Decisions concerning large infrastructure investment depend greatly on expectations about traffic growth, as they require long-term financial and political commitment. Given the uncertainty about the scope of the Middle Corridor’s long-term traffic volumes, current road and rail infrastructure, supported by ongoing reforms could prove sufficient to absorb increased traffic in the short term. However, governments should prioritise the resolution of existing capacity gaps that reduce the route’s attractiveness by generating long and variable delays. In particular, developing multimodal (rail-road) capacity at border crossing points and ports, and building fleet capacity in the Caspian Sea would support developing regional trade flows.

Realising the Potential of the Middle Corridor

4. Improving the Middle Corridor’s attractiveness requires investing in port and rail infrastructure, with a focus on multimodality

Abstract

Governments across the region have invested in road, rail, and maritime infrastructure in recent years

Azerbaijan, Georgia, Kazakhstan, and Türkiye have been developing their seaports

Historically, Azerbaijan’s port of Baku has been the largest on the Caspian Sea, handling about 80% of freight in transit owing to the port’s capacity of 15mt of bulk and 10mt of dry cargo. In 2007, the government launched the construction of the new port of Alat (Baku International Sea Trade Port), 80km south of Baku, to host all freight activities and decongest the port of Baku. Port construction is to be done in three phases, with the first having been completed in 2018 when the port was opened for traffic with an annual capacity of 15mt (million tonnes) and 100,000 TEUs (Twenty-foot Equivalent Units) in containers. At the completion of the second phase, cargo handling capacity is expected to reach 25mt of general cargo, including 500,000 TEU in containers, though a precise date has not been communicated so far. Both ports are well connected to the country’s railway network, allowing for easy multimodal connections (CAREC, 2021[1]).

On the eastern side of the Sea, the development of the Kazakh ports of Aktau and Kuryk has followed a similar dynamic. Kazakhstan’s main Caspian Sea port of Aktau, with an annual throughput capacity of 15mt, has been complemented by the port of Kuryk, which started ferry operations in 2018. The latter was conceived to handle bulk commodities with the addition of new dry cargo carriers, and improve multimodal connections in Kazakhstan, although its multi-modal marine terminal (MMT), with a transhipment capacity of 10mt, will only be completed by 2030 (Kuryk, 2023[2]). By early 2023, both ports had a combined annual throughput capacity of 21mt and are part of the government’s new plans to transform the Middle Corridor into one of the country’s major trade routes (Adilet, 2019[3]; OECD, forthcoming[4]).

Table 4.1. Comparison of capacity of main Caspian, Black Sea, and European ports (2021)

|

Region |

Country |

Port |

Capacity (mt/year) |

Throughput (mt/year) |

Container capacity (thousand TEU/ year) |

Container throughput (thousand TEU/year) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Caspian Sea |

Kazakhstan |

Aktau |

15 |

3.2 |

25 |

14.3 |

|

Kuryk |

6 |

2.4 |

100 |

0 |

||

|

Turkmenistan |

Turkmenbashi |

17 |

8.3 |

400 |

19 |

|

|

Iran |

Bandar - Anzali |

7 |

1 |

40 |

3.3 |

|

|

Azerbaijan |

Baku - Alat |

15 |

4.6 |

500 |

35.1 |

|

|

Russia |

Astrakhan |

12.1 |

2.2 |

10 |

2.6 |

|

|

Black Sea |

Georgia |

Poti |

63 |

6.3 |

550 |

510 |

|

Batumi |

20 |

2.9 |

200 |

116.1 |

||

|

Türkiye |

Ambarli (Istanbul) |

205 |

108 |

16,000 |

8,500 |

|

|

Romania |

Constanta |

100 |

66 |

1,800 |

666 |

|

|

Bulgaria |

Varna |

15 |

9.5 |

300 |

139 |

|

|

Ukraine |

Odessa |

50 |

21.7 |

1,400 |

650 |

|

|

Russia |

Novorossiysk |

200 |

154 |

1,600 |

755 |

Georgia’s Black Sea ports serve as a gateway for trade between the South Caucasus and Europe, connecting to the Mediterranean Sea through the Bosporus. The Poti Sea Port is the largest port in Georgia, with an annual capacity of 550,000 TEU, handling freight transit traffic between the South Caucasus and the European ports of Constanta in Romania and Varna in Bulgaria, as well as a connection to the Mediterranean Sea. While the port is also well connected to the country’s rail network, its capacity is limited due to depth limitations (it cannot handle container vessels larger than to 1,500 TEUs) and frequent closures due to bad weather. The government therefore launched in 2016 a public–private partnership (PPP) scheme to build a deep-water port and a special economic zone at Anaklia about 35 km north of Poti, but due to a lack of funding the project was cancelled in 2020 (CAREC, 2021[6]). In 2020, the operating company of the port of Poti, APM Terminals Poti, announced its plan to expand the port by creating a deep-water port in two successive phases. The first phase is currently under construction and is to be completed in the coming years, allowing for an increase in capacity of about 150,000 TEUs, and a berth able to accommodate container vessels of up to 9,000 TEU (APM terminals, 2023[8]). The second phase, mainly about infrastructure development, is expected to double annual container capacity to about 1m TEU.

Rail networks have been expanded and modernised along the route

In the 1990s, state-owned enterprises (SOEs) were created to manage and operate railway networks and successive partial liberalisation measures increased private sector participation in Kazakhstan, Azerbaijan, and Georgia. After the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, Kazakhstan, Azerbaijan, and Georgia established, respectively, Kazakhstan Temir Zholy (KTZ), Azerbaijan Railways (ADY), and Georgian Railway (GR) – national railway companies to manage and maintain each national rail network. Faced with rolling stock fleet issues linked to underinvestment, age, and insufficient fleet numbers, governments took steps to partially liberalise railway service provision and increase efficiency. For instance, the private sector was permitted to own and supply wagons in Kazakhstan in the early 2000s, and by 2013 the number of privately-owned freight wagons exceeded KTZ-owned wagons. In Georgia a similar reform was implemented in 2015 (CAREC, 2021[6]; CAREC, 2021[5]; CAREC, 2021[1]). In January 2021, Kazakhstan’s opened rail freight transport to private companies, although some companies report that KTZ effectively retains a monopoly over freight transport (see Chapter 2).

Kazakhstan’s railway network was historically built along the North-South direction, but efforts in the early 2000s have completed the network on the East-West segment. Kazakhstan’s railway network was born in the late 19th century to connect the country’s vast territory and transport its raw materials over large distances, and the centrally planned model of the Soviet economy in the 20th-century led to an orientation of the network towards Russia. Between 2001 and 2016, the government undertook a major development programme, adding 2,500km to the East-West section of the network, allowing for better connections to China, other Central Asian countries, and the South Caucasus. This programme also encompassed the renewal of 4,700km of railway tracks, representing about 25% of the network’s length (Table 4.2), and an asset modernisation programme with the upgrade of 1,000 locomotives and 37,500 freight wagons. As a result, just over a quarter of the network is electrified and has double track lines, reducing capacity bottlenecks. However, businesses interviewed by the OECD reported that bottlenecks remain and are exacerbated during traffic peaks, preventing the transport of additional freight, and further reducing speeds (CAREC, 2021[5]). Moreover, at least 70% of the locomotive fleet is outdated in Kazakhstan, though interviewees report that the uncertainty surrounding access to the freight network constrains their renewal - especially for private rail freight.

Table 4.2. Road and rail networks in the countries of the Middle Corridor (2021)

|

Kazakhstan |

Azerbaijan |

Georgia |

Türkiye |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Road |

Network (km) |

96,167 |

24,981 |

21,110 |

426,906 |

|

Density (m/km²) |

35.4 |

288.5 |

302.9 |

544.8 |

|

|

Freight (mt) |

231.8* |

112.5 |

>300 |

||

|

Rail |

Network (km) |

16 500 |

2 140 |

1 363 |

12 532 |

|

Density (m/km²) |

6.1 |

24.7 |

19.6 |

16.0 |

|

|

Freight (mt) |

410.3 |

15.1 |

12.1 |

38.2 |

|

Note: *Due to a change in the methodology of the calculation of road freight volume by the Kazakhstan Bureau of National Statistics in January 2023, the corresponding number for 2021 was estimated.

Source: OECD analysis based on data from national statistical agencies.

The South Caucasus railway network has been developed to link the Caspian Sea to Türkiye, and recent reforms have modernised and expanded the network, greatly increasing freight traffic capacity. In the second half of the 19th century, Azerbaijan and Georgia’s railway networks were developed East-West as part of the Russian Empire’s Trans Caucasus Railway, to allow for the easy transport of oil from the Caspian Sea (Baku) to the Black Sea (Poti), before being completed by a North-South segment linking Russia to Iran. OECD interviews indicated that reforms over the past decade targeted rail track development, especially electrification and upgrade of the rail network to double tracks, resulting in a solid segment for heavy freight traffic on the Middle Corridor. For instance, 60% of Azerbaijan’s 4,285km network is electrified and 38% is doubletracked, including the Azerbaijan-Georgia East-West segment; freight traffic represented 70% of the networks’ utilisation in 2019. Georgia’s railway network was already electrified in 1967 and is mainly oriented towards freight traffic, with twice as many stations for goods (100) as for passengers (51) along its 1,443km network. Nearly 20% of the network’s main East-West line is doubletracked and uses automatic block signalling allowing to increase traffic capacity (CAREC, 2021[1]; CAREC, 2021[6]).

