Despite its strong clusters and high level of entrepreneurial activity in urban centres, the Hamburg Metropolitan Region (HMR) faces important policy challenges to economic development, including low labour productivity and human capital. This chapter examines how innovation can enhance economic growth and productivity in the HMR, by looking at key drivers of innovation: (i) education and human capital; (ii) entrepreneurship and dynamic small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs); and (iii) digitalisation.

OECD Territorial Reviews: Hamburg Metropolitan Region, Germany

Chapter 2. Strengthening economic development, innovation and digitalisation in the Hamburg Metropolitan Region

Abstract

Box 2.1. Summary of key findings and recommendations

The Hamburg Metropolitan Region (HMR) has a strong economy with highly developed clusters in a number of economic sectors. However, the region faces important policy challenges to enhance the dynamics of the economy and raise productivity growth. To increase the future competitiveness and resilience of the metropolitan region, policymakers, in close co-operation and consultation with representatives of the regional economy, need to increase efforts to foster innovation as part of a structural shift away from historically dominant sectors towards new emerging technologies and sectors, which will enable the region to thrive in the digital era.

Political fragmentation hampers economic development in the metropolitan region. Each of the four federal states that cover the territory of the HMR pursues independent innovation and digitalisation strategies. Strengthened collaboration can generate new benefit for all of the HMR. While the city of Hamburg is the dominating economic centre of the HMR, it can equally profit from strong surrounding areas. It is in Hamburg’s own interest to assume responsibility for ensuring that the joint economic zone and labour market outside of Hamburg city proper benefit economically from any initiatives that might be taken in order to enhance the city’s competitiveness and ability to innovate.

Overcoming political fragmentation in innovation strategies is a formidable opportunity to drive sustainable economic growth in the entire metropolitan region. A shared focus on clusters as regional development tools and commonalities in the identified economic clusters in sectors such as energy (especially renewable energy), life and health sciences, food industry and maritime industry, give rise to considerable synergies that could benefit the entire HMR in terms of new jobs, greater international competitiveness and well-being.

Boosting human capital and education is a key component of enhancing economic development in the HMR. Policy makers need to support an increase in the low level of research and development (R&D) while also strengthening science-industry linkages that are currently undermined by a mismatch of research and enterprises business needs. Facilitating exchange and collaboration of research institutes and firms from all part of the metropolitan region would yield additional benefits for technology transfer and knowledge creation. A co-ordinated approach could also raise the national and international profile of the HMR, which would boost its capacity to alleviate the widespread skills shortage by attracting skilled workers.

Seizing the full potential of new research facilities should be a priority for policymakers in the HMR. The European X-Ray Free-Electron Laser Facility (XFEL), in conjunction with the German Electron Synchrotron (DESY), opens up unprecedented research opportunities and manifold possibilities for combining research with private sector development. Policy makers from the different federal states that cover the territory of the HMR need to strengthen their co‑operation, especially in improving accessibility by public transport, to take advantage of the economic and social benefits that XFEL and associated applied research in sectors such as material or life sciences can generate.

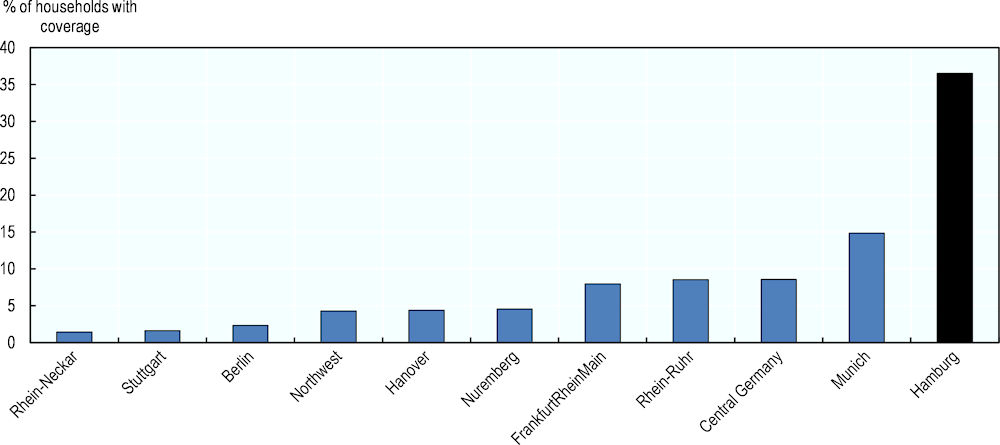

Broadband infrastructure is more developed in the HMR than in other German metropolitan regions. With the right policies, this advantage can enable the region to seize the opportunities that will arise in the digital era. Access to high-speed Internet needs to be sufficiently good in all parts of the HMR. Currently, many rural areas do not have fast broadband Internet access. To ensure inclusive growth in the HMR, policymakers should also strive to provide the widest geographic expansion possible of new generations of cellular mobile communications such as 5G. Embracing digitalisation for public service provision can raise well-being across the entire territory, especially in more remote areas.

Using digitalisation for ongoing projects on intelligent transport solutions has the potential to make the HMR an international leader in the mobility sector, thus further strengthening the regional economy. The ITS (Intelligent Transport System) World Congress in 2021 provides a unique opportunity to enhance mobility and transport solutions in the HMR to increase the welfare of residents and to generate new jobs and growth in a promising economic sector.

Introduction

The Hamburg Metropolitan Region (HMR) is a prosperous region relative to European and OECD standards. Centred around the economy of its largest city, Hamburg, the HMR records high levels of productivity with a gross domestic product (GDP) per employee of more than EUR 75 000 and its citizens enjoy a high quality of life. Over the past decade and especially in recent years, however, economic growth in the HMR has been sluggish. As a consequence, the HMR is falling behind other metropolitan areas in Germany. Between 2005 and 2015, all other ten German metropolitan regions recorded faster growth in GDP per employee than the HMR (Chapter 1).

Historically, the economy of the HMR relied largely on logistics and trade, with Hamburg harbour as one of the major economic pillars of the region that still remains one of the largest employers in the HMR. This puts the region in a comfortable position in order to benefit from rapidly increasing international trade. However, in a globalised world with a gravitational shift of economic activity towards Asia, the HMR now faces fierce international competition in the sectors of port industries, logistics and trade with the rise of Asian mega-ports. Furthermore, there are natural, geographic and environmental limitations to growth for Hamburg harbour and to scaling up maritime trade.

In light of changing patterns of international trade flows, growing international competition in the area of logistics, and rapid technological as well as digital progress that challenges established production and service delivery processes, the Hamburg Metropolitan Region finds itself at a crossroads. The decisions that policymakers implement now and over the coming years will largely determine its development and the future prosperity of its residents.

To fully exploit the opportunities that will arise due to trends such as digitalisation, economic policymaking in the HMR will need to pursue a structural shift. While capitalising on the historically dominant sectors of maritime industries, trade and logistics, a rapid and strong move towards a more innovative economy can provide the conditions for the HMR to thrive in the digitalisation era. Although those sectors will remain major assets for the economy of the HMR, a fundamental reorientation of economic policies is needed.

Strengthening existing clusters in innovative sectors such as renewable energies, life sciences or aviation could help secure the competitive advantage of the HMR in the global economy. Nascent sectors that offer great innovation potential, for example, smart mobility or material sciences, need targeted and holistic development strategies. A re‑shaped focus on those industries must not supersede traditional strength but can offer a valuable complement to already existing strong sectors. Boosting these innovative sectors will not only help raise productivity in the metropolitan region. It is also a necessary step to ensure the economic sustainability of the regional economy in light of the relative decline of the harbour of Hamburg on the global arena and the gradual recession of the maritime industry.

A reorientation of its economic development strategy can position the HMR to reach its full potential in a rapidly changing economic environment. The objective of economic development can serve as a lever for territorial co-operation in innovation and industrial policies, energy and digitalisation across the HMR. In particular, infrastructure investments across federal state borders and joint projects that exploit the region’s leadership in the sustainable energy sector, most prominently wind energy, could yield major benefits for the entire territory. If the different parts of the HMR join forces, they can use digitalisation as a powerful tool to drive innovation, create new jobs and improve quality of life in the region.

Working together across levels of government and across federal state borders to foster stronger economic development in the HMR can be a catalyst for a forward-looking strategy for the entire region. Aligning initiatives in areas such as digitalisation, smart transport or cluster policies across the constituting parts of the HMR can generate economic returns for the region and help overcome political fragmentation as an impediment to collaborative strategies. Exploiting the mutual benefits of a co-ordinated approach to enhancing economic development through innovation can prove to be a catalyst for designing future joint initiatives across the HMR on topics beyond innovation.

This chapter is organised in four main parts. First, it examines the innovation strategies in the HMR and identifies the major challenges of the metropolitan region in terms of innovation. Second, it analyses existing policies and practices in education and discusses possibilities to enhance human capital in the metropolitan region. Third, the chapter assesses policies to promote entrepreneurship and growth of small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) in the region. Finally, the chapter evaluates the opportunities that digitalisation might create and how policies can help the HMR to make the most of digitalisation.

