This chapter provides background information on economic inactivity in Poland. While the COVID-19 pandemic has had a relatively mild effect on the Polish labour market, it exposed inequalities between groups and places. The pandemic may drive some individuals durably outside the labour market as they become discouraged to look for work, or cannot work due to new caring responsibilities. It also revealed the relatively unfavourable position of vulnerable groups on the Polish labour market. Older people with low skills, amongst the most excluded before the pandemic, faced the highest risk of employment loss due to the pandemic. Those living in less economically dynamic regions face a compounded risk.

Regional Economic Inactivity Trends in Poland

2. Economic inactivity in Poland before and after the COVID-19 pandemic

Abstract

In Brief

The COVID-19 pandemic has interrupted a sustained fall in unemployment in Poland. The seasonally adjusted registered unemployment rate increased by 1 percentage point, from 5.2% to 6.2%, between January 2020 and February 2021. Unemployment figures, however, may not reflect the extent of the effect COVID-19 had on Polish labour markets. Some potential job seekers, discouraged in face of the decline in labour demand, may not actively be searching.

While COVID-19 primarily presents a short-term labour market shock, the repercussions may be long-term if individuals are permanently pushed out of the labour force. In Poland, there is a clear link between regional level unemployment rates, long-term unemployment rates and economic inactivity rates. Higher short-term unemployment may push some unemployed into long-term unemployment and then economic inactivity.

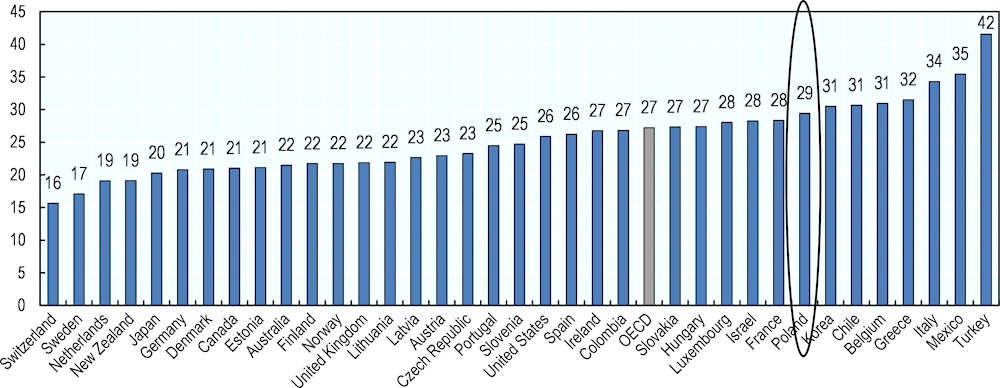

29% of the population in Poland was economically inactive in 2019, two percentage points higher than the OECD average. Within this group, the COVID-19 downturn could have accentuated labour market exclusion for women and those with lower levels of education. Youth are also vulnerable, as they face weaker labour market attachment and are highly represented in sectors most at risk from the pandemic.

Those between 55 and 64 years old represent over 35% of the economically inactive population in Poland, the third highest share in the OECD. Although this age cohort may be less vulnerable to the COVID-19 crisis, the increase in the in-work poverty rate from 10.4% in 2010 to 11.7% in 2019 suggests this group may be struggling to find decent work.

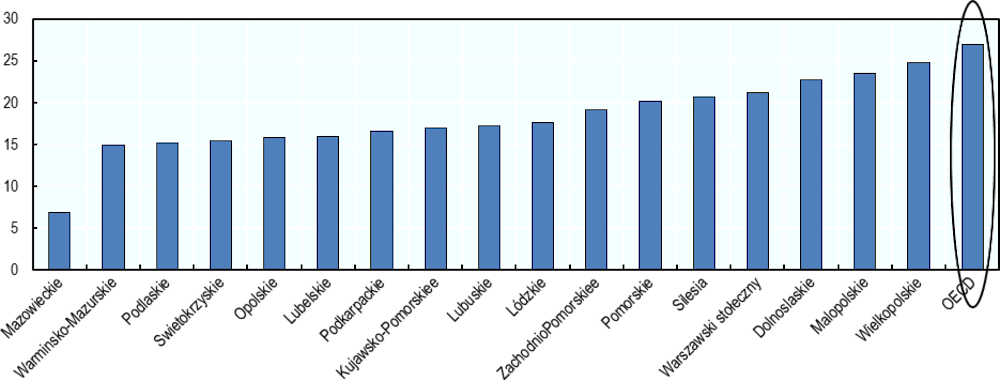

OECD calculations show 20% of employment is at risk in Poland due to the pandemic, less than the OECD average of 27%. Poland houses a relatively smaller share of jobs in at risk sectors, such as retail, food services or accommodation, compared to other OECD countries.

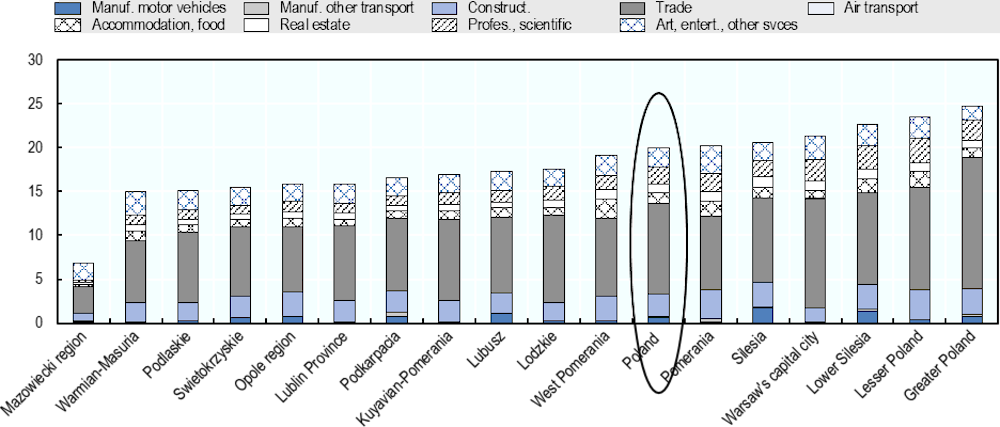

Risk of job loss from COVID-19, however, reveals different levels of vulnerability across regions. In Mazowieckie, less than 7% of jobs are in sectors most at risk, compared to 25% in Greater Poland. Employment in trade-related sectors shapes COVID-19 related risk in Poland due to exposure to the global drop in demand and supply chain disruptions. Over 22% of jobs in Greater Poland, Lesser Poland and Lower Silesia contain jobs in trade-related sectors, representing 396 000, 329 000 and 276 000 jobs respectively. If demand in these sectors does not return to pre-pandemic levels, these groups face a risk of prolonged economic exclusion and inactivity.

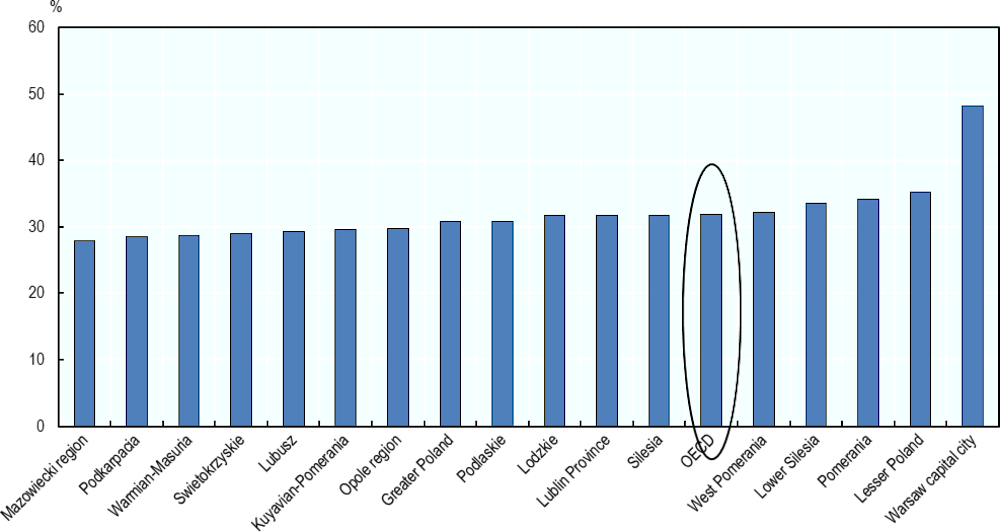

Teleworking is a tool for resilience in the COVID-19 economy. In over half of Polish regions, such as Greater Poland, however, the share of jobs amenable to teleworking is lower than the OECD average of 32%. This may be due to the higher share of industrial jobs requiring physical presence. Polish SMEs, in particular, could benefit from targeted support to make the shift to long-term teleworking and ensure those unable to remote work do not face prolonged economic exclusion.

2.1. Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic, while not having had large effects on unemployment in Poland, is putting a halt to steady employment growth. The COVID-19 pandemic is likely to accentuate disadvantages for those most excluded from the labour market, potentially increasing economic inactivity among certain groups and across Polish regions. To analyse these phenomena, the remainder of this chapter is divided into two parts: section 2.2 gives an overview of the initial labour market implications of COVID-19 and section 2.3 delves into the different categories of economically inactive groups in Poland. The unit of analysis throughout this report is the TL2 level shown in Figure 2.1.

Figure 2.1. Understanding Polish Regions

Note: English names of TL2 regions. Polish names in brackets.

Source: Eurostat and FAO Global Administrative Unit Layers.

2.2. The COVID-19 pandemic exposed disadvantages that certain groups and regions face across Poland

2.2.1. The COVID-19 labour market impact was relatively mild in Poland

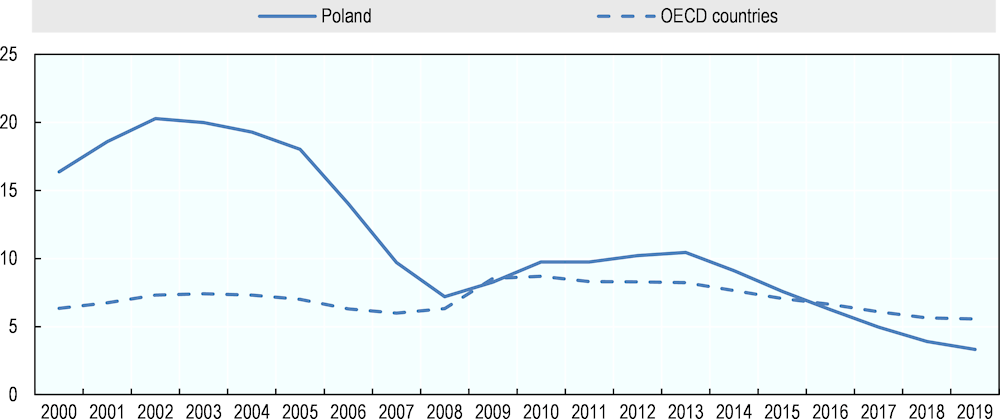

Before COVID-19, unemployment had been declining in Poland. The 2008 financial crisis caused a downturn in the Polish labour market, particularly in sectors reliant on external demand, such as manufacturing, though its effects on unemployment were more moderate than other EU countries (ILO, 2015[1]). Recovery was already underway in 2010. After unemployment peaked at 16.4% among 15 to 64 year olds in 2000 and rose again to 10.5% in 2013 post-2008 crisis, unemployment fell to a historic low of 3.3% in 2019 (Figure 2.2). In OECD countries on average, meanwhile, unemployment reached a high of 8.7% in 2010 following the 2008 financial crisis, before falling progressively to 5.6% in 2019. Over this period, the fall in unemployment in Poland was due to rising employment rates, driven by economic growth, and a shrinking labour force (OECD, 2018[2]).

