This chapter discusses the problem of low coverage and low levels of expected pensions in the Peruvian pension system. It focuses on their main drivers, namely the problem of high informality in the labour market, the low contribution densities and the possibility of early withdrawals and taking lump sums from the private system. The chapter ends with policy options to improve pension coverage and the level of benefits the pension system provides.1*

OECD Reviews of Pension Systems: Peru

Chapter 5. Improving the coverage and level of pensions

Abstract

The coverage of the pension system in Peru and the level of benefits that it ultimately provides to pensioners needs to improve. This dual problem of coverage of the pension system and low pensions is the result of several drivers. High levels of informality lead to low rates of coverage. High rates of transitions between formal and informal employment lead to less frequent contributions. Finally, low levels of mandatory contributions and the lax rules to withdraw retirement savings before the legal retirement age lead to low pension levels.

The high level of informality in Peru’s labour market is one of the main challenges that the Peruvian pension system faces with respect to the coverage of the system and the adequacy of benefits. Only formally salaried workers are required to contribute to the system. Moreover, high rates of transition between formal and informal employment mean that individuals make less frequent contributions (i.e. they have low contribution densities). As a result, most Peruvians do not contribute to the system throughout their entire career.

To compound the problem, the level of contributions required for formally employed workers is low by international standards, limiting the level of adequacy of benefits that the pension system can provide even for those contributing a full career.

The design of the SPP system encourages the withdrawal of retirement savings before the legal retirement age, further reducing the amount of assets that individuals accumulate to finance retirement. Peruvians can withdraw assets early for the purchase of a first home, and several pathways to early retirement exist. This means that Peruvians will have a lower level of assets accumulated at retirement that will have to finance a longer period of time than if they had saved until the legal retirement age of 65.

Women are less likely than men to have an adequate pension from the existing system. Women have higher levels of informality, lower ages allowed for early retirement and higher life expectancies than men.

In order to improve the coverage of the pension system and the level of pension benefits that it can provide, its design must address the challenges presented by the high levels of informality and the early exit from the pension system before the legal retirement age. Coverage of informal workers needs to increase, either through the promotion of formal employment or through the promotion of contributions to the system by informal workers. Measures to increase the level and density of contributions for all members also need to be put in place. Options to withdraw from the pension system before the legal retirement age need to be limited to allow time for individuals to accrue sufficient pension benefits to finance the whole of their retirement, particularly for women who can retire earlier yet can expect to live longer than men.

5.1. Coverage of the contributory pension system

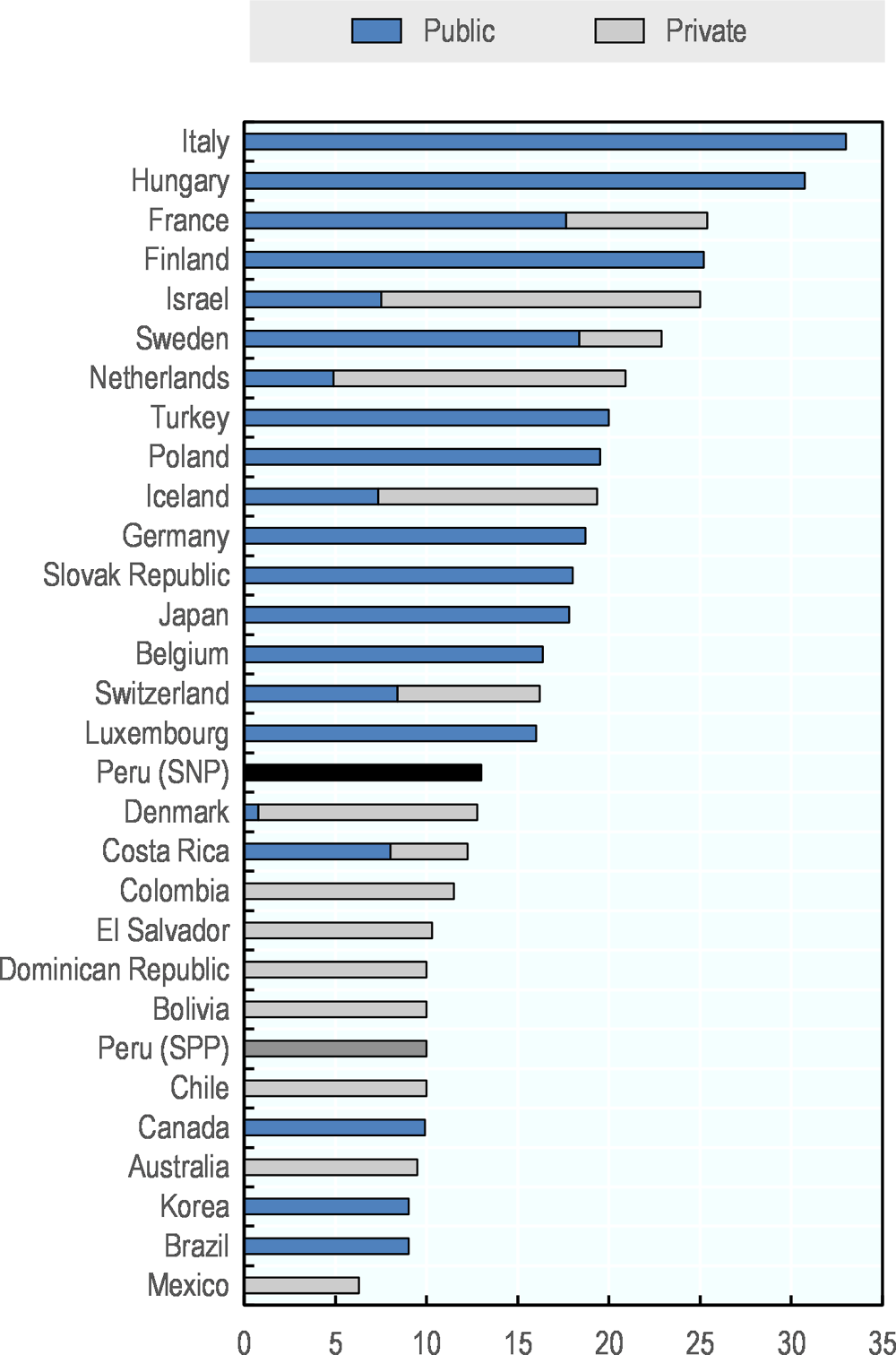

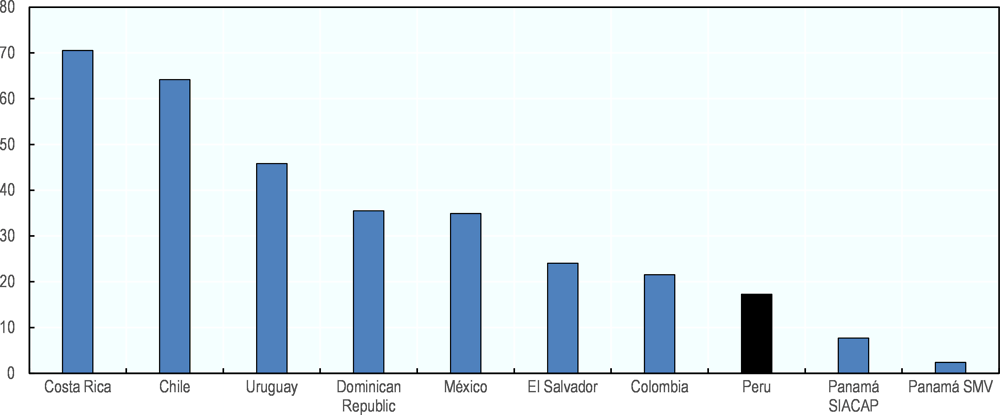

The number of economically active people who have contributed to either the public or private systems remains low by international standards. Figure 5.1 shows that even when accounting for both the public and private systems, Peru has lower coverage than most other OECD countries with mandatory or quasi-mandatory funded pensions. This low coverage is driven primarily by high levels of informality in the labour market given that rates of voluntary affiliation to the pension system by informal workers are low. High levels of informality penalise in particular females, those with less education and those living in rural areas.

Figure 5.1. Coverage of mandatory or quasi-mandatory funded pension plans, 2016

Note: The coverage for Peru includes both the public and private system because members of the SNP can move to the SPP without possibility of returning to the SNP.

Source: (OECD, 2017[3]), SBS, ONP, INEI.

This section first looks at the coverage of the pension system, assessing the number of affiliates to both the private pension system (SPP) and the public pension system (SNP) and their main characteristics. It shows that only around two-thirds of the economically active population are covered by either pension system, and that voluntarily joining the SPP is rare. The section then discusses the challenges related to the high levels of informality in the labour market, particularly with respect to making sure that disadvantaged populations are covered by the pension system.

5.1.1. Affiliation with the pension system

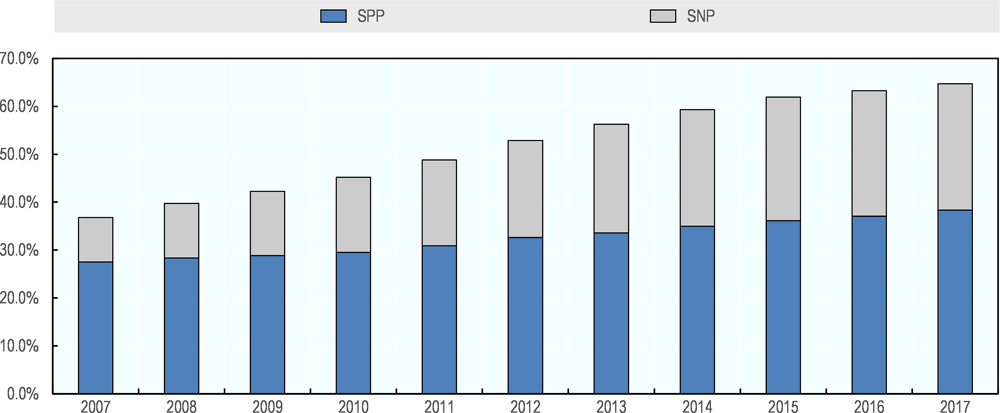

The number of Peruvians covered by the pension system has been steadily increasing over the last decade, with 65% of the economically active population (PEA) covered at the end of 2017 (Figure 5.2). The majority of these individuals are affiliated with the private system, which covered 38.4% of the PEA, compared to 26.4% covered by the public system. However, over the last decade the number of affiliates to the public system has been growing more rapidly than that of the private system.

Figure 5.2. Affiliates as a proportion of the economically active population (PEA)

Source: INEI, SBS, ONP.

Participation in the contributory system (SNP or SPP) is only mandatory for formally employed workers. Although the pension reform in 2012 extended the requirement to contribute to self-employed workers born after August 1, 1973, this was reversed in 2014 shortly after its implementation, and all contributions were refunded.

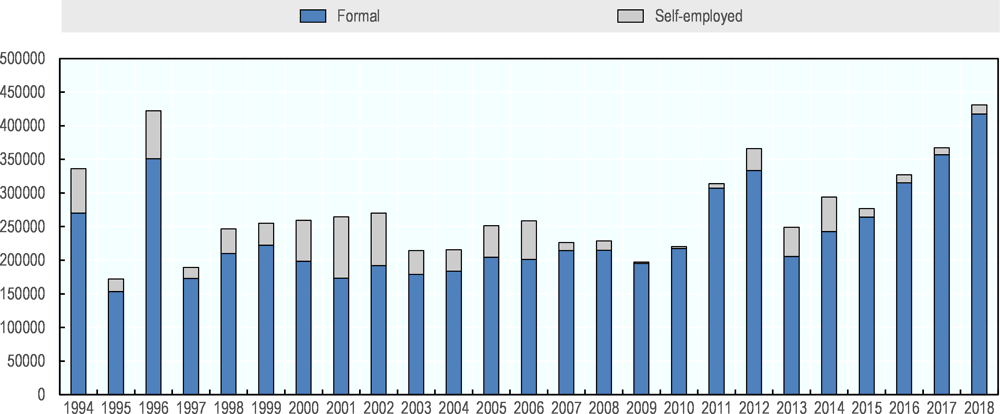

Overall, the number of self-employed who join the SPP voluntarily is significantly less than the number of formally employed workers who are required to contribute to the pension system, although the proportions vary widely from one year to the next. Figure 5.3 shows that through 2006, self-employed workers made up around 20% of the new affiliates on average. Voluntary affiliation peaked in 2001, when a third of new affiliates to the SPP were self-employed workers. Since 2007, the proportion of new affiliates that are self-employed workers has not exceeded 6%, apart from 2012-2014 when law requiring that they contribute came into effect.

