Robust processes for selecting public investments are essential for countries to demonstrate to citizens that public resources are being allocated to the highest priority needs. This is critical at a time when countries must invest in low-emission and resilient infrastructure at an unprecedented pace and scale, within tight fiscal constraints. This chapter outlines best practice approaches for identifying projects that deliver the greatest outcomes while being efficient and affordable, and describes the processes followed by ministries and municipalities in Bulgaria.

Public Investment in Bulgaria

4. Project selection, prioritisation and appraisal processes

Abstract

The OECD Recommendation states that fiscal sustainability, affordability, and value for money are best achieved, in part, through:

“applying rigorous project appraisal and selection processes that pays due consideration to social and economic efficiency at the national and subnational levels (taking into account economic, social, fiscal, environmental and climate-related costs and benefits) and takes into account the full cycle of the asset, noting that for projects that exceed a high investment threshold it is especially important to provide a transparent, independent and impartial expert assessment to test project costing, fiscal sustainability, time planning, risk management and governance” (OECD, 2020[1])

4.1. Why is having quality project selection, prioritisation and appraisal processes important?

The systematic process of calculating the benefits and costs of policy options and projects is an essential step in the policy process. It helps decision makers have a clear picture of how society would fare under a range of policy options. This is particularly the case for the development and operation of infrastructure, which can be an important lever in delivering public outcomes and can determine the quality of people’s lives, including how and where the live, over many decades.

Project selection methodologies are about organising in a logical and methodical way information about a project and its impacts, while reducing the uncertainty that would otherwise exist around benefit estimates. Without these, decision-makers would be left to rely on their own intuitions and prejudices. Robust project selection methodologies ensure decision-makers can demonstrate that they have thought through the problems they are trying to solve, the benefits they are trying to achieve, the full range of options at their disposal, their plan for managing risks and all possible funding streams. A project selection process, captured in writing, can also provide an important public record to support why a particular decision was made.

While robust project selection methodologies should be applied to all public investments, they must be right sized for the scale and risk of the project while still meeting all relevant, globally adopted standards. For example, the level of analysis required will be different between a EUR 100 000 municipal water treatment plant upgrade project with few new environmental or social impacts and a EUR 1 billion multi-regional transport project with complex engineering and environmental risks which affect many stakeholders. A systematic method doesn’t necessarily need to be complex, detailed or expensive. Even a high-level calculation can be logical and methodical.

Cost benefit analysis (CBA) is the standard tool for assessing project worthiness by gathering information about the following:

Whether people’s wellbeing, welfare or utility, would be higher under a future scenario than the status quo

Whether people are willing to pay for a benefit and accept compensation for a cost

When the sum of all individuals’ benefits and costs are aggregated, whether the collective social benefit outweighs the social cost

Whether beneficiaries can hypothetically compensate the losers from a change, and have some net gains left over, which indicates that the benefits exceed the costs (OECD, 2018[2]).

While CBA has traditionally been used to monetise the benefits and costs of public investment proposals, it can also include wider economic benefits that are harder to monetise, such as peoples’ ability to access community services. CBA also commonly involves discounting benefits and costs to an agreed and consistently applied period, known as social discount rates. Box 4.1 describes how Norway applies a centrally mandated methodology for assessing projects against economic, social and environmental outcomes.

Box 4.1. Guidance on investment analysis in Norway

In line with best international practice, most transport projects in Norway undergo a thorough assessment of the positive and negative impacts, both directly on transport users but also on the economy and society. The requirements in terms of analytical work are set out in the government’s Instructions for Official Studies of Central Government Measures, which apply to all public spending proposals. The Instructions require that central government bodies conduct impact assessments during the development of investment proposals, and economic analyses for measures that are expected to give rise to major benefits or costs. As in most OECD countries, cost-benefit analysis (CBA) is used to rank alternative projects and alternative versions of the same project. In Norway, the CBA guidelines are embodied in a document called “Circular R-109”. The guidelines include requirements to account for the wider ramifications of transport projects using supplementary estimates and analysis, including environmental impacts.

In addition, projects with estimated costs in excess of NOK 1 billion (EUR 94.2 million) (threshold of NOK 300 million (EUR 28.2 million) for digitalisation projects) are subject to additional scrutiny via a two-stage quality assurance process. The process includes input from independent reviewers and was initially implemented to combat cost overruns. The process does not apply to the oil and gas sector, state-owned companies with responsibility for their own investments, and the hospital sector.

