This chapter assesses the governance of the National Pension Fund, and its investment and risk management policies, using international best practices and the OECD Recommendation on the Core Principles of Private Pension Regulation. The chapter ends with some policy recommendations that could support the National Pension Fund in its mission and help these useful reserves to last longer.

OECD Reviews of Pension Systems: Korea

4. Governance, investment policy and risk management of the National Pension Fund

Abstract

Korea has large reserves to support the financing of its public pay-as-you-go pension system. These reserves are held in a separate fund, the National Pension Fund. Similar funds, known as public pension reserve funds, exist in over 20 OECD countries (OECD, 2021[1]). Korea’s public pension reserve fund is one of the largest worldwide, with assets worth USD 796 billion at end‑2020, which is 45% Korea’s GDP (OECD, 2021[2]). Assets in the National Pension Fund even exceed those in the Korean retirement benefit system and voluntary personal pension system (worth USD 560 billion at end‑2020).

Public pension reserve funds such as Korea’s National Pension Fund have some commonalities with private pension funds. Public pension reserve funds and private pension funds are all in charge of managing pension assets. The guidelines and principles for efficient regulation and management of private pension funds are relevant for the operation of public pension reserve funds, in particular in terms of governance, investment and risk management. Their missions differ. Public pension reserve funds back a public pension scheme while private pension funds shall manage the assets in the best interests of their members. The ultimate owner of assets also differs. Assets of public pension reserve funds belong to the public institution managing the scheme or the state while assets of private pension funds belong to their members directly (OECD, 2021[1]).

This chapter provides guidelines to assist the National Pension Fund to achieve its mission, based on principles of private pension regulation and, where relevant, on the experience from other public pension reserve funds. To this end, the chapter intends to highlight when governance and investment practices of the National Pension Fund are in line with the OECD Core Principles of Private Pension Regulation (OECD, 2016[3]) and identify when they potentially diverge.

The analysis hereafter shows that the framework of the National Pension Fund is broadly in line with the OECD Core Principles of Private Pension Regulation (OECD, 2016[3]) in terms of governance, investment and risk management policies. The independence of the fund has been bolstered over the years and could be even further guaranteed by limiting the interlinkages between stakeholders designing the investment policy of the fund and the ones validating it. The investment policy of the fund has been targeting an increase in the diversification of the portfolio and more risk taking, which may help to achieve better risk-adjusted returns and further support the financial stability of the national pension scheme, in line with the objective of the fund. The National Pension Fund also takes into account ESG consideration in its investment policy, and it exercises its shareholder rights as the OECD Core Principles of Private Pension Regulation (OECD, 2016[3]) recommend. An active involvement in shareholder meetings can be beneficial to the investment performance of the fund as long as these rights are duly exercised.

4.1. History of Korea’s reserve fund

The National Pension Fund is the reserve fund of the national pension scheme, established in 1988 following the National Pension Act. The National Pension Fund was created to secure financial resources to support the benefit payments of the national pension scheme, in accordance with Article 101 of the National Pension Act. The National Pension Service (NPS) has been in charge of the daily operations of the national pension scheme and the related reserve fund. The management of the reserve fund has been assigned to a Management Committee, initially headed by the Minister of Economy and Finance.

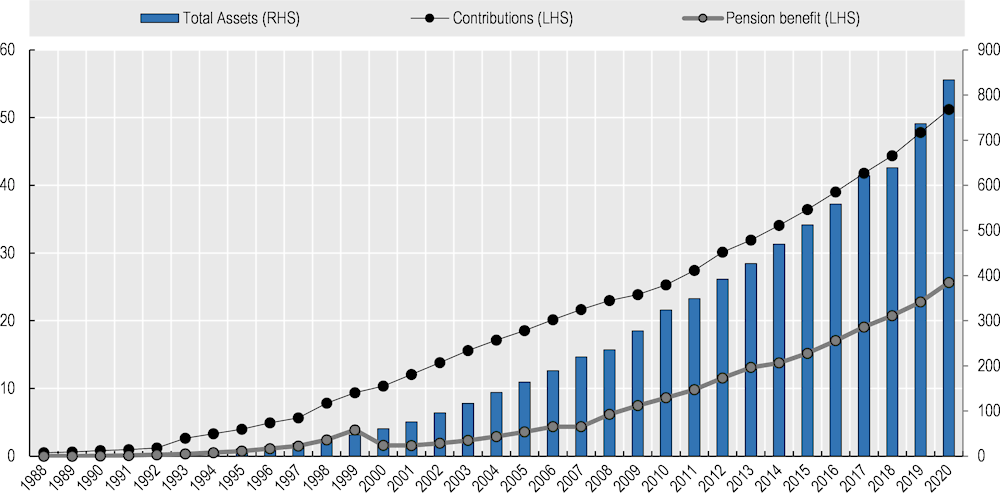

The National Pension Fund has built up assets rapidly over 30 years of operation. It held KRW 834 trillion (or USD 796 billion) at end‑2020 (Figure 4.1). The National Pension Fund has been accumulating assets from two main sources: the surplus of contributions to the national pension scheme – which is now mandatory for all employees, employers and self-employed aged between 18 and 60 – over benefit payments and other expenses of the scheme; and the income earned by investing this surplus.

Figure 4.1. Selected in- and outflows of the national pension scheme and Assets of the National Pension Fund, 1998‑2020

Note: “LHS” means left-hand side; “RHS” means right-hand side.

Source: National authorities and annual reports of National Pension Fund.

Contributions have been growing over the years as the coverage of the national pension scheme has broadened and the contribution rate has risen. The scheme initially covered only those in the workplaces with 10 or more full-time employees, before being extended to workplaces with 5 or more full-time employees in 1992, farmers and fishermen in 1995, urban citizen in 1999 and workplaces with 1 or more employees in 2003. The contribution rate increased from 3% to 6% in 1993, and then 9% in 1998. Benefit payments have also been increasing but not as fast as contributions (Figure 4.1).

The investment income of the National Pension Fund, which is also a driver of its asset growth, was initially mainly coming from earnings from investments in domestic fixed income. Even though the National Pension Fund started to invest in domestic equities in 1990, most of the surplus from the national pension scheme was deposited at the Public Capital Management Fund (PCMF), as mandated in the PCMF Act. This created several concerns (Kim and Stewart, 2011[4]). The investment return of the deposits at the PCMF was lower than the returns of other financial instruments. The growth of assets of the National Pension Fund and deposits at the PCMF was also threatening the ability of the government to pay the interests on these growing deposits. There were also a risk of political arbitrage as the Minister of Economy and Finance was both Chair of the board of the National Pension Fund and the PCMF while these two institutions have different mandates.

The National Pension Act was revised in 1998 to address these issues, impacting the National Pension Fund in several ways. The Minister of Health and Welfare became the Chair of the Management Committee of the National Pension Fund instead of the Ministry of Economy and Finance. The number of members of Management Committee increased and included more non-governmental members to foster the independence of the National Pension Fund. The National Pension Service Investment Management (NPSIM) was also created in 1999 to manage and invest the assets of the National Pension Fund. The revised National Pension Act mandated the Minister of Health and Welfare to appoint the Executive Fund Director of the NPSIM, serving as the CIO.

