This chapter presents housing outcomes and policy challenges in Lithuania. It discusses housing quality, affordability and the environmental sustainability of the stock and discusses the types of households who are unable to reasonably afford housing based on market prices and income levels. The chapter concludes with a discussion of the challenging economic, political and policy context, with a cost-of-living crisis, increasing interest rates, rising energy prices and construction costs and the ongoing Russian war of aggression against Ukraine putting additional pressures on housing affordability.

Policy Actions for Affordable Housing in Lithuania

2. The Lithuanian housing market: Quality and affordability gaps in a challenging policy context

Abstract

2.1. Introduction and main findings

As in many countries in the region, the historical development of housing in Lithuania continues to have implications for the tenure, type, quality and affordability of housing in the present day. The housing stock expanded rapidly during the Soviet period, during which over 40% of today’s dwellings were built, which was followed by the generalised privatisation of state‑owned housing in the transition to a market economy. As a result, the legacy of housing development has significantly shaped today’s housing market characteristics and challenges:

Lithuania has one of the highest rates of homeownership in the OECD, with 8 in 10 households owning their home outright.

The housing stock is ageing and, for many households across the income distribution, of poor quality.

The majority of the housing stock is comprised of multi‑apartment buildings (over half of them built during the Soviet era), which are commonly located in and around cities.

The residential sector has a large environmental footprint, as it is a big consumer of energy and generates significant GHG emissions; by extension, many households struggle with energy poverty, which rising energy prices in 2022 are likely to aggravate.

House prices have increased significantly, and at a faster rate than the OECD and EU averages over the past decade; the COVID‑19 pandemic has accelerated real house price and (following several quarters of stabilisation during the first phase of the pandemic) rent increases.

Although average household spending on housing remains low due in part to the high rate of outright homeowners, this belies important affordability challenges, particularly among young households and those living in poor quality housing who cannot afford to access a mortgage, change homes, or improve their dwelling.

Strong inflationary pressures – driven by increasing food and energy prices – and a decline in real wages, create additional barriers to housing affordability, while rising construction costs challenge the policy response to expand and improve the supply of affordable housing. Since February 2022, the unprovoked Russian war of aggression against Ukraine has resulted in an influx of thousands of Ukrainian refugees into Lithuania, and across European – and, to a lesser extent, other OECD – countries, putting pressures on the housing market and the current public support schemes (Box 2.1).

This chapter assesses the Lithuanian housing market and the primary challenges facing policy makers. The first section provides a brief profile of the housing market, with a focus on housing tenure and quality. The second section examines emerging affordability challenges, including rising housing prices and affordability gaps. The third section explores the environmental sustainability of the housing stock. The fourth section concludes with a discussion of the challenging policy context, due to inflationary pressures and rising construction costs, and an assessment of demographic trends and their potential implications for housing demand.

Box 2.1. Impacts of the war in Ukraine on the Lithuanian housing market

The Russian war of aggression in Ukraine has already displaced nearly 8.2 million individuals as of 18 April 2023, a majority of whom remain in Ukraine’s neighbouring countries (UNHCR, 2023[1]).

As of 11 April 2023, Lithuania has registered over 76 000 individuals from Ukraine under Temporary Protection Schemes, which grants rights and access to services to refugees from Ukraine in European Union member states – including the right to access suitable accommodation/housing or the means to obtain it (UNHCR, 2023[1]). As outlined in OECD (2022[2]), different forms of housing support have been provided to Ukrainian refugees in Lithuania, from private individuals, the government, and NGOs:

In Lithuania and across Europe, many refugees have found accommodation in private households, who offered spare rooms in their dwellings on a voluntary basis. Others were offered accommodation directly by national governments and municipalities (OECD, 2022[2]). Additionally, a website has been set up that matches Ukrainians looking for accommodation in Lithuania with hosts and co‑ordinates drivers from the border (https://stipruskartu.lt/). Data on this website and reports from municipalities confirm that there is a strong preference for accommodation in Vilnius and Klaipėda, as these cities have Russian speaking schools and offer the best job opportunities (OECD, 2022[2]). The Lithuanian Government provides monthly financial support for private hosts of EUR 150 for the first person and EUR 50 for every additional person hosted in the same dwelling.

The government has also made efforts to adapt its existing housing support policies to provide targeted support to Ukrainian refugees. They are eligible for housing benefits and access to, where available, social housing.

Municipalities are in charge of co‑ordinating the transition from emergency housing to longer-term accommodation (OECD, 2022[2]).

The uncertain nature and duration of the war renders predictions about the duration of stay impossible. Potential short, medium and long-term impacts on the Lithuanian housing sector, especially dwellings targeted at low-income groups in urban areas, must be closely monitored going forward.

Source: (OECD, 2022[2]), “Housing support for Ukrainian refugees in receiving countries”, https://doi.org/10.1787/9c2b4404-en; (UNHCR, 2023[1]), Operational Data Portal: Situation Ukraine Refugee Situation, https://data.unhcr.org/en/situations/ukraine.

Across OECD and EU countries, housing affordability has received increasing policy attention in recent years. Ensuring access to affordable housing is an explicit policy objective in most OECD countries (OECD, 2022[3]). Concerns around housing affordability have also generated a number of recommendations to support public authorities in making housing more affordable (Box 2.2).

Box 2.2. Recommendations to promote affordable housing in OECD and EU countries

The “Declaration of the Ministers”, released at the Informal Conference of EU Ministers responsible for housing organised in Nice, France, in March 2022 under the French EU Presidency, includes a number of recommendations to promote housing affordability.

The joint UNECE-Housing Europe report, #Housing2030: Effective Policies for Affordable Housing in the UNECE region, provides guidance and best practice with respect to governance, finance, land and climate‑neutral housing.

The Housing Partnership of the Urban Agenda for the EU developed a 12‑point action plan in 2018 to support local authorities to invest in affordable housing.

Source: (French Presidency of the Council of the European Union, 2022[4]), “Informal conference of EU Ministers responsible for Housing – Declaration of the Ministers”, https://www.ecologie.gouv.fr/sites/default/files/08.03.2022_DeclarationNice.pdf; (UNECE and Housing Europe, 2021[5]), #Housing2030: Effective policies for affordable housing in the UNECE region, https://unece.org/sites/default/files/2021-10/Housing2030%20study_E_web.pdf; (Urban Agenda for the EU, 2018[6]), “The Housing Partnership Action Plan”, https://ec.europa.eu/futurium/en/system/files/ged/final_action_plan_euua_housing_partnership_december_2018_1.pdf.

2.2. Profile of the Lithuanian housing market

Lithuania’s housing market is similar to that of many neighbouring countries, with a very high home ownership rate, a thin rental market, and a very residual social housing sector. Much of the stock is ageing and of poor technical quality, with key gaps in basic amenities. While housing quality has improved in recent decades, progress remains slow. Multi-family dwellings comprise the majority of the housing stock, many of them built during the Soviet era in and around cities.

2.2.1. An ageing housing stock with large and persistent quality gaps

Despite progress in recent years, poor housing quality is a persistent challenge. Nearly 80% of the housing stock was built before 1993, around half of which was developed during the Soviet era (Government of the Republic of Lithuania, 2021[7]). In addition to poorer quality construction materials and lower construction standards that were more prevalent in housing built before 1990s, a formal institutional and legal framework for the maintenance and operation of the dwellings was not introduced at the time of privatisation, which has led to considerable maintenance gaps. Moreover, as will be discussed in the next section, many households struggle to afford to maintain their homes. As a result, much of the stock – particularly the multi-family segment – is ageing and of poor quality, due to the absence of insulation materials used during the construction process, combined with low rates of building renovations in recent years.

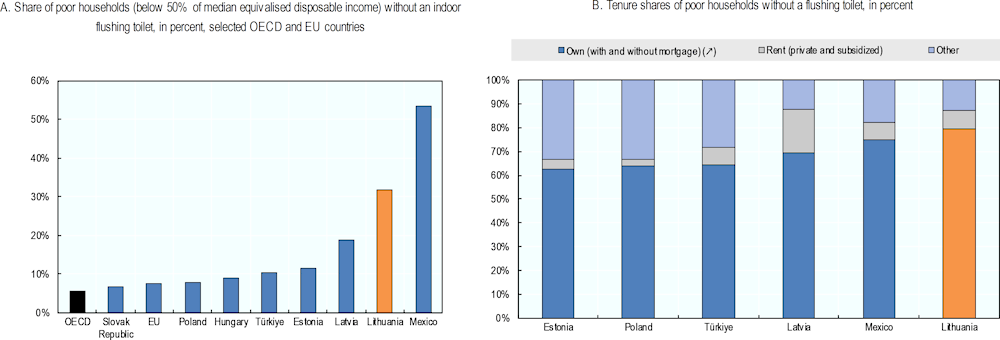

Lithuania registers a comparatively large share of poor households living in dwellings that lack basic amenities, such as an indoor flushing toilet. Around three in ten poor households – those with less than 50% of the median equivalised disposable income – live in such dwellings, compared to an OECD average of less than 6% (Figure 2.1, Panel A). As is the case in most countries with high levels of households lacking basic amenities, the vast majority of affected households live in owner-occupied dwellings (Figure 2.1, Panel B). Meanwhile, around 16% of homeowners in the bottom quintile of the income distribution and 15% in the third quintile live in overcrowded conditions, which is higher than the OECD average.

Poor housing quality also affects a large share of the social and municipal rental stock (which are both managed by municipalities, with tenants in municipal housing not being subject to the income eligibility criteria of social housing tenants). In Vilnius, for instance, the municipality reports that around 60% of the social and municipal stock (over 3 300 dwellings) is partially deteriorated, and one in five dwellings is in unsatisfactory condition (substantially deteriorated). The municipal stock is relatively worse‑off in Vilnius than the social stock: only one‑third of the municipal stock is considered to be of very good or good quality (data provided by the Vilnius Municipal Housing Enterprise).

Figure 2.1. Housing quality remains a persistent challenge, measured in terms of access to basic amenities as well as energy performance

Note: Panel A: Poor households are households with equivalised disposable income below 50% of the median country income. In Mexico, gross income is used due to data limitations. Results only shown if category composed of at least 100 observations. In Türkiye, net income is not adjusted for income taxes due to data limitations. Panel B: Breakdown by tenure type only shown for countries where more than 5% poor households do not dispose of a flushing indoor toilet and 100 or more of the sampled poor households reported lack of an indoor flushing toilet. Poor households are households with equivalised disposable income below 50% of the median country income. In Mexico, gross income is used due to data limitations. The category “Other, unknown tenure” is composed of free accommodation and/or unknown or unclear types of tenure.

Source: (OECD, 2022[3]), Affordable Housing Database – OECD, indicator HC2.2.

Nevertheless, housing quality has improved over the past decades, though much remains to be done. Since 2010, the share of households living in dwellings without a flushing toilet has dropped among non-poor households by 10 percentage points to 6.7% in 2019, and to a lesser extent – by nearly 6 percentage points – among poor households (OECD, 2022[3]). Over the same period, the share of households living in overcrowded conditions dropped by around 20 percentage points for households in all income quintiles (OECD, 2022[3]). Nevertheless, the pace of residential renovations has been uneven over the past decades, during which a number of programmes have been undertaken (discussed later in this Chapter).