QA1 focuses on quality assurance of choice of concept. It is conducted prior to the Cabinet selecting projects. The central purpose of this analysis is to check, at a relatively early stage, that the project has undergone a process of “fair and rational” choice. It is conducted by the responsible ministry or government agency and includes investigation of alternative solutions, socio-economic impacts, and relevance of the project to needs. There is an emphasis on environmental and social impacts, land-use implications, and regional development. This evaluation, inter alia, must include a “do-nothing” option (“zero option”) and at least two alternative and conceptually different options. The external reviewers’ role includes analysis as well as review of documents.

QA2 focuses on quality assurance of the management base and cost. Its purpose is to check the quality of the inputs to decisions, including the cost estimates and uncertainties associated with the project, before it is submitted to Parliament to decide on funding allocation. It includes an assessment of cost estimates derived from basic engineering work and an assessment of at least two alternative contracting strategies. Notably, however, QA2 does not include revisiting and updating the cost-benefit analysis performed in QA1, unless the project seems to have been significantly altered from the option chosen at QA1. In addition, QA2 focuses on project management in the implementation phase.

Source: (OECD, 2017[3])

CBA is required for many facilities and funding schemes operated by the EC, including: the Connecting Europe Facility (CEF); European Structural and Investment Funds; InvestEU; the Recovery and Resilience Facility; the European Strategy Forum on Research Infrastructures; funding allocations from the European Investment Bank and the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development; and in national-level investment decisions (European Commission, 2021[4]).

The EC identified the common features of robust options analysis processes from a sample of around 250 major projects between the years 2014–2020, which serves as a useful checklist when reviewing project selection processes:

“Is drafted early enough in the project preparation stage (strategic level), continuously verified and adjusted as the preparation advances

is based on plausible criteria, set preferably by the relevant authorities for the entire sector to enable a level playing field for all projects (e.g. least cost or highest benefit approach)

these criteria should be formulated in a way that enables selection of the best option among relevant and feasible alternatives

applies these criteria in a transparent, verifiable and objective manner

is founded on a plausible demand analysis and based on reliable and verifiable historical demand and reasonable forecast demand

focuses on proper scoping out and scaling of the project, ensuring the best value for money

avoids gold plating of investments (i.e. the inclusion of physical elements and related expenditure that is not necessary to achieve the project objectives)

includes a technological option analysis, particularly in sectors where technology is relevant for selection of the final option (water, wastewater, waste treatment, research and development and productive investments) or where technology has a major impact on cost (transport).” (European Commission, 2021[4])

CBA can be complemented by other tools that help the project selection process. Examples include multi-criteria analysis, which applies the preferences of selected parties to a weighted criteria. Intervention logic mapping is another tool that helps define a problem, identifying possible interventions and each of the benefits that would address the identified problems.

4.2. What is the quality of Bulgaria’s project selection, prioritisation and appraisal processes?

Project selection tools, such as CBA and MCA, are common in Bulgaria. However, these tools are applied inconsistently at the national and local levels because ministries and municipalities develop their own project selection criteria and methods. This means decision-makers are not able to consistently compare investment proposals across portfolios to ensure they are allocating resources to the highest priorities across society. In addition, the driving criteria behind selecting projects in Bulgaria is ‘project readiness’, ‘urgency’ and the capacity to fund projects from year to year – these criteria do not help direct public resources to where they are needed the most.

Regarding the European level, the CBA criteria provided by the EC is commonly referred to by Bulgarian officials in the context of project selection. For cohesion policy-funded investments, the EC’s most recent guidance allows a “… flexible and proportional framework …” to be implemented, stating that tools such as CBA, MCA and CEA are “… proposed for voluntary use, based on sector and/or project type and scale ….” The EC adds that while CBA is the preferred approach, CBA can be resource-intensive so should be proportionate to the size, importance and risk of the investment (European Commission, 2021[4]).