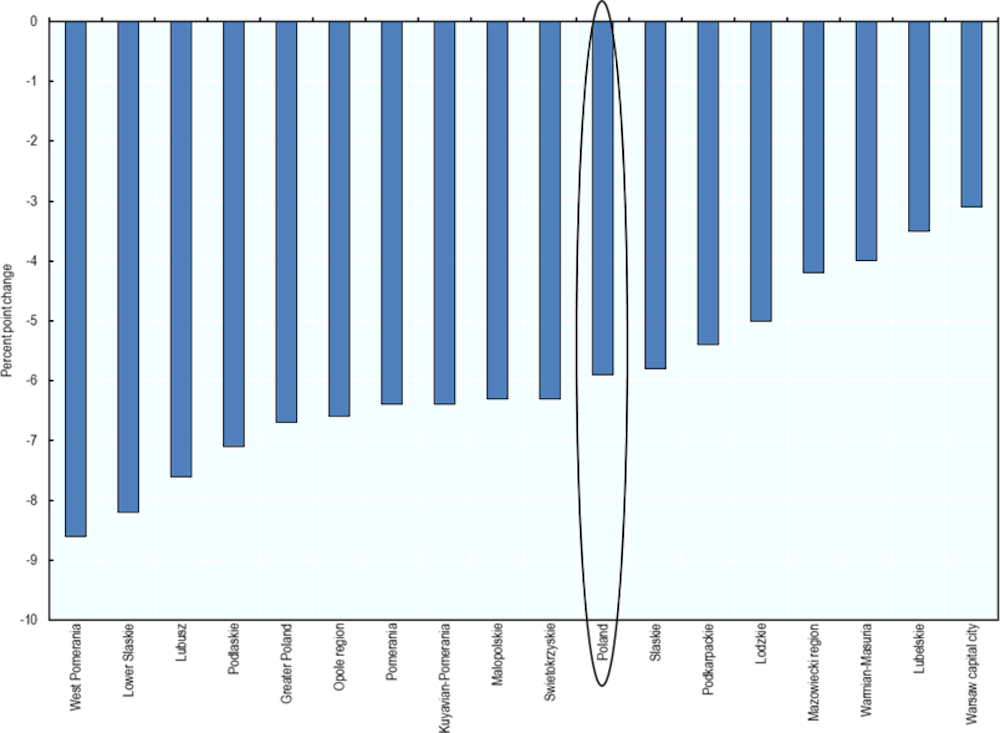

Regional differences in unemployment fell in Poland between 2010 and 2018. This trend only took place in approximately one-third of OECD countries (OECD, 2020[3]). Unemployment in multiple regions with higher unemployment rates in 2018, such as West Pomerania and Lower Silesia, fell more than the Polish average. In these regions, for example, unemployment fell 8.6 and 8.2 percentage points between 2010 and 2018 respectively, greater than the national average of 5.9 percentage points (Figure 2.3).

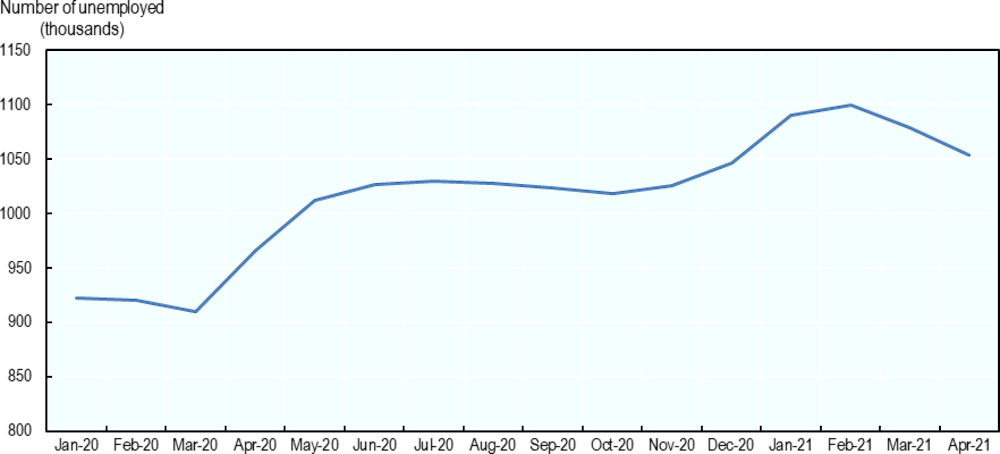

Since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, the number of registered unemployed has risen in Poland. Firms faced a sharp downturn in activity when lockdowns began across OECD countries in March 2020. SMEs have been particularly affected by the downturn due to closures in sectors with a large presence of SMEs, such as food services. Small firms may be less capable of withstanding the COVID shock due to their reliance on more limited markets and suppliers (OECD, 2020[4]). Between January 2020 and February 2021, the number of registered unemployed people rose from 922 197 to 1 099 500, as lockdown measures were put in place and the Polish economy felt the effects of the global downturn (Figure 2.4). Over this period, the seasonally adjusted registered unemployment rate increased by 1 percentage point, from 5.2% to 6.2% (OECD data). Since then, the number of registered unemployed in Poland has started falling slowly again and stood at 1 053 800 in April 2021.

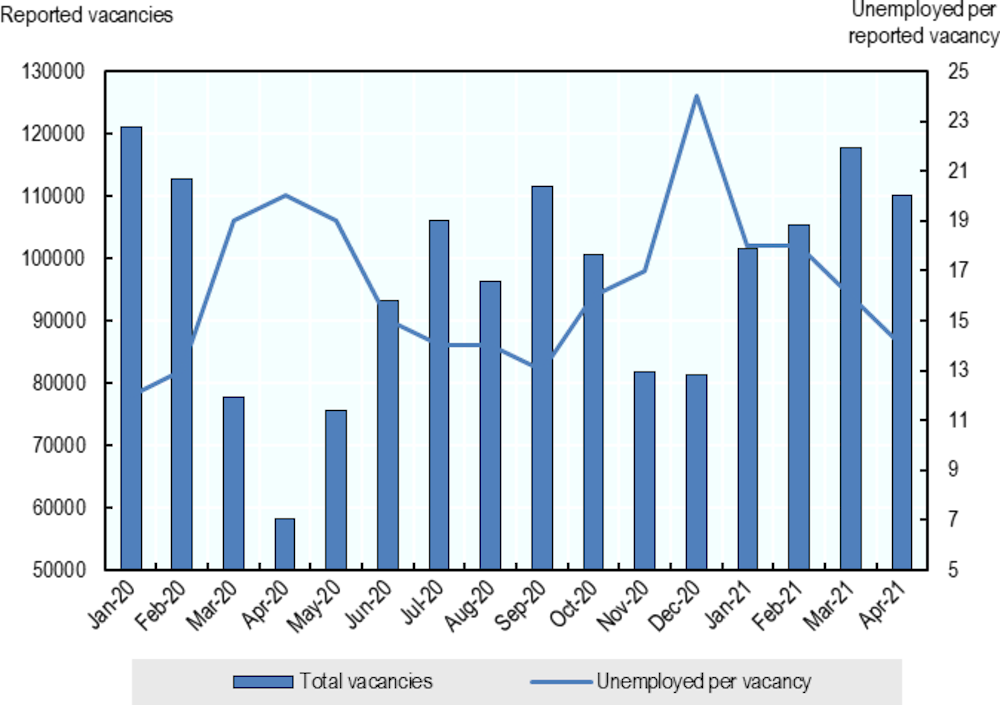

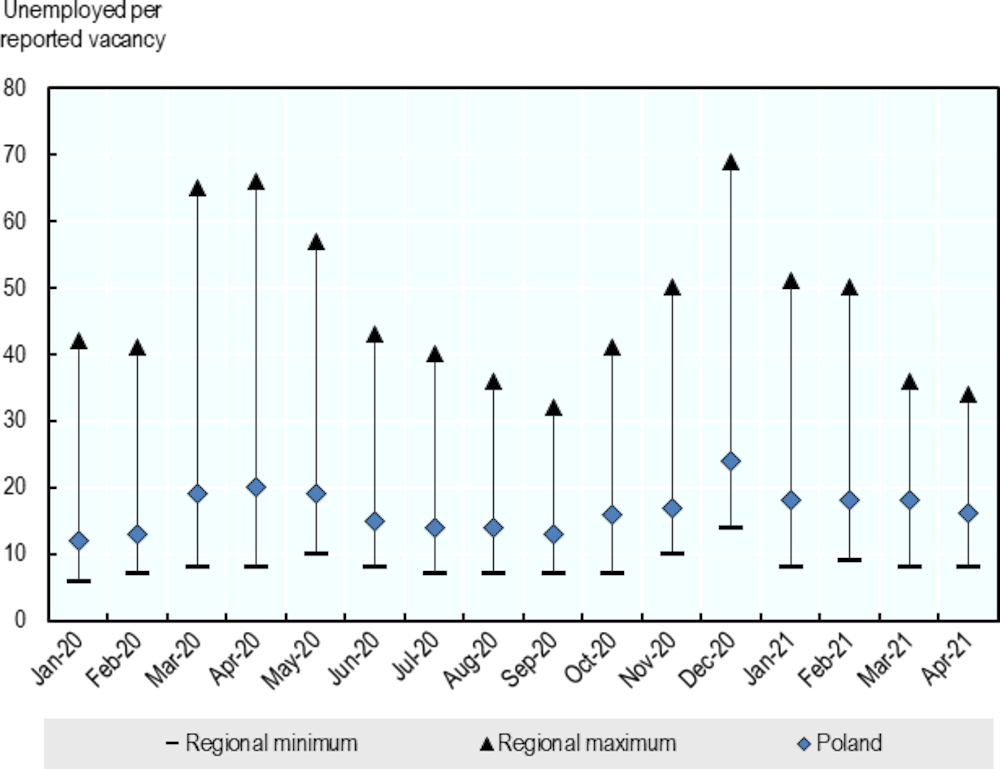

While Poland has come out of the COVID-19 relatively unscathed, the lack of labour demand during the downturn could have long-term impacts on the most vulnerable. Many of the most vulnerable, those already economically inactive or with weaker attachment to the labour market, may face greater labour market exclusion during and following the COVID-19 pandemic due to the drop in labour demand. Figure 2.5 shows that when the COVID-19 pandemic started in March 2020, the number of vacancies reported by employers to local labour offices dropped sharply from 112 700 to 77 600. Combined with the rise in the registered unemployed, this led to an even sharper increase in the number of registered unemployed per reported vacancy. Both metrics recovered over the summer of 2020, but labour demand took another hit in October 2020 when COVID-19 case numbers started rising again. Most recent numbers from March and April 2021 indicate that demand for labour is now rebounding. Figure 2.6 shows that some regions were hit disproportionally by the drop in labour demand caused by COVID-19. The regions of Eastern Poland, in particular Podkaparcia, Podlaskie and Lublin experienced the sharpest absolute rise in the number of registered unemployed per job offer.

Figure 2.2. Unemployment has decreased significantly in Poland since 2002

Source: OECD Statistics.

Figure 2.3. Unemployment had decreased before COVID-19 across all Polish regions, particularly in those regions with higher rates in 2010

Note: The unemployment rate is computed as the share of unemployed people over the labour force, for the age group 15/64.

Source: OECD (2020), "Regional labour markets", OECD Regional Statistics (database), https://doi.org/10.1787/f7445d96-en.

Figure 2.4. Over 2020, the COVID-19 crisis increased unemployment in Poland, but recovery is seen in 2021

Note: The data may be subject to change due to the renewal of models for seasonal adjustments. See Statistics Poland for methodological information.

Source: Statistics Poland, K4-G12-P2961.

Figure 2.5. Labour demand in Poland fluctuated during the COVID-19 pandemic

Note: Total vacancies is the number of job offers reported to the Powiat labour office by employers if there is at least one vacant place of employment or a place of occupational activation. Unemployed is the number of registered unemployed.

