This chapter analyses how Germany manages human resource capital in its public procurement system. German civil servants benefit from solid education and training. However, the current approach to civil service in Germany is to train and employ a workforce of generalists, while expected challenges in the coming years will require increasingly specialised public procurers. To realise the fullest impact of public procurement, Germany could take a strategic approach to establishing public procurement as a profession. Developing systematic training for public procurers could allow for further specialisation and enable procurers to meet the challenges of increasingly complex strategic procurement processes.

Public Procurement in Germany

6. The human resource capital of the German public procurement system

Abstract

The statistical data for Israel are supplied by and under the responsibility of the relevant Israeli authorities. The use of such data by the OECD is without prejudice to the status of the Golan Heights, East Jerusalem and Israeli settlements in the West Bank under the terms of international law.

Like any governmental activity, the outcomes of public procurement depend on the capacities of the people implementing it. As such, equipping public procurers with the necessary capabilities is paramount to achieving the objectives of public procurement.

In Germany, a general tension exists between two aspects of its public administration. On the one hand, the country’s increased push towards strategic procurement and greater centralisation of procurement requires highly specialised procurement experts. On the other hand, the traditional and proven approach to human resource management in the German civil service is built on generalists and like most German civil servants, procurement officials tend to be generalists. This chapter explores how these two approaches can be combined most beneficially.

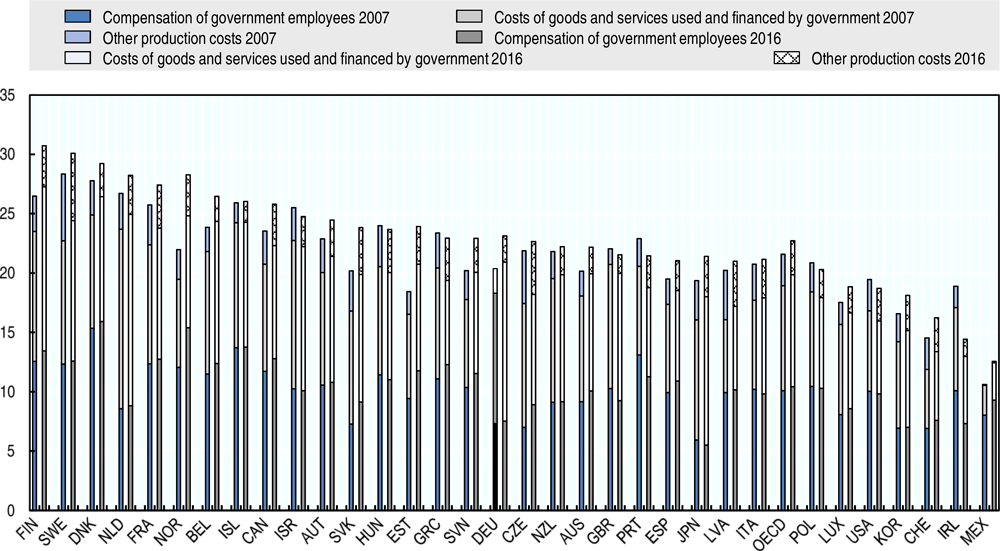

Like many other countries, Germany faces the challenge of achieving the best value for money from its civil service. In light of this challenge, OECD member countries are placing an increased focus on the economic impact of their public services. In the last decade, the majority of OECD countries has faced rising costs for the delivery of their services. Compensation of government employees accounts for the majority of these increased expenses (see Figure 6.1). In finding ways to address this situation, many countries aim at increasing the effectiveness of their civil servants, while at the same time attempting to reduce their costs (OECD, 2016[1]).

Figure 6.1. Government production costs, 2007 and 2016

Note: Data for 2016 where available. Data for Israel, New Zealand, Australia, Japan, United States, Switzerland, Korea and Mexico are for 2015 rather than 2016. Data for Chile and Turkey are not included in the OECD average because of missing time series or main non-financial government aggregates. Data for Australia are based on a combination of national accounts and government finance statistics data provided by the Australian Bureau of Statistics.

Source: OECD National Accounts Statistics (database) as adapted from (OECD, 2017[2]), Government at a Glance 2017, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/gov_glance-2017-en.

While some countries cut costs following the economic crisis of 2007 and 2008, at present most countries need to increase efficiency to ensure that public procurement maintains a positive economic impact. Public procurers’ expenses are counted as a part of the compensation for officials. In addition, procurers’ effectiveness impacts the remainder of the production cost. The economic impact of any public procurement depends highly on the individual capacity of public servants to implement procurement processes in a smart way. Capacity building for public procurers is therefore central to achieving value for taxpayer money. Procurers today often manage complex processes that require broader knowledge than the knowledge that allows them to achieve legal and regulatory compliance. Decision making to account for complementary policy objectives, for example, requires the use of more strategic approaches (OECD, 2017[3]). In addition, evidence shows that guidance and training of procurement officials ensures that procurers use available centralised purchasing options more frequently and more efficiently. This training and guidance can therefore help countries achieve the economic goals associated with centralisation efforts in the area of public procurement (Kauppi and van Raaij, 2015[4]).

Because Germany’s procurement system has procuring entities at several levels of government, disseminating skills throughout the system is one way to ensuring high performance across the board. New Zealand’s experience in implementing a capacity strategy could be a model for Germany. New Zealand’s capacity strategy was built on the insight that it was not possible to centralise all procurement. As a consequence, New Zealand worked to increase the skills of state-level agencies and to provide guidance to state-level procurement staff.

Besides above-mentioned incentives related to cost savings from increased capacity of procurers, studies have demonstrated that structured and specialised human resource management of the public sector is vital to improved public procurement. A more meritocratic public procurement workforce contributes to lower levels of corruption – which means a lower risk of public funds going to waste (Charron, Dahlström and Lapuente, 2017[5]).

The OECD Recommendation of the Council on Public Procurement emphasises that capacity building and professionalisation of public procurement are important to maintaining the effectiveness of the public service. Furthermore, the recommendation includes capacity as one of the principles of an effective public procurement system. According to the recommendation, three features define public procurement capacity (OECD, 2016[6]; OECD, 2015[7]):

high professional standards for knowledge, practical implementation and integrity

attractive, competitive and merit-based career options specifically for public procurement officials

collaborative approaches with knowledge centres.

Box 6.1 details the OECD Recommendation of the Council on Public Procurement’s principle on capacity.

Box 6.1. OECD Recommendation of the Council on Public Procurement – principle on capacity

The Council:

RECOMMENDS that Adherents develop a procurement workforce with the capacity to continually deliver value for money efficiently and effectively.

To this end, Adherents should:

i) Ensure that procurement officials meet high professional standards for knowledge, practical implementation and integrity by providing a dedicated and regularly updated set of tools, for example, sufficient staff in terms of numbers and skills, recognition of public procurement as a specific profession, certification and regular trainings, integrity standards for public procurement officials and the existence of a unit or team analysing public procurement information and monitoring the performance of the public procurement system.

ii) Provide attractive, competitive and merit-based career options for procurement officials through the provision of clear means of advancement, protection from political interference in the procurement process and the promotion of national and international good practices in career development to enhance the performance of the procurement workforce.

iii) Promote collaborative approaches with knowledge centres such as universities, think tanks or policy centres to improve skills and competences of the procurement workforce. The expertise and pedagogical experience of knowledge centres should be enlisted as a valuable means of expanding procurement knowledge and upholding a two-way channel between theory and practice, capable of boosting application of innovation to public procurement systems.

Source: (OECD, 2015[7]), OECD Recommendation of the Council on Public Procurement, http://www.oecd.org/gov/ethics/OECD-Recommendation-on-Public-Procurement.pdf.

Besides the OECD Recommendation, an additional international standard on public procurement highlighting the importance of procurement professionalization is the Methodology for Assessing Procurement Systems (MAPS). MAPS is a methodology to assess public procurement systems as a whole. The methodology includes indicators on capacity to ensure that a given system has the means to achieve its procurement objectives. MAPS links the capacity of the public procurement workforce with the capacity of the entire procurement system, and more specifically with the system’s ability to develop and improve procurement performance. The MAPS “suite” includes a supplementary module on professionalisation that allows for a focused analysis of this important subject area. (MAPS, 2018[8])

To support these overarching concepts with concrete measures, international best practices include the following elements of a system to promote public procurement capacity building (OECD, 2016[6]).

strategies to outline capacity building and professionalisation activities, supported by a concrete action plan that outlines steps for implementation

tools to define and track roles and associated knowledge or skills, such as competency frameworks, job profiles and certification systems

clear responsibilities (i.e. who is in charge of capacity building with regards to public procurement specifically)

tools and activities to increase the knowledge or skills of the public procurement workforce (i.e. training)

incentives, including a definition of a clear career trajectory combined with attractive and merit-based remuneration and progression

analytical systems to identify needs and monitor impact

adequate financial resources for capacity-building activities

advisory services or help desks

exchange with knowledge centres outside of public procurement institutions.

This chapter takes stock of Germany’s management of procurement human resources to identify areas where good practices can be expanded to achieve greater impact. First, the chapter analyses the status of public procurement as a profession in Germany, in line with the OECD recommendation and international good practices. Second, the chapter discusses opportunities for increasing performance through monitoring and evaluation. Third, the chapter explores avenues for building the capacity of public procurers in Germany. Finally, additional sections illustrate the professionalisation of public procurement at the sub-national level, and summarise areas for action.