Azerbaijan and Georgia have comprehensively refurbished railway infrastructure and rolling stock. In 2014, Azerbaijan started renewing its rolling stock, with particular attention to the development of freight traffic. It has purchased 40 new freight locomotives, refurbished and upgraded older ones, and leased new engines under a partnership contract with Kazakhstan. It had also renewed most of its 4193 freight wagons (including 3101 new ones) by 2021. Until 2015, the rolling stock in Georgia suffered from underinvestment and old age, with more than half of freight wagons older than 35–45 years and a significant portion of the fleet close to the end of its normal economic life. The rolling stock fleet decreased by 30% in the preceding decade before the government launched a comprehensive program to refurbish its rolling stock, investing in fleet modernisation and encouraging the private sector to expand its role in rolling stock provision. By the end of 2018, just over half of freight transport used Georgia railway company’s 5001 freight wagons, with the rest carried by other railways and private companies (World Bank, 2020[9]; CAREC, 2021[1]; CAREC, 2021[6]).

In 2017, Georgia, Azerbaijan, and Türkiye completed the construction of a direct rail connection allowing freight to avoid crossing the Black Sea. The construction of the Baku–Tbilisi– Kars (BTK) Railway provides a direct rail connection between Azerbaijan and southern Türkiye via Georgia. It is the shortest rail link between Europe and Asia and connects freight transport from the Caspian Sea to international markets via the Turkish Mediterranean Sea port of Mersin. The network uses the existing rail link between Baku and Tbilisi, connects with the Turkish railway network at Kars, and contains a transhipment terminal in Georgia (Akhalkalaki) to allow containers to change platform wagons between the broad gauge used in Central Asia and the South Caucasus and the standard gauge used in Türkiye. Since the opening of Istanbul’s Marmaray Tunnel to freight trains in 2019, BTK allows for uninterrupted freight train traffic between Europe and the Caspian Sea by-passing Bosporus and Black Sea ferries, - though firms interviewed by the OECD do indicate that bottlenecks at the Akhalkalaki Intermodal Station exist (CAREC, 2021[1]; CAREC, 2021[6]).

Box 4.1. Connecting the Black and the Mediterranean Seas: Istanbul’s Marmaray Tunnel

Connecting Europe and Asia’s rail networks

The Marmaray Tunnel (also referred to as the Marmaray Tube Crossing or Bosporus Rail Tube Crossing) is a 13.6-kilometre-long railway tunnel, of which 1.4 kilometres is submerged under the Bosporus Strait. It is among the largest immersed tunnels in the world and is the deepest, at 60 metres below the sea level.

The first phase of the Marmaray Project, which started in 2004, was completed in 2008 and was inaugurated in 2013, involved construction of the immersed tunnel by the Turkish-Japanese consortium led by Taisei Corporation. With the completion of this first phase, uninterrupted standard gauge railway connection between Europe and Asia has been maintained. Marmaray was financed by Japanese Official Development Assistance (ODA) loans through Japanese Bank of International Co-operation (JBIC) and soft loans from the European Investment Bank (EIB) and the estimated cost stands at USD 4.5 billion.

A new tunnel serving both local commuter and inter-continental freight services

With the primary focus on easing commuter congestion, Marmaray improved the connectivity of the public transport network of Istanbul by integrating metro line to metrobus, tram and ferry lines. The commuter line is further connected to the High-Speed Train that operates between Ankara-Istanbul as well as mainline, regional and international trains. According to the Ministry of Transport, 1 billion passengers have used Marmaray since its inception in 2013. Albeit limited to 00:00-05:00 am, the timeframe out of passenger commute, Marmaray also has a freight transport capacity of 21 pairs of trains per day although an average of 2-4 freight trains are reported to be using it daily. The first commercial train to use Marmaray was a container carrying magnesite from Cukurhisar (Eskisehir) to Austria in October 2019. This was followed by the highly publicised Chinese freight train from Xi’an to Prague that used both the Baku-Tiflis-Kars line and Marmaray, eventually completing its journey in 12 days. In 2022, 402 thousand tonnes of freight were transported through 1018 trips via the Marmaray Tunnel. Improving freight capacity of Marmaray would increase the volume of uninterrupted freight transport from West (London) to East (Beijing), further reinforcing the significance of the ‘’Middle Corridor’’.

Eventually, rail traffic through the Bosporus strait will be transferred to the future high-speed rail running on the newly built Yavuz Sultan Selim bridge. This new rail link will ease congestion on the Marmaray tunnel and will allow for daytime crossings.

Türkiye aims to increase the share of railways in freight transport to 22% by 2053. Türkiye has gradually shifted the bulk of investment in transport to railway infrastructure (the announced target for 2023 is 63% of investment). The country currently has a total of 13 896 km of railway network, including 11 668 km conventional, 2009 km high-speed and 219 km rapid railway lines. Some 49% of the lines are signalled and 51% are currently electrified, with an important increase planned in the coming years (UNECE, 2023[12]). In 2013, a new rail liberalisation law entered into force allowing private companies to construct new infrastructure and run trains on public tracks apart from TCDD (Turkish State Railway Authority). TCCD, as the main provider of infrastructure and equipment, also rents rolling stock to private sector companies. According to private sector interviewed by OECD, still much needs to be done to renew the locomotives and rolling stock. As of 2022, 21% of locomotives and 10% of freight wagons were over 40 years old. Private sector operators also request financial support to increase their share of rolling stock. Currently 41 private firms carry freight through owned wagons, accounting for 33.6% of total rail freight transport (TCDD Taşımacılık, 2022[10]).

For transport operations on the BTK line and the Middle Corridor, seasonal difficulties appear between Kars and Akhalkalaki during heavy winter conditions. The Akhalkalaki transfer station is being upgraded to meet rising demands for conventional and bulk cargo. Transport operations to Europe are performed via the Kapıkule-Svilengrad crossing on the border with Bulgaria and via the Uzunköprü-Pityon crossing on the border with Greece. The double-track Ispartakule-Cerkezkoy section, part of the electrified Halkalı-Kapikule railway line (3rd phase of construction as July 2023) is co-financed by European Union (EU) Instrument for Pre-accession Assistance (IPA) funds. Türkiye currently aims to increase the railway connections to ports and manufacturing sites; 21 ports and piers are connected to railways in the country, including Mersin, Izmir and Iskenderun ports while 13 organised industrial zones have direct access to railways. Increasing the number of logistical centres is also among the targets of the ambitious plans for infrastructure investments in the rail sector. (TCDD Taşımacılık, 2022[10]), (Ministry of Transport and Infrastructure, 2022[13]), (AA, 2023[14]).

Box 4.2. Modal shares for transport in the Middle Corridor countries

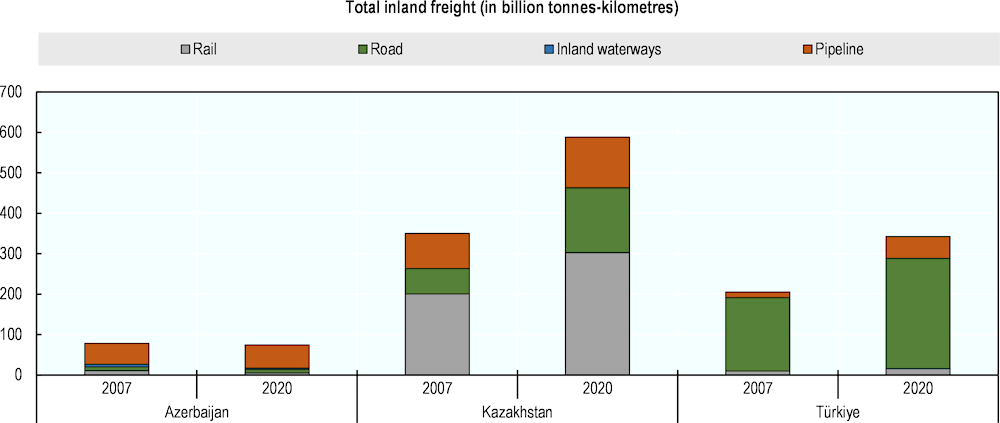

Central Asia and the South Caucasus have seen a rapid development of international road transport, though the former, in particular, remains below its potential. Tenfold more trucks cross Central Asian borders now than in the early 2000s where this number stood at 10 to 30 trucks a day per border crossing point, though the relative share of international road transport is still limited (OECD-ITF, 2019[15]). Historically, rail freight has served international demand and flows are high along the main economic corridors.

