, the initiative included a variety of elements supporting risk-based regulatory delivery, i.a. risk-based decision-making (including both risk-based enforcement and inspections planning), inspections processes and procedures, tools (checklists, IT system, etc.), Key Performance Indicators, human resources management, and vertical co-ordination. A main tool towards strengthening a risk-based approach introduced with the reform was the IT System.

As a result, the reform has led to the following: i) classification of economic operators in risk categories and planning of inspection frequency commensurate with the risk level; ii) Improvement of quality and quantity of information provided to the Ministry of Health and the EU, in accordance with applicable rules; iii) Systematic distribution of inspection visits over the territory of the Region; iv) Identification of emerging risks; v) Number of activities performed as defined by relevant objectives; vi) Better human resources management.

Canada and EU Mutual Recognition Agreement on drugs and medicinal products

A Mutual Recognition Agreement (MRA) is a legally binding treaty between the regulatory authorities of the two countries that are part of the agreement. It aims at enhancing international regulatory co-operation and maintaining high standards of product safety and quality, while facilitating the reduction of the regulatory burden for industries.

By the development of MRAs different countries accept the regulatory system of each other as equivalent for a certain type of goods, meaning that products in this category that are cleared for sale in one country will be accepted in the other. This typically applies to goods of a certain level of risk, i.e. for which pre-market approvals (or at least conformity assessment procedures) exist. Pharmaceuticals are one such high-risk area, where MRAs can significantly facilitate reciprocal market access, and thus the development of the sector.

The MRA between Canada and the EU on drugs and medicinal products is built, among other pillars, on the components of the Good Manufacturing Practices (GMP) Compliance Programmes. These components are used to determine the equivalence of the relevant regulatory programmes of both parties. A special chapter is devoted to the “inspection procedures” component, where inspections are grounded on a risk-based approach. This approach ensures that inspections focus on high-priority products in terms of risk posed. Thanks to the use of the risk-based approach and the mutual recognition mechanism, there is no need to duplicate inspections on the same products, and inspections can concentrate on higher priority products. As a result, inspection expenses and resources are reduced, while high standards and high-quality compliance programmes in international co-operation are maintained. This case shows the relevance of risk-based approaches also in a multilateral context and in the perspective of international regulatory co-operation.