6.1. Considering public procurement as a profession

In Germany, most matters related to human resource management and the professional status of public procurers follow the general employment rules of the civil service. As such, only limited considerations exist that are specific to procurers. This sub-section of the chapter explores the general framework of the civil service under which public procurers are hired and managed. The chapter then proposes measures that could serve to professionalise the procurement workforce within the overarching framework.

The professionalisation of public procurement encompasses several activities. These activities all strive to 1) make public procurement a dedicated profession that is considered separately within a country’s civil service (MAPS, 2018[8]); and 2) to make public procurers more professional (that is, increasing the individual and systemic capacities of public procurers.) Countries increase individual and systemic capacities by using measures like training, guidance and more (MAPS, forthcoming[9]).

In October 2017, the EU adopted a recommendation on the professionalisation of public procurers as a part of its public procurement package. Given the strategic importance of public procurement and its ability to influence policy outcomes, the recommendation aimed at increasing the professionalism with which officials in the EU purchased goods, works and services. The recommendation suggested that EU countries tackle professionalisation of public procurement using the following three avenues (European Union, 2017[10]):

1. policy architecture – create a strategy to increase the professionalism of public procurement;

2. human resources – provide training and a career path for public procurers;

3. systems – supply structured tools, methodologies and processes to support the professionalisation of public procurement.

The concrete steps outlined by the EU recommendation can inform a capacity-building strategy, as the three domains highlighted by the EU affect capacity. The EU recommendation, issued by one of the most important standard setters in the area of public procurement, illustrates the immense importance of building procurers’ capacities. Around the world, other institutions are following a global trend by embarking on a push for greater professionalisation of public procurement. The World Bank, for example, has organised co-ordinated professionalisation activities for interested countries, ranging from training to guidance.1

6.1.1. Germany’s public procurement workforce belongs to the country’s civil service, which follows a generalist model

This section examines the profile of the average public procurer in the German federal administration, and to what extent there is room to hire entrants with characteristics that are conducive to becoming successful procurers. In the context of Germany’s increasing emphasis on strategic and centralised procurement, a specialisation-focused model of human resource management in public procurement will be needed. Only with the right skills can public procurers meet the upcoming challenges.

Specialisation in public procurement can help officials from diverse backgrounds achieve procurement objectives. New entrants to the job should have the necessary education to be successful public procurers. Setting clear expectations for these officials can help them succeed. Once these baselines are established, specialisation can be achieved in different ways. The civil service can establish dedicated career paths, give officers training and offer experience to officials by assigning them to dedicated procurement-related posts. International good practices consider specialisation to be an important aspect of a professional public procurement workforce (European Union, 2017[10]; MAPS, 2018[8]; OECD, 2015[7]).

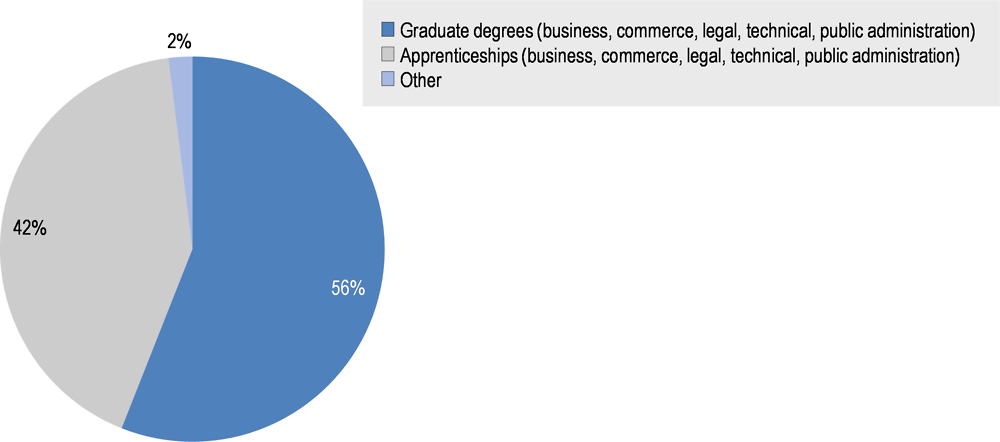

Germany’s public procurement workforce is diverse – especially with regard to the profiles of individual procurers. A 2015 academic survey revealed that public procurers in Germany have a variety of educational backgrounds, but limited educational specialisation in public procurement. This diversity is not surprising, considering that there is no dedicated profile for public procurers in Germany, and procurers are hired from within the general public service. Furthermore, just over half of procurers have conducted degree-level studies in the country; roughly the other half have conducted an apprenticeship, as illustrated in Figure 6.2.

Figure 6.2. Educational background of public procurers in Germany: Level of education

Note: Figure represents responses to an academic survey of German procurers. The survey looked at innovation procurement. Researchers received 453 responses, with multiple responses possible.

Source: Unpublished survey data from (Eßig and Schaupp, 2016[11]), Erfassung des aktuellen Standes der innovativen öffentlichen Beschaffung in Deutschland – Darstellung der wichtigsten Ergebnisse, https://www.koinno-bmwi.de/fileadmin/user_upload/publikationen/Erfassung_des_aktuellen_Standes_der_innovativen_oeffentlichen_Beschaffung....pdf.

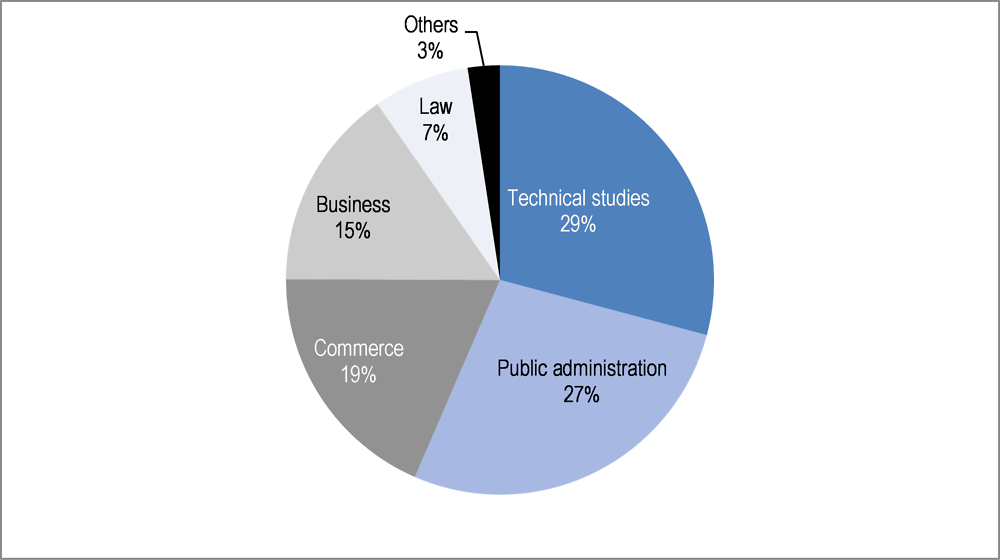

The educational background of public procurers in Germany is diverse in terms of field of specialisation. A majority of respondents to the academic survey discussed above received education in a technical area (i.e., specialisation in a specific topic) or in general public administration (see Figure 6.3.).

Figure 6.3. Educational background of public procurers in Germany: Fields of education

Note: Figure represents responses to an academic survey of German procurers. The survey looked at innovation procurement. Researchers received 453 responses, with multiple responses possible.

Source: Unpublished survey data from (Eßig and Schaupp, 2016[11]), Erfassung des aktuellen Standes der innovativen öffentlichen Beschaffung in Deutschland – Darstellung der wichtigsten Ergebnisse, https://www.koinno-bmwi.de/fileadmin/user_upload/publikationen/ Erfassung_des_aktuellen_Standes_der_innovativen_oeffentlichen_Beschaffung....pdf.

The results of the survey above seem to be representative for the majority of public procurers in Germany. According to stakeholder interviews, in Germany’s general customs administration, for example, general customs officers who have gathered experience from dedicated training and “learning by doing” conduct procurement. Furthermore, a separate technical service (Technischer Dienst) is tasked with market analysis. Leadership positions are often filled by lawyers. Recently, however, the leadership level has gradually become open to applicants from other backgrounds.

In Germany, public procurement is part of the general training that new entrants to the general public service receive, though to a limited extent. While it is possible to enter the public service laterally (i.e., from a position outside of the public service or from other government posts), a large number of officials at the federal level enter the public service by studying at the Federal University of Applied Administrative Sciences (Hochschule des Bundes für öffentliche Verwaltung, HS Bund). HS Bund offers several programmes equivalent to both bachelor’s and master’s studies that prepare students for a career in the civil service of the federal administration. About 50% of new entrants to the civil service at the federal level graduated from the HS Bund. Aside from several specialisations like IT engineers or meteorological studies, HS Bund has a programme of general studies. This general programme aims at educating officials so that they are able to successfully work in a variety of tasks across the federal administration.

HS Bund features public procurement in most of its programmes, including its general civil service programme and information technology (IT) engineering in the context of e-procurement. Students enrolled in general civil service programmes study procurement for only a few lessons. These lessons combine legal studies and practical examples. This amount of training provides a general overview of public procurement. It is mandatory for all students who are likely to come into contact with public procurement as a part of their specialisation.

