Chapter 1 provides information on tax and non-tax revenues in 30 Asian and Pacific economies, including tax-to-GDP ratios for the region as a whole, sub-regions and for individual economies. It also contains information on tax structures, tax revenues by level of government and environmentally related tax revenues, as well as on the level and structure of non-tax revenues for selected economies in the region. The chapter includes data up to 2021, the second year of the COVID-19 pandemic, and tracks trends in tax and non-tax revenues across the region since 2010.

Revenue Statistics in Asia and the Pacific 2023

1. Tax revenue trends in Asia and the Pacific

Abstract

This edition of Revenue Statistics in Asia and the Pacific provides comprehensive data on public revenues from 2010 until 2021, the second year of the COVID-19 pandemic. Like other regions of the world, the pandemic has had far-reaching social and economic consequences for Asia and the Pacific, although not all economies were affected in the same way. While tax revenues in the majority of economies in the region recovered to some extent in 2021 from sharp declines experienced in 2020, the pandemic continued to weigh heavily on revenues in a few economies, notably among the Pacific Islands.

This report presents detailed and internationally comparable data on tax revenues in 30 Asian and Pacific economies: Armenia, Australia, Bangladesh, Bhutan, Cambodia, People’s Republic of China (hereafter “China”), the Cook Islands, Fiji, Georgia, Indonesia, Japan, Kazakhstan, Korea, Kyrgyzstan1, Lao People’s Democratic Republic (hereafter Lao PDR), Malaysia, the Maldives, Mongolia, Nauru, New Zealand, Pakistan, Papua New Guinea, the Philippines, Samoa, Singapore, the Solomon Islands, Thailand, Tokelau, Vanuatu and Viet Nam. It also provides information on non-tax revenues for Bhutan, Cambodia, the Cook Islands, Fiji, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Lao PDR, the Maldives, Mongolia, Nauru, Pakistan, Papua New Guinea, the Philippines, Samoa, Singapore, Thailand, Tokelau, Vanuatu and Viet Nam.

Chapter 1 discusses key tax indicators: the tax-to-GDP ratio, the tax structure and the share of tax revenues by level of government. It also analyses non-tax revenues for selected economies. This discussion is supplemented by the comparative tables in Chapter 3 and detailed information for each economy is found in Chapters 4 and 5. A Special Feature in Chapter 2 takes an in-depth look at recurrent property taxation in Asian economies.

Tax-to-GDP ratios in 2021

The tax-to-GDP ratio measures tax revenues (including social security contributions [SSCs] paid to the general government) as a proportion of gross domestic product (GDP). The Asia-Pacific (29) average represents the unweighted average of 29 of the 30 economies included in this publication; it excludes Bangladesh due to the unavailability of data for 2021.

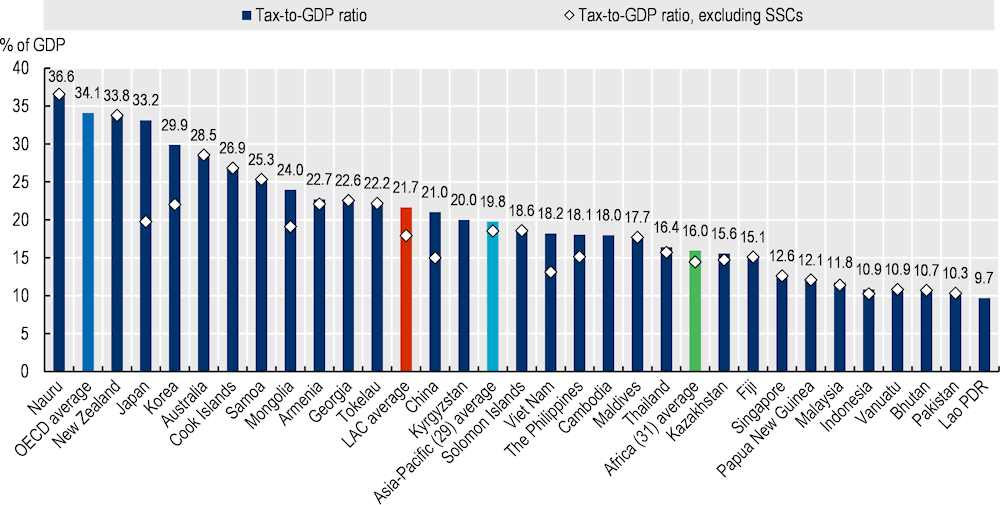

In 2021, tax-to-GDP ratios in Asia and the Pacific ranged from 9.7% in Lao PDR to 36.6% in Nauru (Figure 1.1). Thirteen of the 29 economies had tax-to-GDP ratios above the Asia-Pacific (29) average of 19.8% in 2021, and all economies in the publication had lower ratios than the OECD average of 34.1% with the exception of Nauru (36.6%). Seven of the 19 Asian countries covered in this report (and for which data are available) had a tax-to-GDP ratio above the regional average: Japan (33.2%, 2020 figure), Korea (29.9%), Mongolia (24.0%), Armenia (22.7%), Georgia (22.6%), China (21.0%) and Kyrgyzstan (20.0%). Meanwhile, four of the eight economies among the Pacific Islands included in this report (the Cook Islands, Tokelau, Samoa and Nauru) recorded tax-to-GDP ratios above the regional average and four were below (Papua New Guinea, Vanuatu, Fiji and the Solomon Islands).

Figure 1.1 distinguishes between tax-to-GDP ratios inclusive and exclusive of social security contributions because none of the Pacific Islands covered in this report levy SSCs. Among Asian countries, tax-to-GDP ratios exclusive of SSCs ranged from 10.3% of GDP in Indonesia to 22.1% of GDP in Armenia and Korea in 2021 (Cambodia, Lao PDR and Kyrgyzstan are not included as SSC data are not available). Exclusive of SSCs, seven countries in Asia had tax-to-GDP ratios between 15% and 25% of GDP: China (15.0%), the Philippines (15.2%), Thailand (15.7%), Mongolia (19.1%), Japan (19.8%, 2020 figure) and Armenia and Korea (both at 22.1%). Four countries observed tax-to-GDP ratios exclusive of SSCs below 15%: Indonesia (10.3%), Malaysia (11.4%), Viet Nam (13.1%) and Kazakhstan (14.7%).

Figure 1.1. Tax-to-GDP ratios in Asian and Pacific economies and regional averages, including and excluding social security contributions, 2021

Note: The figures do not include sub-national tax revenue for the Cook Islands, Fiji, Lao PDR, Malaysia, the Maldives, Papua New Guinea, Samoa, the Solomon Islands and Viet Nam as this data are not available.

SSC data for Cambodia, Kyrgyzstan and Lao PDR were not available.

The averages for Africa (31 countries), Asia-Pacific (29 economies), LAC (25 Latin American and Caribbean countries) and the OECD (38 countries) are unweighted.

Australia, Japan, Korea and New Zealand are also part of the OECD (38) group. Data for Australia, Japan, Korea, New Zealand and the OECD average are taken from Revenue Statistics 2022 (OECD, 2022[1]).

Data for 2020 is used for the Africa (31) average, Australia and Japan, as data for 2021 is not available.

Source: Authors’ calculations based on Table 3.1 in Chapter 3.

Changes in tax revenues in 2021 and over time

This section analyses the impact of the continuing COVID-19 pandemic on nominal tax revenues and nominal GDP in the Asia-Pacific region between 2020 and 2021 as well as changes in the tax-to-GDP ratio over this period. The value of the tax-to-GDP ratio depends on two components: the numerator (tax revenues) and the denominator (GDP) (Box 1.1). Changes in tax-to-GDP ratios between 2020 and 2021 reflect changes in both components over this period.

In 2021, most economies in the Asia-Pacific region rebounded from economic contractions caused by the COVID-19 pandemic the previous year (Table 1.1). This recovery was supported by higher commodity prices, a rebound in consumption and investment, and stronger external demand. Global merchandise exports and imports surpassed pre-pandemic levels in value terms, with nominal growth of 24.6% and 23.8% respectively in 2021 (UN.ESCAP, 2021[2]).

However, the recovery was uneven across Asia and the Pacific. Between 2019 and 2021, GDP in Central Asia, East Asia, South Asia and Southeast Asia, grew by 3.7%, 9.8%, 3.6% and 0.2% respectively, while it shrunk by 7.4% in the Pacific. While East Asia recorded the strongest growth over this period thanks to buoyant external demand, the recovery of tourism-dependent economies, many of which are in the Pacific, was hampered by the impact of continued pandemic-containment restrictions on domestic activity and international travel (ADB, 2022[3]). Visitor arrivals in the Pacific Islands declined on average by around 95% in 2021 compared to their 2019 level (SPC, 2023[4]) These macroeconomic factors have impacted domestic resource mobilisation in the region, as will be examined in the following sections.

Table 1.1. GDP growth rates (%) in the Asia Pacific region, 2019-21

|

|

2019-20 |

2020-21 |

2019-21 |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Central Asia |

-2.0 |

5.8 |

3.7 |

|

East Asia |

1.8 |

7.9 |

9.8 |

|

South Asia |

-4.4 |

8.4 |

3.6 |

|

Southeast Asia |

-3.2 |

3.5 |

0.2 |

|

The Pacific |

-6.1 |

-1.4 |

-7.4 |

Source: (ADB, 2023[5])

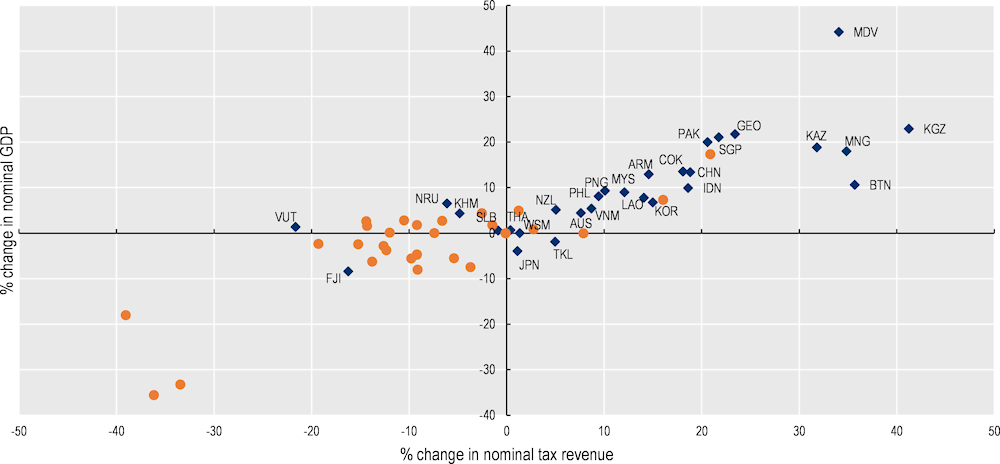

Changes in nominal tax revenues and GDP

After historic falls in nominal tax revenues and GDP in 2020 in almost all economies covered in this report, both indicators increased in 21 of the 27 economies for which data are available in 2021 (Figure 1.2). In 19 of these economies, nominal tax revenues increased by more than nominal GDP, resulting in higher tax-to-GDP ratios. In the Solomon Islands, Cambodia, Nauru and Vanuatu, nominal tax revenues decreased while nominal GDP increased, leading to a decline in the tax-to-GDP ratio. Fiji was the only economy where nominal tax revenues and nominal GDP decreased between 2020 and 2021 (by 16.2% and 8.4%, respectively), which also led to a decrease in the tax-to-GDP ratio in 2021. In the Maldives and Thailand, GDP increased more strongly than nominal tax revenues in 2021, resulting in a drop of 1.3 p.p. and 0.1 p.p. in the tax-to-GDP ratio, respectively.

Figure 1.2. Changes in nominal tax and nominal GDP, 2020-21

Note: Australia, Japan, Korea and New Zealand are part of the OECD (38) group. Data for Australia, Japan, Korea and New Zealand are taken from Revenue Statistics 2022 (OECD, 2022[1]).

Australia and Japan are excluded from the graph as data for 2021 were not available.

