This chapter examines opportunities and challenges in the implementation of the open government principle of transparency in Brazil. It analyses the country's legal framework for access to information (ATI), including the mechanisms and tools for proactive and reactive disclosure and provides an assessment of the institutional framework for ATI. Finally, it assesses the role of the broader transparency agenda to enable stakeholder participation in policy design and decision-making. Throughout, the chapter provides recommendations and reflects on good practices from OECD and key partner countries to help the government of Brazil reinforce a culture of transparency.

Open Government Review of Brazil

7. Transparency for Open Government in Brazil

Abstract

Introduction

Transparency often represents both the underlying motivation for - and the intended outcome of - open government reforms, strategies, and initiatives. For the purpose of this chapter, government transparency refers to stakeholder access to, and use of, public information and data concerning the entire public decision-making process, including policies, initiatives, salaries, meeting agendas and minutes, budget allocations and spending, etc. Information and data disclosed should serve a purpose and respond to citizen's needs (OECD, 2021[1]). Concretely, promoting transparency enables citizens to exercise their voice and contribute to setting priorities, monitoring government actions and having an informed dialogue about – and participating in – decisions that affect their lives. In addition, transparency is crucial for good governance and contributes to the fight against corruption, clientelism and policy capture, all of which are imperative for restoring citizens’ trust in government.

Transparency is underpinned by the right to access to information (ATI), which is understood as the ability for an individual to seek, receive, impart, and use information effectively (UNESCO[2]). This right is materialized through ATI laws, which are considered the first-generation of transparency policies. More recently, governments have shifted from solely publishing information and data, towards a more targeted disclosure that is more useful and impactful for stakeholders. In doing so, governments enable a two-way relationship with stakeholders providing information, as well as gathering their feedback to move towards increased accountability and better citizen and stakeholder participation.

Overall, Brazil is highly committed to the principle of transparency. For many years, transparency initiatives have largely dominated Brazil’s open government agenda, most notably with the development of the legal and institutional framework for ATI. These efforts have resulted in a significant volume of information becoming available alongside a simplified process to request it at the federal level. However, further efforts to consolidate the ATI framework across other branches and levels of government are still needed. Moreover, the existing transparency mechanisms could benefit from a more strategic use to monitor government action and to enable wider engagement with stakeholders to reinforce a culture of transparency.

This Chapter examines the opportunities and challenges that Brazil faces in implementing the open government principle of transparency. Based on Provisions 2 and 7 of the OECD Recommendation of the Council on Open Government (hereafter “OECD Recommendation”) (Box 7.1), it provides an in-depth assessment of the legal, institutional and implementation frameworks for access to information, the mechanisms and tools for proactive and reactive disclosure, as well as the role of transparency policies to enable stakeholder participation in policy design and decision-making. While the assessment focuses on the application of transparency policies at the federal government, it also integrates the perspective of other levels and branches of government.

Box 7.1. Provisions 2 and 7 of the OECD Recommendation of the Council on Open Government

Provision 2

Ensure the existence and implementation of the necessary open government legal and regulatory framework, including through the provision of supporting documents such as guidelines and manuals, while establishing adequate oversight mechanisms to ensure compliance;

Provision 7

Proactively make available clear, complete, timely, reliable and relevant public sector data and information that is free of cost, available in an open and non-proprietary machine-readable format, easy to find, understand, use and reuse, and disseminated through a multi-channel approach, to be prioritised in consultation with stakeholders;

Source: OECD (2017[3]), Recommendation of the Council on Open Government, https://legalinstruments.oecd.org/en/instruments/OECD-LEGAL-0438

The legal, policy and institutional frameworks for transparency in Brazil

The legal framework for transparency could benefit from more coherence

Transparency has been a high-level federal priority. For many years, transparency initiatives have dominated the open government agenda. For instance, this principle has been included as an objective in the open government policy and the digital government strategy. Moreover, the four Open Government Partnership (OGP) action plans have all had transparency-related commitments (see Box 7.2 and Chapter 3) (OGP[4]). They have contributed to advance the transparency agenda in several fronts, from supporting subnational governments with ATI provisions to developing a federal open data policy, to fostering active transparency in environmental and health issues. In fact, this focus has resulted in an overlap of the conceptual understanding of transparency with open government, meaning that the two terms are used as synonyms. As argued in Chapter 3, this was confirmed during the fact-finding mission where stakeholders would interchangeably refer to both concepts in the same way.

According to the responses to the OECD Survey on Open Government Policies and Practices in Brazilian Public Institutions, the approach of the government of Brazil to transparency is trifold: publishing information proactively, guaranteeing citizens' right to information, and providing open government data. According to the Office of the Comptroller General (Controladoria-Geral da União - CGU), who is in charge of the transparency agenda, this approach allows stakeholders to use information and data for engaging and monitoring government action (CGU[5]).

Box 7.2. Transparency commitments in Brazil’s OGP actions plans

Action Plan 5 (2021 – 2023):

Improve the quality and availability of environmental databases by promoting standardization, unification and integration of information from different public bodies and entities.

Make new information on federal public properties available online, improve the quality of information already made available - including on the current use of federal properties - and disclose data in formats enabling reusability by civil society.

Implement standards and guidelines for the integration of systems and data of the various National Health Surveillance System bodies in order to enable interoperability and enhanced usability, with a view to improving communication with the citizen.

Action Plan 4 (2018 – 2020):

Implement instruments and transparency actions, access to information and the development of capacities to expand and qualify the participation and public oversight over the repair processes

Develop a National Electronic System for information requests (e-Sic) in order to implement the Access to Information Law in states and municipalities

Establish, in a collaborative way, a reference model for an Open Data Policy that foster integration, training and awareness between society and the three government levels, starting from a mapping process of social demands

Action Plan 3 (2016 – 2018):

Enhance mechanisms in order to assure more promptness and answer effectiveness to information requests, and the proper disclosure of the classified document list

Ensure requester’s personal information safeguard, whenever necessary, by means of adjustments in procedures and information access channels

Make room for dialogue between government and society, aiming at generating and implementing actions related to transparency in environment issues

Formulate a strategic matrix of transparency actions, with broad citizen participation, in order to promote better governance and to ensure access and effective use of data and public resource information

Action Plan 2 (2013 – 2016):

Restructuring the Transparency Portal

Development of the “Access to Information Library”

“Brazil Transparent” Programme

Development of Monitoring Reports on the Electronic Citizen Information System (e-SIC)

Development of an Indicators Model for Transparency of Brazilian Municipalities

Action Plan 1 (2011 – 2013):

Restructuring the Transparency Portal

Guide for Public Officials on Access to Information

Capacity Building Programmes for Public Officials

Diagnostic Study on the Transparency Values of Executive Branch

Note: This list is not exhaustive.

Source: Authors own elaboration based on OGP (n.d.[4]), Brazil, https://www.opengovpartnership.org/members/brazil/.

Brazil has developed a comprehensive regulatory framework through several laws, decrees and policies with varying scopes of application that regulate several transparency provisions. These provisions are either interlinked or complementary to access to information, such as open data, protection of personal data and archives (see Table 7.1).

Table 7.1. Brazil’s transparency legislative and regulatory frameworks

|

Law, decree, policy |

Scope of application |

Description |

|---|---|---|

|

The national ATI law, The Law n° 12,527, of November 18, 2011 |

National |

The national ATI law outlines the general procedures for proactive and reactive disclosure for all levels and branches of government. |

|

The open data policy, Decree N° 8,777 of May 11, 2016 |

Federal |

The policy aims to promote the publication of open data in a sustainable, planned and structured way. The policy provides for almost every federal body to have a biannual Open Data Plan (PDA) containing an inventory of every dataset owned by the government body. |

|

Decree N° 9,903 of July 8, 2019 |

Federal |

Amends Decree 8,777 to provide for the management and rights of use of open data. |

|

The General Law on Protection of Personal Data, N° 13,709, of August 14, 2018 |

National |

Provides for the processing of personal data, including in digital media, by a natural person or a legal person under public or private law, with the objective of protecting the fundamental rights of freedom and privacy and the free development of the personality of the natural person. |

|

The national policy of public and private archives, Law 8, 159, 1991 |

National |

Aims to document and protect archival documents as an instrument to support administration, culture, scientific development and as evidence and information. |

|

The fiscal responsibility law, N° 101, 2000 |

National |

This law establishes obligations on fiscal responsibility and the penalties for governments that do not comply. The provisions include mandatory transparency of spending and revenues and the need for public hearings in the development of budgets. |

|

Complementary law N° 131 of May 27, 2009 |

National |

Complementing the fiscal responsibility law, it establishes public finance standards for responsible fiscal management in order to determine the budgetary and financial spending. It makes mandatory the publishing of online data on spending and revenues. |

|

Law N° 14,129 of March 29, 2021 |

National |

Provides for principles, rules and instruments for Digital Government and for increasing public efficiency. |

|

Law N° 14,063 of September 23, 2020, use of electronic signatures |

National |

The law provides for the use of electronic signatures in interactions with public entities, in acts of legal entities, in health matters and on software licenses developed by public entities. It determines that the information and communication systems are governed by an open source license. |

|

Digital government strategy (DES) for 2020-2022, Decree N° 10,332/2020 |

Federal |

The strategy contains concrete commitments to improve transparency and participation as part of its plan to improve public service delivery. |

|

National Open Government Policy, Decree Nº 10,160/2019 |

Federal |

The national open government policy contains concrete objectives linked to fostering transparency and ATI. |

|

Decree N° 5,482, of June 30, 2005 |

Federal |

The Decree provides for the disclosure of data and information by the agencies and entities of the federal public administration, through the Internet. In practice, it defines the rules for the implementation of the transparency portal. |

|

Law N° 13,898, of November 11, 2019 |

Federal |

The law provides guidelines for the preparation and execution of the Budget Law of 2020 and other measures. While this law changes every year with the new approved budget, it systematically includes transparency provisions. |

|

Decree N° 8,945 of December 27, 2016 |

Federal |

The Decree outlines the transparency obligations for state owned companies. |

Note: The list if not exhaustive.