Kazakhstan accounts for over 80% of all rail freight activity in Central Asia, equalling to 200bn tonne-kilometres per year. The country’s strategic location on the East-West corridor mainly accounts for this situation, as most of freight to other Central Asian countries transits through its territory.

In Azerbaijan, road transport represents the main mode of freight transport, totalling about two thirds in 2018, and even reaching 88% of goods transported if oil and gas pipelines are excluded. Road freight transport even increased its share between 2014 and 2019 by 17%, while transport via rail and sea decreased over the same period to reach respectively 8.6% and 3.4% in 2018 (OECD-ITF, 2020[16]).

A similar trend can be observed for Georgia, where rail freight traffic declined since the early 1990s to the benefit of road transport. In 2018, almost half of the country’s exports were transported by road, compared to 3.6% by rail. Despite a decline in the total share of freight transport, rail freight containerisation rates almost doubled between 2014 and 2018 to reach 9.5%, reflecting improvements following recent reforms to address major bottlenecks on the network (CAREC, 2021[6]).

Figure 4.1. Decomposition of transport and shipping modes in Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, and Türkiye

Road networks have been expanded in the South Caucasus and Türkiye but remain problematic in Central Asia

Since the early 2000s, Azerbaijan and Georgia have been modernising their road networks with a focus on the East-West highway corridor. In both countries, roads play only a secondary role in freight transport, but the East–West highway linking the Caspian and Black Sea remains the most important regional corridor for international trade and has been a priority for public investment and loans from international financial institutions (IFIs). It runs over 500km in Azerbaijan and 400km in Georgia and is complemented in both countries by a North-South highway running from the Russian Federation to Iran. Azerbaijan and Georgia undertook large road asset renewal programmes in the mid-2000s, as roads and highways were in poor condition due to inadequate funding and vehicle axle overloading, which resulted in high transport costs and long delivery times (ADB, 2014[18]; ADB, 2017[19]). In Azerbaijan, a 2006 assessment revealed that approximately 70% of the country’s road infrastructure required urgent maintenance, but most roads and highways, and especially the country’s section of the East-West highway, had been rehabilitated by 2010 (CAREC, 2010[20]; ADB, 2017[19]). These upgrades have been matched by similar efforts on the Georgian side, which targeted the development of international trade corridors as part of the TRACECA and CAREC initiatives (ADB, 2014[18]). In particular, the East-West highway benefits from a 10-year development plan, with different phases financed by IFIs. OECD interviews indicated that out of the 430km of highway scheduled to be upgraded to four lanes, 230km have already been completed and further 180km are under construction, and work is expected to be completed by the end of 2023. However, some businesses indicated their concerns that the newly constructed sections of the East-West highway do not support the transport of heavy loads.

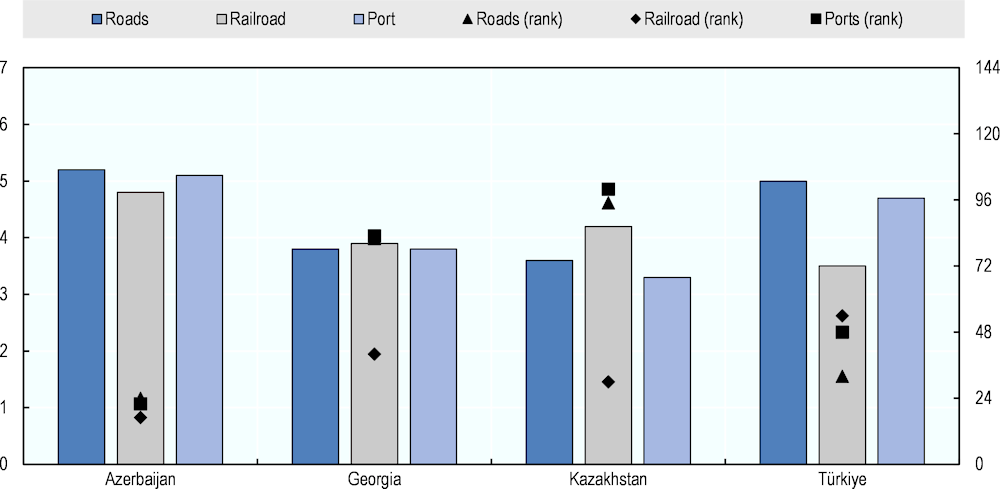

Figure 4.2. Road, rail, and port infrastructure quality in Central Asia, the South Caucasus, and Türkiye

Note: Quality of infrastructure is assessed on a scale from 1 (low) to 7 (high) for the year 2019. Ranks are given out of 144 countries. For Azerbaijan, WEF data for railroad infrastructure quality and ranking is only available for 2018.

Source: (World Economic Forum, 2020[21]).

While Türkiye continues to make significant investments in its road network, the country plans to reduce the share of roads in freight transport from 72% to 57% by 2053. Türkiye lying at the centre of three continents, serves as the intersection of numerous transport arteries. The length of the international road corridors through Türkiye is about 13,000 km. The country's entire length of dual carriageway as of 2022 was 28 816 km, of which 3633 km were highways. In order to provide comprehensive logistics services, roads are built with a view to provide connection to ports and border gates by the authorities. Türkiye has traditionally invested heavily in road transport; a total of $112.4 billion over the past 20 years. Road transport has been one of the top priority modes of transport both in freight and passenger transport in the country accounting for 88.3% in total inland freight. Over the next five years (2024-2029), Türkiye plans to invest $16 billion in road transport to improve regional connectivity. At the same time, the Ministry of Transport operated a shift towards increasing the share of investment on railways in the last decade (Box 4.3). Türkiye`s main target has been to enable and improve uninterrupted transit traffic through the country leading to much of the investment devoted to this end. Three bridges on Bosporus Strait connect Asia to Europe since 2016. Yavuz Sultan Bridge, inaugurated in August 2016, allows vehicles to pass through Istanbul without being subject to city traffic and more importantly without restrictions on drivers as opposed to other two bridges on the Bosporus. The 1915 Çanakkale Bridge, opened on March 18, 2022, connects the two continents by road from the south of the country.

Despite improvements in recent years, the low quality of roads across Central Asia remains a major impediment to the region’s freight connectivity. Road infrastructure development projects across the region have been carried out in recent years with substantial support in the context of framework initiatives such as CAREC and TRACECA. However, businesses reported to the OECD that on average the quality of road infrastructure remains low as a result of an inadequate investment environment, leading to high transport costs, and reducing the countries’ attractiveness for international freight transport. For instance, without taking into account rising traffic stemming from the development of the Middle Corridor, meeting increased freight and maintaining the current level of network performance by 2030 is estimated to require road capacity increases varying from 84% In Mongolia to almost 500% in Uzbekistan, while Kazakhstan stands in a middle position, with a needed rise of 151% (OECD-ITF, 2019[15]). Kazakhstan has initiated an ambitious programme of investments for its domestic road network, which comprises six international transit routes with a total length of about 8250km aimed at improving the connectivity and quality of road transport both across the country and with regional neighbours. It further aims to repair over 11 000km of roads by the end of 2023 (International Trade Administration, 2022[22]).

However, infrastructure bottlenecks lead to congestion, especially at border points and ports, and reduce the route’s attractiveness

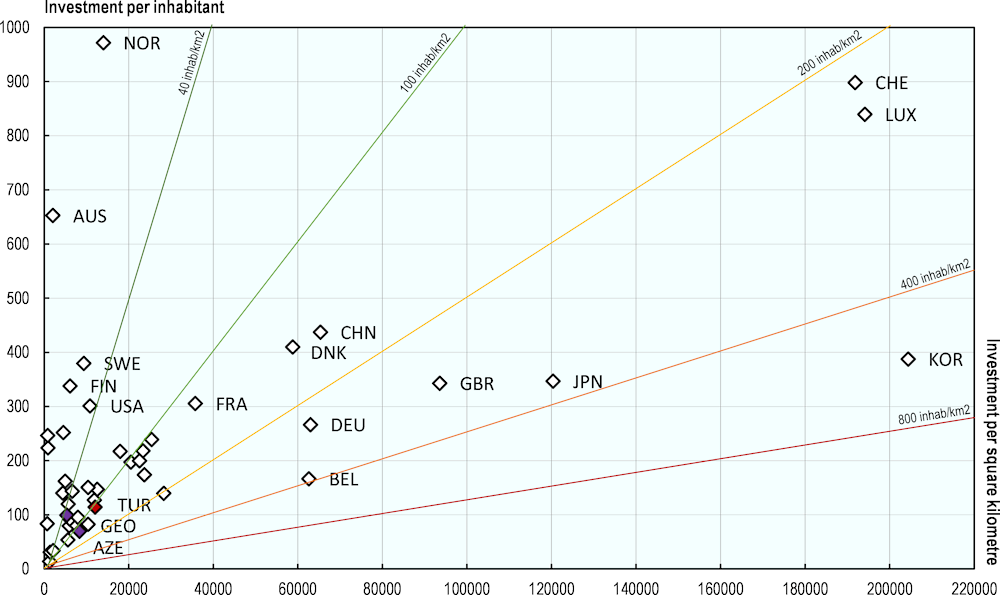

Despite increased investment in transport infrastructure, Middle Corridor economies’ investments remain low in absolute terms

Figure 4.3. Total inland transport infrastructure investment (2015-2019 annual average, in EUR)

Note: Countries with a low density and an unequal distribution of population, such as Russia or Canada, have very low figures for their investment per square kilometre, due to much of their territory being uninhabited. Thus, it is not always representative of a weak effort in transport infrastructure investment. Data not available for Kazakhstan.

