This chapter provides an overview of regional demographic, economic, labour and social trends in Ukraine prior to Russia’s large-scale invasion of the country in February 2022, laying the groundwork for the policy assessment and recommendations in the following chapters. By analysing Ukraine’s strengths and challenges with regard to various economic and well-being indicators at the regional level, this chapter updates the 2018 OECD report Maintaining the Momentum of Decentralisation in Ukraine, and focuses on issues relevant to regional and local development.

Rebuilding Ukraine by Reinforcing Regional and Municipal Governance

3. Setting the scene: A volatile context for regional development

Abstract

Preface: Regional development trends in the context of the invasion of Ukraine

This chapter identifies demographic, economic and well-being trends at the national and subnational levels in Ukraine, based on data gathered in 2021. The Russian Federation’s invasion deep into government-controlled areas of Ukraine in February 2022 has severely affected the trends presented and discussed in this chapter. However, by highlighting the progress made by Ukraine before the war in reducing regional disparities, as well as the factors underpinning that progress, it provides powerful insights that can help inform and support regional development policy after the war has ended. Indeed, experience from different countries and regions that have implemented post-disaster recovery strategies shows that reconstruction efforts need to respond not only to immediate necessities, but also build on underlying governance, socio-demographic and economic conditions (Government of Puerto Rico, 2018[1]; Ranghieri and Ishiwatari, 2014[2]).

The following paragraphs discuss the relevance and implications of some of the chapter’s main findings for Ukraine’s recovery and reconstruction. They include links to relevant boxes, tables and charts included in the chapter.

The governance dimension

From 2014 onwards, Ukraine made important progress in implementing a series of ambitious judicial and governance reforms (Box 3.2). Particularly strong steps were made at the subnational level, resulting in a significant expansion of the administrative and service delivery mandate of municipalities. This enabled many municipalities to continue ensuring basic service delivery during Russia’s invasion, and to co-ordinate the delivery of emergency support with non-governmental actors. The government should build on this capacity by involving municipalities in the design and implementation of immediate and longer-term recovery efforts. Due to their proximity to citizens, subnational governments are more likely to be well-apprised of local needs in a recovery context, and can partner with local private sector and civil society organisations to ensure the joint implementation of recovery projects, as well as continued service delivery.

Notwithstanding the important advancements in governance since 2015, by 2021 Ukraine still ranked relatively low in several categories of the Worldwide Governance Indicators (e.g. rule of law and control of corruption) (Figure 3.4). As such, it is essential that a national recovery plan further strengthens the rule of law, transparency and oversight, in order to ensure that financial support for recovery projects is effectively administered and accounted for.

The demographic dimension

Over the past decade, Ukraine’s regions have been characterised by population decline (Figure 3.6) and a shrinking labour force (Figure 3.9). The war has aggravated this, with 5.8 million people having fled the country by July 2022, and millions more internally displaced. This has dramatically increased the scale of Ukraine’s demographic challenge, and the strain it brings to productivity and economic development, post-war (UNHRC, 2022[3]). This means that, when implementing a national recovery plan, Ukraine will need to emphasise rebuilding a strong and competitive economy that can attract migrants who left the country before or during the war. Among other elements, this requires ensuring adequate service delivery throughout the country, including in areas that witnessed an important population decline over the past years. In the short term, this also means identifying ways to help internally displaced people contribute to recovery efforts and the economic development of their (temporary) host communities.

The economic dimension

Prior to the invasion, Ukraine's economic growth was constrained by a number of crises (e.g. the Global Financial Crisis, COVID-19, Donbas war). By May 2022, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) expected that in 2022, Ukraine’s GDP would shrink by 35%, an output shock from which the country will take years to recover (IMF, 2022[4]). The trade and co-operation agreements Ukraine has signed with over 40 countries since 2014, however, provides it with a strong basis from which to support an economic recovery in the medium to long term. Ukraine could focus on strengthening its value chains with foreign markets and boost its industrial capacity to export more high value-added manufactured goods, thereby becoming less dependent on the export of primary resources.

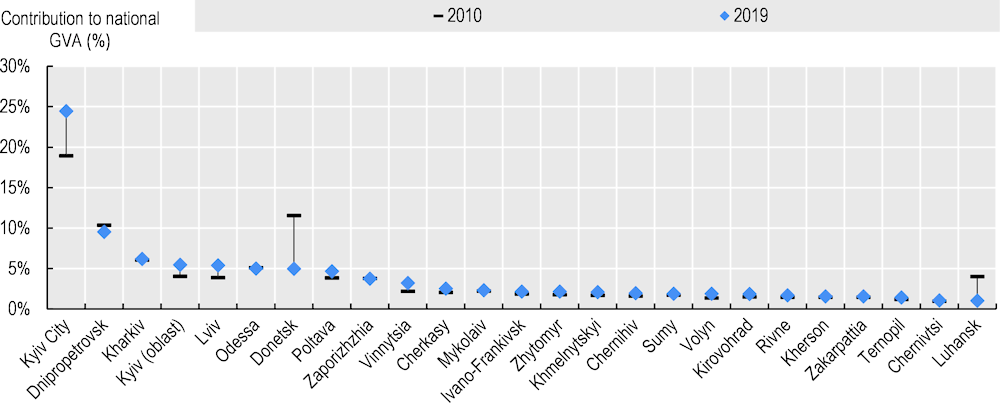

Between 2010 and 2019, Ukraine’s economy became increasingly dependent on the Kyiv agglomeration, with other regions lagging behind (Figure 3.10). This was caused, in part, by the Donbas war that sparked a drop in the gross value added of Donetsk and Luhansk. Given the ongoing nature of the war, two developments are to be expected in terms of regional economic growth. On the one hand, the contribution of eastern regions—where much of the fighting has been concentrated—to the national economy will continue to decline. These regions, in particular, will require extensive support to ensure their recovery. On the other, the economic significance of oblasts located in the west of the country (where agriculture, wholesale and retail trade have been the dominant sectors in terms of employment) will likely increase, as these remain relatively well-connected to the European Union.

The invasion will most likely lead to a large increase in labour informality, which was already very high in several oblasts (Figure 3.15), particularly those in the west of Ukraine. These are the same regions that have received a major influx of internally displaced people. Given this, recovery efforts should reactivate and protect employment, placing a special emphasis on the most vulnerable, excluded and informal groups. There is some evidence that in the immediate aftermath of a disaster, government-led cash-for-work policies can help provide a basic income to people who have lost their jobs and livelihoods, while contributing to recovery efforts (Ranghieri and Ishiwatari, 2014[2]).

The well-being dimension

Russia’s invasion is likely to severely undermine the significant progress in poverty reduction that Ukraine’s regions achieved between 2015 and 2019 (Figure 3.17). At the same time, the continued payments of pensions and functioning of the banking sector, for example, have undoubtedly cushioned the economic blow felt by some households (Ukrposhta, 2022[5]; National Bank of Ukraine, 2022[6]). Besides investing in subnational economic development and job creation, Ukraine’s recovery initiatives should also contemplate financial and material support for particularly vulnerable populations (e.g. internally displaced people, the elderly, children) to make sure that they are able to meet their basic needs.

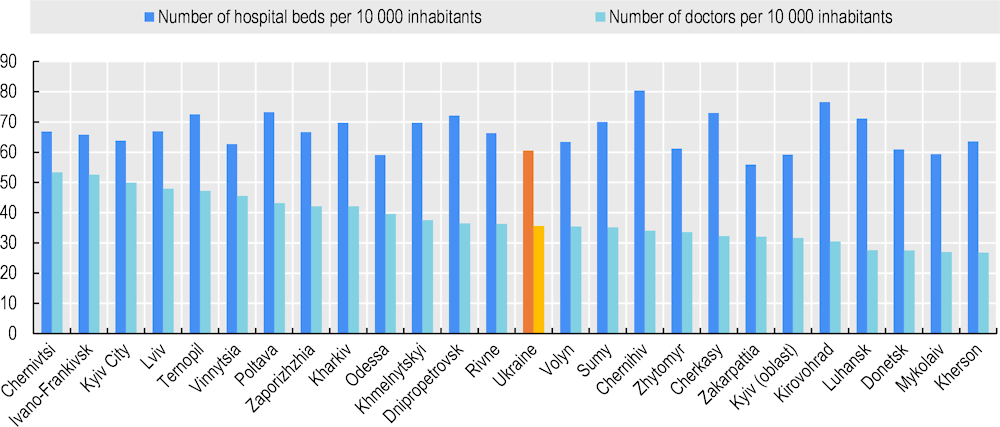

Prior to the war, the number of hospital beds and doctors per 10 000 inhabitants varied significantly across regions (Figure 3.21), with some performing better than the OECD average. These healthcare assets have proven critical for providing medical support during the war. However, many hospitals have been attacked during the invasion, hampering their ability to provide medical relief (Reliefweb, 2022[7]). In a post-war context, Ukraine will not only have to invest in rehabilitating the damaged physical healthcare infrastructure, but also ensure access to mental health and psycho-social support, as mental disorders are prevalent in conflict settings.

Given the scale of destruction in many cities, providing housing should be a key pillar of Ukraine’s recovery initiatives. This not only includes rehabilitating or replacing damaged housing stock. It also involves building new homes, particularly in Ukraine’s western regions where many Ukrainians have sought refuge. Indeed, some of the internally displaced people may not return to their former communities. In this regard, attention should be paid to rural-urban linkages. In rural areas close to cities, the cost of land is often lower than in cities, making them attractive places for new housing development. However, policy makers need to ensure that infrastructure for basic service delivery (e.g. water, electricity, sewage, transport, water, education, etc.) and business opportunities are available or will be developed to match the demands of residents.

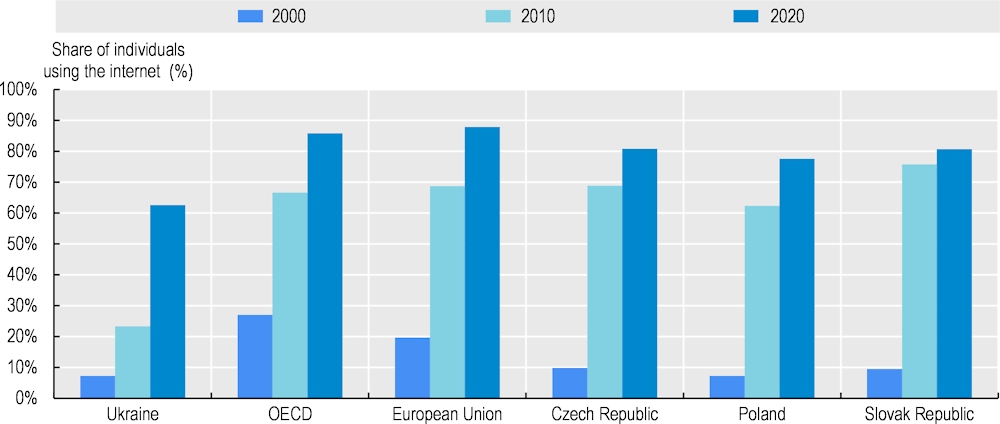

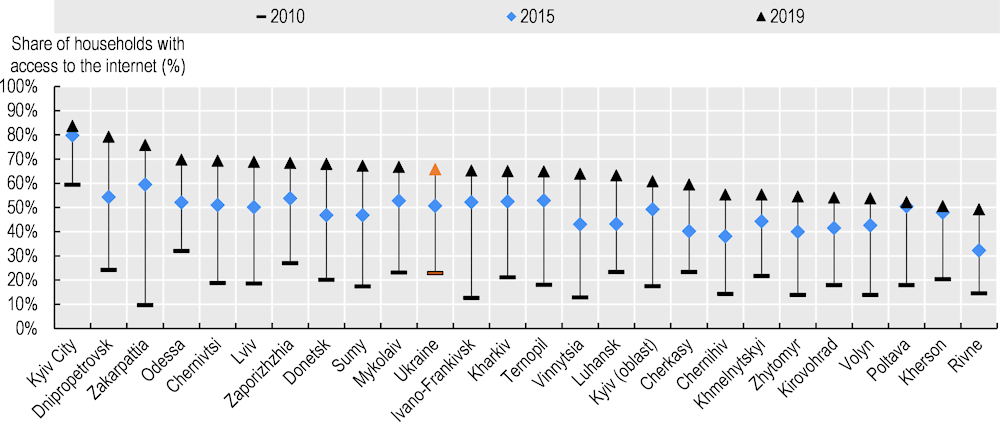

Over the past two decades, Ukraine has made large strides in expanding internet access throughout the country (Figure 3.18). This has proven essential for keeping even relatively remote communities, and those under siege, connected to the internet during the invasion. It has also enabled the continued flow of information among citizens, the government and the international community, as well as access to online public services. Ensuring continued digital connectivity and even expanding coverage is key to recovery efforts as it will support economic activity, allow citizens to stay abreast of relevant recovery initiatives, and facilitate access to different public e-services. This will have to be coupled with the development of user-friendly digital services and business digitalisation.