Source: Author’s own elaboration based on (Casa Civil, 2011[6]); (Presidency of the Republic, 2016[7]); (Presidency of the Republic, 2019[8]); (Presidency of the Republic of Brazil, 2018[9]); (Presidency of the Republic, 1991[10]); (Presidency of the Republic, 2000[11]); (Presidency of the Republic, 2009[12]); (Presidency of the Republic, 2020[13]); (Presidency of the Republic, 2020[14]); (Presidency of the Republic, 2019[15]); (Presidency of the Republic, 2005[16]); (Official Diary of the Union, 2021[17]); (Presidency of the Republic, 2019[18]); (Presidency of the Republic, 2016[19]).

In addition to the framework listed in Table 7.1, other laws and decrees also create transparency obligations on sectoral areas (environment, budget, etc.) while others provide protection for specific information (fiscal, personal, etc.). These obligations contribute to develop a more transparent culture in the public administration and provide concrete tools for citizens to monitor government actions. For instance, through the mandatory publication of public revenues and expenditures, citizens and stakeholders can conduct oversight on government spending. However, interviews conducted during the fact-finding mission revealed that the complex net and interaction of regulations and processes can represent confusing obligations, burdensome reporting lines and bureaucratic procedures, particularly for subnational governments. While this challenge is not exclusive to transparency obligations, more clarity and coherence in regard to the primacy and complementarities across the laws, decrees and policies could help improve the overall understanding and implementation. Aware of this challenge, Brazil is considering integrating access to information, open data and other transparency related-elements into a single decree called the Transparency Policy. While it would only apply to the federal government, the Policy could provide the needed coherence among regulations and obligations to federal government institutions. In order to fully integrate the transparency agenda into the wider open government agenda, this Transparency Policy could become part of the Open Government Strategy, recommended in Chapter 3.

Moving from transparency as an element of control to a new culture of governance

At the institutional level, the transparency agenda is co-ordinated by the Directorate of Transparency and Social Control (DTC), in the Secretariat for Transparency and Prevention of Corruption (Secretaria de Transparência e Prevenção da Corrupção - STPC) within the CGU (see Chapters 6 and 8 on how social control is understood as accountability and participation in Brazil). According to interviews during the fact-finding mission, this mandate is recognised by all stakeholders across the government and civil society. In practice, the CGU’s ministerial status provides high visibility and authority to its actions. However, given its historic mandate for internal control, the approach to transparency is often perceived by federal bodies as a control issue rather than an attempt to change the administrative culture, limiting the potential that this agenda has in inclusive policy and decision making as well as in stakeholder participation, accountability and restoring trust in government. Therefore, the CGU could carry out awareness raising campaigns for public officials to move from a control approach into transparency as a new culture of governance that both enables and encourages citizen’s participation in policy-making and service-design and delivery, engages stakeholders in effective monitoring of government actions and prioritizes access to reliable information to identifying counter-measures and promoting open decision-making contributing to regaining citizens’ trust government.

The involvement of stakeholders in the elaboration, implementation and monitoring of transparency agenda increases awareness and buy-in

Another relevant body in regard to transparency is the Council for Public Transparency and Fight against Corruption (Conselho de Transparência Pública e Combate à Corrupção - CTPCC). Created by Decree 9,468 from 2018, the CTPCC acts as an advisory body within the CGU and is composed of fourteen members, seven representatives of the Federal Executive Branch and seven from organized civil society (Presidency of the Republic, 2018[20]). The Council aims to debate and suggest measures for the improvement and promotion of federal policies and strategies on several topics including transparency and access to public information. For instance, the CTPCC is involved in preparing and discussing the content of the Transparency Policy (Official Diary of the Union, 2020[21]). The work of the CTPCC related to anti-corruption and public integrity will be reviewed in detail in the OECD Integrity Review of Brazil (OECD, Forthcoming[22]). Other branches and levels of government have also developed similar advisory bodies that include external stakeholders, such as the Transparency and Social Control Council within the Federal Senate (Federal Senate[23]).

The involvement of civil society organisations in policy elaboration and implementation across levels and branches of government is crucial to increase awareness and uptake and to ensure consistency across thematic areas within the transparency agenda. The CGU could leverage the use of the CTPCC by ensuring a wider representativeness of stakeholders in the elaboration, implementation and monitoring of its transparency agenda to go beyond the usual suspects. In the medium term, as part of the recommended transition towards a fully integrated open government agenda (see Chapters 3 and 4), the Council for Public Transparency and Fight against Corruption could become part of the wider Open Government Council, as discussed in Chapter 4. This integration would strengthen the links between both agendas and ensure coherence and alignment.

The Brazilian legal framework for access to public information

The right to information is recognised at the highest level in Brazil

In public administration, ATI is defined as the existence of a robust system through which government information and data is made available to individuals and organisations (UNESCO, 2015[24]). In 1946, freedom of information was recognised as a “fundamental right and the touchstone of all freedoms” by Resolution 59 of the United Nations General Assembly (UNGA, 1946[25]). As a consequence, the right to ATI has been enshrined in several countries’ constitutions, including in 70% of OECD Countries, such as Belgium, Colombia, Greece and Portugal (Box 7.3). In Brazil, the right to information is recognised in the 1988 Constitution of the Federative Republic of Brazil, as discussed in Chapter 3:

Article 5 XIV and XXXIII: “Access to information is guaranteed to everyone and the confidentiality of the source is protected, when necessary for professional practice; (…) all persons have the right to receive, from the public agencies, information of private interest to such persons, or of collective or general interest, which shall be provided within the period established by law, subject to liability, except for the information whose secrecy is essential to the security of society and of the State”.

Item II of § 3 of article 37: “The law will regulate the forms of user participation in direct and indirect public administration, specifically regulating (…) access by users to administrative records and information on government acts”.

§ 2 of article 216: “It is incumbent upon the public administration, in accordance with the law, to manage governmental documentation and take steps to facilitate its consultation to those who need it” (Casa Civil, 1988[26]).

Box 7.3. Constitutions recognising the right to access information

Belgian Constitution

Article 32: “Everyone has the right to consult any administrative document and to obtain a copy, except in the cases and conditions stipulated by the laws, federate laws or rules referred to in Article 134”.

Colombian Constitution

Article 20: “Every individual is guaranteed the freedom to express and diffuse his/her thoughts and opinions, to transmit and receive information that is true and impartial, and to establish mass communications media.

Article 74: “Every person has a right to access to public documents except in cases established by law

Greek Constitution

Article 5(A): “1. All persons have the right to information, as specified by law. Restrictions to this right may be imposed by law only insofar as they are absolutely necessary and justified for reasons of national security, of combating crime or of protecting rights and interests of third parties. 2. All persons have the right to participate in the Information Society. Facilitation of access to electronically transmitted information, as well as of the production, exchange and diffusion thereof, constitutes an obligation of the State, always in observance of the guarantees of articles 9, 9A and 19”.

Portuguese Constitution

Article 268: “1. Citizens have the right to be informed by the Administration, whenever they so request, as to the progress of the procedures and cases in which they are directly interested, together with the right to be made aware of the definitive decisions that are taken in relation to them. 2. Without prejudice to the law governing matters concerning internal and external security, criminal investigation and personal privacy, citizens also have the right of access to administrative files and records”.

Source: Constitution of Belgium (1994[27]), https://www.dekamer.be/kvvcr/pdf_sections/publications/constitution/GrondwetUK.pdf; Constitution of Colombia (1991[28]), https://www.funcionpublica.gov.co/eva/gestornormativo/norma.php?i=4125; Constitution of Greece (1975[29]), https://www.hellenicparliament.gr/UserFiles/f3c70a23-7696-49db-9148-f24dce6a27c8/001-156%20aggliko.pdf; Constitution of Portugal (1976[30]), https://www.wipo.int/edocs/lexdocs/laws/en/pt/pt045en.pdf.

Having the right enshrined at the highest level creates the necessary legitimacy and mandate for developing a legal and institutional framework for access to information at all levels and across branches of government. However, having solely the right recognised is insufficient if it is not well operationalised with adequate support and effective implementation.

