This chapter explores how 15-year-old students’ school environment, and the opportunities they have to engage in creative activities with their teachers or at home, may influence their creative thinking proficiency. The chapter first compares school principals’ and teachers’ beliefs about creativity with those of their students. Then, it analyses the use of certain pedagogies in the classroom and student participation in different activities at school, examining how they relate to creative thinking proficiency in different types of tasks. Finally, the chapter looks at students’ broader environment, and in particular through the lens of digitalisation, assessing the relationship between digital tools and creative thinking performance.

PISA 2022 Results (Volume III)

6. School environment and creative thinking

Abstract

For Australia*, Canada*, Denmark*, Hong Kong (China)*, Ireland*, Jamaica*, Latvia*, the Netherlands*, New Zealand*, Panama*, and the United Kingdom* caution is advised when interpreting estimates because one or more PISA sampling standards were not met (see Reader’s Guide, Annexes A2 and A4).

For Albania** and the Dominican Republic**, caution is required when comparing estimates with other countries/economies as a strong linkage to the international PISA creative thinking scale could not be established (see Reader's Guide and Annex A4).

“A creative life is an amplified life. It's a bigger life, a happier life, an expanded life.”

Elizabeth Gilbert

Classroom and school environments, and broader educational approaches, are important factors that can shape creative thinking in education (OECD, 2023[1]). But can school really kill creativity? Are we all born creative and then educated out of it? This has been the concern of many researchers (Sarson, 1990[2]; Sharan and Tan, 2008[3]; Sternberg, 2007[4]; Robinson and Aronica, 2009[5]). It is also a concern for students themselves, as reported by a recent OECD study on social-emotional skills finding that 15-year-old students felt less creative than 10-year-olds did (OECD, 2024[6]). Yet, nurturing a classroom climate conducive to creativity, cultivating positive beliefs and attitudes towards creative thinking amongst educators, and increasing opportunities and rewards for students to express their ideas and produce creative work can all contribute to supporting the development of creative thinkers. This chapter analyses how student performance in creative thinking relates to different aspects of students’ school and social environments. It examines school principals’, teachers’ and parents’ beliefs and attitudes towards creativity and compares these with students’ own beliefs and attitudes. It also casts light on the extent to which students are exposed to certain pedagogies and activities, both inside and outside of school, and how these practices may support creative thinking.

What the data tell us

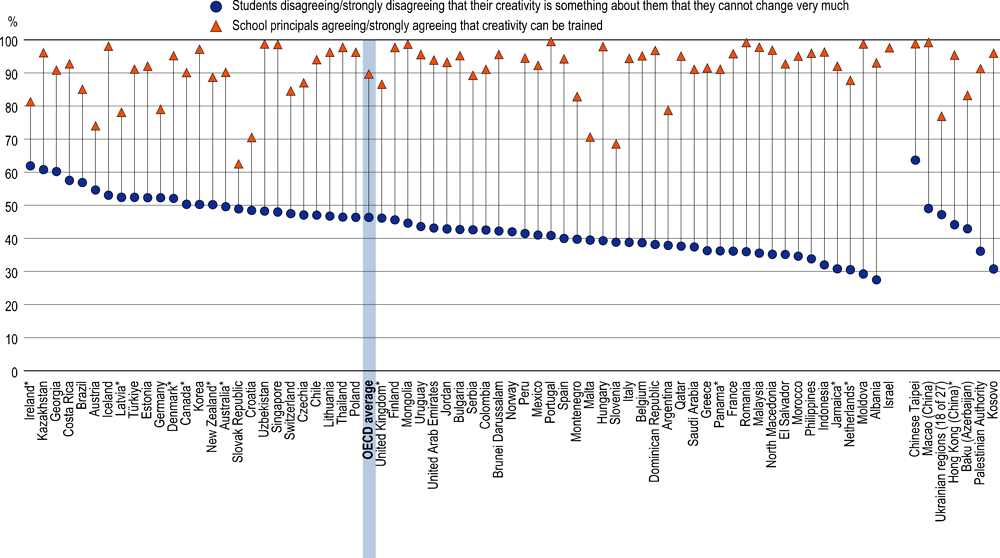

On average across OECD countries, about 90% of 15-year-old students are in schools whose principal believes that creativity can be trained, or that it is possible to be creative in nearly any subject. This is about twice as much as the share of students who think they can do something about their own creativity. Though educators’ openness helps nurture a positive school climate around creativity, PISA 2022 data suggest that it takes more than positive beliefs from school staff to really support students’ creative thinking.

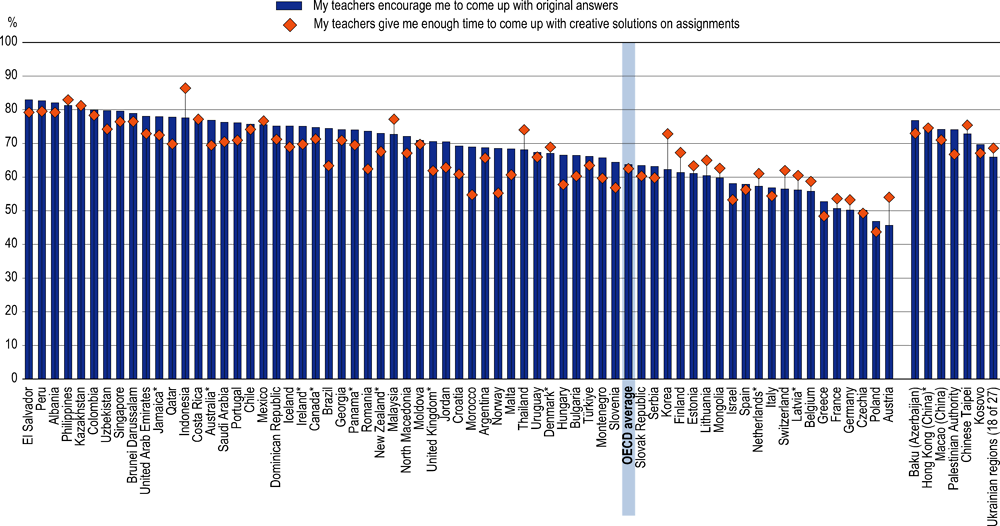

Certain classroom pedagogies are related to students’ proficiency in creative thinking. On average across OECD countries, between 60 and 70% of students reported that their teachers value their creativity, that they encourage them to come up with original answers, and that they are given a chance to express their ideas in school – with relatively higher shares in Latin American countries, and lower shares in European countries. Students who experience more of these pedagogies tended to demonstrate slightly stronger creative thinking proficiency than their peers, especially when asked to evaluate and improve ideas in the context of scientific problem solving.

Students who take part in art, music, or creative writing activities/classes on a weekly basis at school, scored only modestly better than their peers. They do, however, demonstrate relatively stronger creative thinking in the domain of visual expression and in the most difficult questions of the assessment overall; and they reported higher levels of openness to intellect and creative-self efficacy, two attitudes conducive to creative thinking. Both more frequent (every day) and more irregular (once or twice every semester) attendance in these activities is negatively related to performance, though (self-)selection plays a role here.

Digitalisation has transformed the social environment of 15-year-old students, inside and outside of school. Using digital tools for learning purposes for more than one hour a day only modestly relates with students creative thinking performance, as it did with mathematics (+0.8 points outside of school, +0.2 points at school). Spending the same amount of time on digital tools for leisure purposes, however, plays out very differently on students’ creative thinking performance: positively when this time is spent outside of school (about 3 points), but – unsurprisingly – negatively if spent at school (-0.8 points).

Figure III 6.1. PISA 2022 coverage of aspects of the educational environment related to creative thinking

Notes: This chapter covers items from the following PISA 2022 background questionnaires: students, school principals, teachers and ICT. See Annex A6 for more information on the data origin of the indices and constructs presented above.

The * indicates that the results on schools' assessment practices, and their association with creative thinking performance, can be found in the annex chapter (Table III.B1.5).

School climate and creativity

Do educators believe creativity and creative thinking are important? Do school principals feel that their school and school staff provide spaces for creativity, and do these beliefs match how students feel about their school environment? This section examines openness towards creativity in school and how a favourable school climate relates to student performance in creative thinking.

School leaders’ beliefs about the nature of creativity

Across participating countries and economies, school principals generally hold favourable beliefs about the nature of creativity and its potential to be developed through practice. On average across OECD countries, almost all students are in a school whose principal agreed or strongly agreed that there are many different ways to be creative (98%) or that it is possible to be creative in nearly any subject (89%) (Table III.B1.6.55).

