This chapter examines the Hungarian system of early childhood education and care (ECEC), with a focus on services for children under age three. It analyses the enrolment of children in ECEC, central government’s financial support to ECEC as well as policy reforms introduced to increase the supply of places in Hungary. It also examines the regional variation in the availability of childcare and the causal effect of childcare on maternal employment in Hungary. It complements this analysis with an overview of key developments in ECEC in the context of COVID‑19. It then presents a selection of international practice in ECEC, focusing on the importance of public investment to ensure universal, affordable and accessible ECEC; flexibility in use and provision, and; earmarked provision and proportionate universalism. It also dedicates a section to employer-provided childcare and concludes with a number of takeaways on policy approaches on ECEC.

Reducing the Gender Employment Gap in Hungary

5. Early childhood education and care for children under age three in Hungary

Abstract

All OECD governments support and help fund ECEC in one way or another, but the scale, means and methods of assistance are diverse. For instance, the Nordic countries provide comprehensive publicly operated ECEC systems with heavily subsidised public centre‑based care to which all children are entitled from a young age (often around or before their first birthday). Other countries (e.g. Poland, the Slovak Republic and Spain) provide extensive publicly-operated pre‑primary services for children from around age three but offer less support for younger children and, finally, some countries make greater use of cash supports and demand-side subsidies directed at parents, with the provision of services themselves left largely to the market (e.g. Australia at a national level – although there is supply-side capital and infrastructure funding by government at the state/territory and local government levels, the extent of which varies depending on jurisdiction – and the United Kingdom).

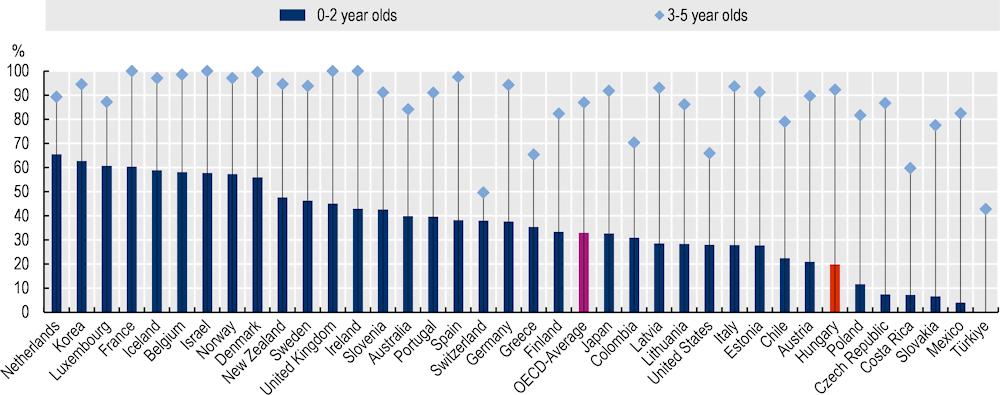

In Hungary, pre‑school children under the age of three receive childcare services in day-care nursery settings and, from the age of three, in kindergartens. While nursery attendance is not mandatory, kindergarten attendance is. Hungary has historically provided extensive public ECEC services for pre‑primary-age children (3‑ to 5‑year‑olds) and pre‑primary childcare enrolment has always been high, and nearly complete since it was made obligatory from age three in 2015 (see Box 5.1). On the other hand, the offer of public day care services for children under age three is more limited, but expanding, and enrolment rates are particularly low (see Figure 5.1 below) but increasing.

Following transition, Hungary chose to maintain much of its public pre‑primary infrastructure (kindergartens). Unlike several of its regional peers (the Czech Republic, Poland and the Slovak Republic), it also maintained part of its system of public day care centres (nurseries), albeit on a reduced scale. The closure of many state‑owned facilities in the early 1990s continues to cause problems with supply today (Hašková and Saxonberg, 2016[1]; Szelewa and Polakowski, 2020[2]).

The majority of childcare services, nursery care settings and kindergartens, are provided and managed by local authorities (mainly municipalities or individual municipal districts in the capital). The non-governmental sector maintains around 50% of the existing nursery care service (according to data from the authentic register of service providers) and is in charge of kindergartens (OECD, 2021[3]).

To support an increase in childcare offer, Hungary has expanded public ECEC funding over the past few decades. While public expenditure on ECEC as a share of GDP has remained relatively stable, real terms spending has increased substantially. Since 2000, real per-head public spending on ECEC has grown from USD (2015) 111 per head in 2000 to USD (2015) 192 per head in 2018 (OECD Social Expenditure Database). The bulk of this growth has come through spending on pre‑primary services for children from age three (OECD Social Expenditure Database; Eurostat ESSPROS Database). At the same time, the central budget has been increasingly investing in the operation of nursery centres over the last years, reaching around HUF 71.5 billion (EUR 178 million) in 2022, almost six times the amount in 2010.

Box 5.1. Hungary’s public pre‑primary services are extensive

Pre‑primary centres (óvoda, or kindergarten) are the only compulsory major form of provision, catering for children from age three until they enter primary school at age six. The large majority of these centres are either publicly operated or government-dependent: in 2019, fewer than 10% of pre‑primary centres were independent private centres (345 out of 4 501) (Eurydice, 2022[4]). There is no parental fee for public services, and parents pay only for meals, at a rate determined by the local authority. Many families (including those on low incomes, those with children with disabilities, and those with three or more children) are provided meals for free (OECD, 2020[5]).

Since September 2015, attendance in pre‑primary education has been compulsory (for at least four hours a day) for all children from three years of age; prior to this, all children had a right to a place in pre‑primary services from age three, but attendance was compulsory only from age five. By law, centres should be open for at least eight hours per day, with exact opening hours left to the centres themselves. Pre‑primary centres in Hungary are open for an average of 10.5 hours per day (Eurydice, 2022[4]). In 2017, children above age three in Hungary spent an average of 35 hours per week in centre‑based care – about average for European countries (European Commission/EACEA/Eurydice, 2019[6]).

The number of pre‑primary education centres has grown steadily in Hungary over the past decade or so, as have the number of available places. Data for the 2020‑21 school year suggest that there are approximately 4 575 pre‑primary centres in Hungary, providing about 386 000 places (KSH, 2022[7]), well above the number of children actually enrolled in pre‑primary education (about 323 000) (KSH, 2022[7]). According to comparable OECD statistics, in 2017, approximately 92% of 3‑ to 5‑year‑olds in Hungary were enrolled in pre‑primary education or primary school – well above the OECD average (87%), and higher than in many of Hungary’s regional peers (e.g., the Czech Republic, Poland, the Slovak Republic, and Slovenia) (Figure 5.1).

However, there may be issues with under-supply in some areas (OECD, 2016[8]) and regional coverage of kindergartens remains unbalanced: in 2020, 31% of settlements had no kindergartens (KSH, 2022[7]). The major cities and other areas with higher-than-average birth rates in particular are likely to suffer from capacity constraints (Eurydice, 2022[4]; OECD, 2016[8]). Recent increases in the number of births could exacerbate the issue in the coming years. As a response, the government is continuing to fund expansion programmes in areas where demand is likely to increase (Eurydice, 2022[4]).

5.1. In Hungary, formal childcare services for children under age three are in short supply but expanding

In contrast to several of its regional peers (Szelewa and Polakowski, 2020[2]), Hungary continues to operate a predominately public system of care services for children under age three in institutional care (nursery and mini nursery), while about 50% of all institutions and services are not state-maintained. Following the principles of sustainable demographic change, of a family-centred and work-based society, and of ensuring availability of childcare for all children of parents who want to work, the childcare system attempts to be flexible. This is achieved by offering different types of nursery models. Nurseries (bölcsőde) are the dominant form of provision. Children can attend day care from 20 weeks until age three, with centres typically open for at least ten hours per day (on-call services are available). Alternative forms include family day care (családi bölcsőde) and, more recently, “mini-nurseries” (mini bölcsőde: smaller centres with lower limits on child-to-staff ratios) and workplace day care centres (munkahelyi bölcsőde: employer-established services with similar child-to-staff ratios to mini-nurseries).

