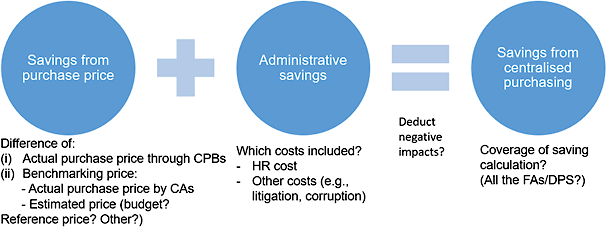

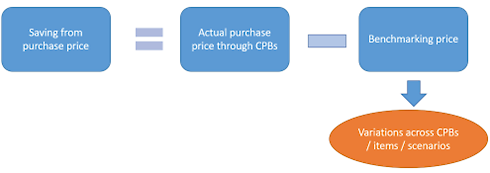

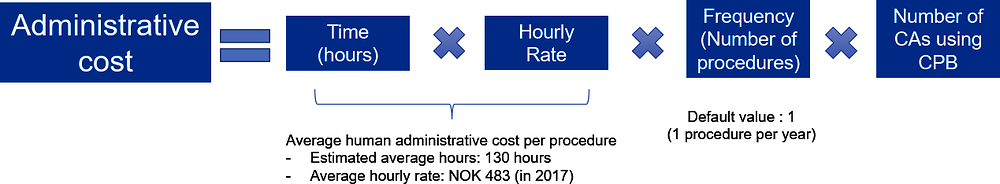

This chapter describes the current state of play of the ongoing centralisation reforms of the public procurement function in Lithuania. The chapter starts by recalling the theory related to centralisation of public procurement and the role of a central purchasing body (CPB). Then, it overviews its evolution in Lithuania until 2020 and the ongoing centralisation reform implemented since 2021. Then, the chapter examines how CPO LT, the largest CPB in Lithuania, can maximise the benefits and impacts of the ongoing reform to contribute further to improving the overall performance of the public procurement system in Lithuania through their centralised purchasing services. The chapter also shows key results and takeaways from the ProcurCompEU survey which was carried out to six CPBs to identify competences that require more capability-building initiatives. Lastly, the chapter proposes a performance measurement framework tailored to CPBs in Lithuania and benchmarks methodologies of calculating savings from centralised purchasing.

Public Procurement in Lithuania

1. Centralisation

Abstract

1.1. Centralisation of procurement and the role of a central purchasing body

Centralised public procurement and a central purchasing body (CPB) are usually key components of public procurement reforms. Recently, during the COVID-19 crisis, centralised public procurement played an important role in procuring medical products such as vaccine, medical equipment, and masks. (OECD, 2020[1]) In Europe, central purchasing bodies are referred to since the EU Directive 2004/18/EC. However, this does not mean that CPBs did not exist in the EU Member States before 2004. In fact, they had already existed even before 2004 in many Member States such as Finland, Spain, Sweden, France and Denmark, and the European Commission has also recognised the existence of CPBs. (Hamer and Comba, 2021[2])

Under the latest EU Directive on public procurement (2014/24/EU, hereinafter referred to as the Directive), already transposed to all EU member states, including Lithuania, a central purchasing body (CPB) is defined as a contracting authority providing centralised purchasing activities and, possibly, ancillary purchasing activities under the Article 2(16). Article 2(14) of the Directive defines centralised purchasing activities as activities conducted on a permanent basis, in one of the following forms: (i) the acquisition of supplies and/or services intended for contracting authorities; and (ii) the award of public contracts or the conclusion of framework agreements for works, supplies or services intended for contracting authorities. Article 2(15) defines ancillary purchasing activities as activities consisting in the provision of support to purchasing activities, in particular in the following forms: (a) technical infrastructure enabling contracting authorities to award public contracts or to conclude framework agreements for works, supplies or services; (b) advice on the conduct or design of public procurement procedures; (c) preparation and management of procurement procedures on behalf and for the account of the contracting authority concerned. Procurement techniques and electronic instruments used by CPBs include framework agreements (Article 33), dynamic purchasing systems (Article 34), electronic catalogues (Article 36) and electronic auctions (Article 35). Both procurement techniques and electronic instruments can increase competition, aggregation and digitalisation of procurement processes, and streamline public purchasing (European Commission, 2014[3])

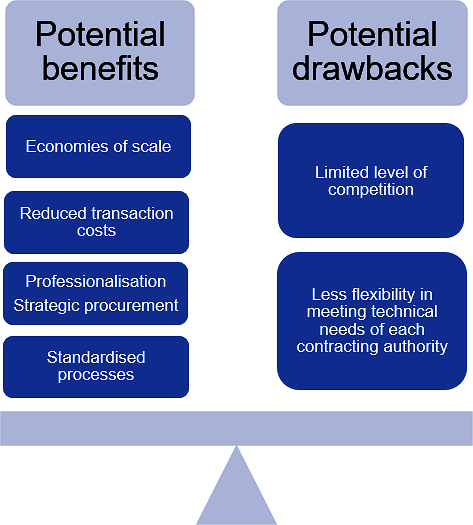

As some OECD studies and the Recital 59 of the EU Directive 2014/24/EU on public procurement point out, there are arguments in favour of and against centralised purchasing. Centralised public procurement brings economies of scale including lower prices and transaction costs, the higher level of professionalisation of the public procurement workforce, and increased administrative efficiency from standardisation through the aggregation of demand by public entities. On the other hand, the same Recital also recognises potential pitfalls which might arise from the aggregation of demand, such as excessive concentration of purchasing power which might affect the level of competition in the public procurement market such as market access opportunities for SMEs (European Commission, 2014[3]).

Figure 1.1. Potential benefits and drawbacks of centralised public procurement

It should be mentioned, however, that there is evidence that the aggregated demand through centralised purchasing did not necessarily harm SMEs’ opportunities to win public contracts. For example, an OECD SIGMA paper found out that SMEs were generally well represented in the contracts awarded through the framework agreements of almost all CPBs analysed. (OECD, 2011[4]) In Chile, small enterprises (except medium enterprises) accounted for 37% of the total contract amounts awarded through in 2022. In addition, the Directive foresees the measures to facilitate the SMEs participation in public procurement such as the division of contracts into lots (Article 46) and the limit (two times the estimated contract value) on the minimum yearly turnover that economic operators are required to have (Article 58). (European Commission, 2014[3])

Regardless of some arguments raised against centralised public procurement, the fact that many countries established CPBs at different government level and/or different sectors affirms that centralised public procurement can be a key instrument for the budgetary-constrained public sector to seek efficiency through both economic and non-economic benefits.

Box 1.1. Arguments in favour of and against centralised public procurement

There are various arguments in favour of centralised public procurement:

Economies of scale

Centralised public procurement that aggregates the demands of multiple contracting authorities leads to the larger procurement volume that brings the better price through economies of scale.

Reduction of transaction costs

Under centralised public procurement, both contracting authorities and economic operators can benefit from a significant reduction of transaction costs (time and expenditures) spent on public procurement procedures. Contracting authorities do not need to spend substantial time and resources to organise public procurement procedures. Economies of scale and the reduction of transaction costs are attractive to economic operators, because they can deliver larger volume with less numbers of contracts and customers rather than they have a large number of contracts and customers with small contract volume.

Other benefits

Centralised public procurement may also bring the following benefits that cannot be directly expressed in economic terms:

Increased level of professionalisation: centralised public procurement fills in the gaps of the capacity and capability of the contracting authorities that do not have enough capacity and/or capability of carrying out public procurement procedures by themselves. Capable officials at central purchasing bodies can implement the procurement procedures on behalf of contacting authorities, and thus can reduce the risks that otherwise would have been borne by contracting authorities (e.g., risk of complaints, poor or insufficient quality of products, and inadequate tender conditions / contract terms)

Standardised processes or increased administrative efficiency

CPBs as instruments to drive the strategic use of public procurement such as promoting green procurement, innovation and SME participation.

There are, however, also arguments against centralised public procurement:

Market concentration

One of the potential arguments has to do with the potential risk of market concentration arising from excessive centration of purchasing power.

Less flexibility in meeting the technical needs of each contracting authority

Another main argument raised against centralised public procurement is the difficulty in meeting the technical requirements of each contracting authority due to standardisation, because each contracting authority has specific preferences on the technical specifications and requirements of the goods/services/works to be procured. Therefore, sometime contracting authorities have to compromise and give up procuring the goods that meet their needs. This is particularly the case where products are not homogenous and where various substitutes exist in the market.

Source: (OECD, 2011[4])

The next section describes the current state of play and reforms of centralised public procurement in Lithuania.

1.2. Evolution of centralisation in Lithuania

1.2.1. Centralised purchasing in Lithuania and its evolution until 2020 before the start of the ongoing centralisation reform (2021)

Lithuania has been implementing reforms to increase the centralisation of public procurement since the establishment of CPO LT in 2012 to provide centralised purchasing services such as framework agreements (FAs) and dynamic purchasing systems (DPS). Value of the centralised procurement increased from 4.1% in 2013 to 10.0% in 2020 as a share of the total procurement volume in the country.