Several professors and lecturers teach procurement at HS Bund, both at the bachelor’s and master’s level. The emphasis of the training is on procurements whose value is below the thresholds set by EU rules, as this is the type of procurement that is most often conducted by regular officials. However, this training is not usually sufficient to enable officials to conduct procurement once they arrive in a procurement position later in their career. Thus, officials often need additional training.

It is possible to informally specialise in public procurement as a part of one’s general civil service studies, depending on personal interest within the existing tracks. However, there are no recommendations or guidance as to the kinds of studies a public procurer should undertake, or as to how this specialisation can be used to build a compelling career. Officials with an interest in specialising in public procurement are often highly valued in their administrations, as not many officials have this profile.

Some specialisation happens on an ad hoc basis when individuals decide to continue focusing their career on public procurement. However, in Germany there is no structured procurement career path for officials to embark on at the beginning of their careers, and no structured planning around procurement personnel. For example, procurers in Germany’s central purchasing unit for IT procurement do specialise in procurement – but not so much with regard to the type of procurement they conduct or the type of products they purchase. The goal in the unit is to be able to distribute procurement cases across the team, depending on workload.

The approach of specialisation according to the individual interests of civil service professionals may not serve Germany’s current needs. Increased bundling of public procurement in the country has resulted in more complex procurement, requiring appropriately skilled procurers in every procurement authority conducting centralised procurement. Increased emphasis on strategic procurement means that procurement processes are becoming increasingly challenging for procurers, as they are required to take into account aspects beyond price, as well as more complex technical specifications. In addition, sustainability issues are becoming a priority in German public policy. Sustainability is often linked to the technical aspects of procurement – and must be understood by procurers. While more specialised education can help ready procurers for these challenges, an emphasis on legal compliance in the education of public servants does not provide necessary knowledge.

To ensure that those in a procurement function have a minimum level of capacity, establishing sample role descriptions or profiles for procurers could be useful. These profiles could be established by an institution at the federal level and could be taken up by contracting authorities as needed. The profiles should establish minimum requirements for the education, experience and skills a procurer has to have for each specific level of responsibility. These sample role descriptions could then provide guidance for hiring within contracting authorities, and could form the basis for a more structured procurement career path where relevant. The EU is working to implement these types of practices. As a part of the implementation of its recommendation on procurement professionalisation, the EU is now preparing a Competency Framework for public procurement. The Competency Framework will define core functions and competences of public procurers and will be applied to EU member states.

6.1.2. Strategic procurement: The challenges faced by public procurers

Like procurers in many other countries, Germany’s public procurers face challenges stemming from an increasingly complex policy framework. Germany’s 2016 procurement reform brought new rules regarding how public procurers must conduct their work. Adapting to these new rules has been challenging, but procurers face other, broader challenges as well. These broader challenges include increasing demands for strategic procurement, such as the incorporation of complementary policy objectives into procurement processes. In addition, the increased push for centralised public procurement in Germany has changed the types of skills individual procurers must possess. This development began before the reform.

Challenges facing procurement officials in Germany relate to different aspects of public procurement. On a very general level, stakeholders interviewed for this study reported that they saw procurement as an administrative burden that was best to be avoided at all costs. This attitude contrasts with the international trend to consider the public procurement function a strategic role within the government that can exert considerable influence and promote policy objectives. Strategic procurement requires skilled use of complex selection and award criteria. Unfortunately, the skilled use of selection and award criteria does not always take place. Procurers in smaller entities face greater challenges given that they rarely possess a combination of strong technical knowledge and high-level knowledge of the public procurement process.

As a part of the monitoring of the implementation of the 2014 EU directives on procurement, the German federal government asked institutions at the federal and sub-national levels to flag any problems with implementing Germany’s 2016 public procurement law. While state institutions flagged the majority of problems, some federal institutions also recorded certain issues. Notably, federal contracting authorities and requesting units had insufficient personnel to handle the increasingly complex administrative requirements of public procurement processes. In addition, authorities noted that companies had limited interest in participating in procurement opportunities, which resulted in limited competition in tenders (Bundesregierung, 2017[12]). Procurement appeals courts have yet to issue rulings related to the 2016 procurement law, but challenges point to issues that could have been addressed with more practical training. For example, bidders have challenged contracting authorities’ use of functional specifications without a transparent evaluation system. Instead of developing and publishing clear and detailed selection and award criteria, the procurers provided a simple system that only had broad categories. (The categories were: offer complies with the needs fully, offer complies with minor gaps, offer complies with large gaps, and more). (Bundeskartellamt, 2017[13]).

In early 2016, the European Commission published a study on member countries’ administrative capacities in the area of public procurement. According to this study, Germany’s public procurement authorities made less use of the most economically advantageous tender criteria (MEAT criteria) in procurement above the EU threshold. At the same time, German procurement authorities made more use of the simpler, price-only criteria for procurement. In 2014, Germany used the MEAT criterion in 48% of its procurement cases2. In contrast, France used the criterion in 96% of its procurement processes and the Netherlands used it in 90% of its procurement cases (European Commission, 2016[14]). These figures illustrate that there is a large potential for further improvement of strategic procurement in Germany. Finally, interviews with German officials have shown that smaller contracting authorities with lower capacities struggle to implement more complex procurement procedures like the MEAT criterion (albeit especially on the sub-national level.)

These findings point to a situation in which there is a disparity in performance in the German public procurement system. Case studies, such as those throughout this review, show that excellent performers exist in the German public procurement landscape. However, others lag behind, especially in the periphery of the system (i.e. in smaller contracting authorities, as well as at the state and municipal levels). As outlined above, according to the limited information available about the level of professionalization of public procurers in Germany, many procurement officials have gaps in areas that should be part of the general public procurer’s toolbox. While contact points and support exist for specialised procurement processes (i.e. for sustainable procurement and innovative procurement), there is no such competence centre or contact point for the average, but complex procurement case. In some institutions, a contact point with resources for procurement officials might exist in-house. Weaker institutions, however, often do not have public procurement advisors who provide guidance and support for complex cases. In addition, no institution exists in Germany that could monitor the evolving challenges of procurers and propose support mechanisms accordingly.

6.1.3. Germany’s public procurement workforce is large and requires specialised human resource management

The ways the German public procurement workforce and its human resource management are structured can shed some light on the origins of the challenges facing the country’s procurement system. As mentioned above, Germany faces an increasing need for public procurers with specialised skills. Germany has a large procurement workforce. This means that increasing skills across the entire workforce will require a strategic approach. Increased visibility of the structure of Germany’s public procurement workforce will be instrumental in designing this strategic approach.

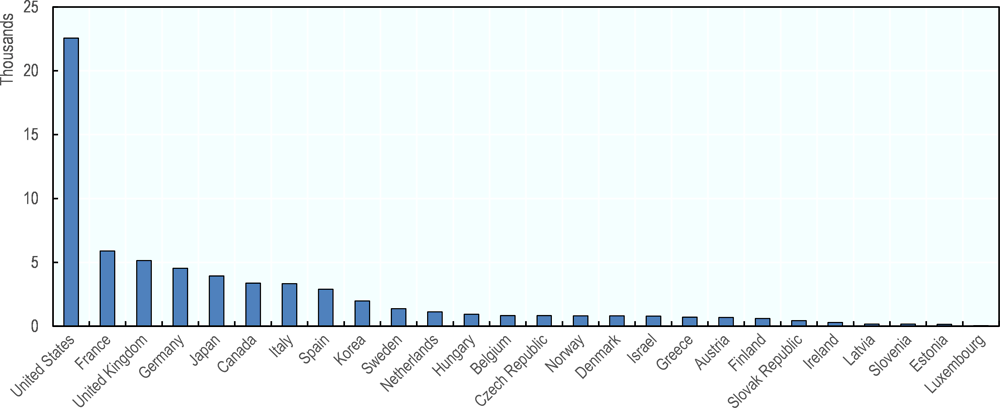

Germany has one of the largest civil services in the OECD. In 2016, 4.69 million people worked in the public sector in Germany at all levels (federal, state, municipalities and social security institutions). See Figure 6.4 for a comparison of employment in the civil services of a subset of OECD countries.

Figure 6.4. Employment in general government: Number of persons, thousands (2015)

Note: Data for Japan, Switzerland, Turkey and the United States are from the International Labour Organization (ILO)’s ILOSTAT database. Public employment by sectors and sub-sectors of national accounts. National authorities provided data for Korea. Data for Canada are estimated values.

Source: OECD National Accounts Statistics (database).

Only about 10% of German officials work at the federal level. This small percentage demonstrates the significance of the share of public service provision that is borne by the sub-national levels of government in Germany. With this rate, Germany has one of the most decentralised civil services in the OECD, as illustrated by Figure 6.5.

Figure 6.5. Percentage of government staff employed at the central level in Germany, 2014

Note: Social security funds are not separately identified (i.e. recorded under central or sub-central governments) for Canada, Estonia, Ireland, Japan, Norway, Spain and the United States. Data from Denmark are from 2013 rather than 2014. Data from Korea are from 2015 rather than 2014. Data represents public employment by sectors and sub-sectors of national accounts. National authorities provided data for Korea and Portugal.

