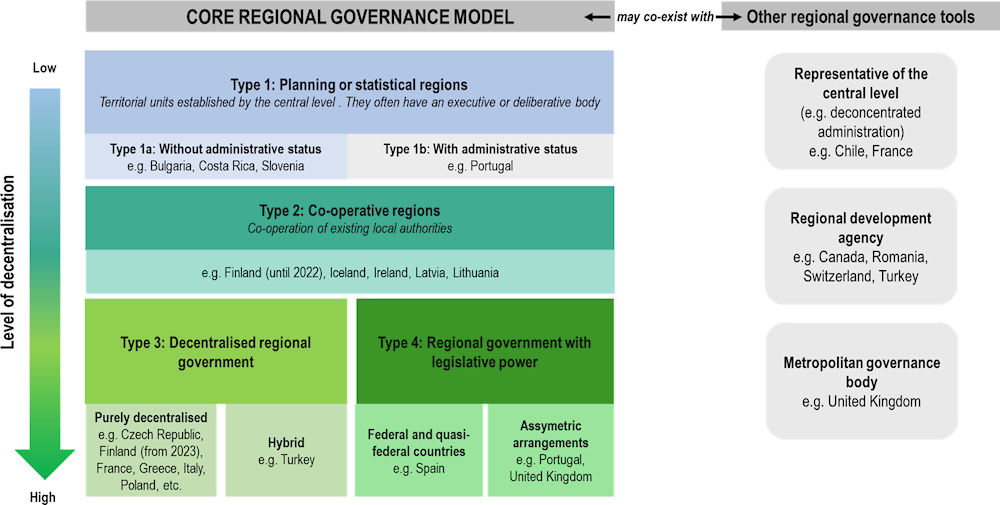

This chapter presents an innovative typology of regional governance models across OECD countries. The typology is based on the different regional governance models adopted by OECD countries, grouping them into four different categories: 1) planning or statistical regions; 2) co‑operative regions; 3) decentralised regional government; and 4) regions with legislative powers. This categorisation helps understand the different types of regional governance around the world, their main objectives, the main gaps the models attempt to solve and the main challenges they represent. The chapter then presents other bodies and governance tools that may exist at the regional level, such as representatives of the central administration at the regional level, regional development agencies and metropolitan governance bodies.

Regional Governance in OECD Countries

4. Towards a typology of regional governance

Abstract

Introduction

There is a broad spectrum of regional governance models across OECD countries, and often, different models co-exist within the same country. They vary from softer to harder forms, from mono-sectoral to multi-sectoral models. The forms that regional governance takes in a country not only depend on the objectives that they were meant to achieve but also on numerous country-specific factors, such as the extent of national integration, the conception of the state accepted by society and political elites, and, of course, the political situation.

Based on the different models adopted by OECD countries and beyond, this chapter suggests a typology of regional governance by grouping the different governance models into four categories.1 This categorisation may help understand the different types of regional governance around the world, their main objectives, the main gaps the models attempt to solve and the main challenges they represent. The regional governance models are categorised based on four dimensions:

Institutions: what are the institutions responsible for administering the perimeter of the region and its mandate? Regional institutions can be more or less costly to implement, both in terms of administrative costs and in terms of political acceptance by citizens and other levels of subnational government.

Governance: what is the governing body? The choice of the governing body for each regional governance model depends on the degree of autonomy and accountability endowed to each regional body.

Responsibilities:2 what are the main responsibilities of the different regional governance structures? Empowering regions (of any form) with adequate responsibilities can allow them to act effectively on their regional development and growth, and create stronger and more resilient territories. Allocating the right responsibilities to the regional level is, however, a delicate process, given that this process can be ascribed to several factors (e.g. the form of the state, the degree of decentralisation, the number of subnational government layers, the existence of a state territorial administration at regional level, etc.). Regional responsibilities may vary across regional governments within the same country as a result of asymmetric regionalisation.

Funding: how is the regional governance structure funded? The way in which regional governance structures are financed also determines the regional layer’s degree of autonomy.

For reasons of simplification and coherence, this categorisation applies to the prevailing, main or core governance model at the regional level. For each of the four categories, the core regional governance model may co-exist with other institutions or governance structures at the regional level, such as central representatives at the regional level responsible, for example, for security issues, or regional development bodies whose main purpose is to define and co-ordinate regional development issues.

Figure 4.1. Regional governance models in the OECD and European Union

Note: The examples of the four models outlined in the figure represent a snapshot taken at a moment in time, as regional arrangements are not static and are constantly evolving.

Planning or statistical regions

Main characteristics

Planning or statistical regions are territorial units established by the central government to plan at the regional scale and/or provide statistics at the regional level that may enlighten the planning process. They are created through the administrative reorganisation of central government authorities and are included in the central administration as deconcentrated entities. In general, these bodies have few powers and their main objective is to serve as a platform for discussion; regional policies remain closely controlled by the central level.

In some cases, these types of regions do not have a legal personality, and consequently, they do not have their own administration or budget. However, they may have representative bodies, such as an executive or a deliberative body, often called regional development councils (RDCs). These bodies are typically ad hoc or not permanent or but they usually meet several times a year. In some cases, they have a collegial structure that allows local authorities (i.e. representatives from local governments and social and economic partners) to be involved in regional issues. These representatives are not elected, but appointed by the central government. Some of these types of regions can have the legal status of regional deconcentrated state administration. Accordingly, they benefit from their own administration and their own budget, composed primarily of transfers from the central government. In the European Union (EU), and, under certain conditions, they also receive and manage EU funds. In general, they also have deliberative and executive bodies, but in contrast with those without a legal status, these bodies are often permanent. These regions are responsible for co-ordinating the deconcentrated arms of sectoral ministries at the regional level.

Planning or statistical regions are most often found in countries with only one level of subnational self-government (at the local level). This is the case of Bulgaria, Costa Rica and Lithuania, for example. In fact, the existence of planning, statistical or development regions often corresponds to situations where municipalities and local authorities are large and have an important space for action to deal with local issues (OECD, 2020[1]). Slovenia is another example, with certain specificities. While Slovenian development regions do not have administrative authority, co-ordination of regional development policies is ensured by a network of different regional organisations, including regional councils (also called councils of mayors), RDCs and regional development agencies (RDAs). Planning regions also exist in countries with a two‑tier system, such as Romania, where the 8 planning regions co-exist with 42 counties (among which the capital city of Bucharest) at the regional level.

The creation of statistical/planning regions can, in some countries, be a first step towards the creation of self-governed regional governance bodies. In France, for example, the deconcentration of the central state was the first step towards the current system. “Economic programme regions” were first created in 1954 and transformed in 1959 into “districts for regional action”. They were replaced in 1963 by 21 “administrative regions” and “regional economic development commissions”. At the same time, 21 “regional prefects” were established to represent the central government in the region. The underlying rationale remained centralisation, and economic development was led by the state. After a first failed referendum, aimed at creating elected regions in 1969, the Decentralisation Act of 2 March 1982 eventually gave the French regions the statute of fully fledged regional governments, providing them with additional responsibilities. This has been also the case in Chile, where between 1992 and 2021 regions where headed by an intendent, appointed by the president. This deconcentrated model was transformed into a mixed one in 2014; the intendent appointed by the president was the head of the region and worked together with a regional council elected democratically. Since 2021, there are self-governed regional governments in Chile with both the governor and the regional council elected by popular vote. In the EU, the creation of deconcentrated regions, with or without legal status, is often a response to the implementation requirements of EU accession. Bulgaria, for instance, is in the process of moving from planning regions to another level of decentralisation, although this process remains long and complex (Box 4.1).