CPO LT is the largest central purchasing body (CPB) in Lithuania. In 2020, CPO LT represented the majority of centralised procurement carried out in Lithuania: 91% in terms of the number of awarded contracts and 87% in terms of the value of awarded contracts. The rest of 10% was shared by other CPBs. (See Table 1.1)

Table 1.1. CPBs in Lithuania and its share in centralised purchasing (2020)

|

CPBs |

Scope |

Number of awarded contracts |

Value of awarded contracts (EUR) |

Average value of awarded contracts (EUR) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Number |

Share (%) |

Number |

Share (%) |

|||

|

CPO LT |

Largest CPBs in Lithuania, arranging FA and DPS for a wide range of services, goods, and works |

18 158 |

90.8% |

397 253 493.65 |

87.5% |

21 877.60 |

|

Kaunas city municipality administration |

Food, agricultural, oil products, transportation services, construction works (regional) |

947 |

4.7% |

18 506 507.38 |

4.08% |

19 542.25 |

|

Asset Management and Economy Department under the Ministry of Interior |

Various services, goods and works |

617 |

3.1% |

21 507 354.92 |

4.74% |

34 857.95 |

|

Jonava district municipality administration |

Food and agricultural products (regional) |

27 |

0.1% |

368 987.02 |

0.08% |

13 666.19 |

|

Prison Department under the Ministry of Justice (*) |

Services, goods and works for subordinate institutions |

162 |

0.8% |

15 821 196.80 |

3.48% |

97 661.71 |

|

Police Department under the Ministry of Interior |

Services (financial, insurance, etc.), goods (food, furniture) for subordinate institutions |

34 |

0.2% |

347 074.28 |

0.08% |

10 208.07 |

|

SC "Kauno energija" (**) |

Solar photovoltaic power plant projects (executes CPBs functions since 2021) |

0% |

0% |

|||

|

Alytus city municipality administration |

Meat products for kindergartens (regional) |

45 |

0.2% |

172 527.41 |

0.04% |

3 833.94 |

|

Information Society Development Committee (***) |

IT services |

10 |

0.1% |

28 454.36 |

0.01% |

2 845.44 |

|

Subtotal of other CPBs (except CPO LT) |

1842 |

9.2% |

56 752 102.17 |

12.5% |

30 810.04 |

|

|

TOTAL |

20 000 |

100% |

45 400 5595.8 |

100% |

22 700.28 |

|

Note: The following CPBs do not operate anymore as a CPB: *Prison department was reorganised by merging all subordinated prions/organisations. As of July 2023, it is called Prisons Office but it is not a CPB anymore because it purchases only for itself after merging all subordinated prisons, ** SC "Kauno energija: This was an ad-hoc CPB for one particular procurement procedure, and does not operate anymore. *** Information Society Development Committee does not carry out procurement procedures anymore as all the procedures are transferred to CPO LT

Source: Prepared based on the information provided by the government of Lithuania

CPO LT is a public institution which was established in 2012, with the purpose of increasing efficiency of public procurement through efficiency tools such as framework agreements (FAs) and dynamic purchasing systems (DPS).

The mission of CPO LT is to ensure centralised public procurement and the rational use of public funds, with the vision of being a public institution that offers the most professional centralised public procurement solutions in Lithuania.

Under the public procurement system in Lithuania, CPO LT focuses on the roles related to centralised purchasing activities (centralised purchasing and e-catalogue platform). The Ministry of Economy and Innovation (MoEI) functions as a policy maker of public procurement and the PPO implements its policy including monitoring and professionalisation functions.

Table 1.2. Functions of public procurement system in Lithuania

|

Functions |

MoEI |

PPO |

CPO LT |

Other institution |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Primary policy and legislative functions (*) |

✓ |

|||

|

Secondary policy and regulatory functions (**) |

✓ |

|||

|

International co-ordination functions |

✓ |

✓ |

||

|

Monitoring and compliance assessment functions |

✓ |

|||

|

- Preparation of an annual report on the functioning of the national public procurement system |

✓ |

✓ |

||

|

- Collection of statistics on public procurement system |

✓ |

|||

|

- Auditing, control, inspections, checking of legal compliance |

✓ |

✓ |

||

|

- Authorisation by granting prior approval of procurement process |

✓ |

|||

|

Advisory and operations support functions |

✓ |

|||

|

Professionalisation and capacity-strengthening functions |

✓ |

|||

|

E-procurement platform |

✓ |

✓ |

||

|

Remedies mechanism |

✓ |

|||

|

Centralised purchasing (at national level) |

✓ |

Note: (*) Primary policy and legislative functions refer to the development of procurement policies aimed at setting the overall legal framework of public procurement. Key functions include i) preparing and drafting the primary public procurement regulatory framework; ii) leading the working group in the drafting process; iii) organising the consultation process with the main stakeholders of the procurement system; and iv) taking part in other legislative activities. (**) Secondary policy and regulatory functions refer to the development of regulations to implement the primary law on public procurement in specific areas or to provide implementing tools (operational guidelines, standard documents/templates) in support of the application of the primary law.

Source: Created by the author

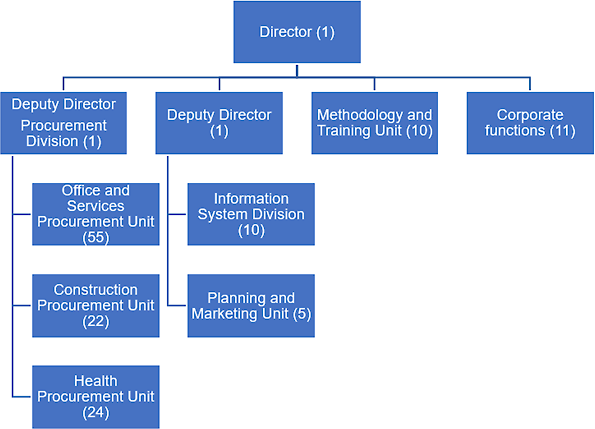

CPO LT has 140 positions assigned to each division/unit. (See Figure 1.2) CPO LT has the four units directly related to the operation of its centralised purchasing activities with the following mandates:

Office and Service Procurement Unit: centralise the procurement of goods and services by developing and administering specific e-catalogue modules;

Construction Procurement Unit: centralise the procurement of construction procurement by developing and administering specific e-catalogue modules;

Health Procurement Unit: centralise procurement related to the health sector by developing and administering specific e-catalogue modules; and

Methodology and Training Unit: providing various methodological assistance to other units, by advising on all public procurement issues, collecting CPO LT good practice, preparing standard procurement documents and standard contracts for FA and DPS used as a template for the development of a particular e-catalogue module.

Figure 1.2. Organisational structure of CPO LT

Note: The number within the parenthesis corresponds to the number of positions. Corporate functions include Finance Unit (2), HR Unit (6), Communication (1), Compliance (1) and Internal process (1)

Source: (CPO LT, n.d.[5])

Currently, CPO LT offers the following schemes related to centralised procurement: (i) Framework agreement (FA), (ii) Dynamic purchasing system (DPS), (iii) Consolidated purchasing by aggregated demands of some CAs, (iv) Procurement agent services (implementing individual procurement processes on behalf of CAs), and (iv) Technical advice on specific aspects of individual procurement processes of CAs (such as providing advice on tender documents etc.).

CPO LT provides FAs and DPS via e-catalogue which are available to all contracting authorities and contracting entities. They are requested to sign the agreement with CPO LT on using its e-catalogue services. The agreement specifies the rights and obligations of each party. As of 30 June 2023, 4 425 contracting authorities (CPO LT, n.d.[6]) and 1 583 suppliers (CPO LT, n.d.[7]) are registered in the CPO LT e-catalogue.

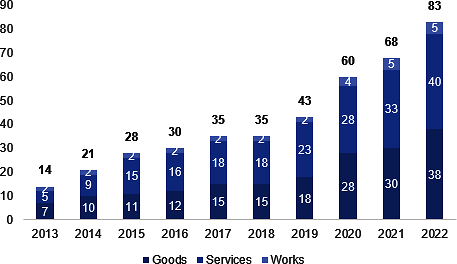

The number of categories available in its e-catalogue increased from 14 (Goods: 7, Services: 5, Works: 2) in 2013 to 83 (Goods: 38, Services: 40, Works: 5) in 2022 (see Figure 1.3). Recently, CPO LT started offering procurement agent services of individual procurement procedures on behalf of contracting authorities. In 2021, the Department of Prisons under the Ministry of Justices carried out a joint procurement with other 9 contracting authorities to procure 356 computers through CPO LT e-catalogue, which generated saving of EUR 16 000 compared with the planned budget (CPO LT, 2021[8])

CPO LT also provides the electronic tool called “Electronic Procurement Centre" (EPC) Catalogue (CPO LT, n.d.[9]). EPC is used for the purchase of renovation/modernisation works and services related to multi-apartment buildings by almost 500 users (communities of multi-apartment buildings and companies managing and maintaining multi-apartment buildings) whose procurement is financed by public funds such as the state budget. The EPC catalogue provides 9 modules related to the modernisation and renovation of apartment buildings: public works, maintenance, solar panel plants and technical services (energy efficiency certificates, investment plans, designs, supervision of construction and building tightness measurements) (CPO LT, n.d.[10])

Figure 1.3. Evolution of the number of categories available in CPO LT e-catalogue (2013-2022)

Source: Prepared by the author based on the information provided by CPO LT

CPO LT also provides consolidated purchasing by aggregating demands of contracting authorities. For example, in 2021, CPO LT has announced a tender to procure approximately 6.5 million pieces of disposable medial face masks by aggregating the demand 122 contracting authorities, which led to 2% saving. (CPO LT, 2021[11]) CPO LT provides procurement agent services by implementing individual procurement processes on behalf of contracting authorities, for example, the procurement of the construction works for the Lithuanian Zoo.

Finance mechanism

Each CPB has its own finance model to administer its operations. (see Box 1.2) CPO LT is financed by two types of financial resources: (i) public funds including the state budget and European Union funds and co-financing, and (ii) revenues from centralised purchasing services including the fees from CPO LT electronic catalogue procurement modules and auxiliary services.