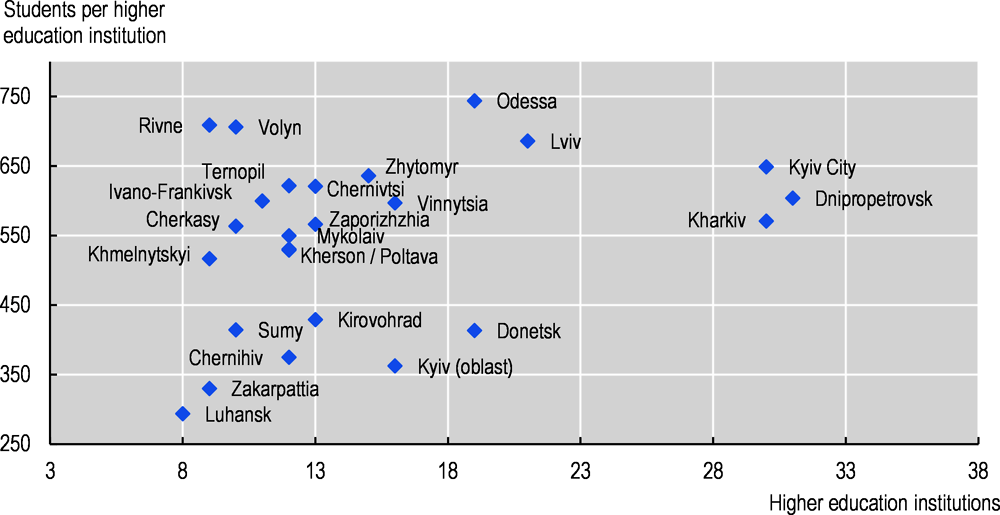

In different parts of the country, online education has continued throughout the invasion (Specia and Varenikova, 2022[8]). This has been possible due to the experience gained during the COVID-19 pandemic and continued access to the internet. Considering the importance of access to quality education, rehabilitating damaged schools and resuming in-class education should be a priority for the country’s recovery, as well as ensuring access to education for adults, in particular war veterans. In doing so, Ukraine can, among other elements, build on the many secondary education institutions that operated prior to the 2022 invasion (Figure 3.20).

Introduction

The 2018 OECD report, Maintaining the Momentum of Decentralisation in Ukraine, was completed four years after the Government of Ukraine began its ambitious decentralisation and regional development reforms (OECD, 2018[9]). The report began with an overview of mainly regional economic trends in Ukraine, highlighting territorial disparities, as well as progress made to redress them. This chapter, which is based on data gathered prior to Russian Federation’s large-scale aggression against Ukraine that began in February 2022, updates and adds to the 2018 work. It evaluates development trends through to 2021, capturing the effects of more recent political and economic shocks, notably the COVID-19 pandemic. Moreover, in comparison to the 2018 report, it explores Ukraine’s national and territorial performance on several well-being indicators. Russia’s war in Ukraine has severely affected the trends presented and discussed in this chapter. However, by highlighting the progress the country made before the war in reducing certain regional disparities and detailing where others widened, it provides relevant insights that can help inform Ukraine’s post-war reconstruction and recovery.

In line with the 2018 report, Ukraine’s decreasing population is a major concern. The chapter finds that almost all of Ukraine’s regions suffer from decreasing populations and shrinking labour forces, with significant implications for labour productivity and economic development as well as the cost of and demand for public services. In addition, it finds that several of Ukraine’s regional economic and well-being disparities are becoming more entrenched, with the national economy increasingly reliant on Kyiv City. This prompts the question of how to strike a balance between the objectives of achieving regional convergence and stimulating economic growth.

These issues notwithstanding, the chapter outlines how, over the past decade, Ukraine has made significant progress in addressing various regional disparities, especially on issues such as poverty reduction and access to the internet. Even on these issues, however, large regional differences persist. To address regional economic and well-being disparities across the entire country, the chapter recommends that the government reinforce its approach to developing and implementing place-based regional and local development policies that take account of local challenges and strengths. Moreover, the development of COVID-19 recovery policies provide an opportunity for the government and Ukrainian subnational authorities to adopt measures to address growing territorial disparities.

The first part of this chapter provides an overview of Ukraine’s macroeconomic context, including trade indicators. It also chronicles the ‘high-level developments’ that have affected Ukraine’s macroeconomic picture, such as domestic and international crises (prior to February 2022) and institutional reform processes. The second part of the chapter looks at economic and well-being trends in Ukraine. It assesses the national performance and compares this with international benchmarks (Box 3.1), as well as exploring how regional performance has changed over time. In so doing, it draws on a range of indicators including demographic trends, regional economic patterns, employment, poverty, internet access, education and healthcare.

Box 3.1. International benchmarks

To compare its regional performance against relevant countries, the analysis provided in this chapter relies on four international benchmarks:

The post-Soviet states benchmark includes 14 states that were part of the Soviet Union before its dissolution in 1991.

The neighbouring countries benchmark consists of the seven countries with which Ukraine currently shares a border.

The OECD benchmark uses the average of the 38 OECD member countries to compare Ukraine’s national performance with that of the OECD.

The European Union (EU) benchmark uses the average of EU member countries to compare Ukraine’s national performance with that of the EU.

Note: See full list in Annex Table 3.A.1. Some countries are featured in different benchmarks. For example, Moldova and the Russian Federation are part of post-Soviet state and neighbouring countries benchmarks.

Source: Author’s elaboration.

This chapter also reflects upon how the scarcity of available data at the territorial level, particularly in the field of well-being, limits the ability of policy makers to assess regional performance. Chapters 4 and 5 of this report cover each of these topics in more detail. In addition, a box evaluating Ukraine’s implementation of the 2018 report’s recommendations related to regional development is included in Annex Table 3.B.1.

Macroeconomic performance and ‘high-level’ developments in Ukraine

Ukraine is the largest country in continental Europe in terms of landmass. It is a unitary state, with twenty-four oblasts (regions), the Autonomous Republic of Crimea and two ‘special status’ cities: Kyiv and Sevastopol. According to estimates, as of December 2021, Ukraine had 41.2 million inhabitants (down from 42.6 million in December 2016) making it the eighth-most populous country in Europe (SSSU, 2021[10]). Access to the Black Sea, through the ports of Odessa, Yuzhne and Mykolaiv, places Ukraine at the intersection of trade routes between Europe, Asia and the Middle East, giving the country potential to become a significant regional trading hub.

Since declaring independence in 1991, Ukraine has effected a three-decade-long transition away from its communist legacy towards a market economy and democratic state. By 2019, its economy had specialised in services (68.4% of GDP) and industrial production (22.6%). The country is home to several major firms in mining, chemicals, the automotive sector, and the aircraft and aerospace industry. Its third largest sector was agriculture (9%), driven primarily by grain production. In 2020, Ukraine was among the world's top ten exporters of wheat and maize (Datawheel, 2022[11]; RFI, 2022[12]).

Half of its total national land is considered fertile, which explains the large agricultural capacity. It has significant mineral wealth, including the world’s largest deposits of commercial-grade iron ore, and the second largest mercury deposits, which are mainly concentrated in the east. Ukraine also has the world’s seventh largest coal reserves, which have historically been an important driver of economic growth. In the context of this significant hydrocarbon wealth and the contribution it makes to national output, transitioning to a zero-net carbon economy will be a major challenge (Ukrinform, 2021[13]).

Ukraine’s economy also boasts an extensive though ageing transport infrastructure that, even before Russia’s large scale aggression, was in critical need of maintenance. In 2021, the road network had a length of 169 652 km, including 47 000 km of state roads and 122 000 km of local roads (United States Department of Commerce, 2021[14]). Since the 1990s, the quality of road infrastructure in Ukraine has deteriorated, while rapid population growth in and around large urban agglomerations (notably Kyiv City) has left existing road and public transport networks unable to keep pace with regional mobility needs (World Bank, 2019[15]; TomTom, 2020[16]). Between 2015 and 2020, a large share of investment for regional development in Ukraine was directed towards maintenance and upgrading of roads and other “hard” infrastructure.

A summary of Ukraine’s macroeconomic performance

Ukraine's economic performance can be explored through a range of indicators, from the consumer price index (inflation) to the employment rate and composition of exports (Annex Figure 3.C.1; Annex Figure 3.C.2; Annex Figure 3.C.3, respectively). These indicators were also at the centre of the OECD’s macroeconomic analysis conducted for previous territorial reports on Ukraine (OECD, 2014[17]; OECD, 2018[9]). The bullet points presented below provide a snapshot of Ukraine’s economic evolution:

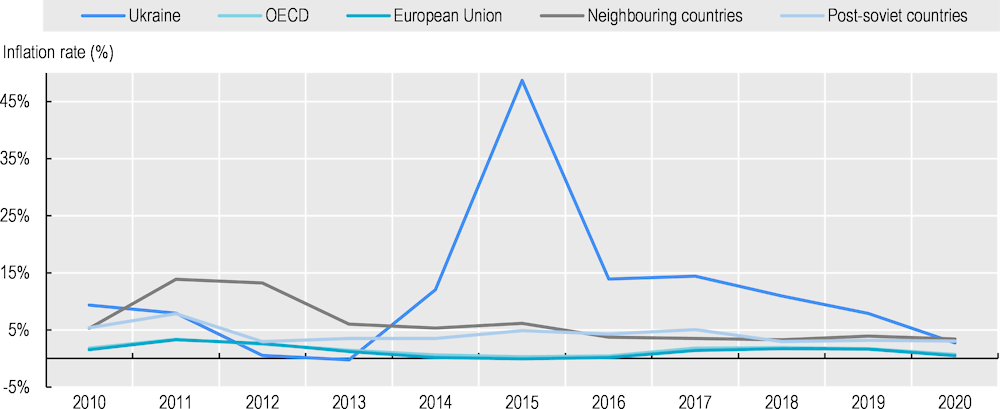

Inflation. Ukraine has experienced significant fluctuations in the price of goods and services over the past decade. In the wake of the Donbas war, inflation rose sharply—peaking at nearly 50% year-on-year in 2015—followed by a sustained but gradual disinflation in the years leading up to Russia’s full-scale invasion.

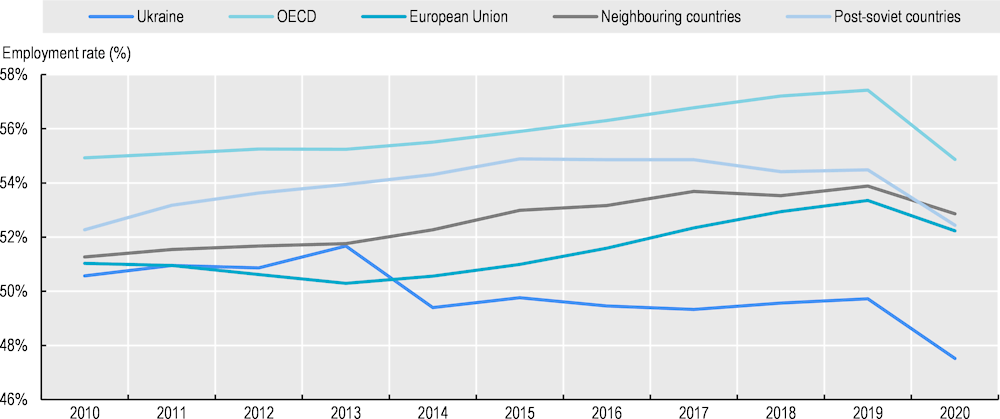

Employment rate. Between 2014 and 2019, Ukraine’s employment rate gradually declined whereas that of the benchmark countries improved. The poor performance largely reflects Ukraine’s ageing population and outgoing labour migration. In the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, the decrease in Ukraine’s employment rate was more profound than that of neighbouring and post-Soviet countries, but on par with that of the OECD.