The PCMF Act was also revised in 1998, phasing out the mandatory deposit of the surplus of the National Pension Fund at the PCMF (65% in 1999, 40% in 2000). The interest rate of the deposits was also amended with the revision of the Enforcement Decree of the National Pension Act. The deposit rate was set to be either the government bond yield or the national housing bond yield, whichever the higher.

The Fund has kept growing and seeking to diversify its investments domestically and abroad. It started investing in venture capital and overseas equities in 2002, domestic real estate in 2004, domestic infrastructure and private equity fund in 2005, foreign real estate in 2006, foreign infrastructure in 2007 (National Pension Service, 2021[5]). It has started to open offices abroad from 2011 to foster foreign investments (in New York in 2011, London in 2012, and Singapore in 2015).

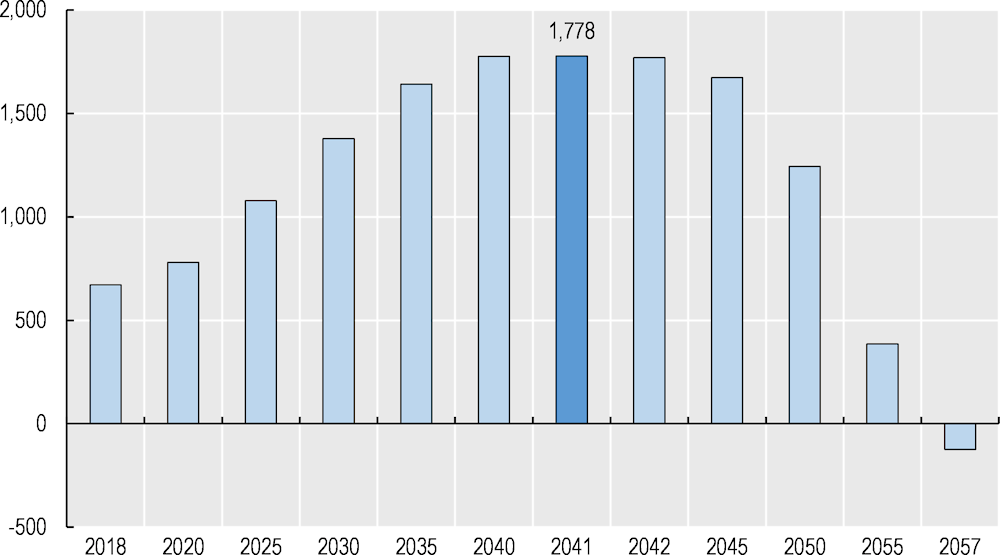

The assets of the National Pension Fund are expected to continue growing over the coming years. The National Pension Research Institute carries out an actuarial projection every five years and provides an outlook of the assets of the National Pension Fund over the next 70 years. The National Pension Research Institute predicted in 2018 that the assets of the fund would increase until 2041, peaking at KRW 1 788 trillion, and then decline until the depletion of the fund in 2057 (Figure 4.2).

Figure 4.2. Fourth actuarial projection of the assets of the National Pension Fund

However, the evolution of the assets of the National Pension Fund may change depending on how the investment rates of return, the contribution levels, pension paid to beneficiaries of the national pension scheme, and the operating expenses of the NPS (among other factors) evolve compared to the assumptions of the National Pension Research Institute. These can be affected by the governance of the fund, the investment policy and risk management.

4.2. Governance of the National Pension Fund

The OECD Core Principles of Private Pension Regulation (OECD, 2016[3]) provide guidelines for the design and operation of private pension systems, which can be relevant for public pension reserve funds (such as Korea’s National Pension Fund). For example, these OECD Core Principles touch upon governance. Good governance is also key for public pension reserve funds. It can help both private pension funds and public pension reserve funds to instil trust among all stakeholders and to achieve their mission.

Table 4.1 summarises the main guidelines of the OECD on governance. These guidelines relate to the identification of the responsibilities in the governance of the funds, the governing body of these funds, its accountability and the suitability of its members, the delegation of tasks, the appointment of independent experts (e.g. auditor, actuary), internal controls and disclosure of the relevant information. These guidelines provide benchmarks to assess where the governance framework of Korea’s National Pension Fund is in line with the OECD’s principle and where it diverges.

Table 4.1. Implementing guidelines of the OECD Core Principle of Private Pension Regulation on governance

|

Implementing Guidelines |

Key features |

|---|---|

|

Identification of responsibilities |

Separation of operational and oversight responsibilities |

|

Governing body |

Creation, role and responsibilities of governing body |

|

Accountability |

To members, supervisor, competent authorities |

|

Suitability |

Membership of governing body |

|

Delegation and expert advice |

Sub-committees of the Board; internal and external expertise |

|

Auditor, actuary and other third-party |

Independence |

|

Risk-based internal controls |

Organisational and administrative controls; codes of conduct; internal reporting systems |

|

Disclosure |

Timely communication of relevant information to all stakeholders |

Source: OECD (2018[6]) (adjusted).

4.2.1. Responsibilities

There is a clear assignment of the oversight and operational responsibilities among the different parties involved in the governance of the National Pension Fund following the OECD Core Principles of Private Pension Regulation (OECD, 2016[3]). The Minister of Health and Welfare oversees the administration and the management of the National Pension Fund while the NPS is in charge of the operational duties.

As part of the responsibilities, the Minister of Health and Welfare develops a plan for the management of the fund, which is presented to different bodies. This plan is reviewed by the governing body of the National Pension Fund and the State Council, before being submitted to the President for approval and then to the National Assembly for final approval.

The Minister of Health and Welfare delegates the operational functions to the NPS. The NPS has to implement the fund management plan that is approved. The NPS has an investment arm, the National Pension Service Investment Management (NPSIM), which is in charge of various investment activities, including investing the assets of the National Pension Fund and monitoring financial markets.

While the different roles are usually clearly separated, there seems to be an overlap between the design of the fund management plan and its review, as the Minister of the Health and Welfare who designs the plan is also the chair of the governing body of the National Pension Fund that reviews this plan.

4.2.2. Governing body

While the governing body of private pension funds would be expected to set out the mission for the fund (OECD Core Principles of Private Pension Regulation (OECD, 2016[3])), the mission of public funds is often established by the state instead (OECD, 2018[6]). This is the case in Korea. The state establishes the mission of Korea’s National Pension Fund in its national law (Article 101 of the National Pension Act). The mission of Korea’s public pension reserve fund is to secure financial resources to support the benefit payments of the national pension scheme.

The governing body of the Korea’s National Pension Fund, which is the National Pension Fund Management Committee (FMC), has the main task of implementing the mission, among other tasks. The FMC assesses and approves decisions relative to the management of the fund. The FMC also decides on matters relating to the risk management of the National Pension Fund, its performance assessment, and compensation for example.

The FMC also determines key policies relating to the exercise of shareholder rights, which can contribute to the successful fulfilment of the mission of the fund. The NPS conducts shareholder engagement in five key areas: the dividend policy of companies it invests in, the remuneration cap for their directors, concerns over violation of law, improvements of the companies after repetitive votes from the NPS against decisions of the companies in the shareholders’ meetings, and results of ESG evaluations. The NPS selects a focus list of companies and can engage in confidential dialogues and shareholder proposals to sort out issues. The OECD Core Principles of Private Pension Regulation (OECD, 2016[3]) acknowledge that the informed and effective use of shareholder rights is a way of seeking value for investments. Active shareholder engagement has therefore the potential to help the National Pension Fund getting better returns for its investments, especially given the size of the fund and the influence it can have in shareholder’s meetings.

