This chapter examines the framework for skilled migrants in Korea, including students, investors and intra-corporate transferees. Korea offers highly qualified foreigners a variety of permit categories with relatively generous conditions for initial residence and rapid access to permanent status. Yet there are few high-skilled foreign workers. The chapter explores the obstacles beyond labour migration policy itself for highly-skilled workers to arrive and remain in Korea. Highly-skilled labour migration policy is analysed in light of the saturated labour market for tertiary-educated residents. It examines the articulation of visa categories for professional foreigners and whether these are suited to the policy objectives. The chapter discusses how these could be adjusted. Finally, the chapter considers the possible relevance of a Secretariat for analysis on the impact and direction of labour migration policy going forward.

Recruiting Immigrant Workers: Korea 2019

Chapter 4. Talent, innovation and investment through migration

Abstract

The statistical data for Israel are supplied by and under the responsibility of the relevant Israeli authorities. The use of such data by the OECD is without prejudice to the status of the Golan Heights, East Jerusalem and Israeli settlements in the West Bank under the terms of international law.

High-skilled workers, international experts and talent

Is Korea attractive?

Despite the large increase in migration to Korea in the past decade, the share of highly qualified workers in Korea relative to both the total migrant population and the highly qualified Korean population remains very low. The total number of foreign workers on permits for highly qualified was about 60 000 in 2016, including more than 15 000 language teachers and about 2 500 tertiary-level professors. The largest group, more than 21 000 specialised workers (E-7), does not necessary have tertiary qualifications. Inflows are very limited. From 2004 to 2015, average annual inflows of E-1 (professors) was under 500; that of researchers (E-3), about 730 annually; and that of professionals (E-5) about 110. Intra-company transfers and temporary employees of Korean firms are counted separately, but amount to fewer than 2 000 annually, with most staying only the time their firm posts them to Korea. In addition to these temporary permits, some skilled foreigners have obtained permanent residence (F-2 and F-5, primarily), but in very small numbers.

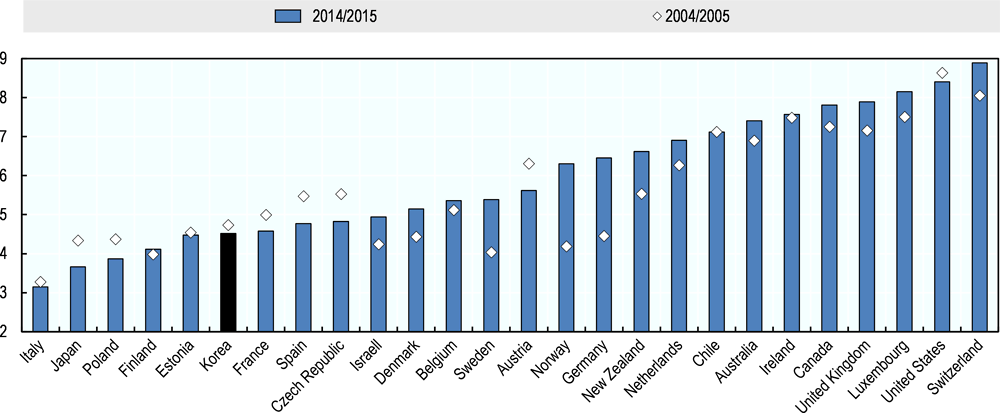

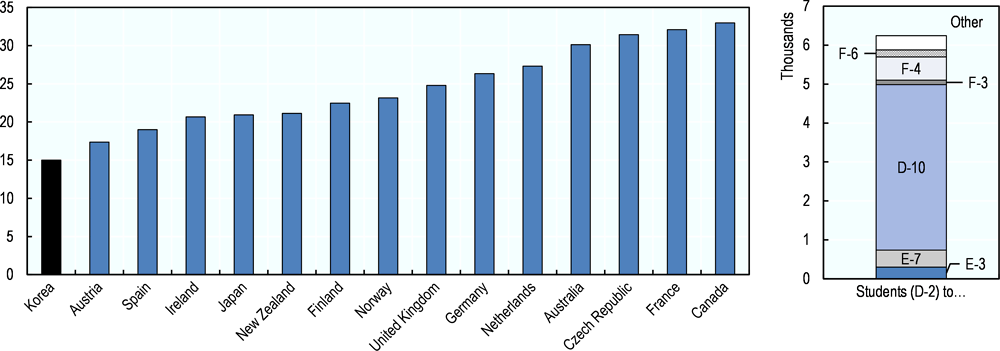

The first factor business environment in Korea is not considered, in international comparison, among the attractive destinations for foreign talent in OECD countries (Figure 4.1).

Figure 4.1. Korea is not one of the most attractive destinations for talent in the OECD

Source: World Competitiveness Yearbook, 2004‑2015.

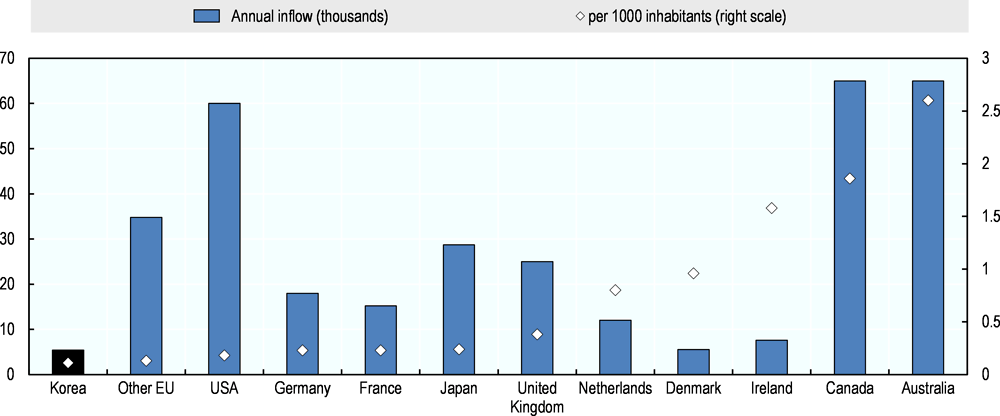

Skilled migration inflows in Korea are limited, and much lower than in other OECD destinations in both absolute terms and relative to population (Figure 4.2). Inflows are about 5 400 in the main skilled worker categories annually, or about 0.1 per thousand inhabitants, lower than in other major destinations.

Figure 4.2. Korea has very low levels of skilled migration

Note: For USA, Canada and Australia, primary applicants approved under permanent economic migration channels. For other countries, qualified migrants with temporary permits allowing indefinite renewal and change to permanent status. For Korea, E-1, E-3‑5 and E-7 visas.

Source: National immigration authorities.

The permit framework for skilled labour migration

Migration policy for the highly qualified has historically been open in Korea, with few limits placed on migration for employment for researchers, executives and managers, and highly-qualified foreign professionals. Specific visa categories have been in place since the late 1980s for teachers and international personnel.

The framework for skilled migrants comprises a number of different visa categories, primarily E-1 through E-7, but also including several D visas, especially D‑7 through D-9.

There is no labour market test for any of the visas, in the traditional sense of a mandatory job advertisement period or a requirement that employers seek resident workers prior to recruitment from abroad. However, a number of visas in the E category, notably the E-5 and the E-7 visa, require a letter of recommendation of employment from the head of state administration or a document which can prove the necessity of employment. Without these documents, the Korean Immigration Service will not approve the visa application.

The main category is the E-7 visa for Specially Designated Activities, for skilled work in a number of authorised occupations. The E-7 permit is divided into a number of separate grounds for admission. First, applicants must work in one of the eligible occupations (see Annex Table 4.A.1). The list of eligible occupations is determined by and announced by the Minister of Justice. The number of occupations on this list vary; in 2014 there were 78 jobs eligible for the E-7, rising to 85 in 2015, cut back to 82 in 2017 and back to 85 in 2018. Not all of these jobs required a tertiary degree or advanced skills; the list includes cooks, as well as tourism-related jobs where foreigners might be employed, such as hotel receptionists and event planners. It also includes a generic category “skilled worker”, for which discretionary approval by the Immigration Service is required based on supporting documents such as an official recommendation by KOTRA (Korea Trade-Investment Promotion Agency), as will be described below.

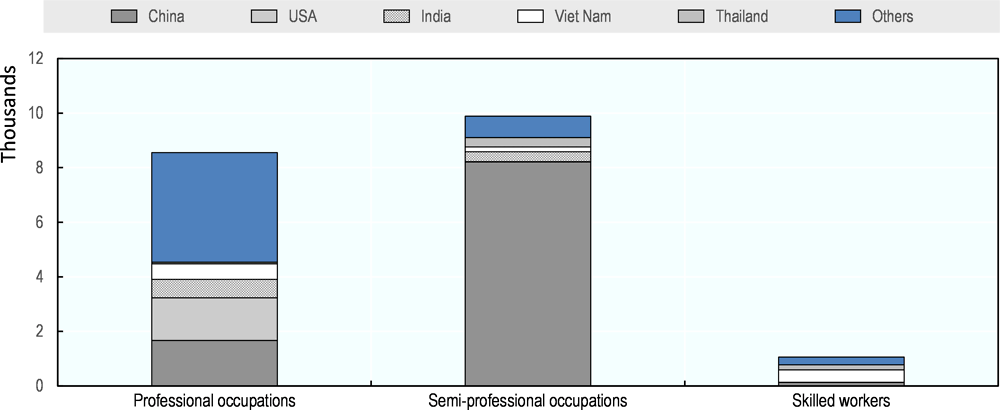

Figure 4.3. E-7 visas are mostly for professions and semi-professional jobs

The eligible occupation list is not, strictly speaking, an occupational shortage list. Most of the occupations on the list are specialised occupations requiring specific professional, linguistic and cultural competencies which, while not in shortage in Korea, may justify recurrence to a global talent pool. The less qualified jobs on the list, on the other hand, reflect occupational priority rather than a verified shortage. Occupations classified into group three are eligible only if the employer has a workforce with less than 20% E-7 workers. An employer could have 20% E‑7 workers, but also a large number of foreign workers on other permit grounds employed in the same firm.

The E-7 occupation list is different from shortage occupation lists used in most migration schemes in OECD countries (Box 4.1), which are based on vacancies or priority occupations and which often exempt from a labour market test.

Box 4.1. Occupation lists for migration in OECD countries

Korea does not use a shortage occupation list (SOL) in its labour migration management system. SOLs may be used for two purposes: to identify which occupations are eligible for recruitment of foreign workers, or to exempt recruitment from requirements such as salary thresholds or labour market tests which apply to recruitment of foreign workers.

Most often, SOLs are used to exempt from the labour market test, on the basis that there is little point in advertising vacancies when the shortage of labour has already been demonstrated. This accelerates recruitment.