Source: Author’s calculation based on (OECD, 2023[6])

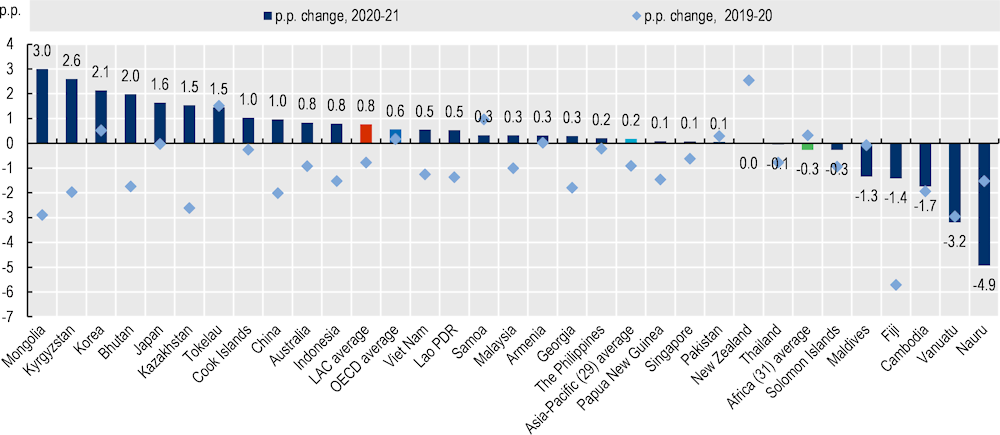

Changes in tax-to-GDP ratios between 2020 and 2021

On average, the tax-to-GDP ratio for the Asia-Pacific region increased by 0.2 p.p. between 2020 and 2021, having shrunk by 0.9 p.p. in 2020. This was lower than the increase in Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC), where the average tax-to-GDP ratio increased by 0.8 p.p. between 2020 and 2021 (OECD et al., 2023[7]) and lower than the increase in the OECD average of 0.6 p.p. (OECD, 2022[1]). Of the three regional averages, only that of the Asia-Pacific region remained below its pre-pandemic level in 2021.

Between 2020 and 2021, more than two-thirds of the economies in this publication for which data are available experienced increases in their tax-to-GDP ratio (Figure 1.3). For eleven economies, the increase in 2021 meant that their tax-to-GDP ratio recovered to a level equal to or higher than prior to the pandemic in 2019, while the rest of the economies had lower tax-to-GDP ratios in 2021 than in 2019. In 2020, tax-to-GDP ratios declined in 21 of these economies from the previous year.

Nine economies reported an increase in their tax-to-GDP ratio equal to or larger than 1 p.p. between 2020 and 2021: China, the Cook Islands (both 1.0 p.p.), Tokelau, Kazakhstan (both 1.5 p.p.), Japan (1.6 p.p., 2019-20 change), Bhutan (2.0 p.p.), Korea (2.1 p.p.), Kyrgyzstan (2.6 p.p.) and Mongolia (3.0 p.p.). By contrast, five economies reported a decrease larger than 1 p.p.: the Maldives (1.3 p.p.), Fiji (1.4 p.p.), Cambodia (1.7 p.p.), Vanuatu (3.2 p.p.) and Nauru (4.9 p.p.). Decreases in Thailand and the Solomon Islands were smaller than 1 p.p. while New Zealand’s tax-to-GDP ratio was unchanged.

Figure 1.3. Annual changes in tax-to-GDP ratios, 2019-21

Note: Australia, Japan, Korea and New Zealand are part of the OECD (38) group. Data for Australia, Japan, Korea and New Zealand are taken from Revenue Statistics 2022 (OECD, 2022[1]).

Data for the change between 2019 and 2020 are used for Australia, Japan and the Africa (31) average.

Source: Author’s calculation based on (OECD, 2023[6])

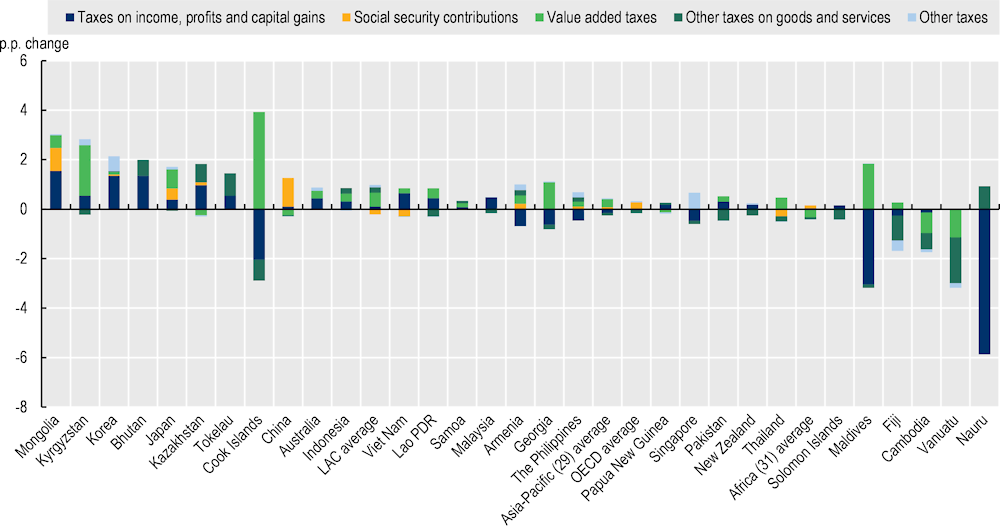

Changes in tax-to-GDP ratios between 2020 and 2021 by tax category

The rise of 0.2 p.p. in the Asia-Pacific (29) average tax-to-GDP ratio between 2020 and 2021 was driven by increases in revenues from value added taxes (0.3 p.p.) and SSCs (0.1 p.p.). These increases were offset by decreases in revenues from taxes on income and from other taxes on goods and services, of 0.2 p.p. and 0.1 p.p., respectively, on average. The 0.9 p.p. decline in the region’s tax-to-GDP ratio in the previous year was driven by declines in revenues from VAT and revenues from other taxes on goods and services, which both decreased by 0.4 p.p.

While the majority of Asian economies covered in this publication reported increases in their tax-to-GDP ratio between 2020 and 2021, the recovery of tax-to-GDP ratios in the nine Pacific economies for which data are available was uneven, with four economies reporting a decline in their tax-to-GDP ratio, four reporting an increase and one remaining unchanged.

The reasons for the increases varied across Asian and Pacific economies:

The increase in Mongolia’s tax-to-GDP ratio (of 3.0 p.p.) was the largest recorded in the region between 2020 and 2021. Revenues from income taxes rose by 1.5 p.p. while revenues from SSCs increased by 0.9 p.p. and revenues from VAT by 0.5 p.p. The end of COVID-19-related tax measures such as an SSC exemption, and a loosening of COVID-19 restrictions as well as increases in commodity prices, inflation and an economic recovery contributed to the increase in tax revenues. The increase in income taxes was primarily due to a one-off collection of tax arrears from Oyu Tolgoi copper and gold mine (World Bank Group, 2022[8]).

In Kyrgyzstan (2.6 p.p.), the increase was mostly driven by increases in revenues from VAT (2.0 p.p.) and income taxes (0.5 p.p.). Improvements in administration and digitalisation measures, such as e-invoicing and e-filing, drove the increases in VAT revenues on imported products (IMF, 2023[9]; State Tax Service, 2022[10]). The increase in revenues from income taxes can be attributed to higher payments by mining companies due to the rise in gold prices and the start of the Djerui gold mining operation (World Bank Group, 2021[11]).

In Korea (2.1 p.p.), the increase was the result of higher revenues from income taxes (1.3 p.p.) because of higher wages, increased employment and an increase in capital gains due to higher property prices (OECD, 2022[1]). Revenues from property taxes increased by 0.6 p.p. between 2020 and 2021.

In Bhutan (2.0 p.p.), the increase was driven by higher revenues from income taxes (1.3 p.p.) and from other taxes on goods and services (0.7 p.p.). Income tax revenues increased due to improved compliance, higher revenues from telecommunication companies as well as from ferrosilicon companies resulting from higher commodity prices. Revenues from other taxes on goods and services increased because of higher revenues from sales taxes on goods, commodities, petroleum and beer, reflecting an increase in social events following the loosening of COVID-19 restrictions (Department of Revenue & Customs, 2022[12]).

In Kazakhstan (1.5 p.p.), higher revenues from CIT (0.9 p.p.) from the mining and manufacturing sectors as a result of higher commodity prices and an increase in revenues from other taxes on goods and services (0.7 p.p.) due to higher custom duties from oil exports were the main drivers of the increase in the tax-to-GDP ratio.

In Tokelau (1.5 p.p.), nominal GDP declined while nominal tax revenues increased. Revenues from excises increased by 0.9 p.p. while revenues from PIT increased by 0.5 p.p. as wage increases pushed workers into higher tax brackets.2

In the Cook Islands (1.0 p.p.), the increase was due to increases in VAT revenues from imports and the return of tourists (The Government of the Cook Islands, 2022[13]).

In China (1.0 p.p.), the increase was driven almost entirely by SSCs (1.2 p.p.), which rebounded from a relatively low level in 2020, in part due to the end of some COVID-related support measures. Other changes included higher revenues from income taxes, which increased by 0.1 p.p., while VAT revenues decreased by 0.2 p.p. between 2020 and 2021.

Meanwhile, the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic was a key factor behind the decreases in tax-to-GDP ratios, especially in economies reliant on tourism:

In Fiji, which maintained restrictions on international travel until December 2021 and was affected by a COVID-19 outbreak in the same year, revenues declined by 1.4 p.p., mostly because of a decline in other taxes on goods and services (1.0 p.p.), driven by decreases in excises and the departure tax (which both declined by 0.4 p.p.). An increase in revenues from VAT (0.3 p.p.) due to changes in VAT rates was offset by a decline in revenue from income taxes (0.3 p.p.) and from stamp duties (0.4 p.p.). A range of stimulus measures, for instance the reduction of the departure tax, contributed to the decline in revenues.3 (Lee, 2023[14]) (ADB, 2022[15])

Lower tourist numbers weighed on tax revenues in Cambodia and Vanuatu, whose tax-to-GDP ratios declined by 1.7 p.p. and 3.2 p.p. respectively in 2021. In Vanuatu, revenues from VAT decreased by 1.1 p.p. and revenues from other taxes on goods and services decreased by 1.8 p.p. as a result of border closures in 2021, which negatively impacted the service sector and domestic consumption (Department of Finance & Treasury, 2022[16]). In Cambodia, revenues from VAT decreased by 0.8 p.p. while revenues from other taxes on goods and services fell by 0.7 p.p. due to lower domestic consumption and lower demand for imported durable goods and construction materials and lower excise revenues (Ly, 2021[17]).

In Nauru, a decline of 5.9 p.p. in income tax revenues was partly offset by an increase in revenues from other taxes on goods and services (0.9 p.p.), resulting in a decrease of 4.9 p.p. in the tax-to-GDP ratio between 2020 and 2021. The decrease in income tax revenue can be attributed to lower activity in the regional processing centre (RPC)4, resulting in lower revenues from the employment services tax and the business tax.5 Revenues from other taxes on goods and services such as import duties increased due to higher consumption. (IMF, 2022[18]) (Republic of Nauru, 2022[19]).

Figure 1.4. Net changes in tax-to-GDP ratios between 2020 and 2021 by main type of tax

Note: Australia, Japan, Korea and New Zealand are part of the OECD (38) group. Data for Australia, Japan, Korea and New Zealand are taken from Revenue Statistics 2022 (OECD, 2022[1]). Data for the change between 2019 and 2020 are used for Australia and Japan.

Source: Author’s calculation based on (OECD, 2023[6])

Box 1.1. The tax-to-GDP ratio methodology

The tax-to-GDP ratios shown in Revenue Statistics in Asia and the Pacific 2023 express aggregate tax revenues as a percentage of GDP. The ratio depends on its denominator (GDP) and its numerator (tax revenues). Both the numerator and the denominator may be subject to historical revision.

Taxes are defined as compulsory, unrequited payments to general government. In the OECD classification, taxes are classified by the base of the tax and include taxes on incomes and profits, compulsory social security contributions (SSCs) paid to the general government, taxes on payroll and workforce, taxes on property, taxes on goods and services and other taxes.

The numerator (tax revenues)

This publication uses tax revenue figures that are submitted by focal points or published annually by national Ministries of Finance, tax administrations or statistical offices. Historical tax revenue data are subject to revision each year, with more important revisions in the more recent years. Past figures may also change from one edition to the next when new data are obtained.

