This chapter reviews local policies to increase employment participation in Amsterdam and policies to facilitate mobility on the labour market. Specific focus is given to the integration of groups in vulnerable labour market situations, such as young people neither in employment nor education or training (NEET), refugees and people with a migration background. The chapter puts Amsterdam’s labour market integration policies into national and international perspective. The chapter further reviews current skills-based matching initiatives that aim to integrate the unemployed and economically inactive into the labour market. It concludes by discussing adult learning policies that could support Amsterdam in defining a comprehensive and long-term local skills strategy.

Policy Options for Labour Market Challenges in Amsterdam and Other Dutch Cities

5. Local policies for job creation in Amsterdam

Abstract

In Brief

Integrated service approaches for labour market participation are important for groups and people in a vulnerable situation and with a low labour market attachment. In many cases, it is not sufficient to offer people a job as other barriers are an obstacle to employment. These barriers can be related to physical or mental health or to financial or social challenges. Integrated approaches allow municipal services to understand and address all barriers and circumstances. While an integrated approach is more resource-intense, it can nevertheless be cost effective if it increases the likelihood and durability of future employment. In Amsterdam, such integrated approaches are currently offered to youth and refugees (so-called “status holders”). Social welfare recipients with a low labour market attachment and those in need of active job coaching are supported through specific work experience places run by the municipality. This so-called AmsterdamWerkt! (“Amsterdam works”) programme aims to help people understand their interests, skills and increases the prospect of future gainful employment.

Amsterdam has a special responsibility to address labour market challenges for newly arrived migrants as well as people with a migration background. Amsterdam’s population is one of the most diverse in the Netherlands. In line with its legal responsibility, the municipality offers integrated services to recently arrived migrants. This includes language training, but also a skills-based approach to job-matching. While the ability to attract workers from inside and outside the European Union is a key strength of Amsterdam, a diverse population also brings challenges. Discrimination, including during the hiring process and on the job is frequently experienced by Dutch citizens with a non-Western migration background. Ongoing initiatives to increase the diversity in the municipality administration are promising, especially if combined with encouragement of similar practices by private sector employers.

Amsterdam, at the municipal as well as metropolitan level, has proactively supported initiatives for skills-based matching on the labour market. Amsterdam’s House of Skills has been instrumental in developing a taxonomy of skills that can be used by jobseekers to self-assess their skills and match with suitable vacancies. Such skills-based matching can overcome barriers to inter-sectoral labour mobility, is more inclusive towards people with low levels of formal education and can be a driver of adult learning. In Amsterdam, focus areas of skills-based matching have been the healthcare sector, construction and logistics.

While skills-based job matching has a number of advantages, it also brings new challenges. For instance, current skills-based recruitment in the health care sector often relies on job carving, i.e. the rearrangement of work tasks within a company to create tailor-made employment opportunities. Job carving can allow for a faster uptake of employment, limiting immediate training needs and allowing workers to work on tasks that correspond to their strengths and interests. However, without additional training offers, it also increases the risk of a lack of opportunities for career progression if workers remain highly specialised on specific tasks. A further key challenge for the upcoming years will be to ensure that local skills initiatives in Amsterdam harmonise their skills taxonomy with other skills initiatives across the Netherlands to further facilitate inter-sectoral and inter-regional job transitions.

Adult learning is supported by numerous national support measures and subsidies, but it needs further policy coherence to achieve results at the regional level. In the Netherlands, participation in adult learning is high but large differences in participation rates between groups persist. For instance, in the Netherlands only around 7% of the working population with less than secondary education report that they participated in continuous education and training over the past four weeks, compared to more than 20% among the medium educated and more than 30% among the highly educated. Structural barriers to adult learning remain in place for those with lower levels of education, those working for SMEs and the self-employed. Increasing adult learning is important for municipalities because it can help make workers more resilient to changing labour markets and facilitate successful mobility within and across firms, making spells of unemployment less likely. While financial incentives to engage in adult learning come from the national government, and national and sectoral organisations, municipalities and labour market regions can support adult learning by integrating it with place-specific economic transitions and increasing coordination with business representatives.

Introduction

This chapter reviews integration services and other forms of support that municipalities provide for the re-integration of people into the labour market. As reviewed in Chapter 4, municipalities are responsible for a diverse set of people that face difficulties to enter the labour market, including recently arrived refugees, welfare recipients with a distance to the labour market, and people with various disabilities that require social or physical support. While some overlap in the challenges and the strategies to address them exist, the diversity often demands flexibility by municipality case workers to acknowledge individual needs.

The first section provides a general overview of frequency of re-integration services to welfare recipients, with specific examples of programmes that exist for people with a larger distance to the labour market and youth that are not in employment, education or training (NEETs). The next section reviews the issue of integrating migrants and people with a migration background into the labour market. A further section reviews skills-based job matching initiatives. The final section reviews the topic of life-long learning and the role for Dutch municipalities in this policy area.

Supporting people to integrate in Amsterdam’s labour market

In the Netherlands, municipalities are responsible to provide means-tested benefits and provide support for the long-term unemployed, economically inactive and workers who can only work in sheltered jobs or through subsidised wages. In addition, asylum seekers who have been granted a status to remain in the Netherlands are the responsibility of municipalities. Following the allocation of asylum seekers across municipalities, municipalities are responsible for their integration in the labour market and society more broadly. Municipalities are given extensive autonomy on how to provide labour market integration support. This policy autonomy allows municipalities to vary their offer based on the differences in the (economic) characteristics of places and the people who require support. This provides an incentive for municipalities to apply efficient and effective policies that lead to labour market participation (see chapter 4).

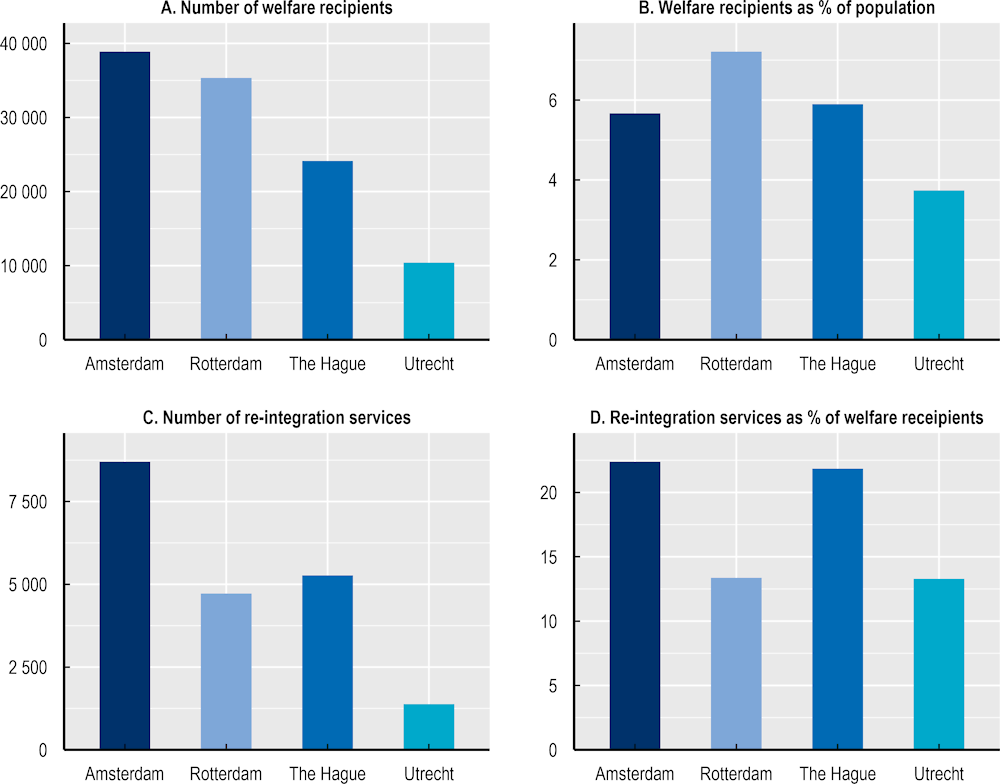

The number of welfare recipients and re-integration services vary across the Netherlands’ four largest cities

Each city has a different population of welfare recipients that are potentially eligible to receive employment activation services from their municipality. The largest absolute numbers of welfare recipients live in Amsterdam and Rotterdam, numbering over 35 000 in each. The Hague and Utrecht have much fewer cases (Figure 4.1, Panel A). While this difference is partly explained by differences in population size, it also reflects differences across cities with respect to the proportion of the population receiving welfare benefits (Figure 4.1, Panel B). Rotterdam has the highest relative share with over 7.2% of its population receiving welfare benefits, followed by The Hague with 5.9% and Amsterdam with 5.6%, and Utrecht at 3.7%. These differences can reflect various local economic characteristics, such as the sectoral composition (see Chapter 2), or differences in the characteristics of residents, such as the share of people with little formal education or a migration background.

