Professional tertiary education is a key component of country skills systems. This report compares this sector across OECD countries, drawing on both qualitative and quantitative data. This chapter introduces the report by describing the diverse forms of the sector in different countries, including, for example, short-cycle tertiary education; professional examinations designed to upskill experienced practitioners, and professional bachelor’s programmes at level 6. Currently our data on this type of provision have major gaps, because of the lack of internationally agreed definitions. This chapter proposes a three-way classification to resolve this problem, distinguishing first, programmes that prepare students for a particular profession, second, programmes that prepare students to work within an occupational family or industrial sector, and third, programmes in the pure sciences, humanities and arts. The chapter concludes by setting out a set of practical tools to implement this proposal and thereby improve data availability.

Pathways to Professions

1. Measuring professional tertiary education in comparative data

Abstract

Introduction

The diversification of tertiary education

The connection between universities and professional education and training is hardly new in history. In the Middle Ages some types of professional training took place in universities. Universities in Europe in the 13th century were expected to teach not only the “Seven Liberal Arts”, but also law, medicine or theology (Rait, 1918[1]). However, by the middle of the 19th century, universities became focused on liberal education and pure research, leaving professional preparation outside their walls. The emergence of “modern” higher education towards the second half of the 19th century and the early 20th century produced a shift from small, homogeneous universities to a diversified and increasingly professional system of higher-level learning (Jarausch, 1982[2]). In the 19th century, various countries established institutions with a professional focus (e.g. polytechnique in Canada, university-based professional schools in the United States). In the 20th century and particularly accelerating over the decades following World War II, the purpose of higher education as preparation for specific professions became embedded in new types of programmes and institutions (Lazerson, 2013[3]). New types of higher education institutions, such as universities of applied sciences and polytechnics, emerged in many European countries with less focus on research and more on applied learning (Teichler, 2002[4]). Even in countries that maintained or moved to a unified higher education system, such as Australia, New Zealand, the United Kingdom or the United States, the expansion of higher education and the diversification of student body was accompanied by increasing sensitivity to labour market needs (McInnis, 1995[5]; Lazerson, 2013[3]).

In response to these developments, many tertiary programmes have become increasingly connected to employment opportunities. At bachelor’s level, many countries have developed programmes focusing on applied, occupationally-oriented learning, offered either in a separate tier of institutions or within multi‑purpose higher education institutions. In the United States, for example, undergraduate education shifted from a focus on arts and sciences to occupational-professional degrees over the second half of the 20th century (Brint et al., 2005[6]). Some countries have established designated professional bachelor’s programmes targeting specific professions or occupational fields.

The diversification included also the development of shorter education and training programmes, as many of the emerging occupations required less than a traditional three- or four‑year university qualification. For example, in the medical field programmes were established for medical assistants, physical therapists and radiological technicians. In the legal domain, programmes emerged to train paralegals and legal secretaries, while the field of engineering developed offers for engineering technicians (Lazerson, 2013[3]). Such shorter programmes leading to such “sub-degree” or “sub-bachelor” qualifications have greatly contributed to the expansion of higher education in the United Kingdom (Schuller, 1995[7]) and the United States (Lazerson, 2013[3]). These short-cycle tertiary programmes have often become not only a route to an entry-level job, but also a stepping stone into further learning at bachelor’s level.

Another sector of the tertiary professional landscape evolved from upper secondary vocational education and training (VET), rather than from traditional university education, and is sometimes associated with crafts and trades with a long history of “Meister” qualifications. Several countries have developed programmes that provide a way for upper secondary vocational students to deepen their skills and knowledge. These take the form of one-or two‑year programmes or qualifications based on an examination (e.g. master craftsman examinations, professional examinations).

Even over the past two decades, applied and professional programmes grew in several European countries, contributing to the increase in tertiary attainment of young adults across Europe. A study of “higher VET” in Europe (Ulicna, Luomi Messerer and Auzinger, 2016[8]) found that between 2000 and 2013 participation in these programmes grew in 12 countries, remained stable in six countries and decreased in nine countries. For example, enrolment in higher vocational programmes grew by 39% in Spain and by 25% in the French speaking community of Belgium. Programmes provided by universities of applied sciences grew also substantially in many countries, with an increase in enrolment by 112% in Austria, 29% in the Netherlands and 17% in Belgium-Flanders, while growth occurred also in professional higher education in Estonia (30%) and dual study programmes in Germany (57%). Box 1.1 complements the picture by providing some insights on the evolution of professional programmes over the past decades, comparing the highest qualification attained by adults of different ages1. The data are based on the International Standard Classification of Education (ISCED) and refer to the highest qualification of adults. For example if graduates of ISCED 5 programmes progress more often to ISCED 6, then ISCED 5 as highest attainment will become less common even if participation remained unchanged.

Box 1.1. Changes over time: Professional attainment among younger and older adults

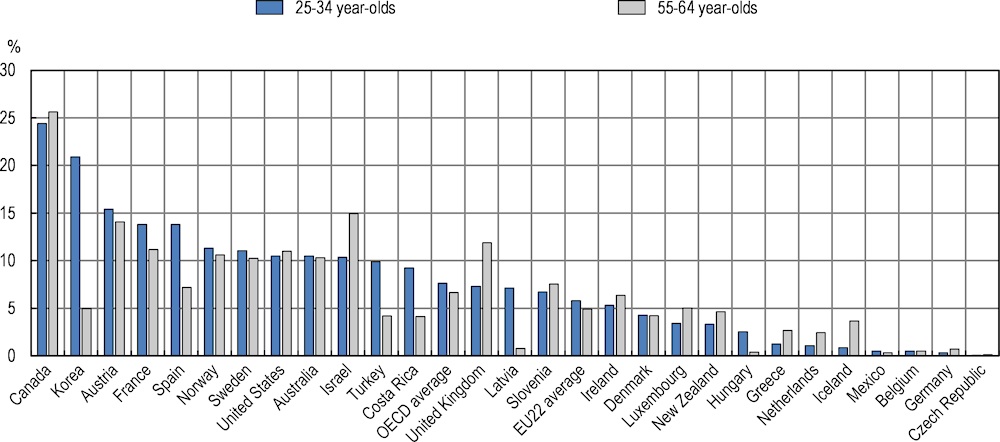

In several countries short-cycle tertiary education has expanded (e.g. Korea, Spain), but in many countries short-cycle tertiary education remains very uncommon (e.g. Belgium, the Czech Republic, Germany, Iceland and Mexico).

Figure 1.1. Share of younger and older adults with a short-cycle tertiary qualification (2019)

Note: Highest level of education completed is a short-cycle tertiary qualification, regardless of programme orientation.

Source: OECD (2021[9]), “Education at a Glance”, Education and Training – Education at a Glance (database), https://stats.oecd.org/

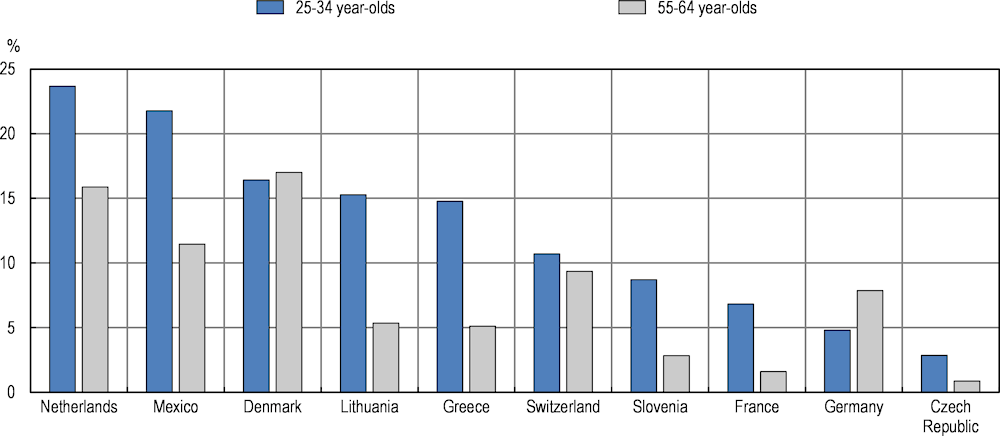

In most countries with data, holding a professional ISCED 6 qualification has become more common. Such qualifications are held by at least 15% of young adults in Denmark, Greece, Lithuania, Mexico and the Netherlands. The Netherlands has the highest share of younger adults with a professional ISCED 6 qualification (24%), following the rapid growth in universities of applied sciences (HBO).