Volume of exports/imports of goods. Ukraine's trade balance has generally been negative since the early 2000s, but has oscillated over time as a result of currency fluctuations. Improved productivity and new free trade agreements saw expanded access to high-value markets (e.g. Europe), which might be further strengthened if Ukraine becomes an EU Member State.

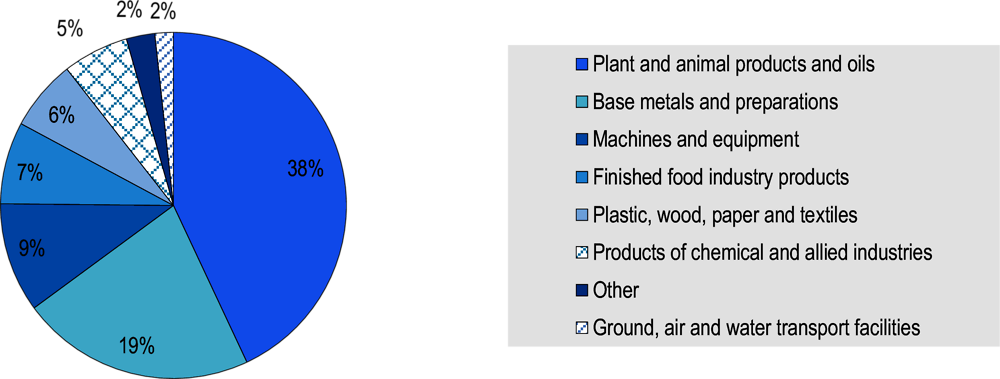

Composition of exports. In 2020, Ukraine’s top export category was plant and animal products, and oils (38%), which reflects its substantial agricultural production capacity. The second highest export category was base metals and preparations (19%), which reflects the country's mineral wealth.

Ukraine’s economic strategy is centred around free trade and competitiveness

In recent years, Ukraine's economic policy has taken a more open stance towards international trade, which centres on boosting domestic production and strengthening relationships with trade partners through bilateral trade agreements. The country aims not only to strengthen its economy, but also to reinforce its diplomatic ties with Euro-Atlantic partners (EC, 2015[18]). In particular, Ukraine has moved to align itself with European and international economic standards and open its market to free trade through a series of actions that include:

Signing an Association Agreement with the European Union (EU) in 2014, including a Deep and Comprehensive Free Trade Agreement, which entered into force on 1 January 2016 (EC, 2015[18]).

Signing over 17 free trade agreements with 46 different countries, including Canada and the United Kingdom.

In June 2022, the European Council granted EU candidate status to Ukraine, opening the way for increased economic, regulatory and political relations (European Council, 2022[19]).

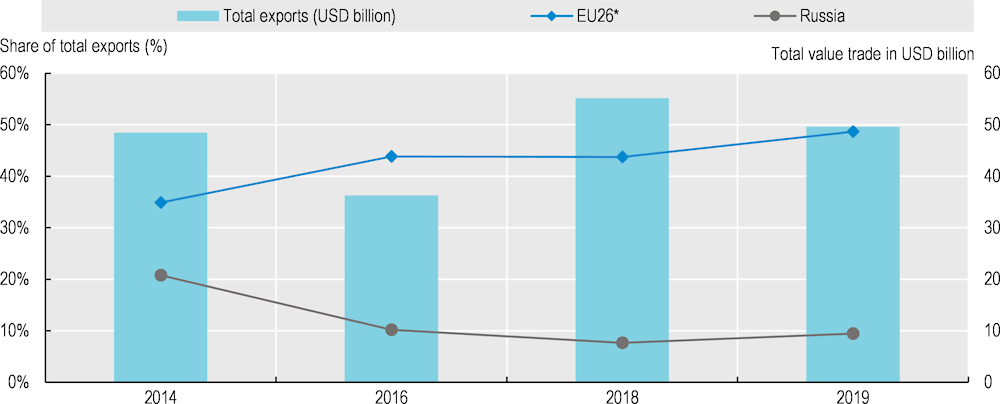

Diversification of trade partners is an important strategy to reduce external vulnerability. In 2019, Ukraine’s most important export destinations were the Russian Federation (USD 4.7 billion), China (USD 3.9 billion), Germany (USD 3.1 billion), Poland (USD 2.8 billion), and Italy (USD 2.6 billion) (Datawheel, 2021[20]). As an economic bloc, however, the EU’s share in Ukraine’s export mix since 2014 has risen sharply, while that of the Russian Federation has declined substantially (Figure 3.1). This is, in part, the result of the removal of trade barriers that has stemmed from the signing of the EU-Ukraine Association Agreement (EC, 2015[18]). The EU accounted for just under half of Ukraine’s total exports in 2019 (48.7%), whereas the Russian Federation accounted for only 9%.

Figure 3.1. Evolution of exports by destination, 2014-2019

Note: *Data related to the area under the effective control of the Republic of Cyprus is not included in the selected EU list of countries as data are not available. Data related to the United Kingdom are also not included.

Source: Author’s elaboration with data from (Datawheel, 2021[20]).

Ukraine has also sought to bolster its competitiveness through measures such as investment and export promotion and simplifying tax administration. Regarding investment promotion, in December 2021, Ukraine adopted a law on the State Support of Investment Projects (also known as the Law on “Investment Nannies”), which provides significant investment incentives to businesses operating in priority sectors of the economy, including exemptions from certain taxes and import duties (OECD, 2021[21]). However, there are concerns that this law undermines the position of small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) as it only supports investments over USD 20 million (OECD, 2021[22]; Verkhovna Rada, 2020[23]).

Regarding tax administration, Ukraine has improved value-added tax (VAT) refunds for SMEs through an automatic refund mechanism, and sought to protect them from late payments through an e-procurement system. Regarding export promotion, Ukraine has supported SME internationalisation by improving its legal framework and complying with EU standards, and providing training, seminars and consulting services via the Export Promotion Office for all businesses wishing to start exporting or enhance their existing export business. (OECD, 2020[24])

Successive crises strained Ukraine’s growth compared to international benchmarks

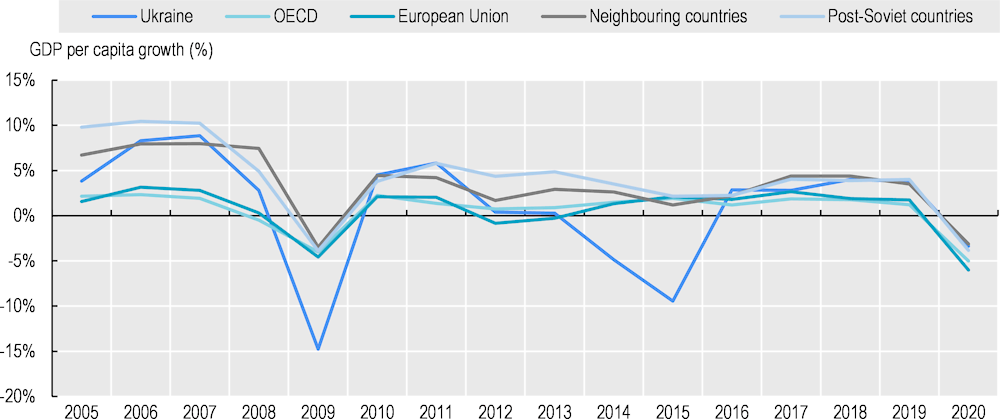

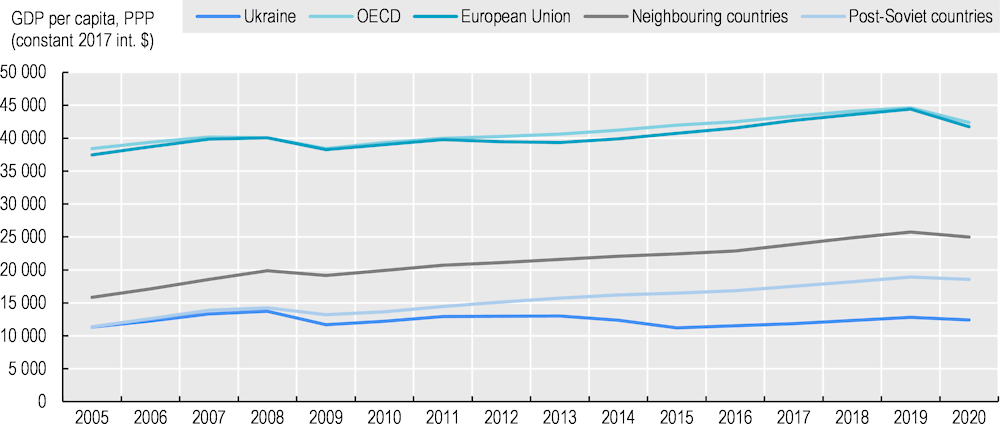

Ukraine has suffered major political and economic shocks over the past two decades. This includes the 2008 Global Financial Crisis, the 2014 Euromaidan revolution, the Russian Federation’s annexation of Crimea, the conflict in the Donbas region, the COVID-19 pandemic and, most recently, the full-scale Russian invasion beginning in February 2022. Overall, the successive political and economic crises have negatively affected the convergence of Ukraine’s economy with post-Soviet and neighbouring countries (Figure 3.2).

Figure 3.2. GDP per capita (PPP) in Ukraine and benchmark countries, 2005-2021

Note: GDP per capita based on purchasing power parity (PPP). Data are in constant 2017 international dollars. PPP GDP is gross domestic product converted to international dollars using PPP rates. An international dollar has the same purchasing power over GDP as the U.S. Dollar has in the United States.

Source: Author’s elaboration with data from (World Bank, 2022[25]).

The Global Financial Crisis caused GDP per capita in Ukraine to shrink by 15% in 2009, compared with an average contraction of 4% among OECD member countries and 4.6% in the EU (World Bank, 2022[26]). Conversely, Ukraine also experienced a faster-than-expected recovery due, in large part, to increased external demand for natural resources, and a lower price for imported natural gas. By 2012-2013, however, the economy had stagnated and GDP per capita growth was close to 0%, unlike in post-Soviet countries and neighbouring countries, where GDP per capita continued to increase (Figure 3.3).

Figure 3.3. GDP per capita growth (annual %) in Ukraine and benchmark countries, 2005-2020

The subsequent 2013-14 Euromaidan revolution also had significant economic ramifications for Ukraine. The government’s refusal to sign an Association Agreement with the European Union (EU) led to weeks of mass protests. The protests ultimately led to a change of government, sparking the Russian Federation’s annexation of Crimea in early 2014 and the Donbas war in 2014-15. During the latter, Russia-backed separatists, supported by Russian forces, seized large portions of Ukrainian territory in the Donetsk and Luhansk Oblasts. In total, Ukraine lost effective control of 7% of its territory as a result of the two events, including the city of Donetsk, which is one of the country’s largest cities and an important heavy industry hub (UN, 2019[27]).

These events generated significant economic volatility, leading to a fall in GDP per capita of 4.9% in 2014 and 9.4% in 2015. However, key structural reforms initiated by the new government, such as introducing a floating exchange rate and inflation targeting, as well as a reduction in the budget deficit, helped reform the economy and unlock a four-year recovery loan programme (USD 17.5 billion) from the International Monetary Fund (IMF) (IMF, 2021[28]). This set the scene for a return to growth—from 2.9% in 2016 to 3.8% in 2019. Growth was also bolstered by the new government’s signing of the EU-Ukraine Association Agreement in 2014, which opened up new and valuable trade and investment opportunities for Ukrainian exporters.