As further discussed in Chapter 2, at the supranational level, Brazil has adhered to a number of international treaties and conventions that recognise the right to information (Table 7.2). These treaties and conventions lay out the general principles for the right to information. Countries that have ratified these instruments, such as Brazil, commit to protect and preserve the rights stated therein by taking administrative, judicial and legislative measures for effectively enforcing them.

Table 7.2. International treaties and conventions recognising the right to information adhered by Brazil

|

International instruments |

Relevant provisions |

|---|---|

|

Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) (1948) |

Article 19: “Everyone has the right to freedom of opinion and expression; this right includes freedom to hold opinions without interference and to seek, receive and impart information and ideas through any media and regardless of frontiers”. |

|

International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) (1976) |

Article 19: “The exercise of the rights (…) carries with it special duties and responsibilities. It may therefore be subject to certain restrictions, but these shall only be such as are provided by law and are necessary: a) For respect of the rights or reputations of others; b) For the protection of national security or of public order (ordre public), or of public health or morals.” |

|

United Nations Convention against Corruption (adopted in 2003 entered into force in 2005) |

Article 10: “take such measures as may be necessary to enhance transparency in its public administration, including with regard to its organization, functioning and decision making processes, where appropriate”. Article 13: “(a) Enhancing the transparency of and promoting the contribution of the public to decision-making processes; (b) Ensuring that the public has effective access to information” |

|

Inter-American Convention on Human Rights (adopted in 1968, entered into force in 1978) |

Article 13: “Everyone has the right to freedom of thought and expression. This right includes freedom to seek, receive, and impart information and ideas of all kinds, regardless of frontiers, either orally, in writing, in print, in the form of art, or through any other medium of one's choice”. |

|

American Declaration of Principles on Freedom of Expression (2000) |

Item 4: “Access to information held by the state is a fundamental right of every individual. States have the obligation to guarantee the full exercise of this right. This principle allows only exceptional limitations that must be previously established by law in case of a real and imminent danger that threatens national security in democratic societies.” |

Note: This non-exhaustive list includes the most relevant treaties and conventions recognising the right to information, to which Brazil has adhered.

Source: Elaborated by author, based on (UN, 1948[31]); (OHCHR, 1976[32]); (UN, 2004[33]); (OAS, 1978[34]); (OAS, 2000[35]).

However, despite having signed the Regional Agreement on Access to Information, Public Participation and Justice in Environmental Matters in Latin America and the Caribbean in 2018 (also known as the Escazú Agreement) Brazil has, so far, not ratified it. To do so would require the Executive to send the Agreement to Congress for ratification. The Agreement is an important regional instrument that aims to guarantee “the rights of access to environmental information, public participation in the environmental decision-making process and access to justice in environmental matters” (ECLAC, 2018[36]). This legally binding Agreement, which entered into force in April 2021, has 26 articles that outline provisions to ensure that the rights for information, participation, and justice on matters relating to the environment are respected. In terms of ATI, it includes obligations for generating, disseminating and providing access to information pertaining to environmental matters. Ratifying this Agreement would not only signal high-level political commitment and leadership to this policy area but would also allow Brazil to strengthen its existing environmental framework. Box 7.4 outlines the main findings and recommendations of Brazil’s OECD Environmental Performance Review.

Box 7.4. Environmental information and transparency in Brazil

In 2021, the OECD evaluated the alignment of Brazil’s environmental legislation, policies and practices with 23 selected OECD legal instruments on the environment. In terms of transparency, the evaluation found that environmental information remains fragmented+. Several institutions collect, consolidate and publish environment-related data. Brazil does not publish periodic state of the environment reports despite having to do so by national law and in contrast to the provisions of the OECD Recommendation of the Council on Reporting on the State of the Environment.

In 2017, the Ministry of the Environment published a set of key environmental indicators (the National Panel of Environmental Indicators) to track progress in implementing environmental and sustainable development policies. This is in line with the requirements of Recommendation of the Council on Environmental Indicators and Information. However, data sources, definitions and calculation methodologies for these indicators need to be clarified and updated.

The national access to information law regulates broad access to public information, as promoted by the OECD Recommendation of the Council on Environmental Information. As found by this Chapter, the law is followed well at the federal level, but its implementation at the state and municipal levels varies.

The recommendation of the 2015 OECD Environmental Performance Review (EPR) of Brazil to develop a uniform system for the collection and management of environmental data, including on environmental law implementation and economic aspects of environmental policies, remains valid.

To facilitate its alignment with the OECD Recommendations on environmental information, the report recommended the government of Brazil to:

Regularly publish state of the environment reports, both at the federal and state levels.

Continue efforts to develop indicators on the implementation of environmental and sustainable development policies and ensure that these are regularly updated and supported by appropriate data sources, definitions and calculation methodologies; enhance consistency between regional and national data.

Provide public access to information about environmental performance of enterprises, including the register of their pollution releases and compliance records.

Source: OECD (2021[37]), Evaluating Brazil’s progress in implementing Environmental Performance Review recommendations and promoting its alignment with OECD core acquis on the environment, https://www.oecd.org/environment/country-reviews/Brazils-progress-in-implementing-Environmental-Performance-Review-recommendations-and-alignment-with-OECD-environment-acquis.pdf

The National ATI Law in Brazil

At a country level, OECD data shows that the operationalisation of the right to information can take different forms depending on the national context and each country’s own particularities. The legal guarantees are mostly made operational through ATI laws that can be enacted at the national and at the local level. According to the Global Right to Information Rating (RTI), ATI laws are present in 134 countries (RTI Rating[38]), including 37 OECD members1. The ATI legal framework can also take the form of specific decrees, as it is the case for Costa Rica, or of directives or laws giving access to certain sectorial information (i.e. environmental, health).

At the national level, Law 12.527 from 2011 (hereafter “national ATI law”) establishes the provisions to enforce the right to access information as provided by the Constitution (Casa Civil, 2011[6]). It represented an important milestone not only for the transparency agenda but more generally for the national open government agenda, as it was developed and adopted in the framework of Brazil’s adherence to the OGP in 2011 (see Box 7.2).

According to the RTI, Brazil’s ATI law is ranked as the 29th strongest in the world, in terms of the quality of its legal provisions. With a total of 108 points out of 150 possible, it ranks significantly higher than the OECD average of 81 and above the average of Latin American countries of 93 (RTI Rating[39])2. The Rating, however, only examines the quality of the legal provisions for reactive disclosure and does not account for their implementation nor for proactive disclosure provisions.

The national ATI law has a wide scope of application but its uptake remains weak at the subnational level

The breadth of application of ATI laws indicates whether the provisions in place apply to all branches of government, to all levels of governments, to independent institutions of the state and / or to the entities carrying out public functions or managing public funds. Unlike most OECD countries, the national ATI law in Brazil has a wide scope of application covering all branches and levels of government, as well as private entities managing public funds, state-owned enterprises, independent institutions and other entities performing public functions (Articles 1-2). Among OECD members, ATI laws include small administrative regions (i.e. towns, cities) in 81% of OECD countries (e.g. Austria, Belgium, and Mexico), 53% cover the legislative and 59% the judicial branches (e.g. Chile, Estonia, and Slovenia), 84% of OECD countries comprise their independent state institutions (e.g. Finland, Japan, and Norway). These numbers vary for other bodies such as state-owned enterprises (78%) or private entities managing public funds (63%).

Similar to other countries with a federal structure, each level of government and each branch of government in Brazil is supposed to define specific rules in their own legislations for implementing the general provisions stressed in the national ATI law. While most public bodies have adopted regulations to comply with the minimum requirements of the national ATI law, a few have gone beyond. Such is the case of the federal government, which adopted Decree 7.724 in 2012 (hereafter “federal ATI decree”), to specify the procedure to provide access to information in 300 federal bodies (Casa Civil, 2012[40]). Importantly, the federal ATI decree assigned oversight responsibility of the ATI obligations to the CGU. The other branches of government have also adopted legal provisions to comply with the national ATI law. In particular, the Federal Senate (the Upper House) enacted the Executive Committee Act N° 9 in 2012 (Federal Senate, 2012[41]) to regulate access to data, information and documents. The Chamber of Deputies (the Lower House) enacted Act N° 45 in 2012 (Chamber of Deputies, 2012[42]), specifying the provisions for the application of the ATI national law. Through the Resolution N° 215 from 2015, the judicial branch also regulated the application of the national ATI law (National Council of Justice, 2015[43]). Some independent institutions, such as the Court of Accounts (TCU) and the Federal Public Prosecutor (Ministério Público Federal - MPF), have also established their own procedures for granting ATI within their institutions in accordance to the national ATI provisions.

However, at the municipal level, the adoption of their own ATI legislation remains weak. All 26 states and the federal district have developed their respective ATI provisions, however, there is limited data showing the exact number of municipalities that have done so. Article 45 of the national ATI law states that “it is up to the States, the Federal District and the Municipalities, in their own legislation, in compliance with the general rules established in this Law, to define specific rules”. Unlike other federal systems, Brazilian municipalities have financial, administrative and political autonomy, as further discussed in Chapter 2. This implies that each of the 5,570 municipalities have to, either adopt minimum regulations to comply with the national ATI law, or develop their own ATI law going beyond. This level of independence that is afforded to municipalities in Brazil influences the enforcement of several national laws at this level, including ATI.