Figure 1.2. Share of younger and older adults with a professional bachelor's or equivalent professional qualification (2019)

Note: Data are based on national definitions of programme orientation. Highest level of education completed is a professional bachelor's or equivalent professional qualification.

Source: OECD (2021[9]), “Education at a Glance”, Education and Training – Education at a Glance (database), https://stats.oecd.org/.

The added value of comparative data on professional tertiary education

The development of tertiary programmes and dedicated institutions that deliver higher level technical, professional skills has occurred in a context of rapid technological change and labour markets shaped by job polarisation. Throughout the past century, technological change reshaped labour market in a way that has favoured workers with higher skills, leading to skill-biased technological change. Later on, evidence emerged of a distinction between how routine and non-route tasks are affected: routine tasks are increasingly replaced by automation, leading to routine-biased technological change. As a result of these trends, job polarisation has been observed for several decades, with jobs requiring mid-level skills becoming less important in labour markets, alongside growth in both occupations with high skills requirements (e.g. engineers, medical doctor) and in those with low skill requirements (but difficult to automate, such as providing basic care for the elderly). According to projections from Cedefop and Eurofound (2018[10]), job polarisation is expected to continue over the next decade. Forecasts suggest that employment growth will be strongest for professionals, technicians and associate professionals. Employment for managers, service and sales workers, and elementary occupations will grow but more slowly. By contrast, employment in occupations that might be considered “middle skilled” is expected to fall – this includes craft and related trades workers, clerks and skilled agricultural workers (OECD, 2020[11]).

Across OECD countries, automation is expected to replace 14% of jobs in the coming years and significantly reshape another 32%. The new jobs created will also have different skills requirements from those that disappear (OECD, 2019[12]). There are multiple implications for skills systems. First, initial education and training programmes can no longer be designed to prepare for an occupation that a person would pursue throughout their entire career. Education and training systems must ensure that individuals are equipped with the skills needed to pursue further learning. This is particularly important for vocational education and training systems, which used to be designed to prepare for jobs rather than further learning and have often neglected generic skills, in particular literacy and numeracy. Second, skills systems must provide suitable learning opportunities to those seeking advanced occupational skills, including adults who need to upskill or reskill. Programmes need to be organised in an adult-friendly way, allowing adults to build on their previous experience, fill any specific gaps in their skill set and pursue studies in a way that is compatible with other demands on their time (e.g. work, care responsibilities).

Several countries turn to tertiary programmes with a focus on applied learning and close connection to the labour market to deliver this – such programmes are sometimes part of a distinct sector referred to as “higher vocational education and training” or professional tertiary or higher education. Countries often view such programmes as an important means of widening access to tertiary education, engaging graduates of upper secondary VET programmes and more broadly, non-traditional tertiary students.

Against this background, there is a major policy debate about the best way in which to prepare people for not only a first job, but also a lifelong career and successful participation in society – and more broadly, about the type of education and training that can help achieve the desired mix of skills in an economy and society. When entering the labour market, all young people need skills and qualifications to find a first job. An initial smooth transition is important as it tends to have a long-term impact on career prospects (e.g. (Gregg and Tominey, 2005[13]; Möller and Umkehrer, 2014[14]; Ayllón, Valbuena and Plum, 2021[15])). Moreover, some labour market trends, including growth in outsourcing and temporary work, reduce incentives for employers to provide on-the-job training, particularly for those in entry-level jobs. As a result, there is an increasing need for the initial education and training system to equip young people with specific professionally-oriented skills, as well as general education. A practical approach, often including work‑based learning, can help develop not only specific, technical skills but also broad employability skills, like teamwork and communication. Employers across Europe view a combination of professional (or sectoral) and interpersonal skills as essential when considering the recruitment of recent higher education graduates (Cedefop, 2014[16]).

On the other hand, it is sometimes argued that it is best to prepare young people for work and life with general education, rather than vocational or professional training. Such general education is designed to develop sound generic skills and ensure individuals have the capacity to adapt to changing circumstances, needed both to pursue a successful career and to function in society. The argument is that more specific knowledge and skills can then be acquired post-qualification and on the job (for a review of the literature on this debate see (Biewen and Thiele, 2020[17]).

In practice, programmes come in shades of grey, rather than black and white: all professional programmes need a large measure of general education, in particular literacy and numeracy, while general and academic programmes also develop skills that are of labour market relevance. But the broad question remains about the proportion of tertiary education programmes that should take a target occupation (or target occupations) as their point of departure and the proportion that should remain in more academic fields. There is no easy answer to this debate, but the first step is to monitor what countries are doing in this area, to improve the quality of comparative data to allow for analysis and research.

Comparative data can also shed light on the role of professional programmes in national skills systems. In some countries higher VET or professional tertiary education is viewed as a key tool to open access to tertiary education to graduates of upper secondary VET, students from lower socio-economic backgrounds and facilitate the massification of tertiary education. One of the objectives of the European Education Area is to increase the share of 30-34 year-olds with tertiary education to 50% by 2030 – professional programmes can help achieve this target by attracting those most interested in applied forms of learning.

This project was launched to help improve comparative data on professional tertiary education and to inform policy making in this area through better data. Box 1.2 describes the objectives and the methodology of the project.

Box 1.2. About the project: Higher VET – professional tertiary education

Objectives

The objectives of the project were to inform policy development in the area of tertiary programmes with professional orientation based on international experience; explore possibilities to enhance the coverage of professional programmes in existing and future data collections; and stimulate dialogue on an international definition and classification of tertiary programmes by orientation.

The scope of the project includes programmes at ISCED levels 5-7, with most of the analysis focusing on ISCED 5 and 6 programmes.

Methodology

The work has involved:

Desk-based analytical work: reviewing available evidence on country systems, policy and practice, assessing the quality of comparative data (e.g. OECD Survey of Adult Skills (PIAAC), data collected through the Indicators of Education Systems (INES) Working Party and its networks, European Union Labour Force Survey) and analysing comparative data.

Dialogue with countries through the Ad hoc Working Group on Professional Tertiary Education: Countries and international organisations (members of the Group of National Experts (GNE) on VET, the Higher Education GNE, the INES Working Party and the Network on Labour Market, Economic and Social Outcomes (LSO) were invited to join this group to discuss key policy issues, enrich the project with information on professional programmes across OECD countries and discuss issues regarding potential internationally agreed definitions for programme orientation at tertiary level. 27 countries and six international organisations joined the group.

Data collection on professional tertiary education: OECD member countries and key partners, as well as non-OECD EU member states and candidate countries, were invited to complete a questionnaire, composed of two parts. Part A sought to complement existing information in ISCED mappings and earlier surveys, with a view to explore the workability of potential internationally agreed definitions for programme orientation. Part B sought to collect examples of policy and practice in the area of professional tertiary education. 37 countries completed the questionnaire.

The summary of country participation in the Ad hoc Working Group on Professional Tertiary Education is provided in Annex A (Table A A.1).

The coverage of comparative data by level of tertiary education

This section describes the programmes and qualifications currently covered by comparative data on professional tertiary education.

Professional programmes under the ISCED 2011 framework

The basis for the identification of professional tertiary programmes in comparative data is the International Standard Classification of Education (ISCED) 2011 framework. It allows for the identification of professional programmes at all tertiary levels, but its potential has not been fully realised. Under the earlier framework (ISCED 97), tertiary education was identified at levels 5 and 6. Level 6 was reserved for advanced research qualifications, such as Ph. D programmes, so the vast majority of tertiary programmes, including those at master’s level, were at level 5, subdivided into 5A and 5B. 5B programmes were defined as being “practically oriented/occupationally specific” and “is mainly designed for participants to acquire the practical skills, and know-how needed for employment in a particular occupation or trade or class of occupations or trades” (UNESCO, 2006[18]). Despite this last definition, under ISCED 1997, ISCED 5A included not only more theoretical studies in the pure sciences and humanities, but also longer training programmes for professions such as medicine and architecture that have “high skills requirements”. This left ISCED 5B, uncomfortably, covering professional programmes other than those with high status.

ISCED 2011 sought to resolve this issue through greater disaggregation of different levels of tertiary education, and by allowing that at each of these levels, programmes might have a different “orientation”, with proposed categories of orientation being “professional” or “academic”. ISCED 2011 offers four tertiary levels: short cycle tertiary (ISCED 5), and the three “Bologna” categories: bachelor’s (ISCED 6), masters (ISCED 7) and doctoral (ISCED 8). Orientation is identified in the second digit of ISCED’s 3-digit coding, so that, for example, a bachelor’s degree is coded as 64 if academic, 65 if professional, and 66 if orientation is unspecified (UNESCO, 2012[19]). As professional programmes are available at all tertiary levels, the characteristic of being professional has no implication for the status or length of the programme.

