This section outlines the key trends in International Regulatory Co‑operation (IRC) across OECD Member countries, building on the relevant 2021 OECD Survey of Regulatory Policy and Governance (iREG) questions and recent developments identified in OECD analytical and country work. It shows a steady increase in the consideration of internationally agreed instruments in domestic rulemaking. Nevertheless, overall progress on IRC is still lagging behind the increasingly needs for cross-border regulatory action. The COVID-19 pandemic and other challenges such as climate change underscored the importance for countries to co-operate rapidly and strengthen their international regulatory co-operation capacities before crisis hit, to be mobilised in time in the face of transboundary emergencies.

OECD Regulatory Policy Outlook 2021

4. Rethinking rulemaking through international regulatory co-operation

Abstract

Key findings

The complex and interconnected policy challenges that countries across the world are facing today, such as those raised by the COVID-19 pandemic and climate change, have increased the urgency for international regulatory co-operation to support domestic rulemaking in areas where cross-border efforts are critical. This need was already present before the crisis and is now starker than ever. The pandemic underscored the importance for countries to co-operate rapidly and strengthen their international regulatory co-operation capacities before crisis hit, to be mobilised in time in the face of transboundary emergencies (OECD, 2020[1]). Still, results from the 2021 iREG show that progress on this front still lags behind emerging needs.

Countries increasingly include international considerations in their rule-making cycle via regulatory policy tools, but the trends suggest a largely “pick-and-choose” approach to IRC. The 2020 iREG survey confirms an upward trend of countries either systematising consideration of international instruments, considering international evidence or accounting for international impacts in the domestic rulemaking process, as illustrated by the OECD Reviews of International Regulatory Co-operation of Mexico and the United Kingdom (OECD, 2018[2]) (OECD, 2020[3])). However, a systematic approach to embedding considerations of the international environment in domestic rulemaking is yet to be fully realised in the majority of OECD countries. The OECD Best Practice Principles on International Regulatory Co-operation (OECD, 2021[4]) support countries in addressing this fragmentation, by recommending a unified and compelling narrative around IRC to promote regulatory quality embodied in a whole-of-government policy and a supporting co-ordination mechanism. However, iREG data confirms that a whole-of-government IRC policy remains an exception among countries, and oversight on IRC activities mostly continues to be shared among several central government bodies.

Innovative technologies today know no borders, whereas regulation remains largely confined within traditional national boundaries. The interconnections resulting from digitalisation and transformative technologies more broadly put increasing pressure on traditional regulatory frameworks, showing the limits of purely unilateral approaches (OECD, 2019[5]). IRC is key to ensure that regulations effectively protect citizens against the risks and harms of these technologies, while at the same time preventing undue innovation costs for business. Better IRC can prevent companies from avoiding compliance and encourage a “race to the top” among governments with better and more effective joint approaches. The OECD Draft Recommendation on Agile Regulatory Governance to Harness Innovation under preparation by the OECD Regulatory Policy Committee will support regulators in adapting their regulatory processes to the interconnected, digitalised and innovation-driven global economy.

Increasing international commitments are being made to use IRC and good regulatory practices (GRPs) to reduce unnecessary barriers to trade, creating an additional impetus to strengthen regulatory quality and coherence. IRC is viewed as an important mechanism to reduce the unnecessary trade costs arising from regulatory divergences among trading partners (OECD, 2017[6]). GRPs and IRC are therefore increasingly leveraged in bilateral, regional and multilateral agreements. The WTO Agreements on the Application of Sanitary and Phytosanitary measures (SPS) and Technical Barriers to Trade (TBT) create a comprehensive transparency framework (OECD/WTO, 2019[7]) that was used extensively at the height of the COVID-19 crisis to improve the predictability of regulatory changes and facilitate international trade (OECD, 2020[1]). There is also a growing number of dedicated chapters in trade agreements setting commitments on GRPs, international regulatory co-operation, or both (Kauffmann and Saffirio, 2021[8]). A corollary to these international commitments is the assessment of trade impact in RIAs at the domestic level (OECD, 2018[2]) (OECD, 2020[3]). Specific methodologies are emerging for estimating the impacts of regulatory drafts on international trade, which support efforts to reduce regulatory divergences. In certain cases, these impact assessments are connected to international notification processes, enabling more effective dialogue and regulatory co-operation.

Countries could further expand their use of IRC to address policy challenges beyond trade. Country-level analysis confirms that knowledge of systematic IRC practices remains relatively low across regulators and policy makers, except in selected policy areas or among trade policy authorities (OECD, 2018[2]) (OECD, 2020[3]). Nevertheless, analytical work confirms that IRC is a critical tool for achieving national and international policy objectives well beyond trade liberalisation. This is particularly applicable to addressing cross-border policy challenges, such as those related to the environment. Long-standing IRC efforts to address transboundary air pollution provide a good example of this (OECD, 2020[9]). Recent OECD research predicts that co-ordinated policy action between China, Korea and Japan would result in the implementation of the best available techniques in the three countries, leading to more significant air quality improvements than purely national approaches and lowering citizens’ exposure to air pollution (Botta et al., 2021[10]). IRC can allow regulators to address challenges at the right level of governance, limit unnecessary frictions and divergences among regulatory frameworks, pool administrative resources, and broaden the evidence base for regulation (OECD, 2013[11]).

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has stressed the need to embed IRC in regulatory frameworks ex ante, to be relied on during transboundary emergencies. IRC is essential for policy makers and regulators to rapidly address together common threats and, in the case of COVID-19, to eradicate the virus across countries. IRC can ensure mutual learning on issues such as vaccine development, support resilience of supply chains and enable the availability of essential goods including key medical products, and facilitate the interoperability of services and cross-border activities such as telecommunications or transportation. Yet the crisis reveals a disconnect between the growing cross-border nature of policy challenges and the traditional national scope of laws and regulations – the key tools of policy making along with taxation and spending. Acting under pressure and facing time constraints, the immediate country reactions have often been unilateral, seeking national and sub-national solutions and even isolationism to protect populations from a threat perceived as largely coming from outside (OECD, 2020[1]).

IRC is anchored in the 2012 OECD Recommendation on Regulatory Policy and Governance, illustrating its importance for regulatory quality and effectiveness (OECD, 2012[12]). OECD work has identified several ways that countries can implement this principle, including the systematic consideration of international instruments in the development of regulation, opening consultation processes to foreign parties, embedding consistency with international standards in ex post evaluation, and establishing a co-ordination mechanism in government to centralise relevant information on IRC. These practices were already monitored in the OECD Regulatory Policy Outlook 2018. This showed that, while increasingly recognised by countries as relevant for regulatory quality, only a few have a cross-governmental vision of IRC and its governance remains highly fragmented. This edition of the Regulatory Policy Outlook examines how these practices have advanced and captures new IRC developments across OECD countries. It also highlights a number of IRC efforts that were instrumental for countries to address policy challenges linked to the COVID-19 pandemic (OECD, 2020[1]).

The OECD Regulatory Policy Committee has recently developed a set of Best Practice Principles on International Regulatory Co-operation to provide guidance for regulators on how to better implement Principle 12 of the Recommendation in support of regulatory quality. The Best Practice Principles are organised around three pillars: i) Establishing an IRC strategy and its governance; ii) Embedding greater IRC considerations in domestic rulemaking; and iii) Engaging in international co-operation at the bilateral, regional and multilateral levels (OECD, 2021[4]). This chapter draws upon new data from iREG to map regulatory requirements and practices against these pillars. Building on the work of the IO Partnership, it also identifies recent efforts to improve the quality and effectiveness of international rule-making activities.

Governance of IRC

International regulatory co-operation (IRC) is multifaceted, implemented via a variety of processes and actors, both nationally and internationally. A whole-of-government strategy to ensure international considerations are systematically embedded within domestic rulemaking procedures by all relevant actors responsible for developing, overseeing or implementing domestic regulations can thus strongly benefit IRC efforts (OECD, 2021[4]).

