Internal or within-firm mobility enables older workers to take up roles that are better suited for their evolving needs and to continue advancing at later stages of their careers. However, identifying opportunities to change roles internally are not clearly defined for older workers who are the least likely to reflect on their career goals and aspirations. Implicit or explicit ageist attitudes further undermine the fluidity in which older workers can make within-firm changes. This chapter explores employer-led policies that aid workers in closing information gaps and forming better job matches that are adapted to workers’ preferences, skills, and flexibility requirements.

Promoting Better Career Choices for Longer Working Lives

4. Harnessing internal mobility

Abstract

Key messages

Internal or within-firm mobility provides an avenue for workers to take up different roles that are better suited to their changing personal and business needs, thereby benefitting workers and employers alike.

However, the share of promotions declines with age, indicating that there may be fewer opportunities for career progression with age. Results from the 2022 AARP Global Employee Survey find that workers aged 55‑64 are 12 percentage points less likely to feel comfortable asking for a promotion than workers aged 35‑44.

According to the 2022 AARP Global Employer Survey, workers report that persistent age discrimination undermines career advancement through hiring discrimination (18%), fewer opportunities for promotion (11%), and denied access to training and personal development based on age (8%).

Many employers continue to hold stereotypical views of older workers, which in turn, influences their hiring and promotion decisions. In a 2023 Generation/OECD survey, 25% of hiring managers reported that they believe that workers aged 55‑64 are more reluctant to try new technologies or learn new skills (23%), and slower to adapt to new technology (22%).

It is in employers’ interest to confront negative stereotypes about older workers and put measures in place to tackle age discrimination at all stages of the recruitment and promotion processes (e.g. age‑blind hiring, semi-structured panel interviews, blind-hiring software).

Lack of internal professional development opportunities widens the skills gap between older and younger workers. It is crucial that employers encourage participation in training and convey its value to older workers who are less likely to participate.

Employers can draw on several policy levers to harness the advantages of internal mobility among older workers in their firms:

Job rotation and re‑deployment schemes help workers, particularly those with health-related issues or those in arduous occupations, to identify and transition into roles that better align with their skills and aspirations. Both policies proactively encourage a career change before working becomes unsustainable.

Mid-career reviews (MCRs) encourage workers to reflect on their career goals and identify mobility and training pathways to achieve these goals. Workers aged 55‑64 are 17 percentage points less likely to regularly review their career options compared to workers aged 35‑44 (37% vs. 53%).

Remote work can accommodate the flexibility needs of older workers, thus extending their working lives. Transitioning to a fully remote or hybrid role enables workers to balance work and outside commitments (e.g. care responsibilities, hobbies).

The gender gap in career and wage progression is largely concentrated within firms, therefore specific policies are needed to mitigate the consequences of motherhood for women. Flexible working conditions are particularly valuable to women and pay transparency tools such as equal pay audits can help close gender gaps.

4.1. Why is internal mobility important for older workers?

Internal mobility – when workers move between within the firm – can enable workers of all ages to take up roles that are better suited for their evolving circumstances, which in turn, improves firm retention. Within-firm changes can be upward moves, but they can also be horizontal moves to another part of the firm. Employers can draw on either of these transfers to address skills gaps at a lower financial and time cost compared to external recruitment processes. Given older workers’ considerable experience within the company, those who are hired internally require less training, which leads to productivity gains earlier on. Moreover, older workers’ experience contributes to intergenerational knowledge transfers that have been shown to improve firms’ success (Tavares, 2020[1]). As a result, firms dually benefit from retaining talent and improving productivity through better labour market matches.

While the literature clearly demonstrates the wage and job quality gains of within-firm transitions for younger workers, less attention is given to within-firm transitions for older workers. Evidence using linked employer-employee administrative data in Chapter 2 reveals that the share of promotions declines with age, indicating that there may be fewer opportunities for career progression as workers age. At the same time, within-firm wage growth represents the largest contributor to overall wage growth, especially for younger workers. The gap between the gains for older and younger workers highlights the importance of strategic employer-led interventions to generate internal mobility opportunities that lead to career advancement (not regression) for workers of all ages. This chapter explores employer-led policies which aim to increase fairness for older applicants and to cultivate high-quality internal mobility that promotes improved labour market matches and career.

4.2. How can employers address biases that limit internal mobility?

4.2.1. Overcoming negative stereotypes and tackling age discrimination in hiring and mobility

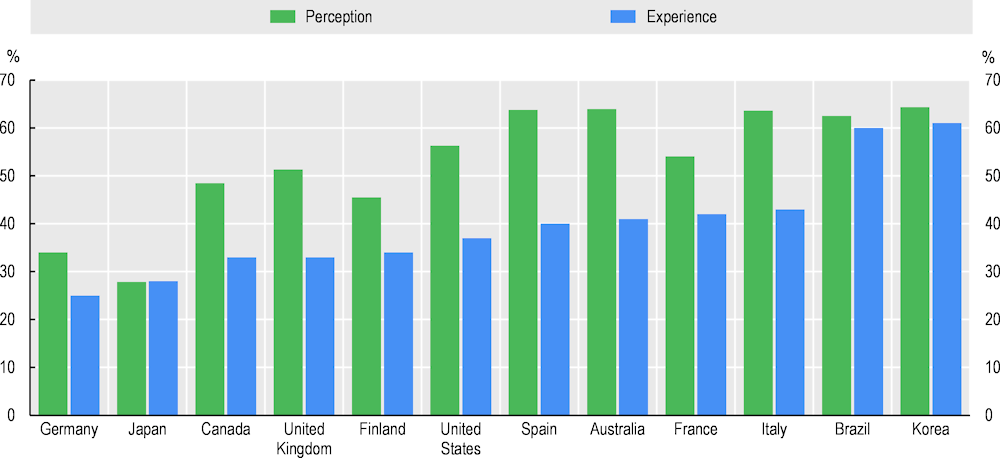

Despite legislation outlawing age discrimination in nearly all OECD countries, bias and discrimination continue to be barriers limiting career mobility within and across firms. According to the 2022 AARP Global Employee Survey, more than half (53%) of workers aged 45 and above perceive that older workers face age discrimination in the workplace. Meanwhile, 40% of workers aged 45 and above have personally experienced some form of age discrimination, indicating that older workers’ perceptions are not unfounded (Figure 4.1). These perceptions of ageism magnify the consequences for job mobility by leading older workers to restrict their job search (e.g. only focusing on poor-quality jobs) or to stop searching for different opportunities altogether (Carlsson and Eriksson, 2019[2]).