Country examples

In Lithuania, until 2010, the county governor’s administrations acted as deconcentrated entities of central government. In 2010, the post of county governor and the county governor’s administration were abolished and their functions were redistributed among the municipalities and the central government. Counties remained as administrative units and ten RDCs, which were created in the counties in 2000, remained as independent collegial bodies composed of the mayors of all the municipalities belonging to that particular county, delegates from local councils, and an authorised person appointed from the government or governmental institution. RDCs also have been considered a tool for co-operation within and across the regions. The Department of Regional Development of the Ministry of Interior acted as the secretariat of the RDCs. Since 2017, representatives of social and economic partners, appointed by the government or an institution authorised by it, are also included in the RDCs, and they must represent at least one-third of the members of each council. However, until 2020, the RDCs’ administrative capacities and functions were limited, and were mainly concentrated on regional development planning; identifying lagging areas and development programmes for these areas as well as regional socio-economic development projects; and distributing some of the EU Structural Funds. Therefore, in 2020, the parliament adopted an amendment to the Law on Regional Development, making RDCs legal entities and extending their powers, relevant to the further creation of self-governing regions. RDCs became supra-municipal institutions with enhanced prerogatives to implement national regional policy in their territories (they were partially transferred some powers in regional development investment planning from ministries), and to promote inter-municipal co-operation (OECD, 2021[2])

Box 4.1. Regionalisation in Bulgaria: From planning regions to a place-based and integrated approach for regional development policy

Bulgaria has not always been without elected regions, in addition to its municipal level. In fact, in 1879 the first democratic Constitution, called Tarnovo, established 3 administrative levels: 23 districts, 84 counties and municipalities, and 2 of them – municipalities and districts – provided for self‑government. In 1947, the new Constitution established a system of Soviet-type councils, with “local bodies of state power”, reaffirmed in the 1971 Constitution. The administrative divisions included districts, counties and municipalities. Counties were abolished in 1959, and the 28 districts were merged into 9 larger regions in 1987.

The 1991 Constitution, and the subsequent Law on Local Government and Local Administration, established a two-tier model, with municipalities defined as the basic level of self-government, and the possibility of creating other levels of self-government by law. The regional level, as defined in the Constitution, was deconcentrated, not decentralised.

In 1999, the level of the 28 districts was re-established as deconcentrated units. They took the name of “regions” (oblast). The same year, the 1999 Act on Regional Development established regional development councils, led by regional governors and comprising municipal representatives, whose role is to advise on regional development issues.

In 2001, the Government Program indicated that it was necessary to conduct “a public discussion on … the establishment of a second level of self-government in accordance with the requirements for our European integration”. Reinforcing existing regional bodies has been under discussion since then without any real progress.

For 2021-27, Bulgarian regional policy is evolving towards a more integrated and place-based approach. The objective is to create vital, economically strong and sustainable regions as a response to adverse demographic trends and deepening interregional and intraregional disparities. To support this strategy, the OECD published a report in 2020, commissioned by the Ministry of Regional Development and Public Works, on Decentralisation and Regionalisation in Bulgaria: Towards Balanced Regional Development, which explores avenues for regionalisation in Bulgaria.

Source: OECD (2021[3]).

In Slovenia, although the Constitution provides for the creation of self-governing regions by law (Article 143), the numerous attempts at creating elected regions have failed successively until now. To manage regional development and EU funds, the Act on the Promotion of Harmonious Regional Development establishes a system of 12 “development regions” corresponding to NUTS 3 units, with no administrative authority. Several types of co-ordination bodies have been instituted to ensure co-ordination at the “regional” level (defined as NUTS 3 statistical regions) of regional development policy:

Twelve RDCs, which include representatives of municipalities, business associations, social partners and non-governmental organisations. They were created as a form of public-private partnership for regional development.

Twelve regional councils, which bring together all mayors in a given region. They approve the most important documents, i.e. the regional development programmes and agreements for regional development.

Twelve RDAs that are in charge of preparing, co-ordinating, monitoring and evaluating the regional development programmes, regional development agreements and regional projects. RDAs are public institutions since 2011 and serve as administrative, professional and technical agencies to support the functioning of the RDCs and regional councils (Slovenian Ministry of Economic Development and Technology, 2020[4]).

Since 2014, two development councils of the cohesion regions corresponding to Eastern and Western Slovenia (NUTS 2 level) have also been established. The current trend is to encourage inter-municipal co-operation as a mechanism for more effective and efficient local services and as an intermediate step towards political regionalisation (OECD, 2021[3]).

The main example of a deconcentrated region with administrative status is found in Portugal. In 2003, Portugal established five “commissions of co-ordination and regional development” (CCDR) at NUTS 2 level (Alentejo, Algarve, Centre, Lisbon and Tagus Valley, North). Although CCDRs are deconcentrated services of the central administration, they have administrative and financial autonomy from the central government.

The organisational structure of the CCDRs is quite complex and comprises a president assisted by two vice-presidents, an administrative board, a single controller, a supervisory commission, an inter-sectoral co-ordination council and a regional council. None of these bodies is directly elected, and the president of the CCDR is appointed by the Portuguese government from a list of three names drawn up by an independent recruitment and selection commission, following a competitive application for a period of three years. The CCDRs play an important role in the design and delivery of regional policy, carrying out important missions in the areas of environment, land and town planning and the development and implementation of the regional strategy. One of their biggest missions has been to manage regional operational programmes of European Structural and Investment Funds on mainland Portugal for the 2014-2020 programming period (OECD, 2020[1]). There is currently a debate in Portugal to reinforce the role of the CCDRs, by granting them more autonomy and more powers together with more accountability.

The creation of planning regions with administrative status was chosen as a suitable option in Portugal because municipalities have always been against setting up “decentralised regions” (which would have been territorial authorities), which they perceive as a threat to their autonomy (Nunes Silva and Buček, 2016[5]). Portuguese municipalities are relatively large in size and small in number. They fear that regional authorities will make them less autonomous, despite guarantees set out in the Constitution. In contrast, the establishment of planning regions was broadly accepted, and municipalities have become accustomed to working with the territorial departments of the state and have developed co-operation with them (OECD, 2020[1]).