The global COVID-19 pandemic, which resulted in 100 000 deaths in Ukraine up to February 2022 (WHO, 2021[29]), saw GDP per capita contract by 3.4% in 2020, less than the fall of 6% in the EU. By the end of 2021, however, prospects of a substantial economic recovery had dimmed, as the country was confronted with a fourth pandemic wave combined with an energy crisis. The latter was sparked by falling coal and gas deliveries from the Russian Federation, and subsequently by Russia’s full-scale invasion in February 2022.

Ukraine’s governance performance has improved since 2014, but remains strained

Ukraine’s overarching reform programme, which has been implemented since 2014, conceptualises economic development as being intrinsically linked to the development of strong public institutions. Creating solid foundations for sustainable economic growth and investment is dependent on issues such as the protection of property rights and a level playing field for businesses. To strengthen the ability of government institutions to combat corruption and promote the rule of law, Ukraine has received technical and financial support and encouragement from international partners including the IMF, the United States and the EU.

Since the 2014 Euromaidan revolution, Ukraine has made progress in a number of areas, including strengthening the judiciary, the implementation of an anti-corruption programme, as well as promoting fairer competition and improved governance, among other areas. However, there is still work to be done in terms of governance. In addition to the requirements set by the IMF as part of its borrowing programme (IMF, 2021[28]), the government recognises the need to further strengthen its institutions and improve the well-being of its citizens. To this end, it has undertaken a number of major reforms (Box 3.2).

Box 3.2. Examples of recent initiatives to improve governance

Passing the Law on Illicit Enrichment (2019), which re-criminalises illicit enrichment and requires the forfeiture of public officials’ assets that cannot be justified by their legitimate income.

Passing legal amendments to banking regulation mechanisms (2020), which close regulatory loopholes and ring-fence decisions taken by the regulator.

Passing the Law on Amendments to Certain Legislative Acts of Ukraine on Turnover of Farmland (2020), which lifts the 18-year moratorium on the sale of farmland.

Relaunching the High Qualification Commission of Judges and the High Council of Justice (both 2021), which foresee a decisive role for international experts in the selection of judicial candidates.

Source: Author’s elaboration, based on (Reuters, 2019[30]; NBU, 2020[31]; Baker McKenzie, 2020[32]; Atlantic Council, 2021[33]).

The positive impact of the governance reforms is illustrated by Ukraine’s improved performance on the World Bank’s Worldwide Governance Indicators (Figure 3.4), which evaluate progress across six governance categories in over 200 countries. These show that Ukraine improved in all areas between 2015 and 2020. However, it is important to stress that in 2020, Ukraine still ranked low on almost all indicators, including those related to the rule of law and control of corruption, indicating ample room for further improvement.

Figure 3.4. Worldwide Governance Indicators in Ukraine, 2015 and 2020

Note: The measures of governance are provided in units of a standard normal distribution, with zero representing the mean value. The values run from approximately -2.5 to 2.5, with higher values corresponding to better governance. A full explanation of the methodology can be found here (Worldwide Governance Indicators, 2021[34]).

Source: Author’s elaboration with data from (Worldwide Governance Indicators, 2021[34]).

Some of Ukraine’s most ambitious governance reforms have focused on the subnational level. With the aim of improving public service delivery and living conditions in municipalities, as well as strengthening local democracy, the country launched its decentralisation reform in 2014. Key elements of the reform included the territorial consolidation of over 10 000 local elected councils into 1 469 amalgamated municipalities over a six-year period, with a significant expansion of their administrative and service delivery mandates. This was coupled with an increase in local budgets. Table 3.1 outlines how Ukraine’s administrative-territorial setup has changed over the past few years.

Table 3.1. Administrative units at the subnational level, 2017 and 2021

|

Tier/level of subnational government |

Administrative unit |

Number of units |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

2017 |

2021 |

|||

|

First tier |

Regional |

Oblasts |

24 |

24 |

|

Autonomous Republic of Crimea |

1 |

1 |

||

|

Cities (Kyiv & Sevastopol) |

2 |

2 |

||

|

Second tier |

Intermediate |

Rayons (districts) |

490 |

136 |

|

Cities of oblast significance |

186 |

- |

||

|

Third tier |

Self-governments |

Unified territorial communities |

665 |

1 469 |

|

Other cities (of rayon significance) |

235 |

- |

||

|

Other (rural, urban and district councils) |

10 000+ |

- |

||

Source: Author’s elaboration with data from (CabMin, 2021[35]).

Economic development and well-being in Ukraine: trends at the subnational level

As the government’s decentralisation and regional development reform process entered its eighth year (2022), economic and well-being trends at the subnational level revealed significant regional inequities. The COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated territorial disparities, and although some regions coped relatively well with Covid’s twin public health and economic shocks, others have lagged behind, with significantly negative effects on the well-being of their populations. Territorial disparities will also have been significantly affected by Russia’s aggression.

As Ukraine’s government looks to rebuild from the impact of COVID-19 and from Russia’s war, it is essential that economic recovery policies take account of regional and local needs and assets. This section explores subnational variations in economic and well-being indicators, as well as changes in regional performance over time. It should be noted that the lack of available data at the territorial level, particularly in the field of well-being, limits this analysis, and will similarly limit the line of sight that domestic policy makers have over Ukraine’s regional performance.

The well-being analysis draws on the OECD Regional Well-Being Indicators (Box 3.3), which can help policy makers assess regional strengths and challenges, monitor trends and compare results with other regions, both domestically and internationally. Due to a lack of reliable territorial data in Ukraine, not all of the OECD indicators are covered in this chapter (e.g. community or life satisfaction), and other indicators are adapted to better reflect Ukraine’s specific regional economic and well-being context. Decision making to support regional development could be improved with more readily available, territorially-disaggregated data on a wide range of economic, environmental, governance and social indicators. This is discussed in greater detail in Chapter 4.

Box 3.3. OECD regional well-being indicators

Building comparable well-being indicators at the regional level

The OECD framework on measuring regional well-being builds on the OECD Better Life Initiative. It measures well-being in regions with the idea that well-being data are more meaningful if measured at the territorial level, as this enables the capture of local variations. Besides place-based outcomes, the framework also focuses on individuals, since both dimensions influence people’s well-being and future opportunities.

Regional well-being indicators concentrate on providing information about people’s lived experience rather than on means (inputs) or ends (outputs). In this way, they can inform the development of policies that move beyond merely improving certain economic or social indicators, focusing on improved citizen well‑being. Such indicators also serve as a tool to monitor how well-being differs across regions.

The regional well-being framework allows for comparisons and interactions across multiple dimensions to account for complementarities and trade-offs faced by policy makers. At the same time, the comparison of regional well-being indicators over time allows actors to assess the direction, sustainability and resilience of regional development.

Ukraine’s efforts to develop useful and comparable data could capture several well-being dimensions: income, jobs, housing, health, access to services, education, civic engagement, environment and safety—for which the OECD manages comparable statistics at the regional level—and the three additional dimensions of work-life balance, community (social connections), and life satisfaction.

Source: Author’s elaboration, based on (OECD, n.d.[36]), OECD Regional Well-Being (database), www.oecdregionalwellbeing.org.

Ukraine’s demographic decline continues

Ukraine’s last census was conducted over two decades ago. National censuses can provide a reliable basis for official population estimates and statistic. Even before Russia’s war and the massive migration and displacement it caused, the absence of a recent census meant there was a lack of certainty regarding the spatial distribution of Ukraine’s population. In the context of regional development, unreliable population data may lead to an inefficient allocation of public funds as transfers to local budgets (as well as the fiscal equalisation mechanism) are often tied to official population numbers (OECD, 2018[9]).

Ukraine's life expectancy was 72 years in 2019, which was well below the OECD average (80 years). This is partly due to harmful health behaviours such as alcohol abuse and smoking (particularly among men), political instability (e.g. territorial conflict), and a lack of access to healthcare. Alongside other Eastern European countries, it also has one of the most rapidly shrinking populations in the world.

The available data indicate that Ukraine has suffered from substantial population decline over the past two decades. Between 1990 and 2021, the population had decreased by more than eight million people. Low birth rates, high mortality rates and large-scale outward migration have contributed to this trend. By contrast, the average population in OECD countries has grown by 11.2% during the same period. Before the war, the United Nations (UN) projected that Ukraine’s population would decrease by another 18% by 2050, from 44.2 million in 2017 to 36.4 million (WENR, 2019[37]).

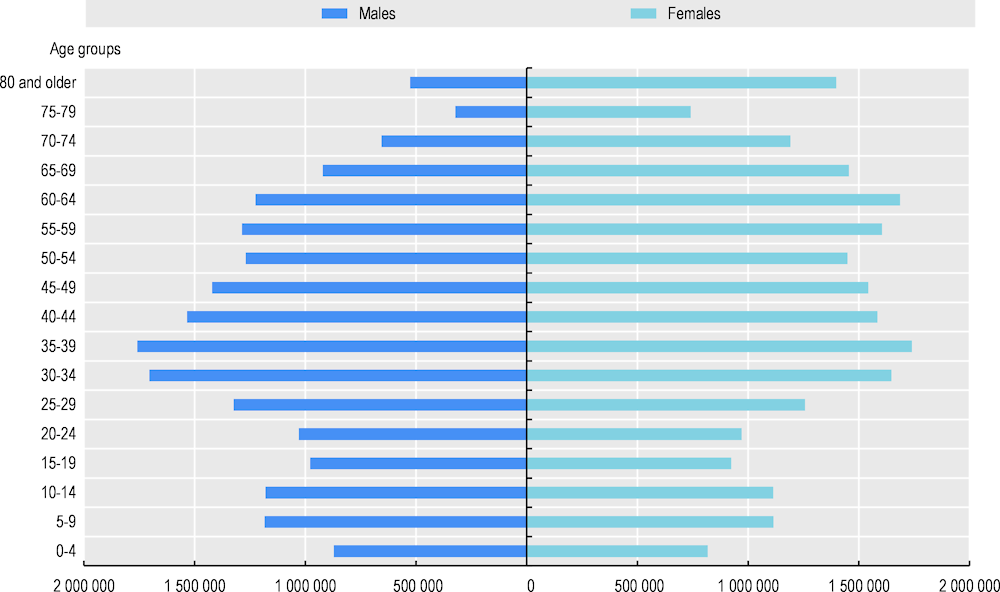

Key shifts in the dynamics of Ukraine's population pyramid over the past decade include a marked decline in new-borns and working-age people (Figure 3.5). Strikingly, the 15-19 year-old cohort that is currently entering the labour force is about 50% smaller than the 35-39 year-old cohort, which could be a major impediment to future economic growth. Another important challenge for the long term is the fact that the population under 5 years of age is even smaller than that of the 15-19 year-old cohort.

Figure 3.5. Age pyramid of Ukraine, 2021

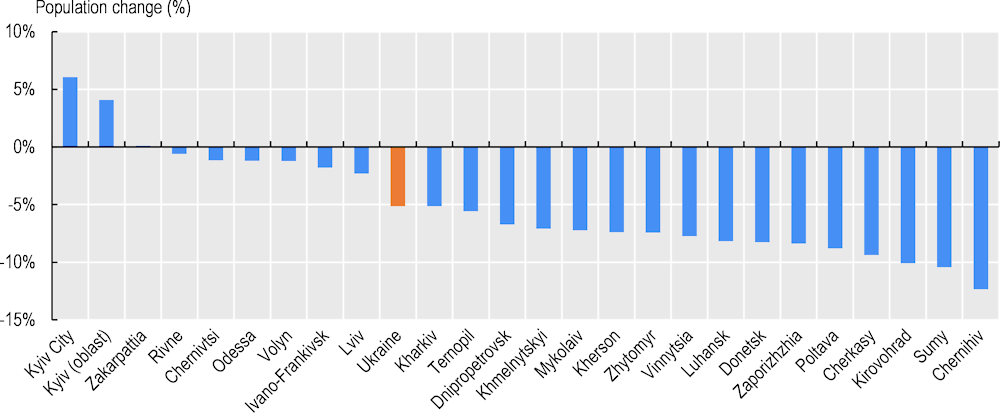

Most regions face population decline and increasing elderly dependency

At the regional level, demographic decline has been observed in almost every oblast, although there are significant regional variations (Figure 3.6). In almost all regions, population growth was either flat (Zakarpattia Oblast) or declining. Only Kyiv City and, to a lesser extent, Kyiv Oblast reported substantial population growth between 2010 and 2021. The reported population decline in several rural regions—where agriculture is the dominant economic sector—has been particularly stark. Chernihiv Oblast suffered the largest drop in population, with a 12.3% decrease between 2010 and 2021, followed by Sumy, Kirovohrad and Cherkasy Oblasts.