In 15 Asian and Pacific economies, the reporting year coincides with the calendar year. The remaining twelve economies report on a fiscal year basis:

The fiscal year in Australia, Bangladesh, Bhutan, the Cook Islands, Nauru, New Zealand, Pakistan, Samoa and Tokelau runs from July to June. This means that reporting year 2021 corresponds to Q3/2021-Q2/2022.

The fiscal year in Singapore and Japan covers April to March while in Thailand it covers October to September. The reporting year 2021 spans Q2/2021-Q1/2022 and Q4/2020-Q3/2021, respectively.

The denominator (GDP)

The GDP figures used in this publication are sourced from OECD National Accounts data for Australia, Indonesia, Japan, Korea and New Zealand; national sources for Armenia, China, the Cook Islands, Fiji, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Malaysia, Maldives, Mongolia, Philippines, Tokelau and Viet Nam; the Asian Development Bank's Key Indicators Database for the Solomon Islands; World Economic Outlook data published by the IMF for Bangladesh, Bhutan, Lao PDR, Nauru, Pakistan, Papua New Guinea, Singapore, Thailand and Vanuatu; and a combination of national sources and IMF data for Cambodia, Georgia and Samoa.

Using these GDP figures ensures maximum consistency across countries, as well as international comparability. GDP figures are also revised and updated to reflect better data sources and improved estimation procedures, or to move towards new internationally-agreed guidelines for measuring the value of GDP.

Types of taxes levied and data availability

There is a large variation in the types of tax levied by the economies included in the report. The majority of the 30 economies included in the report collect revenues from taxes on income, with two exceptions: Tokelau does not levy CIT and Vanuatu levies neither PIT nor CIT. For Nauru and Pakistan, it is not possible to distinguish between revenues from PIT and CIT, which is why revenues from income taxes are categorised under “1300 Unallocable between 1100 and 1200”. While VAT plays an increasingly important role in many economies, Bhutan, Malaysia, Nauru, the Solomon Islands and Tokelau do not levy VAT. The OECD Interpretative Guide (see Annex A) defines SSCs as compulsory payments that confer entitlement to receive a future social benefit. While most economies in Asia levy social security contributions, none of the Pacific economies do.

Data for Australia and Japan was not available in 2021 when this report was written. For this reason, when 2021 data for these countries are mentioned, they refer to the fiscal year 2020-21 (starting in April 2020 for Japan and starting in July 2020 for Australia) instead of fiscal year 2021-22, and changes between 2020 and 2021 refer to changes between FY2019 and FY2020 for both countries.

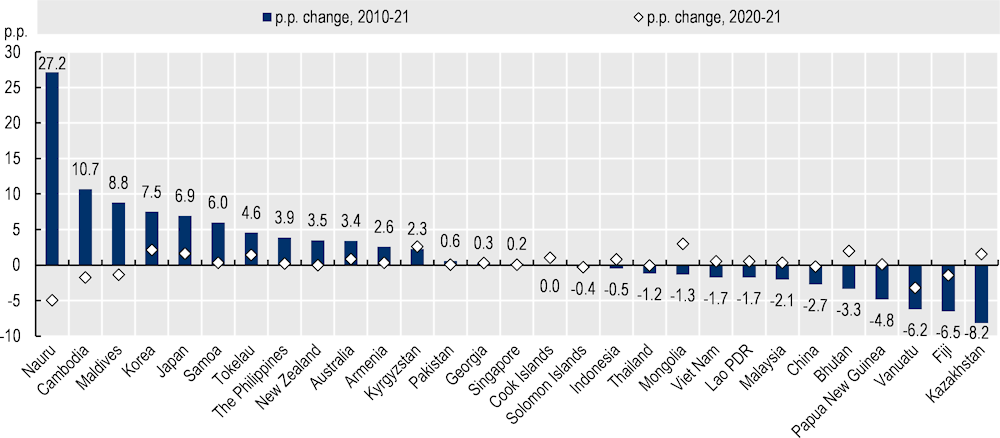

Evolution of tax-to-GDP ratios since 2010

Between 2010 and 2021, tax-to-GDP ratios increased in 15 economies in this publication, declined in 13 and stayed the same in one (Figure 1.5).6 The largest increases were observed in Samoa (6.0 p.p.), Japan (6.9 p.p., 2010-20), Korea (7.5 p.p.), Maldives (8.8 p.p.), Cambodia (10.7 p.p.) and Nauru (27.2 p.p., since 2014). Of the 15 economies whose tax-to-GDP ratios increased since 2010, only Georgia, Pakistan (since 2011) and Singapore reported changes smaller than 2 p.p. Seven of the economies whose tax-to-GDP ratio has decreased since 2010 reported changes larger than 2 p.p. between 2010 and 2021.

The largest decreases between 2010 and 2021 were observed in Malaysia (2.1 p.p.), China (2.7 p.p., excluding SSCs), Bhutan (3.3 p.p.), Papua New Guinea (4.8 p.p.), Vanuatu (6.2 p.p.), Fiji (6.5 p.p.) and Kazakhstan (8.2 p.p.). While the tax-to-GDP ratios of Kazakhstan, Malaysia, Papua New Guinea and Bhutan were affected by falls in commodity prices, decreases in Fiji and Vanuatu were attributable to the COVID-19 pandemic: between 2010 and 2019, Fiji’s tax-to-GDP ratio increased by 0.6 p.p. and Vanuatu’s tax-to-GDP remained at a similar level, at 17.1% in 2010 and 17.0% in 2019 (Figure 1.5).

Figure 1.5. Changes in tax-to-GDP ratios (2010-21 and 2020-21)

Note: Australia, Japan, Korea and New Zealand are part of the OECD (38) group. Data for Australia, Japan, Korea and New Zealand are taken from Revenue Statistics 2022 (OECD, 2022[1]). For Australia and Japan, the graph shows changes between 2010-20 and 2019-20 as data for 2021 were not available for both countries.

The tax-to-GDP ratio for China is shown exclusive of SSCs. Data for Nauru is only available from 2014 and for Pakistan from 2011 onwards.

Source: Author’s calculations based on (OECD, 2023[6])

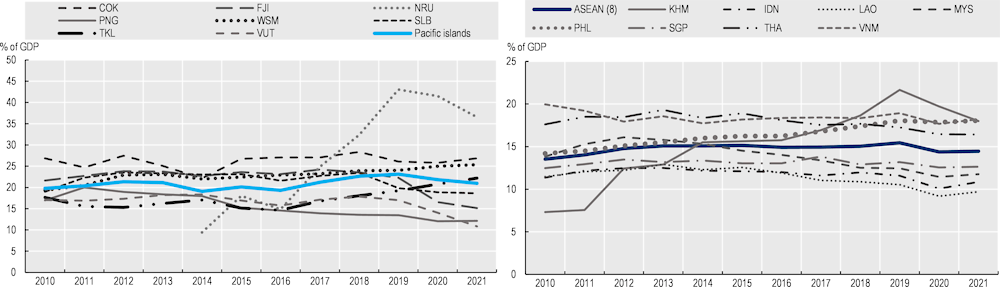

Box 1.2. Tax revenue trends in the ASEAN (8) and in Pacific Island economies since 2010

Among the 30 economies included in this publication, two distinct subgroups can be identified: one subgroup of eight Pacific Island economies and another comprising eight members of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN).

The eight Pacific Island economies included in this publication are the Cook Islands, Fiji, Nauru, Papua New Guinea, Samoa, the Solomon Islands, Tokelau and Vanuatu, which together comprise the Pacific Islands (8) average. Despite their diversity, the Pacific Island economies share common characteristics such as remoteness, small populations, limited economic diversification, and exposure to natural disasters and climate change (ADB, 2016[20]).

The second sub-regional group includes the eight ASEAN member states in this publication. Founded in 1967, ASEAN is a regional organisation that promotes economic, political and social collaboration amongst its ten member states and within the region (ASEAN, 2021[21]). The eight ASEAN members included in this publication are Cambodia, Indonesia, Lao PDR, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand and Viet Nam; they comprise the ASEAN (8) average.1

The Pacific Islands generally had higher tax-to-GDP ratios than the ASEAN (8) countries in 2021 (Figure 1.6). Tax-to-GDP ratios in the former grouping ranged from 10.9% of GDP in Vanuatu to 36.6% in Nauru, with an average of 21.0%. Across the ASEAN (8) economies, tax-to-GDP ratios ranged from 9.7% in Lao PDR to 18.2% in Viet Nam in 2021, with an average of 14.5%.

Tax-to-GDP ratios in both groups have increased since 2010, with a more moderate growth for the ASEAN (8) economies (Figure 1.6). Changes in tax-to-GDP ratios between 2010 and 2021 ranged from a fall of 6.5 p.p. in Fiji to an increase of 27.2 p.p. in Nauru (since 2014) in the Pacific Island economies, while changes in the tax-to-GDP ratio in ASEAN countries ranged from a fall of 1.7 p.p. in Viet Nam to an increase of 10.7 p.p. in Cambodia.

The majority of the ASEAN (8) economies registered an increase in their tax-to-GDP ratios between 2020 and 2021, with the exception of Thailand (which fell by 0.1 p.p.) and Cambodia (down by 1.7 p.p.). Three of the Pacific Islands experienced relatively large decreases in their tax-to-GDP ratios over the same period: Fiji (1.4 p.p.), Vanuatu (3.2 p.p.) and Nauru (4.9 p.p.).

Figure 1.6. Tax-to-GDP ratios in ASEAN and Pacific Island economies, 2010-21

Note: Data for Nauru are only available from 2014 onwards.

Source: Author’s calculation based on (OECD, 2023[6]).

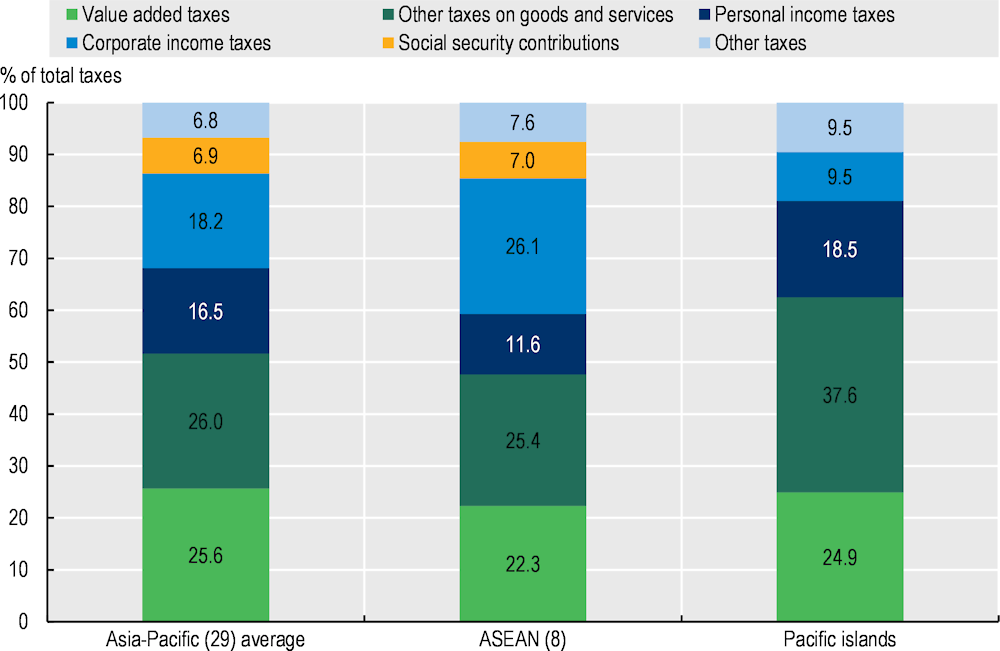

Regional differences are also reflected in average tax structures (Figure 1.7). While revenues from taxes on goods and services play an important role in both regions (47.7% of total taxes in the ASEAN (8) economies and 62.5% in the Pacific Island economies), the composition of the taxes on goods and services differs. Revenues from VAT contributed 22.3% of total taxation in the ASEAN (8) economies on average in 2021, which is lower than the Asia-Pacific (29) average (25.6%) and the Pacific Islands (8) average (24.9%). Revenues from other taxes on goods and services accounted for the largest share of total taxes in both the ASEAN (8) and the Pacific Island economies. However, the share of these taxes was 37.6% in the Pacific Island economies, 12.2 p.p. larger than the average share in the ASEAN (8) countries in 2021 (of 25.4%). While revenues from excises account for around 15% of total taxes in both regions, the share of revenues from customs and import duties is on average much higher across the Pacific Island economies (11.5%) than across the ASEAN (8) countries (3.4%).