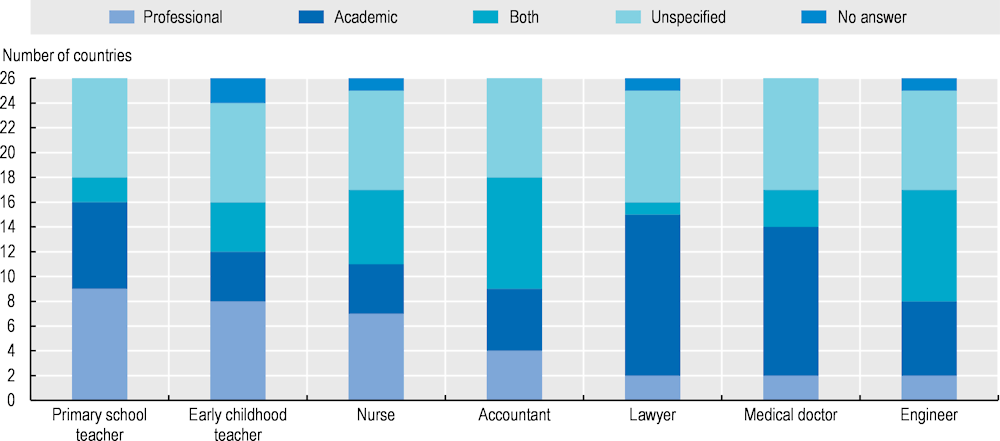

But a major difficulty remains, in that there are not, as yet, internationally agreed definitions of “academic” or “professional” that would underpin the collection of comparative data. For ISCED level 5 it has been agreed to use the definition adopted for “vocational” programmes at lower ISCED levels. For ISCED levels 6 and above countries have been able to report a breakdown by orientation based on their own definitions of “professional” and “academic” or report programmes as having “unspecified orientation”. One consequence is weak comparability: as illustrated by Figure 1.3, programmes preparing students for the same occupation are reported as academic in some countries, as professional or having “unspecified orientation” in others. While some of the variation may reflect real differences in the way in which individuals are prepared for the same professions in different countries, an undetermined and potentially large proportion of the variation involves unmeasured differences in definitional approaches. The implications for data coverage and quality at each ISCED level are discussed in the next section.

Figure 1.3. Academic or professional? Current classification for selected occupations

An additional limitation of data collected under the ISCED framework is that they do not cover qualifications delivered outside the formal education and training system. In some countries such programmes (e.g. industry-led certifications) play a major role in preparing for advanced, technical occupations. For example, in the United States, examinations for master plumbers lead to a certificate of licensure, but not a formal educational qualification (similarly to the apprenticeship system, which is also outside the formal education system). Some certifications are developed by large companies or groups of companies (e.g. certification by Cisco or Caterpillar). Similarly, France has a large system of professional qualification certificates (CQP‑s), which are part of a national register but are not considered formal education. Such industry-led certifications are very often not captured in comparative data – they are included only when a programme leads to both a formal qualification and an industry-recognised certification.

Recognising that the European Qualifications Framework (EQF) is commonly used as a reference for policy making and research in Europe, Box 1.3 describes the relationship between the two frameworks.

Box 1.3. The relationship between ISCED and EQF levels

The European Qualifications Framework (EQF) and the ISCED frameworks focus on different constructs and play different roles. The ISCED framework is designed to classify education and training programmes. The EQF is a reference framework for qualifications. It focuses on learning outcomes (knowledge, skills and competences), which may be achieved through different paths, including formal programmes, non-formal and informal learning. While there is no official equivalence table between ISCED and EQF levels, a loose correspondence exists: a qualification at a higher EQF level is likely to correspond to a programme provided at a higher ISCED level (European Commission, 2008[20]). Drawing on a recent overview of national VET systems in Europe by Cedefop, Table 1.1 sets out how programmes in different countries are situated on the ISCED and the EQF framework respectively. While higher ISCED levels are associated with higher EQF levels, there is variation across countries and programmes in which EQF level is associated with a particular ISCED level. For example, in Poland some five-year upper secondary vocational programmes (ISCED 3) lead to an EQF 4 qualification, while 3-year sectoral programmes (also ISCED 3) lead to a EQF 3 qualification. ISCED 5 business academy programmes in Denmark lead to EQF 5 qualifications, while in the Czech Republic performing arts programmes (also ISCED 5) lead to EQF 6 qualifications.

Table 1.1. The position of vocational or professional programmes in European countries

|

ISCED level of the programme |

EQF level attributed to the qualification |

|---|---|

|

2 |

1, 2,3 |

|

3 |

2, 3, 4 |

|

4 |

4, 5 |

|

5 |

5, 6 |

|

6 |

5, 6 |

|

7 |

7 |

|

8 |

8 |

Source: Synthesis based on information provided in Cedefop (2021[21]), Spotlight on VET - 2020 compilation: vocational education and training systems in Europe, http://data.europa.eu/10.2801/10.2801/667443; European Commission (2008[20]), Explaining the European Qualifications Framework for Lifelong Learning, https://europa.eu/europass/system/files/2020-05/EQF-Archives-EN.pdf.

This report draws on several sources of comparative data, most of which build on the ISCED 2011 framework (see Table 1.2 for an overview). Some allow for a breakdown by programme orientation at several tertiary levels, in line with the detailed ISCED classification (i.e. the Unesco-OECD-Eurostat [UOE] and LSO data collections, and the “Data collection on professional tertiary education”). In addition, data sources that do not allow for such a breakdown can provide useful insights in two ways. First, some sources (e.g. European Union Labour Force Survey [EU-LFS]) allow for the identification of ISCED 5 programmes, which are predominantly professional (see below). Second, some sources (e.g. EU-LFS, “Ad hoc survey on tertiary completion”) provide insights on the pathways pursued by graduates of upper secondary VET, in particular their entry and progression through tertiary education. Given that in some countries professional tertiary programmes are extensively used by upper secondary VET graduates, this analysis provides insights that are relevant for professional programmes in those countries. All data sources are based on surveys, with the exception of the UOE data collection, which draws on administrative data.

Table 1.2. Sources of comparative data on professional tertiary education

|

Data source |

Availability of data by orientation |

How are data used? |

|---|---|---|

|

UOE, LSO regular data collections |

Yes, based on ISCED 2011 |

Professional programmes identified as all ISCED 5 programmes and ISCED 6 programmes currently reported as professional. Issues in focus: entry, enrolment, graduation, attainment and labour market outcomes in professional programmes. |

|

Ad hoc survey on tertiary completion |

No (only for prior upper secondary qualification) |

Focus on ISCED 6 students with a vocational background, recognising the common use of professional programmes as a learning pathway for VET graduates. Issues in focus: share of students with a vocational background, completion rates. |

|

Data collection on professional tertiary education |

Yes, based on ISCED 2011 |

Professional programmes identified as all ISCED 5 programmes and ISCED 6 programmes currently reported as professional. Issues in focus: programme characteristics, data availability. |

|

EU-LFS |

No |

Professional programmes identified as all ISCED 5 programmes. Issues in focus: progression patterns between levels of education, participation in work-based learning and employment outcomes.2 |

|

Survey of Adult Skills (PIAAC) |

Yes, based on ISCED 97 |

Only ISCED 5B programmes can be identified, which correspond loosely to ISCED 5 programmes under the ISCED 2011 framework. Issues in focus: literacy and numeracy skills, links between field-of-study and subsequent occupation. |

Most data from the UOE and LSO regular data collections were collected for Education at a Glance 2020, the latest data collection available for this project. The “Ad hoc survey on tertiary completion” was carried out for Education at a Glance 2019 and data are used in this report to analyse the progression of VET graduates in tertiary education (ISCED 6 only). The “OECD Data collection on professional tertiary education” was conducted for this project in 2021, to understand what is currently reported as professional, identify the possibilities and constraints countries face when reporting data, as well as providing qualitative information on professional programmes.

In addition, the analysis draws on data from the European Union Labour Force Survey (EU-LFS) and the Survey of Adult Skills, a product of the Programme for the International Assessment of Adult Competencies (PIAAC), .These sources do not allow for a breakdown by orientation, but allow for the identification of ISCED 5 programmes and ISCED 5B programmes respectively. EU-LFS data are used to analyse the progression of VET graduates into tertiary education, while the Survey of Adult Skills (PIAAC) provides insights into outcomes from tertiary education.