Table 4.1. Main characteristics, benefits and challenges of statistical/planning regions

|

Domains |

Main characteristics |

Benefits |

Challenges |

Good practices |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Institutions |

– Deconcentrated power – appointed deconcentrated representatives from the central level. – Deconcentrated regions may or may not have legal status, and their own administration and budget. |

– Easy to establish in constrained legal and constitutional settings. – Well-adapted in small countries with low need of regional representativeness. – Broad acceptance of the newly created regions from other level of governments, which do not feel threatened in their autonomy (e.g. municipal). |

– Low citizens’ accountability. – No autonomy from the central government. |

– Provide planning regions with a legal personality, with their own budget and administration. |

|

Domains |

Main characteristics |

Benefits |

Challenges |

Good practices |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Governance |

– Deconcentrated regions often have an executive or deliberative body appointed by the central level. These bodies can be permanent or meet on an ad hoc basis. – They usually co‑exist with other regional institutions in charge of regional development policies (e.g. regional development agencies). |

– Municipalities and local authorities are strong and have important space for action. |

– When governing bodies are non-permanent, it might create low stability and continuity with high turnover. – Risks of overlap between the state deconcentrated administration and the planning/statistical regions. |

– Promote the creation of permanent executive or deliberative organs. – Ensure a balanced representation of local governments and central government representatives in the governing bodies. – Include a broad range of representatives from municipalities and civil society in governing bodies and other executive organs. |

|

Responsibilities |

– Functions limited to spatial planning, regional development. – For EU countries, management of EU Structural Funds. |

– Deconcentrated regions are valuable to central governments to promote regional economic development, mobilising local authorities and economic organisations. |

– Limited administrative capacities and functions. – Competences are often restrained to implementing the central government’s strategy for regional economic development, and the distribution of some EU Structural Funds. – Low capacity and autonomy of statistical/planning regions to develop place-based regional development strategies, and to implement policies adapted to local contexts. |

– Explore how deconcentrated regions’ responsibilities could be extended in spatial planning, regional development and the management of EU funds (including project selection, funding, implementation and monitoring). – Ensure that the responsibilities of deconcentrated entities are clear, especially when they co-exist with other institutions, such as regional development agencies. |

|

Funding |

– Delegated budget from the central government, or funded exclusively through grants and subsidies. – EU funds under certain conditions. |

– No own budget for planning regions without administrative status. – Mismatch between the limited delegated budget and regional needs. |

– Ensure adequate skilled staff and modern tools for planning regions to exercise their competences (e.g. efficient IT system, performance indicators). – Fund planning regions through stable, predictable transfers to enable them to plan over the medium to long term. |

Co-operative regions

Main characteristics

Co-operative regions or regional associations of municipalities are another form of regional governance that arises from the co-operation of existing local authorities. This is particularly the case of countries where local authorities have competences and functions that can be more effectively managed at a larger regional scale. Creating co-operative regions involves either extending the attributions and scope of action of local governments within this co-operative structure, or institutionalising their co‑operation within a wider framework (OECD, 2020[1]). Associations of municipalities at the regional level need to be distinguished from other common forms of inter-municipal co-operation, which refer to two or more municipalities working together, on a voluntary or compulsory base, for a more efficient provision of services, investment projects and/or planning purposes. In the same spirit, co-operative regions are different from associations of local governments that pursue political and representative purposes.

Regional associations of municipalities have legal status, and their creation requires the agreement from member municipalities. Across the OECD and the EU, regional associations of municipalities have different organisations, responsibilities and funding systems, depending on the country. In general, co-operative regions have regional councils made up of members elected by municipalities and a cabinet/office to run their activities. In this sense, the creation of co-operative regions tends to preserve the rights and authority of local authorities grouped together. There are, however, some examples where regional associations are endowed with strong institutions and sufficiently broad jurisdictions (e.g. Finland, Latvia) (OECD, 2020[1]).

The responsibilities of co-operative regions are usually limited. Their tasks often include regional development and spatial planning, EU funds management and some other tasks with clear region-wide benefita, such as environmental protection or roads. Regional associations can also carry out tasks that are delegated by their members (e.g. waste collection or management of school offices). This is especially the case for capital-intensive public services (e.g. utility systems such as water, waste and energy), which often require a certain minimum size for efficient service delivery. In this case, municipalities provide joint services and share the costs associated with the delivery of the service at the regional scale. As such, regional co-operation enables both greater economies of scale and tailoring services to local needs. Regional co-operation can also include joint efforts on the revenue side, although this is less common than expenditure co-operation.

Usually, co-operative regions have their own budget, generally funded by contributions from municipalities and through central government transfers. Still, reliance on contributions from municipalities can be insufficient in contexts where the financial capacity of local authorities is already limited. These challenges may become even more accentuated in light of the COVID-19 pandemic, which has had an important impact on subnational fiscal and financial health. This is why it is important to complement municipal contributions with transfers from the central level. The central government can allocate funding to regional associations based on several criteria: population, unemployment, municipal tax base, distance from the capital and service provision, etc. Funding can come from various ministries. In some cases, regional associations can access other sources of funding, such as EU funding and competitive funding for specific projects (OECD, 2020[6]).

Regional associations of municipalities can appear to be an attractive option compared with other models (e.g. the creation of decentralised regions) because they are relatively straightforward to establish and involve a “minimal” government restructuring. This is why co-operative regionalisation can be seen as an alternative to full regionalisation, but also as an intermediate stage towards full regionalisation, such as in Finland and Latvia. Wales, in the United Kingdom, is currently considering moving forward with regional co-operation through the creation of corporate joint committees (Box 4.2).

Box 4.2. Proposed corporate joint committees in Wales

In Wales, the Local Government and Election (Wales) Bill proposes establishing corporate joint committees (CJCs) as a formal inter-municipal co-operative mechanism with a regional footprint. The aim of this process is to support local authorities in economic development planning and policy implementation, to streamline existing collaboration arrangements, and to provide clarity and consistency in the sharing of regional responsibilities. CJCs should provide a mechanism for consistent regional working and collaboration with a clear framework for governing collaborative arrangements, setting clear expectations in those areas where regional-level collaboration is important. It also seeks to reinforce the ability of local authorities to work at a regional scale.

There are two possible paths for establishing CJCs. Via the first path, local authorities can voluntarily establish a CJC for delivering on any policy or service area as long as they have made a formal application to the relevant Welsh ministers, have respected the requirements governing a CJC’s establishment and Welsh ministers have agreed to make the regulations establishing a specific CJC. The second path allows Welsh ministers to establish a CJC to undertake functions in relation to any (or all) of the following four areas, all of which contribute to building and maintaining regional growth, inclusiveness and attractiveness: 1) economic development; 2) strategic planning for the development and use of land; 3) transport; and 4) education.

Regulations would enable CJCs to establish sub-committees; acquire, appropriate or dispose of property; and hold and manage funds, including borrowing or lending, providing or receiving financial assistance, and charging fees. General CJC financing would come from the constituent local authorities. CJCs would also be able to employ and remunerate support staff. Eventually, the ability of the local authorities to jointly carry out their tasks through the CJCs will depend on their fiscal, administrative and institutional capacities.

Source: OECD (2020[6]).

Country examples

In Finland, until recently, 20 regional councils covered the entire territory in the form of regional associations of municipalities. Legally, the regional councils were based on the Act of 1994 on Regional Development. A regional council was the region’s statutory joint municipal authority, and every local authority had to be a member of a regional council. The members of regional councils were indirectly elected by members of the municipal councils. Each council (excluding Åland) had an assembly and a cabinet. The Finnish regional councils were municipal co-operative organs with rather limited tasks. Their two main functions, as laid down by law, were regional development and spatial planning. The councils were also the regions’ key international actors and were largely responsible for the EU Structural Fund programmes and their implementation. This organisation has changed following a health and social service reform that created 21 elected regions that have replaced these councils (with the exception of the capital city Helsinki, which has maintained a special status). The first county elections were held on 23 January 2022, and the regions will be responsible, starting in 2023, for all health and social services as well as rescue services (OECD, 2020[1]; Sote-uudistus, 2021[7]).