Another difference between the sub-groups is the relative importance of revenues from personal income taxes (PIT) and corporate income taxes (CIT). In general, Pacific Island economies rely more on PIT then CIT, while ASEAN economies rely more on CIT than PIT. On average, CIT contributed only 9.5% to total tax revenues in 2021 in Pacific Island economies, whereas it accounted for 26.1% of total tax revenues for the ASEAN (8) average. Meanwhile, PIT accounted for an average of 11.6% of total tax revenues in the ASEAN (8) countries, and 18.5% in Pacific Island economies in 2021.

Figure 1.7. Tax structures in Asia-Pacific, ASEAN (8) and Pacific Island economies in 2021

Note: Asia-Pacific (29) average: Unweighted average of the 29 Asian and Pacific economies included in this publication. ASEAN (8) average: Unweighted average of the 8 ASEAN economies (Cambodia, Indonesia, Lao PDR, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand and Viet Nam) included in this publication. Pacific Islands (8) average: Unweighted average of the 8 Pacific Island economies (the Cook Islands, Fiji, Nauru, Papua New Guinea, Samoa, the Solomon Islands, Tokelau and Vanuatu) included in this publication.

Source: Author’s calculations based on (OECD, 2023[6]), “Revenue Statistics - Asian and Pacific Economies: Comparative tables”, OECD Tax Statistics (database).

1. The ASEAN members not included in this publication are Myanmar and Brunei Darussalam.

Structural factors impacting the tax-to-GDP ratio

Structural factors are a key determinant of tax-to-GDP ratios across economies. These include the importance of agriculture in the economy, openness to trade and the size of the informal economy. For example, in many economies with a large agricultural sector, taxation can be particularly challenging as it is associated with informality, low incomes and low productivity (Mawejje and Sebudde, 2019[22]). In addition, agriculture benefits from numerous tax exemptions. For example, Malaysia grants an Investment Tax Allowance on capital expenditure and income tax to companies producing certain agricultural products or engaged in certain agricultural activities (Malaysian Investment Development Authority, 2019[23]). The common challenges that Small Island Developing States (SIDS) confront, such as remoteness, exposure to natural disasters and low economic diversification, also influence tax-to-GDP ratios and tax structures in these islands. These factors are discussed in more detail in Box 1.3.

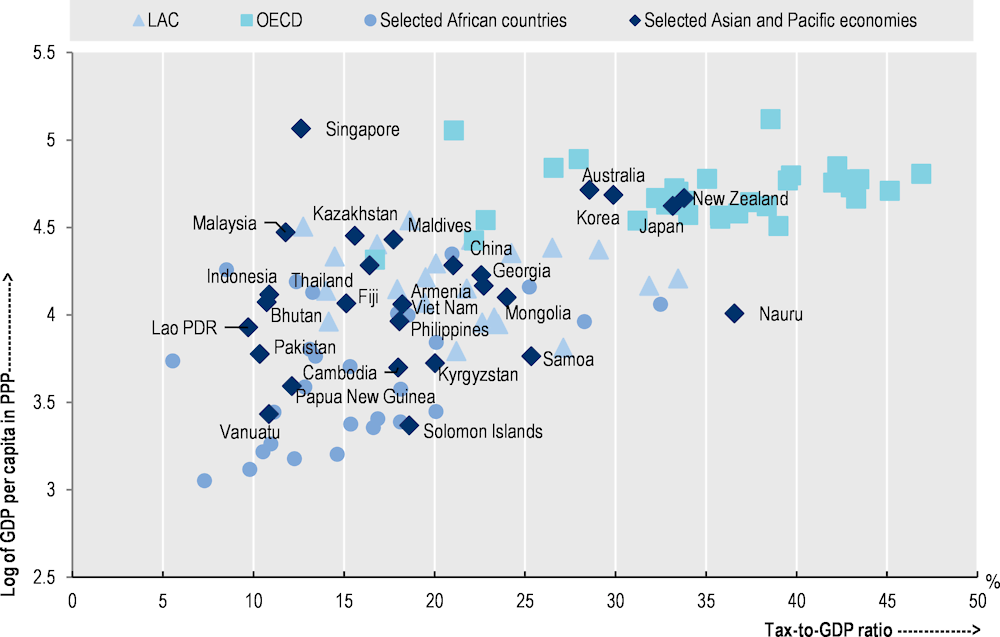

In addition to structural factors, tax policy and tax administration settings also strongly influence the level of tax revenues. These include the size of the tax base, governance and administrative capacity within tax authorities, the level of satisfaction with public service provision and tax morale (i.e., the willingness of people to pay taxes) (OECD, 2019[24]). For example, Aizenman et al. (2019[25]) found that tax-to-GDP ratios in Asia are positively correlated with government effectiveness and institutional quality. Finally, tax-to-GDP ratios tend to be higher in high-income economies, although the relationship is not direct and is less pronounced at lower levels of income due to the influence of other factors (Figure 1.8).

The relationship between GDP per capita and tax levels across Asian and Pacific economies in this publication is less direct than that observed across the LAC region or in OECD countries. Eleven Asian and Pacific economies (Armenia, China, Fiji, Georgia, Kazakhstan, the Maldives, Mongolia, the Philippines, Samoa, Thailand and Viet Nam) have broadly similar GDP per capita and tax-to-GDP ratios as the majority of LAC countries (Figure 1.8). Six economies (Pakistan, Kyrgyzstan, Papua New Guinea, Vanuatu, Samoa and the Solomon Islands) have similar per capita levels of income but their tax-to-GDP ratios differ markedly. In contrast, the four OECD countries included in this publication, Australia, Japan, Korea and New Zealand, have higher per capita income and tax-to-GDP ratios than the remaining economies. Finally, Singapore has the highest GDP per capita of the 29 economies considered here and a relatively low tax-to-GDP ratio.

The high GDP per capita in Singapore results from significant inward flows of foreign direct investment (UNCTAD, 2012[26]), whereas the low level of tax-to-GDP ratio is explained by lower income tax rates (particularly on corporate income) and VAT rates relative to other Asian and Pacific economies (UN.ESCAP, 2014[27]). Nauru, on the other hand, has a similar GDP per capita level to Lao PDR, Viet Nam and the Philippines but reports the highest tax-to-GDP ratio in this publication as a result of high revenues generated in connection with the Refugee Processing Centre (Government of Nauru, 2020[28]).

Figure 1.8. Tax-to-GDP ratios and GDP per capita (in PPP) in Asian and Pacific economies, Latin America and the Caribbean, OECD and African countries (2021)

Note: The y-axis is on a logarithmic scale.

Data for 2020 are used for Australia, Japan and all African countries.

The graph includes data for 31 African, 38 OECD, 26 Latin American and Caribbean and 27 Asian and Pacific economies. The Cook Islands and Tokelau are excluded as GDP per capita data were unavailable for these economies.

The purchasing power parity (PPP) between two countries is the rate at which the currency of one country needs to be converted into that of a second country to ensure that a given amount of the first country’s currency will purchase the same volume of goods and services in the second country as it does in the first. The implied PPP conversion rate is expressed as national currency per current international dollar. An international dollar has the same purchasing power as the US dollar has in the United States. An international dollar is a hypothetical currency that is used as a means of translating and comparing costs from one country to the other using a common reference point, the US dollar [definitions derived from (IMF, 2019[29]) and (WHO, 2015[30])].

Source: GDP per capita from World Economic Outlook, October 2022 (IMF, 2022[31])

Tax structures in Asia and the Pacific and evolution since 2010

The second key indicator analysed in the Revenue Statistics publications is the tax structure, measured as the proportion of revenues from different tax types in total tax revenues. The tax structure (sometimes known as the tax mix) is useful for policy analysis as different taxes have different economic and social effects and distributional impacts. The composition of taxes varies widely across Asia and the Pacific, reflecting different policy choices, economic structures and levels of development, tax administration capabilities and historical factors.

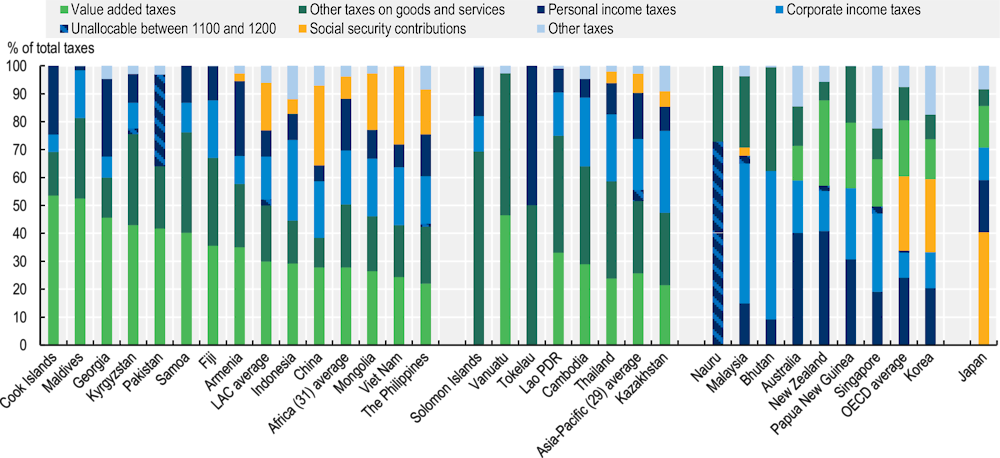

Tax categories as percentage of total tax revenues

Within the Asia-Pacific region, tax structures varied greatly in 2021. In 20 economies, the main source of tax revenues was taxes on goods and services, while eight economies obtained the largest share of tax revenues from income taxes. Japan is the only country where the greatest share of revenues was derived from SSCs. There were also notable differences between the ASEAN countries and the Pacific Islands in the publication, discussed in Box 1.2.

In 2021, income taxes were the largest source of revenues for Australia (2020 figure), Bhutan, Korea, Malaysia, Nauru, New Zealand, Papua New Guinea and Singapore. Among these economies, the share of income tax revenues in total tax revenues ranged from 33.2% in Korea to 72.9% in Nauru. CIT revenues exceeded PIT revenues in three Asian countries (Bhutan, Malaysia and Singapore), while all Pacific economies in this group except Nauru (i.e., Australia, New Zealand, and Papua New Guinea), as well as Korea, generated a higher share of revenue from PIT than from CIT.

SSCs generated a relatively small proportion of revenues for most Asian and Pacific economies, with a few exceptions among the Asian countries. Japan derives the largest share of total tax revenues from SSCs (40.4% in 2020) while these also generated a significant proportion of revenues in the Philippines (16.1%), Mongolia (20.3%), Korea (26.2%), Viet Nam (28.0%) and China (28.6%).

Taxes on goods and services were the main source of tax revenues in Armenia, Cambodia, China, the Cook Islands, Fiji, Georgia, Indonesia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Lao PDR, the Maldives, Mongolia, Pakistan, Philippines, Samoa, the Solomon Islands, Thailand, Tokelau, Vanuatu and Viet Nam in 2021, contributing between 38.4% (China) and 97.4% (Vanuatu) of total tax revenues.

In seven of these economies, taxes on goods and services other than VAT, such as excises and import duties, accounted for a larger share of total tax revenues than VAT. Revenues from other taxes on goods and services in these seven economies ranged from 26.0% of total tax revenues in Kazakhstan to 69.3% in the Solomon Islands. Thirteen economies received a larger share of revenue from VAT, ranging from 22.0% in the Philippines to 53.6% in the Cook Islands.

Figure 1.9. Tax structures as a percentage of total taxation in 2021

Note: The averages for Africa (31 countries), for Asia-Pacific (29 economies), for LAC (25 Latin American and Caribbean countries) and the OECD (38 countries) are unweighted.

Australia, Japan, Korea and New Zealand are part of the OECD (38) group. Data for Australia, Japan, Korea, New Zealand and the OECD average are taken from Revenue Statistics 2022 (OECD, 2022[1]).