Source: International Labour Organization (ILO), ILOSTAT (database). Data as reported in (OECD, 2017[2]), Government at a Glance 2017, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/gov_glance-2017-en.

There is no dedicated tracking of officials working in public procurement roles in Germany. However, it can be assumed that the general characteristics of the overall German civil service also hold true for the public procurement workforce. Thus, one can infer that 1) Germany’s public procurement workforce is relatively large when compared to other OECD countries; and 2) the vast majority of public procurers work in state administrations and municipalities.

Counting the number of public procurers in Germany is difficult because, in many cases, and especially in smaller entities and on the sub-national level, public procurement is not a full-time job. This means that officials conduct procurement in addition to other tasks. Rough estimates by academics and civil society organisations working on public procurement indicate that there are 30 000 contracting authorities in Germany, with several officials each working in a procurement function. Table 6.1 below provides an overview of the number of officials in the main central purchasing units at the federal level in Germany, as well as in the competence centres focusing on procurement. The largest dedicated procurement team is located in the Federal Armed Forces. (The Federal Armed Forces has 670 full-time equivalents working on procurement).

Table 6.1. Overview of the size of units in charge of public procurement in the German federal administration

|

Name of the unit |

Number of officials |

|---|---|

|

General Customs Directorate (Generalzolldirektion, GZD), central procurement unit |

200 |

|

Federal Office for Equipment, Information Technology and the Use of the Federal Armed Forces (Bundesamt für Ausrüstung, Informationstechnik und Nutzung der Bundeswehr, BAAINBw), central procurement unit |

946 individuals or 670 full-time equivalents |

|

Federal Institute for Materials Research and Testing (Bundesanstalt für Materialforschung und -prüfung, BAM), central procurement unit |

14 |

|

Federal Procurement Office of the Federal Ministry of the Interior (Beschaffungsamt des Bundesministeriums des Innern, BeschA) |

268 |

|

Central Office for IT Procurement within the Federal Procurement Office of the Federal Ministry of the Interior (Zentralstelle für IT-Beschaffung, ZIB) |

78 (65 procurers, 13 administrators), 72 additional procurers to be hired in 2018 |

|

Administration Office of the central purchasing unit Kaufhaus des Bundes (KdB) within the Federal Procurement Office of the Federal Ministry of the Interior |

12 (including, among others 3 for catalogue and its users; 3 for executive management; 5 for support for platform) |

|

Competence Centre for Sustainable Procurement (Kompetenzstelle für nachhaltige Beschaffung, KNB) within the Federal Procurement Office of the Federal Ministry of the Interior |

8 |

|

E-procurement unit (Z 14) within the Federal Procurement Office of the Federal Ministry of the Interior |

15 overall, including 5 covering the help desk |

|

Central purchasing unit within the Federal Office for Agriculture and Food (Bundesanstalt für Landwirtschaft und Ernährung, BLE) |

26, with a requirement for 28 |

|

Competence Centre for Innovative Procurement (Kompetenzzentrum innovative Beschaffung, KOINNO) |

8 |

Source: Responses from German federal and state-level institutions to an OECD questionnaire and interviews. .

Given Germany’s generalist approach to filling public procurement roles, there is limited information about the procurement workforce. None of the statistics about the German civil service include a special category for procurers. Knowing the size and distribution of the public procurement workforce in different institutions and at different levels could provide insights into the effectiveness of procuring entities. It could also support decision making about human resource management. It would be possible for Germany to introduce categories to civil service positions; Germany already tracks some categories, specifically those related to broad tasks within an administration. Similarly, a sub-category for public procurers could be established. This is particularly important when considering that individual procurers have a large part to play in the overall value for money provided by the civil service. By tracking procurers, specialised education and training could be made available that could ultimately contribute to more strategic spending of public funds.

There is no dedicated human resources management for procurers working in the general administration of Germany. The same rules apply to all of the general public service. Members of the public service are hired in two different ways. Public procurers can be employed as civil servants (Beamte) or as public employees (Tarifbeschäftigte)3. Civil servants are appointed, and have specific duties and rights, according to Article 33 of the Basic Law of the Federal Republic of Germany (Grundgesetz für die Bundesrepublik Deutschland). The main difference between civil servants and public employees is that civil servants are appointed for life and cannot go on strike. Civil servants are also required to follow strict standards of legality, neutrality, service in the public interest and loyalty to their institutions. The Federal Civil Servants Law (Bundesbeamtengesetz) regulates conditions of employment.

Unlike civil servants, public employees are hired on the basis of one of many collective wage agreements for the public sector. These agreements vary in scope and are valid for specific levels of government, regions and professions. However, there is no specific salary scale for public procurers.

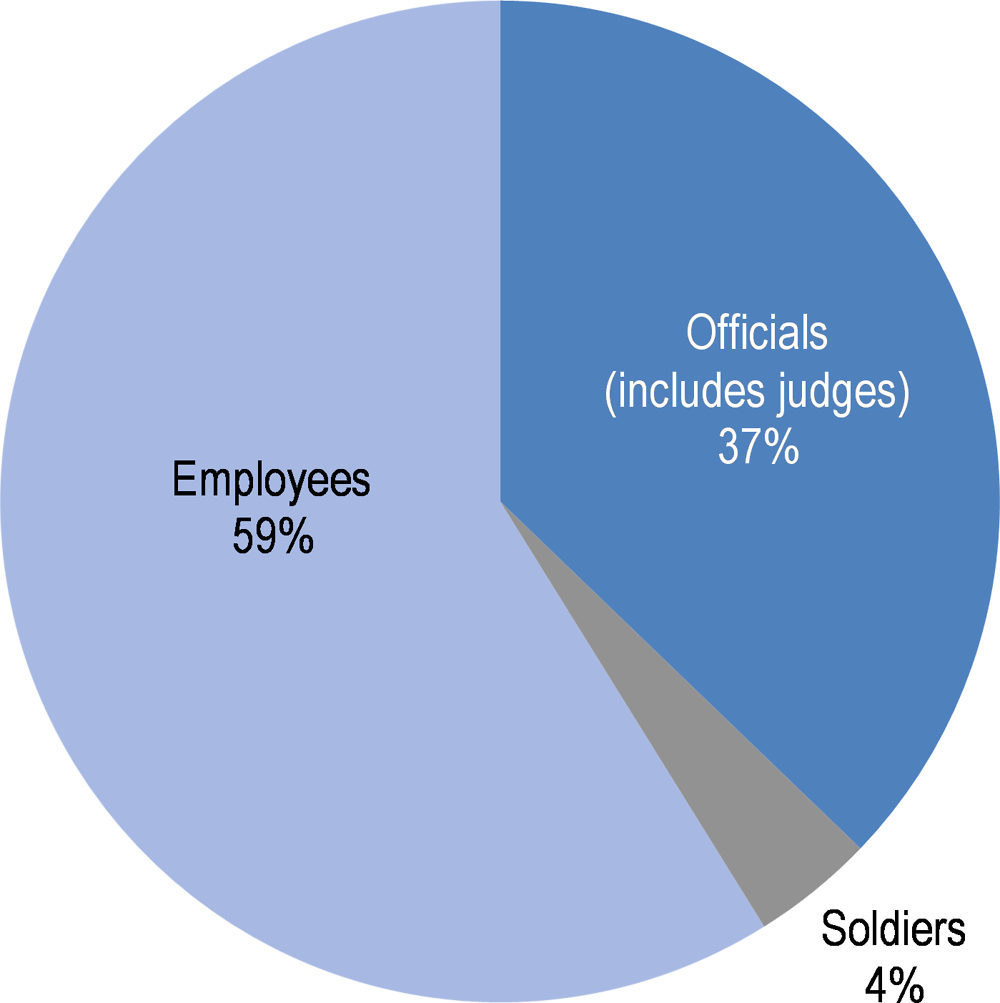

In general, civil servants conducting public procurement are not recruited for this particular role. As such, there is no dedicated role description for those conducting public procurement in Germany. In the Federal Procurement Office of the Federal Ministry of the Interior (Beschaffungsamt des Bundesministeriums des Innern, BeschA) for example, approximately 75% of staff are civil servants, while approximately 25% are hired under collective agreements. Procurers usually move to their role from the general pool of civil servants. They are also hired under collective agreements, especially when they are hired for specific tasks. A conversion to official status is possible in accordance with the general laws for civil servants and if a specific, official position exists. The overall composition of the German civil service (at all levels) is slightly different, with the majority being employed under collective agreements, as shown in Figure 6.6.

Figure 6.6. Composition of the public service in Germany, 2016

Note: The analysis is based on full-time equivalents.

Source: Statistisches Bundesamt (2017), Personal Öffentlicher Dienst, https://www.destatis.de/DE/Publikationen/Thematisch/FinanzenSteuern/OeffentlicherDienst/PersonaloeffentlicherDienst.html.

The career path of a public procurer follows their level of service, as there is no dedicated career path for authorities in the public procurement system. The German civil service distinguishes four levels of service according to the complexity of the tasks at hand. They are:

1. ordinary service (einfacher Dienst);

2. intermediate service (mittlerer Dienst);

3. higher intermediate service (gehobener Dienst);

4. higher service (höherer Dienst).