Figure 5.3. New affiliates to the SPP by type of worker

Source: SBS.

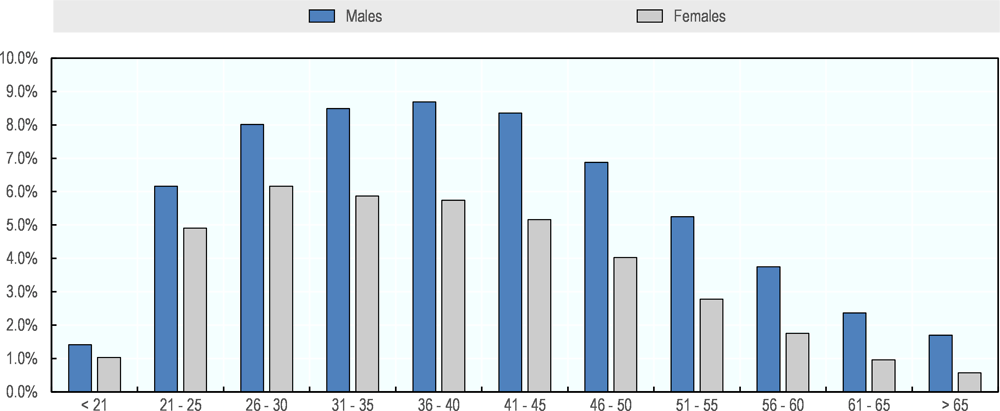

Most affiliates to the SPP are prime age workers. Nearly 60% of affiliates in the private system are between the ages of 26 and 45, with the youngest and oldest ages making up a much smaller proportion of members (Figure 5.4). Individuals over the age of 60 make up only 5.6% of total affiliates.

Figure 5.4. Distribution of SPP affiliates by age and gender

Source: SBS.

Females are less likely to be affiliated with the SPP than males. Females make up just under 40% of total affiliates, and make up a higher proportion of younger affiliates than older affiliates. Around 44% of all affiliates aged 30 and under are female, but this proportion decreases with age and females make up less than 30% of affiliates over the age of 60.

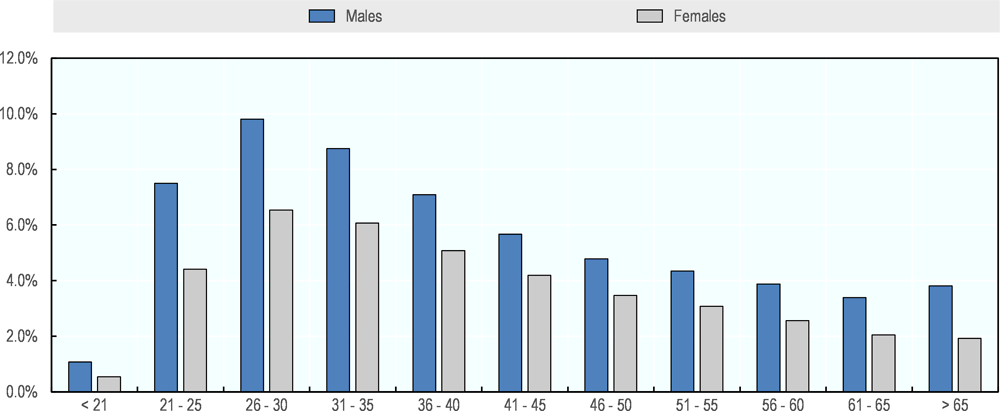

For the public SNP system 53% of affiliates are between the ages of 26 and 45, with the youngest and oldest ages making up a much smaller proportion of members. Individuals over the age of 60 make up only 6% of total affiliates, and those under age 21 account for under 2% (Figure 5.5).

Figure 5.5. Distribution of SNP contributors affiliates by age and gender, 2017

Note: Number of contributors affiliates with complete information of date of birthday and gender.

Source: ONP.

Females are less likely to be affiliated to the SNP than males. Females make up 39.9% of total affiliates, with very little variation by age, ranging from 34% of those aged either under 21 or over 65 to 42% of those aged 41 to 50.

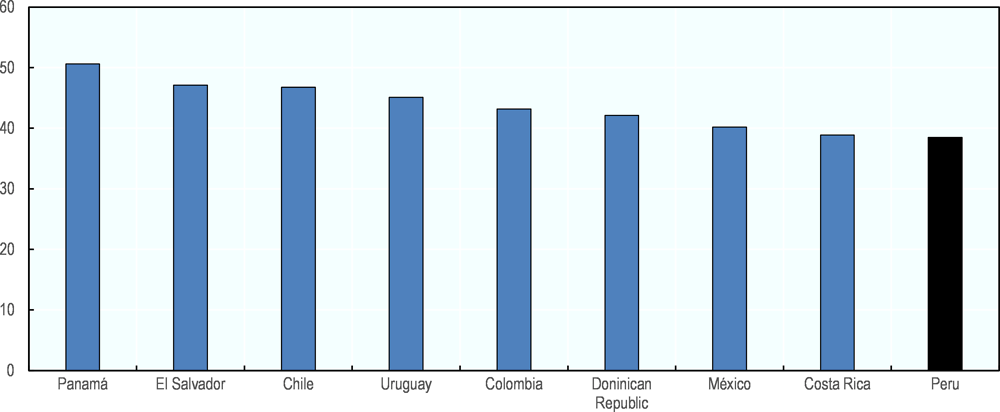

Peru has the lowest proportion of female affiliates for the selected Latin American countries (Figure 5.6). Apart from Costa Rica, females make up at least 40% of pension affiliates in the other countries shown.

Figure 5.6. Proportion of private pension affiliates that are female, December 2017

Source: Asociación Internacional de Organismos de Supervisión de Fondos de Pensiones, AIOS, Statistical bulletin, 2018.

5.1.2. Labour market and informality

Labour markets in Peru have a large share of the working-age population that is either inactive, unemployed or working in informal jobs. As much as 27.6% of the working-age population was inactive in 2017, with particular incidence among women (64% activity rate vs 81% for men). Among the active population, 5% were unemployed and 72.5% of those employed were informal. This leaves only a small share of the population working in formal jobs (INEI, 2018[1]). However, the definition of informal jobs in Peru, as in many other Latin American countries, includes all those jobs in which there is not a requirement to contribute to pensions, for example, all the self-employed and independent workers.

The main weakness of Peru’s labour market is the large presence of informal jobs, which represents a challenge for the functioning of the pension system. Informal employment includes all jobs which are “not subject to national labour legislation, income taxation, social protection or entitlement to certain employment benefits (advance notice of dismissal, severance pay, paid annual or sick leave, etc.)”. According to the definition provided by Peru’s National Institute of Statistics (INEI), this includes “unregistered employees who do not have explicit, written contracts or are not subject to labour legislation, workers who do not benefit from paid annual or sick leave or social security and pension schemes, most paid domestic workers employed by households and most casual, short term and seasonal workers” (INEI, 2014[2]). In this respect, by definition informal workers will not have compulsory contributions to the pension system.

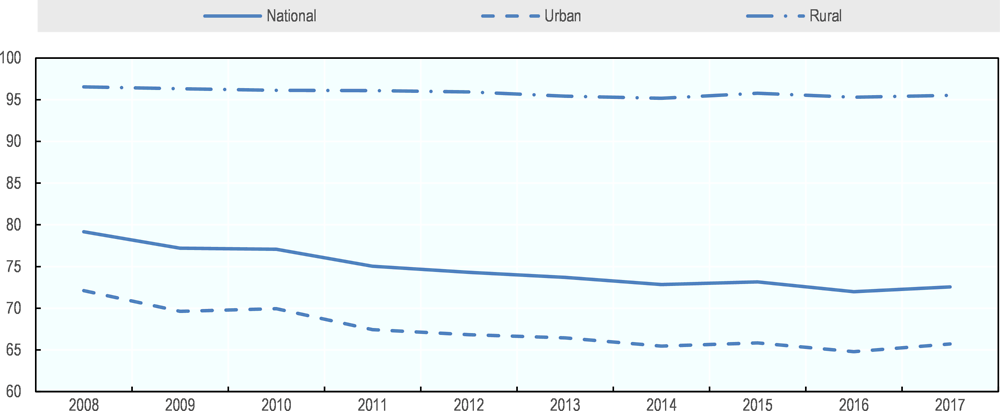

Labour informality has remained high and stagnant in Peru, even across periods of significant economic growth. Between 2008 and 2017, labour informality fell from 79.2% to 72.5% (Figure 5.7). While this is a relevant decline, it shows that informality is a persistent issue that still affects a majority of workers. Furthermore, most of the decline has taken place in urban areas, where it fell from 72.1% in 2008 to 65.7% in 2017. The level of informality remains larger and practically unchanged in rural areas, where it stood at a level of 95.5% in 2017 (96.5% in 2008).2

Figure 5.7. Evolution of labour informality in Peru (2008-2017)

Note: Labour informality is defined following INEI’s definition.

Source: Own elaboration based on (INEI, 2018[12]).

Formal workers are much more likely to have contributed to the pension system than informal workers, who are more likely to be low-income. While only 16% of informal workers are affiliated to the pension system, 83% of formal workers are affiliated. Peru has attempted to extend this to self-employed workers with the Law 29903 that made pension affiliation and contributions compulsory for a subset of independent workers (in particular professional service providers). However, the policy was reversed only months after its implementation. Self-employment is large in Peru, and only 14% of self-employed workers were affiliated to a pension system in 2015. Extending pension coverage to independent workers is thus a major pending challenge (OECD, 2016[3]).

The frequent transitions between formality, informality, and inactivity is an important additional problem as these generate significant gaps in workers’ contributions to the pension system. Contribution densities are low as a result. Workers move between formal and informal jobs and also between salaried jobs and self-employment, and hence it is not accurate to label workers as being ‘formal’ or ‘informal’, as they may change their labour market status various times across their working trajectory. Over the two-year period from 2013 to 2015, 21% of formal workers changed status and moved into inactivity (3%), unemployment (3%), self-employment (7%), or directly into informal salaried jobs (8%) This suggests that workers frequently rotate between jobs, and this might even underestimate the level of rotation, given that it does not take into account movements within a single year (Bosch, Melguizo and Pagés, 2013[4]) (OECD/IDB/The World Bank, 2014[5]) (Goñi, 2013[6]).

High levels of job rotation result in a large number of incomplete contribution histories, which lead to low pensions savings in the SPP and, in many cases, ineligibility to receive the pension at the age of retirement for those affiliated with the SNP. The density of contributions (i.e. the percentage of time contributing into a pension system) is low for many due to job rotation, and usually affects more the most disadvantaged, who are more likely to exit the formal sector recurrently. In Peru, around 50% of working-age men have never contributed to the pension system, and among those who have contributed, 49% did so for less than 50% of the time. For working-age women, the picture is even more problematic: around 75% have never contributed, and almost 50% of those who have contributed have done so for less than 50% of the time (Bosch, Melguizo and Pagés, 2013[4]) (OECD/IDB/The World Bank, 2014[5]). A retiring worker has to have contributed for 20 years to receive a pension at retirement age in the SNP. Given the low levels of formality and low contribution densities, workers who transit between formal and informal employment are not likely to achieve 20 years of contributions to the SNP, which is likely to lead to significant numbers of older people without pension benefits.