Source: Statistics Poland, K4-G12-P2965

Figure 2.6. Regional differences in the number of unemployed to reported vacancies remain significant

Note: Total vacancies is the number of job offers reported to the Powiat labour office by employers if there is at least one vacant place of employment or a place of occupational activation. Unemployed is the number of registered unemployed.

Source: Statistics Poland, K4-G12-P2965.

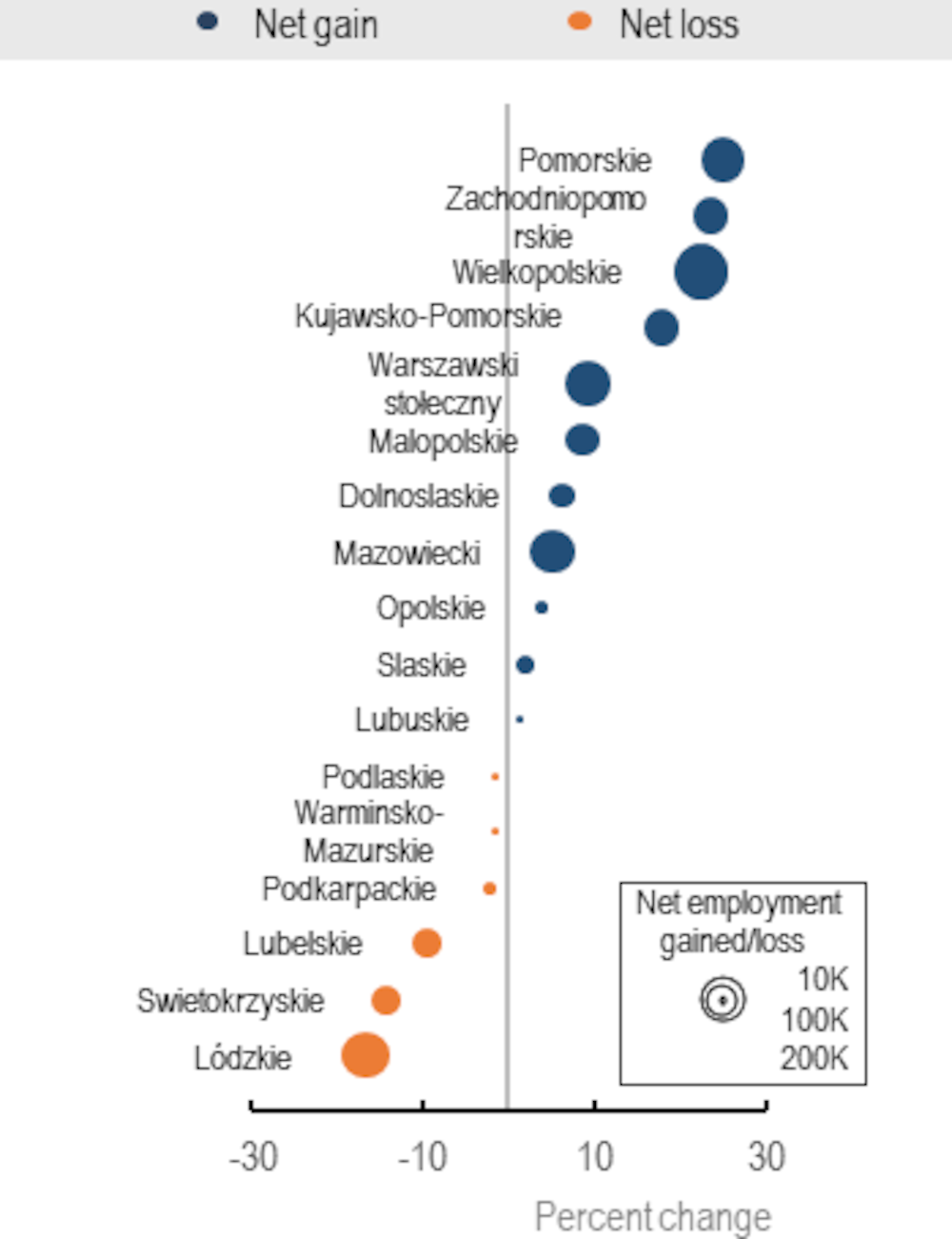

2.2.2. Although unemployment recovered across regions after the 2008 crisis, employment growth suggests disparities are growing

The 2008 crisis, although of a different nature than the 2020 pandemic, showed differentiated impact across regions. In one-third of Polish regions, the number of people employed declined (Figure 2.3). In regions such as Lodzkie, Swietokrzyskie and Lublin, net employment decreased by 16.7, 14.2 and 9.5 percentage points respectively, or a fall of over 220 000, 82 000 and 89 000 employed people respectively. This phenomenon may be driven by job destruction in certain regions, or emigration. OECD research has also identified a possible growing geographic concentration of jobs in Poland (as measured by the number of people employed), which may be more noteworthy for high-skill jobs relative to all jobs (OECD, 2020[3]). Jobs requiring advanced degrees may be increasingly concentrated in more economically developed regions.

Figure 2.7. Employment numbers, however, reveal divergence among regions

Note: Total employment, age group 15 to 64 years. Regions displayed in Polish language, please refer to figure 1 for English translation.

Source: OECD Regional Statistics.

2.2.3. Young people in particular suffer from the negative impact COVID-19 has on the Polish labour market

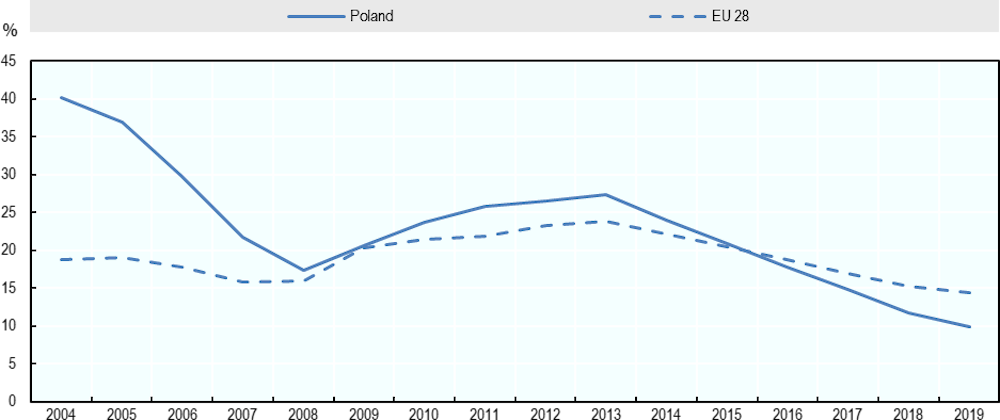

As after the 2008 crisis, it is likely that youth will face the steepest labour market consequences from the COVID-19 downturn. In Poland, youth unemployment grew relatively more than the average across OECD countries, before falling more rapidly. Between 2008 and 2013, youth unemployment grew from 17.3% to 27.3%, before falling to 9.9% in 2019 (Figure 2.8). The EU-28 average, meanwhile, increased from 15.8% to 23.7% over the same dates, before falling to 14.4% in 2019. The significant increase in youth unemployment in Poland after 2008 reveals weak labour market attachment for this group. In particular, young people in Poland may suffer from less stable contractual conditions compared to other EU countries.

The COVID-19 crisis also presented specificities that accentuate disadvantage for youth. COVID-19 lockdowns have driven many workers in food services, accommodation and tourism sectors which tend to employ large shares of young people, into Job Retention (JR) schemes or unemployment. Youth are also suffering a second hit related to their socio-professional engagement: interruption or decrease in quality of education/training, decline in connections with colleagues, peers and mentors, and higher levels of poverty and mental health pressure (OECD, 2020[5]).The OECD has highlighted that proactive employment policies are particularly important in this crisis, as many young people face more acute social isolation that may hold them back from contacting public employment services or social services (OECD, 2020[6]). As lockdown measures continue to be enforced, many youth may also disengage from their job search as they become discouraged, placing them at risk of becoming economically inactive.

Figure 2.8. Youth unemployment rose more than the OECD average in Poland following the 2008 economic crisis

Source: OECD Regional Statistics.

2.2.4. Low-income employment and persons with low levels of education are an additional group at risk

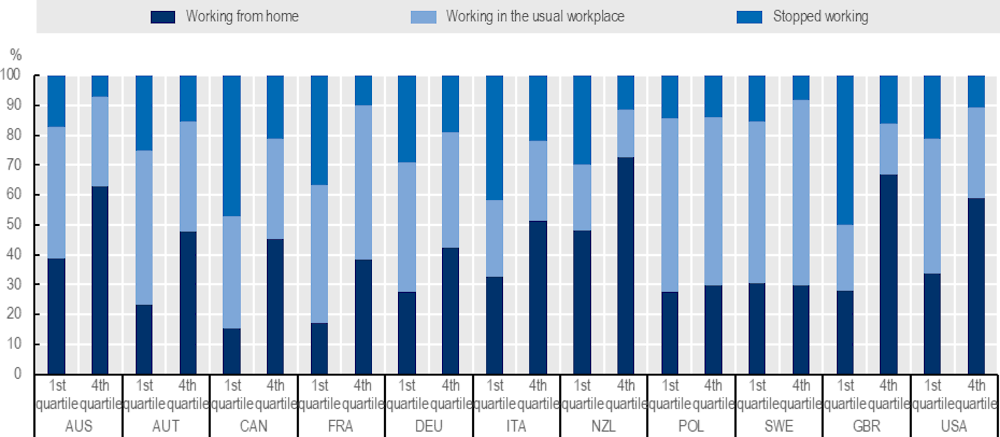

Similar to the 2008 economic crisis, many of those most affected by the downturn will be those who hold low-paid jobs (OECD, 2020[6]). Indeed, those with higher earnings (in the fourth income quartile) have been able to continue working from home in greater proportions across OECD countries (Figure 2.9). In the UK, for example, nearly half of those in the lower income quartile stopped working in April 2020, compared to 16% in the fourth income quartile. In Poland, however, the share of those who stopped working is smaller and stood at 14.5% of those in the lower income quartile, almost the same as those from the upper income quartile (14%). Compared to the majority of OECD countries, the share of those continuing to work from their usual workplace was much higher in Poland, 56% (first quartile) and 57% (fourth quartile). Greater flexibility and teleworking infrastructure could support working conditions and accelerate digitalisation across occupations and social classes.

Figure 2.9. Those with higher earnings were able to continue working in greater shares since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic

Source: Drawn from (OECD, 2020[6]); originally: Foucault and Galasso (forthcoming) based on the REPEAT (REpresentations, PErceptions and ATtitudes on the COVID-19) survey.

Pandemics may increase income inequality between those with lower levels of educational attainment and those with advanced degrees (Furceri et al., 2020[7]). Workers with lower levels of education are more vulnerable as they often hold less stable contracts, which facilitates dismissal during downturns. Those with advanced or technical degrees may also be able to regain employment more easily. Similarly, many young people are less attached to the labour market, with less work experience and less stable contracts (OECD, 2020[6]).

2.2.5. Polish regions are exposed differently to job loss from the COVID-19 pandemic

COVID-19 puts employment at risk differently across Polish regions. Different factors may determine the economic vulnerability of a region to both lockdown measures and the global economic downturn. For example, regions within Poland specialise in different economic activities, are exposed differently to global value chains and contain different shares of non-standard employment (OECD, 2020[8]). The OECD has developed a methodology to estimate the risk of job loss from COVID-19 based on calculating the share of jobs in sectors at risk due to lockdown measures (Box 2.1). Using this method, risk due to COVID-19 is found to vary by over 18 percentage points in Poland, from 25% in Greater Poland to 7% in Mazowieckie (Figure 2.10). The capital region contains a higher share of high-risk jobs compared to other regions, at 21%. All regions in Poland, however, face a lower risk due to COVID-19 compared to the OECD average of 27%.