Box 1.4 sets out how this report uses different terms to refer to the orientation of tertiary programmes.

Box 1.4. Terminology used in this report

This report uses the term professional to refer to all programmes at ISCED level 5, regardless of their current classification in international data collections. For ISCED levels 6 and 7, this report refers to programmes as “professional” (or “academic” or having “unspecified orientation”) based on how they are classified in ISCED mappings and related international data collections. The terms sector-oriented and profession-oriented are used in this report as described in the proposals for internationally agreed definitions in this chapter.

This report refers to professional tertiary programmes, as this term is used in the current ISCED framework. Other commonly used terms exist – higher VET in particular is often used, especially across Europe to refer to postsecondary and tertiary programmes with professional orientation. The definitions proposed in this chapter for sector-oriented and profession-oriented programmes is consistent with the broad definition of higher VET proposed by a recent European study (Ulicna, Luomi Messerer and Auzinger, 2016[8]), as they also include programmes covered by the European Higher Education Area. Finally, the terms professionally-oriented and applied are used in this report when used in the relevant context by the countries concerned (e.g. universities of applied sciences, professionally‑oriented degrees).

Short-cycle tertiary qualifications – ISCED level 5

The availability of comparative data

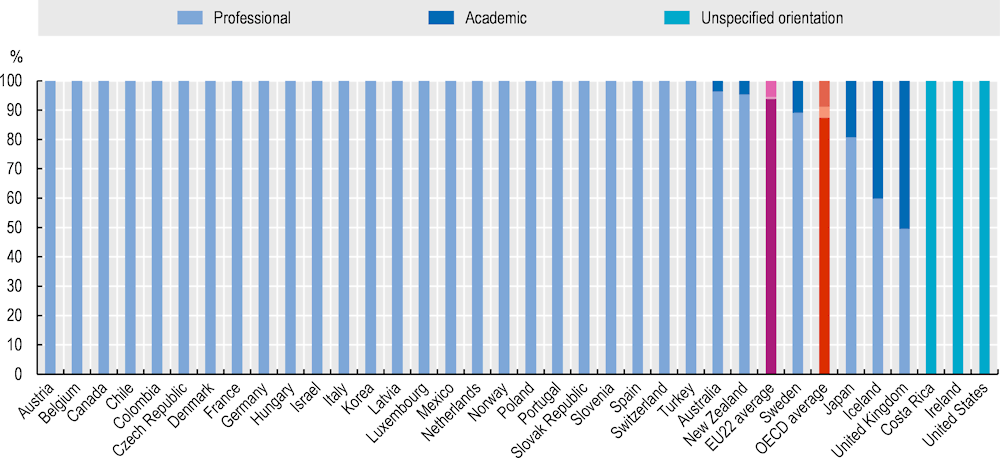

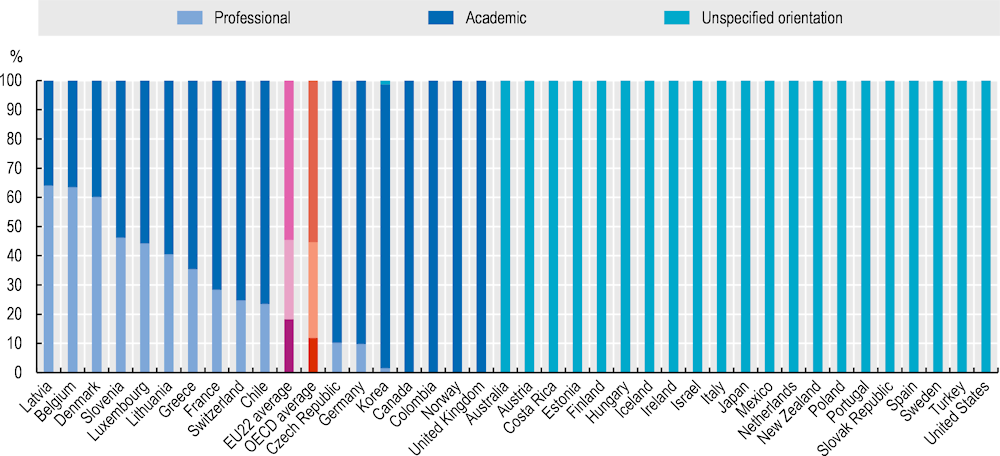

Both country coverage and comparability of data at ISCED level 5 are good. Data collections for “professional” programmes at this level are based on the internationally agreed definitions of ‘vocational’. Across OECD countries, the vast majority of students enrolled at level 5 pursue programmes classified as professional (Figure 1.4). Many of the remaining programmes appear to be professional despite being classified otherwise. For example, in the United Kingdom a recent mapping of the ISCED 5 landscape found it was mostly professional (Boniface, Whalley and Goodwin, 2018[22]) and programmes classified as “academic” include for example, training for paramedics, nurses and social workers. The classification choice is based on the provider institution, so that all programmes delivered in universities are reported as “academic”. Similarly, in Iceland one of the two programmes in the academic category is called “short practical programme”. Three countries report all students at this level in programmes with “unspecified orientation”. In Ireland this level is composed of higher certificates, which appear to have a professional focus – they are offered in fields like accounting, business and property management (Courses.ie, 2021[23]). Similarly, in Costa Rica the two programmes reported at this level are “higher technical education” and teacher training. The United States is an exception in the sense that associate degrees include a mix: around 40% of associate degrees are conferred in the field of liberal arts and sciences, general studies and humanities (e.g. mathematics, geography), while the remaining 60% are within applied fields (e.g. business, health professions, engineering) (NCES, 2021[24]). The considerable share of qualifications in non-professional fields might be explained by the fact that in the United States associate degrees are commonly used as a stepping stone into bachelor’s programmes (see Box 2.1 in Chapter 2).

Figure 1.4. Distribution of students by programme orientation at short-cycle tertiary level (2018)

Note: Data are based on national definitions of programme orientation.

Source: OECD (2021[25]), “Education at a Glance”, Education and Training – Education at a Glance (database), https://stats.oecd.org/.

Recognising that the vast majority of ISCED 5 students are in programmes that are professional at least in some sense, this report treats all programmes at this level as professional, regardless of their current classification. This approach has two advantages. It allows data by tertiary level to be compared meaningfully even when a breakdown by orientation is not possible. In addition, it broadens the country coverage of the analysis to include Costa Rica, Ireland and the United States. Given this approach, there is no impact in the 25 countries where all students are reported in professional programmes. In the remaining nine countries this approach may overestimate professional enrolment (in particular in those where a non-negligible proportion of the level 5 programmes appear to be non-professional, as in the United States). The internationally agreed definition for vocational programme orientation is used by countries in their data reporting, but the term “professional” is used in our analysis for simplicity and in line with the ISCED 2011 recommendation to use the term “professional” for all levels of tertiary education.

Common types of qualifications covered by comparative data

Associate degrees and short higher vocational programmes

Short-cycle tertiary qualifications are very often two years full-time, with options for articulation into bachelor’s degrees at the same institution (or the same type of institution) and a considerable share of graduates pursue higher level studies (see Chapter 2 on pathways). Across countries, this category includes associate degrees taught in universities of applied science in Belgium-Flanders, associate degrees (BES qualifications) in the French Community of Belgium, Higher National Qualifications in Scotland (United Kingdom), foundation degrees in England (United Kingdom) and college diplomas in Canada (see Table 1.3). Some programmes are closely connected to upper secondary education and are provided within the same institutions as upper secondary VET programmes – examples include Austrian BHS programmes in which the programme (years 4 and 5) follow-up on three-year upper-secondary programmes in the same colleges.

