This chapter focuses on how the Slovenia government rationalises its existing stock of regulations, including how it undertakes reforms to improve regulation in specific areas or sectors to, for example, reduce administrative burdens and other compliance costs associated with regulation or evaluate the overall effectiveness of a regulation.

Regulatory Policy in Slovenia

Chapter 6. The management and rationalisation of existing regulations in Slovenia

Abstract

Slovenia has focused its efforts to manage the stock of regulation mainly on reducing administrative burdens, leading to significant reductions of burdens for business. It was among the early adopters of the Standard Cost Model to measure and reduce administrative burdens. The government has also undertaken major e-government reforms to simplify administrative procedures (OECD, 2015a). Furthermore, Slovenia’s system of physical one-stop shops for business received the United Nations’ Public Service Award

Slovenia would benefit from broadening the evaluation of the stock of regulations beyond administrative burdens to systematically assess the stock of regulation against achievement of objectives of regulation, unintended consequences and to ensure regulations are still necessary and the most efficient option for the policy problem at hand. In particular in-depth reviews of key sectors and policy areas could inform major policy reforms to trigger economic growth and enhance Slovenia’s competitiveness.

Regulatory burden reduction

Slovenia started in 2005 its first efforts to reduce administrative burdens and has scaled up its effort significantly over the last decade. In 2005 the Economy Friendly Administration Council was established to reduce administrative barriers in the creation and operation of companies. A first programme for eliminating administrative barriers was adopted in 2006 and a permanent inter-ministerial working group for the better preparation of regulations and elimination of administrative barriers was formed in 2007.

In 2009, the Action Programme of the Government to reduce administrative burdens by 25% by 2012 in line with the target of the European Council was adopted and a list of acts and related executive acts to be assessed in terms of their burdens was approved. Special attention was paid in 2010 to the area of labour law including amendments to the Employment and Insurance against Unemployment Act, the Labour Market Regulation Act and the Occupational Health and Safety Act. Established in 2011, the Minus 25 portal provides the public with information on the implementation of the programme for reducing administrative burdens.

By 2012, 3 529 regulations were reviewed with a combined estimated EUR 1.5 billion of administrative burden. The measurement identified areas with high potential for reducing burdens including environment and spatial planning, labour legislation, cohesion, finance including taxes and excise duties and business or financial reports. While about 200 measures were implemented, the adoption of many acts that were planned to be amended failed and changes in acts in the area of labour law were rejected in referendums. The 2012 renewed Action Programme for eliminating administrative barriers included unrealised measures from the previous programme and additional measures stemming from the Contract for Slovenia 2012-15.

In 2013, the Government combined a number of measures taken by different parts of the government to improve the regulatory environment for business and increase competitiveness. The so-called “Single document” (later renamed into a Single collection or Single set of measures) includes a description of each measure, proposals for solutions and deadlines for the realisation of measures. The government appointed a permanent inter-ministerial working group headed by the Minister for Public Administration and the Minister for Economic Development and Technology to oversee the implementation of measures and regular report to the government on progress made. Furthermore, a website application was established in 2014 to provide users with an overview of all measures and information on progress in their implementation. By the end of September 2016, out of 299 measures, 164 were implemented, 2013 partly implemented and 32 not implemented. Key measures taken in 2016 and envisaged in 2017 include reforms in spatial planning and building construction, renovation of regulated professions, tax restructuring and better regulation policies such as the introduction of an SME test and burden reduction for business including simplification in the field of tourism.

Overall, the government estimates the combined effect of key measures taken in the period 2009 to 2015 to reduce burdens including also measures from the “Single document” at EUR 365 million of reduction for business entities and citizens. Prepared by two external consultants for the Ministry of Public Administration, the evaluation report finds that the highest savings were achieved in the Ministry of Labour, Family and Social Affairs & Equal Opportunities followed by the Ministry of Finance and the Ministry of Justice (Ministry of Public Administration of the Republic of Slovenia, 2016).