The effects of COVID-19 on regional labour markets will also depend on policy action. Policy measures taken to slow the spread of the virus, social distancing measures and continued restrictions on targeted economic activities will all play a role (OECD, 2020[8]). Since March 2020, the Polish government has taken a variety of labour market measures to help protect jobs and promote economic activity under different levels of lockdown. These have included new measures to facilitate telework, supplemental sick leave, and a widespread Job Retention (JR) programme to cover 80% of employee wages (40% by the employer and 40% by the state) for enterprises losing at least 25% of revenue (OECD, 2020[9]). The duration and form of these support measures, in particular JR, will also determine the level of job loss in those sectors and occupations most at risk. Box 2.2 provides a brief discussion of COVID-19 economic response measures across the OECD.

Figure 2.10. COVID-19 puts employment at risk differently across Polish regions

Note: Share of jobs at risk is based on estimates of sectors most impacted by strict containment measures, such as those that involve travelling and direct contact between consumers and service providers. The sectoral composition of the regional economy is based on data from 2017 or latest available year. Regions displayed in Polish language, please refer to figure 1 for English translation.

Source: OECD calculations on OECD (2020), “Regional economy", OECD Regional Statistics, https://doi.org/10.1787/6b288ab8-en.

Box 2.1. How does the OECD approximate COVID-19’s impact on employment?

Detailed output categories reveal regions where jobs are most at risk

The OECD has calculated the impact of economic lockdown measures on different sectors. Based on the share of each sector in a region’s economy, the calculations reveal where regional employment is most vulnerable to lockdown measures. It is assumed measures are not region-specific. Using the ISIC-4 classification of economic activities, the sectors identified to be most at risk are the following:

Service sectors such as travel, including tourism, as well as those where direct contact with consumers is needed, such as hairdresser, face a near total shutdown in their activities under lockdown;

Retail, restaurants and cinemas are also affected, though takeaway and on-line sales where possible can maintain a degree of economic activity;

Non-essential construction faces activity limits, directly due to lockdown measures or indirectly through lower investment in the face of uncertainty and low demand;

Although manufacturing is less directly affected, governments have put in place integral shutdowns in certain industrial sectors, such as transport equipment.

In all economies, it is assumed full shutdowns take place in transport, manufacturing and other personal services, 50% shutdowns in output in construction and professional services, and 75% reductions in other output categories directly affected by lockdowns. These assumptions yield output reduction results. In all OECD economies, the majority of output reductions occur in retail and wholesale trade, as well as professional and real estate services.

Source: Adapted from (OECD, 2020[10]).

Box 2.2. COVID-19 economic response measures across the OECD

Poland has privileged wage subsidies over short-time work schemes while supporting SMEs

Countries across the OECD have taken unprecedented economic measures to help maintain the liquidity of firms and protect jobs and wages as governments put in place lockdown measures, and demand slumped. Two common measures include the use of liquidity support to firms and job retention schemes.

Supporting firms

Firms, and particularly SMEs, across OECD countries face liquidity crunches during lockdowns, putting firm solvency at risk. Governments have responded by providing emergency support to firms, through an “anti-crisis shield”. These support measures include:1

Deferrals in payroll tax and social security contributions;

Direct liquidity injections;

Direct subsidies based on past sales;

Employment subsidies;

And grants.

The Polish government put in place the Financial Shield, a EUR 22.7 billion (PLN 100 billion) combination of loans and subsidies to maintain both firm liquidity and protect jobs. The Polish Development Fund operates the programmes. Poland’s State Development Bank also participated by increasing its loan guarantees. Moreover, firms undergoing a sharp drop in revenue, in particular the self-employed and micro-enterprises, are eligible to defer their tax payments and temporarily suspend their social security contributions.

Protecting jobs

Job retention schemes seek to maintain an employee’s attachment to their employer during reduced activity by supporting labour costs for firms who had to reduce working hours of their employees. Countries across the OECD have used such schemes as a primary tool to protect jobs during the pandemic. In contrast with other European OECD countries, Poland has implemented wage subsidies rather than short-time work schemes to protect jobs during the crisis (Table 2.1). This may be due to less historical experience with such schemes, or the low costs of dismissing workers in Poland.

Table 2.1. Short-time work schemes and wage subsidies offer different approaches to protect jobs

|

Job retention programme |

Description |

Countries where measure is common |

Example |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Short-time work schemes |

Subsidies to firms to compensate workers’ wages for hours not worked. |

Continental Europe |

In Italy, the Cassa Integrazione Guadagni allows firms to apply for subsidies |

|

Wage subsidies |

Subsidies to firms to lower costs of labour or increase worker earnings. Typically, the size of the subsidy is independent of activity reduction. |

English-speaking countries, Netherlands, Poland |

In the Netherlands, the Emergency Bridging Measure (Noodmatregel Overbrugging Werkgelegenheid, NOW) |

Source: (OECD, 2020[11]), (OECD, 2020[6]), (OECD, 2020[12])

1. The measures discussed in Box 2.2 provide a high-level overview of the COVID-19 related economic policy measures implemented by the Polish government. A full list of measure implemented in Poland can be found on the European Commission’s designated website, see: https://ec.europa.eu/info/live‑work‑travel‑eu/coronavirus‑response/jobs‑and‑economy‑during‑coronavirus-pandemic/state-aid-cases/poland_en (accessed 22/06/2021).

2.2.6. Trade-related employment represents a risk across Polish regions

COVID-19 has caused unequal effects across economic sectors, exposing countries and regions differently. Some sectors most at risk from COVID-19 measures include accommodation and food services, air transport, art, entertainment and other services (OECD, 2020[8]). Lockdowns, social distancing measures and travel restrictions have led many of these establishments to close temporarily and to experience sharp drops in demand for their services. As of March 2021, multiple cultural and social sectors, such as theatres, cinemas and community centres, remained closed in Poland, while social distancing measures and travel restrictions remain in place (Government of Poland, 2021[13]).

While these sectors are facing a sharp downturn across Polish regions, the size of these sectors tends to represent a smaller share of jobs than in many other OECD countries. In regions of Greece, such as Crete, the South Aegean and Ionian islands, as well as Spain’s Balearic and Canary islands, the share of jobs at risk surpasses 40% due to a high share of tourism-related employment (OECD, 2020[8]). In Poland, meanwhile, in the most exposed regions, Greater and Lesser Poland, less than 25% of jobs are in at-risk sectors (Figure 2.11). In these regions, accommodation and food services represent 1.1% and 1.9% of jobs respectively.

Polish regions, however, are at risk due to their exposure to trade. COVID-19 has disrupted supply chains, increased trade uncertainty and reduced global trade (OECD, 2020[8]). On average, 10.3% of employment in Poland depends on trade (Figure 2.11).This varies from around 3% in Mazowieckie, to 15%, 11.6% and 10.5% in Greater Poland, Lesser Poland and Lower Silesia, respectively. Indeed, in Greater Poland, a relatively greater share of economic output depends on the region’s industrial base compared to the Polish average (European Commission, 2021[14]). The region is particularly specialised in machinery repair and production, a sector that was disrupted sharply by trade and transport restrictions in the first half of 2020, but that recovered nearly fully in the third and fourth quarters of 2020 (Eurostat, 2021[15]).

Figure 2.11. Employment in sectors exposed to trade reveals job vulnerability across regions

Note: Share of jobs potentially at risk estimated under condition of full lockdown and travel restrictions. The sectoral composition of the regional economy is based on data from 2017 or latest available year.

Source: OECD (2020), Coronavirus (COVID-19), From pandemic to recovery: Local employment and economic development, OECD Publishing, Paris. Original data from Eurostat -Regional Structural Business Statistics (sbs_r_nuts06_r2.).

2.2.7. Teleworking reinforces labour market resilience through the pandemic, but is only available for a minority

Polish regions tend to have fewer jobs amenable to telework than the OECD average. This may detract from economic resilience during lockdowns and social distancing measures linked to COVID-19 or other future pandemics. In over half of Polish regions, the share of jobs amenable to teleworking is lower than the OECD average of 32% (Figure 2.12). In Warsaw capital city, the country’s capital region, 48% of jobs are amenable to teleworking, a share greater than across all other Polish regions and the OECD average. In response to low teleworking capacities, regions across OECD countries have taken action to support the transition to telework by providing the guidance and digital infrastructure necessary to make the transition (Box 2.3).

While telework strengthens a region’s resilience to COVID-19 by maintaining employment through lockdown measures, it also reveals labour market inequalities. In 2007, Poland modified its labour code to formalise remote work arrangements. The new legislation set out legal structures concerning telework, including access to training, working conditions and privacy, helping prepare the country for large-scale teleworking during the pandemic (Eurofound, 2007[16]). Those jobs most amenable to telework also tend to be higher skill jobs, which helps explain variation across Polish regions. A recent survey in the European Union (EU) found that nearly three-quarters of workers with tertiary education worked remotely (Eurofound, 2020[17]). Remote work has also been facilitated in sectors with a high share of telework before the pandemic. For example, around 40% of IT and communication service workers were estimated to have already worked remotely regularly or with some frequency before the pandemic (JRC, 2020[18]).

The shift to large-scale teleworking, however, also offers opportunities for inclusion of disadvantaged groups. The pandemic has demonstrated teleworking can replace on-site work for many occupations. For groups such as workers with disabilities, this is an opportunity for better working conditions and better labour market access. Indeed, voluntary teleworking for this group can allow employers to better utilize the strengths of such employees by allowing them to meet their needs in a tailored workspace (Eurofound, 2020[19]).

Teleworking has also been linked to fertility decisions in highly educated women. Beyond COVID-19, broadband access and the option to engage in work from home has been shown to increase the fertility of highly educated women aged between 25 and 45 (Billari, Giuntella and Stella, 2019[20]). In light of the depopulation Poland faces (see Figure 2.14) teleworking is therefore not just a short-term solution to prevent unemployment during a pandemic, but may also present a policy option to counteract ageing societies.

Figure 2.12. The share of jobs amenable to telework is below the OECD average in most Polish regions

Note: Share of jobs amenable to teleworking is based on the types of tasks performed in different occupations, and the share of those occupations in regional labour markets. These figures do not account for gaps in access to IT infrastructure across regions, which could further restrict teleworking potential. The OECD median presented here is the median of OECD regions with available data for each indicator.

Source: OECD (2020), OECD Regions and Cities at a Glance 2020, https://doi.org/10.1787/959d5ba0-en.

Box 2.3. How the Basque Country (Spain) supports SMEs to upscale remote work capacity

How can governments support teleworking for local resilience?

In the Basque Country (Spain), the government’s industrial development organisation, SPRI, put in place multiple programmes to support the region’s SMEs to take up teleworking since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. In particular, the INPLANTALARIAK programme dispenses advice for Basque SMEs and independent workers on how to best upscale or adapt their activities to remote work. The programme, started before the pandemic, encourages telework though a broader series of actions:

Open new avenues for sales through digital means;

Advertise digitally;

Interact digitally with clients;

Save on costs and time through tools which simplify or eliminate repetitive tasks;

Increase efficiency by supplying means for teleworking and online collaborative work;

Put in place a flexible office location though remote connection;

Increase mobile office tools through better use of smartphones;

Reinforce cybersecurity;

Introduce new technologies such as virtual reality where useful.

In March 2020, INPLANTALARIAK and other programmes were funded with over EUR 45 million to support local SMEs through the crisis. Firm digitalisation becomes a way to protect worker safety as COVID-19 endures, allowing operations to continue through social distancing and lockdown measures.

2.3. The pandemic could push disadvantaged individuals into economic inactivity

While COVID-19 presents primarily a short-term labour market shock, the repercussions may be long-term if individuals permanently drop out of the labour force. This section highlights these dynamics and shows that COVID-19 disproportionally affected groups with a lower labour market attachment to begin with, potentially leading to higher transition rates into economic inactivity.