In addition, in a country with important regional disparities such as Brazil (see Chapter 2), municipal capacities also play an important role in the adoption and implementation of the national ATI law as it requires adequate human and financial resources. Strong co-ordination and oversight mechanisms, as well as adequate incentives and effective sanctions, are also needed to ensure effective implementation.

To counter the weak compliance by Brazilian municipalities, the CGU developed the Brazil Transparency Programme (Programa Brasil Transparente - PBT) initiative. The PBT aims to motivate states and municipalities to adopt and implement the national ATI law. Established in 2013, the PBT is a voluntary programme that encourages subnational governments in committing to regulate the national ATI law, by providing implementation support through capacity building activities, technical materials, among other measures. As of November 2019, 1,542 out of the existing 5,570 (28%) municipalities had adhered to the PBT, as well as other subnational entities (such as judicial and legislative branches at both the state and municipal level) (CGU[44]). While the PBT has contributed to an increase of municipalities regulating the national ATI law, a study from the Getulio Vargas Foundation (Fundação Getulio Vargas – FGV), found that adhering to the PBT has not always lead to the actual implementation of ATI provisions (Michener, Contreras and Niskier, 2018[45]).

Further efforts are needed to promote the adoption of ATI obligations from the national ATI law across levels and branches of government. On the short term, the CGU could continue to foster compliance with the national law through initiatives such as the PBT that not only facilitate the adoption of the needed ATI regulatory framework, but also provide implementation support to increase capacities across subnational entities. In addition, as other sections of this Chapter will argue, to address the lack of effective oversight and enforcement of ATI obligations across all levels, stronger institutional mechanisms are needed. In the longer term, if the law is reformed, the government of Brazil could provide further clarity and details to the legal ATI obligations for other levels and branches of government.

Proactive disclosure of information and data In Brazil

Proactive disclosure refers to the act of regularly releasing information before it is requested by stakeholders, which is deemed to be essential as it shows a fully integrated and institutionalised culture of transparency by governments. It also reduces administrative burden for public officials involved in handling and answering individual ATI requests, which can often be lengthy and costly. Favouring proactive disclosure “encourages better information management, improves a public authority’s internal information flows, and thereby contributes to increased efficiency” (Darbishire, 2010[46]). Finally, it ensures timely access to public information for citizens as information is published as it becomes available and not upon request (OECD, 2016[47]). In fact, the proactive disclosure provisions from ATI laws in 21 OECD Member countries have set the legal mandate for open government data requirements and/or responsibilities. Other countries have developed separate open data regulations (OECD, 2018[48]).

The legal obligations for proactive disclosure at the federal level are in line with OECD good practices

Most ATI laws require the proactive disclosure of a minimum set of public information and data to be published by each institution. As in the majority of OECD Member countries, Article 8 of Brazil’s national ATI law requires all public bodies to proactively disclose the organigram and functions of the institution, budget documents, annual ministry reports, opportunities for and results of public consultations, as well as public calls for tenders (public procurement). In addition, Article 7 of the federal ATI decree adds more requirements for proactive disclosure by federal bodies, such as remunerations and subsidies received by public officials, as done by 42% of OECD Member countries. It is important to note, that in practice, more information is published proactively at the federal level, than what is required in both the national ATI law and the federal ATI decree, thanks to other legal frameworks. For instance, Ordinance 262 from 2005 requires all federal bodies to publish their management reports, annual activity reports and audit certificates. Overall, federal practice exceeds national requirements as well as OECD good practices.

The CGU has led efforts to implement proactive disclosure obligations at the federal level

An important element of any ATI law is where and how information is published. In addition to the type of information disclosed, Provision 7 of the OECD Recommendation specifies that data and information disclosed should be “clear, complete, timely, reliable relevant, free of cost and made available in an open and non-proprietary machine-readable format, easy to find, understand, use and reuse, and disseminated through a multi-channel approach, to be prioritised in consultation with stakeholders” (OECD, 2017[3]). In OECD countries, proactively disclosed information is mostly published either in a single location, such as a central portal, on each ministry’s or institution’s website, or in a combination both. In Brazil, public bodies subject to the national ATI law are obliged to disclose the required information through their official websites. These websites have a series of requirements specified by the national ATI law, such as providing a content search tool allowing ATI in an objective, transparent, clear and easy-to-understand language and enabling the recording of reports in various electronic formats, including open and non-proprietary, such as spreadsheets and text, in order to facilitate the analysis of information. All bodies are required to adopt the necessary measures to ensure accessibility of content for people with disabilities. Only municipalities that have less than 10,000 inhabitants are exempted from the mandatory disclosure on websites, but are still obliged to disclose budgetary and financial information. The federal ATI decree provides more in-depth information of how information should be published. Moreover, in addition to the mandatory website for proactive disclosure, some federal bodies have gone beyond the legal requirements to develop tools that facilitate the access and the use of public information and data, such as the “Platform + Brazil” and the “Purchasing Panel” developed by the Ministry of Economy. As the below section on targeted transparency describes in more detail, some of these tools enable a two-way relationship between public institutions and stakeholders.

Efforts have also been made by the CGU to develop platforms that compile available information and data from federal bodies in order to facilitate access and monitoring by stakeholders, notably with the Transparency Portal and the Open Data Portal (see Chapter 4 for a description of all relevant portals in the area of open government). Created in 2004, the Transparency Portal (www.portaltransparencia.gov.br) represents a major landmark for Brazil’s transparency and open government agendas and has helped paved the way for several of the current ATI and open data initiatives (CGU[49]). The portal centralises information from 32 government databases and provides users with different ways to explore and use the information and data with graphic resources, an integrated search engine and the possibility to freely download all available information and data in an open format. The portal mainly contains information on federal expenditure, including federal transfers to states, municipalities and the federal district. The overarching aim of the portal is to serve as an anti-corruption and control tool to monitor the use of public resources. For instance, stakeholders can track and verify whether federal transfers to municipalities have been used to provide the public services they were intended to. Importantly, in case any wrongdoing is identified, the portal provides the necessary information for citizens to make complaints or claims against any federal body through Fala.BR (see section below for more information). Within the portal, the CGU created a web page called the Transparency Network, which provides access to projects and actions relevant to social control. It includes links to some of the tools for social control developed by federal bodies in sectoral areas, such as education (e.g. scholarships paid to individuals), social benefits (e.g. continuous cash benefits), urban development (e.g. National System for Survey of Civil Construction Costs and Indexes (SINAPI), among others. However, the network is not an exhaustive list of all existing platforms nor the portal contains all available public information (CGU[50]).

In practice, the Transparency Portal benefits from wide popularity among citizens and stakeholders with over 27 million visits and 156 million Application Programming Interface (API) requisitions in 2020 (CGU[51]). Its use by civil society has led to concrete changes in government actions. For instance, in 2008, journalists analysed spending of the government’s corporate credit cards and found several abuses (Prado, Ribeiro and Diniz, 2012[52]). As a consequence, the federal government adopted the Decree 6.370 in 2008 to prevent the use of these cards for personal expenses which led to a 25% decrease of government credit card spending between 2007 and 2008 (Folha de S.Paulo, 2008[53]). That same year, the CGU launched a manual to guide federal public officials on how to use this form of payment (CGU, 2008[54]). Another study published in 2015 by a national newspaper analysed data extracted from the Transparency Portal and from the Higher Education Census showing that the Student Financing Programme (FIES) was financing private colleges for high income students instead of low income ones (Estadão, 2015[55]). The study resulted in a regulatory changes for the programme through the normative ordinances 21 and 23 to ensure that credits provided are merit-based (Exame, 2017[56]). These impact stories are testimony to the impact of the use of the Transparency Portal.

As highlighted in Chapter 9 on Open Government Data, another relevant effort is Brazil’s Open Data Portal (https://wiki.dados.gov.br/). The portal provides a central access point for researching, accessing, sharing and using public data. Open government data has also been used by stakeholders for monitoring government actions. For instance, the oncologic observatory (Observatório de Oncologia) uses government open data from the Ministry of Health (DataSUS), the National Cancer Institute (INCA) and the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE) to analyse cancer trends in Brazil (Oncology Observatory, n.d.[57]).