Strengthening innovation in the Hamburg Metropolitan Region

The economic case for innovation

Empirical evidence highlights the importance of innovation for economic growth and productivity. Over the past 20 years, innovation-driven productivity gains accounted for large shares of economic growth in OECD countries (OECD, 2018[1]). Consequently, innovation-driven growth has become a major objective for policymakers (OECD, 2013[2]) as cities and regions are increasingly competing for innovative firms and individuals. Innovation can consist of fundamental changes such as the development of new technologies as well as the implementation of gradual changes, e.g. a new design (Box 2.2).1

Innovation increases the future viability and sustainability of a regional economy by boosting productivity growth, firm creations and new employment opportunities. But innovation is not only important to enhance economic development; it can also be used as a tool to address social, demographic and environmental challenges, such as ageing, climate change or resource scarcity. Efficiency gains through innovative solutions minimise costs for solving such challenges. Pursuing a concerted innovation strategy raises the competitiveness as well as the resilience of a region as it facilitates adjusting to structural economic or technological changes.

Box 2.2. OECD definitions of innovation

Innovation is multifaceted. The Oslo Manual identifies four types of innovation:

Product innovation: The introduction of a good or service that is new or significantly improved with respect to its characteristics or intended uses, including significant improvements in technical specifications, components and materials, software, user-friendliness or other functional characteristics.

Process innovation: The implementation of a new or significantly improved production or delivery method, including significant changes in techniques, equipment or software.

Marketing innovation: The implementation of a new marketing method involving significant changes in product design, packaging, product placement, promotion or pricing.

Organisational innovation: The implementation of a new organisational method in the firm’s business practices, workplace organisation or external relations.

Source: OECD-Eurostat (2005[3]), Oslo Manual – Guidelines for Collecting and Interpreting Innovation Data, 3rd Edition, OECD Publishing, Paris.

The innovation ecosystem and strategies in the HMR

The Hamburg Metropolitan Region currently does not have a consolidated innovation strategy. Instead, an independent innovation strategy exists in each of the four federal states that constitute the HMR. This fragmentation might explain, or even aggravate, some of the pressing challenges in the region. The region lacks a joint vision and master plan for modernising the economy towards innovative sectors and industries.

Each of the four federal states that compose the HMR has developed a regional innovation strategy following the European Union (EU) approach of smart regional specialisation. All four regional strategies identify policies that support and further build economic clusters as crucial elements for enhancing innovation (Table 2.1). In fact, cluster policies are a key instrument according to the existing regional innovation strategies both in Hamburg and in Schleswig-Holstein (see the section on cluster policies for more details). For example, Hamburg’s innovation strategy “is mainly realised through clusters as strategic initiatives in the relevant key sectors” (BWVI Hamburg, 2014[4]), which clearly define areas of priority on which the bulk of resources for research and innovation is supposed to be concentrated. Similarly, the innovation strategy of Schleswig-Holstein aims to build on “the region’s existing strengths in medical technology, the food industry and (renewable) energy technologies” (Ministerium für Wirtschaft, Arbeit, Verkehr und Technologie Schleswig-Holstein, 2014[5]).

Actively capturing synergies across the federal state innovation strategies in the HMR could yield benefits for the entire HMR in terms of new jobs, greater international competitiveness and well-being. Besides the strong emphasis on sectoral specialisation, all four states emphasise the significance of science-industry linkages and intend to enhance knowledge and technology transfer between higher education institutes (HEIs) and private sector firms (Table 2.1). Furthermore, several of the prioritised economic sectors are common across the different states. For instance, all parts of the HMR highlight renewable energies as a key area for growth. Health and life sciences and maritime industries are other common clusters where the different federal states of the HMR could align development policies to achieve greater critical mass, which is necessary to succeed in competitive economic sectors.2 Finally, all four regional strategies consider the creation of innovation parks and provision of digital infrastructure as key elements.

Table 2.1. Key instruments in regional innovation strategies in the HMR, by federal state

|

Hamburg |

Lower Saxony |

Schleswig-Holstein |

Mecklenburg- Western Pomerania |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Cluster strategies and politics |

Cluster policies |

Cluster strategies and politics |

Identification of future key economic sectors |

|

Boosting R&D expenditure of public and private sector |

Activation of innovation potential of SMEs and crafts |

Focus on key technologies |

Applied research and advancement of technology transfer |

|

Technology transfer between research institutes and the economy |

World-class research with direct knowledge and technology transfer |

Expanding the research infrastructure |

Enhancing innovation, research and development in firms, especially SMEs |

|

Cross-sectoral topics: societal challenges such as climate change and equality of opportunities |

Private sector: firm innovation and entrepreneurship |

Note: Key instruments as identified based on the delineated innovation strategy papers. The list does not make any claims of completion but presents instruments that appear to stand out the most in the respective strategy.

Sources: BWVI Hamburg (2014[4]), Regionale Innovationsstrategie 2020 der Freien und Hansestadt Hamburg, https://www.hamburg.de/contentblob/4483086/c1e24c0eeb1ef963a9244e7848f3057d/data/exantedoku-innovationsstrategie-fhh-final.pdf;jsessionid=1D51AF941E9E8633DB744389488E987D.liveWorker2; Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania (2014[6]), Regionale Innovationsstrategie 2020 Mecklenburg-Vorpommern; Ministerium für Wirtschaft, Arbeit, Verkehr und Technologie Schleswig-Holstein (2014[5]), Innovationsstrategie des Landes Schleswig‑Holstein, http://www.schleswig‑holstein.de/DE/Fachinhalte/F/foerderprogramme/MWAVT/Downloads/regionale_innovationsstrategieNEU.pdf?__blob=publicationFile&v=3; Niedersachsen (2014[7]), Niedersächsische regionale Innovationsstrategie für intelligente Spezialisierung.

The regional innovation strategies in the HMR lack a clearly defined plan with respect to some pressing social and economic issues or only address them in a rudimentary manner. Geographic discrepancies within federal states are barely addressed. In particular, the divide between rural and urban areas in terms of innovation activities and innovation infrastructure is not considered explicitly. Furthermore, a holistic innovation vision for the metropolitan region is missing, even though it could connect different economic sectors and provide solutions to societal challenges such as the transition to a low-carbon economy. Leveraging the geographic conditions of a coastal location for building a strong renewable energy sector that helps to manage the German energy transition could provide the foundation for a broad innovation vision for the HMR. Targeting investment in innovation capability and infrastructure in rural areas can help alleviate the strong economic divide between rural and urban areas in the HMR documented in Chapter 1.

The four innovation approaches differ in a number of areas. While all four federal states recognise the importance of the private sector for increasing innovation, the regional innovation strategies in Lower Saxony and Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania particularly underline the need to promote research, development and the uptake of new technologies and production processes in SMEs. The differences in the four innovation strategies also arise because the HMR only covers part of Lower Saxony, Schleswig-Holstein and Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania. The fact that the HMR does not include the state capitals of Lower Saxony and Schleswig-Holstein can also explain differences in the innovation strategies. Nonetheless, common economic and social interests would justify a closer alignment of innovation policies in the different regions of the HMR.