Figure 4.1. Older workers report widespread experience of discrimination

Share of workers (45+) who have perceived or experienced discrimination in the workplace

Note: Responses were taken from an online survey conducted in June/July 2022 of individuals aged 25 and over in the 12 participating countries shown. Respondents aged 45 and over (n = 6 551). Perception is based on those who answered yes to the question “Based on what you have seen or experienced, do you think older workers face discrimination in the workplace today based on age?”. Experience is based on the question “Please tell me whether any of the following has happened to you at work since turning 40”.

Source: AARP Global Employee Survey (2022).

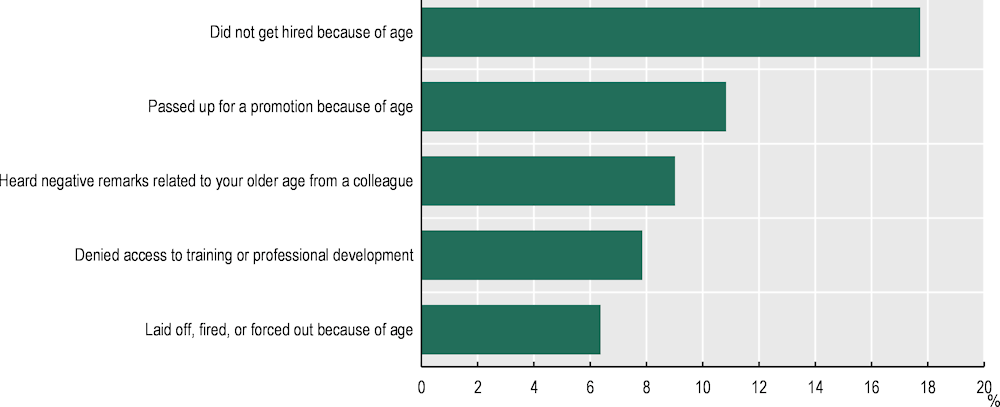

The persistence of ageism undermines older workers’ capacity to conduct fulfilling careers in the workplace. The 2022 AARP Global Employee Survey shows that hiring discrimination and diminished access to training are among the most common forms of discrimination experienced by workers aged 45 and above. A significant minority of these workers report that they were often not hired (18%), passed up for promotion (11%), or denied access to training or personal development because of their age (8%) (Figure 4.2). These barriers may contribute to career stagnation that pushes older workers out of the labour market prematurely.

Figure 4.2. A significant minority of older workers experience hiring discrimination

Share of workers (45+) who experienced any of the following situations at work since turning 40

Note: Responses were taken from an online survey conducted in June/July 2022 of individuals aged 25 and over. Data show the unweighted average of the 12 participating countries (Australia, Brazil, Canada, Finland, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, Korea, Spain, the United Kingdom, the United States). Employed respondents aged 45 and over (n = 6 551) were asked, “Please tell me whether any of the following has happened to you at work since turning 40.”

Source: AARP Global Employee Survey (2022).

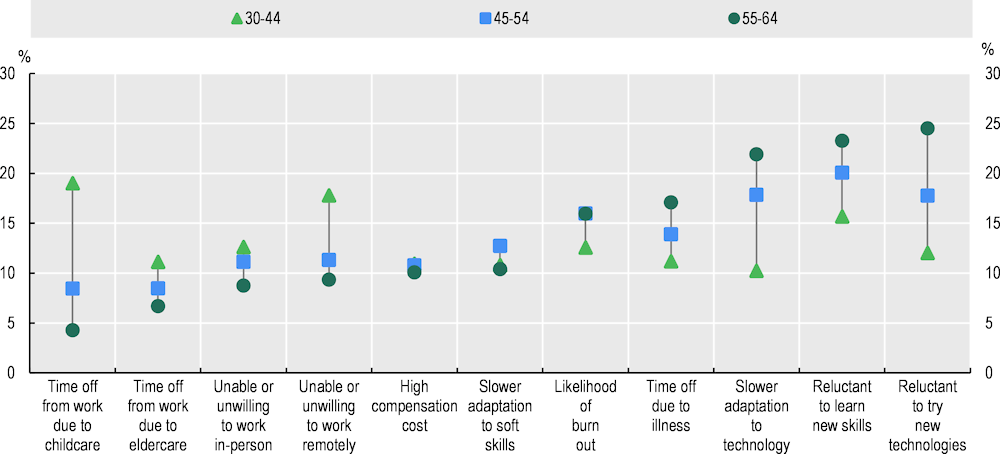

Mid-career and older workers are a diverse group of workers, meaning that any characterisation or generalisation of their abilities is misleading. Nonetheless, many employers continue to hold stereotypical views on the strengths and weaknesses of these workers, thereby influencing their hiring and promotion decisions. A 2023 Generation and OECD Survey of hiring managers found that 25% of hiring managers reported that they believe that workers aged 55‑64 are more reluctant to try new technologies, reluctant to learn new skills (23%) and are slower to adapt to technology (22%) (Figure 4.3). The findings are supported by field research in Sweden which found that call back rates decline substantially in workers’ early 40s, with women faring worse than men (Carlsson and Eriksson, 2019[2]). A similar experiment in Switzerland uncovered that the likelihood of an unemployed worker to be invited to an interview or reemployed decreases with age (Oesch, 2020[3]). As the use of technologies (e.g. artificial intelligence) for hiring and promotion expands, careful attention must be paid to ensure that the use of such tools does not systematise pre‑existing age‑related biases (Box 4.1).

Figure 4.3. Employers say older workers are reluctant to try new technology or learn new skills

Share of employers who report that the factors negatively impact applicants’ success, by age

Note: Responses were taken from an online survey conducted in February/March 2023 of hiring managers. Data show the unweighted average of the eight participating countries (Czechia, France, Germany, Romania, Spain, Sweden, the United Kingdom, the United States). Respondents (n = 1 510) were asked, “Which of the following characteristics do you think are most likely to negatively impact the success of the following applicants?”

Source: (OECD/Generation: You Employed, Inc., 2023[4]), The Midcareer Opportunity: Meeting the Challenges of an Ageing Workforce, https://doi.org/10.1787/ed91b0c7-en.

Most OECD countries have introduced legislation tackling age‑discrimination in hiring, as well as ad hoc proactive initiatives to change employer attitudes towards older workers. However, the effectiveness of these interventions is limited by lack of enforcement and procedural or economic difficulties associated with bringing discrimination cases to court (OECD, 2019[5]). Tackling age discrimination at all stages of the recruitment and promotion processes in firms is key to retain talent of older workers as well as addressing labour shortages. Previous OECD reports suggest that age‑friendly job advertisements, age‑blind hiring, semi-structured panel interviews, and blind-hiring software (e.g. attitude tests or games) can be used to suppress implicit and explicit biases that disadvantage older workers in application processes (OECD, 2020[6]).1 Implementation of these measures should be accompanied by procedures to continuously monitor and evaluate whether they achieve their inclusivity aims.