The NPS has pursued efforts to mitigate the risk of political interference in the exercise of the shareholder rights, increase transparency and ensure shareholder engagement generates long-term benefits for the National Pension Fund. The NPS adopted Responsible Investment and Governance Principles (also known as the Stewardship Code) in 2018 to enhance independency and transparency of shareholder rights and improve the long-term profitability of the National Pension Fund.1 The NPS proposed a bill in 2020 for a handover of the authority of the FMC on shareholder activities to the lower Special Committee on Responsible Investment and Governance that mostly gathers representatives external to the government..2 This handover would be a way of guaranteeing that the exercise of shareholder rights is carried out at arm’s length of the government and for the long-term benefits of the fund, preventing the risk of indirect undue political interference in the corporate governance of the Korean companies. The National Pension Fund has also been transparent on shareholder activities, publishing these activities in its annual report.

4.2.3. Accountability

The OECD Core Principles of Private Pension Regulation (OECD, 2016[3]) stress the importance of the accountability of the governing body or the fund itself to supervisors and beneficiaries, which is the Korean population ultimately in the case of the National Pension Fund. While the assets of Korea’s fund belong to the national pension scheme, these assets intend to secure the financial stability of the national pension scheme. The ultimate beneficiaries of these assets are therefore expected to the members of the national pension scheme and those that are or will be entitled to payments from it.

The accountability in the management of the fund is guaranteed by the oversight of the President and the National Assembly. The President has to approve the annual fund management plan that the Minister of Health and Welfare prepares and that is reviewed by the FMC and the State Council. The Korean Government then has to submit the plan to the National Assembly by the end of October of the year preceding the one for which the plan will apply. The National Pension Act (Article 107) stipulates that the National Assembly shall receive the details of the operation of the fund and the use of the assets of the National Pension Fund deposited at the Public Capital Management Fund.

The OECD Core Principles of Private Pension Regulation (OECD, 2016[3]) also see the appointment of members and beneficiaries of private pension funds in the governing body as a way of promoting accountability within the board on the management of the assets. The National Pension Fund is in line with this guideline, as its current governing body includes a wide range of different stakeholders, including representatives of employers, employees and self-employed, therefore involving representatives of the Korean population in the administration of the fund.

4.2.4. Suitability

The governing body of the National Pension Fund (i.e. the FMC) has 20 members: the Minister of Health and Welfare as a chair, the CEO of the NPS, 4 Vice Ministers, 12 representatives of employers, employees and individually insured participants of the national pension scheme (e.g. self-employed), and 2 experts.3 The chair of the FMC and each ex officio member remain in the governing body until the term of their tenure as Minister, Vice Minister or CEO. Other members of the FMC hold office for a term of two years and can be reappointed consecutively only once.

Candidates for membership in the governing body who are not governmental officials seem to be subject to some fit and proper standards as the OECD Core Principles of Private Pension Regulation (OECD, 2016[3]) recommend for members of the board of private pension funds. Each representative group of employers, employees and individually insured people recommends potential members to the FMC, who are then appointed by the chair of the FMC. Nominees of each group has to fill out and submit a work ethic examination report. If this report unveils potential conflicts of interest, the application is rejected.

In line with one of the OECD’s implementing guidelines on governance, the Korean legislation lays out criteria that can disqualify an individual from being a member of the FMC. The National Pension Act stipulates that the chair of the FMC can dismiss members of the governing body if they become unfit to fulfil their duty, commit an illegal act (e.g. negligence, reputational damage), or have a conflict of interest. The chair of the FMC can also dismiss members who express their intention to resign.

The FMC gathers a wide range of different stakeholders and representatives, fostering its independence, and seems to have collectively all the skills and knowledge to fulfil its duties as the OECD Core Principles of Private Pension Regulation (OECD, 2016[3]) recommend. The involvement of two experts are one of the means that can ensure the governing body as a whole have all the skills for its mission. These experts can be appointed according to the needs of the FMC. The FMC also acquires expertise through sub-committees established under its umbrella. Three members of the FMC directly sit on two of these sub-committees: the Special Committee on Investment Policy, and the Special Committee on Risk Management and Performance Evaluation & Compensation.

Although the FMC seems to have all the skills collectively to manage the fund, it is important to ensure that all members of the FMC are properly informed and receive the necessary advice to make informed decisions when these are complex, taking into account the various backgrounds and profiles of the members in FMC. According to Yun et al. (2015[7]), the complexity of investments in hedge funds has deterred the FMC to approve the investments in these vehicles earlier.

4.2.5. Delegation and expert advice

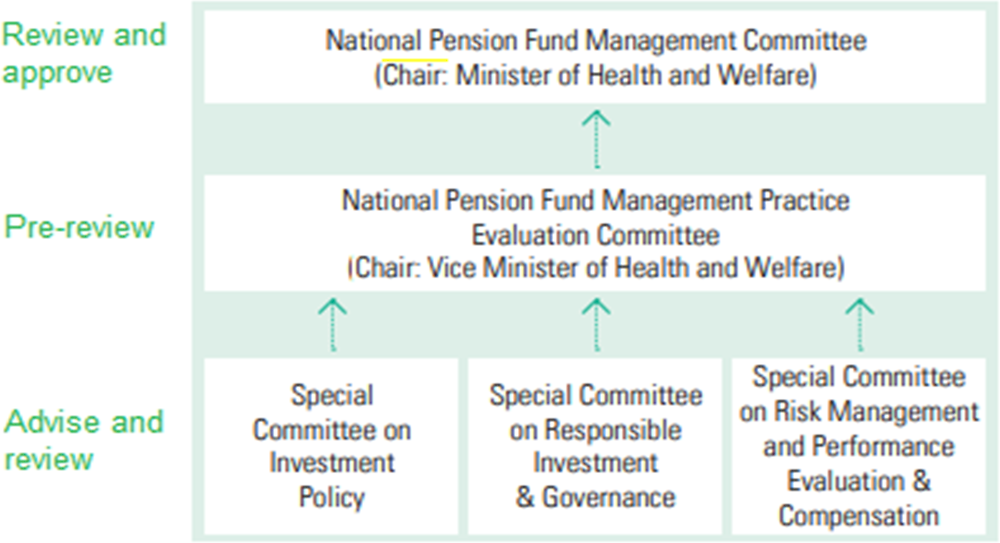

As per the OECD Core Principles of Private Pension Regulation (OECD, 2016[3]), the governing body of the National Pension Fund (i.e. the FMC) can rely on several sub-committees to support its activities (Figure 4.3).