Source: OECD calculations based on ITF database

The current level of transport infrastructure investment remains below projected needs. The region’s annual financing need in early 2020 was estimated at 7.8% GDP or USD 1.7tn for Central Asia and the South Caucasus over 2016-30. Investments in inland transport infrastructure in the countries of the corridor are substantial relative to GDP. However, commitments amounted to USD14-19bn per year from 2006 to 2011 and have been on a declining trend since (ADBI, 2021[23]) (University of Central Asia, 2023[24]). Investment per capita and per square kilometre remain insufficient in absolute terms to address the infrastructure gap (Figure 4.3). While these data predate Russia’s war in Ukraine and renewed commitments to improving regional connectivity, more recent assessments also point to a persisting financing gap (EBRD, 2023[25]). For instance, for Kazakhstan the investment gap amounts to 1.11 % of GDP across all sectors if the country’s infrastructure needs are to increase in line with its expanding economy and growing population – not mention the need to develop new infrastructure. The gap is most prevalent in cross-border infrastructure, energy, and road transport, with 75% of existing transport infrastructure requiring replacement or rehabilitation, necessitating infrastructure investments amounting to 3.9% of GDP until 2040 (OECD-ITF, 2019[15]).

Box 4.3. Investment in transport infrastructure in Türkiye

Inland connections are relatively underdeveloped in Türkiye due the hilly landscape and poor infrastructure in remote areas. Despite sufficient capacity of terminal facilities for loading and unloading containers, port infrastructure of Türkiye still suffers from poor connections to high-quality roads and railways. In order to overcome these physical obstacles and to increase the accessibility of landlocked Anatolian manufacturers to European markets with low transport costs and high traceability, Türkiye launched several transport and logistics projects devoting large funds.

The Ministry of Transport and Infrastructure expects to increase the share of rail freight to 22% by 2053 reflecting this vision. Share of road infrastructure in public investment plans declined from 72% in 1999 to 35% in 2019, while railway spending increased its share from 7% to 37% in the same period. In 2023, government devoted highest share (27%) to transport and communications sector in the budget, with a 145% rise compared to 2022. The flagship projects in the investment program include the Ankara-Sivas High-speed train project, part of the Middle Corridor as an access to Europe from the Tbilisi-Kars railway. Türkiye also plans the establishment of 26 logistical centres. The target is linking up all industrial zones in the country to ports through railway.

The EU and some development partners also take part in financing some major railway projects. The double-track Ispartakule-Cerkezkoy section, part of the electrified Halkalı-Kapikule railway line, is co-financed by the European Union (EU) Instrument for Pre-accession Assistance (IPA) funds. The line is part of the EU Trans-European Transport Network (TEN-T). The European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) has extended a €150 million loan to the Turkish government for co-financing the construction of a 67 km section of the high-speed railway line from Istanbul to the Bulgarian border. The loan will further support Türkiye’s transition to a low-carbon economy.

On the other hand, in the last decade, the share of public investments made for air and maritime transport decreased, owing to the liberalisation and privatisation trends in these sub-sectors. As a result of the transfer of the operating rights of a very large part of the ports belonging to the private sector and application of Build-Operate-Transfer method for the construction of some airports, public investment in the maritime and air transport sectors have declined over time.

In April 2022, the Turkish government unveiled its 30-Year Transport and Logistics Master Plan, aimed at enhancing logistics infrastructure across various modes of transportation. As part of this initiative, Türkiye aims to allocate USD 153 billion by 2053 to facilitate substantial improvements in its infrastructure and become an international logistics hub.

Container and Caspian Sea vessel fleet capacity is not in line with current and projected needs and leads to congestion issues

Governments and businesses surveyed by the OECD indicated that increased traffic on the Middle Corridor has exacerbated pre-existing bottlenecks, such as a shortage of port capacity, containers, and vessels in the Caspian Sea. For instance, Poti was one of the 20 ports in the world were the average arrival times increased the most between 2021 and 2022 (World Bank, 2022[27]). Interviewees indicated that addressing these bottlenecks should be a priority for infrastructure updates and development, as the corridor’s reliability and ultimately its attractiveness relies on the ability of each segment to provide the level of service expected by users.

Despite capacity increases in Azerbaijan’s and Kazakhstan’s Caspian ports in recent years, they remain below the capacities needed to handle increased traffic. Current throughput capacity of Kazakhstan’s main Caspian Sea port of Aktau is estimated at 15mt (rising to 21mt when combined with the nearby port of Kuryk), slightly above Azerbaijan’s freight port Alat annual capacity of 15mt and 100,000 TEUs (Table 4.1) (CAREC, 2021[5]; CAREC, 2021[1]). However, current capacities of the Middle Corridor’s main seaports of Aktau, Kuryk, Baku-Alat are estimated to be able to absorb only up to 6mt of cargo, including up to 4mt of bulk cargo and up to 100 thousand TEU, from the traffic of the Northern Corridor. (USAID, 2022[28]). This can be explained by the lack of modern transhipment and freight handling equipment in ports, which leads to congestion despite low utilisation rates (see below). In addition, because of depth limitations, ports can only accommodate small container feeder vessels, resulting in high shipping rates and limited service frequencies (CAREC, 2021[6]). Finally, businesses indicated that the imbalance of port capacity between both shores of the Caspian Sea, with Baku-Alat being the only operational port on the Western bank, leads to congestion there too.

Businesses report that the Caspian Sea crossing is a major bottleneck, as ferry vessels and services are insufficient to balance throughput capacity on either side. Though ferry and vessel limitations on the Caspian Sea are not a new issue, they have been dramatically exacerbated by the increase in traffic observed in 2022. Businesses report insufficient ferry fleet capacity and unpredictable schedules, contributing to long loading and crossing times and port congestion, as the loading and unloading of vessels can take up to 24 hours on either end (World Bank, 2020[9]). Indeed, there are only two companies operating routes across the Caspian Sea: Azerbaijan Caspian Shipping Company (ASCO) and KazMorTransFlot (KMTF). ASCO connects the port of Alat to Aktau, Kuryk and Turkmenbashi through rail ferry and RoRo services with a fleet composed of thirteen ferries, 25 years old on average, and two RoRo vessels, 36 years old on average (UIC and Roland Berger, 2021[29]; CAREC, 2021[1]; CAREC, 2021[5]). KMTF is specialised in oil transport but diversified its activity with a sub-fleet of three container ships and 2 dry cargo ships operating between Aktau, Kuryk and Alat. Businesses reported that the fleet was not able to cover their needs following increased traffic since early 2022, the more so that the ferry services do not have a fixed schedule. The frequency of services between Azerbaijan and Kazakhstan is reported to vary depending on weather conditions and demand, as vessels generally wait until fully loaded before departing, which averaged between three and five days before 2022, while the crossing itself takes about 1.5 days (World Bank, 2020[9]; UIC and Roland Berger, 2021[29]; PMCG, 2023[30]). Firms report that waiting times stayed the same and even increased in some instances due to increased traffic, while ASCO’s near-monopoly situation also contributed to relatively high prices, further reducing the competitiveness of the crossing.

Interviews and surveys also highlighted that these issues are further exacerbated by container shortages. Respondents report shortages of both containers and container rail platforms. The lack of containers in the region can be explained by the imbalance between Westbound and Eastbound freight flows, and the low coverage of major shipping companies in terms of offices and container terminals. Consequently, shipping companies lend the containers to clients at ports (Poti for instance), but demand their return within 10-14 days, when containers shipped to Central Asia from Georgia take 25-35 days to return, exposing the client to important delay penalties. As an alternative option, clients are allowed to buy their own containers, which represents an additional cost. Regarding container rail platforms, companies indicated that they tend to get stuck at Akhalkalaki, the rail gauge change terminal at the Georgia-Türkiye border.