Box 4.1. The future of AI and inclusive hiring practices at all stages

The expansion of AI-powered tools used for hiring and recruitment has introduced new risks and opportunities for the job mobility of mid-career and older workers. On one hand, AI-powered tools may assess workers more objectively than hiring managers influenced by implicit or explicit biases. On the other hand, historical biases imbedded in training data or the algorithm itself can entrench age‑related hiring biases that existed prior to AI, as well as raise questions about meaningful consent and transparency. The adoption of AI-powered tools for hiring and recruitment is still in its early stages (Broecke, 2023[7]). Policies and regulations (e.g. the European Union AI Act and auditing requirements) to foster the development of trustworthy AI and promote responsible implementation protocols are, therefore, critical to preventing systematised discrimination as the market continues to grow. Examples of AI-powered hiring and recruitment tools include:

Job search platforms and social media platforms use algorithms to select who will view a job posting based on variables such as age, ethnicity, gender, job seniority or connection to other companies (Salvi del Pero, Wyckoff and Vourc’h, 2022[8]). The tools may introduce new biases by intentionally or unintentionally excluding older workers from viewing job advertisements. For example, in the United States, T-Mobile posted a job advertisement that was targeted only to individuals aged 18‑38 (Kim, 2018[9]).

Hiring managers leverage AI-powered algorithms to screen candidates, such tools review candidates’ curricula vitae (CVs) or assess candidates based on gamified assessment tools. AI-powered CV screening tools often rely on historical data and may, therefore, mimic biased decisions that were made in the past. Recent evidence suggests that age‑related biases are particularly challenging for algorithms to correct (Harris, 2022[10]). Gamified assessments, on the other hand, rank or match candidates based on their demonstrated skills, irrespective of age.

AI-powered video interviews became more commonplace during COVID‑19 to screen high volumes of candidates using limited resources. While the emerging evidence on whether these technologies are more objective than human interviewers is mixed, mid-career and older applicants may find the interviews impersonal and uncomfortable.

4.2.2. Career advancement and professional development

In addition to influencing hiring and promotion decisions, employer attitudes can undermine career advancement and professional development opportunities offered to older workers, thereby forging a gap between age groups. Due to demographic trends, workers are remaining employed for longer, yet employer attitudes, on average, have not adapted to a shift towards lifelong learning. As discussed in Chapter 3 employers may be apprehensive to invest in training and professional development for older workers without “long-term” prospects within the firm or perceive that older workers are uninterested in training or less likely to adapt to new technologies (Cedefop, 2012[11]). These beliefs widen the skills gap between older and younger workers, which, in turn, makes progression more difficult with age.

To close career progression gaps, it is crucial that employers encourage participation in training and convey its value to older workers who do not know if training is worth their time (Chapter 3). For instance, BNP Paribas Portugal recognised that tapping into experienced employees is key to sustainable growth of their firm. The Built to Shift Programme emerged as a skills development programme with the aim of encouraging experienced workers of all ages to polish their skills, remain up to date with new trends in the banking sector, and exchange information across departments and, importantly, generations (OECD, forthcoming[12]). The programme is designed to integrate a mix of interactive elements focused on three pillars important for the future of work: trends, tools, and soft skills development. Diverse sessions include inspirational sessions, practical workshops, and group activities to facilitate collaboration and knowledge sharing. For initiatives such as these to be effective, managers must set a positive example and promote participation so that workers will not feel penalised or discouraged from taking advantage of career development opportunities.

4.3. What policy levers can help employers harness internal mobility?

4.3.1. Identify better skill matches for older workers within the company

Holistic age management policies that stimulate internal mobility (e.g. job rotation and redeployment programmes, mid-career reviews and intergenerational knowledge transfers) can benefit both employers and workers by addressing skills shortages and forming better labour market matches without having to seek outside opportunities. Each of these polices are oriented towards prevention, rather than reaction, to challenges arising in an ageing workforce, thus pre‑empting difficulties that may push older workers out of the labour market prematurely. Unfortunately, the 2020 AARP Global Employer Survey revealed that far too few employers make use of proven approaches (OECD, 2020[6]).

Job rotation and redeployment programmes help workers, particularly those with health-related issues or those in arduous occupations, to identify and transition into roles that better align with their skills and aspirations. Job rotation programmes are commonly targeted at new graduates. However, they can also enable more experienced, older workers to move laterally between workstations or tasks on a temporary basis without the intention of returning to their original role (OECD, 2020[6]). Rotating between roles has been shown to expand workers’ skillsets and can help identify roles that are a better fit for the next stage of their career (Botti, Calzavara and Mora, 2021[13]). Moreover, the programmes enable knowledge transfer between more experienced and early career employees, which in turn, strengthens organisational resilience and functional flexibility.

While some job rotation programmes can last several months, others offer workers short-term opportunities to experiment with other positions in the company before committing to a career change. In job shadowing programmes, workers observe someone else as they carry out their role. On the other hand, cross-training programmes give workers a more hand-on role as a short-term substitute or fill-in for workers in essential roles when needed. Not only does cross-training alleviate staffing needs, but it can help managers identify future candidates for hard-to-fill roles (Proctor, 2023[14]).

In a similar nature, redeployment schemes – where employers reallocate workers between roles within the firm – can act as a preventative measure to protect workers’ from developing or worsening occupational health-related injuries. Offering redeployment opportunities demonstrates to workers that their firm values their skills and experiences, as well as facilitates enriching intergenerational exchanges (Mitchell, 2022[15]). With that in mind, qualitative evidence suggests that employers sometimes misuse redeployment schemes to address organisational needs (e.g. skills shortages), rather than prioritising workers’ needs (Lain, Vickerstaff and van der Horst, 2022[16]). It is, therefore, important that employers mindfully implement redeployment schemes in such a way that is mutually beneficial to themselves and workers. Framing redeployment as a means to maintain employability, enhance flexibility and improving health is a best practice to ensure that workers do not feel downgraded or deskilled by the change (Naegele and Walker, 2006[17]). Moreover, these schemes are best complemented by retraining and upskilling initiatives that prepare workers for a job change. While employer-sponsored redeployment schemes are ideal, government-sponsored redeployment schemes, such as the Luxembourg Professional Redeployment Programme (Reclassement Professionnel), can enable workers with disabilities to extend their careers (Box 4.2).