In Ireland, there are three regional assemblies, created in January 2015 as part of the Local Government Reform Act 2014 (they replaced the previous eight regional authorities and two regional assemblies). A regional assembly is made up of members of the local authorities that compose the region. The assemblies aim to co-ordinate and support strategic planning and sustainable development and to promote effectiveness in local government and public services. In practice, their main function is to draw up “regional spatial and economic strategies”. Their other functions include oversight and statutory observations on city and county development plans and variations, managing regional operational programmes’ and monitoring committees’ funds, supporting the Committee of the Regions and Irish Regions Office in Brussels, promoting co‑ordination – between EU/national/regional and local governance, and developing knowledge through research and evidence-based activities for implementation and monitoring (OECD, 2020[6]; 2021[3]).

In Iceland, there are six regional associations of municipalities with a legal basis. Created in 2011, they ensure co-operation and co-ordination between local governments at the regional level on many topics. They also serve as a central government deconcentrated body. Since 2015, regional associations are in charge of preparing and implementing regional development plans for their regions, in addition to special tasks delegated from municipalities (e.g. waste collection and management of school offices). Iceland’s regional associations of municipalities develop their regional action plans in consultative fora (one per region), bringing together stakeholders from the private sector, cultural organisations, academia and others. The associations are supervised by a Steering Committee on Regional Issues, formed by all ministries, together with associations of local authorities. The Steering Committee on Regional Issues provides a direct link between the central government and the municipalities and guides them in the preparation of the regional plans. To enhance the country’s regional development policy, the government introduced contracts of regional plans to support decentralised funding to regional associations of municipalities. Accordingly, the eight regions’ regional plans of action are financed through eight regional plan-of-action contracts (OECD/UCLG, 2019[8]; Hilmarsdóttir, 2019[9]; Council of Europe, 2017[10]).

In Latvia, the members of regional development councils, which are part of the organisational structure of planning regions, are indirectly elected by municipal representatives, acting therefore as a co-operative structure or “inter-municipal co-operation” bodies. These regional development councils (decision-making bodies) work alongside two other bodies: the planning region administration (executive body) and the co-operation committee, which ensures the co-operation of the region with the different ministries. Regional development councils elect their chair and executive director (head of the administration of the planning region). A new round of territorial reforms began in 2019, based on the “Conceptual paper on new administrative territorial division”, putting the future of the planning regions up for discussion. In fact, the reform envisages merging the current 119 municipalities to create 39-42 local governments (354 municipalities and 7 state‑cities). This reform, if adopted, will have a significant impact on the planning regions. According to the “Regional Policy Guidelines 2021-27” published in November 2019, the Government Action Plan acknowledges the necessity to introduce a regional government level. In this perspective, the Ministry of Regional Development prepared the conceptual report that analyses the role of regions in reducing territorial disparities and favouring regional competitiveness and proposes possible regional governance models (Congress of Local and Regional Authorities, 2020[11]).

In Lithuania, the amendment to the Law on Regional Development in 2020 established RDCs as legal entities and extended their powers on the creation of self-governing regions. The RDCs are mainly platforms for inter-municipal co-operation at the regional level, and can be set up through an agreement between municipalities. The body of the RDC is the general meeting of participants, the governing bodies are the panel (composed of the mayors and members of the municipal councils) and the administrative director of the RDC representing the region. Their main competences include: planning and co-ordinating the implementation of the national regional policy in their respective region; encouraging the social and economic development of the region and the sustainable development of urbanised territories; decreasing social and economic disparities within and across regions; and encouraging co-operation among municipalities to increase the efficiency of public services provision.

Table 4.2. Main characteristics, benefits and challenges of co-operative regions

|

Domains |

Main characteristics |

Benefits |

Challenges |

Good practices |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Institutions |

– Co-operation of existing local authorities with legal status. – Their creation requires agreement from member municipalities. – They have different responsibilities and organisational and funding systems depending on the country. |

– Minimal government restructuring and low administrative costs. – Legal status arises through agreement among the member municipalities. |

– Adding a new hierarchical layer may increase administration and monitoring costs. |

– Potentially reconsider the existence of other regional bodies to avoid overlap. |

|

Governance |

– In general, they have regional councils made up of members elected by municipalities and a cabinet/office to run the activities. – The creation of co‑operative regions tends to preserve the rights and authority of local authorities grouped together. |

– Regional associations of municipalities reflect the voices of municipalities and local interests. – Strengthen cohesion among municipalities. – Enhance policy learning across municipalities and among stakeholders. |

– Democracy deficit, as regional associations are sometimes governed by representatives that are nominated by the member municipalities. – Limited accountability and transparency of local decision making. |

– Set up at least a partial system of direct election of regional representatives among the membership, to enhance accountability. |

|

Responsibilities |

– Usually limited. – Tasks often include regional development and spatial planning, EU funds management, and some other tasks with clear region-wide benefits, such as environmental protection or roads. |

– Increased service delivery efficiency. – Enhanced capacity to develop place-based, differentiated regional development strategies, to help bring forward regional interests. |

– Tasks of regional associations are often limited to regional development, spatial planning and EU funds management. – The member municipalities engaged in the co-operation have less power to affect the services than if the service was provided by their own organisation. |

– Clarify the roles, responsibilities and activities of the regional association compared with the role of other regional bodies. – Promote functions of mediation and co‑ordination between the various regional actors and stakeholders. – Successful policy making requires the ability of local authorities to co-operate among themselves, with other regions and with deconcentrated agencies. |

|

Funding |

– They usually have their own budget, generally funded by contributions from municipalities and through central government transfers. |

– Regional associations of municipalities have their own budget, generally funded by municipal member contributions. – They can also receive user fees from services rendered, central government transfers and EU funding. |

– Additional financial burden for municipalities in times of austerity. – Risk of low monitoring of the regional pool funding by each individual municipality. |

– Provide regional associations, when possible, with a certain degree of tax autonomy to match their funding needs and responsibilities, and provide incentives for regional development policies. – Build a relationship of trust between the central government and the associations by establishing clear funding rules (grants). |

Decentralised regional governments

Main characteristics

Decentralised regional governance is a model in unitary countries or quasi-federal countries3 where the region has elected bodies, at a higher level than local authorities. Decentralised regions, or elected regional governments, are the most widespread form of regional governance in the OECD and the EU. In this type of regional governance, regional governments are legal entities with their own budget, assets, administration and decision-making power. The governance structure of decentralised regions is based on a directly elected deliberative body (regional assembly or council) and an executive body, which can be elected by the regional council by and from among its members (the Czech Republic, Denmark, France, New Zealand, Norway, Poland, Sweden) or by direct universal suffrage (Croatia since 2009, Greece since 2011, Italy, Japan, Korea, Romania since 2008, the Slovak Republic) (OECD, 2021[3]). The direct election of regional councils is, indeed, a key characteristic of decentralised regions. Although this type of region modifies the territorial organisation, it comes under the constitutional order of the unitary state.

