This chapter examines the processes in place in the federal higher education system in Brazil to monitor the quality of established undergraduate programmes and take action in the event of poor performance. As currently designed, the cycle of ongoing quality monitoring involves the use of large-scale student testing, administered through the National Examination of Student Performance (ENADE), the results of which feed, with other indicators, into a composite indicator of programme performance – the Preliminary Course Score (CPC). When programmes score poorly on the CPC measure, they are subjected to an on-site peer review visit and may ultimately face sanctions imposed by the Ministry of Education. The chapter provides a critical assessment of these processes and provides recommendations for their improvement.

Rethinking Quality Assurance for Higher Education in Brazil

5. Assuring and promoting quality for existing undergraduate programmes

Abstract

5.1. Focus of this chapter

Undergraduate programmes are subject to an ongoing cycle of evaluation and regulation

Once undergraduate programmes have been recognised under the procedures discussed in the previous chapter, they are subject to an ongoing cycle of evaluation, coordinated by INEP on behalf of the Ministry of Education. As currently designed, this cycle involves the collection and collation, by INEP, of programme-level data, including the results of the programme’s students in a national assessment of learning outcomes, to create a composite indicator of programme performance every three years. As a general rule, in cases where programmes score low ratings in relation to this composite indicator, a new on-site programme review is undertaken by external evaluators. The results of a programme in relation to the composite indicator and, where used, the on-site review determine whether or not SERES renews its official recognition, thus guaranteeing that the diplomas awarded by the programme retain national validity.

Large-scale, external student testing forms part of this cycle

One of the most distinctive features of this ongoing quality assurance process for undergraduate programmes in Brazil is the use of large-scale, discipline-specific student testing. The assessment of the performance of students from every undergraduate programme is an explicit requirement of the 2004 legislation that established SINAES, the National System of Higher Education Evaluation (Presidência da República, 2004, p. art.2[1]). Each year, students graduating from programmes registered in a particular set of disciplinary fields are required to take a mandatory competence assessment – the National Examination of Student Performance (Exame Nacional de Desempenho de Estudantes, ENADE). Disciplines are assigned to three broad groups, with disciplines in group I evaluated one year, group II the year after and group III the year after that, meaning each discipline is subject to ENADE every three years1. The ENADE tests contain a general competence assessment common to exams in all fields in a single year and a discipline-specific component. In addition, all students participating in ENADE are required to complete a student feedback questionnaire providing biographical information and a personal assessment of their programme.

The results of ENADE tests feed into a composite indicator of programme quality

The results achieved in ENADE by students in a given programme are converted into an average, which is then assigned a score on a scale of one to five, based on its position in the distribution of the average scores for all programmes in the federal higher education system in the same disciplinary field. The resulting score out of five is referred to as the “ENADE score” or Conceito ENADE. The Conceito ENADE is subsequently used, alongside a standardised indicator based on a comparison of ENADE scores for each student with their previous performance in the Exame Nacional do Ensino Médio (ENEM) school-leaving exam; data on staff involved in the programme; and scores from the student feedback questionnaire, to generate an overall score for each programme on a scale of one to five. This programme score – misleadingly named the Preliminary Course Score or Conceito Preliminar de Curso (CPC)2 - is used to provide an indication – albeit partial - of the overall performance of the programme in question (MEC, 2017[2]).

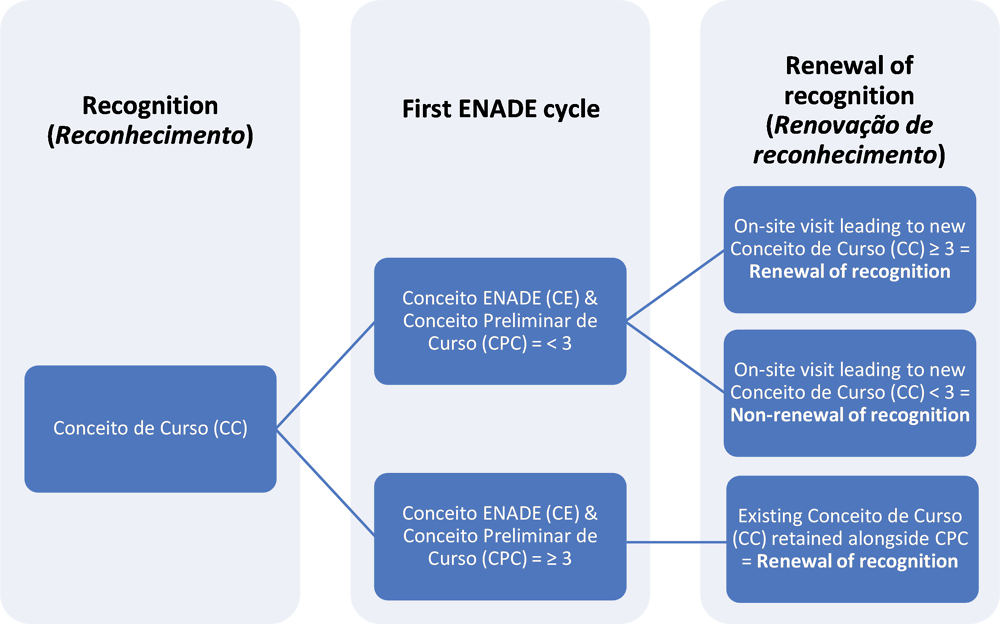

If the CPC is three or above, the programme usually has its official recognition renewed by SERES (a regulatory process called Renovação de reconhecimento), without further direct evaluation until the subsequent round of ENADE, three years later (MEC, 2017[2]). If a programme obtains a CPC score of one or two, INEP organises another on-site evaluation visit, using the same criteria and evaluation template as used for the initial process of programme recognition, discussed in the previous chapter (INEP, 2017[3]). If the site visit leads to a positive assessment, with a Conceito de Curso (CC) of three or above, the programme in question has its recognition renewed. If it obtains a score lower than three, it will be subject to supervisory measures by SERES and ultimately risks losing formal recognition – and thus national validity for the diplomas it awards. SERES may request that programmes that achieve a CPC of three or above are also subject to site visits if there are other reasons to do this.

The steps in this cycle of evaluation and regulation are illustrated in Figure 5.1 below.

Figure 5.1. The cycle of evaluation and regulation for undergraduate programmes

Note: The ENADE cycle for each subject area is repeated every three years.

Source: OECD based on information from INEP and SERES (MEC, 2017[2])

5.2. Strengths and weaknesses of the current system

The sections which follow provide an assessment of the strengths and weaknesses of the current model of ongoing quality assurance for undergraduate programmes in Brazil, involving the systematic use of ENADE and the Preliminary Course Score (CPC) and selective use of site visits.

Measuring student performance: ENADE

Relevance: rationale and objectives of the current system

Brazil is one of the few countries worldwide that implements a national system of testing for undergraduate students and is probably the only higher education system that draws on external assessment of learning outcomes to such a large extent in its regulatory, supervisory and quality assurance model. The most notable other examples of system-wide external student testing in higher education in the world are also in Latin America.

Colombia has compulsory competency testing for graduating undergraduate students in the form of the Saber Pro exams, although the compulsory modules applied to all students in that system focus on measuring generic competencies3. In the Colombian system, additional discipline-specific modules are only taken by students when their higher education institutions opt in to this component (ICFES, 2018[4]). In Mexico, CENEVAL, an independent foundation, implements a system of discipline-specific tests for students graduating from academic bachelor programmes, the Exámenes Generales para el Egreso de Licenciatura (EGEL). However, in the Mexican context, whether or not students take this exam depends on the specific policies of the HEI they attend, not on specific requirement from public authorities. Unlike Brazil, Mexico does not have a comprehensive and compulsory system of quality assurance in higher education and EGEL is therefore used by HEIs to monitor their own performance and demonstrate the effectiveness of their programmes to the outside world, rather than as an input to universal evaluation and regulatory processes (OECD, 2018 (forthcoming)[5]).