Box 4.2. Professional redeployment for workers with health barriers

Professional redeployment is also an attractive solution for older workers whose health status means that that are no longer able to perform in their past job but are not yet eligible to receive a disability pension. Since 2016, the Professional Redeployment Programme (Reclassement Professionnel) in Luxembourg encourages eligible workers reintegrate into a role that is adapted to their health and flexibility needs within the same company. In cases where internal redeployment is not possible, workers may be eligible for external redeployment, where they are required to meet with a career advisor to discuss their skills, interests, and medical restrictions through the public employment services. To protect workers from occupational downgrading due to their health, some workers are entitled to a compensatory allowance to cover income differentials between their current and former jobs. Such elements of the intervention are designed to enable workers with certain disabilities remain engaged in the labour market, despite barriers that would have otherwise pushed them out of work.

Redeployment or outplacement schemes are also effective policy tools when workers are made redundant due to company restructuration. At the government-level, Belgium’s Outplacement Regime for Workers Aged 45 and Above (Régime particulier – travailleurs âgés de 45 ans et plus) and Czechia’s Project Outplacement (Projekt Outplacement (OUT) are programmes targeted at minimising unemployment duration for displaced workers.

4.3.2. Help older workers plan for career transitions

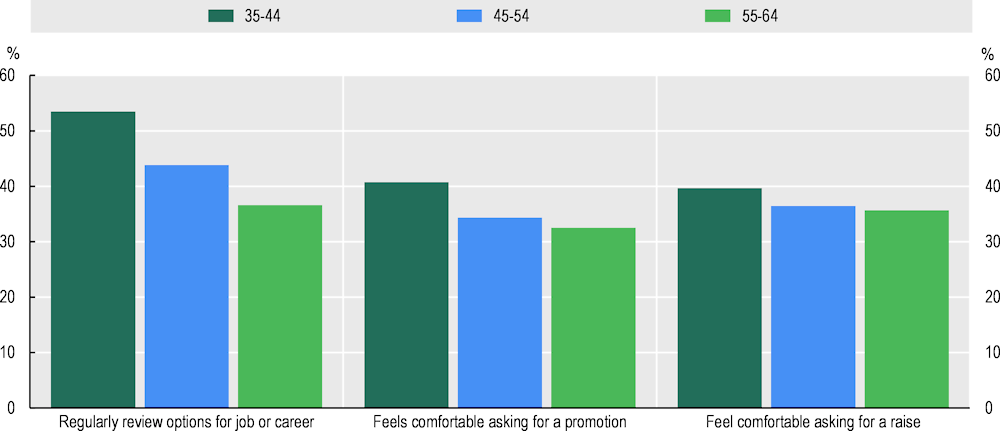

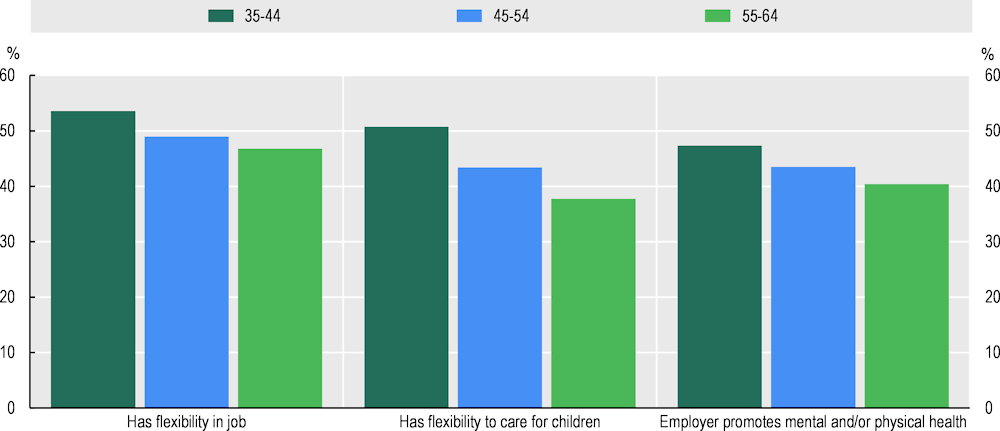

Many workers aged 45 and over wish to change jobs or progress in their careers at later stages, but the pathway to do so is not clearly defined. As workers age and take on management responsibilities of their own or become more comfortable in their roles, they report having fewer chances to regularly review the options for their job or career or feel less comfortable asking for a promotion (Figure 4.4). This reality is particularly troublesome for workers aged 45 and above with lower levels of education who are 14 percentage points less likely to regularly review the options for their job (47% vs. 33%). Nevertheless, it is increasingly important for workers of all skill-levels to proactively reflect on career mobility before change becomes unavoidable or is no longer feasible.

Mid-career reviews (MCRs), where employers carry out an assessment of workers at a mid-point in their working life, help to identify mobility and training pathways that can improve older workers’ longevity within the firm (OECD, 2019[5]). Rather than simply reviewing workers’ performance, MCRs generate a broad conversation about workers’ current and future aspirations, such as skill development, implications of work on their health, and their retirement plans. Workers and their line managers jointly develop action plans to enrol in training, transition to a flexible work arrangement or even discuss horizontal transfers within the firm (Business in the Community, 2018[18]; Eurofound, 2016[19]). Mid-career reviews or career conversations can also be combined with training and career development opportunities for both workers and managers to strengthen intergenerational relationships (Box 4.3).

Figure 4.4. Opportunities to discuss career options become less common with age

Share of workers (35+) who responded “Agree” or “Strongly agree”

Note: Responses were taken from an online survey conducted in June/July 2022 of individuals aged 25 and over. Data show the unweighted average of the 12 participating countries (Australia, Brazil, Canada, Finland, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, Korea, Spain, the United Kingdom, the United States). Employed respondents aged 35 and over (n = 8 106) were asked, “How strongly do you agree or disagree with the following statements about your job?”

Source: AARP Global Employee Survey (2022).

Career reviews can be used to identify candidates for horizontal transfers and help retain workers with specialised knowledge and skills that are valuable to the firm. Eurofound interviewed employees and HR representatives from Frosta Sp. z o. o., the Polish representative of the Germany Company Frosta AG, which produces frozen meals (Eurofound, 2016[19]). In addition to helping workers upskill and creating new positions, annual career reviews have helped Frosta facilitate horizontal transfers to roles that better suit their capabilities and expectations. For example, following a career review, several conversations, and brainstorming sessions with senior management, a manager with weakened performance was redeployed to a new role that was more experience oriented. The example underlines how firms can draw on horizontal transfers to form better labour market matches without discharging workers.

While career reviews are beneficial for workers of all ages, it is crucial that companies target older workers who are less likely to reflect on their career or take part in training (Figure 4.4). To emphasise the importance of career reviews to older workers without excluding younger workers, companies may choose to extend a special invitation to all workers above an age‑threshold but advertise voluntary career reviews to everyone at the firm.