2.3.1. Making the link: COVID-19, disadvantage and economic inactivity

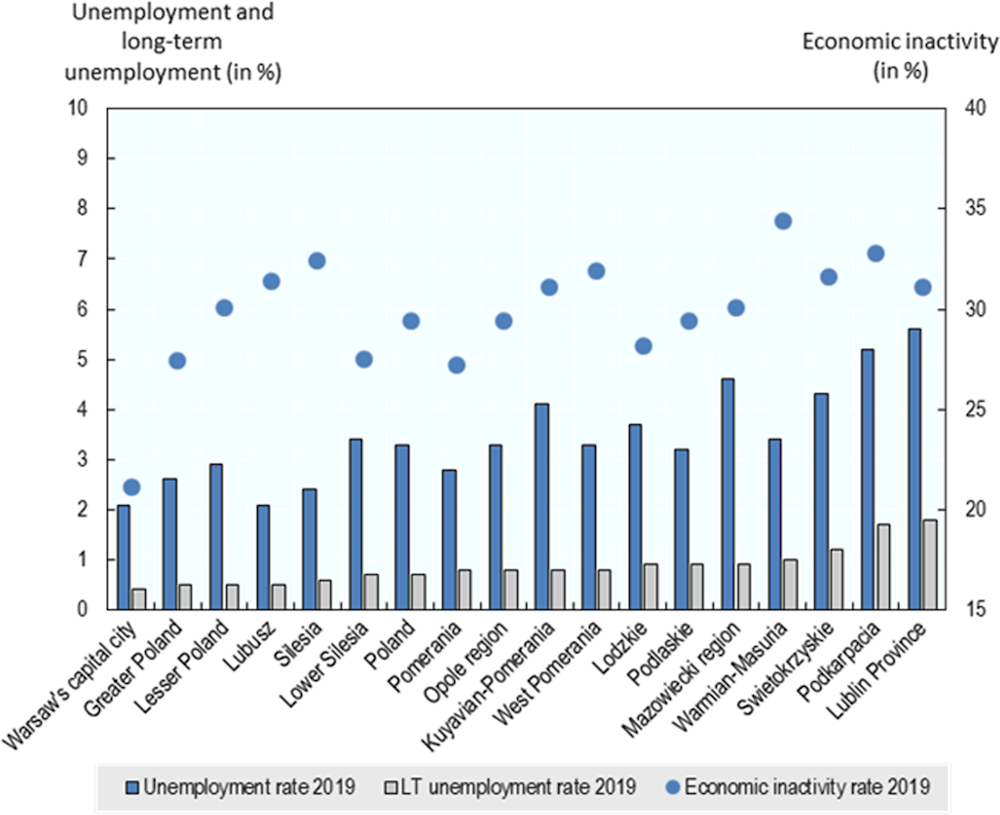

Regions in Poland with higher levels of unemployment also show higher levels of economic inactivity. Figure 2.13 shows regional differences in Poland’s unemployment, long-term unemployment and economic inactivity rates in 2019. For example, the unemployment rate stood at 2.1% in the capital city of Warsaw, the long-term unemployment rate at 0.4% and the economic inactivity rate at 21.1%. In Podkarpacia, these numbers stood at 5.1%, 1.7% and 32.8%. Labour market indicators are correlated across most Polish regions.

The COVID-19 pandemic may compound shifts from unemployment to long-term unemployment and into economic inactivity. At any point in time, some unemployed individuals become long-term unemployed and some long-term unemployed become economically inactive. The labour market shock brought about by COVID-19 makes it more difficult for individuals who were already unemployed pre-pandemic or lost their job early on during the pandemic to find employment, with the risk of a transition into long-term unemployment and possibly economic inactivity. This dynamic has been well documented in the United States (Coibion, Gorodnichenko and Weber, 2020[23]). Thus, the COVID-19 pandemic risks to leave longer-lasting scars on the labour force.

Figure 2.13. The link between unemployment, long-term unemployment and economic inactivity

Note: The left y-axis shows regional unemployment rates and regional long-term unemployment rates of the working age population in the labour force in 2019. The right y-axis shows economic inactivity rates in 2019.

Source: OECD Regional Database.

Workers who lose their jobs during an economic crisis are likely to suffer from the "scarring effects". Scarring refers to the negative long-term effect that unemployment has on future labour market possibilities. Evidence from earlier recessions shows that workers who lose employment during a recession suffer from negative labour market experiences in the future (e.g., shorter contracts, lower hourly wages, and so on), compared to an otherwise identical individual who has not been unemployed (Davis and von Wachter, 2011[24]).

Those facing less stable labour market attachment tend to face the most long-term economic and social consequences from economic crises (OECD, 2020[25]). The COVID-19 pandemic is likely to compound disadvantages for certain groups, in particular for:

Low-wage workers;

Those with lower levels of education;

Women;

Youth;

And those most excluded from the labour market more generally.

The COVID-19 pandemic presents specificities that are likely to further accentuate disadvantage. Essential and frontline workers have faced higher risks of exposure to COVID-19. This includes groups of workers such as cashiers, nurses and personal service workers. On the other hand, non-essential low-wage workers in service jobs that require face-to-face contact are unable to work from home and have been pushed into job retention schemes or have lost their jobs. This includes many workers in food services, accomodation, culture and entertainment who face ongoing lockdowns in many OECD countries. Those sectors most impacted by COVID-19 also tend to contain a relatively larger share of women (OECD, 2020[6]).

2.3.2. Before COVID-19, economic inactivity was higher than the OECD average in Poland

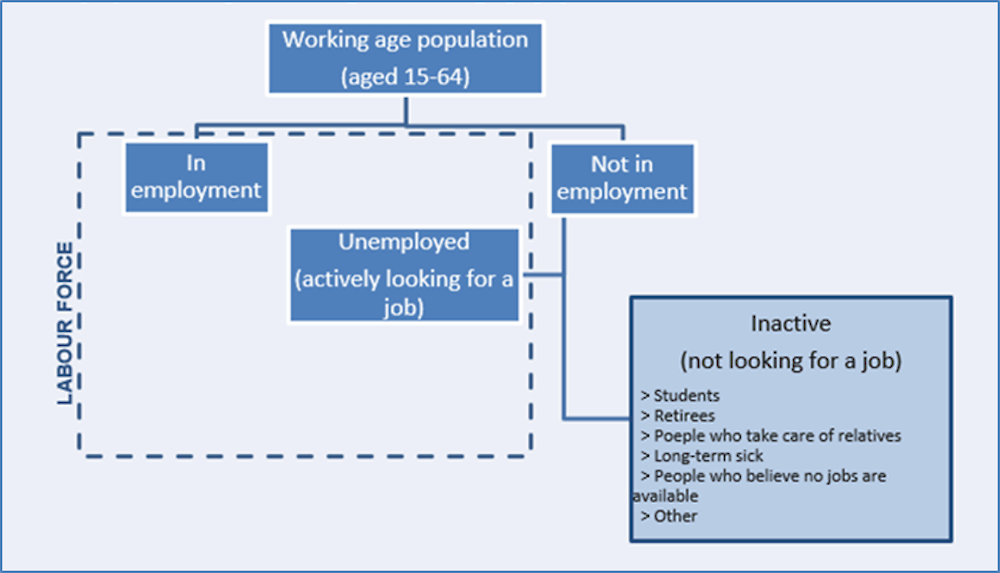

Since 2007, economic inactivity had progressively decreased across the OECD. Economic inactivity can be defined as the proportion of the working-age population that is not in employment, nor looking for work (ILO, 2016[26]). This category of individuals falls outside those recorded as unemployed, people of working age who are without work, are available for work, and have taken specific steps to find work. Measuring economic inactivity helps garner a more comprehensive picture of labour market inclusivity by revealing those who are of working age but are not in employment (Barr, Magrini and Meghnagi, 2019[27]). Economic inactivity, however, encompasses a large array of individuals, from students and retirees to those with disabilities or discouraged from seeking work (Box 2.5).

Economic inactivity is the opposite of the labour market participation rate. Labour force participation is the share of the labour force out of the total working age population (15-64 years). The OECD defines the labour force, or currently active population, as all persons who fulfil the requirements for inclusion among the employed (civilian employment and armed forces) or the unemployed (OECD Statistics).

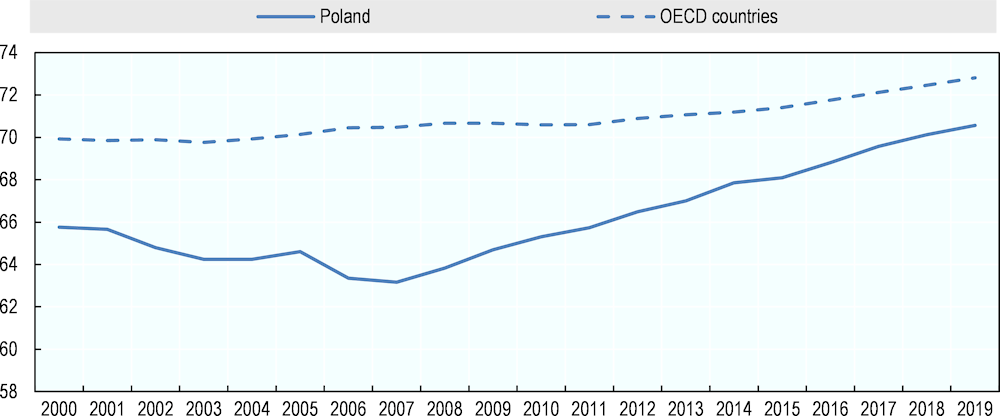

In Poland, labour force participation has increased and inactivity decreased, mirroring OECD trends. Labour force participation among 15 to 64 year olds increased by 4.8 percentage points between 2000 and 2019, from 65.8% to 70.6% (Figure 2.15). Across the OECD, rising participation is associated with the economic recovery from the 2008 crisis, as well as greater participation of older people and women across most member countries (OECD, 2019[28]). In Poland in particular, the pension reforms played a role in increasing the employment rate of the older part of the workforce by raising the statutory retirement age (OECD, 2018[2]). Despite these trends, a larger share of the working age population in Poland is inactive compared to most OECD countries. In 2019, 29% of the population was economically inactive, compared to an OECD average of 27% (Figure 2.16). The reversal of the reform on the statutory retirement age, which took effect in 2017, is likely to have a negative effect on labour force participation (see Box 2.4).

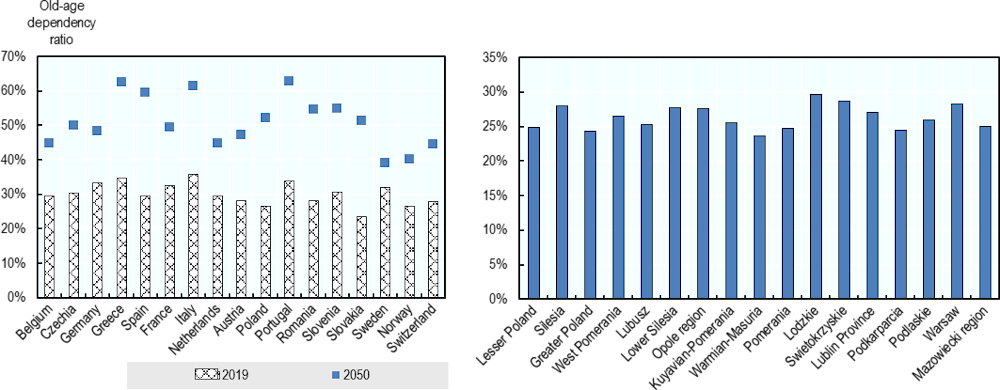

Box 2.4. Statutory retirement age in Poland

The pension age in Poland is 65 years for men and 60 years for women. In 2013, the Polish parliament passed a reform that would gradually increase the statutory retirement age to reach 67 years for both sexes. The parliament decided in November 2016 to reverse that increase in retirement age. The reform reversal took effect in October 2017, effectively decreasing the statutory retirement age by 14 months (OECD, 2017[29]). Poland is the only OECD country next to Switzerland and Israel to have a different statutory retirement age for men and women.