At the national level, ministries and agencies must prepare what is described as a “CBA” as part of developing an operational plan for a project, but which in practice mostly focuses on addressing the needs identified in Bulgaria2030 rather than being a conventional CBA. The Operational Programme on Transport and Transport Infrastructure (OPTTI) 2014 – 20 programme is more directive, specifying that CBA must be applied to all projects valued above EUR 75 million tagged to the theme of “Promoting sustainable transport and removing bottlenecks in all key network infrastructures”. For projects tagged to “Supporting the transition to a low carbon economy in all sectors”, the threshold is EUR 50 million (Ministry of Regional Development and Public Works, Bulgaria, 2022[5]). OPPTI includes guidelines for how CBA should be applied. MRDPW also uses other project selection methodologies, such as MCA, when an evaluation procedure requires it. The Ministry of Finance also provides guidance for ministries when undertaking project selection for investments.

For municipal projects, the Ministry of Finance has developed a draft decree for the Council of Ministers to introduce uniform criteria for evaluating municipal projects funded by state funds. The decree will be considered for adoption by the new government once its appointed. This would be an exceptional case where project proposals are presented by municipalities against a uniform criteria mandated from the centre of government. A consistent criterion is something that national levels of government would welcome municipalities move towards.

Below are three examples of criteria for prioritising investments from three line ministries responsible for allocating funds to public investments. The first example is MRDPW’s criteria for assessing roading projects:

“Relevance to strategic objectives set out in strategic documents at the national, sectoral and regional levels

Potential to lift economic development in a particular area, or is the only link to a particular settlement

Role in providing connectivity and resilience to a larger network

Alignment with the strategic objectives of European and/or international institutions

Relevance to national security

Congestion volumes

Return on investment and the ability to mobilise financial resources, such as tolling of freight traffic

State of urgency

State of readiness

Compliance with estimated budget ceilings [emphasis added].” (Ministry of Regional Development and Public Works, Bulgaria, 2022[5])

The Ministry of Education and Science’s criteria for assessing applications for renovation works for municipal educational buildings is as follows:

“Eligibility criteria - the applicant has not received Investment Program funding in the past 2 years, outside of emergency or urgent repairs and transitional (from a previous year) construction and repair work completed to complete the required technological sequence of work.

In cases of emergency and urgent repairs:

Importance of the renovation for the normal conduct of the educational process and for the protection of the life and health of students and teaching and non-teaching staff;

Number of students.

In the case of all other types of repairs:

A prescription from the controlling authorities that would lead to the closure of the whole institution or some part that directly concerns the educational process;

Need for the requested repair;

Type of repair, with priority given to roof leaks or heating, ventilation, air conditioning (HVAC), plumbing and electrical problems;

Compliance with the annual thematic priority of the Ministry of Education for creating healthy and quality working and learning conditions;

Completed phases (from previous year) of construction and renovation activities to complete the required technological sequence of works

Number of students;

Social and economic benefits of the project/proposal.” (Ministry of Education and Science, Bulgaria, n.d.[6])

The Ministry of Finance’s criteria for assessing applications from municipalities for capital expenditure from central budget funds includes applying weighted scores to the following criteria:

“The condition of the current site;

The proposal’s justification, including its expected effects on users and “importance”;

The proposal’s objectives, including its contribution to economic development, improving the “living environment” and improving the specific activity or service;

The capacity for the respective municipalities to manage the project and the identified risks;

The accuracy of the proposed delivery period;

“Justification” of the proposal, including whether it has links to other funded projects, its potential for employment

Previous disbursements of capital expenditure from the central budget from the previous three years;

Eligibility for EU funding;

Potential for raising revenue.” (Ministry of Finance, Bulgaria, n.d.[7])

While these three criteria lists attempt to measure the impact and benefits of investment proposals, they also include criteria like “urgency”, “readiness” and capacity to fund projects from year to year. Criteria like this does not help decision-makers determine whether public resources are being allocated to the highest need. Also, without tight definitions around criteria like “urgency” and “readiness”, there are insufficient safeguards against internal bias, corruption and fraud. Prioritising investments on the basis of “urgency” may be acceptable if to prioritise the reinstatement of critical infrastructure after a crisis, such as reinstating a bridge on a critical transport route that has collapsed due to flooding. However, in this case, this meaning of “urgency” must be clearly defined. In addition, while there may be an immediate pressure in a crisis to reinstate the previous infrastructure, a crisis can also be an appropriate opportunity to revisit whether the previous infrastructure is performing at the level it should be, or whether a different investment would deliver greater resilience and other benefits. More frequent and severe storm events and rising sea levels are causing infrastructure providers to revise the levels of resilience needed, which makes it important to review whether previous infrastructure, which may have been suitably resilient in the past, will deliver the necessary level of resilience in the future as climate change unfolds. Box 9 provides a useful demonstration of how the benefits and costs of investment in resilience can be calculated to compare the benefits and costs of a status quo options with a more resilient alternative.