Box 4.3. “Design the Last Miles of Your Career” at Schneider Electric

Schneider Electric is a French-based energy company with over 115 000 employees working across 115 countries. Demographic changes within their workforce has raised concerns about impending labour market shortages. In response, in 2021, the company introduced the Senior Talent Program, which aims to harness older workers full potential through skill and career development opportunities tailored to workers’ unique profiles. A key element to the programme is a Global Toolkit that is designed to provide a framework of suggestions that countries can tailor to suit their local contexts, such as fostering career conversations and offering flexible working conditions.

As part of the programme, in France, Schneider Electric piloted the “Design the Last Miles of Your Career” initiative to cultivate engagement and enhance employability of older workers. Both managers and workers participated in career development events, which included training and career coaching for workers and webinars for managers. The pilot ended with career discussions between managers and employers. During the debrief session, workers remarked that the investment of the company’s time and resources made them feel appreciated and listened to. Creating opportunities for workers and managers to interact are a simple way to empower older workers to express their career goals and ambitions.

Source: (OECD, forthcoming[12]), “Career Paths and Engagement of Older Workers”.

4.3.3. Attract older workers with remote work

For many workers with health-related barriers and care responsibilities, flexible accommodations are crucial to continue working happily and sustainably over the long term. However, according to the 2022 AARP Global Employee Survey, the share of workers with flexibility in their jobs declines with age (Figure 4.5). Workers aged 35‑44 are 7 percentage points more likely to agree that they have flexibility in their jobs compared to those aged 55‑64 (54% vs. 47%). Lack of flexibility is particularly troublesome for workers aged 45 and over with low levels of education who face a 14-percentage point gap between themselves and workers with high levels of education (54% vs. 40%). Without widespread employment-oriented support and workplace adaptation, short-term joblessness among workers with health barriers or care responsibilities is at high risk of translating into permanent inactivity. It is, therefore, crucial for employers to offer flexible accommodations (e.g. remote work and flexible scheduling) to attract and retain older workers.

Figure 4.5. Older workers are less likely to have flexibility in their jobs

Share of workers (35+) who responded “Agree” or “Strongly agree” with the following statements about their job

Note: Responses were taken from an online survey conducted in June/July 2022 of individuals aged 25 and over. Data show the unweighted average of the 12 participating countries (Australia, Brazil, Canada, Finland, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, Korea, Spain, the United Kingdom, the United States). Employed respondents aged 35 and over (n = 8 106) were asked “How strongly do you agree or disagree with the following statements about your job?”

Source: AARP Global Employee Survey (2022).

The expansion of remote working or teleworking during the COVID‑19 pandemic has been associated with enhanced average levels of job satisfaction, work-life balance, and mental and physical health among younger and older workers alike (Broecke and Touzet, 2023[20]). Yet, the benefits of remote work are particularly relevant as workers age and place more value on their work-life balance. Remote work arrangements make it easier for older workers to balance their work and outside commitments (e.g. care responsibilities, hobbies), as well as reduce commute time that may have otherwise prohibited job mobility. As a result, evidence suggests that remote working has led to greater reductions in psychological job demands compared to returning to the office post-pandemic, especially among older women and men (Fan and Moen, 2023[21]). By reducing job pressures, workers with remote work can extend their working lives or move to different locations for all or part of the year (Box 4.5) (Powell, 2021[22]). Those without remote work, on the other hand, are increasingly more interested in transitioning to roles that match their remote work preferences (Barrero, Bloom and Davis, 2023[23]).

Box 4.4. Fully remote working combines geographic mobility and career mobility

Fully remote working arrangements allow workers to combine career mobility with geographic mobility. Chapter 3 explained ways in which institutional and personal barriers prevent workers from moving for a job. Remote working arrangements smooth some of the “frictions of geographic mobility” by enabling workers to settle in one location but hold a job elsewhere. Older workers with fully remote work arrangements have the freedom to live in regions with a lower cost of living, a better lifestyle, or easier access to medical facilities. Employers also benefit from widening their pool of candidates outside of the local labour markets and immigration limitations. To take advantage of the enhanced flexibility, more older workers may begin placing higher value on remote working policies when changing jobs.

As fully remote work becomes more common, place‑based policies help shape where people choose to move to and have implications for regional development (OECD, 2021[24]). For instance, governments (e.g. Croatia, Estonia, Germany, Mexico, Norway, and Spain) have begun issuing 6‑month nomad visas to attract workers globally and stimulate economic growth in declining regions (Choudhury, 2022[25]). For the past decade, Chile has offered qualified entrepreneurs a year-long visa and up to USD 40 000 in equity-free grants and benefits to contribute to the Chilean entrepreneurial ecosystem through Start-Up Chile. That being said, some economists and policy makers have raised concerns regarding the impact of remote work-induced geographic mobility on the demand for services (and the consequences for workers) within city centres that are emptied out (Althoff et al., 2022[26]).

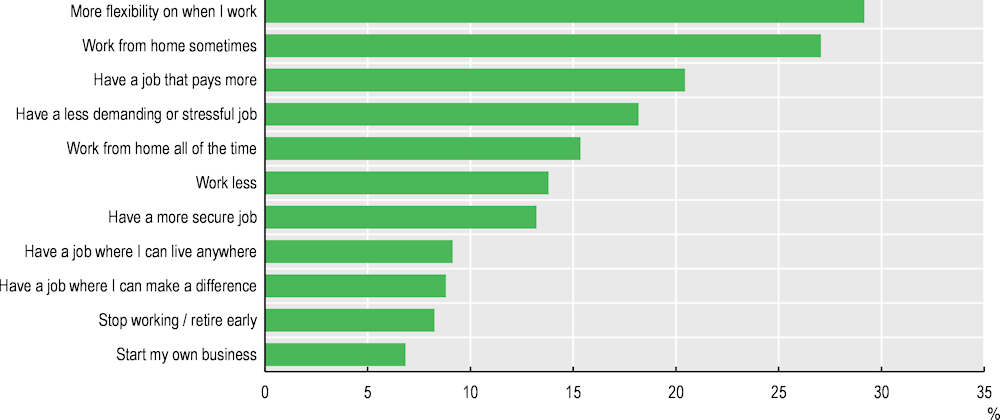

Remote working arrangements exist on a spectrum, which, in turn, offers workers a range of options to suit their requirements. According to the 2022 AARP Global Employee Survey, respectively 27% and 15% of workers reported that COVID‑19 made them want to work from home sometimes or all of the time (Figure 4.6). Since older workers are more likely to hold more senior or management roles and less likely to have childcare obligations, they are, on average, more resistant to fully remote schedules compared to employees aged 30‑49 (Barrero, Bloom and Davis, 2023[23]). Therefore, hybrid work schedules that combine working from home at the office are particularly attractive to older workers who value both socialisation with colleagues and the comfort of working from home or in a public space. Hybrid work overcomes some challenges associated with fully remote work by enabling face‑to-face communication, facilitating in-person learning, and enforcing greater accountability, to name a few reasons. At the same time, hybrid work arrangements are still geographically bound, which makes it difficult to take full advantage of mobility towards regions with robust job opportunities or family. Providing additional measures to support geographical mobility can help (as discussed in Chapter 3).