The majority of procurers in Germany are part of levels two and three, intermediate and higher intermediate service. A career path is usually specific for each level, but civil servants can also undertake additional qualifications and exams to gain promotion to a higher level. In addition, civil servants rotate between posts in the same area of the federal administration every three to five years. That means that the person who conducts public procurement today might work in a completely unrelated function tomorrow.

The rotation system has implications for the way training is structured, and disincentivises more in-depth specialisation in the area of public procurement. The system removes the need to develop specialisation in public procurers beyond the knowledge necessary to avoid basic violations. This means that the more specialised knowledge necessary for strategic procurement will likely not be acquired through training. It remains unclear to what extent procurers in Germany’s central purchasing units also rotate within their organisations to posts unrelated to procurement.

From a corruption prevention perspective, the rotation system offers advantages. Civil servants are able to gather diverse experience by rotating through diverse divisions. However, it might be beneficial to devise a system in which procurers rotate between procurement-related positions in different areas across the federal government. This would allow an increased professionalisation of public procurers while maintaining the benefits of the rotation mechanism.

6.2. Using monitoring and performance evaluation for strategic capacity building

Individual institutions are in charge of managing Germany’s public service and specifically human resources with regards to public procurers. Because of this, no overarching performance monitoring framework exists that focuses on the performance and capacity of public procurers specifically. However, the performance of the public service can be measured in several ways. This section of the chapter features several indicators that illustrate how structured monitoring and analysis can be beneficial to determining Germany’s needs with regards to public procurement capacity building. It is important to note, however, that these indicators are broad and not specifically related to public procurement.

As mentioned above, human resource management has a close connection with an organisation’s function for monitoring performance. This is because human resource management is informed by facts (i.e. an analysis of the state of an organisation’s workforce, and the workforce’s level of performance against expectations). The OECD Recommendation of the Council on Public Procurement calls for countries to have in place a “unit or team analysing public procurement information and monitoring the performance of the public procurement system” (OECD, 2016[6]). The revised Methodology for Assessing Procurement Systems (MAPS) takes this recommendation as the starting point for analysing a country’s public procurement workforce (MAPS, 2018[8]).

Generally, experts suggest basing capacity-building measures on an analysis of gaps in capacity or of procurement performance. Experts recommend this course of action because it helps authorities to target capacity-building measures most effectively and efficiently (OECD, 2017[3]; OECD, 2016[15]). Indicators can help countries to conduct a structured analysis of where they stand, rendering the analysis comparable across years and different reviewers.

6.2.1. The measurement of staff engagement through surveys can be used as a proxy to gauge institutional performance quantitatively

OECD countries increasingly track the performance of their public institutions by measuring staff engagement as a proxy for organisational performance. This technique offers a data-driven approach to human resource management. Employee engagement is about the links between employees and their institutions. Engaged employees show commitment and motivation to contribute to the achievement of an institution’s goals, while also being able to balance workload and personal well-being. Evidence links high employee engagement to high organisational performance. As such, motivated and committed public service employees are more productive, innovative and more highly trusted by citizens (OECD, 2016[1]).

Measuring staff engagement as a proxy for organisational performance offers advantages over other proxies that aggregate different aspects and aim mostly at providing international comparisons. One example of a comparison of civil service performance is the International Civil Service Effectiveness Index (InCiSE)4, developed by the University of Oxford’s Blavatnik School of Government and the think tank Institute for Government. Ultimately, the InCiSE builds a composite indicator from several dimensions that describe the performance of the public service in a broad sense, based on the functions usually delivered by a country’s administration.

Composite indicators always have to be considered with caution since they simplify complex analysis into a limited set of overarching results that may not communicate the entire depth and complexity of the findings at hand. However, the expert interviews at the base of some dimensions of the index can provide a first sense of how to develop a more quantitative survey. Germany has been assessed using InCiSE most recently in 2017, including with regards to the human resource dimension. This dimension is based on expert assessments gathered by the University of Gothenburg for their Quality of Government (QoG) project. For Germany, 35 experts were interviewed. This approach is relevant to mention in this context because it can provide insights that could contribute to defining Germany’s capacity building efforts with regards to public procurement.

Germany’s scores with regard to the average performance of civil services in more than 30 countries are depicted in Figure 6.7.

Figure 6.7. Germany’s InCiSE score compared to other countries (2017)

Source: Institute for Government, Blavatnik School of Government (2017), The International Civil Service Effectiveness (InCiSE) Index 2017, https://www.bsg.ox.ac.uk/about/partnerships/international-civil-service-effectiveness-index-2017.

Germany’s InCiSE composite indicator shows that the country scores slightly above average on human resource management and capabilities. Germany’s scores reaches 0.67 on human resource management (compared with an average of 0.54) and 0.59 on capabilities (compared with an average of 0.44).

The level of staff engagement, in contrast, is usually measured via surveys with employees. According to the 2017 OECD study on staff engagement, the majority of OECD countries found value in conducting staff engagement surveys at regular intervals. The results have helped the institutions to improve collaboration, leadership culture and attractiveness as an employer in an increasingly competitive market (OECD, 2016[1]).

Germany’s Federal Employment Agency (Bundesagentur für Arbeit, BA) has used the approach of carrying out staff engagement surveys to track and increase organisational performance (see Box 6.2). This approach could also be applied in selected contracting authorities to enhance their performance.

Box 6.2. Tracking staff engagement at Germany’s Federal Employment Agency to improve organisational performance

Germany’s Federal Employment Agency (BA) developed a specific engagement index whose results feed into the institution’s human resource management and business strategy. The index is derived from a survey and focuses on teamwork, values and goal-oriented behaviour. The survey contains 19 questions in the following five dimensions (OECD, 2016, p. 72[1]):

1. willingness to strive (to what extent the employee’s day-to-day behaviour at work is geared toward individual and team goals);

2. identification (to what extent the employee’s attitude is aligned with BA’s goals);

3. psychological contract (to what extent the employee feels they can voice ideas and be perceived as people beyond their work);

4. workability (to what extent the employee is able to deliver at work while being able to balance their private lives);

5. communication (whether the employee supports the team by actively participating in meetings and the exchange of information and ideas).

To ensure that the findings of the survey are transformed into concrete improvements for the BA, the survey results are shared transparently in an IT portal. Leadership workshops support the analysis of results. Top executives receive performance-related pay that is linked to the goals that are informed by the engagement index. Over time, BA’s surveys have resulted in increased customer satisfaction, and are expected to have an impact on overall outcomes.

Source: (OECD, 2016[1]), Engaging Public Employees for a High-Performing Civil Service, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264267190-en.

6.2.2. Existing monitoring efforts in Germany could provide a basis for an evidence-based human resource management strategy

There are several examples in the German federal administration of how evidence-based monitoring and evaluation supports decision making and policy reform. Aside from the example by BA mentioned above, several other initiatives provide a good basis for building procurement-related monitoring to increase staff performance.

For example, in 2010, Germany’s General Custom’s Directorate (Generalzolldirektion, GZD) conducted a reorganisation of its procurement function with the aim of centralising it. Prior to launching the restructuring, GZD conducted a profitability analysis. As a part of this analysis, employees were asked to track how they used their time before and after the restructuring. Following the restructuring, GZD could compare how long employees spent on specific tasks (both before and after the restructuring). This comparison proved helpful in demonstrating the purpose of the centralisation efforts by highlighting the concrete savings that were achieved.

Beyond public procurement, two examples of policy monitoring may be relevant to Germany’s evidence-based monitoring and evaluation plans. Germany undertakes structured monitoring endeavours as a part of efforts to contain its regulatory burden. In addition, the Federal Statistical Office surveys citizens about their experiences with public services (OECD, 2015[16]).

Expertise in policy monitoring could be useful to Germany in devising a more structured approach to monitoring performance in the area of public procurement and informing future capacity-building efforts. Responsibility for human resource management in Germany’s public procurement system lies with individual institutions, and their organisation of the public procurement function is diverse. Therefore, any efforts to support decision making around human resource management with an increased evidence base have to be flexible. One example of how to balance the need for flexibility with efforts to compare performance has been developed in New Zealand, where contracting authorities can conduct self-assessments with the aim of professionalising the different procurement units according to their needs (see Box 6.3).

Box 6.3. New Zealand’s Procurement Capability Index

New Zealand’s Procurement Capability Index (PCI) is a self-assessment tool that enables contracting authorities to find out how well they are performing against “best in class” expectations, as well as other contracting authorities. The PCI also allows authorities to identify areas where additional focus may be required to either reach an acceptable level of performance, or to take a high-performing agency to the next level. By using the PCI tool to identify strengths and weaknesses, an agency can develop and implement strategies that result in actual measurable and worthwhile improvements.

At the central level, New Zealand’s central procurement body New Zealand Government Procurement (NZGP) has further use for the PCI results. By reviewing the results from different agencies, NZGP can offer tailored support programmes to certain agencies. NZGP also offers to partner agencies that are particularly strong in certain areas with weaker agencies.

The analysis using the PCI tool is based on the contracting authority’s own view of its procurement capability, and has to be representative of the entire contracting authority beyond the procurement function. For the self-assessment to be relevant and accurate, it requires a range of people in the agency to be involved (e.g. the procurement team, senior managers, agency buyers and other stakeholders with a view of procurement activity within the agency). The PCI process, while self-assessed, includes evidenced-based external moderation and review.

The PCI tool covers the complete cycle of good procurement practice from strategic planning practice to leadership, policy, supplier and people management. It ultimately concludes with technology and systems.