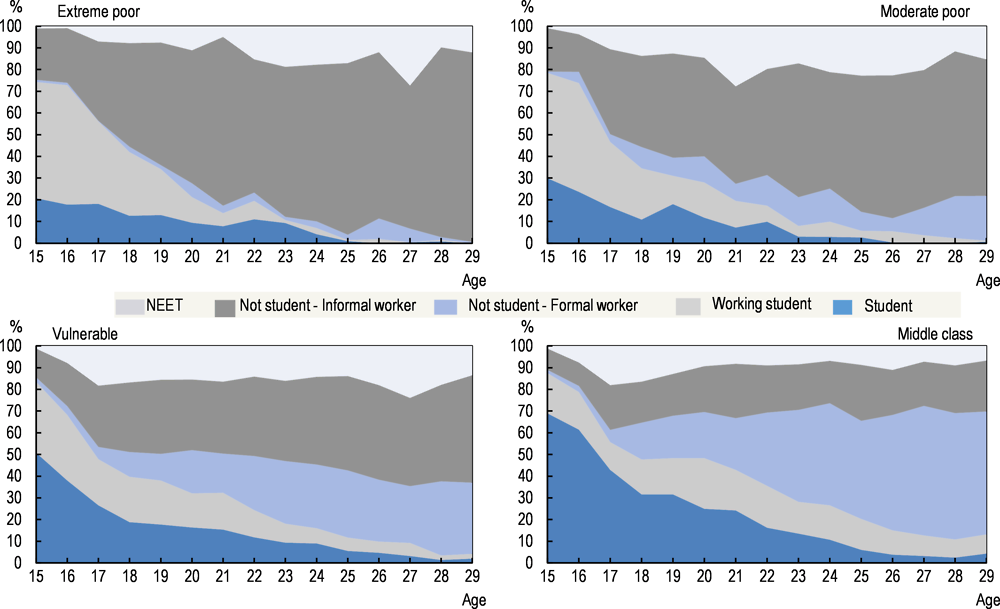

Poor labour outcomes are particularly pressing for those belonging to most disadvantaged groups. In particular, labour outcomes for youth show that the first steps of the working trajectory usually involve periods of inactivity and/or working on informal jobs, oftentimes while studying. Only around 19% of young people (aged 15-29) were studying in 2014, while around 12% were NEETs (neither in employment nor in education nor training), 16.9% were working students, and 52.7% were working. NEETs are more numerous among the youth from poor and vulnerable socioeconomic groups (almost 70% of all young NEETs). Among those young people who work, the informality rate is as high as 65.2% (OECD/CAF/UN ECLAC, 2016[7]).

Young people from poor and vulnerable households face more difficulties in accessing formal jobs. This is crucial, as it can largely determine their capacity to reach a density of pension contributions along their working trajectories that is sufficient to have access to a pension at the age of retirement or to accumulate a sufficient level of assets. Looking at the activity status of youth from different socioeconomic backgrounds at different ages (from 15 to 29) in Figure 5.8 provides a clear picture of the challenges they face to access a formal job. For young people from poor households, two out of ten 15-year-olds work in informal jobs, but by age 29 almost nine out of ten work in informal jobs, and the remaining one is a NEET. For young people belonging to the vulnerable class, half are informal by age 29, and around 15% are NEET. This compares to young people belonging to households in the middle-class, of whom only two out of ten are informal workers by age 29 (OECD/CAF/UN ECLAC, 2016[7]).

Figure 5.8. Activity status of youth by single year of age, 2014

Note: Socio-economic classes are defined using the World Bank classification: “Extreme poor” = youth belonging to households with a daily per capita income lower than USD 2.50. “Moderate poor” = youth belonging to households with a daily per capita income of USD 2.50-4.00. “Vulnerable” = individuals with a daily per capita income of USD 4.00-10.00 “Middle class” = youth from households with a daily per capita income higher than USD 10.00. Poverty lines and incomes are expressed in 2005 USD PPP per day (PPP = purchasing power parity). LAC weighted average of 16 countries: Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Dominican Republic, Ecuador, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Mexico, Panama, Paraguay, Peru and Uruguay.

Source: (OECD/CAF/UN ECLAC, 2016[7]).

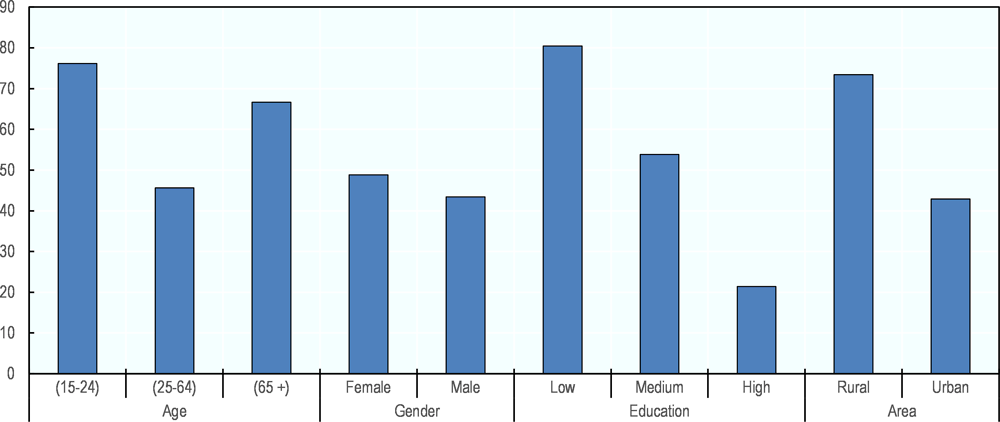

Informality levels are higher for young females with low levels of education and living in rural areas. Informality is linked to other socioeconomic characteristics that go beyond income levels, though these are correlated with income. In particular, and using the legal definition of informality (i.e. a worker is considered informal if (s)he does not contribute to a pension for retirement), young people (aged 15-24) show particularly high levels of informality (76.2%). This is also the case for females (48.8% rate of informality vs. 43.4% for males), for low-educated workers (80.5% of informality vs. 53.8% and 21.4% for medium- and high-educated individuals, respectively) and for people living in rural areas (73.4% vs 42.9% in urban areas). This implies that the contributory pension system faces particular challenges to reach certain socioeconomic groups (Figure 5.9).

Figure 5.9. Informality levels across different socioeconomic groups, 2016

Notes: 1) The legal definition of informality is used here, by which a worker is considered informal if (s)he does not contribute to a pension for retirement;

2) the categories on gender, education and area only include adults aged 25-64.

Source: (SEDLAC, 2018[8]).

5.2. The level of pension benefits

The level of pension benefits that individuals receive is a function of the level and amount that they have contributed and the age at which they retire, among other variables. In Peru both of these factors lead to low levels of benefits. This is firstly driven by low levels of mandatory contributions compared to international standards and, in the SPP, a lack of additional voluntary contributions to compensate. Secondly, contribution density (i.e. the number of contributions that individuals make relative the time that they have been affiliated with the system) is low. Finally, in the SPP, individuals can easily withdraw their retirement savings before the legal retirement age.

Low contribution density in the SNP can result in no pension benefits received if individuals do not achieve the minimum number of twenty years of contributions. In the SPP, low contribution density results in a lower level of assets accumulated at retirement.

In addition, the design of the SPP is not conducive to encouraging individuals to contribute and to keep their contributions in the system until the normal retirement age. The incentives for individuals to make voluntary contributions to their pensions are limited. Affiliates are allowed to withdraw assets from their account during accumulation to purchase a first home. Numerous pathways to early retirement also exist that allow individuals to withdraw their assets much earlier than the normal retirement age.

This section examines the level of mandatory contributions to the pension system, the contribution densities, the replacement rates that individuals can expect to receive from the pension system, and the potential impact that the early withdrawal of assets may have on the ability of assets accumulated to be able to finance an adequate pension.

5.2.1. Contribution levels

The level of contributions directly influences the levels of expected replacement rates that pension income can provide. In Peru, mandatory contributions to the public and private system are nearly equivalent at around 13% of salary, which under both systems is expected to cover retirement pension benefits, disability and survivor benefits as well as the administrative costs of running the schemes. Contributions going directly to finance old-age benefits under the private system amount to 10%.