The implementation of proactive obligations varies across federal bodies

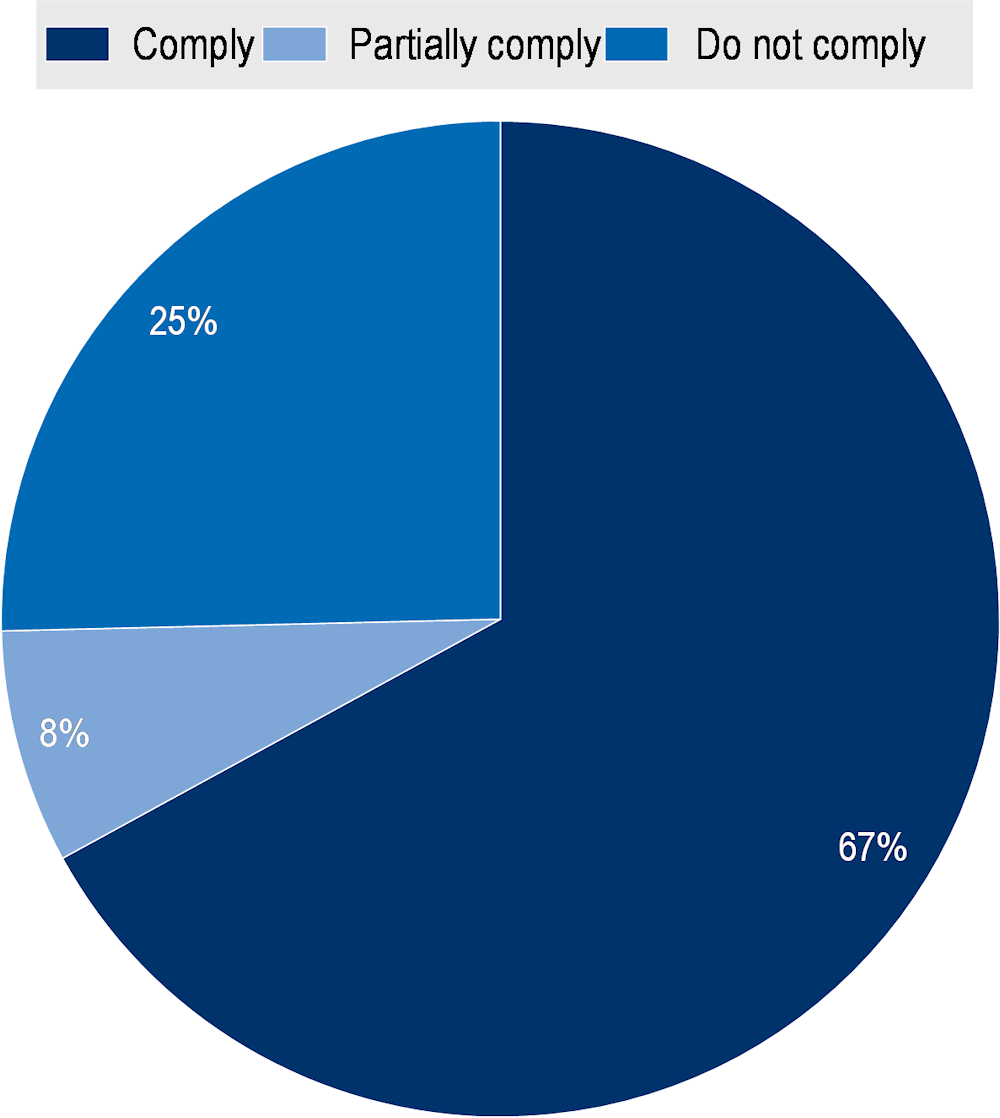

The creation of these portals has resulted in a significant volume of information and data becoming available to the population. However, interviews conducted during the fact-finding mission revealed a series of challenges in this regard. While some federal bodies have indeed developed good practices beyond the legal requirements, the implementation of basic proactive measures varies across institutions. An ATI Panel created by the CGU provides up-to-date statistics on compliance of proactive and reactive disclosure obligations. It reveals that between 1 January 2012 and 28 February 2022, 67% of federal bodies comply with their proactive obligations, 8% partially, and 25% do not (CGU[58]) (see Figure 7.1). The disaggregated data by shows that the highest compliance score is on information related to tools and technological aspects of websites from federal bodies (92%) and the lowest score is on information related to revenue and expenditures (57%).

Figure 7.1. Compliance with proactive transparency obligations by federal bodies

Note: The data covers the period from1 January 2012 to 28 February 2022.

Source: Authors own elaboration based on data from the ATI Panel (CGU, n.d.[58]) on 28 February, 2022. http://paineis.cgu.gov.br/lai/index.htm

The relatively low compliance rate may be partially explained by the different technical capacities across the over 300 federal bodies. According to interviews, other factors such as the lack of sanctions for non-compliance to the national ATI law, the persistence of a culture of secrecy in certain sectors and a lack of awareness of the benefits of proactive disclosure also influence the levels of compliance. To counter these challenges, the CTPCC proposed the creation of an active Transparency Observatory to expand the monitoring capacity for the proactive publication or withdrawal of information as well as for disseminating new information. The following set of actions were defined for its implementation: 1) a tool to report publication or withdrawal of information; 2) designing a dissemination and action process for information withdrawn; 3) elaborating a monitoring process; and 4) developing a dissemination tool for the information of the observatory (Official Diary of the Union, 2020[59]). As coordinator of this initiative, the CGU is working to implement these actions. Brazil could continue working towards the creation and implementation of the Transparency Observatory as it could help to address challenges related to the unequal implementation of proactive disclosure provisions across federal public institutions. Additional training and awareness raising activities for federal public institutions laying out the importance and impact of proactive disclosure could also help increase compliance. For instance, Brazil could collect and disseminate impact cases, such as the decrease in government credit card spending and the reform on the FIES, to increase buy-in from public officials. When facing a similar challenge of compliance with proactive provisions, the ATI oversight agency of Argentina co-created an Active Transparency Index with public officials and non-governmental stakeholders (Box 7.5).

Box 7.5. Active Transparency Index of Argentina

Argentina adopted its access to information (law 27,275) in 2016. In the framework of the law, the Agency for Access to Public Information (AAIP) was designated responsible for the implementation oversight identified challenges in the implementation of proactive provisions in its Article 32. In response, the AAIP created an Active Transparency Index designed collaboratively with relevant public officials and civil society in the framework of the fourth National Action Plan of the Open Government Partnership. The overarching aim of the Index is to measure the level of compliance of proactive transparency obligations stated in the Law 27,275 as well as to reduce the burden of ATI requests. The Index covers over 26 centralized and 94 decentralized institutions of the National Public Administration, 55 public companies, and 66 universities. These institutions are measured according to the following variables: the procedure to request the access of information, authorities and staff, salary scale, tax declarations, budgeting, audits, subsidies, and other transfers/operations.

Source: Government of Argentina (n.d.[60]), Proactive transparency (Transparencia activa), https://www.argentina.gob.ar/aaip/accesoalainformacion/ta

As further discussed in Chapter 4, the multiplicity of platforms and panels created by the federal government use different structures, terminologies and formats. For citizens and stakeholders, navigating these can be confusing and difficult, resulting in a struggle to find the information they need. For the government, it raises questions in terms of efficacy, reach and coordination. The current efforts on proactive disclosure could thus benefit from more standardization and simplification for users. Building on the example of the Transparency Network web page, the CGU could create a centralised and unique web page mapping all of the existing portals and panels where proactive information is disclosed. This web page could include guiding instructions for users to find the information they need. In an ideal case, this mapping page could be hosted within the Open Government Portal recommended in Chapter 4. Alternatively, should Brazil decide not to create the recommended Open Government Portal, the mapping page could become part of the Transparency Portal. Ultimately, making a more robust system for proactive disclosure that is easier to access and use can also ease the administrative and processing costs of access to information requests faced by federal public institutions, as will be explained below.

Other branches and levels of government have made efforts to proactively disclose information and data

According to the responses of OECD Survey on Open Government Policies and Practices in Brazilian Public Institutions, the other branches of government duly comply with their proactive transparency provisions and have developed their own tools and mechanisms to promote the access and use of their published information and data by stakeholders. For instance, the Federal Senate has its own transparency portal. The portal allows stakeholders to track legislative activity, file ATI requests, access open data, participate in debates and provide opinions on projects and proposals, among other actions (Federal Senate[61]). Similarly, the transparency portal of the Chamber of Deputies has relevant information on legislative results, parliamentary income and expenses, as well an ATI web page (Chamber of Deputies[62]). The Chamber of Deputies also has an Open Data Portal, offering not only relevant open datasets, but also a game that allows citizens to better understand the parliamentarians’ activities through the use of data (Chamber of Deputies[63]). The highest bodies of the judicial branch also have transparency portals that include the publication of proactive information (i.e. the Supreme Federal Court, Supremo Tribunal Federal – STF and the Superior Court of Justice, Superior Tribunal de Justiça – STJ) (STF[64]) (STJ[65]). These portals not only publish additional information beyond what is required by law, but also seek to provide it in a user-friendly way using infographics and simple language.