Box 1.2. Finance model among different CPBs

The financing model of CPBs is closely correlated with the status of each entity. In general, activities of CPBs with the status of public institution (e.g., Estonia, Ireland, and Norway) are financed by the state budget. This is the case for the Estonian Health Insurance Fund (EHIF), the Office of Government Procurement (OGP) in Ireland, and the Norwegian Agency for Public and Financial Management. In Ireland, for example, the CPB service provided by the Irish OGP is free of charge even for the procurement agent services. On the other hand, activities of CPBs with the status of the limited company owned by the government are financed by mixed sources. FAs and DPS are financed mainly by user fees, while procurement agent services are paid by client contracting authorities. This is the case for CPO LT, Federal Austrian Procurement Agency (BBG) and Italy Consip. CPO LT receives the state budget as the public institution to finance its minimum administration such as carrying out procurement of all contracting authorities subordinated to the MoEI, centralised purchasing services provided by CPO LT are financed by economic operators or contracting authorities.

Table 1.3. Finance model among different CBPs

|

Services related to centralised procurement |

State budget |

User fees (from CA or supplier?) |

|---|---|---|

|

FA |

Austria (*) Estonia Italy Ireland Norway |

Austria (*) Italy (**) Lithuania (paid by suppliers) |

|

DPS |

Austria (*) Italy Ireland Norway |

Austria (*) Italy Lithuania (paid by suppliers) |

|

Consolidated purchasing (aggregated demands of CAs) |

Estonia Ireland |

|

|

Procurement agent for individual procurement processes (on behalf of CAs) |

||

|

(a) When public buyers are obliged to pass their individual procurement by law |

Lithuania Italy |

|

|

(b) When public buyers decide to do it by their own will |

Ireland |

Austria Italy Lithuania |

|

Technical advice on specific aspects of individual procurement processes of CAs |

Ireland Lithuania (***) |

Austria Lithuania (***) |

Note: The country name refers to one specific CPBs in each country: Lithuania (CPO LT), Austria (Austrian BBG), Estonia (Estonian Health Insurance Fund), Italy (Consip), Ireland (OGP), Norway (Norwegian Agency for Public and Financial Management)

(*) From non-mandatory CA and suppliers. The state budget covers only the losses of BBG, in case BBG does not collect sufficient fees to cover its operations. (**) Charged user fees go to the Ministry of Economy and Finance (MEF) first and then the MEF allocates the budget to Consip so that fees become part of the overall resources made available to Consip. (***) Technical advice for the Ministry of the Economy and Innovation and its subordinate bodies on specific aspects of individual public procurement processes is financed from the state budget. Other CAs will pay from their budget.

Source: Based on the answers to the questionnaire on good practices of CPBs carried out in 2022

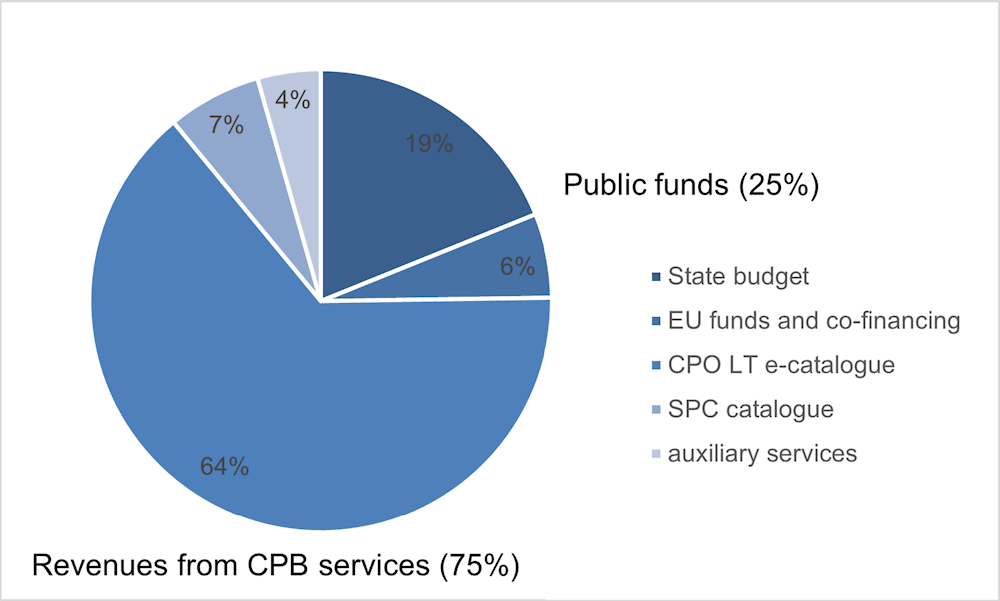

In 2022, public funds accounted for 25% of its total revenues while revenues from its centralised purchasing services accounted for 75%. Fees from CPO LT electronic catalogue accounted for 64% of the total revenues (CPO LT, 2023[12])

Figure 1.4. Revenue structure of CPO LT (2022)

Fees related to e-catalogues (FAs and DPS) are paid by economic operators based on the fixed price per contract or the percentage of the contract amount when the contract is signed. The fees related to auxiliary services are paid by contracting authorities based on the hourly rate regulated by the Order of the Minister of Economy and Innovation and determined after the assessment of the actual costs of the procedures. (Ministry of Economy and Innovation of the Republic of Lithuania, 2023[13])

1.2.2. Ongoing centralisation reform

In September 2021, the Amendment to the Law of the Government of the Republic of Lithuania was approved by the Parliament. Article 30 mentioned public procurement as one of the general functions of the public sector subject to the centralisation reform, in addition to other functions such as accounting, document management, personnel administration, and other auxiliary functions. (Parliament of the Republic of Lithuania, 2021[14])

The amendments to the Law on Public Procurement, which were adopted by the Parliament in October 2021, entered into force in January 2023. (Parliament of the Republic of Lithuania, 2021[15]) The E-catalogue provided by CPO LT remains a key centralisation tool. The amendments require contracting authorities to procure goods, service, and works provided by the e-catalogue of CPO LT for the procurement above EUR 15 000, which was above EUR 10 000 before the amendments. In addition to the requirement to use the CPO LT e-catalogue, procurement procedures above EUR 15 000 are subject to centralised procurement at municipal level from 2023. Options for municipalities are: (i) establish their own CPB, (ii) establish CPBs in cooperation among several municipalities or (iii) conclusion of a contract with an already existing CPB (such as CPO LT). On the other hand, this requirement is optional for the contracting authorities subordinate to the central government and state-owned enterprises. Table 1.4 summarises the main changes and differences in the public procurement centralisation between the previous LPP 2017 and the LPP 2021.

Table 1.4. Overview of centralisation requirements in LPP2017 and LPP2021

|

LPP 2017 |

LPP 2021 |

|

|---|---|---|

|

Obligation to centralise the public procurement or buy through/from a CPB (specific conditions, type/level of CA(s) purchasing categories, etc.) |

- general obligation to buy through the CPB(s) (Art. 82(2)) |

No changes |

|

Exceptions for centralising the public procurement or buying through/from a CPB (specific conditions, type/level of CA(s) purchasing categories, etc.) |

- diplomatic representations, representations at the international organisations, consulates and special missions - supplies, services or works that are offered by the CPB do not meet the needs of the public buyer and - the public buyer can purchase the relevant suppliers, services or works more effectively, rationally using its funds (Art. 82(2)) - procedure without prior publication for low value procurement contract under 10 000 (excl. VAT) (Art. 25(2)) |

Changes regarding the threshold for the procedure without prior publication for low value procurement contract – exception applies to contracts under 15 000 (excl. VAT) (Art. 8 (amends Art. 31(3)(4)) |

|

Justification for using the exception(s) |

Yes. Justification has to be published in the buyers profile (website), if such exists, and stored with other tender documentation as indicated by the LPP (Art. 82(2)) |

Yes. Justification must be provided in the tender documents (Art. 16 (amends Art. 82(2)) |

|

Obligation to establish CPB(s), including specific level CPB(s) (mandatory/discretionary) and description of existing practices (number of CPBs, their level, other) |

- discretionary (Art. 82(6)) |

- discretionary for the Government and institution(s) authorised by the Government (establishing a CPB that manages centralised e-catalogue and their CPBs) (Art. 17 (new Art.821(1)(1)) - discretionary for the state-owned enterprises (establishing sectoral CPBs) (Art. 17 (new Art. 821(1)(3)) - mandatory for municipalities. Options for municipalities: municipality level CPB, CPB established by several municipalities or Conclusion of a contract with already existing CPB (Art. 17 (new Art.821(1)(2)) |

|

Public bodies/entities that have the mandate to establish CPB(s) |

- Government - institution(s) authorised by the Government - municipality councils (Art. 82(6)) |

- Government - institution(s) authorised by the Government (Art. 17 (new Art.821(1)(1)) - municipality councils (Art. 17 (new Art.821(1)(2)) - state owned enterprises (Art. 17 (new Art. 821(1)(3)) |

|

Ways of establishing CPB(s) are indicated in the law (if so, please, list them) |

No |

Yes, for municipalities, as indicated in the section on obligation to establish CPB(s) |

Source: Prepared by the author based on (Parliament of the Republic of Lithuania, 2021[15])

The main objectives of the centralisation strategy of Lithuania are to: (i) increase the level of professionalisation, (ii) minimise the risk of corruption, (iii) gain benefits of consolidation where possible, and (iv) standardise the processes to make them more attractive to business.

The MoEI, as a policy maker of public procurement, was requested to propose the centralisation model of the contracting authorities affiliated with the central government by the end of March 2022. In November 2022, the government of Lithuania approved the Amendment No.1108 to the Resolution No. 50 on the implementation of centralised public procurement (January 19, 2007) to define the overall direction of centralisation over coming years at the level of central government.

Under this plan, starting from 2023, CPO LT will gradually take over the procurement of the health sector and some other contracting authorities at the central government level.