The vast majority of students also attend a school whose principal reported that creativity is a skill that can be trained (90% on average across OECD countries) (Figure III.6.2). Only in the Slovak Republic, Slovenia, Croatia, Austria and Malta do less than three out of four students have school principals who disagreed with the notion that creativity can be trained. On average across OECD countries, school principals’ beliefs about the nature of creativity were similarly favourable across advantaged and disadvantaged, public and private, and general and vocational schools (Table III.B1.6.56). Though this general lack of variation is driven by the very favourable beliefs of nearly all school principals, there are a few countries where large discrepancies between schools exist. In Montenegro, Malta, Georgia, North Macedonia, Albania**, Serbia and Latvia*, principals of socio-economically advantaged schools were much more likely to report that creativity can be trained and/or that it can be expressed in nearly any subject than their peers (more than 15-percentage points difference with their colleagues in disadvantaged schools); while it was the opposite in Croatia.

Given the largely favourable views of school principals across most countries and economies, what school leaders believe about creativity was rarely associated with differences in student performance. Additionally, their beliefs were not necessarily matched by students. For instance, the share of students who attend a school whose principal believes creativity can be trained was about twice the proportion of students who think their creativity is something about them that they can change very much (47% on average across OECD countries, Figure III.6.2) – in other words, who hold a growth mindset towards creativity. The largest gaps between principals’ and students’ beliefs were observed in European countries – particularly Moldova, Albania** and Kosovo (in descending order) – but that is also the region where principals’ and students’ beliefs were most aligned, as observed in the Slovak Republic, Ireland*, Austria and Croatia. While it may be easier (and more socially desirable) for school principals to believe that creativity can be trained, in general, than it is for students to believe their own creativity can be improved, the gap between what learners and those in charge of their learning think is important – especially as PISA 2022 results show that students with a growth mindset towards creativity outscored their peers with fixed mindsets, after accounting for students’ and schools’ characteristics (see Chapter 5). Therefore, a first step towards nurturing school environments that are conducive to creative thinking may be for educators to more actively transmit their favourable beliefs about the nature and malleability of creativity to their students.

Figure III 6.2. Students’ and school principals’ growth mindset on creativity

Percentage of students who disagree/strongly disagree that "Your creativity is something about you that you cannot change very much"; percentage of students in schools whose principal agree/strongly agree that "Creativity can be trained"

Notes: Only countries and economies with available data are shown.

Countries and economies are ranked in descending order of the percentage of students holding a growth mindset on creativity.

Source: OECD, PISA 2022 Database, Tables III.B1.5.4 and III.B1.6.55. The StatLink URL of this figure is available at the end of the chapter.

School openness to creativity

School principals mostly believe that students in their school are open to creativity, an index that captures their perceptions of students’ openness to learn and to engage in creative work. On average across OECD countries, around 75% of students’ principals agreed or strongly agreed that most of their students are creative, imaginative and enjoy doing creative projects (Table III.B1.6.59). However, less than half reported that most of their students are artistic, suggesting that many perceive artistic skills to be somewhat separate to broader creative or imaginative skills. Most school leaders also reported that students enjoy learning new things (89% on average across OECD countries) – which is generally aligned with students when asked the same question. While nearly three-quarters (72%) of students had school principals who reported that most students at their school enjoy work that is challenging. This appears to be a large over-estimation as less than half (47%) of all students across OECD countries reported that they like schoolwork that is challenging (Tables III.B1.6.59 and III.B1.5.11).

The index of school openness to creativity is subject to greater disparities between different types of schools than the index of school principals’ beliefs about creativity. On average across OECD countries, principals in charge of socio-economically advantaged schools, private schools, and general education schools tended to report higher levels of openness to creativity from their students (Table III.B1.6.60). The socio-economic gap is important, particularly in Asian countries and economies such as Brunei Darussalam, Malaysia, Hong Kong (China)*, Macao (China), Singapore, but also in Israel, Bulgaria, Romania, Jamaica* and Hungary.

What school principals think of their students’ openness to learn and to engage in creative work is moderately associated with students’ creative thinking proficiency. A one-unit increase in the index, as reported by school principals, was associated with a 0.3 score-point increase in students’ creative thinking proficiency on average across OECD countries (after accounting for students’ and schools’ characteristics) (Table III.B1.6.62).

Box III 6.1. Teachers’ beliefs about creativity and their openness to creative thinking

Results from the PISA 2022 Teacher Questionnaire

Across 17 countries and economies with available data, teachers of 15-year-old students largely held similarly positive beliefs about creativity as school leaders. On average across OECD countries, around 9 in 10 teachers agreed or strongly agreed that creativity can be trained, that people can be creative if they keep trying, and that it is possible to be creative in nearly any subject. Nearly all (98%) believed that there are many different ways to be creative (Table III.B1.6.74). Male and female teachers shared similarly positive beliefs, as did teachers in schools with large or small shares of students from socio-economically disadvantaged homes (Table III.B1.6.75).

Teachers are also confident about their own openness to intellect, with large majorities having reported that they enjoy learning new things (82% on average across OECD countries), that they have a good imagination (80%), or that they are very creative (77%) (Table III.B1.6.76). Women were much more likely to say they enjoy artistic activities (a difference of 11 percentage points) or that they express themselves through art (6 percentage points), while men were more likely to report that they enjoy solving complex problems (6 percentage points) and that they have a good imagination (5 percentage points). The socio-economic composition of their school, however, is not a strong marker of difference (Tables III.B1.6.77 and III.B1.6.78).

Nearly all teachers reported that they attach great importance to developing their students’ creativity. On average across OECD countries, more than 9 teachers out of 10 reported valuing students who have many new ideas, and that it is important for students to solve science problems creatively or to produce creative drawings and paintings (Table III.B1.6.79). Teachers in Latin American countries, including the Dominican Republic**, Panama*, Colombia and Costa Rica, reported a particularly strong importance attached to developing their students’ creativity.

System-level initiatives to develop teachers’ understanding of creativity and their creative self-efficacy

To support the development of creative thinking at school, jurisdictions need to support teachers in their understanding of creativity and in the confidence that they place in their ability to be creative and teach creatively. Research has shown that teachers’ creative self-efficacy, encompassing both perceptions about their ability to teach creatively and to facilitate creativity in learners, can give teachers a sense of agency and control for enacting creativity-fostering practices in the classroom (Rubenstein et al., 2018[7]). Teachers’ creative self-efficacy is also correlated with their perceptions of the value that society places on creativity, of the potential of students to become creative, and of their own creativity (Rubenstein, McCoach and Siegle, 2013[8]). Amongst countries where teachers attached great importance to developing their students’ creativity, it is a practice encouraged through in-service training (i.e. professional development activities) in Panama and Colombia, while in the Dominican Republic it features in initial teacher training (OECD, 2023[1]).

Source: OECD, PISA 2022 Database, Annex B1, Chapter 6.

Pedagogies, activities and school policies conducive to creative thinking

While a school climate that is perceived as broadly open to creativity by both students and educators is a good start, it is not enough for students to develop stronger creative thinking skills. Different educational approaches and practices may encourage or discourage students’ creative expression and achievement, for example the use of classroom pedagogies encouraging creative thinking and the availability of and participation in activities related to creativity. For example, students might have more opportunities to develop their creative thinking in schools where teachers encourage them to come up with and express their own ideas, or when they are offered activities that encourage them to produce creative outputs.

Pedagogies encouraging creative thinking

Teaching practices that perpetuate the idea that there is only one way to learn or solve problems, that cultivate attitudes of fear of authority, or that discourage students’ curiosity and inquisitiveness can stifle creative thinking (Nickerson, 2010[9]). Research suggests that teaching practices involving group work, finding ideas through brainstorming, playing educational games, debating ideas or current issues, giving students time to explore topics on their own, journaling, and incorporating creative activities like drawing or poetry into projects, offer opportunities to demonstrate and improve creative thinking (see Box III.6.4 on teachers’ use of creative pedagogies, which are one element of a broader set of both traditional and innovative pedagogies that can encourage creative thinking). However, teachers need to be supported with relevant training, resources and guidance to use such pedagogies and to encourage students’ creative thinking (see Box III.6.2 for field-trialled design criteria, and Box III.6.5 for international system-level initiatives).

Box III 6.2. Fostering and assessing creativity and critical thinking: An international field trial of pedagogical rubrics, lesson plans and design criteria by the OECD

Building a shared understanding of what creativity means, nationally or internationally, is a first step towards nurturing a classroom and school climate conducive to creative thinking. However, while PISA 2022 results show that teachers, school principals and education policymakers largely consider creativity to be an important learning goal, it remains unclear to many what it means to develop it in a school setting. To make this goal more tangible, the OECD Centre for Educational Research and Innovation (CERI) worked with networks of schools and teachers in 11 countries to develop and trial a set of pedagogical resources that exemplify what it means to teach, learn and make progress in creativity (and critical thinking) in primary and secondary education. Through a portfolio of rubrics and examples of lesson plans, teachers in the field gave feedback, implemented the proposed teaching strategies, and documented their work.