At the subnational level, however, the implementation of proactive measures varies, according to data from the 360 Transparent Brazil Scale (Escala Brasil 360° Transparente – EBT 360). Created by the CGU, the EBT 360 measures the performance of subnational governments with the national ATI law’s proactive provisions. In terms of proactive disclosure, it verifies whether an official website for publication exists, and which information is made available, such as the organigram and functions of the institution, budget documents, and public procurement processes, among others. It covers all states and 665 municipalities with more than 50,000 inhabitants (CGU[66]). An analysis of the EBT 360 data conducted for this study shows that proactive transparency measures have a significant higher performance with a score of 4.6/5 for states and 4.2/5 for municipalities, than reactive ones with 4.2/5 and 2.7/5 respectively. The results for proactive measures do not show any significant difference between population size and performance of municipalities. The overall higher performance, even in smaller municipalities, implies a stronger uptake and adherence by subnational governments in complying with proactive obligations. This was also reflected in the responses from states and municipalities participating in the OECD Survey on Open Government Policies and Practices in Brazilian Public Institutions, all of which publish information proactively on a regular basis and have a transparency portal available. According to interviews from the fact-finding mission, some of the challenges that municipalities face in this regard, in particular smaller ones, relate to the lack of human and financial resources for the acquisition and maintenance of information dissemination tools and portals.

Reactive disclosure of information and data in Brazil

ATI laws typically include provisions for reactive disclosure. Reactive disclosure refers to the right to request information that is not made publicly available. Usually, these provisions describe the procedure for making the request, including who can file the request, the possibility for anonymity, the means to file a request, the existence of fees, and the delay for response to the request.

Protecting the identity of stakeholders requesting information is important

While the Brazilian national ATI law does not mandate applicants to indicate the motivation or reason for the request, it requires the provision of an identification. At the federal level, some of the valid documents for a natural person include the Identity Card (ID), Passport, Voter Registration Card, National Driver's License (CNH), National Registry of Foreigners (RNE), the individual taxpayer registry identification for legal persons (Cadastro de Pessoas Físicas - CPF) and the national registry for legal entities (Cadastro Nacional da Pessoa Jurídica - CNPJ) (CGU[67]). Identifying a requester could discourage stakeholders to request information as they may fear reprisals. For this reason, OECD countries are increasingly allowing for anonymous requests either de jure, with legislation explicitly protecting the integrity and privacy of individuals and parties that file a request for information, such as Mexico, Australia and Finland, or de facto, where countries do not require proof of identity and only ask for an email or contact address to send the requested information, as in Chile or the Netherlands.

Following concerns from civil society groups such as Article 19 and Transparency International Brazil, the federal government implemented a measure to provide identity neutrality to requesters as part of an OGP commitment included in Brazil’s third action plan. While requesters are still required to provide their identity details when filing a request online, the CGU – as oversight body- limits the personal information to a small number of trained public servants and forwards the request to the relevant ministry or body without personal data, protecting de facto their identity. However, this measure only applies to the federal government and could be extended to the subnational levels.

Protecting the identity of requesters is important to avoid the risk of profiling citizens and acting on biases by governments. The CGU could encourage this practice implemented at the federal level to subnational governments. To do so, the CGU could provide the necessary training and awareness-raising for public officials via the PBT to implement it through their respective online platforms. In the longer term, if the law is reformed, the government of Brazil could include a clause of anonymity to ensure the protection of requesters at all levels and branches of government.

The process to file a request for information is well-established at the federal level

The ease to file requests is a critical aspect to measure the quality and usability of an ATI law. In Brazil, requests can be made “by any legitimate means” according to the national ATI law. The federal ATI decree provides more clarity of what these means are, specifying that public bodies should allow requests to be filed online (e.g. dedicated portal), by written communication (e.g. post), or in-person. These standards are also followed in practice by the Chamber of Deputies, the Federal Senate, and the Judiciary. According to the federal ATI decree, each federal body may provide additional means, such as email or telephone. This is also the case in most OECD countries, where requests can be made by email (77% of OECD countries), online (on each ministry’s website or a dedicated portal) (55%), in-person (68%), written communication i.e. by post (94%) or by telephone (45%) to the responsible public official or body. Nevertheless, while the federal ATI decree is specific in terms of means for filing a request, the lack of clarity in the national ATI law amplifies the risk of different interpretations in other levels and branches of government, and thus, of contradictory implementation.

The national ATI law requires all public institutions to create a Citizen Information Service (Serviço de Informação ao Cidadão - SIC). The SIC is an office or person that assists and guides the public in regard to access to information, and that helps citizens and stakeholders to report on the processing of documents in their respective units and to file documents and requests for ATI (Article 9). The Brazilian SIC is the equivalent of what the OECD defines as an ATI office or officer who is typically appointed to guarantee both proactive and reactive disclosure of information (see section below on institutional arrangements). According to the national ATI law, states, the federal district and the municipalities should elaborate rules in their respective legislations to create a SIC (Article 45). For federal government institutions, the federal ATI decree specifies that the SIC should be “installed in an identified physical unit, easily accessible and open to the public”. It mandates federal government institutions to disclose the telephone and electronic mail for the SIC on their websites.

To ease the process of requesting information, the CGU created in 2020 an online platform called Fala.BR (hereafter “Fala”) to replace what was formerly known as the e-SIC. Fala is an innovative platform that combines the federal ouvidorias3 and the SIC obligations. It allows citizens to not only request information, but also to make complaints or claims against any federal body, express satisfaction or dissatisfaction for a service or programme, and provide suggestions for improving or simplifying public services (CGU[68]). Importantly, users can also follow the progress of their request and file an internal appeal in case of non-conformity with the response. In addition, as further explained below, Fala allows the CGU to provide up-to-date statistics on requests. Overall, by centralising ATI requests into a single system, the Fala platform has significantly simplified the process for citizens, stakeholders and federal government institutions when making or processing an ATI request.

For subnational governments, however, the development and maintenance of such a platform represents an important administrative burden, especially for municipalities with limited resources and a lack of necessary IT skills and/or connectivity. This creates a bigger gap between the federal government and the subnational level and other branches of government when implementing ATI obligations. To counter the gap, through the PBT, the CGU offers the software of Fala to any interested government body along with a manual detailing the necessary specifications for implementation (operational environment, configurations, minimum equipment requirements, etc.). The CGU also offers technical trainings for public officials who will manage it. However, as aforementioned, only 28% of municipalities have adhered to the PBT. Some subnational governments have chosen not to use Fala, as they had already developed comprehensive ATI online systems of their own. This is the case, for instance, of the city of Porto Alegre and the federal district of Brasilia. Both of them are capital cities representing bigger populations and having greater resources than the average. This is also the case in other branches of government, where only the Federal Senate adopted the Fala system, whereas the Chamber of Deputies and the Judiciary use their own portals4.

For citizens, the process to file a request for information implies the need to first, differentiate between information pertaining to local, state and federal authorities, and second, searching for the applicable means to file a request. To further increase uptake at the subnational level, stronger incentives should be put in place for adopting the Fala system. This could for example be done by further portraying its benefits, such as the easing of administrative costs. The government may also consider creating interactive guidelines or manuals for citizens and stakeholders on how and where to request government information depending on the type of information. These guidelines or manuals could direct stakeholders towards the relevant branch or level of government responsible for the information.

Reasonable and clearly defined fees encourage stakeholders to request information

While filing a request for information in 85% of OECD countries is free of cost, 82% of countries charge fees related to the reproduction of the information, for example, depending on the number of pages to be reproduced. When a variable fee is charged, a cap on the amount of the fee is applied only in a limited number of countries, such as Austria, Finland and France. Most governments distinguish between the charging of fees related to documents that are already available, for example, on a central government portal, and those requests that require searching, retrieval, reproduction and mailing of the information. This is also the case in Brazil. Article 12 of the national ATI law states that “information search and provision services are free of charge, unless the public body or entity is otherwise demanded to deliver document copies, situation in which only the costs of such services and materials will be charged”. The applicable fees are the responsibility of each public body and are regulated by law 14.129 from 2021, which provides principles, rules and instruments for digital government (Presidency of the Republic, 2021[69]). The national ATI law includes a waiver of fees when the economic situation of the requester does not allow him/her to do so without prejudice to self- or family support. Following the Organization for American States (OAS) Model Law 2.0 on Access to Public Information (OAS, 2020[70]), Brazil could consider advocating to include the possibility of providing the information free of charge if it is deemed in the public interest, or in setting a minimum threshold of pages that can be delivered free of charge in the national ATI law if it is reformed.