The formal objective of ENADE is set out in the 2004 legislation establishing SINAES:

ENADE shall assess students' performance in relation to the curriculum guidelines for their respective undergraduate course, their ability to adjust to the requirements arising from the evolution of knowledge and their competence in understanding themes outside the specific scope of their profession, linked to Brazilian and worldwide realities and other areas of knowledge. (Presidência da República, 2004, p. art.5[1])

The most recent Ministry of Education ordinance describing INEP’s evaluation activities in higher education further specifies that ENADE should measure the “skills and competencies” that undergraduate students have “acquired in their training”. It should do this based on the content in the relevant National Curriculum Guidelines (Diretrizes Curriculares Nacionais); the National Catalogue of Advanced Technology Programmes (Catálogo Nacional de Cursos Superiores de Tecnologia); “associated norms”; and “current legislation regulating professional practice” (MEC, 2017, p. art.41[6]). The National Curriculum Guidelines (DCN) and the National Catalogue of Advanced Technology Programmes specify expected learning outcomes for programmes in different fields at a general level. The formal expectation is thus that ENADE should assess the extent to which students have acquired, through their undergraduate programme, the learning outcomes specified in these documents. In addition, as shown in the citation above, the 2004 legislation calls for ENADE to measure the ability of students to adjust to the “evolution of knowledge” and the ability of students to understand wider themes outside their immediate field of study.

Defining and measuring learning outcomes in higher education in a systematic way has been an increasing focus in higher education practice and policy in recent decades (CEDEFOP, 2016[7]). This trend reflects a widespread recognition that gaining a better understanding of the extent to which students really acquire new knowledge and skills through higher education would provide useful feedback for teachers and educational institutions and useful information for governments and society at large on the educational performance of higher education (OECD, 2013[8]). On a conceptual level, it is desirable to have reliable information on learning outcomes – and not simply inputs and processes involved in the learning process – in order to judge how effective and efficient the education provided is in practice. However, while the explicit definition of expected learning outcomes has become the norm across many higher education systems, final assessment of these learning outcomes is nearly always left to individual teachers and institutions (or to employers or professional organisations). In contrast to practice at school level, where many OECD and partner countries use external high school leaving examinations, attempts at the comparable measurement of student learning outcomes in higher education, between institutions and disciplines, have been rare (OECD, 2013[8]).

In Europe, for example, the systematic establishment of expected learning outcomes for higher education programmes has been a key feature of the Bologna Process. The capacity of programmes to deliver these learning outcomes is a strong focus of many European quality assurance models. Nevertheless, no European quality assurance system has so far attempted to incorporate direct assessment of learning outcomes in its processes, although some – such as that in the Netherlands (NVAO, 2016[9]) and Sweden (UKÄ, 2018[10]) – have included qualitative assessment of selected student outputs in programme-level reviews.

The OECD initiated the Assessment of Higher Education Learning Outcomes (AHELO) (OECD, 2013[8]) project and the European Commission has supported a project to develop frameworks to assess learning outcomes in different higher education disciplines (Comparing Achievements of Learning Outcomes in Higher Education in Europe - CALOHEE) (CALOHEE, 2018[11]). However, neither of these initiatives has yet been fully implemented in large-scale testing.

Despite the widely accepted potential value of assessing learning outcomes in theory, in practice, external assessments at higher education level face substantial challenges:

A first challenge is defining what to measure. Whereas in school education, all students are expected to follow a common core of subjects, at least until the end of compulsory schooling, students in higher education study subjects with a narrower, but deeper focus. Within their chosen discipline, higher education students also tend to specialise in certain sub-domains, especially in the later years of their course. Accurately measuring the skills and competences acquired by students during their programme requires testing instruments that are adequately tailored to the content of the programmes in question. If tests are aligned too closely to specific programme content, they can only be applied to comparatively small numbers of students, who have been exposed to that specific content. This makes creating a system-wide testing system complex and costly and can restrict comparability of results to comparatively small cohorts. If the tests are made more general, to allow them to be applied to a larger number of students, there is a risk that the test content is no longer sufficiently aligned to the programme content to allow causal inferences to be made about the effects of the programme on student learning.

The challenge for test developers is, therefore, where to set the boundaries of discipline-specific knowledge, in terms of breadth and depth, to maintain a clear link to programme content, while creating a test that is widely applicable. In some cases, such as the Colombian Saber Pro exam, test developers have avoided this problem by focusing compulsory test components exclusively on generic competences and using the same test for students from all disciplines. The first problem with this approach is that generic competences are often an implicit, rather than explicit, intended learning outcome of higher education programmes. Although higher education programmes may help students to improve their reading skills and basic problem-solving, this might be a by-product of the main teaching and learning activities, rather than an explicit focus. Generic competence tests therefore set out to test competences that higher education programmes – rightly or wrongly – might not have set out to develop in their students, while ignoring discipline-specific content and skills that are the prime focus of the course.

A second key challenge is how to identify and formulate test items that can measure, in a reasonably brief test, the kinds of knowledge and discipline-specific competencies that students might be expected to acquire through a programme lasting three, four or more years. Alongside the breadth of theoretical knowledge that could be covered in a written test, lies the challenge of creating assessment models for the practical and professional skills that are central to many higher education programmes such as nursing, medicine, engineering or architecture. Although it is conceivably possible to cover a wide range of topics and tasks in a standardised test lasting several hours, a balance needs to be struck between coverage of items and creating optimal conditions for a student to perform to the best of their ability. Long tests are tiring, while short tests can create excessive stress that impacts negatively on student performance.

A final issue relates to the risk that standardised testing, even when adequately differentiated between disciplines and types of programme, can unduly influence the programme content and pedagogical approaches used by institutions and teaching staff. When broad curriculum guidelines are translated into a specific test, this necessarily entails making specific judgements about what students should learn. When the test in question matters, this encourages teachers to “teach to the test”, with a clear risk that legitimate learning objectives and subjects not covered by the test are excluded and that programme coordinators feel constrained in make changes to their curricula. Standardised testing might thus constrain curriculum breadth, innovation and responsiveness to changing circumstances.

In light of these considerations, the OECD review team considers that the objectives of ENADE, as currently formulated, are unrealistic. The relevant legislation, noted above, requires ENADE to measure students’ performance in relation to the content of relevant national curriculum guidelines, their ability to analyse new information and their wider understanding of themes outside the scope of their programme. This creates problems, as follows:

The requirement to measure understanding of unspecified “themes outside the scope of the programme” is inherently problematic because it is so general and the knowledge and skills assessed, by definition, are not part of the programme’s core intended learning outcomes. It is thus unclear how those running programmes could be expected to equip students with such a wider range of unspecified knowledge and skills or why they should be held accountable for students’ not having these competencies at the end of their studies.

As ENADE is a written examination with a restricted duration, it is impossible to measure the full range of learning outcomes that any adequately formulated curriculum guidelines should contain. At best, written examinations (computer or paper-based) can measure a scientifically robust selection of discipline-specific knowledge and skills and, potentially, generic competences such as logical reasoning or problem-solving (if such competencies are intended learning outcomes). An exam like ENADE can only ever assess a small proportion of what students will have been expected to learn over the duration of their programme. It would be beneficial if this were acknowledged in the stated objectives of the exam.

By implying that ENADE sets out to measure students’ learning outcomes in relation to the National Curriculum Guidelines for undergraduate programmes, there is a risk that the content of ENADE (in a given year or previous years) comes to be seen to define what is important in the National Curriculum Guidelines. In practice, the National Curriculum Guidelines in Brazil (MEC, 2018[12]) specify very general content for programmes, leaving considerable scope for HEIs and teachers to innovate and adapt content to current needs. If ENADE has an excessively narrow approach, it risks undermining this freedom. In interviews, representatives of HEIs in Brazil, indicated that the content of ENADE did indeed influence the content of their programmes.

If ENADE is to be maintained, Brazil’s legislators and quality assurance authorities need to provide a more credible account of what it can realistically achieve and how risks for innovation and responsiveness can be mitigated.