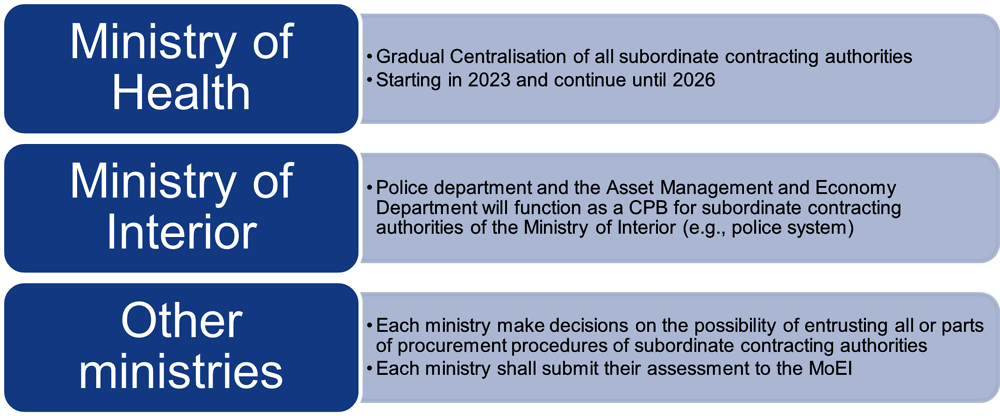

Figure 1.5. Overview of centralisation reform for contracting authorities at central level

Note: Other ministries refer to the following 12 ministries: Ministry of Justice, Ministry of Culture, Ministry of Energy, Ministry of Finance, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Ministry of Education, Science and Sport, Ministry of Economy and Innovation, Ministry of Environment, Ministry of Transport and Communication, Ministry of Agriculture, Ministry of Social and Labour, and Ministry of Defence.

Source: Created by the author based on (The Government of the Republic of Lithuania, 2022[16])

Amendment No.1108 authorised CPO LT to carry out procurement procedures on behalf of contracting authorities at the central government level, in addition to its traditional role to administer e-catalogue to be used for procurement above EUR 15 000 by all the contracting authorities. They also authorised the Asset Management and Economy Department and the Police Department under the Ministry of Interior to function as a CPB for the contracting authorities subordinate to the Ministry of Interior and the procurement related to the police system.

The health sector was chosen as the key sector subject to centralisation reform based on OECD recommendations and the good international practices of other OECD countries. In the health sector, the amendments mandated CPO LT to gradually take over all the public procurement procedures (except low-value procurement below EUR 70 000 excluding VAT for goods and services and EUR 174 000 excluding VAT for public works) of contracting authorities (e.g., hospitals) subordinate to the Ministry of Health. In December 2022, the Ministry of Health submitted to the MoEI the centralisation plan in the health sector with the list of contracting authorities that will entrust their procurement to CPO LT. (Ministry of Health of the Republic of Lithuania, 2022[17]) This process started in January 2023 and will expand gradually through until 2026 through the four phases (see Table 1.5).

Table 1.5. Centralisation plan in the health sector (2023-2026)

|

No. |

Phase I (2023) |

Phase II (2024) |

Phase III (2025) |

Phase IV (2026) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

1 |

Panevėžys Republican Hospital |

Rokiškis Psychiatric Hospital |

Lithuanian Health University of Health Sciences Hospital Kaunas Clinics (*) |

State Patient Agency Health Insurance Fund of Healthcare Ministries |

|

2 |

Republican Šiauliai Hospital |

Vilnius Maternity Hospital Maternity Home |

Vilnius University Hospital Santaros Klinikos (*) |

National Cancer Institute |

|

3 |

Marijampolė Hospital (*) |

Alytus County Tuberculosis hospital |

Kaunas Hospital of Lithuanian University of Health Sciences (*) |

Institute of Hygiene |

|

4 |

Regional Mažeikiai Hospital (*) |

Palanga Children's Rehabilitation Sanatorium "Palangos Gintaras" |

Vilnius University Hospital Žalgiris Clinic (*) |

Republican Centre for Addiction Diseases |

|

5 |

Utena Hospital (*) |

National Forensic Science Service |

Vilnius Psychiatric Hospital (*) |

Radiation Protection Centre |

|

6 |

Alytus County S. Kudirkos Hospital (*) |

National Public Health Centre under the Ministry of Health |

Vilnius University Hospital (*) |

State Medicines Control Authority under the Ministry of Health |

|

7 |

Ukmergė Hospital (*) |

Ministry of Health Centre for Health Emergencies |

Klaipėda University Hospital (**) |

State Service for Accreditation of Health Care Activities under the Ministry of Health |

|

8 |

Regional Telšiai Hospital (*) |

Republican Klaipėda Hospital |

Klaipėda Maritime Hospital (**) |

State Forensic Psychiatry Service under the Ministry of Health |

|

9 |

Tauragė Hospital (*) |

Palanga Rehabilitation Hospital (**) |

National Society Health Laboratory |

|

|

10 |

Lithuanian Medical Library |

|||

|

11 |

National Transplantation Bureau under the Ministry of Health |

|||

|

12 |

Lithuanian Bioethics Committee |

|||

|

13 |

National Blood Centre |

Note: * Subject to the approval of the institution's shareholders, ** Reorganisation by merger of the three institutions launched

In June 2023, CPO LT analysed the result of a survey which was answered by 30 respondents of the seven hospitals that had entrusted their procurement procedures to CPO LT in January 2023. Main feedback is related to the duration of the procurement procedure and the reflection of their needs. Many contracting authorities pointed out that the procurement process takes time. The feedback from some contracting authorities imply that the task related to technical specifications takes time and is not tailored to their needs. For example, technical specifications and/or contract clauses are not tailored to the needs of hospitals. It should be noted, however, that these issues related to technical specifications are also affected by the draft technical specifications prepared by the contracting authorities. In addition, the feedback shows that each hospital has different perspectives on the involvement of their experts in the process, with some hospitals expressing a wish for a lower level of involvement. Under any scenario, the feedbacks from the health sector contracting authorities help CPO LT prepare better for gradually centralising public procurement in the health sector. Therefore, CPO LT could benefit from:

comparing the actual duration of the procurement procedure of CPO LT and contracting authorities.

including in the next survey a more specific question related to the quality and speed of its public procurement procedure for each activity (e.g., definition of technical specifications, tender evaluation, preparation of contract documents); and

Strengthening further its capacity related to health sector procurement and/or recruiting category specialists of the health sector that can verify technical specifications of the health products/services.

For contracting authorities subordinate to other ministries, each ministry is authorised to assess and make decisions on the possibility of entrusting all or parts of their procurement procedures to CPO LT, in coordination with the MoEI. Each ministry is required to assess the performance of its subordinate contracting authorities based on the proposed criteria: scoreboard data (see section 1.5.2 for the methodology of the scoreboard, findings of supervising and auditing bodies, availability of human resources (e.g., the ratio of human resources to public procurements), the complexity of procurement procedures, and other criteria.

By 1 July 2023, the MoEI was required to submit the report on the progress and assessment of the centralisation and, if necessary, proposals for improving the process of centralisation. According to the progress report submitted by the MoEI in June 2023 (Ministry of Economy and Innovation of the Republic of Lithuania, 2023[18]), during the second quarter of 2023, centralised public procurement accounted for 34.6% of the total procurement volume and 22.3% of the total number of procurement procedures, marking a significant increase from 10.0% in 2020 as a share of the total procurement volume in the country. It is expected that the share of centralised public procurement will increase further around the end of 2023, because this data is based on the awarded contracts as of June 2023 and does not include the ongoing centralised procurement procedures. CPO LT continues to be the largest CPB in the country, as the e-catalogue of CPO LT accounted for more than 70% of the total procurement volume of centralised public procurement during the same period.

In total 79 CPBs exist in Lithuania as of June 2023. 74 of these 79 CPBs are regional CPBs, most of which were established after January 2023 to respond to the requirement of public procurement centralisation at the regional level by the Amendments to the Law on Public Procurement which entered into force in January 2023. One typical approach taken by the municipalities was to establish one CPB that carry out procurement procedures of all the contracting authorities (except some sectors such as health) within a municipality and another one for the health sector. For example, the municipality of Prienai established three CPBs for the health sector, care home and the remaining other sectors. No municipalities have transferred all procurement procedures above EUR 15000 to CPO LT, although some individual procedures were transferred to CPO LT through its procurement agent service. (Ministry of Economy and Innovation of the Republic of Lithuania, 2023[18]) As the June 2023 progress report pointed out, it is indispensable to ensure that these 74 regional CPBs function efficiently to comply with the objective of centralisation and the mandatory regulations of centralised public procurement above EUR 15 000. Therefore, Lithuania could continue to monitor the performance of these regional CPBs on a regular basis based on the scoreboard and the performance indicators of CPBs (see Section 1.5 for the performance measurement framework of centralised public procurement).

For the central government level, each ministry made final decisions on centralisation by September 1, 2023, in accordance with their analysis and the feedbacks from the MoEI through the June 2023 progress report. From 2024, each ministry is requested to make decisions and report them to the MoEI each year. Each ministry shall submit to the MoEI the assessment results on the possibility of entrusting all or parts of their procurement procedures to CPO LT by March 1 each year, and by September 1 make the final decisions on the centralisation of procurement by their subordinate contracting authorities for upcoming years.

Given the fact that the number of CPBs increased drastically in January 2023, Lithuania could consider the possibility of reinforcing a national CPB network to coordinate and exchange centralised purchasing practices. CPO LT established CPO LT Forum in July 2020 as a community of practice in which CPBs and CPO LT clients such as contracting authorities and economic operators can share experiences in using CPO LT services and ask questions. However, this platform has not been often used so far. Lithuania could not only promote the use of this platform but also establish a national CPB network to organise a regular conference to coordinate centralised purchasing and exchanges experiences among 79 CPBs. Countries like Italy and Ireland established a national CPB network to discuss common issues and share knowledge related to centralisation among CPBs. For example, the Procurement Executive of Ireland is a forum made up of the five CPBs (OGP, Education, Health, Local Government and Defence). Italy has a national CPB network to coordinate with regional CPBs.