Figure 3.6. Population change (%) by oblast and Kyiv City, 2010 and 2021

Note: The chart excludes the temporarily occupied territory of the Autonomous Republic of Crimea and Sevastopol City as, after 2014, no data was available.

Source: Author’s elaboration with data from (CabMin, 2021[35]).

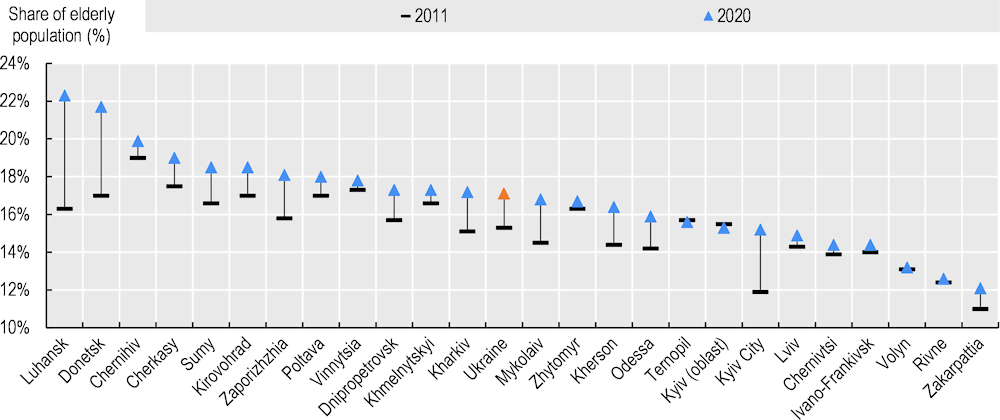

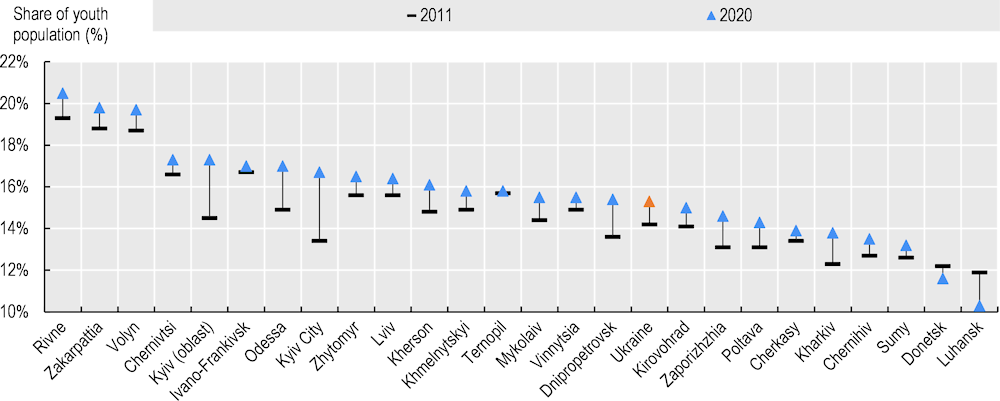

A key variable contributing to Ukraine’s demographic decline is ageing. An ageing population typically includes a lower share of people who are economically active. The impact of ageing on Ukraine's population structure can be seen in Figure 3.7 and Figure 3.8, which look at the ratios between the number of people of working age and a) elderly people or b) young people at ages where they are generally economically inactive.

Figure 3.7. Share of elderly population (aged 65 and older) by oblast and Kyiv City, 2011 and 2020

Note: Share of elderly population (aged 65 and older) over total population. The chart excludes the temporarily occupied territory of the Autonomous Republic of Crimea and Sevastopol City as no data was available. For 2020, for Luhansk and Donetsk Oblasts, calculations (estimates) of the population are made on the basis of available administrative data on state registration of births and deaths and changes in registration of residence.

Source: Author’s elaboration with data from (CabMin, 2021[35]).

Figure 3.8. Share of youth population (between the ages of 0 and 14) by oblast and Kyiv City, 2011 and 2020

Note: Share of youth population (between the ages of 0 and 14) over total population. The chart excludes the temporarily occupied territory of the Autonomous Republic of Crimea and Sevastopol City as no data was available. For 2020, for Luhansk and Donetsk Oblasts, calculations (estimates) of the population are made on the basis of available administrative data on state registration of births and deaths and changes in registration of residence.

Source: Author’s elaboration with data from (CabMin, 2021[35]).

Between 2011 and 2020, Ukraine’s elderly dependency ratio increased by 1.8 percentage points to 17.1%, which was lower than the OECD average (26.8%). During this period, in all regions, except for Kyiv and Ternopil Oblasts, the elderly dependency ratio increased, which can have important implications for the demand for elderly care. The most significant increases were observed in Donetsk and Luhansk Oblasts where the share of elderly population as part of the total population increased by 4.7 and 6.0 percentage points, respectively. This might be explained by increased outward migration of the working age population in both regions as of 2014-2015 (when the Donbas war started).

During the same ten-year period, Ukraine’s youth dependency ratio increased slightly, from 14.2% in 2011 to 15% in 2020, which was below the OECD average (27.4%). Between 2011 and 2020, in 23 regions and Kyiv City the youth dependency ratio either remained stable or increased. It only declined in Luhansk and Donetsk. Moreover, while in 2020, Rivne, Zakarpattia and Volyn Oblasts reported a youth dependency ratio of about 20%, in Luhansk Oblast the share of youth population as part of the total population was only 10%, denoting important cross-regional variation. An increasing youth dependency ratio could imply that more investment is needed in areas such as schooling and childcare. The simultaneous increase in youth and elderly dependency in 21 regions and Kyiv City over the past decade implies that their share of working age population as part of their total population decreased.

The regional variations in economically active populations have important ramifications for the design of regional and municipal development policies. These need to take into account the territorially-differentiated effects that population decline and ageing have on productivity and economic development, as well as the current and future demand for public services. Furthermore, declining populations tend to negatively affect tax collection, putting an additional strain on the national and subnational governments’ capacity to meet their administrative and service delivery tasks and responsibilities. Given the projections for continued population decline in the coming years, national and subnational development strategies need to contemplate interventions for both depopulation adaptation and mitigation.

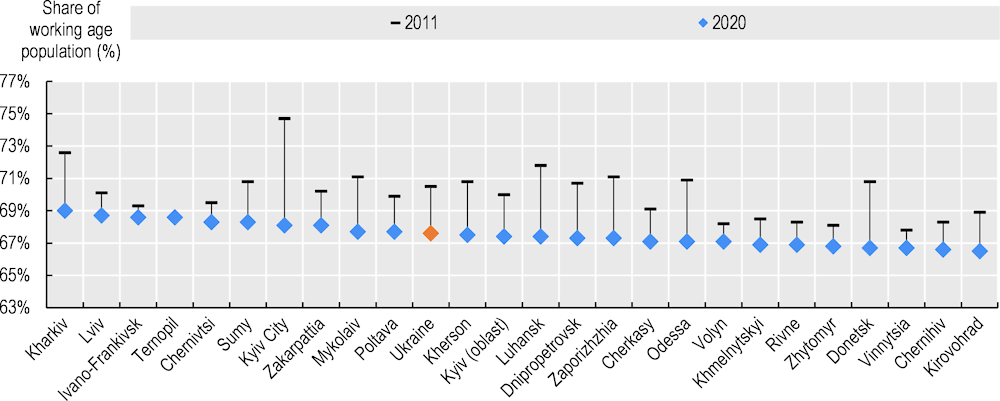

Several regions have experienced demographic outflows affecting the labour market

In almost all regions, Ukraine's labour force has been declining. Over the past decade, the working age population (people aged 15-64) as a share of the total population has fallen from 70.5% in 2011 to 67.6% due to demographic decline (Figure 3.9). These values are similar to the OECD average, which also experienced a drop of 1.75 percentage points. However, while in OECD countries this phenomenon is largely due to the ageing of their populations, in the case of Ukraine, the exodus of working age people to other countries, mainly in the EU, accounts for the largest drop.

Figure 3.9. Share of working age population (15-64) by oblast and Kyiv City, 2011 and 2020

Note: Share of working age population (15-64) as part of the total population. The working age population comprises the 15-64 age group. The chart excludes the temporarily occupied territory of the Autonomous Republic of Crimea and Sevastopol City as, after 2014, no data was available. For the average of Ukraine in 2010, the chart includes the temporarily occupied territory of the Autonomous Republic of Crimea and Sevastopol City. For Luhansk and Donetsk Oblasts, calculations (estimates) of the population are made on the basis of available administrative data on state registration of births and deaths and changes in registration of residence.

Source: Author’s elaboration with data from (OECD, 2021[38]) and (CabMin, 2021[35]).

All oblasts, except Ternopil (0 percentage points), experienced a reduction in the share of the working age population (15-64) as part of the total population. Particularly significant is the case of Kyiv City—which accounts for a very large share of regional GDP and employment—where the decrease in the working age population was 6.6 percentage points. Luhansk (4.4 percentage points) and Zaporizhzhia (3.8 percentage points) also witnessed significant decreases. In the other oblasts, the reported decline was between 1 and 3.5 percentage points, which might be explained by an increased migration of working age population to other parts of Ukraine and/or abroad.

Regional development policies should take into account the effects that the shrinking labour force has on current and future economic development. To stem the flow of migration abroad, the government should also adopt regional development policies that build on local assets to stimulate local economic development, as well as aiming to improve the quality of labour market opportunities in Ukraine compared with other countries.

Regional economic trends point to rising territorial inequality in Ukraine

Ukraine's economic growth has fluctuated heavily over the past decade due to the different shocks mentioned earlier. To rebound from the COVID-19 crisis and set Ukraine’s economy on a more solid footing, the country should build on the comparative advantages it possesses and ensure that growth is broad-based, across all sectors and territories.

As Figure 3.10 shows, the contribution to the national Gross Value Added (GVA) of most oblasts has not changed much over the last decade. Between 2010 and 2019, the contribution of 20 oblasts to the national GVA did not increase or decrease by more than 1 percentage point. Major fluctuations can be identified, however, when looking at Donetsk Oblast, Luhansk Oblast and Kyiv City. Between 2010 and 2019, the contribution of Donetsk Oblast and Luhansk Oblast to the national GVA decreased by 7 and 3 percentage points respectively. This change primarily occurred between 2013 and 2015 and is a consequence of the Donbas conflict. Conversely, between 2010 and 2019, the contribution of Kyiv City to the national GVA increased by 6 percentage points. In 2019, Kyiv City alone contributed 24% to national GVA, up from 22% in 2010. Together, Kyiv City and Kyiv Oblast contributed 30% to the national GVA in 2019. This means that Ukraine’s economy is increasingly dependent on the Kyiv agglomeration, with other regions lagging behind. When excluding the Donetsk and Luhansk Oblasts from the equation, the change in the contribution of Kyiv City to the national GVA between 2010 and 2019 is more moderate (3 percentage points), while the drop in the contribution of Dnipropetrovsk Oblast is more pronounced (3 percentage points).

Figure 3.10. Contribution of oblasts and Kyiv City to the national GVA (%), 2010 and 2019

Note: The chart excludes the temporarily occupied territory of the Autonomous Republic of Crimea and Sevastopol City as, since 2014, no data was available. For 2010, data on these territories was included in the calculation of the contribution to the national GVA of the 24 oblasts and Kyiv City.