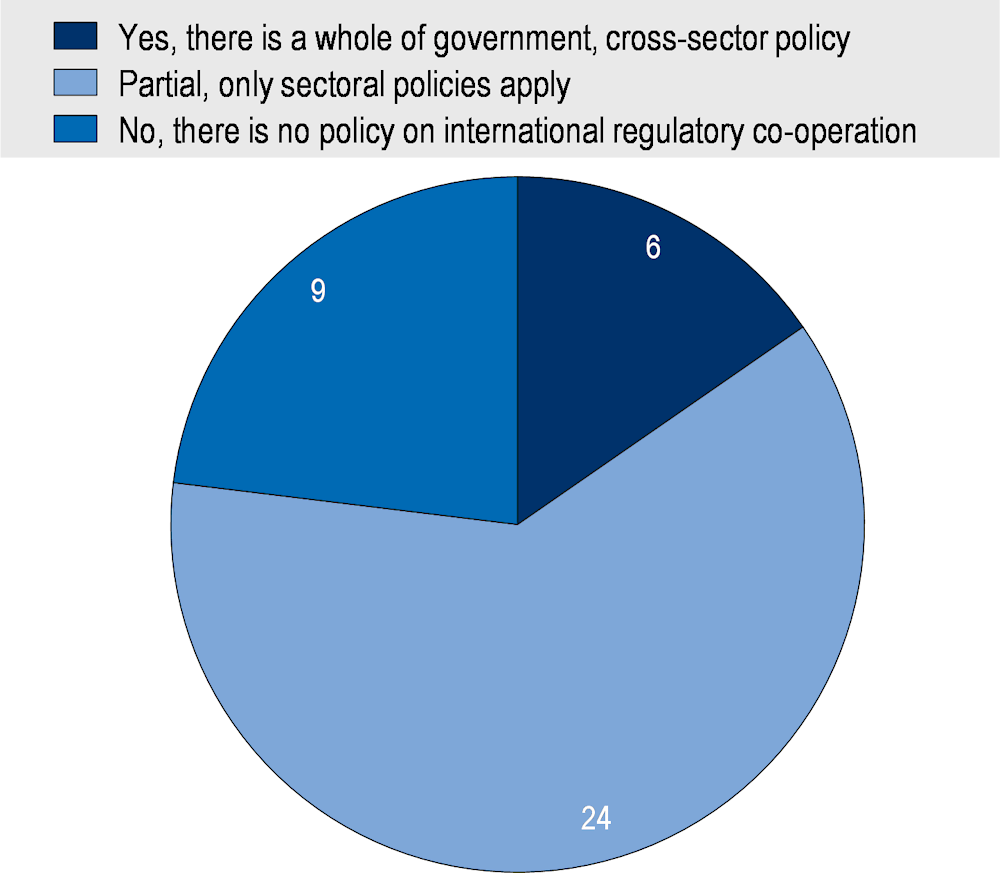

A well-functioning IRC policy can be defined as a systematic, national-level, whole-of-government policy/strategy promoting international regulatory co-operation, whether reflected in a broad strategic document or other instrument (OECD, 2021[4]). Only six respondents have a comprehensive whole-of-government policy and related guidance, despite the recognised importance of such a policy for effective IRC practices. The examples of different IRC policies confirm that these may have a varying scope and legal underpinnings, ranging from statutory obligations to softer approaches (Box 4.1).

In addition, while few countries have a systematic whole of government IRC policy, a significant share of respondents have a “partial” IRC policy, only applying to certain sectors, limited geographically to neighbours or a specific region, or even a specific type of co-operation. The European Union Member countries, in particular, rarely have a whole-of-government policy related to IRC, even though their regional regulatory co-operation is strongly reflected in their national regulatory processes due to their membership of the bloc. The European Union remains the most ambitious regional regulatory co-operation framework involving supra-national regulatory powers. Member countries of the European Union therefore intrinsically have an active regulatory co-operation mechanism built into their regulatory processes by virtue of their membership obligations and of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (OECD, 2018[13]). These policies can be considered as “partial” IRC policies, given their geographical limitation to regional partners (Figure 4.1). The European Commission itself, however, does reference IRC within its “Better Regulation Agenda”. This ensures that IRC is considered when new initiatives and proposals are prepared and when existing legislation is managed and evaluated at the European level.

A few countries have “partial” IRC policies, in that they are only limited to one form of international instrument – typically binding international law or international standards. However, it is important to note that the “partial” scope of such an IRC policy can still be a useful basis to integrate national and international frameworks. For example, in Germany, Article 25 of the German Constitution represents a “partial” legal basis on IRC to the extent that it incorporates certain international instruments, i.e. “the general rules of public international law”, as an integral part of federal law. In addition, the German Constitutional Court has developed a principle of Völkerrechtsfreundlichkeit (friendliness to international law) according to which the German Basic Law “presumes the integration of the state it creates into the international legal order of the community of States”.1 As a result, German Law is to be interpreted as consistently as possible with international law. This illustrates that jurisprudence and legal principles developed by domestic courts can promote IRC in domestic legislation and regulation.

Few countries have developed a new IRC policy in recent years. A notable example of an OECD country undertaking an ambitious process to design and develop such a policy is the United Kingdom, which, as a follow-up to its OECD Review of International Regulatory Co-operation, presented to the UK Parliament a call for evidence to develop a whole-of-government strategy on IRC (BEIS, 2020[14]).

Figure 4.1. Number of jurisdictions with an explicit whole-of-government, published or legal basis on IRC

Note: Data for OECD Countries is based on the 38 OECD member countries and the European Union.

Source: Indicators of Regulatory Policy and Governance Survey 2020.

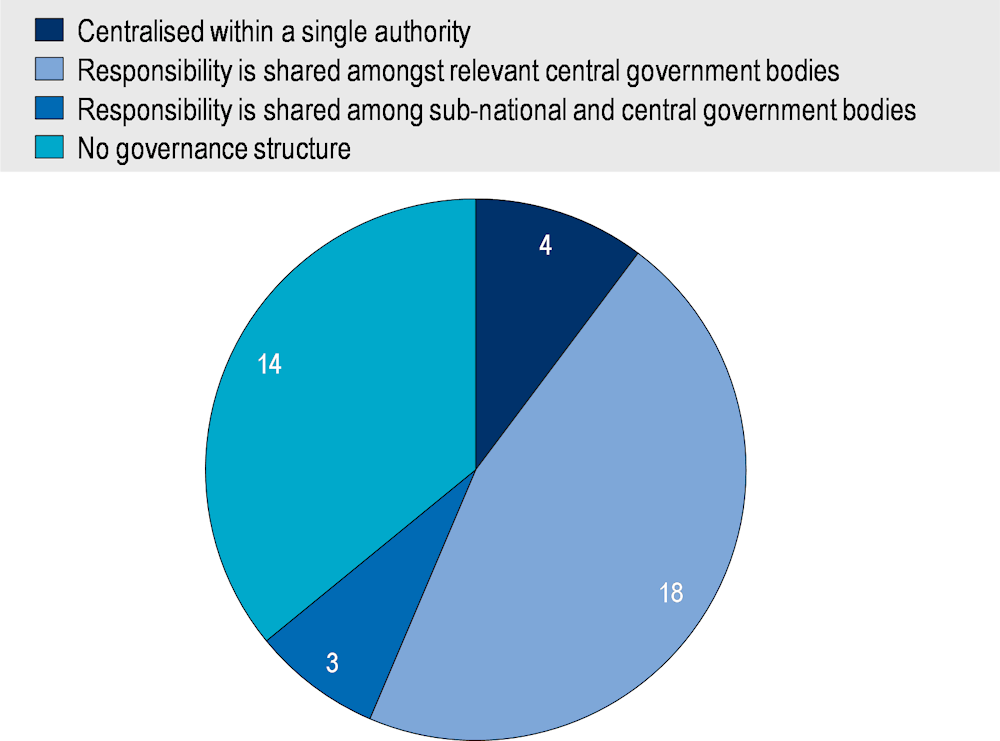

Overall, the institutional arrangement for oversight of IRC remains fragmented across government authorities (Figure 4.2). Only four countries report their IRC agenda to be attributed to a single authority, generally the body with broader regulatory oversight functions (Figure 4.2 and Box 4.2). This limited involvement of regulatory oversight bodies in the oversight of IRC suggests a disconnect between IRC and better regulation, highlighting that international considerations are still only rarely perceived as an integral part of the domestic rulemaking process.

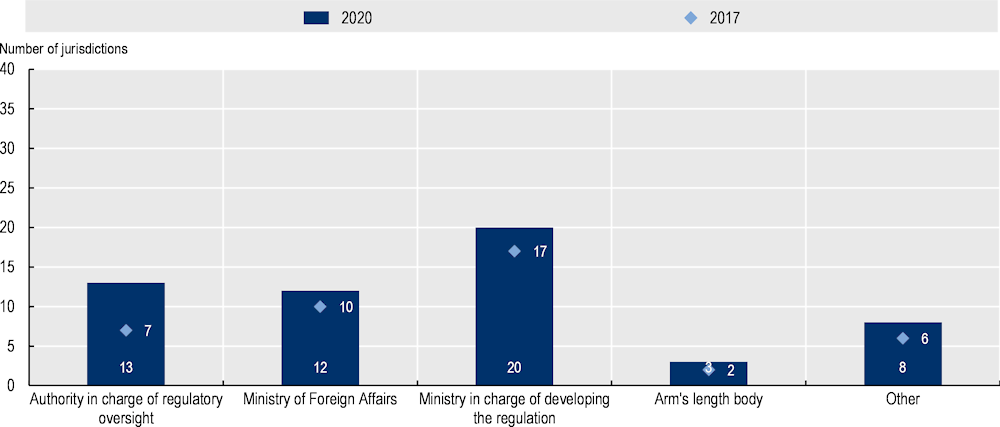

The most common governance structure for IRC remains the sharing of responsibility among relevant central government bodies. This can be easily understood, as the successful implementation of IRC is indeed a whole-of-government endeavour involving necessarily different actors (OECD, 2021[4]). Analysing country practices through the lens of the specific mechanisms of IRC provides some clarity in regard to the allocation of IRC-related responsibilities within governments. For example, specific authorities have increasingly are often made responsible for considering international instruments. While this is still most often the role of Ministries in charge of developing regulation, a notable increase of countries do give this role to regulatory oversight bodies, suggesting an increasing consideration of IRC in the better regulation agenda (Figure 4.3).