There is no legal requirement for workers to stop working when they reach the statutory requirement age and deferring retirement is to some extent incentivised (OECD, 2018[30]). The Polish government is among few in the OECD that does not allow employers to set a maximum retirement age to prevent forced retirement. Deferring pension claims has direct advantages to those who decide to do so: On average, it leads to a pension benefit increase of around 6% (OECD, 2017[29]). It is further possible to combine work and pension receipt to leave the labour market gradually (OECD, 2019[31]).

However, to many workers, the statutory pension acts as a focal point and thereby affects retirement decisions (Cribb, Emmerson and Tetlow, 2016[32]). In Poland, the 2017 statutory retirement age reversal is associated with an immediate decrease in the retirement age among women.

The low retirement age is likely to exacerbate the issue of increasing pressure on the pension system brought about by Poland’s ageing society. In 2019, Poland’s old-age dependency ratio stood at 26.4%, right at the OECD average, with little regional variation. Like in many other European countries, this ratio is projected to increase rapidly and reach 52.2% by 2050 (see Figure 2.14).

Figure 2.14. Old-age dependence ratio

Note: The left panel shows the old-age dependency ratio of Poland and selected European countries in 2019 and 2050 (projected). The right panel shows the old-age dependency ratio by Polish TL-2 regions in 2019.

Source: Eurostat (PROJ_19NDBI) and OECD Regional Database (Regional Demography: Demographic Composition and Evolution).

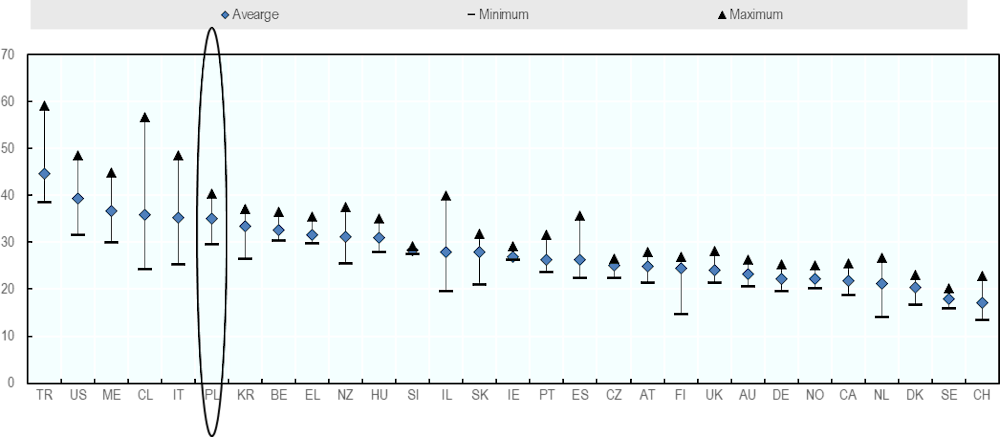

Economic inactivity also has a strong regional dimension in Poland. In Poland, economic inactivity differs between regions by 13.3 percentage points in 2019, ranging from 21.1% in the Warsaw capital region to 34.4% in Warmian-Masuria. Figure 2.17, which graphs the gap between the region with the lowest and the highest economic inactivity rate for 2016 (the year when comparable data is available for all OECD countries), shows that the gap of 10.9 percentage points was slightly higher than the OECD average of 10.7 percentage points at the time.

In countries with larger variations in economic inactivity across regions, local characteristics may be closely related to the nature and degree of economic inactivity. Local demography may influence the scale of economic inactivity (Barr, Magrini and Meghnagi, 2019[27]). For instance, a region’s large university or retiree population may account for a larger share of the economically inactive. On the contrary, local labour market characteristics may discourage certain people from seeking work. For example, the absence of quality jobs or those that correspond to local skills may discourage people from job searches.

Figure 2.15. Although rising, labour force participation trails the OECD average

Source: OECD Statistics.

Figure 2.16. Economic inactivity was higher in Poland relative to most OECD countries before COVID-19

Note: Thousands of persons, ratios in percentage, and growth rates (all raw and seasonally adjusted). Chile and OECD are estimates.

Source: OECD Statistics.

Figure 2.17. Economic inactivity has a regional dimension in Poland

Note: Data refers to the 15-64 population in 2016 as regional data for the age group 25-54 or more recent data is not yet available for all OECD countries.

Source: Drawn from (Barr, Magrini and Meghnagi, 2019[27]), originally from "Regional labour markets", OECD Regional Statistics (database), https://doi.org/10.1787/f7445d96-en.

Box 2.5. How does the OECD measure economic inactivity?

The situation and degree of labour market attachment varies among economically inactive persons. For example, the economically inactive caring for relatives, engaged in unpaid internships and other unpaid work activities are not counted as members of the labour force, although they may also be closely linked to the labour market (ILO, 2019[33]). To make distinctions, labour force surveys generally classify economically inactive people into the following categories (Figure 2.18):

Students;

Retirees;

People who take care of relatives;

People who have health issues or disability;

People who believe there are no jobs available (discouraged workers)l and

And people who are not looking for a job for other reasons.

A large share of this group, such as retirees and students, are most likely inactive by choice. Others who are not looking for work or employment, however, may be willing to work under certain conditions. This difference highlights the importance of focusing on the prime working age population, as they are less likely to be inactive by choice (Barr, Magrini and Meghnagi, 2019[27]). Those that are not outside of the labour market by choice can suffer social exclusion, detracting from social cohesion, and presenting a missed opportunity for firms facing labour shortages.

Figure 2.18. Classifying the economically inactive based on labour force surveys

2.3.3. Older working age people characterise the economically inactive population in Poland

As across the OECD, different factors drive economic inactivity in Poland. Some economically inactive working age people choose not to participate in the labour market (Barr, Magrini and Meghnagi, 2019[27]). For example, students and retirees do not participate in the labour market as they have yet to enter the labour market durably, or have finished their working life. Others, meanwhile, cannot enter the labour market due to disability or other personal circumstances, such as child or elderly care. For this group, providing them with social services is a step towards their integration of the labour market (Box 2.6).

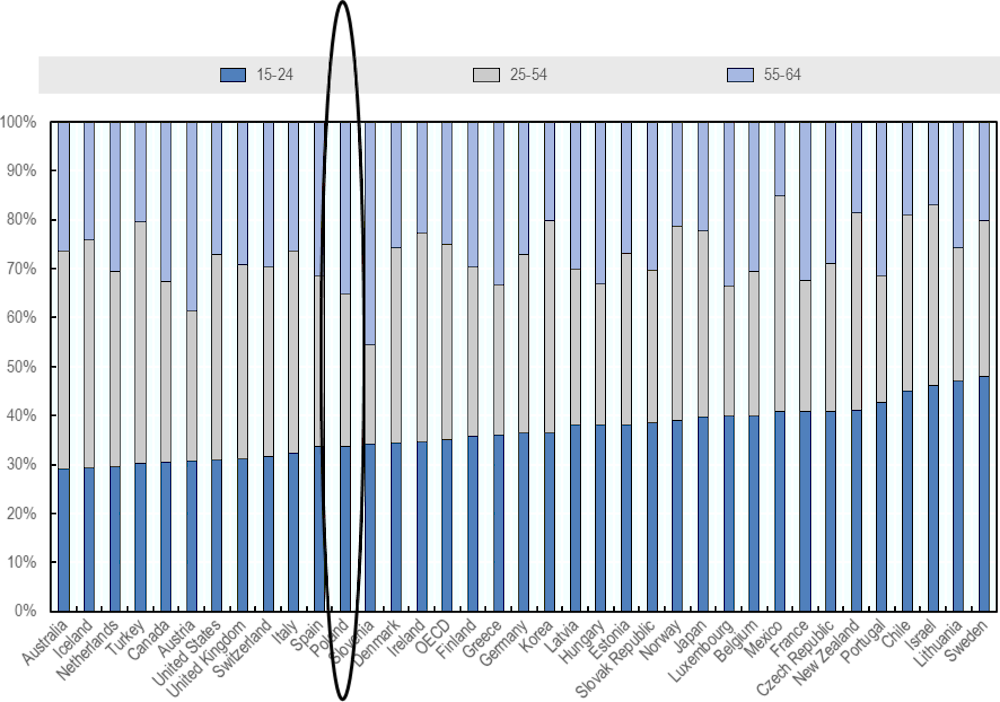

In Poland, older working age is an important characteristic of economically inactive people. Indeed, in 2019, the share of economically inactive people between 55 and 64 years old represented 35% of the economically inactive population in Poland, compared to over 32% and just under 34% of those aged 25-54 and 15-24 respectively. Figure 2.19 shows these data in international comparison for 2017. The share of older economically inactive people is over 10 percentage points greater than the average across OECD countries, and third highest in the OECD, after Slovenia and Austria, where nearly 47% and 39% of the older working age cohort is economically inactive.

Poland’s economic history may partially explain the persistence of an older age cohort of economically inactive people. As Poland engaged in its economic transition, early retirement schemes were encouraged to accelerate the restructuring of certain economic sectors, which may have shaped a lasting pattern (Polakowski and Hagemejer, 2018[34]). Other countries that underwent economic transition in the 1990s and 2000s also have a relatively high share of economically inactive people between 55-64 years old. In Slovenia and Hungary, around 46% and 33% respectively of economically inactive are in the older age cohort (Figure 2.19). As Poland engaged in pension reforms in 1998 and 2012, the country gradually raised the retirement age and incentivized later retirement, which may have contributed to lowering the rate of inactivity among older working age people since the start of the 2010 decade.

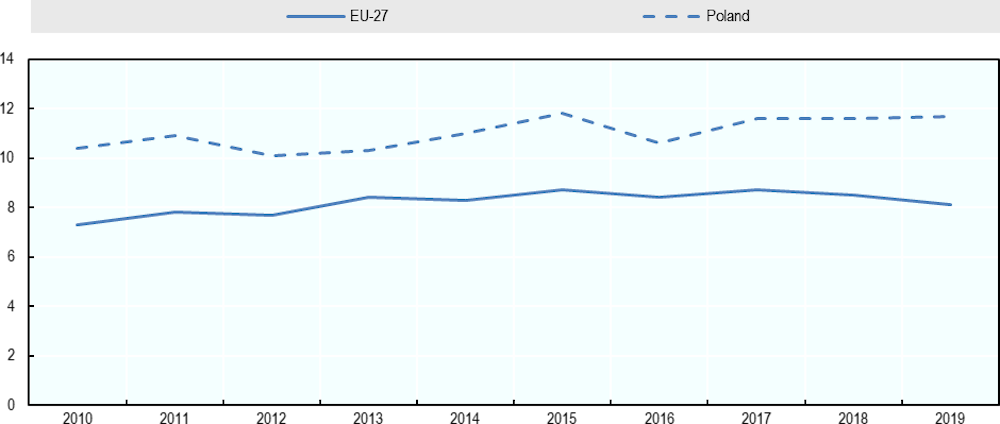

Evidence suggests, however, that part of this group has struggled to make the transition into quality work. The share of those aged 55 to 64 in-work but at risk of poverty increased by 1.3 percentage points, from 10.4% in 2010 to 11.7% in 2019 (Figure 2.20). In the European Union (EU-27), this share increased by 1 percentage points, from 7.1% to 8.1% in the same time period. These figures may indicate retirement reforms have incited older working age people to stay or reintegrate the labour market. Given the dynamic job growth in Poland, this suggests that a better transitions from early retirement back to work, or late career transitions, may help reinforce social cohesion in the labour market. Targeted support, skills mapping and adult learning policies could be particularly helpful to accompany late working age transitions, reducing economic inactivity.