Effectiveness: quality indicators used and generated

ENADE aims to measure student performance through an assessment composed of ten questions focused on general competencies (formação geral), of which two call for short discursive answers and the rest multiple choice answers, and 30 discipline-specific questions, of which three are discursive and 27 are multiple choice. The general competency questions are common to all ENADE exams in a single year. Exams are taken with paper and pen in test centres hosted by students’ higher education institutions and students have up to four hours to complete the whole exercise. Participation in the examination is compulsory for all students graduating in courses in the fields being assessed in a given year, with attendance being a pre-requisite for receiving the diploma for their degree4. The tests are administered on the three-year cycle described above, with fields following the order set out in Table 5.1.

Table 5.1. ENADE cycle

|

Year |

Fields examined |

|---|---|

|

1 |

a) Bachelor's degrees in the areas of Health, Agrarian Sciences and related areas; |

|

b) Bachelor's degree in Engineering; |

|

|

c) Bachelor's degrees in the area of Architecture and Urbanism; |

|

|

d) Advanced Technology Programmes (Tecnologias) in the areas of Environment and Health, Food Production, Natural Resources, Military and Security; |

|

|

2 |

a) Bachelor's degrees in the areas of Maths, Natural Sciences, Computing and related areas; |

|

b) Evaluation areas leading to a double qualification with Bachelor's degree and Licenciatura; |

|

|

c Evaluation areas leading to a Licenciatura; |

|

|

d) Advanced Technology Programmes (Tecnologias) in the areas of Control and Industrial Processes, Information and Communication, Infrastructure, Industrial Production; |

|

|

3 |

a) Bachelor's degrees in the areas of Applied Social Sciences, Human Sciences and related areas; |

|

b) Advanced Technology Programmes (Tecnologias) in the areas of Management and Business, School Support, Hospitality and Leisure, Cultural Production and Design |

Source: Adapted from Regulatory Ordinance no 19, of 13 December 2017 (MEC, 2017[6])

Both the general competencies and discipline-specific sections of ENADE are marked out of 100, generating ‘raw’ marks out of 100 for each section, for each participating student. These are combined, with general competencies accorded a weighting of 25% and the discipline-specific section 75%, to generate an overall average ‘raw’ mark per student and per programme. Data from the 2016 round of ENADE (INEP, 2017[13]) show that average marks on the general competencies section, which is the same for all students, ranged from 38.2% for students from Advanced Technology Programmes in cosmetology to 60.3% for (bachelor’s degrees in) medicine. Average marks for the discipline-specific components, which are not comparable between disciplines, ranged from 38.3% in physiotherapy bachelor’s programmes to 67% in medicine.

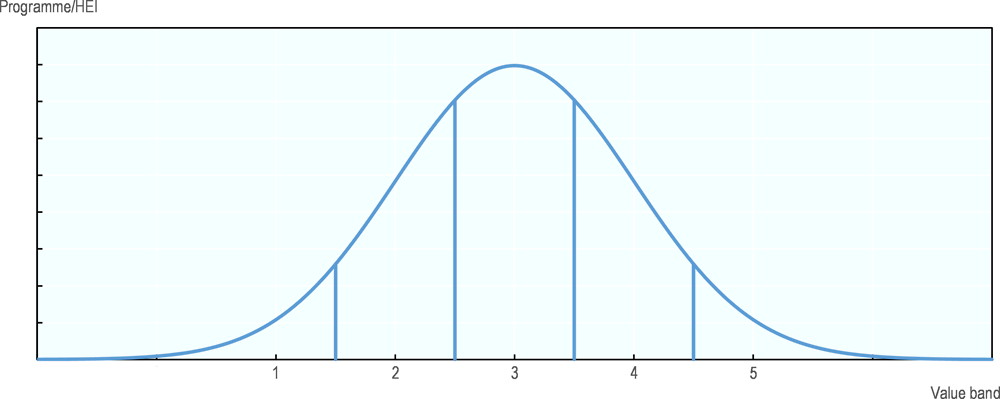

The raw average values for each programme in a single field are then standardised by calculating their standard deviation (distance from the mean score for programmes in a given field) and attributing the standard deviations to value bands from one to five, as shown in Figure 5.2 (INEP, 2017[14]). Outliers are excluded in setting the minimum and maximum scores. This process is carried out for all programmes with at least two graduating students participating in the exam. The resulting score from one to five for each programme is the ENADE score or Conceito ENADE. 40% of programmes evaluated in 2016 received an ENADE score of three and 6% a score of five (INEP, 2017[13]).

Figure 5.2. Standardisation of ENADE scores

Source: INEP (2017) Presentation ‘Enade 2016 Resultados e Indicadores – DAES, setembro 2017’. (INEP, 2017[13])

The administration of ENADE is a complex exercise. Every year, INEP coordinates the development of tests that include 30 discipline-specific items for numerous fields (27 in 20185). The agency oversees the implementation of these tests on a single day for around 200 000 students from over 4 000 programmes in 1 000 HEIs across a vast country; and coordinates the marking of the exam papers, attribution of scores and calculation of resulting indicators.

However, since its inception in 2004, ENADE has been subject to criticism, especially from within the Brazilian academic community. Based on the evidence gathered during the review, the OECD review team considers that there are at least five principal weaknesses in the way ENADE is currently designed and implemented.

1. The first problem relates to the participation of students and their motivation to make an effort in the test. It is evident that a proportion of the students who should be taking the test each year are not doing so. Across years, between 10-15% of students registered to take the test each year do not turn up on the day. Moreover, there are concerns among stakeholders in Brazil that some HEIs seek to avoid registering a proportion of students for ENADE. This may either be through maintaining deliberate ambiguity about the attribution of programmes to an ENADE test field – a problem recently highlighted by Brazil’s Federal Court of Accounts (TCU, 2018[15]). Alternatively, it may occur as a result of deliberate policies by HEIs to ensure the academic progress of “weak” students is slowed, so that they are not scheduled to graduate in a year when their discipline is subject to ENADE and thus avoid taking the exam.

At the same time, ENADE is a high stakes exam for HEIs (as it is used in the quality rating of their programmes), but a low stakes exam for students. Although attendance is compulsory, ENADE scores have no effect on students’ academic record and there is evidence that a significant proportion of students do not complete large parts of the test (Melguizo and Wainer, 2016[16]). Although some institutions organise prizes for ENADE participation, there is no systematic use of incentives for success in the exam. Evidence from other OECD and partner countries suggests that if the results of tests have no real consequences for students, this impacts negatively on student motivation and performance (Wolf and Smith, 1995[17]; Finney et al., 2016[18]). Moreover, interviews with representatives of HEIs conducted during the review visit to Brazil suggest that ENADE is taken more seriously by both students and staff in less prestigious for-profit institutions, than in public institutions. This appears to be primarily because the results of ENADE have a greater potential impact on the reputation of private institutions, which have to compete for students (public institutions are free and thus usually oversubscribed). This, and the participation issues, have negative implications for the validity of the results as an accurate reflection of the learning outcomes of all students and for the comparability of results between programmes and institutions.

2. A second concern relates to the development, selection and use of test items for each ENADE test. At present, there is no robust methodology to ensure that the difficulty of each test item is taken into account in the composition of the test and thus that a) tests in the same field are of equivalent difficulty between ENADE cycles and b) tests in different fields are of a broadly similar level of complexity. This means that it is not possible to compare the raw results or the Conceito ENADE between years or between disciplines. Unlike in external school leaving exams across the world, no reliable attempt is made to ensure exams are of consistent difficulty between years or that an exam in, say, philosophy is of broadly equivalent complexity in relation to expected learning outcomes to ones in maths or chemistry. Some differentiation in expected standards is important. For example, a bachelor’s degree would be expected to take students to a higher level than an Advanced Technology Programme in a related subject. However, it is reasonable to expect all ENADE exams for equivalent levels (bachelor’s degrees, short-cycle degrees) to test students at an equivalent level in relation to the expected learning outcomes for their programme.