In other cases, the SOL is used to justify a lower salary threshold (e.g., the EU Blue Card) or eliminates it altogether (as in Austria’s Red-White-Red card).

In several countries, the SOL determines which occupations are open to recruitment, as in Greece or under several admission programmes in Australia and New Zealand.

Finally, the SOL can be used to prioritise applications in a PBS (used in New Zealand and Canada).

Developing a SOL is often a complex procedure in the hands of an expert body (Chaloff, 2014[2]), requiring regular update to remain relevant (some countries update the list every six months, although the United States has not revised its list in decades). Some SOLs are based on short-term labour market indicators such as vacancy rates (e.g., in Spain), while in other countries they are meant to take into account structural or long-term needs (the Australian Skilled Occupation List or New Zealand Long-Term Skill Shortage List). The effort to develop a SOL needs to be weighed against its effective use in the migration system; in the United Kingdom, the SOL involves regular and onerous consultation and study, even as it only covers a fraction of labour migration flows, most of which are labour-market tested. Nonetheless, the Migration Advisory Committee in the United Kingdom, originally established to determine the SOL, gradually received a broader mandate to conduct analysis and propose policy solutions in response to government queries.

The E-7 visa requires proof of qualifications, either through a masters-level degree, a bachelor-level degree with one year experience, or five years’ experience in the relevant field for those with no tertiary degree.

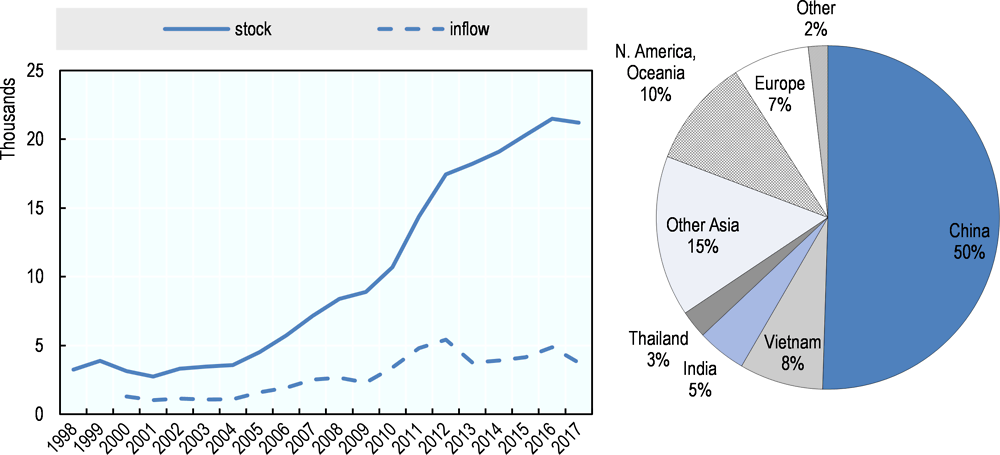

There were more than 20 000 foreign residents holding E-7 visas in 2017, indicating a sharp increase since 2010 (Figure 4.4). While inflows of E-7 visa holders from abroad have also increased over the period, the annual inflow is below 5 000.

Figure 4.4. The number of E-7 visa holders has risen sharply in recent years

Source: International Migration Statistics of Statistics Korea for inflow, Korean Immigration Service fo stock.

Graduates of universities in Korea who find employment are also eligible for an E‑7 visa regardless of the job, as long as it is requires tertiary-level education.

The E-7 visa is subject to a firm-level restriction, as a safeguard, that no more than 20% of all employees of the firm are foreign nationals, and firms with fewer than five employees (registered with the National Insurance Scheme) may not request an E-7 visa.

Box 4.2. Firm-level ceilings as a migration management tool

Korea imposes a variable firm-level limit on employment of E-9 workers (Table 3.3) and a 20% limit on employment of E-7 workers. This is meant to prevent firms from becoming overly reliant on foreign workers. Several other OECD countries use this firm-level cap within their skilled migration programmes.

In Canada, since 2014, there has been a cap on the number of low-wage positions in a firm – specific work location – which can be filled by temporary foreign workers. The cap applies wherever the wage is below the provincial or territorial median hourly wage. The cap was set at 20% for firms with low-wage TFWs hired prior to the introduction of the cap, and 10% for firms hiring low-wage TFWs following the introduction of the cap. Exemptions to the 10% cap are in place for some categories of firms and some occupations.

Turkey imposes a firm-level limit on employment. In general, there is a five-to-one ratio required, with at least five Turkish workers employed full-time for each new foreign worker hired at a firm. Some exemptions are in principle allowed, but in practice have not been implemented. Work-permit-exempt employment may also be subject to a ratio; for example, public-benefit associations may employ up to one-third of their staff permit-exempt. Employment of Syrians under temporary protection is ratio-exempt in agriculture.

Chile has a largely open work permit regime for foreigners in the country legally, but the Labour Code imposes restrictions on larger firms. Employers with more than 25 employees must certify that at least 85% of their total employees working in Chile are Chilean nationals. Some foreign nationals are however included as citizens in the calculation: foreign spouses and surviving spouses; parents of Chilean nationals; and foreigners resident in Chile for more than five years. Other exemptions apply to certain expert technical staff. Foreign investment firms can also apply for an exemption by providing detailed justification.

Ireland has a “50:50 rule”, under which an employment permit will not be issued unless half of the employees in a firm are EEA nationals. Exceptions apply for certain start-up firms and for one-person firms.

Employment ratios may also be taken into account in fee structure and compliance mechanisms. The United States, for example, considers “H‑1B dependent employers” those which have above certain share of their workforce employed under H-1B visas. The threshold is 15% for firms with more than 50 employees, but higher for smaller firms. Firms classified as “dependent” are subject to a more rigorous labour market test. Higher-salary and higher-education workers are exempt from this more rigorous labour market test. Australia introduced a “non-discriminatory workforce test” in 2018 to its Temporary Skills Shortage visa. The discretionary test adds review to requests for workers from firms with a high (or above-the-norm) share of foreign workers in their workplaces.

Within the E-7, there are a number of channels meant to favour migration by individuals with specific skills, through “recommendation” by a trusted body which attests that the individual has the specific skills on the occupation list.

The so-called “Gold Card System” for technology talents was introduced in November 2000 for one occupation (e-commerce). The E-7 visa issued as a Gold Card offers a longer duration (three years instead of two maximum, raised to five years in 2007). In 2003, the number of eligible occupations for the Gold Card was expanded to include seven additional fields (nano-, bio-, transport, material, environment and energy technology), and in 2006 technology management was added. Initially, the Ministry of Industry, Commerce and Energy provided a recommendation; since 2011, the government body providing the recommendation is KOTRA. The service is provided for the IT field, for anyone with a master’s degree; for applicants with a bachelor degree in the field of expertise; for those with a bachelor’s degree in a related field and one year experience; or for those with five years of experience. KOTRA evaluates the degrees and certification of experience and provides a recommendation letter for the E-7 visa.

Also in 2000, two other special cards were offered, for information technology (the “IT Card”) and for scientists and engineers (the “Science Card”). The IT card was issued following recommendation from the Ministry of Information and Communication; in 2009 it was merged with the Gold Card under KOTRA. The Science Card requires support of the Ministry of Science and Technology. Like the Gold Card, they offer three-year duration. The Gold and Science cards allow cardholders to employ foreign domestic workers (under the F-1‑24 visa sub-category), who would otherwise not be admitted for employment in Korea.

KOTRA also offers a recommendation service for skilled workers hired by export-oriented Korean firms through its ContactKorea service. ContactKorea was created in 2008 by KOTRA to target global professionals for work either in Korean companies, to increase their capacity for global markets, or for Korean companies in Korea for employment in export-oriented positions. ContactKorea is meant to bring talent to Korea. While ContactKorea focuses on professional employment, ContactKorea can also support applications by foreigners for E-7 visas, which require demonstration of a “special ability”. ContactKorea can attest to the special ability justifying the issuance of this visa.

Visa procedures for a number of skilled worker categories was introduced in 2010 as “HuNet Korea”, an on-line application to join pool for foreign skilled workers interested in working in Korea. Recommendation was limited to a subset of occupations eligible for E-1 to E-5 permits and the higher-skilled professions under the E-7 permit. HuNet Korea relied on “visa nominators”, unpaid third parties approved by designated attachés within Korean embassies and by the Korea Business Centres (under KOTRA). The role of the designated visa nominators was to review applications by individuals and recommend they be included in a database (pool) of human resources. Korean companies were allowed to search this pool, while individuals in the pool could consult job vacancies.

The use of a designated third-party nominator to validate candidate qualifications represented a novelty in the international migration system, in terms of certification of the legitimacy of applications. While corporate third parties such as professional bodies, universities or arts boards are used to validate the competences of individual applicants (as under the United Kingdom’s nomination system for its Tier 1 exceptional talent visa), no country uses trusted individuals. HuNet relied on the assumption that neutral and disinterested experts could be found, providing review of candidates in return solely for recognition of their own expertise and motivated by a desire to strengthen ties between their country of residence and Korea. This assumption proved difficult to realise, and the HuNet nomination system ended in 2011. KOTRA continues to nominate candidates under the ContactKorea scheme, and is the only body which can verify the academic and professional qualifications of candidates in the job pool; it does so only after a job offer has been found.

HuNet introduced on-line visa application for the first time. Approved profiles in the HuNet database were granted access to on-line visa application, eliminating the need to go to a Korean consular representative in person. This facilitation is maintained for skilled workers and investors.

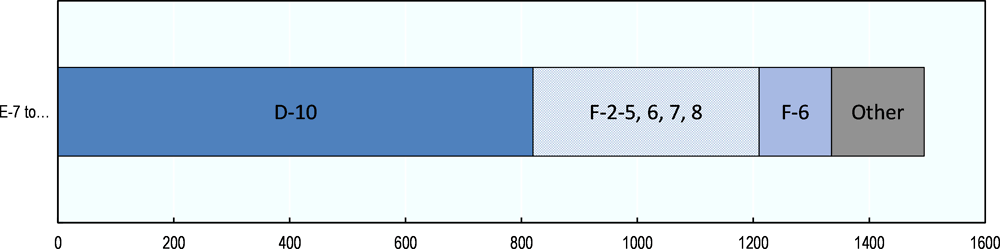

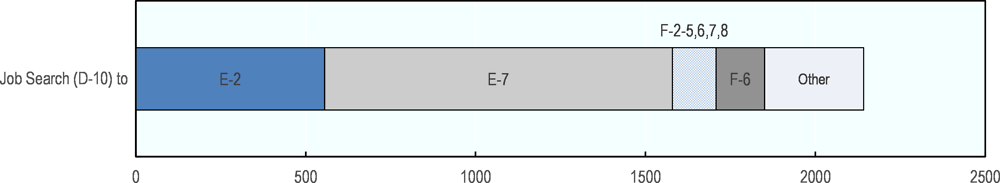

The E-7 visa requires that the holders remain in the occupation for which they were recruited and with the employer for whom their permit was authorised. They are allowed to seek employment with other employers who meet the same conditions. However, there is no job search period in case of unemployment. It is noteworthy that about 8% of E-7 permit holders switched into the D-10 job-search permit in 2015; this was more common than acquisition of permanent residence (Figure 4.5). The job-search permit is the only grounds on which an unemployed E-7 permit holder can switch employment.