Figure 5.1. Welfare recipiency rates and participation in re-integration measures vary across the Netherlands’ four largest cities

Note: “Welfare recipients” is the total number of people who are registered at the respective municipality to receive income support, excluding those above pension age. “Re-integration services” is the total count of active re-integration and participation services as reported by municipalities for January 2020, excluding the three services that show implausible large differences across municipalities, notably “Coaching towards work or participation”, “Other social activation”, and “voluntary work”. A resident may receive multiple services from their municipality.

Source: OECD calculations based on CBS tables 84510NED (Re-integratie-/participatievoorzieningen), 80794NED (Personen met een uitkering; regio) and 85230NED (Arbeidsdeelname; regionale indeling 2021).

The four cities appear to reach different shares of their residents on welfare with active support, but available data is unlikely to be sufficiently well harmonised. The total number of re-integration services also varies across the cities but can be set against the number of welfare recipients to obtain an indicator for the number of labour market re-integration and participation services that are provided by the municipality for each person receiving welfare.1 In Amsterdam and The Hague this amounts to around 22% of all social welfare recipients, while in Rotterdam and Utrecht it is around 13%. Since a resident may receive multiple services, the share of welfare recipients that are actively supported through re-integration services by the municipalities is potentially smaller.

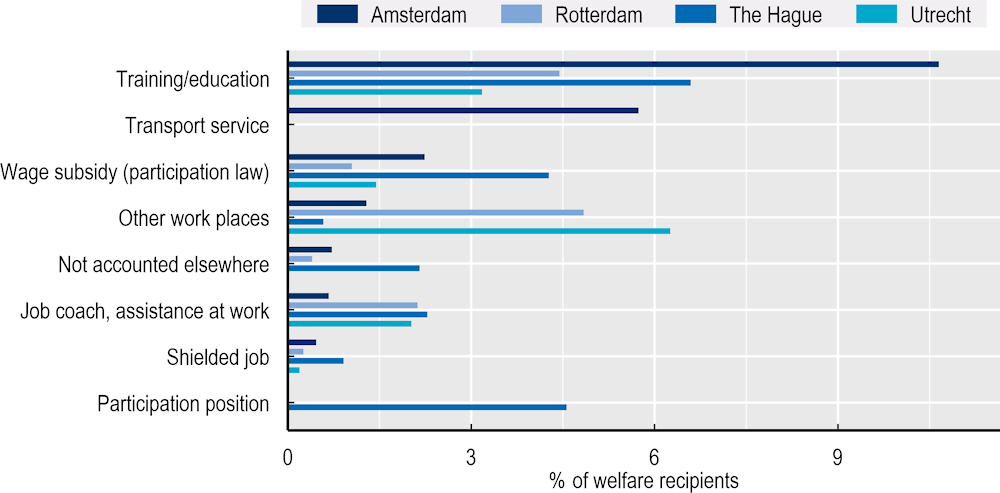

Municipalities also differ in the type of services they provide most frequently. Figure 4.2 splits up various re-integration services by type across the four cities. Amsterdam is relatively more active in offering training and education as part of its service provision. The category of transport services includes financial aid for public transport (e.g. public transport cards, or transport arrangements for people with a disability), which can be useful for residents needing to become more mobile within the city to find places of work. Other services, such as wage subsidies, job coaching and assistance at work are relatively more frequently used in the other cities. “Other work places” includes trial job placements. Trial job placements may be on a part-time basis such that it can be combined with additional schooling. Some welfare payments can be maintained during the training period until full-time employment is achieved. Available data shows that Rotterdam and Utrecht use such instruments relatively more frequently than Amsterdam.

More structural evaluation of provided re-integration services can help municipalities to learn which services are most effective for them, or how effectiveness can vary across places. A recent evaluation tested adjustments to services and obligations for welfare recipients in a randomised controlled setting across six municipalities, including Utrecht (de Boer et al., 2020[1]; Verlaat and Zulkarnain, 2022[2]) (see also chapter 4). The experiment looked at whether releasing recipients from obligations on the one hand or providing more intensive support on the other hand, affected the transition towards labour market participation. While results were largely inconclusive due to sample size and experimental design, the practice of structural experimentation and evaluation is a necessary part of policy making (OECD, 2004[3]; OECD, 2020[4]). Case study analysis also allows for insights on what makes various new initiatives successful and which conditions need to be satisfied (Andriessen et al., 2019[5]). In addition, new initiatives to increase labour market participation can have unexpected benefits, even if not resulting in immediate employment outcomes for all. Inviting participants to new initiatives can re-establish the relation between the municipality and the welfare recipient. It can also be a first step towards using required services that are effective. In the Netherlands, municipalities have the autonomy and responsibility to use the most effective re-integration services that suit the needs of their residents. Local factors potentially play a role, such that a specific service may work well in one city but not in another.

Figure 5.2. The Netherlands’ four largest cities use different instruments for re-integration

Note: All numbers relative to welfare recipients excluding those beyond pension age. Some instruments with very small numbers are excluded. “Coaching towards work or participation”, “Other social activation”, and “Voluntary work” are excluded because of implausibly large differences across municipalities. Counts are for active services in January 2020. Welfare recipients may use multiple instruments at any time, but this is not accounted for in this data.

Source: OECD calculations based on CBS tables 84510NED (Re-integratie-/participatievoorzieningen) and 80794NED (Personen met een uitkering; regio).

Local organisation and implementation of reintegration services in Amsterdam

In Amsterdam, the municipality organises its support for income and employment in one department. The department of work, participation and income (Werk, Participatie and Inkomen, WPI) covers all areas of re-integration in the labour market, income support and social assistance. Specific divisions concentrate on sub-groups that have distinct needs, such as youth or refugees. Dedicated case workers aim to regularly engage with other welfare recipients and probe them towards their interest and ability to participate in the labour market.

Case workers can offer a wide variety of services to people and help them to obtain employment. A newly created catalogue indicates more than 100 different instruments, programmes, courses and workshops that span across areas such as education and (language) training, work, participation, financial and entrepreneurship. Work programmes range from workshops on how to prepare for job interviews to trial placement and internships. Instruments are typically targeted to address one specific issue and eligibility requirements provide some assurance that the intended outcomes can be achieved. The catalogue is both an aid for case workers searching for the right instrument for their clients as well as clients themselves. However, enrolment in specific programmes or initiatives always needs to be in agreement with the case manager.

“Other workplaces” are instruments for municipal residents who require a specific training environment and more comprehensive tools to guide them into work. Such learning facilities can help residents understand their interests in specific occupations and skills. While provided by a municipality, “other workplaces” can be intended as an intermediate step until a suitable and durable job with a private employer is found. Moreover, “other workplaces” can help people gain experience with regular working hours, expand their social network and reconnect with the interest in working.

In Amsterdam, work experience places for people with a low attachment to the labour market are created under the AmsterdamWerkt! (“Amsterdam works”) programme. AmsterdamWerkt! is a programme funded by the municipality that offers services to citizens who are not able to find work, such as jobseekers with a mental or physical disability or those who have social problems that prevent them from working. AmsterdamWerkt! is a continuous learning programme that offers participants training, education, and certification. The target group are benefit recipients who are unable to earn one hundred percent of the minimum wage and who need support to find and retain suitable work. Young people with a criminal record, early school leavers and new Dutch citizens belong to the target group. Participants are closely supervised by a personal job coach and go through several stages. After an orientation phase, an in-house work experience programme is offered in which participants can gain experience and get basic qualifications. The next step is an external internship at one of the (public or private) partners of the municipality. The job coach monitors the progress of participants and helps them prepare for a regular job or a suitable education trajectory after the external internship.

Social work instruments, such as wage subsidies, are used to incentivise the employment of individuals with low productivity. Employers are incentivised to hire employees with a disability through several schemes. Workers who provide less value to a firm than can be supported by the minimum wage, can be hired through a wage subsidy scheme. The wage value of the individual is regularly evaluated by an independent party. The employer pays the wage value, while UWV covers the remaining share up to the minimum wage that the individual receives. Moreover, there is a no-risk policy for employers in which UWV covers the wages of a worker with a disability in case of illness or incapacity to work. Furthermore, employers may qualify for tax benefits by hiring workers in a vulnerable situation and have the possibility to receive compensation for adjustments to the workplace that might be needed. Lastly, there is the possibility of trial placement. If it benefits the employee, a trial period of up to two months can be arranged after which a contract of at least six months follows (Government of the Netherlands, 2022[6]).

Young people who are unemployed or economically inactive also constitute a target group for the municipality. The national government actively aims to decrease the number of early school leavers by funding programs at schools and municipalities that aim to ensure that young people finish their education with at least a qualification that allows them to enter the labour market for durable jobs (Government of the Netherlands, 2022[7]). Rates of youth who are not in employment, education or training (NEET) are low in the provinces of Noord Holland, Zuid Holland and Utrecht relative to other European regions (see chapter 2). However, some regions experienced a noticeable rise in NEET rates during the COVID-19 pandemic. For instance, in the province Noord Holland, the province in which Amsterdam is located, NEET rates increased from 3.9% to 5.6% between 2019 and 2021. Similarly, in Zuid Holland, in which The Hague and Rotterdam are located, NEET rates increased from 4.7% to 6.1% between 2019 and 2021. In Utrecht, the NEET rate rose from 3.4% to 4.5% over the same period.