Table 1.3. Short-cycle tertiary qualifications

|

Country |

Programme / qualification |

Provider institution |

Typical duration (years) |

Articulation with higher level programmes |

Targeted fields |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Austria |

Grades 4-5 in (higher technical and vocational colleges (BHS) |

Higher technical and vocational colleges (BHS) |

2 |

Possibility to pursue higher education at a university or university of applied science. |

Various (e.g. Technology, Business Administration, Fashion, Artistic Design, Tourism, Agriculture and Forestry, Early Childhood Pedagogy and Social Pedagogy) |

|

Belgium-Flanders |

Associate degree |

University colleges |

1.5-2 |

Possibility to transfer to professional bachelor’s programmes. |

Various (e.g. architecture, arts, biotechnology, healthcare, business, education) |

|

Belgium-French community |

Associate degree (Brevet d'enseignement supérieur) |

Specialised adult learning institutions (établissements d’enseignement supérieur de promotion sociale) |

2 |

Credits are recognised in short bachelor’s programmes delivered in 'hautes écoles', écoles supérieurs des arts et établissements d'enseignement supérieur de promotion sociale. |

9 programmes proposed : literacy trainer, general stage manager, commercial unit manager, advisor in personnel administration & management, tour guide - regional guide, webdesigner, webdeveloper, socio-professional integration advisor, animator in collective political, cultural & social action. |

|

Canada |

Undergraduate diploma/certificate; college diploma; advanced/applied certificate or diploma; post certificate or diploma; AVS |

Various (e.g. public colleges, specialized institutes, community colleges, institutes of technology and advanced learning, and CÉGEPs) |

1-3 |

|

Various (e.g. business, health, science, agriculture, applied arts, technology, skilled trades, and social services) |

|

Chile |

Higher technician |

Professional training centres, Professional institutes |

m. |

Possibility to progress to 4-year programmes offered within the same institution. |

m. |

|

Czech Republic |

Conservatoire programmes |

Conservatoire |

2 |

m. |

Performing arts (music, singing, drama). |

|

Denmark |

Business academy programmes |

Business academies |

2 |

In some programmes students have the option of pursuing a top-up degree of 1.5 years to obtain a professional bachelor’s degree. |

Wide range of fields (e.g. automotive technology; design, technology and business; computer science; and various areas of management (logistics, marketing, service, hospitality and tourism). |

|

France |

Brevet de technicien supérieur (BTS) |

Vocational upper secondary school or higher institute. |

2 |

m. |

m. |

|

Israel |

Initial training for technicians and practical engineers, job training programmes. |

High schools, vocational training centres, colleges for practical engineers |

m. |

m. |

m. |

|

Italy |

Professional tertiary education |

Higher technical institutes |

2-3 |

m. |

6 technological areas: Energy efficiency, Sustainable mobility, New technologies for life, New technologies for “Made in Italy”, Information and communication technologies, Innovative technologies for cultural heritage and activities - Tourism |

|

Korea |

Junior college course |

Junior colleges |

m. |

m. |

m. |

|

Latvia |

Short-cycle higher education |

Colleges |

m. |

m. |

m. |

|

Luxembourg |

Brevet de technicien supérieur (BTS) |

High schools |

2 |

m. |

Applied arts, trade, industry, health, services, wood technology. |

|

Luxembourg |

Continuing education for existing professionals |

Universities |

m. |

m. |

m. |

|

Netherlands |

Associate degree |

Universities of applied sciences |

2 |

m. |

Business & management, technology, education, IT, care and welfare etc. |

|

Norway |

Vocational college programmes |

Vocational colleges |

2 |

Upon completion, students with a vocational upper secondary qualification gain access to universities and university colleges. |

Programmes prepare master craftsmen, skilled technicians or para-professional occupations. Most students are graduates of upper secondary VET in technical fields, health or welfare. |

|

Portugal |

Vocational and technical higher education courses (CteSP) |

Polytechnics |

2 |

Articulation with bachelor’s programmes. |

Digital technology and arts, IT, Technology, Management, Art, communication and culture. |

|

Slovenia |

Short-cycle higher VET |

Higher vocational colleges (most are part of upper secondary school centres) |

2 |

m. |

32 target professions |

|

Spain |

Higher vocational programmes leading to 'higher technician' qualifications. |

m. |

2 (3 if dual training) |

m. |

Various (e.g. Healthcare, Management, Hospitality, Electronics, Arts and design, ICT). |

|

Sweden |

Advanced diploma in higher VET |

Different providers, mostly private organisations |

2 |

m. |

m. |

|

United Kingdom |

Higher National Certificate |

Colleges, training providers, some universities |

1 |

Possibility to enter into the second year of a degree programme |

Wide range of subjects, e.g. business administration, computing, engineering, health and social care, social sciences. |

|

United Kingdom |

Higher National Diploma |

Colleges, training providers, some universities |

2 |

Possibility to enter into the third year of a degree programme |

Wide range of subjects, e.g. business administration, computing, engineering, health and social care, social sciences. |

Note: The list of qualifications is not exhaustive, additional qualifications may exist in some countries. m.= missing

Source: OECD Data collection on professional tertiary education.

Professional examinations

Some ISCED 5 qualifications are delivered following a professional examination. Box 1.5 describes the general approach of professional examinations, which exist in several OECD countries and yield qualifications at several tertiary levels depending on the country and target occupation. At ISCED 5, Austria has examinations following preparation in a Meisterschule. In Germany meister examinations that follow a short preparatory programme lead to level 5 qualifications and the title “Certified occupational specialist”, and are available in a range of target occupations (e.g. opticians, plumbers and heating engineers).

Box 1.5. Professional examinations: Advanced qualifications based on an examination

Professional examinations exist in some form in several OECD countries. They are designed to upskill those already working in a profession, typically with an earlier vocational qualification in the field. One of their key characteristics is that they do not require any specific programme of preparation, although having several years of relevant work experience is a common requirement. In several countries such examinations are led by industry at the national level, leading to a qualification that is standardised and unique at national level. These qualifications and the (often optional and unregulated) programmes that prepare candidates are reported in ISCED mappings and captured by comparative data. They lead to qualifications at ISCED levels 5, 6 and 7 depending on the country and the target occupation. Examinations have traditionally led to meister qualifications for traditional VET occupations, preparing for example qualified electricians and plumbers to run their own business and train apprentices. Mirroring developments within the VET system, qualifications have diversified in terms of targeted sectors and are now available in sectors like healthcare, IT and finance.

Germany: Professional examinations are a common entryway to higher professional and management positions. An initial vocational qualification within the same or related field is a prerequisite, but it may be replaced by several years of relevant work experience. They exist at three levels: short programmes (less than 880 hours of preparatory coursework) yield the title “Certified occupational specialist” (ISCED level 5), longer master craftsmen programmes yield the title “Bachelor Professional” (ISCED level 6). In addition ISCED level 7 examinations were introduced recently and lead to the title Master professional.

Switzerland: Federal professional examinations lead to a Federal Diploma of Higher Education (ISCED level 6) or Advanced Federal Diploma of Higher Education (ISCED level 7). They are intended for professionals who have completed upper secondary VET and seek to improve their knowledge and skills, or develop specialised skills. Candidates may pursue preparatory courses for the examinations and they typically do so while continuing to work in the corresponding field. The courses are not regulated, as they are optional. Providers of such courses include local authorities, professional organisations, individual or groups of companies, and private education providers.

Source: Kis and Windisch (2018[26]), “Making skills transparent: Recognising vocational skills acquired through workbased learning”, OECD Education Working Papers, No. 180, https://doi.org/10.1787/5830c400-en; OECD Data collection on professional tertiary education; Gewerbeanmeldung.de (2022[27]), Informationen zur Gewerbeanmeldung [Information on business registration], www.gewerbeanmeldung.de/meisterpflicht; SDBB (2022[28]), Das offizielle schweizerische Informationsportal der Berufs-, Studien- und Laufbahnberatung (Le portail officiel suisse d’information de l’orientation professionnelle, universitaire et de carrière), https://www.berufsberatung.ch/.

Programmes delivered outside formal education and training are excluded

In some countries, preparatory courses for professional examinations are excluded. In Austria, for example, preparatory courses outside formal education are not captured by enrolment and graduation data. More broadly, in most countries industry-led certifications, which lead to similar qualifications to professional examinations but without public involvement, are excluded from comparative data collections.

Bachelor’s level qualifications – ISCED level 6

The availability of comparative data

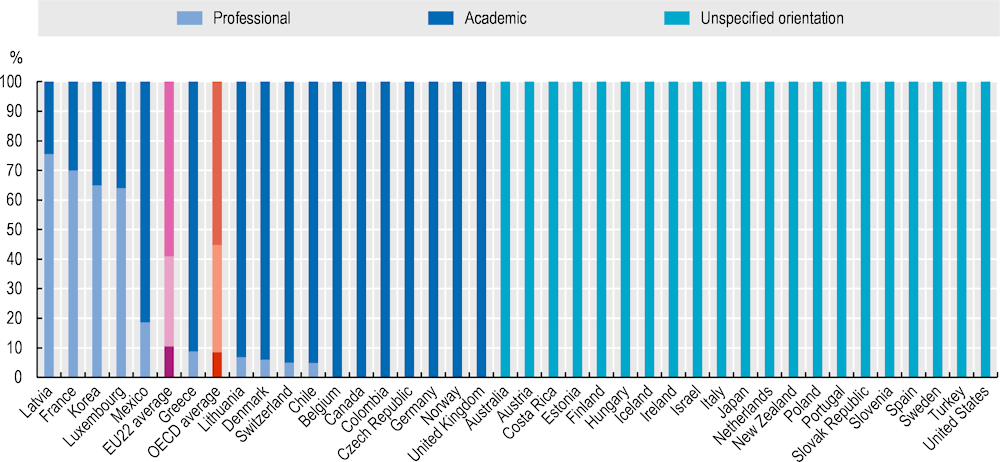

Comparative data on professional programmes at level 6 are available for 15 countries, based on national definitions of programme orientation. About half of OECD countries do not distinguish programmes by orientation at ISCED level 6 and four countries report all of their students in academic programmes. Two reasons are likely to explain this. First, some countries may find the professional-academic distinction less relevant to their system or difficult to implement because they have a unified tertiary system without distinct institutional or programme categories. Second, some countries may prefer not to report a distinction that is possibly ambiguous given the absence of internationally agreed definitions. Among the 15 countries that choose to report professional programmes at this level, some of the variation in the distribution of students is driven by different classification choices for similar programmes (as discussed above, see Figure 1.5).