E-7 holders may bring family members, but their family members may not take up employment without changing their visa.

Figure 4.5. Many Specialty Workers use the D-10 bridging visa

Source: Korea Immigration Service, 2016.

Intracorporate transfers and employees of multinational firms

One of the main channels for skilled migration into Korea has not been local hiring of foreigners by Korean enterprises, but different forms of mobility within multinational firms operating in Korea or Korean forms bringing employees from abroad for training and knowledge transfer. Intra-company transfers and related detached workers in Korea, holding D-7 to D-9 visas, amounted to more than 10 000 workers in 2017; until 2011, workers holding these visas outnumbered locally hired E-7 visa holders.

Table 4.1. D-7 through D-9 visas

Sub-categories of detached workers and intracorporate transfers.

|

Visa code |

Subject |

Type of beneficiary |

|---|---|---|

|

D-7‑1 |

Intra-Company Transferee (Foreign Company) |

Employee of a least 1 year at a foreign public institution or of a foreign company, dispatched to affiliates, subsidiary, or branch Korea in a field requiring expertise |

|

D-7‑2 |

Intra-Company Transferee (Domestic company) |

Employee of a least 1 year at an overseas corporation, branch of a public organization or listed company, dispatched to head office in Korea for training or teaching professional knowledge / technology |

|

D-7‑91 |

Intra-Company Transferee (by FTA) |

Intracorporate transfer under an FTA |

|

D-7‑92 |

Contractual Service Supplier (by FTA) |

An employee affiliated with a company of in an FTA contract dispatched to Korea for providing or supporting contract services |

|

D-8‑1 |

Incorporated Enterprise |

A required professional to work in manufacturing·technical or management·administration at a foreign-invested Korean corporation* |

|

D-8‑2 |

Business Venture |

A person who has established a venture business pursuant to the Act on Special Measures for the Promotion of Venture Business or who has been confirmed as a preliminary venture business |

|

D-8‑91 |

FTA transferee |

Intra-company transferee according to FTA |

|

D-8‑3 |

Unincorporated Enterprise |

Required professional to engage in the management of foreign-invested enterprises or in the fields of production and technology* |

|

D-9‑1 |

International Trade Visa |

Traders with granted trader identification number, ex-foreign students with retail experience, trained traders |

|

D-9‑2 |

Maintenance |

Responsible of installation, operation and repair of export facility machinery |

|

D-9‑3 |

Shipbuilding supervisor |

Shipbuilding supervisor sent by client of shipyard |

|

D-9‑4 |

Manager |

Company management and commercial operators |

|

D-9‑5 |

Ex-student |

Trade management who was student. Individual firm. Korean degree and >300M KRW investment required |

Note: *in accordance with the Foreign Investment Promotion Act. The foreign investment must be more than KRW 100m.

Source: OECD Secretariat analysis of Korean legislation.

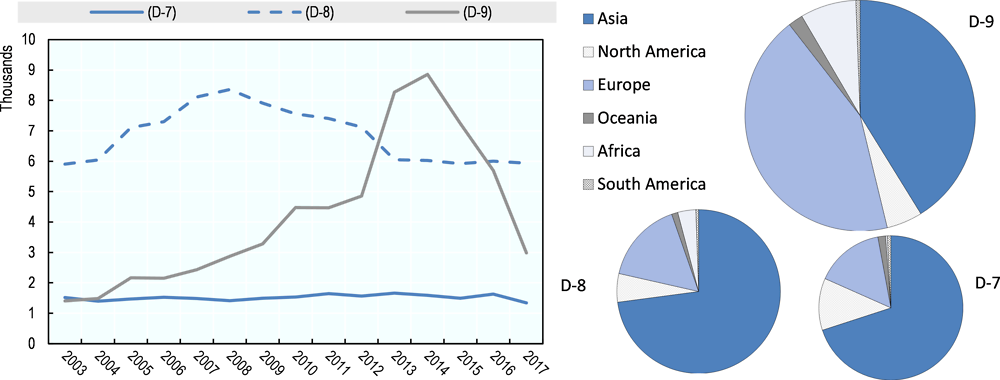

There are a little over 1 300 people with a D-7 visa in Korea, a figure which has been steady for more than a decade (Figure 4.6). About one in three ICTs with a D‑7 is from China, and 22% and 23% each from India and Japan. Other OECD countries besides Japan comprise most of the remainder.

D-8 visas, with about 6 000 foreign residents, are notable for the predominance of Japanese (47%), followed by Chinese (22%) and nationals of other OECD countries outside Asia (20%), but also Pakistan (6%) and India (4%).

D-9 visas are mostly granted to foreign nationals representing clients of Korean shipyards (in 2017, the D-9‑3 visa comprised about 82% of all D-9 visas), so that the number varies according to the contracts underway in Korean shipyards. The number sharply fell from its peak in 2014 to below 3 000 in 2017. Top countries in 2017 were Norway, Great Britain and France. Overall, OECD countries comprised 49% of the foreigners holding D-9 visas in 2017.

One notable aspect of D visa holders in Korea is that they are overwhelmingly men: more than 85% of the visa-holders in each of the D-7, D-8 and D-9 categories are men.

Figure 4.6. Intracorporate transfers are more numerous than skilled workers

Source: Korea Immigration Statistics.

The D-7 through D-9 visas can be renewed indefinitely. This makes the D-7 visa, in particular, unusual in international comparison, as most intra-corporate transfers are subject to a maximum stay followed by a cool-down period or mandatory absence from the country (see Box 3.12). At the same time, it opens opportunities for intra-corporate transfers to become familiar with the country and potentially shift to local hire with a view to remain.

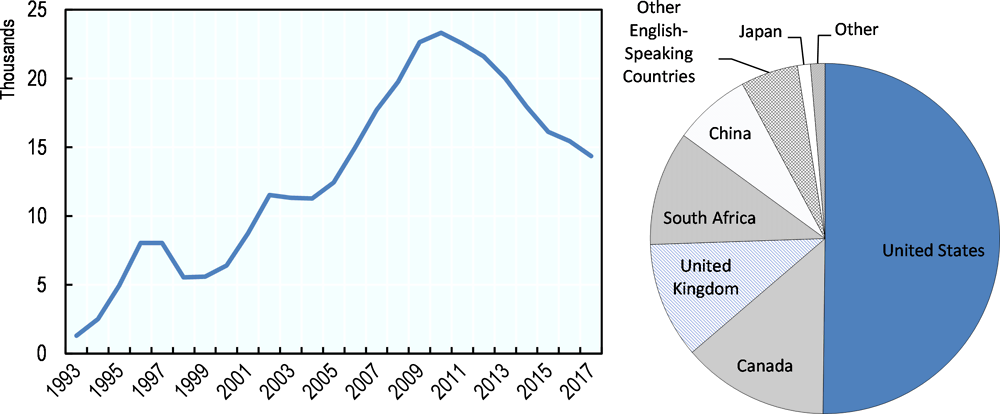

Foreign Language Teachers

The educational system in Korea has a particular interest in English language education. As English proficiency is one of the main criteria for assessing the ability of students to enter top universities or hiring after graduation, a large number of Korean parents pay to offer private English language lessons to their children. In 2017, half of middle school students and 30% of high school students were taking private English language lessons1. Korea has the highest expenditures on supplementary private education among the OECD countries. This specific demand led to a creation of E-2 visa for Foreign Language Instructor in 1993. Issued to native English speakers who wants to teach English in Korea and meet the following requirements: a 4-year-university degree from English-speaking countries (the US, the UK, Canada, South Africa, New Zealand, Australia and Ireland) and holding the nationality of one of these countries. The number of E‑2 visa holders peaked in 2011 and has been falling since then (Figure 4.7). The E‑2 visa is the only visa among skilled work visas where more than half of recipients (55.2% in 2017) are women. For other skilled E visas (excluding E-6), only 38.4% were women in 2017.2

Exceptions have begun to be made for nationals of other countries. Indian nationals who are qualified as teachers benefit under the India-Korea Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement (CEPA) which came into effect in 2010. University graduates from India who majored in English and acquired a teaching certificate can apply for the E-2 permit to teach English in Korea for a year. The number using this visa, however, has been very limited.

Figure 4.7. The number of language teachers is declining

Source: Korea Immigration Service, 2017.

Since native speakers are a top selling point for private language institutes, they compete to hire native speaking teachers. Public schools also compete by offering English classes taught by a native speaker. About one-fourth of language teachers in Korea are employed by public schools. Salaries are not particularly elevated relative to other qualified employment in Korea: the wage level of the language teachers varies between KRW 1.5 million and KRW 3 million (about USD 1 500 to 3 000) depending on their experience and the type of workplace. Low-wage and underpaid English language teachers have been a problem in the unregulated sector of language schools; in 2013, the Ministry of Justice set a minimum wage for acquiring the E-2 visa at KRW 1.5 million to prevent underpaid foreign language teachers and reduce the number of undeclared language teachers. This salary requirement, along with the declining demand for English-language instruction as there are fewer young people in the school-age cohort, has led to a decline since 2012.

Japan is the only other OECD country with a similar work visa, and has a smaller number of English teachers from abroad at around 7 000 permit holders, including language teachers at public schools with Instructor visa and teachers at private institute with Specialist in Humanities / International Services visa.

There are several programmes under the E-2 scheme. The English Program in Korea (EPIK) helps improve English proficiency of both students and teachers in Korean schools by recruiting native speakers. The NIIED's Teach and Learn in Korea (TaLK) scholarship programme launched in 2008 is designed for university graduates to participate in six months to one year of working partnerships with the Korean university to prepare and engage in the after-school English programmes at the elementary schools.

The only other language allowed under the visa is Chinese; there were more than 1 000 Chinese teachers in Korea in 2017. The Chinese Program in Korea (CPIK) invites Chinese teachers with a university degree and a teaching certificate. CPIK teachers can stay up to two years to give Chinese lessons.

Most E-2 teachers do not settle in Korea. In-country status changes are allowed, although rare. The permit is not designed to bring in talent; E-2 permit holders are granted a stay a month longer than the length of contract. Those who require additional time to change jobs or sectors and stay in Korea can also apply for a job search visa (D-10‑1).