In some countries, decentralised regional governments’ boundaries correspond to the statistical Territorial Level 2 (i.e. TL2 in the OECD classification; NUTS 2 in the European Union). In other countries, the regional government level corresponds to the statistical Territorial Level 3. In other cases, they can coincide with either Territorial Level 2 or 3 – this is the case of New Zealand, for example, where regional councils belong either to TL2 or TL3, depending on their size (OECD, 2020[12]). In some cases decentralised regional governments have dual status as a municipality and a regional government, carrying out both municipal and regional responsibilities. This is particularly the case of capital cities, e.g. Oslo in Norway; Bucharest in Romania; Vienna in Austria; the German city-states of Berlin, Bremen and Hamburg; Zagreb in Croatia; and Prague in the Czech Republic.

Contrary to regions with legislative powers, decentralised regions have no normative power and are regulated by national law. Regions are overseen by a statute subject to a vote by the national parliament, although drawn up by the regional assembly, and not by a constitution like federal states. While multiple forms of institutional co-operation between the national level and regional governments exist, regional governments do not participate in the exercise of national legislative power through their own representation. In addition, decentralised regional governance includes measures to protect the autonomy of local authorities; in France, for example, territorial authorities are prohibited from having control over each other.

Decentralised regional governments are self-governing units with a certain degree of revenue‑generating power and autonomy over their spending decisions. Their sources of revenue may arise from a diverse pool of sources, including tax revenues, both own-source and shared (either with the central government and/or with other levels of government); grants from the central government; user charges and fees; property income; etc. In most cases, they can also access external resources through loans and bonds issuance.

Concerning their responsibilities, decentralised regional governments have a “general competence” (even if their responsibilities can be strictly defined) as opposed to “special-purpose subnational governments”, which have specific single or multiple functions (e.g. regional transport districts, water boards or sanitation districts, etc.). They also carry out significant responsibilities in investment in infrastructure of regional significance (e.g. transport). The responsibilities and functions of decentralised regional governments are broader than those of co-operative regions, but vary widely across countries. In a vast majority of cases, responsibilities are shared with another level of government (central or local) or another government institution at the same level; truly exclusive competences are rare. Some tasks can also be delegated by the central government to the regions. In several countries, decentralised regional governments have few powers, responsibilities and revenues (e.g. Croatia, Greece, Hungary, Poland, the Slovak Republic).

In the EU, the model of decentralised regions generally allows for transferring more tasks concerning the management of EU funds to regional governments. In several EU countries, decentralisation policies have resulted in transferring large responsibilities concerning EU fund management to the regions. In Poland, for example, since 2007, regions are fully responsible for a large share of European cohesion funds and thus regional bodies are the Managing Authorities (Mas) of the EU structural funds. In France, since the 2014 law on the modernisation of the territorial public action and affirmation of the metropolises, regions are in charge of managing EU funds for regional development (European Structural and Investment Funds, ESIF). This transfer of responsibility has led the regions to develop new functions such as steering, co-ordination, support, monitoring and auditing. However, the management of EU funds is not always a function of decentralised regions. In several countries, despite the existence of decentralised regions, there is still a centralised approach to regional development and EU funds management. This is particularly the case in countries having small decentralised regions (NUTS 3) (OECD, 2021[13]).

Country examples

Since the late 2000s, the Chilean government has pursued important decentralisation and regionalisation reforms. At the regional level, the deliberative power is in the hands of a regional council, whose members have been directly elected every four years since 2014. In 2018, the regional governance model that had been in place since 1992 was transformed into a “mixed” regional system (both deconcentrated and decentralised). Since 2021, there is a full self‑government system, with direct election of the regional executive (governors) by popular vote every four years. In parallel, in 2018 the process began of transferring responsibilities from the national government to the new self-governing regions on land-use planning, economic and social development, and culture. The Inter-ministerial Committee of Decentralisation supports and advises the President of the Republic on the competences to be transferred, which can result from presidential initiative or upon request from the regional government. Still, together with the new elected governors, a presidential delegate represents the central level in each of the 16 regions and is responsible for public security, emergencies and co-ordinating public services. The ministerial regional secretaries (SEREMIS) are also deconcentrated entities representing each ministry at the regional level.

The Czech Republic’s Constitutional Act of 1997 establishes the creation of “high-level territorial authorities” provided for in the Constitution, in the form of 13 regions and the capital, Prague, placed at the same level. A devolved state administration could be maintained in the regions, but the district offices would be abolished.

France is a good example of self-governing decentralised regions. The decentralised regions were created in application of the Act of 2 March 1982, and the first regional elections took place in 1986. In 2015, following the Law on the Delimitation of Regions, regional and departmental elections, and the merger of regions that followed, the number of regions decreased from 27 to 18 (including 5 outermost regions located in the French overseas territories, with a special status). French regions benefit from the principle of free administration by local authorities, which was initially consecrated by the Constitution for municipalities, departments and overseas territories. Regional elections are held in direct universal suffrage using proportional representation lists. The principle of free administration is not in itself a regulatory power, except in the case of express legislation; nor does it involve the exercise of any legislative power. In fact, due to their jurisdictions, the regions wield less normative power than the départements, and municipalities in particular. The regions cannot exercise or arrogate any authority over other local authorities on their territory.

Poland also has a form of decentralised regions. In 1999, Poland established 16 self‑governing regions (voivodeships) to replace the 49 regional bodies that had existed since 1975, but that did not function properly. The 16 regions are part of a three-tier subnational system, along with municipalities at the local level and counties at the intermediate level. The creation of voivodeships was permitted by the Constitution, in the framework of a growing decentralisation process taking place in Poland.

Japan has 47 prefectures at the regional level. The current system of prefectures was created by the Meiji government in 1871 with the abolition of the Han system. The current number of prefectures has remained unchanged since 1888. Prefectures have their own assembly, with directly elected members. They are headed by governors, also directly elected by the population. Among unitary countries, Japanese prefectures perceive a relatively high share of tax revenues, well above federated states in federal countries such as Australia, Belgium and Mexico. In parallel, they are also particularly strong public investors.

Table 4.3. Main characteristics, benefits and challenges of decentralised regional governments

|

|

Main characteristics |

Benefits |

Challenges |

Good practices |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Institutions |

– In unitary countries, the region has an elected authority at a higher level than local authorities. – They do not have any normative power; they are regulated by national law. |

– High level of regional autonomy. |

– This form of regional governance reform is more difficult to implement on a constitutional level. – Political opposition. |

Experimental regional governance, conducted in a few pilot areas, is a good practice to transition part or an entire territory towards decentralised regionalisation. |

|

Governance |

– Assembly or council and an executive body, which can be elected by the regional council by and from among its members or by direct universal suffrage. |

– Greater accountability and legitimacy in the co‑ordination of regional economic development and public service provision. |

– Multi-level governance challenges arise with the existence of a new elected level of government. – The asymmetrical arrangements can lead to claims for the generalisation of regional organisation, based on the same principles, usually with narrower autonomy. |

– Ensure strong co‑ordination across various levels of government and regular dialogue between the regional level and the central and local levels of government. – Strong transparency and accountability of regional bodies towards other levels, civil society and other stakeholders. |

|

Responsibilities |

– “General competence” as opposed to “special‑purpose subnational governments”. |

– Regions have greater jurisdictions and more room for maneuver to lead comprehensive regional development policies, benefit from economies of scale, and generate redistribution. |

