Building on the analysis presented in the following chapters of the SIGI 2023 Global Report, the present chapter provides an overview of the main results of the fifth edition of the OECD Development Centre’s Social Institutions and Gender Index (SIGI) launched in March 2023. In the context of the Sustainable Development Goals, it highlights how gender equality remains a distant objective despite notable progress. The chapter also presents the main findings of the two thematic chapters of the report, underlining the key role that discriminatory social institutions play in restricting women’s and adolescents’ sexual and reproductive health and rights across the world and exploring the gendered dimensions of climate change. The chapter concludes by stressing the need for bold action in favour of gender equality, not only from governments and policy makers but from all stakeholders including bilateral and multilateral development partners, the private sector, philanthropic organisations and civil society.

SIGI 2023 Global Report

1. Overview

Abstract

In 2015, members of the United Nations reached a fundamental agreement over 17 major goals – the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) – that should be achieved by 2030 and that would serve as the blueprint for peace and prosperity, leaving no one behind. In line with the former Millennium Development Goals,1 eradicating discrimination against women and girls is enshrined as a stand-alone objective (SDG 5), while gender equality is embedded in nearly all 17 goals. In total, around 45% of the indicators of the SDG framework (102 out of 247) are gender-relevant (Cohen and Shinwell, 2020[1]).

Yet, with only seven years to go, the world is not on track to achieve the SDGs and the 2030 Agenda. Evidence shows that progress in SDG 5 as well as in all other gender-related indicators is too slow (Equal Measures 2030, 2022[2]). Worse, the socio-economic consequences of recent crises have exacerbated existing gender inequalities and, in some countries, aggravated discrimination against women and girls (United Nations, 2022[3]). International and regional crises have increased the risk of backlash against gender equality by diverting resources towards issues allegedly more pressing and by undermining the perceived status of gender inequalities as a systemic and urgent problem to address. In the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, disruptions in programmes to prevent child marriage, coupled with households’ rising economic insecurity, have resulted in 10 million additional girl child marriages that would have otherwise been averted (UNICEF, 2021[4]). During humanitarian emergencies, which can result from disasters induced by climate change or conflicts such as the war of aggression against Ukraine, women and girls face an increased risk of gender-based violence and violation of their sexual and reproductive health and rights (see Chapter 3). If prevention, adaptation and mitigation strategies for climate change mainly remain gender-blind, gendered impacts will likely worsen, aggravating women’s vulnerabilities (see Chapter 4).

Gender equality and parity2 are not only social and moral obligations, they are fundamental levers for strong, green and inclusive economic development (OECD, 2023[5]). Conversely, excluding women or erecting barriers against their rights and agency induces significant economic losses. The channels through which these occur are multiple, complex and often intertwined with one another. Some forms of discrimination faced by women yield an opportunity cost because of the untapped potential they represent. This means that the value generated by economies would be greater in the absence of discrimination, for instance through an increase in human capital or a better allocation of female workers (OECD, 2019[6]; Ferrant and Kolev, 2016[7]). That is typically the case of social norms that restrict women’s access to the labour market, education or productive assets. Other types of discrimination have direct social and economic costs for societies. For instance, because of violence against them, women may be unable to work, lose wages, stop participating in regular activities, and have a decreased ability to care for themselves and their family members (OECD, 2020[8]). All these impacts are often compounded when girls and women are exposed to intersecting forms of discrimination which go beyond gender – e.g. age, ethnicity, place of residence or religion, among others.