Global talent attraction initiatives

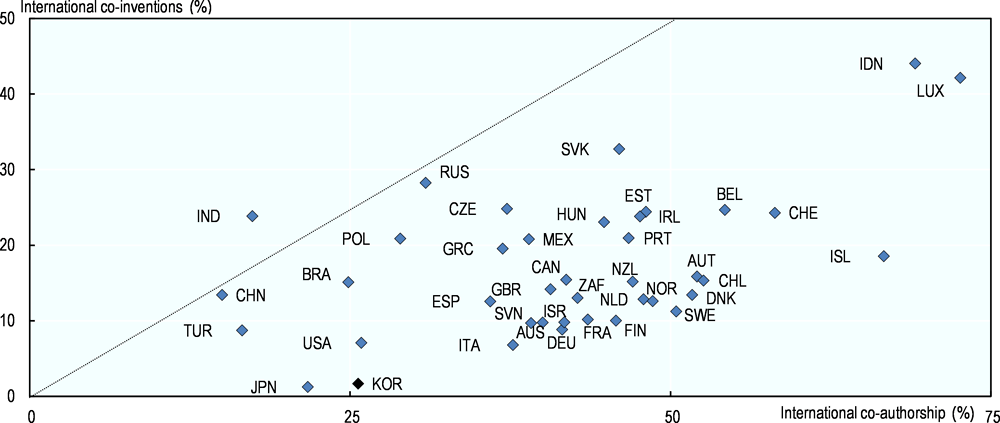

Among the policy priorities in the migration area is attraction of global talent, particularly in research and innovation. This is a response to the fact that, while Korea invests heavily in R&D, its integration into global innovation networks – as measured by levels of international co-authorship and co-patenting – are among the lowest in the OECD (Figure 4.8). To address this, Korea has launched a wide range of different programmes to attract international talent.

Figure 4.8. Korea lags behind in international collaboration in science and innovation

Note: International co-authorship of scientific publications is measured in terms of the share of articles featuring authors affiliated with foreign institutions (from a different country or economy) in total articles produced by domestic institutions. A scientific document is deemed to involve an international collaboration if institutions from different countries or economies are present in the list of affiliations reported by single or multiple authors. Estimates are based on whole counts from information contained in the Scopus database. International co-inventions are measured as the share of patents with at least one co-inventor located abroad in total patents invented domestically. Data refer to IP5 patent families with members filed at the EPO or the USPTO, by first filing date and according to the inventor’s residence using whole counts.

Source: OECD, STI Micro-data Lab: Intellectual Property Database, http://oe.cd/ipstats, June 2015; and OECD and SCImago Research Group (CSIC), Compendium of Bibliometric Science Indicators 2014, http://oe.cd/scientometrics.

The points-based system for skilled foreigners

Korea offers fast-track permanent residence for qualifying high skilled foreigners. Under a points-based system (PBS) it evaluates professionals who have been living in Korea for at least a year under a different permit. Points are given by checking academic qualifications, Korean language proficiency, income and age. If eligible, they are entitled to residence status (F-2). Obtaining F-2 status allows full labour market access as well as permits for family members. Permanent residence status is allowed after three years of having F-2 status, rather than five years as would normally be required. About 800 people received this status in the first 18 months of application.

Table 4.2 Age and education count for status change to permanent resident

Points grid for status change to F-2‑7 Permanent Residence Permit.

|

Category |

Criteria |

Points Available |

Description |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Standardized criteria |

Age |

15‑25 |

Increasing from 20 for age 18‑24 to 25 for age 30‑34, decreasing to 15 points for more than 51 years old |

|

Education |

15‑35 |

PhD level: 33 Masters: 30 Bachelors: 26 Associate: 23 Extra 2 for multiple degrees or degree in science or engineering.15 for high school. |

|

|

Korean language ability |

10‑20 |

10 for the lowest level, 2 points for each additional level up to 20 points for level 6 |

|

|

Current income |

1‑10 |

1 point for less than 20m KRW annual income. 1 point for each 10m KRW up to 100m (10 points) |

|

|

Extra points |

Million KRW of income tax payments |

1‑5 |

1 point for 1‑2m KRW in tax payments, one additional point for each million up to 5. |

|

Korean study |

1‑5 |

1 point for language study, 2‑5 points for degree from associate to PhD |

|

|

Volunteer activity in Korea |

1‑5 |

1 point for 1‑2 year, 3 points for 2‑3 years, 5 points for 3+ years. |

|

|

Overseas professional work experience |

1‑5 |

1 point for 1‑2 year, 3 points for 2‑3 years, 5 points for 3+ years. |

|

|

Penalties for violation of Korean laws |

By the applicant |

-1 to -3 |

depending on number of offences (1‑2 or more) and total amount of fines imposed |

|

By a family member or (sponsored) invitee |

-1 |

for multiple offences or fines over 1m KRW |

|

|

Sponsored family member overstay by >3 months |

-1 |

|

|

|

Total |

Must score 80 out of possible 120 |

|

Source: Ministry of Justice.

The PBS in Korea privileges education more than other criteria, offering up to 35 points, or 40 points for study in Korea; this is half the points necessary to qualify for the threshold. Language and age appear to be the criteria with the most weight following education. However, the ranking also provides a minimum score for a number of variables, the real weight of age, for example, is reduced, since all applicants score at least 15 points, converting the real minimum score to 65 instead of 80 for calculating the share contributed by each factor. While the grid requires some top-scoring in basic categories, a 30-year old graduate, with a bachelor degree from a Korean institute, a medium level of Korean knowledge and a job paying the median salary would not qualify for the F-2 permit.

Korea joins a number of other OECD countries in using a PBS for high skilled migrants. Since introduction in Canada in 1967, PBSs have been used as an instrument to manage selective migration policy. All PBS assigns points per migrant characteristics (e.g. Master’s degree, three years of professional experience) grouped in factors (e.g. education, professional experience). PBS are either pass/fail or ranked: in the first, a pass score determines eligibility, while in the second total points are used to prioritise admission.

PBSs are meant to be flexible, as the point allocation can be easily changed, and transparent, as applicant score and admission chances are easy to calculate. They also signal that authorities have control over migration inflows and that only migrants with certain skills are admitted to the country.

Table 4.3. Points-based selection systems tend to focus on highly-skilled workers

PBS in different OECD countries, by year of introduction and target group.

|

Country (year of introduction of PBS) |

Scheme |

Target group |

|---|---|---|

|

Canada (1967) |

Federal Skilled Worker Program; Canadian Experience Class; Federal Skilled Trade; Provincial Nominee Programme (optional) |

Skilled migrants |

|

Australia (1979) |

Skilled Independent visa (subclass 189); Skilled Nominated visa (subclass 190); Skilled regional visa (subclass 489) |

Skilled migrants |

|

Business Innovation and Investment Visa (subclass 188) T |

Investors and entrepreneurs |

|

|

New Zealand (1991) |

Skilled Migrant Category |

Skilled migrants |

|

Investor 2 |

Investors |

|

|

Czech Republic (2003‑2009) |

Selection of Qualified Foreign Workers |

Highly skilled workers |

|

Denmark (2007‑2016) |

Green Card |

Highly skilled workers |

|

United Kingdom (2008) |

Tier 2 - general |

Skilled workers |

|

Netherlands (2008) |

Self-employed person |

Entrepreneurs |

|

Korea (2010, 2011, 2015) |

Long-term residence (F-2 visa) |

Migrants who have resided in Korea for one year and want to apply to the long-term residence |

|

Employment Permit System (E-9 visa) |

Low skilled workers |

|

|

|

Start-Up visa (D-8‑4) |

Start-up entrepreneurs |

|

Austria (2011) |

Red-and-White Card |

Highly skilled migrants |

|

Japan (2012) |

Preferential treatment for highly skilled foreign professionals |

Highly skilled workers |

|

Germany (2016) |

PuMa (pilot project) only in the Land of Baden-Württemberg |

Medium skilled workers with a profession which is not in the shortage list |

|

Turkey (2017) |

Turquoise Card |

Highly skilled workers and investors |

Source: OECD Secretariat.

PBSs have a twofold objective: to improve selection and to improve case management. PBSs improve selection by weighting factors differently, by equally considering different profiles, and by introducing factors with multiple dimensions. Case management is an issue when the number of applications exceeds the number of available places or the administrate capacity. In either case, authorities may want to prioritise some applications over others. A PBS, thanks to its ranking feature, can be used to this end if applications scoring more points are processed earlier.

Korea uses the PBS exclusively for selection, rather than case management; indeed, there is no backlog of high-skilled workers to prioritise. In this, its system is similar to that of European countries and Japan.

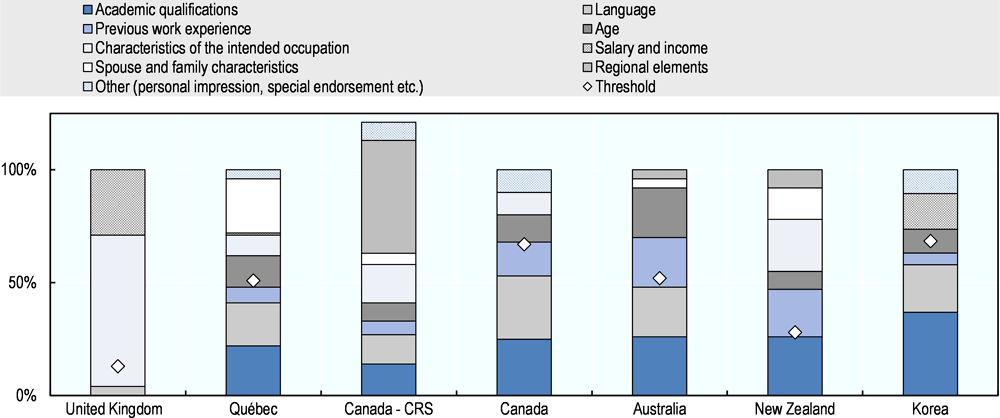

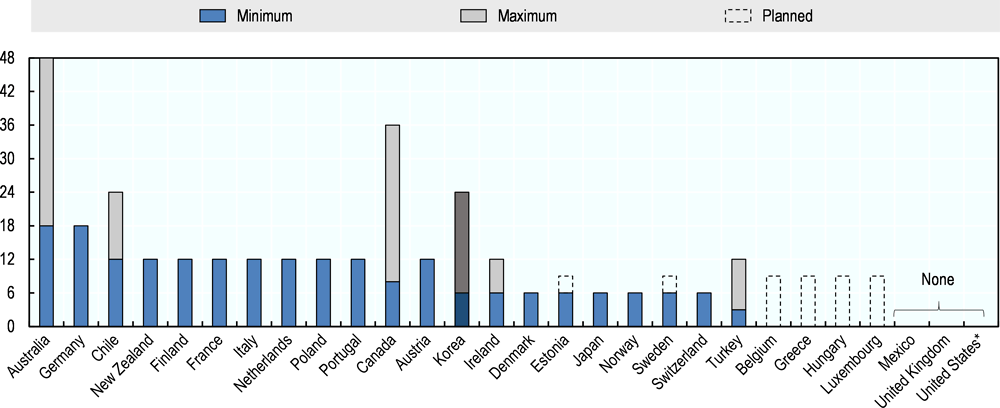

Compared with points-based systems used to select permanent economic migrants in other OECD countries, Korea’s F-2 PBS relies more heavily on education, and much less on the characteristics of the occupation (Figure 4.9). The occupation of the applicant does not affect points ranking.