In terms of assessing the quality of how CBA is being applied, in recent times Bulgaria has relied on JASPERS’ assessment for major projects.

Even for projects that have received relatively detailed project selection analysis, they are not always following EU best practice. For example, we found an example of a major EU-funded transport project where a multi-criteria assessment was used to select the preferred option. However, this is inconsistent with EU requirements, which state that multi-criteria analysis can be used for shortlisting alternatives, while cost-benefit analysis should always be applied to all shortlisted options (European Commission, 2014[8]).

Regarding EU-funded municipal projects, there is a view among some of the interviewed officials that EU-funded projects do not necessarily go to the highest priorities, which may lead under-resourced municipalities to pursue the sources of funding rather than pursue projects that address the highest needs. Officials described how this is not the case in sectors where there is clear strategic direction from national government, which helps direct EU funds to investments that have high levels of project worthiness. However, many infrastructure sectors do not have clear strategic direction at the national level.

Overall, some public infrastructure providers could be thinking more holistically about the infrastructure solutions available to them. For example, one ministry with a significant infrastructure portfolio raised a tension between delivering green objectives and addressing traffic congestion, suggesting the two were mutually exclusive. However, there are a wide range of infrastructure solutions that could address congestion while also helping Bulgaria meet its green and digital objectives, such as investment in public transport to reduce the use of private vehicles or digital communications to replace the need for vehicle travel. Examples like this show infrastructure providers need to think through the problems they are trying to solve and consider the widest possible set of options, which is what the model described in Box 2.1 and a robust project selection methodology can help infrastructure providers do. To demonstrate the wide range of options available, Box 4.2 gives an example of how the city of Milan, Italy has developed a programme of innovative measures that meet people’s transport needs while contributing to carbon reduction targets and avoiding new capital and operational investment.

Box 4.2. Innovative ways of managing demand on infrastructure in Milan, Italy

The City of Milan has introduced innovative ways of reducing demand on its transport network. By focusing on the outcomes that citizens seek from their transport network, and not automatically defaulting to traditional solutions to transport problems, Milan has developed a programme of innovative measures that improve the transport network while contributing to international climate commitments without putting new pressure on capital and operational budgets.

In 2020, Milan launched the Adaptation Strategy, which sets comprehensive demand-side actions to reduce travel demand (e.g. promoting smart and remote work models); improve and diversify mobility options (e.g. promoting bicycles, electric scooters, shared vehicles); increase public transport safety (e.g. limiting the number of people in public buses and subways, reducing crowds at bus stops and train stations with safety distancing); clear sidewalks; integrate public transport with other mobility systems; enhance automation of transport and parking tickets and passes; and to invest in short-term parking spaces (e.g. for delivery of essential goods for healthcare and emergency services).

The Strategy also aims to rethink the timing, timetables and the rhythm of the city, to maximise flexibility and spread the mobility demand over time, encouraging more flexible timetables for schools and workers, and extending opening hours of services and businesses, as well as live cultural performances. It also intends to reclaim public spaces for wellbeing, leisure, and sports, with a gradual reopening of parks and sport facilities.

Source: (Comune di Milano, 2020[9])