2.2.2. A nation of homeowners, with a thin rental market

Most households own their home outright, and the private and social rental markets remain shallow

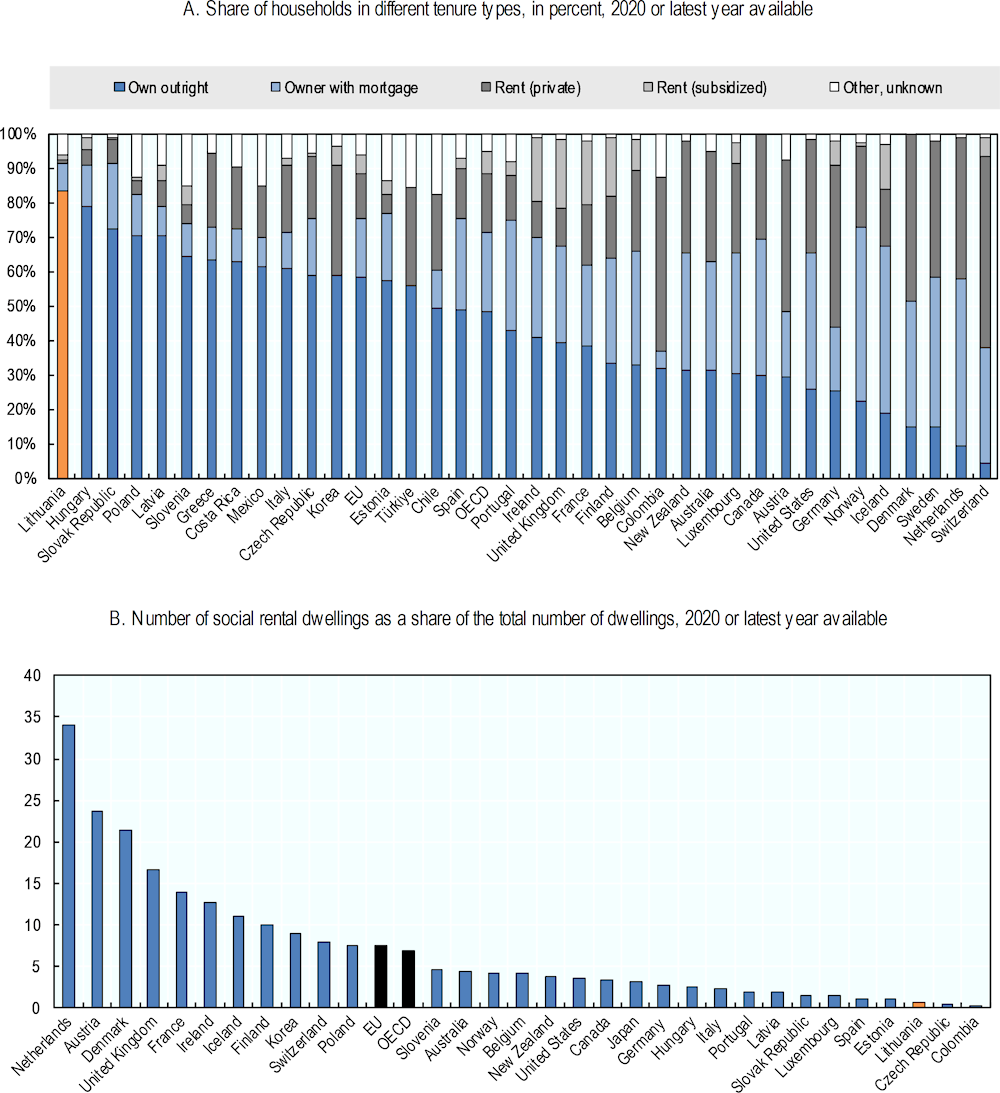

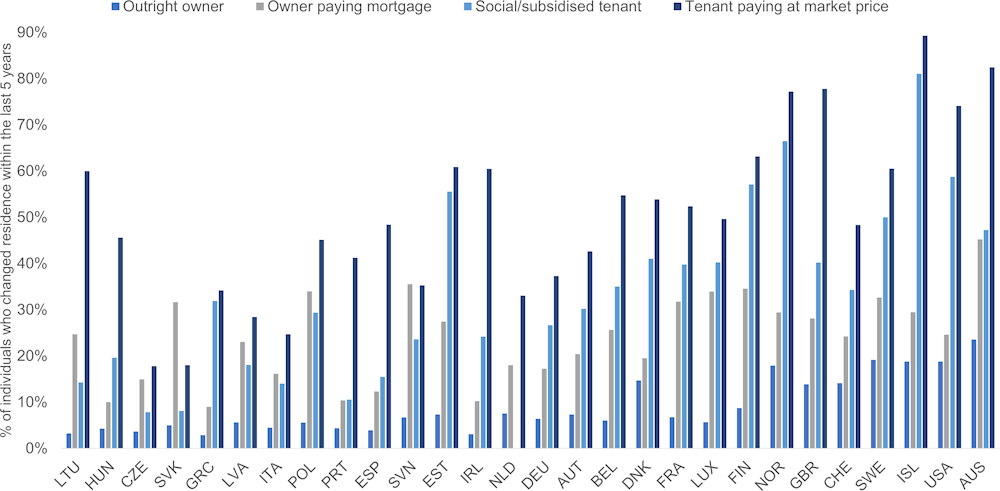

A legacy of the generalised privatisation of the state‑owned rental housing stock that began in the early 1990s, Lithuania has the highest rate of home ownership in the OECD, with over 90% of households owning their home, of which 8 out of 10 households own their home outright. The high rate of home ownership can be an obstacle to labour mobility: in Lithuania, outright owners are more than 40 percentage points less likely to move than private renters (Causa and Pichelmann, 2020[8]). This is the case for households across the country, given the shallow mortgage market, but especially for homeowners in rural areas who generally cannot acquire sufficient resources to move to an adequate dwelling in urban areas even if they sell their home in the countryside (Blöchliger and Tusz, 2020[9]).

By contrast, the formal rental market is extremely thin. Fewer than 3% of households formally rent their dwelling: just over half of tenants live in social or municipal housing (1.6%), with an even smaller share in formal private rental housing (0.8%) (Figure 2.2, Panel A). Nevertheless, the true size of the rental market is likely bigger, in light of the shadow rental market, which – while hard to quantify1 – persists, and is exacerbated by lenient regulatory provisions, including the continued use of oral contracts (see Chapter 3).

Lithuania has one of the smallest stocks of social housing in the OECD (Figure 2.2, Panel B). The most recent estimates suggest that just under one‑third of the total municipal housing stock (of around 39 700 dwellings) is rented out as social housing, equivalent to around 11 900 dwellings, or 0.5% of the total stock (Council of Europe Development Bank (CEB), 2019[10]). Demand for social housing far outweighs the supply. The Ministry of Social Security and Labour estimates approximately 10 000 people on the waiting list for social housing (just under 1% of the population), with an average wait time of around six years. In Vilnius alone, there are over 1 600 households on the waiting list for social housing; just under one‑third have been on the waiting list for more than 5 years.

The social housing stock is complemented by municipal housing, also managed by local authorities, but for which the eligibility requirements are less strict and, since 2019, for which rents are to be set at market rates (with a few exceptions) (see discussion in Chapter 3). The transformation of the municipal housing stock since the 1990s has been staggering: in 1990, municipal housing accounted for over 60% of all dwellings, compared to less than 2% today; construction of new municipal dwellings has dropped from nearly 30 000 new units per year in the 1980s to 120 units per year in the 2000s (Council of Europe Development Bank (CEB), 2019[10]).

As discussed below, the quality of the social and municipal stock is also highly uneven. The highly residual stock of social and municipal housing is smaller than in neighbouring transition countries, and results in part from the heavy policy focus on home ownership at the time of the transition.

Figure 2.2. Lithuania has the highest rate of home ownership in the OECD and one of the smallest shares of social housing

Note: Panel A: See note to Figure HM1.3.1 in indicator HM1.3 in the OECD Affordable Housing Database. Panel B: See note to Figure PH4.2.1 in indicator PH4.2 in the OECD Affordable Housing Database. For Lithuania, the share of social housing is calculated based on the previous years’ total dwelling stock due to data limitations.

Source: (OECD, 2022[3]), Affordable Housing Database – OECD, indicators HM1.3 and PH4.2, http://www.oecd.org/social/affordable-housing-database.htm.

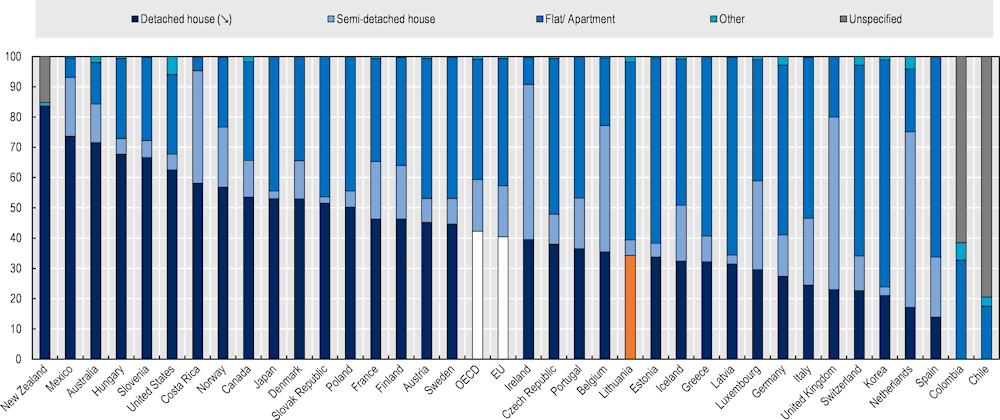

2.2.3. Dominance of apartment buildings

Apartment buildings make up nearly 60% of the occupied residential stock, which is much higher than the OECD and EU average of around 40% (Figure 2.3). Nearly all apartment buildings have multiple owners (which include natural persons, legal entities, or a mix of the two), which generally makes it more challenging to undertake large‑scale renovation projects. Detached, single‑family homes represent over a third of the occupied residential stock, just below the OECD and EU average of around 40%. Around three‑quarters of detached homes are owned by individual households (natural persons).

Figure 2.3. Multi-family dwellings dominate the housing stock in Lithuania

Notes: Data on residential dwelling stock refer to 2020, except for Costa Rica (2021), the United States (2019), Canada, Colombia, Iceland, Japan, New Zealand, Chile (2017) and Australia (2016).

The classification and terminology on types of dwelling may differ slightly from country to country. In general, “detached houses” refer to dwellings having no common walls with another unit. “Semi-detached houses” refer to dwellings sharing at least one wall or a row of (more than two) joined-up dwellings. “Flats/apartments” refer to dwelling units in a building sharing some internal space or maintenance and other services with other units in the building. “Other” refers to other types of dwellings, including mobile homes, caravans or houseboats.

It is not possible to distinguish between semi-detached houses and flats/apartments for New Zealand, or between detached and semi-detached houses for Chile or Colombia. These dwelling types are therefore classified as unspecified.

Source: (OECD, 2022[3]), Affordable Housing Database – OECD, indicator HM1.5, http://www.oecd.org/social/affordable-housing-database.htm.

2.3. The emerging housing affordability challenge

Although housing prices have been on the rise, average household spending on housing remains relatively low, and few households are overburdened by housing costs. Rising incomes have also mitigated to some extent the impact of an increase in house prices, up until the start of the pandemic. Nevertheless, house prices vary considerable across regions and among different dwelling types, with faster growth in recent years concentrated outside the Capital region among new single‑family homes. An insufficient social housing stock, with long wait times and a strong social stigma associated with social housing tenants, reflect affordability challenges for the most vulnerable. Moreover, the majority of Lithuanian households are credit-constrained and struggle to afford a mortgage for a typical flat in the three largest cities, Vilnius, Kaunas and Klaipėda.