Figure 4.9. The F-2 Points-Based System relies more on education and less on occupation

Source: OECD Secretariat.

The F-2 under the PBS is not available to applicants who are not already resident in Korea. Family members of F-2 PBS visa holders are allowed to come to Korea (as F-1 visa holders), but their employment is restricted, and they must apply for separate work authorisation.

In OECD countries using PBS in selection, PBS criteria and weights are regularly reviewed and reweighted in light of evaluation of the outcomes of recipients, in order to improve the ability of the system to select candidates who are able to maintain their employment over the long term. An adequate evaluation framework needs to be in place to adjust and refine the PBS. This appears especially important for Korea, which weights academic qualifications very highly. Other OECD countries have noted that academic qualifications, in the absence of a high degree of language skills, have not assured long-term employability.

Researchers and R&D programmes

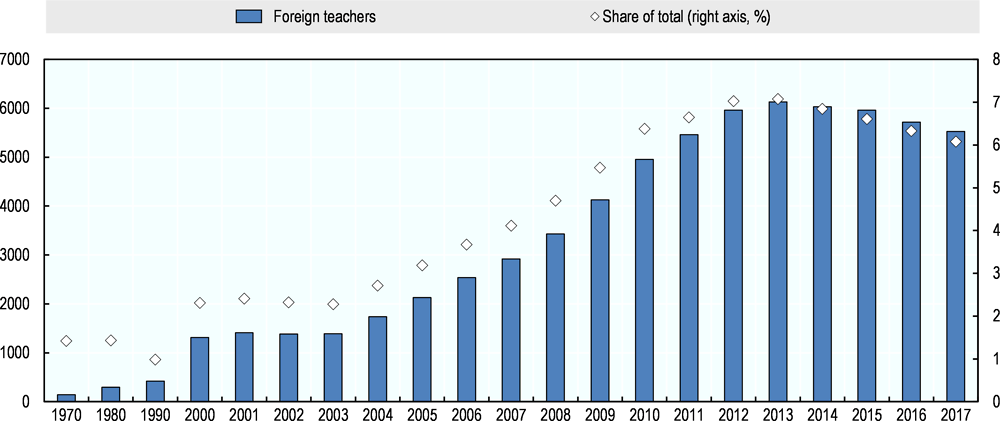

Most of the effort in the field of research has focused on researchers and academics for university and research centre staff. The objective of internationalisation of the higher education sector is a long-standing one; in 2002, the objective was set to increase the share of foreign academic staff in higher education to 30% (Kim, 2005[3]). The number of foreign professors increased along with the expansion of the higher education sector but has been in decline since 2012 (Figure 4.10). The number of foreign faculty has also been declining as a share of total faculty (now about 6.3%). Institutional barriers to inclusion remain strong (Kim, 2016[4]).

Figure 4.10. The number of foreign professors has started to decline

Source: Ministry of Education.

To attract highly skilled, one such programme was the World Class University (WCU) program, which ran from 2008 to 2012, with the objective of attracting outstanding foreign talent. The programme was funded (KRW 825 bn, or about USD 620M) by the Ministry of Education, Science, and Technology (MEST), and run by the National Research Foundation. The project was divided into three types: establishing departments with hired foreign scholars; hiring individual foreign scholars to existing departments; and attracting world renowned scholars (Um, 2012[5]). The programme attracted more than 1 000 academic applicants (Noh, 2014[6]). By early 2011, more than 340 recruits had begun. The costly programme can be evaluated positively in terms of its impact on the participating universities. However, after the World Class University Programme expired, only 14% of foreign participants remained in Korea.

In January 2014, the Korean government introduced a new plan to attract more global talents, with the aim of increasing the number of the high-skilled foreigners by nearly 50% by 2020. This initiative was launched to strengthen the global competitiveness and the R&D capabilities. The plan aimed to increase the number from 25 000 in 2012 to 36 650 by 2017, reaching 7 500 E-1 and E-3 visas. The increase over the period was only half what was necessary, and the target is unmet.

As Korea has endeavoured to develop itself into a knowledge-based economy, several programmes to bring more foreign experts already existed, such as Brain Korea, which dates back to 1999, when the first initiative included a component of international mobility to bring more than 400 scholars in the first five years. Although the number of foreign experts has grown since 2007, most of those visiting experts and students have left the country soon after the programme or scholarship ended.

Responding to these outcomes, the government decided to involve and allocate specific tasks to each Ministry in order to attract more foreign labour primarily for long-term. The plan distinguishes foreign workers into three different categories: researchers (scholars); workers in SMEs including start-ups; and students.

To attract researchers and scholars, the Ministry of Education and Ministry of Science, ICT and Future Planning collaborate to reinforce the infrastructure for research. The Ministry of Science programme, Korea Research Fellowship, offers scholarships and additional supports for maximum five years for scholars who wish to stay to work in companies or institutions. The BK21 Plus programme will be used to approach the top scholars in the world. Research collaboration with the EU began in 2014 exchanging 40 researchers per year.

Another project to absorb more intellectuals to Korea is Brain Return 500 Project, which began in 2012, promoted by the Ministry of Education, Science and Technology (MEST). It aimed to attract 500 top scientists and young researchers in the coming years. Funding for research is provided; up to USD 500 000 annually for two years, for senior scientists, and up to USD 300 000 annually for three years. Extensions of funding can be provided – one year for the first group, and two years for the second. By March 2014, it had attracted almost 100 scientists, of which 1/3 were Korean nationals and the remainder foreigners.

To import more high-skilled workers in SMEs, the Ministry of Science and Ministry of Trade, Industry and Energy focused on recruiting and a better environment for start-ups. Contact Korea supports active recruitment in SMEs; job fairs have been held in Korea and abroad. Ministries also run numerous contests to give opportunities and support the start-ups.

Lastly, the Ministry of Education and Ministry of Science offers various programmes and scholarships to bring outstanding students around the world. The Ministry of Education introduced “Study Korea 2020”, to invite outstanding students in the national strategy. The Korea Research Fellowship programme targets only researchers and talented students. Increasing exchanges between local universities and foreign universities will be encouraged. The Ministry will offer counselling services for the foreign students in Korea to support their stay.

For researchers and high-skilled foreigners to make long-term commitments in Korea, however, their engagement in Korean society would have to increase. On the side of foreign researchers, voluntary classes and counselling services to support their journey to adapt and engage more in the community could help. Only 13% of the foreign researchers in Korea in 2016 were women, suggesting that there are also gender issues to address in this channel. A further obstacle is the difficulty of acceptance in Korean university culture, and changes here can only occur on the Korean side (Kim, 2005[3]).

Non-tertiary technical personnel

In Korea, attempts are being made to encourage students in tertiary education to leave university and enrol in university-offered non-tertiary technical vocational certification programmes, in order to work in skilled jobs in “root industries” (SMEs in basic manufacturing). These firms require technical skills but face labour shortages, as Korean students have been reluctant to take the technical training and to work in these SMEs. In 2015, the Ministry of Trade, Industry and Energy (in collaboration with the Ministry of Justice) launched a pilot project to bring foreign students into these jobs. Three participating universities have created non-tertiary technical skills institutes, “Training Institutes for Foreign Engineers in Human Resources of the Root Industry”. The pilot recruited students from university programmes into short-term training courses (less than two years) for professional certification, e.g., as industrial welding engineers. Courses were organised with a simplified Korean, for easier understanding, and offered only to these foreign students. In addition, the pilot provided subsidised workplace-specific Korean language instruction and progressive subsidies for studying for the TOPIK exam. Companies were identified who were ready to hire students upon programme completion. The pilot was designed for up to 100 students; 23 were admitted in the first group; by 2017, eight universities were running vocational certification programmes under this pilot with 123 students.

The pilot is based on the existing E-7 visa, for which skilled manufacturing workers are already allowed, and provisions to transfer from the student visa to the E-7 visa at graduation from the programme. However, the E-7 visa requires, for skilled industrial workers without higher-education qualifications, five years of experience. In 2017, this requirement was exempted for graduates of the Training Institutes, allowing them to change status. Similar measures were applied in 2016 to E-9 workers offered technical jobs in “root industry” SMEs, who are now allowed to change status.

Non-migration policy challenges to international recruitment and responses

Despite the introduction of a number of programmes to attract talent from abroad, it is difficult to expect large inflows or their long-term stay. They are likely to confront cultural barriers, language problems and higher costs of private education for children. A 2014 survey by the Hyundai Research Institute – albeit small-scale, with about 115 interviewees – found that work-life balance was the main complaint (Jeon, 2014[7]). Half were certain they wished to leave Korea at the end of their contract, with the main reason cited “corporate culture and values”. The sample was mostly male (68%), single (50%) or married without children (20%) and young (36% under age 30, 46% between 30 and 39). All those with children cited their children’s education as a difficulty in settling.

The challenges faced by international scientists and engineers to migrate to, or remain in, Korea are similar to those facing Korean expatriate scientists and engineers. These include important differences in wages and working conditions, gender disparity in education and employment, and a highly competitive job market (Song and Song, 2015[8]). Song and Song further point to the issue of children’s education: many educated Koreans prefer to enrol their children in education abroad rather than the Korean system, with foreigners even more hesitant to put their children in Korean schools, despite their outstanding record.

Kraeh et al. (2015[9]) identify a number of factors which affect retention of foreign professionals in Korean firms, indicating the long working hours, communication culture, strict hierarchies, and difficulties in integrating. These factors cannot be addressed by migration policy but require a cultural change (Herting, 2016[10]). Similarly, Shin and Choi (2015[11]) point to a number of factors which hinder skilled migration, including a hierarchical and gendered work culture, concerns about the perception and treatment of foreigners in Korea, and closed social networks.

Some local governments have taken steps to support the foreign resident population. Two noteworthy approaches are in Ansan, a city with a relatively large and long-standing foreign population, and the Seoul Global Center.3 Both centres are run by the municipality, and provide support for foreign residents of all kinds. The Seoul Global Centre, on the other hand, was launched by the municipality of Seoul in 2008 as a multi-lingual, comprehensive support centre. It provides free counseling (in almost a dozen languages) on daily life, with a number of services related to employment (job fair, dispute resolution). The centre also provides language training. Experts provide counselling on issues faced by foreigners living in Seoul in ten different languages on subjects such as starting a business, legal disputes, labour disputes and real estate transactions among others. The Seoul Centre offers support for entrepreneurship (starting a business) and even a business incubator for start-ups, offering office space and mentoring for the first year. The centre is funded by the municipality, but also makes use of volunteers.