Once results from the Procurement Capability Index have been developed following the year’s results, NZGP will be able to measure the impact of capability-building work by measuring changes in agency capability scores over time.

Source: New Zealand Government Procurement and Property (n.d.), Procurement Capability Index, https://www.procurement.govt.nz/procurement/improving-your-procurement/frameworks-reporting-and-advice/procurement-capability-index/.

6.3. Raising the capacity of the human capital involved in public procurement

The following sections provide an overview of the most important training opportunities for public procurers, and how these could be better used to raise the capacity of the public procurement workforce. A more structured, strategic and specialised approach to training could increase the performance of Germany’s public procurement system overall.

Procurers’ capacities – not only in terms of numbers, but particularly in terms of skills – has to grow to keep up with increasing challenges. Capacity building is increasingly seen as an investment, particularly for procurers who have a large influence on the efficiency and effectiveness of public procurement with regard to policy goals and value for money (OECD, 2017[3]). In fact, studies have shown a direct link between procurers’ knowledge and their compliance with regulations, laws, policies and strategies. Experience is also one of the most important factors to ensure compliance (Hawkins and Muir, n.d.[17]).

Germany offers a range of capacity-building opportunities for public procurers. The measures aim first to increase the capacity of individual procurers by increasing their knowledge (through training, help desks, guidance documents and tools). Second, Germany aims to increase the performance of contracting authorities overall (by reorganising workflows, for example). Germany’s structured capacity building efforts fit broadly into three categories: 1) general training offered by public institutions in the country’s administrative academies; 2) general training offered by third parties, such as for-profit, private providers or non-profit organisations; and 3) specialised capacity-building efforts – for example on innovation procurement or sustainable procurement – by Germany’s competence centres.

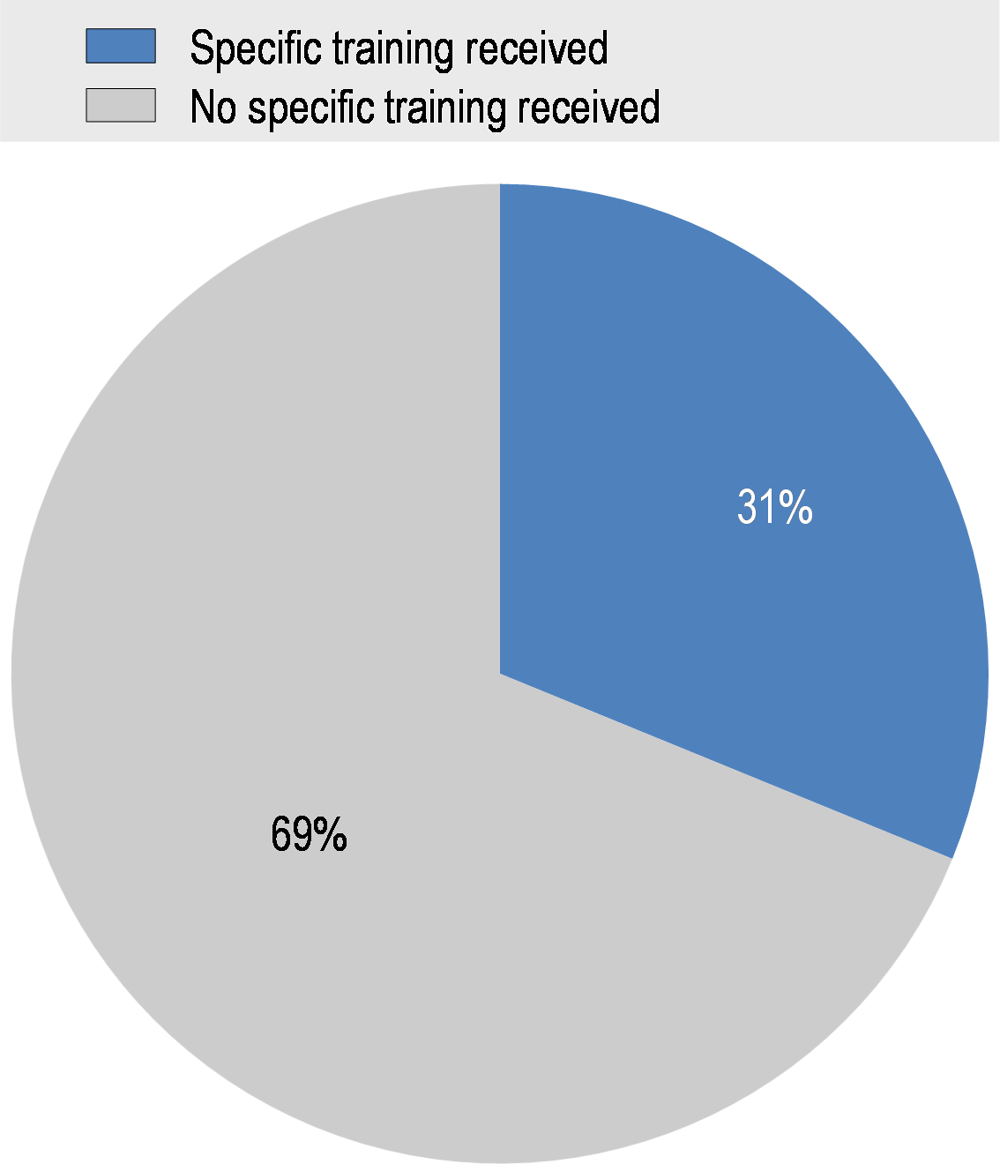

While this is a broad training offering, the average public procurer in Germany does not take as much advantage of the training as they could. According to a 2015 survey conducted by researchers Eßig and Schaupp (Eßig and Schaupp, 2016[11]), more than two-thirds of public procurers in Germany do not seem to have been trained to conduct public procurement, as highlighted in Figure 6.8.

Figure 6.8. The majority of public procurers in Germany have not received specific training

Note: This figure is based on the survey question, “are the employees working in the procurement department of your institution explicitly trained to cover this function?”.

Source: Unpublished survey data from (Eßig and Schaupp, 2016[11]), Erfassung des aktuellen Standes der innovativen öffentlichen Beschaffung in Deutschland – Darstellung der wichtigsten Ergebnisse, https://www.koinno-bmwi.de/fileadmin/user_upload/publikationen/ Erfassung_des_aktuellen_Standes_der_innovativen_oeffentlichen_Beschaffung....pdf.

Efforts to increase the capacity of public procurers in Germany are diverse, similar to the efforts to regulate employment. No central, structured approach or guidelines to increasing procurer capacity exists. However, most institutions in charge of public procurement generally offer guidance and support on the implementation of laws. Often, the institutions tasked with public procurement also provide a help-desk service that is available to answer questions from other institutions. Different ministries on different levels of government have developed and distributed circulars, guidance materials and handbooks on an ad hoc basis as well. All of these types of trainings, however, have to be sought out by individual procurers with the consent of their managers. While there are no direct barriers to training in Germany, there is also no structured, general guidance on how and when training should be conducted. Because these decisions are made on an ad hoc basis, results are uneven. There is no general legal obligation for permanent training either. Finally the education of lower level administrative staff in Germany covers procurement for less than 10% of total class hours.

6.3.1. Administrative academies in Germany could increase awareness about the importance of procurement professionalisation and procurement training

Once on the job, civil servants receive additional training to a large extent at administrative academies. These academies exist at the federal level in the form of the Federal Academy for Public Administration (Bundesakademie für Öffentliche Verwaltung, BAköV), and on the state level. The BAköV features public procurement in its training catalogue. Germany could build on and increase existing training options, adapting them to the current and future challenges of public procurers. If Germany chooses to undertake this work, it will be important to increase awareness that high performance in public procurement largely depends on the individual capabilities of public procurers. Political leadership is necessary to change how authorities view training. Training should be seen as an investment into the impact of public procurement.

The BAköV provides training on all aspects of the administration for officials in the federal administration. Some states have similar institutions that provide training for officials in state administrations.

The BAköV is one training institution that provides training on public procurement. This chapter takes a closer look at this institution because a quantitative analysis of ten years of the BAköV’s training courses was possible based on the institution’s online training catalogue. While a comprehensive analysis of all procurement training in Germany is not possible, the BAköV’s training programme can provide an illustration of the current situation. The BAköV is also the dedicated institution in charge of training for the federal administration, and therefore has an important role to play when it comes to professionalising procurers in the federal administration.