2.3.1. Rise in housing prices, with big variation across regions and dwelling types

Increasing house and rent prices

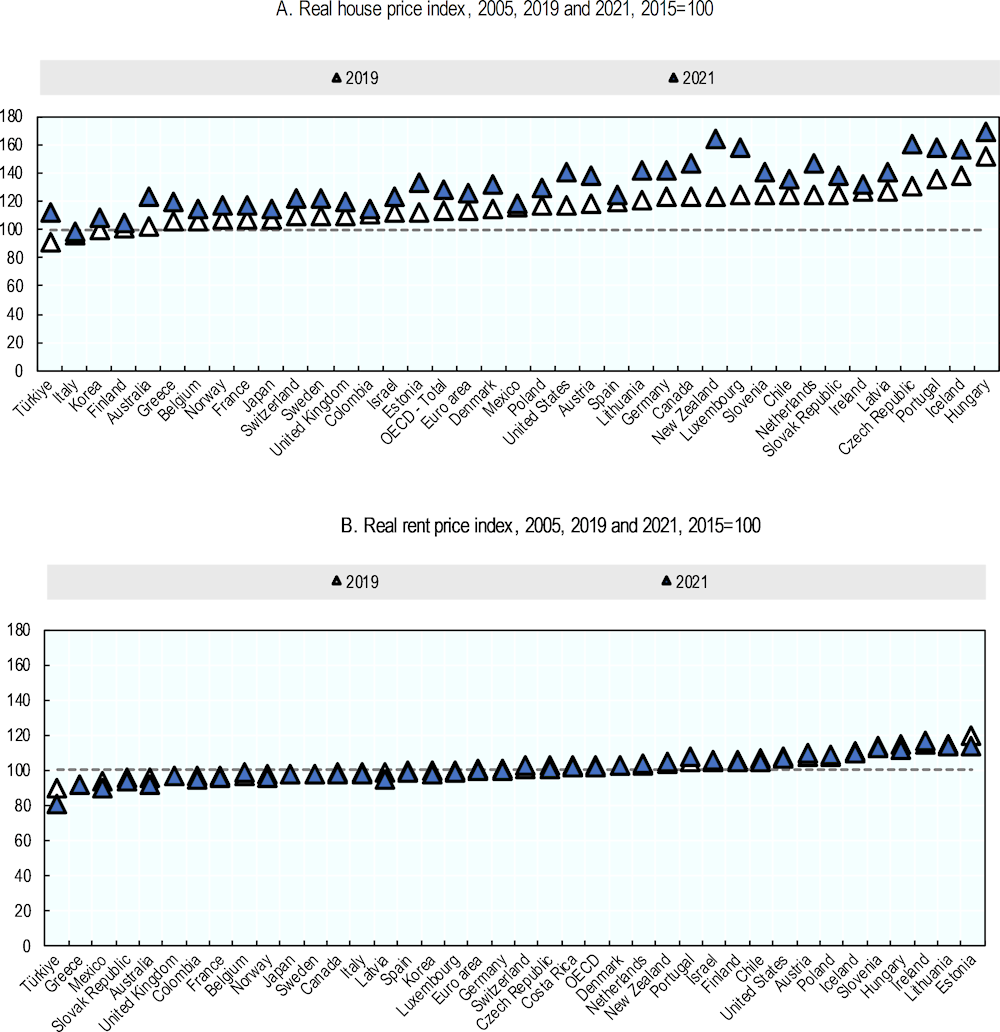

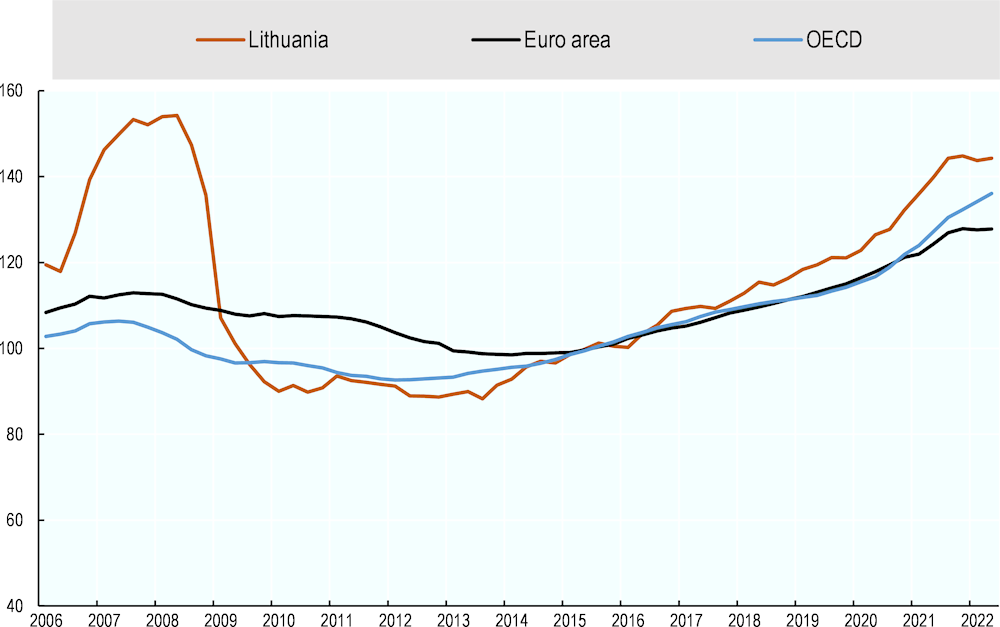

Housing prices in Lithuania increased substantially over the past decade, and at a faster rate than the OECD and Euro Area averages. Between 2010 and 2019, real house prices rose by 33% in Lithuania, well above the OECD and EU averages of 17% and 6%, respectively, over the same period (Figure 2.4, Panel A). Real house prices have continued to rise through the COVID‑19 pandemic, increasing by 18% between 2019 and 2021 in Lithuania, much more than the OECD and Euro Area averages of 14% and 10%, respectively, over this period. Meanwhile, prior to the COVID‑19 pandemic, real rent prices increased by nearly 70% in Lithuania between 2010 and 2019, representing the second-highest jump in the OECD over this period, after Estonia (Figure 2.4, Panel B). During the pandemic, between 2019 and 2021, rents in Lithuania dropped slightly by around 1%, reflecting the much more muted impact of COVID‑19 on rental prices relative to house prices, consistent with evidence from other OECD countries.

Looking further back in time, Lithuania faced a dramatic drop in real house prices between 2008 and 2010, followed by a relative stabilisation in the years following the Global Financial Crisis. Since then, real house prices have resumed their upward trajectory, rising at a faster pace than the OECD and Euro Area averages (Figure 2.5). Between Q1 2014 and Q1 2020 – prior to the COVID‑19 crisis – real house prices averaged 5% year-on-year growth. Since the first year of the pandemic, however, real house price growth accelerated, with the year-on-year growth averaging 8% between Q2‑2020 and Q2‑2022. Real house price growth in Lithuania outpaced that in many other OECD countries, where, on average real house prices increased in the first phase of COVID‑19, due to increased demand for housing, record-low interest rates, increased savings for some households, and stifled housing supply due to a construction slowdown and economic restrictions put into place during the pandemic. Nevertheless, the first quarters of 2022 show some signs of slowing growth in real house prices, consistent with the trends in the OECD and Euro Area.

Rising incomes mitigated the effect of increasing house prices – up until the start of the pandemic

To a large extent, rising incomes helped to mitigate the effects of housing price growth in recent decades, although the early part of the pandemic challenged this trend. The price‑to‑income index, which represents one measure of average housing affordability, points to a period of relatively stable levels of housing affordability, on average, between 2012 and 2019 in the years following the Global Financial Crisis. In the second half of 2019, the price‑to‑income index began to decline, suggesting that housing affordability had slightly improved, as incomes rose faster than house prices, on average. However, the price‑to‑income ratio began to increase again in the second half of 2020, and at a much more rapid pace in 2021, suggesting a decline in housing affordability, which is likely caused by the rapid growth in house prices since the outset of the pandemic, without corresponding growth in income. The first quarters of 2022 again show some signs of increasing housing affordability.

Figure 2.4. House prices have been increasing in many OECD countries over the past decade – Lithuania was no exception

Notes: House price indices, also called Residential Property Prices Indices (RPPIs), are index numbers measuring the rate at which the prices of all residential properties (flats, detached houses, terraced houses, etc.) purchased by households are changing over time. Both new and existing dwellings are covered if available, independently of their final use and their previous owners. Only market prices are considered. They include the price of the land on which residential buildings are located (see OECD et al. (2013[11])). For Panel A, 2021 data were not available in Chile, Colombia, Greece, the Netherlands and New Zealand; as such, 2020 data were used. For Panel B, 2021 data refer to 2020 for Japan.

Due to data constraints, the OECD – Total for 2020 and 2021 is calculated using CPI country weights data from 2019.

Source: Calculations based on (OECD, 2023[12]), “Housing prices (indicator)”, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/63008438-en (accessed April 2022).

Figure 2.5. House prices in Lithuania increased over the past decade, and price increases accelerated during the first year of the COVID‑19 crisis, before levelling off in 2022

Source: (OECD, 2022[13]), “Prices: Analytical house price indicators”, https://doi.org/10.1787/cbcc2905-en.

House prices vary considerably across dwelling types and regions

There is significant variation in housing prices depending on the dwelling type and location. On average across Lithuania, flats in multi-dwelling buildings have a higher average purchase price than single‑family homes and duplexes, which were on average around 56% higher per square metre in Vilnius in 2021 and between 16‑29% higher per square metre in Klaipėda and Kaunas (Lithuania Statistical Office, 2022[14]). Further, the highest average purchase price is recorded in the three main cities. For single‑family homes and duplexes, the average purchase price was over EUR 1 230/m2 in Vilnius in 2021 – more than double the national average of EUR 599/m2 – and nearly EUR 950/m2 in Kaunas and just under EUR 1000/ m2 in Klaipėda (Lithuania Statistical Office, 2022[14]). For flats in multi-dwelling buildings (buildings with three or more flats), Vilnius recorded the highest average purchase price (over EUR 1930/m2 in 2021), followed by around EUR 1 220/m2 in Kaunas and over 1 150/m2 in Klaipėda (Lithuania Statistical Office, 2022[14]). Meanwhile, average purchase prices are lowest in Alytus, amounting to less than half of the average purchase price in Vilnius (around EUR 540/m2 for single‑family homes and duplexes, and EUR 670/m2 for flats in multi-family dwellings).

Between 2017 and 2021 – the average purchase price of housing has increased across Lithuanian cities, with a strong acceleration outside Vilnius, Kaunas and Klaipėda since the onset of the COVID‑19 pandemic. For instance, the average purchase price of single‑family homes and duplexes rose by at least 20% between 2019 and 2021 in Alytus, Panevėžys and Šiauliai – higher than the increase reported in Vilnius, Kaunas or Klaipėda. The same is true for flats in multi‑apartment dwellings over this period, where municipalities outside the largest three cities recorded higher growth (48% in Alytus, and just over 30% in Panevėžys and Šiauliai), compared to less than 30% in the three largest cities (Lithuania Statistical Office, 2022[14]). Meanwhile, the average annual rent prices for a flat recorded much more muted growth between 2019 and 2021 in Lithuanian cities for which data were available. Average annual rent prices increased most in Šiauliai (12%) and Klaipėda (7%), followed by Panevėžys (6%) and Vilnius (4%); in Kaunas, average annual rent prices dropped by 2% over this period (Lithuania Statistical Office, 2022[15]).

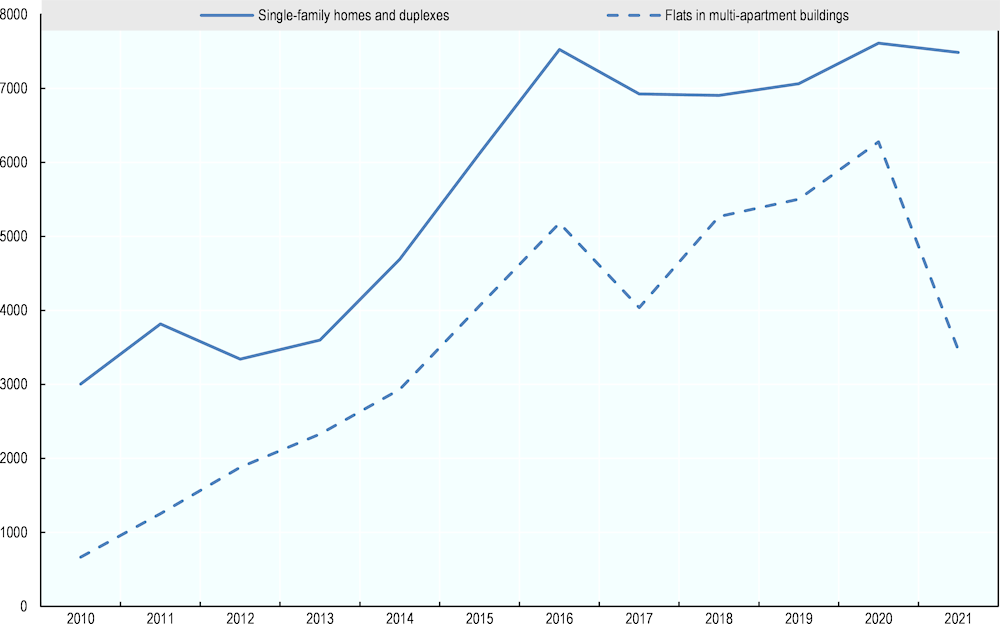

New housing construction has accelerated in recent years

The annual number of new dwellings completed nearly tripled over the past decade, from less than 3 700 new dwellings in 2010 to over 10 900 in 2021 (Lithuania Statistical Office, 2022[16]). Single‑family homes and duplexes account for more than two‑thirds of new dwelling completions in 2021, which is nevertheless a smaller share than a decade ago (82% in 2010) (Figure 2.6). Indeed, completions of flats in multi‑apartment buildings increased more than five‑fold by 2021 relative to 2010, compared to a more than doubling of the number of completions of single‑family homes and duplexes over this period (Lithuania Statistical Office, 2022[16]).