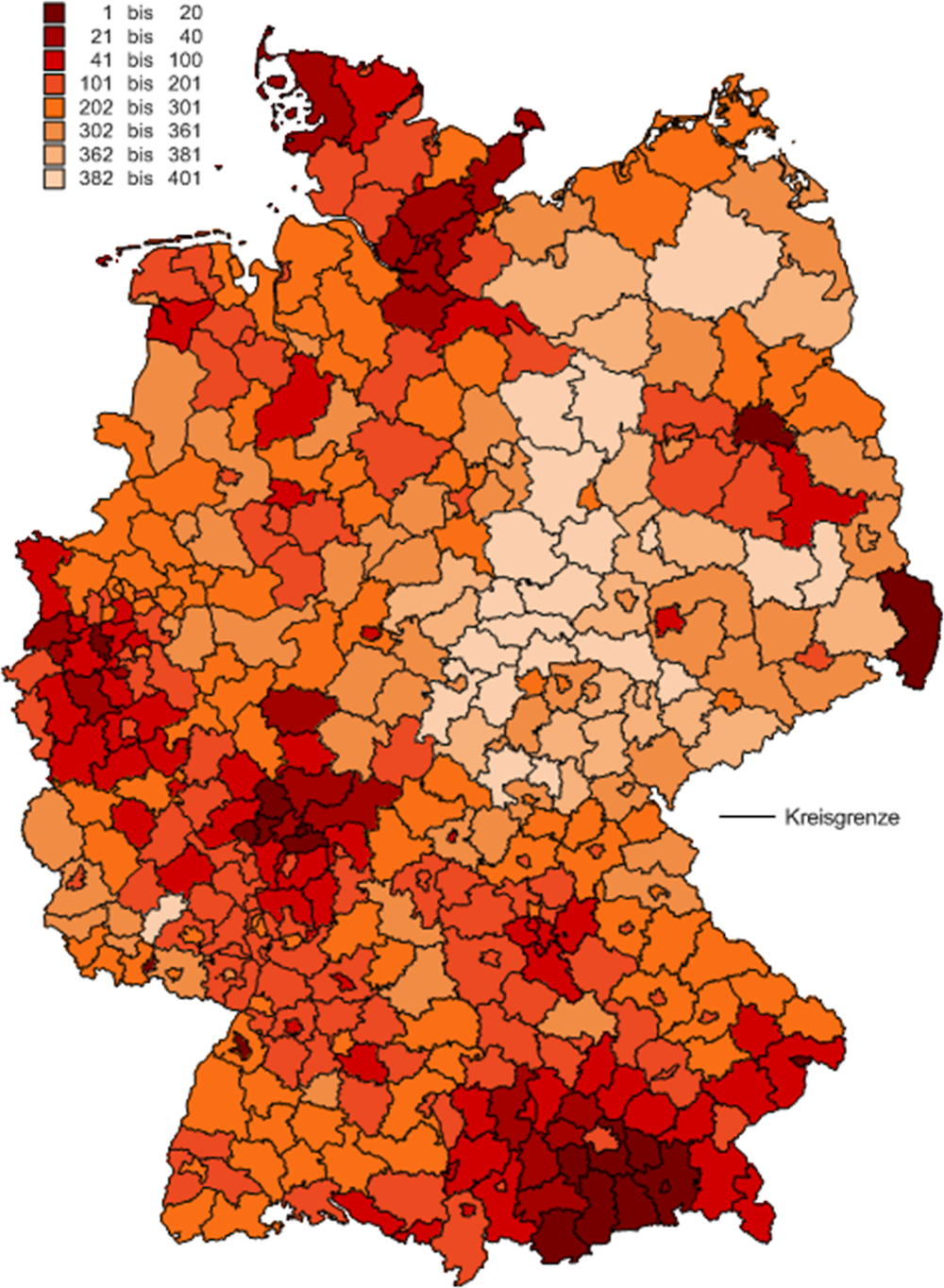

Key challenges to innovation in the HMR

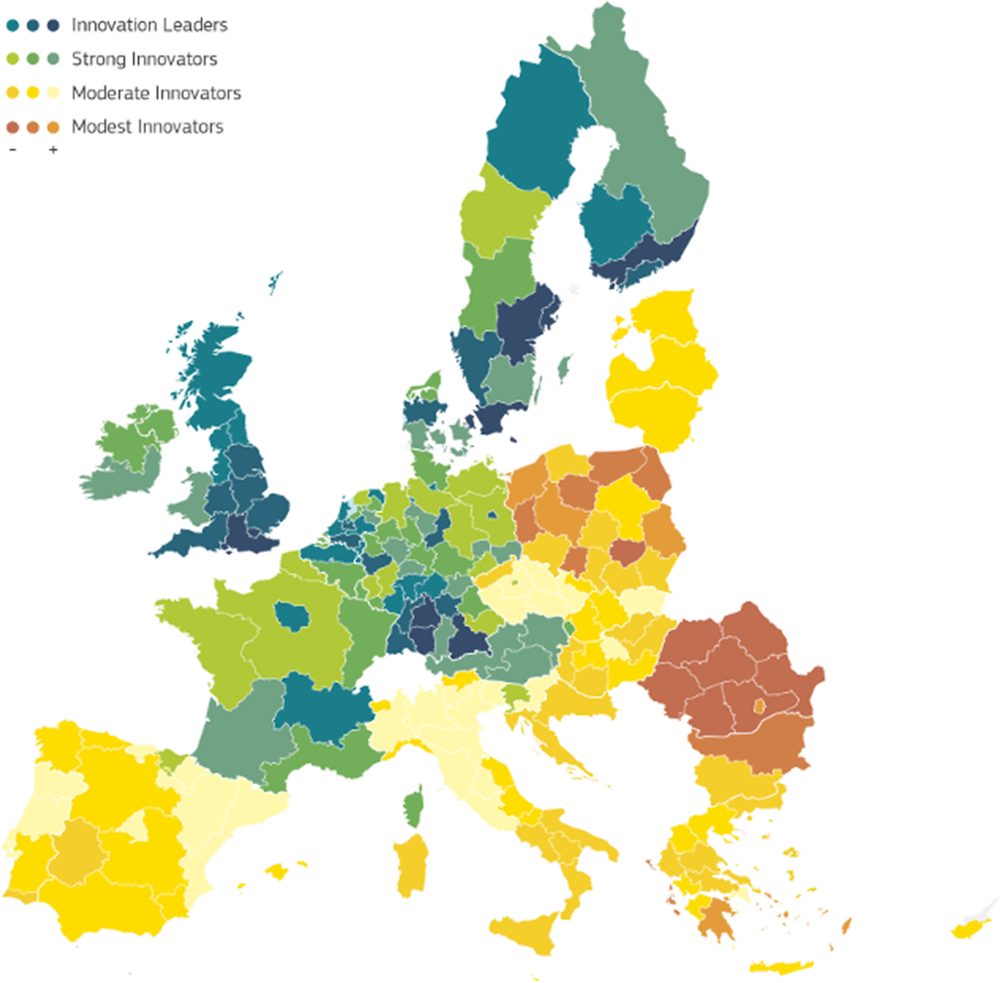

The fragmentation into the four regional innovation strategies leaves significant scope for improvement in enhancing innovation in the HMR. Only the state of Hamburg is among the 25% most innovative European regions as ranked by the European Regional Innovation Scoreboard (Figure 2.1). The other 3 states are among regions with innovation scores between 90% and 120% of the EU average. These relatively favourable international rankings of the different states that make up the HMR mask their actual innovation performance. Compared to other German states (or regions in Scandinavia and the Benelux countries), the HMR lags behind the national innovation leaders as many areas of West and South Germany record higher innovation scores (European Commision, 2017[8]). Within Germany, there is a significant difference between the HMR and southern German metropolitan regions in terms of innovation performance, notably in patent applications, public-private co-publications and innovation in SMEs (see Chapter 1). In comparison with international regions of similar size, the HMR falls behind innovation leaders such as Copenhagen, Gothenburg or Rotterdam (see Chapter 1).

The current regional innovation strategies and policy practices reveal a number of significant shortfalls concerning both the private as well as the public sector:

Technology and innovation transfer are a major problem in the HMR. The majority of enterprises in the HMR are small and lack the resources and capacity to invest in R&D. Additionally, public research and the needs of the local economy in the HMR are not aligned with each other as most research activities do not match the specific demands (e.g. in terms of technologies or production processes) of local enterprises, as confirmed by numerous stakeholders from the private sector and Chambers for Commerce and Industry.3 The lack of research targeted to the needs of SMEs hampers technology transfer and thus a widespread diffusion of innovation in the metropolitan region. Co-operation between higher education research and the regional economy across the entire territory of the HMR needs to be intensified.

Figure 2.1. Regional Innovation Scoreboard 2017, EU

Note: The innovation score is a composite indicator consisting of indicators on framework conditions, investments, innovation activities and impacts.

Source: European Commission (2017[8]), Regional Innovation Scoreboard 2017, http://dx.doi.org/10.2873/469382.

Digitalisation poses imminent challenges to firms and workers across the HMR. Three out of the four federal states that cover the HMR experienced an increase in the share of jobs at high risk of automation between 2011 and 2016 (OECD, 2018[9]). Given the rapid rise of new forms of technology, the increasing automation of work processes and the changing nature of work, policymakers in the HMR need to equip their labour force with the adequate skills (see Section Ensuring social mobility and inclusion through education for more detail). So far, representatives of labour unions and smaller enterprises lament the fact that there are few initiatives exist to ensure that no employee is left behind. Training and upskilling opportunities for experienced employees are limited. Furthermore, a lack of access to high-speed Internet hampers innovation in rural areas of the HMR and constrains the provision of digital services in remote areas further away from Hamburg.

Regional fragmentation undermines the effectiveness of existing innovation strategies. For example, the objective of boosting science-industry linkages is defined within federal state boundaries of Hamburg, Lower Saxony, Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania and Schleswig-Holstein respectively. There are no established networks between higher education institutions (HEIs) and public research institutions (PRIs) from all parts of the HMR with private sector firms. While several cross-regional cluster initiatives exist, more could be done to realise the economies of scale by region-wide collaboration in areas of mutual interest, as documented by the overlap between regional clusters.

Another factor holding back the private sector’s contribution to innovation and thus economic growth is R&D investments:

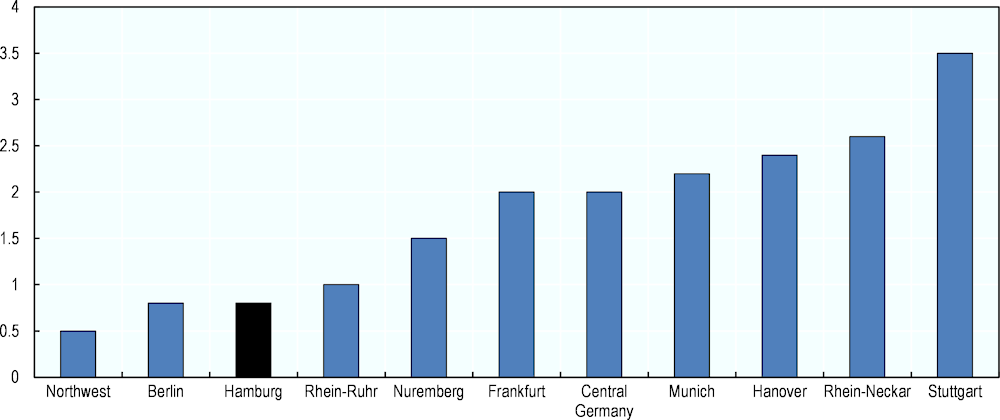

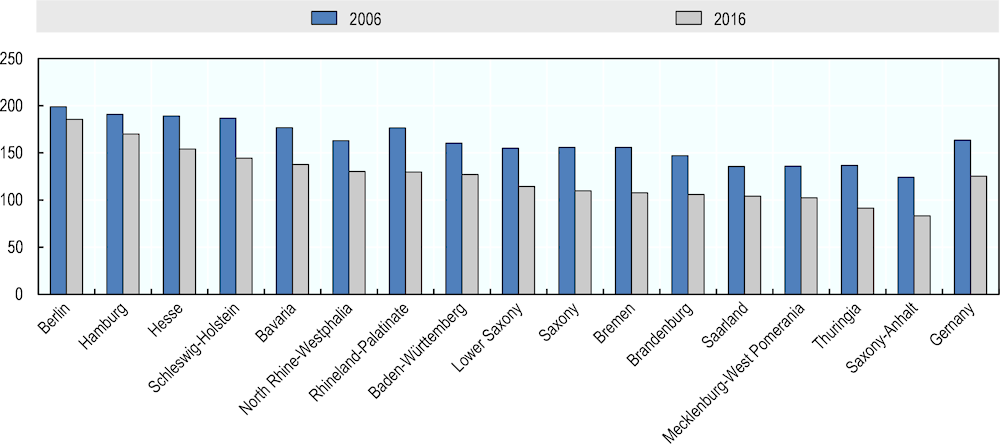

Expenditure on research and development by private sector firms is low in the HMR compared to other metropolitan regions in Germany. There is only one DAX market index company headquartered in the HMR. The lack of headquarters of large enterprises in the Hamburg Metropolitan Region partially explains the low level of R&D expenditure in the region, which falls strikingly short of the EU target of 3% of GDP (Figure 2.2). With R&D expenditure equivalent to only 0.8% of GDP, the research intensity in the HMR is the second lowest among the 11 German metropolitan regions. Firms point out a scarcity of funding for private sector research and development that holds back investment in innovation. Compared to other economic centres in Germany such as Berlin, Frankfurt or Munich, according to local stakeholders, there is a lack of alternative sources of funding for private sector innovation such as venture capital, which constrains small businesses and inhibits entrepreneurship.

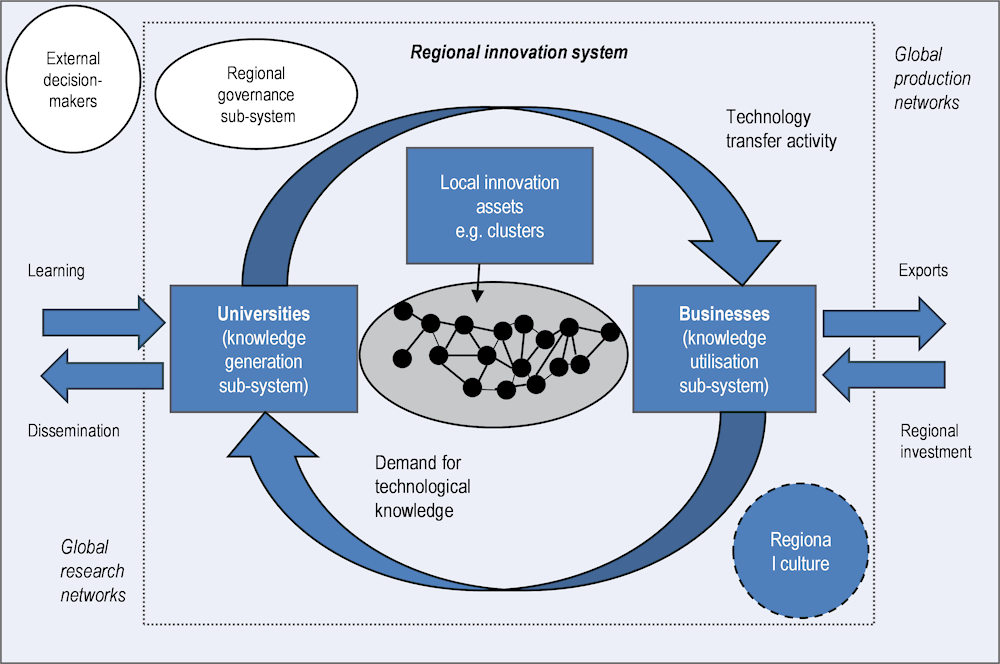

In order to address these challenges, the HMR needs to enhance its innovation ecosystem by attracting more R&D investments, fostering knowledge dissemination, and strengthening the interaction of firms, universities and policymakers. Regional innovation environments, so-called innovation ecosystems, need to ensure a close interaction among a variety of actors (Figure 2.3). Innovation is a product of linkages and co-operation between numerous public and private actors, ranging from individuals such as entrepreneurs to institutions (government, universities, research centres, start-ups, big firms) (OECD, 2018[10]). Rather than being geographically constrained, regional innovation networks sustain and extend such linkages beyond the regional borders.

Figure 2.2. Private sector R&D expenditure as percentage of GDP in metropolitan regions

Notes: Figures take into account the exact geographical borders of regions, by aggregating observations over districts they are composed of.

Berlin = Capital Region of Berlin-Brandenburg; Northwest = Bremen-Oldenburg in the Northwest; Frankfurt = FrankfurtRheinMain; Hanover = Hannover Braunschweig Göttingen Wolfsburg.

Source: Own calculation based on Federal Institute for Research on Building, Urban Affairs and Spatial Development (n.d.[11]), INKAR online: Indikatoren und Karten zur Raum‑ und Stadtentwicklung, http://www.bbsr.bund.de/BBSR/DE/Raumbeobachtung/InteraktiveAnwendungen/INKAR/inkar_online_node.html (accessed on 18 December 2018), latest available data at the district level on shares of firms by firm size from 2014 and on research and development personnel and investments from 2009.

Better co-ordination of innovation policy across federal state borders could alleviate some of the existing challenges in the HMR and yield significant economies of scale. By collaborating, the stakeholders from the four federal states that cover the territory of the HMR can reach a wider territory, better pool their assets and achieve greater critical mass. This critical mass is particularly important as the Hamburg Metropolitan Region is facing competition from more populous metropolitan areas, or international metropolitan areas that have high R&D spending and region-wide innovation co-operation, such as Boston or Rotterdam-The Hague (OECD, 2013[2]). HMR-wide collaboration can establish larger business and knowledge networks, helping in particular SMEs overcome their size-related impediments to innovate and become more productive.

Project-based collaboration such as the North German Energy Transition (NEW 4.0) could provide a starting point for more integrated innovation policies in the metropolitan region. By aligning innovation policies and addressing existing challenges to innovation, policymakers in the region could generate considerable returns to scale. For example, the project NEW 4.0 illustrates how co-operation across federal state borders can provide a more holistic approach to innovation in the region (see Box 2.3). Jointly, the different stakeholders of the HMR could also better boost essential drivers of innovation (Section Drivers of innovation).

Figure 2.3. Regional innovation ecosystems

Sources: Benneworth, P. and A. Dassen (2011[12]), “Strengthening Global-Local Connectivity in Regional Innovation Strategies: Implications for Regional Innovation Policy”, https://doi.org/10.1787/5kgc6d80nns4-en, based on Cooke, P. (2005[13]), “Regionally asymmetric knowledge capabilities and open innovation: Exploring „Globalisation 2” – A new model of industry organisation”, Research Policy, Vol. 34.

Box 2.3. NEW 4.0 – A joint innovation strategy

The initiative North German Energy Transition (NEW 4.0) provides a good example of an innovation strategy across administrative federal state borders in the HMR. Aiming to proactively address the German energy transition and decarbonisation, NEW 4.0 brings together actors from the private sector, research and the public sector in the states of Hamburg and Schleswig-Holstein. As part of this project, these different actors join forces to demonstrate how the entire region can be supplied with 100% renewable energy by 2035 in a safe, reliable and socially acceptable manner.

By realising significant reductions in CO2 emissions, the project aims to contribute to making the regional economy more sustainable. It places particular emphasis on technological solutions for reaching this objective. As part of the Fourth Industrial Revolution, it intends to boost and utilise the digitalisation of the industry and a more intelligent integration and cross-linking of systems. The project connects 60 partners in the region and runs from 2016 to 2020. The Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Energy (BMWi) supports it with approximately EUR 46 million in the framework of the funding programme “Showcase Intelligent Energy – Digital Agenda for Energy Transition”. The total investment volume of partners of the initiative amounts to around EUR 130 million.

Multiple projects illustrate how NEW 4.0 works on finding new energy solutions while also supporting the creation of an integrated cross-regional network. For example, different types of firms collaborate on a project that aims to better link wind energy facilities with energy storage technology in order to increase the stability and reliability of the energy grid. An inter-regional alliance of higher education institutions (HEIs), Chambers of Crafts and Chambers for Commerce and Industry focuses on offering new or better education or training programmes for workers in the energy sector in Hamburg and Schleswig-Holstein.

NEW 4.0 offers great innovation potential for the entire north German economy. Especially the Hamburg Metropolitan Region, as one of the leaders in the renewable energy industry in Europe, stands to benefit from investing and further strengthening this economic cluster. NEW 4.0 might offer a promising approach for increasing the future economic competitiveness of the metropolitan region.

Source: Norddeutsche EnergieWende (n.d.[14]), NEW 4.0, http://www.new4-0.de/.