5.1.1. Enrolment of children under age three in ECEC is limited in Hungary

ECEC services cater to children under the age of three, but the typical starting age may differ across countries. In most countries, children enrol within the first year of birth, while in other countries and for specific programmes within countries, children may enter at age one or two. Average enrolment rates of children under age three have risen steadily across OECD countries since 2005, and some countries have particularly accelerated the expansion of ECEC (e.g. Finland and Korea). In many European countries, such expansion has resulted from the objectives set by the EU at its Barcelona 2002 meeting to supply subsidised full-day places for one‑third of children under age three by 2010 (OECD, 2017[9]).

Globally, the rise in ECEC provision over recent decades is strongly correlated to the increase in women’s participation in the labour force, particularly for mothers with children under age three. Countries with higher enrolment rates of children under age three tend to be those in which the employment rates of mothers are the highest (OECD, 2018[10]). Despite efforts to increase the affordability and access to ECEC for very young children, the likelihood of participation is still very contingent on family income, particularly in early childhood development services that rely strongly on private sources of funding. Data from the EU Statistics on Income and Living Conditions (EU-SILC) Survey reveal that on average across European OECD countries, 0‑2 year‑olds in low-income households were one‑third less likely to participate in ECEC than 0‑2 year‑olds in high-income households in 2017 (OECD, 2021[11]).

OECD statistics suggest that in 2019 just 20% of 0‑ to 2‑year‑olds in Hungary were enrolled in recognised ECEC – much lower than the OECD average (33%), although slightly higher than in the Czech Republic (7%), Poland (12%) and the Slovak Republic (7%), and still below that needed for meeting the Barcelona objective (Figure 5.1). Yet, Hungarian authorities stressed that increasingly more children are enrolled in nursery care every year and they question the relevance of the Barcelona objective given the difficult comparability of the childcare systems across countries. They also stressed that day-care is not compulsory, and that as a general rule (with some exceptions) care providers may not exceed the number of places provided for in the operating licence.

Figure 5.1. In Hungary, participation in ECEC is low for very young children under age three – but high for pre‑primary age children

Note: The OECD average excludes Canada. Data for New Zealand, Poland, and Mexico refer to 2017. Potential mismatches between the enrolment data and the coverage of the population data (in terms of geographic coverage and/or the reference dates used) may affect enrolment rates.

1. For 0‑ to 2‑year‑olds: Data generally include children enrolled in ECEC (ISCED 2011 level 0) and other registered ECEC services (ECEC services outside the scope of ISCED 0, because they are not in adherence with all ISCED‑2011 criteria). Data for the United States refer to 2011, for Switzerland to 2014, and for Australia, Austria, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Germany, Iceland, Israel, Japan, Korea, Lithuania, Mexico, New Zealand, Norway, Portugal, the Slovak Republic, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, the Republic of Türkiye and the United Kingdom refers to 2018.

2. For 3‑ to 5‑year‑olds: Data include children enrolled in ECEC (ISCED 2011 level 0) and primary education (ISCED 2011 Level 1). For Greece, data include only part of the children enrolled in early childhood development programmes (ISCED 01).

Source: OECD Family Database, http://www.oecd.org/els/family/database.htm.

5.1.2. Central government’s financial support to ECEC for children under three is substantial

Financial support from the Hungarian central government is substantial. In 2018, the financing system for nurseries and mini-nurseries underwent a qualitative change: the former normative financing was replaced by task-based financing, under which the central budget provides wage subsidies (based on average wages for the statutory number of staff) and operating subsidies (taking into account the tax capacity of the given municipality) for all institutions – helping local governments to ensure a sustainable offer of ECEC services. According to data from municipal reports the central budget covers 80‑85% of the municipalities’ expenditure on day care on average (compared to 40% in 2010), reaching almost 100% in some municipalities. No such data is available for the non-public sector.

Since 2012, nursery care settings have been allowed to charge parental fees. Previously, providers could charge parents only for the cost of meals. The responsible local authority or other maintainer sets the fee, up to a maximum equal to the net cost of providing the place after accounting for central government support. The maintainers also cannot charge families more than 25% of their net per capita income for nurseries and mini-nurseries if the child does not receive free institutional childcare (20% if they do) and 50% for family and workplace nurseries. In this way, the parental fee acts as a “top-up” fee, after central government subsidies and any local government support.

The actual fees (i.e. the cost of childcare to parents) charged vary considerably across regions and families. Authorities have the freedom to charge reduced fees for families on low incomes, or to charge no fee at all, if they wish. This helps ensure services remain affordable for low-income families. In 2019, 44% of the nurseries charged a fee for the care service and 27.8% of children enrolled in nurseries paid a fee for this service. Data from the Hungarian Central Statistical Office show that, in 2021, 70% of children enrolled in institutional-type nursery care did not pay a fee for care, and 63% of them ate free of charge in the same place. Data also show that, in 2021, the average monthly fee for care was HUF 9 500 (EUR 23). According to the same source, the proportion of children in family nurseries and workplace nurseries who received free care was 2%, and families paid an average of HUF 50 000 (EUR 124) in fees. In comparison to several other OECD countries, the net “out-of-pocket” costs of childcare in Hungary are relatively low (OECD, 2020[12]).

Since 2019, the state treasury supports families that are unable to find a local municipal nursery place with up to HUF 40 000 (EUR 102) towards the fees for private family or workplace day care (family nursery, workplace nursery, nursery or mini nursery) and day care (Hungarian State Treasury, 2019[13]). The public subsidy rules for service‑based provision are also undergoing continuous adjustments (including the response to the pandemic emergency periods), and from 2023 the funding calculation under the draft budget law is designed to better reflect specific situations, taking into account the needs of parents and the interests of providers, by proposing the subsidy based on the circumstances of the enrolled child, instead of the previously applied actual day-by-day attendance. The stakeholders’ consultation conducted as part of this study showed strong support for further government intervention in childcare policy, in particular for children aged under three (OECD, 2021[14]).

5.1.3. Hungary has introduced reforms to increase the supply of places for children under age three

In recent years, Hungary has introduced a series of reforms aimed at increasing the supply of places for children under age three. In 2017, the government made the nursery care system more flexible. The institutional framework was extended to include mini nurseries. Moreover, it was made possible to provide day care services beyond institutional settings, through family nurseries (service‑based care in private homes) or workplace nurseries, by providing care independently, in partnership or through a care contract, in order to better respond to local needs and parents’ working hours (Oberhuemer and Schreyer, 2018[15]) (see Section 5.4). This has made access more flexible, even for parents working part-time. In the case of nursery care, the daily care time for a child may be set at a minimum of four hours (for children with special educational needs and children eligible for early intervention and care, the daily care time may be lower) and a maximum of 12 hours. In family and workplace nurseries, parents can request the service not only on certain periods of the day, but also on certain days of the week. The legislation allows for the number of agreements with parents to exceed the authorised number of places – de facto, allowing a place to be shared between two children in terms of time arrangements.