Figure 2.19. In Poland, the economically inactive tend to draw from an older age cohort compared to OECD countries

Note: Data originally drawn from OECD Labour Market Statistics database, 2019.

Figure 2.20. In Poland, a share of the older working age cohort struggles to find decent work

Note: Data drawn from EU-SILC survey. EU-27 is an estimate and refers to the 2007-2013 EU-27 countries.

Source: Eurostat [hlth_dpe050]

Box 2.6. In France, the cheque emploi service universel (CESU) provides tailored home services

By providing child care, mobility help or other services, CESU facilitates job access for the economically inactive.

In 1994, the French government launched the cheque emploi service in order to stimulate the growth of home services for the elderly, people with disability and those in need. In 2006 and 2020, the measure was expanded and refined. The CESU works as a cheque dispensed by an individual to pay for personal services, granting the employer certain tax advantages, such as reductions in social security contributions. CESU can be used to hire nationally-accredited service providers. CESU facilitates payment, provides economic benefits for the employer and encourages the declaration of personal services. Importantly, local social centres run by French communes, Centre communal d'action sociale (CCAS), also provide pre-financed CESU to those individuals meeting economic and disability criteria. CESU can finance an array of personal services, such as:

Personal services for the elderly and people with disabilities;

Child care ;

Mobility assistance;

Home care;

IT and communication support.

As of 2017, 2.2 million people in France used CESU for the services of nearly 950 000 personal service workers. CESU is not specifically an employment activation measure, as it tends to support those over 70 years old who require assistance. CESU, however, can facilitate access to the labour market specifically for those who cannot work due to personal circumstances.

How the CESU facilitates labour market access for economically inactive people who would like to work

A share of economically inactive people would be willing to search for work if the right conditions were in place. For example, many women with child or elderly care responsibilities may re-enter education or training or seek career opportunities if elderly or relatives with a disability or children could be taken care of during the day. The CESU offers a model to support this group of people, while also developing a key personal service sector, increasingly in demand in ageing societies. Moreover, the CESU can directly support elderly individuals or those with disabilities by supporting their home care. Particularly for those with low income, pre-financed cheques grant them access to a key service to access employment services that will prepare them for the labour market. With the large-scale development of telework triggered by COVID-19, programmes such as CESU may also create new bridges for socio-economic integration of those with disabilities or facing attenuating circumstances to have IT and communication services deployed in their home along with care services. Beyond access to economic opportunities, CESU can also provide a bridge to wider social integration through internet access and mobility support.

2.3.4. Those with lower levels of education have struggled to benefit from rising labour market participation, exposing them further to the COVID-19 labour market downturn

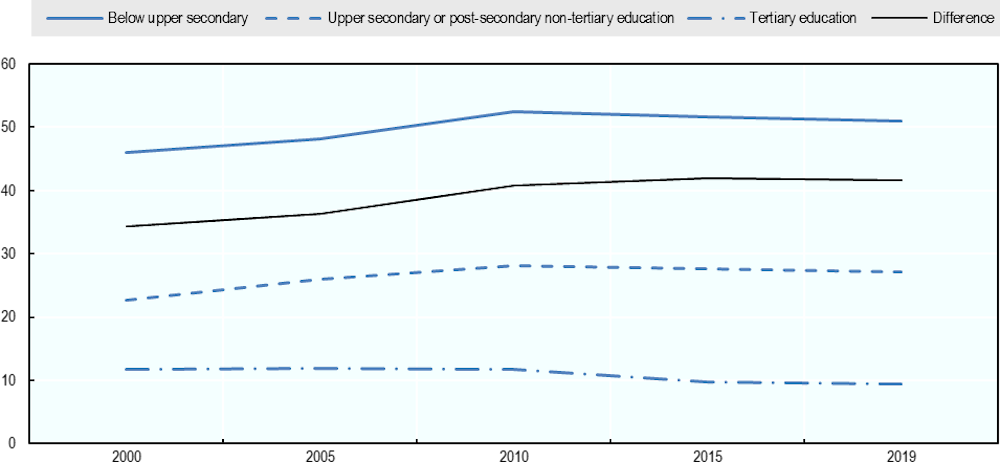

Higher educational attainment corresponds with lower levels of economic inactivity in Poland. Across the OECD, higher educational attainment supports economic activity. Those who acquire higher levels of skills and garner work experience are less likely to be inactive (Barr, Magrini and Meghnagi, 2019[27]). In Poland, between 2000 and 2019, the share of the economically inactive population between 25 and 64 with tertiary education decreased by over two percentage points, from 11.7% to 9.4% (Figure 2.21). For those with upper secondary or post-secondary non-tertiary education, the share increased by 4.4 percentage points, from 22.7% to 27.1%. The share increased by an even greater proportion between 2000 and 2019 for those with below upper secondary education, increasing by 4.9 percentage points, from 46.1% to 51%.

Inequalities in economic inactivity between those with tertiary education and those with lower levels of educational attainment are growing in Poland. Indeed, the difference in economic inactivity rates between those with below upper secondary education and tertiary education has increased by 7.3 percentage points between 2000 and 2019, from 34.4 percentage points to 41.7 percentage points (Figure 2.21). Multiple factors could explain this growing labour market inequality, including the increasing shift towards jobs that are more accessible opportunities to those with tertiary education. In France, the renewed pilot project Territoires zéro chômeurs de longue durée is based on activating passive spending for those in long term unemployment or inactive who want to work (Box 2.7). Candidates frequently have low levels of education and face disability. The project offers interesting lessons for Poland. The OECD has also highlighted that relatively weak access to adult learning may be leaving many older people with lower levels of educational attainment without the skills to take advantage of labour market opportunities (OECD, 2019[37]).

Figure 2.21. The inactivity gap between people with the highest and lowest levels of education is rising in Poland

Note: Difference is between below upper secondary and tertiary levels of educational attainment.

Source: Data extracted on 04 Feb 2021 17:39 UTC (GMT) from OECD.Stat, Educational attainment and labour-force status: Employment, unemployment and inactivity rate of 25-64 year-olds, by educational attainment.

Box 2.7. The Territoires zéro chômeurs de longue durée pilot in France

How local actors can mobilise to integrate those economically inactive into sheltered employment

In 2017, France launched the pilot project Territoires zéro chômeurs de longue durée (TZCLD), or zero long term unemployed territories, which integrates those out of work for long periods onto the labour market. TZCLD recruits those among the most excluded from the labour market, the group of economically inactive people who are able to work. TZCLD is based on the work of multiple actors, from both the national and local level, driving its emphasis on matching local skills with local needs:

The French state and local government co-finance the TZCLD fund, which is used to support Entreprises à but d’emploi, or social purpose enterprises.

Local committees made up of local organisations, government representatives, local business representatives, social partners and other local actors identify available skills among the long-term unemployed in the territory. They also identify unmet needs among social purpose enterprises. Committees also analyse the local labour market to ensure social purpose enterprises do not present unfair competition to local firms.

Social purpose enterprises develop activities and recruit candidates presented by local committees. Candidates are recruited on open-ended contracts. The quality of work and contracts is an important element of the pilot.

Economically inactive people express their interest in working, as well as their desired working hours.

The TZCLD organisation organises the overall project’s development and steers its implementation in new territories. The organisation also accompanies territories in implementation, helps evaluate the project’s outcomes and supports the project’s diffusion.

TZCLD’s financing model is based on transferring passive social benefits for those economically inactive into wages inside local organisations. The employment offered to those excluded from the labour market allows participants to acquire new skills with the objective of integrating the open labour market in the future. Social enterprises must ensure that participants receive new skills, professional mobility and access to lifelong learning. In 2020, the pilot project was renewed and extended to fifty new French territories.

2.3.5. Women are particularly vulnerable to labour market exclusion in Poland

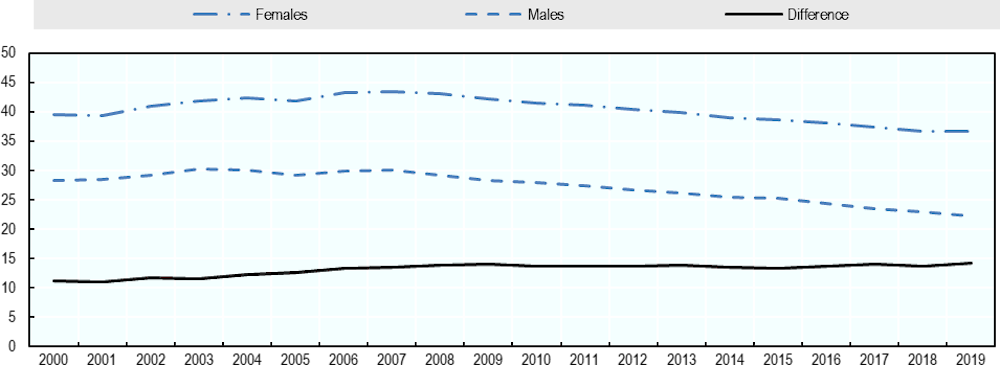

Women are more represented than men among economically inactive people in Poland. This proportion of economically inactive women is 1.7 percentage points higher than the average across OECD countries. Women participate significantly less on the labour market than in many European member countries. Between 2000 and 2019, the share of economically inactive women in Poland decreased by 2.8 percentage points, from 39.5% of the population between 15 and 64 years old, to 36.6% (Figure 2.22).

Inactivity rates suggest inequalities of access to labour market opportunities between men and women may be growing. As the economic inactivity of men decreased from 28.4% of the population between 15 and 64 years old to 22.3%, the difference in labour market participation between men and women increased from 11.2 percentage points to 14.3 percentage points between 2000 and 2019. These differences may have increased with the COVID-19 pandemic, as women face a dual labour market consequence: greater childcare responsibility in the face of school closures, as well as greater presence in the most affected sectors by the pandemic (Box 2.8).

Multiple factors may explain the relatively high economic inactivity of women in the country. Compared to EU-27 countries, research suggests care for children or incapacitated adults is a stronger driver of economic inactivity for women, as is the case for over 47% of women between 25 and 49 years old in Poland compared to under 40% across the EU (Matuszewska-Janica, 2018[39]). Indeed, limited options in and access to childcare and long-term care may push many women to stay home to care for young children, elderly parents or those with special needs (European Commission, 2020[40]). A share of these women may prefer to work if public services became more available for care and transportation. A lack of child friendly policies in many workplaces, such as rigidity in working hours for parents or carers to accommodate for family responsibilities, may also discourage women from professional opportunities (OECD, 2016[41]). Beyond childcare, retirement and own disabilities play a strong role for older women in Poland (Matuszewska-Janica, 2018[39]).

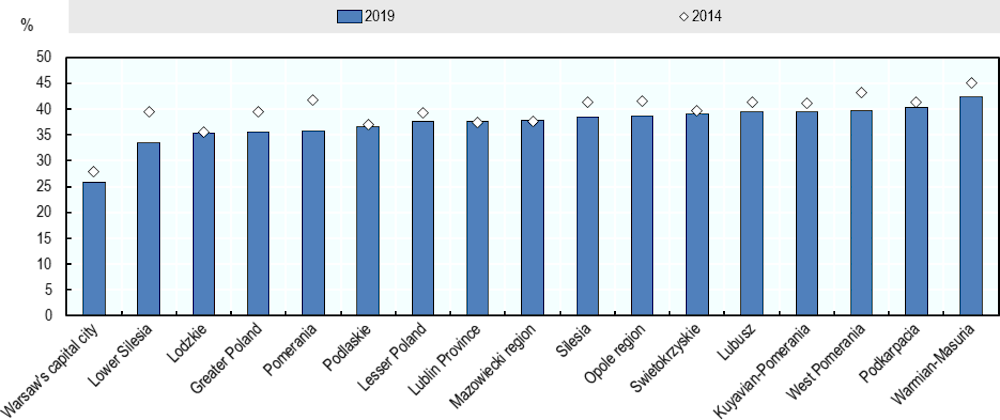

The share of women not participating in the labour market also varies across Polish regions. In 2019, those regions where women participated most in the labour market included Warsaw, Lower Silesia and Lodzkie, where the share of economically inactive women was 25.8%, 33.4% and 35.3% respectively (Figure 2.23).These regions tend to be more economically developed, and house large cities. The evolution of the labour market participation of women also differs across regions. In almost half of Polish regions, inactivity rates of women decreased by over 2 percentage points between 2014 and 2019. In Lublin Province and Mazowiecki region, however, economic inactivity rates of women increased slightly, by 0.2 percentage points.