Finally, businesses reported that while rail fleets are less problematic, inefficiencies in wagon fleet management are nevertheless creating additional constraints. Businesses reported in OECD interviews and surveys that the shortage of locomotives and wagons, a long-standing issue especially in Azerbaijan and Georgia, has added to border point congestion since early 2022. Kazakhstan faced a similar issue a few years ago on the Kazakh-Chinese border, but seems to have been able to address most of the gaps since, notably by allowing private ownership of freight wagons to attract private investment to the sector (OECD-ITF, 2019[15]). The Kazakh railway company NC KTZ has even been able to provide Azerbaijan with about 200 assembly platforms as wagon loading assistance (German Economic Team, 2022[31]). Governments also indicated that part of the issue arises from inefficiencies in the management of wagon fleets due to an absence of real-time tracking and online information about the rolling stock.

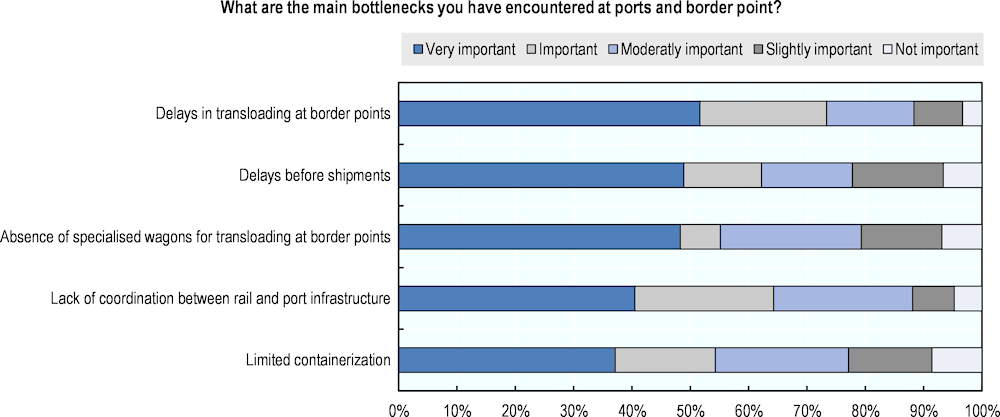

Deficient multimodality, lack of equipment and limited automation of ports lead to important congestion despite low utilisation rates

OECD surveys and interviews indicate that the Middle Corridor’s existing infrastructure capacity is overall in line with traffic flows, though the route’s main infrastructure components need more efficient interconnection to improve travel time predictability. Interviewees indicated that while the reliability of all transport modes along the route increased in recent years, the surge of traffic on the Middle Corridor following Russia’s war in Ukraine has translated into bottlenecks at port and border crossing points. In particular, the lack of multimodal rail-road and rail-port infrastructure at these key junctures has been singled out as the most pressing infrastructure issues.

Figure 4.4. Assessment of multimodality-related bottlenecks in the survey

Source: OECD Middle Corridor survey

Lacking interfaces between land transport and ferry crossings in Caspian Sea ports are reported to be a major obstacle to predictable travel times. Businesses surveyed and interviewed by the OECD indicated that the lack of intermodal facilities to connect the Caspian maritime route with Azerbaijan and Kazakhstan’s railways and roads is creating major bottlenecks for freight traffic. For instance, discharge and waiting times have been reported to amount to up to ten days both at Kazakhstan’s Aktau and Azerbaijan’s Alat ports, while an ideal port processing time should be two hours between the moment containers arrive by train to the moment they are loaded onto the ship (World Bank, 2020[9]; ADB, 2021[7]).

Caspian Sea port congestion mainly follows from insufficient or ageing loading equipment. East-West inland container traffic along the Middle Corridor is carried either on trucks or on railway flatbeds before reaching the ports of the Caspian Sea. Once containers reached the ports, two transhipment methods exist: roll-on/roll-off (RoRo) and lift-on/lift-off (LoLo). RoRo requires specifically built ships with an integrated truck ramp or an integrated rail path to directly access the ship cargo loading platform. LoLo involves vertical loading, requiring either on-board cranes in ships or large cranes at the ports’ docking stations. Despite the recent expansion of the RoRo vessel fleet in the Caspian Sea (see next section), transhipment equipment is reported to be lacking, though Alat port built a connection to the railway network and a rail terminal within the port (ADB, 2021[7]). Even if less pressing, similar issues have also been reported for the rail terminal of the Georgian Black Sea port of Poti (PMCG, 2023[30]).

Businesses report that the lack of modern container equipment and terminals at the ports of Kuryk/Aktau and Baku/Alat slow down traffic and increase transit costs and time. Rapid, secure, and sustainable container traffic along the Middle Corridor routes requires robust container handling infrastructure in each segment to ensure swift unloading, sorting, and reloading. However, in OECD surveys and interviews, businesses indicated that the lack of modern container infrastructure represented a major bottleneck at ports on both sides of the Caspian Sea. For instance, while container loading and unloading time in international ports such North Europe’s Hanseatic ports takes on average five minutes per container thanks to the use of automated multimodal cranes or container terminals, in interviews conducted by the OECD, businesses indicated durations between 30-60 minutes for the same operations in the ports of Azerbaijan and Kazakhstan. Similarly, the feasibility study for the automation project of the port of Baku estimated that the additional costs incurred because of outdated infrastructure equipment amount to a total of about USD 5m per year, including USD 3m in ship waiting costs, USD 1.1m in truck waiting costs, and USD 0.4m in round-trip unloading costs (KSP, 2020[32]).

In particular, firms report a low transhipment productivity of Azerbaijan’s port of Alat due to a lack of dedicated container equipment and terminal, and outdated infrastructure in Kazakhstan’s ports. Interviewees indicated that because of the multi-purpose nature of the port of Alat, its equipment is intended for bulk operations rather than container operations, with containers handled at general cargo berths, without adapted infrastructure such as ship-to-shore cranes, reach stackers, and gantry cranes. As a result, the handling of containers lacks standardisation and results in additional delays, which is also confirmed by recent studies of the matter (World Bank, 2020[9]; KSP, 2020[32]). In Kazakhstan, businesses indicated that the loading equipment in the port of Aktau is outdated and lacks sufficient large cranes to meet modern standards, while the new port of Kuryk lacks the necessary loading equipment and is constrained to servicing only rail cargo from foreign ferries, though it can service both hinterland rail and automobile (USAID, 2022[28]; OECD, forthcoming[4]; ADB, 2021[7]). Interlocutors during an OECD field visit to the port of Aktau also pointed to Kazakhstan’s relative inexperience in dealing with containerised freight as a challenge. Firms have suggested to develop intermodal platforms allowing for container loading and unloading as well as storing containers waiting to be transhipped (currently lacking), as well as to improve empty container management. Taken together, these bottlenecks reduce the speed of cargo handling, increase the difficulty of operational planning, raise costs and transport times, and reduce the attractiveness of the Caspian transit corridor.

As a result of deficient equipment, utilisation rates of Kazakh ports are low despite congestion. On the eastern shore of the Sea, the lack of intermodal infrastructure and vessels of Kazakhstan’s ports of Aktau and Kuryk have translated in an acute transit capacity limitation, where both ports cannot meet rising railway freight trade originating from China (Rail Freight, 2022[33]). This issue seems to follow from a wider trend within the Caspian Sea, where port utilisation rates are systematically below capacity, in part due to higher costs of connectivity, and where actual capacity is below potential due to widespread underinvestment in infrastructure expansion and renewal. For instance, in 2021, the average capacity utilisation of Kazakhstan's seaports was just 31% in 2021, dropping to 25% and 20% for dry cargo and ferry terminals; utilisation is likely to have increased in 2022, but it does not meet the needs of increased traffic (Adilet, 2022[34]) (USAID, 2022[28]).

Border crossings and inland transport also suffer from a lack of multimodality

Railway gauges along the Middle Corridor are governed by two different standards, resulting in interoperability issues and increased transit times and costs. The most often cited issue by OECD interviewees referred to the difference in railway gauge standards between the former Soviet states of Central Asia and the South Caucasus, using the broad-gauge of 1520mm, and China, Türkiye, and Western Europe using the standard gauge of 1435mm. As a result, freight trains crossing from China into Kazakhstan and to Türkiye face at least two track interruptions and transloading of containers at border control points (BCPs), either to wagons with the correct gauge size or onto trucks. Both have been reported to be time-consuming and labour-intensive tasks adding to customs and border point infrastructure capacity limitations, especially at the China-Kazakhstan border crossing of Khorgos and the Kazakh Caspian Sea port of Kuryk. Since automatic change-of-gauge technologies are not yet widely used across the region, interviewees reported that trains stop for about five hours at each change of railway gauge – without accounting for the additional queues. Non-perishable and non-hazardous freight is also often transhipped onto trucks at Khorgos and at the borders between Azerbaijan and Georgia, which is complicated by frequent delays due to deficient multimodal infrastructure.