Figure 2.6. The number of new dwellings completed annually has increased significantly over the past decade

Source: (Lithuania Statistical Office, 2022[16]), “Number of dwellings completed”, https://osp.stat.gov.lt/statistiniu-rodikliu-analize?indicator=S8R717#/

2.3.2. Affordability gaps, despite relatively low housing costs

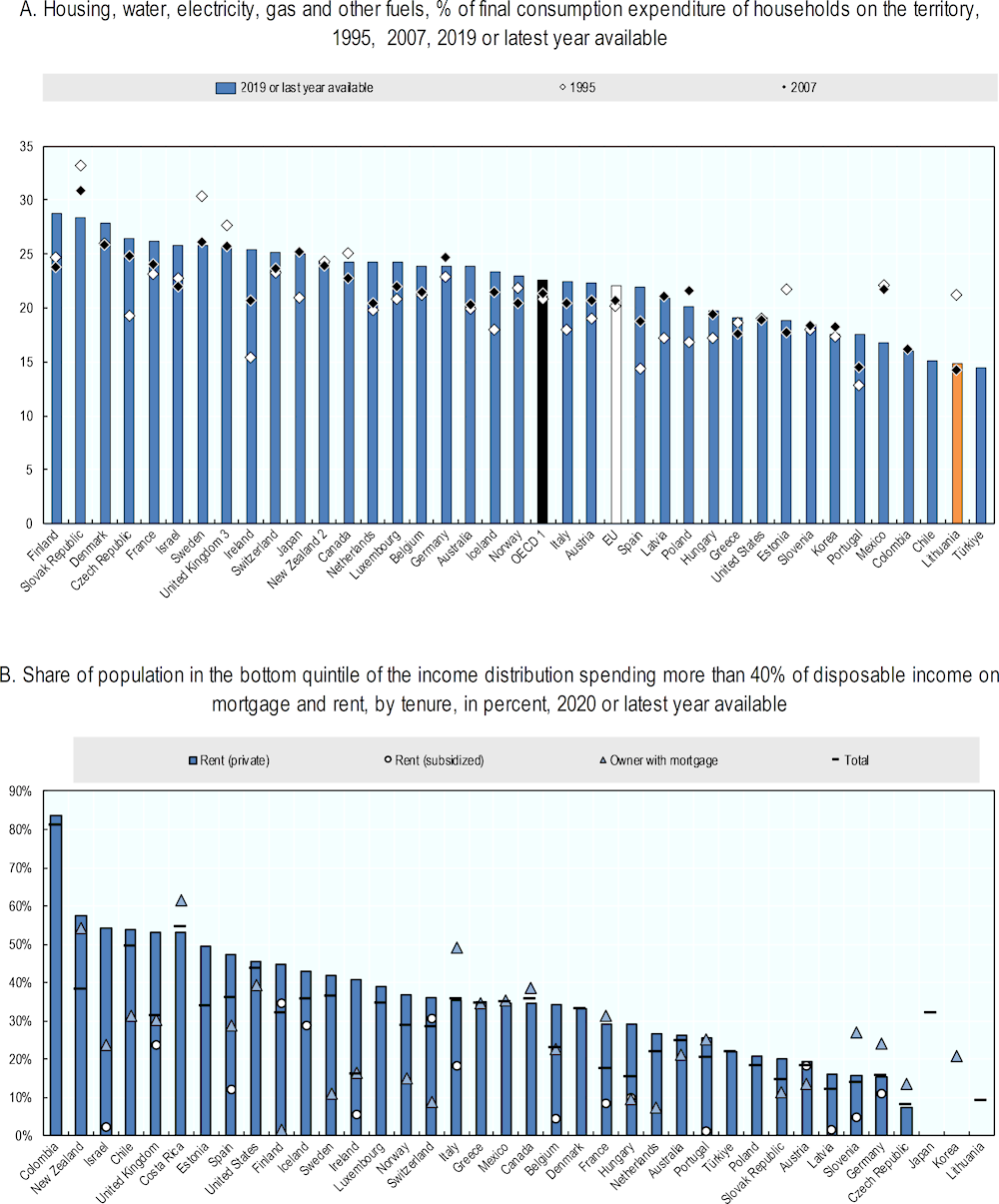

On average, housing costs are not high for most households

Compared to other OECD countries, Lithuania records among the lowest overall housing costs – which include housing, water, electricity, gas and other fuels – as a share of total household consumption expenditure, on average (Figure 2.7, Panel A). Average household spending on housing in Lithuania has generally decreased since 1995, to stabilise at around 15% of total consumption expenditure in 2019, well below the OECD average of 22.6% (OECD, 2022[3]). Moreover, fewer than 3% of Lithuanian households spend more than 40% of their disposable income on housing; this is one threshold to assess whether a household is considered to be overburdened by housing costs (see, for instance, (OECD, 2022[3]) for further discussion) (Figure 2.7, Panel B). Among households in the bottom quintile of the income distribution (not shown), the share of overburdened households reaches just over 9% – well below the OECD average of 27% of households in the bottom quintile. This is largely due to the high rate of outright homeowners in Lithuania, which means that few households make monthly mortgage or rental payments.

Figure 2.7. While overall housing costs remain low on average, many households cannot afford to keep their dwelling warm

Notes: Panel B: In Chile, Colombia, Korea, Mexico and the United States gross income instead of disposable income is used due to data limitations. No data available on subsidised rent in Australia, Canada, Chile, Mexico and the United States. In the Netherlands, Denmark, New Zealand and Sweden tenants at subsidised rate are included into the private market rent category due to data limitations. No data on mortgage repayments available for Denmark, Iceland and Türkiye. Results only shown if category composed of at least 100 observations.

1. Panel A: The OECD average over time is calculated using the data of the countries available for all years.

2. Panel A: Provisional values for 2019.

3. Panel A: The present publication presents time series which end before the United Kingdom’s withdrawal from the European Union on 1 February 2020. The EU aggregate presented here therefore refers to the EU including the United Kingdom. In future publications, as soon as the time series presented extend to periods beyond the United Kingdom withdrawal (February 2020 for monthly, Q1 2020 for quarterly, 2020 for annual data), the “European Union” aggregate will change to reflect the new EU country composition.

Source: (OECD, 2022[3]), Affordable Housing Database – OECD, http://www.oecd.org/social/affordable-housing-database.htm.

2.3.3. Purchasing or formally renting a home in the biggest cities is out of reach for many Lithuanian households

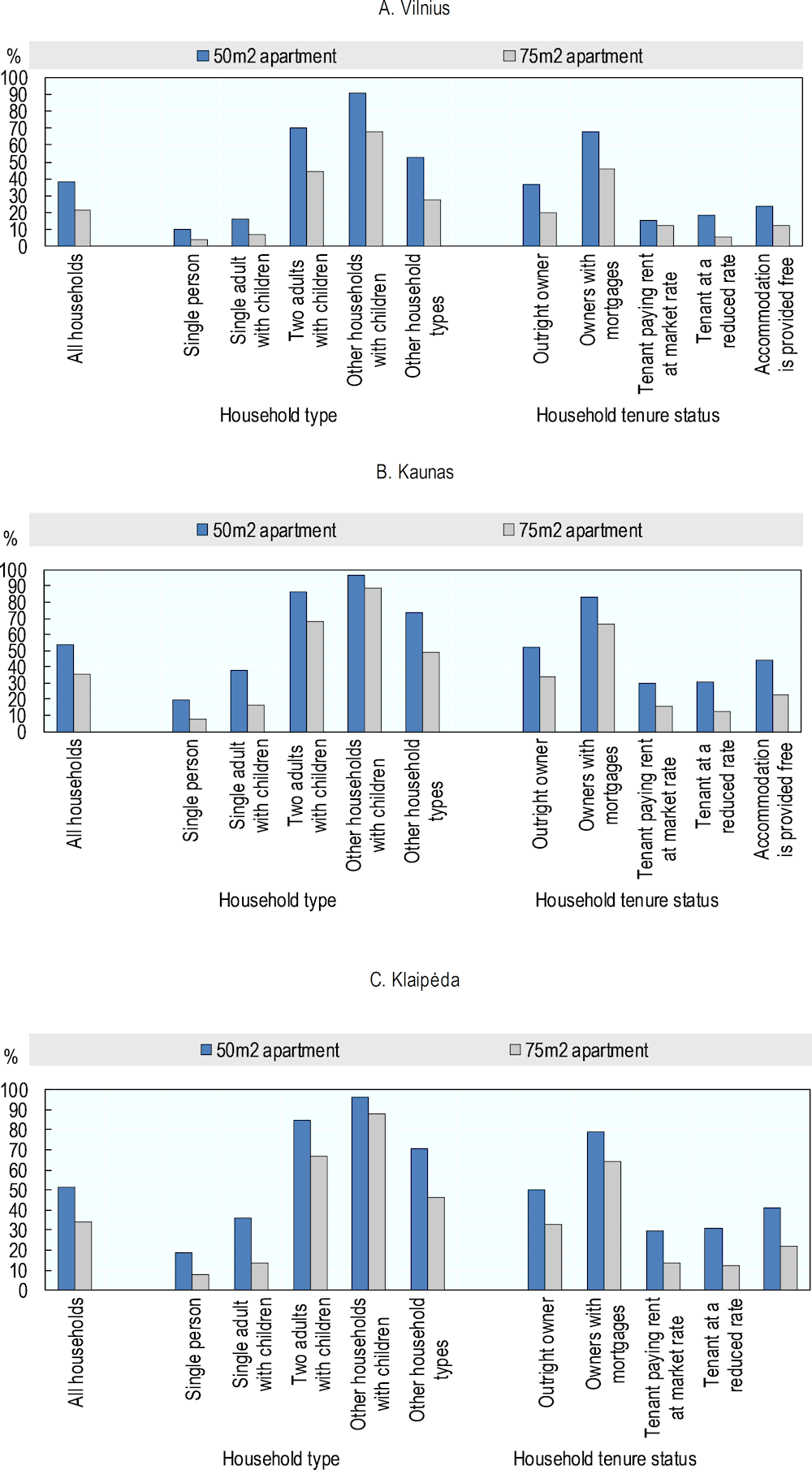

Many Lithuanian households are credit-constrained and struggle to afford a mortgage to purchase a home. An OECD simulation, drawing on available data from the pre‑COVID period, estimates the share of households that are able to afford a mortgage for a standard 50m2 and 75m2 flat in a multi‑apartment building in the three largest Lithuanian cities: Vilnius, Kaunas and Klaipėda.

The results of the simulation suggest that, prior to the COVID‑19 pandemic, only around 40% of households earned a sufficient income to reasonably afford a mortgage to purchase a standard 50m2 flat in Vilnius; “reasonably afford a mortgage” is defined here as spending no more than 30% of total after-transfer household disposable income on total housing costs (including utilities and maintenance). The share is estimated to drop to around one‑quarter of households who could reasonably afford a mortgage for a standard 75m2 flat in Vilnius. Note that an OECD simulation in Latvia – a country with a similar housing market profile and historical development – found comparable results, whereby only around 43% of households could reasonably afford the mortgage for an existing flat in Riga in 2019 (OECD, 2020[17]).

Compared to Vilnius, the situation is slightly better in Kaunas and Klaipėda, where around 60% of households would be able to reasonably afford a mortgage to buy a 50m2 flat, and 40% of households could reasonably afford a mortgage to purchase a 75m2 flat (see Annex Figure 2.A.1, Panels A, B and C in the Annex). The Annex provides further discussion on the method and assumptions for the simulation, as well as estimated results disaggregated by household type, tenure, and current housing situation (e.g. quality). A parallel simulation finds that most households would also struggle to reasonably afford renting a flat in the capital city, given household income levels and average rent prices (Annex Figure 2.A.2 in the Annex).

The simulation results in Lithuania are likely to significantly underestimate the housing affordability challenge in 2022, given their reliance on pre‑COVID data. This is because of the considerable increase in real house prices since the onset of the pandemic (Section 2.3.1), much higher mortgage interest rates, the ongoing cost-of-living crisis linked to strong inflationary pressures, which together have significantly decreased the purchasing power of Lithuanian households in the housing market.

The combination of low affordability of mortgages and the limited access to the private rental market presents an obstacle to residential mobility. According to OECD (2021[18]) estimates, Lithuania has the lowest share of households that changed residence between 2008 and 2012 (Figure 2.8). Limited housing mobility can have adverse consequences on households’ well-being and economic performance (OECD, 2021[18]). It represents an obstacle for households in search for better opportunities, such as jobs in higher paying regions or neighbourhoods with access to better schools.