The case of the metropolitan area of Rotterdam-The Hague offers an interesting example of how regional co-operation can yield a holistic approach to innovation supported by regional innovation funds (OECD, 2016[15]). Rotterdam-The Hague pursues a triple helix framework for enhancing innovation and economic development in the region (see Box 2.4). The triple helix framework in Rotterdam-The Hague ensures a close interaction of firms, universities and the public sector in promoting a strong regional innovation system. A politically autonomous corporation manages the regional development strategy, which facilitates pursuing development projects in a region that consists of a multitude of different entities (e.g. municipalities, districts, etc.). A dedicated regional development corporation, similar to the InnovationQuarter in Rotterdam-The Hague, combined with a joint regional innovation fund could alleviate the existing of cross-border collaboration and co-ordination that impedes innovation in the HMR. Following such a focused approach on enhancing the innovative capabilities of SMEs would also contribute to raising productivity in the HMR, allowing it to catch up with leading metropolitan regions in Germany and the OECD.

To initiate closer region-wide economic and innovation collaboration, the office of the HMR could aim to establish a platform for exchange on innovation-related issues and projects. A key issue that harms the HMR’s competitiveness is the lack of co-operation and information sharing across federal state borders. In contrast, the office of the metropolitan region Rhein-Neckar, which also consists of districts (Landkreise) from several federal states, has created a new job position of an innovation manager who works for the entire metropolitan region. Adopting a similar initiative would benefit the HMR as an innovation manager would facilitate the exchange between the different innovation actors from all parts of the region and help stimulate new collaborative projects. The innovation manager could thus support streamlining innovation initiatives in the metropolitan regions and provide a platform that connects private sector activities with research projects at research institutes in the HMR. Local enterprises would play a key role in ensuring that the introduction of an innovation manager would be a success. In Rhein-Neckar, stakeholders from the regional economy drove the process of establishing the position as they recognised the potential for their own line of business.

Box 2.4. Rotterdam-The Hague – A regional triple helix strategy

The metropolitan area of Rotterdam-The Hague has set up a formal mechanism to foster innovation through regional collaboration. InnovationQuarter, a regional development corporation, works in close co-operation with all major corporations, educational and research institutions and government in West Holland. The regional development corporation works for the entire region. Its mission is to strengthen the regional economy by supporting and stimulating the innovation potential of the region.

InnovationQuarter has far-reaching autonomy. The company is publicly owned but the various municipal governments share power and are not involved in daily operations. This autonomy allows the corporation to pursue strategies that generate the greatest benefit to the regional economy without strong political interference. Additionally, InnovationQuarter manages funds for investments into innovation-enhancing projects and enterprises. In total, the investment capital amounts to EUR 140 million.

The development corporation works to actively promote the region, attract foreign companies and investors and support them in finding the right locations and facilities for setting up or expanding business. It encourages entrepreneurship, invests in fast-growing companies and supports technological initiatives with social impact. On a daily basis, InnovationQuarter offers: i) detailed information on regional and national regulation; ii) extensive networks; iii) site selection support; iv) R&D matchmaking services; and v) investor relation and funding advice.

Source: InnovationQuarter (n.d.[16]), Homepage, https://www.innovationquarter.nl/en/.

Drivers of innovation

To make the regional economy more innovative, policymakers in the HMR should pursue action in three key areas that are associated with innovation and that need to be strengthened in the HMR (OECD, 2015[17]):

1. The HMR scores low in comparison to other German metropolitan regions with respect to human capital (Chapter 1). Although education and human capital are a requirement to build a skilled workforce, university student enrolment and the share of tertiary-educated employees are relatively low in the HMR (Section Boosting education and human capital). Skilled workers can help develop new ideas, conceive new technologies, implement those ideas and make them commercially available. Policy makers in the HMR need to revise established education policies to: i) address skills shortages and labour market skills mismatching that are key concerns for enterprises in the region; and ii) enable the workforce to adapt to technological and structural changes, given the high risk of automation of jobs in the HMR.

2. Innovation requires a strong business environment that incentivises investment in technology and knowledge-based capital, especially since firm investment in R&D in the HMR is critically low. Policymakers in the HMR should also encourage entrepreneurship and support growth and scaling up of new firms, especially in rural and remote areas of the HMR. Promising clusters and industries in the HMR, such as renewable energies or material sciences, should receive further support to strengthen the business environment in the HMR. Examples such as Kompetenzzentrum neue Materialien und Produktion, competency centre on material sciences, illustrate the potential of inter-regional co-operation in clusters in the HMR.

3. Fostering innovation in the HMR calls for a more efficient approach to knowledge creation and diffusion based on work on fundamental knowledge and science and delivered through a widespread transfer of such knowledge to different parts of society. In the HMR, stronger science-industry linkages should be a key policy priority in order to ensure that innovation delivers benefits to the private sector. Making better use of existing research facilities and fully seizing the potential of XFEL will help spur innovation in the metropolitan region.

4. Pursuing clear internationalisation strategies of public and private R&D activities as well as business clusters can augment the innovation capacity of the HMR. Across the OECD, international co-operation has become extremely important for science and innovation both in terms of the internationalisation of business R&D and innovation and the globalisation of public research systems, including higher education R&D (OECD, 2017[18]). For example, international co-authorship in science and innovation research and international co-patenting account for large parts of innovation output in OECD countries (OECD, 2015[19]; 2016[20]). The relevant actors in the HMR should, therefore, strengthen their ability to stimulate innovation by expanding interaction and joint initiatives with external partners. With this aim, actors in the HMR are advised to seek long-term co-operation with external partners like German and European metro regions on a win-win basis. The close scientific relations and geographic proximity make Greater Copenhagen and the Malmö-Gothenburg-Oslo region ideal partners for a future internationalisation strategy for innovation in the HMR.4

In the following sections, this chapter will assess the status quo of existing policies, pressing bottlenecks, and major challenges in the areas of education and vocational training, business environment and entrepreneurship, digitalisation and smart transport in the HMR. For each of these areas, the key components delineated in the OECD Innovation Strategy (human capital, business environment, research institutions and innovation policies that link innovation and entrepreneurial activities) will be evaluated. These drivers of innovation cannot be viewed in isolation but are interdependent. For example, the rapid digitalisation of the economy constitutes both opportunities and potential challenges for the HMR in terms of the required skills of the workforce, the demands on businesses to remain successful, technological innovation or the links between research and development on one hand and entrepreneurship on the other. Since effective innovation policies need to take into account such complementarities between different pillars of innovation, the analysis presented in this chapter will emphasise potential overlap and complementarities of policies in the various areas of innovation in the HMR.

Boosting education and human capital

Key challenges in education and human capital in the HMR

In terms of education, human capital and research, the regional economy of the HMR needs to address four major challenges to increase its economic and innovation capacity: i) a widespread skills shortage; ii) low R&D intensity; iii) weakly developed science-industry linkages; and iv) ensuring social mobility through education in light of digitalisation and resulting changes to the nature of work. The heterogeneous nature of the HMR gives rise to considerable geographic variation in the extent of these challenges. In particular, the larger urban centres such as Hamburg or Lübeck (but also some medium-sized Kreisstädte, i.e. district capitals) stand in contrast to more rural and remote areas.

Across the metropolitan region, firms increasingly encounter a shortage of skilled workers in the labour market especially in the sectors of health and social care, information and communication, engineering and crafts (Christensen, 2013[21]; Bundesagentur für Arbeit, 2018[22]). The skills shortage is most severe for professions with a vocational qualification in the sectors of crafts or social care but also strongly affects occupations that require tertiary education in the areas of medicine, informatics, software development and STEM (science, technology, engineering and mathematics) (Kompetenzzentrum Fachkräftesicherung, 2017[23]). The relatively low share of tertiary-educated individuals among the labour force in the HMR further exacerbates this issue (Table 2.2). Only 14.4% of the workforce has a higher education degree, placing the HMR 4 percentage points below Munich and the Capital Region of Berlin-Brandenburg, the two leading metropolitan regions in Germany. The labour shortage is not limited to high-skilled workers; firms across the region also struggle to fill vacancies for mid- and low-skilled positions. The relatively low level of human capital poses significant challenges for the HMR, as the skills and knowledge of workers are a fundamental driver of economic growth (Barro, 1992[24]) and a primary determinant of regional differences in economic development as it is essential for firms’ productivity (Gennaioli et al., 2013[25]).

Table 2.2. Educational attainment of the workforce, 2015

Comparison with other metropolitan regions in Germany

|

Region |

Share with a higher education degree |

Share without formal vocational qualification or tertiary degree |

|---|---|---|

|

Munich |

18.9 |

11.2 |

|

Berlin-Brandenburg |

18.7 |

8.9 |

|

FrankfurtRheinMain |

17.9 |

12.5 |

|

Central Germany |

16.5 |

5.9 |

|

Stuttgart |

16.1 |

13.8 |

|

Rhein-Neckar |

15.6 |

13.2 |

|

Rhein-Ruhr |

14.6 |

13.5 |

|

Hamburg |

14.4 (8th highest) |

11.1 (3rd lowest) |

|

Hannover Braunschweig Göttingen Wolfsburg |

13.8 |

11.2 |

|

Nuremberg |

11.9 |

12.2 |

|

Northwest |

10.5 |

12.5 |

Source: Data are provided by the data monitoring portal of the initiative of German metropolitan regions, http://www.deutsche-metropolregionen.org/.