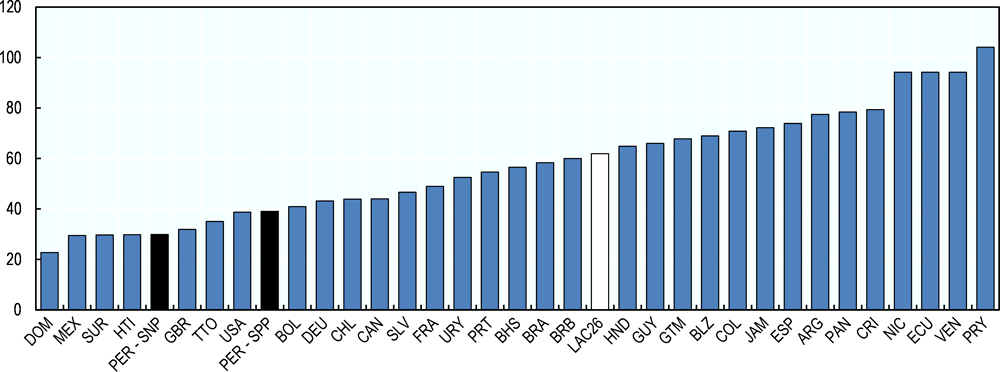

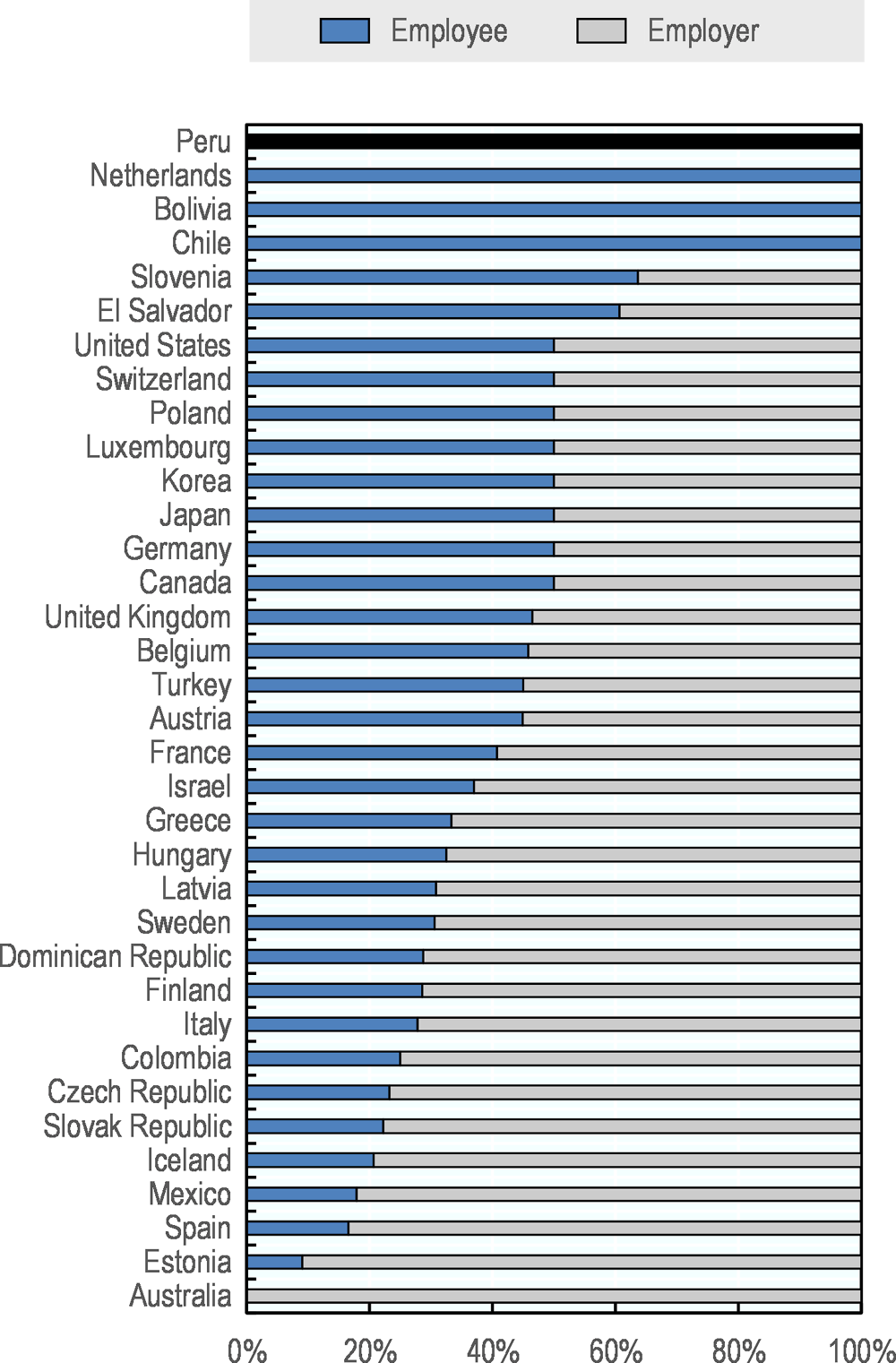

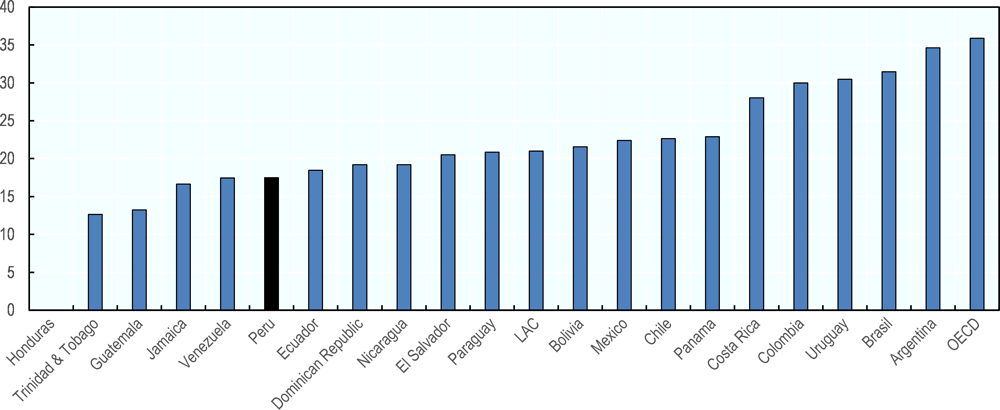

Contribution rates in Peru are low in the context of OECD countries, although comparable to other Latin American countries. Figure 5.10 shows the mandatory contributions to pension systems for selected jurisdictions. In terms of total pension contributions, 10% to the SPP is rather low internationally, though comparable to other Latin American countries that also have systems based on funded individual accounts (Bolivia, Chile, Colombia, Dominican Republic, El Salvador).

Figure 5.10. International comparison of mandatory pension contributions, 2016

Since 2013, the SBS is required to review the level of mandatory contributions to the SPP in Peru every seven years. The level of contributions must be assessed in light of the experience of both the economic and demographic variables that affect the ultimate pension that can be achieved. The regulatory framework requires that the contribution level be sufficient to allow members to expect an adequate replacement rate in light of current expectations around life expectancy and long-term investment returns. The first review of the contribution level will occur in 2019.

5.2.2. Contribution density

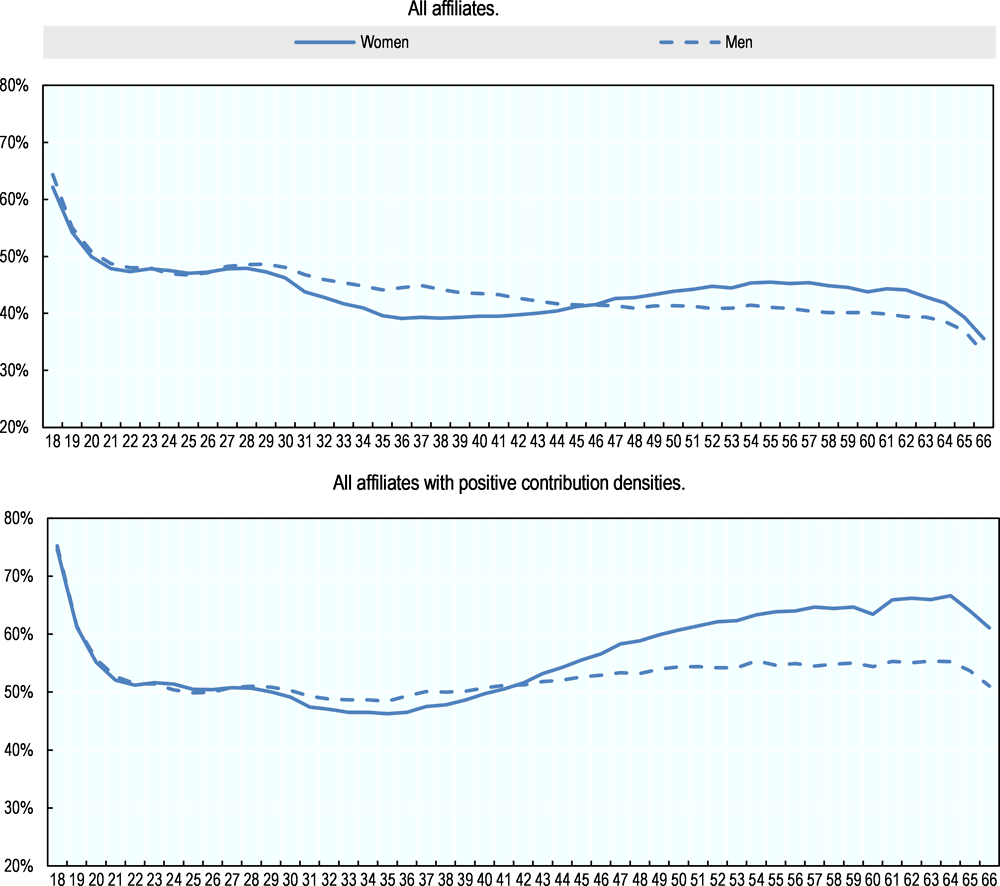

Individuals often do not contribute to the pension system throughout their career because of high rates of informality and transitions between formal and informal employment. Therefore, the number of individuals that are contributing to the pension system at any given time is significantly lower than the number of affiliates who have ever contributed to the system. On average, only 45% of the affiliates in the SPP at the end of 2017 had contributed to their accounts in the last month.

The low frequency of contributions, or low contribution density, reduces the level of benefits that individuals will be able to accrue in the pension system. Figure 5.11 shows how often individuals are contributing to their pension. On average for all affiliates, both genders contribute less than 45% of the time during which they have been affiliated with the SPP. However, when considering only those affiliates with positive contribution densities, this average increases to over 50%. For this latter group, contribution densities tend to increase with age from the mid-30s. Contribution densities are virtually the same for both males and females under the age of 30, but males in their 30s have higher contribution densities than females. From the mid 40s, however, females have higher contribution densities than males, and for those with positive contribution densities the difference between the genders increases with age. Just before the normal retirement age, female affiliates in this group have contributed around 65% of the time since they joined the system, whereas males at this age have contributed only 55% of this time.

Figure 5.11. Density of contributions in the SPP by age and gender

Source: SBS.

Considering both systems, Peru has a lower proportion of the economically active population contributing than the majority of other Latin American countries. In Peru, 17.3% of the PEA contributed to the SPP in December 2017 (Figure 5.12), compared to 9.3% that contributed to the SNP. This compares to 38.4% and 26.4% of the PEA that are affiliated with the two systems, respectively.

Figure 5.12. Contributors to private pensions as a proportion of the economically active population

Source: Asociación Internacional de Organismos de Supervisión de Fondos de Pensiones, AIOS, Statistical bulletin, 2018.

5.2.3. Replacement rates

The level of the pension relative to the level of last wages provides an indication of how adequate the expected pension benefits will be to maintain a similar standard of living in retirement. The calculation of these replacement rates is a hypothetical exercise based on a common set of economic parameters across countries, thereby allowing for a comparison of the pension system independent of outside factors.

These economic parameters are price inflation, real earnings growth, and the rate of return. For the countries within Latin America and the Caribbean, the assumptions have been set at 2.5% for price inflation, 2% for real earnings growth and 3.5% for the real rate of return, after fees, for defined contribution pension systems.

Peru has among the lowest hypothetical replacement rates in Latin America and the Caribbean and selected OECD jurisdictions. Figure 5.13 shows the hypothetical replacement rate that average-earning males beginning to contribute to the pension system now can expect to receive after a full career with no breaks, given the current rules of the different systems. It shows the replacement rate for both the public and private systems for Peru. For the SNP, the low replacement rate is the result of the maximum pension imposed. While a full 45-year career would give a replacement rate of 80% given the accrual formula, there is a maximum pension of PEN 857.36 per month that has not increased since 2001. However, for this analysis price indexation has been assumed. In the long-term if the maximum pension from the SNP is indexed to price inflation then the future replacement rate for someone entering the labour market today would be 29.9% for a full career average earner, as shown in Figure 5.13. This is one of the lowest of any country within the Latin American and Caribbean region and is also well below the level of the pension that would be achieved from the SPP, which has a replacement rate of 39.1% after a 45-year career. The average for Latin American and Caribbean jurisdictions is much higher at 61.9%.3

Figure 5.13. Hypothetical Gross Pension Replacement Rates: Average-earning males

Note: Hypothetical gross replacement rates based on current pension system characteristics and rules. They are calculated for someone entering the labour market in 2012 at age 20 and working a full career until the normal retirement age. Price inflation is assumed to be 2.5%, real earnings growth is 2% and the real rate or return is 3.5%.

Source: (OECD/IDB/The World Bank, 2014[5]). Revised calculations for Peru from OECD pension model.

In the long-term if the maximum pension is not indexed, the future replacement rate would only be 9.9% from the SNP. Conversely, if the maximum pension were indexed to wage growth then the replacement rate would be 73.0%, though clearly this would also imply a significant increase in cost.

The analysis above refers to the levels of pension entitlement for average earners, who because of both their earnings levels and full career condition are capped at the maximum pension in the SNP. However, those with much lower earnings and shorter careers may benefit from the minimum income guarantee of the SNP. The minimum is set at PEN 415 per month, equivalent to 35% of average earnings, and like the maximum level has not been increased in many years.

Indeed, low earners having at least 20 years of contributions to the SNP are likely to get a higher pension than they would have otherwise because of the minimum pension guarantee. Anyone retiring today with a 20-year career whose lifetime average earnings are below 88% of the national average would have their benefit topped-up to the minimum pension level. For those at the low earnings level as classified by the OECD, i.e. 50% of the national average, the minimum pension represents a 70% replacement rate, assuming price indexation. These individuals would need to have a contributory career of over 35 years before they would be able to achieve a pension above that of the minimum level, implying that they would be very likely to benefit from the minimum guarantee.