In 2017, the government introduced new requirements for all local authorities with a population of less than 10 000 to maintain some form of care service if at least 40 children under age three live in the area and/or if at least five families request access (Oberhuemer and Schreyer, 2018[15]; Eurydice, 2022[4]). In 2018, the government announced the release of substantial development domestic funds to local authorities for the creation of new day care places (Eurydice, 2022[4]). In addition, the rules for the use of central budget funding for the operation of municipal day nurseries and mini day nurseries have changed significantly from 2020‑21. The ten‑day absence rule for nurseries, which excluded children who have been absent for more than ten days in any day of the month from the calculation of the budget, has been removed. The new rule for budget planning is that the number of children counted as “in care” corresponds to either the number of children enrolled on 31 January of the year in question or 80% of the number of places in the nursery or mini-care centre provider’s register, whichever is more favourable. Measures have also been progressively introduced to render opening hours more flexible, to support those most in need to access nursery care, to ensure possibilities to create workplace nurseries by employers and to ensure more adequate remunerations of childcare professionals. As a result, the ratio of children aged below three with no childcare facility in their vicinity has decreased from 26% to 20.1% between 2017 and 2021 (KSH, 2020[16]).

The above reforms have contributed to increase the childcare offer: 56 000 places were available in 2021 (KSH, 2022[7]), 58 500 were operational in September 2022 and 13 000 places are under construction. This suggests that Hungary is going to reach its own target of 70 000 nursery places and is expected to exceed it by creating new nursery care places, which will increase the number of municipalities where some form of care is available.

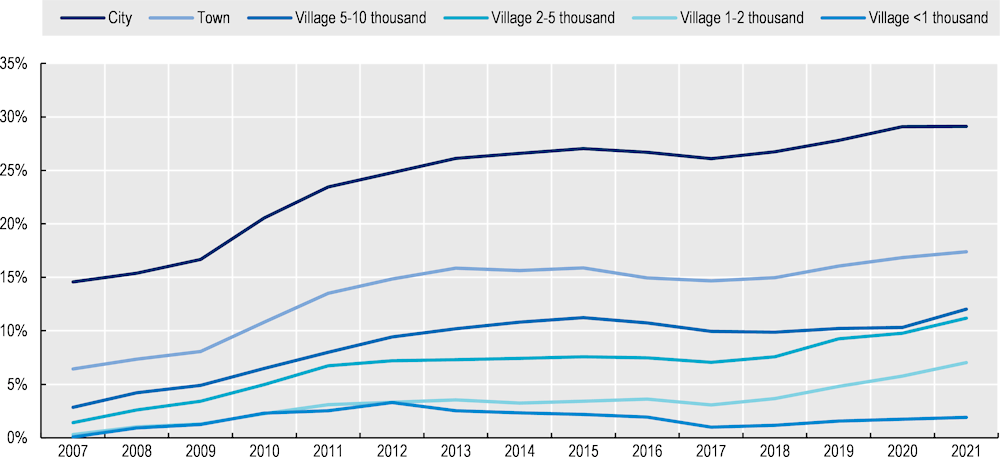

This should alleviate some of the current issues of supply shortages (Szelewa and Polakowski, 2020[2]; OECD, 2016[8]): even in county centres and Budapest (labelled as “cities” in Figure 5.2), available capacity would only have sufficed to enrol one in four children aged below three, and in small villages (which is where about one‑third of children live), childcare for this age‑group was practically unavailable (calculations by the Budapest Institute for Policy Analysis using administrative data based on the official records of residence – TEIR). As discussed above, the availability of paid parental leave, as well as attitudes and parental preferences also affect potential demand for childcare services.

5.1.4. Regional variation persists in the availability of childcare in Hungary

In the years prior to the pandemic, childcare places for children under age three were filled at an average rate of 94%, though usage dropped during the pandemic (in May 2020 it was 90%). The expansion of nursery places seems to have been fairly well-targeted in the sense that average utilisation rates were higher in the year preceding the expansion in municipalities that embarked on such investments, compared to those that decided not to do so (based on calculations by the Budapest Institute for Policy Analysis using municipality-level administrative data on childcare capacity and utilisation). With the investments so far, utilisation rates seem to have picked up very fast after the first year of investment, when utilisation rates near 0.95 regardless of settlement size. Between 2016 and 2021, the increase in capacity was largest in villages and small towns with between 1 000 and 5 000 inhabitants, where availability had been very limited (Figure 5.2). While capacity did not increase in small villages of below 1 000 inhabitants, these municipalities can “buy” capacity from nearby municipalities that have a childcare facility. Nevertheless, regional variation persists in the availability of childcare (KSH, 2020[16]). At the same time, it is important to acknowledge an increase in the number of settlements with some form of nursery provision over the last years.

Figure 5.2. Availability of childcare: Places/children aged 0‑2 by size of settlement, 2007‑21

Note: City includes Budapest and county centres.

Source: Calculations by the Budapest Institute for Policy Analysis using administrative data on municipal childcare provision.

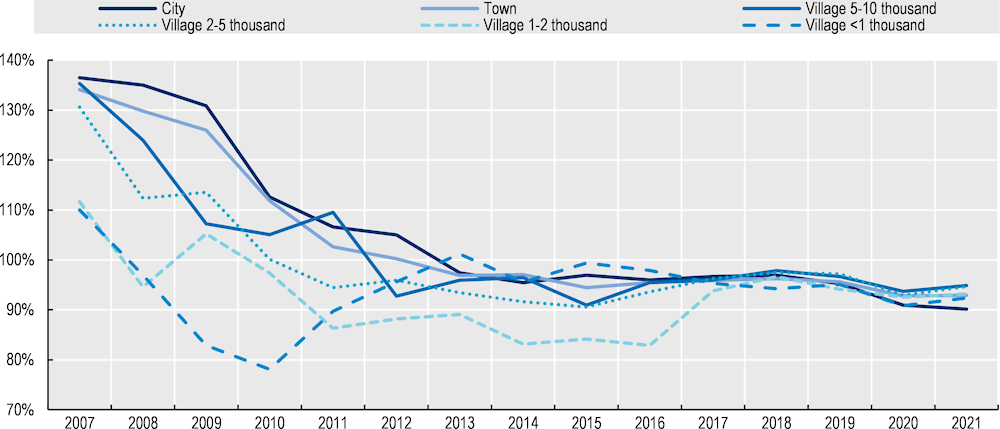

Average (over-)utilisation rates have declined steadily since 2007 (see Figure 5.3 and its note). This can be attributed to the increase in capacity (as shown in Figure 5.2) and to administrative measures, such as the rules on average group size and financing. The number of children has also declined slightly.

Figure 5.3. Average utilisation rates (number of children enrolled/number of available places) by settlement size, 2007‑21

Note: Available places is defined as the number of places authorised in the licence of the institution (which may be below what is physically possible). Values above 100% occur when nurseries enrol more kids than they have places. Until 2010 there was a rule that allowed nurseries to enrol 20% more kids than their licenced capacity. In 2009 and 2010 utilisation dropped sharply due to a rule that increased maximum group size by 20% in 2010 and set that capacity as a hard ceiling, i.e. centres could no longer go above the licenced capacity.

In small villages of below 1 000 inhabitants, utilisation rates show more volatility due to the small sample size (i.e. few small villages maintain a nursery service).

Source: Calculations by the Budapest Institute for Policy Analysis using administrative data on municipal childcare provision.

5.1.5. The causal effect of childcare on maternal employment in Hungary

Empirical evidence on the causal link between childcare and maternal employment in Hungary is scarce. Lovász and Szabó-Morvai (2019[17]) provide an important exception: using data from 1998 to 2011, they show that if childcare availability by nurseries increased up to the level of kindergartens, maternal employment rates would increase by 24%. This section presents the results from an extension of this analysis by the Budapest Institute for Policy Analysis (2022) using the 2016 Microcensus of Hungary augmented by the 2011 Census of Hungary and the T-STAR Hungarian regional database. This analysis provides an estimate for a positive effect of childcare availability on maternal employment and also considers the association between childcare availability and kindergarten enrolment rates, in order to better understand the main channel through which this effect takes place.