However, the labour and skills shortage varies widely across the different parts of the region. While Hamburg and its surrounding municipalities, where wages are higher and access to services is generally better, attract workers from all over the HMR, other areas further away from Hamburg struggle to find adequate labour. The availability of a wide local pool of adequately skilled workers may be a crucial source of agglomeration in Hamburg, as it reduces search costs in the labour market (Overman and Puga, 2010[26]), however, the geographic divide has created a sense of competition for labour within the region.

The lack of a consistent, region-wide approach to attract, train and retain workers with the necessary skills undermines joint initiatives to fight the skills shortage across the HMR. No coherent strategy to promote the attractiveness of the entire HMR on the international stage exists so far. Vocational training and higher education are in the domain of federal states.5 Despite bilateral agreements between federal states, region-wide cross-border collaboration remains limited. Initiatives to address the skills shortage only focus on parts of the metropolitan region, which might be explained by the perceived competition for workers in the region. To counter the skills shortage, Hamburg has established a database for firms and job seekers that facilitates the matching of firms with individuals with the right skills, providing a good example of projects that extend to other parts of the region.6 Using the brand of Hamburg and its high quality of life (Chapter 3) under the umbrella of HMR could help attract skilled workers and would thus strengthen human capital, which in turn stimulates technological progress and facilitates the adoption of new production processes.

In an economic context that is increasingly based on services and rapidly adjusting to new emerging technological opportunities, a skilled workforce has become one of the most important assets of regional economies. The HMR experiences a shift towards larger reliance on knowledge-intensive tasks that require labour supply of tertiary-educated or vocationally trained individuals. These skilled workers are necessary to help firms and industries in the HMR move up global value chains and succeed in competition with international peers.

Stronger regional co-operation and a joint strategy in the HMR could help address the skills and labour shortage more effectively. Policymakers should seek to enhance educational mobility by creating more flexible entry options into education, both for tertiary education and VET programmes. Among other possible priorities, the different stakeholders in the HMR, ranging from the public sector to the private sector, could work together to increase the share of women in the labour market. While the gender gap in the employment rate in the HMR falls at 2 percentage points significantly below the national gender gap of 6 percentage points, policymakers should aim to increase women’s participation in the labour market to not leave a considerable source of talent and skills untapped. Against this backdrop of a lack of region-wide co-ordination, the office of the metropolitan region organised a regional conference in December 2014 on the topic of skilled workers, bringing together actors from all parts of the region. With the same purpose, representatives from Hamburg and Schleswig-Holstein regularly convene to discuss VET-related issues. Such initiatives and meetings could be a starting point to find more counter the labour shortage in the HMR more effectively.7

The dual education system is of great importance for the regional economy. Postsecondary vocational education and training programmes (VET) are a key asset of the German education system. They do not only provide young adults with the technical skills that firms seek by meeting labour market demand but the schooling part also equips students with transferable skills. VET programmes also contribute to a smooth transition of apprentices from fixed-term contracts to permanent positions, help to reduce youth unemployment and offer students avenues of progression (Fazekas and Field, 2013[27]).

Falling popularity of vocational training will pose new challenges to find the right employees for the majority of firms in the HMR. The vast majority of firms in the HMR consists of SMEs that heavily rely on the German education system of both tertiary education and dual vocational training schemes (Ausbildung). However, over the past two decades, the share of teenagers that start vocational training schemes has substantially fallen due to a significant increase in the share of young adults that pursue tertiary education. This structural shift, often referred to as academisation in Germany, poses a skills match problem for most SMEs that need the skills provided by vocational training to run their operations. For example, in the city-state of Hamburg, the number of unfilled apprenticeships increased by 14% in 2018 (Federal Employment Agency). Enhancing the prestige of vocational education through pilot projects could raise the attractiveness of vocational training and apprenticeships. For example, co-operation between universities for applied sciences and larger firms in the region, comparable to IBM in the Stuttgart Metropolitan Region, or increasing international mobility during VET by making better use of opportunities such as VET-Erasmus could contribute to this objective.

Administrative fragmentation of the training system negatively affects the conditions for apprenticeships in the metropolitan region. Vocational training schemes are organised in each federal state, with the contents of the training being specified by national regulations. The federal states decide where the schools for different professions are located and adapt the topics of the lessons in school to the national schemes. As part of their training, apprentices attend a vocational school several days a week in the state where their enterprise is located.8 This fragmentation can have adverse implications for apprentices. For example, someone living in and working for a firm in a municipality in Schleswig-Holstein that borders Hamburg would be required to travel up to 100 km to Kiel, instead of enlisting in a vocational school in nearby Hamburg. Closer co-ordination to attract young adults could significantly raise the attractiveness of vocational training schemes and thus alleviate the shortage of skilled labour in the HMR. Alternatively, apprentices should receive travel allowances to cover the transport costs to their vocational school.

Research and universities in the HMR

Research and development expenditure in the HMR is significantly below the German average and fails to meet the European R&D target for 2020 of 3% of GDP (Table 2.3). In Hamburg, R&D expenditure only amounted to 2.2% in 2016, compared to 2.9% nationally. Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania and Schleswig-Holstein fall even further below the national average R&D expenditure with R&D expenditure corresponding to less than 1.9% and 1.5% of GDP respectively. While Lower Saxony spends the equivalent of 3.3% of its GDP on R&D, the main universities (Göttingen, Hannover) and largest enterprises (e.g. Volkswagen), which account for the largest part of R&D activities, are located outside the HMR.

The low level of R&D expenditure in the HMR can, at least partly, be explained by a lack of large headquarters of multinational firms in the region, which is particularly striking compared to the south of Germany (see section Promoting a more dynamic business environment and entrepreneurship). Nevertheless, the R&D intensity has substantially improved in various parts of the HMR. For example, R&D expenditure in Hamburg has increased by almost 50% since 2000 (Statistisches Bundesamt). To further improve the R&D environment in the HMR, policymakers could encourage smaller firms to co‑operate by pooling research and development resources. For example, enabling firms to apply for joint research funding, including applications across federal state boundaries, would help SMEs from the HMR overcome their competitive disadvantage due to smaller firm size and could yield higher innovation performance of the private sector.

Table 2.3. Research and development expenditure by the state in the HMR, 2014-16

Expenditure by federal state

|

Internal expenditure for research and development in EUR million |

Share of the GDP in % |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

2014 |

2015 |

2016 |

2014 |

2015 |

2016 |

||

|

Hamburg |

2 453 |

2 423 |

2 513 |

2.34 |

2.20 |

2.22 |

|

|

Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania |

732 |

753 |

759 |

1.87 |

1.87 |

1.85 |

|

|

Lower Saxony |

7 363 |

8 867 |

9 156 |

2.90 |

3.43 |

3.31 |

|

|

Schleswig-Holstein |

1 287 |

1 277 |

1 342 |

1.53 |

1.47 |

1.49 |

|

|

Germany |

84 247 |

88 782 |

92 174 |

2.87 |

2.92 |

2.93 |

|

Note: No further geographic breakdown is available. The numbers for Lower Saxony, Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania and Schleswig-Holstein contain expenditure in areas outside of the HMR.

Source: BMBF (2018[28]), Datenband Bundesbericht Forschung und Innovation 2018, https://www.bmbf.de/upload_filestore/pub/Bufi_2018_Datenband.pdf.

While the metropolitan region lacks world-class higher education institutions (HEIs), recent efforts to strengthen the universities in the HMR have been successful. With its dominant city Hamburg having historically been a trading and business city without a strong tradition in higher education, there is a lack of internationally renowned universities in the metropolitan region. However, in 2018, the University of Hamburg and its partner institutions were very successful at the new “Excellence Strategy” of the German Federal Government and the German States. Four Clusters of Excellence (research clusters) from Hamburg were successful, namely in climate research, photonics and nanoscience, as well as mathematics and particle physics. Such status will offer significant amounts of additional funding to the universities over a period of seven years and will help to foster cutting-edge research in the region. Thus, 4 out of the 57 clusters that will be nationally funded are located in the HMR raising the profile of the region for cutting-edge research.

The void in top-class university and private sector research is partly filled by the presence of public research institutions (PRIs) but research activities need to better align with the needs of local firms. Across the HMR, PRIs contribute significantly to research and development, thus they help to spur innovation. In total, there are three Max Planck Society institutes, three institutes of the Fraunhofer Society and four Leibniz Association institutes in the HMR with research strengths in numerous disciplines (Table 2.4). The HMR is home to two Helmholtz Association research centres with the German Electron Synchrotron (DESY) and the Centre for Materials and Coastal Researchjointly funded by the national government and the federal states. In addition, there are four public non-university research institutes, completely funded by the federal state of Hamburg, including the Hamburg Academy of Science. Despite the breadth of the research disciplines of these PRIs, exchange and co-operation with local firms needs to improve. In order to foster innovation, research of both HEIs and PRIs needs to better match the needs of the firm environment in the HMR (see Section Strengthening science-industry linkages for further discussion).

The new XFEL research facility can be a powerful catalyst for innovation and economic development in the metropolitan region. Located at the border between the federal states of Hamburg and Schleswig-Holstein, XFEL has the potential to elevate scientific research in the HMR to a completely new level. Based on the world’s largest X-ray laser, the research facility will open up completely new research opportunities for scientists and industrial users. XFEL will raise the attractiveness of the metropolitan region for new businesses and international researchers alike. The scope for manifold, new applied research can also boost the creation of new enterprises in the region.