At dry border crossing points, infrastructure to support connectivity between rail and road freight transport is lagging. Businesses state that high border crossing times and congestion mainly result from technical issues created by inadequate infrastructure. For instance, the lack of proper transhipment facilities to handle containers from trucks to rail platforms or vice-versa, or to handle the marshalling of wagons leads to long queueing for both trucks and trains at loading terminals while waiting to be loaded and unloaded. This issue is reported to be particularly stringent at the border points requiring a change of railway gauge, such as between China and Kazakhstan, where containers can wait for up to ten days, as well as at the Turkish border. Even outside these border crossing points, the rotation of wagon fleets across the national railway networks of Kazakhstan, Azerbaijan, Georgia is reported to be suboptimal, lengthy, and costly, mainly due to a lack of block container trains1 (World Bank, 2020[9]).

In Central Asia the issue is reinforced by the poor quality of last-mile connectivity as well as the small and aging truck fleets preventing efficiency improvements via freight bundling. Despite recent reforms, rail-road multimodality lags in Central Asia, resulting in a non-negligible amount of cargo being transported by trucks. For instance, public and private sector representatives reported during OECD interviews that domestic trucks are often overloaded in Kazakhstan, accelerating the deterioration of roads, especially those outside international corridors. Such secondary roads are usually poorly maintained. This accelerates the deterioration of already relatively old truck fleets and increasing fuel consumption up to 50 litres per 100km, as opposed to 20-30 litres in normal operating conditions (OECD-ITF, 2019[15]). As a result, many trucks active in Kazakhstan and in Central Asia are not fully compliant with international standards regarding safety, operational efficiency, and environmental impacts. For instance, in Kazakhstan, interviewees indicated that most trucks are still operating under levels 1 to 4 of European Emission Standards, while in Europe all fleets need to be at least compliant with level 5. The negative impact on environmental performance is further exacerbated by the small size of companies, preventing bundling of cargo transports and impeding fleet upgrades (OECD-ITF, 2019[15]). Overall, the trucking industry’s competitiveness is hampered in Central Asia by important maintenance and fuel costs related to the age of the fleet, and important labour costs due to the small size of companies and lack of freight bundling.

While increased traffic has challenged border infrastructure all along the route, businesses report particular bottlenecks at the Red Bridge border crossing between Azerbaijan and Georgia. Public and private entities alike indicate that despite recent border crossing point infrastructure improvements in Kazakhstan, Azerbaijan, and Georgia, its capacity remains limited, which creates congestion when traffic increases. Among the main capacity limitations cited, the insufficient number of passing lines and the lack of secure customs clearance areas with dedicated inspection facilities are the most frequent. On these matters businesses reported in particular the lack of capacity of the Red Bridge border crossing facility that lacks sufficient border entry points, logistics centres, and custom warehouses to efficiently service increased transit capacity on Azerbaijan’s side of the border. On the Georgian side, the main reported issue relates to the lack of a secure customs area and dedicated control areas, which translate into queues of shipments waiting to be inspected. The absence of co-located Azerbaijani and Georgian inspection facilities as well as of differentiated passing lines by type of cargo or level of risk further adds to this situation, as it prevents a pre-sorting of traffic and processing for all shipments is hold up. However, both governments are aware of the issue, and reform discussions are ongoing to jointly improve infrastructure capacity at the border point (World Bank, 2020[9]).

Recommendations

Develop multimodal infrastructure

Enhance the transhipment of goods at border crossings

Government should develop and improve multimodal facilities at border crossings. Respondents of the survey indicated that inadequate transhipment infrastructure were the cause of important delays. At the borders between Kazakhstan and China, and Georgia and Türkiye, where gauge trains impose transhipment, operators must improve both bogie exchange and transhipment facilities. Containerisation could ease this process as modern cranes can rapidly ship a container from a train to another one.

Efficient multimodal hubs at the borders could also allow the transfer of goods from trucks to trains. Such new terminals located close to the border could integrate custom procedures and ease congestion at the road border crossings. This configuration would be particularly interesting between Azerbaijan and Georgia as an alternative to the congested Red Bridge border crossing. Another compelling aspect of these multimodal terminals at borders is that they can be combined with Special Economic Zones to develop into wide logistic and industrial complexes (CAREC, 2018[35])

Improve the multimodality of ports

Port authorities in Aktau, Kuryk, Alat and Poti should enhance the multimodality of their operations by prioritising the construction of transhipment facilities for containers. This includes container berths, container storage facilities and container cranes. Transferring containers more efficiently between trucks, trains and ships could reduce waiting times at ports. Though RoRo ferries are an efficient way to transfer wagons across the Caspian Sea, only the use of container ships will bring enough additional capacity to meet demand growth. This implies accelerating on the construction of container handling facilities, as planned for instance in the second development phase of the port of Baku-Alat, with five container berths.

Create dry ports and containerisation infrastructure

To enhance multimodality and develop containerisation of freight transport along the corridor, governments should develop inland container handling facilities. These logistic centres, sometimes called “dry ports” include container yards and Container Freight Stations (CFS). While container yards store containers and dispatch them between different transport modes, a CFS combines loose cargo into containers or separates cargo for pickup. This process can occur under the watch of customs authorities and offers shippers a cost-efficient method to employ containerisation for shipping goods to their ultimate destinations (CAREC, 2021[36]). Freight forwarders, shipping lines, and third-party logistics providers typically operate CFS. Demand for CFS could be important as the use of containers rises on the corridor, so governments should seek to attract international CFS operators to develop such infrastructure and share their expertise with local companies through partnerships. A containerisation master plan could be crafted to address legislative, regulatory, and operational issues, and improve the capacities in container handling in the region.

At the national level, advance last-mile connectivity to better connect local growth poles along the route

Efforts should be directed towards bolstering transport networks that connect regional growth centres to the Middle Corridor. Governments can invest in road and rail infrastructure to bridge the last-mile gaps, ensuring smooth movement of goods from production hubs to the trade route (OECD-ITF, 2019[15]). This connectivity enhancement will enable local economies to leverage the corridor's potential for export and import activities. India's "Golden Quadrilateral" project, which aims to connect major cities with modern highways, showcases the impact of enhanced last-mile connectivity. Similar projects in Central Asia and the South Caucasus can connect production hubs to the Middle Corridor efficiently, boosting trade.

Increase vessel fleet capacity and regularity in the Caspian Sea

Kazakhstan and Azerbaijan should endeavour to extend the fleet of cargo ships in the Caspian Sea, with a focus on container ships. Alongside the extension of the existing ferry and RoRo fleets, operators should introduce more container ships. Container ships have a higher capacity than ferry and RoRo ships of equal dimensions and can contribute to significantly increasing the throughput of the link once multimodal infrastructure to handle containers is commissioned at the ports. Indeed, according to one of the respondents, KMTF’s container ships can carry up to 1000 containers, when RoRo ferries can load 40 platforms, implying a load of just 40 containers. This capacity growth should rely on both the Azerbaijani and Kazakh national maritime operators, namely ASCO and KMTF. Kazakhstan’s operator being a smaller player than Azerbaijan’s ASCO, the fleet growth should be even more important for KMTF in order to have a healthy competition between two companies of a similar size and market power.

The route’s competitiveness would gain from the implementation of fixed timetables for ferry operations between the Kazakh ports and Alat. Departures at fixed hours and important frequencies allowed by the growth of the fleet would contribute to shorter waiting times at Aktau and Kuryk.

Develop rail capacity to improve the route’s throughput and sustainability

To ensure the Middle Corridor’s competitiveness, rail companies should increase capacity along the route. Potential bottlenecks must be identified ahead of time to plan infrastructure enhancements such as double tracking on critical sections. Railway companies should aim for the corridor to be entirely electrified, to avoid locomotive changes and to ensure the sustainability of the route, with reduced CO2 emissions compared to road or maritime transport. This would require important investments in Kazakhstan, in particular, in addition to the planned electrification of the Dostyk-Mointy section (CAREC, 2021[5]).

Rail operators should address the insufficient number of locomotives and wagons on the trans-Caucasian section. While all countries along the corridor will have to make important investments to replace aging fleet and keep up with traffic growth, the situation is particularly difficult in Georgia. Therefore, the Georgian government should seek to increase the fleet of locomotives and wagons among Georgian Railways and the other private operators. Countries along the corridor could conduct procurement jointly, leveraging on Kazakhstan’s industrial capacity with the presence of international manufacturers. Railway operators should also use digital monitoring to increase the availability of freight wagon (Box 4.4)

To support the required investments, governments should establish a framework to involve the private sector in the development of the corridor. The use of Public-Private-Partnerships should be increased for railway infrastructure projects. Higher private investment in the rolling stock could be achieved by deepening reforms of the railway sector. The European initiative Shift2Rail (S2R) can represent an example of a region-wide initiative seeking focused research and innovation (R&I) and market-driven solutions to double the capacity of the European rail system and improve its reliability and service quality by 50%.

Planners should bear in mind that enhancing the throughput of rail freight should not be detrimental to local passenger connectivity. For instance, city bypasses can be an efficient way to increase freight capacity and reduce noise and risk of accident without diverting passenger traffic from the city centres. Tbilisi’s halted railway bypass project is an illustration of this challenge. In this case, freight should be diverted outside of the city centre, but passenger trains should remain on the existing right of way to serve local demand and offer an alternative to road traffic.