Figure 4.3. Committees and sub-committees supporting the governing body

The FMC is advised by the National Pension Fund Practice Evaluation Committee (PEC). The PEC reviews the agendas submitted to the FMC in advance and offers technical and professional advice on them.4 This sub-committee is chaired by the Vice Minister of Health and Welfare and gathers 5 other ex officio government officials, 12 representatives of the employers, employees and individually insured participants, and 2 external experts. The 12 representatives of employers, employees and individually insured participants are recommended by their relevant professional organisations, and are selected among qualified lawyers, certified public accountants, and individuals majoring or holding a doctorate degree in social welfare, economics or business administration with at least three years of experience in a university, a public or research institute. This selection and nomination process ensures that members have a set of skills that will be useful for the provision of advice to the FMC. All the PEC members serve a term of two years that can be renewed, except the chair and government officials (serving only during their period in office).

The FMC also receives advice and assessments from three special committees:

the Special Committee on Investment Policy: it provides advice on investment policies, carries out reviews and assessments on fund management, investment plans and standards.

the Special Committee on Responsible Investment & Governance: it discusses the execution of shareholder rights in listed companies (pursuant to relevant rules and regulations) and reviews key matters related to responsible investments.

the Special Committee on Risk Management and Performance Evaluation & Compensation: it recommends policies on risk management, performance evaluation to attract and retain talented staff, and assesses performance bonuses for employees of the NPSIM.

The three special committees have nine members overall. They all have three full-time members among their nine members. The Special Committee on Responsible Investment & Governance also has six experts in the relevant fields, while the two other special committees have three members of the FMC and three experts in the relevant field. The chair of each special committee is elected among the full-time members.

The three special committees conduct reviews on the FMC agenda in advance and provide advice. The chair of each special committee attends the FMC meeting to provide an overview and the result of the discussions in the special committees. The FMC is the highest assessment and decision-making body on fund management, making final decisions based on what was discussed in special committees.

4.2.6. Auditor, actuary and other third party

Korea’s National Pension Fund seems compliant with the OECD guidelines for an independent audit and actuarial valuations.

The National Pension Act stipulates that an auditor shall audit the accounts, the status of management of operations and the properties of the NPS (Article 34). Grant Thornton Daejoo, which is a Korean Accounting Firm, recently audited the financial statements of the National Pension Fund, the statements of financial operations, and the statements of changes in net assets. This company carried out its audit in accordance with Korean Standards on Auditing, and independently of the National Pension Fund. The NPS has additionally its own audit division.

The National Pension Act (Article 4) and the Enforcement Decree (Article 11) also stipulate that an actuarial valuation should be performed every five years. This actuarial valuation was introduced alongside the 1998 amendment of the National Pension Act, so as to calculate the long-term financial balance of the national pension scheme. The first actuarial valuation report was released in 2003, the second in 2008, the third in 2013 and the fourth in 2018. The National Pension Research Institute (NPRI) carries out this actuarial projection. These projections involve experts from different organisations to set up the assumptions on the evolution of the population, the labour and financial markets and the broader macroeconomic context, which underpin the results. Statistics Korea provides the results of population projections for example. The Korean Development Institute (KDI) provides assumptions for major economic variables (GDP growth, wage growth, interest rate, consumer price). The NPRI also carries out a sensitivity analysis and examines the impact of different scenarios on the assets of the National Pension Fund.

The National Assembly Budget Office (NABO) recently performed a forecast of assets in the National Pension Fund for the first time. The main differences with the actuarial projection of the NPRI lie in the forecasting method and the assumptions for macroeconomic variables. The NABO used its own macroeconomic variables and tended to have more conservative, pessimistic assumptions than the NPRI. The NABO found the depletion of the reserve fund would occur 3 years before the date the NPRI forecast.

4.2.7. Risk-based internal controls

The OECD Core Principles of Private Pension Regulation (OECD, 2016[3]) advocate for adequate internal controls that ensure that all the parties involved in the fund act in accordance with the objectives in the law and associated documents, both for oversight and for operational activities.

The investment arm of the NPS, the National Pension Service Investment Management (NPSIM), is in charge of the operational aspects of the management of the National Pension Fund and seems to monitor a wide range of risks, as the OECD Core Principles of Private Pension Regulation (OECD, 2016[3]) would expect for private pension funds. The NPSIM controls risks that can affect the stability and profitability of the National Pension Fund, such as market risk, credit risk, liquidity risk, operational risk, and legal risk. The NPSIM has a dedicated risk management division to manage investment risks, a procedure to mitigate operational risks, a Compliance Office (independent from the NPSIM and reporting directly to the CEO of the NPS), and a Risk Management Committee (RMC) to manage all the risks related to the fund management. Several reports on operational risks are prepared regularly: monthly and quarterly reports including internal controls related to legal compliance, and ad-hoc reports on internal controls related to violations. The RMC receives a quarterly report and the CEO of the NPS a monthly one on the company‑wide effort to manage risk.

The NPS is also subject to internal and external audits, from its internal audit team, independent auditors, Board of Audit Inspection and the National Assembly.

The OECD Core Principles of Private Pension Regulation (OECD, 2016[3]) recommend a code of conduct and conflicts-of-interest policy for all parties involved in the operation and oversight of the fund. The full compliance of the National Pension Fund with the adequate internal controls the OECD Core Principles of Private Pension Regulation (OECD, 2016[3]) advocate for depends on the existence of such code‑of-conduct and policy on conflict of interests developed by the governing body of the National Pension Fund.

4.2.8. Disclosure

A detailed set of information on the National Pension Fund is publicly disclosed on a regular basis (Table 4.2), in line with the guidelines in the OECD Core Principles of Private Pension Regulation (OECD, 2016[3]). Key data on the National Pension Fund are available every month, such as assets, investment rate of returns by asset class. More information on specific asset holdings and the investment activities of the NPSIM becomes available on a quarterly basis. The NPS publishes a detailed report on the National Pension Fund every year.

Table 4.2. Public disclosure on the National Pension Fund

|

Frequency |

Content |

|---|---|

|

Monthly |

Revenues, expenses and fund reserves; portfolio status and rate of return by asset class |

|

Quarterly |

List of large equities holdings; fixed income investments by bond type; list of external managers and partner securities firms |

|

Annually |

Statements of financial positions and financial operations; investment portfolios by asset class; investment holdings by asset class; responsible investment status |

|

Occasionally |

FMC meeting results; fund management guideline and fund management plan; fund management regulations and standards on selecting external managers and partner securities firms; voting records of listed stocks and reasons for votes against; other matters deemed necessary to be publicly disclosed in relation to fund management decision |

Source: National Pension Service (2021[5]).

Since the 1998 revision of the National Pension Act, the chair of the governing body of the National Pension Fund (the FMC) also has to report on the FMC meetings. The Chair of the FMC has to make public a summary of the meetings, including the matters discussed and resolved. The Chair of the FMC has to publish the minutes of the FMC meetings one year after the date of the meeting (or after four years if an agenda item could affect the operation of the fund or the financial market stability).

The disclosure of all this information can benefit the National Pension Fund in several ways. The dissemination of information can enable an external audience to carry out performance and policy evaluations. This external review can lead to peer pressure, compensating the lack of competitive pressure (OECD, 2018[6]). Transparency also contributes to build trust from the population.

4.3. Investment and risk management policies of the National Pension Fund

The investment of assets is one of the main activities of any pension fund, public, private or reserve fund, managing assets. This activity enables all these institutions to earn an investment income, providing additional resources to finance expenditure or commitments. It also entails an investment risk that may need to be appropriately managed. Adequate investment and risk management policies are therefore essential for public pension reserve funds and private pension funds to achieve their mission.