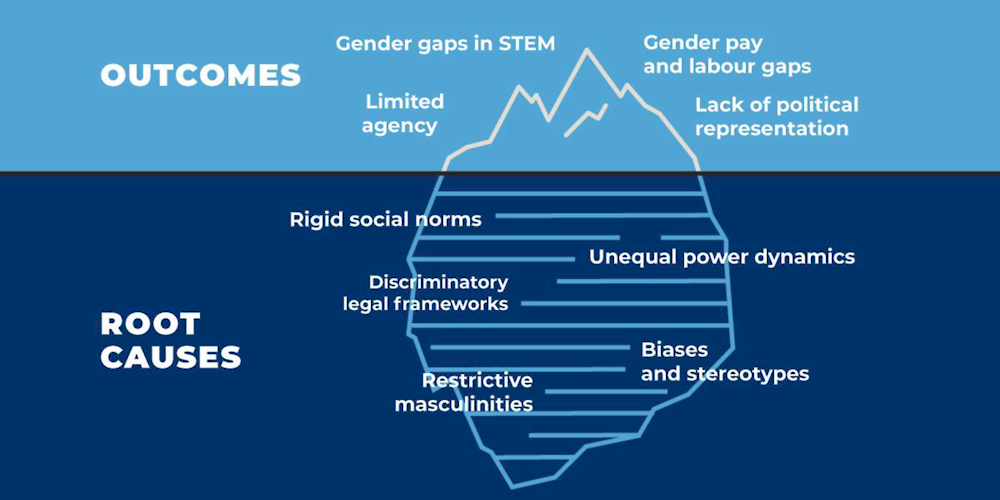

Discrimination in social institutions – the established set of formal and/or informal laws, norms and practices that govern behaviour in society – is at the heart of inequalities and inequities that women face. They fundamentally dictate what women and men are allowed to do, what they are expected to do and what they do. The inequalities observed and experienced by women and girls are just the tip of the iceberg: discriminatory norms and social institutions rest below the surface, reinforcing the status quo. Since 2009, this “invisible part of the iceberg” (Figure 1.1) has been the focus of the OECD Development Centre’s work and has been measured through the Social Institutions and Gender Index (SIGI). It constitutes the root causes of gender gaps observed at the outcome level such as gender-based differences in education, income and wages, access to health services, and so forth (Box 1.1). Focusing on social institutions and strengthening efforts to transform discriminatory social norms are therefore paramount to achieving gender equality, as it often constitutes the crucial bottleneck that prevents change from happening.

Figure 1.1. Discriminatory social institutions are the root causes of gender inequality outcomes

Box 1.1. What is the Social Institutions and Gender Index?

The SIGI measures discrimination in social institutions faced by women and girls throughout their lives

The SIGI is a unique cross-country composite index measuring the level of gender-based discrimination in social institutions. The fifth edition covers 179 countries compared to 180 countries in 2019.3 The SIGI looks at the gaps that legislation, attitudes and practices create between women and men in terms of rights, justice and empowerment opportunities at all stages of their lives.

The SIGI builds on a framework of 4 dimensions, 16 indicators and 25 underlying variables. It covers the major socio-economic areas that affect women and girls throughout their lifetime, from discrimination in the family to restrictions on their physical integrity, their economic empowerment, and their rights and agency in the public and political spheres (see Annex B).

The SIGI measures the root causes of gender gaps observed at the outcome level

Worldwide and regionally, most gender equality indices – e.g. the Gender Development Index and the Gender Inequality Index – seek to measure deprivations and inequalities between men and women at the outcome level. Their focus is on the upper and visible part of the iceberg, and they tend to include measures related to boys’ and girls’ enrolment in education, differences in income and wages, inequalities in access to health services, and so forth.