Box 4.4. Digital freight train monitoring tools: the case of Fret SNCF

In 2017, the French rail network SNCF launched the “Digital Freight Train”, in a partnership with Traxens, a French company developing shipping container tracking solutions. The Digital Freight Train uses an on-board network of interconnected sensors that can deliver multiple remote tracking and monitoring services. These tools are flexible and can depend on the willingness of stakeholders.

The digital train sends useful data to freight stakeholders, increasing the reliability and predictability of shipments. For instance, it is possible to monitor train mileage, precisely determine the train’s geographic placement in real time, and receive alerts when shipments reach strategic locations, such as loading and unloading sites.

It also increases the safety and quality of shipments: sensors allow the monitoring of transport conditions for sensitive cargo, with numerous parameters such as pressure and humidity inside tank wagons. In terms of security, various functions such as the wagon load status recognition or the detection of operating incidents increases rail transport safety. The digital train can also detect abnormal shocks and automates test brakes before transport. Finally, these sensors optimise the necessary maintenance of wagons, since it allows to monitor the mileage, shocks and the wear of the equipment.

Source: (SNCF, 2020[37]; SNCF, 2019[38])

Set up adequate environmental standards and incentives to develop a low-carbon transport offer

The Middle Corridor development provides an opportunity to mainstream sustainable transport infrastructure planning, which can boost the route’s attractiveness significantly. During interviews, public and private stakeholders alike have highlighted the importance of integrating environmental sustainability into the route’s planning and regretted the small scale of reforms and subsidies in that direction so far. Interviewees noted that developing freight transport via rail can bring both efficiency gains and a more climate-friendly transport network, while allowing the route to align with the EU taxonomy and supply chain legislation, creating greener and more sustainable ways of doing business. Network electrification efforts along the corridor can only contribute to the route’s sustainability if the share of rail freight increases considerably and the electricity originates from low-emitting sources. To make the route truly sustainable in environmental terms, planners should move away from coal and develop greener sources of electricity to power the railway electrical grid.

An enabling environment to develop a more sustainable trade and transport network is missing in the countries along the Middle Corridor. More generally, interviewees highlighted that despite heightened attention towards the design of sustainability strategies by both the public and private actors, no comprehensive environmental standard setting strategy has been implemented at national or regional level (Box 4.5). The majority of existing sustainability strategies consider either a modal shift from road to less polluting modes of transport like rail or targets to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. However, sectoral energy efficiency standards, carbon footprint calculators, or subsidies to kickstart greener transport or pilot projects for alternative fuel options in the road transport sector especially are yet to be implemented. Clear sectoral decarbonisation plans for transport including GHG emission reduction targets are also lacking. The absence of robust Measurement, Reporting and Verification (MRV) systems and carbon accounting systems contributes to the low development of environmental planning.

Türkiye and Georgia are largely exposed to the Green Deal agenda and its implications. The 2021 Green Deal Action Plan published by the Ministry of Trade of Türkiye includes priority actions for the government institutions with respect to carbon border adjustment mechanisms (CBAM), circular economy, green finance, clean energy, sustainable agriculture, and smart and sustainable transport systems. The Action Plan sets the basis for future regulatory changes as regards the logistics industry in Türkiye. Adherence to the Green Deal will certainly encourage the already existing trend in the country to switch from road transport to railway, improve inter-modal transport and usage of zero emission vehicles as well electrification and development of alternative fuel capacity in all modes of transport. In the case of Georgia, the context of EU membership aspirations makes transport decarbonation goals even more important to reach.

Complementary reforms to modernise ports and develop environmental plans in the maritime sector can further support this trend. Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, and Georgia have been modernising and expanding their main seaports and have introduced international environmental standards, including ISO certifications on energy usage, environmental impact and waste management. Azerbaijan and Kazakhstan’s Caspian Sea ports also received the EU “green port” certification. Azerbaijan’s port of Baku has developed a “Climate Strategy 2035” accompanied by a concrete Action Plan to mitigate the port’s contributions to climate change and achieve its full decarbonisation by 2035 (WPSP, 2023). Kazakhstan’s port of Aktau has become the first in the country to receive the Ports Environmental Assessment System certification and EcoPorts status from the European Sea Ports Organisation (ESPO) in July 2022, a global standard for environmental management certifying ports working to reduce their negative impact on the environment (OSCE, 2022[39]). Additional expansion projects of the port are to follow the same standards and will benefit from EBRD financing.

Successive modernisation and expansion plans of Georgia’s port of Poti have systematically followed environmental and social impact assessments (ESIA) since 2010 and have been compliant with IFC standards (ADB, 2010[40]). OECD interviews also indicated that the port also aims to attain 75% carbon neutrality by 2030 and reach full carbon neutrality by 2040, while investing in new technologies for handling bulk cargo by minimising negative environmental impact. However, room for improvement exists, as a recent study indicates that the port has been the second most important contributor to air pollution in Georgia, after the port of Batumi, over the period 2010-2018, with emissions from container and general cargo ships amounting to more than 85% of total emissions (Tokuslu, 2021[41]).

Address intensified road freight traffic through targeted incentives to avoid greater negative externalities While an increase in road transport can bring considerable productivity gains in the short term, in the longer run, negative environmental externalities such as local pollution and CO2 emissions are high. For instance, the emission impact of transport in the countries of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), of which the Central Asian and the South Caucasus countries are members, finds that transport-related emissions are set to increase by 150% in the business as usual (BAU) scenario over the next 35 years, well above the targets set by the Paris climate accords. Emissions would still increase by 80% by 2050 compared to 2015 if all countries were to invest in best-in-class transport infrastructure technologies, while a two-degree scenario would require an emission reduction of at least 20% (UNESCAP, 2022[42]). Measures to limit the emissions of the road freight sector and incentivise a shift towards rail transport could include fuel taxes or targeted road pricing. But a more sustainable way to reduce transport emissions would be to adopt a comprehensive policy framework, including coherent interventions across freight-transport modes, with emission reduction target for each transport mode adapted to the local context (ITF, 2022[43]).

Infrastructure planning should include resiliency as part of its sustainability agenda. In addition to climate mitigation strategies, climate adaptation and resilience have gained importance when planning important transport infrastructure. In France for instance, the future Montpellier-Perpignan high-speed rail line is being planned as a response to the current rail line’s vulnerability to climate change and floodings along the Mediterranean coast. Potential climate-related vulnerabilities occurring on the entire life cycle of the infrastructure have been addressed in the planning of the new line. The life cycle approach to infrastructure planning is particularly relevant for the Middle Corridor, with climate change affecting the reliability of transportation in the future, from lower Caspian Sea levels to heat waves. The notion of resilience should also incorporate resistance to geopolitical or social shocks, and market evolutions with evolving energy prices for instance.

Box 4.5. Sustainable transport strategies in Central Asia and the South Caucasus

The infrastructure gap in the region is already substantial and widened by climate change

The region’s investment needs in infrastructure are estimated to reach USD 492bn for the period 2016-2030, while climate change-adjusted estimates1 increase estimated investment needs to USD 565bn (ADB, 2017). Among infrastructure projects planned and under construction in Central Asia and the South Caucasus, transport projects represent 17% of total investment (USD 94bn), and concern mostly road (60%) and railways (32%) (OECD, 2019). Given the transport sector’s major role in greenhouse gas emissions, investments in sustainable transport infrastructure are a priority for the region’s climate commitments.

Numerous investment plans related to sustainable transport infrastructure are planned

In Azerbaijan, sustainable development projects were initiated with the “Azerbaijan 2020 – A Vision of the Future” plan, covering various topics including the modernisation of transport infrastructure. Planned and current transport infrastructure projects account for USD 7.5bn (6% of total infrastructure projects), mostly budgeted on roads and railways development. A major ongoing project is the Railway Sector Development Programme, aiming to rehabilitate the track of the Sumgayit-Yalama rail line – a key link in the North-South Railway Corridor within the CAREC network. Moreover, the construction of a road/rail corridor between Torgundi (Afghanistan) and Istanbul (Türkiye), crossing Turkmenistan, the Caspian Sea and Baku (Azerbaijan), and linking Tbilisi and Georgian ports, will require USD 2bn of investment, divided equally between the five countries involved.

Georgia’s 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development provides for the development of economic corridors through the enhancement of transport and logistics networks. Planned and current transport infrastructure projects amount to USD 16.4bn (45% of total infrastructure projects), with a focus on the East-West highway.

With the Kazakhstan 2030 Development Strategy, the country launched major infrastructure projects to modernise the country’s facilities. The sixth priority of this strategy is the development of transport infrastructure, aiming to improve rail, road, air and water infrastructures. Planned and current projects account for USD 39.9bn (20% of total infrastructure projects). However, rail projects only concern 16% of total transport projects, while the planned “Almaty-Aktogay Rail Electrification” or the “Railway Modernisation Improvement” projects will require USD 2bn, and increase regional connectivity.