Highly qualified talent is also brought to Korea by large Korean companies with global presence or commercial relations, such as the large technology and shipbuilding firms. However, large firms in Korea make sparing use of foreign workers. According to the 2016 Foreigners Labour Force Survey, large firms (more than 300 employees) accounted for just 3% of employment of foreigners in Korea, compared with 13.6% of Korean workers.

A number of factors need to be in place beyond a favourable permit regime to attract foreign talent: career opportunities for the skilled worker and any accompanying spouse, education for any children of the migrant, and the possibility of a community. In the capital region, a sufficient network of support has developed so that large firms can rely on the labour market and existing international schools. In other parts of Korea, large firms employing large numbers of foreign skilled workers have had to support the creation of expatriate compounds, social centres, international schools, newsletters and other elements to ensure that foreign talent is willing to accept employment; this is the case in the shipbuilding centre of Ulsan, for example. This model of expatriate compounds, where international skilled workers are segregated in housing, education and civic life, hinders long-term retention.

Regarding opportunities for spouses, according to the 2016 Foreigners Labour Force Survey, 83% of the foreign employees of large firms were men, a wide gender gap suggesting that there are many spouses of qualified workers. Without job opportunities for spouses, it is unlikely that married couples will wish to settle in Korea; indeed, employed spouses increase the retention rate for skilled immigrants (OECD, 2014[12]).

Korea has also offered foreign high-skilled employees significant tax breaks, although these are gradually being withdrawn (Box 4.3).

Box 4.3. Favourable tax treatment

Starting in January 2003, fiscal incentives for highly skilled immigrants included tax-free allowances of up 40% of salary to cover cost of living, housing, home leave and education. For certain foreigners - employed under a tax-exempt technology inducement contract, or a foreign technician with experience in certain industries – the salary was made tax-exempt for up to five years (OECD, 2005[13]). The general exemption was later reduced to 30% and eliminated in 2010. For technicians and engineers providing services to a Korean company, there is a 50% income tax exemption on salary for the first two years of employment (this exemption will be withdrawn in 2019).

Foreign employees working in Korea have been eligible to elect to pay a flat income tax rate on earned income in Korea, rather than the progressive rate to which Koreans are subject (which goes up to 40%). This flat rate on earned income in Korea has varied in recent years, rising from 15.5% prior to 2013, to 17.5% in 2013, 18.7% in 2015 and 20.9% in 2017. At these levels, the flat income tax becomes attractive for high-income foreigners, currently those earning more than USD 100 000 annually. The flat rate can be applied for up to five years from arrival. The government has announced that it will withdraw this favourable treatment for foreigners arriving from 2019, except for those in certain firms.

Such tax incentives are unusual to offer to immigrants, except in very high tax countries to eliminate strong disincentives for talents to migrate (OECD, 2011[14]). It is not clear whether these personal tax incentives have influenced the attractiveness of Korea for highly-compensated foreign professionals, since the numbers remain relatively low. More direct policy tools such as supporting educational opportunities for children and ensuring equal access to housing may be more effective. Furthermore, tax concessions create equity concerns by treating differently high-skilled and less-skilled workers, and often foreign and domestic workers.

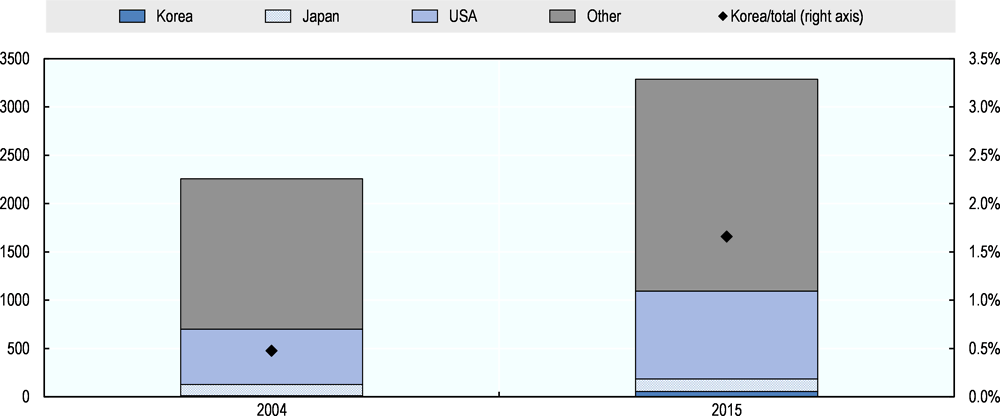

International students

International study is one of the main drivers of migration movements, the globalisation of higher education, and circulation of higher educated. In many OECD countries, a large share of higher skill migrants are former international students. The number of international students studying in OECD countries increased by more than one third between 2004 and 2015 (Figure 4.11). Korea’s share of this growing international market rose from 0.5% to 1.7% over the same decade.

Figure 4.11. Korea has a small but growing share of global international student flows

Note: Dates refer to the academic years 2003/04 and 2014/15. For notes see http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/migr_outlook-2017-table16-en.

Source: OECD, Education at a glance database.

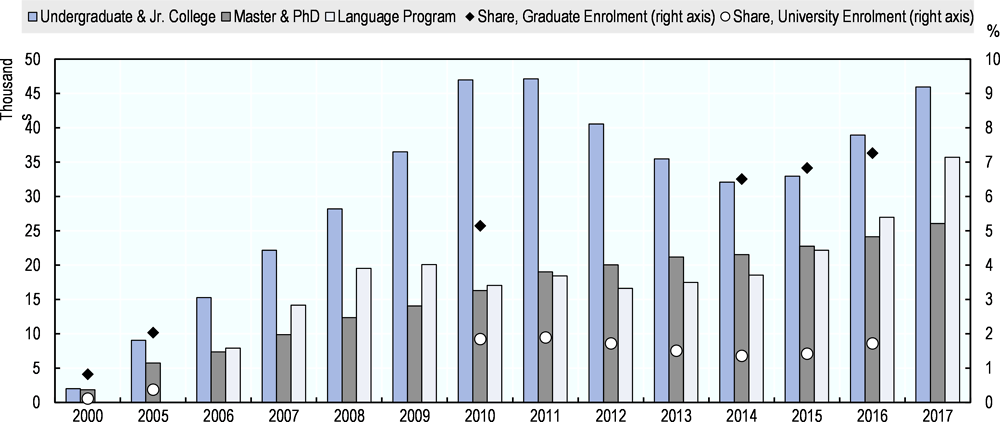

Korea has seen a rapid expansion of its international student population in the past decade, although this fell from 2010 to 2014, and has been increasing since (Figure 4.12). The number stood at 123 900 in 2017, of which 72 000 were in degree programmes, and 35 700 in language programmes. Foreign students comprised almost 2% of total enrolment in universities, and almost 8% of total enrolment in Master’s level and PhD programmes.

Increasing the number of foreign students has been a major policy goal for some time. “Study Korea”, a policy programme for 2005‑12 launched in 2004, set an objective of bringing foreign student enrolment to 50 000 by 2010. One of the main outputs during the programme was the creation of a multilingual website studyinkorea.go.kr centralising information on admissions, scholarships and regulations. The objective of the first “Study Korea” was exceeded, and the next phase, “Study Korea 2020” was launched in 2011 to further increase the number of international students to 200 000 in 2020 (from 90 000 in 2011). This objective was set in order to internationalise its higher education sector, but also to support universities in the face of falling enrolment. High enrolment levels and shrinking youth cohorts mean that Korea is expected to have more university capacity than demand starting in 2018, making foreign enrolment an attractive means to compensate for fewer national students, and a means for universities to maintain their student body. Foreign student enrolment is not a component of the quality index used by the Ministry of Education to rate universities. However, international rankings such as the THE and the QS rankings incorporate foreign student enrolment, giving universities an incentive to increase enrolment.4

The 2012 programme included extra support for international students during their studies and their transition to employment, improving international recruitment into universities, and expanding scholarships. In addition, the government announced facilitated pathways to stay on in Korea. In 2015, with international student numbers stalled, the target date was moved to 2023, with an objective of 5% of total enrolment. In 2015, subsidies for foreign students amounted to KRW 800 bn total (about USD 730m); the Ministry of Education plans to almost double this amount by 2020. Further initiatives include support centres for foreign students, a simpler process to transfer from language courses to university. For students in certain fields (engineering, technology and natural science), naturalisation will be possible after only two years employment as university professors or researchers, rather than five as for other categories, and certain professional experience may also qualify.

Figure 4.12. International enrolment has varied

Source: Ministry of Education.

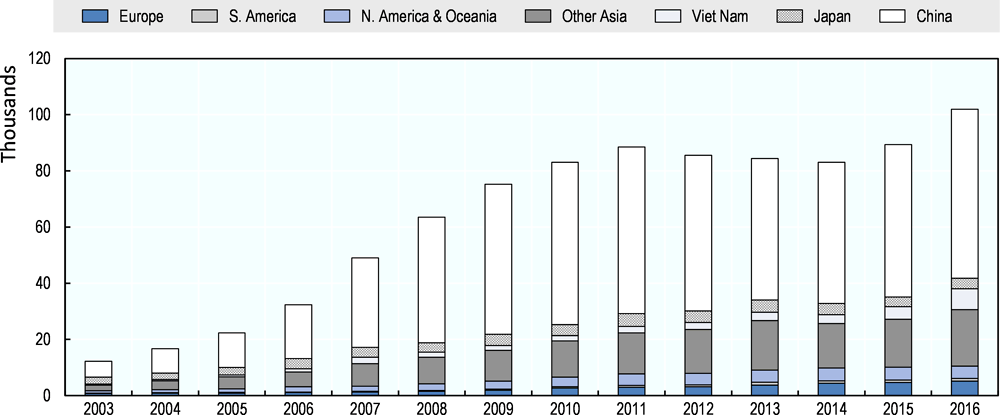

In terms of national origin, most international students are from China (Figure 4.13). The decline in the number of Chinese students from 2011 to 2014, related to stricter review of admission criteria and of actual participation, explains the fall in overall student numbers. As Chinese enrolment picked up again in 2015, total students numbers increased. Most of the remaining international students are from other Asian countries, led by Viet Nam (7.2% of the total in 2016). Historically, most Asian students came from Japan and Taipei,China. Those from other Asian countries have increased more sharply; notably, Mongolia accounted for 4.3% of total enrolment in 2016. Half of Vietnamese and Mongolian foreign students were enrolled in non-degree language courses in 2016, compared with 33% of Japanese students, 25% of Chinese students and 18% for those from all other countries.