One of the OECD Core Principles of Private Pension Regulation (OECD, 2016[3]) focuses on the investment of pension assets and the management of risk, providing guidelines relevant and applicable to public pension reserve funds. Table 4.3 shows a grouping of these guidelines, in the light of which the policy of the National Pension Fund can be looked at. These guidelines refer to the retirement income objectives and prudential standards, the investment policy of the fund, the portfolio limits and other quantitative requirements, the valuation of pension assets and the performance assessment.

Table 4.3. Implementing guidelines of the OECD Core Principle of Private Pension Regulation on investment and risk management

|

Implementing Guidelines |

Key features |

|---|---|

|

Retirement income objective, prudential principles and prudent person standards |

Alignment with retirement income objective; risk management techniques; Prudent person standard, fiduciary duty, requirement to establish investment process with adequate safeguards |

|

Investment policy |

Written policy; clear risk and return objectives appropriate for the characteristics of the fund. Asset allocation strategy with tolerances. Investment options for members. Review procedures. |

|

Portfolio limits and other quantitative requirements |

Definition; respect for diversification and liability matching |

|

Valuation of pension assets |

Transparent basis |

|

Performance assessment |

Monitoring procedure |

Source: OECD (2018[6]) (adjusted).

4.3.1. Retirement income objective, prudential principles and prudent person standards

The National Pension Act defines the mandate of the National Pension Fund. The National Pension Fund intends to secure financial resources for the national pension scheme (Article 101).

The NPS is in charge of managing and investing the resources set aside, through the NPSIM, with the objective of maximising returns and ensuring the long-term stability of the finances of the national pension scheme, as per Article 102 of the National Pension Act.5 The higher the returns are, the more resources will be available to support the national pension scheme, and for longer. The regulation on the management of the assets is consistent with the mandate and income objective of the National Pension Fund, and is there in line with the OECD guidelines.

The NPS also reports that the NPSIM follows a number of prudential principles, as the OECD Core Principles of Private Pension Regulation (OECD, 2016[3]) recommend, such as the profitability of the investments, stability of the assets (with a management within risk tolerance levels), liquidity considerations to ensure the payment of benefits.6 The NPSIM also manages assets considering the impact on the national economy and financial markets, and ESG. The NPSIM focuses on complying with these principles and avoiding jeopardising them for other purposes not relating to its mission.

4.3.2. Investment policy

The National Pension Fund has a written guideline stipulating the investment policy, the objectives of the fund management, the principles, the organisational structure, roles and responsibilities, in line with the OECD Core Principles of Private Pension Regulation (OECD, 2016[3]). This guideline is formulated by the Minister of Health and Welfare, reviewed and approved by the governing body of the National Pension Fund (the FMC). The NPS then executes investments in line with the two investment plans that the FMC has approved: a mid-term (or target) asset allocation plan (with a 5‑year horizon) and an annual asset allocation plan (with a 1‑year horizon).

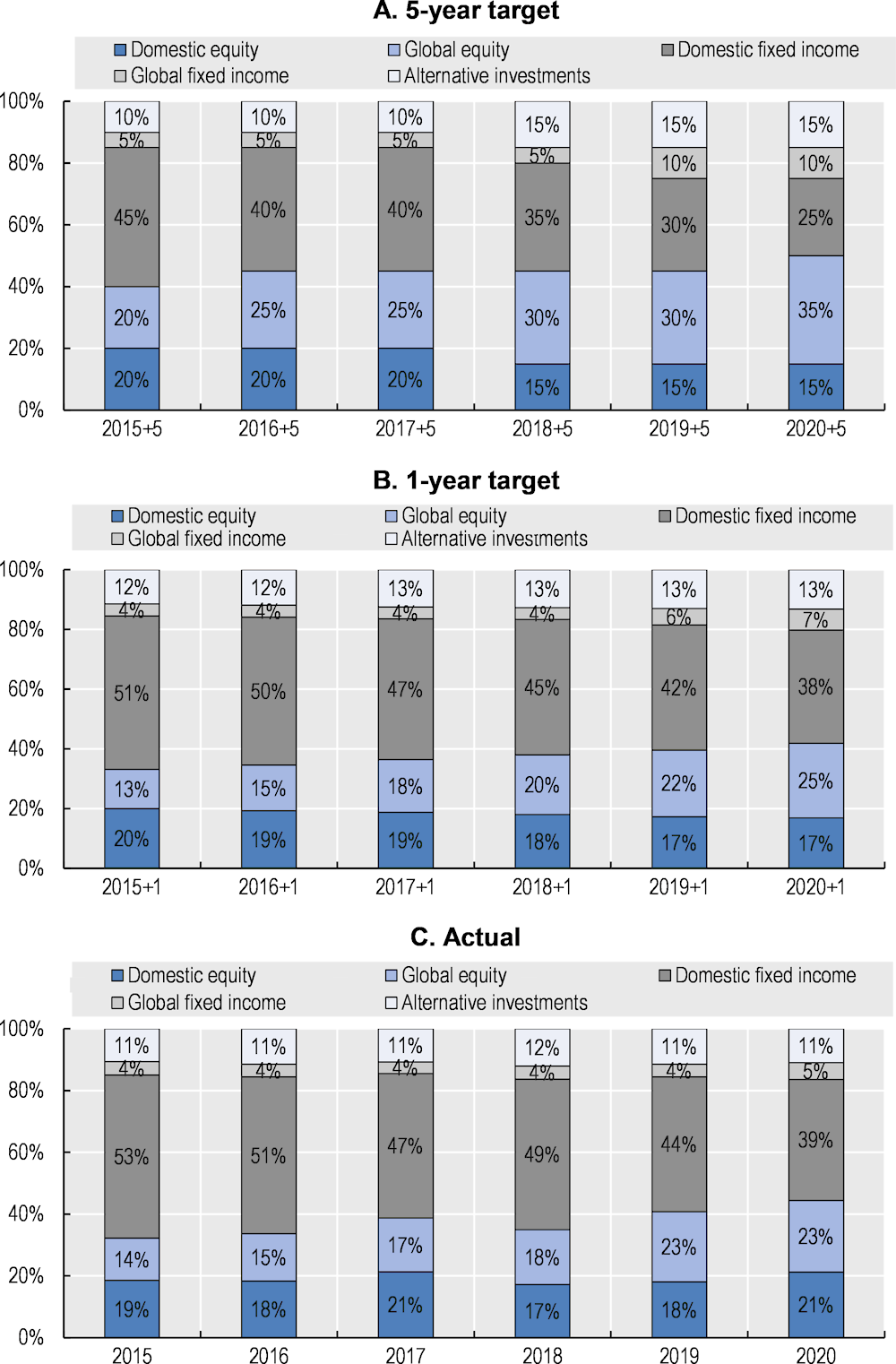

The mid-term (or target) asset allocation plan is a reference portfolio for the next five years, with a performance objective and tolerance for deviation, as the OECD Core Principles of Private Pension Regulation (OECD, 2016[3]) recommend. The FMC sets out an overall 5‑year target rate of return and the risk tolerance level for the next five years, taking into account the outlook for the real economy and financial markets among other factors. The target rate of return is a relative rate, defined as: Real GDP growth rate + CPI rate +/- adjustments. As an example, the target return that was calculated in 2020 for the period 2021 to 2025 was set at 5.2%. The risk tolerance is set so that the probability is less than 15% that the 5‑year cumulative investment return is lower than the cumulative inflation rate over the same period. The FMC then draws up a target asset allocation for each asset class to achieve this performance. It derives an optimal asset allocation given the expected returns and risks for each asset class, the correlation among asset classes and external factors (such as regulatory framework).7 This mid-term asset allocation plan is updated every year. The mid-term asset allocation plan of 2020 for 2025 was an allocation of 15% of assets for domestic equity, 35% for global equity, 25% for domestic fixed income, 10% for global fixed income and 15% for alternative investments by 2025.