1.3. How to strengthen CPO LT

1.3.1. SWOT analysis and growth strategy based on the organisational strategy

This section overviews how CPO LT can maximise the benefits and impacts of the ongoing centralisation of public procurement to contribute further to improving the overall performance of the public procurement system in Lithuania through their centralised purchasing services.

Since 2015, CPO LT has its three-year organisational strategy approved by the MoEI. The strategy defines its mission, vision, values and principles of operation, the strategic goals, the indicators for measuring their achievement, and the main actions to achieve them. The latest strategy is for the period 2021-2023. The three-year strategy is implemented through the annual activity plan developed for each year, the latest one being the activity plan of CPO LT for 2023. (Ministry of Economy and Innovation of the Republic of Lithuania, 2023[19])

CPO’s strategic goals are (i) to maximise the financial and social benefits that Lithuania can gain from the use of a central contracting authority for procurement and (ii) to promote the procurement of environmentally friendly goods, services or works. The organisational strategy specifies the key performance indicators (KPIs) to measure these strategic goals (see Table 1.6).

Table 1.6. Key performance indicators of CPO LT (2021-2023)

|

Indicators |

Benchmark (2020) |

Target by 2023 |

|---|---|---|

|

Saving from CPO LT centralised procurement (EUR million) |

EUR 75 million |

EUR 100 million |

|

Number of suppliers in CPO LT e-catalogue |

860 |

1 060 |

|

Share of green public procurement in CPO LT centralised procurement (value, %) |

13.9% |

25% |

|

Share of socially responsible public procurement in CPO LT centralised procurement (value, %) |

3.4% |

10% |

|

Procurement carried out through CPO LT e-catalogue, (EUR million) |

EUR 395.4 million |

EUR 506 million |

|

Percentage of contracts awarded to SMEs in CPO LT e-catalogue (by value / by number of contracts, %) |

32.7% / 47.9% |

50% / 60% |

|

Trust in CPO LT (percentage of people who believe that CPO LT's activities are transparent and reliable), % |

95% |

97% |

|

Number of contracting authorities that have entrusted CPO LT to carry out part or all of their public procurement procedures |

8 |

45 |

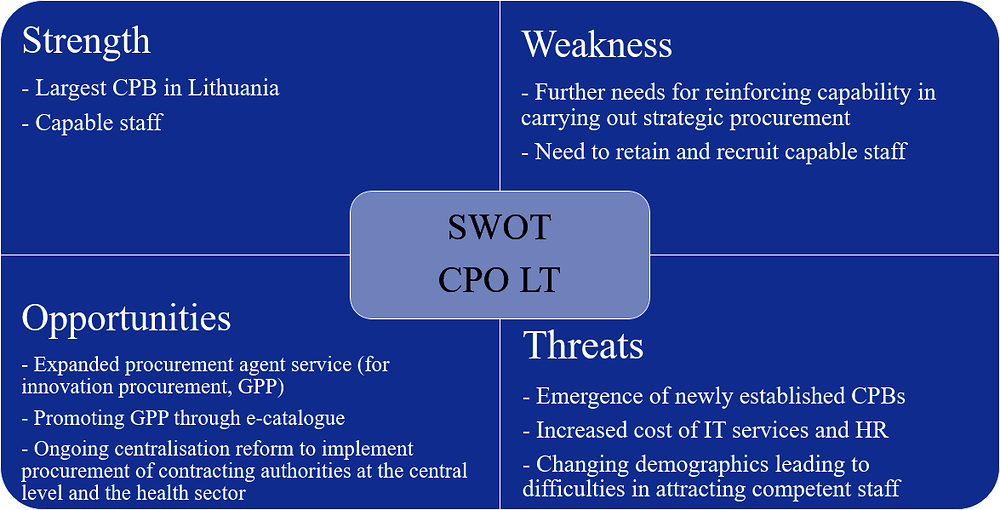

In its operational strategy (2021-2023), CPO LT analysed the internal and external environments that will affect the operation of the organisation. CPO LT also identified many opportunities for CPO LT as a result of this analysis. These opportunities include, but are not limited to, further integration of environmental, social and energy efficiency criteria as well as the Best Price Quality Ratio (BPQR) criteria into the CPO e-catalogue, attracting contracting authorities that entrust CPO LT to carry out some or all of their public procurement procedures through its procurement agent services, encouraging public entities to initiate innovative procurement through advice and training. (Ministry of Economy and Innovation of the Republic of Lithuania, 2021[20])

Figure 1.6 shows the SWOT analysis of CPO LT which also considers the factors analysed in the operation strategy (2021-2023). SWOT (strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats) analysis is a framework to assess the level of the competitive position of the organisation based on internal and external factors. Strength and weakness are based on internal factors which are within the control of the organisation, while opportunities and threats are external or given factors which are beyond the control of the organisation.

Figure 1.6. SWOT analysis of CPO LT

Note: Strength and weakness are based on the internal factor (within the control of the organisation), while opportunities and threats are external or given factors (beyond the control of the organisation).

Source: Prepared by the author

Strengh refers to internal factors favorable to the organisation. CPT LT is the largest CPB in Lithuania that represented approximately 90% of centralised procurement carried out in Lithuania in 2020 (see Table 1.1) In addition, CPO LT has an adequate capability level. Opportunities refer to external factors favorable to the organisation, while threats refer to external factors which might not be favorable to the organisation. In the case of CPO LT, the ongoing centralisation reform of public procurement brings both opportunities and threats, with more weight being placed on opportunities. For example, the centralisation reform at the central level and the health sector will expand the portfolio of CPO LT. The targets set for innovation procurement (20%) and green public procurement (55%) in the National Progress Plan (2021-2030) will drive more demand for CPO LT services such as the procurement agent services of innovation procurement and the e-catalogue that integrates green criteria and/or life cycle cost (The Government of the Republic of Lithuania, 2020[21]) It is worth mentioning that the Government of the Republic of Lithuania also adopted the Resolution No. 1133 on the determination and implementation of green public procurement objective, and set up the target of 100% starting from 2023. (The Government of the Republic of Lithuania, 2021[22])

The threat arising from the ongoing centralisation reform could be newly established CPBs. However, CPO LT will continue to keep its position as the largest CPB given the current high share of the total centralised purchasing in the country. Other threats are related to the macroeconomic factors which were identified in the operational strategy (2021-2023). These include the increased cost of IT services to develop e-catalogue, the increased human cost, and Lithuania’s changing demographics that increase competition in the labour market and difficulties in attracting competent professionals.

To maximise the opportunities, CPO LT needs to address potential weaknesses, and internal factors which might not be favourable to the organisation. CPO LT should further reinforce the capability of its workforce to provide high-quality procurement agent services of strategic procurement such as innovation procurement. Indeed, the competence related to innovation procurement was identified as the weakest competence not only for the overall average of CPBs but also for CPO LT in the ProcurCompEU survey carried out to 6 CPBs in Lithuania including CPO LT. (see Section 1.4.4 for more details on the result of the ProcurCompEU survey) In addition, CPO LT needs to continue to retain and recruit capable officials to prepare for the expansion of the portfolio due to the centralisation reform at the central level and the health sector.

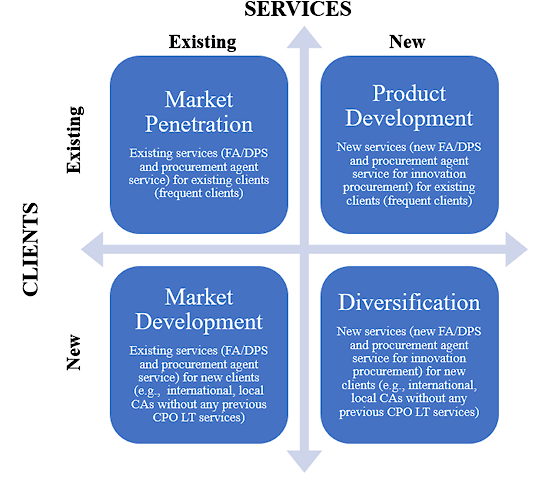

The SWOT analysis revealed that CPO LT, as the largest CPB in Lithuania, has a high potential to grow further to contribute to improving the overall performance of public procurement in Lithuania by expanding their operations, building upon the strength and opportunities identified in the SWOT analysis. Figure 1.7 shows the potential growth options of CPO LT that adapted the Ansoff matrix to identify the organisational growth strategy (see Box 1.3 or the Ansoff matrix).

To apply this framework to the context of CPO LT, the two principal axes are used: clients (instead of “markets” in the original framework) and services (instead of “products” in the original framework). Each dimension of these two principal axes was divided into new (new client and new services) and existing (current client and current services) whose combination led to the four matrixes. For the purpose of this analysis, existing clients refer to existing clients of CPO LT that frequently use its services such as FA/DPS and procurement agent services, while new clients could be defined as local (or even international) clients who rarely or have never used CPO LT services. Existing services refer to the FA and DPS already available and the current procurement agent services, while new services refer to the new FA and DPS as well as the procurement agent services oriented to strategic procurement such as innovation procurement. It is worth mentioning that procurement agent services have high potential, because auxiliary services including procurement agent services accounted for only 4% of the total revenue of CPO LT in 2022 in comparison with 74% of the revenues from e-catalogue (see Figure 1.4). In particular, procurement agent services for innovation procurement are promising, as they have never been provided but can expect more demand due to the national target of 20%.

As of 2023, CPO LT provided 44 contracting authorities (expected 75 contracting authorities by the end of this year) with procurement service. This means that approximately 1% of the contracting authorities that use CPO LT services (44 out of 4 418 contracting authorities) have used procurement agent services of CPO LT. However, none of these 44 contracting authorities entrusted CPO LT to carry out innovation procurement procedures. On the other hand, Hansel, a central purchasing body of Finland, provided 79 different contracting authorities with 206 procurement agent services in 2022. In addition, almost 20% of these procurement services (41 out of 206) were related to innovative aspects. Therefore, there is still large room for CPO LT to promote its procurement agent services among its clients through innovation procurement aspects.