Identifying the effect of childcare availability on maternal employment

In the analysis, childcare availability is measured by local nursery and kindergarten coverage where children live. The analysis constructs nursery and kindergarten catchment areas based on the 2011 Census. Assigning each municipality to a unique childcare centre (the one where most children from the municipality would attend nursery) results in 493 areas mostly centred around a locally important town or city. Then, using the T-STAR regional database for each of these areas, childcare availability is calculated as the proportion of nursery places to the number of 0‑2 year‑olds, and the proportion of kindergarten places to the number of 3‑5 year‑olds for 2016. Average nursery coverage is around 14%, while average kindergarten coverage is around 140%.

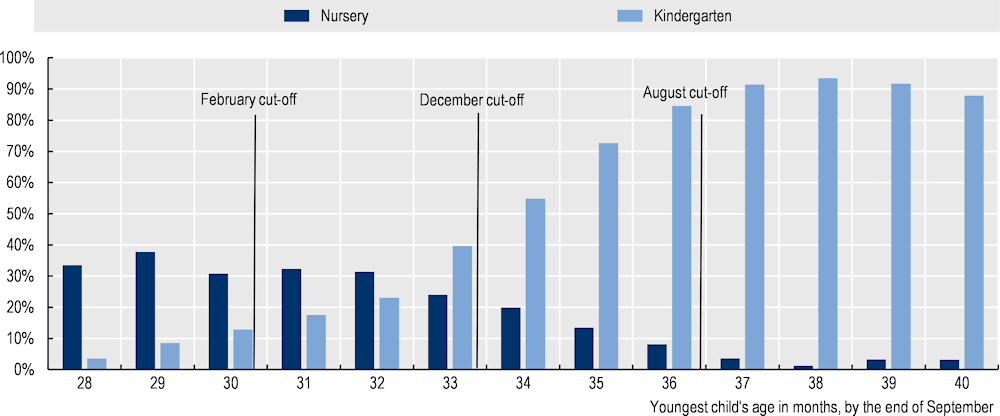

The identification strategy exploits the fact that there are many more childcare places in kindergartens than in nurseries. Moreover, according to national guidelines, there are two alternative age thresholds for possible admittance (Figure 5.4). Children who celebrate their third birthday by the end of August must start kindergarten education (and the kindergarten is obliged to admit them) in September. However, as the figure shows, also younger children attend kindergarten. According to the law, children who have reached the age of 2.5 years can also be admitted to a kindergarten, but this is subject to the consideration by the kindergarten and depends on the available excess capacity. Thus, children who turn three by the end of February might be admitted to kindergarten in September of the previous year. There is also a third, informal cut-off for those who turn three at the end of December. Noticeably, nursery attendance decreases, and kindergarten attendance increases at the December cut-off, while this is less evident at the February cut-off.

Figure 5.4. Youngest children’s childcare facility attendance

Note: Data pertains to children born between May 2013 and May 2014.

Source: Calculations by the Budapest Institute for Policy Analysis based on the 2016 Microcensus of Hungary.

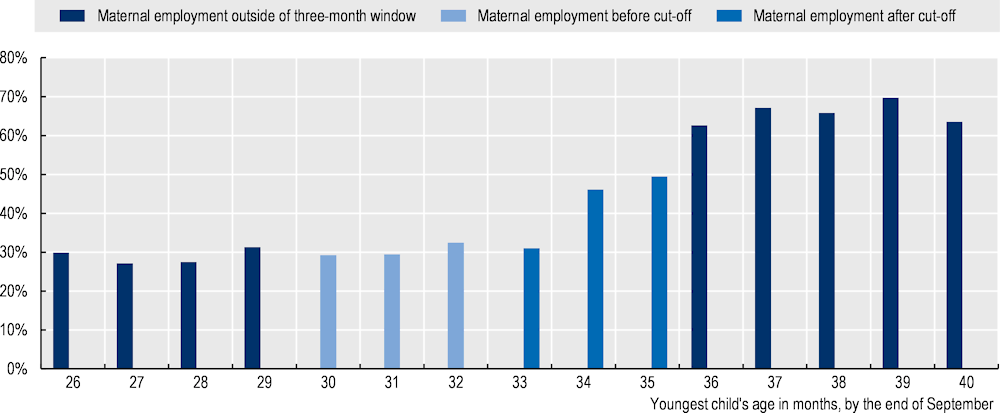

Proceeding with the December cut-off point and using a three‑month time window around it, the change in maternal employment can be considered (Figure 5.5). While for children under two and a half years of age (i.e. before the December cut-off) the employment rate of mothers fluctuates around 30%, after the cut-off it goes up to around 45%, driven by the mothers of children born in November and October. This change could be attributed to the practice that kindergartens accept children of this age group, suggesting that local childcare availability plays a crucial mediating role in mothers’ return to the labour market.

Figure 5.5. Maternal employment rate by youngest children’s age in months before and after the December cut-off

Note: Data pertains to children born between May 2013 and July 2014.

Source: Calculations by the Budapest Institute for Policy Analysis based on the 2016 Microcensus of Hungary.

Increased childcare availability would lead to significantly higher maternal employment

After controlling for observables of the mother and the father, along with sub-county regional fixed effects to capture differences in local labour markets, the results suggest that if nurseries had coverage up to the level of kindergarten, employment of mothers with very young children (aged 0 to 2) would increase from around 29% to around 36% (around 25% higher).

This still lags behind the employment rate of around 60% of mothers whose children reached the legally mandated age of three years old before September. One potential reason is that with increased availability of childcare, not all mothers want to or can return to the labour market either due to preferences or because they are expecting another child. Therefore, it is useful to look at the effect of increased childcare availability on actual attendance. The analysis suggests that from the 50% of children not yet in childcare at the age of 2.5 years old, around one in three would be placed in a childcare facility.

Regarding maternal employment, it is further estimated that increased childcare availability has a larger positive effect for mothers with three children, aged 35 to 39, or living in villages, and a remarkably lower (but still positive) effect for those where the father is not present. The lower impact for single mothers may be due to time management constraints: childcare is not available (nor recommended) for more than eight hours a day, even if the law limits the maximum daily care time for children under three years of age to 12 hours and allows for on-call care up to 19 hours in institutional day care. The practice makes it difficult for a lone parent to take up a full time job (especially if work hours are inflexible) and part time jobs are scarce.

With regards to childcare facility attendance, the results indicate substantial heterogeneity with the channel being more important for mothers with a disadvantaged socio‑economic background. Increased childcare availability has a larger effect for mothers who must commute to the centre of their nursery catchment area, have primary or lower secondary educational attainment, live in a village, or are less than 29 years old. The higher effect size for mothers who live in municipalities without a nursery suggests that at least part of the effect likely comes from increased proximity to a childcare provider (since more municipalities have kindergartens than nurseries), rather than from the increased number of places.

These results have direct policy implications. Firstly, they show that increasing childcare availability in nursery facilities can significantly increase maternal employment, especially for younger and less educated mothers. Secondly, they highlight the differential regional availability of nursery facilities, and that enhancing the spread of nursery facilities can contribute to increase maternal employment further.

5.2. Key developments in childcare in the context of COVID‑19

In Hungary, there were two lockdowns during the pandemic affecting care for children. In the first wave, nurseries, mini-nurseries, public kindergartens and primary schools were instructed to close between 16 March and 25 June 2020 (Gábos and Makay, 2021[18]). According to an interviewee representing a social partner organisation, in the first wave, municipalities (and other entities maintaining nurseries) could decide whether to suspend services: facilities in the countryside tended to continue providing services, while most of those in Budapest closed down. As a rare example, a district municipality in Budapest provided continuous services and also offered 24h supervision in one of their nurseries near a hospital (Farkas et al., 2020[19]).