Figure 4.13. More than half of foreign students come from China

Note: Korean-Chinese students are not included.

Source: Ministry of Education.

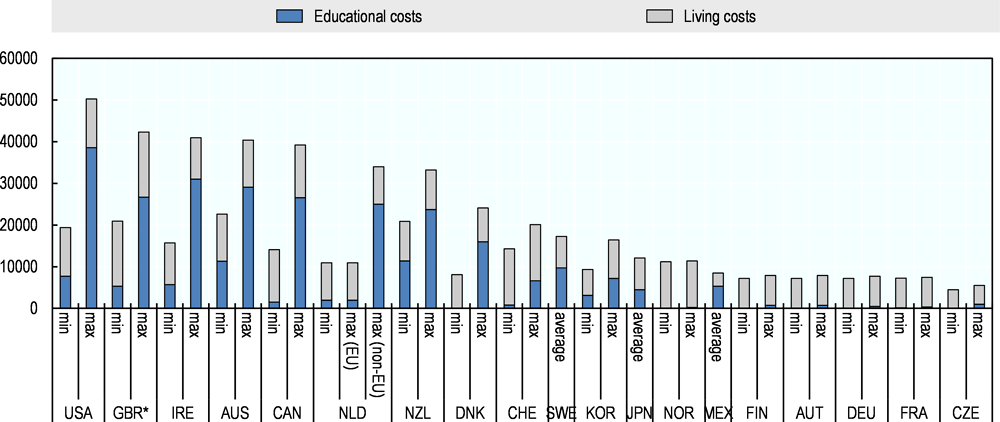

Korea is a relatively competitive destination for international students in terms of cost (Figure 4.14), although international students in Korean-language courses will have to achieve a minimum level of Korean to study (TOPIK level 3) prior to study. Scholarships are available: the Global Korea Scholarship now funds almost 900 new students annually, primarily graduate students. Universities fund about three times as many scholarships. About 85% of students pay their own fees, so cost is an important consideration in promoting Korea as a destination. The share and the absolute number of foreign students with a scholarship has fallen from 2011 to 2016, despite government efforts to increase the scholarships offered to international students.

Figure 4.14. Korea is a relatively inexpensive destination for international students

Note: * Excludes Scotland, min refers to lower bound of educational costs, max refers to an upper bound of educational costs. For the Netherlands the maximum possible fee refers to international students from non-EU countries.

Source: OECD (2013), Education at a Glance 2013: OECD Indicators, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/eag-2013-en; Usher, A. and J. Medow (2010), “Global Higher Education Rankings 2010. Affordability and Accessibility in Comparative Perspective, Higher Education Strategy Associates”, Toronto; and national governmental and university websites. For the Netherlands the source is Nuffic. For Korea, the source is Study in Korea.

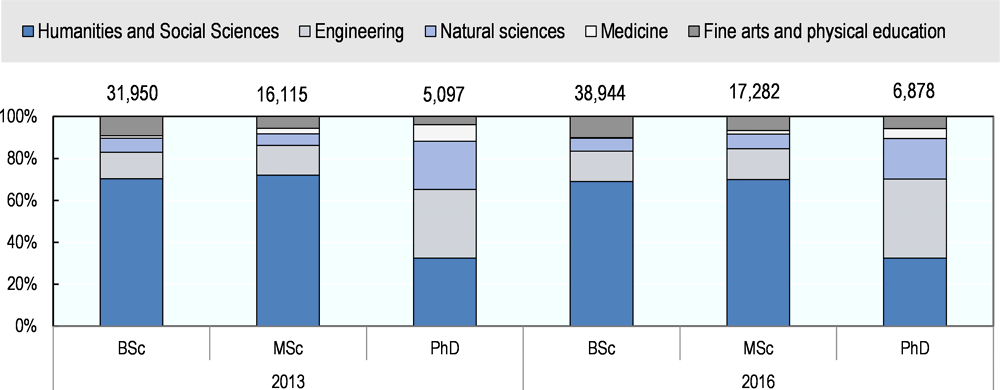

Field of study of foreign students varies according to the level of study (Figure 4.15). Undergraduates are mostly enrolled in social sciences and humanities (two-thirds of these in social sciences). While there are fewer graduate students, a much larger share of them are in engineering (38%) and natural sciences (19%). About half of international students are in Seoul or other major metropolitan areas, while 47% are in provincial areas. There are few differences in field of study between those in major metropolitan universities and provincial universities.

Figure 4.15. Most undergraduates study liberal arts, most graduates engineering and natural sciences

Note: Students in the joint MSc-PhD programs were aggregated into PhD category. Education is included in the “Humanities and Social Sciences” programme.

Source: KEDI international students annual statistics.

With the pressure to maintain international enrolment, there has been the risk that standards were relaxed for admission and international students accepted even if they did not meet requirements. The general language standard for international students was lowered from TOPIK 3 to TOPIK 2 in 2018. While scholarship students are subject to a high Korean-language requirement (TOPIK 5 for admission, or TOPIK 3 after one year of language education).5 To deal with this, the government decided in 2011 to recognise certain higher education institutions for excellent selection and management of foreign students, easing the document requirements for foreign students enrolling in these universities, the International Education Quality Assurance System (IQEAS) (Table 4.4). IQEAS takes into account the share of international students who overstay or otherwise fail to comply with permit conditions, or who abandon the programme. In addition, institutions are expected to meet basic requirements.

In addition to the factors shown in Table 4.4, IQEAS is also based on a subjective evaluation of the capacity of the institution to support international students. This is based on a number of factors, reviewing: international vision and characterization; support for international students’ adaptation and study; and the actual academic achievement of international students.

For institutions with IQEAS, more proof of actual competence, language skills and prior education is required before a student visa will be issued. The introduction of IQEAS is associated with the decline in student enrolment, before numbers resumed their upward trend.

Table 4.4. Korea ranks trustworthy universities

International Education Quality Assurance System (IQEAS) components.

|

Classification |

Criteria |

Standard |

University |

Community College |

Graduate College |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Compulsory criteria |

Rate of undocumented foreign students |

< 2 to 4% |

at least 1 criterion |

||

|

Foreign student dropout rate |

< 6% |

||||

|

Conditional criteria |

International student tuition burden ratio |

80%+ |

at least 3 of 4 criteria |

at least 3 of 4 criteria |

at least 2 of 3 criteria |

|

Health insurance purchase rate |

85%+ |

||||

|

Linguistic ability (Kor. /Eng.) |

30%+ |

||||

|

Rate of dormitories provided to freshmen |

25%+ |

||||

Note: Undocumented foreign student rate is calculated based on total foreign enrolment; 4% is the threshold for smaller enrolments (<100) and 2% for larger (>500).

Source: NIIED.

This means of ensuring compliance is similar to that used in several other OECD countries, such as the United Kingdom, where “trusted sponsors” are able to admit students, while other institutions are granted sponsorship rights on a probationary basis. An alternative method is to develop an electronic monitoring and compliance platform, such as SEVIS in the United States, requiring universities to verify enrolment and performance of international students. Korea has a Foreign Student Information Management System (FIMS), which contains information on the identity of foreign students, whether they have a state scholarship, and their current enrolment status. FIMS is managed by NIIED, but is accessible by other public bodies.

Employment during studies

About one in eight international students is employed. This is a relatively low share compared with Australia and New Zealand, for example, where about one-third of international students are employed, and may reflect the difficulty foreign students have finding a job, especially compared with higher employment levels among Korean university students. In 2017, 76% of international students responded that they had not worked in the past year. Of those that held jobs, 10.9% worked for less than three months. Among those who are employed, most work in education (37%), most often as assistants, in restaurants (24%) and in trade (17%).

Most OECD countries do grant some employment rights to international students, although unrestricted access to employment carries the risk that the student visa becomes a channel for spurious students whose only scope is employment. In this light, the low employment rate of international students in Korea suggests that the student channel is likely used by legitimate students. There is a much higher share of students employed in Japan; in October 2017, there were about 260 000 employers reporting foreign students employed, compared with about 280 000 students total in Japan. Although one student may have multiple jobs with different employers, this still suggests that students in Japan have a much higher rate of employment than those in Korea.

Foreign students in undergraduate or language courses have the right to work up to 20 hours a week; those in graduate courses may work up to 30 hours a week. Work on weekends and holidays is not subject to this limit, so in practice foreign students may work much longer hours during their study. Work rights are not automatic; students must apply to the Immigration Service for a part-time work permit for each job. Authorisation requires a letter of recommendation from the educational institution for part-time work, or a transcript or certificate of attendance demonstrating that the student is in good standing. There are some restrictions on the type of work which can be accepted; any work allowed for Korean students is also allowed for foreign students. Work within the university is generally exempt from the work permit requirement. The work permit can be withdrawn, or extensions denied, if work appears to be having a deleterious effect on study (either through an attendance rate below 70%, or a GPA of 2 or lower).

Retention of international student graduates

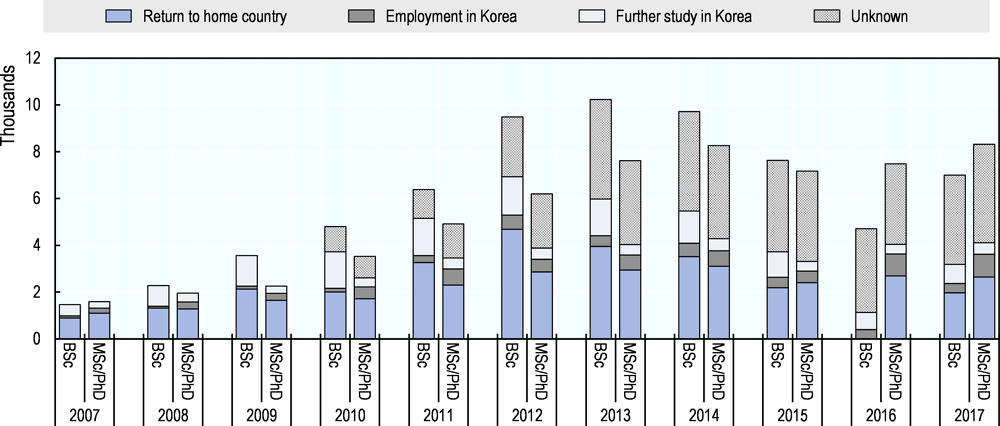

According to the 2017 Survey on Immigrant’s Living Conditions and Labour Force, 48.1% of international students declared their intention to return home after graduation. 41.2% of foreign students wanted to stay in Korea after graduation. 16.8% wanted to continue their studies in Korea and 24% to find employment in Korea. KEDI conducts and annual survey of all university graduates, including international students, which allows a comparison with actual post-graduation behaviour. In contrast to intentions, only about 17.5% actually end up staying, and less than 5.8% of students that receive their bachelor’s degree in Korea found full time employment after graduation. The success rate was slightly higher at (7‑15%, taking low and high ranges from 2007‑17) for students who received a post-graduate degree (Figure 4.16).