2020 data are used for the Africa (31) average, Australia, Japan and the OECD average.

Source: Author’s calculations based on (OECD, 2023[6]), “Revenue Statistics – Asian and Pacific Economies: Comparative tables”, OECD Tax Statistics (database).

In 2021, revenues from other taxes on goods and services played a more prominent role in the Pacific economies than in the Asian countries covered in this publication. Five of the ten Pacific economies generated more revenue from other taxes on goods and services than from VAT (three of which do not apply VAT – Nauru, the Solomon Islands and Tokelau), whereas 13 of the 19 Asian countries received a higher share of revenues from VAT. For the Africa, LAC and OECD averages, revenue from VAT contributed a larger share to total tax revenue than other goods and services while the opposite was true for the Asia-Pacific (29) average.

VAT is nevertheless an increasingly important source of revenues for most economies in this publication, particularly in the Pacific. Excluding Bhutan, Malaysia, Nauru, the Solomon Islands and Tokelau, which do not have value added taxes, VAT revenues in 2021 ranged from 12.4% of total tax revenues in Australia (2020 figure) to 53.6% in the Cook Islands.

In ten of the 17 Asian economies that levy a VAT, it generated more than 25% of total taxes (Mongolia, China, Cambodia, Indonesia, Lao PDR, Armenia, Pakistan, Kyrgyzstan, Georgia and the Maldives). In seven countries, the share of revenues from VAT was below 25%, ranging from 14.4% in Korea to 24.3% in Viet Nam. The share of revenues from VAT in total taxes was generally higher across Pacific economies, with only two economies (Australia at 12.4% of total taxes [2020 figure] and Papua New Guinea at 23.5%) reporting shares below 30%, while the share in the rest of the Pacific economies ranged from 30.6% in New Zealand to 53.6% in the Cook Islands in 2021. On average, the share of VAT in total tax revenues in Asia-Pacific (29) in 2021 (25.6%) was similar to the Africa (31) average (27.8%, 2020 figure), higher than the OECD average of 20.2% (2020 figure) and lower than the LAC average (29.9%).

In 2021, revenues from other goods and services contributed between 6.0% of total tax revenues in Japan (2020 figure) and 69.3% in the Solomon Islands (Figure 1.9). The high share in the Solomon Islands (which does not apply a VAT) was derived from general taxes on goods and services, such as the goods tax, the sales tax and export duties on various products, particularly logging. The share of other taxes on goods and services in total revenues was also comparatively high in Cambodia, Samoa, Bhutan, Lao PDR, Tokelau and Vanuatu, where they exceeded 35% of total tax revenues in 2021 (Bhutan and Tokelau do not apply a VAT).

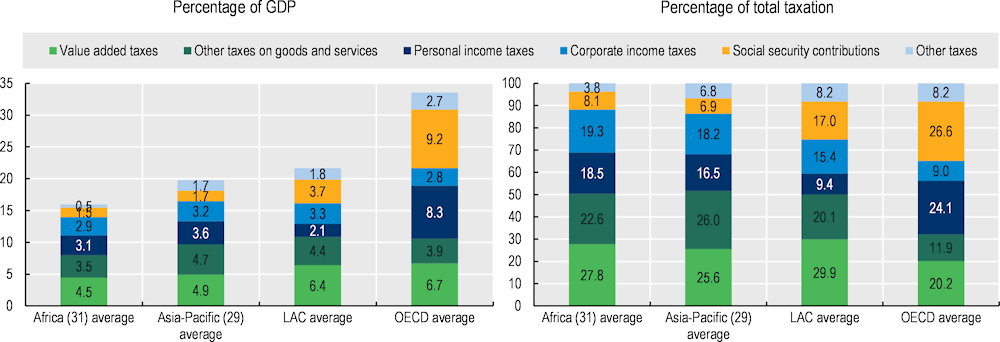

Figure 1.10. Tax structure for the Africa (31), Asia-Pacific (29), LAC and OECD averages, 2021

Note: 2020 data are used for the Africa (31) average and the OECD average.

Source: (OECD, 2023[6]).

Average tax structures across Asia-Pacific, Africa and the LAC region shared some similarities in 2021. Revenues from goods and services accounted for a similar share of total tax revenues in Africa, Asia-Pacific and the LAC region, at 50.4% (2020 figure), 51.6% and 50.0% respectively – much higher than the OECD average of 32.1% (2020 figure). Taxes from other goods and services generated the largest share of total tax revenue (26.0%) in the Asia-Pacific region in 2021 (Figure 1.10), which was higher than the share in Africa (22.6%, 2020 figure) and the LAC average (20.1%), and more than twice the OECD average (11.9%, 2020 figure). Revenues from VAT were equivalent to 4.9% of GDP in Asia-Pacific; at 25.6% of total taxation, these revenues were between the OECD average of 20.2% (2020 figure) and the average share of VAT in Africa (27.8%, 2020 figure) and LAC (29.9%).

On average, income tax revenues in the Asia-Pacific region (37.5%) accounted for a similar share of total taxation as in Africa (39.3%). In the Asia-Pacific region, revenues from PIT accounted for 16.5% of total taxes, similar to the Africa average of 18.5% (2020 figure), above the LAC average (9.4%) and below the OECD average (24.1%, 2020 figure). CIT revenues accounted for a larger share of total tax revenues in the Asia-Pacific region, on average, at 18.2%, which was similar to the Africa (31) average (19.3%, 2020 figure) and above the shares in LAC (15.4%) and the OECD (9.0%, 2020 figure). The Asia-Pacific region had the lowest share of SSCs among the four averages: they contributed 6.9% of total taxes in Asia Pacific, 8.1% in Africa (2020 figure), 17.0% in LAC and 26.6% of total taxes in the OECD (2020 figure).

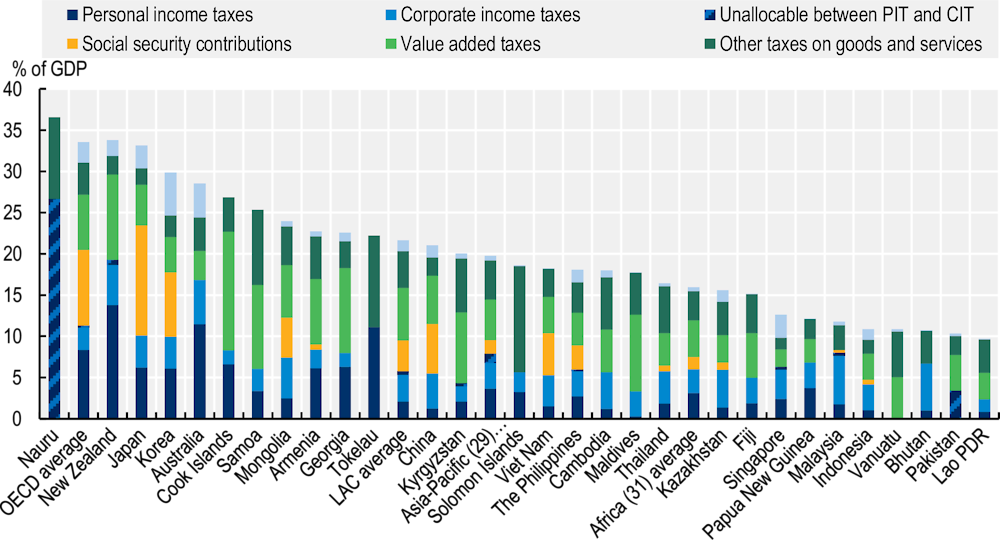

Revenues by tax category in 2021

Tax structures expressed as percentage of GDP also varied across the economies in this publication in 2021. Revenues from income taxes ranged from none in Vanuatu to 26.6% of GDP in Nauru. Three Pacific economies reported revenues from PIT above 10% of GDP (Australia, New Zealand and Tokelau). In the majority of the economies, revenues from CIT were higher than revenues from PIT. While most economies included in the report levy both PIT and CIT, Vanuatu is the only economy which does not levy any form of income tax, while Tokelau does not levy CIT. For Nauru and Pakistan, it is not possible to distinguish between PIT and CIT revenues. Revenues from SSCs play a limited role in Asia and the Pacific, accounting on average for 1.7% of GDP. While revenues from taxes on goods and services played an important role in all economies included in the report, they exceeded 10% of GDP in most Pacific economies but stayed below this level for most of the Asian countries in this report.

Australia, New Zealand and Tokelau recorded the highest levels of PIT revenues as a percentage of GDP in 2021 (Figure 1.11). Revenues from PIT amounted to 13.8% of GDP in New Zealand, 11.5% of GDP in Australia (2020 figure) and 11.1% of GDP in Tokelau. In the other Pacific economies covered in this publication, revenue from PIT was above 3.0% of GDP and closer to the Asia-Pacific (29) average of 3.6%, except in Fiji (1.9%) and Vanuatu (which does not have a PIT). Nauru has the highest level of revenue from income taxes of all the economies included in the publication, at 26.6% of GDP. In Asia, four countries reported revenues from PIT larger than 6%: Korea and Armenia at 6.1%, Japan at 6.2% (2020 figure) and Georgia at 6.3%. In the remaining countries, PIT revenue in 2021 ranged from 0.3% in the Maldives, which introduced PIT in 2020, to 2.7% of GDP in the Philippines.

Figure 1.11. Tax structures in Asian and Pacific economies, 2021

Note: The averages for Africa (31 countries), for Asia-Pacific (29 economies), for LAC (26 Latin American and Caribbean countries) and the OECD (38 countries) are unweighted.

Australia, Japan, Korea and New Zealand are part of the OECD (38) group. Data for Australia, Japan, Korea, New Zealand and the OECD average are taken from Revenue Statistics 2022 (OECD, 2022[1]).

Data from 2020 are used for the Africa (31) average, Australia, Japan and the OECD average.

Source: (OECD, 2023[6]).

Revenues from CIT were equivalent to 3.2% of GDP on average across the Asia-Pacific region in 2021. They were higher than revenues from PIT in 14 of the 25 economies considered in this publication. Revenues from CIT ranged from 1.5% of GDP in the Lao PDR to 5.9% in Malaysia.

SSCs account for a relatively small proportion of tax revenues of Asian and Pacific economies. Fifteen economies in this publication, including all the Pacific economies, do not levy SSCs. In most of the other economies, revenues from SSCs were relatively low in 2021, including Malaysia (0.3% of GDP), Indonesia and Armenia (both 0.6% of GDP), Thailand (0.7% of GDP) and Kazakhstan (0.9% of GDP). These were significantly below the LAC regional average (3.7% of GDP) and the OECD average (9.2% of GDP in 2020). Five Asian economies reported relatively high revenues from SSCs: Mongolia (4.9% of GDP), Viet Nam (5.1% of GDP), China (6.0% of GDP), Korea (7.8% of GDP) and Japan (13.4% of GDP, 2020 figure).7

Revenues from taxes on goods and services amounted to 9.7% of GDP on average across the 29 Asian and Pacific economies. In most Asian economies, revenues from taxes on goods and services amounted to less than 10% of GDP in 2021, with the exceptions of Mongolia (11.1%), Cambodia (11.5%), Armenia (13.1%), Georgia (13.5%), the Maldives (14.4%) and Kyrgyzstan (15.1%). In contrast, the majority of the Pacific economies in this publication generated revenues from taxes on goods and services that exceeded 10% of GDP, ranging from 10.1% of GDP in Fiji to 19.3% in Samoa in 2021. The exceptions in the Pacific were Papua New Guinea (5.3% of GDP) and Australia (7.6% of GDP, 2020 figure).