These field-trialled lesson plans exemplify the kind of approaches and tasks that allow students to develop their creativity and critical thinking while acquiring content and procedural knowledge across different domains of the curriculum. Eight “design criteria”, also co-developed with teachers and experts, and refined throughout the project’s implementation, summarise what pedagogies should involve to align with the internationally agreed rubrics on creativity (and critical thinking):

create students’ need and interest to learn;

be challenging;

develop clear technical knowledge in one domain or more;

include the development of a product;

have students co-design part of the product/solution;

deal with problems that can be looked at from different perspectives;

leave room for the unexpected;

include space and time for students to reflect and to give and receive feedback.

Notes: All of the OECD-CERI “Fostering and assessing creativity and critical thinking” project’s outputs are publicly available as open education resources. Rubrics, lesson plans and design criteria can be downloaded here https://oe.cd/5z7. They can also be retrieved from the CERI CCT Mobile App: http://www.oecdcericct.com

Source: Vincent-Lancrin, S., et al. (2019), Fostering Students' Creativity and Critical Thinking: What it Means in School, https://doi.org/10.1787/62212c37-en.

Many students across OECD countries believe that their teachers broadly value their creativity (70% of students on average across OECD countries) and that school gives them a chance to express their ideas (69%) (Table III.B1.6.1) – both factors that contribute to creating a positive school climate for creativity, as described in the first section of this chapter. Most students also reported that their teachers employ more concrete practices that are conducive to encouraging creative thinking in the classroom. Notably, about two-thirds of students reported that their teachers encourage them to come up with original answers (63%) or creative solutions on assignments (64%) (Figure III.6.3). Only in Austria, Czechia, Greece and Poland did less than half of students report that their teachers encourage them to come up with original and/or creative solutions on assignments.

Figure III 6.3. Student-reported use of pedagogies encouraging creative thinking

Percentage of students who agree/strongly agree with the following statements

Note: Only countries and economies with available data are shown.

Countries and economies are ranked in descending order of the percentage of students reporting that their teachers encourage them to come up with original answers.

Source: OECD, PISA 2022 Database, Table III.B1.6.1. The StatLink URL of this figure is available at the end of the chapter.

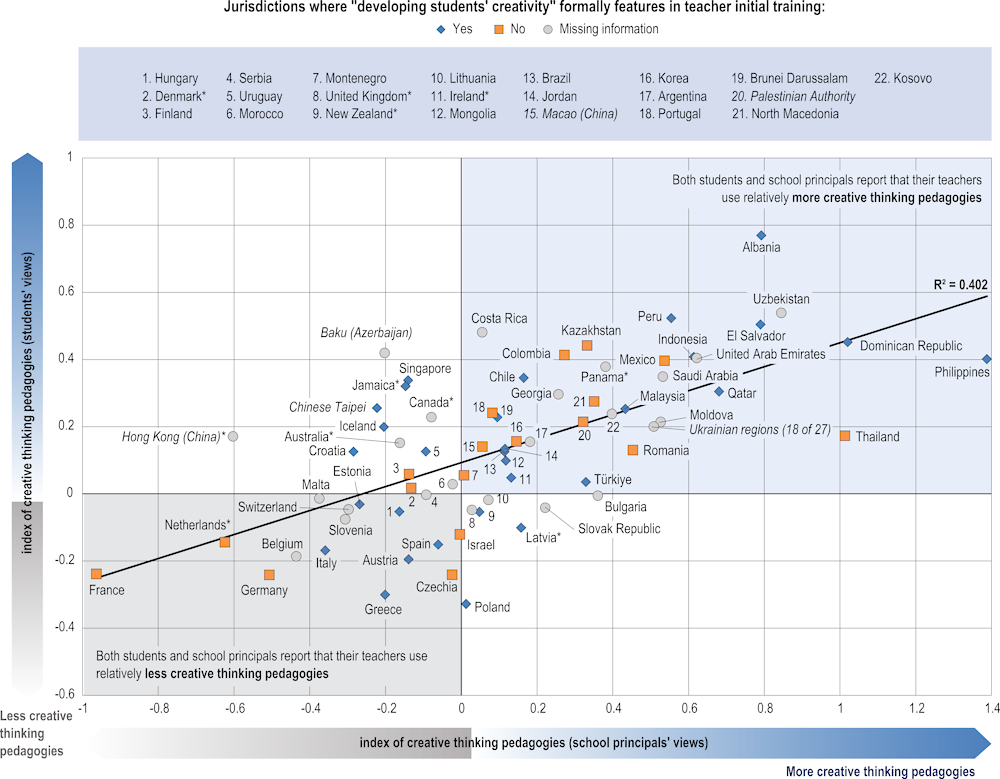

An index of pedagogies encouraging creative thinking combines students’ perceptions of their teachers’ practices with their broader school openness towards encouraging creative thinking. Many Latin American countries, such as Peru, El Salvador, Costa Rica, the Dominican Republic** and Colombia, are among the countries and economies with the highest index of student-reported creative thinking pedagogies – together with Albania**, Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan, Baku (Azerbaijan) and Indonesia, in descending order (Figure III.6.4, Y-axis). By contrast, the countries at the bottom end of this index exclusively consist of European countries, including Spain, Italy, Belgium, Austria, France, Czechia, Germany, Greece and Poland (also in descending order). Across many countries and economies at the upper end as much as at the lower end of the distribution, “developing students’ creativity” is formally integrated into initial teacher training (Figure III.6.4, green markers) (OECD, 2023[1]). PISA results suggest that this is not sufficient for students to perceive more attempts from their teachers to encourage creative thinking.

Figure III 6.4. Students’ and school principals’ views on their teachers’ use of pedagogies encouraging creative thinking

Note: Only countries and economies with available data are shown.

Sources: OECD, PISA 2022 Database, Tables III.B1.6.1 and III.B1.6.67; and OECD, PISA 2022 System-Level Questionnaire on Creative Thinking.

The StatLink URL of this figure is available at the end of the chapter.

On average across OECD countries, socio-economically advantaged students reported that their teachers employ pedagogies encouraging creative thinking more than their disadvantaged peers; but students in socio-economically advantaged schools reported the use of these pedagogies less frequently than their peers in disadvantaged schools (Table III.B1.6.3). This may suggest that students in advantaged schools expect their teachers and broader school environment to encourage and value creative thinking more than they do, thus leading students in advantaged schools to underreport their frequency; or that advantaged schools and their teachers indeed leave less room for student creativity in school assignments, perhaps to the benefit of more traditional pedagogical practices and tasks.

Students in general educational track schools reported fewer pedagogies encouraging creative thinking than students in vocational and prevocational schools (Table III.B1.6.3). This finding may point to differences in the ways that students are taught and assessed in vocational schools, which may also be linked to inherent differences in the kinds of subjects studied by students in vocational schools (Box III.6.3).

Box III 6.3. Pedagogies encouraging creative thinking in vocational and pre-vocational schools

In several countries and economies participating in PISA 2022, a share of 15-year-old students might have already been enrolled in vocational or pre-vocational schools at the time of the assessment. These schools have long emphasised the teaching and practicing of technical skills that meet the specific needs of the sectors and industries that they aim to prepare students for. In addition to technical skills, other “soft skills”, such as self-discipline, reliability, critical thinking and, of course, creativity, are in demand everywhere in the labour market and in wider society, and thus feature highly in the skillset expected from future-ready vocational and training systems (OECD, 2023[10]).

Hands-on training, a hallmark of vocational education and training (VET), is an active and inductive professional learning method where individuals gain knowledge and skills through direct experience and practice, which often requires them to tackle concrete challenges using their own skill set. Hands-on, active-learning environments typical of VET can be leveraged to enhance creative thinking skills. The concept of cognitive apprenticeship, which combines traditional apprenticeship’s hands-on approach with formal schooling’s problem-solving strategies, also thrives in VET settings. Studies suggest that it offers a promising model for developing creative thinking by making the thought processes behind tasks visible and encouraging reflection across different tasks (Collins, Brown and Newman, 1989[11]).