– The sharing of responsibilities between regions and other levels may lead to overlaps and inconsistency of public policies. – – Risks of growing disparities across regional governments, based on their size, location and resources. |

– Clarify responsibilities and apply the principle of subsidiarity to devolve the most adequate competences to the regional level. – Strengthen capacities at the regional level to implement these policies. – Develop a national regional development strategy that takes into account regional and local needs, while ensuring equitable development between the various regions (pay particular attention to the most disadvantaged regions). |

|

Funding |

– Degree of revenue-generating power and autonomy over their spending decisions. – Sources of revenue may arise from a diverse pool of sources, including tax revenues, both own‑source and shared; grants from the central government; user charges and fees; property income, etc. – In most cases, they can also access external resources through loans and issuing bonds. |

– Regions have access to more diversified funding sources (tax revenue, central government and EU funding, subsidies, user charges and fees, income from assets). – Capacity to borrow and access external financing to carry out public investment. |

– Risk of mismatch between responsibilities devolved to regional governments and their limited financial capacities. – Too broad fiscal autonomy may lead to indebtedness of regional governments. |

– Necessity to establish a clear fiscal framework at the national level, including fiscal rules on debt, and enhance the monitoring role of the central government. – Approach fiscal decentralisation by balancing revenue and expenditure needs, and set up adequate funding mechanisms through grants and tax sharing. – Develop equalisation mechanisms at the regional level to ensure equity between the wealthiest and most disadvantaged areas. |

Regions with legislative powers

Main characteristics

Regions with legislative powers, in unitary, quasi-federal or federal countries, are characterised by several distinguishing aspects, including the attribution of legislative power to a regional assembly and therefore a high level of political autonomy. Regions with legislative powers have large responsibilities, whose content is defined and guaranteed by the Constitution, or at least by a constitutional-type text (except in the United Kingdom, where the parliament’s sovereignty prevails). These types of regions are found in the nine OECD federal and quasi-federal countries, as well as in unitary countries that have autonomous regions – Finland, Portugal and the United Kingdom. The executive and deliberative bodies of these regions are elected by direct universal suffrage. Unlike decentralised regional governments, these regions have their own regional parliaments that exercise primary or secondary legislative powers.

In federal and quasi-federal countries, the federated states (or regions) have, in most cases, their own constitution (Canada is an exception), parliament and government (OECD, 2020[12]). The self‑governing status of the states may not be altered by a unilateral decision of the federal government. Powers and responsibilities are assigned to the federal and state governments, either by the provision of a constitution or by judicial interpretation. In all OECD federal countries except Spain (a quasi-federal country), local governments are governed by the states, not by the federal government. In general, federated states have extensive responsibilities in key areas including education, social protection, economic development, transport, environment, housing, public order (regional police), civil protection, etc.

In unitary countries, asymmetric arrangements allow for having regions with legislative powers. In Finland, Portugal and the United Kingdom, there are also regions with legislative powers that arise from asymmetric forms of regional governance. In these unitary countries, the creation of regions with legislative powers resulted from the recognition of specific ethnic, historical, cultural and linguistic factors, in the name of which greater autonomy is granted to the regions in question. These specific features define their identity.

Whereas regional governments with legislative powers have a high degree of autonomy, it is common to find interregional co-operating bodies to facilitate dialogue among the various states and regions (e.g. Council for the Federation in Australia). These bodies also act as representatives for the states and provinces towards the central government, and are dedicated to facilitating broad policy co‑operation mandates between states and federal territories in a variety of sectors (dialogue and co‑operation bodies are further detailed in Chapter 5).

Country examples

Australia’s federal system is enshrined in the Commonwealth Constitution. The regional level is composed of six federated states and two self-governing territories. Each state has its own constitution, laws and a bicameral parliament with directly elected representatives (except for the state of Queensland which only has one chamber). State governments are headed by a premier, in general the party leader of the state parliament’s lower house, appointed as such by the governor, himself appointed by the Queen. The Northern Territory and Australian Capital Territory have a different governance structure, each headed by a chief minister and an appointed administrator, and each having a unicameral parliament. Local governments in Australia depend entirely on state governments, which each have their own local government acts and are governed by state legislation.

Mexico is divided into 32 states at the regional level. Mexico City, previously considered a Federal District, became the 32nd state of the federation in 2016. Each state has its own constitution and Congress, composed of deputies elected by universal suffrage. States can enact their own laws, as long as they do not contradict the national Constitution. They also have their own judiciary branch. Provisions regarding municipal autonomy are enshrined in the national Constitution and are detailed in each state’s constitution, to which municipalities belong. Horizontal co-ordination between the states occurs through the National Conference of Governors. There are also several councils dedicated to vertical co-ordination, involving representatives of the central government and the states (e.g. health council, education council, etc.).

Portugal, a unitary country, has two autonomous regions, Azores and Madeira – also recognised as the outermost regions at the European Union level – with a specific status and legislative power. Their legislative assembly is composed of members elected by direct universal suffrage, while the president of the regional government is appointed by the representative of the republic according to the results of the elections to the legislative assembly. They benefit from extensive legislative powers and define their own policy, except in the field of foreign policy and defence and internal security (European Committee of the Regions, 2020[14]).

In Finland, the self-governing region of Åland has a parliament elected every four years that appoints the regional Åland government. Parliament passes laws in areas relating to the internal affairs of the region and exercises its own budgetary power (Finnish Ministry of Foreign Affairs, 2020[15]).

In the United Kingdom, administrative devolution took place in 1999, when Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales got their own elected assembly and government. The powers and responsibilities of the three devolved bodies vary in nature and scope, as each devolution act was established independently. The devolved institutions in Scotland and Wales have subsequently evolved and taken on greater powers, whereas the process has been more precarious in Northern Ireland, with devolution suspended several times over the 20th century. The Constitution or national law confers the regions with a more or less extensive partial jurisdiction towards the local authorities in their territories, which includes at least some control of local authorities; in Scotland, devolution is almost total in this sense.

Table 4.4. Main characteristics, benefits and challenges of regions with legislative powers

|

Main characteristics |

Benefits |

Challenges |

Good practices |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Institutions |

– Attribution of legislative power to a regional assembly and therefore a high level of political autonomy. – In most cases, they have their own constitution (Canada is an exception), parliament and government. – Asymmetric arrangements in unitary countries. |

– High level of regional autonomy. |

– This form of regional governance reform is more difficult to implement on a constitutional level. – Political opposition. |

– Experimental regional governance, conducted in a few pilot areas, is a good practice to transition part or an entire territory towards eneralizatio eneralization. |

||||

|

Governance |

– Regional assembly with legislative power (primary or secondary). – Executive and deliberative bodies are elected by direct universal suffrage. |

– Greater accountability and legitimacy in the co‑ordination of regional economic development and public service provision. – Asymmetrical arrangements lead to better recognition of specific ethnic, cultural and linguistic factors. |

– Multi-level governance challenges arise with the existence of a new elected level of government. – The asymmetrical arrangements can lead to claims for the eneralization of regional organisation based on the same principles, usually with less autonomy. |