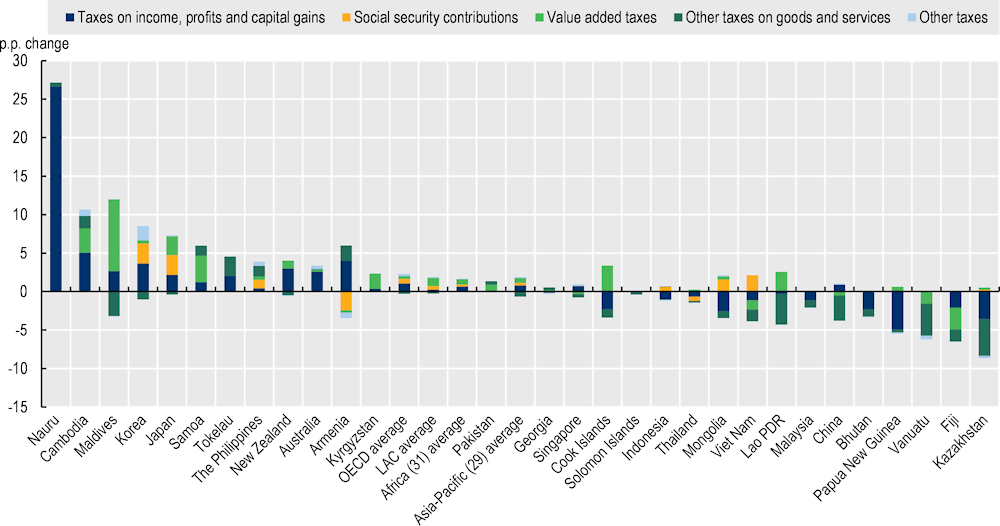

Changes in tax-to-GDP ratios between 2010 and 2021 by tax category

Between 2010 and 2021, declines in CIT revenues and revenues from other taxes on goods and services were the major driver of decreases in tax-to-GDP ratios observed in many economies, whereas a range of tax types accounted for increases observed elsewhere. These changes reflect the diverse range of policy measures and economic developments in Asian and Pacific economies over this period.

Of the thirteen economies where the tax-to-GDP ratios declined between 2010 and 2021, lower CIT revenues contributed to the declines in ten (Figure 1.12). The largest declines in the tax-to-GDP ratios over this period were in Papua New Guinea (4.8 p.p.), Vanuatu (6.2 p.p.), Fiji (6.5 p.p.) and Kazakhstan (8.2 p.p.). The decreases in the Vanuatu and Fiji were mainly due to the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. Papua New Guinea and Kazakhstan were affected by declines in natural resource prices:

Between 2010 and 2021, CIT revenues in Papua New Guinea decreased by 4.7 p.p. due to lower revenues from the mining and petroleum tax, which accounted for less than half as much tax revenue in nominal terms in 2021 as it did in 2010. Other factors such as slower economic growth, low commodity prices between 2014 and 2020 and an earthquake in 2018 also contributed to the decline in the tax-to-GDP ratio (IMF, 2020[32]), (IMF, 2022[33]).

The decline in Kazakhstan’s tax-to-GDP ratio was mainly driven by decreases in CIT (3.5 p.p.) and other taxes on goods and services (4.8 p.p.), which include revenues from customs and import duties and from taxes on mineral production. Kazakhstan was particularly affected by the commodity price shock in 2014, as more than one-third of budget revenues are generated through the oil sector (OECD, 2019[34]).

Fifteen economies recorded increases in their tax-to-GDP ratio between 2010 and 2021. The largest increases were observed in the Maldives, Cambodia and Nauru (since 2014), which all recorded increases larger than 8.0 p.p. Reforms to tax policy and administration were the main driver of the increases in tax-to-GDP in all three economies:

Since 2014, Nauru has introduced an employment and services tax and a business tax, and has improved revenue collection (IMF, 2020[35]).

Cambodia has implemented various administrative and regulatory reforms under the long-term Public Financial Management Reform Programme to improve the government’s finance system (Royal Government of Cambodia, 2019[36]). Reforms aimed at making tax administration more efficient have included the digitalisation of taxpayer services, simplification of procedures, improvements of audits and training for staff, as well as the revision of some tax rates to ease compliance (Royal Government of Cambodia, 2018[37]), (OECD, 2018[38]), (World Bank, 2019[39]).

The Maldives has undertaken major tax reforms since 2011 to increase tax revenues. Key policy changes have included the introduction of a goods and services tax in 2011, a business tax, and a corporate profit tax (ADB, 2017[40]). The tax-to-GDP ratio increased by 2 p.p. between 2010 and 2011, mainly due to the introduction of the VAT. Subsequent rate increases in these three taxes have contributed to higher tax revenues (ADB, 2017[40]). The Maldives also introduced a personal income tax in 2020 (Maldives Inland Revenue Authority, 2020[41]).

Figure 1.12. Net changes in tax-to-GDP ratios between 2010 and 2021, by main tax type

Note: Australia, Japan, Korea and New Zealand are part of the OECD (38) group. Data for Australia, Japan, Korea and New Zealand are taken from Revenue Statistics 2022 (OECD, 2022[1]).

Data for 2020 are used for Australia and Japan.

Data for Nauru are only available from 2014 and Pakistan from 2011 onwards. The tax-to-GDP ratios for China are shown exclusive of SSCs.

Source: Authors’ calculations based on (OECD, 2023[6]) “Revenue Statistics - Asian and Pacific Economies: Comparative tables”, OECD Tax Statistics (database).

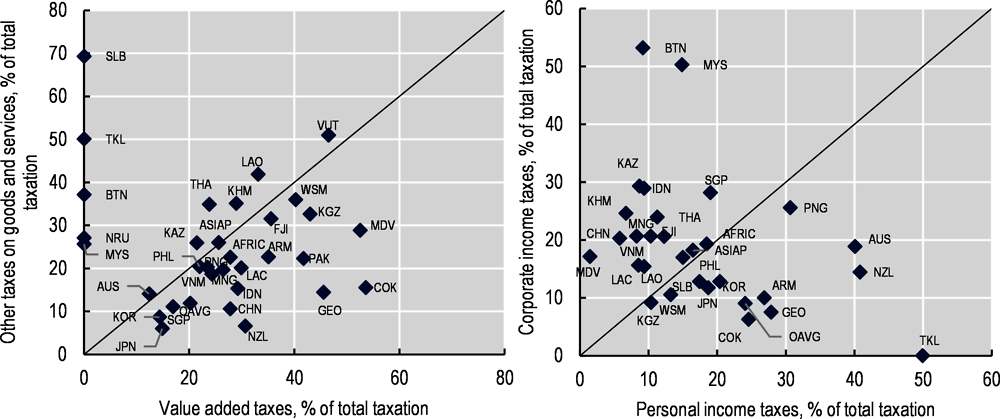

Revenues from taxes on goods and service account for a large share of total tax revenues across the economies in this report, but the source of these revenues varies (Figure 1.13). In 18 economies, the share of VAT revenue was larger than the share of revenue from other taxes on goods and services, while five economies (Bhutan, Malaysia, Nauru, the Solomon Islands and Tokelau) do not levy VAT.

Between 2010 and 2021, the share of revenues from VAT increased most in the Maldives (by 52.5 p.p.), China (27.8 p.p.) and Lao PDR (27.4 p.p.). The Maldives and Lao PDR introduced a VAT within this timeframe (in 2011 and 2010, respectively). While Lao PDR replaced its turnover tax with a VAT (Keomixay, 2010[42]), the Maldives introduced a goods and sales tax, which is a value added tax, for the first time (ADB, 2017[40]). China replaced a business tax with VAT in 2016 (OECD, 2017[43]).

The relative importance of CIT and PIT in income tax revenues also varied between Asian and Pacific economies (Figure 1.13). In most Asian economies included in this publication, the share of revenues from CIT as a percentage of total taxation was higher than the share of revenues from PIT in 2021, except for Armenia, Georgia, Japan, Kyrgyzstan and Korea. In contrast, all Pacific economies with the exception of Fiji reported higher shares of revenues from PIT than CIT (see Box 1.2).

In 2021, revenues from CIT contributed between 6.2% of total tax revenues in the Cook Islands and 53.2% of total tax revenues in Bhutan. In six economies, the share of CIT revenues in total tax revenues exceeded 25% (Bhutan, Indonesia, Kazakhstan, Malaysia, Papua New Guinea and Singapore). PIT revenues as a percentage of total tax revenues ranged from 1.5% in the Maldives, which introduced PIT in 2020, to 49.9% in Tokelau (which does not have a CIT).

Figure 1.13. Revenues from VAT and other taxes on goods and services and revenues from PIT and CIT, 2021

Source: (OECD, 2023[6])., “Revenue Statistics - Asian and Pacific Economies: Comparative tables”, OECD Tax Statistics (database).

The share of CIT revenues was lower in 2021 than in 2010 in fourteen economies, by between 0.3 p.p. of total tax revenues in Lao PDR and 20.2 p.p. in Papua New Guinea. The share of revenues from PIT decreased in seven Asian and Pacific economies between 2010 and 2021, with the size of the decrease ranging from 0.3 p.p. in Samoa to 4.2 p.p. in the Cook Islands. Revenue from PIT increased as a share of total taxation for 19 economies (excluding Pakistan, Nauru and Vanuatu which has no PIT data), with the increases ranging from 0.1 p.p. in Japan (change from 2010-20) to 16.3 p.p. in Armenia.

Box 1.3. Enhancing domestic resource mobilisation in Small Island Developing States through revenue statistics

Small Island Developing States (SIDS) comprise a diverse group of the smallest and most remote economies in the world located across Africa, Asia and the Pacific, and Latin America and the Caribbean. They share a common and unique set of development challenges owing to their small populations and landmasses, spatial dispersion and remoteness from major markets, and exposure to severe climate-related events and natural disasters. With small and undiversified economies, SIDS are highly vulnerable to external shocks, as they rely strongly on the global economy for financial services, tourism, remittances and concessional finance.

Two common challenges faced by SIDS are the achievement of adequate domestic resource mobilisation and debt sustainability. Domestic revenues are often erratic due to narrow economic productive bases that tend to be concentrated in sectors exposed to external fluctuations, such as natural resources or tourism. At the same time, SIDS typically have large current expenditures as the high unit cost of providing services to small and scattered populations increases public sector spending above the average levels of other developing countries (31.7% of GDP in SIDS, compared to 21.3% in other developing countries) (World Bank, 2020[44]). Severe climate events and natural disasters also tend to have heavy fiscal and economic impacts. These factors lead to high levels of public debt for many SIDS [59.5% of GDP on average, compared to 44.6% for other developing countries in 2015 (World Bank, 2020[45])] and reduce the fiscal space to invest in development.

Taxes are an important and relatively stable source of revenues in many SIDS, although economies’ ability to raise domestic revenues varies significantly. The Global Revenue Statistics publications and database (OECD, 2023[46]) show that Pacific Islands had the biggest variation of tax-to-GDP ratios among SIDS, from 12.1% in Papua New Guinea to 36.6% in Nauru in 2021. Among African SIDS, Cabo Verde had a tax-to-GDP ratio of 20.1%, Mauritius of 21.0% and Seychelles of 32.0% in 2020 (OECD, AUC, ATAF, 2022[47]). Finally, for SIDS in Latin America and the Caribbean, ratios ranged from 14.5% in the Dominican Republic to 31.9% in Barbados in 2021 (OECD et al., 2023[7]).

The COVID-19 pandemic has hampered SIDS’ ability to mobilise and improve the stability of domestic revenues. Public revenues in SIDS have been affected by the crisis via a variety of channels, most notably the sharp fall in tourism, the decline in overall economic activity, and fluctuations in commodity and natural resource prices. To recover from the COVID-19 crisis, enhanced management of key sectors, including fisheries, tourism and natural resource extraction, may provide opportunities to enhance domestic revenue mobilisation in SIDS. Policies to reduce “leakages” from these sectors – especially tourism – and to support backward and forward linkages with other domestic sectors (e.g., food and agriculture, consumer goods and construction) could expand the taxable production base.

Improving the efficiency of revenue collection, enlarging the tax base and employing efficient tax policies are also essential to increase the resources required to sustain development. The Global Revenue Statistics project supports 21 SIDS in these efforts by providing accurate, comparable and detailed data on their tax revenues. This information is essential for tax policymaking and administrative reforms, and forms a common evidence base for mutual learning across SIDS on how to scale up domestic resource mobilisation.

Source: Piera Tortora and Talita Yamashiro Fordelone, based on OECD (OECD, 2018[48]), (World Bank, 2020[45]), (World Bank, 2020[44]) and on the Global Revenue Statistics database (OECD, 2023[46]).