Another feature of some VET programmes is the importance given to the master-apprentice dynamic. A research experiment investigated the development process of “high-level creativity” in the practice of haute cuisine (Stierand, 2014[12]). High-level creativity is defined as “expert-level creativity that produces popular and respected output that, in some cases, will even be known and enjoyed by generations to come” (Kaufman and Beghetto, 2009[13]). Authors found that a master–apprentice relationship allows apprentices to practice their creative sensemaking in open-ended contexts (Agryris, 1982[14]; Cunliffe, 2002[15]; Tsoukas and Chia, 2002[16]) and to experience first-hand the bridging between practice and creativity (Chia, 2003[17]).

Finally, VET courses often involve project-based learning, as well as work-based and problem-based learning. Several studies have highlighted the assets of these learning models to enhance students’ creativity and problem-solving skills (Usmeldi and Amini, 2022[18]; Musset, 2019[19]), pointing to the potential for innovative VET pedagogical approaches to inspire pedagogies in other educational settings (Ulger, 2018[20]).

Across participating countries and economies, school principals and students tend to share the same views on their teachers’ use of pedagogies encouraging creative thinking in their school (Figure III.6.4, X-axis), Although school principals generally all held very favourable views on their teachers’ use of such pedagogies, European school principals appeared relatively more critical than their peers in Latin American countries, Albania**, Indonesia and Uzbekistan.

Unlike students’ reports, principals of socio-economically advantaged schools, as well as principals of general schools, reported a higher incidence of pedagogies encouraging creative thinking in their schools than their colleagues in disadvantaged and vocational schools, respectively (Table III.B1.6.68). One reason for this may be that principals of advantaged and general schools also reported that their schools offer various activities and classes to students more frequently than their peers in other types of schools (see the following section for further information), which may influence their perceptions on the use of pedagogies encouraging creative thinking in their schools.

Box III 6.4. Teacher-reported use of creative pedagogies

In all 17 countries and economies with available data, teachers of 15-year-old students reported that they attached importance to using creative pedagogies. Debating ideas or current issues, finding ideas though brainstorming, group work, and giving students time to explore topics on their own, are practices valued by more than 9 out of 10 teachers, on average across OECD countries (Table III.B1.6.82). Playing educational games, journaling, or incorporating creative activities like drawing or poetry into projects, are also important for a majority of teachers. The importance given to teaching practices has to be put into perspective of the autonomy given to teachers across systems: while 9 out of 10 teachers on average across OECD countries said they have a lot or full control over their teaching methods, only 7 out of 10 reported the same autonomy in determining course content (Table III.B1.6.85).

The use of creative pedagogies is more gendered than the beliefs teachers hold about creativity (Box III.6.1). On average across OECD countries, 76% of female teachers, compared to 64% of male teachers, reported that they attach importance to incorporating creative activities into projects (a difference of 12 percentage points). Playing educational games, journaling, finding ideas through brainstorming and group work are also pedagogies more likely to be valued by women educators than by men.

Similar to teacher-reported beliefs about the importance of developing students’ creativity, it is in Latin American countries that teachers reported that they attach relatively more importance to creative pedagogies: Dominican Republic**, Peru, Panama*, Colombia, Costa Rica (in descending order).

Pedagogies that encourage creative thinking and creative thinking performance

Does the use of pedagogies that encourage creative thinking make a difference to students’ creative thinking performance? After accounting for students’ and schools’ socio-economic characteristics and for their mathematics and reading performance, students who reported that their teachers encourage creative thinking in their classroom in general performed slightly better than those who did not (+0.2 points on average across OECD countries with a one-unit increase in this index). The two countries where this advantage is the greatest (Jamaica* and Malaysia) are countries where initial teacher training explicitly includes content focused on developing students’ creativity, teaching creatively and assessing creativity (OECD, 2023[1]). On average across OECD countries, this positive association was the strongest (though nonetheless modest) for students who believe their teachers value students’ creativity more broadly – these students scored 0.4 points higher than their peers who said their teachers do not value their creativity (Table III.B1.6.4). Other, more specific classroom practices are also positively, though marginally, associated with student performance in creative thinking (after accounting for students’ and schools’ characteristics and for their mathematics and reading performance): for example, students who reported that their teachers encourage them to come up with original answers or creative solutions on assignments scored 0.2 points higher, on average across OECD countries, then their peers; as did those students who think the activities they do in their classes help them think about new ways to solve problems (+0.3 points).

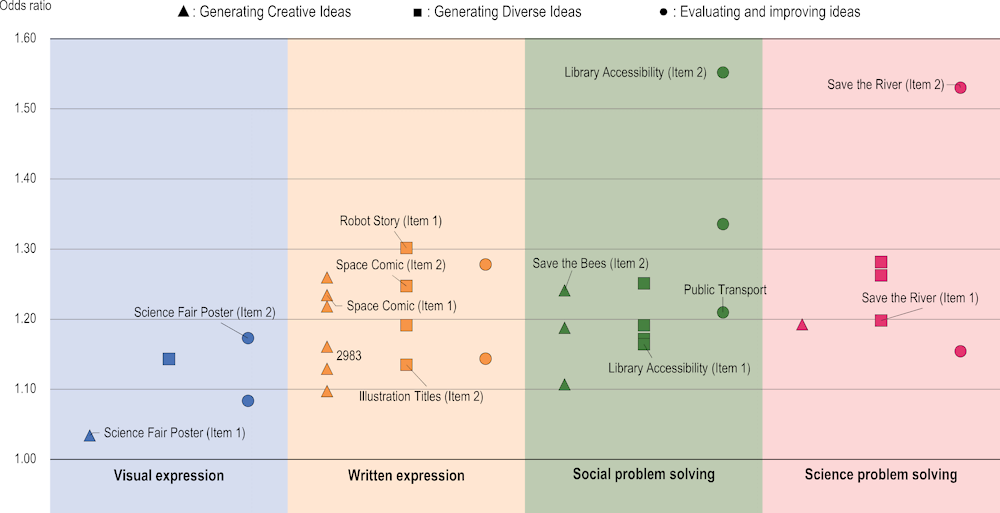

While these pedagogies were only modestly associated with a better creative thinking score overall, interesting patterns emerged when examining students’ performance across different types of tasks. For instance, students who reported that their teachers value students’ creativity were more likely to achieve full credit on items asking them to evaluate and improve others’ ideas (average odds ratio = 1.27) than generate diverse ideas (1.21) or creative ideas (1.17) (Figure III.6.5). In other words, students whose teachers value their creativity are 27% more likely to suggest original ways to improve others’ ideas than their peers and “only” 17% more likely to generate creative ideas. This aligns with research suggestions that evaluating the appropriateness of ideas is more easily amenable in an educational context than generating original ideas (Howard-Jones, 2002[21]). These students are also more likely to perform relatively better on items in scientific problem-solving contexts (1.27) than on those in the visual expression domain (1.11); and they are slightly more likely to achieve full credit than other students as the item difficulty increases.

The odds ratios are similar for students who reported that their teachers give them enough time to come up with creative solutions on assignments. In contrast, students who said they are given a chance to express their ideas at school did relatively better than others on items in the social problem-solving domain and that require generating diverse ideas.

Figure III 6.5. Pedagogies that encourage creative thinking, and creative thinking proficiency across assessment domains and facets

Likelihood (odds ratio) of getting full credit on the test items when students agree/strongly agree that “their teachers value students’ creativity”, by ideation processes and domain contexts; OECD average

Notes: Each marker corresponds to one of the 32 items in the PISA 2022 Creative Thinking Assessment. Shapes denote the three different facets and colours denote the four different domains. Labelled markers correspond to items that are publicly released (see Chapter 1).

Source: OECD, PISA 2022 Database, Table III.B1.6.5. The StatLink URL of this figure is available at the end of the chapter.

Box III.6.5. System-level policies or initiatives aiming to teaching for creative thinking

Provide dedicated resources for teachers to teach with and towards creativity…

Policymakers can support schools and teachers to reflect on and experiment with new practices in different ways. One type of system-level support includes providing training and teaching resources for educators to teach for creativity. In Scotland (United Kingdom), for instance, Education Scotland, a government agency, has provided teachers with a National Improvement Hub that includes learning resources, articles, impact reports, self-evaluation tools and exemplars of practice for improving teaching and learning, some of which relate to creativity and creative thinking.1 For instance, practitioners are given access to a “Creativity Toolbox” (2018), which contains 13 short films on creative approaches to support planning and improvement, and to a “Planning for and Evaluating Creativity” approach (2017), which contains several open access resources, such as the “Creative Learning Survey for Pupils”, the “Creative Teaching & Learning Graphic Equaliser”, and a “Creativity Evaluation Checklist” and “Creativity Planning Checklist”.2 The Creativity Portal, developed in partnership between Education Scotland and Creative Scotland, offers additional support in the form of “a one-stop shop to help teachers, community learning leaders, and educators find high quality creative partnerships, case studies of good practice, the latest creativity research, online teaching resources, and local creative learning contacts”.3 In England (United Kingdom), eight Creativity Collaboratives, clusters of 8–12 schools, were funded in 2021 to embed creative thinking in their curricula and beyond (Lucas, 2022[22]). The programme builds networks of schools to test innovative practices in teaching for creativity, sharing lessons learnt to facilitate system-wide change. Working alongside existing school structures, teachers and educators will co-develop creative strategy and pedagogy, test out approaches to teaching and learning, and evaluate their impact on pupils, schools and communities. Also in 2021, a new online platform, Creativity Exchange, was created as a space for school leaders, teachers, those working in cultural organisations, scientists, researchers and parents to share ideas about how to teach for creativity and develop young people’s creativity at school and beyond.