– Ensure strong co‑ordination across various levels of government, and regular dialogue between the regional level and the central and local levels of government. – Strong transparency and accountability of regional bodies towards other levels, civil society and other stakeholders. |

||||

|

Main characteristics |

Benefits |

Challenges |

Good practices |

|||||

|

Responsibilities |

– Wide-ranging responsibilities, whose content is defined and guaranteed by the Constitution, or at least by a constitutional-type text. |

– Regions have more jurisdiction and room for maneuver to lead comprehensive regional development policies, benefit from economies of scale, and generate redistribution. |

– The sharing of responsibilities between regions and other levels may lead to overlaps and inconsistency of public policies. – Risks of growing disparities across regional governments, based on their size, location and resources. |

– Clarify responsibilities and apply the principle of subsidiarity to devolve the most adequate competences to the regional level. – Strengthen capacities at the regional level to implement these policies. – Develop a national regional development strategy that takes into account regional and local needs, while ensuring equitable development between the various regions (pay particular attention to the most disadvantaged regions). |

||||

|

Funding |

– Degree of revenue-generating power and autonomy over their spending decisions. – Sources of revenue may arise from a diverse pool of sources, including tax revenues, both own-source and shared; grants from the central government; user charges and fees; property income, etc. – They can also access external resources through loans and issuing bonds. |

– Regions have access to more diversified funding sources (tax revenue, central government and EU funding; subsidies; user charges and fees; income from assets). – Capacity to borrow and access external financing to carry out public investment. |

– Risk of mismatch between responsibilities devolved to regional governments and their limited financial capacities. – Too broad fiscal autonomy may lead to indebtedness of regional governments. |

– Necessity to establish a clear fiscal framework at the national level, including fiscal rules on debt, and enhance the monitoring role of the central government. – Approach fiscal decentralisation by balancing revenue and expenditure needs, and set up adequate funding mechanisms through grants and tax sharing. – Develop equalisation mechanisms at the regional level to ensure equity between the wealthiest and most disadvantaged areas. |

||||

Other bodies and governance tools at the regional level

In parallel with the core regional governance model, several countries have established regional bodies or governance tools that may co-exist with the main administration exercising the executive and deliberative powers at the regional level. In some countries, for example, there are representatives of the central level at the regional level, even in decentralised regional governance models. Several countries have also put in place RDAs to promote and strengthen regional development policy. In general, these agencies work in parallel and in co-ordination with regional governments. Metropolitan governance bodies are also a governance tool that co-exists with the core regional governance model within countries; these bodies usually either replace regional governments in certain areas – having broader competences than regional governance structures – or work in parallel with regional governments as they cover a different territorial area.

Representatives of the central administration at the regional level

In several countries with decentralised regional governance structures, there are deconcentrated central authorities at the regional level. The deconcentrated authorities are subordinate to the central government or of organisations that, although endowed with a degree of legal autonomy, constitute instruments of its action placed under its control. Depending on the country, the balance of power among the decentralised region and the deconcentrated authority varies. In Sweden, deconcentrated central government regional units and regional governments with elected self-government and fiscal autonomy operate side by side. In France, the deconcentration tends to focus on sovereign functions of the state (security, financial and legal controls) whereas in the Polish case, regional deconcentration remains much more influential in the implementation of territorial policies and strategies. In Chile, since 2021, there is a presidential delegate whose main responsibilities are related to security and legal controls.

Regional development agencies

RDAs can support countries in the design and implementation of regional development policies and investments “on the ground”. The core idea behind the “agency model” is to have a certain degree of separateness from the central or regional government, i.e. separate certain functions from a given public ministry or department by transferring them to a different legal entity at the regional level. RDAs have a key role in regional governance, tasked with the co-ordination of regional development processes. They offer an alternative or a complement to the core regional governance arrangement, contribute to the design and implementation of national development programmes, and help co-ordinate public investment for regional development. Regional development agencies can take a number of forms and serve diverse functions (OECD, 2016[16]; 2020[6]):

as a network to organise national interventions for regional development within a decentralised context (e.g. Canada)

to build capacity at the regional level in a centralised country context, and to provide administrative and technical support (e.g. Slovenia and the Republic of Türkiye)

to help national and subnational actors capitalise on complementary actions across policy sectors in a given region (e.g. Finland)

to support entrepreneurs and small and medium-sized enterprises, promote innovation and cluster development, and attract investment, acting also as a one-stop shop for firms to obtain information on programmes and support in accessing funding for projects (e.g. Chile, Ireland, New Zealand and Scotland)

to ensure that policy makers have the evidence necessary to take informed decisions on a wide variety of topics that influence regional development and investment, and to work with regional partners to advance development objectives (e.g. France).

The legal status of RDAs also varies across OECD countries, be they federal or unitary, centralised or decentralised, with or without elected bodies. For instance, RDAs in Switzerland are organised either as public sector corporations (e.g. “regions” in the Canton of Grisons or “regional conferences” in the Canton of Bern), as stock corporations (e.g. Region Oberwallis AG), or as associations. Most RDAs are organised as associations (e.g. Romania). They may have an “exclusive” membership, consisting entirely of public entities (usually municipalities), or an “inclusive” membership, comprising both public and private entities (e.g. interest groups, local businesses, local inhabitants and guests). RDAs with an exclusive membership often involve private actors by appointing them as advisers to the board or inviting them to participate in working groups. However, regardless of whether they have formal membership or not, private actors largely remain providers of ideas and input (Willi and Pütz, 2018[17]).

In countries with statistical/planning regions, it is common to find RDAs that play the role of administrative, professional and technical agencies that support the work of the regional development councils and other regional bodies. In the EU, the creation of RDAs – or structures of a similar purpose – has been driven by the EU accession process, notably for countries in Eastern Europe without elected regional governments. Lithuania is an example where the implementation of spatial planning and regional development policy was carried out by an appointed governor at the level of higher administrative units (i.e. county). Three RDAs were created, respectively for Kaunas, Klaipeda and Utena, to support the local authorities in attracting investments, project development and management. Still, RDAs’ authorities are not elected and, therefore, they are not a substitute to the role that a regional government can play for regional planning and economic development. RDAs and similar entities can, however, sustain the development and strengthening of regional governments, through capacity building, in particular in sectors such as public-private partnerships, designing and prioritising investment projects, and monitoring and evaluation of regional investment.

Most RDAs are regionally managed, i.e. RDAs created by and reporting to a regional government. These RDAs are owned at least partially by regional governments, and sometimes local authorities, associations of municipalities or other public entities (the Czech Republic’s RDAs, Korea’s economic region development committees). On the other hand, a few OECD countries have nationally led RDA networks to support regional development (e.g. Türkiye). These agencies, in general, incorporate both central and local governments’ representatives in the governing bodies. National RDAs mays exist in countries where regional governments do not exist, or when they do not have sufficient human and financial capacities

National and regional RDAs may also co-exist in the same country. Canada, a federal and highly decentralised country, has a well-developed network of six national RDAs to help organise national interventions for regional development. The responsibility for the six RDAs falls under the sole jurisdiction of the Ministry of Economic Development (a shift with the past approach, when various regional ministers were assigned responsibility for each of the six agencies across the country). In parallel, Canadian provinces have their own RDAs that co-exist with the national network. In Australia, the national network Regional Development Australia was created in 2012. It operates through a network of 52 RDA committees, made up of local elected officials, business and community groups. The national network aims to identify local investment priorities, attract catalytic investment and co-ordinate the Regional City Deals process.