However, over a third of respondents continue to lack specific governance structures for overseeing IRC activities (Figure 4.2), making difficult the co-ordination among authorities with IRC functions and knowledge.

Box 4.1. Examples of whole-of-government IRC policy in selected OECD countries

IRC is formally embedded in Canada’s overarching regulatory policy framework, the Cabinet Directive on Regulation (CDR). The CDR requires regulators to assess opportunities for co-operation and alignment with other jurisdictions, domestically and internationally, in order to reduce unnecessary regulatory burdens on Canadian businesses while maintaining or improving the health, safety, security, social and economic well-being of Canadians and protecting the environment.

The Cabinet Regulations No. 707 and 96 govern the Latvian government’s engagement with international organisations and the institutions of the European Union, respectively. These provide strategic direction to Latvia’s IRC activities in these fora, by establishing procedures for the initiation, development, co-ordination, approval and update of regulatory documents.

The IRC legal framework in Mexico is divided into two sets of legal provisions. These include i) two key documents framing IRC practices in domestic rule-making, namely the General Law of Better Regulation and the Federal Law of Metrology and Standardisation; and ii) the legal and policy documents framing Mexico’s regulatory co-operation efforts, including the Law on Celebration of Treaties and the Law on Foreign Trade.

In New Zealand, IRC considerations are embedded in core documents, including the Government Expectations for Good Regulatory Practice and the Government’s Regulatory Management Strategy.

In the United States, the Executive Order 13609 on Promoting International Regulatory Co-operation defines the purpose, features and responsibilities of IRC across government. In particular, it includes the following prerequisites to co-operate with other parties: i) regulatory transparency and public participation; ii) internal whole-of-government co-ordination; and iii) carrying out regulatory assessments.

Source: (OECD, 2018[2]) (OECD, 2020[3]).

Figure 4.2. Organisation of oversight of IRC practices or activities

Note: Data for OECD Countries is based on the 38 OECD member countries and the European Union.

Source: Indicators of Regulatory Policy and Governance Survey 2020.

Figure 4.3. Authorities charged with overseeing the consideration of international instruments

Note: Data for OECD Countries is based on the 38 OECD member countries and the European Union.

Source: Indicators of Regulatory Policy and Governance Survey 2020.

Box 4.2. Practical approaches to IRC oversight in OECD countries

The Treasury Board Secretariat (TBS), the central oversight body in Canada, has a team responsible for supporting and co-ordinating efforts to foster international and domestic regulatory co-operation. This team works with regulators to ensure that they meet their obligations under the CDR and lead Canada’s participation in different regulatory co-operation fora. TBS also works closely with Global Affairs Canada to negotiate regulatory provisions in trade agreements, including those related to IRC.

In New Zealand, responsibility for oversight and promoting consideration of IRC is shared across several agencies. The Treasury is the lead agency for good regulatory practice; the Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment (MBIE) takes the lead on promoting international regulatory coherence; and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade (MFAT) acts as the lead advisor and negotiator on trade policy and provides advice on the process for entering into international treaties. The Treasury and MBIE co-ordinate on different IRC areas, such as developing cross-cutting GRP and regulatory co‑operation chapters in FTAs, representing New Zealand at international regulatory policy fora, and contributing to benchmarking studies of regulation and the regulatory environment.

Source: (OECD, 2018[2]) (OECD, 2020[3]).

Embedding IRC throughout domestic rulemaking

International practices, in the form of evidence and expertise, are an essential source to inform domestic policy development and implementation (OECD, 2021[4]). Traditional regulatory management tools, such as RIA and stakeholder engagement, provide a pathway for countries to ensure consideration of international experiences. Results from the iREG survey and country-level analysis confirm a general upward trend in integrating international considerations into domestic rulemaking (OECD, 2018[2]) (OECD, 2020[3]).

Consideration of international evidence and instruments

Policy makers around the world gather and use evidence in developing their regulations, as do international organisations in developing international instruments. Such evidence can clearly also benefit regulators facing similar challenges in other jurisdictions. Taking stock of international evidence may prove valuable in building the body of evidence for a particular regulation, informing a greater range of options for policy action, and helping to develop an evidence-based narrative around the chosen measure (OECD, 2021[4]).

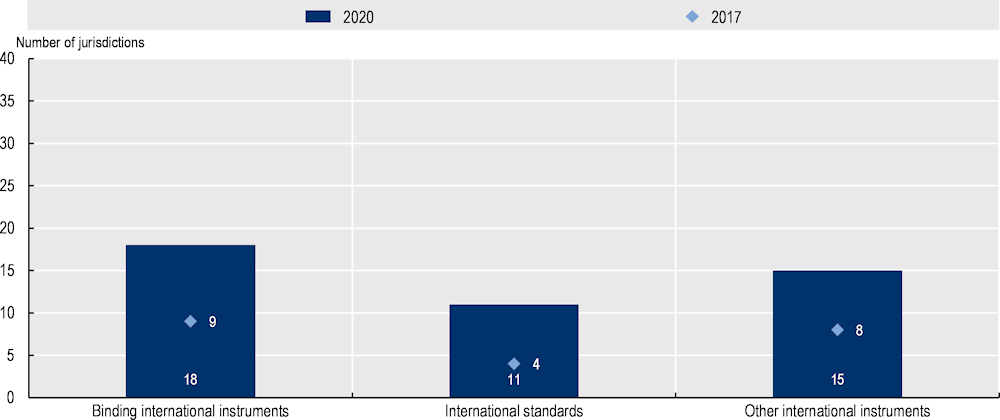

Formal requirements to incorporate international instruments are a common way to ensure international experiences and expertise are considered in domestic rulemaking. A majority of countries have such requirements, particularly for binding international instruments or international standards (Figure 4.4). Several countries also have specific requirements to account for “other” types of instruments, typically for EU Directives or non-binding international instruments. For example, Australia prompts regulators to align legislation with relevant international instruments, while New Zealand encourages the consideration of non-binding resolutions, declarations and guidance in addition to binding instruments such as treaties and conventions. As illustrated in Figure 4.4, the consideration of all types of international instruments has accelerated dramatically in recent years.

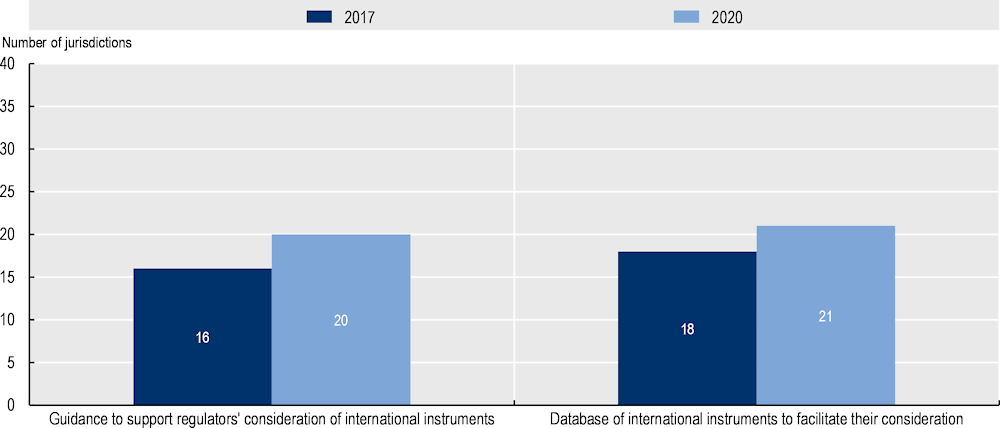

As mentioned above, oversight responsibilities are increasingly being clarified so that authorities – whether a single authority, or several under shared responsibility – oversee the consideration of international instruments. And finally, a slight upward trend since 2017 shows that different forms of guidance or supporting information sources are increasingly made available to incentivise the use of international instruments. This enhanced support suggests a tendency towards systematising the use of international instruments in domestic regulatory activities.