Other examples of support in the form of teaching guidelines and materials across PISA 2022 participating jurisdictions include the Moodle platform developed in North Macedonia in 2018, which comprises four courses on developing critical thinking, creative problem solving and programming skills.

… and materials for schools to offer creative learning environments

With a focus on resourcing learning environments, several jurisdictions also have funding schemes in place to facilitate appropriate materials, equipment and facilities for teachers and students to be able to work creatively. For instance, in Iceland, the government makes funding available for the establishment and maintenance of fabrication laboratories (“FabLabs”).4 These laboratories include different tools and devices to facilitate work on digital design and creation. Commonly located in upper-secondary schools, the Labs are typically open to the public. In China, schools in two districts of Shanghai – Jiading and Pudong – have developed a Creative Lab that draws inspiration from the five-dimensional model developed by the Centre for Real-World Learning in England.5 The project has involved schools identifying a specific theme with regional characteristics, for example, the automotive or maritime industries, constructing a curriculum, designing problem-based learning modules, mapping the five-dimensional model against the curriculum, encouraging students to generate creative solutions or products as the result of their learning, and developing rubrics to assess their progress.

Source: OECD (2023[1]) Supporting Students to Think Creatively: What Education Policy Can Do, retrieved from: https://issuu.com/oecd.publishing/docs/supporting_students_to_think_creatively_web_1; Lucas (2022[22]) Creative thinking in schools across the world: A snapshot of progress in 2022. London: Global Institute of Creative Thinking.

Availability of and participation in creative activities at school

In addition to teaching students core content and skills, like reading, mathematics and science, schools often provide opportunities for students to engage in activities or classes that aim to broaden their experiences and further their holistic development. These might include activities focusing on artistic or expressive endeavours (such as art and design, creative writing, music or theatre activities) that are typically associated with “creative” practices, or they might focus on games and competitions, physical education, community engagement or developing other specialised skills or interests.

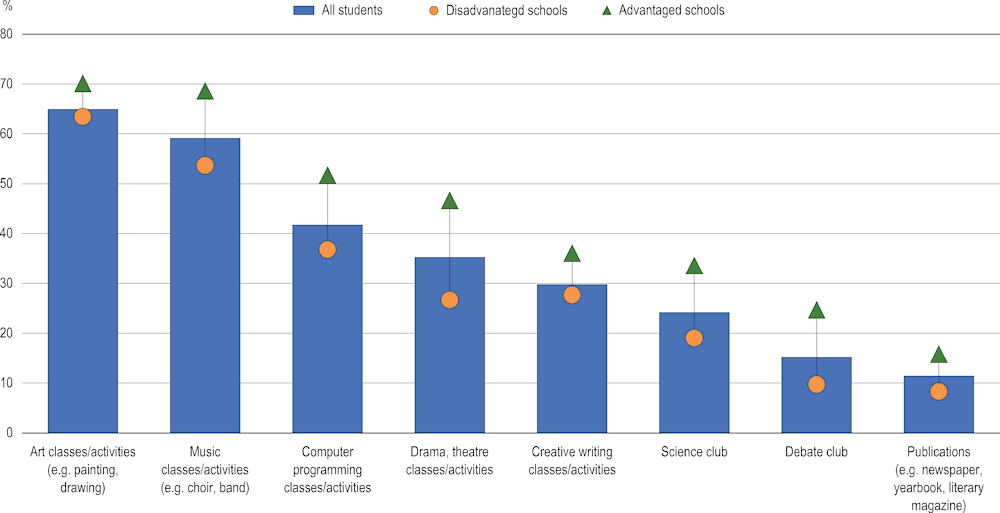

PISA 2022 asked school principals to report on the availability of and frequency with which different classes and activities are offered in their schools.6 On average across OECD countries, 65% of students reported having once a week or more access to art classes/activities, 59% to music classes/activities, 42% to computer programming classes, 35% to dramatics and theatre classes/activities, 31% to a science club, and 30% to creative writing classes (Figure III.6.6). Activities and classes that were much less frequently available, on average across OECD countries, include debate (15% of students were in schools that offer it at least once a week) and publications-related activities (11% of students on average). In Jamaica*, the United Kingdom*, Australia*, the United Arab Emirates and Macao (China), students have the greatest access to a range of different school activities (Table III.B1.6.65), according to school principals. By contrast, school principals in Greece, Norway, Belgium, Poland and Czechia reported that their schools offer relatively less activities to students compared to other countries.

Principals in socio-economically advantaged schools reported that their schools offer various classes and activities at least once a week to students more frequently than in disadvantaged schools. The largest disparity in weekly offer between advantaged and disadvantaged schools, on average across OECD countries and economies, was drama and theatre classes/activities (20 percentage points difference), as well as debate club, science club, computer programming classes/activities and music classes/activities (all 15 percentage points difference) (Table III.B1.6.66).

Figure III 6.6. Availability of activities at school, by school socio-economic profile

Percentage of students in schools whose principal reported that their school offers the following activities at least once a week; OECD average

Notes: Differences between advantaged and disadvantaged schools are all statistically significant (Annex A3). A socio-economically disadvantaged (advantaged) school is a school in the bottom (top) quarter of the PISA index of economic, social and cultural status (ESCS) amongst all schools in the relevant country/economy.

Items are ranked in descending order of the percentage of students in schools whose principal reported that their school offers the activities at least once a week.

Source: OECD, PISA 2022 Database, Tables Table III.B1.6.65 and Table III.B1.6.66. The StatLink URL of this figure is available at the end of the chapter.

Students were also asked about their participation in the same set of activities. Taking part in school-based activities might be mandated by teachers, schools or the curriculum in some countries and economies, while in other education systems and schools, this might be elective or even restricted to just a small number of students. Countries and economies with the greatest availability of different activities in schools are therefore not necessarily the same as those with the largest levels of student participation. In Albania**, Uzbekistan, Baku (Azerbaijan), the Dominican Republic** and the Palestinian Authority, students reported the highest frequency of participation in various activities at school (Table III.B1.6.6). Comparatively, in Czechia, Lithuania, Poland, Portugal and France, students reported taking part in these activities the least often in school. The highest discrepancies between participation in activities (students’ reports) and their availability at school (school principals’ reports) were seen in the United Kingdom*, with the school offering much higher than student participation.