Table 2.4. High-profile public research institutes in the HMR

|

PRI |

Location |

Key strengths |

|---|---|---|

|

Max Planck Society – 3 institutes |

Hamburg |

Structure and Dynamics of Matter, Meteorology, Comparative and International Private Law |

|

Fraunhofer Society – 3 institutes |

1 Hamburg, 2 Schleswig-Holstein |

Additive production technologies, silicon technology, cell technology |

|

Helmholtz Association – 2 research centres |

1 Hamburg, 1 Schleswig-Holstein |

Centre for Materials and Coastal Research, DESY – German Electron Synchrotron |

|

XFEL – European X-Ray Free-Electron Laser Facility GmbH |

Hamburg and Schleswig-Holstein |

Material science, life sciences, physics and chemistry research |

|

Leibniz Association – 4 institutes |

Hamburg and Schleswig-Holstein |

Global and area studies, experimental virology, tropical medicine, pneumology |

Note: The list is non-exhaustive. It is limited to research centres of the Max Planck Society, Helmholtz and Fraunhofer Societies, and other PRIs of significant international reputation and critical size.

Source: Fraunhofer (n.d.[29]), Standortkarte, https://maps.fraunhofer.de/fsk/; Helmholtz (Helmholtz, n.d.[30]) (n.d.[30]), Unsere Forschungszentren im Überblick, https://www.helmholtz.de/ueber_uns/helmholtz_zentren/; Max‑Planck‑Gesellschaft (n.d.[31]), Liste aller MPG‑Institute und ‑Experten mit Suchfunktion, https://www.mpg.de/institute_karte; Leibniz Association (2019[32]), The Leibniz Association ‑ About Us, https://www.leibniz-gemeinschaft.de/en/about-us/.

Supporting the development and growth of XFEL should be a priority for policymakers in the HMR. Large world-class research infrastructure does not only generate economic and financial returns to the local economy; it also contributes to human capital formation through learning, new education and training opportunities, and knowledge spillovers. As the case of CERN (European Organisation for Nuclear Research) demonstrates, the presence of globally leading research facility can also raise the international prestige and recognition of the HMR as an innovation hub (OECD, 2014[33]).

In fully utilising the potential of large research facilities such as XFEL, a region-wide co‑operation across administrative borders is of paramount importance. XFEL provides an example of policymakers from different federal states working together for regional development. The development of XFEL was not only supported by the states Hamburg and Schleswig-Holstein but the research facility is also physically located in both states. By attracting new firms and linking up with existing ones, XFEL can support the cluster formation in life and material sciences in the metropolitan region. However, a lack of transport co-ordination between the two involved federal states currently undermines the potential impact of XFEL. For example, no direct public transport connections exist so far from Hamburg city centre or the international airport to the XFEL facility in Schenefeld (Schleswig-Holstein), reducing its accessibility for international guests significantly. This calls for a better alignment of public transport policies across federal states.

A new research and business hub in Hamburg is a promising development that can tighten the links between scientific research, university education and application for business ideas. The city of Hamburg is planning to construct an international science park in Bahrenfeld, together with the University of Hamburg and DESY (German Electron Synchrotron), to exploit the industrial application potential of DESY and XFEL. The science park will pursue interdisciplinary research and education in physics, chemistry, biology and scientific computing. To make this project a success and to maximise the positive effects for the regional economy, close co-ordination between and integration of stakeholders from different parts of the HMR is a must.

Strengthening science-industry linkages

Universities are becoming more entrepreneurial in many OECD countries. Consequently, the presence of universities and PRIs, and the level as well as the quality of their research activities, contribute to the creation of new enterprises (Audretsch, Lehmann and Warning, 2005[34]; Hausman, 2012[35]). Furthermore, research activities and investments can provide the necessary innovation spillovers that stimulate entrepreneurship. Initiatives such as on-campus business incubators, technology accelerators or spin-offs, can all contribute to the consolidation of existing economic clusters and the development of new innovation-reliant business sectors (OECD, 2018[36]).

While science-industry linkages have become an important policy focus in the HMR, co‑operation between higher education research and the economy remains underdeveloped. Over the past decade, policymakers and business representatives across the HMR have supported the creation of various science and technology parks, which were established with the explicit aim of fostering interaction between firms and HEIs (Table 2.5). These actions have improved science-industry linkages in the metropolitan region but their effectiveness is hampered by a mismatch between research and business needs.9 Closer alignment of research and the requirements of local firms in the HMR would facilitate the transfer and uptake of new technologies and production processes, generating positive innovation spillovers and boost local entrepreneurship.

Table 2.5. Research and innovation parks for technology transfers

|

Park |

Location |

Business sectors |

|---|---|---|

|

Zentrum für Angewandte Luftfahrtforschung (ZAL) |

Hamburg - Finkenwerder |

Aviation |

|

Energie Campus |

Hamburg - Bergedorf |

Energy research and new technologies |

|

Innovation Campus Green Technologies |

Hamburg-Harburg |

Green technologies |

|

Innovation Centre Bahrenfeld |

Hamburg - Bahrenfeld |

Material science, life sciences, physics, chemistry, biology and scientific computing |

|

CFK-Nord Research Centre |

Lower Saxony - Stade |

Lightweight construction, carbon fibre reinforced plastics |

|

Technikzentrum Lübeck |

Schleswig-Holstein - Lübeck |

Photonics, biotechnology, life sciences, 3d printing |

Despite the creation of innovation parks, science-industry linkages face two important challenges. The vast majority of firms in the HMR consists of SMEs that are specialised in specific sectors or niche products. Their needs in terms of applied research are often misaligned with the research at HEIs and PRIs in the region. Therefore, many local enterprises struggle to take advantage of the facilities and research at their disposal and fail to benefit from technology and innovation transfer. Furthermore, the fragmented nature of the business environment hinders the exchange between local firms, especially SMEs and HEIs. Better matching research and business needs could raise the effectiveness of research and innovation parks considerably. The Lüneburg Innovation Incubator associated with Leuphana University provided a positive example of how such difficulties can be overcome (OECD, 2015[37]). The incubator successfully fostered fruitful co-operation with local SMEs, embedding its research agenda in the local economy (Box 2.5).

Box 2.5. The case of the Lüneburg Innovation Incubator

Lüneburg Innovation Incubator was set out to trigger transformational economic change in its region by providing a platform to attract and develop innovative people, firms, research projects, social capital and infrastructures. Key features were:

A substantial group of regionally engaged scientists, start-up companies and research-intensive inward investors were attracted and embedded into a globally connected and open research and learning environment.

In defining a strategic roadmap for the Incubator, Leuphana looked to its own strengths, notably in the area of sustainability studies, and responded to the region’s aims to grow its digital and creative industries, to provide cleaner and more sustainable energy, and to meet the demands of an ageing population.

Co-financed by Lower Saxony and EU, the incubator was based on a portfolio of five measures: i) expansion of regional research capacity through attracting international scientists; ii) growth of employment opportunities in skilled services; iii) development of advanced education and training; iv) project management; and iv) investment in infrastructure.

Regional networking was a key concept of the incubator: it connected Leuphana scientists with a network and co-operation partners, primarily local SMEs. It helped to build knowledge networks through co-operative and knowledge transfer projects with SMEs.

Impact: 12 start-ups, 1 000 jobs created.

Source: OECD (2015[37]), Lessons Learned from the Lüneburg Innovation Incubator, https://www.oecd.org/cfe/leed/FINAL_OECD%20Luneburg_report.pdf (accessed on 19 December 2018).

The positive impact of intensified science-industry linkage is highly concentrated around Hamburg and a few other locations in the metropolitan region. Firms in remote areas of the HMR, i.e. further away from Hamburg and other main locations of technology transfer and research centres, struggle to gain from the knowledge and technological progress created in the region. Greater regional diffusion of science and innovation parks could alleviate such urban-rural differences. The region Västra Götaland in Sweden, for example, has set up an innovation system of science parks that are distributed across the region (OECD, 2018[38]). Locally, each of the six sites has spurred innovation and driven R&D-infused job creation in manufacturing (Box 2.6). A similar approach, which strengthens innovation by creating or enhancing existing science parks across the territory of the HMR, could help boost economic growth in large parts of the metropolitan region.

Box 2.6. The science park system in Västra Götaland, Sweden

Distributing science parks across a region

The Science Park system (innovation system) in Region Västra Götaland is successfully contributing to economic growth in all parts of the region. The system consists of six different sites, spread throughout the region. All six have different specialities linked to the part of the region or location.

The six science parks work together and meet frequently but do not compete. They are owned and supported by actors from the private sector, academia and the public sector. Universities in the region are co-located with the six science parks, i.e. distributed across the territory of the region. While the science parks have far-reaching autonomy, the region invests in the science parks as part of its regional strategy for growth within the objective “A leading knowledge region”.

Jointly, the parks contribute to the regional smart specialisation strategy with their respective focus. They also help address societal challenges in the region such as climate strategy. The science park system in Västra Götaland ensures localised investment and innovation output. Job creation in business services and R&D-driven manufacturing is predominantly located directly in or close to the six sites.

Source: OECD (2018[38]), OECD Territorial Reviews: The Megaregion of Western Scandinavia, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264290679-en.

Ensuring social mobility and inclusion through education

Education does not only fulfil an important role in providing individuals with the skills to participate economically. It also serves as an essential vehicle for social mobility and inclusion. Policymakers in the HMR need to address two challenges to maintain the social mobility function of education and to safeguard a socially inclusive economic development. First, disparities in educational opportunities by socio-economic background need to be reduced. Second, targeted action is required in light of the demands and risks that digitalisation and automation pose for low-skilled workers and economically disadvantaged households.