The Hungarian Government made it mandatory for mayors of the settlements and capital districts to provide free of charge, on-call service of childcare for children whose placement could not be solved otherwise. From 5 May 2020 until 1 June 2020, local authorities had to provide supervision in small groups (up to five children) for children whose parents had employment-related duties and requested the service (Farkas et al., 2020[19]; OECD, 2021[3]). However, 6‑8% of parents in kindergarten, while only 1% of parents with children in elementary schools, requested supervision for children (Juhász, 2021[20]). Although there is no hard-nosed evidence, such differences may be due to the possibility that schools, more than kindergarten, discourage parents from asking for supervision as it was more difficult for them to provide both supervision and online teaching, while kindergarten had no obligation to provide support to children staying at home.

ECEC facilities were obliged to provide services with a maximum period of temporary closure of two weeks from 25 May to 31 August 2020 outside Budapest, and from 2 June to 31 August 2020 in Budapest (Farkas et al., 2020[19]). Furthermore, the provision of workplace childcare services was simplified and incentivised for the period from 30 April to 31 August 2020: no operating licence was needed for the establishment of workplace childcare services, it was sufficient to report service provision to the local authority/capital district authority and have permission for operation from the public health institution. The state provided fiscal supports for companies, firms, and other agencies for the operation of childcare services (OECD, 2021[3]).

The government continued to pay the usual per capita funding for nurseries and kindergartens to support municipalities in maintaining public childcare institutions during the lockdowns and to facilitate the payment of care workers’ wages. With regards to nursery care, new funding rules that were adapted to the emergency situation came into force at the end of 2020. An action plan with practical instructions for nursery care providers on the epidemiological procedures was also published. Layoffs were rare in municipal care services – during lockdowns, care workers either provided online services, went on paid leave or were directed to other social services, such as long-term care or elderly care. The representatives of nursery employees actively provided information and advice to nurseries and disseminated good practices, especially during the first wave. They recommended that nurseries online keep enrolment open throughout the year and prepare online materials to support parents (KSH, 2020[16]).

During the second wave in autumn 2020, ECEC facilities and primary school grades one to four were kept open. During the third wave (4 March 2021‑19 April 2021), kindergarten services were suspended with no supervision provided for children even in small groups, and all schools were to operate remotely, while nurseries remained open. Kindergarten services were resumed on 19 April 2021 and elementary schools were partially re‑opened with on-site education for students up to 4th grade.

Despite efforts, more limited ECEC services meant that parents, and especially mothers, had to take on additional care responsibilities. Results from the OECD Risks that Matter 2020 survey show that, across OECD countries, mothers were much more likely than fathers to report having taken on a majority of the additional care. Moreover, unemployed mothers in families where the father continued to be employed represent a large share of those who took on the care burden. The reverse did not take place in families where the father was unemployed, but the mother was in employment – implying a double burden on these mothers. As it follows, on average across the OECD, mothers with children under 12 years old were the most likely group to move out of employment during the pandemic (OECD, 2021[21]). Data based on a representative survey of Hungarian adults implemented at the end of May 2020 shows that the average hours spent on childcare activities increased by 11.4 hours per week for women, and by 6.8 hours per week for men. The gender gap in the increase in care time was larger among college‑educated and white‑collar parents and in big cities and among women working in home‑office. The analysis also suggests that, for many women, home office was dictated by the need to look after their children (Fodor et al., 2021[22]).

Results from the OECD Risks that Matter 2020 survey also suggest that public supports may have played a role in reducing inequality at home. While, generally, countries with more days of school closures also had higher gender inequality in the take‑up of additional unpaid care work, countries with historically higher levels of spending on family supports also tended to have smaller gender inequality in the take‑up of additional care work (OECD, 2021[21]).

The Recovery and Resilience Plan submitted in May 2021 includes a commitment to continue the expansion of nursery capacities by 3 300 new places to be established by the end of 2025. The plan is part of the demography chapter, but it is justified by the need to improve the work-life balance of families with children and also to strengthen labour market resilience. The plan also builds on a survey of municipalities and churches to assess their needs and intentions regarding capacity development. Conducted in November 2020, this survey recorded a need for 12 000 places (Hungarian Government, 2021[23]). The Recovery and Resilience Fund is planned to fund new places in settlements with more than 3 000 inhabitants (Hungarian Government, 2021[24]), while the European Multiannual financial framework is planned to fund the expansion of nursery places in smaller villages, new places in employer-provided childcare as well as upgrades in the quality of existing places.

5.3. International practice in ECEC

This section presents a selection of international practices and approaches related to public investment to ensure universal, affordable and accessible ECEC; flexibility in ECEC use and provision; earmarked ECEC provision and proportionate universalism; and employer-supported/ provided childcare. Access to affordable ECEC of good quality for every children is recognised as a right in Principle 11 of the European Pillar of Social Right (European Union, 2017[25]) and further stressed in the European Child Guarantee (European Commission, 2021[26]) (see Box 5.2). Recruiting and retaining skilled staff is a long-standing challenge for the ECEC sector, and key for the quality of childcare services (OECD, 2019[27]).

5.3.1. Public investment to ensure universal, affordable and accessible ECEC

Different OECD countries have increased the relevance of childcare in their policies and public investments, stressing the role of ECEC as part of a continuum of supports for families with children (see Box 3.1).

ECEC as part of a comprehensive policy – Denmark and Sweden

In Nordic countries, ECEC is a public good and publicly financed. Childcare is seen as part of a comprehensive policy ensuring continuity between birth and compulsory school age. High quality and universal access to ECEC contributes to the success of childcare provision in these countries.

For instance, Sweden provides extensive financial support to parents accessing childcare. ECEC is considered an extension of and a complement to family childcare. Children are guaranteed a place in formal childcare since age one and childcare costs are mainly covered by the state. Parents pay some fees, but contributions are capped; they are directly proportional to parents’ taxable income and inversely proportional to the number of children (3% for the first child, 2% for the second child, 1% for the third child and no fee for the following children; with a decreasing ceiling from the first to the third child). Pre‑school to children between three and six is provided for free up to 15 hours per week. On average, parents pay around 11% of the real cost of a place in pre‑schools, showing the relevance provided to ECEC in public investment (Hofman et al., 2020[28]).

In Denmark, according to the rules for the childcare guarantee, municipalities must provide a place in a day-care facility for all children older than 26 weeks until the child starts school. Parents are entitled to full-time places, and the priority is given to children of two working parents. Places are subsidised to at least 75% of their cost, with subsidies being paid directly to childcare providers and the remainder covered through income‑related parental contributions. If the municipality cannot fulfil the childcare guarantee, parents have the right to: have the expenses covered at another day-care facility place in another municipality, or for a place in a private facility or staying in a private childcare scheme, or to a financial subsidy to have the child taken care of (Finance, 2020[29]; Eurofound, 2016[30]). Moreover, if there is more than one child in the household in ECEC, parents can additionally receive a sibling subsidy (including for out-of-school activities) (European Commission, 2022[31]).

Public efforts to increase ECEC participation and quality – Germany

Germany’s experience illustrates a policy shift towards growing public support for ECEC. During the mid‑2000s, the German federal government started to increase public investment and introduced changes in the ECEC system. In 2013, a Nordic-style legal entitlement to ECEC for all children aged one and older was launched and followed by several major spending programmes – such as the KiTaPlus programme on all-day ECEC (see Section 5.3.2), and the recent Gute‑Kita Gesetz (the “Good Daycare Facilities Act”).