In Amsterdam, youth who require assistance in labour market integration have access to a more integrated set of services relative to other residents. Youth helpdesks encourage young people, aged between 16 and 27, to find work or continue their education. The inclusion of under-18s in the programme allows to also work actively with schools and counter early-school leavers for those young people that can be expected to continue their formal education. Neighbourhood contact points, so-called “Youth points”, aid in establishing a connection to job coaches and identify cases early. Case workers can provide support and assistance to tackle a range of issues that can prevent young workers integrate durably into the labour market, including financial, health and psychological issues.

An enhanced integrated service provision for youth is trialled in various places and results are often encouraging. Box 4.1 provides policy examples from Estonia, France, Belgium and Finland. The reason that integrated approaches tend to be more effective is that early school leavers, or people that disengage from labour market integration services, often face various obstacles. These often relate to their domestic or financial situation or to health-related issues. Integrated service provision aims to address all issues that have led to economic inactivity. Assistance to youth also tends to be more persistent, such that the person is supported over an extended period. Attention is given to achieve a durable transition to working life rather than immediate employment (Newton et al., 2020[8]).

Box 5.1. Integrated services for inactive youth across the OECD

Integrated approaches to support youth who are not in employment, education or training (NEET) are trialled in various countries.

For example, in Estonia, the Youth Guarantee Support System implemented in 2018 is a tool for the municipalities to reach out to young people not in education, employment or training and support them to continue their education, integrate them into the labour market and contact public employment services (PES) or other institutions. Young workers can draw on resources from local municipalities, schools, the Estonian PES agency and other partners that work with young people in order to find the best solution for each person (Kõiv, 2018[9]).

France’s 1 jeune 1 solution initiative addresses COVID‑19-related challenges in the labour market and targets youth living in disadvantaged neighbourhoods. Jeune 1 is a comprehensive package of ALMPs to address individual obstacles, involving recruitment support, apprenticeships, employment incentives and training. In 2020, the PES of Belgium (Brussels) introduced its employment support programme for young NEETs in partnership with private providers. The programme involves outreach activities, addressing individual employment obstacles, personalised guidance and follow-up support after a successful labour market integration (European Commission, 2021[10]).

Finland rolled out one‑stop-shops for young people involving a wide range of professionals in 2018 (Savolainen, 2018[11]). The key staff are youth and employment counsellors from PES and social workers from municipalities. Staff also includes psychologists, nurses, outreach workers and education counsellors. In 2021, the Finnish Government invested further into these youth centres, particularly aiming at boosting mental health services for the young and providing short-term psychotherapy (Ministry of Economic Affairs and Employment of Finland, 2020[12]).

Source: European Commission (2021[10]), “Flexible and creative partnerships for effective outreach strategies and targeted support to young NEETs”, https://ec.europa.eu/social/BlobServlet?docId=24058, OECD (2021[13]) “Building inclusive labour markets: Active labour market policies for the most vulnerable groups”, OECD Policy Responses to Coronavirus (COVID-19), https://doi.org/10.1787/607662d9-en. Kõiv (2018[9]) “Profile of effective NEET-youth support service”, Ministry of Economic Affairs and Employment of Finland (2020[12]) “Government spending limit discussion and supplementary budget support the processing of applications and multi-professional services”.

Social economy initiatives such as Amsterdam’s TechGrounds initiative further target disadvantaged people and neighbourhoods specifically. Amsterdam’s TechGrounds is an initiative that targets disadvantaged neighbourhoods by offering digital skills training through self and peer-learning in designated training centre (OECD, 2021[14]). TechGrounds’ main strength is a mentoring scheme that involves professionals from the tech industry. During modular courses, participants are matched with tech entrepreneurs who serve as project partners, increasing the chances of obtaining employment after completion. Training centres also offer co-working spaces, organise tech events and house start-up incubators.

Initiatives related to the development of a skills-based labour markets and strategies to counter shortages in sectors that need to support long-term transitions of regional economies often aim to draw young NEETs into the labour market. Various initiatives aim to break the barrier that the completion of formal degrees can represent for entering the labour market. Easy entrance into occupations that fit the interest of people who are not well integrated in the labour market can be helpful in their activation.

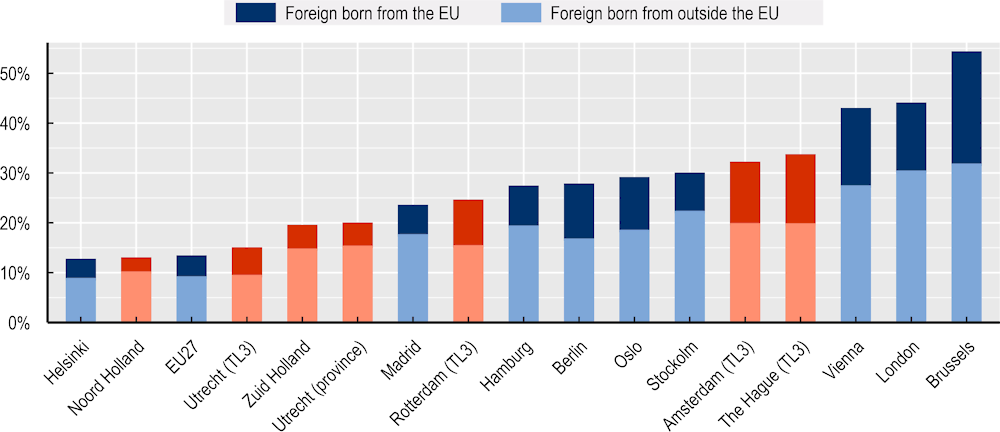

Migrants in Amsterdam’s labour market

The Netherlands has a diverse society that attracts labour migrants from around the world, while granting settlement status to asylum seekers from various international conflict zones. Many new arrivals are residents of the big four cities. In the municipality of Amsterdam, about half of residents have a migration background, which includes people born abroad, or with at least one parent who is born abroad (OECD, 2018[15]). The foreign-born population ranges from 12% to 20% in the provinces of Noord-Holland, Zuid-Holland and Utrecht, and from 15% to 33% in the TL3 regions of the G4 cities (Figure 4.3). In other European cities, such as in the TL2 regions of Stockholm, Vienna, London and Brussels, more than 20% of the population was born outside the EU.

Figure 5.3. The foreign-born population in some European regions exceeds that in Dutch cities

Note: Selected European cities refers to their respective NUTS2/TL2 regions, and EU27 is an unweighted average of all European Union regions for which data is available, population aged 15-64 years old. Dutch TL3 regions refer to population aged 15-65 years old.

Source: OECD Regions and Cities statistics, Database on Migrants in OECD Regions, OECD calculations based on CBS table 70648NED (Bevolking; geboorteland en regio).

In the Netherlands, a migration background of the first or second generation, rather than being born in a foreign country, is most commonly used as a demographic characteristic for the analysis of migrant integration. Moreover, rather than the distinction between EU and non-EU, a broader, Western and non-Western grouping is typically used, reflecting historical legacies. Box 4.2 provides further background on who is counted as a person with a migration background and how the differentiation is made between people with a Western and non-Western migration background.

Policies to integrate people with a migration background need to be targeted to specific needs of individuals. Recent new-arrivals, migrants who have spent a long period in the Netherlands and Dutch-born second-generation migrants share some of the same barriers to entering the labour market. These include discrimination by employers based on group-level characteristics and difficulties pertaining to the navigation of the destination countries’ culture while maintaining a connection to their own or their parents’ country of origin. However, specific groups such as refugees face additional distinct challenges on the labour market. These relate to linguistic and institutional barriers. Refugees also often require support related to housing and health. The remainder of this section therefore first discusses people with a migration background as a target group for municipalities more generally and then turns to refugees as a group with distinct needs.

Box 5.2. Terminology on persons with a migration background

The term “person with a migration background” encompasses a wide range of different people who may face different challenges and require different public and employment services. Generally, it captures anyone who is born outside the Netherlands, or who has at least one foreign-born parent. The term includes other EU nationals, migrants from other high-income countries such as non-EU OECD countries and foreign students in the higher education sector who decide to stay in the country. In the Netherlands, a substantial proportion of the migrant population are from Türkiye and Morocco who migrated in the reconstruction and development period following World War II. Other major groups of migrants originate from the Caribbean Islands, Suriname and Indonesia.