A related question is whether the number of discipline-specific items included in ENADE (30) is adequate to generate a reliable indication of students’ learning outcomes from an undergraduate programme. The answer almost certainly depends on what the exam is for. A robustly designed examination with only 30 items, may be able to provide a general indication of a students’ level of knowledge and competencies in a specific disciplinary field. However, such a test is unlikely to provide reliable evidence of students’ performance in specific sub-fields or aspects of the curriculum, which limits its usefulness as a tool to help teaching staff and institutions improve the design of their programmes.

3. A third problem is that there are no explicit quality thresholds or expected minimum levels of performance for ENADE tests. “Raw” scores (out of 100) are widely published and discussed, with a frequently expressed assumption that students are not performing well (EXAME, 2017[19]). However, the absence of a clearly calibrated level of difficulty in tests means it is impossible to say whether a score of 50% represents good or bad performance. If the test is set at a high level of difficulty, it might be a very good mark, if the test is at a low level, it would not be a good mark. Without tests of a comparable standard of difficulty and without defined quality thresholds (pass, good, excellent, etc.), ENADE scores are simply numbers, reported according to their position to all other scores in the same test. It is thus impossible to know if students in programmes that achieve 50% or 60% in ENADE are performing well or poorly.

4. A fourth problem relates specifically to the design of the general competencies (formação geral) component of ENADE. This is currently composed of general knowledge questions regarding current affairs and social issues, including two questions that call for short discursive answers. This reflects the requirement of the 2004 legislation that ENADE test the wider knowledge and understanding of students of issues outside the scope of their studies. However, as noted, this is a flawed objective. Unless all undergraduate programmes have knowledge of current affairs and social issues as explicit intended learning outcomes – which is not the case – it is unreasonable to judge individual programmes on students’ performance in these areas. It noteworthy that ENADE does not include questions designed to test students’ logical reasoning or similar generic competencies that one might reasonably expect all higher education graduates to possess.

5. A final issue is that the standardisation of ENADE scores compounds the lack of transparency about what ENADE results really mean. As noted, raw marks are simply attributed to a five-point scale based on the standard distribution of scores in a single subject in a given year. As tests may vary in difficulty and students obtain very different distributions of scores, where a programme falls on a standard distribution of the scores for all programmes says little about the actual quality of the programme in question. In simple terms, scoring a three in one discipline in a particular year may require a far higher level of performance than scoring a three in another discipline in the same year or the same discipline in another round of ENADE. If all students score low marks – and thus all programmes are performing poorly - the distribution will be skewed towards the lower end of the performance scale, but as the bar (average) is set low, programmes will still emerge as having scores of three and more.

Effectiveness: use and effects of ENADE results

The ENADE score is published separately for each programme in the e-MEC online platform (MEC, 2018[20]) and subsequently used as an input to the Preliminary Course Score (CPC), discussed in more detail below. The CPC is used by SERES to make regulatory decisions on whether programmes should have their official recognition renewed directly every three years, or should undergo a further on-site inspection (MEC, 2017[2]). ENADE results are thus used by Brazilian authorities to judge whether programmes are of adequate quality to allow their continued operation. The results of ENADE are also widely reported in Brazilian media and, in some cases, used by institutions as part of their marketing efforts, alongside the programme and institutional quality scores.

Students have access to their own ENADE results, but it is unclear to what extent they actually have an interest in these, given the low importance of the test for their own careers. Importantly, the OECD team understands that institutions, and staff in programmes, do not have access to the individual scores for their programmes. Institutions consulted by the OECD review team report that they did not use of ENADE results in efforts to improve the design and content of programmes. During the review visit, representatives of institutions consistently indicated that they did not see ENADE as providing useful feedback to help them improve their programmes. This is a pattern confirmed by recent studies on the use of ENADE results in HEIs in Brazil (De Sousa and De Sousa, 2012[21]; Oliveira et al., 2013[22]; Santos et al., 2016[23]). In contrast, some HEI representatives consulted by the OECD team, in line with the findings of the same studies, highlighted the use of ENADE results in marketing programmes to prospective students and promoting their institutions.

Efficiency: the cost-effectiveness of ENADE

Although the OECD review team does not have access to a detailed breakdown of the costs of implementing ENADE, these account for a substantial part of INEP’s budget for evaluation of higher education, which amounted to over 118 million reals (USD 30.7 million) in 2017 (INEP, 2018[24]). It is questionable whether the quality and usefulness of the results achieved with the exam as currently configured justify the investment of public resources committed. As noted, through their use in the CPC, ENADE results are used by MEC as an important indicator of the quality of undergraduate programmes in Brazil.

The first question is therefore whether ENADE provides an accurate indicator of programme quality. For the reasons outlined above, it is the view of the OECD review team that, in its current form, it does not. The second question is whether an improved version of ENADE, addressing the current design and implementation weaknesses noted in the preceding section, would be generate information about the quality of undergraduate programmes that could not be provided by other, potentially more readily available, indicators. The third question is whether, even if an improved ENADE brought additional information about quality that could not be provided by other indicators, this additional information justified the considerable costs of designing and implementing such a system of standardised testing. These are questions that the Brazilian authorities and academic community should consider in planning the future of the federal quality assurance and regulatory regime for higher education.

Monitoring programme performance: use of programme indicators

Relevance: rationale and objectives of the current system

INEP and MEC use a set of programme-level indicators, drawing heavily on ENADE results, to monitor the ongoing performance of undergraduate programmes in the federal system of higher education. The legal basis for this is, in principle, provided for in the 2004 legislation establishing SINAES, which states that evaluation of programmes “shall use diversified procedures and instruments, among which must be visits by expert committees from the respective areas of knowledge” (Presidência da República, 2004, p. art.4[1])”. On-site reviews are always used as a basis for initial recognition of undergraduate programmes, but are not used systematically in the ongoing monitoring of programme performance and the periodic renewal of programme recognition. As discussed below, in many cases, SERES makes judgements about the quality of programmes and approves the renewal of their official recognition based on programme indicators generated by INEP.

A recent MEC implementation ordinance for SINAES (MEC, 2017[6]) states that INEP has the responsibility to calculate and publish indicators of the quality of higher education, in line with methods established in technical notes approved by CONAES (the supervisory board for the higher education evaluation system). It does not, however, specify in detail what these indicators should be. The same ordinance states simply that indicators produced by INEP are to “support” (subsidiar) public policies in higher education. In practice, however, centrally collated programme indicators play a central role in the federal quality assurance system. The current indicators and methods used, as well as their application in regulation and supervision by SERES, are specified in technical notes prepared by MEC and INEP (MEC, 2017[2]; INEP, 2017[22]).

In the current system, INEP and MEC use indicators as a means to identify potentially poor quality programmes that warrant more in-depth evaluation and supervision. Programmes that score below three out of five on the composite Preliminary Course Score (CPC) after each three-year ENADE cycle are systematically subject to on-site inspections by external review commissions, with a positive evaluation score (a CC of three or above) a pre-requisite for renewal of their official recognition. Courses that score three or above on the CPC generally have their programme recognition renewed automatically by SERES (MEC, 2017[2]).

In a system as large as Brazil’s, with a wide diversity in the quality of provision, there is a clear rationale for using centrally collated indicators to monitor programme quality. Notwithstanding the minimum quality guarantees provided by the recognition process, wider quality concerns in the higher education system in Brazil, particularly in parts of the for-profit private sector, mean that ongoing monitoring of programmes by public authorities is justified. However, in a system of such size, it is challenging to conduct regular programme-level reviews for all active undergraduate programmes, as is the practice in some smaller OECD higher education systems (such as the Netherlands or Portugal, for example).

Despite the practicality of an indicator-based approach, some commentators in Brazil consulted by the OECD review team question whether dispensing with on-site reviews for some programmes in favour of indicator measures is consistent with the spirit of the 2004 legislation (which says programme evaluation must involve on-site visits). More fundamentally, the question is which indicators to use to monitor programme quality and how to combine these in meaningful ways.

Effectiveness: quality indicators used or generated

To monitor programme performance, INEP currently uses a set of indicators comprising a) measures of student performance and assumed learning gain (based on ENADE test results); b) the profile of the teaching staff associated with the programme and; c) feedback from students about teaching and learning, infrastructure and other factors, from the questionnaires they complete in advance of taking the ENADE test. When new ENADE results are available for each programme, after each three-year cycle of testing, INEP calculates a programme score – the Preliminary Course Score or Conceito Preliminar de Curso (CPC) using the weightings set out in Table 5.2.