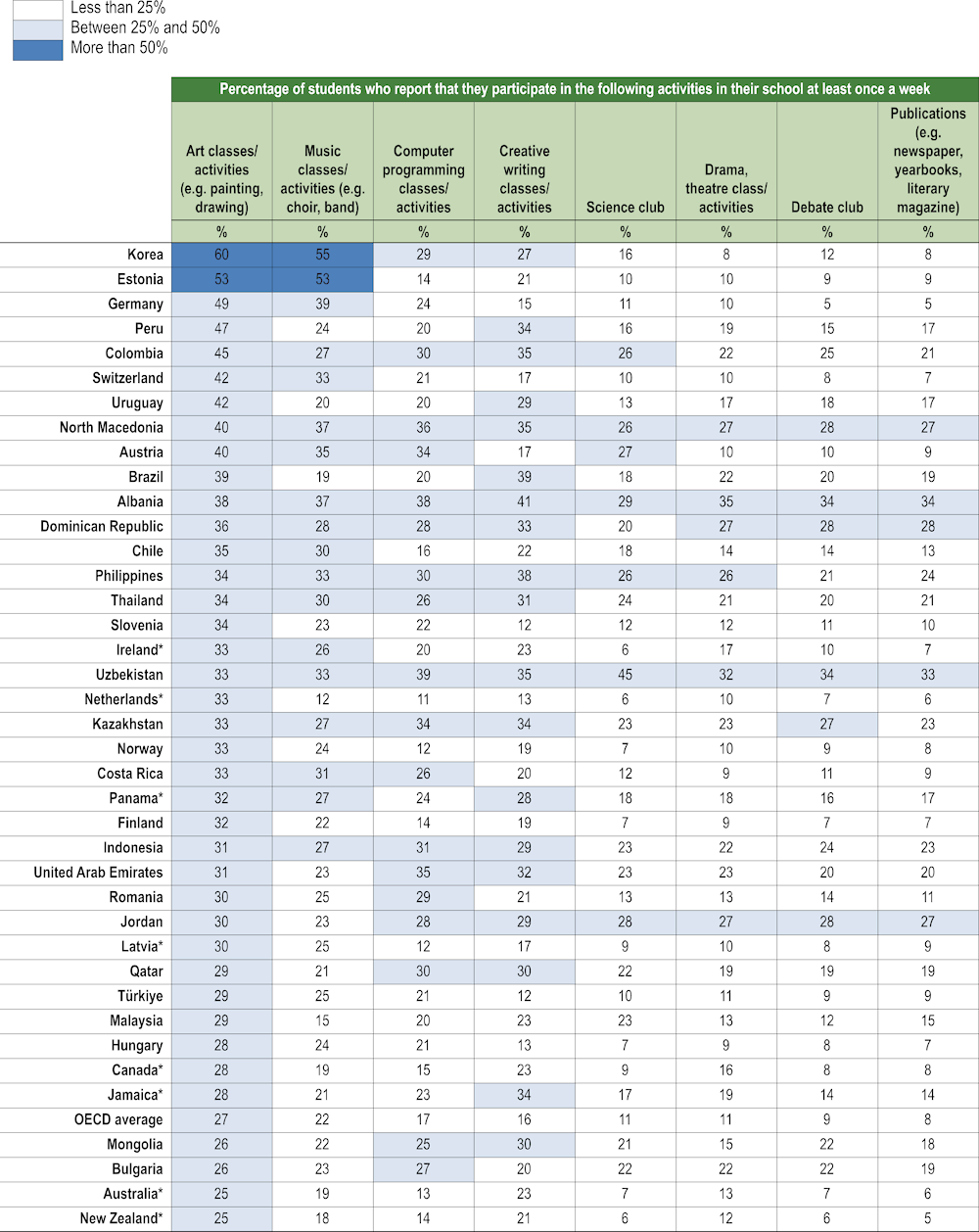

On average across OECD countries, students participate at least once a week in art classes/activities (27% of students), music classes/activities (22%), computer programming classes/activities (17%), creative writing classes/activities (16%) and drama and theatre classes/activities (11%) (Table III.6.1). These activities correspond to those that are offered most frequently by schools, according to school principals. This finding is logical: the more that activities are made available to students in school, especially when integrated into the curriculum, the more likely students are to participate in such activities. Broadening students’ skills and experiences at school fundamentally depends on the opportunities available to them.

Table III 6.1. Students’ participation in activities at school

Notes: Only countries and economies with available data are shown.

Countries and economies are ranked in descending order of the percentage of students reporting that they are participating in art classes/activities (e.g. painting, drawing) in their school at least once a week.

Source: OECD, PISA 2022 Database, Table III.B1.6.6. The StatLink URL of this table is available at the end of the chapter.

Boys participate in activities at school more frequently than girls, on average across OECD countries– although gender differences vary depending on the type of activity (Table III.B1.6.16). For example, girls participate significantly more often than boys in art classes/activities at least once a week (30% of girls compared to 24% of boys, on average across OECD countries), and there are no significant differences in the participation of boys and girls in music classes/activities at least once a week. The greatest gender differences in favour of boys are observed in science club (5 percentage points more boys) and computer programming activities (8 percentage points more boys), which reflect entrenched gender preferences and align with the current under-representation of girls in science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) disciplines.

One interesting finding is that, while advantaged schools appear to provide students with greater access to different activities at school, according to school principals, it is students in socio-economically disadvantaged schools who participate in activities more often than their advantaged peers, on average across OECD countries (Table III.B1.6.16). These patterns are also observed outside of school: in general, boys, socio-economically disadvantaged students, and students in disadvantaged schools, report more frequent participation in the same activities outside of school than their peers (Tables III.B1.6.20 and III.B1.6.21). The only exception to this trend across OECD countries is participation in music classes/activities, where advantaged students participate more often than disadvantaged students.

One reason for this counter-intuitive association between participation in different school-based activities and student background may be that students from more advantaged backgrounds, or who attend more advantaged schools, are more likely to focus their time and orient their educational choices towards traditionally “academic” subjects that have a greater influence on their ability to transition into tertiary education – and eventually, access high-paying jobs. These students may thus be less likely to choose to participate in such classes or activities regularly, especially as part of their formal studies. Students from more advantaged backgrounds may also have greater access to extra-curricular activities not asked about in PISA, such as private tutors or language classes, or more “elite” sports and clubs that are not typically offered at school.

Activities at school and relationship to creative thinking performance

In general, students who participate in many activities at school scored lower in creative thinking than those who do not, on average across OECD countries. However, this negative association may be explained by the characteristics of students who frequently participate in school-based activities. After accounting for students’ and schools’ characteristics, as well as students’ mathematics and reading performance, there is no strong association between participation in activities and creative thinking performance – except for in a handful of countries and economies, where it is either moderately negative (Denmark*, Kazakhstan, Malta, Chinese Taipei and Indonesia) or moderately positive (Chile and Iceland) (Table III.B1.6.17). Again, these findings imply that students from advantaged backgrounds, and/or those who are top performers in the core curricular domains, participate less frequently in school-based clubs and activities, perhaps to the benefit of concentrating on “core” school subjects.

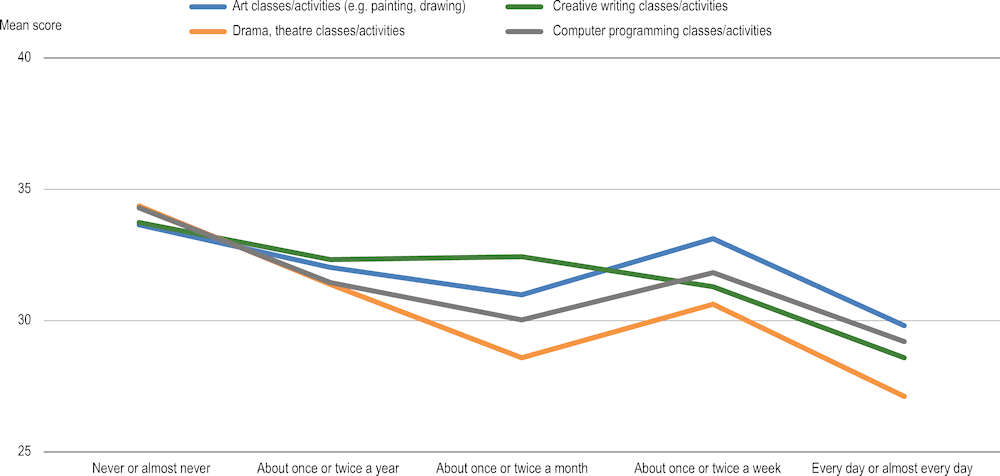

Nonetheless, some interesting patterns emerge when examining the average creative thinking performance of students who participate in school-based activities at different levels of engagement (Figure III.6.7). Amongst students who participate in various activities, those who take part in music, art, computer programming or drama classes/activities about once or twice a week scored better on average than both students who take part in those activities infrequently or on an ad-hoc basis (e.g. once a month or once or twice a year) as well as students who do so very often (e.g. every day or almost every day). This finding suggests, on the one hand, that excessive participation in such activities and classes in school – perhaps at the expense of other “core” curriculum areas – may not be conducive to developing stronger creative thinking skills. On the other hand, participating irregularly, for instance just once or twice every semester, is not ideal either for developing creative thinking skills. It may be that activities that are consistently embedded within the curriculum and that engage students in tasks that require creative thinking on a regular but considered basis (e.g. as part of lessons taken once or twice a week in secondary education) may be best for developing students’ skills.

It is also important to note that the PISA 2022 Creative Thinking assessment measured students’ capacity to think flexibly and to make original and appropriate idea associations, rather than their artistic talents. For example, in the visual expression domain, students’ outputs were not evaluated with respect to their aesthetic quality but rather with respect to the originality of their idea associations. Similarly, students were not judged on the quality of their writing but rather on their capacity to suggest an unconventional story idea. In order to perform well on the test, students had to draw on cognitive skills like flexible thinking and, in some domain contexts (e.g. scientific problem solving), combine these skills with their knowledge; these cognitive assets are developed through challenging, active learning activities across subject areas. The weak associations observed between activities that belong to the wider domain of “the arts” and students’ scores in the PISA test are thus not so surprising. Put differently, while theatre or music classes surely help students to express themselves in a performative manner, they do so by enacting ideas that are not their own and they are rarely asked to come up with new ideas or to produce their own original outputs.