National statistics sometimes differentiate between people with a non-Western and we Western migration background. A non-Western migration background includes people with a background from countries in Asia (excluding Japan and Indonesia), Africa or Latin Amerika, as well as Türkiye. People with a Western migration background are those who are born or have at least one parent who is born in Europe (outside the Netherlands), North America, Oceania, Japan or Indonesia. In the future, the National Statistics Office, CBS, will change these categories to people with a European and non-European migration background. Statistics on migrants with a non-European migration background will then be disaggregated further into the largest countries of origin (Morocco, Türkiye, Caribbean Islands, Suriname and Indonesia).

Source: OECD (2018[15]), Working Together for Local Integration of Migrants and Refugees in Amsterdam, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264299726-en. CBS, (2022) “Nieuwe indeling bevolking naar herkomst”, Statistische Trends, 16 February 2022, https://www.cbs.nl/nl-nl/longread/statistische-trends/2022/nieuwe-indeling-bevolking-naar-herkomst

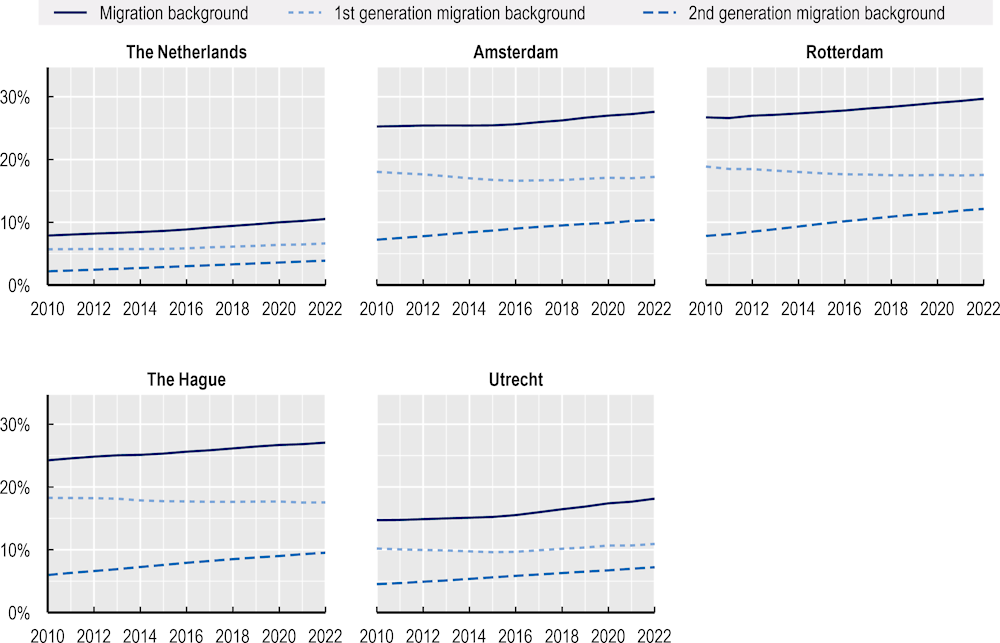

Reducing unemployment and economic inactivity among people with a migration background

The big four cities host a large share of people with a migration background which gives the cities a specific responsibility to address challenges to their labour market integration. In Amsterdam, Rotterdam and The Hague, people in the working-age population with a non-Western first- or second-generation migration background constitute close to 30% of the population in 2022 (Figure 4.4). In Utrecht, the share is approaching 20%. This compares to around 10% in the Netherlands as a whole. The share of people with a migration background has been growing since 2010, especially due to a growing share of people with a second-generation migration background. This increases the responsibility of city governments to address challenges to the labour market integration experiences by some migrants.

Figure 5.4. Up to 30% of residents in the big four cities have a non-Western migration background

Notes: Percentages based working age population (15 to 65 years). Non-Western as defined by CBS (see Box 5.2).

Source: OECD calculations based on CBS table 84910NED (Bevolking; migratieachtergrond en regio).

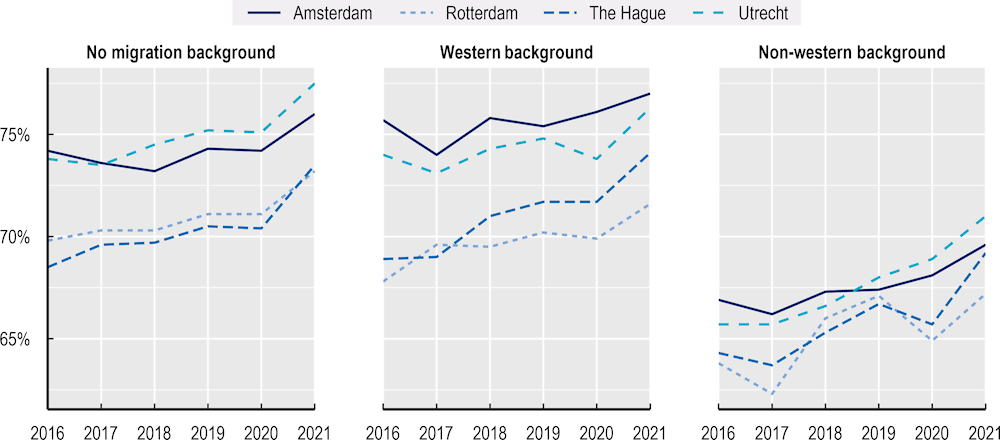

Figure 5.5. People with a non-Western migration background lag in their labour market participation rates across the Netherlands four largest cities

Note: Non-western as defined by CBS (see Box 5.2). CBS indicates that 2021 is a break in the series due to a change in survey methodology.

Source: CBS table 85230NED (Arbeidsdeelname; regionale indeling 2021).

On average, people with a migration background have obtained lower levels of education, are less likely to be employed and earn less than people that have no migration background. People with a (non-Western) migration background are twice as likely to be unemployed relative to people without a migration background. As documented in more detail in chapter 2, the unemployment rate in 2021 was around 8% for people with a non-Western migration background, compared to around 4% among people without a migration background. There are also group-level differences in economic activity. Among migrants with a non-Western migration background, the labour force participation in Amsterdam stood at 68.4% in 2021, compared to 76.5% among those without a migration background (Figure 5.5). While these participation rates have been increasing since 2016, in line with the improvement seen in the participation rates overall, the structural gap between people with and without a migration background remains.

Among newly arrived migrants, linguistic and institutional differences between the country of origin and the destination country pose barriers to employment. There are three main reasons why the pattern of a relatively worse labour market position of migrants compared to native-born is observed across the OECD: The lack of language skills, difficulties pertaining to the transferability of education across borders and the lack of host-country citizenship. Box 4.3 explains these in more detail.

Among the population of people with a migration background, discrimination may pose an additional barrier to employment. A study by the Netherlands Institute for Social Research (SCP) estimates that about half of the employment gap of people with a non-Western migration background cannot be attributed to observable characteristics, such as work experience, schooling, and age (Andriessen et al., 2020[16]). The unexplained difference in the employment rate, around four percentage points, may therefore be related to a form of discrimination. Survey responses from Amsterdam in 2020 and 2021 confirm that people with a Moroccan, Turkish or Suriname migration background are among the most discriminated people during the hiring procedure and at the workplace (OIS, 2021[17]). Over 50% of individuals from these groups who were rejected in a job application believe or suspect that discrimination was the reason for rejection. Overall, experience of discrimination did not change between 2019 and 2021, but the share of individuals who felt discriminated against during hiring procedures based on migration background or ethnicity increased from 37% to 47%. Additionally, one in five respondents with a Turkish migration background and one in four with a Moroccan migration background experience forms of discrimination at the workplace. Among these, four out of ten people survey respondents state to be subjected to offensive jokes, with lower pay for the same job and bullying also among the most commonly expressed discrimination experiences. People who work on temporary contracts through private employment agencies tend to experience discrimination more often than those on other types of contracts.

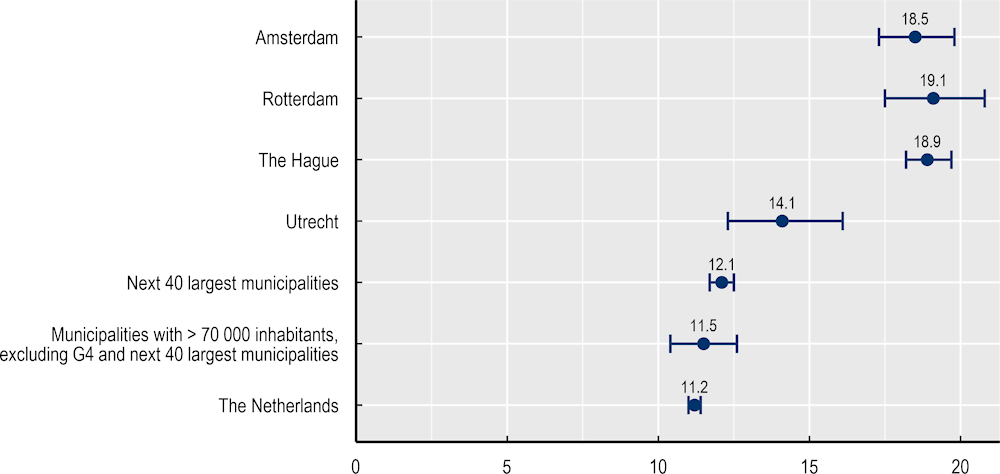

Feelings of discrimination are more commonly reported in the G4 cities relative to smaller cities and the national average. Figure 4.6 further shows that the incidence of self-reported discrimination is significantly higher in Amsterdam, Rotterdam and The Hague than in the rest of the Netherlands. To a large extent, these differences in self-reported discrimination can be explained by the distinctly more diverse populations in larger Dutch cities which host a relatively large share of people with a migration background. People with a migration background and those of non-white ethnicity are among those who experience discrimination most frequently in the Dutch society (Andriessen et al., 2020[16]). Discrimination based on migration background most often occurs during hiring procedures or on the job (Andriessen, 2017[18]).