Figure 1.5. Distribution of students by programme orientation at bachelor’s or equivalent level (2018)

Note: Data are based on national definitions of programme orientation.

Source: OECD (2021[9]), “Education at a Glance”, Education and Training – Education at a Glance (database), https://stats.oecd.org/.

Common types of qualifications covered by comparative data

Professional bachelor’s programmes

Professional bachelor’s programmes, involving professional training through a bachelor’s degree, are increasingly common in Europe (see Box 1.6). They are often taught in dedicated institutions, such as universities of applied sciences or university colleges. They have seen rapid growth in several countries, where enrolment now rivals or exceeds the level of academic bachelor’s degrees (e.g. Belgium, the Netherlands). While some programmes prepare for a single occupation (e.g. nurse, teacher), many take as their point of departure the applications of a particular type of science – for example food technology or business management. This means that they provide the knowledge and skills associated with a family of professions or a particular sector, linked to the application of that type of science.

Box 1.6. Professional bachelor’s programmes

Belgium-Flanders

Professional bachelor’s programmes are only provided by university colleges and are oriented towards professional practice. They provide knowledge and competences required to pursue a profession or a group of professions. Graduates are prepared for immediate labour market entry. A “bachelor after bachelor” course is available as a follow-up to deepen expertise in specific areas. Progression to master level is possible after a bridging programme.

Denmark

Professional bachelor’s programmes are typically provided by university colleges and some business academies, and take three or four years to complete. Most programmes lead to public-sector employment as teacher, nurse or social worker, but programmes are also offered in engineering, information technology, business and media and communication, targeting private sector jobs. Work‑based learning is mandatory and accounts for about a quarter of the programme.

France

Professional bachelor’s degrees (license professionnelle) are open to those who have completed two years of postsecondary studies (120 ECTS) in a relevant field of study (recognition of prior learning is also possible). These one‑year programmes include a mandatory internship (12-16 weeks) and are available in a wide range of fields, such as marketing, communication, human resources and ICT. Progression to master level is possible, but admission is not automatic and requires the presentation of a coherent project. In addition, the newly introduced “bachelor of technology” programmes replace earlier DUT programmes, take three years to complete and may be pursued through a dual pathway. Teaching staff include academics as well as practicing professionals. Programmes on offer are diverse, with examples including industrial engineering, hygiene, safety and environment, business management, social careers, multimedia and Internet professions.

Latvia

Professional bachelor’s programmes may be delivered by universities or university colleges. Their content must be designed according to approved professional standards established at national level. These standards are developed by expert groups, including employers and experts in the relevant field. Fields of study include management and administration, teacher training, ICT, travel, tourism and leisure, elderly care, social work and engineering trades. All programmes include a mandatory internship or one semester of practice.

Lithuania

Professional bachelor’s degrees are oriented towards preparation for professional activity and applied research. They are delivered by colleges of higher education. Professional bachelor’s degrees were introduced in 2007 and replaced Diplomas of Higher Education, which used to indicate the title of the awarded qualification (e.g. physiotherapist, educator) but were not degrees.

Slovenia

Professional first cycle study programmes provide students with the skills and expertise to apply scientific methods to the resolution of complex professional problems. Practical training in a working environment is mandatory. These study programs are based on legislation designed to implement reforms linked to the Bologna process. They take three to four years to complete and consist of 180 to 240 ECTS, similarly to academic first cycle programmes. They may be offered by universities, academies or professional colleges.

Source: MHES (2021[29]), About the university colleges, https://ufm.dk/en/education/higher-education/university-colleges/about-the-university-colleges; OECD Data collection on professional tertiary education; Orientation (2021[30]), Les Bachelors Universitaires de Technologie (BUT) : Guide complet !, https://www.orientation.com/diplomes/diplome-but.

Professional examinations

Professional examinations (see key principles in Box 1.5) are available at ISCED level 6 in a few countries. Box 1.7 provides some examples targeted professions. In Germany examinations at this level cover a range of fields, with bachelor professional titles available for example in procurement, bookkeeping, media, print, event technology. In Switzerland, most professional examinations are situated at ISCED level 6.

Box 1.7. Examples of professional examinations at ISCED level 6

Germany

Mechatronics meisters co‑ordinate ongoing operations, control work processes, manage employees and train apprentices. The preparatory course provides technical knowledge to prepare candidates to take up responsibilities in the planning, optimisation and management of the manufacturing process. The course takes about two years to complete (full-time equivalent four months) and may be followed online, part-time on Saturdays, or full-time during the week.

Certified accountants create, analyse and interpret monthly, quarterly and annual reports and inform management decisions. Admission requires a relevant prior qualification and professional experience. Candidates with over five years of relevant work experience need no prior qualification. The preparatory course is taught by professionals from companies, management consultancies and combine both theoretical knowledge and practice-oriented content. The course takes about two years to complete when pursued parallel to employment and may be pursued in the evenings and weekends.

Switzerland

Audioprothesists adapt hearing aids to the needs of people with hearing impairment, based on the analysis of their medical files and their needs. They choose and adjust the hearing aid and pursue a long-term follow-up of patients (e.g. adjusting the settings of hearing aids, repairing). The preparatory course is composed of two modules of 18 months. Candidates must hold a vocational qualification or upper secondary school certificate and at least three years of professional experience.

International trade experts perform administrative tasks related to the import/export of goods and services. They prepare documents that support a commercial transaction (e.g. credit, insurance and transport arrangements), negotiate the sales conditions (e.g. contracts, timing) and ensure that the financial risks related to new or risky clients are covered. The preparatory course takes around 19 months to complete. Candidates must hold a vocational qualification or upper secondary school certificate and at least two years of professional experience with an emphasis on international trade.

Source: FAIN (2021[31]), Industriemeister Mechatronik IHK – Jetzt IHK-geprüften Meistertitel machen – FAIN [Master tradesperson in the mechatronics industry IHK – Get your IHK-certified master craftsperson title now – FAIN], https://www.fain.de/angebote/industriemeister-mechatronik-ihk; DIHK (2022[32]), Bilanzbuchhalter – Bachelor Professional in Bilanzbuchhaltung [Accountant – Bachler Professional in Balance Sheet Accounting], https://www.dihk-bildungs-gmbh.de/weiterbildung/top-weiterbildungsabschluesse/bilanzbuchhalter; SDBB (2022[28]), Das offizielle schweizerische Informationsportal der Berufs-, Studien- und Laufbahnberatung (Le portail officiel suisse d’information de l’orientation professionnelle, universitaire et de carrière), https://www.berufsberatung.ch/.

In some countries applied bachelor’s programmes are not classified as professional

In various countries, bachelor’s programmes with similarly applied, occupationally-oriented focus are not classified as professional in international data collections. For example, Austria, Germany and Switzerland currently report programmes delivered in universities of applied sciences as academic, while Finland and the Netherlands report them as having “unspecified orientation”. While there are differences in the precise role and nature of UASs in different countries, the descriptions of these institutions suggest they share a number of features with UASs that deliver programmes currently classified as professional. For example, in Austria, the UASs describe programmes as “professionally oriented”, with 3-year bachelor’s programmes offered in fields like Business, Engineering and IT, Social Sciences, Media and Design, Health Sciences (OEAD, 2019[33]). In Germany, the UAS are described as providing academic studies with a practical focus and an “orientation towards vocational requirements” (DAAD, 2021[34]). Switzerland describes its universities of applied science as offering “practice-oriented and application-oriented degree programmes which lead to professional qualifications”. Similarly, in Finland the UAS sector has “the mission to train professionals with emphasis on labour market needs” (studyinfo.fi, 2021[35]) and in the Netherlands UASs focus on the “practical application of arts and sciences” (Study in Holland, 2021[36])and train for a specific profession (TU Delft, 2021[37]). Box 1.8 describes the UAS sector in the Netherlands, which has grown rapidly over the past decades and now enrols more students at bachelor’s level than regular universities.