Source: Own elaboration, based on (CabMin, 2021[35]).

The increasing reliance of Ukraine’s economy on Kyiv City could aggravate existing economic disparities in the country, with the capital surging ahead while other regions fall further behind. The gap is widening despite the government’s efforts to increase regional competitiveness and cohesion (see Chapter 4). While on the one hand, increasing regional economic divergence may threaten well-being, economic development and social cohesion, on the other, a concentration of people and business (a contributor to economic divergence) could also facilitate faster economic growth. In fact, governments all over the world grapple with the trade-offs between the benefits from agglomeration economies and territorial equity. A key question for policy makers to answer is how to tackle the challenge of lagging regions without compromising a country’s aggregate economic growth (OECD, 2020[39]).

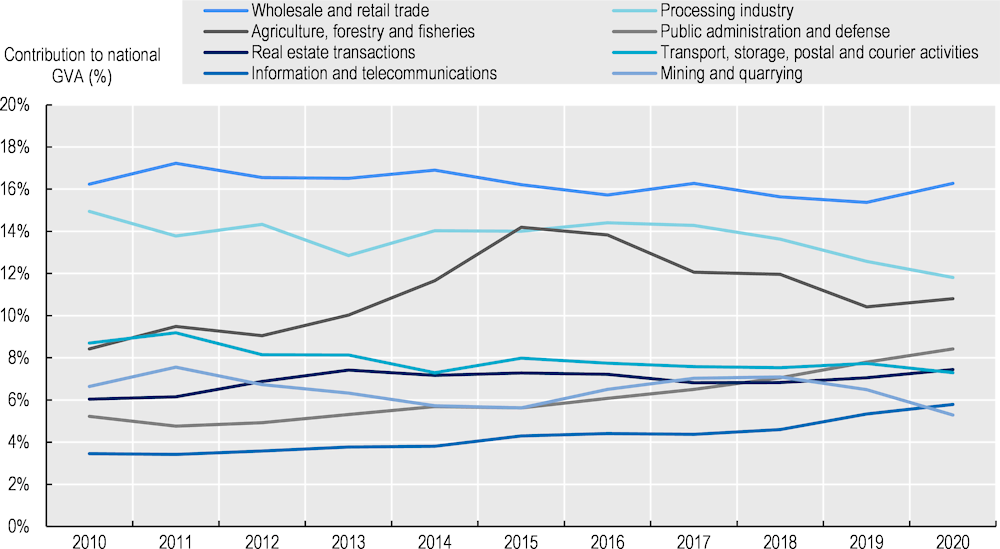

Ukraine’s economic structure has changed significantly in recent years

The structure of Ukraine’s economy has borne witness to significant volatility over the past decade (Figure 3.11). Between and 2015, and 2020 the biggest change occurred in the public sector, which has reported a growth of almost 50%, followed by information and telecommunications (34.8%). Conversely, the contribution of the agriculture sector fell by 23.9%, followed by the processing industry (15.7%), transport (8.7%) and mining (6%). These changes have important repercussions for productivity levels, the demand for business support services by the private sector, as well as the economic basis of regions and local communities.

Figure 3.11. Contribution of economic sectors to national GVA (%), 2010-2020

Note: 2020 values are preliminary and data are given without taking into account the temporarily occupied territory of the Autonomous Republic of Crimea, Sevastopol City, and since 2014 also without part of the temporarily occupied territories in Donetsk and Luhansk regions.

Source: Author’s elaboration with data from (CabMin, 2021[35]).

In 2019, at the regional level, in terms of GVA, agriculture, forestry and fisheries predominated in 14 oblasts. This was followed by wholesale and retail trade, which was dominant in Kyiv Oblast, Lviv Oblast, Volyn Oblast and Kyiv City, and the processing industry (dominant in Donetsk Oblast, Ivano-Frankivsk Oblast, Kharkiv Oblast and Zaphorizhzhia Oblast). Mining and quarrying was the predominant sector in Poltava Oblast and Dnipropetrovsk Oblast, while in Odessa Oblast, transport, storage, postal and courier services was the dominant sector. It is notable that between 2015 and 2019, only three oblasts experienced a change in their dominant industry, denoting relative regional stability in key economic sectors:

Ivano-Frankivsk Oblast: from agriculture, forestry and fisheries to processing industry;

Volyn Oblast: from agriculture, forestry and fisheries to wholesale and retail trade;

Dnipropetrovsk Oblast: from processing industry to mining and quarrying.

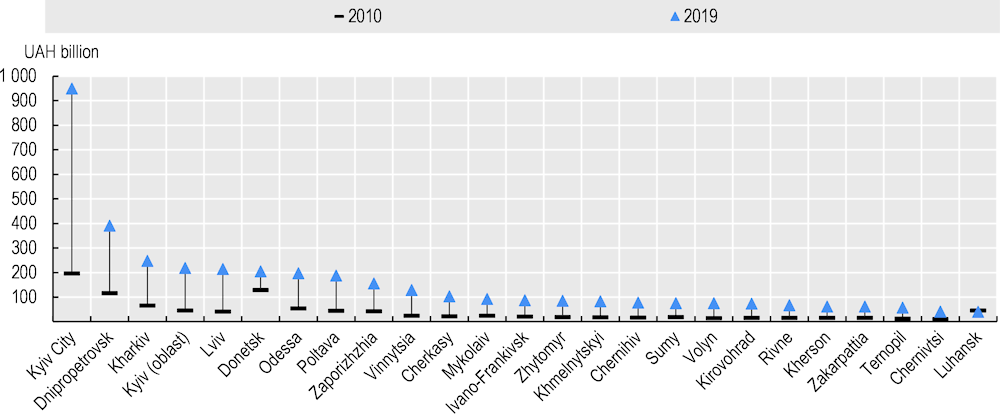

Ukraine's productivity must continue to grow in all regions to improve competitiveness

Low productivity is a critical challenge for Ukraine's development. In 2019, GDP per employed person in terms of purchasing power parity stood at USD 29 245, which is similar to its level in 2012 (USD 28 845). The stagnant productivity of the economy and its uneven territorial distribution contribute to increased inter-regional asymmetries.

At the end of 2019, Kyiv City had the highest volume of Gross Regional Product (GRP) and Luhansk Oblast the lowest (Figure 3.12). It is notable that Kyiv City recorded an almost five-fold increase in GRP per capita between 2010 and 2019. Conversely, many oblasts saw only a slight rise in GRP over the ten-year period, or a drop in the case of Luhansk Oblast. This further highlights how growth in the Ukrainian economy was being increasingly driven by the capital city. The vast differences in GRP growth highlight the need for tailored public investment that builds on local assets, allowing those regions that are marked by limited economic growth to catch up with their peers.

Figure 3.12. Change in the Gross Regional Product (GRP) by oblast and Kyiv City, 2010 and 2019

Note: The chart excludes the temporarily occupied territory of the Autonomous Republic of Crimea and Sevastopol City as, since 2014, no data was available

Source: Author’s elaboration with data from (CabMin, 2021[35]).

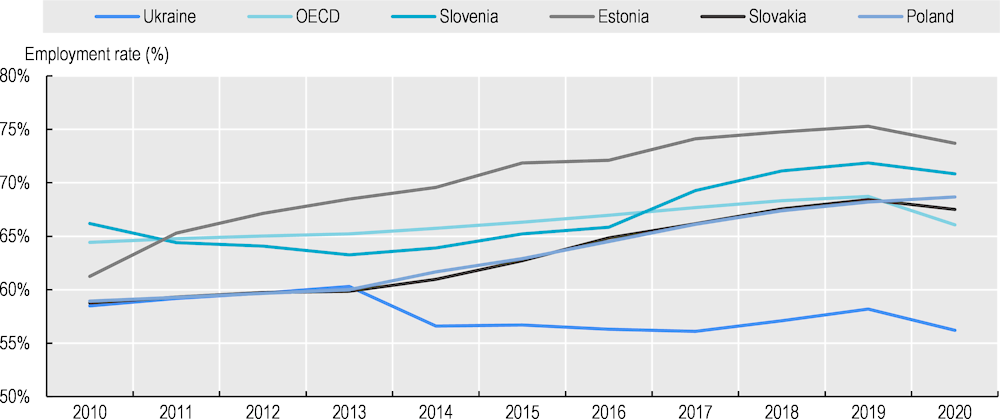

Ukraine is falling further behind its peers in terms of employment rate

In 2020, Ukraine’s official employment rate was 56.2%, well below the OECD average (66.1%), and also below that of other Central, East European and Baltic countries, such as Estonia, Poland, the Slovak Republic and Slovenia (Figure 3.13). Over the past decade, employment rates in all comparator countries increased by between 1.7 and 12.5 percentage points, while in Ukraine they fell by 2.3 percentage points. Besides demographic decline, key labour market challenges include the relatively low share of female participation in the labour force, as well as high rates of labour informality (20.3%). However, these effects are not uniform across Ukraine’s territories.

Figure 3.13. Employment rate in Ukraine compared to selected countries, 2010-2020

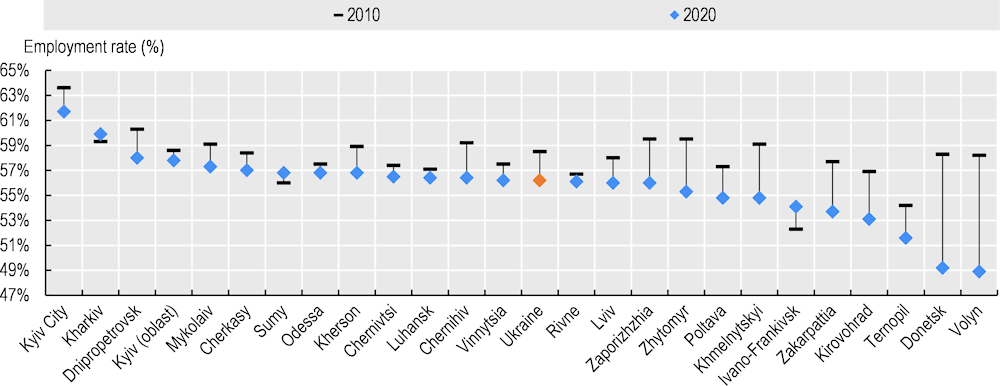

Employment rates vary significantly by oblast. In 2020, Kyiv City had the highest rate of official employment (61.7%), followed by Kharkiv Oblast (59.9%) (Figure 3.14). By contrast, Volyn Oblast and Donetsk Oblast had the lowest rates of official employment (48.9% and 49.2%) respectively. It should also be noted that the rates of employment growth varied significantly across regions. Between 2010 and 2020, only Ivano-Frankivsk, Sumy and Kharkiv Oblasts reported positive growth in their official employment rates (3.4%, 1.4% and 1%, respectively), while all other oblasts and Kyiv City reported declines.

Figure 3.14. Employment rate by oblast and Kyiv City, 2010 and 2020

Note: The chart excludes the temporarily occupied territory of the Autonomous Republic of Crimea and Sevastopol City as, since 2014, no data was available. For the calculation of the national employment rate in 2010, data on both territories was included.

Source: Author’s elaboration with data from (CabMin, 2021[35]).

The variation in regional performance in terms of employment rates illustrates the need to design regional development strategies that provide tailored policy solutions to local employment barriers and conditions. These can include weak employability of the local labour force due to limited work readiness (low work-related skills, education or a lack of work experience), work availability (e.g. due to care responsibilities or health-related limitations) or scarce opportunities due to insufficient job creation. A place-based approach could involve triple helix actors (local firms, education institutions and government) collaborating to develop initiatives that effectively address regional skills imbalances.

Low female labour force participation is holding back regional development

An additional challenge facing Ukraine’s economy is its male-dominated labour market (Table 3.2). In 2020, on average, the labour market participation rate of men was 9 percentage points higher than that of women. However, there were significant regional variations of this phenomenon. In some oblasts, this difference was much higher, reaching 40 percentage points in Zakarpattia and around 25 percentage points in Odessa, Ivano-Frankivsk and Kherson. Only Chernihiv reported balanced labour participation rates, while Kyiv City and Rivne Oblast were the only regional-level administrative units in the country where the labour market participation of women was higher than that of men, by 2 percentage points.