Target areas for burden reduction were identified based on both stakeholders’ suggestions submitted through the portals Stop the bureaucracy (see Box 6.1) and predlagam.vladi.si and according to the results of the baseline measurement carried out by the government as part of the Programme for eliminating administrative barriers and reducing burdens. In terms of the methodology for measuring administrative burdens, the Ministry of Public Administration prepared and published guidance for measuring regulatory costs based on the Standard Cost Model (SCM) which also includes a methodology for measuring direct financial costs and compliance costs.

Box 6.1. Stop the Bureaucracy portal

The Stop the Bureaucracy portal was set up by the Government of the Republic of Slovenia to improve the business environment and enhance the impact of entrepreneurship on the process of drafting and adoption of regulations. The portal targets a national and international audience of entrepreneurs and citizens.

Via the web portal, users may submit their proposals for eliminating burdens and simplifying procedures. After being published on the portal, proposals or comments will be assigned to the competent ministries, which may then express their opinions on the proposals and comments and give their feedback to the user issuing the proposal. Individual proposals and comments will be published and made available on the portal for users to review, sorted by topic and ministry responsible. The Slovenian Ministry of Public Administration, who manages, co-ordinates and harmonises the implementation of the Stop the Bureaucracy project, created a video explaining the process of submitting proposals to the portal in detail.

Since the launch of the portal in 2013, 181 measures for better regulation and a better business environment were realised.

Source: The responses of the Slovenian government to the OECD questionnaire; Ministry of Public Administration of the Republic of Slovenia (2015), “Stop the Bureaucracy! Reducing administrative and regulatory burdens for MSP and citizens”, www.stopbirokraciji.si/en/stop-the-bureaucracy/.

A recent academic study (Kalas and Baclija Brajnik, 2017) analyses the effect of reforms in the area of tax policy and accounting obligations that aimed to reduce burdens by creating a “flat rate taxation system”. It finds that these measures were less effective because Slovenian businesses were not all aware of the option to use the “flat rate taxation system” or did not choose this option. They conclude that stakeholders need to be included in all stages of the policy cycle to ensure impact of policy measures to reduce burdens and better understanding of the reasoning for regulations.

Ex post reviews of regulations

The OECD Recommendation of the Council on Regulatory Policy and Governance (OECD, 2012a) emphasises the need to conduct systematic programme reviews of the stock of significant regulation against clearly defined policy goals, including consideration of costs and benefits, to ensure that regulations remain up to date, cost justified, cost effective and consistent, and deliver the intended policy objectives. There are a number of reasons why ex post evaluation is necessary and useful. First, many regulations will not have been done well and others have passed their “use by date”. Second, the stock of regulation is much greater than the flow and gains are therefore potentially large. Third, ex post reviews can provide learnings for future regulatory actions (Banks, 2017).

While the impact of new regulations is usually evaluated through a regulatory impact analysis, there are a number of different approaches for ex post evaluation (see Box 6.2). Practical ways to embed ex post evaluation in a country’s policy system include sunset clauses to require governments to review a regulation a certain amount of time after it has been promulgated, scheduled reviews that look at whole policy frameworks for different areas and specialised standing bodies, like the Australian Productivity Commission that have a mandate to review regulations and to make recommendations for improvement.

Box 6.2. Approaches to regulatory review

The Productivity Commission issued a research report that lists a number of good design features for each review approach which help ensure that they work effectively, drawn from Australian and international good practices. The Commission considered the following main approaches:

Stock management approaches (have an ongoing role that can be regarded as “good housekeeping”):

Regulator-based strategies refer to the way regulators interpret and administer the regulations for which they are responsible – for instance through monitoring performance indicators and complaints, with periodic reviews and consultation to test validity and develop strategies to address any problems. Ideally, the use of such mechanisms is part of a formal continuous improvement programme conducted by the regulator.

Stock-flow linkage rules work on the interface between ex ante and ex post evaluation. They constrain the flow of new regulation through rules and procedures linking it to the existing stock. Although not widely adopted, examples of this sort are the “regulatory budget” and the “one-in one-out” approaches.