Box 5.3. Why are employment rates among newly arriving migrants often lower than that of native born?

Three main reasons exist why migrants often show a lower labour market attachment, measured by labour force participation and employment rates. For each of these reasons, policy measures exist that can help the integration of migrants into the labour market.

The first reason is the limited transferability of formal education across borders. Foreign education and even the training for specific occupations may differ from country to country, partly due to country-specific job-skills requirements and partly due to the differences in the quality of those teaching job-related skills. Ludolph (2021[19]) shows that absent any support to get foreign degrees acknowledged, income differences between origin-country and destination-country degree holders can persist more than two decades after arrival, even for immigrants with the same level of education. A closely intertwined issue is the signalling value of foreign degrees: Employers are typically less familiar with education attained abroad and may therefore put a discount on foreign degrees when making hiring decisions, leading to discrimination. Policy efforts to acknowledge foreign degrees formally and offer retraining measures if degrees are below the national standard for the respective occupation can help migrants’ chances on the domestic labour market.

The second reason is the lack of language skills. A range of academic studies have shown that knowledge of the destination country’s official language is causally linked to higher labour force participation, employment and wages among immigrants. Offering language courses that allow migrants to take up jobs that require interactions in the destination country’s official language can therefore greatly benefit their labour market attachment. Latest evidence from a randomized evaluation in the United States shows that the increase in tax revenue due to higher earnings covers language training programme costs over time and generates a 6% annual return on the public investment (Heller and Slungaard Mumma, 2022[20]).

The third reason is the lack of citizenship. Not holding the nationality of the country a person resides in may have negative effects on their labour market attachment through a number of channels. Employment options in the public sector may be limited to citizens of the country, the weaker signalling values of foreign nationality may affect hiring decisions, discrimination among employers and – among some groups of migrants – certainty regarding the duration of stay may all play a role. Easing naturalization processes may therefore benefit the employment of migrants. Quasi-experimental evidence from France shows that naturalization has a positive effect on income and hours worked among immigrants (Govind, 2021[21]).

Sources: Govind (2021[21]), Is naturalization a passport for better labor market integration? Evidence from a quasi-experimental setting; Heller and Slungaard Mumma (2022[20]), Immigrant Integration in the United States: The Role of Adult English Language Training; Ludolph (2021[19]), The Value of Formal Host-Country Education for the Labour Market Position of Refugees: Evidence from Austria.

Figure 5.6. Addressing discrimination in society is a relatively pressing policy issue in the G4

Note: National online survey on approximately 55 000 respondents aged 15 years and older. “Next 40 large municipalities” refers to the average of the 40 largest municipalities by population after the Amsterdam, Rotterdam, The Hague and Utrecht.

Source: CBS table 85146NED (Sociale veiligheid; regio).

Preliminary evidence of ongoing pilot programmes indicates that young people with a migration background can be motivated and supported towards educational tracks and studies that provide better employment outcomes, while employers can effectively professionalise their hiring procedures to yield a more inclusive workforce. A set of pilot policies was initiated by the Ministry of Social Affairs and Employment to address aspects where people with a migration background experience worse employment outcomes than comparable groups (Ministry of Social Affairs and Employment, 2021[22]; Walz et al., 2021[23]). Pilots targeting youth who are still in education focused on motivating and supporting them in choosing educational tracks with better job prospects. Other pilots focused on employers with the aim to increase the professionalisation of hiring practices, increasing awareness of subconscious biases and appreciating the value of a more inclusive workforce.

The municipality of Amsterdam aims to counter labour market discrimination through running a more inclusive hiring strategy for its own organisation. For instance, one of the stated goals is to get a higher share of individuals with a non-Western migration background into higher management functions (Municipality of Amsterdam, 2020[24]). In addition, the municipality of Amsterdam intends to approach its own suppliers (such as caterers and providers of office supplies) and other SMEs in the city to consider hiring more inclusively.2 To lay out a more comprehensive strategy that tackles discrimination in the labour market, Amsterdam could consider looking into initiatives from other OECD cities as described in Box 4.4.

People with a migration background generally rely on the same municipal services that all residents have access to. One advantage of not distinguishing between migrants and non-migrants is that municipality case and social workers can use their experience and discretion to assess if cultural factors play a role in participation in the labour market. As discussed in the next section, a separate division in the department of work and income exists to manage labour market integration instruments targeted at refugees.

Box 5.4. Taking action against the discrimination of migrants on the labour market

Taking local action against discrimination can generally be done in four ways:

First, by active engagement with employers to tackle discrimination. Municipalities can run campaigns where they approach employers, challenge existing attitudes, and provide active support to drawing up diversity plans. For example, the commune of Saint-Dennis in the northern suburbs of Paris has started providing recruitment services and diversity training to local employers. In the Brussels Capital Region (Belgium), the public employment service offers similar services to hiring employers.

Second, local governments can cooperate with national governments to strengthen anti-discrimination legislation in hiring and ensuring its enforcement by identifying acts of discrimination. For example, to complement existing discrimination legislation, the city of Graz in Austria established a local anti-discrimination office that provides counselling on all issues related to discrimination and makes cases of bad hiring practice publicly known.

Third, by running public relations and social media campaigns that help dispel existing stereotypes and populist reporting on migrants. For example, the city of Erlangen in Germany designed a public relations and media strategy that aims to disseminate factual information about migrant groups in the city.

Finally, public sector employers can set an example by ensuring staff ethnic diversity and making their own diversity plans public for transparency and visibility. For example, the city of Berlin passed a binding regional law that forces it to diversify its public administration. Progress towards this goal is tracked by a range of statistical indicators.

Source: Froy and Pyne (2011[25]), “Ensuring Labour Market Success for Ethnic Minority and Immigrant Youth”, OECD Local Economic and Employment Development (LEED) Papers, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/5kg8g2l0547b-en; Moreno-Dodson et al. (2019[26]), Local inclusion of migrants and refugees.

Labour market integration policies targeting refugees

The Dutch central government is responsible for assessing asylum claims and allocating those that are allowed to stay across the Netherlands. If asylum claims are granted, individuals become “status holders”, meaning that they have the right to remain in the Netherlands and participate in the labour market as refugees with a temporary asylum residence permit. At that stage, municipalities become responsible to deliver income support and labour market integration services.

Amsterdam has a dedicated division in the department of work and income to address the needs of status holders. This department assesses the work capabilities, schooling credentials and personal circumstances. Based on an initial review, new arrivals are supported with their integration in the labour market. Municipality support to refugees includes housing, guaranteeing a subsistence income, language training and assistance in job seeking (OECD, 2018[15]). This integrated and relatively intense support is named the “Amsterdam approach”.

There were 7 299 status holders in Amsterdam on 1 January 2020, of which 6 256 arrived since 2015. Most refugees in Amsterdam fled the Syrian civil war (OIS, 2020[27]). 37% of status holders work, although this includes part-time employment. There is a strong gender difference with 45% of male and 19% of female status holders in employment. 62% of status holder are dependent on municipality welfare.

Recent arrivals generally show a great willingness to work, but language training and formal schooling may be required to achieve better labour market outcomes. Naturally, the willingness to work is a good foundation for labour market and social integration. In some cases, case workers suspect that the desire to work is related to debt incurred during the migratory journey, or the need to transfer money to family members elsewhere. Nevertheless, work can be an effective way to societal integration, and Dutch may be learned simultaneously. Amsterdam encourages younger arrivals, those aged below 30 years, to consider additional schooling.

Female refugees often require further support and encouragement to participate in the labour market. National-cultural backgrounds and caregiver duties may pose barriers to female refugees’ integration into the labour market. Case managers reported in interviews with the OECD that female refugees can sometimes be encouraged by the idea that they can reach financial independence.