Figure 2.8. Residential mobility in Lithuania is the lowest among OECD countries

Source: OECD Calculations based on 2012 EU SILC Data for EU countries, AHS for the United States, HILDA for Australia.

2.4. The environmental sustainability of the housing stock

Lithuania’s housing stock generates a large environmental footprint. Most housing is not energy efficient, and the residential sector accounts for over a quarter of total final energy consumption in Lithuania. Since 2005, the volume of GHG emissions generated by the residential sector has remained stable. Energy poverty is also a continued challenge among many low- and middle‑income households – a concern that is exacerbated by the recent and continued rising energy prices. Trends towards increased urban sprawl and low urban density result in longer commute times and increased reliance on individual motorised transport, with detrimental environmental impacts. While energy efficiency improvements in the housing sector remain a government priority, progress has been slow.

2.4.1. High energy consumption of the housing sector

Most housing is not energy efficient

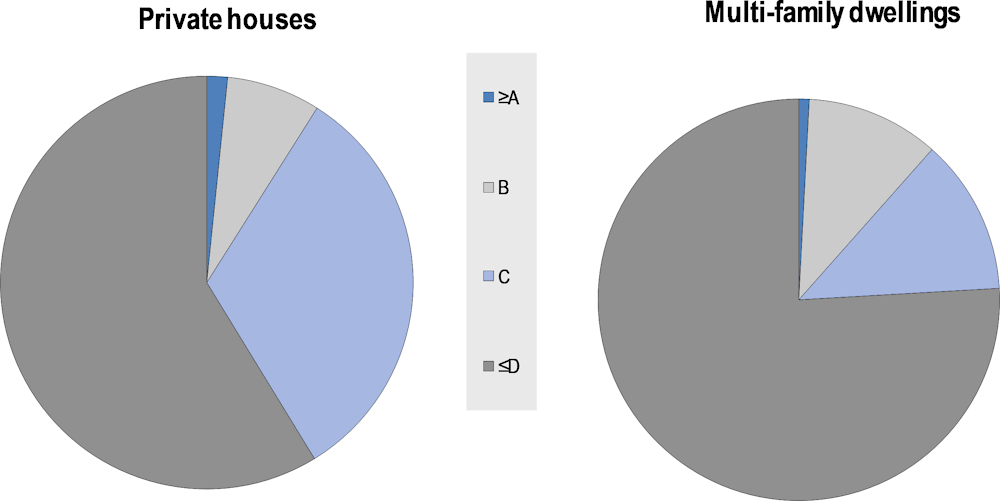

The majority of the housing stock is not considered to be energy efficient, due in large part to poor insulation. Around three‑quarters of multi-family dwellings, and nearly 60% of single‑family homes, have been attributed a “D” or lower grade in terms of energy efficiency, while less than 2% have received a grade of “A” or higher (Figure 2.9) (Government of the Republic of Lithuania, 2021[7]). Indeed, around 90% of multi-family dwellings were built before 1993 and are energy inefficient, consuming around twice as much energy relative to multi-family buildings constructed after 1993 (Aukščiausioji Audito Institucija, 2020[19]). In addition to contributing to increased levels of energy consumption and greenhouse gas emissions, the prevalence of these dwellings is also a driver of energy poverty, particularly among lower-income households (discussed further below). Relatedly, only a quarter of the total building stock is connected to district heating and less than half of all multi-family buildings, which can help to lower costs for consumers and reduce overall carbon emissions, relative to individual heating systems (Government of the Republic of Lithuania, 2021[7]).

Figure 2.9. Housing quality remains a persistent challenge, measured in terms of access to basic amenities as well as energy performance

Note: The energy performance class ranges from ≤D to A++, with A++ representing the highest class of energy performance.

Source: (Government of the Republic of Lithuania, 2021[7]), Long-term Renovation Strategy of Lithuania, https://ec.europa.eu/energy/sites/default/files/lt_2020_ltrs_en.pdf.

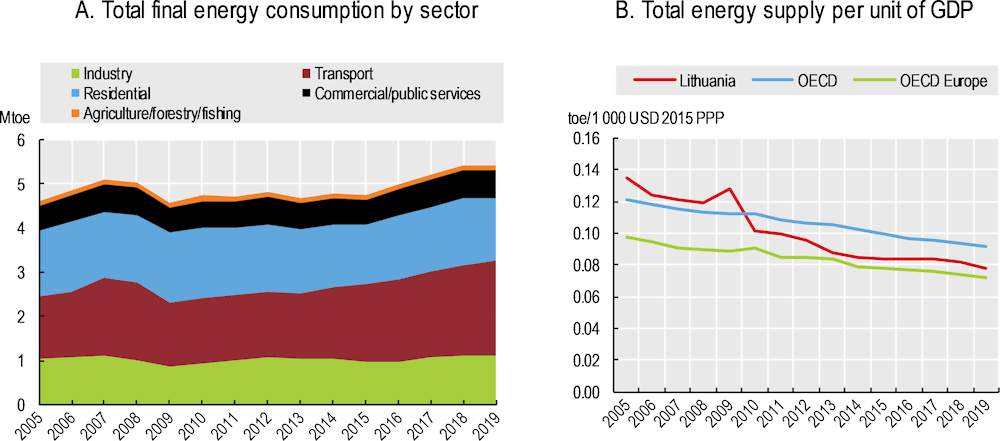

The residential sector is the second-biggest consumer of energy, behind transport

Overall, final energy consumption in Lithuania has increased in recent decades, rising by nearly 19% between 2005 and 2018, as consumption levels declined on average in EU countries (European Commission and European Investment Bank, 2020[20]). In 2019, the residential sector accounted for around 26% of total final energy consumption, second only to transport (Figure 2.10 – Panel A) (OECD, 2021[21]). However, the share of energy consumption within the residential sector has declined since 2005, from around one‑third to one‑quarter of total final energy consumption, even as the overall final energy consumption of all sectors increased. Meanwhile, the volume of GHG emissions generated by the residential sector has remained relatively stable since 2005 (Figure 2.10 – Panel B) (OECD, 2021[21]). This is in contrast to the rise in emissions from transport (primarily road transport), which represents the biggest and fastest-growing source of emissions.

There is an important environmental nexus between housing and transport. Residential development in Lithuania has largely taken place in the periphery of major cities, and even Lithuania’s capital city of Vilnius records one of the lowest population densities among the country’s large cities (OECD, 2021[21]). Over the past two decades, most development has occurred in low-density patterns at the outskirts of urban areas (Blöchliger and Tusz, 2020[9]). The trend towards urban sprawl implies longer commuting times and greater reliance on individual motorised transport – both of which contribute to increased energy consumption and GHG emissions. Such development patterns can also contribute to reduced housing supply (given the lower volume of housing developed in a given area) and higher housing prices (Blöchliger and Tusz, 2020[9]). The government has been strengthening its efforts in recent years to promote more compact urban development, notably through its latest Comprehensive Plan for the Territory of Lithuania. Indeed, greater co‑ordination between transport policies and land use planning could help lower infrastructure costs, reduce urban sprawl and bolster environmental performance.

Figure 2.10. The residential sector represents the second-largest consumer of energy, and the sector’s contribution to GHG emissions has remained stable since 2005

Note: Panel A. Data in the left panel exclude non-energy use consumption.

Source: (OECD, 2021[21]), OECD Environmental Performance Reviews: Lithuania 2021, https://doi.org/10.1787/48d82b17-en.

2.4.2. Deepening energy poverty

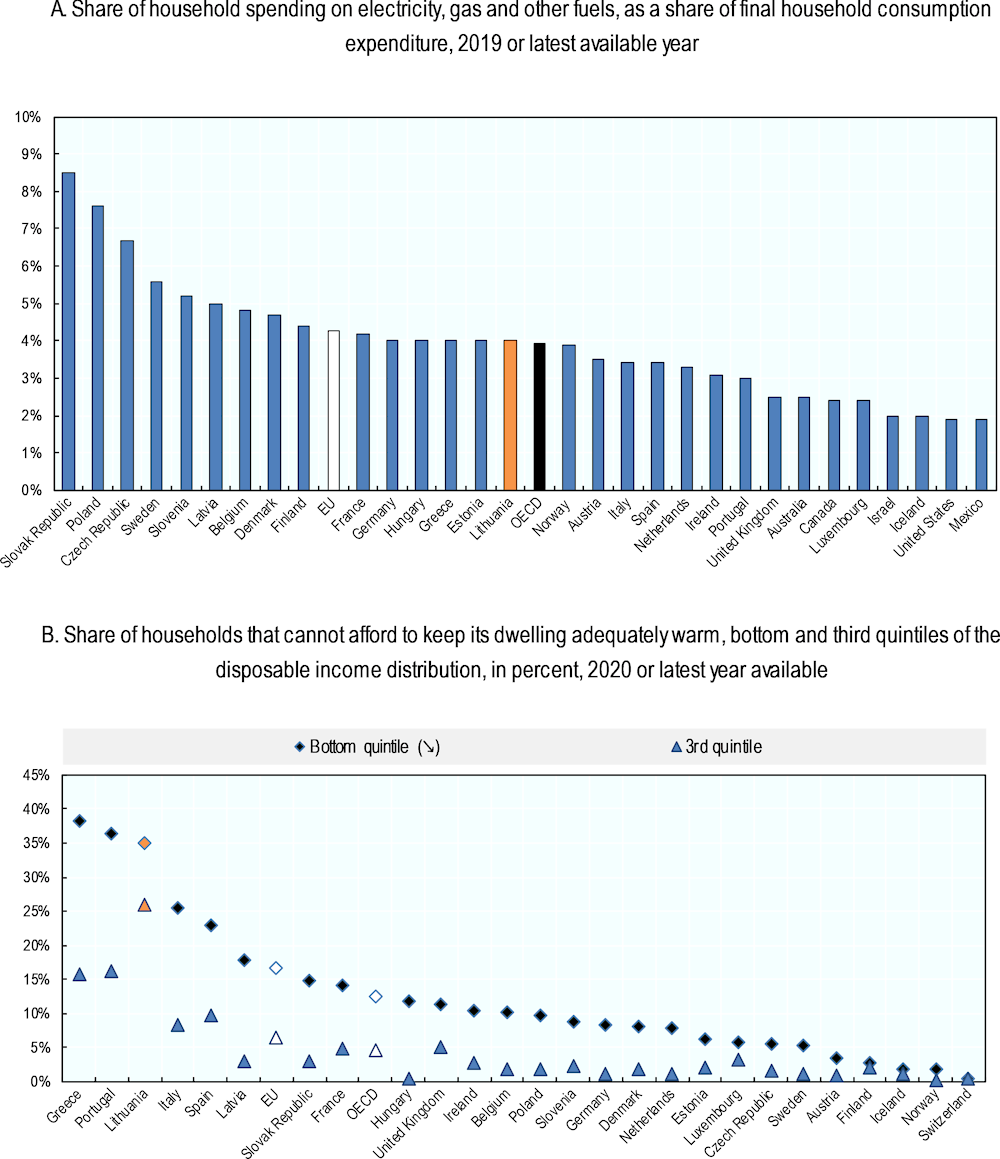

Household spending on energy is above the OECD average, and energy poverty remains a significant concern in Lithuania, as many households struggle to keep their dwelling warm. On average, Lithuanian households spend around 4% of their total final household consumption expenditure on electricity, gas and other fuels, just above the OECD average (Figure 2.11, Panel A). Among OECD countries, Lithuania has among the largest share of households in both the bottom and third quintiles that cannot afford to keep their dwellings adequately warm (Figure 2.11, Panel B). In 2020, around 35% of Lithuanian households in the bottom quintile of the income distribution and around 26% of households in the third quintile suffered from energy poverty – nearly three times the OECD average for households in the bottom quintile, and nearly six times the OECD average for households in the third quintile (OECD, 2022[3]).

Energy poverty should remain at the forefront of policy makers’ concerns, in light of the rapid rise in energy prices in recent years. Electricity prices (including taxes) rose by nearly 60% between the first half of 2008 and the first half of 2021 – much higher than the EU average of 37% over this period (Eurostat, 2021[22]). Recent months suggest even faster growth in energy prices: in September 2022, Lithuania recorded the fourth-highest annual growth rate in energy prices, at 75%, behind Türkiye (146%), the Netherlands (114%) and Estonia (78%) (OECD, 2022[23]).