Similarly, art classes may teach students how to draw, paint or sculpt with the right techniques, but this not what tasks in the visual expression domain in the PISA assessment aimed to capture – and what the digital drawing tool allowed (i.e. only combining shapes and stamps). Nonetheless, across participating countries and economies, students who participate in art classes at least once a week were more likely than their peers to get full credit on visual expression tasks (average odds ratio = 1.05), and especially so for the more difficult items that required students to evaluate and improve ideas (average odds ratio = 1.10) (Table III.B1.6.18). As described in Box III.4.2 in Chapter 4, full credit responses for these items required students to combine lines, shapes, stickers and colours to create relevant objects of significance – thus likely aided by some level of visual art or graphic design skill.

Figure III 6.7. Student participation in activities at school and creative thinking proficiency

Mean score in creative thinking; OECD average

Source: OECD, PISA 2022 Database, Tables III.B1.6.7, III.B1.6.8, III.B1.6.11 and III.B1.6.14. The StatLink URL of this figure is available at the end of the chapter.

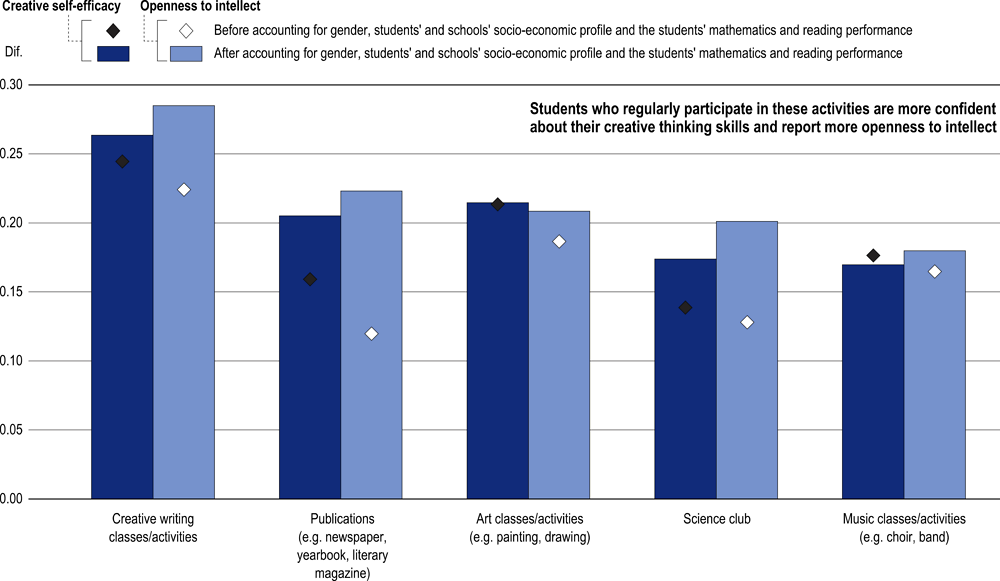

The relationship between participation in activities and performance is complex, in part because of self-selection issues. Regular but moderate participation seems to be most productive for developing the fundamental cognitive processes required for creative thinking. Yet, developing more specialised domain readiness via such activities seems productive for helping students to apply creative thinking in difficult tasks that also require them to combine creative thinking skills with other skills, for instance visual expression (see Chapter 4 for more details). Finally, beyond student performance in the PISA test, weekly participation in school activities is positively associated with a range of student attitudes that in turn support creative thinking, such as creative self-efficacy and openness to intellect (Figure III.6.8, see also Chapter 5). These positive associations held for all types of activities, across all participating countries and economies, and after accounting for students’ and schools’ characteristics and students’ mathematics and reading performance. The strongest associations were observed amongst students who take part in creative writing classes/activities, publications activities, and art classes/activities at least once a week (above 0.2 points in both the index of creative self-efficacy and in the index of openness to intellect, on average across OECD countries).

Figure III 6.8. Student participation in activities at school and their attitudes towards creative thinking

Mean index difference between students who participate at least once a week in the following activities compared to the rest of students; OECD average

Notes: All differences are statistically significant (see Annex A3).

Items are ranked in descending order of the difference in the index of openness to intellect, after accounting for gender, students' and schools' socio-economic profile and the students' maths and reading performance.

Source: OECD, PISA 2022 Database, Tables III.B1.6.23 and III.B1.6.24. The StatLink URL of this figure is available at the end of the chapter.

Digitalisation and creative thinking

Digitalisation permeates all sectors and layers of society, and the social environment of 15-year-old students makes no exception. As students use digital devices both in class and at home – and often the same devices for both – the frontiers of the school environment have become blurred. Moreover, students’ uses of digital resources for different purposes are also increasingly intertwined as they mix learning and leisure in overlapping times and spaces.

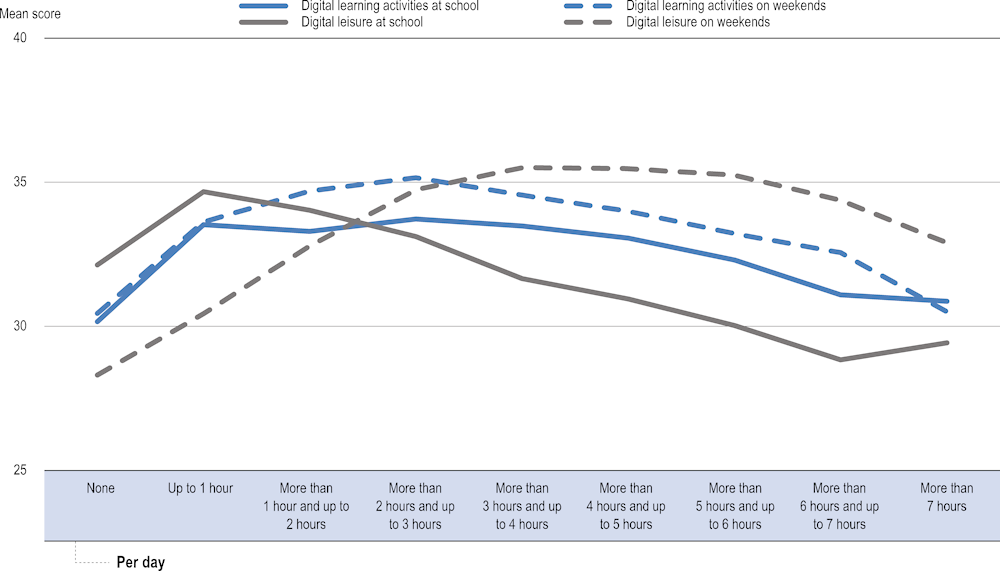

Though challenging in many aspects, the digitalisation of schools and school environments presents many (proven and potential) benefits for teaching and learning, when properly guided and supported (OECD, 2023[23]; OECD, 2021[24]). PISA 2022 data showed that it is not necessarily the time spent using digital resources that makes a difference to students’ performance in mathematics, but rather the purpose and context in which they use them (OECD, 2023[25]). This section analyses how the time students spend on digital devices interacts with their creative thinking performance, and whether it plays out differently at school or at home, on weekdays or on weekends, and for learning or for leisure.

The use of digital resources and creative thinking performance

More and more, students use digital resources for learning activities, under the instruction of their teachers in class or on their own at home. Outside of school (either before or after school, or over the weekend), students who use digital resources for the purpose of learning performed better in creative thinking than those who do not, after accounting for students and schools’ characteristics. On average across OECD countries, about 50% of students reported spending at least one hour a day learning outside of school using digital resources, and they scored 0.8 points better than their peers from similar socio-economic backgrounds (Tables III.B1.6.25 and III.B1.6.32). Using digital resources for learning for at least one hour a day inside of school is also associated with better performance in creative thinking, but to a lesser extent (0.2 points). In short, the use of digital resources for learning has the same association with creative thinking performance as with mathematics’ (OECD, 2023[25]).