Under the market penetration strategy, CPO LT can promote existing services to existing clients. This could include, for example, promoting the uptake of relatively less used FA and DPS among existing clients. Under the market development strategy, CPO LT can promote existing services to new clients. This could include, for example, promoting procurement agent services to the contracting authorities which have used many FA and DPS services but have not used procurement agent services, and vice versa, or promoting FA and DPS to international contracting authorities. Under the product development, CPO LT can promote new services to existing clients. This could include, for example, promoting procurement agent services of innovation procurement or FA/DPS with green criteria among the existing clients who are frequent users of CPO LT services and shows high-level of trust and satisfaction in the quality CPO LT services. Lastly, under the diversification strategy, which are the most challenging for the implementation, CPO LT can promote new services to new clients. For example, CPO LT can promote procurement agent services of innovation procurement to local or international contracting authorities that have never used CPO LT services. It should be mentioned, however, cultivating new clients with new services involve the highest level of complication, so this diversification strategy could be pursued after the successful implementation of the market development strategy (offering existing services to new clients to gain trust) and/or the product development strategy (assuring new services to existing clients). To define the growth strategy, CPO LT could analyse the current uptake of its services by each client to define the growth strategy.

Figure 1.7. Growth options of CPO LT

Box 1.3. Ansoff matrix to identify growth strategy

Ansoff matrix was originally developed by Igor Ansoff as a useful framework that organisations can use to identify four possible growth options/strategies with the two main axis: market (existing or new markets) and products (existing or new products).

Market penetration strategy is a strategy to grow by increasing businesses with its current customers or by finding new customers (with similar characteristics of the current customers within the existing markets), for example, through decreasing the price and expanding the share in the existing market.

Market development strategy is a strategy to adapt its present product (generally with some modification in the product characteristics) to new types of customers, for example, through targeting international markets and new customer segments within the country.

Product development strategy is a strategy to develop new products with different characteristics that will improve the performance of the current customers.

Diversification strategy is the final and most challenging strategy in that it intends to develop new products with different characteristics that will improve the performance of the current customers, and to promote them not only to current customers but also to new customers.

Figure 1.8. Ansoff matrix

In addition, CPO LT could consider the possibility of increasing the number of the position related to the marketing and customer relations or more broadly assigning marketing related functions to the existing staff. Like many other CPBs, CPO LT organise many events such as open days and webinars to raise awareness of CPO LT services among its clients (contracting authorities and economic operators). Given that CPO LT estimates to have more clients in the future, CPO LT could reinforce its customer relationship model. For example, Hansel, a Finnish national CPB, has a marketing team of five staff, and employs ten Key Account Managers who are in charge of strengthening the customer relationship by meeting with them regularly and/or by sending the automatic e-mail to raise awareness of its services among its 1 433 clients.

This section overviewed the current competitive position of CPO LT through the SWOT analysis and future growth options through the Ansoff matrix. However, these growth options will work only when CPO LT successfully addresses the weakness identified in the SWOT analysis.

The next section briefly overviews the two main factors that CPO LT should address to overcome its weaknesses: retain and recruit capable staff and reinforcing capabilities in carrying out strategic procurement.

1.3.2. Strengthening the capability and how to retain/attract capable staff

CPO LT recognises the relevance of increasing the capability of its procurement workforce, as it has the value “Competence and professionalism - promoting the continuous development of staff knowledge, skills and professional competence” as one of the five core organisational values. (Ministry of Economy and Innovation of the Republic of Lithuania, 2021[20])

CPO LT needs to professionalise its public procurement workforce further to reap the maximum benefits from the identified opportunities such as the procurement agent services of innovation procurement, the e-catalogue that integrates green criteria and/or life cycle cost, and the increased portfolio arising from the ongoing centralisation reform at the central government level and the health sector.

In particular, the self-assessment result of the ProcurCompEU survey identified competence related to innovation procurement as the one with the lowest average score of all the 30 competences. In general, it is expected that CPBs have good general procurement practices and be an example to all the contracting authorities. Therefore, CPO LT needs to reinforce its capacity related to innovation procurement to promote the uptake of innovation procurement in Lithuania through its procurement agent services. The capability-building initiative related to innovation professionals will be discussed in section 2.4. because reinforcing its capability is a common challenge across all the contracting authorities in the country. CPO LT should engage in cooperation with the PPO and Innovation Agency to get prepared to respond to innovation procurement needs from contracting authorities and contribute to promoting innovation procurement, while reinforcing its capability related to innovation procurement.

CPO LT could also consider the possibility of developing its own competency model. A competency model maps critical skills and their capability levels which are required for the overall strategic direction of an organisation. It allows procurement officials to identify their skill gaps and can be used for human resource management purposes: recruitment, promotion and training on the skills and competences. (OECD, 2023[24]) It will contribute to building its image as a competent, credible and transparent institution and as an employer of choice in order to recruit competent professionals, which was targeted in its organisational strategy (2021-2023). (Ministry of Economy and Innovation of the Republic of Lithuania, 2021[20]) CPO LT can develop its own competence matrix by adapting the ProcurCompEU competency matrix into the context of CPO LT. For example, the Office of Government Procurement of Ireland is developing a competency model for its staff working on centralised procurement by adapting procurement specific competences of ProcurCompEU to the specific needs related to centralised public procurement while aligning soft competences with the ones of the Civil Service Model. In 2021, the OECD collaborated with ChileCompra, a public procurement authority and central purchasing body of Chile, to renovate its national competency matrix by adapting the ProcurCompEU competency matrix into the context of Chile. The key steps undertaken were benchmarking exercise, adaptation of the competency matrix, design and launch of the survey, and the finalisation of the competency matrix (see Box 1.4).

Box 1.4. Experience of ChileCompra in revamping the national competency matrix

In 2021, ChileCompra decided to revamp the competency matrix of the public procurement workforce linked with its national certification framework to further modernise its public procurement system. To implement this reform, ChileCompra showed a strong interest in leveraging ProcurCompEU under the pilot project of the OECD financed by the European Commission. The following steps were taken to implement this reform:

Benchmarking exercise

Since Chile had its own competency matrix of the public procurement workforce, the benchmarking exercises aimed at adopting the elements of ProcurCompEU (competency itself and proficiency description) which are relevant to the local context of Chile. At the beginning of this pilot implementation phase, ChileCompra carried out this benchmarking exercise by referring to the competency matrix used in the current version. As a result, ChileCompra identified 15 competences that are aligned with the ones of ProcurCompEU and/or could be adapted to the local context of Chile. ChileCompra also streamlined the structure of the competency matrix, built upon the ProcurCompEU competency matrix. Then, ChileCompra prepared the updated competency matrix with these 15 competences to share it with the OECD team in June 2021.

Adaptation of the competency matrix

The OECD reviewed the updated competency matrix and suggested some improvements of the proficiency descriptions by adopting some descriptions of the ProcurCompEU competency matrix. The OECD also proposed to include two new competencies on “Tender document” (including the elements of contract award criteria) and “Sustainable development”. The adoption of these two additional competences aims at further enhancing the implementation of sustainable procurement (green public procurement, SMEs development, social and inclusive procurement including gender), which ChileCompra has been pursuing for a long time but which were absent from the competences identified in the national certification scheme.

Design of the survey in EUSurvey

ChileCompra selected 100 public procurement officials working in 15 different contracting authorities. These selected 15 contracting authorities consist of 12 large contracting authorities and 3 small ones. The survey was prepared in the EUSurvey platform. Questions were aligned with the tailored competency matrix. Additional questions were included notably on the identification of the contracting authority in which the respondent works, ProcurCompEU competences that were not included in the selected 17 competences but which could be included in the future, and a free text entry to receive feedback from respondents on the competency matrix. The survey had first been tested with 5 officials of ChileCompra to ensure it would perform as intended

Organising the webinar to launch the survey

ChileCompra and the OECD invited selected 100 public procurement officials of 15 contracting authorities to the webinar held on November 26, 2021 to launch the survey. During the webinar, ChileCompra and the OECD explained the ProcurCompEU and the objective of this pilot project and survey. A demonstration of the survey was provided to participants in order to explain how it worked and how to respond to the various questions. The survey was closed on December 31, 2021, with a response rate of 86%.

Discussing the results

The OECD analysed responses to the survey by integrating them into the self-assessment calculation tool. The OECD organised a meeting with ChileCompra on January 12, 2022 in order to discuss main results, key findings and recommendations. The results helped ChileCompra and the OECD to slightly fine-tune the competency matrix.

ChileCompra benefited from revamping the competency matrix by adopting ProcurCompEU competences to its local context and relevance. In addition, the result of the self-assessment survey achieved its two main objectives: (i) identifying priorities for the development and reinforcement of training courses of 17 competences linked with the certification framework and (ii) obtaining the feedbacks on the draft competency matrix including the new competences to be included in the future.

Source: (OECD, 2022[25])

As a measure to attract and retain capable staff, CPO LT established an onboard programme for a newcomer which consists of the training programme and the mentoring system (see Box 1.5).

Box 1.5. CPO LT onboard programme for newcomers

CPO LT organises an onboard programme for newcomers that consists of the two elements: the introductory training programme and mentor programme.

The introductory training, with the duration of 4 hours, cover the basic topics such as (i) Law on Public Procurement, (ii) CPO LT website, (iii) CPO LT e-catalogue (functions and public procurement process), (iv) ISO standard, centralised public procurement schemes of CPO LT, and (vi) CPO LT document management system. CPO LT also prepared the document for newcomers "Newcomer ABC."