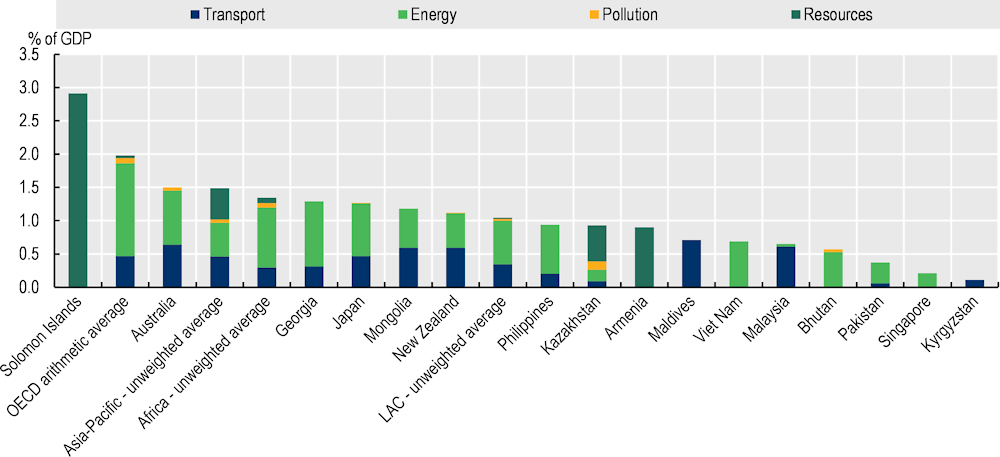

Environmental taxes in Asia and the Pacific

Environmentally related taxes,8 and price-based policy instruments more generally, play an increasingly significant role in many countries to support a transition to sustainable and low-carbon economic growth. By incorporating a price signal into consumer and producer decisions, these taxes give effect to the polluter-pays principle and encourage businesses and households to consider the environmental costs of their behaviour. Although environmentally related tax revenues9 (ERTRs) are not separately identified in the standard OECD tax classification, they can be identified through the detailed list of specific taxes included for most countries within this overarching classification. It is on this basis that they are included in the OECD Policy Instruments for the Environment (PINE) database (OECD, 2023[49]).10

Detailed examination of taxes for the Asian and Pacific economies for which information is available demonstrates that revenues from environmentally related taxes in 2021 ranged from 0.1% of GDP in Kyrgyzstan to 2.9% of GDP in the Solomon Islands.11 ERTRs in the Solomon Islands are particularly high relative to other Asian and Pacific economies and the OECD average, due in large part to higher export duties, particularly on timber. The next highest levels of ERTRs as percentage of GDP in the region in 2021 were observed in Australia (1.5%), Georgia (1.3%), Japan (1.3%), Mongolia (1.2%) and New Zealand (1.1%). On average, ERTRs amounted to 1.5% of GDP in the Asia-Pacific region in 2021.

Figure 1.14. Environmentally related tax revenue in Asian and Pacific economies, by main tax base, 2021

Note: It has not been possible to identify environmentally related tax revenues for Cambodia, China, the Cook Islands, Indonesia, Korea, Lao PDR, Nauru, Papua New Guinea, Samoa, Thailand, Tokelau and Vanuatu due to data availability issues. Bangladesh tax revenue data are not available in 2021. Data for 2020 are used for the Africa (31) average. The average value displayed for an aggregate may not be exactly equal to the value calculated based on data from individual countries due to adjustments made for preventing jumps and breaks in the data series.

Sources: Restricted ERTR database based on PINE database; (OECD, 2023[49]).

Asian and Pacific economies relied on a range of bases for their ERTRs in 2021:

In Maldives, Kyrgyzstan, Malaysia and New Zealand, the majority of ERTRs came from transport taxes (registration or road use of motor vehicles or departure taxes). They represent the totality for Maldives and Kyrgyzstan, 94% of total ERTRs in Malaysia and 53% in New Zealand.

In other Asian and Pacific economies, ERTRs are principally raised via taxes on energy (most commonly from diesel and petrol excises). They represent the totality of ERTRs in Viet Nam and Singapore, 93% in Bhutan, 84% in Pakistan, 79% in the Philippines, 76% in Georgia, 62% in Japan and 54% in Australia.

The remaining economies mainly levied ERTRs from resource taxes. The Solomon Islands and Armenia relied entirely on resource taxes while they contributed 58% of Kazakhstan’s ERTRs in 2021.

The composition of ERTRs is markedly different in Asian and Pacific economies compared to African, LAC and OECD countries. In 2021, revenues from energy taxes, resource taxes and transport taxes generated almost equal shares of total ERTR in the Asia-Pacific region (34%, 32% and 31% respectively) whereas in other regions, energy taxes accounted for the majority of ERTRs (70% in the OECD, 67% in Africa [2020 figures] and 63% in LAC).

In general, the use of taxation to address environmental issues is low in the region compared to the OECD and there is scope to increase use of such instruments. The under-utilisation of environmental taxes in the Asia-Pacific region needs to be understood in the context of the extensive use of fossil fuels subsidies. Reforming energy subsidies is considered by ADB (2016[50]) as ‘one of the most important policy challenges for developing Asian economies’. UN.ESCAP (2016[51]) recommends that governments gradually phase out energy subsidies while implementing measures to compensate vulnerable groups and to ensure international competitiveness in a sustainable way. Reforming energy subsidies while at the same time implementing environmental taxation has the potential to mobilise significant government revenues and help to meet the Sustainable Development Goals.

Taxes by level of government

This section discusses the relative share of tax revenues attributed to different levels of government in 2021: federal or central government, sub-national government (including regional or provincial government, state government and local government) and social security funds. For the majority of Asian and Pacific economies for which data on revenues by level of government is available, tax revenues are collected primarily by federal or central government. Sub-national tax revenues as a share of total tax revenues are low and highly variable across the region (Table 1.2).

In 2021, the share of sub-national government tax revenues ranged from 0.6% of total revenues in Bhutan to 34.6% in China, averaging 12.0% across the region (excluding Australia, Japan and Malaysia)12. In comparison, central government tax revenues accounted for only about 60% of total tax revenues in OECD countries in 2020. Despite being at a relatively low level, the share of sub-national government revenues has increased for most regional economies over time. The largest increase has been observed in Indonesia, where the sub-national share rose from 3.2% in 2000 to 10.8% in 2021, driven in part by tax policy reforms such as the shift of property taxation to the local level in 2014. Japan and Kazakhstan were the only countries whose sub-national government shares have decreased since 2000, though their shares remained among the highest. There is room for improving sub-national government tax revenues in the region. Chapter 2, the Special Feature of this publication, looks at how recurrent property taxation can be strengthened among developing economies in Asia.

As a share of GDP, sub-national tax revenues were higher in Japan (7.6%, 2020 figure), China (7.3%), Australia (5.5%) and Korea (5.4%) in 2021, while they were relatively low in Bhutan (0.1%), Pakistan (0.9%) and the Philippines (1.0%). The amount of tax revenues collected by sub-national governments is affected by multiple factors. For example, the type of taxes levied by local governments vary between countries. Local governments in the Philippines, for instance, have a narrow range of taxes under their jurisdiction, relying mainly on property taxes and taxes on income and profits. Sub-national governments in Japan and Korea, however, raise revenue from taxes on income and profits, property taxes, taxes on goods and services, payroll (Korea only) and other taxes. The share of sub-national government tax revenue also depends on the range of services that local governments are expected to provide. For example, in Japan, where sub-national tax revenues were often the highest, prefectures and municipalities have a wide range of responsibilities such as economic development, education, urban planning, public health and other social spending (OECD/UCLG, 2019[52]).

The share of revenues attributed to social security funds was also low in Asia and the Pacific. Australia, New Zealand and Singapore do not collect SSCs and the proportion of total tax revenues from social security funds is zero, while it was under 6% of total tax revenues in Indonesia, Kazakhstan, Malaysia and Thailand in 2021. Revenues from social security funds were above average in five countries: at 40.4% in Japan (2020 figures), 28.6% in China, 26.2% in Korea, 20.3% in Mongolia and 16.1% in the Philippines in 2021. In the long run, the share of tax revenues attributed to social security funds has increased the most in Korea (by 9.5 p.p.) since 2000 and in Mongolia since 2010 (by 7.2 p.p.).

Table 1.2. Attribution of tax revenues to sub-sectors of general government, 2000-21

|

|

Federal or central government |

Sub-national government |

Social security funds |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

2000 |

2010 |

2020 |

2021 |

2000 |

2010 |

2020 |

2021 |

2000 |

2010 |

2020 |

2021 |

|

|

Australia |

81.8 |

80.2 |

80.9 |

.. |

18.2 |

19.8 |

19.1 |

.. |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

.. |

|

Bhutan |

99.7 |

99.9 |

99.2 |

99.4 |

0.3 |

0.1 |

0.8 |

0.6 |

.. |

.. |

.. |

.. |

|

Cambodia |

.. |

.. |

90.7 |

91.0 |

.. |

.. |

9.3 |

9.0 |

.. |

.. |

.. |

.. |

|

China |

.. |

.. |

39.1 |

36.8 |

.. |

.. |

36.7 |

34.6 |

.. |

.. |

24.2 |

28.6 |

|

Indonesia |

96.8 |

92.8 |

82.6 |

83.9 |

3.2 |

7.2 |

11.5 |

10.8 |

.. |

.. |

5.9 |

5.3 |

|

Japan |

38.7 |

33.0 |

36.6 |

.. |

26.1 |

25.9 |

23.0 |

.. |

35.2 |

41.1 |

40.4 |

.. |

|

Kazakhstan |

50.3 |

81.3 |

65.0 |

66.8 |

49.7 |

16.2 |

29.7 |

27.7 |

.. |

2.5 |

5.3 |

5.5 |

|

Korea |

68.2 |

60.0 |

53.0 |

55.6 |

15.1 |

16.6 |

19.0 |

18.2 |

16.7 |

23.3 |

28.0 |

26.2 |

|

Malaysia |

98.0 |

98.2 |

96.9 |

97.1 |

.. |

.. |

.. |

.. |

2.0 |

1.8 |

3.1 |

2.9 |

|

Mongolia |

.. |

75.5 |

65.9 |

64.6 |

.. |

11.4 |

15.4 |

15.2 |

.. |

13.1 |

18.7 |

20.3 |

|

New Zealand |

94.3 |

92.8 |

93.9 |

93.7 |

5.7 |

7.2 |

6.1 |

6.3 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

|

Pakistan |

.. |

.. |

91.1 |

91.2 |

.. |

.. |

8.9 |

8.8 |

.. |

.. |

.. |

.. |

|

Singapore |

100.0 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

|

Thailand |

88.9 |

86.3 |

86.6 |

88.2 |

7.5 |

6.6 |

7.6 |

7.7 |

3.7 |

7.1 |

5.8 |

4.1 |

|

The Philippines |

81.5 |

82.0 |

78.3 |

78.5 |

5.3 |

5.4 |

5.9 |

5.5 |

13.1 |

12.6 |

15.7 |

16.1 |

Note: Australia, Japan, Korea and New Zealand are part of the OECD (38) group. Data for Australia, Japan, Korea and New Zealand are taken from (OECD, 2022[1]). Sub-national figures for Australia include data of state and local government.

Source: (OECD, 2023[6])., “Revenue Statistics - Asian and Pacific Economies: Comparative tables”, OECD Tax Statistics (database).

Non-tax revenues in selected economies

This publication includes information on non-tax revenues for nineteen economies for which data are available. Non-tax revenues are defined as all revenues received by general government that do not meet the OECD definition of tax revenues, as set out in the Interpretative Guide (Annex A). They are further divided into five categories according to the definitions set out in Annex B: grants; property income; sales of goods and services; fines, penalties and forfeits; and miscellaneous and unidentified revenues.

Non-tax revenues as a percentage of GDP

Non-tax revenues were equivalent to a significant share of GDP in 2021 for six of the 19 economies (Samoa, Vanuatu, Bhutan, the Cook Islands, Nauru and Tokelau). By contrast, non-tax revenues were below 8.5% of GDP in the remaining economies in 2021. Compared with the previous year, non-tax revenues had decreased slightly on average in 2021, with 11 out of 19 economies experiencing declines.