Figure 4.4. Number of jurisdictions with a formal requirement to consider international instruments in rulemaking (2017-2020)

Note: Data for OECD Countries is based on the 38 OECD member countries and the European Union.

Source: Indicators of Regulatory Policy and Governance Survey 2020.

Figure 4.5. Available guidance and databases to facilitate the consideration of international instruments

Note: Data for OECD Countries is based on the 38 OECD member countries and the European Union.

Source: Indicators of Regulatory Policy and Governance Survey 2020.

Box 4.3. The use of international evidence to inform domestic rulemaking

In Chile, Presidential Instruction No. 3/2019 on Regulatory Impact prompts regulators to assess whether there are existing international responses to a similar issue that the domestic regulation is designed to address, and to gauge the extent to which these have been successful.

The One-Stop Shop for New Business Models launched by Denmark in 2018 requires the Danish Business Authority (DBA) to collaborate with neighbouring countries to analyse how EU Directives are implemented in different ways across jurisdictions. It has a particular substantive focus on the sharing economy, the circular economy, e-commerce and data and new technology. Anchored in the Strategy for Denmark’s Digital Growth, under the pillar of agile regulation, this aims to reduce digital barriers to trade and support an innovation-friendly internal market in the EU.

During the drafting of legislative proposals in Estonia, regulators are required to examine available international practices regarding the issue under consideration. If information from foreign legislation contributed to the preparation of a draft, this must be included in the accompanying explanatory letter.

The European Commission Better Regulation Toolbox encourages the use of quality, evidence‑based data in the development of regulation, noting that “[p]rima facie, data from accredited national or international statistical offices or agencies can be used with greater confidence than data from non peer-reviewed literature or from interested stakeholders”. To operationalise this guidance, it notes that, beyond EU-wide sources, many international organisations and institutions compile useful statistics and reports on areas such as energy, environment, agriculture and trade. The Toolbox lists a few examples of such international bodies, including the United Nations (UN), the OECD, the International Energy Agency (IEA), the World Trade Organization (WTO), the World Bank (WBG), the International Monetary Fund (IMF), and the International Labour Organization (ILO).

In Slovenia, regulators – when developing laws and regulations – are required to use information from EU regulations, decisions of the Court of Justice of the European Union, analysis of regulation in the EU acquis, analysis of regulation in at least three legal systems of EU Member States, as well as beyond the EU, from international agreements and analyses of regulation in other legal systems.

Source: 2020 iREG survey answers. See also https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/info/files/better-regulation-toolbox_2.pdf.

Box 4.4. Use of databases to support rulemaking in OECD countries

The use of databases of information and international instruments to underpin regulatory processes represents an increasingly common practice in OECD countries. These facilitate ready access to available international instruments and those to which a given country is a signatory, expand the evidence base contributing to regulations, and streamline the regulatory life-cycle by allowing policy makers to align their proposals with their country’s international commitments.

The government of Mexico has a general database containing procedural information to frame its conduct in international legal fora, through the provision of the full Spanish texts of the Vienna Convention on the Law of the Treaties, the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties between States and International Organisations or between International Organisations, the Law on the Conclusion of Treaties, and the Law on the Approval of International Treaties in Economic Matters. In addition, the database displays Mexico’s human rights commitments under international law, and the international jurisdictions that apply to the country.

The Slovak Republic operates a series of sector-specific databases in key areas, including climate change, international private law, quality infrastructure (standards, metrology and testing), and multilateral, regional, and bilateral trade agreements concluded within the remit of the EU.

Slovenia’s Legal Information System provides access to the legislative documents issued by the European Union and the Council of Europe, as well as the decisions of the European Court of Justice. This is supported by a range of links to government and information resources.

The Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO) of the United Kingdom manages a UK Treaties Online database, which catalogues over 14 000 treaties involving the country. The issuance of Treaty Action Bulletins offers regular updates on the UK’s evolving international commitments, and a dedicated Treaty Enquiry Service supports users in navigating the database.

Source: iREG2021 survey responses, http://www.ordenjuridico.gob.mx/,%20http://www.minzp.sk/sekcie/temy-oblasti/ovzdusie/politika-zmeny-klimy/medzinarodne-zmluvy-dohovory/; http://wwwold.justice.sk/wfn.aspx?pg=l722&htm=l7/l700.htm; http://www.unms.sk/?medzinarodne-zmluvy-a-dohody; http://www.mhsr.sk/obchod/multilateralne-obchodne-vztahy/wto/dolezite-dohody-prijate-v-ramci-wto-a-gatt; http://www.mhsr.sk/uploads/files/3dleJuVE.pdf; http://www.pisrs.si/Pis.web/; https://www.gov.uk/guidance/uk-treaties.

Box 4.5. Embedding international obligations, standards and practices in domestic regulations

Australia has a cross-sectoral requirement to consider “consistency with Australia’s international obligations and relevant international accepted standards and practices” (RIA Guide for Ministers’ Meetings and National Standards Setting Bodies). Wherever possible, regulatory measures or standards are required to be compatible with relevant international or internationally-accepted standards or practices in order to minimise impediments to trade. If a regulatory option involves establishing or amending standards in areas where international standards already apply, the proponent should document whether (and why) the proposed standards differ from the international standard.

Adopted in 2018, Israel’s Government Resolution 4398 establishes a principle that the development of domestic regulation will be based on international practices and rules. In addition, in the design phase of domestic standards, the Israeli Standards Institute is required to check whether there is an applicable international standard. From 2017-2020, the Ministry of Economy enacted a three-year plan to convert and align Israeli standards with international standards. This facilitated the removal of national deviations from more than 500 standards.

Mexico has various provisions encouraging the adoption of international standards, mostly bearing on technical regulations and standards. If international standards do not exist, the consideration of foreign standards is encouraged. This applies particularly to standards from two major trading partners, the United States and the EU. To support regulators with this obligation, guidance on how to embed international standards in domestic technical regulations or standards was developed, and some examples of international and foreign standards are listed in the legal obligation.

The New Zealand Government Expectations for Good Regulatory Practice apply to all of New Zealand’s regulatory systems and, therefore, to all kinds of regulatory measures and actors. This provides that “the government believes that durable outcomes of real value to New Zealanders are more likely when a regulatory system … is consistent with relevant international standards and practices to maximise the benefits from trade and from cross border flows of people, capital and ideas (except when this would compromise important domestic objectives and values)”. Regulatory agencies are expected to undertake “systematic impact and risk analysis, including assessing alternative legislative and non-legislative policy options, and how the proposed change might interact or align with existing domestic and international requirements within this or related regulatory systems”.

In the United States, the guidance of the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) on the use of voluntary consensus standards states that “in the interests of promoting trade and implementing the provisions of international treaty agreements, your agency should consider international standards in procurement and regulatory applications”. In addition, the Executive Order 13609 on Promoting International Regulatory Co-operation states that agencies shall, “for significant regulations that the agency identifies as having significant international impacts, consider, to the extent feasible, appropriate, and consistent with law, any regulatory approaches by a foreign government that the United States has agreed to consider under a regulatory co-operation council work plan”. The scope of this requirement is limited to the sectoral work plans that the United States has agreed to in Regulatory Cooperation Councils.

Source: (OECD, 2018[2]) (OECD, 2020[3]).

Engaging foreign stakeholders and ensuring transparency

Transparency of domestic regulatory processes can strengthen the predictability of the domestic regulatory framework for interested foreign parties. With active engagement, it can also open the possibility for valuable inputs from foreign stakeholders. Engaging these stakeholders in the regulatory process may offer valuable evidence on unintended transboundary impacts of regulatory drafts and help raise awareness of regulatory approaches in other jurisdictions (Basedow and Kauffmann, 2016[15]). OECD studies have shown that regulators rarely pursue specific efforts to engage foreign stakeholders when developing laws and regulations, despite general openness of consultation procedures to any stakeholders – including those from foreign jurisdictions (OECD, 2018[16]). Compulsory notification of draft regulations to international fora provides an important means by which to alert and draw inputs from foreign stakeholders (OECD, 2021[4]). In practice, such notifications of draft measures are most frequently used to assess trade impacts of regulations. Notifications of draft measures to trading partners is indeed required by certain trade agreements and WTO commitments under the SPS and TBT Agreements. However, some countries report also notifying to other international fora. Germany, for example, has notification obligations to the Central Commission for the Navigation of the Rhine (CCNR), a transboundary water management body which also includes France, the Netherlands, Switzerland, and Belgium. In the same vein, the Netherlands informs the International Labour Organization (ILO), Council of Europe, and Benelux Economic Union – which also comprises Belgium and Luxembourg – of new regulations where relevant.