Red tape reduction targets require regulators to reduce existing compliance costs by a certain percentage or value within a specified period of time. Typically, they are applied to administrative burdens reduction programmes.

Programmed review mechanisms (examine the performance of specific regulations at a specified time, or when a well-defined situation arises):

Sunsetting provides for an automatic annulment of a statutory act after a certain period (typically five to ten years), unless keeping the act in the books is explicitly justified. The logic can apply to specific regulations or to all regulations that are not specifically exempted. For sunsetting to be effective, exemptions and deferrals need to be contained and any regulations being re-made appropriately assessed first. This requires preparation and planning. For this reason, sunsetting is often made equivalent to introducing review clauses.

“Process failure” post implementation reviews (PIR) (in Australia) rest on the principle that ex post evaluation should be performed on any regulation that would have required an ex ante impact assessment. The PIR was introduced with the intention of providing a “fail-safe” mechanism to ensure that regulations made in haste or without sufficient assessment — and therefore having greater potential for adverse effects or unintended consequences — can be re-assessed before they have been in place too long.

Through ex post review requirements in new regulation, regulators outline how the regulation in question will be subsequently evaluated. Typically, this exercise should be made at the stage of the preparation of the RIA. Such review requirements may not provide a full review of the regulation, but are particularly effective where there are significant uncertainties about certain potential impacts. They are also used where elements of the regulation are transitional in nature, and can provide reassurance where regulatory changes have been controversial.

Ad hoc and special purpose reviews (take place as a need arises):

“Stocktakes” of burdens on business are prompted or rely on business’ suggestions and complaints about regulation that imposes excessive compliance costs or other problems. This process can be highly effective in identifying improvements to regulations and identifying areas that warrant further examination, but their very complaint-based nature might limit the scope of the review.

“Principles-based” review strategies apply a guiding principle being used to screen all regulation for reform – for instance removal of all statutory provisions impeding competition (unless duly justified), or the quest for policy integration. Principles-based approaches involve initial identification of candidates for reform, followed up by more detailed assessments where necessary. Approaches of this kind are accordingly more demanding and resource-intensive than general stocktakes. But if the filtering principle is robust and reviews are well conducted, they can be highly effective.

Benchmarking can potentially provide useful information on comparative performance, leading practices and models for reform across jurisdictions and levels of government. Because it can be resource-intensive, it is crucial that topics for benchmarking are carefully selected. Benchmarking studies do not usually make recommendations for reform, but in providing information on leading practices they can assist in identifying reform options.

“In-depth” reviews are most effective when applied to evaluating major areas of regulation with wide-ranging effects. They seek to assess the appropriateness, effectiveness and efficiency of regulation – and to do so within a wider policy context, in which other forms of intervention may also be in the mix. In the Australian context, extensive consultation has been a crucial element of this approach, including through public submissions and, importantly, the release of a draft report for public scrutiny. When done well, in-depth reviews have not only identified beneficial regulatory changes, but have also built community support, facilitating their implementation by government.

Source: Australian Productivity Commission (2011), “Identifying and Evaluating Regulation Reform”, Research Report, Canberra; OECD (2015), OECD Regulatory Policy Outlook 2015, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264238770-en.