Amsterdam has experimented with more intensive support for status holders. More intensive support is provided through dedicated case workers with fewer clients, such that more time can be dedicated to each person, allowing for better understanding of needs and circumstances.3 Job hunters start from the individual capabilities, rather than from the available vacancies. In general, the city finds that more intensive support is effective and cost-efficient because the additional resources required for the support decrease the dependency on welfare and healthcare costs. In one assessment, the benefit-to-cost ratio of more intensive services calculated to be 2.7 (LPBL, 2020[28]). Thus, each EUR 1 spend on additional support reduces other municipal cost by EUR 2.70. However, given the variety of backgrounds and needs of the population of status holders, such interventions may yield different results for different groups. For instance, in a randomised trial on providing support to Somali status-holders, who have some of the lowest paid-employment rates, the benefit-to-cost ratio was close to 1 (LPBL, 2021[29]). In this case, the status-holders who received additional support may have benefitted from the intervention, but the municipality had no financial benefit (or loss) from providing the additional assistance in terms of reduced welfare expenditures.4

The number of new arrivals from Ukraine rose rapidly in 2022 following Russia’s large-scale aggression against Ukraine. Ukrainian citizens were granted automatic settlement status upon registration with Dutch authorities. Municipalities, including in Amsterdam, prepared in anticipation of their arrival. Migrants from Ukraine have different characteristics than refugees who arrived from Syria, Afghanistan, Iraq and Somalia. Ukrainian migrants were mostly women, children and elderly. Integration efforts can consider their specific characteristics. For instance, the potential for labour market integration may be limited for women with childcare responsibilities. Some may have family or other social networks who were already in the country. Initially, the broader society expressed solidarity with Ukrainian refugees, for instance through offering places in private houses. While the war is continuing, refugee flows have decreased after the first few months of the war and some return migration is already observed. By July 2022, over 24 000 Ukraine refugees were working in the Netherlands.5

Special activation policies stimulate refugees to integrate and to find a job. Newcomers who meet certain criteria are expected to learn Dutch to a level that will enable them to build a life in the Netherlands and participate in society. Several pathways are laid out to support them in language learning and finding a job. Some municipalities have developed special programmes to integrate newcomers faster. The city of Utrecht for example, launched “Plan Einstein”. This programme is open to asylum seekers, refugees but also to other residents of Utrecht (Box 4.5).

Box 5.5. Refugee and asylum seeker reception: Plan Einstein

Integration and skills development of asylum seekers in the Netherlands is often slow because the procedure that determines if an asylum seeker is granted a status to remain in the country often takes several months and sometimes more than a year.

After the influx of many asylum seekers and refugees in 2015 and 2016, the city of Utrecht initiated a programme to improve reception and accelerate integration. The municipal government created a partnership with NGOs, social enterprises and educational institutions. The project housed asylum seekers and refugees in the same living facilities as local young people. Co-housing and co-learning where central to the project. Both asylum seekers and residents were invited to take part in the program.

Through co-housing and co-learning, “Plan Einstein” aimed to develop the social networks of asylum seekers with local residents, while also providing both groups to develop their skills, enhance wellbeing and improve social cohesion in the neighbourhood. Besides social activities and workshops, courses in English and entrepreneurship were offered to improve participants’ labour market chances, regardless of the country they would ultimately live in. The project aimed to engage with concerns from the receiving communities and activate asylum seekers from the moment of arrival. The project also addressed boredom, anxiety and worsening mental health during the waiting period of the administrative asylum procedure.

An evaluation found that Plan Einstein brought a solution to several challenges in asylum seeker reception. About half of the 558 refugees and asylum seekers who lived in asylum seekers centre between November 2016 and October 2018 took part in the project. About half of the participants took additional English courses and 18 people received the Cambridge certificate in English. The evaluation concludes that the main added value of Plan Einstein lies in the establishment of social contact. Refugees and asylum seekers were brought in to contact with each other, local residents, social organisations and local entrepreneurs. These contacts can be instrumental in further (labour market) integration.

Source: Oliver, C. Dekker, R. and Geuijen, K., (2019[30]). The Utrecht Refugee Launchpad Final Evaluation Report. University College London and COMPAS: University of Oxford.

Uncertainty regarding the duration of their stay in the host country affects refugees’ investments in into host-country specific skills and education. Acquiring host-country specific skills gives refugees access to quality employment. However, attaining formal education in the host country is time intensive and may not pay off for refugees who do not know if and when they want or need to return to their country of origin. Investment into host-country education is further discouraged if the acquired skills are not transferable back into the country of origin. Such uncertainty regarding the duration of stay is linked causally to work in low-skill employment among refugees (Cortes, 2004[31]). Local policymakers do not have the formal competence to increase the certainty of stay among refugees. However, they can support the labour market integration of refugees to avoid the clustering of migrants low-skill jobs.

To support refugees who face uncertainty of stay, the municipality of Amsterdam could offer modular courses in advanced ICT topics that develop skills easily transferable across border. Modular learning options that teach refugees advanced ICT skills are a promising policy tool that Amsterdam could deploy. Offering modular training in programming and coding responds to employers’ needs on Amsterdam’s local labour market, requires less of a time investment for refugees compared to formal degree-granting programmes and teaches skills that are transferable across borders. In modular course offers that do not lead to formal degrees, employer engagement becomes the decisive factor that facilitates access to the labour market. The ReDI School of digital integration, founded in 2016 in Berlin, has developed a successful business model that involves local ICT industry professionals as teachers (see Box 4.6). These teachers then support the transition into the industry after the completion of relevant courses that range from frontend web development to software specific training. Similar to Amsterdam’s TechGrounds initiative, Redi’s key strength is a mentoring scheme that involves professionals from the tech industry.

Box 5.6. Teaching refugees coding and programming: The ReDI School of digital integration

The ReDI School of digital integration is a non-profit organisation that teaches refugees coding and programming skills. It was founded in 2016 in response to the large inflow of asylum seekers into Germany when many Syrians fled their home country.

ReDI offers refugees a wide range of modular courses that develop advanced ICT skills. These include courses on frontend web development, data science, software development as well as more software specific courses on Salesforce or Azure. It caters some of its offers to female refugees specifically and thereby helps to overcome potential cultural barriers to female economic activity, for instance by offering childcare during the duration of courses. Women make up 60% of its course participants. Additional offers also include programmes for children aged 9 and above and youth aged 17 and above.

Seventy-five percent of those graduating from ReDI School’s Digital Career program, its core module, are in employment. Two key factors contribute to its success. First, ReDI works closely with ICT industry professionals who function both as volunteer teachers and mentors to refugees who participate in the courses. The role as teachers allows mentors to identify strengths in students and then recommend them to potential employers. Second, participation in ReDI’s modular courses does not require speaking the host country’s language. Courses are offered in English and interpreters are present if required.

After a successful start in Berlin, the ReDI School of digital integration expanded to several locations across Germany, Denmark and Sweden. It also offers remote study options.

Source: OECD Cogito (2022[32]) “It’s a Match: Reskilling refugees to meet Germany’s growing IT needs”, https://oecdcogito.blog/2022/02/07/its-a-match-reskilling-refugees-to-meet-germanys-growing-it-needs/.

Skills-based job matching in Amsterdam

In the Netherlands, there is a growing awareness of the importance to facilitate matches in the labour market based on skills (OECD, 2017[33]). Skills are thought of as the knowledge, attitude, abilities, and competences that are needed to carry out productive tasks. Macrotrends like automation and demographic developments are changing the character of work while there is already a shortage of qualified workers in crucial sectors like education and healthcare. Skills-based job matching acknowledges that labour market matching based on qualifications and diplomas may not make efficient use of available labour resources. Instead, a more precise and flexible match between demand and supply for work is needed. Initiatives on human capital, skills and learning exists across all levels of government, sectoral organisations and within individual firms.

Individual skills assessment can increase labour market participation and performance over a conventional assessment based on educational qualifications and job experiences. First, skills-based matching can be a gateway for people with few or no formal qualifications. Furthermore, approaching matching based on skills rather than qualifications can break barriers to cross-sectoral mobility for workers. Finally, a focus on skills and keeping these up-to-date and relevant is the basis of the vision of life-long learning. Through these mechanisms, it can benefit the individual, employers and ultimately public finances if it reduces welfare dependency on a macroeconomic scale.

A skills assessment allows people without formal education to be matched to jobs that can suit their capabilities. As people with low or no qualification tend to be much more vulnerable to job loss or extended unemployment spells, a changing narrative that de-emphasises formal qualification can be a helpful step towards better job matching. Some form of qualification can still be provided as part of a job search assistance programme towards durable employment, but such education can potentially be based on a modular programme rather than the conventional multi-year degree programmes. The same benefit may hold for recent migrants who may have some work experience or qualifications but for which the formal translation of degrees and diplomas to the Dutch labour market is challenging.

Since one can define skills much more holistically, a skills language helps overcome barriers to sectoral mobility. Over their career, workers may have gained work experience and qualifications for a specific sectoral occupation. Professional qualifications are often sector specific, which inhibits individuals to find opportunities in other sectors. This is specifically relevant if local labour markets experience a period where some sectors are declining while other growing sectors are struggling to find suitable workers. A skills language can allow people to demonstrate that they have the capability to work successfully in a different occupation or in a different sector because the required skills overlap.