Table 5.2. Indicators used to calculate the CPC

|

Dimension |

Components |

Weights |

|

|---|---|---|---|

|

Student performance |

Score from students taking ENADE |

20.0% |

55% |

|

Indicator of Difference between Observed and Expected Performance (IDD) |

35.0% |

||

|

Staff (Corpo Docente) |

Proportion of Masters |

7.5% |

30% |

|

Proportion of PhDs |

15.0% |

||

|

Score for employment status of staff (regime de trabalho) |

7.5% |

||

|

Student perception about the educational process |

Score relating to the organisation of teaching and learning |

7.5% |

15% |

|

Score relating to physical infrastructure |

5.0% |

||

|

Score relating to additional academic and professional training opportunities |

2.5% |

||

Source: INEP (2017) Nota Técnica Nº 3/2017/CGCQES/DAES (INEP, 2017[22])

Under “student performance”, the ENADE score (Conceito ENADE) discussed in the previous section is complemented by an indicator of the assumed “added value” of the programme for each student’s performance in ENADE. The Indicator of difference between observed and expected performance (Indicador da Diferença entre os Desempenhos Observado e Esperado) or IDD is calculated by comparing each student’s actual results in ENADE with the performance that would be expected on the basis of their previous performance in the national high school leaving exam, ENEM (Exame Nacional do Ensino Médio).

This process uses results data associated with each individual’s unique identification number (número do Cadastro de Pessoas Físicas or CPF). The “expected” performance for each student in ENADE in relation to the total population of ENADE participants is calculated on the basis of ENEM results using a regression model. This is then compared with the student’s actual performance in ENADE. The difference between the expected and observed performance is considered as the added value of the programme (positive or negative). The average differences for all students6 in a single programme are combined to create an IDD score for the programme (INEP, 2017[23]).

The data on the composition of staff are drawn from INEP databases and awards higher ratings to programmes with higher proportions of teaching staff with master’s and doctoral degrees and with full-time, permanent status. This tends to reward public institution that have higher proportions of staff with doctorates (see Figure 3.7) and full-time contracts (see Figure 3.3).

The data on student feedback are drawn directly from the online student questionnaire that students have to complete as part of their registration for ENADE. The 2017 questionnaire contained 26 questions asking for biographical details and a further 41 questions focused on the programme (INEP, 2018[24]). Raw data for the student questionnaire results and staff composition are converted into standardised scores for each programme.

The CPC has been criticised in Brazil for several reasons. Criticisms focus on the choice of indicators, the weighting attributed to them and the way they are combined into a single composite indicator. The reliability of the ENADE score as an indicator of programme quality was discussed above. The IDD, which accounts for 35% of the CPC score, is both contested and poorly understood in the wider academic and policy community in Brazil.

The objective of measuring the added value of a programme for the knowledge and skills of students (learning gain) is, in principle, commendable. Not only does it go to the heart of educational effectiveness (how much a student actually learns during their programme), but measuring “added value” also makes it possible to take into account and reward the efforts made by programmes that take in weaker students, often from less advantaged social groups. A measurement of learning gain can, in principle, make it possible to identify programmes that successfully help students with lower levels of knowledge and skills on entry to increase their knowledge and skills over the duration of the programme, even if the final performance of these students remains lower than in programmes that took in high performing students. Added value could thus be a means to recognise the work of less prestigious programmes and institutions that perform a valuable societal role.

However, the IDD as currently calculated in Brazil is not a true measure of learning gain, but a proxy indicator, based on the following assumptions:

1. That students’ performance at the age of 18 in general, high-school-level tests in natural sciences, humanities, languages and maths (INEP, 2017[23]) is a reliable basis on which to predict their future performance in tests designed to measure their learning outcomes after a specialised undergraduate degree.

2. That ENADE accurately measures students’ performance at the end of their undergraduate programme.

3. That when students perform better or worse than their predicted relative performance, this results primarily or significantly from the design and delivery of their undergraduate programmes.

The first assumption is not unreasonable. However, the limitations of ENEM results as a predictive indicator must be fully acknowledged and the results of the regression analysis (the predicted relative performance of students at the end of their undergraduate studies) must be treated with due caution. The subject composition and different stakes involved in ENEM and ENADE are likely to reduce the predictive power of the IDD calculations. Not only will ENEM subjects differ considerably in scope and depth from the subjects included in the disciplinary component of ENADE, but, as highlighted earlier, ENADE is a low stakes exam for students. In contrast, ENEM is comparatively high stakes exam, the result of which have a major impact on students’ chances of accessing higher education. Depending on their profile, the relatively high degree of specialisation of higher education programmes might increase some students’ chances of performing well, compared to generalist high-school exams (assuming they chose to study fields in higher education that correspond to their strengths and interests). Conversely, the low stakes of ENADE tests may reduce the chance of their performing to their maximum potential.

The second assumption is problematic. As discussed above, as well as their low-stakes status, the composition and design of ENADE tests limit their effectiveness as measures of learning outcomes.

These factors also reduce the reliability of the third assumption above. All quality assurance procedures make assumptions about the impact of programme design and delivery on students’ performance. It is certainly possible that programmes will have some influence on students’ performance in the current ENADE tests and that significant differences between real and expected performance, as calculated by the IDD, are due to programme-level factors. However, the combination of the boldness of the underlying assumptions, the poor design of ENADE and the potential influence of factors outside the control of the programme on student performance mean that the IDD provides only limited information on programme quality. It is thus highly questionable whether it should account for 35% of the weight in a composite indicator used as a basis for renewing programme recognition.

The legislation establishing ENADE actually calls for the testing of both first and final year students, in order to allow a direct comparison between their results on entry to, and exit from, undergraduate programmes. This system was implemented between 2004 and 2010. However, the test for incoming students was abandoned, largely on cost grounds, and the current system using ENEM introduced as a substitute. Although testing on entry and exit from a course with coordinated and well-calibrated testing tools also involves many challenges, the OECD team considers it is the only realistic way to measure learning gain within programmes, if this is the real objective of quality assurance authorities.

The indicators used for the composition of teaching staff and student feedback are less ambitious in their aims and less fundamentally problematic. However, by rewarding staff with PhDs and full-time status, the indicators for teaching staff are designed for academic, research-oriented institutions and fail to take into account the value of part-time teachers with professional experience, who are vital for more professionally oriented programmes.

The use of student feedback as an indicator is a positive element in the system. Students are the main stakeholders in the higher education process and their views need to be heard within a well-designed quality assurance system. However, the questionnaire used is long and formulated using excessively bureaucratic language (INEP, 2018[24]). Moreover, it is not clear whether students in Brazil, who sit the ENADE tests in their own institutions, are accustomed to providing honest and objective feedback about their teachers and programmes throughout their studies and whether they are positively encouraged to do so in ENADE. In particular, a concern to maintain the reputation of the institution that has awarded their diploma may make students hesitant to provide negative feedback.

It is widely accepted, including in the recent report from the Federal Court of Accounts (TCU, 2018[15]), that the weightings attributed to the different indicators in the CPC are arbitrary, with no discernible scientific basis. This further compounds the lack of transparency for students, families and society at large about what the scores attributed to courses really mean in practice. It is possible – although the OECD review team is not aware of specific studies – that the current weightings in the CPC formula have a significant impact on where programmes fall in standard distributions and thus their CPC score.

It is positive that the CPC sets out to include indicators of the teaching process (through the imperfect proxy of teaching staff status); qualitative feedback from students (the main beneficiaries of the system) and measures of student learning outcomes. It does not, however, contain a measure of the attrition rate of students (what proportion of students entering a programme complete it) or the subsequent employment outcomes of graduates. Both these factors – although especially the first - are taken into account in quality-related policies in other higher education systems.