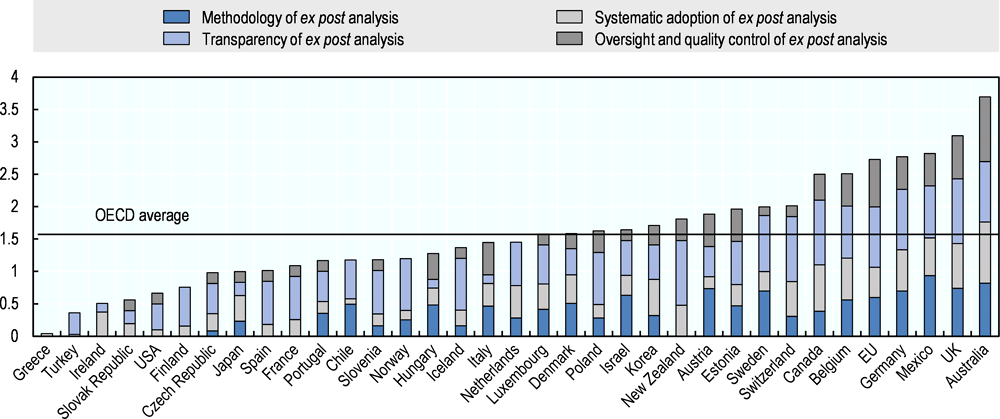

While programmes to reduce administrative burdens are well established in Slovenia, ex post evaluation of regulations to assess whether regulations achieve their objectives are not systematically conducted in Slovenia. Slovenia scores below the OECD average on the Indicators of Regulatory Policy and Governance for ex post evaluation.

Figure 6.1. Ex post evaluation for primary laws

Notes: The results apply exclusively to processes for developing primary laws initiated by the executive. The vertical axis represents the total aggregate score across the four separate categories of the composite indicators. The maximum score for each category is one, and the maximum aggregate score for the composite indicator is four. This figure excludes the United States where all primary laws are initiated by Congress. In the majority of countries, most primary laws are initiated by the executive, except for Mexico and Korea, where a higher share of primary laws are initiated by parliament/congress (respectively 90.6% and 84%). See the Annex A for a description of the methodology of the iREG indicators.

Source: OECD (2015), OECD Regulatory Policy Outlook 2015. http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264238770-en.

The Government of Slovenia only requires review of laws that are passed under an emergency procedure,1 and it does not require systematic reviews of laws. However, few laws enacted under this procedure have been reviewed. At present, 76% of laws and regulations are completed under this emergency procedure, but only recently have many of them been reviewed. In March 2017, the Government adopted a report on IAs on laws adopted by urgent procedure from 4 June 2010 to 31 December 2014. The Secretariat General of the Government obtained the data by asking all departments/ministries in January 2017 to conduct ex post evaluation on the regulations under their jurisdiction that had been adopted by urgent procedure during that period.

Despite the good intent of the report, it contains impact assessments only on individual areas and whether or not the law has achieved its purpose. The ex post evaluations are often quite cursory. The report demonstrates a strong need to develop appropriate methodologies and training to build capacities in line ministries to do proper ex post analysis.

Requirements for systematic ex post evaluation are useful, yet not sufficient. Without sufficient skills and capacity the quality of ex post evaluations and their political impact might be low. Governments need to assist evaluators and desk officers to design, manage and execute the evaluations (OECD, 2015). Box 6.3 provides some examples of building capacity and providing support to evaluators in OECD countries.

Box 6.3. Building capacity and providing support to evaluators: Canada, European Commission and Switzerland

In Canada, The TBS Regulatory Affairs Sector initiated a number of measures to assist in building evaluation skills across federal departments and agencies, including:

the development of a core curriculum by the Canada School of Public Service, which features also a course on “Regulatory performance measurement and evaluation”;

the creation of the Centre of Regulatory Expertise (CORE), which provides technical support concerning cost-benefit analysis, risk assessment, performance measurement and evaluation of regulations; and

the establishment of the Centre of Excellence for Evaluation (CEE), which serves as a help-desk body in the planning and implementation of evaluations. This includes supporting the competent departments and agencies in the implementation and utilisation of evaluations, and helping to promote the further development of evaluation practices, not least through guidelines and manuals.

In the European Commission, in the framework of the Smart Regulation strategy, central support and co-ordination is ensured by the Secretariat-General (European Commission, 2015a). The latter issues guidance; provides in-house training; and organises dedicated workshops and seminars. The Secretariat-General oversees the EC’s evaluation activities and results and promotes, monitors and reports on good evaluation practice. Evaluation units are present in almost all Directorates-General. Several “evaluation networks” dedicated to specific policy areas are also at work (for instance in relation to research policy or regional policy).