However, if there remains no indexation to the minimum pension then the impact of having a minimum pension will be eliminated in the long-term. Under the modelled assumptions for price inflation and wage growth, the minimum pension will be equivalent to under 15% of average earnings by 2036, meaning that even those with low earnings (50% of average) will not benefit unless the level of the minimum pension is increased in the interim.

Currently, however, the minimum pension is playing an important role, especially because of the parallel nature of the public and private pension systems. Individuals who transferred from the SNP to the SPP and who have not accumulated sufficient assets to finance the minimum pension level are still entitled to the minimum pension that they would have received in the SNP. Law 27617 allows individuals who were born before December 1945, are at least 65 years old, and have at least 20 years of contributions in either system to be eligible for the minimum pension. For individuals born after 1945, Law 28991 establishes a complement pension of a minimum pension to top up the pension amount for those who are receiving a pension in the SPP that is lower than the minimum.

The number of individuals in the SPP receiving the minimum pension has increased rapidly. Table 5.1 shows an increase from only 2 186 in 2007 to 12 000 individuals in 2017, before a slight decrease in 2018 to 11 904. The associated cost to the SNP has also increased, from PEN 10.85 million in 2007 to PEN 68.12 million in 2018, though the net cost is lower because capital accumulated in their pension pots de facto finances part of it. In any case, the cost remains low at less than 0.01% of GDP.

Table 5.1. Number of recipients and cost of minimum pension in the SPP

|

Year |

Number of recipients |

Annual Cost (PEN Million) |

|---|---|---|

|

2007 |

2 186 |

10.85 |

|

2008 |

2 590 |

13.33 |

|

2009 |

2 956 |

15.67 |

|

2010 |

3 742 |

18.69 |

|

2011 |

4 728 |

23.79 |

|

2012 |

5 540 |

28.25 |

|

2013 |

6 628 |

34.24 |

|

2014 |

8 586 |

41.95 |

|

2015 |

10 795 |

54.4 |

|

2016 |

11 818 |

63.81 |

|

2017 |

12 000 |

67.62 |

|

2018 |

11 904 |

68.12 |

Source: SBS.

5.2.4. Replacement rate sensitivities

The intention of the initial replacement rate calculation is to compare pension systems across countries under the same economic and contribution density scenario. All of the results for replacement rates in the previous section are based on an average earner with a full career of 45 years, beginning contributions at age 20 and retiring at 65. In addition, the economic assumptions used (price inflation of 2.5%, real earnings growth of 2%, and real rate of return of 3.5%) are the same for all countries and may not accurately reflect the situation in Peru.

The assumptions regarding contribution years and the rate of return in particular do not likely reflect the situation in Peru. Contributions tend to be made less frequently over the career, resulting in fewer than 45 years of contributions. With respect to net returns, the bidding process for the administration of the new affiliates´ accounts is expected to lead to a lower level of fees, which in theory could lead to an increase in the net rate of return after fees.

As mentioned above, affiliates to the SPP contribute on average around 45% of the time that they are affiliated. This would represent 20 years of contributions assuming that the contribution density throughout the career were to remain at 45%. For the public system, this would theoretically lead to a replacement rate of 30% for those born from 1972 onwards, irrespective of when the contributions are made.

For the SPP the timing of contributions is the most important factor, as the earlier the contributions are made the more time they have to accumulate over the working life. If 20 years contributions were made at the beginning of the career, the replacement rate would reduce to 20.7% from 39.1% for a full career of contributions (Table 5.2). Contributing for 20 years at the end of the career, i.e. from age 45 to 64 would give a replacement rate of only 14.3%. Either way the replacement rate from the SNP is higher, as 20 years of contributions guarantees a replacement rate of 30%.

Table 5.2. Sensitivity of replacement rates to contribution history

|

Contribution history and pension type |

Gross replacement rate (%) |

|---|---|

|

SPP - 45 years of contribution |

39.1 |

|

SPP - 20 years of contribution (ages 20-39) |

20.7 |

|

SPP - 20 years of contribution (ages 45-64) |

14.3 |

Source: OECD pension model calculations.

The replacement rate that the SPP system provides is sensitive to the rate of return. Calculations in Table 5.2 have assumed that the rate of return above wage growth is 1.5% (2% real earnings growth and 3.5% real rate of return after fees). If this value were to increase to 2.25% then the replacement rate would be 47.6% for a full 45-year career, compared to 39.1% for the 1.5% scenario (Table 5.3). Increasing further to 3% would give a gross replacement rate of 58.1%. However, if the effective rate were to fall to 0.75% above wage growth or to zero then the replacement rates would fall to 32.6% and 25.9%, respectively.

Table 5.3. Sensitivity of replacement rates to rates of return

|

Real rate of return - real wage growth |

Gross replacement rate |

|---|---|

|

0 percentage points |

25.9 |

|

0.75 percentage points |

32.6 |

|

1.5 percentage points |

39.1 |

|

2.25 percentage points |

47.6 |

|

3 percentage points |

58.1 |

Source: OECD pension model calculations.

5.2.5. Withdrawals during accumulation in the SPP

Withdrawing assets from the pension account before retirement will reduce the level of assets that individuals will have accumulated to finance their retirement. Since 2016, affiliates to the SPP are allowed to withdraw 25% of the accumulated balance from their individual account for the purpose of making a down payment or paying down the mortgage for the purchase of a first home. AFPs are responsible for verifying that the requested funds are actually being used for this purpose. The total number of individuals exercising this option in 2016 and 2017, shown in Table 5.4, was around 35 thousand and 22 thousand, respectively, falling to around 15 thousand in 2018. This represented only between 0.2% and 0.6% of total affiliates to the SPP for these years.

Table 5.4. Number of affiliates withdrawing from their account for buying a first home

|

Year |

Down Payment |

Amortization |

Total |

|---|---|---|---|

|

2016 |

1 738 |

33 353 |

35 091 |

|

2017 |

5 605 |

16 313 |

21 918 |

|

2018 |

7 501 |

8 100 |

15 601 |

Source: SBS.

5.2.6. Early retirement in the SPP

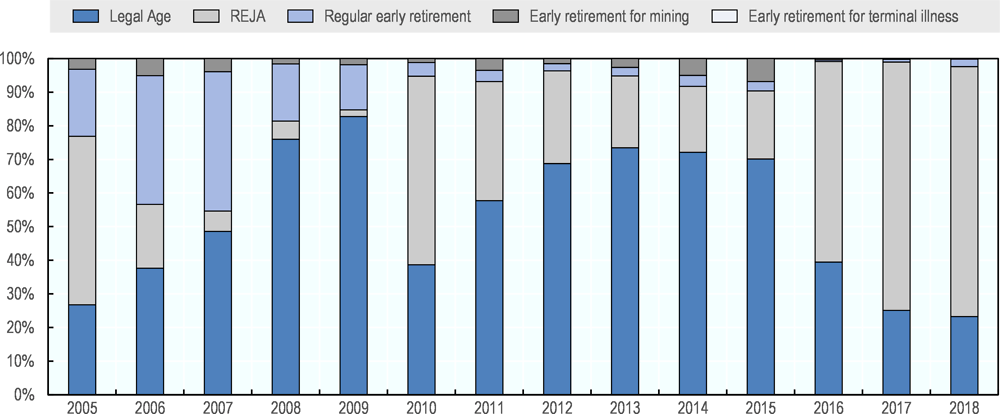

Early retirement will reduce the time that individuals will have to accumulate assets and increase the length of time that those assets will need to last to finance retirement. A large proportion of pensioners retiring in the SPP do so before the legal retirement age of 65 by meeting the criteria for one of the pathways to early retirement. The various retirement options are presented in Table 5.5. The regular early retirement regime allows individuals to retire early as long as they have sufficient assets to provide a minimum replacement rate. Since 2017, individuals are also allowed to retire early if they are diagnosed with cancer or have another terminal illness. The REJA regime allows early retirement for the unemployed.

Table 5.5. Pathways to retirement in the SPP

|

Type |

Criteria |

|---|---|

|

Legal Retirement |

Aged 65 or over |

|

Regular early retirement |

Males aged at least 55 and females 50 who have sufficient assets to provide a replacement rate of 40% of the average salary over the last 120 months |

|

Terminal Illness |

Terminal illness or cancer not eligible for a disability pension |

|

REJA |

Males aged at least 55 and females 50 who have been unemployed for at least 12 consecutive months and whose income during that time did not exceed 7 tax units (UIT) |

Note: Prior to May 2019, individuals were also required to have a 60% contribution density over the last 120 months to retire under the regular early retirement regime, and the replacement rate was calculated over the last 10 years of salary. To retire under the REJA regime, accumulated assets had to be sufficient to finance a pension that was at least the minimum wage, and there was no restriction on the amount of income that could be earned during the period of unemployment.

Source: SBS.

On average, since 2005 just over half of the individuals retiring under the SPP have retired at the legal age, with the remaining retiring early. However, the proportion of individuals retiring at a normal retirement age varies widely from one year to the next, ranging from a high of 85% in 2009 to a low more recently of 24%. Figure 5.14 shows the proportion of retirees following the different pathways to retirement. Since 2010, the majority of individuals retiring early have done so under the REJA regime, which allowed males to retire at 55 and females at 50 if they have been unemployed for at least 12 consecutive months and they could finance a pension that was at least the minimum wage, though this latter requirement was removed in 2019 and replaced with a maximum income that could be earned during the period of unemployment. The proportion of individuals retiring under the REJA regime increased dramatically in 2016, coinciding with the law allowing individuals to take their accumulated assets as a lump-sum at retirement.

Figure 5.14. Proportion of individuals retiring in the SPP per regime

Source: SBS.

The allowance for an early retirement has a significant impact on the average age at which individuals decide to retire, and therefore not only how long the assets in their pension account continue to accumulate but also how long those assets need to last once the individual withdraws them from their account. Table 5.6 shows the average age of retirees since 2008 under both the early retirement regimes and the normal retirement regime. While the average age of those retiring early has increased over this period, people still retire on average five years before the legal retirement age of 65. Those who retire under the normal regime, however, work two years beyond the legal age on average.

Table 5.6. Average retirement ages

|

Year |

Ordinary early retirement |

REJA |

Legal Age |

All |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

2008 |

55.2 |

61.5 |

66.3 |

64.4 |

|

2009 |

56.6 |

63.1 |

66.2 |

65.3 |

|

2010 |

57.4 |

58.0 |

66.4 |

62.0 |

|

2011 |

57.5 |

57.8 |

66.6 |

63.4 |

|

2012 |

57.8 |

57.8 |

66.5 |

64.3 |

|

2013 |

58.1 |

58.0 |

66.6 |

64.9 |

|

2014 |

58.7 |

58.0 |

66.8 |

65.2 |

|

2015 |

59.1 |

58.2 |

66.7 |

65.0 |

|

2016 |

57.5 |

57.5 |

67.2 |

61.9 |

|

2017 |

56.6 |

57.2 |

66.8 |

60.1 |

|

2018 |

54.1 |

56.8 |

66.6 |

59.5 |

|

2019* |

51.7 |

57.6 |

66.6 |

61.9 |

Note: *As of May 2019.

Source: SBS.

5.3. Policy options

In order to expand coverage of the pension system, the problem of high levels of informality in the labour market needs to be addressed, though this problem also has implications beyond pensions. It is important to keep in mind that independent and self-employed workers are considered informal workers in the official definition.

The problems posed by informality for pensions could be addressed by encouraging informal workers to become formal, and thereby be subject to the requirement to contribute to the system, or by expanding coverage to independent workers through mandates or incentives to contribute. The high cost of formalisation represents a large barrier for informal workers to become formal workers, particularly those in low-income groups. These costs could be reduced by subsidising the social security contributions for these groups. Nudges and incentives for informal and independent workers to contribute voluntarily to the pension system, such as subsidies targeted to specific populations, could increase the coverage of the system for these workers.