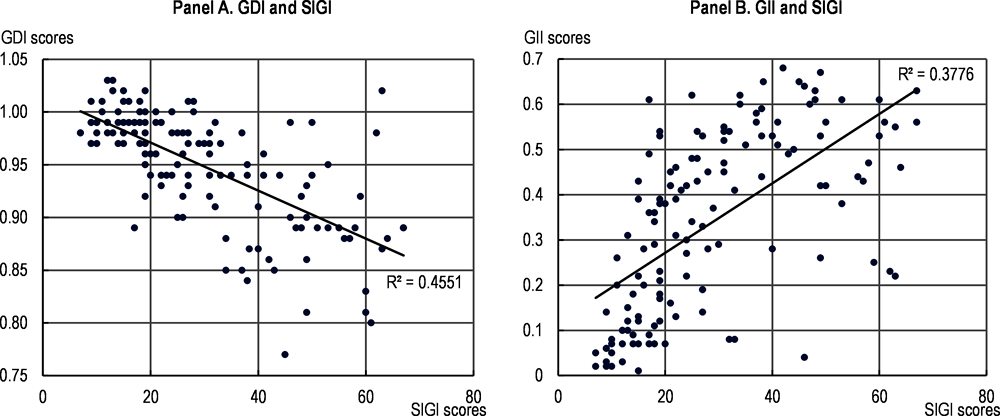

The SIGI, on the other hand, studies the submerged part of the iceberg. The connection between the SIGI and other gender equality indices is that discriminatory social institutions are the root cause of the gender gap observed at the outcome level. They play a fundamental and underlying role by erecting invisible barriers that have lasting consequences on women’s and girls’ lives. More specifically, levels of discrimination measured at the outcome levels are stronger in countries where social institutions are more discriminatory (Figure 1.2).

Figure 1.2. Discriminatory social institutions captured by the SIGI are at the heart of differences between women and men

Note: SIGI scores range from 0 to 100, with 0 indicating no discrimination and 100 indicating absolute discrimination. In Panel A, the Gender Development Index (GDI) measures gender inequalities in achievement in three basic dimensions of human development: health, education and command over economic resources. A GDI of 1 indicate gender parity; scores between 0 and 1 indicate inequality in favour of men; and scores above 1 indicate inequality in favour of women. Data cover 137 countries for which both GDI and SIGI scores are available. In Panel B, the Gender Inequality Index (GII) measures gender-based disadvantages in three dimensions: reproductive health, empowerment and the labour market. It shows the loss in potential human development due to inequality between women’s and men’s achievements in these dimensions. GII scores range from 0 to 1, with 0 indicating that women and men fare equally and 1 indicating that one gender fares as poorly as possible in all measured dimensions. Data cover 134 countries for which both GII and SIGI scores are available.

Source: (OECD, 2023[9]), “Social Institutions and Gender Index (Edition 2023)”, OECD International Development Statistics (database), https://doi.org/10.1787/33beb96e-en; (UNDP, 2021[10]), Gender Development Index, https://hdr.undp.org/data-center/composite-indices; and (UNDP, 2021[11]), Gender Inequality Index, https://hdr.undp.org/data-center/composite-indices.

The fifth edition of the SIGI shows that change is underway but must accelerate

The fifth edition of the SIGI sheds light on the structural and multiple barriers that affect women’s and girls’ lives in developing and developed countries. Between the fourth edition of the SIGI in 2019 and the fifth in 2023, the number of countries in which levels of discrimination in social institutions are low or very low4 has increased by 10, to reach 85 countries out of the 140 that obtained a SIGI score in 2023 (see Annex A). Progress has occurred across all regions of the world, and developing countries are bridging the gap with developed countries. In 2023, 45% of the countries which exhibit very low levels of discrimination in social institutions are non-OECD countries (25 out of 55).

Progress and challenges are not homogeneous. Whereas many countries have enacted legal reforms protecting women’s rights and granting them equal opportunities, change in social norms paints a mixed picture of improvements and setbacks. For instance, the share of people thinking that it is always or sometimes acceptable for a man to beat his wife decreased by 12 percentage points between 2014 and 2021. In general, while discriminatory views towards women in positions of power in politics or in enterprises are decreasing, discriminatory attitudes related to traditional roles of men and women have worsened. For instance, between 2014 and 2021, the share of individuals thinking that men should have more right to a job than women when jobs are scarce increased by 4 percentage points, while the share of the population thinking that it is almost certain to cause problems if a woman earns more money than her husband went up by 6 percentage points (Inglehart et al., 2022[12]).5

Some progress has been achieved globally in reducing gender gaps and eliminating harmful practices. Estimates from the United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF) suggest that girl child marriage dropped from one in four women married before the age of 18 in 2010, to less than one in five in 2022 (UNICEF, 2023[13]; UNICEF, 2022[14]; UNICEF, 2018[15]). Whereas women dedicated 3.3 times more hours to unpaid care and domestic work than men in 2014, the ratio has decreased to 2.6 in 2023. The share of women who have experienced intimate-partner violence during the last 12 months has dropped from 19% in 2014 to 10% in 2023. Finally, the share of women in national parliaments has increased from 22% in 2014 to 24% in 2019 and nearly 27% in 2023 (OECD Development Centre/OECD, 2023[16]; OECD Development Centre/OECD, 2019[17]; OECD Development Centre/OECD, 2014[18]).