Figure 2.22. The difference in economic inactivity between men and women has increased in Poland since 2000

Note: Inactivity rates calculated based on Participation Rate 15-64 (% labour force 15-64 over population 15-64). Data extracted on 03 Feb 2021 from OECD.Stat.

Source: OECD Regional Database.

Figure 2.23. Although falling, some regions still struggle to decrease the share of women who are economically inactive

Note: Economic inactivity calculated based on the labour force participation rate.

Source: OECD Regional Database. Data extracted on 16 Feb 2021.

Box 2.8. COVID-19 will compound labour market exclusion of vulnerable women

Women are particularly vulnerable to the increased childcare responsibilities brought by the pandemic

The OECD has identified multiple factors which increase the labour burden on women as the COVID-19 pandemic unfolded.

First, women are playing a frontline role in the response to COVID-19. Across the globe, women constitute two-thirds of the health case workforce and make up the large majority of long-term care workers. This is likely to degrade working conditions, and expose them to greatest socio-professionals risks as well as infection.

Second, a large share of women have faced an increased unpaid child care burden as schools closed across OECD countries.

Third, many of the sectors facing the strongest downturn are composed of a large female workforce. For instance, those sectors involving higher human interaction, such as accomodation services and retail. Across sectors, women also tend to face less stable working conditions, such as temporary contracts, exposing them doubly to the risk from a downturn.

Finally, women face lower pay and hold less wealth to support them in case of economic insecurity.

As these factors continue to weigh on the female labour force, they may prevent many women from seeking professional opportunities. In Poland, this dynamic is likely to weigh particularly heavily on female workers because of the high proportion of women already declaring childcare responsibilities as a reason for staying outside of the labour market.

Source: (OECD, 2020[6]), originally from (OECD, 2020[42]).

Conclusion

COVID-19 could exacerbate labour market disadvantage for those groups that are already the most vulnerable. Mothers, those with lower levels of education and young people face less stable labour market situations, and tend to be employed in large shares in service sectors that are particularly vulnerable to the downturn. Even before the pandemic, economic inactivity was high in Poland, and inequalities were growing between men and women and those with different levels of education. With the COVID-19 labour market downturn, caring responsibilities, interrupted education and discouragement from job search may lead these groups to disengage from the labour market, harming their economic well-being.

Poland can turn to international examples to ensure these groups are the focus of recovery policies. Teleworking capacity can be expanded in Poland, as can sustained support for youth to integrate into the labour market. Poland’s dynamic labour market can serve as a tool to expand training, social support and activation pathways for those with specific needs to find and hold work. Chapters 2 and 3 will delve further into the causes of economic inactivity in Poland, and explore its regional dimensions.

References

[38] Association territoires zéro chômeur de longue durée (2021), Les fondements, https://www.tzcld.fr/decouvrir-lexperimentation/les-fondements/.

[27] Barr, J., E. Magrini and M. Meghnagi (2019), Trends in economic inactivity across the OECD: the importrance of the local dimension and a spotlight on the United Kingdom, OECD Local Economic and Employment Development (LEED) Papers, https://doi.org/10.1787/20794797.

[20] Billari, F., O. Giuntella and L. Stella (2019), “Does broadband Internet affect fertility?”, Population Studies, Vol. 73/3, pp. 297-316, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00324728.2019.1584327.

[36] CCAS-RAPT (2020), L’aide au maintien à domicile, https://www.ccas-ratp.fr/lfy/aide-au-maintien-a-domicile.

[23] Coibion, O., Y. Gorodnichenko and M. Weber (2020), Labor Markets During the COVID-19 Crisis: A Preliminary View, National Bureau of Economic Research, Cambridge, MA, http://dx.doi.org/10.3386/w27017.

[32] Cribb, J., C. Emmerson and G. Tetlow (2016), “Signals matter? Large retirement responses to limited financial incentives”, Labour Economics, Vol. 42, pp. 203-212, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.labeco.2016.09.005.

[24] Davis, S. and T. von Wachter (2011), Recessions and the Cost of Job Loss, National Bureau of Economic Research, Cambridge, MA, http://dx.doi.org/10.3386/w17638.

[19] Eurofound (2020), COVID-19 How to use the surge in teleworking as a real chance to include people with disabilities, https://www.eurofound.europa.eu/fr/publications/blog/how-to-use-the-surge-in-teleworking-as-a-real-chance-to-include-people-with-disabilities.

[17] Eurofound (2020), Living, working and COVID-19, https://www.eurofound.europa.eu/sites/default/files/ef_publication/field_ef_document/ef20059en.pdf.

[16] Eurofound (2007), Telework in Poland, https://www.eurofound.europa.eu/publications/article/2007/telework-in-poland.

[14] European Commission (2021), Regional Innovation Monitor Plus, Wielkopolska, https://ec.europa.eu/growth/tools-databases/regional-innovation-monitor/base-profile/wielkopolska.

[40] European Commission (2020), Country Report Poland 2020, 2020 European Semester: Assessment of progress on structural reforms, prevention and correction of macroeconomic imbalances, and results of in-depth reviews under Regulation (EU) No 1176/2011, {COM(2020)150final}, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:52020SC0520&from=EN.

[35] European Social Network (2006), Social and employment activation, a briefing paper by the European Social Network, https://www.esn-eu.org/sites/default/files/publications/Social_and_Employment_Activation.pdf.

[15] Eurostat (2021), Impact of Covid-19 crisis on industrial production, https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php/Impact_of_Covid-19_crisis_on_industrial_production.

[7] Furceri, D. et al. (2020), COVID-19 will raise inequality if past pandemics are a guide, https://voxeu.org/article/covid-19-will-raise-inequality-if-past-pandemics-are-guide.

[22] Gobierno Vasco (2021), Servicio de Asesoramiento e Implantación de tecnologías para la Transformación digital que apoye a la reactivación de Micropymes y autónomos de Euskadi, https://www.spri.eus/euskadinnova/es/portada-euskadiinnova/soluciones-para-micropymes/587.aspx.

[13] Government of Poland (2021), Coronvirus: information and recommendations. Temporary limitations., https://www.gov.pl/web/coronavirus/temporary-limitations.

[33] ILO (2019), Persons outside the labour force: How inactive are they really? Delving into the potential labour force with ILO harmonized estimates, https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---dgreports/---stat/documents/publication/wcms_714359.pdf.

[26] ILO (2016), Key indicators of the labour market, Ninth edition, https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---dgreports/---stat/documents/publication/wcms_498929.pdf.

[1] ILO (2015), Labour Market Measures in Poland 2008–13: The Crisis and Beyond / Pawel Gajewski, International Labour Office, Research Department, Geneva, https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---dgreports/---inst/documents/publication/wcms_449932.pdf.

[18] JRC (2020), Telework in the EU before and after the COVID-19: where we were, where we head to, European Commission, Joint Research Centre (JRC), https://ec.europa.eu/jrc/sites/jrcsh/files/jrc120945_policy_brief_-_covid_and_telework_final.pdf.

[39] Matuszewska-Janica, A. (2018), “Women’s Economic Inactivity and Age. Analysis of the”, Folia Oeconomica, Vol. 5/338, pp. 57-80, http://dx.doi.org/10.18778/0208-6018.338.04.

[8] OECD (2020), Coronavirus (COVID-19) From pandemic to recovery: Local employment and economic development, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://read.oecd-ilibrary.org/view/?ref=130_130810-m60ml0s4wf&title=From-pandemic-to-recovery-Local-employment-and-economic-development.

[9] OECD (2020), Country initiatives : Poland, https://www.oecd.org/coronavirus/country-policy-tracker/.

[5] OECD (2020), COVID-19: Protecting people and societies, https://read.oecd-ilibrary.org/view/?ref=126_126985-nv145m3l96&title=COVID-19-Protecting-people-and-societies.

[10] OECD (2020), Evaluating the initial impact of COVID-19 containment measures on economic activity, https://read.oecd-ilibrary.org/view/?ref=126_126496-evgsi2gmqj&title=Evaluating_the_initial_impact_of_COVID-19_containment_measures_on_economic_activity.

[3] OECD (2020), Job Creation and Local Economic Development, Country Profiles: Poland, http://www.oecd.org/cfe/leed/Poland.pdf.

[12] OECD (2020), Job Creation andLocal Economic Development 2020 Rebuilding Better, https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/docserver/b02b2f39-en.pdf?expires=1614157510&id=id&accname=ocid84004878&checksum=8E80291E628CFF3C1A40EFAF8BC382FB.

[11] OECD (2020), Job retention schemes during the COVID-19 lockdown and beyond, https://www.oecd.org/coronavirus/policy-responses/job-retention-schemes-during-the-covid-19-lockdown-and-beyond-0853ba1d/.

[6] OECD (2020), OECD Employment Outlook 2020, https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/docserver/1686c758-en.pdf?expires=1614161288&id=id&accname=ocid84004878&checksum=E04A9AD0EA7CBCE29A3AA433B4A87AA0.

[25] OECD (2020), OECD Employment Outlook 2020: Worker Security and the COVID-19 Crisis, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/1686c758-en.

[42] OECD (2020), Women at the core of the fight against COVID-19crisis, https://read.oecd-ilibrary.org/view/?ref=127_127000-awfnqj80me&title=Women-at-the-core-of-the-fight-against-COVID-19-crisis.

[4] OECD (2020), |1THE TERRITORIAL IMPACT OF COVID-19: MANAGING THE CRISIS ACROSS LEVELS OF GOVERNMENT © OECD 2020Updated10November 2020COVID-19 has governments at all levels operating in a context of radical uncertainty. The regional and local impact of the COVID-19 cris, https://read.oecd-ilibrary.org/view/?ref=128_128287-5agkkojaaa&title=The-territorial-impact-of-covid-19-managing-the-crisis-across-levels-of-government.

[28] OECD (2019), OECD Employment Outlook 2019: The Future of Work, OECD Publishing, Paris., https://doi.org/10.1787/9ee00155-e.

[37] OECD (2019), OECD Skills Strategy Poland: Assessment and Recommendations, OECD Skills Studies, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/b377fbcc-en.

[31] OECD (2019), Pensions at a Glance - Country Profile Poland.

[30] OECD (2018), OECD Economic Surveys: Poland 2018, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/eco_surveys-pol-2018-en.

[2] OECD (2018), OECD Economic Surveys: Poland 2018, OECD Publishing, Paris., http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/eco_surveys-pol-2018-en.

[29] OECD (2017), Pensions at a Glance 2017.

[41] OECD (2016), Employment and Skills Strategies in Poland, https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/docserver/9789264256521-en.pdf?expires=1613488382&id=id&accname=ocid84004878&checksum=D1470ED93D67B0973EADD5C09145EF9E.

[34] Polakowski, M. and K. Hagemejer (2018), Reversing Pension Privatization: The Case of Polish Pension Reform and Re-Reforms, International Labour Organization, Social Protection Department, ESS –Working Paper No. 68, https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---ed_protect/---soc_sec/documents/publication/wcms_648632.pdf.

[21] SPRI (2020), El blog de la empresa vasca, https://www.spri.eus/es/financiacion-es/el-gobierno-vasco-destina-45-millones-para-las-pymes/.