Figure 2.11. Lithuanian households register above‑average spending on energy, and many households cannot afford to keep their dwelling warm

Note: Panel A. For Norway: 2018 data, because of 2019 data unavailability. Panel B. Data for Germany and Italy refer to 2019, for Iceland and the United Kingdom to 2018. No data available for Australia, Canada, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Israel, Japan, Korea, Mexico, New Zealand, Türkiye and the United States due to data limitations.

Source: (OECD, 2022[3]), Affordable Housing Database – OECD, indicator HC1.3, http://www.oecd.org/social/affordable-housing-database.htm.

2.4.3. Energy efficiency upgrades as a policy priority

As discussed in Chapter 3, energy efficiency improvements have been a government priority in recent decades, though the pace of residential renovations has been uneven. A number of programmes have been undertaken, including the Demonstration Project on Housing Energy Saving (1996‑2003); the renovation of multi‑apartment buildings, financed under the Operational Programme of 2007‑13; and the Programme for the Renovation of Multi‑apartment Buildings (2013‑20). Between 2013 and 2020, around 9% of the multi-family building stock was renovated, with an average of roughly 340 renovations completed annually, and a peak of 769 multi-family buildings completed in 2016 (Government of the Republic of Lithuania, 2021[7]).

Boosting the energy efficiency of the housing stock remains at the top of the agenda of the current Lithuanian Government, with the 2021 Long-term Renovation Strategy identifying multi-family buildings as a top priority. On the one hand, the multiple ownership of multi-family buildings can complicate the renovation process, given the need for a large share of apartment owners to agree to the plans. On the other hand, the multi-family segment of the housing stock is structurally and architecturally similar, which should facilitate repetitive large‑scale renovation projects (Government of the Republic of Lithuania, 2021[7]).

2.5. A challenging policy context, and implications of demographic and urbanisation trends on the housing market

Strong inflationary pressures – driven by increases in food and energy prices – are creating additional barriers to housing affordability, and the fast rise in construction costs make it harder to build affordable housing. Moreover, population decline, ageing and changing household composition towards smaller and more numerous households have the potential to affect future housing demand. Population is concentrated in three main urban areas, and even in a context an overall shrinking population, there is sustained migration from rural to urban areas, which has largely benefited Lithuania’s biggest cities. Lithuania’s population is expected to continue to decline in the coming decades. This suggests a potential growing demand for housing adapted for smaller households, particularly in urban areas, including dwellings that are accessible and adapted to the needs of an ageing population (see Plouin et al. (2021[24]) for further discussion).

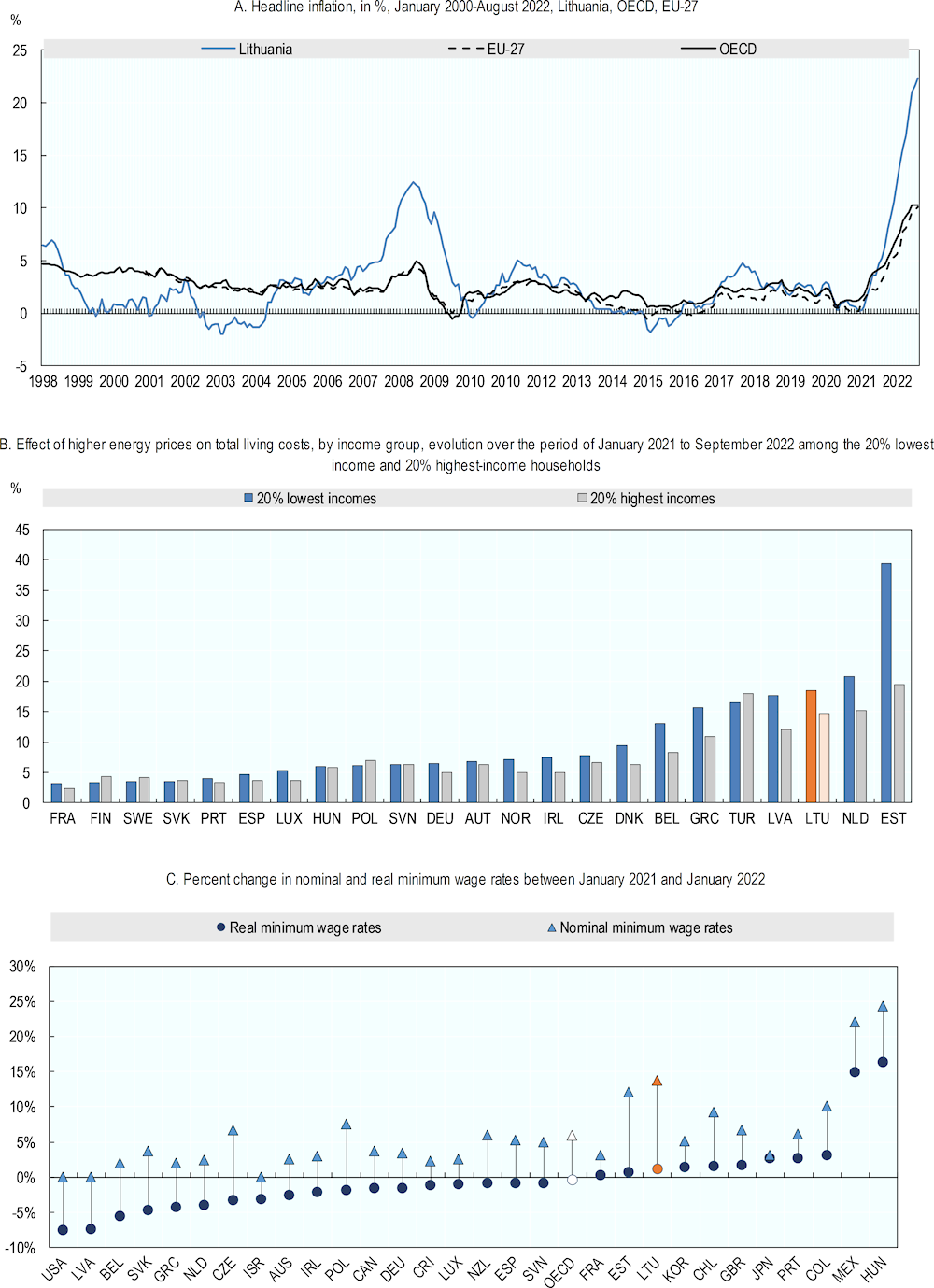

2.5.1. Strong inflationary pressures and rising construction costs create a challenging context for housing affordability

Headline inflation in Lithuania was already high and has surged in recent months to reach 22.4% in August 2022 (Figure 2.12, Panel A) (OECD, 2022[25]). Rising energy prices are one factor driving inflation; their impact on inflation is especially strong in Lithuania, due to the high energy intensity of the economy and a very large share of oil and gas in the energy mix (OECD, 2022[26]). They also have a disproportionate impact on poorer households in Lithuania. Indeed, between January 2021 and September 2022, the bottom 20% of the income distribution were more impacted by the effect of higher energy prices on total living costs than the top 20% (Figure 2.12, Panel B) (Bulman and Blake, 2022[27]). The significant surge in energy prices since the second half of 2021 has generated increased demand for the heating cost subsidy and provided even further momentum to improve the energy efficiency of the residential sector. In Lithuania, as in many OECD countries, nominal wages have not kept pace with increasing prices, leading to a fall in real wages (Figure 2.12, Panel C). As a result, household purchasing power has declined, on average, in Lithuania.

Figure 2.12. Headline inflation, driven by higher energy and food prices, has surged, taking a bigger toll on low-income households

Notes: Panel B: Data computed from Eurostat. 2015 consumption data are adjusted with the 2016‑22 evolution of items’ weights in the Harmonised Consumption Price Index. Panel C: OECD is an unweighted average of the countries shown above. The nominal minimum wage rates effective as of 1 January 2022 are used. Year-on-year inflation rates at the end of January 2022 are used to yield the real minimum wage rates. For Spain, the figure reflects minimum wage rates set in February 2022, which came into effect retroactively from 1 January 2022. For Costa Rica, the unweighted average of four daily minimum wage rates differentiated by skill level is used. For Mexico, the unweighted average of minimum wage rates in the Zona Libre de la Frontera Norte and those in the rest of the country is used. For Australia and New Zealand, year-on-year inflation rates in the first quarter 2022 are used.

Source: Panel A: (OECD, 2022[23]), “Inflation (CPI)”, https://doi.org/10.1787/eee82e6e-en. Panel B: (Bulman and Blake, 2022[27]), “Surging energy prices are hitting everyone, but which households are more exposed? – ECOSCOPE”, https://oecdecoscope.blog/2022/05/10/surging-energy-prices-are-hitting-everyone-but-which-households-are-more-exposed/, calculations updated by the OECD Economics Department. Panel C: (OECD, 2022[28]), OECD Employment Outlook 2022: Building Back More Inclusive Labour Markets, https://doi.org/10.1787/1bb305a6-en.

Meanwhile, since the second half of 2021, construction costs for residential buildings began to increase dramatically, with a year-on-year increase of 19% in September 2022 – more than double the growth between September 2020 and September 2021 (Lithuania Statistical Office, 2022[29]). Growth in construction costs was largely due to the rising costs of construction materials, as well as raising labour costs in the construction sector. Skill shortages in the construction sector have contributed to a near-doubling of wage growth to 14% in the course of 2022 (OECD, 2022[26]).

2.5.2. An ageing, shrinking population

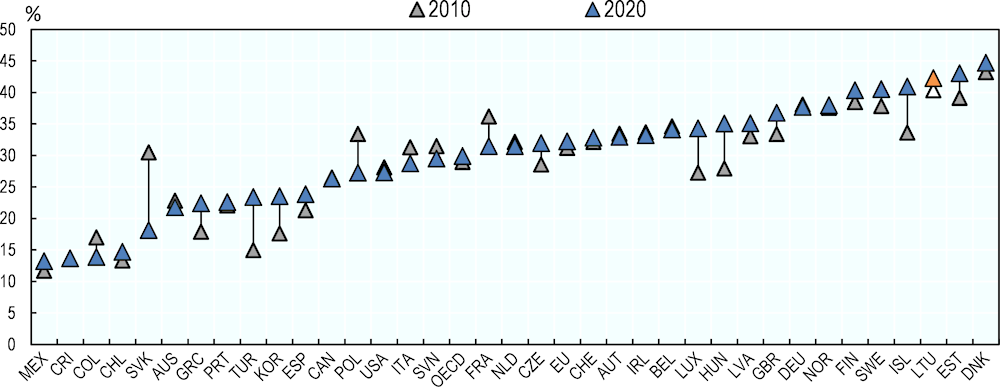

The population of Lithuania has declined by around 1% annually over the past two decades, from around 3.5 million people in 2000 to less than 2.8 million in 2021 (OECD, 2023[30]). Lithuania’s population is ageing, and young people make up a smaller, and declining share of the population. With 20% of the population aged 65 or over, Lithuania ranks in the top half of OECD countries in terms of the share of seniors as a percent of the total population, compared to an OECD average of 17.6% (OECD, 2023[31]). Youth (aged 15‑24) comprise less than 10% of Lithuania’s total population, below the OECD average of around 12%. These demographic trends have implications in the housing market. There are many more seniors in Lithuania who live alone, relative to their peers in OECD countries: over 42% of people aged 65 and over live in single‑person households – the third-largest share in the OECD, and an increase since 2010 (Figure 2.13) (OECD, 2022[3]).

Looking forward, the population is projected to continue to decline by around 8% over the next 10 years, with the biggest drops among children (aged 0 to 9 years old) and young adults (aged 25 to 34 years old). By contrast, the number of seniors aged 65 and older is projected to grow, including by over 25% among 70‑ to 74‑year‑olds (OECD, 2023[31]).

Figure 2.13. More than four in ten seniors in Lithuania live alone

Note: Data not available for 2010 and 2020 in some countries; therefore, alternate years were used. For 2010: Chile (2011), Türkiye (2011); for 2020: Italy (2019), Germany (2019), Iceland (2018), Lithuania (2019). No data available for Japan, and New Zealand due to data limitations. Only private households are considered.

Source: (OECD, 2022[3]), Affordable Housing Database – OECD, indicator HM1.4, http://www.oecd.org/social/affordable-housing-database.htm.