Box 1.8. Universities of applied sciences in the Netherlands

The Netherlands has a binary system of higher education, with 13 academic universities and 41 universities of applied sciences or hoger beroepsonderwijs (HBO) institutions. Following the implementation of the Bologna process, academic universities reorganised their offer of earlier four‑year programmes into three-year academic bachelor’s programmes typically followed by one or two-year master’s degrees. Programmes provided by UASs remained unchanged in duration but were designated as professional bachelor’s degrees (Allen and Belfi, 2020[38]).

Both types of institutions offer programmes in a wide range of fields with many overlaps but differences in terms of focus. While academic universities focus on research, UAS programmes focus on the practical application of arts and sciences (Study in Holland, 2021[36])For example, Delft University of Technology describes UAS programmes as training for a specific profession while academic programmes focus on an analytical and critical approach to particular disciplines. UAS programmes are designed to apply and improve existing knowledge and involve practice-oriented assignments (TU Delft, 2021[37]).

UASs have played an important role in the expansion of higher education. While academic universities may be accessed only upon completion of the highest upper secondary track, UASs are accessible for completers of other tracks as well (i.e. either HAVO or the highest tier of classroom-based or workplace‑based vocational training) (Allen and Belfi, 2020[38]).

Source: Allen and Belfi (2020[38]), “Educational expansion in the Netherlands: better chances for all?”, Oxford Review of Education, Vol. 46/1, pp. 44-62, https://doi.org/10.1080/03054985.2019.1687435; Study in Holland (2021[36]), Universities of applied sciences, https://www.studyinholland.nl/dutch-education/universities-of-applied-sciences; TU Delft (2021[37]), What's the difference between HBO and WO?, https://www.tudelft.nl/en/education/information-and-experience/preparing-for-a-bachelor/whats-the-difference-between-hbo-and-wo#c244116.

Some newly introduced programmes are also excluded from the comparative data currently available for this report. Italy introduced experimental bachelor’s degrees with professional orientation in 2018. Designed to facilitate entry into the world of work, professionally-oriented degree courses must build on agreements with companies or professional associations, include an internship and ensure that 60% of graduates are employed within one year of graduation. Following the experimental stage, new professionally-oriented degree courses were introduced in 2020 in construction and the territory, agricultural, food and forestry technical professions, and industrial and ICT technical professions (OECD, 2021[25]).

Finally, in countries with ‘unified’ higher education systems, including many English-speaking countries, the kinds of programmes offered in universities of applied science are delivered in multi-purpose higher education institutions (universities or colleges). These are nearly always classified as having “unspecified orientation” in comparative data.

Master’s level qualifications – ISCED level 7

The availability of comparative data

Comparative data on professional programmes at level 7 are only available for 12 countries, and are based on national definitions of programme orientation (see Figure 1.6). Most other countries report all students under unspecified programme orientation and some consider all programmes at this level as academic. As for ISCED level 6, in the absence of internationally agreed definitions, different classification choices inevitably drive much of the variation in enrolment numbers. For example, in France, the high share of professional students at master’s level reflects how many programmes are classified as professional: engineering, business, law, accountability, education, medicine, pharmacy, odontology and midwifery. Most other countries treat such advanced programmes, including for medical professions and engineers, as academic or unspecified.

In summary, given comparative data limited to 12 countries, the lack of definitions to underpin comparability, and the lesser quantitative role of ISCED level 7 relative to levels 5 and 6, subsequent chapters of this report will exclude ISCED level 7.

Figure 1.6. Distribution of students by programme orientation at master’s or equivalent level (2018)

Note: Data are based on national definitions of programme orientation.

Source: OECD (2021[9]), “Education at a Glance”, Education and Training – Education at a Glance (database), https://stats.oecd.org/.

Common types of qualifications covered by comparative data

Professional master’s and advanced specialisation programmes

Professional master’s degrees exist in the Netherlands (see Box 1.9), where they are offered in universities of applied science. They cover a wide range of fields and offer a higher learning opportunity to graduates of professional bachelor’s programmes. Other advanced specialisation programmes reported as professional typically take one or two years to complete. These include programmes in the field of healthcare, such as medical or dental graduate specialisation programmes in Chile, medical residency in Lithuania, professional training for general practitioners in Luxembourg and post-degree specialist health studies in Spain. Some teacher training programmes are included in this category in France, Israel and Luxembourg. In Luxembourg programmes preparing for an examination for chartered accountants or chartered auditors is included.

Box 1.9. Professional master’s degrees in the Netherlands

Programmes are available in a wide range of fields, such as education (e.g. qualifications for teachers or school leaders), economy and business (e.g. MBA, customer management, finance and control), healthcare (e.g. advanced nursing, medical imaging), art and culture (e.g. interior architecture, music). Programmes differ from university master’s degrees in that they have a stronger professional orientation and less emphasis on research and analytical skills. Professional master’s programmes offer an upskilling option for graduates of professional bachelor’s programmes, as direct access is possible (while master’s degrees offered at universities are only accessible to them after a bridging course).

Source: StudieKeuze123.nl (2022[39]), Objectieve informatie over alle erkende hbo- en wo-opleidingen van Nederland [Objective information about all recognised university and university of applied sciences programmes in the Netherlands], https://www.studiekeuze123.nl/.

Professional examinations

A few countries have professional examinations at ISCED level 7 (see Box 1.5 on professional examinations in general and Box 1.10 for specific examples). In Switzerland, this qualification is wellestablished offering advanced specialisation to professionals who have acquired a great deal of expertise in their field and/or who intend to hold a managerial position in a company. In Germany the title “Master Professional” was introduced in 2020 to refer to advanced professional qualifications. In Luxembourg, programmes with similar features are run by universities. For example, programmes preparing for the examination for chartered accountants or chartered auditors in Luxembourg is taught in two semesters, combined with work-based learning.

Box 1.10. Examples of professional examinations at ISCED level 7

Financial analyst and wealth manager - Switzerland

Financial analysts and wealth managers study companies that are typically listed on the stock exchange. They assess the financial instruments issues by companies (e.g. stocks, bonds) and develop investment strategies and manage portfolios, based on careful consideration of the interests of the clients and those of the institution. Financial analysts focus mostly on providing information and advice, while wealth managers focus on investments.

Candidates must hold a vocational or general upper secondary school certificate plus at least five years of experience in banking or finance (or higher level studies with fewer years of experience, e.g. a bachelor’s degree or federal diploma of higher education plus three years of relevant experience). The examination consists of three modules: Financial accounting and analysis, equity, corporate finance and economics; Fixed income, derivatives and portfolio management; the Swiss market, ethics, law and taxation.

Technical management – Germany

The programme is delivered online through seminars and webinars and takes about 12 months to complete part time, while participants are employed (classes take place in the evening with live webinars every week). The full-time version of the course takes 11 weeks to complete. Targeted preparation for the examination is offered to both part-time and full-time students. The examination is conducted by local industrial and commercial chamber. The written part of the examination is common across all chambers in Germany.

Chartered accountants – Luxembourg

The University of Luxembourg offers a two-semester programme preparing for examinations for chartered accountants. Courses are taught in 3-4 hour blocks, three days a week. Candidates will be considered for the examination only if they are pursuing an internship approved by relevant financial control authorities or with a chartered accountant.

Source: manQ e.K. (2022[40]), Master Professional - Technischer Betriebswirt (IHK) [Master Professional – Technical Business Administration (IHK)], https://www.management-qualifizierung.de/kursangebote/betriebswirte/technischer-betriebswirt-ihk; SDBB (2022[28]), Das offizielle schweizerische Informationsportal der Berufs-, Studien- und Laufbahnberatung (Le portail officiel suisse d’information de l’orientation professionnelle, universitaire et de carrière), https://www.berufsberatung.ch/; Université de Luxembourg (2022[41]), Formation complémentaire des candidats réviseurs d'entreprises et experts-comptables, https://wwwfr.uni.lu/formations/fdef/formation_complementaire_des_candidats_reviseurs_d_entreprises_et_experts_comptables.