More than 6% of all high school graduates left school without any qualification or degree in 2016. Out of 58 000 students, almost 4 000 dropped out of school in the metropolitan region (Table 2.6). Even though the school dropout rate is below that of many OECD regions, where early school leavers can make up around 10% of students each year, the associated social and economic costs with such a number of school dropouts remain too high to be ignored (OECD, 2018[39]). It is extremely difficult for young people without qualifications or with low skills to find a job, especially a permanent one, in the post-crisis workplace environment (OECD, 2016[40]). In the HMR, the issue is particularly pressing in Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania, where 9.4% of high school students leave without a formal qualification.

To combat the dependency of educational attainment on households’ levels of education and income, authorities in parts of the HMR are pursuing a number of measures. For example, in Hamburg, a dedicated youth employment agency offers students and young adults guidance and support in their career plans (see Box 2.7). The scheme also supports students in their search for the right training place, the choice of the suitable course of study and aims to offer advice in addressing problems at school or personal difficulties. Hamburg also employs another initiative that aims to close the attainment gap based on socio-economic background. By offering free full-day care at school, the state aims to improve learning conditions for students from disadvantaged families. Similar youth employment agencies also exist in other parts of the HMR such as the districts Dithmarschen and Pinneberg, the district-free city Neumünster (all Schleswig-Holstein), and the districts Cuxhaven, Lüchow-Dannenberg and Lüneburg (all Lower Saxony).

Digitalisation raises new challenges for education’s role in safeguarding social mobility and inclusion in the HMR. The advance of digital technologies in work processes requires more targeted education and training programmes for employees in the HMR. So far, opportunities for continuous training and lifelong learning are not extensive enough and do not reach large segments of the employees in the HMR.10 Currently, too few companies in the HMR offer lifelong learning and training opportunities to their employees that would equip them with the necessary skills to succeed in the labour market. Due to rapid changes to operational processes in businesses and quick, technological progress, the skill sets demanded by companies are changing and as a result, 4% to 40% of jobs in OECD regions are at risk of automation (OECD, 2018[9]).11 In the HMR, policymakers should support Chambers of Crafts, Chambers for Commerce and Industry, vocational schools and universities in jointly devising such training opportunities.12 As digitalisation also facilitates remote access to training opportunities, it should also be exploited to increase lifelong learning provisions in parts of the region where the offer of training is so far limited.

Box 2.7. Hamburg Youth Employment Agency (YEA)

The Youth Employment Agency of Hamburg is directed at adolescents and young adults up to the age of 25, offering advice and support on the choice and preparation of a professional career. The agency supports young adults in looking for the right vocational training place, helps them determine suitable courses of, and helps to address school and personal problems.

The initiative also keeps track of adolescents who are not in an apprenticeship or high school, offers them direct support. Pupils still in a compulsory schooling age register with the vocational school (vocational preparation school) responsible for them after each summer holiday, where they are individually advised by teachers and, if necessary, by the YEA and receive suitable support. Young people no longer subject to compulsory schooling are advised, guided and placed in an apprenticeship by the YEA until they have found a professional perspective.

Since the introduction of the YEA, the retention rates in apprenticeships, as well as other measures, have been regularly surveyed for all school graduates after Year 9 or 10. The number of school graduates immediately starting an apprenticeship has increased significantly since 2012 and remains stable at a high level. Thus, the YEA helped to increase the direct transition to an apprenticeship after Year 10 from approximately 25% in 2012 to 36% to 39% in 2017.

Source: Youth Employment Agency (Jugendberufsagentur) Hamburg (n.d.[41]), Infoportal : What can the JBA Can Do for You, https://www.jba-hamburg.de/English-71.

Table 2.6. Graduates of general education schools in the HMR, 2016

Number of graduates by district and type of degree

|

Total number of graduates of general education schools |

among which |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

without Hauptschulabschluss (lowest secondary qualification) |

with Hauptschulabschluss (lowest secondary qualification) |

with Mittlerem Abschluss (middle secondary qualification) |

with Allgemeiner Hochschulreife (general matriculation standard ) |

||||||

|

total |

female |

total |

female |

total |

female |

total |

female |

||

|

Hamburg Metropolitan Region (HMR) |

57 705 |

3 626 |

1 413 |

8 066 |

3 309 |

20 097 |

9 714 |

25 916 |

13 923 |

|

Hamburg |

16 944 |

992 |

401 |

2 588 |

1 117 |

3 944 |

1 802 |

9 420 |

5 053 |

|

Kreisfreie Stadt Lübeck |

2 395 |

180 |

77 |

347 |

147 |

711 |

342 |

1 157 |

639 |

|

Kreisfreie Stadt Neumünster |

1 494 |

91 |

42 |

198 |

90 |

419 |

202 |

786 |

435 |

|

Kreis Dithmarschen |

1 919 |

159 |

57 |

267 |

104 |

657 |

310 |

836 |

472 |

|

Kreis Herzogtum Lauenburg |

2 236 |

157 |

67 |

340 |

118 |

786 |

398 |

953 |

502 |

|

Kreis Ostholstein |

2 600 |

234 |

90 |

411 |

151 |

943 |

466 |

1 012 |

555 |

|

Kreis Pinneberg |

4 239 |

254 |

106 |

535 |

243 |

1 412 |

727 |

2 038 |

1 062 |

|

Kreis Segeberg |

3 629 |

226 |

74 |

588 |

230 |

1 246 |

627 |

1 569 |

851 |

|

Kreis Steinburg |

1 765 |

127 |

35 |

288 |

128 |

602 |

307 |

748 |

390 |

|

Kreis Stormarn |

2 939 |

132 |

55 |

292 |

108 |

795 |

378 |

1 720 |

891 |

|

Schleswig-Holstein (area within HMR) |

23 216 |

1 560 |

603 |

3 266 |

1 319 |

7 571 |

3 757 |

10 819 |

5 797 |

|

Landkreis Cuxhaven |

2 121 |

142 |

57 |

338 |

129 |

1 153 |

555 |

488 |

265 |

|

Landkreis Harburg |

2 547 |

70 |

29 |

305 |

101 |

1 168 |

573 |

1 004 |

519 |

|

Landkreis Lüchow-Dannenberg |

535 |

34 |

11 |

82 |

41 |

285 |

142 |

134 |

74 |

|

Landkreis Lüneburg |

1 956 |

72 |

33 |

185 |

85 |

946 |

429 |

753 |

375 |

|

Landkreis Rotenburg (Wümme) |

1 960 |

109 |

32 |

203 |

80 |

1 039 |

506 |

609 |

323 |

|

Landkreis Heidekreis |

1 548 |

111 |

40 |

193 |

70 |

809 |

407 |

435 |

253 |

|

Landkreis Stade |

2 216 |

148 |

59 |

275 |

109 |

1 201 |

603 |

592 |

353 |

|

Landkreis Uelzen |

1 019 |

45 |

11 |

138 |

53 |

542 |

243 |

294 |

162 |

|

Lower Saxony (area within HMR) |

13 902 |

731 |

272 |

1 719 |

668 |

7 143 |

3 458 |

4 309 |

2 324 |

|

Kreisfreie Stadt Schwerin |

851 |

101 |

38 |

76 |

35 |

266 |

124 |

408 |

202 |

|

Landkreis Nordwestmecklenburg |

1 225 |

120 |

51 |

199 |

85 |

479 |

234 |

427 |

240 |

|

Landkreis Ludwigslust-Parchim |

1 567 |

122 |

48 |

218 |

85 |

694 |

339 |

533 |

307 |

|

Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania (area within HMR) |

3 643 |

343 |

137 |

493 |

205 |

1 439 |

697 |

1 368 |

749 |

|

HMR without Hamburg |

40 761 |

2 634 |

1 012 |

5 478 |

2 192 |

16 153 |

7 912 |

16 496 |

8 870 |

Note: Graduates of general education schools 2016.

Source: Statistik Nord (2018[42]), Statistik der Allgemeinbildenden Schule, https://www.statistik-nord.de/zahlen-fakten/regionalstatistik-datenbanken-und-karten/metropolregion-hamburg/.

In order to leave nobody behind, policymakers need to provide upskilling opportunities for low-educated and low-skilled employees widely and quickly. According to the Institute for Employment Research (IAB), the exposure to automation risk in the HMR is highest in Lower Saxony (25% of employees in high-risk occupations) and most strongly affect jobs in manufacturing (Dengler, Matthes and Wydra-Somaggio, 2018[43]). By granting the right training opportunities, policymakers can achieve the widest possible participation of the labour force in an economy changed by digitalisation. Policies to address the social impact of digitalisation in the metropolitan region have to place older and less-skilled workers at their centre, groups that appear particularly vulnerable to digitalisation-driven structural changes.

Furthermore, increased upskilling and training opportunities in the HMR could produce positive spillover effects through knowledge sharing (Fritsch and Aamoucke, 2013[44]). These spillover effects are especially pronounced in high-tech sectors that rely relatively more on workers with tertiary education. Therefore, regional differences in the supply of highly skilled workers can give rise to differences in productivity (Moretti, 2004[45]).

Promoting a more dynamic business environment and entrepreneurship