Figure 4.6. Older workers place more value on flexibility after COVID‑19

Share of workers (45+) who responded “Yes” to “Thinking about the impact of the COVID‑19 pandemic on your job, has it made you realise that you want any of the following options?”

Note Responses were taken from an online survey conducted in June/July 2022 of individuals aged 25 and over. Data show the unweighted average of the 12 participating countries (Australia, Brazil, Canada, Finland, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, Korea, Spain, the United Kingdom, the United States). Employed respondents aged 45 and over (n = 5 231).

Source: AARP Global Employee Survey (2022).

Moreover, remote work is not feasible for all occupations, including many arduous jobs and those in the service sector. Unlike occupations that only require a laptop and internet connection, workers that are required to work outdoors or use heavy equipment have low remote working potential. There is a strong correlation between skill-level required for an occupation and its remote working potential, which raises concerns about inequality (OECD, 2021[24]). To accommodate these workers, employers can instead explore redeployment into roles that are amenable to remote work, flexible scheduling, or part-time working arrangements.

4.3.4. Policies to mitigate the motherhood penalty are vital for improving career mobility for women

The arrival of children has a big impact on family life and women are more likely to take paid leave or work part-time. The high cost of childcare and long-term care in many countries can prevent women from re-entering the labour force or lead women to leave current positions in search of more flexible working arrangements. More generous support for childcare, such as public provision or subsidies plays a key role in supporting female labour force participation (Albanesi, Olivetti and Petrongolo, 2022[27]). Paternity leave should also be expanded to improve the work-life balance of mothers and fathers (and other family types)2. When periods of parental leave and part-time work are time-limited and shared by men and women, this reduces the risk of women being side-lined for promotions and pay increases. Some evidence suggests that longer maternity leave periods can drive persistent declines in women’s health-related physical performance and delay’s women’s career advancement (Healy and Heissel, 2020[28]). Policies such as increased access to affordable childcare may therefore have fewer unintended consequences.

Recent policy reforms have expanded opportunities for fathers to take up some parental leave through earmarked months or bonus systems (OECD, 2021[29]). Only seven OECD countries offered some parental leave that was reserved for fathers in 1995, by 2020 34 countries did so. The EU has recently taken legislative action through the Work-Life Balance directive (Directive 2019/1158/EU), which among other issues aims to encourage more equally shared parental leave. It stipulates that each parent will have an individual right to four months paid parental leave, of which at least two will be non-transferable (OECD, 2022[30]).

The tax and benefit system is often structured such that the incentives for the lowest earning partner (often women) to work or to work full-time are reduced. In some OECD countries, married couples and civil partners have the option to file joint income tax returns, which can lead to a lower marginal tax rate for the couple compared to filing separately, thanks to progressive tax schedules. While this can decrease the total tax burden for the family, it results in a higher marginal tax rate for the partner with lower earnings. Countries with tax systems that benefit families with a single or primary earner should consider modifying their systems towards neutrality or, to better promote gender equality, adopt individual taxation. To mitigate any financial losses from these changes, governments should enhance transparent family support measures or lower individual income tax rates (OECD, 2021[29]).

The gap in opportunities for career progression for women calls for policies targeted at firms. Equal pay and anti-discrimination laws are in place across OECD countries; however, these existing laws largely work through empowering individuals to enforce equal rights. To more effectively narrow these gaps, policy measures targeting firms, such as pay transparency tools, quotas, and voluntary targets, are recommended. Pay transparency measures are emerging as a key strategy to address gender wage gaps, especially within firms, inspired by the 2014 European Commission Recommendation on strengthening the principle of equal pay between men and women through transparency. These measures aim to make systematic pay differences more visible and include job classification systems, non-pay gender-disaggregated reporting, regular gender pay reporting, and audited pay gap reporting. Equal pay audits analyse the gender distribution of pay differentials across job categories with the aim of embedding gender-sensitive practices in firms. These audits provide a clearer path for action and lessen the individual's burden to combat wage disparities. They highlight the root causes of gender pay gaps and are suggested for all firms, with supports to ease the administrative load on smaller businesses. In the OECD, nine countries, including Canada, Norway and Switzerland, implement such pay auditing processes (OECD, 2021[31]).

Broader factors such as education and educational choices also significantly influence gender differences in career progression and pay gaps. Across OECD countries young women are on average more likely to obtain higher educational attainment than young men, however, men continue to dominate in STEM fields, which often lead to higher-paying careers. This disparity is attributed more to societal attitudes than to aptitude, indicating that changing these norms and influencing educational choices is a gradual process. Gender norms and culture have been shown to be important in transmitting child penalties through generations (Kleven, Landais and Søgaard, 2019[32]).

4.3.5. Consulting and independent contracts can keep workers engaged whilst facilitating a smoother transition to retirement

Internal transitions from standard work contracts to independent or consulting contracts can be particularly attractive for older workers approaching the end of their careers. Older independent contractors benefit from greater flexibility while remaining engaged in their work as they ease into retirement (Terrell, 2019[33]). Evidence from the United States finds that nearly one‑quarter of independent contractors aged 50 or older work for a former employer (Abraham, Hershbein and Houseman, 2021[34]). Opportunities to take‑up independent contract work are most common among highly educated individuals, but that does not necessarily need to be the case (Abraham, Hershbein and Houseman, 2021[34]). Workers of all skill levels bring specialised skills and expertise that are desirable in training, mentoring and management consultants. Facilitating these types of interactions between older and younger workers promote intergenerational exchanges that prevent knowledge loss that may occur when experienced workers retire (Box 4.5). It also helps workers feel that their expertise is valued by management.

In most countries, however, independent contractors are not entitled to the same benefits and entitlements as workers in standard employment contracts, such as supplemental health insurance and employer-sponsored retirement contributions. In the United States, for example, individuals cannot enrol in Medicare health benefits until they reach 65 years old. As a result, the rate of self-employment markedly increases at age 65 (Appelbaum, Kalleberg and Rho, 2019[35]; Abraham, Hershbein and Houseman, 2021[34]). This highlights governments’ role in providing universal health policies that protect individuals regardless of their employment classification. For those who are below the threshold, conversations between management and workers are necessary to weigh the risks of transitioning to contract work. Employers are also encouraged to offer wages commensurate with their previous salaries to prevent managers from taking advantage of independent contracts to lower expenses.