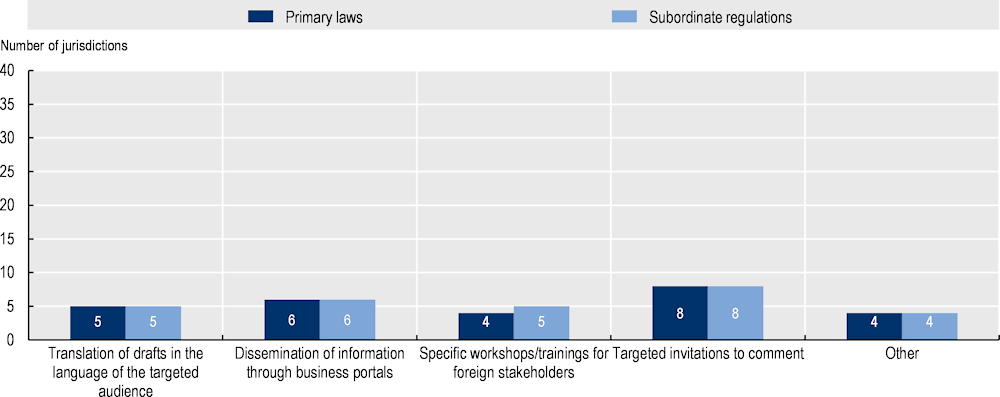

Despite the invaluable information that can be gathered through notification of draft measures to international fora or foreign partners, a disconnect has traditionally persisted between these processes and the regulatory policy agenda, therefore failing to leverage useful information sources gathered in other parts of government (OECD, 2018[16]). Consistent with previous trends, many countries still do not conduct specific efforts to engage with foreign stakeholders in their rulemaking processes (22 respondents indicate never doing so for primary laws, and 21 for subordinate regulations) (Figure 4.6).

Nevertheless, the countries that do reach out to foreign stakeholders confirm multiple means of doing so (Box 4.6). Targeted invitations to comment remains the most frequently used means to reach foreign stakeholders (Figure 4.6).

Box 4.6. Engaging External Stakeholders in the Development of Domestic Legislation

Latvia conducts consultations with foreign stakeholders in the development of some primary laws, with a particular focus on those from across the Baltic region (i.e. Estonia and Lithuania). In addition, the government engages regularly with the external stakeholders comprising the Foreign Investors’ Council in Latvia (FICIL), which includes a selection of firms, chambers of commerce, representatives from the Stockholm School of Economics in Riga and French Foreign Trade Advisors.

The government of Norway frequently launches consultations with selected international stakeholders for emerging regulatory proposals that have transboundary impacts. These efforts are targeted to particular firms, associations and organisations, but remain ad-hoc in nature. Two recent examples include reforms to the Financial Undertakings Act made by the Ministry of Finance, and a comprehensive new law on gambling under development by the Ministry of Culture.

Source: Indicators of Regulatory Policy and Governance Survey 2020.

Figure 4.6. Approaches to assessing impacts on foreign jurisdictions and to targeting jurisdictions for assessment for subordinate regulations

Note: Data for OECD Countries is based on the 38 OECD member countries and the European Union.

Source: Indicators of Regulatory Policy and Governance Survey 2020.

Assessing impacts beyond borders

Accounting for international impacts in ex ante regulatory impact assessment

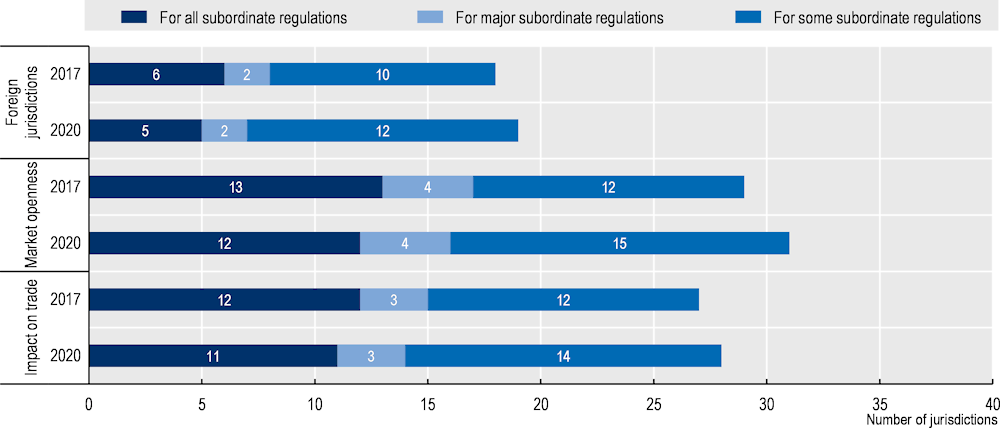

In addition to engaging with foreign stakeholders in regulatory process, countries may also promote IRC by integrating an analysis of possible international impacts systematically into their RIA processes. RIAs offer an effective avenue to promote IRC by enabling countries to consider the impact of their activities beyond their borders. As observed in both 2014 and 2017, countries report a range of IRC-related impacts in their RIA processes, in particular by charting specific effects on trade, market openness, and impacts on foreign jurisdictions (Figure 4.7). Consideration of the trade and market openness impacts of regulatory drafts remain the most frequent, with almost 75% of respondents examining trade implications and around 80% accounting for market openness effects. This illustrates an increasing trend since 2017. Consideration of domestic effects of regulation on foreign jurisdictions is less systematic, with only a handful of countries doing so for all subordinate regulations (Figure 4.7).

Given the specific methodology involved in considering international impacts, embedding such considerations can require more time and human resources to reach out to different colleagues across government with the right expertise. Some countries have therefore chosen to use an initial RIA “calculator” phase to determine the types of international impacts to assess. For example, to apply a more thorough calculation of trade impacts only when relevant, Mexico has included a “trade filter” in its RIA calculator. This integrates international trade impacts into the RIA process from the outset of the process. The questions aim to guide regulators in determining whether their draft may affect international trade. If the initial filter points towards a prima facie impact on trade, regulators then undergo a RIA process with more detailed questions related to the impacts of their draft on foreign trade (OECD, 2018[2]).

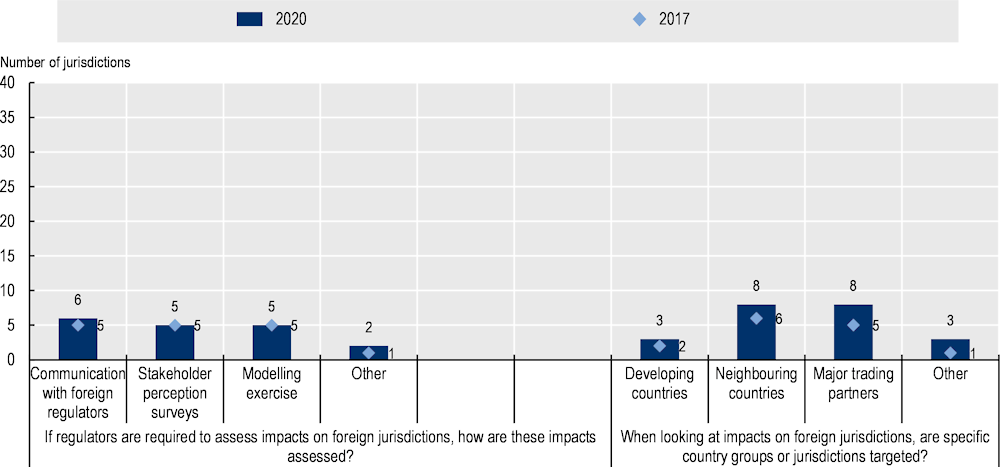

Of the 19 countries that consider the impacts of their regulations on foreign jurisdictions, neighbouring countries and major trading parties increasingly continue to be the most common jurisdictions taken into account. Countries steadily report using a mix of approaches to assessing impacts, including communication with the other jurisdictions’ regulators, use of perception surveys to business and other stakeholders and modelling exercises (Figure 4.8).

Figure 4.7. Number of jurisdictions with requirements for consideration of impacts on foreign jurisdictions, market openness, or trade as part of RIA

Note: Data for OECD Countries is based on the 38 OECD member countries and the European Union.

Source: Indicators of Regulatory Policy and Governance Surveys 2014, 2017 and 2020: http://oe.cd/ireg.

Figure 4.8. Approaches to assessing impacts on foreign jurisdictions and to targeting jurisdictions for assessment for subordinate regulations

Note: Data for OECD Countries is based on the 38 OECD member countries and the European Union.

Source: Indicators of Regulatory Policy and Governance Survey 2020.

Box 4.7. Country experiences in assessing cross-border impacts in RIA

Chile included items on the effects of regulatory proposals on trade, as well as on international standards and international agreements in its Presidential Instruction No. 3/2019 on Regulatory Impact. Regulators are required to rate the magnitude of this impact, on a spectrum ranging from nothing or almost nothing, slightly, moderately, reasonably, or significantly.