Public and private day-care centres for children are financed by the local authorities, the Land and through parental contributions. In addition, private ECEC is also financed by the provider. The Federal Government supports the Länder with around EUR 5.5 billion between 2019 and 2022 and supports the quality of and participation in ECEC nationwide through Land-specific measures. With these funds, the Länder can launch actions to ease the burden of fees on families and/ or to enhance quality in childcare (Eurydice, 2021[32]) – e.g. ensuring needs-based provision, improving the ratio of qualified staff to children, or hiring and retaining qualified staff. The approach of the measure is complex but personalised: the federal government conclude agreements with all Länder and the concrete measures are individually designed according to their specific needs. Public childcare attendance rates have increased over the years, which also positively affected maternal employment rates (Hofman et al., 2020[28]).

5.3.2. Flexibility in ECEC use and provision

Flexibility is an increasingly important feature for a successful ECEC offer – taking into account the changing schedules of the world of work and the existence of different family models and work-life balance preferences. Adapting the childcare offer to the changing needs of working parents can support their labour market participation and attachment.

Adjusting ECEC to work schedules and family preferences – Denmark

The Danish Government passed a political agreement in 2017, which aimed at increasing the quality of ECEC facilities, adapting them to both working hours and family preferences. This brought to the amendment of The Day-Care Facilities Act in 2018.

To support parents who work outside the normal opening hours of ECEC facilities, Denmark made available services at extended or unusual opening hours through a “combined ECEC” option. A part-time place in a regular ECEC facility can be complemented with financial support to hire a flexible home‑based caretaker while the parents are at work. Access to this option is restricted to parents who can prove a work-related need for care outside the ordinary opening hours of ECEC facilities. The municipalities must conduct an inspection of those families using combined ECEC.

Denmark also strengthened its support to parents’ right to choose a particular ECEC facility or childminder, understanding that families have different values. Parents can be waitlisted for a specific ECEC – even if at the time of enrolment that specific centre has insufficient capacity. They can also remain on the waiting list for a specific facility, even if their child is enrolled elsewhere (Rasch-Christensen et al., 2018[33]).

Flexible opening hours of ECEC facilities: The KitaPlus programme – Germany

In Germany, ECEC facilities have long opening hours, which provides working parents with great flexibility. In addition, the KitaPlus programme was launched in 2016 to support parents who have unusual working hours through customised care time. The programme provides ECEC institutions and childminders with grants for pilot projects targeting e.g. single parents, parents working on shifts, young parents who are still studying, etc. Facilities can use the grant for a variety of goals, provided that the approach responds to a needs analysis and follows a pedagogical concept. In most cases, grants are used to extend the opening hours to evening hours, overnight or during the weekend. The programme also supports costs for counselling services for parents, professional training, hiring of additional staff and the adaptation of the facilities (European Commission, 2019[34]).

5.3.3. Earmarked ECEC provision and proportionate universalism

In all EU countries, funding mechanisms to make ECEC affordable have been reinforced, often on the basis of proportionate universalism principles, i.e. ensuring access for all whilst compensating or further supporting those in a more vulnerable financial position (Fresno, Meyer and Bain, 2019[35]). Special attention to disadvantaged children is at the core of the European Child Guarantee (Box 5.2). The ‘proportionate universalism’ (2010[36]) approach helps overcome the dichotomy between universal ECEC policies and targeted support provision: the former tends to be used more often by higher income families than by lower income families; while the latter may reach disadvantaged families, yet often lack quality (Vandenbroeck, 2020[37]). In many OECD countries children from less advantaged backgrounds are much less likely to participate in ECEC than their better-off peers (OECD, 2016[38]).

In order to reduce the financial barriers that disadvantaged groups suffer in accessing ECEC, a common approach across OECD countries has been to lower fees and/or subsidise ECEC costs. Responses range from universal free education (e.g. in Luxembourg childcare vouchers are provided that pay for all ECEC up to 20 hours), to fee waivers and/or subsidies for vulnerable groups (e.g. in Denmark), or a combination of universal services with needs-based services for vulnerable groups (e.g. in Sweden) (Fresno, Meyer and Bain, 2019[35]). More examples are presented below.

Box 5.2. The EU Child Guarantee and policy priorities for children

The model supports the combination of universal actions with targeted measures addressing vulnerable groups of children

The EU has provided increasing attention to combine “more universal actions with targeted measures addressing vulnerable groups of children and young people” (European Commission, 2021[26]), including guaranteeing universal access to good quality ECEC for all. In a 2019 Recommendation, the Council recommended to pay particular attention to remedy actions for cases where market-based ECEC services imply unequal opportunities to access or lower quality for disadvantaged children (European Union, 2019[39]). The recently approved European Child Guarantee aims to prevent and combat social exclusion by ensuring the access of children in need to key ECEC, education, health care, nutrition and housing services. While Member States are expected to “continue developing their universal policies for all children”, access to certain services including ECEC needs to be “effective and free of charge” for the most vulnerable. This stresses “the importance of guaranteeing effective and non-discriminatory access to quality key services for children who face various forms of disadvantage” (European Commission, 2021[26]).

Priority criteria and income‑related parental fees – Flanders, Belgium

In Flanders, different policies have introduced income‑related parental fees, also taking into account indirect ECEC costs (meals, transport, etc.). When there are shortages of places, special day-care schemes are offered to vulnerable families, who have priority access to crèches. In some cases, (universally accessible) preschools in Flanders may receive additional funding when enrolling more children from vulnerable families. Moreover, some Flemish cities have a central enrolment policy for all childcare centres – establishing quotas for different target groups and ensuring that the population using childcare is representative of the entire population of the city. In addition, several regions have engaged staff with expertise on the specific needs of vulnerable families (Vandenbroeck, 2020[37]).

Support to children of Roma families

In some countries, Roma parents benefit from special conditions to access ECEC. In Croatia, for instance, they are exempt from paying kindergarten fees. Various community based ECEC initiatives at a smaller geographical scale also promote Roma inclusion in ECEC settings. For example, the European “Toy for Inclusion” project promotes an inclusive approach to non-formal ECEC with the establishment of play-hubs located in areas that are reachable for all families and are designed and run by multi-sectoral teams composed by representatives of communities, school and preschool teachers, health services, parents and local authorities (ICDI, 2019[40]).

5.4. In focus: Employer-provided childcare

Employers can play a key role in supporting and/or directly providing ECEC services, for their employees exclusively or as a broader offer also open to the local community. These services can take different forms, from facilities (e.g. kindergarten or other childcare amenities, including in-company crèches) to financial support (e.g. for parents using private childcare facilities or other care support services). In Europe, many large private employers provide their employees with emergency back-up care and subsidies for childcare/nanny services up to 10‑20 days a year (Unicef, 2019[41]).

Depending on the company’s resources, it can either provide on-site childcare services, collaborate with other employers for the provision of inter-company nurses, or collaborate with a private childcare provider or the government. Other options include linking with facilities in the community, providing financial support to employees, or offering advice, referral services and back-up emergency solutions, which decrease the need for parents to take unscheduled time off from work (ILO, n.d.[42]).

This type of childcare services benefits both companies and employees. The company benefits from talent retention and greater recruitment success; lower absenteeism and leaves; the creation of a “sticky” benefit that enhances retention throughout the employee life cycle; increased employees’ productivity, loyalty, engagement and life quality; and a competitive edge and opportunities to carry out Corporate Social Responsibility policies, which can positively influence a company’s external reputation. At the same time, employees benefit from tailor-made labour schedules, tranquillity of having their child nearby, combination of commute to work and childcare, better work-life integration, a guaranteed quality of childcare services at a lower cost, increased happiness at work, and higher gender equality. Corporate support for childcare represents an important tool to increase women’s participation in the labour market – also in leadership roles (OECD, 2021[43]; Sasser Modestino et al., 2021[44]; ILO, n.d.[42]). It can also have positive outcomes for children as well as for the local territory and society.