For independent workers, specific measures, such as reintroducing the mandate could be considered. However, in order for this measure to succeed it would need to be implemented differently than it was in 2014, and consider using more flexible payment schedules and innovative collection mechanisms.

The amount of contributions going into the system will also need to be increased to improve the level of pension benefits that the system can pay. This could be done either through increasing the mandatory level of contributions or by providing financial incentives or nudges for individuals to make additional voluntary contributions to their account beyond the mandated percentage of wages.

Opportunities for individuals to access their pension benefits before the legal retirement age should also be limited to allow individuals the time to accumulate sufficient pension benefits. As such, withdrawals for a first home should be limited, the gender gap for early retirement should be closed and early retirement schemes should be more restrictive.

5.3.1. Promote formal employment and improve coverage of the pension system

Policies to strengthen the coverage of the pension system must be designed taking into account their linkages with the functioning of labour markets. A broad array of policies are available that can alter the supply and demand of formal jobs by changing the incentives of employers and employees to reach formal job agreements. In this respect, and given that the contribution to a pension scheme is directly linked to having a formal job, policies to improve the coverage of the contributory pension system must be conceived in coordination – and hence taking into account potential trade-offs – with other policies affecting labour markets, mainly labour, fiscal, and social policies.

Increase the relative cost of informality

Policies to promote formal jobs will be critical to build a stronger, more effective pension system in Peru. Insofar as high informality limits pension coverage, putting in place policies that address the multiple causes of informality and favour the creation of formal jobs must be at the centre of the agenda to build a stronger pension system. These policies range from efforts to promote the formalisation of firms (including a reduction of costs of becoming formal and the simplification and integration of special tax regimes to provide incentives to formality) to policies to promote the formalisation of jobs. The focus here is on the latter set of policies, and more in particular on efforts to reduce costs of formalisation for groups where these are binding.

Costs of formalisation are particularly burdensome for workers in the bottom of the income distribution. In Peru, the average cost of pension and healthcare programmes represent 17.5% of total labour costs for salaried workers, 10.1% of which is paid by the employee, and 7.4% by the employer (OECD, 2016[3]).

The high costs of formalisation in order for salaried workers in low-income groups to access social security may lead them to rather become self-employed in order to have the free access to social security given to independent workers (OECD, 2016[3]) (OECD/IDB/CIAT, 2016[10]). Most informal workers are not subject to the general regime, given that a large share of them are self-employed. Independent workers in the first three deciles qualify to access the free health system (Sistema Integrado de Salud – SIS) and thus do not pay social security contributions. This creates a large gap and may generate incentives to remain self-employed and not declare a share of income in order to remain with free access to the SIS, the existence of which diminishes the benefit of being formal.

Subsidising the social security contributions of low- and low-middle income workers could be an effective way to incentivise pension savings for those who, given their low levels of income, do not see this as a priority. By subsidising these workers, the cost of formality is de facto reduced, hence creating an incentive to be formal.

Nevertheless, the specific design of the subsidy (size, group of focus, etc.) will determine its potential success. In order to reach those who are most burdened by the cost of formalisation, the subsidy could target these low-income groups. To align incentives to become formal, the amount of subsidy could also decrease with income, with lower incomes receiving a full subsidy of their social security contributions, and the proportion of the subsidy being reduced as income increases.

Evidence from countries like Chile, Colombia and Turkey shows that subsidies have had an impact in increasing formal jobs and hence pensions’ coverage (Melguizo, Bosch and Pagés, 2013[11]). In the case of Chile, the impact evaluation of the programme for the subsidy of youth employment shows improvements in formality rates across eligible young workers of around 4.8 and 6.6 percentage points for 2009 and 2010, respectively (Universidad de Chile, 2012[12]). In Turkey, the evaluation of various regionally targeted employment subsidies for low-income groups shows that these increased formalisation of existing firms and jobs rather than creating new economic activity. This would suggest that in countries with relatively weak enforcement institutions, high labour costs on low-income workers create a strong incentive for informality for both firms and workers (Betcherman, Daysal and Pagés, 2010[13]).

Encourage informal and independent workers to join and contribute to the pension system

Increasing the coverage of independent workers and their participation in the system could be done through measures that encourage voluntary contributions or alternatively mandating participation. Given the low voluntary contributions to the pension system by these workers, there needs to be alternatives in place to incorporate them into the pension system. Furthermore, informal workers, and in particular independent workers, usually transition more frequently between types of jobs and present higher levels of informality, which leads to more irregular contribution patterns and hence to lower densities of contributions. Specific measures targeted at specific populations, such as distinguishing between low-income informal workers and independent workers, could be most effective.

Targeted subsidies for low-income informal workers

Establishing a system of targeted subsidies could more directly incentivise voluntary pension savings among informal workers. A large share of workers (around 52% of informal workers in 2014) earn less than the minimum wage in Peru (OECD, 2016[3]). This implies that the above mentioned mechanisms to subsidise social security contributions for low-income workers would actually not reach a large share of the workforce. In fact, in 2016 the minimum wage (which is usually the threshold above which social security contributions start) was equivalent to the income levels of the sixth decile of the income distribution, which implies that the first five deciles would not be receiving these type of subsidies (OECD, 2016[3]). In order to reach workers in lower income deciles, a system of targeted subsidies for pension contributions could be more effective to encourage voluntary contributions. The risk with this type of mechanism is that it can create an incentive to remain informal, so it has to be designed in a way that does not create a parallel system, but rather is integrated into the broader social security system. This could be done, for example, by targeting a matching contribution to all workers below a certain income level, and could be provided for a limited number of years only.

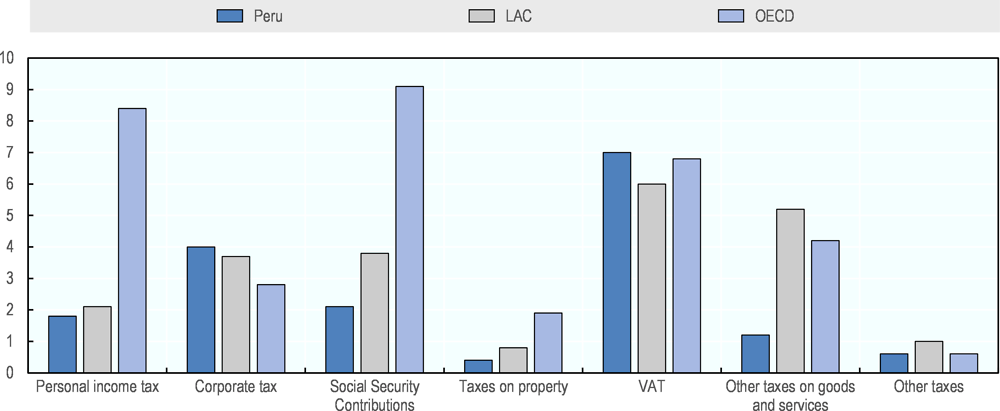

Introducing subsidies, however, would require financial resources. Higher financial resources can accrue as the tax base increases with the level of formality, which the previous section addressed. Informality erodes the tax base and represents a critical challenge in Peru, given the already low level of tax revenues. Tax revenues over GDP represented only 16.1% in 2016, relative to LAC average (22.7%) and the OECD average (34.3%) (OECD et al., 2018[14]). Additionally, the available fiscal space in Peru allows for increasing taxation.

Additional tax revenues could mainly come from larger tax revenues on personal income tax, taxes on property, and other taxes on goods and services. The bulk of Peru’s fiscal revenues are raised by consumption taxes with a strong dependency on VAT (37% of total taxes), a characteristic shared with other LAC economies. On the contrary, direct taxes, especially personal income tax (PIT) and social security contributions are less significant in Peru’s tax collection (Figure 5.15). While PIT revenues represented 1.8% (11% of total taxes) of Peru’s GDP in 2016, the average share in Latin American and OECD countries was 2.2% (10% of total taxes) and 8.4% (25% of total taxes) of GDP, respectively. All in all, the space for raising tax revenues appears mainly in personal income tax, taxes on property, and other taxes on goods and services (OECD et al., 2018[14]) (OECD/CAF/UN ECLAC, 2016[7]).

Figure 5.15. Tax revenues by type of taxes in Peru, Latin America and the OECD, % of GDP

Mandating participation for independent workers

As an alternative to providing incentives for independent workers to voluntarily contribute to the system, contributions of independent workers to the pension system could be made compulsory again, but accompanied with: 1) the possibility to have more flexible contribution schedules and patterns; and 2) innovative collection mechanisms (OECD, 2016[3]).

More flexibility with respect to contributions for independent workers is crucial to encourage them to contribute. Currently, even affiliates who choose to voluntarily contribute to the system are required to contribute a minimum of 10% of their monthly salary. This can be a large deterrent for independent workers who have more variability in their salaries to contribute. Chile provides an example where irregular contributions corresponding to the income pattern of seasonal industries and workers are allowed (OECD, 2018[16]). Current work at the OECD on non-standard forms of work also suggests that more flexible contributions can help those workers to save for retirement.

Innovative collection mechanisms can also be a cost-effective way of promoting pension contributions. For example, there could be agreed withdrawals through utility bills (mobile phone, water, electricity) that could replace the automatic withdrawal that could not be enforced for independent workers whose contributions are not automatically deducted by employers (Melguizo, Bosch and Pagés, 2013[11]) (OECD, 2018[16]). This type of withdrawal on the expenditure side (not on the income side as it happens with formal salaried workers) provides an alternative for pensions’ savings and can create a greater sense of belonging of workers usually excluded from social schemes.

Nudges for independent workers

Insights from behavioural economics have encouraged the use of new techniques to foster pension savings across independent workers in various countries. One example is found in Brazil, where the Brazilian Ministry of Social Security experimented in 2014 with reminders by post to independent workers about their obligation to contribute to social security. Compliance rates increased by 7 percentage points within the first three months after sending the reminders (OECD, 2018[16]).

Another interesting example of nudging people to save for retirement is in Mexico, where the regulatory commission (CONSAR) and the private retirement fund administrators (AFORES) have explored new ways to narrow the savings gaps by encouraging voluntary retirement savings based on insights from behavioral economics. Three years of experiments (from 2015 to 2018) led to several lessons learned. First, capturing the attention of workers is a critical first step, and can be done using both regular mail and text messages as well as sending frequent reminders. Second, providing clear feedback on how savers are doing in the accumulation of retirement savings can be effective. Retirement account statements received by workers showed a thermometer intended to illustrate the evolution of savings, alongside other personalised tips for savings. This increased the number of account holders making contributions by 40%. Third, the use of a smartphone app that pictured the face of users as if they were old made them empathise with their future self, and led to an increase in 13% of account holders making contributions. The app “Afore Movil” also makes contributing to pensions easy, and takes advantage of the significant number of mobile phone users as a way to expand pensions coverage (Fertig, Fishbane and Lefkowitx, 2018[17]) (IDB, 2017[18]).

5.3.2. Increase contribution levels and density

The level of contributions and the frequency with which they are paid (contribution density) need to be increased for the entire system. The SPP can be used as an example to demonstrate the impact that low levels and densities of contributions can have on the expected retirement income. The best-scenario replacement rate under the SPP at 40% is low by international standards. This best-scenario rate assumes a full career in the formal sector with no contribution gaps. This scenario is not at all realistic in Peru given the low density of contributions resulting from high levels of informality and the tendency for people to move between the formal and informal sectors. The more realistic replacement rates of around 15-20%, accounting for a much lower density of contributions, means that most people will not be able to receive an adequate income in retirement from the pension system that could allow them to maintain their standard of living.