In 2021, non-tax revenues amounted to 10.8% of GDP in Samoa, 16.0% in Vanuatu, 19.3% in Bhutan and 20.8% in the Cook Islands, and they amounted to 89.0% in Nauru and 201.3% in Tokelau. The high level of non-tax revenues in Tokelau, measured as a share of GDP, is due to the fact that non-tax revenues are derived primarily from payments by foreign vessels for access to fishing waters under the Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) of Tokelau. In the 2008 System of National Accounts, these revenues are recorded as part of GNI but they do not add to GDP. Similarly, fishing activities represent a significant source of revenue for the Nauru government and accounted for more than 30% of the total non-tax revenue in 2021, collected mainly from access fees paid by foreign fishing vessels.

Between 2020 and 2021, non-tax revenues declined in 11 economies as a percentage of GDP while they increased in eight. The declines exceeded 1 p.p. in four economies: Viet Nam (1.1 p.p.), Vanuatu (7.6 p.p.), Cook Islands (14.3 p.p.), and Tokelau (17.4 p.p.). The decline in non-tax revenues in Tokelau was almost entirely attributable to lower revenues from the EEZ, which were heavily affected by the COVID-19 crisis. In contrast, Nauru reported an increase of 13.6 p.p. in non-tax revenues due to a significant increase (of 19.8 p.p.) in grants in 2021 which included debt forgiveness for Yen Bonds (IMF, 2022[18]).

Non-tax revenues have been increasing since 2010 (or earliest available year) as a share of GDP in the majority of the economies but declining for the Philippines (since 2011), Pakistan (since 2011), Papua New Guinea, Mongolia, Bhutan, Cambodia, Maldives and Lao PDR. The largest increases occurred in Tokelau (46.7 p.p.), Nauru (35.6 p.p. since 2014), Vanuatu (7.4 p.p.) and the Cook Islands (7.2 p.p.).

The upward trend for Tokelau and Nauru has been driven by higher revenues from property income, which is mostly sourced from fishing activities. Tokelau receives support from New Zealand to strengthen the management of its EEZ to maximise revenue collection from its international fisheries (New Zealand Foreign Affairs & Trade, 2018[53]). Fisheries income also increased for Tokelau and Nauru after they became partners to the Parties to the Nauru Agreement (PNA), which administers the fishing vessel-day scheme (VDS). The VDS is the system to sustainably manage the world’s largest tuna fishery in the Western and Central Pacific Ocean, and has increased revenue to the PNA by over 700% in the past seven years (Parties to the Nauru Agreement, 2016[54]).

The increase in non-tax revenues for Vanuatu is mainly due to development project grants from Australia, the World Bank, New Zealand and China, and the government’s Honorary Citizenship Programme (Department of Finance and Treasury of Vanuatu, 2018[55]). For the Cook Islands, grants have constituted an increasing share of non-tax revenues. Official Development Assistance from New Zealand to support education, health and tourism initiatives in the Cook Islands accounts for the largest source of grant revenues (Ministry of Finance and Economic Management, 2020[56]). Non-tax revenues have been more volatile than tax revenues in many economies. In Bhutan, Lao PDR and Samoa, the volatility of non-tax revenues was mostly due to grants. In Pakistan, it was due to revenues from property income.

Table 1.3. Non-tax revenues in selected Asia Pacific economies, 2010-21

Percentage of GDP

|

|

2010 |

2011 |

2012 |

2013 |

2014 |

2015 |

2016 |

2017 |

2018 |

2019 |

2020 |

2021 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Bhutan |

22.1 |

21.5 |

16.6 |

20.6 |

14.8 |

17.7 |

15.0 |

16.4 |

13.1 |

19.5 |

19.4 |

19.3 |

|

Cambodia |

6.4 |

4.6 |

4.4 |

5.7 |

4.4 |

4.0 |

5.1 |

4.7 |

5.1 |

5.1 |

4.2 |

3.6 |

|

Cook Islands |

13.5 |

8.2 |

8.4 |

14.3 |

16.2 |

13.9 |

16.4 |

13.7 |

12.3 |

14.9 |

35.1 |

20.8 |

|

Fiji |

2.9 |

3.6 |

3.0 |

2.9 |

3.0 |

2.9 |

3.2 |

3.5 |

3.6 |

3.5 |

4.1 |

7.9 |

|

Kazakhstan |

1.0 |

1.4 |

1.9 |

1.0 |

1.5 |

1.4 |

1.2 |

1.1 |

1.7 |

1.5 |

1.2 |

1.5 |

|

Kyrgyzstan |

8.3 |

8.7 |

7.6 |

8.4 |

9.4 |

10.7 |

7.9 |

8.5 |

6.3 |

7.6 |

7.8 |

8.3 |

|

Lao PDR |

9.5 |

6.7 |

10.2 |

7.3 |

9.6 |

7.7 |

4.5 |

5.3 |

5.4 |

5.1 |

3.8 |

5.4 |

|

Maldives |

10.2 |

9.0 |

6.3 |

5.1 |

7.0 |

6.7 |

7.2 |

6.8 |

6.8 |

6.4 |

5.7 |

6.7 |

|

Mongolia |

6.5 |

7.4 |

6.9 |

7.2 |

7.8 |

6.4 |

5.1 |

4.3 |

4.6 |

4.3 |

3.7 |

4.0 |

|

Nauru |

.. |

.. |

.. |

.. |

53.3 |

65.7 |

82.7 |

79.1 |

103.8 |

87.3 |

75.4 |

89.0 |

|

Pakistan |

.. |

2.4 |

3.0 |

4.2 |

3.0 |

2.5 |

2.8 |

2.0 |

1.0 |

3.3 |

2.1 |

1.7 |

|

Papua New Guinea |

4.7 |

3.3 |

3.1 |

2.4 |

3.1 |

3.2 |

3.2 |

3.2 |

4.5 |

3.3 |

2.7 |

2.9 |

|

Samoa |

8.9 |

6.0 |

4.8 |

6.8 |

4.6 |

4.4 |

4.5 |

5.3 |

5.6 |

10.9 |

11.5 |

10.8 |

|

Singapore |

3.5 |

3.5 |

3.4 |

3.5 |

3.9 |

4.4 |

4.4 |

5.3 |

4.3 |

7.1 |

4.6 |

3.9 |

|

Thailand |

3.3 |

2.7 |

2.9 |

2.9 |

3.1 |

3.6 |

3.7 |

3.6 |

3.8 |

3.7 |

4.0 |

3.6 |

|

The Philippines |

.. |

1.9 |

1.9 |

1.8 |

1.8 |

2.0 |

1.8 |

1.7 |

1.8 |

2.0 |

2.3 |

1.7 |

|

Tokelau |

154.6 |

196.4 |

192.6 |

246.6 |

173.4 |

230.4 |

236.5 |

210.0 |

236.4 |

220.1 |

218.7 |

201.3 |

|

Vanuatu |

8.6 |

6.1 |

5.5 |

4.5 |

6.2 |

15.4 |

9.8 |

14.2 |

19.8 |

24.3 |

23.6 |

16.0 |

|

Viet Nam |

4.5 |

4.0 |

3.9 |

4.1 |

4.1 |

5.3 |

5.7 |

6.7 |

6.8 |

6.5 |

6.5 |

5.4 |

Note: Tokelau receives significant revenues from foreign vessels for access to Tokelau fishing waters. In the 2008 SNA, these revenues are recorded as part of GNI, but they do not add to GDP.

Source: (OECD, 2023[6]) “Revenue Statistics in Asian and Pacific Economies: Comparative tables”, OECD Tax Statistics (database).

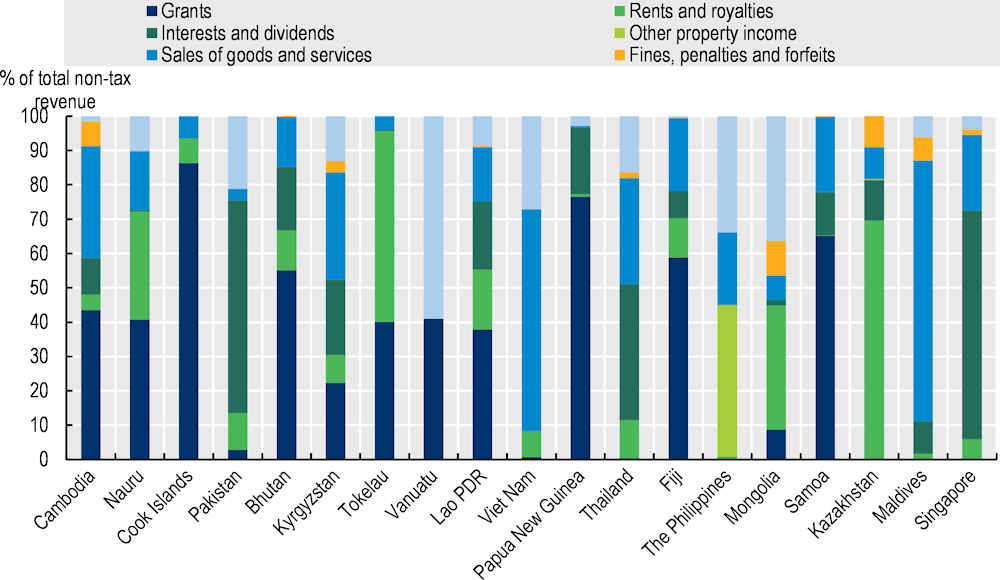

Structure of non-tax revenues

Non-tax revenues are divided into different categories: grants; property income; sales of goods and services; fines, penalties and forfeits; and miscellaneous and unidentified revenues. In 2021, the share of each of these categories in total non-tax revenues varied across the 19 economies (Figure 1.15). Notable trends include:

Grants were an important source of revenues for more than half of the economies in 2021, exceeding 30% of total non-tax revenues in ten economies: Lao PDR (37.8%), Tokelau (40.1%), Nauru (40.7%), Vanuatu (41.1%), Cambodia (43.5%), Bhutan (55.1%), Fiji (58.9%), Samoa (65.2%), Papua New Guinea (76.5%) and the Cook Islands (86.4%). Revenues from grants increased on average by 1.4 p.p. from 7.6% of GDP in 2020 to 9.0% in 2021.

Property income accounted for over 30% of total non-tax revenue in more than half of the economies in 2021, including Bhutan (30.1%), Kyrgyzstan (30.1%), Nauru (31.9%), Lao PDR (37.4%), Mongolia (37.7%), the Philippines (45.0%), Thailand (50.7%), Tokelau (55.9%), Singapore (72.5%), Pakistan (72.6%) and Kazakhstan (81.7%). There were eight economies in which property income accounted for less: Vanuatu, which does not generate revenues from property income, the Cook Islands (7.1%), Viet Nam (7.6%), Maldives (11.1%), Samoa (12.7%), Cambodia (15.2%), Fiji (19.3%) and Papua New Guinea (20.2%).

Property income in Tokelau and Nauru was derived predominantly from fisheries (i.e. fishing rents, fishing days, support vessels, etc.), which represented more than 90% of total property income in both economies. Rents and royalties accounted for 69.6% of total non-tax revenue in Kazakhstan in 2021, mainly from oil revenues. Interest and dividends represented the majority of non-tax revenues for Pakistan (62.0%) and Singapore (66.6%). Other property income for the Philippines, mainly Bureau of the Treasury income, made up 44.2% of non-tax revenues.

Sales of goods and services accounted for more than half of non-tax revenues for Viet Nam (64.6%, composed of fees and charges, land rents and revenues from land user right assignment) and Maldives (76.0%, mainly from leasing, fees and charges).

Figure 1.15. Structure of non-tax revenues, 2021

Source: (OECD, 2023[6]) “Revenue Statistics - Asian and Pacific Economies: Comparative tables”, OECD Tax Statistics (database).

References

[5] ADB (2023), Asian Development Outlook 2023, Asian Development Bank, Manila, Philippines, https://doi.org/10.22617/FLS230112-3.

[15] ADB (2022), Asia Regional Integration Center Tracking Asian Integration: Fiji Islands Country/Economy Profile, Asian Development Outlook 2022, https://aric.adb.org/fiji-islands#:~:text=Persistent%20COVID%2D19%20variants%20led,steep%2015.2%25%20contraction%20in%202020 (accessed on 16 June 2023).

[3] ADB (2022), Asian Development Outlook 2022: Mobilizing Taxes for Development, Asian Development Bank, Manila, Philippines, https://doi.org/10.22617/FLS220141-3.

[40] ADB (2017), “Fast-Track Tax Reform Lessons from Maldives”, https://doi.org/10.22617/TIM178673-2.