Finally, the appreciation of skills fits well with a society that emphasises the importance of life-long learning. Skills include abilities and competences that individuals can attain through new learning and experiences. The continuous acquisition of new skills can help make workers more adaptable to the rapidly changing needs of labour markets. Rather than assuming that a new sectoral occupation implies a blank start, a jobseeker with their job coach can combine a skills-based assessment with learning programmes that build on existing knowledge and work experience of the individual.

There are, however, also important challenges in creating a skills-based labour market. First, there is the need for a common skills language among workers, employers, education providers and government services that support jobseekers. This common language is needed to recognise transferable skills and facilitate intersectoral job transitions. Moreover, challenges remain on how to assess, develop and validate personal skills. Finally, tools are needed to create a match between demand and supply on the basis of skills.

Several skills initiatives take on the challenges of a skills-based labour market. Recent assessments have identified over 40 different initiatives in the Netherlands, supported or initiated by the European Union, national ministries and regional governments. About half of these focus on skills assessments and skills-based job matching. About 25% focus on the validation of skills (SEO and ROA, 2022[34]). Additionally, there are municipal, regional and sectoral programmes to support workers in upskilling and reskilling. The Netherlands has a strong tradition of using formal qualifications for employability that is generally valued by employers and education provider. A skills-based system for the labour market requires a re-evaluation among all stakeholders in the assessment of peoples’ capabilities and the role of education and qualifications. Regional initiatives like House of Skills, Passport4Work, Talent in de Regio and SkillsInZicht (see Box 4.7) aim to facilitate this.

Box 5.7. Various regions in the Netherlands initiated skills-based matching tools

In the Netherlands, various regionally focused skills-based labour market matching initiatives have emerged in recent years. Each tend to enhance labour market opportunities for jobseekers through an online portal that can use jobseeker information on skills with available vacancies. Passport for work, Talent in de regio and SkillsInZicht are three of such initiatives.

Passport for work

Passport for Work is a public-private partnership that aims to facilitate skills-based matching in the south of the Netherlands, focusing on the region around the city of Eindhoven. It assesses skills through a gamified skills assessment method. The initiative is focused on individuals with a distance to the labour market and aims to develop a worker-specific skill passport that can be used within multiple sectors. To ease the use of the skills assessment, a minimum of text is used. Instead, role playing, and online games are used to assess skills and capabilities. Tailor made learning pathways help workers in developing their skills. Passport for work also aims to contribute to a common skills language.

Talent in de regio

Talent in de regio (“Talent in the region”) is a programme in which municipalities, employer and employee organisations and educational institutions work together to tackle challenges in the regional labour market in the north-east of the Netherlands. The initiative, funded by a national programme (Nationaal Programma Groningen), is focused on three provinces in the north of the Netherlands around the city of Groningen. The programme has three objectives: i), contributing to stable careers through better matching; ii) monitoring the type of workers in the region (“talent”) and evaluating policy interventions; iii) developing and sharing knowledge between workers, companies and educational institutions. Talent in the region develops a matching tool and promotes life-long learning.

SkillsInZicht

SkillsInZicht (“Skills in Sight”) presents itself as a tool to analyse, match and develop talent. SkillsInZicht is part of ArbeidsmarktInZich (“Labour market In Sight”), an initiative of six regions in the south of the Netherlands which aims to provide transparent labour market information to facilitate job changes and matching. SkillsInZicht gives jobseekers the possibility to find out which skills they possess by filling out questionnaires. A personal skill profile is developed based on the information provided. This profile can then be matched with vacancies, shared with employers or used as the starting point of (further) education.

Source: Lievens and Wilthagen (2022[35]), Skills-based matching with Passport for Work, Final Report; SkillsInZicht (2022[36]), https://skillsinzicht.nl/; Talent in de Regio (2022[37]), https://talentinderegio.com/.

House of Skills is the largest public-private cooperation in the region of Amsterdam that aims to promote a skills-oriented labour market. House of skills aims to work as a partnership between local governments, education institutions and the private sector. It takes on a coordination role in bringing different stakeholders in the metropolitan region Amsterdam together.6 Within the House of Skills network, municipalities, educational institutions and employers and employee organisations work together to promote the use of skills (Box 4.8). House of Skills has a focus on workers that are vulnerable to local job market fluctuations in the metropolitan region of Amsterdam. For instance, low-educated workers who work in sectors that face automation risks constitute a target group. Short-term unemployed workers and benefit recipients also fall in the scope of House of Skills. Like other skills initiatives, the work of House of Skills covers several policy areas. These include life-long learning, the activation of youth, the labour market integration of migrants and personal career assistance.

Box 5.8. House of Skills, a collaboration of regional stakeholder to stimulate skills-based labour market

House of Skills started as a public-private cooperation in the metropolitan area of Groot Amsterdam that promotes a skills-oriented labour market. The initiative created a community between local governments, employers and education providers to endorse skills as a new foundation of the labour market. It aims to improve the knowledge about skills, to validate skills and to match demand and supply on the basis of skills programmes. House of Skills received funding from EU DG Regio in framework for the response to COVID-19.

From skills profiles to jobs

House of Skills has developed several tools to assess, validate and use skills for matching. It has created a skills taxonomy based on the ESCOa and O*NETb skills classifications. Jobseekers can assess their own skills and obtain a skills passport through an online tool. The skills passport is based on a self-assessment of 60 questions to understand a person’s level of specific soft skills, practical tasks and preferred workstyles. Combining the skills passport with information on work experience and considering the stated interest of individuals to work in specific occupations, the platform offers suitable vacancies, trainings and occupations that fit their profile. Users can choose to make the profile visible to employers, who submit vacancies that are linked to required skills taxonomy. The matching between (self-assessed) skills, and jobs is developed by the public research institute TNO, private software developer Dit-Werkt and the Free University of Amsterdam.

Drawing people to a career in healthcare and other sectors

House of Skills has advocated for modular education programmes that are focused on acquiring specific skills, which are ideally targeted to sectors that experience large labour shortages, such as healthcare, logistics and construction. House of Skills is therefore experimenting with simulated working environments. For instance, to enable jobsseekers to gain experience in healthcare and find out if a career in this sector matches their skills and interests, a former hospital building is used to give them a real-life experience (Health Experience Centre Slotervaart). In collaboration with the regional education centre for vocational training (Regional opleidingscentrum, ROC), modular courses were developed to make entry into the sector easy for people who can build on existing skills and experiences.

Notes: a ESCO is the European Union standard classification of occupations.

b O*NET is a US based programme that provides information on tasks and skills that are associated with individual occupations.

Source: House of Skills (2022[38]) https://www.houseofskillsregioamsterdam.nl and stakeholder consultations.

While skill-based matching might bring solutions to a tight labour market, important challenges remain that limit adoption. First, various initiatives are not guaranteed to be compatible with each other. Second, employers need to be convinced that skills are an accurate representation of workers’ capabilities independent of conventional degrees and work experiences. Finally, despite the wide range of local skills initiatives, skills-based matching is not yet widely used, and its macroeconomic implications remain to be assessed.

A common national framework on the definition of skills is currently under development. Various initiatives on skills in the labour market, such as the House of Skills, developed their own classification of skills. While the general ideas among these initiatives are similar, there is no guarantee that they are compatible with each other. Similar to conventional diplomas and certificates, the assessment and recognition of workers’ skills will be more effective if there is a national or even international framework that allows for different but compatible initiatives. Having recognised the need for a harmonised skills language after regional initiatives have proved successful, UWV is developing CompetentNL. CompetentNL is intended to become a national framework for skills-based matching in the labour market (see Box 4.9).

Box 5.9. A common skill language: CompetentNL

CompetentNL is developed as the common skill language for the Netherlands. Over the past few years, the Dutch public employment services (UWV) have, together with SBB, an association for vocational training for the business sector, CBS, the national statistics agency and TNO, a research institute, worked towards a common skills ontology. This ontology is based on the taxonomy used by the Flemish public employment service (VDAB). The goal of CompetentNL is to combine the insights of different skill initiatives (like House of Skills and Passport4Work) and to create a language that can be used in all sectors and regions of the Dutch economy.

A detailed list of skills is linked to individual jobs and education programmes or modules. These skills are separated into two types: soft skills (e.g., teamwork, communication, organising) and tasks (e.g. programming, maintaining appliances, analysing data). The database of skills needs to be reasonably flexible to accommodate synonyms but also match similar tasks in different contexts.

The classification of skills is then connected to jobs and education programmes and presented in an online dashboard. This skills dashboard can help identify to what extent skills in upcoming and declining occupations overlap and which skills are needed for a transition. The platform can support client managers of UWV, municipalities and (private) employment agencies to identify jobs that fit with people’s skills and interests without being limited to individuals’ specific occupations and sectoral experiences.