Federal bodies have a high response rate to ATI requests

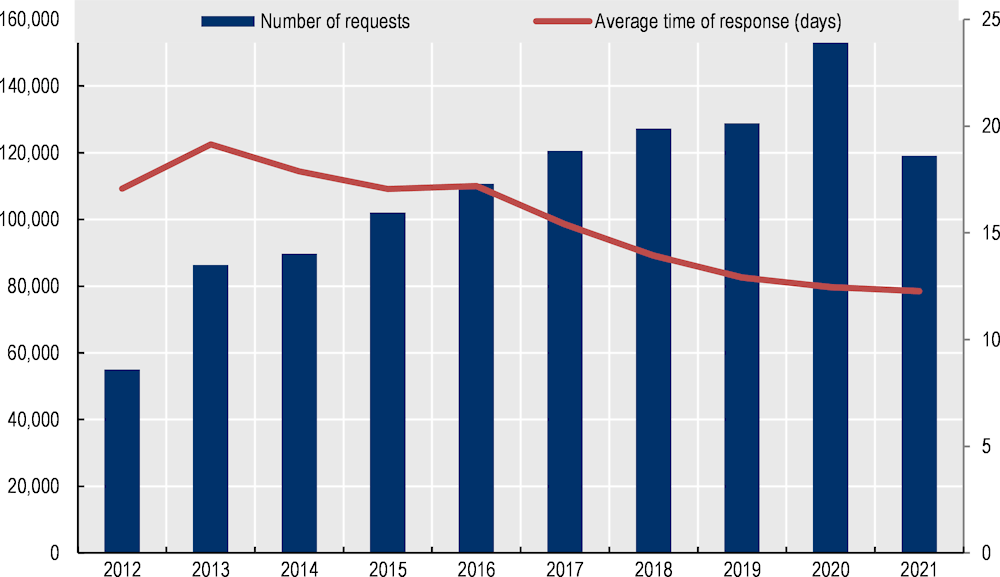

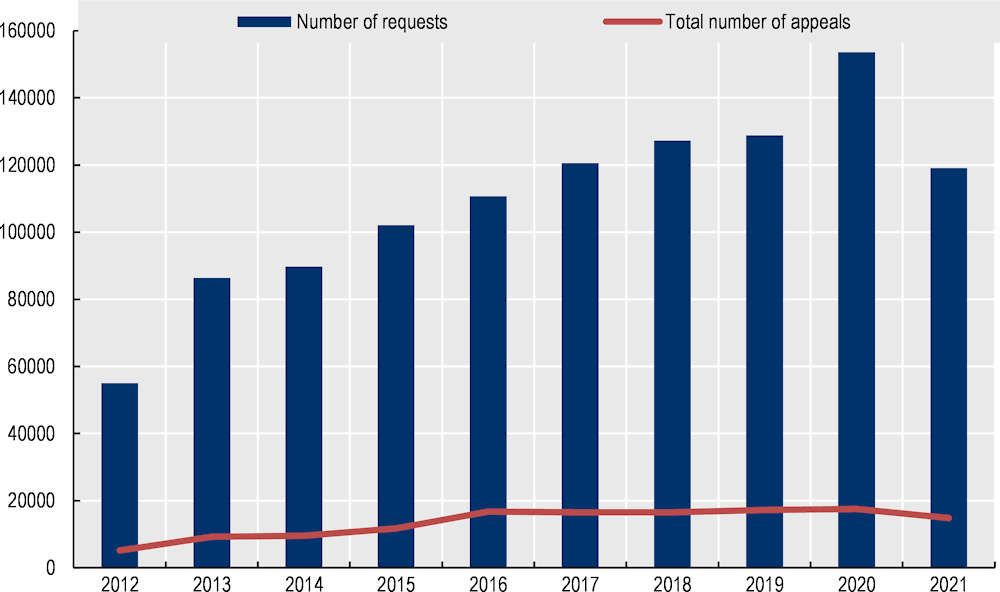

Once a request is filed, ATI laws specify the delay for response. The average delay is 21 working days in OECD countries (OECD, 2016[47]). This is also the case in Brazil, where public authorities are required to confirm the receipt of request immediately and have a 20-day maximum deadline for responding with additional 10 days for extensions. These extensions require informing the applicant. Since the federal ATI decree came into effect in 2012, the average time for response by federal bodies is of 15 days, below the maximum deadline. As Figure 7.2 shows, even with an increase of number of requests over time, the average time of response has decreased. This suggests that the ATI system, at the federal level, has improved in efficiency.

Figure 7.2. Number of ATI requests and average time of response by federal bodies (2012-2021)

Source: Authors own elaboration based on data from the ATI Panel (CGU, n.d.[58]) on 28 February, 2022. http://paineis.cgu.gov.br/lai/index.htm

In other countries, such as Spain, laws provide for negative administrative silence. This means that in the absence of a response within the period specified, the applicant can consider his/her request denied. Although countries can have legitimate reasons for denying a request (see section below on exemptions), the absence of a proper justification to the requester may imply arbitrary responses and legal insecurity, ultimately affecting trust in the law, in the government and in public officials. On paper, Brazil’s national ATI law guarantees that all denials should indicate the reasons for the refusal, communicate in case the public body does not have the information or indicate if the information is already publicly available (Article 11). In case of a denial, requesters should also be informed of the possibility for appeal including the deadlines, conditions and competent authorities to do so (see section below on appeals).

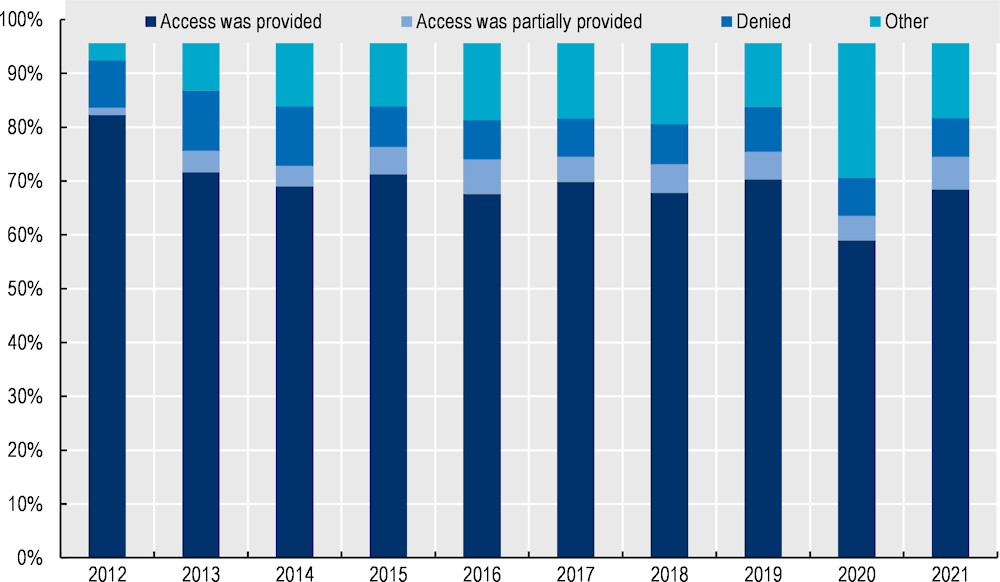

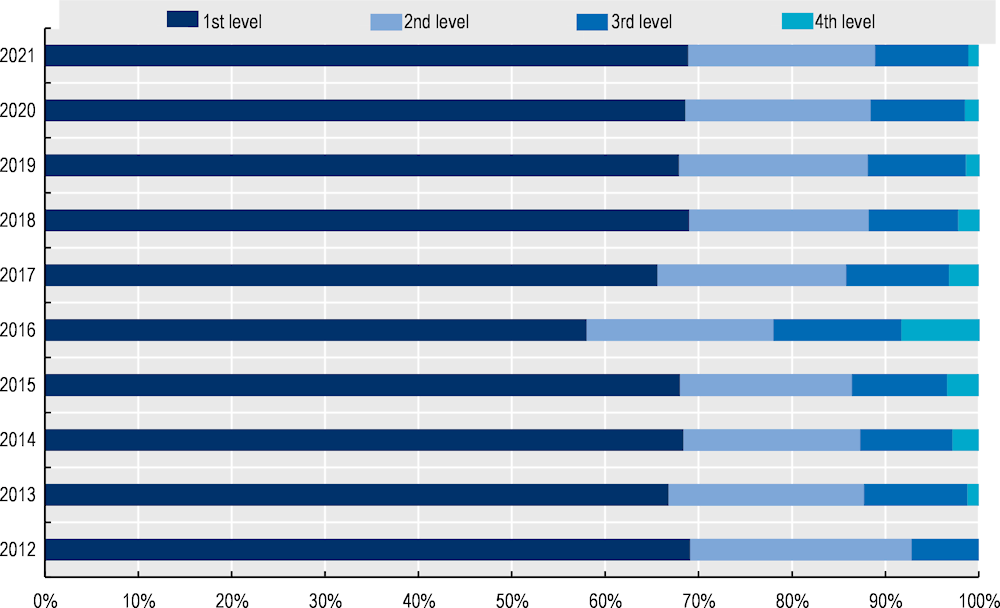

According to the ATI Panel created by the CGU, which is an online platform based on Fala data and which provides up-to-date statistics on ATI requests, federal bodies have a response rate of 99.5% for the more than 1.1 million requests received between 2012 and February 2022. The disaggregated data indicates that in 69% of those cases access to information was provided, 5% partially, while only 8% were denied. For the remaining 18%, information either pertained to other bodies, did not exist, the request was repeated, or was not a request for information (i.e. stakeholders asking the Ministry of Citizens why they have not received their social aid) (CGU[58]). As Figure 7.3 shows, the amount of cases where access was provided has been relatively stable over time even with an increase of cases per year, except for a slight decrease in 2020 that can correspond to the COVID-19 pandemic (see Box 7.6 for more information). An independent study conducted by FGV analysing 3,550 requests for information confirmed the high response rate for federal bodies with 91%, compared to 53% for states and 44% for municipalities (Michener, Contreras and Niskier, 2018[45]).