Denmark systematically assesses the impacts of new regulations on border obstacles across the Nordic region as set forth in Parliamentary Resolution V57 and Paragraph 2.8.12.3 of its Guidelines on Legal Quality. To minimise and prevent raising unnecessary barriers, proposals in areas potentially affected by border obstacles – including in relation to free movement – must involve an examination of the legislation in other Nordic countries prior to their submission to the Folketing (Parliament). This extends to the implementation of EU Directives, and the impacts on the relationship with the Faroe Islands and Greenland.

Mexico introduced a trade filter in the RIA process that provides an opportunity to assess the impacts on exports and imports of a regulatory measure and triggers the involvement of the Ministry of Economy for notification to WTO. Through nine detailed questions, this trade filter allows regulators to identify the potential trade impacts of draft regulations. If such an impact is identified, a specific trade RIA is conducted and the draft measure is notified to the WTO, thus providing the possibility to gather feedback on the measure from other WTO members and potentially stakeholders.

The United Kingdom introduced a new RIA template in 2018, including a new question related to the impacts of UK regulations on international trade and investment (i.e. Is this measure likely to impact on trade and investment? Yes/No). This new template was trialled in 2019. Based on the first set of responses to this template, the UK Department of International Trade (DIT), Better Regulation Executive (BRE) and Regulatory Policy Committee (RPC) are working together to refine the methodologies to support departments in measuring the trade impacts of their draft measures.

Assessing the cross-border impacts of regulations through post-implementation reviews

The full impact of a regulatory measure is only known after its implementation. Ex post evaluation thus provides a critical opportunity to identify the impacts of potential divergences with international frameworks as well as trade and other IRC impacts of laws and regulations (Kauffmann and Basedow, 2016[17]). It also allows regulators to map the state of international knowledge on the regulated area, take stock of new approaches adopted by other jurisdictions that may have proved successful, and benchmark against regulations implemented in other jurisdictions which pursue similar objectives using alternative approaches (OECD, 2020[18]). Overall, this can help to build the evidence on IRC throughout the rule-making cycle and apply an IRC lens to the stock of regulation.

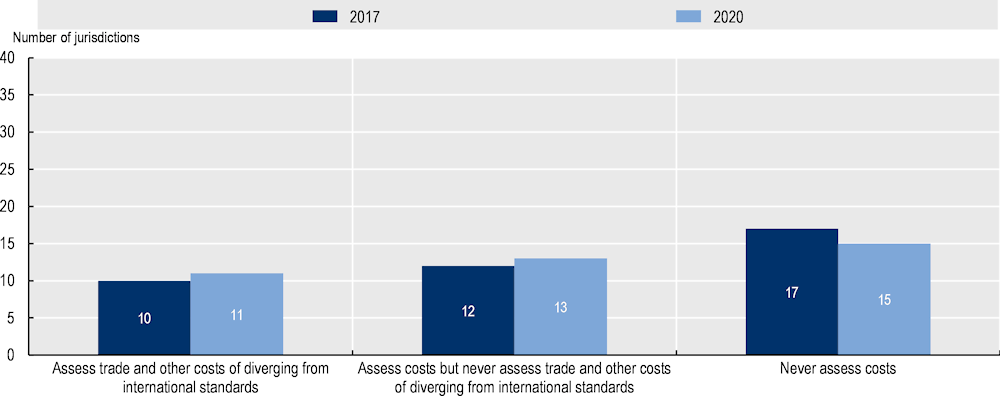

Traditionally, the use of ex post evaluation related to IRC is rarely observed. While little variation can be observed for IRC ex post cost assessments in secondary legislation, there has been a slight upward trend in the number of countries that account for IRC-related costs in their ex post evaluations of primary laws (Figure 4.9). Some OECD countries provide guidance to ensure that IRC is part of their regulatory management tools, including ex post evaluation (Box 4.8). Evidence from standalone chapters on good regulatory practices and IRC in trade agreements indicates that countries increasingly regard ex post reviews as a mechanism of regulatory co-operation among parties. This includes promoting the exchange of methodologies and outcomes of these evaluations (Box 4.9).

Figure 4.9. Number of jurisdictions that assess costs in ex post evaluations of primary laws, including trade and other costs of diverging from international standards

Note: Data for OECD Countries is based on the 38 OECD member countries and the European Union.

Source: Indicators of Regulatory Policy and Governance Survey 2020.

Box 4.8. Embedding IRC in ex post evaluations

Canada

In the updated version of Canada’s Directive on Regulation of September 2018, regulatory co-operation is embedded throughout the regulatory lifecycle:

Regulators are required to assess early opportunities for alignment with other jurisdictions (domestically and internationally) to reduce unnecessary regulatory burden on Canadian businesses while maintaining or improving the health, safety, security, social and economic well-being of Canadians, and protecting the environment;

Where a Canada-specific approach is required, regulators must provide a rationale in the regulatory impact assessment statement;

Forward regulatory plans require identification of regulatory co-operation issues; and

As part of stock reviews, regulators must identify new opportunities to reduce regulatory burdens on stakeholders through regulatory co-operation activities.

New Zealand

The New Zealand Government Expectations for Good Regulatory Practice apply to all of New Zealand’s regulatory systems and therefore to all kinds of regulatory measures and actors. Part A of the Expectations sets out requirements for the design of regulatory systems. This provides that “the government believes that durable outcomes of real value to New Zealanders are more likely when a regulatory system … is consistent with relevant international standards and practices to maximise the benefits from trade and from cross border flows of people, capital and ideas (except when this would compromise important domestic objectives and values)”. New Zealand applies the term international standards in this context more broadly than in this report, going beyond the WTO definition to cover all international instruments. Part B sets out expectations for regulatory stewardship by government agencies. The regulatory stewardship role includes responsibilities for monitoring, reviews and reporting on existing regulatory systems. Regulatory agencies are expected to “periodically look at other similar regulatory systems, in New Zealand and other jurisdictions, for possible trends, threats, linkages, opportunities for alignment, economies of scale and scope, and examples of innovation and good practice”. As part of regulatory stewardship responsibilities for robust analysis and implementation support for changes to regulatory systems, regulatory agencies are expected to undertake “systematic impact and risk analysis, including assessing alternative legislative and non-legislative policy options, and how the proposed change might interact or align with existing domestic and international requirements within this or related regulatory systems”.

Box 4.9. Exchange of ex post evaluations results as an avenue for regulatory co-operation

As trade agreements have broadened in content and scope, they provide a route for promoting regulatory quality across countries. A number of recent trade agreements have incorporated dedicated horizontal chapters that generally aim at promoting a minimum level of GRPs and/or IRC among partners.

In encouraging parties to strengthen regulatory policy, these horizontal chapters promote the systematic adoption of regulatory management tools available to policy-makers to ensure the quality of laws and regulations, including ex post evaluations.

Notably, the dedicated chapters in the Brazil-Chile Trade Agreement, EU-Japan Economic Partnership Agreement, the CETA and USMCA provide for ex post reviews as an avenue of regulatory co-operation among parties. The CETA notes that, as part of its IRC activities, parties may conduct ex post evaluations of regulations or policies, compare the methods and assumptions used in these reviews and share summaries of their outcomes, when applicable. Similarly, the chapter in the Brazil-Chile Trade Agreement provides that parties may exchange information on ex post assessment methodologies and practices. The EU-Japan agreement encourages parties to exchange of information on good regulatory practices, including on retrospective evaluations. Finally, the USMCA recognises that periodically exchanging information on post-implementation reviews of regulations affecting trade or investment may contribute to minimising regulatory divergences.

Notes: The agreement under review in (Kauffmann and Saffirio, 2021[8]) include: the Agreement between New Zealand–Singapore on a Closer Economic Partnership (NZ– Singapore CEP Upgrade), the Agreement between the EU and Japan for an Economic Partnership (EU–Japan EPA), the Canada – EU Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (CETA); the Brazil – Chile Trade Agreement; the Chile – Uruguay Trade Agreement; the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP), the First Amendment to the Additional Protocol of the Pacific Alliance Framework Agreement (Pacific Alliance); and the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA).

Source: (Kauffmann and Saffirio, 2021[8]).

Bilateral, regional and multilateral co-operation: leveraging international co-operation efforts to improve the quality of domestic rulemaking

Domestic policy makers have access to a wealth of bilateral, regional and multilateral platforms to co‑operate and inform their approaches to national policy challenges (OECD, 2013[11]) (OECD, 2014[19]). Bilateral, regional and multilateral forms of co-operation are an important complement to purely unilateral domestic actions. Such international co-operation lays the foundation for institutionalised and continuous collaboration and greater coherence in regulatory matters. The modalities of international co-operation will depend on the legal and administrative system and geographic location of the country, as well as on the sector or policy area under consideration (OECD, 2021[4]).