Effectiveness: use and effects, efficiency and cost-effectiveness

In light of the shortcomings of the set of indicators employed and the arbitrary weighting of the different factors, a key concern is the way the CPC is currently used in the broader quality assurance and regulatory process for undergraduate provision. As discussed, programmes that score three or above, in most cases, have their recognition renewed automatically until the next ENADE cycle, at which point a new CPC is calculated7. Those that score two or less are systematically subject to a review visit (discussed below), which provides an updated programme score (CC) as a basis for the regulatory decision on whether or not to renew recognition.

As argued earlier, the principle of using indicators to identify “at risk” programmes and target scarce resources for on-site inspections makes sense, especially in a system as big as Brazil’s. However, the CPC does not provide a reliable mechanism to identify poorly performing courses. The absence of quality thresholds in ENADE and the standardisation processes used to create the ENADE score, combined with the weaknesses of the IDD, mean it is far from clear whether a CPC score of three represents an adequate standard of quality or not. A reform of the monitoring indicators used and the way they are combined is necessary.

Monitoring programme performance: use of on-site inspections

Relevance: rationale and objectives of the current system

When programmes are identified through the CPC as performing poorly – often meaning they have poor relative performance in ENADE – they are subject to an on-site inspection by external evaluators, coordinated by INEP (MEC, 2017, p. 5[2]). The evaluators assess the supply conditions for the programme using the same evaluation template that was already used for programme recognition (reconhecimento) and was discussed in Chapter 4 of this report (INEP, 2017[3]). The results of the new on-site inspections triggered by the CPC process or special requests from SERES are used as a basis for decisions for programmes’ renewal of recognition.

As noted, the objective of targeting on-site inspections on weakly performing programmes has advantages, as the systematic use of periodic on-site inspections for all programmes in Brazil would almost certainly be unfeasible for logistical and financial reasons. However, it also means programme-level site visits at this stage in the evaluative process always have a punitive character and that peer reviewers are not exposed to good practice in well-established programmes, which could inform their judgements about, and recommendations to, poorly performing programmes.

The objective of the on-site visits for renewal of recognition, as currently conceived, is to (re)check compliance with basic standards, rather than explicitly to promote and support improvement of the programmes concerned, following a serious self-evaluation. The formal objective for the renewal of recognition visits expressed in the relevant regulation (Presidência da República, 2017[25]) is for them to inform the process of renewal of recognition. The extent to which quality assurance should seek to support institutions in quality improvement is open to debate in a highly commercialised system like that in Brazil, although most quality assurance systems worldwide do seek to support quality enhancement, as well as basic compliance.

Effectiveness: quality indicators used and generated

The indicators used in the evaluation template for recognition and renewal of recognition of programmes were discussed in Chapter 4. A clear problem with these indicators in relation to renewal of recognition is that they focus on exactly the same inputs and processes as examined in the initial recognition of the programme, when the first cohort of students had only completed between 50-75% of the course workload, and before any students had graduated. The courses that undergo renewal of recognition on-site inspections are identified primarily because of their poor performance on an – albeit imperfect – set of indicators of output and student feedback. Rather than directly examining the problems identified by poor performance in ENADE or poor student feedback, the on-site evaluators complete a questionnaire measuring variables that have already been verified in an earlier inspection. Moreover, these variables in many cases might be expected to remain constant over time.

It should be recalled that the evaluation template for recognition and renewal of recognition places a 40% weighting on the category “teaching staff” and 30% on “infrastructure”, with the remaining 30% on teaching and learning policies and practices. The indicators and judgement criteria relating to teaching staff mostly focus on the qualifications and experience of the individuals in question, with only three indicators dealing with the activities (atuação) of staff or their interaction with each other.

It is conceivable that some, very poor quality, providers do not maintain the basic infrastructure and teaching workforce to allow their programme to operate correctly and that were initially verified in the recognition process. However, for programmes that have maintained the basic conditions for providing the programme, the balance of indicators in the current evaluation template does not generate overall scores that will reveal the most obvious signs of poor quality. A greater focus on teaching activities and outputs and outcomes (attrition rates, learning outcomes, graduation rates and employment outcomes), would make the evaluation template more effective in identifying the real causes of poor performance.

Effectiveness: use and effects, efficiency and cost-effectiveness

Programmes are inspected at this stage in the evaluation cycle on the grounds that they have scored poorly on the CPC measures of process and outcomes. The resulting inspection then attributes a new quality score – an updated Conceito de Curso (CC) – that effectively replaces the CC attributed at the time of initial recognition and exists alongside the CPC score in the e-MEC system. The CC is, however, based on entirely different indicators from the CPC, despite the very similar names.

Frequently, it appears that programmes which score poorly on the CPC measure subsequently achieve a higher score on the CC (TCU, 2018[15]). As such, these programmes nominally recover the higher quality score. It is entirely understandable that the CPC and the inspections leading to the CC can generate different values. They measure almost entirely different things.

From a conceptual perspective, this is all the more problematic because the more output-focused measures contained in the CPC would – if calculated on a more reliable basis – provide a better indication of the real performance of the programme. Curriculum plans, teachers and infrastructure are all enabling factors for good education and are rightly considered in initial programme approval. However, notwithstanding the potential for staff to leave the programme and infrastructure to be changed, these factors are likely to remain constant over a number of years. Once there is evidence of the broader performance and outcomes of programmes, this evidence should be prioritised in assessments of quality. In the end, if a well-designed programme with good infrastructure and well-qualified teachers fails to train students effectively without very good reasons, the programme is not of high quality.

5.3. Key recommendations

1. Undertake a thorough assessment of the objectives, costs and benefits of large-scale student testing as part of the quality assurance system

Officially ENADE currently seeks to assess students’ acquisition of knowledge and skills specified in the relevant National Curriculum Guidelines (DCN) or the equivalent documents for Advanced Technology Programmes, as well as their understanding of unspecified “themes outside the specific scope” of their programme. This is an unrealistic objective and no standardised test could achieve this. Moreover, as discussed in the preceding analysis, the current design and implementation of the ENADE tests are characterised by significant weaknesses. At present, ENADE results are used extensively as a basis for regulatory decisions (renewal of programme recognition), but are not used by institutions and teachers to identify areas where they programmes need to be strengthened.

Given the long-standing commitment of Brazil’s public authorities to standardised testing of tertiary students, there are sunk costs and considerable expertise in implementing large-scale testing has been developed. Politically, ENADE is widely accepted and viewed by many as an important part of Brazil’s system for quality assurance in higher education.

The OECD team believes, however, that, in its current form, ENADE does not represent an effective use of public resources. As such, as a basis for decisions on the future of the system, a thorough reflection is needed about the objectives of large-scale standardised testing in Brazilian higher education and the costs and benefits of different approaches to implementing it. The main questions to answer are:

1. Can an improved version of ENADE, addressing the current design and implementation weaknesses noted in this report, be implemented and generate reliable information about the quality of undergraduate programmes?

2. Could the information about the quality of programmes generated by a revised ENADE be provided by other, potentially more readily available, indicators? What is the specific and unique added value of ENADE results?

3. If a revised version of ENADE does indeed have the potential to generate valuable information that cannot be obtained from other sources, does the value of this information justify the costs of implementing ENADE? How can the costs of implementation be minimised, while still allowing ENADE to generate reliable and useful results?

The OECD team believes two factors should be considered in particular. First, for ENADE to have the greatest possible added value, it needs to be able to provide reliable information that can help teachers and institutions to identify areas of weakness in their programmes (in terms of knowledge coverage or skills development). ENADE results cannot simply be a blunt indicator used to inform the regulatory process, as other indicators such as attrition rates or employment outcomes could be used for this purpose. Second, the current requirement to apply the ENADE test to all programmes every three years increases the fixed cost of implementing the system. It is important to consider whether sampling techniques could be deployed to reduce costs, while maintaining reliability.