2.5.3. High regional disparities and continued migration to cities

Lithuania records among the highest levels of regional disparities in the OECD, with high rates of home ownership dampening labour mobility. Over 60% of the population lives in the three counties that are home to the largest cities: Vilnius, the capital region (30% of the total population), Kaunas (20%) and Klaipėda (12%). No other county records more than 10% of the national population (OECD, 2023[32]). The biggest Lithuanian cities record GDP per capita, household income and productivity levels near the OECD average, while smaller, rural areas continue to lag behind; the main drivers of these disparities include low economic growth and job creation in lagging regions, and insufficient labour mobility – due in part to high home ownership rates and a shallow rental market – towards areas of greater economic strength (Blöchliger and Tusz, 2020[9]).

Over the past two decades, there has been moderate yet consistent growth of people migrating to more urbanised areas, at the expense of rural areas. Between 2001 and 2020, the population dropped significantly (by more than 25 points, according to the Population Index) in all Lithuanian counties except Vilnius, Kaunas and Klaipėda (OECD, 2023[32]). Meanwhile, the net inter-regional mobility rate in Vilnius and Kaunas has been consistently positive since 2002. At the same time, the population of seniors 65 and over has increased in nearly all Lithuanian counties since 2001, with the biggest growth (over 25 points between 2001 and 2020) in Vilnius and Klaipėda (OECD, 2023[32]). The challenges resulting from Russia’s unprovoked war of aggression against Ukraine have increased pressures on the housing market and Lithuania’s current public support schemes (see Box 2.1 and Chapter 3).

2.5.4. Smaller and more numerous households

In addition, there is a trend towards smaller and more numerous households, as marriage and fertility rates decline, the median age for a first marriage increases and divorce rates increase (OECD, 2021[33]). Average household size shrunk from 2.5 people per household in 2005 to 2.2 in 2020, which is broadly in line with the EU average (Eurostat, 2021[34]). Similar to many OECD countries, the fertility rate in Lithuania has steadily declined over the past half-century, from 2.4 in 1960 to 1.6 in 2020 (OECD, 2021[33]). Meanwhile, the total number of households increased by around 18% between 2006 and 2021, well above the Euro Area average of 11% over this period (Eurostat, 2021[35]).

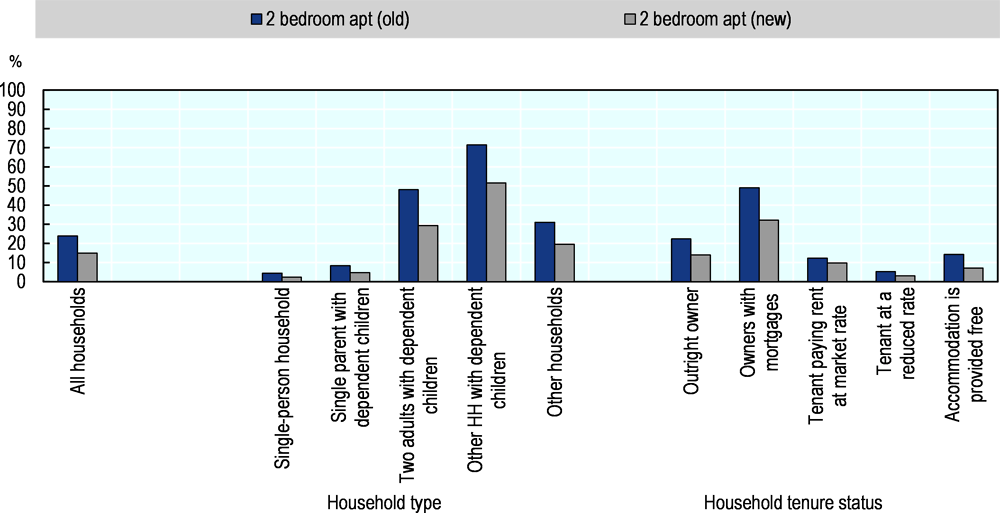

In parallel, the composition of households has been evolving. Single adults without children are the most dominant household type in Lithuania, representing 45% of all households in 2021, compared to an EU‑27 average of 36%; single adults without children have also recorded the biggest growth since 2005 (99%). The number of couples without children, which make up 17% of all households, has increased by 25% since 2006. Households with dependent children (including both single‑ and dual-parent households) make up around 23% of all Lithuanian households, just below the EU‑27 average of 24% (Eurostat, 2021[35]). Of these, couples with children, which represent 12% of all households, dropped by 4% between 2006 and 2021 (Eurostat, 2021[35]). Nearly a quarter of all Lithuanian households with children are single‑parent households – the fourth-highest rate in the EU. The share of single‑adult households with children among all households grew by 79% between 2006 and 2021 (Eurostat, 2021[35]). Further, single‑person households and single parents with dependent children were at the highest risk of poverty, compared to other household types in 2020. As demonstrated in Annex Figure 2.A.1 and Annex Figure 2.A.4 in the Annex, compared to other types of households, these two household types are least likely to be able to reasonably afford to a mortgage to buy a flat in the three biggest cities, or to rent an average flat in Vilnius.

References

[19] Aukščiausioji Audito Institucija (2020), Valstybinio Audito Ataskaita: Daugiabučių Namų Atnaujinimas (Modernizavimas).

[9] Blöchliger, H. and R. Tusz (2020), “Regional development in Lithuania: A tale of two economies”, OECD Economics Department Working Papers, No. 1650, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/5d6e3010-en.

[27] Bulman, T. and H. Blake (2022), Surging energy prices are hitting everyone, but which households are more exposed? – ECOSCOPE, https://oecdecoscope.blog/2022/05/10/surging-energy-prices-are-hitting-everyone-but-which-households-are-more-exposed/ (accessed on 26 April 2023).

[8] Causa, O. and J. Pichelmann (2020), “Should I stay or should I go? Housing and residential mobility across OECD countries”, OECD Economics Department Working Papers, No. 1626, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/d91329c2-en.

[10] Council of Europe Development Bank (CEB) (2019), Feasibility Study for a Social and Affordable Housing Programme in Lithuania.

[20] European Commission and European Investment Bank (2020), The potential for investment in energy efficiency through financial instruments in the European Union MS summaries, https://www.fi-compass.eu/sites/default/files/publications/The%20potential%20for%20investment%20in%20energy%20efficiency%20through%20financial%20instruments%20in%20the%20European%20Union_0.pdf (accessed on 26 April 2023).

[34] Eurostat (2021), Average household size, EU-SILC survey, https://appsso.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/nui/submitViewTableAction.do (accessed on 19 November 2021).

[35] Eurostat (2021), Number of private households by household composition, number of children and working status within households (1 000), Eurostat, https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/products-datasets/-/lfst_hhnhwhtc (accessed on 19 November 2021).

[22] Eurostat (2021), Statistics: Electricity prices for household consumers - bi-annual data, Eurostat Data Browser, https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/NRG_PC_204__custom_2023198/default/table?lang=en (accessed on 3 February 2022).

[4] French Presidency of the Council of the European Union (2022), Informal conference of EU Ministers responsible for Housing - Declaration of the Ministers, https://www.ecologie.gouv.fr/sites/default/files/08.03.2022_DeclarationNice.pdf.

[7] Government of the Republic of Lithuania (2021), Long-term Renovation Strategy of Lithuania, https://ec.europa.eu/energy/sites/default/files/lt_2020_ltrs_en.pdf (accessed on 3 September 2021).

[15] Lithuania Statistical Office (2022), Average annual prices of apartment rentals, Database of indicators - Official statistics portal, https://osp.stat.gov.lt/statistiniu-rodikliu-analize?indicator=S7R280#/ (accessed on 26 April 2023).

[14] Lithuania Statistical Office (2022), Average sales price of a dwelling, Database of indicators - Official statistics portal, https://osp.stat.gov.lt/statistiniu-rodikliu-analize?indicator=S7R280#/ (accessed on 26 April 2023).

[29] Lithuania Statistical Office (2022), Construction input price indices, Database of indicators - Official statistics portal, https://osp.stat.gov.lt/statistiniu-rodikliu-analize?indicator=S7R261#/ (accessed on 26 April 2023).

[16] Lithuania Statistical Office (2022), Number of dwellings completed, Database of indicators - Official statistics portal, https://osp.stat.gov.lt/statistiniu-rodikliu-analize?indicator=S8R717#/ (accessed on 26 April 2023).

[31] OECD (2023), Elderly population (indicator), OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/8d805ea1-en (accessed on 26 January 2023).

[30] OECD (2023), Historical population, https://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=HISTPOP# (accessed on 26 January 2023).

[12] OECD (2023), “Housing prices (indicator)”, OECD, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/63008438-en.

[32] OECD (2023), Regional demography, https://stats.oecd.org/BrandedView.aspx?oecd_bv_id=region-data-en&doi=a8f15243-en (accessed on 26 January 2023).

[3] OECD (2022), Affordable Housing Database, OECD, Paris, http://www.oecd.org/social/affordable-housing-database.htm.

[2] OECD (2022), “Housing support for Ukrainian refugees in receiving countries”, OECD Policy Responses on the Impacts of the War in Ukraine, https://doi.org/10.1787/9c2b4404-en (accessed on 26 April 2023).

[23] OECD (2022), “Inflation (CPI) (indicator)”, OECD, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/eee82e6e-en (accessed on 26 April 2023).

[25] OECD (2022), OECD Economic Outlook, Volume 2022 Issue 1, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/62d0ca31-en.

[26] OECD (2022), OECD Economic Outlook, Volume 2022 Issue 2, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/f6da2159-en.

[28] OECD (2022), OECD Employment Outlook 2022: Building Back More Inclusive Labour Markets, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/1bb305a6-en (accessed on 14 November 2022).

[13] OECD (2022), “Prices: Analytical house price indicators”, in Main Economic Indicators (database), OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/cbcc2905-en (accessed on 26 April 2023).

[18] OECD (2021), Brick by Brick: Building Better Housing Policies, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/b453b043-en.

[21] OECD (2021), OECD Environmental Performance Reviews: Lithuania 2021, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/48d82b17-en (accessed on 17 November 2021).

[33] OECD (2021), OECD Family Database, OECD, Paris, https://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=FAMILY (accessed on 4 December 2018).

[17] OECD (2020), Policy Actions for Affordable Housing in Latvia, OECD, Paris, https://issuu.com/oecd.publishing/docs/latvia_housing_report_web-1 (accessed on 2 July 2020).

[11] OECD et al. (2013), Handbook on Residential Property Prices Indices (RPPIs), https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/docserver/9789264197183-en.pdf?expires=1685113831&id=id&accname=ocid84004878&checksum=27C698390950AD3BB9F7CB4E858D1463 (accessed on 16 March 2020).

[24] Plouin, M. et al. (2021), “A crisis on the horizon: Ensuring affordable, accessible housing for people with disabilities”, OECD Social, Employment and Migration Working Papers, No. 261, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/306e6993-en.

[5] UNECE and Housing Europe (2021), #Housing2030: Effective policies for affordable housing in the UNECE region, United Nations Publication , New York, https://unece.org/sites/default/files/2021-10/Housing2030%20study_E_web.pdf (accessed on 16 May 2023).

[1] UNHCR (2023), Operational Data Portal: Situation Ukraine Refugee Situation, https://data.unhcr.org/en/situations/ukraine (accessed on 26 April 2023).

[6] Urban Agenda for the EU (2018), “The Housing Partnership Action Plan”, https://ec.europa.eu/futurium/en/system/files/ged/final_action_plan_euua_housing_partnership_december_2018_1.pdf (accessed on 16 May 2023).

Annex 2.A. Affordability simulations

The OECD conducted a simulation to estimate the approximate share of Lithuanian households who could reasonably afford a mortgage to purchase an existing flat of 50m2 and 75m2 in the three largest cities: Vilnius, Kaunas and Klaipėda.

The simulation draws on available data from the pre‑COVID period (2019), due to data availability constraints. However, it is important to note that the current situation is even more challenging, in light of the significant rise in real house prices, interest rates, construction costs and energy prices that render housing less affordable (and notably make the purchase of a home less affordable), within the context of broader inflationary pressures and a cost-of-living crisis. Accordingly, the results of this simulation are very likely to underestimate the share of households facing affordability challenges: higher house prices, higher interest rates and higher utilities costs all drive up the costs associated with purchasing housing.

Definitions and assumptions

The simulation relies on the following definitions and assumptions:

It is assumed that households that can “reasonably afford a mortgage” consume less than 30% of total after-transfer household disposable income on total housing costs (including utilities and maintenance); the 30% threshold is used as a measure of reasonable affordability (intentionally lower than the 40% threshold for housing cost overburden); see OECD (2022[3]) for further discussion on affordability metrics and their limits.