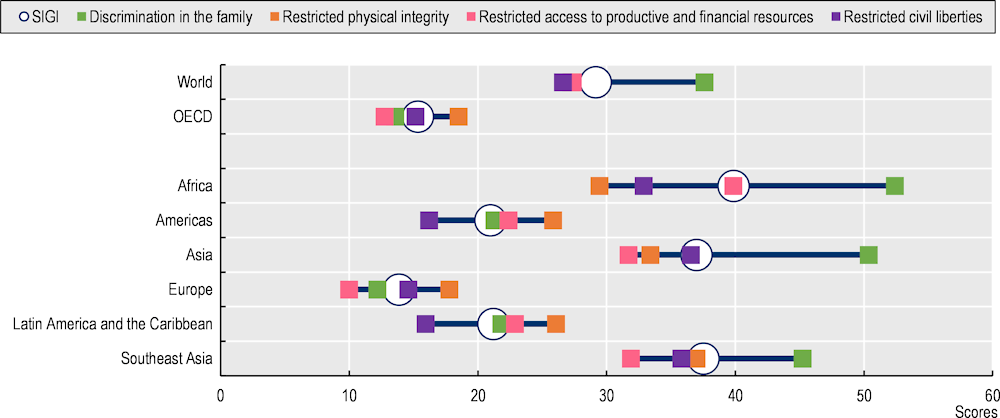

Figure 1.3. Levels of discrimination vary widely across regions, and discrimination is the highest in the family dimension

Note: Scores range from 0 to 100, with 0 indicating no discrimination and 100 indicating absolute discrimination.

Source: (OECD, 2023[9]), “Social Institutions and Gender Index (Edition 2023)”, OECD International Development Statistics (database), https://doi.org/10.1787/33beb96e-en.

Results from the fifth edition of the SIGI reveal ample variation across and within regions. In the Americas and Europe, levels of discrimination are assessed as low and very low, respectively, with SIGI scores of 21 and 14 (Figure 1.3). Conversely, in Africa and Asia, SIGI scores reach 40 and 37 respectively, indicating that, in these regions, levels of discrimination remain high. Wide variations also exist within regions. In Africa, for instance, there is a substantial number of countries in all categories of the SIGI classification, but only four African countries are in the very low category: Côte d’Ivoire, Mozambique, Rwanda and Zimbabwe. Likewise, in Asia, levels of discrimination vary from very low to very high, with countries classified in all categories. In countries that do not fare well, these wide variations may reflect the lack of political will to address the root causes of discrimination, weak governance or conflict and/or the difficulties to implement laws, policies and programmes. For countries that fare better, they highlight their strong commitments to eradicate gender discrimination, including through legal reforms and implementation of laws, programmes and policies aimed at challenging discriminatory social norms.

Globally, discrimination remains the highest within the family sphere

Worldwide, discrimination in the family remains the most challenging dimension in the SIGI framework. In Africa and Asia, levels of discrimination are found to be very high in this dimension of the SIGI, with respective scores of 52 and 50 (Figure 1.3). High levels of discrimination that women and girls face in the private sphere often constitute the primary barrier that prevents their active participation in the public and economic spheres. Moreover, because the transmission of prevailing social norms starts from an early age (Göckeritz, Schmidt and Tomasello, 2014[19]) and are formed within the household, high levels of discrimination in the family affect to what extent the next generation’s attitudes and behaviours will be gender equitable. The persistence of unequal power relations between women and men within the household and, in many countries, the existence of discriminatory civil and personal status laws prevent gender equality in the family sphere. Their effects span over women’s entire lives, impacting their rights to enter into marriage, their status within the household, their ability to seek and obtain a divorce, and their opportunities to engage in paid work, become entrepreneurs or inherit from their parents or spouse on equal grounds with men.