Box 4.5. Intergenerational knowledge transfers with Bosch’s “Senior Expert Program”

Facilitating intergenerational knowledge transfers is crucial to preventing knowledge loss as workers retire. Bosch is a German multinational engineering and technology company with more than 421 300 associates across 60 countries (Bosch, 2022[36]). Bosch taps into older workers’ knowledge and experience through the “Senior Expert Program”, which allows experienced workers to transition to a diverse set of roles within the company such as training, mentorship, interim management, or quality assurance (EBRD, 2020[37]). These experts are hired as consultants or project contracts and are paid a competitive wage reflective of their former salaries (Bosch, n.d.[38]). Currently, there are more than 2 400 senior experts worldwide, representing more than 50 000 years of professional experience (Bosch, n.d.[38]).

The programme has been crafted to provide support not only to the company but also to its workers. Bosch benefits from the transfer of valuable knowledge to the next generation of Bosch associates. These intergenerational dialogues encourage conversations that stimulate creativity and innovation. Senior experts are similarly reassured that their experience is appreciated and that they can stay in touch with their field of expertise as they make a smooth transition into retirement.

4.3.6. Support older workers to redesign their roles with job crafting initiatives

Job crafting enables workers to re‑construct their job description to suit to their changing needs. Over time, job expectations evolve with workers’ priorities changing, as well as the nature of the job changing. Traditional job redesign processes are top-down and standardised. Job crafting, on the other hand, allows workers and employers to devise a bottom-up, individualised approach to reconstructing job descriptions in such a way that improves their productivity and satisfaction (Wong and Tetrick, 2017[39]). Wrzesniewski and Dutton’s original theoretical framework for job crafting divides the process into three types (Wrzesniewski and Dutton, 2001[40]):

Task crafting: Workers are encouraged to reconsider the type and scope of tasks that they are expected to perform. For older workers, task crafting may include reducing the number of tasks to lower job strain.

Relational crafting: The changes cover the interpersonal qualities of a job, including the frequency and types of interactions with colleagues. Older workers may wish to increase the number of interactions that give them emotional or social fulfilment.

Cognitive crafting: This type of crafting encourages workers to consider their perceptions and cognitive representations of their jobs. In other words, older workers can reflect on aspects of their jobs that would provide them with more meaning or fulfilment.

More recently, well-being crafting has emerged as the fourth type of job crafting used support workers by managing stress-levels through remote work and work-life balance initiatives. Hybrid and fully remote work, personalised training programmes, and a wide array of communication tools (e.g. messaging apps) create new ways for workers to restructure their tasks with greater flexibility.

In the process of identifying aspects of work that are personally meaningful and motivating, older workers optimise their productivity and improve longevity (Wong and Tetrick, 2017[39]). Moreover, employers that support job crafting cultivate an environment for innovation by stepping away from static job descriptions that leave little room for creativity. It is important, however, that boundaries are established from that start so that modifications align with organisational goals. Periodic reviews or evaluations should be carried out to ensure that workers do not stray from these organisational objectives.

4.3.7. Rethinking seniority-based wages and tenure‑pay policies

As discussed in Chapter 3, seniority wages or tenure‑pay policies can undermine job mobility for mid-career and older workers. Despite a downward trend, seniority wages remain dominant in many OECD countries, and especially so in Korea and Japan where wage‑setting practices have been shown to lower re‑hiring prospects of older workers (OECD, 2019[5]). Additional evidence at the firm-level suggests that employers with steeper seniority wage profiles underpay workers at the beginning of their contracts with the promise of compensating for the productivity-pay gap as they progress internally (Zwick, 2012[41]). This system leads to an incentive structure that favors internal recruitment of young, male workers with less experience and longer tenure potential over older workers and young women. Better aligning wage profiles to productivity at all stages of the career is desirable where possible.

Key recommendations

Persistent ageism stemming from stereotypical views on the strengths and weaknesses of older workers influences hiring and promotion decisions, which in turn impedes career advancement. Employers can put concrete measures in place (e.g. attitude tests, age‑blind hiring, etc.) to suppress implicit or explicit biases that seep into application processes.

Some older workers (8%) reported that they have been denied access to training or professional development because of their age. It is crucial that employers actively promote career advancement and professional development for older workers who may not see the value of training.

The quality of job matches can deteriorate with age or long tenure. Job rotation and re‑deployment programmes can help workers, especially those with health-related issues or those in arduous occupations, to transition to roles that better align with their skills and career goals.

Older workers are among the least likely to review their career options or ask for a promotion. Mid-career reviews (MCRs) encourage older workers and their managers to identify mobility and training pathways that can improve older workers’ longevity and satisfaction within the company.

Although flexibility is increasingly important to workers as they age, older workers are among the least likely to access flexibility in their jobs. Employers can enable older workers to transition to fully remote or hybrid remote work arrangements, which make balancing work and outside commitments more manageable.

A variety of family, fiscal, and broader social policies targeted at supporting women in resuming their careers in high-quality positions after taking breaks is essential. This includes policies targeted at households such as equal uptake of parental leave by mothers and fathers and the provision of formal childcare and out-of-school-hours services for all young children. Also essential are policies targeted at firms such as pay transparency measures, for example equal pay audits.

Firm-specific knowledge will deplete as experienced workers retire. Allowing workers near retirement to become independent contractors promotes intergenerational knowledge sharing and offers workers flexibility.

Seniority-based wages and tenure‑pay policies may discourage companies from promoting older workers relative to younger colleagues. Increasing internal mobility among older workers calls for better aligning wages with productivity.

References

[34] Abraham, K., B. Hershbein and S. Houseman (2021), Contract work at older ages, https://doi.org/10.1017/S1474747220000098.

[27] Albanesi, S., C. Olivetti and B. Petrongolo (2022), “Families, Labor Markets, and Policy”, Working Paper, No. 30685, NBER, Washington, DC, http://www.nber.org/data-appendix/w30685 (accessed on 22 December 2022).

[26] Althoff, L. et al. (2022), “The Geography of Remote Work”, Regional Science and Urban Economics, Vol. 93, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.regsciurbeco.2022.103770.

[35] Appelbaum, E., A. Kalleberg and H. Rho (2019), “Nonstandard Work and Older Americans, 2005–2017”, Challenge, Vol. 62/4, https://doi.org/10.1080/05775132.2019.1619043.

[23] Barrero, J., N. Bloom and S. Davis (2023), “The evolution of working from home”, Stanford University, https://wfhresearch.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/SIEPR1.pdf.

[36] Bosch (2022), Company Overview, https://www.bosch.com/company/.

[38] Bosch (n.d.), 50,000 years of experience, https://www.bosch.com/stories/senior-experts-at-bosch/.