Figure 7.3. Type of responses to ATI requests by federal bodies (2012-2021)

Note: The ‘other’ category comprises information pertaining to other bodies, did not exist, the request was repeated, or was not a request for information.

Source: Authors own elaboration based on data from the ATI Panel (CGU, n.d.[58]), on 28 February, 2022. http://paineis.cgu.gov.br/lai/index.htm

The current efforts to improve the quality of information provided should be continued

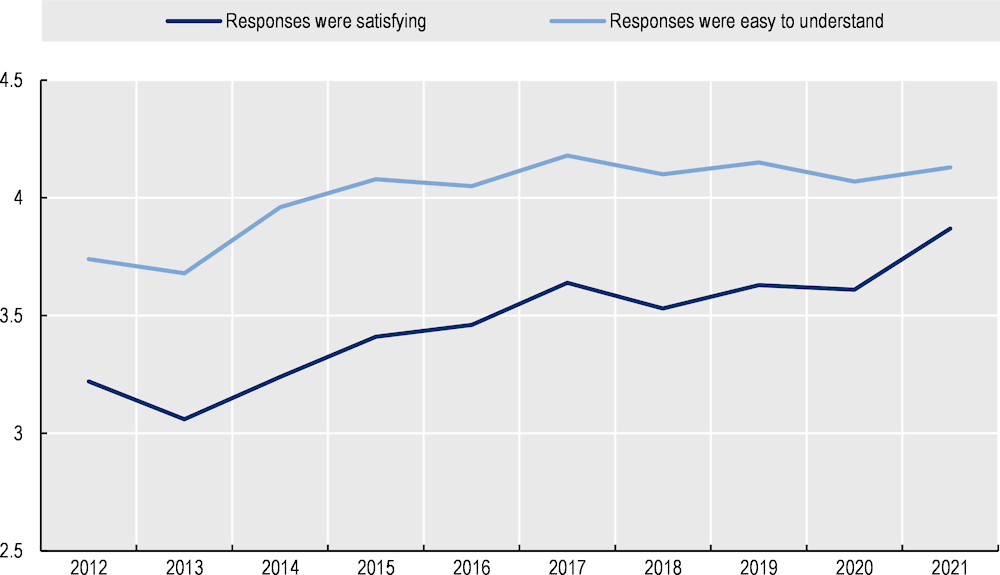

According to data from the ATI Panel, user satisfaction with requests for information have increased over time both in terms of quality, that is responses are satisfying, and clarity, that is responses are easy to understand (see Figure 7.4). While this progress reflects the important efforts made by the CGU to improve ATI efficacy and efficacy, the data only reflects the perception of 15% of users that made a request for information and who responded to the user satisfaction survey. In fact, during the interviews of the fact-finding mission, civil society groups raised concerns about the quality of the information provided by certain public bodies.

Figure 7.4. User satisfaction with ATI requests from federal bodies (2012-2021)

Note: The scale is 0 to 5, where 5 represents the most satisfying or most easy to understand.

Source: Authors own elaboration based on data from the ATI Panel on 28 February, 2022. http://paineis.cgu.gov.br/lai/index.htm

These concerns, although not reflected in the aggregated data from the ATI Panel, could be explained by several factors. First, the Fala system is relatively recent (mid-2020) and while it has simplified the process for public bodies, it also requires a period of adaptation for the teams of over 300 federal bodies in charge of dealing with ATI requests. Second, COVID-19 impacted the government’s capacity to respond to ATI requests in terms of onsite staff, access to internet connectivity and availability of resources (see Box 7.6). Third, as it will be explained below, the inefficiency of certain appeals process, the lack of sanctions for non-compliance and, in a few cases, of political pressure in specific policy areas, may also influence the quality of responses from certain federal bodies. Lastly, the indicators used in the ATI Panel by the CGU do not differentiate, for example a full vs partial response. One measure that the CGU has conducted to respond to the concerns of the quality of the information is the development of a searchable database in which all the requests made since July 2015 (date in which the e-SIC came into effect) and their answers are available for consultation by all stakeholders (Federal Government of Brazil[71]). While this is an important measure that helps increase transparency of the process and of the information provided, several stakeholders, during the fact-finding mission, raised that the website is difficult to navigate.

The CGU should continue carrying out efforts to improve the quality and transparency of information provided. In terms of the metrics used in the ATI Panel, the CGU could consider providing more transparency as to how indicators are calculated. In addition, as the below section will argue, a more efficient appeals process and stronger sanctions could stir federal government institutions to systematically provide information that is of higher quality. The government could also aim to improve the usage of the searchable database of requests and answers through a consultation with end-users. In addition, Brazil could follow the example of Mexico City in elaborating a framework or protocol to ensure ATI is provided during a crisis context (Box 7.6).

Box 7.6. Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on access to information in Brazil

In Brazil, the Provisional Measure No. 928 (medida provisória) suspended deadlines to answer ATI requests for public authorities who were subject to telework or quarantine, or if the public official or sector was primarily involved in the COVID-19 response. However, following a strong mobilisation from civil society and a ruling by the Supreme Court, the provisional measure was suspended. To analyse compliance during this period, the CGU published a report comparing data of requests between 2019 and 2020 for the period corresponding to the introduction of the state of health emergency in the country with Decree No. 6/2020 (March 20 to December 31, 2020). Data shows that average requests for information stayed relatively stable in both years and that the time of response decreased (14 days in 2019 to 13 days in 2020). Moreover, while access was provided in 50% of the cases in 2020, only 6% were denied. Surprisingly, the satisfaction level of users receiving a response remained almost the same during the pandemic from 3.9/5 to 4/5.

This data implies, on the one hand, while government capacity was indeed limited in terms of onsite staff, access to online connectivity and availability of resources, strong efforts were made to comply with ATI obligations. The few cases were requests and appeals were not responded or were outside the legal response period corresponded mostly to the ministry of health, which was overburdened with the health emergency. On the other, the government performance suggests that the Fala system, which was introduced during the pandemic, helped ministries cope with the administrative burden of requests. However, the provisional measure in itself reveals the lack of legal framework for ensuring ATI during a crisis context.

The Mexico City Protocol for access to information in times of crisis

Following an earthquake in 2019 and the COVID-19 Pandemic in 2020, the government of Mexico City decided to create a protocol for access to information and transparency in times of crisis. In sum, it outlines the minimum actions for transparency in emergency situations, by bodies subject to the ATI law, by oversight bodies, and by people and communities in each of the stages of a risk situation: prevention, reaction and recovery. These actions can include the digitization of documents, identifying which information should be published and disseminated during the emergency situation and how to monitor and evaluate emergency ATI actions.

To create the Protocol, the government conducted an open and participative process. First, it carried out 6 co-creation tables with multi-stakeholders to co-design a preliminary draft of ideas, proposals and definitions to be included in the Protocol. Second, in collaboration with the National Centre of Disaster Prevention and external specialists on risks management, the content for the Protocol was elaborated. For this stage, 3 co-creation tables with multiple stakeholders were made to revise the content in a collaborative way and agree on a final document. Third, once the Protocol was launched, a toolkit was co-elaborated with stakeholders to help different actors implement the Protocol. It is written in plain language and reflects different needs of all sectors of society. It is also adaptable to any crisis context and provides recommendations to avoid the circulation of fake news during a crisis.

Sources: (Regional Alliance for Freedom of expression and information, 2020[72]) http://www.alianzaregional.net/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/Saber-M%C3%A1s-XI-2020-3.pdf; (Federal Government of Brazil, 2021[73]) https://www.gov.br/acessoainformacao/pt-br/lai-para-sic/politica-monitoramento/informe-lai-covid-19; (InfoCDMX, 2021[74])

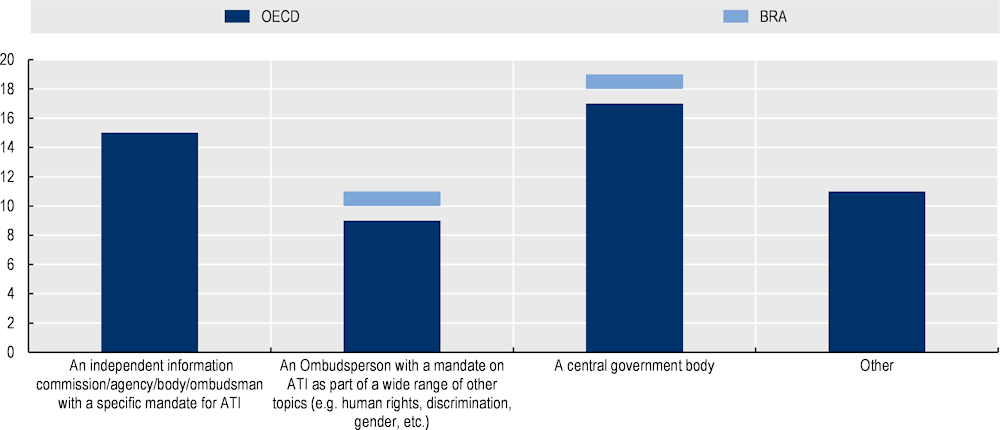

Further efforts are needed to consolidate reactive disclosure in other branches and levels of government