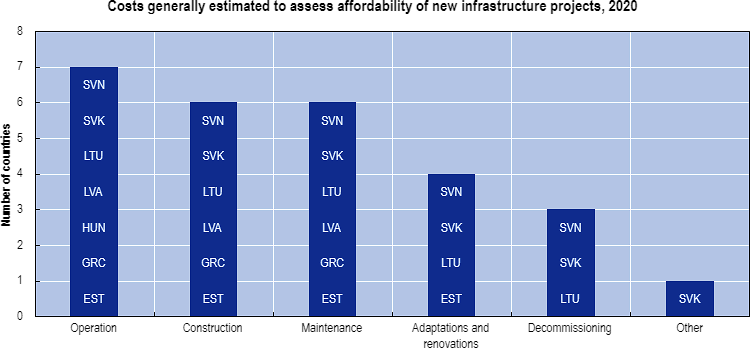

To understand the full-long-term benefits and costs of a selected project, it is important to include the full lifecycle costs within the appraisal. Without this information, it is not possible to appraise the project’s expected benefits and costs across the full duration of an asset’s life. But consideration of lifecycle costings in Bulgaria is rare: the only requirement that exists for lifecycle costs is that, under EU and Bulgarian law, procuring authorities can identify cost effectiveness, including lifecycle costs, amongst other measures, as a reason for selecting a particular contractor (Republic of Bulgaria, 2016[10]). Often, the focus regarding cost during the planning phase is the capital cost (i.e. the cost up until the point that the project is operational). Maintenance costs come from the current expenditure of the responsible agency, which is separate from the capital allocated to delivering specific infrastructure programmes or projects. This means the full lifecycle cost of a project cannot be easily forecast. At the municipal level, some municipalities do forecast maintenance and operational costs of projects when determining capital costs. However, most municipalities in Bulgaria still do not do this. Figure 4.1 shows that estimating costs across the lifecycle is common across many other OECD European countries.

Figure 4.1. Lifecycle costing by selected European OECD countries

All investment proposals in Bulgaria are potentially subject to environmental impact assessments (EIA), to identify potential environmental and human health impacts from the construction and operations of projects while also considering climate mitigation and adaptation considerations. Environmental authorities assess project proposals to determine whether an EIA is needed. EIAs take place before a decision is taken to build a project in a particular location. Pre-investment studies, which includes a technical assessment of different locations of physical assets or routes, consider the terrain, topographical features, climatic manifestations and land use constraints, such as the location of protected areas and development zones. Feasibility studies are also required for projects funded by EU Structural funds only. There are also requirements for projects in Bulgaria to improve access for people with disabilities, to comply with the National Employment Strategy for People with Disabilities 2011 – 2020 and the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. New buildings must be audited for their energy efficiency under the Energy Efficiency Act, which can result in the audit recommending alternative packages of measures. EU-funded projects must also meet requirements regarding climate change and comply with the EU’s ‘Do No Significant Harm’ principle (European Commission, 2021[12]) and other environmental considerations as set out in initiatives such as the EU Green Deal, Recovery and Resilience Plan and the Digital Transition objectives.

The Ministry of Finance’s guidelines for project selection are generalised, and do not include criteria for including green or digital investments. Criteria of this kind would need to be developed from within the line ministries. Box 4.3 is an example of how Italy has included green considerations into its project selection process.

Box 4.3. Italy’s innovative reforms to take account of the benefits of green infrastructure

In 2021, Italy’s Ministry for Sustainable Infrastructure and Mobility introduced a new criteria for planning and evaluating infrastructural projects, which placed great focus on environmental sustainability, along with economic, social and governance dimensions.

The Ministry introduced a new scoring system that encompasses multiple criteria and aims to prioritise different projects eligible for public funding. The scoring system encompasses four dimensions (economic-finance, social, governance and environment), which are broken down into subdomains with specific components of analysis, indicators, and qualitative information.

The Ministry also designed new guidelines for the ex-ante valuation of projects measuring the environmental impacts, together with operational guidelines specific to the railway, public transports, and road sectors. The new guidance is designed to be consistent with the European Taxonomy Regulation contained in the Delegated Regulation by the EU and the do-no-significant-harm (DNSH) principle.

The Ministry also published new guidelines for the Technical and Economic Feasibility Projects which include a study on the environmental impact of project and a sustainability report.

Source: (OECD, 2020[11])

Geoprotection from natural hazard events, such as landslides, is a significant focus for the national government. Activities in response to natural hazard events are not subject to cost benefit analysis, but instead subject to criteria that consider the number of people affected, size of the affected asset(s), the overall impact of the natural hazard event and project readiness. Based on these criteria, MRDPW allocates funding to municipalities for activities that address resilience. Worldwide, project appraisal tools are used to assess the present and future benefits and costs of resilience projects, such as the reinstatement of infrastructure after landslips. Factors like the frequency of natural hazard events and the costs to people’s lives, businesses or access to essential services can be weighed up to help decision-makers consider a wider range of options in response to natural hazard events. For example, cost benefit analysis can be used to decide whether a like-for-like replacement of an asset is the best approach, or whether a solution that will be more resilient over the long-term can generate greater or fewer benefits. Understandably, natural hazard events can happen quickly and there is a need for emergency service operators and infrastructure providers to move quickly to reinstate infrastructure so people’s lives can resume. But rather than waiting for natural hazards to strike, project appraisal can be applied to at-risk sites outside of times of emergency, in anticipation of future natural hazard events. Box 4.4 shows a methodology from New Zealand, a country highly exposed to natural hazard risk, for monetising the benefits of resilience.