Source: Sanders et al., (2022[39]), Skills als basis voor een nieuwe (re-) integratiepraktijk

Employers need to become more familiar with the potential that skills-based matching holds for them. For employers, the use of skills instead of formal qualifications creates initial uncertainty about the quality of a candidates (Ballafkih, Zinsmeister and Bay, 2022[40]). The currently tight labour market can help force employers to engage with this way of finding new potential employees because they are more likely to see candidates that have work experiences from unrelated sectors. The skills taxonomy then helps employers to recognise that people with different professional backgrounds can still present good matches for their vacancies.

A skills-based approach may also involve some adaptation at the workplace to fit the person to the job, for instance through job carving. Early experiences in Amsterdam suggest that job partitioning, or job carving, plays a role, especially for the integration of the least skilled into the labour market. Suitable tasks, potentially from multiple jobs, are combined to create a new job that fits the skills of the person. Job carving has been used by some public employment services agencies to facilitate the inclusion of people with disabilities in the workplace.7 While job carving holds potential in fitting a job to the individual, there is a risk that a worker ends up in a job that limits their progress because it is composed of only simple tasks. Therefore, in the process of job carving it remains essential to start from the potential of an individual’s ability to develop and learn new skills.

Adult learning and work-to-work transitions: What role for Amsterdam and Dutch municipalities?

Life-long learning facilitates labour market mobility by making workers more adaptable to changing circumstances. These circumstances may be specific to their employer, or related to megatrends, such as increased automation and digitalisation or the green transition that affect entire sectors or regional economies. Therefore, learning and skills policies can ameliorate the various transitions that individuals may face throughout their professional career, including the transition from education to work, from work to work, mobility across sectors, from unemployment to work and inactivity to work (OECD, 2019[41]). While skills and learning will make these transitions easier, the individual cases and circumstances also require a wide range of learning opportunities and facilities to suit individual requirements and needs.

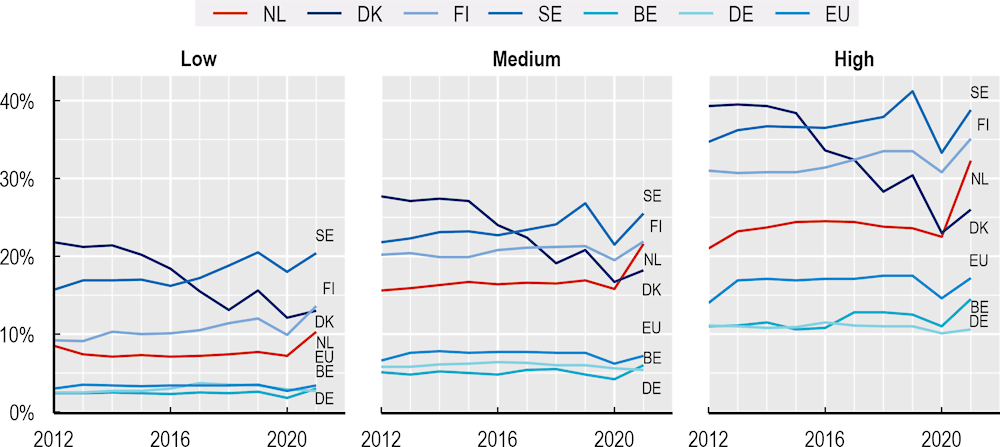

The number of adults who participate in continuous education and training has remained largely constant in the Netherlands, with significant differences in participation by educational attainment. In the Netherlands, around 7% of the working population with less than full secondary education was engaged in training over the past decade (see Figure 4.7). While above the European average of 2.7% and above neighbouring Belgium and Germany, the Netherlands structurally lags the Scandinavian countries of Denmark, Sweden and Finland. Across all countries it is evident that people with lower levels of education are on average less likely to participate in continuous education and training. Moreover, the trends for the Netherlands, the EU, Germany and Belgium are largely flat, especially for the two lower categories of education. In contrast, Sweden and Finland see increasing shares of adult training among the low-educated, while Denmark is noteworthy for its declining trend. The drop and subsequent uptick in adult learning participation in 2020 and 2021 in some OECD countries is likely due to the COVID-19 pandemic and may not reflect a structural shift. Besides educational attainment, younger workers are more likely to participate in training than older workers, as are those on permanent contract relative to own-account workers (OECD, 2019[41]). Research in the Netherlands has identified other constraining factors for adults. These include family responsibilities, which are disproportionately affecting women, the cost of training and foregone income (e.g. from unemployment benefits and reduced working hours), and the disengagement of older workers nearing retirement (SCP, 2019[43]).

The current policy landscape around life-long learning is under development to address various challenges. For instance, low-skilled workers that could benefit the most from learning and skills development are generally least engaged with it. Additionally, the breath of initiatives across ministries, social partners and regional governments risks missing internal coherence that allows to match individual needs with learning offers. Learning must also allow for additional mobility of workers, within organisations and across firms and sectors, and ideally within a local or regional context. Employer or sectoral specific learning may not always be sufficiently anchored in a framework that allows the transferability of skills and knowledge across employers and sectors (SCP, 2019[43]).

Figure 5.7. Adult learning among those with low levels of education does not increase

Note: Formal and non-formal education and training for people aged 25-74. Panels refer to ISCED11 levels, 0-2, 3-4 and 5-8 respectively. EU refers to the EU27 of 2020 (excluding the UK).

Source: OECD calculations based on Eurostat table trng_lfs_10 (Participation rate in education and training (last 4 weeks) by type, sex, age and educational attainment level).

The strategy of the Ministry of Social Affairs and Employment to increase policy coherence of existing and new life-long learning policies and initiatives is based on three pillars. The three pillars combine incentivising training of individual workers, incentivising employers and sectors to organise and engage with relevant training programmes, and to increase flexibility in publicly provided (vocational) education in order to become more accessible to professionals and adults (Ministry of Social Affairs and Employment, 2020[44]). The ministry proposes to support the three pillars with additional awareness raising policies to convince both workers and employers that continuous learning for all workers is essential.

The first pillar relates to increasing the workers’ capacity to engage with training and learning. A personal stipend to buy education services, recently introduced for jobseekers, may be expanded to all individuals as a life-long credit that can be used throughout the working life. In 2022, the national government reserved EUR 160 million for the so-called STAP budget (see also chapter 3). Workers can apply to this budget at UWV. They can receive a subsidy of up to EUR 1 000 that covers educational costs. The fund opens at specific dates several times a year. Recent experience shows that within a few hours of the opening day, the available funding is allocated, indicating that demand for support is much larger than the available funding.8

In addition, information and counselling will need to be provided as a government service to guide workers to the right training. A current pilot programme in Rotterdam and two other regions combines education with work such that people can be guided towards specific sectors in the region that need specifically skilled workers. Box 4.10 describes the case for the region in Rotterdam. UWV can also support registered unemployed jobseekers, including those that risk become long-term unemployed, with education programmes that are provided by regional education centres. In addition, an online platform is being developed that aims to provide a digital training and education portal and automated personalised advice based on a worker’s existing skills and experiences.9

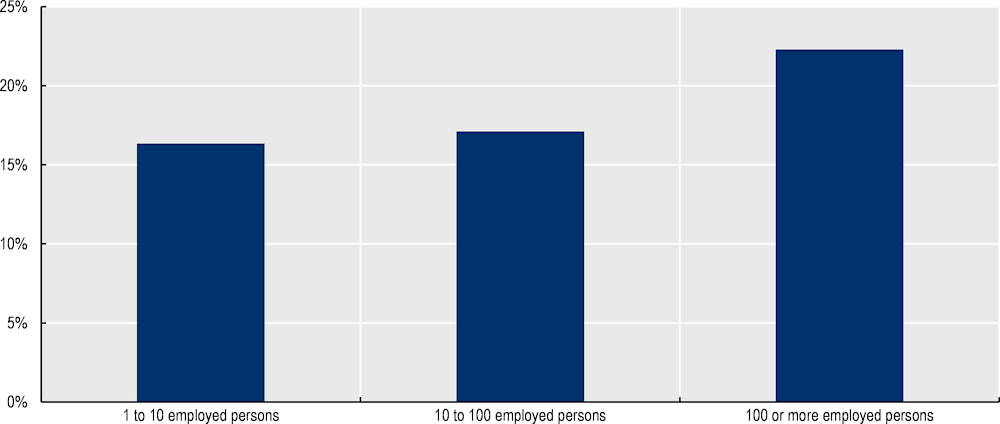

The second pillar of the ministry’s strategy for life-long learning focusses on the financial incentives for firms to support their workers enrolling in relevant courses. Specific instruments are available for SMEs in acknowledgement of the differences in learning offers across different firm sizes. For instance, in the Netherlands, workers employed by smaller companies are significantly less likely to participate in continuous education and training (see Figure 4.8). Some subsidy instruments are sector specific, in coordination with social partners. Subsidies are also available to create additional work experience places for people that require on the job training to facilitate their labour market participation.

Box 5.10. Rotterdam learn-work agreements to match people to vocational training and jobs for the future