The annual asset allocation plan is an annual target portfolio. This mid-term portfolio indicates the target asset allocation to be achieved in stages throughout the following five years. In theory, once the mid-term asset allocation plan (reference portfolio) sets the target allocation ratios for each asset class, the existing portfolio should be rebalanced instantly. As this is not possible in practice, annual target portfolios are built to achieve the mid-term plan. The annual asset allocation plan proposes a target asset allocation by asset class and the permissible range for deviation, taking into account domestic and international investment conditions. The target portfolio in 2020 for 2021 was: 16.8% for domestic equity, 25.1% for global equity, 37.9% for domestic fixed income, 7.0% for global fixed income and 13.2% for alternative investments.

The NPSIM is in charge of executing the investments following the guidelines that the FMC approved. The NPSIM establishes monthly investment plans. These plans are reviewed and approved by its internal Investment Committee.

The target asset allocation of the National Pension Fund (5‑ and 1‑year) has been aiming for a larger diversification over the years and for investments in asset classes that could bring higher returns (Figure 4.4). The target allocation to equities and alternative investments has been increasing while the target for fixed income securities has been declining. The target for foreign investments has also been on the rise. These targets have led to an actual increased diversification of the portfolio of the National Pension Fund, and a diversification of the risks across asset classes and locations. This approach is consistent with the mandate of the National Pension Fund, which is to maximise the returns, and therefore with the OECD Core Principles of Private Pension Regulation (OECD, 2016[3]). The increased diversification of the investments, including geographically, also provides a larger range of options, including outside the domestic market, for the National Pension Fund that continues to grow.

Figure 4.4. Evolution of the target and actual asset allocation of the National Pension Fund

Note: The x-axis shows the year the asset allocation, actual or target, refers to. For instance, “2 015+5” means the 5‑year target asset allocation was set in 2015 for 2020. The asset allocation excludes short-term assets, investment in welfare and other investments (e.g. company buildings, deposits), accounting for a minor share of the portfolio of the National Pension Fund.

Source: Annual Reports of the National Pension Fund.

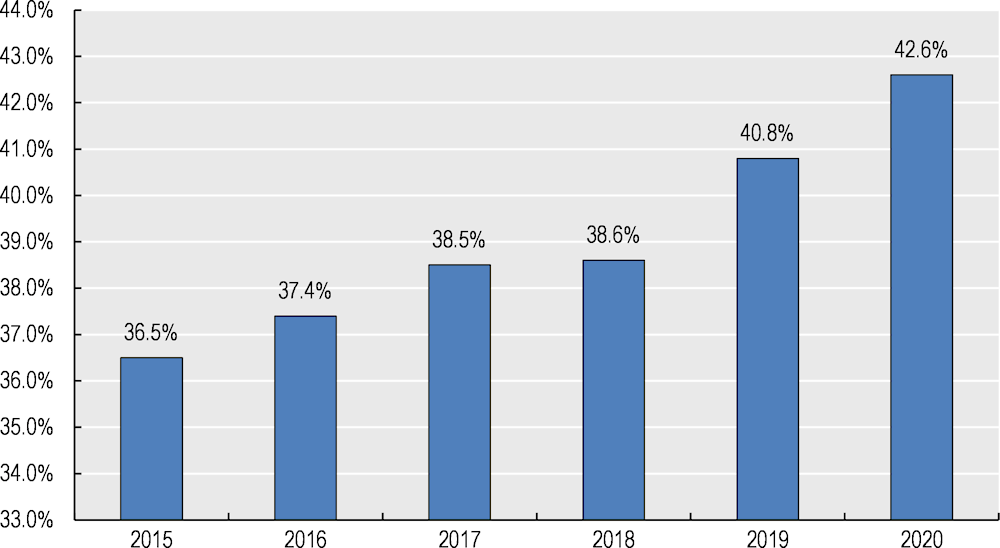

The NPS has been expanded its expertise as it started investing in new and more complex instruments domestically and abroad. The NPS has created new positions and recruited experts to have the capacity to build in-house preliminary risk assessment. It has been also relying more on external experts (Figure 4.5). The NPS has sought opportunities in alternative investments by forming strategic alliances with global asset managers and major funds from other countries. As an example, the Fund has been involved in partnership with the Dutch pension fund APG and the Allianz Group (which head office is in Germany). The NPS has created and expanded its overseas offices (in New York, London and Singapore) to bolster its foreign investments. This capacity building can support the NPS in its new operations. An attractive remuneration policy of internal staff is also important to ensure the NPS can recruit and retain talented investment experts in its team, and potentially offset the increased turnover since the relocation of the NPS to Jeonju (approximately 3‑hour away from Seoul) in 2017.8

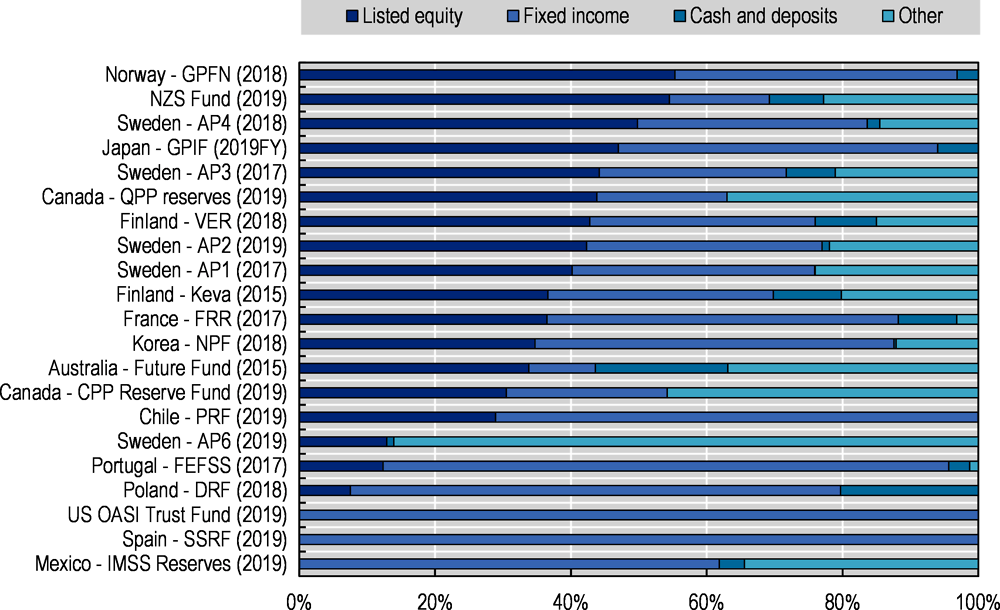

Figure 4.5. Proportion of assets of the National Pension Fund invested in the financial sector outsourced for external managers

The exposure of the National Pension Fund to assets with potentially higher return potential such as listed equities remains lower than other reserve funds, such as those in Canada, Japan, Northern Europe and New Zealand (Figure 4.6). The New Zealand Superannuation Fund (NZS Fund) and the government Pension Fund Norway (GPFN) are the two reserve funds with the largest proportion of assets in equities, exceeding 50% of their assets. However, investments in equities by Korea’s National Pension Fund would only reach 50% of its assets by 2025 according the 5‑year target asset allocation set in 2020.