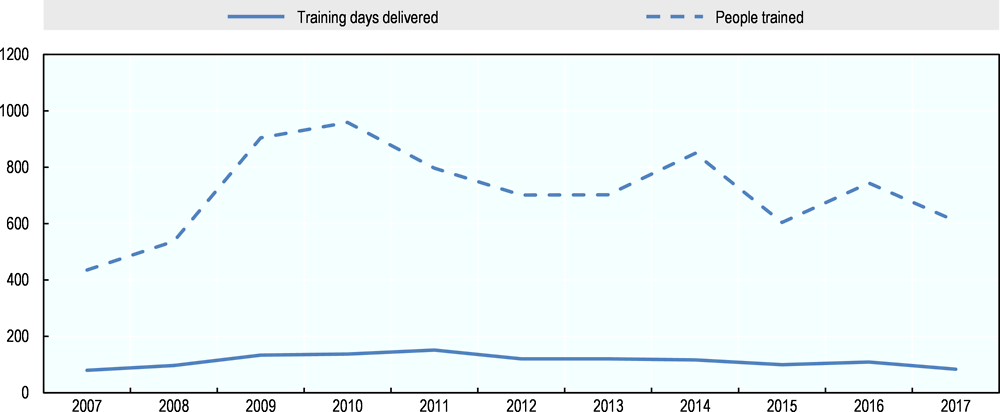

Several of the BAköV’s programmes are related to public procurement – some directly, some indirectly. According to the BAköV’s online catalogue5, courses that have been offered over the past ten years convey themes such as the basics of how to conduct procurement processes, how to conduct procurement processes for the needs of different institutions and how to conduct a value for money analysis. Other courses touch upon public procurement as a side note to the main topic, like courses on budget law or competition rules. In 2017, the BAköV trained 609 people in public procurement-related courses, delivering 84 days of training. The BAköV trained its highest number of people on procurement in 2010 (959 people). Finally, the BAköV delivered its highest number of training days with a direct procurement focus in 2011 (152 training days.) That being said, trainings on offer by the BAköV with regard to procurement have been declining in recent years. This is surprising, because the need for training in Germany is higher than ever, as there is an increasing need for procurers who can implement strategic procurement processes. Figure 6.9 illustrates the development of training related to public procurement at the BAköV in the last ten years.

Figure 6.9. Procurement-related training provided by Germany’s Federal Academy for the Public Administration (Bundesakademie für öffentliche Verwaltung, BAköV), 2007-2017

Note: The number of people trained is based on the maximum number of participants noted in the online catalogue.

Source: Authors’ analysis based on data in the training catalogue for BAköV at https://www.ifos-bund.de/.

Although the BAköV is not the only source of training for procurers, its training programme has to be considered in comparison with the number of contracting authorities in the federal administration. There are close to 700 institutions with a procurement function in the direct and indirect federal administration in Germany. Often, these institutions have several procurers each. Procurers in central procurement units are usually trained in-house by more experienced procurers. Still, with 600 spaces available for trainings every year, there is sufficient capacity for every procurer to participate in a BAköV training once every few years. In fact, as highlighted in stakeholder interviews, demand for public procurement training is high, and not all demand can be met due to shortages of suitable trainers. Usually, procurement practitioners in the public administration run these trainings. However, trainers have to take annual leave to be able to conduct the trainings. These trainers also need to receive a formal approval from their supervisors. In several cases, stakeholders reported to the OECD that the supervisors have not always met BAköV’s requests for trainers with enthusiasm. External trainers, however, often did not deliver the type of training that public procurers required. In addition, external trainers were usually prohibitively expensive.

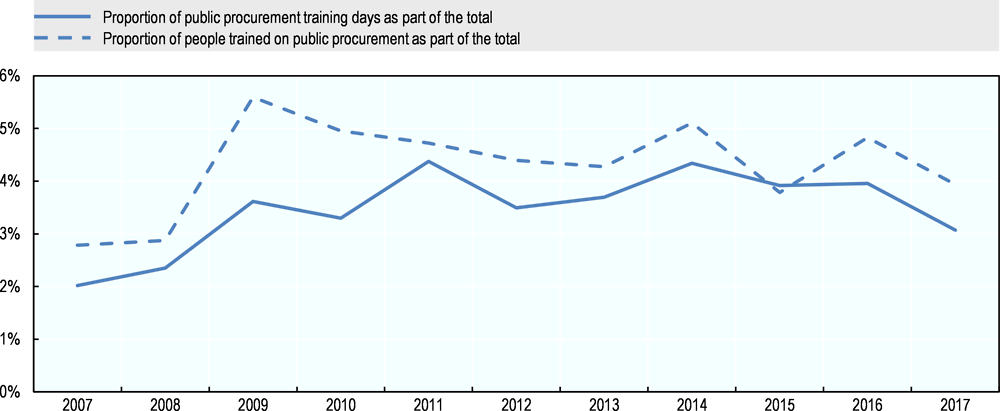

Considered as a proportion of all trainings offered by the BAköV in 2017, procurement was the primary topic of only 3% of total training days and 4% of total people trained. This share has decreased in recent years (see Figure 6.10). Given that there is no information about how many people work in a procurement function in Germany, it is difficult to judge whether this level of training is sufficient.

Figure 6.10. Proportion of procurement training offered by Germany’s Federal Academy for the Public Administration (Bundesakademie für öffentliche Verwaltung, BAköV), 2007-17

Source: Authors’ analysis based on data in the training catalogue for BAKOEV at https://www.ifos-bund.de/.

The audience for training programmes warrants discussion. As mentioned above, the German civil service distinguishes between several levels of service. Public procurers are predominantly part of the two mid-level categories, the intermediate and higher intermediate service. The BAköV’s procurement training courses seem to be less geared to these two levels. Only seven out of 447 trainings delivered since 2007 were geared toward these two levels alone. The majority of trainings did not seem to be geared toward a specific service level. The BAköV designated 387 trainings as pertaining to the upper three levels of civil service. On average, authorities from each of the four levels can choose from more than 400 trainings. However, given the different tasks demanded by different levels of the civil service, most of these trainings target officials with very different tasks. It remains unclear to what extent the trainings can really bridge the differences in the training needs of these different levels of government.

The human resources strategy of Germany’s Central Office for IT Procurement (ZIB) within the Federal Procurement Office of the Federal Ministry of the Interior (BeschA) consists of hiring IT experts and training them in procurement issues. This approach is easier than trying to convey IT knowledge to legal or administration experts. The BAköV then trains new hires using an influencers or multipliers approach with the intention that these newly trained procurers pass on knowledge if necessary.

In almost all central purchasing bodies in Germany, managers acknowledge the benefits of hiring increasingly specialised officials. For example, the Federal Institute for Materials Research and Testing (Bundesanstalt für Materialforschung und -prüfung, BAM) mostly purchases items that are needed for scientific application in a research setting. That means that BAM officials in charge of purchasing need 1) knowledge in relation to procurement, including laws and procedures; and 2) knowledge in relation to the technical aspects of the purchased goods.

OECD interviews with German stakeholders revealed that a major obstacle to effective training of procurers was the limited number of trainers available. This limited supply of trainers was partly due to a culture in which training activity outside of the day-to-day tasks of procurement was considered something negative, rather than a distinction for experts in the field. High performers within the public procurement system are essential to disseminating good practices throughout the system. Therefore, they should receive more support.

German policy makers should be aware of the benefits of a professional public procurement workforce, and should work to establish public procurement as a recognised profession. Germany could try to accomplish this by 1) establishing public procurement as a profession; and 2) raising the visibility of professional public procurers and how they contribute to the economic impact of procurement for Germany’s citizens. Raising the professionalism of public procurement and public procurement’s visibility can be accomplished in different ways. However, this action will likely require more committed and profound leadership at the federal level. Committed action at the federal level will also be vital to achieving a public procurement career path – even if informally.

Germany could begin by working toward a system where a specific person or persons that have successfully worked through a set of courses with BAköV champions procurement in every institution. This procurement champion could then serve as a contact point and source of support to others within the contracting authority. A more advanced step for the long term could be to think about a certification that interested officials (such as the institutional procurement champions) could voluntarily work toward to further specialise in public procurement. The procurer would have to conduct a set of training courses, starting with more basic content and building toward more specialised and advanced content. Following a successful completion of the course, procurers would receive a certificate. Certification would have the advantage of increasing the standing of procurers within the organisation and beyond. A certificate could lend more visibility to those officials that have already gathered immense experience throughout their careers and operate as procurement champions in their organisations. Following the EU recommendation on professionalization of public procurement, some European countries have taken steps to develop such a certification framework.

6.3.2. General training offered by third parties is available to patch training needs on a case-by-case basis

There are a plethora of private providers of public procurement-related training in Germany. Firms offer courses on a for-profit basis (e.g. law firms). In addition, non-profit organisations (e.g. Forum Vergabe, Deutsches Vergabe Netzwerk, regional chambers of industry and commerce, and others) offer classes. Interested procurers can research courses on offer through a variety of online search engines offered by private portals or local chambers of industry and commerce. There is one university-level programme that allows a specialisation in public procurement, offered by the University of the Federal Armed Forces, Munich. This programme was recently launched as a Master of Business Administration in Public Management.

As with other types of training, the individual procurer must take the initiative to choose training. German authorities have not issued any structured guidance as to how public procurers can use training courses to further their professionalisation. The prices for the private courses vary immensely. In addition, it remains unclear who covers the costs of training courses. The majority of courses seem to convey legal knowledge. Courses with more practically oriented content are rare. The market seems to regulate the quality and content of these programmes, as well as access. There is no independent or structured assurance of the quality of these courses, and there is also no independent or structured assurance of their availability. An example of one well-known organisation providing training, Forum Vergabe, is provided in Box 6.4.

Box 6.4. Providing an exchange on public procurement in Germany: Forum Vergabe

Forum Vergabe is a non-profit organisation supporting procurement practitioners with a platform for the exchange of information, experiences and opinions about public procurement in Germany and globally.

Forum Vergabe was founded in 1993. It has around 500 institutional and personal members, stemming from the private and public sector, including interest groups, companies and procurers, among others. The organisation finances its activities solely through member fees, which are EUR 130 for personal members and EUR 1 000 for institutional members per year. Forum Vergabe is organised into eight regional groups.