These platforms increasingly take different forms, with multiple actors populating the global landscape today ranging from inter-governmental organisations (IGOs), trans-governmental networks (TGNs) and private standard-setters. These organisations develop a fast-growing body of norms and standards (OECD, 2019[20]), which support national regulatory efforts in addressing the increasingly internationalised policy challenges of today. During the COVID-19 crisis, a number of bilateral and regional collaboration efforts emerged to address urgent needs with likeminded and neighbouring countries. Given the global scope of the pandemic, the role of multilateral organisations was particularly apparent. This highlights their relevance as hubs for information and developing international instruments, both crucial support elements for domestic policy makers (OECD, 2020[1]) (OECD, 2020[21]). Beyond the pandemic, other recent initiatives for international co-operation also continue emerging to address new and evolving policy priorities, such as for example to foster global co-operation in response to innovation (Box 4.12).

Despite IOs’ importance in supporting domestic rulemaking, the previous Regulatory Policy Outlook highlighted a pressing need for IOs to increase the transparency, effectiveness and impact of their instruments – notably through the adoption of good regulatory practices (GRPs), such as those promoted in the 2012 Recommendation for domestic rulemaking (OECD, 2018[13]). Although more efforts are needed, recent initiatives by individual IOs, in addition to the Compendium of International Organisations’ Practices: Working Towards More Effective International Rulemaking (IO Compendium) developed collaboratively by the Partnership of IOs for Effective International Rulemaking, show measures and initiatives used by IOs to strengthen their rulemaking processes with a view to making their international instruments more effective.

This section presents the role of international instruments in feeding into domestic rulemaking, both through results from the iREG survey and of recent OECD analytical work. It also highlights the specific role that IOs had in this regard during the COVID-19 crisis. Finally, it outlines the specific efforts made by IOs to improve the quality of international rulemaking. The primary information sources for this section include the results of the 2018 Survey of International Organisations, the recent studies of the World Organisation for Animal Health (OIE) (OECD, 2020[22]), the International Bureau of Weights and Measures (BIPM) (OECD, 2020[23]) and the World Trade Organisation (WTO) (OECD/WTO, 2019[7]), and preliminary results from the IO Compendium.

International instruments in support of national regulatory efforts

International expertise and evidence is vital to support domestic policy makers in developing effective, evidence-based policies in a highly interconnected world. IOs serve, first and foremost, as institutional fora for actors to engage in IRC. They possess a large amount of information and experience from which governments and agencies can draw (OECD, 2014[19]). In other words, they provide a framework to “orchestrate” the sharing of evidence among their constituencies in their respective policy areas in various forms (raw, compiled in databases, analysed in thematic or country reports).

This regular and permanent exchange of information function allows IO Members to share views on emerging policy challenges they are facing and envisage various policy options available for addressing them. This is the case, for example, for the WTO Technical Barriers to Trade and Sanitary and Phytosanitary Committees, which have such an “incubator” role, via thematic sessions or workshops in which Members exchange for instance on sector-specific ongoing, new or emerging regulatory issues (e.g. energy efficiency, or nutrition labelling) (OECD/WTO, 2019[7]).

This function of IOs as “data hubs” is instrumental in the COVID-19 crisis. Practically all IOs that host normative instruments, including the OECD, established a COVID-19 dedicated website to serve as a platform for information exchange in their respective mandates (OECD, 2020[1]). Beyond these public websites, they also provide a platform for members to exchange on their respective measures and find common positions (Box 4.10).

Beyond information exchange, IOs allow for the aligning of approaches across countries facing similar policy issues, such as through the development of international terminologies or instruments. Indeed, when national delegates or regulators reach agreements on IRC, or when they adopt rules through institutionalised procedures, the results can be embodied in various forms of normative instruments (OECD, 2014[19]). These international instruments, which can be used in national legislation, can increase coherence in regulatory approaches across countries.

In the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, IOs were under great pressure to deliver for their constituencies in coping with the crisis (OECD, 2020[1]). Making use of their normative functions and respective areas of expertise, a number of IOs developed guidance adapting their traditional tools to the context of the pandemic – either advising their constituencies on how to deal with its impacts in their area or the related global social and economic crisis (Box 4.11).

Box 4.10. IOs as platforms for emergency information exchange in times of COVID-19

A wide range of IOs responded to the urgent data needs of their constituencies to deal with the crisis originating in the COVID-19 pandemic.

The World Health Organization (WHO) played a highly visible role in this respect, by compiling and disseminating health statistics essential to evaluate health programmes and making recommendations on international health matters. The WHO’s International Health Regulations (IHR) provide an overarching legal framework that defines countries’ obligations in handling acute public health risks that have the potential to cross borders. The IHR “are the sole binding global legal instrument dedicated to the prevention and control of the international spread of disease” (Burci, 2020[24]). Under the IHR, the WHO acts as a central co-ordinating body for addressing the pandemic, receiving notifications on outbreaks and disseminating information to help scientists address an epidemic at the global level.

The OECD compiles real time data and analysis on the multifaceted consequences of the global crisis, from health to education, employment and taxes.1

The World Organisation for Animal Health (OIE) compiles data from Members on any outcomes of investigations in animals to detect infections with SARS-CoV-2.2

The World Trade Organization (WTO) made available notifications of COVID-related measures3 and has issued a series of information notes on COVID-19 and world trade.

The World Tourism Organization (UNWTO) has carried out an impact assessment of the COVID-19 crisis on the tourism sector.4

The Council of European Energy Regulators allowed energy regulators to share notes on their respective national measures to address the COVID-19 induced decrease in energy demand; as well as to share practices on how to support vulnerable customers.

The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) has developed a Big Data tool on food chains under the COVID-19 pandemic that gathers, organises and analyses daily information on the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on food and agriculture, value chains, food prices, food security and undertaken measures. As stated on the FAO website, the tool’s ultimate aim is to provide countries with facts and information on how the pandemic impacts the food chains to build their decisions.5

The World Customs Organization’s (WCO) Customs Enforcement Network Communication Platform (CENcomm) allows customs worldwide to share intelligence on fake medical supplies and medicines.

2. See “events in animals” section at https://www.oie.int/scientific-expertise/specific-information-and-recommendations/questions-and-answers-on-2019novel-coronavirus/.

Source: (OECD, 2020[1]).

Box 4.11. IOs as platforms for joint action in the context of COVID-19

As platforms for joint action, a large number of IOs developed guidance in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic to support their constituency in facing the health, economic or social crisis

The OECD provided tailored guidance to help countries during the crisis in its various policy areas, including on maintaining regulatory quality in times of crisis.

The International Labour Organization (ILO) prepared a Prevention and Mitigation of COVID-19 at Work Action Checklist that offered a collaborative approach to assess pandemic risks, as a step to take measures to protect the safety and health of workers.

The International Maritime Organization (IMO) provided advice and guidance to facilitate maritime trade and preserve the health of seafarers.

The International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) developed a number of “quick reference guides” to provide guidance of a particular subject area in addressing COVID-19 related risks to the continuity of aviation business and operations.

The International Criminal Police Organization (INTERPOL) developed guidelines on how to protect law enforcement and first responders.

The Commonwealth developed Guidelines on sport, exercise and physical activity and Sport policy during the coronavirus pandemic.

The World Customs Organization (WCO) developed guidance on a number of issues to facilitate movement of essential goods across borders.

The Bureau International des Poids et Mesures (BIPM) is working with National Metrology Institutes on validation, calibration and verification of measurement instruments relevant for a range of COVID-19 essential products and to develop protocols for organising scientific comparisons to underpin antigen and vaccine testing.

Source: (OECD, 2020[1]).

Box 4.12. Agile Nations: a new frontier in international regulatory co-operation?

In November 2020, Canada, Denmark, Italy, Japan, Singapore, UAE and UK sign the Agile Nations Charter, establishing an intergovernmental network to foster global co-operation in response to innovation. The central objective of this network is to strike an effective balance between the creation of a regulatory environment conducive to the emergence and proliferation of new innovations, while facilitating better public management of cross-border risks.

In sum, the Agile Nations Charter sets out each country’s commitment to creating a regulatory environment in which new ideas can thrive. The agreement paves the way for these nations to co-operate in helping innovators navigate each country’s rules, test new ideas with regulators and scale them across the seven markets. Priority areas for co-operation include the green economy, mobility, data, financial and professional services, and medical diagnosis and treatment.

Within the Charter, the Participating governments acknowledge that good practice in rulemaking is evolving and will review these practices regularly, giving consideration to the work of the OECD, the World Economic Forum and other international organisations.

Improvement of quality and effectiveness of international instruments

The OECD finds that international instruments have become a significant channel of domestic regulators’ implementation of IRC (OECD, 2018[13]). Nevertheless, for regulators to more systematically consider international instruments when developing and applying domestic regulatory frameworks, these instruments need to be of high quality, widely and easily accessible, and fit to achieve the public interest in their own jurisdiction.