Also in Switzerland, despite the fact that there is no central control body for the implementation and support of evaluation in the federal administration, experiences and expertise is shared thanks to an informal “evaluation network”. The network exists since 1995 and is directed at all persons interested in evaluation questions, and comprises around 120 members from various institutions.1

Source: European Commission (2015a), “Evaluation”, Better Regulation, http://ec.europa.eu/smart-regulation/evaluation/index_en.htm (last update 11/08/2015); Australian Productivity Commission (2011); Prognos (2013), “Expert report on the implementation of ex post evaluations: Good practice and experience in other countries”, report commissioned by the National Regulatory Control Council, Berlin, www.normenkontrollrat.bund.de/webs/nkr/content/en/publikationen/2014_02_24_evaluation_report.pdf?__blob=publicationfile&v=2.

The institutional setting for evaluation is key to successful implementation. As for RIA, minimum standards and oversight of ex post evaluations conducted in ministries is necessary to ensure evaluations are actually undertaken, are of sufficient quality and unbiased. Some countries such as Australia and New Zealand have also established a standing capacity to conduct in-depth reviews in high priority areas to inform large-scale reforms, often at the request of governments. Examples of recent reviews and public inquiries include reviews to boost the service sector, reform local government regulation and to develop capacity of land housing in New Zealand and reviews of telecommunication service obligations, Australia’s overall productivity performance, regulation of agriculture and fisheries regulations in Australia. Reviews usually include public inquiries and the government has to respond publicly to findings. For example, the Australian’s Productivity Commission conducted a review of barriers to setting up, transferring and closing a business. In the inquiry report, the Productivity Commission informed the Government of Australia about the nature and extent of barriers for businesses to enter and exit a market and their consequences for economic growth. It then developed recommendations for strategies to reduce these barriers where appropriate (Australian Productivity Commission, 2015). The Government of Australia supported many of these recommendations and as a result committed to eliminating the barriers identified by the Productivity Commission and to creating a new framework for entrepreneurial activity in order to encourage innovation (Australian Government the Treasury, 2017).

ICTs and administrative simplification

E-government plays an important role in Slovenia in simplifying administrative procedures. The e-government state portal e-Uprava, first established in 2001 and renewed in 2015, is the central state portal for electronic services. It links to information based on life events of citizens and businesses. The renewal paid special attention to preparing texts that are precise but simple enough for users to understand, to translate information into languages of Slovenia’s national minorities (Italian and Hungarian) and to include a sub-portal with adapted content to meet the needs of the foreigners living in or moving to Slovenia. The portal receives on average 5 000 unique visitors per day; in the first year of production approximately 40 000 electronic applications have been submitted. As part of the renewal, every authenticated user can use now their digital certificate to access private documents and view their personal data from public records such as personal information, information about their vehicle and real estate property. The module Moja eUprava (My eGovernment) enables users to access their submissions to government and provides information on progress made in their resolution.

The e-government portal is essential for facilitating exchanges between the state and its citizens. It lowers operating costs of public authorities, because they can provide their services in one place. Furthermore, it reduces transaction costs for citizens who no longer need to look for services on various websites of public authorities but can instead read all of the information on the portal, as well as electronically submit an application and monitor its progress.

ICT has also been used to simplify access of businesses and citizens to information on the regulatory framework. In July 2010 the Slovenian government adopted an action plan for establishing a point of single contact to implement the EU Directive on services in the internal market and the Directive on the recognition of professional qualifications. At the same time, the database helped realise the national political goals to simply the business environment for national and foreign business entities, to establish a uniform and transparent database of regulated activities and professions, and to present legal contents in a transparent and structured manner.2 In a first stage, a database has been established to provide information to service providers and users in any member state on procedures for obtaining permits to practise regulated activities in Slovenia. The government is currently implementing the second stage of the project which will allow service providers from any EU member state to perform all formalities and procedures defined by the EU Services Directive on the web portal.

Box 6.4. E-Vem Portal for Domestic Business Entities in Slovenia

The One Stop Shop Business portal or the e-VEM portalis a government portal which provides several public administration services at once to companies and sole traders with the goal of making the interaction between businesses and administration easy and simple.