A strong focus of Forum Vergabe’s work is on procurement law. Forum Vergabe’s services include provision of information on public procurement law in different countries. As such, Forum Vergabe provides:

a monthly newsletter on relevant developments, such as new laws, court decisions, and more

a series of practice-related, scholarly articles

all decisions of challenges and appeals of procurement cases at the federal, Länder and EU level, as well as a database of procurement laws and regulations

advisory services on national, EU and World Trade Organisation (WTO) procurement rules for members.

Forum Vergabe also facilitates dialogue on public procurement law and its application through:

a seminar series called Forum Vergabe Talks and other seminars and panels

exchanges with partner organisations in Europe

awards for academic research in the area of public procurement.

Finally, Forum Vergabe provides training courses on procurement law. Forum Vergabe has offered structured trainings on the general basics of public procurement since 2015. In 2016, 930 people participated in training. On average, Forum Vergabe trains 500 to 600 people per year. A two-day training costs approximately EUR 450.

Source: Forum Vergabe (2013), Das Forum Vergabe: gemeinnützig - interessenübergreifend - neutral, http://www.forum-vergabe.de/das-forum-vergabe/.

Given the market-regulated landscape in Germany and the lack of central oversight in the country, there is limited information on how many public procurers take advantage of external training institutions. For the same reasons, it is also hard to determine what profile procurers who attend trainings have, and how they use the acquired knowledge. This lack of information makes it difficult to track the impact that training has for the professionalisation of public procurement and human resource capital in Germany. Some measurements exist, however. According to Forum Vergabe, procurement advisory centres run by regional chambers of commerce conducted trainings for 8 135 participants in 2016.

To maximise the potential impact of training courses on the public procurement workforce, it could be beneficial to establish an outline of the minimum that a course should offer with regard to legal and practical knowledge. Such an outline could be known as a guidance framework. Courses that meet the minimum requirements delineated in the guidance framework could be highlighted and recommended. This would provide guidance for individual procurers and ensure that they do not have to rely on hearsay about the quality of courses or professors, or that they are dependent on a knowledgeable leadership that could advise them on how to choose training content. Providers of these trainings would have an incentive to have their courses aligned with the guidance framework if it generates higher demand.

6.3.3. Germany’s competence centres are a strong model and can increase capacity in public procurement

Germany’s competence centres have contributed substantially to the increased capacity of the public procurement workforce in the country. In fact, the competence centre model could have benefits for Germany’s procurement system in additional ways as well.

Germany has two competence centres on public procurement at the federal level. These two centres have been successful in recent years in increasing the capacity of procurers in their respective areas (see Chapter 5). The centres are called the Competence Centre for Sustainable Procurement (Kompetenzstelle für nachhaltige Beschaffung, KNB) and the Competence Centre for Innovative Procurement (Kompetenzzentrum innovative Beschaffung, KOINNO). Both centres offer a mixture of support through on-demand services, an information portal and structured capacity building.

The KNB aims to provide targeted information and training on sustainable procurement to all contracting authorities at all administrative levels. There are different channels through which the KNB disseminates this knowledge, including an online platform, contact points for support, guidance materials and training (Kompetenzstelle für nachhaltige Beschaffung, n.d.[18]).

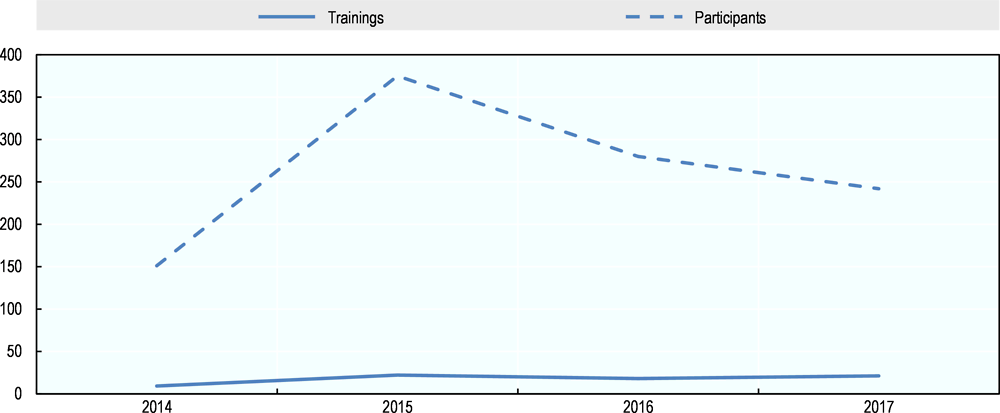

Sustainable public procurement training by the KNB follows a modular approach to allow coverage of specific interests and products. Modules cover topics like climate-friendly procurement, certificates and the Programme of Measures for the Federal Administration (Chapter 5.) Since 2014, the KNB has trained a little over 1 000 people in 65 trainings. The majority of these trainings (36 out of 65) were conducted with institutions at the municipal level. In addition, 20 out of 65 trainings were conducted with institutions at the federal level (Kompetenzstelle für nachhaltige Beschaffung, n.d.[19]). Since the majority of procurement occurs at the sub-national level, more training is needed at this level. Furthermore, Germany could benefit from raising awareness further at the federal level about the need for support in capacity building on sustainable public procurement at the state and municipal levels. Figure 6.11. illustrates the development of training courses by KNB.

Figure 6.11. Trainings offered and participants trained by the KNB, 2014-2017

Source: Authors’ analysis based on information provided on KNB’s website at. Kompetenzstelle für nachhaltige Beschaffung (n.d.), Schulungen zur nachhaltigen Beschaffung, http://www.nachhaltige-beschaffung.info/DE/Schulungen/schulungen_node.html#doc5160128bodyText1.

The KOINNO is another competence centre that supports the professionalisation of public procurers in Germany. The KOINNO has operated since 2014 and has been tasked with supporting contracting authorities in implementing procurement to support innovation. The KOINNO is a joint project of the Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Energy (Bundesministerium für Wirtschaft und Energie, BMWi) and the Federal Association for Supply Chain Management, Procurement and Logistics (Bundesverband Materialwirtschaft, Einkauf und Logistik e.V., BME). The BME also has a section for public procurers (aside from private sector purchasers.)

The KOINNO follows a different approach from the KNB as it emphasises concrete, case-related advice for individual contracting authorities. As such, the KOINNO works similarly to a consulting firm in practice. The KOINNO also offers an online platform with guidance, as well as events to complement these services.6 Training provided by the KOINNO is always specifically geared toward the needs of individual contracting authorities (KOINNO, n.d.[20]).

The KOINNO’s success is most visible in its direct advisory role for contracting authorities (Berger et al., 2016[21]). The KOINNO has also been involved in several technically complex projects. For example, the KOINNO provided support to Saxony’s state police when it introduced an e-mobility concept for its fleet. In addition, the KOINNO has co-operated with the German Aerospace Centre (Deutsches Zentrum für Luft- und Raumfahrt, DLR) most recently to procure a water-cooled computer centre. Often, however, the guidance provided by the KOINNO relates to general aspects of management and good institutional practices, like change management. For example, the KOINNO advised Saxony’s Development Bank (Sächsische Aufbaubank) when it centralised its procurement function. The main goals of this project were to standardise and bundle purchasing in an effective and efficient way, while at the same time avoiding maverick buying. Similarly, the KOINNO has supported Germany’s Federal Labour Office in developing a procurement strategy as a part of a new overall institutional strategy. Finally, OECD interviews with authorities at the KOINNO showed that considerable demand by German contracting authorities for support is often linked to fairly general management questions.

Overall, competence centres like the KNB or KOINNO offer a valuable model when it comes to raising the capacity of public procurers and increasing the professionalism with which procurement is conducted. The KOINNO and KNB have championed their respective areas of public procurement (innovation and sustainability), and are known as sources of advice and structured capacity building (see Chapter 5). Similar to these competence centres, some of Germany’s central purchasing units take on an advisory role, like the central purchasing unit within the Federal Office for Agriculture and Food (Bundesanstalt für Landwirtschaft und Ernährung, BLE). The most value added by these central purchasing units taking on an advisory role is related to the exchange of practical, case-related knowledge. These knowledge exchanges can occur through a knowledge depository or through the direct, case-related advisory function these central purchasing units have to solve specific questions. The latter, direct exchange, is more frequent.

Germany could choose to use central purchasing units to increase the capacities of public procurers with regard to general, day-to-day procurement (i.e. the areas in which the KOINNO and KNB would not be adequate support institutions). Given the support that is needed, a network for public procurers co-ordinated by one contact point at the federal level might be most useful to achieving the following:

1. connecting procurers in different institutions and providing a safe space for the exchange of experiences among procurers;

2. serving as a help desk for procurers at all administrative levels;

3. assisting in the exchange of knowledge between procurers and organisations working on the procurement topic, including professional bodies (such as the Forum Vergabe, German Network for Public Procurement and BME) and academic institutions;

4. recommending trainings and guidance on how to find the right information (e.g. from the KOINNO or KNB);

5. serving as a repository of experience, information and consistency regarding implementation in a system where procurers rotate;

6. offering a certification mechanism for those procurers that conduct a certain portfolio of training.