1. Climate change-adjusted estimates account for additional infrastructure investment needs to mitigate carbon emissions and to increase resilience to climate change.

Source: (OECD, 2019[44]).

References

[14] AA (2023), Halkalı-Kapıkule Hızlı Tren Projesi’nin üçüncü fazında tünel açma çalışmaları başladı, https://www.aa.com.tr/tr/gundem/halkali-kapikule-hizli-tren-projesinin-ucuncu-fazinda-tunel-acma-calismalari-basladi/2942415.

[11] ADB (2021), Middle Corridor - Policy Development and Trade Potential of the Trans-Caspian International Transport Route, https://www.adb.org/publications/middle-corridor-policy-development-trade-potential.

[7] ADB (2021), Ports and Logistics Scoping Study in CAREC Countries, https://www.adb.org/publications/ports-logistics-scoping-study-carec-countries.

[19] ADB (2017), Azerbaijan: East–West Highway Improvement Project - Performance Evaluation Report, https://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/evaluation-document/365706/files/pper-aze-ewhip_6.pdf.

[18] ADB (2014), Georgia Transport Sector Assessment, Strategy, and Road Map, https://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/institutional-document/34108/files/georgia-transport-assessment-strategy-road-map.pdf.

[40] ADB (2010), Social Safeguards Report: Georgia Port of Poti Social Compliance Audit Report.

[23] ADBI (2021), Developing Infrastructure in Central Asia: Impacts and Financing Mechanisms, https://www.adb.org/publications/developing-infrastructure-central-asia.

[34] Adilet (2022), On approval of the Concept of Development of Transport and Logistics Potential of the Republic of Kazakhstan until 2030 (Об утверждении Концепции развития транспортно-логистического потенциала Республики Казахстан до 2030 года), https://adilet.zan.kz/rus/docs/P2200001116#z165 (accessed on 21 April 2023).

[3] Adilet (2019), On measures to implement the election program of the President “A Just Kazakhstan - for All and for Everyone. Now and forever” (мерах по реализации предвыборной программы Президента “Справедливый Казахстан - для всех и для каждого. Сейчас и навсегда”), https://adilet.zan.kz/rus/docs/U190000027U (accessed on 25 April 2023).

[8] APM terminals (2023), Port of Poti, https://www.apmterminals.com/en/poti/our-port/our-port#:~:text=The%20Poti%20Sea%20Port%20is,17%20km%20of%20rail%20track.

[36] CAREC (2021), Carec Corridor Performance Measurement and Monitoring, Annual Report 2020.

[1] CAREC (2021), Railway sector assessment for Azerbaijan, https://www.carecprogram.org/uploads/2020-CAREC-Railway-Assessment_AZE_4th_2021-3-4_WEB.pdf.

[6] CAREC (2021), Railway sector assessment for Georgia, https://www.carecprogram.org/uploads/2020-CAREC-Railway-Assessment_GEO_7th_2021-3-4_WEB.pdf.

[5] CAREC (2021), Railway sector assessment for the Republic of Kazakhstan, https://www.carecprogram.org/uploads/CAREC-CRA-KAZ_7th_4MAR2021_WEB.pdf.

[35] CAREC (2018), Strategic Framework for Special Economic Zones and Industrial Zones in Kazakhstan.

[20] CAREC (2010), East–West Highway Improvement Project, https://www.carecprogram.org/?project=east-west-highway-improvement-project.

[25] EBRD (2023), Sustainable transport connections between Europe and Central Asia, https://www.ebrd.com/news/publications/special-reports/sustainable-transport-connections-between-europe-and-central-asia.html.

[31] German Economic Team (2022), Transport- und Handelskorridore in, https://www.german-economic-team.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/GET_UZB_TN_07_2022_de.pdf.

[22] International Trade Administration (2022), Infrastructure, https://www.trade.gov/country-commercial-guides/kazakhstan-infrastructure.

[17] ITF (2023), Transport Statistics (Database).

[43] ITF (2022), Mode Choice in Freight Transport, https://www.itf-oecd.org/sites/default/files/docs/mode-choice-freight-transport.pdf.

[32] KSP (2020), Feasibility Study on Automation of Business Processes in the Port of Baku, https://www.ksp.go.kr/english/pageView/info-eng/735.

[2] Kuryk (2023), Kuryk Port Development Project, https://kuryk.kz/en/kuryk-project/project-description.html (accessed on 20 April 2023).

[26] Ministry of Transport and Infrastructure of the Republic of Türkiye (2023), 2053 Transport and Logistics Master Plan.

[13] Ministry of Transport and Infrastructure, R. (2022), Ulaştırma Ve Altyapı Bakanı Karaismailoğlu: Demiryollarının Yatırımdaki Payını 2023’te %63’e Yükselteceğiz, https://www.uab.gov.tr/haberler/ulastirma-ve-altyapi-bakani-karaismailoglu-demiryollarinin-yatirimdaki-payini-2023-te-63-e-yukseltecegiz.

[44] OECD (2019), Sustainable Infrastructure for Low-Carbon Development in Central Asia and the Caucasus: Hotspot Analysis and Needs Assessment, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/d1aa6ae9-en.

[4] OECD (forthcoming), Improving Kazakhstan’s trade connectivity.

[16] OECD-ITF (2020), Decarbonising Azerbaijan’s Transport System: Charting the Way Froward.

[15] OECD-ITF (2019), Enhancing Connectivity and Freight in Central Asia, https://www.itf-oecd.org/sites/default/files/docs/connectivity-freight-central-asia.pdf.

[39] OSCE (2022), Aktau becomes first certified EcoPort in Kazakhstan with OSCE assistance, https://www.osce.org/secretariat/522520#:~:text=Aktau%20Port%20received%20the%20certificate,sustainability%20of%20the%20transport%20sector.

[30] PMCG (2023), Maritime Trade in the Black Sea in the Context of the Russo-Ukrainian War, https://pmcg-i.com/publication/maritime-trade-in-the-black-sea-in-the-context-of-the-russo-ukrainian-war/.

[33] Rail Freight (2022), Middle Corridor unable to absorb northern volumes, opportunities still there | RailFreight.com, https://www.railfreight.com/specials/2022/03/18/middle-corridor-unable-to-absorb-northern-volumes-opportunities-still-there/ (accessed on 24 June 2022).

[37] SNCF (2020), The Digital Freight Train, https://www.sncf.com/en/logistics-transport/rail-operations/fret-sncf/digital-freight-train.

[38] SNCF (2019), Digital Freight Train: Innovative Services for the Rail Freight Community, http://medias.sncf.com/sncfcom/infosinternes/19LI/19_train_fret_digital.pdf.

[10] TCDD Taşımacılık (2022), 2022 Faaliyet Raporu, https://adminapi.tcddtasimacilik.gov.tr/files/pdfs/TCDD-Tasimacilik-2022-Faaliyet-Raporu%5b26218%5d.pdf.

[41] Tokuslu, A. (2021), Estimating greenhouse gas emissions from ships on four ports of Georgia from 2010 to 2018. Environmental Monitoring and Assessmen.

[29] UIC and Roland Berger (2021), Eurasian Rail Traffic Development: Southern and Middle Corridor, https://uic.org/events/IMG/pdf/presentations_210422_uic_corridor_study_2021_1.pdf.

[12] UNECE (2023), Overview of ongoing and planned operationalization activities in support of the Trans-Caspian and Almaty-Tehran-Istanbul corridors, https://unece.org/sites/default/files/2023-07/ECE-TRANS-WP5-2023-02e_0.pdf.

[42] UNESCAP (2022), Strengthening capacity for operationalizing sustainable transport connectivity along the China-Central Asia-West Asia Economic Corridor to achieve the 2030 Agenda.

[24] University of Central Asia (2023), Transport transision to decarbonisation in Central Asia, https://sipa-centralasia.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/5.-ENG-SIPA_decarb_transport_UCA_1109.pdf.

[28] USAID (2022), Trans-Caspian Corridor Development, https://www.carecprogram.org/uploads/19th-TSCC_A05_USAID-TCAA.pdf.

[27] World Bank (2022), The Container Port Performance Index 2022, https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/099051723134019182/pdf/P1758330d05f3607f09690076fedcf4e71a.pdf.

[9] World Bank (2020), Improving Freight Transit and Logistics Performance of the Trans-Caucasus Transit Corridor : Strategy and Action Plan, World Bank Group, http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/701831585898113781/Improving-Freight-Transit-and-Logistics-Performance-of-the-Trans-Caucasus-Transit-Corridor-Strategy-and-Action-Plan.

[21] World Economic Forum (2020), The Global Competitiveness Report 2020, https://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_TheGlobalCompetitivenessReport2020.pdf.

Note

← 1. Block or unit trains refer to freight trains transporting a single commodity bound for the same destination, without switching cars or stopping for storage purposes along the way.