2. If a reformed version of ENADE is retained, ensure the objectives set for the exam are more realistic

If the decision is taken to maintain a revised version of ENADE, it is crucial to ensure the objectives set for it in the relevant legislation and implementing decisions are realistic and clearly formulated. The objective of a reformed ENADE could be to provide:

An indication – rather than a comprehensive picture - of the performance level of students in relation to intended learning outcomes, as one indicator, alongside others, in a comprehensive system of external quality evaluation and;

Data on student performance that can be used directly by teachers and institutions in identifying weaknesses in their programmes as a basis for improvement (quality enhancement).

To achieve these objectives, the test should focus on measuring knowledge and skills that programmes explicitly set out to develop in their students. This means abandoning claims to measure abstract general knowledge with no direct link to the programme and focusing on a) selected discipline-specific knowledge and skills and b) generic competencies that can realistically be developed in an undergraduate programme. The latter category might include critical thinking and problem-solving. These can theoretically be tested for using discipline-specific test items. Indeed, the authors of the recent outputs of the European COLOHEE project argue that generic competencies are best assessed using discipline-specific test items (CALOHEE, 2018[11]).

3. Improve the design of ENADE tests to ensure they generate more reliable information on learning outcomes that can also be used by teachers and HEIs

If maintained, ENADE tests should be designed in a more rigorous way to ensure that they are of comparable levels of difficulty within subjects from one year to the next and that tests for different disciplines are of equivalent difficulty for equivalent qualifications (bachelor’s, advanced technology programme, etc.). This may require a shift from classic test theory to item-response theory.

As part of this process, performance thresholds and grades should be established clearly in advance. The objective to be to provide students with easily understood grades and programmes with easily understood and usable grade-point averages and grade distributions. The approaches to both test design and performance thresholds used by CENEVAL in Mexico or testing organisations in the United States could provide valuable inspiration on how a revised form of the ENADE tests could be developed. It is important for INEP to draw on the expertise of other organisations involved in standardised testing internationally in the development of new approaches and test formats, to ensure it benefits from a wide range of expertise.

4. Explore ways to make the results of ENADE matter for students

If maintained, ENADE needs to be made into a higher stakes exam for students, so that they make an effort to actually demonstrate the level of knowledge and skills they possess. Currently, it is difficult to make ENADE results count towards individual’s degree scores, not only because of institutional autonomy, but because only every third cohort has to take ENADE and including ENADE in degree results may be perceived as unfair to students in a year where the test exists.

At the least, the ENADE score could be included in the students’ diploma supplement. Alternatively, ENADE could be made into a curriculum component for the years in which, or – in the case of sampling - for the students to whom, it is administered with the requirement that an equivalent test for students in other years be administered by institutions. It is not yet clear if this would be possible legally.

5. Introduce a new indicator dashboard, with a broader range of measures, to monitor programme performance and identify “at risk” programmes

The use of the Preliminary Course Score (CPC) cannot be justified in its current form for the reasons discussed above. However, systematic programme level data is a crucial tool for monitoring a system as diverse and variable in quality as Brazil’s. The most promising option would be to include a broader set of more transparent indicators in an ongoing monitoring system, with thresholds established to indicate “at risk” performances on different indicators. This information could then be used to inform regulatory decisions and feed into subsequent evaluation steps (such as on-site reviews). The system should apply to all programmes, with data obtained from institutions and other sources, as appropriate, and consolidated in a renewed version of e-MEC.

Such a system could use a more diverse set of indicators of teaching staff, real (not standardised) ENADE results (based on established performance thresholds), an indicator of drop-out rates and, when possible through linking data sources through the CPF number, information on employment rates and earnings. Indicators of the socio-economic profile of students could be included in the system, with higher tolerances for issues like drop-out or ENADE performance for programmes with intakes from lower socio-economic groups. Such variation in tolerances should be limited, as all students should be expected to reach minimum standards and all programmes maintain a certain proportion of their students.

A revised form of the IDD could potentially be maintained alongside the other indicators in the indicator dashboard, provided its status as a proxy for expected performance and its limitations are made clear, and its weight in the overall monitoring system is reduced. However, even a revised IDD is likely to remain a complex indicator that may not always be well understood by the public and stakeholders in the higher education system. The costs and benefits of maintaining such a comparatively un-transparent measure should be assessed. If, in the longer term, resources permit, a return to examination on entry and exit from programmes could be considered, although the costs and benefits of any such system should be considered carefully.

The OECD review team understands that INEP is already planning (October 2018) to “disaggregate” the components of the CPC and complement these with additional indicators to inform the regulatory process. Hopefully, this recommendation will support this process.

6. As part of a new system of institutional accreditation, exclude institutions with demonstrated internal quality assurance capacity from on-site programme reviews for the duration of their accreditation period

As discussed in Chapter 7 there is scope to exempt institutions from systematic programme level review that have a track record of good performance and that can demonstrate a high level of internal quality assurance capacity. This would require existing systems for institutional accreditation and re-accreditation to be strengthened. If problems are identified in relation to programme indicators in the indicator dashboard, such institutions would be responsible for addressing these issues internally. Addressing poor quality would become a key focus of institutional review and poor performance or failure adequately to address problems could lead institutions losing self-accrediting status in the subsequent round of institutional review. This move would reduce some of the burden of external programme-level reviews for renewal of recognition (as well as the initial recognition process).

7. Maintain programme-level supervision for other institutions, with targeted on-site reviews for poorly performing programmes and randomly selected highly performing programmes.

For the remaining institutions, programme-level review would be maintained. The new programme-level indicator dashboard (which would cover all programmes, including in self-accrediting institutions) would allow poor programmes to be identified and replace the current CPC system. If annually collected data on completion rates and employment outcomes were included in the dashboard, alongside input indicators and periodic results from a reformed ENADE, this would allow more effective continuous monitoring of programmes.

Problematic programmes could first be called upon to submit an improvement plan that could be assessed remotely, largely in line with current supervision procedures. SERES, or a future quality assurance agency (see below), could decide on timeframes for improvement and whether and when an on-site visit would be required. It is crucial that SERES, or a successor agency, have the capacity to close poor programmes rapidly if programme indicators fail to improve without clear justification and evaluators give a negative assessment following an on-site inspection.

However, while targeting of resources is important, the risk of evaluators only being exposed to poor quality programmes – and thus lacking good reference points – needs to be addressed. As such, it is recommended that reviewers also take part in reviews of randomly selected programmes that obtain good scores in relation to monitoring indicators – potentially including programmes in “self-accrediting” institutions - to allow them to gain more insights into the range of practices and performance that exists in their field in the country.

8. Develop a separate evaluation instrument for on-site reviews of established programmes

The current process for on-site reviews of established undergraduate programmes uses the same evaluation and judgement criteria as the instrument for programme recognition (which occurs when the first student cohort has completed between half and three-quarters of the programme). This instrument pays insufficient attention to programme outputs and outcomes (notably the results of (a revised) ENADE, attrition and graduation rates and employment outcomes) and to the teaching and student support practices that would be expected to have the greatest influence on these outputs and outcomes. A new instrument should thus be developed for on-site reviews of established programmes, which places most emphasis on these factors. The earlier suggestion for an inspectorate to examine infrastructure and basic institutional policies would mean that site visits by peer reviewers should focus exclusively on the learning environment and possible causes of poor outputs and outcomes.

References

[11] CALOHEE (2018), CALOHEE Outcomes Presented - CALOHEE, https://www.calohee.eu/ (accessed on 16 November 2018).

[7] CEDEFOP (2016), Application of learning outcomes approaches across Europe: A comparative study, Publications Office, Luxembourg, http://dx.doi.org/10.2801/735711.

[21] De Sousa, B. and J. De Sousa (2012), “Resultados do Enade na Gestão Acadêmica de Cursos de Licenciaturas: Um Caso em Estudo”, Estudos em Avaliação Educacional, Vol. 23/52, pp. 232-253, http://publicacoes.fcc.org.br/ojs/index.php/eae/article/view/1938/1921.

[19] EXAME (2017), Estudantes acertam menos de 50% das provas específicas do Enade (Students score less than 50% on discipline-specific ENADE tests), EXAME, https://exame.abril.com.br/brasil/estudantes-acertam-menos-de-50-das-provas-especificas-do-enade/ (accessed on 16 November 2018).