Table 3.2. Subnational employment indicators of Ukraine, 2010, 2019 and 2020

|

Employees aged 15-64 |

Ratio men-women |

Key employment sector in the region (share of employment) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Region |

2011 |

2020 |

Change |

2020 |

2019 |

||

|

Cherkasy |

69% |

67% |

2% |

1.03 |

Agriculture, forestry and fisheries |

28.20% |

|

|

Chernihiv |

68% |

67% |

2% |

1 |

Agriculture, forestry and fisheries |

25.40% |

|

|

Chernivtsi |

70% |

68% |

1% |

1.1 |

Agriculture, forestry and fisheries |

28.30% |

|

|

Dnipropetrovsk |

71% |

67% |

3% |

1.04 |

Wholesale and retail trade |

26.40% |

|

|

Donetsk |

71% |

67% |

4% |

1.08 |

Industry |

25.60% |

|

|

Ivano-Frankivsk |

69% |

69% |

1% |

1.23 |

Agriculture, forestry and fisheries |

29.50% |

|

|

Kharkiv |

73% |

69% |

4% |

1.07 |

Wholesale and retail trade |

24.50% |

|

|

Kherson |

71% |

68% |

3% |

1.21 |

Agriculture, forestry and fisheries |

30.30% |

|

|

Khmelnytskyi |

69% |

67% |

2% |

1.1 |

Agriculture, forestry and fisheries |

28.40% |

|

|

Kirovohrad |

69% |

67% |

2% |

1.05 |

Agriculture, forestry and fisheries |

29.80% |

|

|

Kyiv (oblast) |

70% |

67% |

3% |

0.98 |

Wholesale and retail trade |

27.20% |

|

|

Kyiv City |

75% |

68% |

7% |

1.1 |

Wholesale and retail trade |

23.10% |

|

|

Luhansk |

72% |

67% |

4% |

1.07 |

Wholesale and retail trade |

28.20% |

|

|

Lviv |

70% |

69% |

1% |

1.08 |

Wholesale and retail trade |

20.10% |

|

|

Mykolaiv |

71% |

68% |

3% |

1.11 |

Agriculture, forestry and fisheries |

29.10% |

|

|

Odessa |

71% |

67% |

4% |

1.25 |

Wholesale and retail trade |

24.60% |

|

|

Poltava |

70% |

68% |

2% |

1.12 |

Wholesale and retail trade |

22.40% |

|

|

Rivne |

68% |

67% |

1% |

0.92 |

Wholesale and retail trade |

27.10% |

|

|

Sumy |

71% |

68% |

3% |

1.04 |

Agriculture, forestry and fisheries |

24.20% |

|

|

Ternopil |

69% |

69% |

0% |

1.11 |

Agriculture, forestry and fisheries |

32.80% |

|

|

Vinnytsia |

68% |

67% |

1% |

1.13 |

Agriculture, forestry and fisheries |

34.10% |

|

|

Volyn |

68% |

67% |

1% |

1.13 |

Wholesale and retail trade |

23.20% |

|

|

Zakarpattia |

70% |

68% |

2% |

1.4 |

Agriculture, forestry and fisheries |

26.30% |

|

|

Zaporizhzhia |

71% |

67% |

4% |

1.09 |

Wholesale and retail trade |

22.20% |

|

|

Zhytomyr |

68% |

67% |

1% |

1.09 |

Wholesale and retail trade |

25.40% |

|

|

Ukraine |

71% |

68% |

3% |

1.09 |

Wholesale and retail trade |

22.9% |

|

Note: The dataset from the SSSU excluded data on the temporarily occupied territories of the Autonomous Republic of Crimea, Sevastopol City and a part of temporarily occupied territories in the Donetsk and Luhansk regions.

Source: Author’s elaboration with data from (CabMin, 2021[35]).

In 2019, at the national level, the dominant employment sector was wholesale and retail trade. Agriculture, by contrast, was the dominant employment specialisation of half of the 24 oblasts. Eleven oblasts relied on the wholesale and retail trade sector for their largest share of economic activity. Only in Donetsk was industry the main economic sector, in terms of employment.

High levels of informality constrain Ukraine’s economic outlook

Ukraine’s labour market is characterised by a high level of labour market informality. A 2017 survey of workers across the country showed that 46% of respondents knew someone who worked informally (ILO, 2019[40]). While informal work can provide an important entry point to work and entrepreneurship, a large share of informality in the economy has detrimental effects on a wide range of issues, including worker well-being, public revenues, labour productivity, and fair competition. Furthermore, it can limit well-being by leaving a sizeable cross-section of the population with less access to key public services, such as social protection and healthcare. Moreover, people employed in the informal labour force tend to face high occupational risks. Without adequate policies to manage these risks, such workers will remain particularly vulnerable and may pass this vulnerability on to children and the elderly (OECD/ILO, 2019[41]).Given the pervasiveness of this problem in several regions, the government should make tackling labour informality a key regional development priority.

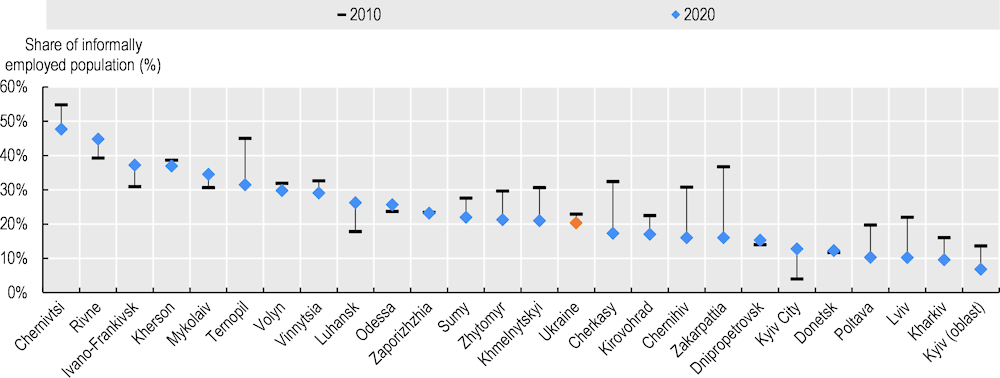

As with other indicators, it is important to highlight the significant regional differences in informal employment (Figure 3.15). Whereas in 2020 almost half of the total workforce of Chernivtsi Oblast and Rivne Oblast was informally employed, in other oblasts, notably Lviv, Kharkiv, Kyiv and Poltava, this percentage was barely 10%. Similarly, the change in informal employment between 2010 and 2020 varied significantly between regions. For example, Kyiv City saw the biggest increase in informal employment (320%), followed by Luhansk Oblast (147%). A key element explaining the increase in informal employment in Kyiv Oblast is the influx of internally displaced people from the Donbas. During the same period, however, informal employment actually declined in 17 oblasts. For example, in Zakarpattia Oblast and Lviv Oblast, informal employment decreased by over 50%.

Figure 3.15. Share of informally employed population aged 15-70 by oblast and Kyiv City, 2010 and 2020

Note: The chart excludes the temporarily occupied territory of the Autonomous Republic of Crimea and Sevastopol City as, since 2014, no data was available. For the calculation of the national share of informally employed people (age 15-70) in 2010, data on both territories was included.

Source: Author’s elaboration with data from (CabMin, 2021[35]).

Informality is generally associated with poverty, lack of access to financial systems, and deficient public health and medical resources. Informal workers are more prone to have few savings and tend to lack access to formal social benefits, which makes them particularly vulnerable to economic shocks (World Bank Group, 2021[42]).

The regional variations in informality highlight the need to develop and implement territorially-differentiated policies that build on local employment and business dynamics, and to match these with measures aimed at increasing formal employment. Depending on local characteristics, such measures could include simplifying regulations, enhancing access to finance and investing in human capital. Measures could also include investment in the digitalisation of services and the creation of one-stop-shops to increase informal workers’ access to public resources (OECD, 2021[43]). Several OECD member countries (e.g. France, Italy and Mexico) use social vouchers as a tool to formalise work by enabling access to particular goods and services. An assessment of French food and meal vouchers, created in 1962, found that they benefited almost 4.5 million workers and 140 000 companies (80% of which are SMEs). The study estimated that for every EUR 1 of contribution from the employer for the vouchers, EUR 2.55 were reinjected into the local economy, resulting in the creation of 164 000 jobs (OECD, 2021[44])

Low wages in Ukraine’s regions are a key driver of emigration

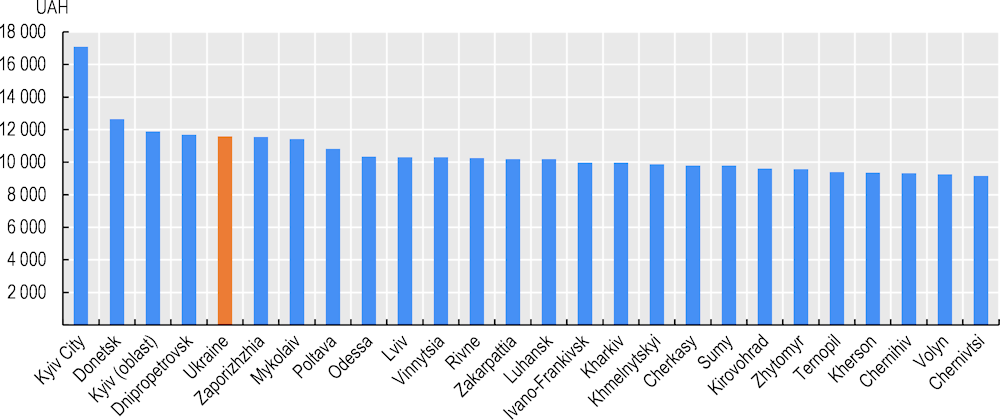

While wages in Ukraine are low when compared to almost all its neighbouring countries, the country also has a large wage differential at the regional level (Figure 3.16). In 2020, the average monthly wage per capita of workers in Kyiv City was UAH 17 086 (USD 633) and that of Kyiv Oblast reached UAH 11 887 (approximately USD 441). This reflects the high concentration of economic and value-added activities in and around the capital. Other oblasts that performed relatively well were Mykolayiv, Zaporizhzhia and Dnipropetrovsk in the central and eastern parts of the country, with average monthly per capita wages of workers between UAH 11 000 and 12 000. Twelve regions had average wages below UAH 10 000, with Chernivtsi ranking the lowest (UAH 9 166, about USD 340), almost half that of Kyiv City.

Figure 3.16. Average monthly wages of regular employees by oblast and Kyiv City, 2020

Note: Wage accruals per pay-roll, in UAH. The chart excludes the temporarily occupied territory of the Autonomous Republic of Crimea and Sevastopol City as no data was available. It also excludes the temporarily occupied territories in Donetsk and Luhansk.

Source: Author’s elaboration with data from (CabMin, 2021[35]).

Low wages are a key driver of outward migration, which has important ramifications for subnational economic development. To address the issue of low wages, policy makers should look to build on the territorial strengths and assets of individual regions, including location, physical infrastructure, and natural and human resources. They could also include the quality of public services, such as education and healthcare.

Indicators of regional well-being in Ukraine

While macroeconomic indicators, such as GDP, provide a good measure of financial or material well-being, they only provide a partial picture of well-being in its fullest sense, including for example the living conditions of citizens. The following sections look at issues such as access to healthcare, education and the prevalence of poverty and crime. They also address how the performance of regions in these areas differs.