Figure 4.6. Asset allocation of selected reserve funds, latest year available

Note: The year is given in brackets. Negative values have been excluded from the calculations of the asset allocation. In the United Kingdom, the surplus is loaned to the government through the debt management office through call notice deposits. Reserves are invested in two types of bonds in Israel: fixed-interest rate bonds and variable‑rate bonds.

Source: OECD (2021[1]).

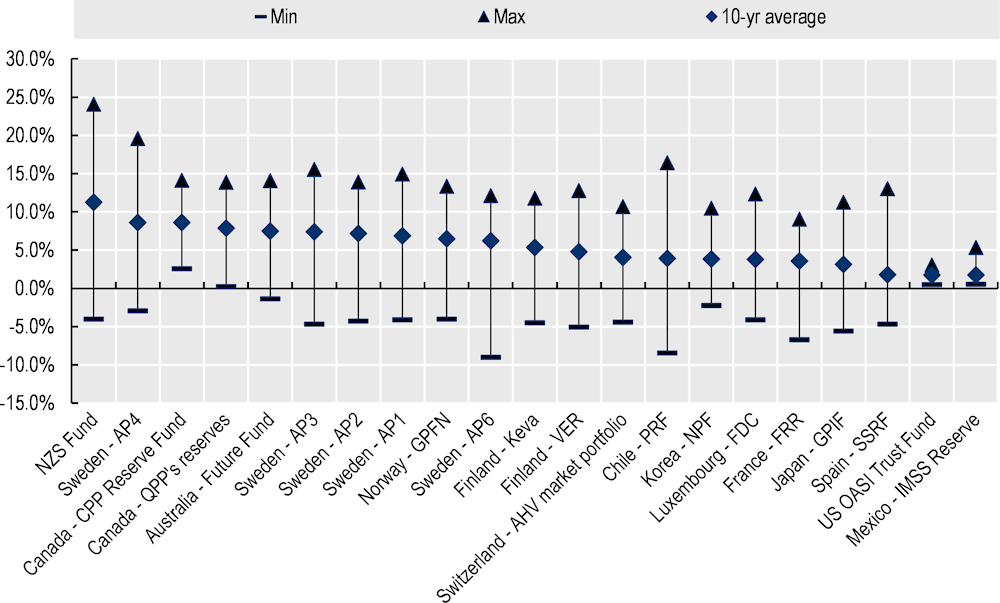

As a result, the investment performance of Korea’s National Pension Fund has not been as high, over a 10‑year period, as other reserve funds with a higher equity exposure (Figure 4.7). Korea’s National Pension Fund recorded an average annual return of 3.8% in real terms between December 2009 and December 2019, while the NZS Fund recorded a double digit performance over the same period (11.3%). While Korea’s reserve fund has not experienced an investment return as low in a given year as some other reserve funds taking more risks, the nature of the reserve fund allows to take on investment risks. Reserve funds such as the one in Korea have a long-term objective and therefore a relative long-term horizon and no short-term commitments towards specific members. Investments in riskier assets now can bring a higher investment performance over the long run and enable the National Pension Fund to benefit from compound interests.

Figure 4.7. Range of annual real investment rates of return of selected reserve funds over 10 years (between Dec 2009 and Dec 2019)

The FMC seems to be set to increase the exposure of assets to classes with higher return potential (such as equities). The FMC was even considering implementing a 10‑year target plan to achieve this.9 This idea behind a 10‑year target was to have a more long-term perspective on the investment strategy. The strategy would be to invest the assets of the National Pension Fund in riskier instruments while reserves of the Fund continue to increase, and start reducing exposure and divest from risky assets when assets will be withdrawn to support payments to retirees of the national pension scheme (from 2041 according the latest actuarial assumptions). This approach looks similar to a life‑cycle strategy for defined contribution plans at an individual level when they draw on their savings to receive benefits during retirement. While having a long-term horizon is a useful perspective to maximise the investment income over the life course, the increase in risk-taking may need to be accelerated and achieved earlier than in ten years. The FMC may also wish to consider an investment strategy for the overall lifetime of the fund, as would life‑cycle strategies do. This strategy over the whole lifetime of the fund could help to maximise the investment income the reserve fund could get overall, and anticipate the “decumulation phase” where the national pension scheme will need to tap into the assets of the reserve fund and the Fund will have less time to recover potential losses in case of shocks in financial markets. This strategy would also enable to anticipate the impact the selling of assets of the reserve fund may have on financial markets in advance.

The NPS has also been incorporating ESG investments in its investment decision making as the Korean legislation has allowed. The NPS joined the Principles for Responsible Investment (PRI) in 2009. The amendment of the National Pension Act in January 2015 put in place a legal basis to incorporate ESG factors into investment decisions. The NPS has adopted ESG integration strategies towards some internally actively managed domestic equities since 2017. The NPS expanded its strategies to passive investments in November 2020 and developed a guideline on ESG integration strategies for domestic equities. Portfolio managers in-house consider ESG-related information when considering new securities. Portfolio managers are required to provide their opinion in writing and ESG reports as attachment of a security review report if the ESG rating falls into low categories. The NPS has also been requiring external responsible investment manager to submit responsible investment fund management report since November 2020. Going forward, the Chairman and CEO of the NPS pledged to take the lead in ESG investing.10 The NPS has decided to increase responsible investments to more than 50% of its assets by 2022. The Fund also intends to integrate ESG factors into its financial analysis of bonds.

The NPS has put in place an investment risk management process as part of its comprehensive risk management, as the OECD Core Principles of Private Pension Regulation (OECD, 2016[3]) recommend. The NPS manages and controls risks impacting the stability and profitability of the NPF, such as market risk and credit risk. The NPS monitors the levels of risk tolerance for each asset class and in total, set annually according to the asset allocation plan. The NPS also has a threat index that it developed in 2010 in the wake of the financial crisis, to assess how to react to financial market volatility.11 It runs an emergency response team when the index surpasses 60, as part of its contingency plan. The threat is considered as grave when the index reaches 80. The emergency response team carries out real-time market monitoring, examines risk factors and prepares response measures for specific assets and the whole portfolio.

4.3.3. Portfolio limits and other quantitative requirements

The current legal setting on the investments of the National Pension Fund seems in line with the OECD Core Principles of Private Pension Regulation (OECD, 2016[3]). The national legislation does not mandate the National Pension Fund to hold a minimum share of its assets in any specific asset class, and does not specifically constraint the asset allocation of the National Pension Fund that would prevent it from achieving its objective.