Figure 4.16. A small share of international students ends up staying to work in Korea

Note: “Unknown” category added after 2009.

Source: KEDI international students annual statistics.

The low employment rate during studies may partly explain the low retention rate, since employment during studies is positively associated with post-graduation retention (OECD, 2014[15]). Most students who stay in Korea transition to a job search permit, rather than directly to employment. In 2015, more than 4 200 graduates took the D-10 job-search permit (Figure 4.17). Only 430 transitioned directly to the main skilled employment visa, the E-7 visa.

Figure 4.17. Relatively few international graduates stay in Korea

Note: Data for European countries cover only students from outside the European Economic Area. Data for Canada include changes from student to both permanent status and other temporary statuses.

Source: Panel A. Analysis by the OECD Secretariat. Panel B. Korea Immigration Service.

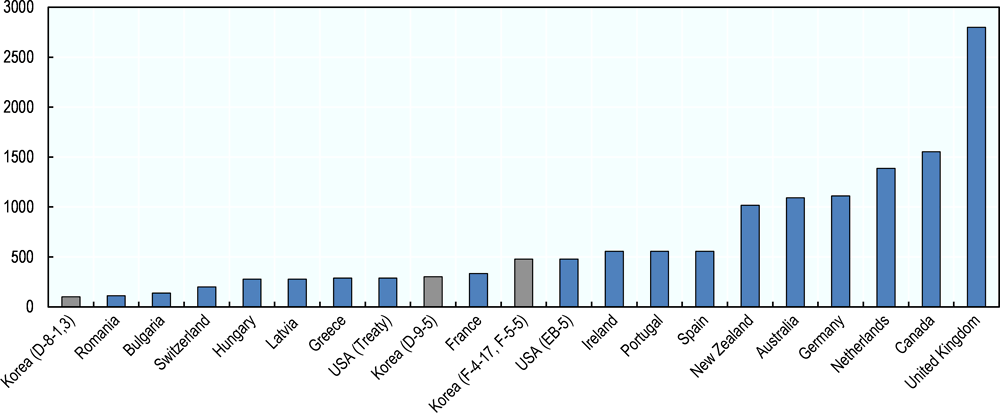

As in many OECD countries, foreign graduates of Korean universities have the right to stay in the country following their studies for a certain period, work and look for a job which will give them access to a work-related permit. Korea’s job‑search visa programme for is among the most generous among OECD countries. Graduates may stay for six months, renewable once for a total of one year. Those with a Masters level or PhD degree from a Korean university may stay up to two years on a job-search visa. The 24 months stay is highly favourable in international comparison (Figure 4.18). Only Australia and Canada offer longer job search periods, and New Zealand a comparable period. The period in the United States (optional practical training, or OPT) allows graduates to stay and work for up to 12 or 36 months in jobs related to their degree, depending on the field, but the visa grant is not automatic and contingent on approval by the institution from which the student graduated. For most European countries, the maximum duration of a job-search visa is 12 months.

Figure 4.18. Korea has a long job-search period for international graduates

Note: "Planned" indicates minimum duration following transposition of EU Directive 2016/801. *In the United States, the OPT is not granted to all graduates and can vary from 12 months (for most subjects under certain conditions) to up to 36 months for graduates in the fields of Science, technology, engineering and mathematics.

Source: OECD Secretariat analysis.

The job-search period appears more than sufficient for international graduates who wish to stay to find a job; most Korean graduates who find jobs find them either before graduation. According to the 2013 survey of graduates in Korea, 48% of male graduates and 40% of female graduates found their jobs before they graduated. Almost 90% found their first job within a year of graduation. It is reasonable to expect that foreign students should also be able to find a job within a year of graduation.

International graduates must find qualifying tertiary-level employment to stay after the job search period ends. This is comparable to the conditions in most other OECD countries, although a few, such as Italy, allow students to take up employment of any kind. The definition of “tertiary-level” employment varies from country to country, however. In Germany and France, the correspondence between the field of study and the field of employment is considered important, and insufficient match a grounds for refusal of a work permit. International students cite many of the same obstacles to retention as other highly-qualified foreigners, related to exclusion from networks (Shin and Choi, 2015[11]).

The D-10 visa for job-search was introduced in 2009 to allow skilled workers an opportunity to seek work. Almost all of these visas are issued within Korea, as a bridge permit for students following graduation and for other professional employment categories to bridge periods of unemployment. The job search permit is often used as a bridge to language teaching; it is the only permit which allows extension of job search for language teachers who are between employers for more than a month. The main category of destination however is the standard specialty occupation permit, E-7 (Figure 4.19). According to a NIIED survey, only 6% of graduates in 2013 found employment during their job search period, primarily through vocational fairs.

Figure 4.19. The job search visa generally leads to language teaching or to skilled employment

Source: Korea Immigration Service.

Investors and entrepreneurs

Korea has a framework for attracting investors, comprising a number of different visas. The business (corporate) investment visa (D-8) is issued to foreign entrepreneurs, investors, and essential-skilled professionals. There are a number of subcategories under the business investment visa, including essential skilled personnel of a company that meets Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) conditions, owners of venture business, investors of private business operated by Korean citizen, and founders of technology-based start-ups. The majority of the recipients are high skilled employees (executives, senior managers, and specialists) dispatched by foreign invested companies to work at local offices in Korea, under the D visas discussed above, but others are investors.

As one of the measures to attract foreign investment in Korea, individuals who qualify for the business investment visa are given favourable treatment during the application process. Foreigners can apply for the business investment visa at a Korean embassy of their native country or enter Korea on visitor status and change their status of sojourn at an immigration office in Korea. The most utilized method by investors is to apply for the visa change at the immigration office inside Invest KOREA, a national investment promotion agency that provides services related to pre-investment consultation, administrative support, and post-investment processes. At Invest KOREA, the visa processing time takes an average 30 minutes and all handling fees are waived. There is a high approval rate because applying for the visa is the last step of the investment process and the pool of applicants are highly qualified. For many foreign companies, communication has already occurred with Invest KOREA for their services during the foreign direct investment process. Project managers at Invest KOREA can arrange for the arrival of foreign investors and the company transferees. Foreigners also visit Invest KOREA for the issuance of visas for dependant family members and housekeepers, re-entry permits, visa extensions, and immigration priority cards (Financial Investor Card).

The maximum period of stay for the business investment visa varies by subcategory. Previously when there were no subcategories under the visa, the maximum period of stay per visa issuance was three years. However, the actual duration of stay has always been generally much shorter. The duration of stay is subject to the discretion of the immigration officer and depends on the size of business, investment amount, and performance records of the foreign invested company. Since the visa can be renewed indefinitely, the government prefers to issue shorter durations to restrict foreigners (including family members) from staying in Korea after an early end to their investment or dispatch period. In 2003, more than 50% of the visa recipients received less than a one-year duration, which brought complaints about the inconvenience of having to periodically renew the visa. In 2005, the government decided to separate investors into subcategories and lengthen the maximum sojourn period for dispatched employees and investors of private Korean businesses to five years. Venture business investors and technology start-up investors became limited to two years. Since then, the government also assented on issuing longer durations - on average at least oen year for first issuances and at least two years for renewals.

Since 2013, an “'Immigrant Investor Scheme for Public Business” has been in place to obtain an F-2 permanent residence visa immediately based on investment in either a public fund or a community development project designated by the Ministry of Justice. The thresholds are KRW 500 million (about 450 000 USD) in designated investment products; the threshold is reduced to KRW 300 million for investors over age 55 who also have KRW 300 million in demonstrable personal liquid assets. The F-2 visa for these investors can be converted to an F-5 visa after five years. The criteria to acquire permanent residence in fact been reduced over time. Prior to 2005, the threshold was at least USD 5m, lowered in 2005 to 2m as well as five jobs created, and in 2008 for investing USD 500m, create three jobs and stay for three years prior to applying for permanent residence.

The scheme for real estate investment allows investment in housing or recreational real estate – not for personal residence. Investment is only allowed in certain regions; the programme began as a special regional investor programme for Jeju Island (see Box 4.4) and has since been extended to other zones.6 The two schemes – public investment and real estate – can be combined to qualify for the latter scheme. Investments which are made in either scheme with a locked duration of at least five years allow the investor to qualify immediately for the F-5 visa.

Foreigners who invest a minimum KRW 500 000 (about USD 450 000) and hire at least five Korean employees are offered permanent residence status. Foreigners with D-8 status that attract a minimum KRW 300 million and hire at least two Korean employees can apply for permanent residency after meeting additional requirements (i.e. passing Level 3 of the TOPIK). Foreign professionals of a foreign-invested company can obtain permanent residency by first living in Korea for three years on the business investment visa and five years on the long-term residency F-2 visa. According to Invest KOREA’s studies, 90% of foreigners on the business investment visa are not interested in receiving permanent residency due to the difficult residence requirements or because they do not desire to live in Korea for a long time.

Box 4.4. The Jeju Island Investor Programme

Jeju province, an island located southwest of Korean peninsula with about 600 000 inhabitants, has a high level of autonomy in governing. In 2001, it was designated as a Free International City with tax exemption and foreigner friendly environment to boost its tourism industry and foreign investment. To attract foreign investors, its self-governing body introduced a special treatment since 2002. The advantages include governmental support for employment, housing supply and long-term stay in case foreigners meet certain requirements. In practice, the local government provides permanent residency, the F-5 permit, when the person invests over KRW 500 million (about USD 450 000) in local industries and employs more than five workers.

A further programme to foster foreign investment in real-estate business came into effect in February 2010. This policy applies to investors who purchase a recreational property designated by the local government such as condominiums, resorts and guesthouses worth more than KRW 500 million. After investment, they can apply for an F-2 residency permit. The first F-2 permit is valid for two years, renewable for additional three years. If they live over five years in Jeju or in elsewhere in Korea they may obtain an F-5 permit. The screening process occurs at the end of five years of residency under the supervision of Ministry of Justice. Once they receive the F-5, foreign investors and their families are entitled to benefit from social systems such as medical care, education and employment with the same rights as Koreans. As of 2017, 1499 investors have received the F-2 visa for Jeju (308 in 2013, 556 in 2014, 323 in 2015, 136 in 2016, and 33 in 2017). Among them, Chinese investors made up the largest proportion.

The visa drove Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) in Jeju. FDI was only USD 115 million from 1962 to 2010, but jumped to USD 126 million in 2011 alone. In 2015, it amounted to 708 million and 900 million in 2016. The total amount of foreign investment under “Permanent Residence Policy for Investors in Real Estate” policy was about USD 1.2 billion between 2010 and 2017.