Nonetheless, there are challenges to the feasibility and sustainability of such services. These typically relate to the high investment and costs, the company size, space availability, the age composition of the workforce and therefore the turnover of children, the percentage of women in the workforce and staff turnover. Moreover, these services are not equally common across sectors or geographic areas, and their continuation may depend on corporate performance. They are also subject to the employer’s values and visions as regards women’s labour market participation as well as childcare values and practices.

5.4.1. International practice in employer-supported/ provided childcare

Different public interventions can support employer-provided childcare so that more companies – of any size – can offer such services. These range from increasing incentives (e.g. increasing the threshold of childcare costs for each child that can be fiscally deducted); increasing employers and employees’ awareness of the benefits of these services, as well as employers’ good knowledge of the needs of employees; facilitating dialogue between local communities and stakeholders to promote public-private partnerships and forms of territorial welfare; and supporting the design of ad hoc solutions (OECD, 2021[43]). Overall, public support to employer-provided childcare can enhance the continuity and sustainability of these services, protecting them from potential fluctuations in the company’s performance. Various examples of government support to employer-provided childcare were identified across OECD countries in the international workshop organised for this study (OECD, 2021[43]) and additional desk research:

In Spain, these include: corporate tax reliefs in expenditures for building and providing childcare service for their employees; flexible payment plans, reducing the payroll costs for companies and increasing the net income for employees due to lower social security contributions; baby checks/vouchers: provision of a state amount of money for families with children under three years of age; and awareness raising campaigns on work-life balance, including leading by example (for instance, public administrations providing childcare services for their employees) (OECD, 2021[43]).

As an example of the public administration providing childcare to its employees, in 2018 the Office of the Government of Lithuania opened a childcare room, which can be used by employees’ children during working hours. Further discussions followed on opportunities to open care rooms also in other public institutions (Hofman et al., 2020[28]).

In Italy, employer-provided childcare is expanding but at a low pace. It is usually offered by large companies in wealthier urban areas. SMEs typically struggle to offer such services, given the high costs, the risk of an insufficient turnover of children over time, and space constraints. A model of employer-provided childcare is creation of public-private partnerships. Typically, companies in a specific territory bear part of the costs of running a public childcare facility, which is open to the children of companies’ employees and to citizens from the local area. A specific example consists of a nursery facility being available to the children of the company’s employees, children assigned through municipal rankings and other children from private users, with different costs for each group (OECD, 2021[43]).

In France, corporates that contribute to childcare costs benefit with 76.5% of costs reimbursed through tax credits and deductions (OECD, 2021[43]).

In the Netherlands, employers pay 0.5% of their payroll as childcare funding and employed parents may receive a subsidy of 72% of childcare costs (OECD, 2021[43]).

In the United Kingdom, employers that decide to set up an in-company nursery facility are exempt from the payment of tax and national insurance on the value of the nursery, provided the service complies with certain conditions (it must satisfy the formal requirement of an appropriate registering organisation and be available and accessible to all employees). Employers offering the childcare facility may also claim tax relief for the day-to-day costs of the nursery (UK Government, n.d.[45]).

5.4.2. Employer-provided childcare in Hungary

Employer-provided childcare (“workplace nurseries” as a new service from 2017) is one of the available childcare delivery modes in Hungary, yet still not common. As of May 2022, in Hungary there were 13 workplace nurseries, for a total of 131 places.

Workplace nurseries primarily target the children of employees. The service is available for children between 20 weeks and 3 years of age, with one carer assigned to groups of 7/8 children (and an additional assistant when there are at least 5 children in the group). A workplace nursery may operate primarily in the building where the work is performed, in a property owned by the employer, or rented by the employer for this purpose (OECD, 2021[43]).

In 2017, major changes were introduced in the regulation of employer-provided childcare:

Modes of provision: Hungary has eased the requirements for employers wishing to offer childcare services compared to other available childcare modes, while setting standards as regards training. Differently from before, the service does not have to be provided exclusively by the employer but can be outsourced to another provider – for instance buying places in an existing childcare centre.

Strong focus on training: carers must undertake 100 hours of specialised training.

Financial support: financing in 2022 amounts to HUF 1 391 150 (EUR 3 396) – including wage compensation – per child/year, more than 13 times the specific amount of support available in 2017. The support can be provided as a tax-free benefit. Operating expenses are deductible from corporation tax.

Evidence collected through the international workshop conducted for this project highlights that Hungary recognises the potential benefits related to employer-provided childcare for both the employer (it contributes to ensuring a more loyal, co‑operative workforce; a more attractive corporate culture; trust; return on investment in workforce training; and lower costs for recruitment, selection and training) and the employee (it provides a sense of security and ensures a better work-life balance). In this respect, Hungary has been active both through public campaigns and by leading by example (public administrations providing childcare services) and has enhanced the amount of public funds available for the creation of such services.

Nonetheless, demand for employer-provided childcare seems to remain limited. The stakeholders’ consultation conducted as part of this study shows that employer-provided childcare, which had been contemplated as an option by some mayors, met limited enthusiasm among the stakeholders consulted: employers may struggle to offer such services, and employees may prefer childcare options closer to home. Nevertheless, different local authorities showed interest in this form of provision and some employers found novel HR solutions in this direction, such as summer camps for children when nurseries are closed (OECD, 2021[14]).

5.5. Key takeaways on policy approaches

The examples above show important efforts towards ensuring the availability of accessible, affordable and quality childcare services, increasingly adapted to the specific needs, work-life balance preferences and changing working schedules of parents. They highlight various dimensions of childcare policies:

Integrating the offer of childcare supports and services can increase their relevance, especially if supported via territorial and partnership approaches:

Countries with advanced childcare systems tend to offer a “continuum of supports”, at the intersection between family and education policies. An integrated offer can contribute to a higher awareness of the availability and relevance of childcare services and their positive role for children’s development, supporting the use of these services.

An integrated offer requires co‑operation between actors involved in childcare provision. Partnerships involving public and private stakeholders at a local level, for instance, have the potential to respond to the demand of childcare services in a tailored manner.

The availability of childcare and a good territorial coverage can contribute to maternal employment.

ECEC use can be enhanced through flexible, adapted solutions and alternative childcare provision modes:

Strengthen ECEC flexibility of provision can support parents’ labour market participation and attachment through an increased use of childcare services adjusted to work schedules and family preferences. This relates both to the opening hours flexibility and the availability of different provision modes. This also contributes to fight informality in the care sector.

Responding to the childcare needs implies taking into account the diversity of the population, and to provide for both universal and earmarked solutions. This can contribute to reach especially vulnerable groups.

Employer-supported/ provided childcare has potential to respond to the needs of some working parents and support mothers’ labour market participation, as well as to offer a complementary service to the local territory. Challenges typically relate to the sustainability and affordability of such services by the employer, and the awareness of the benefits deriving from this provision.

COVID‑19 reinforced the understanding that childcare services are crucial for parents’, and specifically mothers’, labour force participation:

Although fathers are increasingly spending time at home with their children, the COVID‑19 and the related lockdowns showed that mothers are disproportionately responsible for childcare.

Ensuring childcare provision and supporting families can help in creating more gender equal societies.

Affordability of childcare remains a key issue and needs further focus on policy in the aftermath of the COVID‑19 pandemic.

References

[33] Commission, E. (ed.) (2018), Peer Review on “Furthering quality and flexibility of Early Childhood Education and Care”.

[30] Eurofound (2016), The gender employment gap: Challenges and solutions. Details of policy measures to support the labour market participation of women, https://www.eurofound.europa.eu/sites/default/files/ef1638_-_the_gender_employment_gap_-_annex.pdf.

[31] European Commission (2022), Denmark - Child care, https://ec.europa.eu/social/main.jsp?catId=1107&langId=en&intPageId=4486.