4.3.4. Portfolio valuation

The valuation of assets of the National Pension Fund seems consistent with the OECD Core Principles of Private Pension Regulation (OECD, 2016[3]).The financial statements of the National Pension Fund have to be prepared and presented in accordance with the Korean National Accounting Standards. An external and independent auditor confirmed the financial statements complied with these standards (National Pension Service, 2021[5]). The NPS also clarifies the valuation method in its annual report where necessary. For example, the NPS specifies that it relied on external independent valuation companies to evaluate the fair value for equity securities with unavailable market quotations.

4.3.5. Performance assessment

The performance of the National Pension Fund is assessed regularly, in line with the OECD Core Principles of Private Pension Regulation (OECD, 2016[3]). A performance evaluation report is prepared every year by the National Pension Research Institute (NPRI) and an independent performance consultant (appointed by the Ministry of Health and Welfare). The evaluation is based on quantitative factors such as benchmark rates – in line with the OECD Core Principles of Private Pension Regulation (OECD, 2016[3]) – and qualitative factors such as the improvement of the fund management system and risk management practices. Benchmarks are set using market indices representing each asset class as references.12 The results from the NPRI and the independent consultant are submitted to the Special Committee on Performance Evaluation and Compensation for review. This Committee then reports to the Practice Evaluation Committee for assessment. The investment performance report that has been developed is finally reported to the governing body of the National Pension Fund for review and approval. The report is finalised in June of the following year. The performance assessment is implemented in compliance with the (internationally accepted standards of) Global Investment Performance Standards.

4.4. Concluding remarks and policy recommendations

The National Pension Fund has grown fast since the Korean authorities started to save excess of contributions over benefit payments at an early stage of the implementation of its public pension scheme, the national pension scheme. The National Pension Fund has become in 30 years one of the largest reserve funds worldwide, with assets close to USD 800 billion at the end of 2020.

As it grew, the National Pension Fund has managed to overcome some of the initial challenges and obstacles that could have thwarted its mission to maximise returns to secure the financial stability of the national pension scheme. It has put in place safeguards to ensure the fund operates at arm’s length of the government and to minimise the risk of political interference that could reduce the investment performance of the fund. More seats in the governing body of the National Pension Fund have been granted to non-governmental stakeholders, such as employees and employers, and external experts.

The National Pension Fund has also further diversified its investment strategy over the years, purchasing assets with a higher return potential domestically and abroad managing the risk adequately. This is in line with its mandate and can be a way of finding new investment opportunities while the size of the fund continues to grow.

The National Pension Fund is currently broadly in line with the OECD Core Principles of Private Pension Regulation (OECD, 2016[3]) developed for private pension funds and that can be applicable to public pension reserve funds. The governance structure of the National Pension Fund clearly identifies the oversight and operational responsibilities. The governing body has a clear mandate, with some fit-and-proper requirements for its members, and benefits from the advice of several sub-committees with the appropriate skills. The submission of the management plan to the National Assembly contributes both to the transparency of the plan and the accountability of the stakeholders involved in the management of the fund, even though the National Assembly seems mainly consulted and the process is unclear in the case where the National Assembly would have any objection or comment on the strategy. The National Pension Fund also engages actively in stewardship activities as the OECD recommends. The investment operations are delegated to the National Pension Service that has proper procedures, risk-based controls, and is regularly assessed by internal and external reviewers, ensuring it delivers according to its objective and mandate.

This analysis has, however, identified a few recommendations that could be helpful for the National Pension Fund to continue to fulfil its mission and align even further with the OECD Core Principles of Private Pension Regulation (OECD, 2016[3]):

Separate further the parties involved in the design of the management plan of the fund and those reviewing it. The Ministry of Health and Welfare is currently involved in both the design of the plan and its validation. A further segregation of the roles would guarantee a more external review of the plan.

Continue to exercise shareholder rights in the best interest of members and beneficiaries of the national pension scheme. This could be achieved by delegating this activity to experts external to the government. Safeguards could further instil confidence and trust that the shareholder rights are duly exercised to maximise the investment performance of assets in the National Pension Fund.

Ensure the governing body of the National Pension Fund receives the necessary and appropriate information when it needs to make decisions on complex matters. This information needs to take into account the various backgrounds and profiles of the members of the governing body.

Ensure the remuneration policy is attractive enough to recruit and retain talented staff involved in the management of the National Pension Fund. This policy should be in line with the strategy of the NPS in terms of turnover, taking into account the mission it has to fulfil ultimately.

Continue to harness the most from financial markets and get the best risk-adjusted return to allow the fund to contribute the financial stability of the national pension scheme. The National Pension Fund may consider taking on more risks sooner and take advantage of the relative long horizon it has to recover potential losses it could incur in the equity markets, to earn higher returns in the long run. This could help the National Pension Fund to achieve higher returns as reserve funds in other jurisdictions record.

Develop an investment strategy for the whole lifetime of the National Pension Fund as life‑cycle strategies would typically do for individuals, in a view to maximising the overall investment income that the National Pension Fund could earn during its life course. It would also help to anticipate potential challenges and implications on financial markets and the economy when assets are drawn from the National Pension Fund to support the payments of benefits of the national pension scheme.

References

[4] Kim, W. and F. Stewart (2011), Reform on Pension Fund Governance and Management: The 1998 Reform of Korea National Pension Fund, OECD Publishing.

[5] National Pension Service (2021), 2020 National Pension Fund Annual Report.

[1] OECD (2021), Pension Markets in Focus 2021, https://www.oecd.org/finance/private-pensions/pensionmarketsinfocus.htm.

[2] OECD (2021), Pensions at a Glance 2021: OECD and G20 Indicators, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/ca401ebd-en.

[6] OECD (2018), OECD Pensions Outlook 2018, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/pens_outlook-2018-en.

[3] OECD (2016), OECD Core Principles of Private Pension Regulation, https://www.oecd.org/finance/principles-private-pension-regulation.htm.

[7] Yun, H., D. Kim and J. Kim (2015), The Need to Set a Fiscal Target and Improve the Fund Governance Structure of the National Pension in Korea.

Notes

← 1. The Stewardship Code is a code of seven principles on the stewardship responsibility of institutional investors. These principles include for example the establishment and disclosure of a clear fiduciary responsibility, of an effective and clear policy on conflicts of interests, of a voting policy and voting records. Around 150 companies, including the National Pension Service, had adopted the code in 2021. See JIPYONG LLC.

← 2. NPS plan on shareholder derivative action draws strong protest from business - 매일경제 영문뉴스 펄스(Pulse) (pulsenews.co.kr)

← 3. The four vice ministers are from the following ministries: Strategy and Finance; Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs; Trade, Industry and Energy; and Employment and Labour.

← 6. Investment Policy > Investment Principles - National Pension Service Investment Management (nps.or.kr)

← 7. See NPS (2021[5]) and Operating Policy > Asset Allocation Policy > Medium-Term Asset Allocation - NPS National Pension Fund Management Headquarters (in Korean)

← 12. Benchmark indices are used for each asset class to guide investments and assess performance. These indices are reviewed annually and can be changed when appropriate when appropriate if the FMC approves it.