[18] Finney, S. et al. (2016), “The Validity of Value-added Estimates from Low-Stakes Testing Contexts: The Impact of Change in Test-Taking Motivation and Test Consequences”, Educational Assessment, Vol. 21/1, pp. 60-87, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10627197.2015.1127753.

[4] ICFES (2018), Información general del examen Saber Pro, Instituto Colombiano para la Evaluación de la Educación, http://www2.icfes.gov.co/estudiantes-y-padres/saber-pro-estudiantes/informacion-general-del-examen (accessed on 13 November 2018).

[27] INEP (2018), ENADE - Questionário do Estudante, Sistema ENADE, http://portal.inep.gov.br/questionario-do-estudante (accessed on 17 November 2018).

[24] INEP (2018), Relatório de Gestão do Exercício de 2017 do Instituto Nacional de Estudos e Pesquisas Educacionais Anísio Teixeira - Inep.

[13] INEP (2017), Enade 2016 Resultados e Indicadores, Diretoria de Avaliação da Educação Superior - Daes, Brasília, http://download.inep.gov.br/educacao_superior/enade/documentos/2017/apresentacao_resultados_enade2016.pdf (accessed on 16 November 2018).

[3] INEP (2017), Instrumento de Avaliação de cursos de graduação Presencial e a distância - Reconhecimento e Renovação de Reconhecimento (Evaluation instrument for undergraduate programmes - classroom-based and distance - recognition and renewal of recognition), Instituto Nacional de Estudos e Pesquisas Educacionais Anísio Teixeira, Brasília, http://www.publicacoes.inep.gov.br (accessed on 11 November 2018).

[25] INEP (2017), Nota Técnica No 3/2017/CGCQES/DAES (On the calculation of the CPC), Instituto Nacional de Estudos e Pesquisas Educacionais Anísio Teixeira, Brasília, http://download.inep.gov.br/educacao_superior/enade/notas_tecnicas/2015/nota_tecnica_daes_n32017_calculo_do_cpc2015.pdf (accessed on 16 November 2018).

[14] INEP (2017), Nota Técnica Nº 32/2017/CGCQES/DAES (Methodology for calculating the Conceito ENADE), Instituto Nacional de Estudos e Pesquisas Educacionais Anísio Teixeira, Brasília, http://download.inep.gov.br/educacao_superior/enade/notas_tecnicas/2016/nota_tecnica_n32_2017_cgcqes_daes_calculo_conceito_enade.pdf (accessed on 16 November 2018).

[26] INEP (2017), Nota Técnica Nº 33/2017/CGCQES/DAES (On calculation of the IDD), Instituto Nacional de Estudos e Pesquisas Educacionais Anísio Teixeira, Brasília, http://download.inep.gov.br/educacao_superior/enade/notas_tecnicas/2016/nota_tecnica_n33_2017_cgcqes_daes_calculo_idd.pdf (accessed on 17 November 2018).

[12] MEC (2018), Diretrizes Curriculares - Cursos de Graduação (Curriculum Guidelines - Undergraduate Programmes), Ministério da Educação, http://portal.mec.gov.br/component/content/article?id=12991 (accessed on 06 November 2018).

[20] MEC (2018), e-MEC Instituições de Educação Superior e Cursos Cadastrados (Registered HEIs and programmes), http://emec.mec.gov.br/ (accessed on 14 November 2018).

[2] MEC (2017), Nota Técnica Nº 13/2017/CGARCES/DIREG/SERES/SERES (setting out parameters and procedures for the renewal of recognition of programmes), Ministério da Educação, Brasília, http://portal.mec.gov.br/index.php?option=com_docman&view=download&alias=64921-nt-13-2017-seres-pdf&category_slug=maio-2017-pdf&Itemid=30192 (accessed on 15 November 2018).

[6] MEC (2017), Portaria Normativa No 19, de 13 dezembro de 2017 Dispõe sobre os procedimentos de competência do Instituto Nacional de Estudos e Pesquisas Educacionais Anísio Teixeira - INEP referentes à avaliação de instituições de educação superior, de cursos de graduação e de desempenho acadêmico de estudantes., Ministério da Educação, Brasília, http://www.abmes.org.br (accessed on 15 November 2018).

[16] Melguizo, T. and J. Wainer (2016), “Toward a set of measures of student learning outcomes in higher education: evidence from Brazil”, Higher Education, Vol. 72/3, pp. 381-401, http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10734-015-9963-x.

[9] NVAO (2016), Assessment framework for the higher education accreditation system of the Netherlands, Nederlands-Vlaamse Accreditatieorganisatie (NVAO), The Hague, https://www.nvao.com/system/files/procedures/Assessment%20Framework%20for%20the%20Higher%20Education%20Accreditation%20System%20of%20the%20Netherlands%202016_0.pdf (accessed on 17 November 2018).

[8] OECD (2013), Assessment of Higher Education Learning Outcomes Feasibility Study Report Volume 1 - Design and implementation Executive Summary, OECD, Paris, http://www.oecd.org/edu/ahelo (accessed on 16 November 2018).

[5] OECD (2018 (forthcoming)), The Future of Mexican Higher Education: Promoting Quality and Equity, http://Forthcoming.

[22] Oliveira, A. et al. (2013), “Políticas de avaliação e regulação da educação superior brasileira: percepções de coordenadores de licenciaturas no Distrito Federal”, Avaliação: Revista da Avaliação da Educação Superior (Campinas), Vol. 18/3, pp. 629-655, http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1414-40772013000300007.

[28] Presidência da República (2017), Decreto Nº 9.235, de 15 de dezembro de 2017 - Dispõe sobre o exercício das funções de regulação, supervisão e avaliação das instituições de educação superior e dos cursos superiores de graduação e de pós-graduação no sistema federal de ensino. (Decree 9235 of 15 December 2017 - concerning exercise of the functions of regulation, supervision and evaluation of higher education institutions and undergraduate and postgraduate courses in the federal education system), http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_Ato2015-2018/2017/Decreto/D9235.htm (accessed on 10 November 2018).

[1] Presidência da República (2004), Lei no 10 861 de 14 de Abril 2004, Institui o Sistema Nacional de Avaliação da Educação Superior – SINAES e dá outras providências (Law 10 861 establishing the National System for the Evaluation of Higher Education - SINAES and other measures), http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_ato2004-2006/2004/lei/l10.861.htm (accessed on 10 November 2018).

[23] Santos, M. et al. (2016), “O impacto das avaliações disciplinares no ensino superior”, Avaliação: Revista da Avaliação da Educação Superior (Campinas), Vol. 21/1, pp. 247-261, http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1414-40772016000100012.

[29] SIAFI (2018), Siafi - Sistema Integrado de Administração Financeira do Governo Federal - Main Expenditures INEP, Siafi - Sistema Integrado de Administração Financeira do Governo Federal.

[15] TCU (2018), RA 01047120170 Relatório de auditoria operacional. Atuação da Secretaria de Regulação e Supervisão da Educação Superior do Ministério da Educação - Seres/Mec e do Instituto Nacional de Estudos e Pesquisas Educacionais Anísio Teixeira - Inep nos processos de regulação, supervisão e avaliação dos cursos superiores de graduação no país. (Operational audit report: Activities of SERES/MEC and INEP related to regulation, supervision and evaluation of higher education programmes in the country), Tribunal de Contas da União, Brasília, https://tcu.jusbrasil.com.br/jurisprudencia/582915007/relatorio-de-auditoria-ra-ra-1047120170/relatorio-582915239?ref=juris-tabs (accessed on 13 November 2018).

[10] UKÄ (2018), Guidelines for the evaluation of first-and second-cycle programmes, Universitetskanslersämbetet (Swedish Higher Education Authority), Stockholm, http://www.uka.se (accessed on 17 November 2018).

[17] Wolf, L. and J. Smith (1995), “The Consequence of Consequence: Motivation, Anxiety, and Test Performance”, Applied Measurement in Education, Vol. 8/3, pp. 227-242, http://dx.doi.org/10.1207/s15324818ame0803_3.

Notes