At the global level, women spend 2.6 times more time than men on unpaid care and domestic work. On average, women dedicate 4.7 hours per day to unpaid care and domestic tasks, compared to 1.8 hours for men (OECD Development Centre/OECD, 2023[16]). These systemic differences stem from social norms and traditional views that assign strict gender roles and responsibilities within the household and societies. By confining women to their care and reproductive roles, these norms have lasting consequences on women’s labour inclusion (see Chapter 2). Not only do they constrain women’s participation in the labour market, but they also influence women’s labour status, pushing them into low-wage sectors, the informal economy or part-time arrangements, while keeping them out of leadership and management positions (OECD, 2023[20]).

Discriminatory social norms that confine women and men to stereotypical roles affect women’s ability to take decisions at the household level. Within the logic of norms of restrictive masculinities, men are expected to be financially dominant, to control household assets and to have the final say in household spending and decisions. This includes control over relationships and other activities of household members, as well as investment in health and education for the whole family (OECD, 2021[21]).

Women’s lack of agency is particularly acute in the context of inheritance, aggravating their vulnerabilities to economic deprivations. Historically, individuals have obtained access to assets, particularly land, through purchase, inheritance or state intervention (Kabeer, 2009[22]). In that perspective, any legal or social limitation placed on women’s and girls’ ability to inherit has negative direct and indirect implications for women’s economic empowerment – especially in countries where a large share of the population works in agriculture. Yet, legal restrictions that hamper women’s inheritance rights remain widespread in certain regions. Worldwide, 36 countries6 out of 178, which account for 17% of women globally and are all located in Africa and Asia, do not grant daughters and sons the same rights to inherit. Likewise, 37 countries7 comprising 18% of women do not grant equal inheritance rights to widows and widowers (OECD Development Centre/OECD, 2023[23]).

Finally, despite better legal protections, girl child marriage remains far from being eradicated. Between 2019 and 2023, 21 countries8 have enacted legal reforms aimed at combatting child marriage by ensuring that the minimum legal age of marriage would be 18 years for both men and women and/or by eliminating legal provisions that allow for exceptions to the minimum legal age. These reforms have been instrumental in reducing girl child marriage rates and preventing girls from being married off against their own will (McGavock, 2021[24]; Maswikwa et al., 2015[25]). Yet, the mounting economic pressure caused by multiple, simultaneous shocks with strong interdependencies – COVID‑19, climate change, the global food crisis, etc. – together with persisting informal laws encouraging the marriage of young girls, puts millions of girls at risk of early and forced marriage and may even reverse some of the progress made towards eradicating this harmful practice (UNICEF, 2023[26]).

Violence against women and girls remains a global pandemic

Violence against women refers to a wide range of harmful acts that are rooted in unequal power relations between men and women and that result in – or are likely to result in – physical, sexual, or mental harm or suffering to women (United Nations, 1993[27]). Violence against women can take place anywhere and can take many forms, but in most situations, it is perpetrated by current or former male intimate partners. The impact of violence against women on women’s lives is devastating, including health problems, limited access to education, substantial losses of income, and socio-psychological consequences on children who grow up in violent homes. Violence against women also bears enormous direct and indirect social and economic costs for societies.

Violence against women remains a global issue which affects millions of girls and is likely underestimated. In 2023, nearly one in three girls and women (28%) aged 15 to 49 years has experienced intimate-partner violence at least once in her lifetime; and one in ten has experienced it over the last year (OECD Development Centre/OECD, 2023[16]). Challenges associated with reporting violence against women – the difficulty in recognising what violence is, fear of retaliation and a lack of resources to leave the home – together with the socio-economic consequences of crises such as the COVID-19 pandemic or climate-related events, mean that its prevalence is likely underreported and that the real figures may be well above the ones recorded by official surveys (OECD, 2020[28]).

Although its causes are complex and multi-faceted, violence against women is fundamentally underpinned by harmful social norms “normalising” men’s use of violence. Attitudes justifying intimate-partner violence are strongly associated with more women experiencing it during the past year and are often deeply ingrained in social norms that are perpetuated from one generation to the next. Worldwide, in 2023, 30% of girls and women aged 15 to 49 years think that it is acceptable for a husband to beat his wife under certain circumstances, for instance, if she burns the food or goes out without telling him (OECD Development Centre/OECD, 2023[16]). These attitudes are rooted in norms of restrictive masculinities dictating that a “real” man should protect the household and exert his control over women through domestic violence, while women are expected to accept this violence (OECD, 2021[21]). The widespread belief that domestic violence is a private matter tends to establish that no one – particularly public or judicial authorities – should intervene in the violence that takes place between spouses (Nnyombi et al., 2022[29]), further complicating attempts at eradicating it.