In order to target a higher replacement rate from the system, contributions will have to increase. The level of contributions to the pension system is a key driver for the level of pension income that the pension system will be able to deliver. With overall contributions at 13% of income, Peru is at the low end internationally in terms of the amount of mandatory contributions to the pension system, whether that is public or private. Table 5.7 shows the level of contribution rates needed to achieve different target replacement rates with a given probability for a funded individual account. With a 10% contribution rate over a 40-year period, there is only around a 50% chance of achieving a target replacement rate of 60%, and a 25% chance of having a replacement rate below 40%. In order to achieve a 60% replacement rate with much higher level of certainty of 90%, contributions would have to more than double.

Table 5.7. Contribution rates needed to achieve different target RRs with a given probability

|

|

|

Target replacement rate (RR) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

30 |

40 |

50 |

60 |

70 |

80 |

90 |

100 |

|

|

Probability of reaching the target RR |

50 |

5.3 |

7.0 |

8.8 |

10.3 |

12.0 |

14.0 |

15.5 |

17.3 |

|

75 |

7.8 |

10.5 |

13.0 |

15.5 |

18.0 |

20.8 |

23.5 |

26.0 |

|

|

90 |

11.0 |

14.5 |

18.0 |

21.8 |

25.3 |

28.8 |

32.3 |

36.3 |

|

|

95 |

12.8 |

17.3 |

21.8 |

25.8 |

30.5 |

35.0 |

39.0 |

43.3 |

|

|

99 |

17.3 |

23.3 |

28.5 |

34.5 |

39.3 |

45.8 |

51.5 |

57.0 |

|

Note: Assumes uncertain investment returns, inflation, discount rates, life expectancy and labour market conditions. People contribute over a 40-year period, assets are invested in a portfolio comprising 40% in equities and 60% in long-term government bonds, and people are assumed to buy a nominal life annuity at age 65.

Source: OECD calculations.

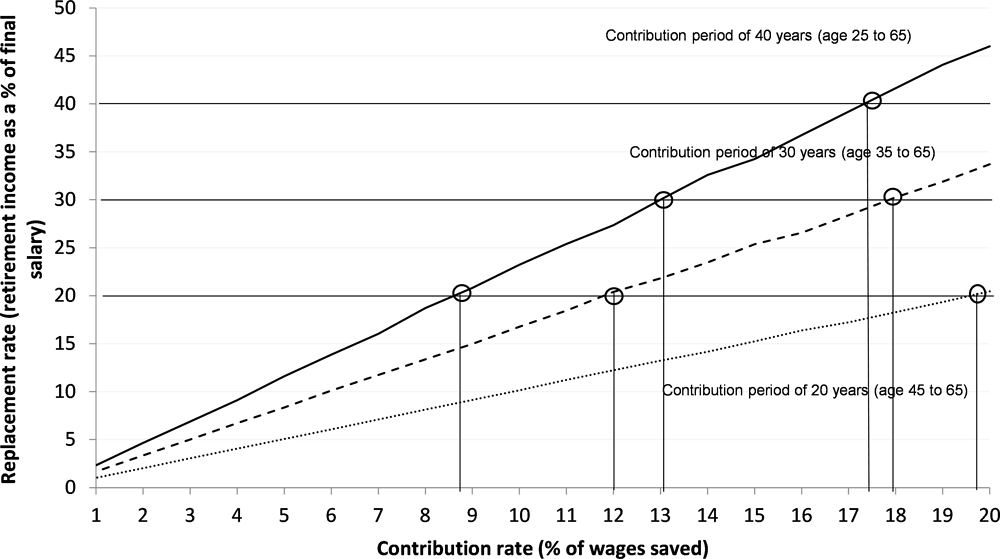

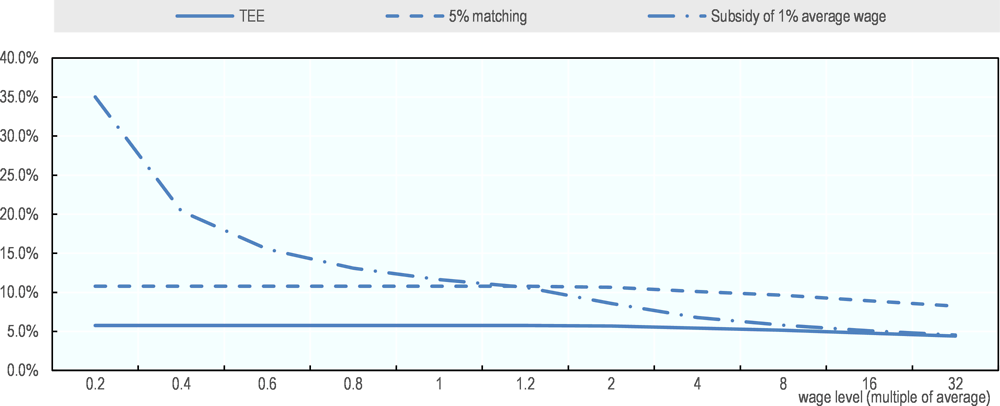

The level of contributions needed to achieve a target replacement rate also depends on the number of years spent contributing. Currently, only around 45% of those affiliated with the SPP are contributing, and on average affiliates contribute only 50% of the time during which they have been in the system. Assuming a contribution density of 45-50% of the years between the working ages of 20 and 65, this would mean that the average affiliate only contributes around 20 to 23 years to their pension account. Figure 5.16 shows the replacement rate that can be reached with a 95% probability for different contribution levels and periods. Assuming 20 years of contributions with contribution levels of 10%, the replacement rate that can be achieved with 90% certainty is only 10%. In this scenario, doubling the number of years spent contributing to 40 years would have a similar impact on the replacement rate to doubling the level of contribution to 20% of income. With 40 years of contributions at 10%, individuals could expect to have a replacement rate of 23% with 95% certainty, whereas they could expect to have a replacement of 20.5% with 95% certainty if contributing 20% of their salary for 20 years. These are, however, pessimistic scenarios with all of the contributions coming later in working life. The replacement rates would be expected to increase if contributions were made earlier, as investment returns would be earned for a longer period.

Figure 5.16. Replacement rates reached with 95% probability according to different contribution levels and contribution periods

Note: Contribution and replacement rates at the 5th percentile when assets are invested in a portfolio comprising 40% equities and 60% fixed income, assuming stochastic investment returns, discount rates, inflation, labour market conditions and stochastic life expectancy at age 65.

Source: (OECD, 2012[19]).

To increase both the level and density of contributions, policy makers can consider various options to (i) increase the mandatory contribution rates; (ii) introduce automatic enrolment for voluntary contributions; and (iii) improve incentives for voluntary contributions.

Increase mandatory contribution rates

The first option to increase contribution rates would be to increase mandatory contributions from the current level. This does not necessarily need to be borne fully by the employee, and the cost could be shared by the employer. Increases could also be implemented gradually to limit the impact on nominal wages.

The increased contributions do not necessarily have to be fully borne by the individual worker, however, and could also be paid by the employer. Indeed, in most OECD and Latin American countries, the employer pays part of the total pension contribution. Peru is one of the few countries where this is not the case, along with Bolivia and Chile, as seen in Figure 5.17. Australia is at the other end of the spectrum, with the employer paying the full mandatory contribution to the funded individual accounts.

Figure 5.17. Distribution of the total mandatory pension contribution between employers and employees, 2016

Note: Austria, Czech Republic, Dominican Republic, Estonia, Greece, Ireland, Latvia, Norway, Portugal, Slovenia, Spain, UK and US reflect the total social insurance contribution.

Increasing the level of contributions by the employer rather than the employee could mitigate the perception of increased taxation from an individual’s standpoint, particularly if the increase is not immediately felt in full through a reduction of salary. In order to avoid a reduction in salary, such an increase could be implemented gradually over time. Several jurisdictions have taken this approach when introducing additional mandatory contributions. With the introduction of mandatory individual pension accounts in Australia, employer contributions were scheduled to be increased progressively from 3% in 1992 to 9% in 2002. In 2012, an additional increase of 3% was introduced, to be implemented gradually through 2025 to achieve a total contribution rate of 12% in 2025. The United Kingdom gradually increased the default contribution rates for their automatic enrolment programme, though at a much more rapid rate of increase. Contributions were raised by six percentage points over the course of five years, going from 2% in 2012 to 8% in 2018.

The main problem with increasing mandatory contributions is the capacity of low wage earners to do so. One way to avoid this problem is to link the increase in contributions to wage growth. Such an approach mitigates the loss aversion that individuals may suffer from a reduction of nominal wages by increasing the contributions in line with wage increases so that nominal wages never fall. This approach has been shown to successfully increase pension savings even through voluntary contributions in the United States (OECD, 2018[20]). It could therefore be a reasonable approach to mitigate the disincentives to being formally employed. However, it should be noted that people will be contributing a different mandatory rate until they all reach the target rate. Moreover, if employer’s contributions were added this would not apply to self-employed and, therefore, their contribution could be lower.

In considering whether to increase mandatory contribution levels, policy makers must also consider how much room there is for such an increase given the existing tax burden borne by employees. Figure 5.18 shows the tax wedge for the 5th income decile in Latin America and the Caribbean. With a tax wedge on labour of 15.5%, Peru has a lower tax burden from an international standpoint. The average tax wedge in the region is 21%, and for the average earner in OECD countries it is 35.9%. There may therefore be room to increase mandatory contributions in Peru.

Figure 5.18. Tax wedge on labour, 2013

Note: The tax wedge is defined as the ratio between the amount of taxes paid by an average single worker (a single person at 100% of average earnings) without children and the corresponding total labour cost for the employer. The average tax wedge measures the extent to which tax on labour income discourages employment. This indicator is measured in percentage of labour cost. The OECD average shown here is the unweighted average of OECD jurisdictions for the average earner.

Source: (OECD/IDB/CIAT, 2016[10]), (OECD, 2014[21]).

The tax burden, however, must also be considered within the broader labour market context. Given the high turnover rate between formal and informal employment, increasing the tax burden could create additional incentives for individuals to not work in the formal sector and could ultimately result in lower overall contributions to the pension system.

Automatically enrol individuals to contribute higher amounts in the SPP

As an alternative to mandatory contributions, automatic enrolment of individuals into saving in a pension scheme has been gaining traction in many countries as a way to increase participation in the pension system through soft-compulsion. The success of this mechanism relies on the behavioural bias of inertia, taking advantage of individuals’ tendency to follow the path of least resistance, while allowing the individual to opt-out if they do not want to participate. Automatic enrolment schemes have been implemented in ten OECD jurisdictions. The only jurisdiction that has targeted informal employees for automatic enrolment is Chile (OECD, 2019[22]).

The success of automatic enrolment has been varied. Jurisdictions where it seems to have been more successful include New Zealand and the United Kingdom, who have experienced opt-out rates of 17% and 10%, respectively. Other jurisdictions have experienced much higher opt-out rates, however. In Chile, 78% of the self-employed workers opted out of the scheme in 2018, and this rate has been increasing over time. Furthermore, 79% of those contributing by default contribute only once, suggesting that over time individuals have learned to opt-out of contributing (Superintendencia de Pensiones de Chile, 2018[23]). Opt-out rates are also very high in Turkey, at around 60%, as well as in Italy (OECD, 2018[20]).

The reasons for the high opt-out rates in Italy and Turkey seem to be linked to the existence of competing schemes. In Italy, employees have to choose whether their contributions will remain in the pension savings scheme or go towards the previously existing severance pay scheme. In Turkey, the automatic enrolment plans are supplementary to existing personal pension savings.

This experience suggests that while automatic enrolment may not be the best option for Peru to increase contribution levels of self-employed workers, it may be useful to increase the level of contributions for those already required to contribute. For informal workers, the experience of Chile suggests that it is not as effective in a system that is similar to Peru, both in design and the prevalence of labour market informality. However, for formal workers, automatic enrolment would be additional savings on top of the mandatory contributions. Nevertheless, given the tendency for individuals in Peru to fully withdraw their pension assets as soon as they are able to, it seems likely that opt-out rate for automatic enrolment would also be high. This policy would therefore only be effective at increasing contributions for a small portion of the population, so the costs of implementation would need to be considered against the expected benefits.