The e-VEM portal enables users to conduct all administrative procedures related to starting and managing a company online. This includes the submission of forms for social insurance registration, declaration of modifications to information on family members, notification of needs for workers, etc. With the help of digital certificates, users can carry out many of these procedures independently. For more complicated procedures requiring assistance by the administration, 139 one-stop shop contact points as well as a “VEM point” have been established.

The portal won the 2009 United Nations Public Service Award in competition with North American and European countries in the “improving the delivery of services” category.

Source: The response of the Slovenian government to the OECD questionnaire.

A key part of the project is the analysis of over 400 regulations determining the conditions and procedures for performing activities and profession in Slovenia. In co-operation with the competent line ministries, an inter-ministerial group for the renewal of legislation in the field of regulated activities and professions was founded that is comprised of a strategic and an expert section of members. It was tasked with studying relevant legislation and proposing reforms to eliminate administrative barriers, such as unnecessary conditions and procedures for performing activities and professions. It was also tasked to deregulate if the conditions and procedures do not comply with EU legislation or the practice of Member States and standardisation and to simplify procedures to facilitate implementation of the online support for performing formalities and procedures.

In 2012 a programme for deregulating and simplifying access conditions in a number of professions was put in place. The government plans to extend this programme to include both some of those professional services that were covered in the 2012 measure (including construction and tourism), and new occupations, such as funeral parlours, chimney sweeping, real estate agencies, driving schools and legal professions (Government, 2016). So far, deregulation has been limited or postponed, for example in the construction sector (OECD, 2017).

Assessment and recommendations

Despite requirements for ex post evaluation for regulations passed through emergency procedure and for reviewing the state-of-play while drafting regulations, ex post evaluation is relatively rarely done in Slovenia. Current evaluations have mostly focused on reducing administrative burden. These evaluations have been successful in improving business conditions in Slovenia, but greater embedding of ex post evaluation could further enhance Slovenia’s competitiveness and ensure regulations meet economic, social and environmental objectives.

The Slovenian government should monitor if ministries perform ex post evaluation on regulations passed by emergency procedures and publish this information online to provide incentives for ministries to undertake evaluations. A central oversight body could be tasked with regular monitoring. Putting pressure on ministries needs to be accompanied by measures to build capacities in ministries to help desk officers undertake evaluation and quality control of the evaluations to ensure they are not just a “tick the box exercise”. Slovenia may consider establishing a procedure to regularly discuss evaluations of regulations passed by emergency procedures to improve regulations where necessary and be aware that some fast track regulations might in hindsight not be working.

Slovenia should focus ex post evaluation efforts on priority areas. The central government could identify together with stakeholders major policy areas and sectors and pilot fitness checks or in-depth reviews together with the corresponding ministries. Beyond looking at regulations in isolation, regular review of regulations and policy measures in key policy areas and sectors that are identified to be of particular economic or social importance can have very high returns. While Slovenia has conducted some target, sector wide reviews, such as the review of spatial planning and construction permits in 2015, there is not yet a systematic approach to in-depth reviews. Slovenia may consider establishing a standing capacity that regularly reviews priority areas to inform reforms and require governments to respond to the findings of major reviews.

Slovenia would benefit from introducing a requirement to assess laws and regulations sometime after their implementation to ensure they meet their objectives, are still relevant and the best policy option to address the problem at hand. In a first step Slovenia may introduce automatic review requirements for major regulations, indicating already in the RIA when and how they will be assessed.. Staff in ministries needs to be trained to conduct evaluations or ensure the quality of evaluations contracted out to academics and to use evaluations of existing regulations before amending regulations. All evaluations should be published online in a central place that is easily accessible to the general public. Resources for evaluation could be focused on high-impact regulations to avoid evaluation fatigue.