The use of digital resources for leisure, however, has a much stronger relationship with creative thinking performance than the use of digital resources for learning. On average across OECD countries, 69% of students reported using digital resources for leisure for one hour a day or more outside of school on a weekday; and 80% on a weekend day. These students significantly outscored their peers in creative thinking, by 2.5 and 3.3 points respectively. These score differences account for students’ and schools’ socio-economic backgrounds, so this performance gap cannot solely be reduced to a digital divide. At school, this relationship is inverted: students who spend an hour a day or more using digital resources for leisure scored, on average, 0.8 points below their peers. This finding aligns with the PISA 2022 Results (Volume II) observation that, above one hour a day of use at school, students’ mathematics performance decreases with their use of digital devices for leisure (OECD, 2023[25]).

Unsurprisingly, even when used at the weekend, spending too many hours on digital devices – regardless of purpose – is associated with a decrease in creative thinking performance. Interestingly though, this inflection point is later for leisure time than it is for learning time (Figure III.6.9). One explanation might be that students who make the biggest use of digital tools for learning during the weekend are those who may already struggle with school, and therefore turn to digital learning activities in order to catch up. Another explanation is that leisure time, digital or otherwise, is important for well-being and therefore beneficial to students’ learning and their proficiency in creative thinking – especially if this digital leisure time involves some creative processes.

Figure III 6.9. Student use of digital devices and creative thinking proficiency

Mean score in creative thinking; OECD average

Note: Accounting for gender and students’ and schools’ socio-economic profiles, all paired differences are statistically significant at school, except for the difference between “more than 7 hours a day” and “more than 6 hours and up to 7 hours” at school for leisure.

Source: OECD, PISA 2022 Database, Tables III.B1.6.26, III.B1.6.28, III.B1.6.29 and III.B1.6.31. The StatLink URL of this figure is available at the end of the chapter.

On a typical weekend day, students who spend an hour or more playing videogames (60% of students on average across OECD countries) or browsing social networks (76%) scored slightly better than those who do not, scoring 0.5 and 0.2 points higher on average across OECD countries, respectively, after accounting for gender and students’ and schools’ socio-economic profile. In contrast, students who spend at least one hour communicating and sharing digital content on social networks or communication platforms (56%), listening to or reading information materials to learn how to do something (39%), creating or editing personal digital content (37%), or looking for practical information online (37%) scored below those who spend less time on these digital activities in creative thinking (Tables III.B1.6.46 and III.B1.6.54). Here again, after a certain threshold, spending too much time on any type of digital leisure activities, even on weekends, is associated with a decrease in creative thinking performance.

Table III 6.2. School environment and creative thinking: Chapter 6 figures and tables

|

Figure III.6.1 |

PISA 2022 coverage of aspects of the students' educational environment related to creative thinking |

|

Figure III.6.2 |

Students’ and school principals’ growth mindset on creativity |

|

Figure III.6.3 |

Student-reported use of pedagogies encouraging creative thinking |

|

Figure III.6.4 |

Students’ and school principals’ views on their teachers' use of pedagogies encouraging creative thinking |

|

Figure III.6.5 |

Pedagogies encouraging creative thinking and creative thinking proficiency across assessment domains and facets |

|

Figure III.6.6 |

Availability of activities offered at school, by school socio-economic profile |

|

Table III.6.1 |

Students’ participation in activities at school |

|

Figure III.6.7 |

Student participation in activities in school and creative thinking proficiency |

|

Figure III.6.8 |

Student participation in activities at school and their attitudes towards creative thinking |

|

Figure III.6.9 |

Student use of digital devices and creative thinking proficiency |

References

[14] Agryris, C. (1982), “The executive mind and double-loop learning”, Organizational Dynamics, Vol. 11/2, pp. 5-22, https://doi.org/10.1016/0090-2616(82)90002-x.

[17] Chia, R. (2003), “From Knowledge-Creation to the Perfecting of Action: Tao, Basho and Pure Experience as the Ultimate Ground of Knowing”, Human Relations, Vol. 56/8, pp. 953-981, https://doi.org/10.1177/00187267030568003.

[11] Collins, A., J. Brown and S. Newman (1989), Cognitive apprenticeship: teaching the creaft of reading, writing and mathematics, L. B. Resnick (ed.).

[15] Cunliffe, A. (2002), “Reflexive Dialogical Practice in Management Learning”, Management Learning, Vol. 33/1, pp. 35-61, https://doi.org/10.1177/1350507602331002.

[21] Howard-Jones, P. (2002), “A Dual-state Model of Creative Cognition for Supporting Strategies that Foster Creativity in the Classroom”, International Journal of Technology and Design Education, Vol. 12/3, pp. 215-226, https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1020243429353.

[13] Kaufman, J. and R. Beghetto (2009), “Beyond Big and Little: The Four C Model of Creativity”, Review of General Psychology, Vol. 13/1, pp. 1-12, https://doi.org/10.1037/a0013688.

[22] Lucas, B. (2022), Creative thinking in schools across the world: A snapshot of progress in 2022.

[19] Musset, P. (2019), “Improving work-based learning in schools”, OECD Social, Employment and Migration Working Papers, No. 233, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/918caba5-en.

[9] Nickerson, R. (2010), “How to Discourage Creative Thinking in the Classroom”, in Nurturing Creativity in the Classroom, Cambridge University Press, https://doi.org/10.1017/cbo9780511781629.002.

[6] OECD (2024), Social and Emotional Skills for Better Lives: Findings from the OECD Survey on Social and Emotional Skills 2023, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/35ca7b7c-en.

[10] OECD (2023), Building Future-Ready Vocational Education and Training Systems, OECD Reviews of Vocational Education and Training, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/28551a79-en.

[25] OECD (2023), Learning during - and from - disruption, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/a97db61c-en.

[23] OECD (2023), OECD Digital Education Outlook 2023: Towards an Effective Digital Education Ecosystem, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/c74f03de-en.

[1] OECD (2023), Supporting Students to Think Creatively: What Education Policy Can Do, https://issuu.com/oecd.publishing/docs/supporting_students_to_think_creatively_web_1_.

[24] OECD (2021), OECD Digital Education Outlook 2021: Pushing the Frontiers with Artificial Intelligence, Blockchain and Robots, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/589b283f-en.

[5] Robinson, K. and L. Aronica (2009), The element: How finding your passion changes everything, Penguin.

[8] Rubenstein, L., D. McCoach and D. Siegle (2013), “Teaching for Creativity Scales: An Instrument to Examine Teachers’ Perceptions of Factors That Allow for the Teaching of Creativity”, Creativity Research Journal, Vol. 25/3, pp. 324-334, https://doi.org/10.1080/10400419.2013.813807.

[7] Rubenstein, L. et al. (2018), “How teachers perceive factors that influence creativity development: Applying a Social Cognitive Theory perspective”, Teaching and Teacher Education, Vol. 70, pp. 100-110, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2017.11.012.

[2] Sarson, S. (1990), The predictable failure of educational reform.

[3] Sharan, S. and I. Tan (2008), Organizing schools for productive learning, New York: Springer.

[4] Sternberg, R. (2007), Creativity as a habit.

[12] Stierand, M. (2014), “Developing creativity in practice: Explorations with world-renowned chefs”, Management Learning, Vol. 46/5, pp. 598-617, https://doi.org/10.1177/1350507614560302.

[16] Tsoukas, H. and R. Chia (2002), “On Organizational Becoming: Rethinking Organizational Change”, Organization Science, Vol. 13/5, pp. 567-582, https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.13.5.567.7810.

[20] Ulger, K. (2018), “The Effect of Problem-Based Learning on the Creative Thinking and Critical Thinking Disposition of Students in Visual Arts Education”, Interdisciplinary Journal of Problem-Based Learning, Vol. 12/1, https://doi.org/10.7771/1541-5015.1649.

[18] Usmeldi, U. and R. Amini (2022), “Creative project-based learning model to increase creativity of vocational high school students”, International Journal of Evaluation and Research in Education (IJERE), Vol. 11/4, p. 2155, https://doi.org/10.11591/ijere.v11i4.21214.

Notes

← 1. National Improvement Hub: https://education.gov.scot/improvement/.

← 2. Creativity Toolbox: https://education.gov.scot/improvement/learning-resources/creativity-toybox/; Planning for and Evaluating Creativity ZIP file: https://education.gov.scot/improvement/self-evaluation/planning-for-and-evaluating-creativity/.

← 3. Creativity Portal: https://creativityportal.org.uk/.

← 4. FabLabs: https://fablab.is/.

← 5. Centre for Real-World Learning: https://www.winchester.ac.uk/research/Our-impactful-research/Research-in-Education/Centres-and-Institutes-in-Education/Centre-for-Real-World-Learning.

← 6. Unless otherwise specified, the “activities offered at school” refer to classes and activities students participate in during school, which might include activities during their core, mandatory formal education classes, or elective classes that form part of their formal education, or extra-curricular activities that take place at school.