Box 4.4. Measuring the benefits of resilience in New Zealand

New Zealand is especially prone to events like earthquakes, volcanic activity and extreme weather events causing floods and landslides.

To help identify projects with greater resilience, the New Zealand Transport Agency has developed a methodology for monetising the benefits of resilience. In this methodology, the resilience benefits are estimated against the non-disrupted state. If options are being considered with different levels of resilience, then the value of an option relative to base can be assessed as:

Value of option relative to the base case =

net change in benefits in non-disrupted state plus

net change in benefits of resilience

Where:

Net increase in benefits of resilience = Net reduction in expected costs of disruption

expected costs of disruption under the Base Case minus

expected costs of disruption under the Option.

For example, flooding causes annual costs of disruption of EUR 1 million along an existing route. An alternative route is being considered that provides transport cost savings valued at EUR 3 million per year. The new route is also subject to some flooding, but the annual cost of disruption is estimated to be EUR 0.4 million. The annual benefits of the alternative route relative to the base case are then estimated as EUR 3.6 million (EUR 3 million plus a EUR 0.6 million reduction in disruption costs).

The methodology also factors in a wider range of costs and impacts, including: user costs (diversion, waiting times; other direct costs (loss of life, injury, repair and reinstatement) and; indirect impacts (wider economic benefits).

References

[9] Comune di Milano (2020), Milan 2020 Adaptation Strategy, https://www.comune.milano.it/documents/20126/7117896/Milano+2020.+Adaptation+strategy.pdf/d11a0983-6ce5-5385-d173-efcc28b45413?t=1589366192908.

[4] European Commission (2021), Economic Appraisal Vademecum 2021 - 2027: general principles and sector applications, https://jaspers.eib.org/knowledge/publications/economic-appraisal-vademecum-2021-2027-general-principles-and-sector-applications?documentId=561.

[12] European Commission (2021), Technical guidance on the application of ‘do no significant harm’ under the Recovery and Resilience Facility Regulation, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A52021XC0218%2801%29.

[8] European Commission (2014), Guide for Cost Benefit Analysis of Investment Projects for Cohesion Policy 2014-20, https://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/sources/studies/cba_guide.pdf.

[6] Ministry of Education and Science, Bulgaria (n.d.), Rules and Criteria to Work on the Implementation of the Investment Programme of the Ministry of Education and Science for Renovation Works.

[7] Ministry of Finance, Bulgaria (n.d.), Project Selection Procedure Municipalities’ Proposals for Central Budget Funding.

[5] Ministry of Regional Development and Public Works, Bulgaria (2022), Response to ‘An Overview of Public Investment Planning and Decision-making in Bulgaria, Part B: questionnaire for line ministries’.

[13] New Zealand Transport Agency (2020), Better Measurement of the Direct and Indirect Costs and Benefits of Resilience, https://www.nzta.govt.nz/assets/resources/research/reports/670/670-Better-measurement-of-the-direct-a.

[11] OECD (2020), Infrastructure Governance Indicators.

[1] OECD (2020), Recommendation of the Council on the Governance of Infrastructure, https://legalinstruments.oecd.org/en/instruments/OECD-LEGAL-0460.

[2] OECD (2018), “Environmental cost-benefit analysis: Foundations, stages and evolving issues”, in Cost-Benefit Analysis and the Environment: Further Developments and Policy Use, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264085169-5-en.

[3] OECD (2017), OECD Economic Surveys: Norway 2018, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/eco_surveys-nor-2018-en.

[10] Republic of Bulgaria (2016), Article 70, paragraph (1), Public Procurement Act (introducing article 67, paragraph (2) of Directive 2014/24/EU).

Note

← 1. . Note: Hungary did not reply to the opportunity for their data responses to be validated.