In general, RDAs have a different governance structure (in terms of hierarchical relations, responsibilities of leaders, use of governing/management boards), as well as greater management autonomy (via mechanisms such as performance contracts, multi-year budgeting, etc.) than deconcentrated central government authorities, making them more efficient and effective (OECD, 2015[18]). One advantage of RDAs is their ability to foster greater understanding and stronger working relationships between national and subnational actors, and across policy sectors. Due to their separate legal status, RDAs are better able to engage with the private sector in numerous ways, notably regarding financial instruments. They can also help generate international ties and expand markets for businesses of all sizes.

The creation of RDAs often responds to the ambition of creating greater accountability in regional development. RDAs may be required to set up performance evaluation indicators, and to have clear accountability processes. Even when RDAs are accountable directly to a region, they are still part of a complex governance landscape involving multiple levels of government, and sometimes the private sector. A survey in Europe noted that 40% of surveyed RDAs had funding sponsorship from other levels of government beyond the region, and therefore may be also accountable to a public-private board (Danson, Halkier and Damborg, 2017[19]). As non-democratically elected bodies, it is crucial that RDAs are transparent and fully accountable, regarding both financial transactions and policy implementation, to remain legitimate.

Country examples

The Canadian RDAs are part of the federal government’s Innovation and Skills Plan and are dedicated to advancing and diversifying their regional economies and ensuring that the communities therein thrive. These agencies have also served to address economic challenges in their regions by providing tailored programmes, services, knowledge and expertise. This includes building on regional and local economic assets and strengths; supporting business growth, productivity and innovation; helping small and medium-sized enterprises effectively compete globally; providing adjustment assistance in response to economic downturns and crises; and supporting communities. Each of the six RDAs brings a regional policy perspective to advance the national agenda by providing regional economic intelligence to support national decision making; contributing to federal-regional co-ordination and co-operative relationships with other levels of government, community and research institutions, and other stakeholders; and supporting national priorities. RDAs work collaboratively with each other and with the provincial and local development agencies in their territories to ensure national co-ordination and a maximum of efficiency. They represent Canada on territorial development matters and in developing or renewing national programmes or services delivered at a regional level.

Romania has a network of eight RDAs, which operate at the regional level alongside eight development regions, created for statistical purposes for the supervision of regional development and of the management of EU funds. The RDAs were created on a voluntary basis and are responsible for co-ordinating regional development for each region. The Regional Development in Romania Act (No. 315/2004) establishes the institutional framework for regional development policy in Romania (OECD/UCLG, 2019[20]).

Türkiye established a national network of 26 RDAs in 2006, based on Law No. 5449. Türkiye has no regions as such, and therefore the RDAs form the NUTS 2 level, that has been used as the regional planning unit for preparing regional plans and strategies. RDAs have a participatory approach to encourage public-private dialogue. Currently, all 26 NUTS 2 regions have their own regional development plans prepared by development agencies and local stakeholders for the 2014-23 period. These plans are important in tailoring policy and implementation to local needs and circumstances. They also highlight regional situations that may need national-level intervention (OECD/UCLG, 2019[20]).

Metropolitan governance bodies

OECD countries are increasingly adopting metropolitan governance arrangements to address administrative and territorial fragmentation and to foster economic and inclusive growth. OECD empirical research has shown that for a given population size, a metropolitan area with twice the number of municipalities is associated with around 6% lower productivity. This effect is mitigated by almost half when there is a metropolitan-level governance body established (Ahrend, Gamper and Schumann, 2014[21]). An OECD study provides statistical evidence showing that, on average, more administratively fragmented metropolitan areas have a higher spatial segregation of households by income (OECD, 2016[22]).

There are different forms of co-operation arrangements in metropolitan areas, ranging from soft (dialogue platforms/informal/soft co-ordination) to the more “stringent” in institutional terms (supra‑municipal body, metropolitan cities). While there is no “one-size fits all” model but rather a range of models that vary based on territorial and institutional contexts, more integrated and strategic forms of inter‑municipal co-operation structures are needed for these areas to cope with metropolitan issues. Some elements are essential to ensure effective metropolitan governance, including political representation, geographic boundaries that match the boundaries of the economic region (functional area), clear assignment of expenditure responsibilities and revenue sources, and decision-making power, including some fiscal autonomy (OECD, 2021[2]).

Box 4.3. Experimentation, asymmetry and deal-making approach: Some international examples

France, an example of an asymmetric approach and metropolitan contracts: To manage its functional urban areas, France has developed three forms of inter-municipal co-operation: metropolises (métropoles) for functional urban areas with more than 400 000 inhabitants (21 as of 1 January 2019), “urban communities” for those with 250 000-400 000 inhabitants (13 communautés urbaines) and “agglomeration communities” for those with 50 000-250 000 inhabitants (223 communautés d’agglomération). Within the metropolis category, introduced by the 2014 Law for the Modernisation of Territorial Public Action and the Affirmation of Metropolitan Areas, there is an additional differentiation between the three largest metropolitan areas (Aix-Marseille-Provence, Lyon and Paris, which have already had special status since the 1982 PLM Law) and the others (common law statute). Finally, Aix-Marseille-Provence, Lyon and Paris also have different ad hoc governance structures – i.e. different organisation, responsibilities and resources. In 2016, the government launched a new form of contract, the state-metropolis pacts, which aim to empower the new metropoles and support urban innovation at the metropolitan scale through financial partnering in some key investments. Their main objective is to consolidate the future position of metropoles in the institutional landscape.

The Devolution Deals in the United Kingdom: Since 2010, the United Kingdom has developed a comprehensive policy on devolution and local economic growth. Government interventions to support economic growth are being pursued at different scales (cities, functional urban areas, regions, pan-regions) to ensure that all parts of the country benefit from sustainable economic growth. Devolution Deals build on the previous City Deals to cover city regions, as well as local authorities in both urban and rural areas, to improve policy co-ordination between cities and their regions. Devolution Deals mostly involve the devolution of powers and governance changes (an elected city-region mayor). They are agreements (contracts of usually ten years or more) signed between the government and “combined authorities” at the city-region level and are bottom-up proposals focused on leveraging investment for locally determined priorities. In England, for example, deals focus on driving economic growth, providing for the decentralisation of powers over skills and transport policy, the creation of a “single pot” to support local investment, and the ability to raise additional revenue through financial instruments such as a mayoral precept.

Experimenting with metropolitan governance in Chile: The programme Pilot Project for the Establishment of Planning and Co-ordination Capacities for Metropolitan Areas was launched in 2015 and carried out in four Chilean regions, which were selected as pilots to demonstrate and address the different morphological, functional and population differences present in Chile’s emerging metropolitan areas (La Serena-Coquimbo in the Coquimbo Region, Greater Santiago in the Metropolitan Region, Greater Concepción in the BioBío Region and Puerto Mont-Puerto Varas in the Los Lagos Region). Among the competencies were carried out by the “the metropolitan regional government” awere preparing a metropolitan urban transport master plan; elaborating an inter-municipal investment plan of infrastructure; and operating the collection, transport and treatment of solid waste and traffic regulation of urban roads. The metropolitan regional government was advised by a committee of mayors, representing the municipalities making up the metropolitan area.