The average transaction price for a standard apartment in a multi-family building in 2019 draws on data from the Lithuania Statistical Office, equal to EUR 1 559/m2 in Vilnius; EUR 958/m2 in Kaunas and EUR 1017/m2 in Klaipėda.

Annual mortgage costs estimated on the basis of a 30‑year repayment mortgage with monthly payments. The interest rate is set at the 2019 average annual percentage rate of charge on loans to households (new business) for house purchase, as published by the Bank of Lithuania (2.04%). This rate is assumed to remain fixed throughout the lifetime of the mortgage.

Utilities and maintenance charges are assumed to cost EUR 1.57 m2 per month in Vilnius, Kaunas and Klaipėda.

A 0.37% notary registration fee is considered.

It is assumed that the household already has access to a deposit worth 15% of the transaction price.

The measure of disposable income is equivalised by household size. For the breakdown by household types, “children” are defined as household members aged 17 or less, or household members aged between 18 and 24 that are economically inactive and living with at least one parent. Household disposable incomes are OECD estimates based on information from the European Union Statistics on Income and Living Conditions (EU SILC) survey 2019.

Simulation results

Annex Figure 2.A.1 displays estimates of the share of households that could reasonably afford a mortgage in Vilnius (Panel A), Kaunas (Panel B) and Klaipėda (Panel C). In Vilnius, around 38% of households earned sufficient income to reasonably afford a mortgage to purchase a 50m2 flat, compared to 22% of households to purchase a 75m2 flat. In Kaunas and Klaipėda, around 50% of households could reasonably afford a mortgage to buy a 50m2 flat, and 35% for a 75m2 flat.

Disaggregating by household type, tenure, and current housing situation (e.g. quality):

Single adults and single parents are least likely to be able to reasonably afford a mortgage to purchase a home in all three cities.

Most outright owners are also highly likely to be credit constrained. This raises issues particularly for those families wishing to move to a better quality, bigger sized apartment or to a different region in search for better job opportunities (Annex Figure 2.A.1).

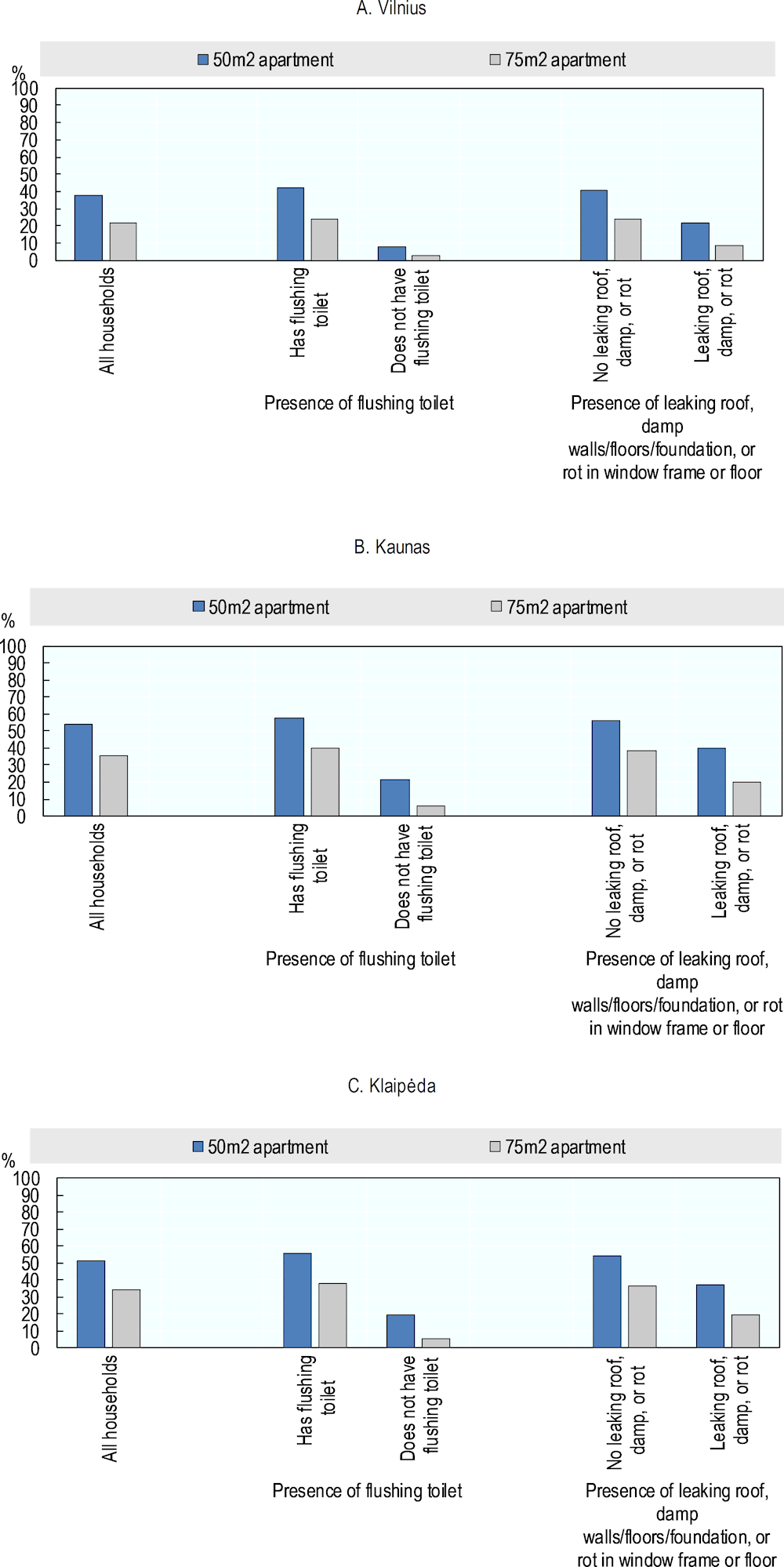

Households living in poor-quality homes (for instance, those lacking basic facilities, such as a flushing toilet, or facing significant quality issues, such as leaking roofs) are largely unable to reasonably afford a mortgage to purchase an apartment in Vilnius, Kaunas or Klaipėda. For example, only 8% of Lithuanian households living in dwellings lacking basic facilities such as flushing toilets can afford a 50m2 apartment in Vilnius, and only 20% can obtain a mortgage to purchase a similar apartment in Kaunas and Klaipėda (Annex Figure 2.A.2).

Young households (in which the oldest household member is under 35 years old) are least likely to be able to reasonably afford a mortgage in Vilnius (Annex Figure 2.A.3).

Further, the formal private rental market does not represent an affordable, viable alternative for many Lithuanian households. First, the formal private rental market is currently very small, with less than 3% of households currently renting their dwelling (Section 2.2.2). Second, OECD simulations find that most households also struggle to reasonably afford a flat in the capital city. For instance, only 22% of outright homeowners would be able to reasonably afford an existing two‑bedroom apartment in Vilnius at the market price, and only around 14% would be able to reasonably afford a newly built apartment (Annex Figure 2.A.4). Similar to the simulation for purchasing a flat, single‑person and single‑parent households would face the biggest challenges.

Annex Figure 2.A.1. Fewer than half of Lithuanian households could reasonably afford a mortgage to purchase a home without spending more than 30% of disposable income on housing costs

Note: “Reasonably afford a mortgage” means that total housing costs (including utilities and maintenance) would consume less than 30% of total after-transfer household disposable income. The 30% threshold is used here as a measure of reasonable affordability (intentionally lower than the 40% threshold for housing cost overburden). Estimates based on the average transaction price for apartments in Vilnius (EUR 1 559/m2), Kaunas (EUR 959/m2) and Klaipėda (EUR 1 017/m2). Annual mortgage costs estimated on the basis of a 30‑year repayment mortgage with monthly payments. The interest rate is set at the 2019 average annual percentage rate of charge on loans to households (new business) for house purchase, as published by the Bank of Lithuania (2.04%). This rate is assumed to remain fixed throughout the lifetime of the mortgage. Utilities and maintenance charges are assumed to cost EUR 1.57 m2 per month in Vilnius, Kaunas and Klaipėda. A 0.37% notary registration fee is considered. It is assumed that the household already has access to a deposit worth 15% of the transaction price. For the breakdown by household types, “children” are defined as household members aged 17 or less, or household members aged between 18 and 24 that are economically inactive and living with at least one parent. Household disposable incomes are OECD estimates based on information from the European Union Statistics on Income and Living Conditions (EU SILC) survey 2019. The measure of disposable income used is equivalised by household size.

Source: OECD estimates based on the European Union Statistics on Income and Living Conditions (EU SILC) survey, housing transaction data from Lithuania Statistical Office, 2021.

Annex Figure 2.A.2. Households with housing quality problems are much less likely to be able to reasonably afford a mortgage without spending more than 30% of their disposable income on housing costs

Note: “Could afford a mortgage” means that total housing costs (including utilities and maintenance) would consume less than 30% of total after-transfer household disposable income. The 30% threshold is used here as a measure of reasonable affordability (intentionally lower than the 40% threshold for housing cost overburden). Estimates based on the average transaction price for apartments in Vilnius (EUR 1 559/m2), Kaunas (EUR 959/m2) and Klaipėda (EUR 1 017/m2). Annual mortgage costs estimated on the basis of a 30‑year repayment mortgage with monthly payments. The interest rate is set at the 2019 average annual percentage rate of charge on loans to households (new business) for house purchase, as published by the Bank of Lithuania (2.04%). This rate is assumed to remain fixed throughout the lifetime of the mortgage. Utilities and maintenance charges are assumed to cost EUR 1.57 m2 per month in Vilnius, Kaunas and Klaipėda. A 0.37% notary registration fee is considered. It is assumed that the household already has access to a deposit worth 15% of the transaction price. The presence of a flushing toilet and the presence of leaking roof, damp walls/floors/foundation, or rot in window frame or floor are based on self-reported information by households. Household disposable incomes are OECD estimates based on information from the European Union Statistics on Income and Living Conditions (EU SILC) survey 2019.

Source: OECD estimates based on the European Union Statistics on Income and Living Conditions (EU SILC) survey, housing transaction data from Lithuania Statistical Office, 2021.

Annex Figure 2.A.3. Young households struggle more to reasonably afford a mortgage in Vilnius

Note: “Could reasonably afford a mortgage” means that total housing costs (including utilities and maintenance) would consume less than 30% of total after-transfer household disposable income. Estimates based on the average transaction price for apartments in Vilnius (EUR 1 559/m2). Annual mortgage costs estimated on the basis of a 30‑year repayment mortgage with monthly payments. The interest rate is set at the 2019 average annual percentage rate of charge on loans to households (new business) for house purchase, as published by the Bank of Lithuania (2.04%). This rate is assumed to remain fixed throughout the lifetime of the mortgage. Utilities and maintenance charges are assumed to cost EUR 1.57 m2 per month in Vilnius, Kaunas and Klaipėda. A 0.37% notary registration fee is considered. It is assumed that the household already has access to a deposit worth 15% of the transaction price. The reference person in the household is considered the oldest active person in the household. Household disposable incomes are OECD estimates based on information from the European Union Statistics on Income and Living Conditions (EU SILC) survey 2019.

Source: OECD estimates based on the European Union Statistics on Income and Living Conditions (EU SILC) survey, housing transaction data from Lithuania Statistical Office, 2021.

Annex Figure 2.A.4. Only half of Lithuanian households can afford to rent the average two‑bedroom apartment in Vilnius

Note: “Could afford a rent” means that total housing costs (including utilities and maintenance) would consume less than 30% of total after-transfer household disposable income. Estimates based on the average rent for apartments in Vilnius according to Ober-House Market Report for Baltic States, 2021 (EUR 300 per month for a standard two‑bedroom apartment and EUR 410 per month for a newly built one). Tenants are assumed to pay a deposit equal to two months of monthly rent. Utilities and maintenance charges are assumed to cost EUR 1.57 per m2 per month in Vilnius. Household disposable incomes are OECD estimates based on information from the European Union Statistics on Income and Living Conditions (EU SILC) survey 2019.

Source: OECD estimates based on the European Union Statistics on Income and Living Conditions (EU SILC) survey, housing rent data from Ober-House Market Report for Baltic States, 2021.

Note

← 1. In 2018, the State Tax Inspectorate estimated that one in five rented dwellings was undeclared; some non-government sources estimate that up to four out of five of rental dwellings are undeclared; see also (Blöchliger and Tusz, 2020[9]).