[13] Botti, L., M. Calzavara and C. Mora (2021), “Modelling job rotation in manufacturing systems with aged workers”, International Journal of Production Research, Vol. 59/8, pp. 2522-2536, https://doi.org/10.1080/00207543.2020.1735659.

[7] Broecke, S. (2023), “Artificial intelligence and labour market matching”, OECD Social, Employment and Migration Working Papers, No. 284, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/2b440821-en.

[20] Broecke, S. and C. Touzet (2023), Teleworking, workplace policies and trust: A critical relationship in the hybrid world of work, https://www.oecd.org/employment/Teleworking-workplace-policies-and-trust.pdf.

[18] Business in the Community (2018), How to conduct Mid-Life Career Reviews, https://www.bitc.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/BITC-Age-Toolkit-Howtodelivermidlifecareerreviews-linemanagersguide-Revised2020.pdf.

[2] Carlsson, M. and S. Eriksson (2019), “Age discrimination in hiring decisions: Evidence from a field experiment in the labor market”, Labour Economics, Vol. 59, pp. 173-183, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.labeco.2019.03.002.

[11] Cedefop (2012), “Working and aging: The benefits of investing in an ageing workforce”, European Centre for the Development of Vocational Training (Cedefop), https://doi.org/10.2801/904.

[25] Choudhury, P. (2022), The Changing Geography of Work: Priorities for policy makers, https://www.oecd-forum.org/posts/the-changing-geography-of-work-priorities-for-policy-makers-ff73e554-1222-4ddd-9f15-d8f423978021.

[37] EBRD (2020), Economic inclusion for older workers: Challenges and responses, https://www.ebrd.com/what-we-do/projects-and-sectors/economic-inclusion/disabilities-older.html.

[19] Eurofound (2016), Changing places: Mid-career review and internal mobility, Publications Office of the European Union, https://doi.org/10.2806/42599.

[21] Fan, W. and P. Moen (2023), “The Future(s) of Work? Disparities Around Changing Job Conditions When Remote/Hybrid or Turning to Working at Work”, Work and Occupations, https://doi.org/10.1177/07308884231203668.

[10] Harris, C. (2022), “Age Bias: A Tremendous Challenge for Algorithms in the Job Candidate Screening Process”, 2022 International Symposium on Technology and Society (ISTAS), pp. pp. 1-5, https://doi.org/10.1109/ISTAS55053.2022.10227135.

[28] Healy, O. and J. Heissel (2020), “Baby bumps in the road: The impact of parenthood on job performance and career advancement”.

[9] Kim, P. (2018), “Big Data and Artificial Intelligence: New Challenges for Workplace Equality”, University of Louisville Law Review, Vol. 57/313, https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3296521.

[32] Kleven, H., C. Landais and J. Søgaard (2019), “Children and gender inequality: Evidence from Denmark”, American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, Vol. 11/4, pp. 181-209, https://doi.org/10.1257/app.20180010.

[16] Lain, D., S. Vickerstaff and M. van der Horst (2022), Job Redeployment of Older Workers in the UK Local Government, Bristol University Press, https://doi.org/10.51952/9781529215021.ch003.

[15] Mitchell, L. (2022), Redeploying older workers, https://www.workingwise.co.uk/redeploying-older-workers/.

[17] Naegele, G. and A. Walker (2006), A guide to good practice in age management, European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions, http://www.ageingatwork.eu/resources/a-guide-to-good-practice-in-age-management.pdf.

[42] OECD (2023), Retaining Talent at All Ages, Ageing and Employment Policies, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/00dbdd06-en.

[30] OECD (2022), Report on the implementation of the OECD gender recommendations, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://www.oecd.org/mcm/Implementation-OECD-Gender-Recommendations.pdf (accessed on 13 October 2023).

[24] OECD (2021), Implications of Remote Working Adoption on Place Based Policies: A Focus on G7 Countries, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/b12f6b85-en.

[31] OECD (2021), Pay Transparency Tools to Close the Gender Wage Gap, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/eba5b91d-en.

[29] OECD (2021), The Role of Firms in Wage Inequality: Policy Lessons from a Large Scale Cross-Country Study, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/7d9b2208-en.

[6] OECD (2020), Promoting an Age-Inclusive Workforce: Living, Learning and Earning Longer, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/59752153-en.

[5] OECD (2019), Working Better with Age, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/c4d4f66a-en.

[12] OECD (forthcoming), Career Paths and Engagement of Older Workers, OECD, Paris.

[4] OECD/Generation: You Employed, Inc. (2023), The Midcareer Opportunity: Meeting the Challenges of an Ageing Workforce, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/ed91b0c7-en.

[3] Oesch, D. (2020), “Discrimination in the hiring of older jobseekers: Combining and survey experiment with a natural experiment in Switzerland”, Research in Social Stratification and Mobility, Vol. 65, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rssm.2019.100441.

[22] Powell, C. (2021), Older people who work from home more likely to stay in the workforce, ONS finds, https://www.peoplemanagement.co.uk/article/1743095/older-people-work-from-home-more-likely-stay-workforce-ons.

[14] Proctor, P. (2023), The Benefits of Employee Job Rotations, https://www.business.com/articles/employee-job-rotation/.

[8] Salvi del Pero, A., P. Wyckoff and A. Vourc’h (2022), “Using Artificial Intelligence in the workplace: What are the main ethical risks?”, OECD Social, Employment and Migration Working Papers No. 273, https://doi.org/10.1787/840a2d9f-en.

[1] Tavares, M. (2020), “Across establishments, within firms: workers’ mobility, knowledge transfer and survival”, Journal for Labour Market Research, Vol. 54/1, https://link.springer.com/article/10.1186/s12651-020-0267-y.

[33] Terrell, K. (2019), Why Freelance Work Appeals to Many People, https://www.aarp.org/work/careers/why-older-workers-freelance/.

[39] Wong, C. and L. Tetrick (2017), “Job crafting: Older workers’ mechanism for maintaining person-job fit”, Frontiers in Psychology, Vol. 8/SEP, https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01548.

[40] Wrzesniewski, A. and J. Dutton (2001), “Crafting a job: Revisioning employees as active crafters of their work”, Academy of Management Review, Vol. 26/2, https://doi.org/10.5465/AMR.2001.4378011.

[41] Zwick, T. (2012), “Consequences of seniority wages on the employment structure”, Industrial and Labor Relations Review, Vol. 65/1, https://doi.org/10.1177/001979391206500106.

Notes

← 1. For more information on age bias in recruitment, refer to Promoting an Age-Inclusive Workforce (OECD, 2020[6]).

← 2. On average, OECD countries offer just under nine weeks of paid father-specific leave, either through paid paternity leave or paid father-specific parental or home care leave. In some countries such as Sweden and Norway, partners have dedicated use it or lose it time off (OECD, 2023[42]).