Poverty indicators are moving in the right direction across Ukraine

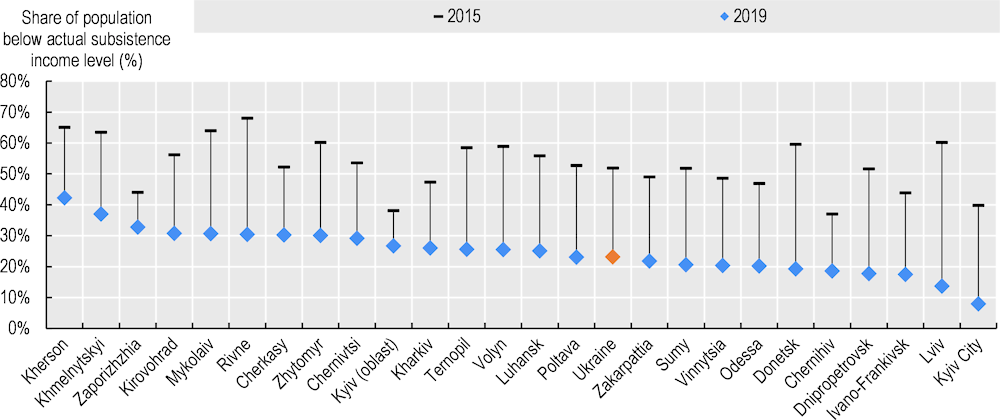

Between 2015 and 2019, there was a significant improvement in the levels of regional poverty in Ukraine. Indeed, the national share of the population living below the actual subsistence income level fell by over half, from 52% to 23%. This decline was driven, at least in part, by real wage growth (World Bank, 2019[45]). Despite regional variations in the extent of the drop, all 24 oblasts experienced a decline (Figure 3.17). The fall was steepest in Lviv Oblast, which went from having one of the highest regional rates of population living below the actual subsistence income (60% in 2015) to one of the lowest (14% in 2019). By contrast, Zaporizhzhia Oblast recorded a decline of only 11 percentage points over the same period. This positive trend has important implications for regional and local development as it may affect the demand for and cost of social service delivery, for example. At the same time, all levels of government are encouraged to gather in-depth data to identify which particular groups and communities are still living in poverty, in order to better design policies and services that address their needs.

Figure 3.17. Population below the actual subsistence income level by oblast and Kyiv City, 2015 and 2019

Note: The average monthly actual subsistence minimum in 2015 was UAH 2 257.0, in 2016 UAH 2 642.38, in 2017 UAH 2 941.46, in 2018 UAH 3 262.67 and in 2019 UAH 3 660.94 per person per month. The chart excludes the temporarily occupied territory of the Autonomous Republic of Crimea and Sevastopol City as no data was available. It also excludes part of the temporarily occupied territories in Donetsk and Luhansk Oblasts.

Source: Author’s elaboration with data from (CabMin, 2021[35]).

Internet access in Ukraine has surged over the past two decades

Internet access in Ukraine has improved significantly over the past two decades, rising from 23% in 2000 to 63% in 2020 (Figure 3.18). However, progress has been much more pronounced in urban centres than in rural areas. Internet access in Ukraine also remains lower than in comparator countries such as Poland (78%), Slovak Republic (81%) or the Czech Republic (81%), and well below the average for OECD countries (86%). The COVID-19 pandemic highlighted the importance of internet access for continued provision of key public services (e.g. education) and to facilitate remote working.

Figure 3.18. Share of individuals using internet in Ukraine and selected countries, 2000, 2010 and 2020

All oblasts have enjoyed increased internet access over the past decade (287% increase on average) and the difference between the best and worst performing regions decreased between 2010 and 2019. At the same time, progress has been uneven across territories (Figure 3.19). Kyiv City has the highest level of internet access in the country (84% of households), followed by Dnipropetrovsk Oblast and Zakarpattia Oblast (79% and 76% respectively). By contrast, the territory with the lowest level of internet access in Ukraine was Rivne Oblast, where only 49% of citizens had access to broadband services. The territorial digital divide illustrated by these data points shows that there is still room for improvement in the rollout of internet networks across Ukraine, particularly in the south and southeast. This is vital not only in the context of the COVID-19 recovery phase, but also more generally to improve service delivery, economic development and the well-being of citizens.

Figure 3.19. Proportion of households that have access to internet services at home by oblast and Kyiv City, 2010, 2015 and 2019

Note: The chart excludes the temporarily occupied territory of the Autonomous Republic of Crimea and Sevastopol City as no data was available for these territories.

Source: Author’s elaboration with data from (CabMin, 2021[35]) and based on the results of a sample survey of living conditions of households.

Access to higher education institutions varies significantly across regions

Ukraine benefits from a high number of secondary education institutions, with regional variations in terms of the number of education institutions and the number of students per institution (Figure 3.20). In 2020, the number of students per higher education institution ranged from less than 300 in Luhansk to 744 in Odessa Oblast. Dnipropetrovsk and Kharkiv Oblasts, along with Kyiv City, had a relatively high number of higher education institutions, as well as a high concentration of students. This concentration of knowledge in specific territorial pockets can weaken access to knowledge in other territories, and affect innovation potential. In order to measure changes in access to education, ideally, data on additional indicators are assessed, such as enrolment rates. However, no such statistics were available.

Figure 3.20. Number of students and higher education institutions by oblast and Kyiv City, 2020

Note: The chart excludes the temporarily occupied territory of the Autonomous Republic of Crimea and Sevastopol City as no data was available for these territories.

Source: Author’s elaboration with data from (CabMin, 2021[35]).

Improving education and skills is essential to ensuring that the supply of human capital matches local labour demand. This not only implies increasing university enrolment, but also improving skills at the lower end, for example by reducing school dropout rates. In fact, regional data from across the OECD show that the share of low-skilled workers appears to have a greater impact on growth than the proportion of workers with tertiary qualifications (OECD, 2012[47]). Policies that aim to upskill the labour force may thus be as important for growth as policies aimed at expanding access to higher education. In this regard, the territorial dimension is critical, as low- to medium-skilled workers tend to be less mobile than those that are highly skilled. This requires policies aimed at addressing skill gaps in order to better adapt to needs and assets (OECD, 2012[47]). To make informed decisions on how to improve access to education and the skills of the local labour force, it is essential for Ukraine to invest in improving the availability of sectoral data on the subnational level. For example, the country should consider gathering regional data on the school enrolment rate of different age groups, the population with upper secondary, post-secondary, non-tertiary and tertiary education, or even the rate of young people not in employment and not in any education and training (NEET).

The government could explore micro-credentials as a means of building expertise and skills of learners of all ages. Micro-credentials refer to a form of certification issued for a relatively small, short and highly targeted learning project. Policy makers have come to see micro-credentials as a way to provide learners with important opportunities for academic advancement, upskilling and reskilling, as well as to improve access to education opportunities overall. When developed together with (higher) education institutions and the private sector, micro-credentials can be a very useful tool to meet (changing) regional and local labour demands (OECD, 2021[48]; OECD, 2020[49]).

Efforts with respect to upskilling and reskilling the adult population are highly necessary. As shown in Figure 3.14, employment rates are low in Ukraine in comparison to the OECD average and especially female labour market participation lags significantly behind that of men. While this suggests a high unmet labour potential, people outside the labour force often have obsolete skills and their (re-)integration into the labour market will require supporting them with upskilling and reskilling to meet the employers’ needs. While difficult to predict, economic restructuring in the post-war period driven by continued digitalisation and the green transition may also imply demand for different and new skills. Hence, also people who actively participated in the workforce before the war may require further education and training to have the skills that meet changing regional and local labour demands.

Territorial disparities in healthcare undermine the capacity of regions to respond to crises

In 2020, the number of doctors per capita in Ukraine (36 per 10 000) was higher than the OECD average (33). However, there were also significant territorial variations with implications for the COVID-19 crisis, particularly given Ukraine’s low vaccination rates, and more recently in dealing with victims of Russia’s aggression. Of the 24 oblasts, 15 were above the OECD average in terms of doctors per capita. Chernivtsi and Ivano-Frankisvk had, on average, more than 50 doctors per 10 000 inhabitants (53.4 and 52.3 respectively). Nine oblasts had fewer doctors per capita than the OECD average: Donetsk, Kyiv, Kirovograd, Luhansk, Mykolaiv, Kherson, Cherkasy, Chernihiv, Zhytomyr and Zakarpattia (Ministry of Health, 2020[50]).

There are also disparities in the number of hospital beds per capita across Ukrainian regions (Figure 3.21). While the number of hospital beds per 10 000 inhabitants in Ukraine stood at 60.5 in 2020, it reached 80.4 in Chernihiv Oblast and 76.6 in Kirovohrad Oblast. On the other side of the ledger, Zakarpattia Oblast had 55.4 beds per 10 000 inhabitants, which was more than the majority of OECD member countries in the same year (OECD, 2022[51]).

Figure 3.21. Provision of doctors and hospital beds per 10 000 inhabitants by oblast and Kyiv City, 2020

Note: The chart excludes the temporarily occupied territory of the Autonomous Republic of Crimea and Sevastopol City as, after 2014, no data was available.

Source: Author’s elaboration with data from (Ministry of Health, 2020[50]).

While territorial variation in access to healthcare is common in OECD countries, it can have important implications for a region’s preparedness to deal with health or other crises requiring medical attention. Improving access to healthcare requires active collaboration among and across levels of governments. For example, inter-municipal co-operation agreements can be developed to improve access to healthcare institutions. Likewise, it may require investment in infrastructure and human resources that respond to local demands. These tend to vary as, for example, the share of the elderly population differs across regions.

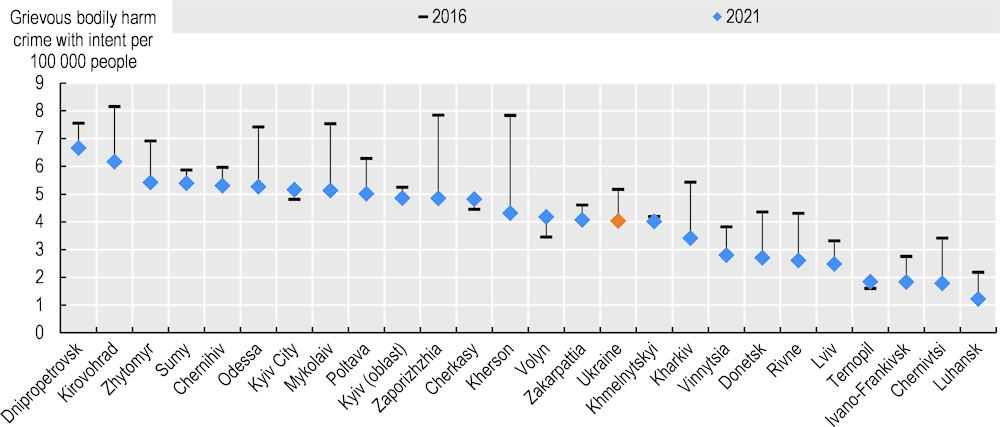

Violent crime in post-Maidan Ukraine declined sharply overall, although regional variations exist

Ukraine saw improvements in the physical safety of its population between 2016 and 2020 across a number of indicators. For example, in this period Ukraine saw a drop in the number of grievous bodily harm with intent crimes that were committed on its territory (from 5.2 to 4.0 per 100 000) (Figure 3.22). The level of this type of crime was generally lowest in the western part of the country. Of the five oblasts that reported the highest rates of this type of crimes per 100 000 people—Dnipropetrovsk, Kirovohrad, Zhytomyr, Sumy and Chernihiv—four were located in the east or southeast of Ukraine.

Figure 3.22. Grievous bodily harm with intent per 100 000 people by oblast and Kyiv City, 2016 and 2020

Note: Grievous bodily harm with intent (Article 121 of the Criminal Code of Ukraine). The chart excludes the temporarily occupied territory of the Autonomous Republic of Crimea and Sevastopol City as no data was available for these territories.

Source: Author’s elaboration with data from (CabMin, 2021[35]).

Crime and violence can have a major impact on the social and economic well-being of communities and citizens. The dynamics of crime and insecurity can severely affect the attractiveness of a region for citizens and companies. This makes public safety an important issue for national and subnational governments to address through place-based regional development policy. Policies should be based on the relationships between violent crime and subnational well-being dimensions to identify complementarities in different policy domains, increasing the effectiveness of policy interventions (OECD, 2014[52]).

Pursuing regional development in a complex environment

The analysis of quantitative data of Ukraine’s performance on a series of socio-demographic, economic, labour, governance and well-being indicators at the national and regional levels point to a mixed performance.