The OECD identifies five core priorities to make international instruments more effective: clarifying the landscape of international instruments to describe existing terminologies and related legal effects; strengthening the implementation of international instruments at the domestic level; developing a culture of evaluation of international instruments; ensuring efficient stakeholder engagement and maximising opportunities for co-ordination across IOs (OECD, 2016[25]). Under the framework of the OECD Regulatory Policy Committee, the Partnership for Effective International Rulemaking (“IO Partnership”) has worked on these five challenges, gathering lessons from domestic regulatory policy for international rulemaking. The Compendium of International Organisations’ Practices: Working Towards More Effective International Instruments (“IO Compendium”) showcases an increasing number of trends and individual examples of IO practices that seek to ensure the quality of international instruments (Box 4.13), and lays down key principles to improve the effectiveness of international rulemaking. As a practical tool for IO Secretariats in their rulemaking activities, the IO Compendium also provides clarity for domestic regulators to navigate the landscape of international instruments and to identify the most relevant instruments for them. It also represents an extensive information source on the tools of regulatory quality used at the international level (OECD, 2021[26]).

Box 4.13. Examples of IO practices aimed at improving transparency, evaluation and co-ordination of international instruments

Clarifying a variety of international instruments

In line with the general efforts to provide better visibility and clarity into the work of IOs and their instruments, the Online Compendium of OECD Legal Instruments provides the texts of all the legal instruments developed within the framework of the OECD since 1961 – including abrogated instruments – together with information on the process for their development and implementation as well as non‑Member adherence. A downloadable booklet gathering this information is also available for each instrument. The Compendium is available to the general public and maintained by the OECD Directorate for Legal Affairs.

Strengthening implementation

As part of a broad strategy to strengthen implementation of its standards, the World Organisation for Animal Health (OIE) is designing an Observatory to monitor the implementation of OIE international standards. Data collected and analysed is planned to assist the OIE in gaining a greater understanding of challenges to the implementation of standards and to evaluate the relevance and efficiency of OIE international standards. Ultimately, the outcomes of the Observatory are expected to help improve the OIE standard setting process, feeding back into the development and revision of OIE standards.

Stakeholder engagement

With the aim of improving the effectiveness of its stakeholder engagement efforts, the WHO has set a whole-of-organisation policy on stakeholder engagement with its “Framework of Engagement with non-State Actors”. This frames its engagement with NGOs, private sector entities, philanthropic foundations and academic institutions. The Framework identifies various categories of interaction in which the WHO engages with non-State actors: participation in, inter alia, consultations, hearings, and other meetings of the Organization; provision of financial or in-kind contributions; provision of evidence; advocacy activities; and technical collaboration, including through product development, capacity-building, operational collaboration in emergencies and contribution to the implementation of WHO’s policies. It establishes mechanisms to manage conflicts of interest and other risks of engagement.

Evaluation

To ensure that ISO standards remain up-to-date and globally relevant, they are reviewed at least every five years after publication through the Systematic Review process. This is frequent practice among private standard-setting bodies, and similar processes are in place at IOs such as OIML or ASTM International. Through this process, ISO members review the document and its use in their country (in consultation with their stakeholders) to decide whether it is still valid, should be updated, or withdrawn. ISO also provides a document outlining Guidance on the Systematic Review process.

Increasing co-ordination

The FAO-OIE-WHO Collaboration for “One Health” sets out a strategic direction for the three Organisations to develop a long-term basis for co-ordinating global activities to address health risks at the human-animal-ecosystems interface, and ensure consistency across the standard-setting activities of the three organisations involved.

Source: (OECD, 2020[22]) (OECD, 2019[20]); (OECD, 2021[26]).

References

[15] Basedow, R. and C. Kauffmann (2016), “International Trade and Good Regulatory Practices: Assessing The Trade Impacts of Regulation”, OECD Regulatory Policy Working Papers, No. 4, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/5jlv59hdgtf5-en.

[14] BEIS (2020), International Regulatory Cooperation for a Global Britain Government Response to the OECD Review of International Regulatory Cooperation of the UK, https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/913730/international-regulatory-cooperation-for-a-global-britain.pdf (accessed on 8 February 2021).

[10] Botta, E. et al. (2021), “The economic benefits of international co-operation to improve air quality in Northeast Asia”.

[24] Burci, G. (2020), The Outbreak of COVID-19 Coronavirus: are the International Health Regulations fit for purpose? – EJIL: Talk!, European Journal of International Law Blog, https://www.ejiltalk.org/the-outbreak-of-covid-19-coronavirus-are-the-international-health-regulations-fit-for-purpose/ (accessed on 7 June 2021).

[17] Kauffmann, C. and R. Basedow (2016), “The political economy of international co-operation – a theoretical framework to understand international regulatory co-operation (IRC)”, OECD, Paris, unpublished.

[8] Kauffmann, C. and C. Saffirio (2021), “Good regulatory practices and co-operation in trade agreements A historical perspective and stocktaking”, OECD Regulatory Policy Working Papers, No. 14, OECD, Paris.

[26] OECD (2021), Compendium of International Organisations’ Practices: Working Towards More Effective International Instruments, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/846a5fa0-en.

[4] OECD (2021), International Regulatory Co-operation, OECD Best Practice Principles for Regulatory Policy, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/5b28b589-en.

[21] OECD (2020), IOs in the context of COVID-19: Adapting rulemaking for timely, evidence-based and effective international solutions in a global crisis – Summary Note of COVID-19 Webinars of the Partnership of International Organisations for Effective International Rule-making, https://www.oecd.org/gov/regulatory-policy/Summary-Note-COVID-19%20webinars.pdf (accessed on 16 June 2021).

[1] OECD (2020), No policy maker is an island: The international regulatory co-operation response to the COVID-19 crisis, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/3011ccd0-en.

[22] OECD (2020), OECD Study on the World Organisation for Animal Health (OIE) Observatory: Strengthening the Implementation of International Standards, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/c88edbcd-en.

[3] OECD (2020), Review of International Regulatory Co-operation of the United Kingdom, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/09be52f0-en.

[18] OECD (2020), Reviewing the Stock of Regulation, OECD Best Practice Principles for Regulatory Policy, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/1a8f33bc-en.

[9] OECD (2020), Study of International Regulatory Co-operation (IRC) arrangements for air quality: The cases of the Convention on Long-Range Transboundary Air Pollution, the Canada-United States Air Quality Agreement, and co-operation in North East Asia, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/dc34d5e3-en.

[23] OECD (2020), The Case of the International Bureau of Weights and Measures (BIPM), OECD, Paris, https://www.oecd.org/governance/regulatory-policy/international-regulatory-cooperation-and-international-organisations-the-case-of-the-international-bureau-of-weights-and-measures.pdf.

[5] OECD (2019), Regulatory effectiveness in the era of digitalisation, http://www.oecd.org/gov/regulatory-policy/Regulatory-effectiveness-in-the-era-of-digitalisation.pdf (accessed on 28 April 2020).

[20] OECD (2019), The Contribution of International Organisations to a Rule-Based International System: Key Results from the Partnership of International Organisations for Effective Rulemaking, https://www.oecd.org/gov/regulatory-policy/IO-Rule-Based%20System.pdf.

[16] OECD (2018), “Fostering better rules through international regulatory co-operation”, in OECD Regulatory Policy Outlook 2018, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264303072-9-en.

[13] OECD (2018), OECD Regulatory Policy Outlook 2018, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264303072-en.

[2] OECD (2018), Review of International Regulatory Co-operation of Mexico, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264305748-en.

[6] OECD (2017), International Regulatory Co-operation and Trade: Understanding the Trade Costs of Regulatory Divergence and the Remedies, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264275942-en.

[25] OECD (2016), International Regulatory Co-operation: The Role of International Organisations in Fostering Better Rules of Globalisation, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264244047-en.

[19] OECD (2014), International Regulatory Co-operation and International Organisations: The Cases of the OECD and the IMO, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264225756-en.

[11] OECD (2013), International Regulatory Co-operation: Addressing Global Challenges, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264200463-en.

[12] OECD (2012), Recommendation of the Council on Regulatory Policy and Governance, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264209022-en.

[7] OECD/WTO (2019), Facilitating Trade through Regulatory Cooperation: The Case of the WTO’s TBT/SPS Agreements and Committees, OECD Publishing, Paris/World Trade Organization, Geneva, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/ad3c655f-en.

Note

← 1. Cf. Mutual Legal Assistance Agreement between the Federal Republic of Germany and the Republic of Austria on Legal and Administrative Assistance in Customs, Excise and Monopoly Matters, Order of the German Constitutional Court from 22 March 1983 (BVerfGE 63, 343-380 (370).