Long first degrees

Some programmes reported by countries in this category are “long first degrees”, which require at least five years to compete, may be started directly after upper secondary education and lead to a qualification that is equivalent to a master’s degree. These are often five or six year programmes in medical fields, law or engineering. For example, France applies a broad definition of “professional” and includes five-year business schools and long first degree programmes in law, medicine, pharmacy and odontology in this category. The Czech Republic reports career-oriented master’s study programmes, which take five or six years to complete.

Comparative data capture a small part of programmes at this level

Programmes at ISCED level 7 that are similar to those described above as professional are classified as academic or unspecified in most OECD countries and are excluded from comparative data on professional programmes. For example, as shown in Figure 1.3, training for lawyers and medical doctors is treated as professional by only two out of 26 countries, while over 20 countries include these programmes in the category of academic or unspecified orientation. Similarly, advanced specialisation courses are treated as academic or unspecified by many countries – for example half of the countries that responded to our survey report training for accountants as having academic or unspecified orientation.

In addition, qualifications akin to advanced professional examinations in some countries are delivered outside the formal education and training system, and are therefore not covered by comparative data collections based on ISCED mappings. Box 1.11 describes the example of training for patent attorneys in the United Kingdom, which builds on an undergraduate qualification but only sometimes includes an element of formal education (the Foundation Certificate course).

Box 1.11. Training for patent attorneys in the United Kingdom

Patent attorneys assess whether inventions are new and innovative, and therefore eligible to be patented. They are typically employed by law firms, the law department of large industrial companies or government departments. It usually takes four to six years to qualify as a patent attorney. Candidates need a degree in a science, engineering, technical or mathematics-based subject. Training takes place on the job and includes self-directed study, in-house support and guidance, as well as external training courses. At foundation level, candidates must complete either an accredited Foundation Certificate examination or pursue an accredited Foundation Certificate course provided by a university. The subsequent final diploma examination tests candidates’ knowledge of intellectual property law, skills in drafting and amending patent applications, and capacity to assess a patent’s validity. In addition, candidates must undertake two years’ of supervised full-time practice or at least four years of unsupervised full-time practice in intellectual property. Successful candidates become chartered patent attorneys.

Source: Prospects.ac.uk (2022[42]), Job profile - Patent attorney, https://www.prospects.ac.uk/job-profiles/patent-attorney.

The landscape of provider institutions

Table 1.4 provides an overview of the types of institutions that deliver short-cycle tertiary programmes (regardless of how their orientation is classified) and bachelor’s programmes, distinguishing between academic and professional programmes in countries that choose to draw a distinction.

Several countries deliver short-cycle programmes in dedicated institutions, which do not provide programmes above ISCED 5. These are either specialised technical institutions (e.g. vocational colleges in Norway, colleges in Poland) or educational institutions that also deliver upper secondary programmes (e.g. technical and vocational colleges in Austria, vocational secondary schools in the Slovak Republic and vocational colleges in Slovenia). In some countries certain types of institutions can deliver only ISCED 5 qualifications, while other types of institutions may deliver programmes at ISCED level 5 and ISCED 6 (and above). For example, in Latvia colleges may offer only short-cycle tertiary education, while other higher education institutions may offer tertiary programmes at all levels.

Multi-level institutions with an applied, professional focus are common in Europe. These include universities of applied sciences, university colleges and colleges, which are distinct from regular universities. Such institutions have the common characteristic that they undertake research in applied fields and train students for various professions or sectors. However, programmes delivered in such institutions are classified differently in comparative data collections. For example, Belgium (Flanders), Denmark and Lithuania treat programmes taught in these institutions as professional in international data collections, while Germany, Norway and Switzerland consider them academic and Austria, Finland and the Netherlands report all programmes at ISCED level 6 and above under “unspecified orientation”.

In some countries the kind of applied science programmes found in UAS-s or university colleges are found in ordinary universities. A recent European study (CEDEFOP, 2019[43]) identifies this approach as a ‘unified’ system, and in Europe, considers only Iceland and Spain, alongside the United Kingdom, in having such systems. England (UK) established polytechnic institutions in the 1970s with many of the same characteristics as the UAS-s, but subsequently merged polytechnics back into the university system from 1992 (Field, 2018[44]). Other countries maintain separate more professionally oriented systems of further and higher education, including TAFE institutions in Australia, and community colleges in the United States and Canada, but these systems much less often offer bachelor’s degrees at ISCED level 6, and instead offer a diverse area of programmes, including two year programmes at ISCED level 5 that are intended to articulate into bachelor’s programmes in universities, so they are not really comparable with UAS-s. In many English-speaking countries multi-purpose universities provide a full range of programmes at bachelor’s level, including programmes that might be classified as general, sector- or profession-oriented.

Finally, the institutions delivering preparatory courses for professional examinations are subject to little regulation and include a wide range of providers (see Box 1.12).

Box 1.12. Preparatory courses for professional examinations in Switzerland

There is a great variety of institutions that provide preparatory courses for federal examinations. They include providers run by local authorities, professional organisations, individual or groups of companies. Some are private education providers, while some have a mixed public-private ownership. The preparatory courses themselves are not regulated, as they are optional. A major recent reform was the introduction of subsidies in 2018, which cover 50% of the tuition cost of preparatory courses. This reform aimed to put adults preparing for federal examinations on equal footing with students in PET colleges, UAS-s and academic universities, signalling that higher VET has equal value to university studies. Prior to the reform the only support available for those preparing for federal examinations was a contribution from their employer.

Source: OECD Data collection on professional tertiary education.

Table 1.4. Type of institutions delivering tertiary programmes

ISCED 5 and 6 programmes by level of education and orientation

|

|

Short-cycle tertiary |

Bachelor |

|

|---|---|---|---|

|

Academic |

Professional |

||

|

(1) |

(2) |

(3) |

|

|

OECD |

|

|

|

|

Australia |

Some secondary education providers, vocational education providers, some universities. |

Universities. |

Universities and some vocational education providers. |

|

Austria |

Higher technical and vocational colleges, post-secondary colleges, technical and vocational schools, universities, other HEI-s |

Universities, universities of applied sciences, university colleges of teacher education |

n.a. |

|

Belgium (Flanders) |

Secondary education schools and university colleges |

Universities |

University colleges |

|

Belgium (French Community) |

Adult higher education |

Universities, university colleges (high schools), adult higher education and higher arts schools |

Universities, university colleges (high schools), adult higher education and higher arts schools |

|

Canada |

Colleges |

Universities, colleges |

|

|

Chile |

Technical training centres, professional institutes |

Universities, professional institutes |

Universities, professional institutes |

|

Colombia |

Universities, university institutions, professional technical institutions, technological institutions |

Universities, university institutions |

n.a. |

|

Costa Rica |

Universities, university institutions, professional technical institutions, technological institutions |

Universities |

|

|

Czech Republic |

Conservatoires |

University and non-university HEI-s |

University and non-university HEI-s, tertiary professional schools |

|

Denmark |

University colleges, business academies |

Universities |

Universities, university colleges, business academies, others |

|

Estonia |

m |

Universities, professional HEI-s |

|

|

Finland |

m |

Universities, universities of applied science |

|

|

France |

Universities, high schools, other institutions |

Universities, high schools |

Universities, private universities, specialised schools (e.g. Business, nursing, accountability) |

|

Germany |

Independent private training institutes, trade and technical schools |

Universities, universities of applied science, cooperative state universities, colleges of public administration, vocational academies |

Fachgymnasium, independent private training institutes, specialised vocational school, trade and technical school, vocational academies |

|

Hungary |

Universities |

Universities, colleges |

|

|

Israel |

Colleges |

Universities, colleges |

Universities, colleges |

|

Italy |

Higher level technical education institutions |

Universities, specialised HEI-s (fine arts, drama, arts, music) |

|

|

Japan |

Colleges of technology, junior colleges, specialised training colleges |

Universities, colleges, colleges of technology, junior colleges, educational institutions other than universities that are recognized by NIAD-QE |

|

|

Korea |

Colleges |

Universities, colleges |

Universities, colleges |

|

Latvia |

Universities, university colleges, colleges |

Universities, university colleges |

Universities, university colleges |

|

Lithuania |

n.a. |

Universities |

Colleges (small share in universities) |

|

Luxembourg |

Secondary schools |

Universities |

Universities |

|

Mexico |

Technological universities, technological institutes |

Universities, university colleges |

n.a. |

|

Netherlands |

Universities of applied science (HBO) |

Universities |

Universities of applied science (HBO) |

|

New Zealand |

All HEI-s |

All HEI-s |

|

|

Norway |

Vocational colleges |

Universities, university colleges |

n.a. |

|

Poland |

Colleges |

Universities, academies, non-university HEI-s |