In the mentor programme, one mentor, who could be a line manager, is assigned to each newcomer for three months during the probationary period. The mentor helps a newcomer get familiar with the function of CPO LT and acquire the necessary knowledge and skills for the job. During this period, the mentor or the line manager (in case he or she is not a mentor) shall provide feedback at least once per week to the mentee by discussing and evaluating the performance of a newcomer. Around the end of the mentor programme, the line manager provides a newcomer with the final assessment through the CPO LT internal management system on the newcomer’s ability to carry out the tasks of CPO LT and his/her readiness to work independently, with the following four levels:

Very good: a newcomer has completed all tasks and is able to work independently;

Good: a newcomer has completed substantially all the tasks and is able to perform at least two-thirds of the functions independently;

Satisfactory: a newcomer has completed 50% of the tasks and is able to perform at least half of the assigned functions independently;

Unsatisfactory if the staff member has not completed more than 50 % of the tasks. (in this case, the Director of CPO LT may take a decision to terminate the contract)

Source: Information provided by CPO LT

Currently, CPO LT applies remunerations based on performance (for example, up to 15% for extra tasks). To further motivate its procurement workforce, CPO LT could consider the possibility of improving its performance bonus system based on good international practice if the budget allows for it and the practice can be allowed from the public sector perspective. This will help CPO LT to be more competitive in the labour market to attract competent officials. Practices related to performance bonuses are still limited in the public sector. (OECD, 2023[24]) Hansel, a central purchasing body of Finland, provides insights on a performance bonus mechanism, which consists of the performance bonus up to 15% of the annual salary and a one-off set bonus between EUR 300 and EUR 3000 for particularly good performance. (see Box 1.6)

Box 1.6. Performance-based bonus at Hansel in Finland

Hansel Ltd acts as a central purchasing body for central and local governments in Finland. It is a non-profit limited company which is owned by the State (65%) and the Association of Finnish Local and Regional Authorities (35%), and finances its operations through service fees of FA/DPS paid by the suppliers based on the value of purchases. Currently, the maximum service fee that can be charged is 1,5 % of the contract value with an average of 0.83% in 2022. In 2022, 1 433 contracting authorities and 981 economic suppliers used the services provided by Hansel. Hansel provides competitive salaries which are closer to the private sector.

Hansel has introduced the performance bonus mechanism to motivate its officials, which is a unique initiative in the public sector. There are two types of performance bonuses: performance bonus of up to 15% of the annual salary and a one-off set bonus between EUR 300 and EUR 3000 for particularly good performance. The performance bonus mechanism is mainly financed by the revenues from service fees (such as user fees from FA/DPS).

The performance bonus can be paid up to 15% of the annual salary of each staff. For members of the management team, the maximum bonus can be up to 30% of the annual salary, if the performance has been exceptionally good. Performance bonus assessments are based on contract usage, customer satisfaction and contribution to the organisational strategy. In 2022, EUR 905 000 were paid as the performance bonus with an average rate of 12.5% (against the possible maximum 15%).

In addition, Hansel employees may receive a one-off bonus between EUR 300 and EUR 3 000 for particularly good performance. The managing director decides on the award of a one-off bonus based on a proposal from the employee’s supervisor. In 2022, the total EUR 8 600 of one-off bonus was awarded to 13 employees.

Source: (Hansel, 2023[26]), (Hansel, n.d.[27]) and the information provided by Hansel

1.4. Capability (ProcurCompEU result): Key takeaways from ProcurCompEU survey

This section presents the key takeaways and results of the survey of the European competency framework for public procurement professionals (ProcurCompEU), which was carried out with 99 procurement officials of 6 CPBs in Lithuania in 2022: (i) CPO LT, (ii) the Asset Management and Economy Department under the Ministry of Interior, (iii) Prison Department under the Ministry of Justice, (iv) Kaunas City Municipality Administration, (v) Vilnius City Municipality Administration and (vi) Defence Material Agency under the Ministry of Defence.

1.4.1. ProcurCompEU as a tool to assess the capability level

It is critical to identify and assess the gaps in capabilities and skills of the public procurement workforce to develop a better professionalisation strategy and a solid capacity-building system. ProcurCompEU is a practical tool to facilitate these assessments. ProcurCompEU was launched by the European Commission in December 2020, in order to support the professionalisation of public procurement. ProcurCompEU provides practical tools to advance the professionalisation agenda such as the competency matrix including 30 key competences for public buyers, a self-assessment tool, and a generic training curriculum. (See Box 1.7)

Box 1.7. European competency framework for public procurement professionals (ProcurCompEU)

ProcurCompEU is a tool designed by the European Commission to support the professionalisation of public procurement. ProcurCompEU consists of three elements:

Competency Matrix, which defines 30 procurement-related and soft competences along four proficiency levels;

Self-Assessment Tool that allows users to set targets for the different competences and assess their proficiency levels against them and identify any gaps;

Generic training curriculum which lists all learning outcomes that public procurement professionals should know and be able to demonstrate after having attended a training for a certain proficiency level.

The Competency Matrix describes 30 competences (knowledge, skills and attitudes) that public procurement professionals should demonstrate in order to perform their job effectively and efficiently and carry out public procurement procedures that bring value for money. The competences are grouped in two main categories: procurement specific competences, and soft competences. The categories are then divided into six clusters, three per category:

Procurement-specific competences (19 competences):

Horizontal: 9 competences applicable to all stages of the public procurement lifecycle

Pre-award: 6 competences required to perform all the tasks and activities taking place before the award of a public contract

Post-award: 4 competences necessary for the contract management after the award of a public contract.

Soft competences (11 competences):

Personal: 4 competences on behaviours, skills and attributes that public procurement professionals should possess, as well as the mind-set that they should display according to their job profile

People: 3 competences enabling public procurement professionals to interact and cooperate with other professionals, and to do so in the most professional manner

Performance: 4 competences public procurement professionals need to have in order to increase value for money in public procurement procedures

Each competence is described along four proficiency levels based on the breadth of knowledge and skills: Basic, Intermediate, Advanced, and Expert.

The ProcurCompEU Self-Assessment Tool is composed of several key elements:

A self-assessment questionnaire

Templates for job profiles

A calculation tool for computing individual and organisational assessment results.

The ProcurCompEU Reference Training Curriculum lists all learning outcomes that public procurement professionals should know and be able to demonstrate after having attended a training for a certain proficiency level.

ProcurCompEU is a quite flexible, voluntary and customisable tool. Getting value from ProcurCompEU does not require using each and every component of the framework, nor does it require the use of each and every competence defined in the ProcurCompEU Competency Matrix.

Source: (European Commission, 2020[28])

1.4.2. ProcurCompEU survey structure

The ProcurCompEU survey was prepared in the EC digital platform (EUSurvey) by adapting the standardised survey questionnaire of ProcurCompEU to the Lithuanian context. It was carried out to public procurement officials in 99 officials at 6 CPBs in Lithuania.

The survey aimed at helping each CPB to identify the current capability level of their workforce and competences that need more capacity building, by:

Measuring the organisational maturity of participating CPBs by ranking each of the 30 competences as follow:

Calculating the average score of all the participants (all the participating 6 CPBs);

Calculating the average score of all the participants (each CPB);

Calculating the breakdown by each division; and

Collecting the feedbacks on capacity-building needs of the participants.

The survey consisted of four sections:

Section I General questions: Information on the respondent such as the current position and experiences in public procurement;

Section II Public procurement competences: self-assessment of the current level for the 19 procurement specific competences;

Section III Soft competences: Assessment of the current level for the 11 soft competences; and

Section IV Feedback on capacity-building needs: Selection of top 3 competences that need more capability-building activities in the opinion of the respondent.

In Section II and III, the participants were requested to self-assess their proficiency levels of knowledge and skills for 30 competences from the following levels that were converted to points (0 to 4):

Less than basic: 0 point

Basic: 1 point

Intermediary: 2 points

Advanced: 3 points

Expert: 4 points

A webinar to launch the survey was organised by the OECD on April 13, 2022, in order to explain the purpose and structure of the exercise to the participants. The survey was closed on May 18, 2022.

1.4.3. Profiles of participants of ProcurCompEU survey

This section shows the basic profiles of the 99 officials that participated in the ProcurCompEU survey from the 6 CPBs. (See Table 1.7)

Table 1.7. Participants of the ProcurCompEU survey

|

Name of entity / division |

Participants |

|---|---|

|

1. CPO LT |

43 |

|

1.1. CPO LT - Construction procurement division |

9 |

|

1.2. CPO LT - Methodology and training division |

5 |

|

1.3. CPO LT - Health procurement division |

9 |

|

1.4. CPO LT - Bureau and activity services procurement division |

20 |

|

2. Asset Management and Economy Department under the Ministry of Interior |

9 |

|

3. Prison Department under the Ministry of Justice |

8 |

|

4. Kaunas city municipality administration |

9 |

|

5. Vilnius city municipality administration |

6 |

|

5.1. Vilnius CMA - Procurement procedures subdivision |

1 |

|

5.2. Vilnius CMA - Public procurement division |

2 |

|

5.3. Vilnius CMA - Document preparation subdivision |

2 |

|

5.4. Vilnius CMA - Centralized procurement subdivision |

1 |

|

6. Defence Material Agency under the Ministry of Defence |

24 |

|

6.1. DMA - 1st procurement organization division |

5 |

|

6.2. DMA - 2nd procurement organization division |

6 |

|

6.3. DMA - 3rd procurement organization division |

6 |

|

6.4. DMA - 4th procurement organization division |

7 |

|

TOTAL |

99 |

Source: ProcurCompEU survey result for 6 CPBs in Lithuania (July 2022)

The followings are the snapshots of the 99 participants:

93.9% (93 out of 99 officials) work full-time on public procurement.