[26] European Commission (2021), Proposal for a Council Recommendation establishing a European Child Guarantee, https://ec.europa.eu/social/main.jsp?langId=en&catId=89&newsId=10024&furtherNews=yes.

[34] European Commission (2019), Peer review on “Furthering quality and flexibility of Early Childhood Education and Care“- Sythesis report, European Commission, Brussels, https://ec.europa.eu/social/BlobServlet?docId=20719&langId=en.

[6] European Commission/EACEA/Eurydice (2019), Key data on early childhood education and care in Europe - 2019 Edition, https://doi.org/10.2797/894279.

[39] European Union (2019), Council Recommendation of 22 May 2019 on High-Quality Early Childhood Education and Care Systems, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=uriserv:OJ.C_.2019.189.01.0004.01.ENG.

[25] European Union (2017), European Pillar of Social Rights, https://doi.org/10.2792/95934.

[4] Eurydice (2022), National Education Systems: Hungary, https://eacea.ec.europa.eu/national-policies/eurydice/content/hungary_en (accessed on 27 August 2020).

[32] Eurydice (2021), Germany - Early Childhood Education and Care.

[19] Farkas, A. et al. (2020), “A koronavírus járvány miatt elrendelt rendkívüli bölcsődei szünet alatt történt online kapcsolattartás kutatási eredményei”, The Hungarian Pedagogical Association, Budapest.

[29] Finance, D. (2020), https://lifeindenmark.borger.dk/family-and-children/day-care/rules-for-day-care-facilities.

[22] Fodor, É. et al. (2021), “The impact of COVID-19 on the gender division of childcare work in Hungary”, European Societies, Vol. 23/1, pp. 95-110.

[35] Fresno, J., S. Meyer and S. Bain (2019), Feasibility Study for a Child Guarantee - Target Group Discussion Paper on Children living in Precarious Family Situations, European Commission, https://ec.europa.eu/social/BlobServlet?docId=22869&langId=en.

[1] Hašková, H. and S. Saxonberg (2016), “The Revenge of History: The Institutional Roots of Post-Communist Family Policy in the Czech Republic, Hungary and Poland”, Social Policy & Administration, Vol. 50/5, pp. 559-579, https://doi.org/10.1111/spol.12129.

[28] Hofman, J. et al. (2020), After parental leave: Incentives for parents with young children to return to the labour market, European Parliament.

[23] Hungarian Government (2021), HELYREÁLLÍTÁSI ÉS ELLENÁLLÓKÉPESSÉGI ESZKÖZ (RRF), https://www.palyazat.gov.hu/helyreallitasi-es-ellenallokepessegi-eszkoz-rrf#.

[24] Hungarian Government (2021), Recovery and Resilience Plan, https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/IP_21_2442.

[13] Hungarian State Treasury (2019), Kisgyermeket nevelő szülők munkaerőpiaci visszatérését ösztönző, http://www.allamkincstar.gov.hu/files/GINOP/bolcsode/T%C3%A1j%C3%A9koztat%C3%B3%20K%C3%B6zlem%C3%A9ny_2.pdf.

[40] ICDI, (. (2019), Toy for Inclusion, http://www.toyproject.net/project/toy-inclusion-2/.

[42] ILO (n.d.), “Workplace solutions for childcare”, https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---ed_protect/---protrav/---travail/documents/event/wcms_145935.pdf.

[20] Juhász, D. (2021), Szakszervezetek: a kormány hallgassa meg a pedagógusok, szülők véleményét!, https://nepszava.hu/3116334_szakszervezetek-a-kormany-hallgassa-meg-a-pedagogusok-szulok-velemenyet.

[18] Koslowski, A. et al. (eds.) (2021), Hungary country note, https://www.leavenetwork.org/annual-review-reports/.

[7] KSH (2022), Hungarian Central Statistical Office StaDat Summary Tables, http://www.ksh.hu/?lang=en (accessed on 18 August 2020).

[16] KSH (2020), A kisgyermekek napközbeni ellátása, 2020 (Childcare for small children, 2020), http://www.ksh.hu/docs/hun/xftp/stattukor/kisgyermnapkozbeni/2020/index.html.

[17] Lovász, A. and Á. Szabó-Morvai (2019), “Childcare availability and maternal labor supply in a setting of high potential impact”, Empirical Economics, Vol. 56/6, pp. 2127-2165.

[36] Marmot, M. (2010), Fair society healthy lives. The Marmot Review, http://www.instituteofhealthequity.org/projects/fair-societyhealthy-lives-the-marmot-review.

[37] Nieuwenhuis, R. (ed.) (2020), Early Childhood Care and Education Policies that Make a Difference, The Palgrave Handbook of Family Policy.

[15] Oberhuemer, P. and I. Schreyer (eds.) (2018), Early Childhood Workforce Profiles in 30 Countries with Key Contextual Data, http://www.seepro.eu/English/Country_Reports.htm (accessed on 14 January 2019).

[21] OECD (2021), “Caregiving in Crisis: Gender inequality in paid and unpaid work during COVID-19”, OECD Policy Responses to Coronavirus (COVID-19), OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/3555d164-en.

[11] OECD (2021), Education at a Glance 2021: OECD Indicators, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/b35a14e5-en.

[43] OECD (2021), Technical Support to Reduce the Gender Employment Gap in the Hungarian Labour Market - Report on the international workshop.

[14] OECD (2021), Technical Support to Reduce the Gender Employment Gap in the Hungarian Labour Market - Summary report on stakeholders’ views and beliefs, OECD, Paris, https://www.oecd.org/gender/Summary-report-on-stakeholders-views-ENG.pdf.

[3] OECD (2021), “The OECD Tax-Benefit Model for Hungary: Description of Policy Rules for 2020”, OECD, Paris, https://www.oecd.org/els/soc/TaxBEN-Hungary-2020.pdf.

[12] OECD (2020), “Is Childcare Affordable?”, Policy Brief on Employment, Labour and Social Affairs, OECD, Paris, http://oe.cd/childcare-brief-2020 (accessed on 11 July 2020).

[5] OECD (2020), The OECD Tax-Benefit Model for Hungary: Description of Policy Rules for 2019, OECD, Paris, http://www.oecd.org/els/soc/TaxBEN-Hungary-2019.pdf.

[27] OECD (2019), Good Practice for Good Jobs in Early Childhood Education and Care, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/64562be6-en.

[10] OECD (2018), “How does access to early childhood education services affect the participation of women in the labour market?”, Education Indicators in Focus, No. 59, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/232211ca-en.

[9] OECD (2017), Starting Strong 2017: Key OECD Indicators on Early Childhood Education and Care, Starting Strong, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264276116-en.

[8] OECD (2016), OECD Economic Surveys: Hungary 2016, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/eco_surveys-hun-2016-en.

[38] OECD (2016), Who uses childcare? Background brief on inequalities in the use of formal early childhood education and care (ECEC) among very young children, OECD, Paris, http://www.oecd.org/els/family/Who_uses_childcare-Backgrounder_inequalities_formal_ECEC.pdf.

[44] Sasser Modestino, A. et al. (2021), “Childcare Is a Business Issue”, Harvard Business Review, https://hbr.org/2021/04/childcare-is-a-business-issue.

[2] Szelewa, D. and M. Polakowski (2020), “The “ugly” face of social investment? The politics of childcare in Central and Eastern Europe”, Social Policy & Administration, Vol. 54/1, pp. 14-27, https://doi.org/10.1111/spol.12497.

[45] UK Government (n.d.), Expenses and benefits: childcare, https://www.gov.uk/expenses-and-benefits-childcare/whats-exempt.

[41] Unicef (2019), Linking family-friendly policies to women’s economic empowerment - An evidence brief, https://www.unicef.org/media/95096/file/UNICEF-Gender-Family-Friendly-Policies-2019.pdf.