Improve accessibility and incentives for voluntary contributions

Improving the incentives that individuals have to contribute can lead to higher voluntary contributions. Currently, there are virtually no incentives for an individual to make voluntary contributions to their pension account. In addition, even if they wanted to make additional contributions, not all Peruvians are allowed to do so.

First, all individuals who would like to voluntarily save in a pension account should be allowed to do so. Currently, only individuals enrolled in the SPP are allowed to have a voluntary pension account. In addition, individuals not having been enrolled in the SPP for at least five years are not allowed to make voluntary contributions.

Second, financial incentives for contributing to pension accounts could be improved. Currently, the financial advantage from advantageous tax treatment is limited in Peru. While contributions for formal workers are mandatory, providing better financial incentives could not only help to provide incentives for additional voluntary contributions, but also to mitigate the incentives to work informally by providing some financial benefit for making mandatory contributions.

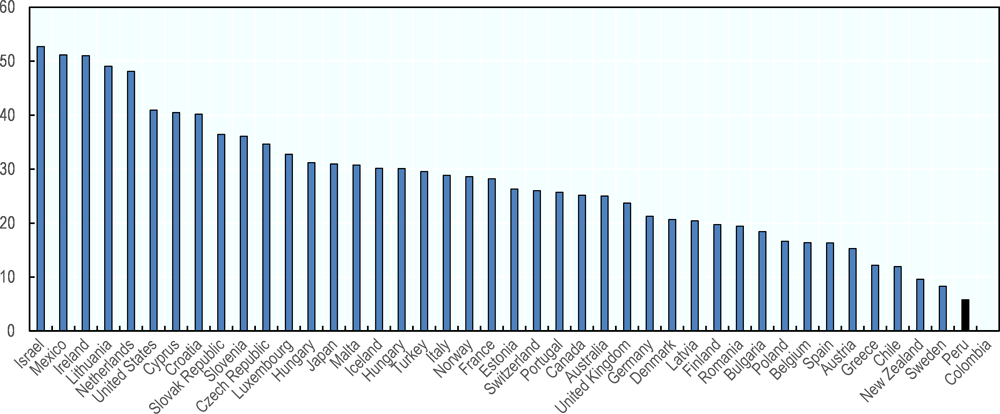

The advantageous tax treatment of pension savings can provide an incentive for individuals to contribute more to their pension accounts, thereby increasing the ultimate pension benefits that they will receive. In Peru, the tax treatment of all contributions to the pension system is “TEE” (taxed, exempt, exempt), that is contributions are taxed as income but the investment income is not taxed, nor are the assets withdrawn for retirement regardless of the form in which they are taken (programmed withdrawal, lump-sum, etc.).

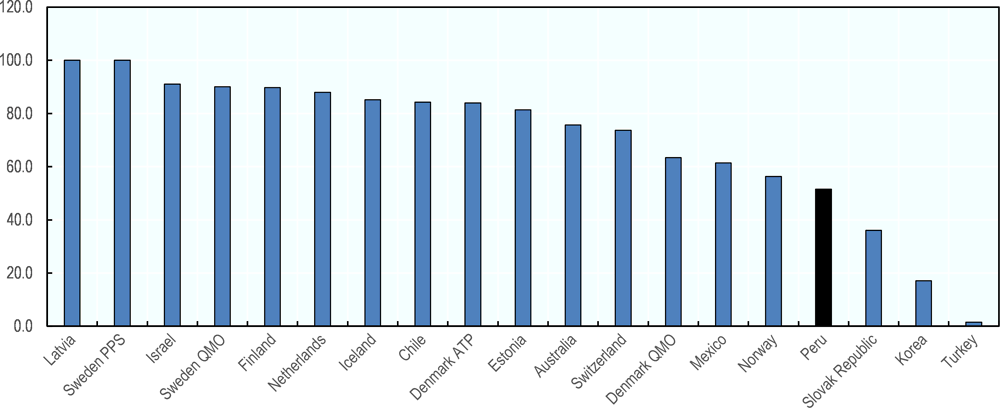

The “TEE” tax treatment provides a financial advantage for pension savings, because compared to saving in a regular savings product, individuals will not have to pay tax on the investment income earned. For normal savings and investment vehicles, as well as voluntary pension savings, individuals owe a tax of 5% on dividends received, and 6.25% on investment income after taking a 20% deduction on gains. This implies that an individual contributing to their mandatory pension savings in the SPP from the age of 20 until they retire at age 65 will have an expected financial advantage amounting to 5.8% of the present value of their total contributions to the plan compared to someone with a voluntary savings account.4 However, this tax advantage for average earners in Peru is lower than all OECD countries, shown in Figure 5.19.

Figure 5.19. Overall tax advantage for the most prevalent funded pension plan in each jurisdiction

Note: The calculations assume that the average earner enters the labour market at age 20 in 2018 and contributes yearly until the country’s official age of retirement at a rate equal to the minimum or mandatory contribution rate fixed by regulation in each country or 5% of wages in the case of voluntary plans. The total amount of assets accumulated at retirement is converted into an annuity certain with fixed nominal payments. Inflation is set at 2% annually, productivity growth at 1.25%, the real rate of return on investment at 3% and the real discount rate at 3%.

Source: (OECD, 2018[24]).

The “TEE” tax regime for pension savings in Peru is tax neutral in the sense that it does not provide a disincentive to save, and individuals should be indifferent between saving and consuming given an expected return that is equivalent to the risk-free rate. Additionally, since individuals are taxed up front on their contribution and are able to withdraw all assets accumulated tax-free, the relative financial advantage does not vary across income groups as a percentage of post-tax contributions to pension accounts. However given the progressivity of the income tax rates, this advantage declines slightly with income when considering the advantage as a proportion of pre-tax contributions (Figure 5.20).

Figure 5.20. Tax advantage of tax and non-tax financial incentives in Peru

Notes: Subsidy is not indexed over time. The label ‘5% matching’ means that the individual contributes 5% and the State contributes the same amount, 5%, which correspond to a match rate of 100%.

Source: Own calculations.

The main disadvantage of TEE taxation compared to EET (exempt, exempt, taxed), where contributions are exempt and withdrawals taxed, is that the EET system provides an immediate reward to individuals from making contributions, whereas this reward is delayed for a TEE system. However, shifting from a TEE system to an EET system is very costly, and would imply a significant loss in fiscal revenue in the short term.

Alternatively, financial incentives for pensions could be increased through the use of a matching contribution or a flat subsidy that would be paid directly into the pension account of the saver. These types of incentives have the advantage of benefitting lower income groups more than higher income groups, and being easier for people to understand than other types of tax incentives because the amount is known and is paid directly into the pension account. Furthermore, even low-income groups who do not pay taxes can benefit from these types of incentives.

In Peru, introducing financial incentives that benefit those with lower incomes more would make sense because these individuals are those that most need to save for retirement, and are also the individuals more likely to be in informal employment. The likelihood that individuals are not doing anything to financially prepare for their retirement increases inversely with income and age, so these individuals could especially use some encouragement to save more into the pension system (Superintendencia de Banca, Seguros y AFP del Perú, 2016[25]).

Flat subsidies are relatively more advantageous to low income groups than matching contributions, as the flat subsidy represents a larger proportion of contributions as income levels decrease. Figure 5.20 shows that the tax advantage from a flat subsidy of 1% of the average wage for the lowest income group shown, earning 20% of the average salary, is 35% of the present value of their contributions. This compares to an advantage of 10.8% of the present value of contributions for the lowest income group of a matching subsidy providing a 5% match of contributions made. The matching contribution also benefits lower income groups more, but the difference is less significant. The financial advantage from the subsidy declines significantly as income levels increase, reaching the level of the matching contribution for individuals earning around 1.2 times the average wage.

Evidence shows that these types of non-tax financial incentives can be effective in encouraging contributions to voluntary pension arrangements, in particular for low income individuals. Coverage of private pensions for low-income individuals in Germany has increased through the Riester plans, which offer a flat-rate subsidy. Matching contributions in Australia have contributed to increased voluntary contributions by low-income groups, though not necessarily increased coverage. Both subsidies and matching contributions for the KiwiSaver plans in New Zealand have helped to promote equal coverage of these schemes across all income groups (OECD, 2012[19]). In Mexico, voluntary contributions have increased in the Solidarity Savings Programme as a result of matching contributions (OECD, 2016[26]). Of these examples, Australia and Mexico offer perhaps the most relevant comparisons for the case of Peru. The matching contributions offered in both of these jurisdictions is for voluntary savings on top of existing mandatory savings, though in Australia the mandatory contribution is fully paid by the employer and in Mexico the plans are only available for public sector workers. Table 5.8 summarises the jurisdictions that offer non-financial incentives for retirement savings.

Table 5.8. Government provided non-tax financial incentives, 2018

|

|

Matching contributions (match rate) |

Fixed nominal subsidies |

|---|---|---|

|

OECD countries |

Australia (50%), Austria (4.25%), Chile (50% or 15%)1, Czech Republic (scale), Hungary (20%), Mexico (325%)2, New Zealand (50%), Turkey (25%), United States (50% to 100%)3 |

Chile, Germany, Lithuania, Mexico, Turkey |

|

Selected non-OECD countries |

Colombia (20%), Croatia (15%) |

1. Chile has two different matching programmes, one for young low earners (50% match rate) and one for voluntary contributors (15% match rate).

2. The matching programme for Mexico only applies to public sector workers.

3. The matching programme for the United States refers to the Thrift Savings Plan for federal employees. The first 3% of employee contribution is matched dollar-for-dollar, while the next 2% is matched at 50 cents on the dollar.

Source: (OECD, 2018[20]).

To limit the cost of providing these incentives, the incentives could be targeted at specific populations, for example low-income groups and/or young people to encourage them to start contributing. Such measures could be particularly valuable in increasing female participation in the pension system, as although females are less likely to be affiliated with a pension system, those who are affiliated contribute at higher rates than males. To further limit costs, the incentives could be limited in terms of duration, for example matching contributions for only the first five years of contributing. This could be effective to the extent that people who begin contributing are more likely to continue to contribute going forward. A 5% voluntary contribution by the individual, that is matched equally (100% match) by the State and targeted at those earning below the median wage (which is roughly similar for the affiliates of the SPP and the total population), would cost less than PEN 1 billion per year (0.1% of GDP). This cost estimation assumes that the incentive would be successful in getting everyone who had contributed to the system in 2017 to contribute the full match of 5% more of their salary.

Such financial incentives could also be employed to encourage higher density of contributions. Turkey employs matching contributions to a similar effect in order to incentivise individuals to not withdraw assets early from the pension scheme. The government provides a matching contribution of 25% of pension contributions up to a cap plus a flat one-time subsidy for those who do not opt out of the automatic enrolment scheme. However, individuals can only keep the full matching contribution and resulting investment returns if they have contributed for at least ten years and they remain invested in the scheme until the age of 56. The proportion of the matching contribution and returns that they can keep increases in steps along with the number of years they remain in the scheme (OECD, 2018[27]). A similar type of incentive could be employed in Peru to try to increase the rate at which affiliates contribute, with individuals being allowed to keep the matching contribution and related investment returns if they achieve a certain contribution density.

5.3.3. Allow withdrawals of only voluntary contributions for first home

Allowing individuals to withdraw 25% of their assets in the SPP during accumulation to pay for a first home has a significant impact on the level of assets that they will have accumulated at retirement. Nevertheless, saving for the purchase of a home is a key reason for Peruvians to save, with 20% of the population saving to acquire a home (Arellano marketing, 2017[28]). This compares to 22% of the population that aim to save for old age.