Average experiences in the current position are 35.0 months

Average experiences in public procurement are 104.6 months

1.4.4. ProcurCompEU survey results

The OECD shared the key findings from the analysis of the aggregated self-assessment results of the 99 participants during a workshop held in Vilnius on May 27, 2022. Then, the survey results for each of the 6 CPBs were sent to each institution individually in July 2022, in order to maintain the confidentiality of their individual results. The OECD also organised a webinar for CPO LT, the CPBs with the largest pool of participation (43 officials), in order to explain the key findings. This section only shows the key findings of the aggregated result of the 99 participants, which are still useful to meet the objective of identifying the competences that need more capacity building on a country-wide level.

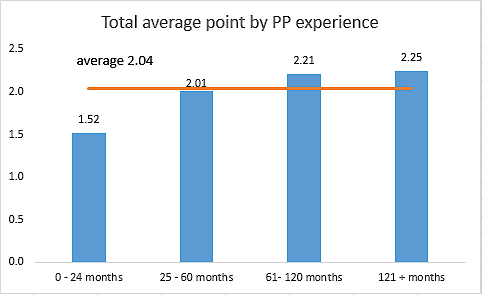

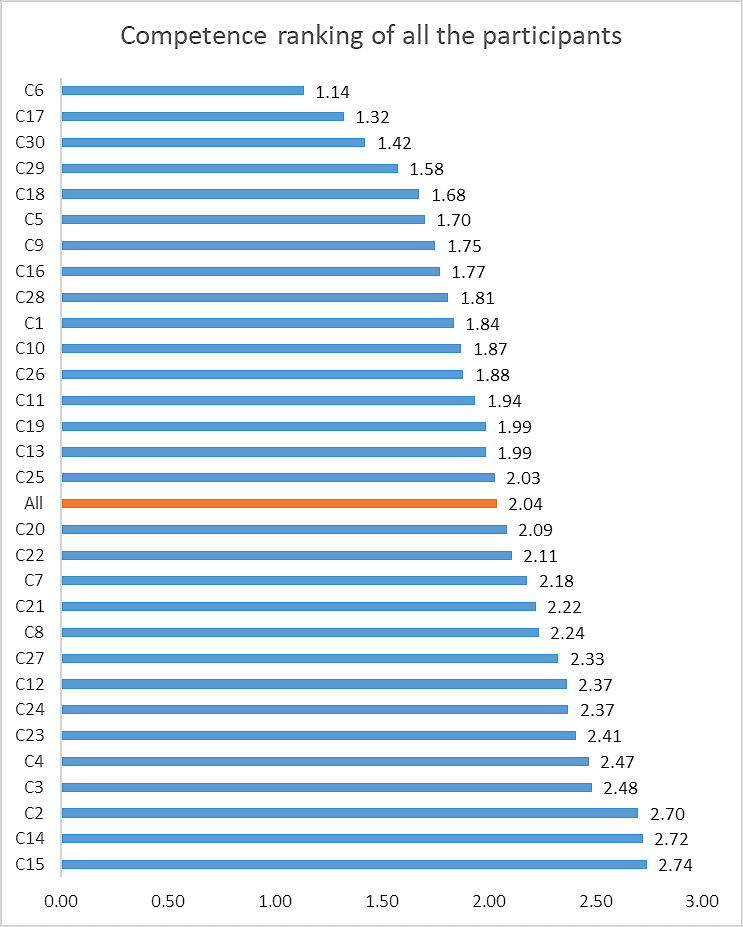

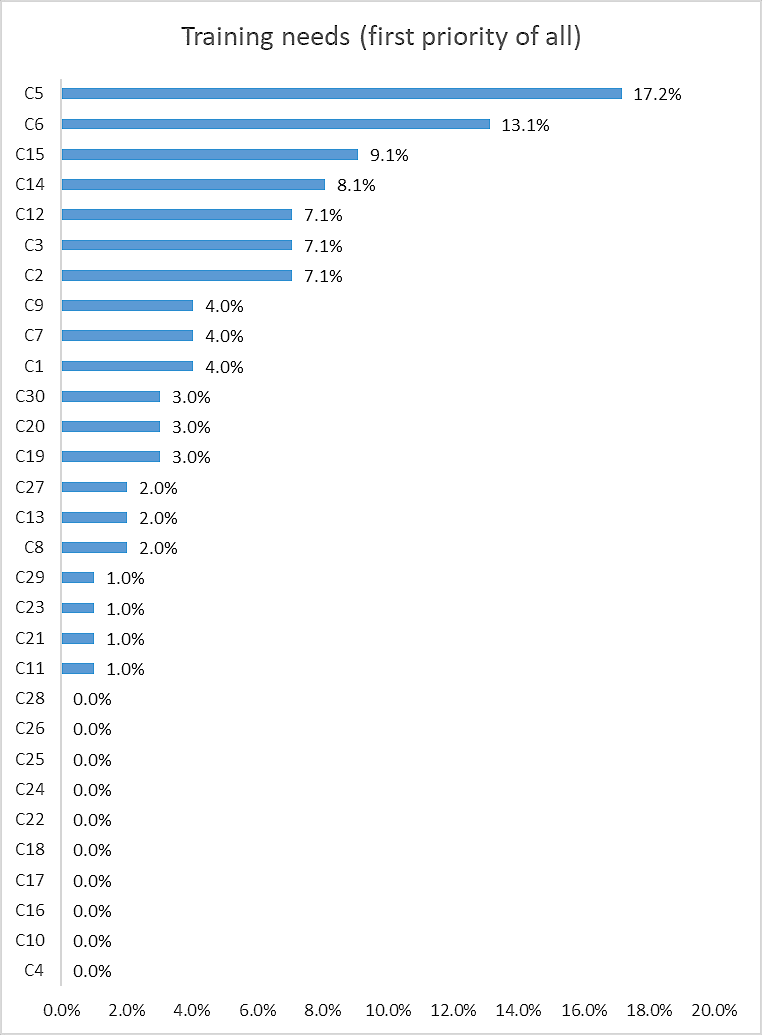

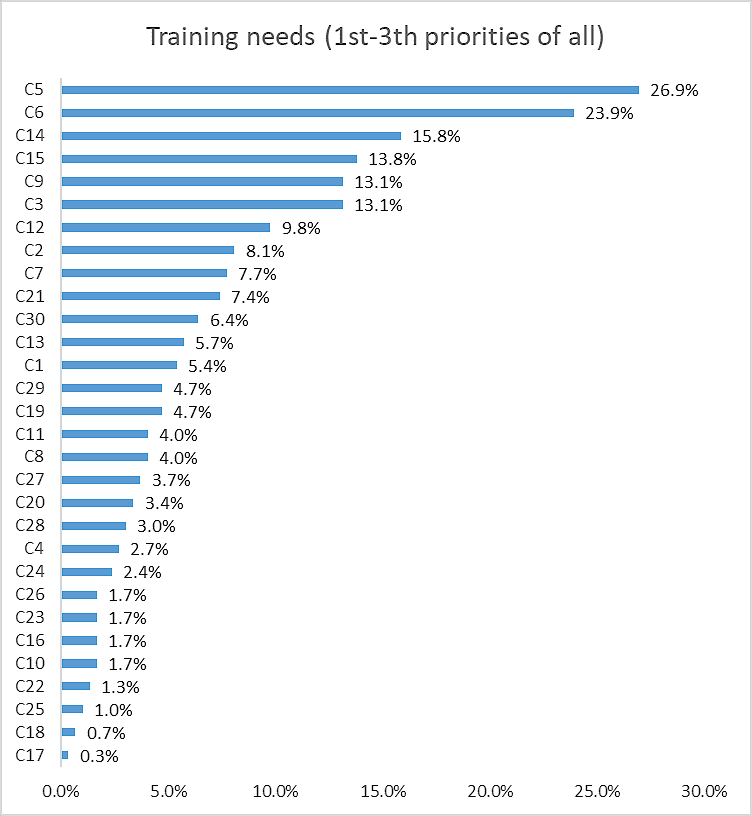

The total average point of the 30 competences of all the 99 participants was 2.04. The total average point of procurement-specific competences (No. 1-19) amounted to 2.05, while the one for the soft competences (No. 20-30) was 2.02. Figure 1.9 shows that the capability level increases proportionally with more professional experiences in public procurement.

Figure 1.9. Total average point by PP experience and by job profile

Figure 1.10 shows the average points of all the 99 participants by competence in ascending order. The self-assessment result identified C6 (Innovation Procurement) as the weakest competence of the participants with the lowest average point of 1.14, followed by C17 (Certification and payment) and C30 (Risk management and internal control).

Figure 1.10. Average points of all the participants by competence

Note: C1 Planning, C2 Lifecycle, C3 Legislation, C4 e-Procurement and other IT tools, C5 Sustainable procurement, C6 Innovation procurement, C7 Category specific, C8 Supplier management, C9 Negotiations, C10 Needs assessment, C11 Market analysis & engagement, C12 Procurement strategy, C13 Technical specifications, C14 Tender documentation, C15 Tender evaluation, C16 Contract management, C17 Certification and payment, C18 Reporting and evaluation, C19 Conflict resolution / mediation, C20 Adaptability and modernisation, C21 Analytical and critical thinking, C22 Communication, C23 Ethics and compliance, C24 Collaboration, C25 Stakeholder relationship management

C26 Team management and leadership, C27 Organisational awareness, C28 Project management, C29 Performance orientation, C30 Risk management and internal control

Source: ProcurCompEU survey result for 6 CPBs in Lithuania (July 2022)

In 2020, the government of Lithuania published its National Progress Plan (2021 – 2030), which set the target that 20% of the value of all public procurement needs to go to innovation procurement by the year 2030. The country plans to achieve this by steadily increasing the share of procurement that is spent on public procurement of innovative solutions and on pre-commercial procurement. (The Government of the Republic of Lithuania, 2020[21]) Therefore, it is necessary to increase the competence C6 (Innovation Procurement).