A central body could co-ordinate ex post evaluation efforts to identify priority areas for review together with stakeholders within and outside government. In a first step, the body could support ministries in evaluating key policy areas. The central body could also help to build capacity and provide assistance to ministries for evaluation. Similarly to RIA, a central body with sufficient power and independence in its technical assessment could provide quality control of evaluations conducted in ministries. In order to avoid duplication, reduce transaction costs, and improve the link between ex-ante and ex post evaluation; Slovenia may consider assigning responsibility for quality control of ex ante and ex post evaluations as well as consultation to a single body.

Bibliography

Australian Government the Treasury (2017), “The Australian Government’s response to the Productivity Commission inquiry report into business set-up transfer and closure”, Canberra. http://treasury.gov.au/PublicationsAndMedia/Publications/2017/Gov-response-to-Productivity-Commission-Inquiry.

Australian Productivity Commission (2015), “Business Set-up, Transfer and Closure”, Productivity Commission Inquiry Report No. 75, Canberra. www.pc.gov.au/inquiries/completed/business/report/business.pdf.

Australian Productivity Commission (2011), “Identifying and Evaluating Regulation Reforms”, Research Report, Canberra. www.pc.gov.au/inquiries/completed/regulation-reforms/report/regulation-reforms.pdf.

Banks, Gary (2017), “Effective ex post evaluation: purpose and challenges”, Presentation to OECD’s 9th Conference on Measuring Regulatory Performance, 20-21 June, Lisbon, Portugal. https://www.slideshare.net/OECD-GOV/effective-ex-post-evaluation-purpose-and-challenges.

Court of Audit of the Republic of Slovenia (2007), “Revizija preverjanja učinkov predlaganih predpisov”, www.rs-rs.si/rsrs/rsrs.nsf/i/k7ace46de95f89323c1257186001d5cc5.

Court of Audit of the Republic of Slovenia (2012), “Revizija preverjanja učinkov predlaganih predpisov”, www.rs-rs.si/rsrs/rsrs.nsf/i/k7aaecfafa8dfd535c1257a62001c1180.

Kalas, Luka and Bacilija Brajnik, Irena (2017), “Administrative burden reduction policies in Slovenia revisited”, Central European Journal for Public Policy, Vol. 11/1.

Ministry of Public Administration of the Republic of Slovenia (2016), “Reduction of Regulatory Burdens from 2009 to 2015”, www.stopbirokraciji.si/fileadmin/user_upload/mju/English/Publication/Brosura_MJU_FINAL_eng3small.pdf.

Ministry of Public Administration of the Republic of Slovenia (2015), “Stop the Bureaucracy! Reducing administrative and regulatory burdens for MSP and citizens”, www.stopbirokraciji.si/en/stop-the-bureaucracy/.

National Audit Office of the UK (2008), “The Administrative Burdens Reduction Programme, 2008”. https://www.nao.org.uk/report/the-administrative-burdens-reduction-programme-2008/.

OECD (2017), OECD Economic Surveys: Slovenia 2017, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/eco_surveys-svn-2017-en.

OECD (2015a), OECD Regulatory Policy Outlook 2015, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264238770-en.

OECD (2015b), Regulatory Policy in Perspective: A Reader's Companion to the OECD Regulatory Policy Outlook 2015, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264241800-en.

OECD (2015c), Policy Findings and Workshop Proceedings, “Embedding Regulatory Policy in Law and Practice”, 7th OECD Conference on Measuring Regulatory Performance, 18-19 June, Reykjavik, Iceland, www.oecd.org/gov/regulatory-policy/Reykjavik-workshop-proceedings.pdf.

OECD (2014), OECD Framework for Regulatory Policy Evaluation, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264214453-en.

OECD (2012a), Recommendation of the Council on Regulatory Policy and Governance, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264209022-en.

OECD (2012b), Measuring Regulatory Performance: A Practitioner's Guide to Perception Surveys, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264167179-en

Notes

← 1. Article 8b of the Rules of Procedure of the Government of the Republic of Slovenia.

← 2. The databases by activity and profession are now available online in Slovenian and English through the Slovenia Business Point, http://eugo.gov.si/en/.