Addressing violence against women requires first and foremost strong and comprehensive legal frameworks. Such frameworks imply that girls and women are protected from all forms of violence including domestic violence and intimate-partner violence, rape and marital rape, honour crimes, and sexual harassment – without any exceptions or legal loopholes. A comprehensive approach also includes legally codified provisions for the investigation, prosecution and punishment of these crimes – if sought by the victim/survivor – as well as protection and support services for victims/survivors (OECD, 2019[6]). Worldwide, according to the SIGI methodology, only 12 countries9 out of 178 have such comprehensive laws that address all types and forms of violence against women. In contrast, 46 countries continue to fail to criminalise domestic violence; 70 countries do not have a definition of rape based on the lack of consent;10 and 22 countries do not legally define and prohibit sexual harassment, while 48 countries do not criminalise it (OECD Development Centre/OECD, 2023[23]).

Discriminatory laws and restrictive norms of masculinities hamper women's economic empowerment globally

Since 2019, progress in women’s position in the labour market has stagnated, and gender inequalities continue to persist. Worldwide, women’s labour force participation rate stands at 47%, compared to 73% for men, which translates into a gender gap of 25 percentage points (International Labour Organization, 2023[30]). The gender gap remains a major concern across all regions, ranging from 11 percentage points in Europe to 30 percentage points in Asia (International Labour Organization, 2023[30]).

Men’s and women’s unequal standing in the labour force takes root in discriminatory social norms. These traditional norms establish men as the main breadwinner, which gives them priority over women in the workplace. Worldwide, in 2023, 45% of the population believes that when jobs are scarce, men should have more right to a job than women (OECD Development Centre/OECD, 2023[16]). Symmetrically, discriminatory social norms confine women to motherhood and caregiving roles within the household, hampering their ability to work. Globally, in 2023, 52% of the population thinks that when women work, the children suffer. Nevertheless, in most instances – particularly in contexts of poverty or limited resources – women are still expected to work and to contribute the household’s income, which translates into a double burden of both paid and unpaid work. As a result, women are often compelled to seek part-time and home-based jobs that offer greater flexibility to manage both paid and unpaid work but often come with more precarious working conditions (International Labour Organization, 2018[31]; Mohapatra, 2012[32]).

Discriminatory social norms also lead to a more segregated labour market – both horizontally and vertically.11 Stereotypes of the social definition of jobs and whether they are deemed appropriate for men and women lead to important horizontal segregation. For instance, worldwide, men account for 92% of total employment in the construction sector whereas women account for 71% of workers employed in health and social care activities (International Labour Organization, 2021[33]). Norms of restrictive masculinities that perpetuate the notion that men are inherently better leaders than women also perpetuate substantial vertical segregation in the labour market. Women are largely excluded from senior decision-making positions and power roles. In 2023, only 15% of firms worldwide are headed by a woman, women account for only 25% of managers and 45% of the global population thinks that men make better business executives than women (OECD Development Centre/OECD, 2023[16]). This dual segregation of the labour market contributes to a deepening of the wage and revenue gap between men and women, with women earning approximately 20% less than men in 2019 (International Labour Organization, 2019[34]).

Women and girls’ agency in the public sphere is improving, but slowly

Since 2000, women’s political representation has improved, but at the current pace, it is projected to take 40 more years to achieve parity in parliaments (see Chapter 2). In 2023, the proportion of members of parliament who are women reached 26.6%, compared to 24.1% in 2019,12 representing an increase of 2.5 percentage points (Inter-Parliamentary Union, 2023[35]). Women’s underrepresentation in politics exists at both ends of the political spectrum – whether among heads of state or government or within local governments. In 2023, women account for only 11% of heads of state and 10% of heads of government (Inter-Parliamentary Union and UN Women, 2023[36]). Likewise, in 2021, at the global level, only 36% of elected members in deliberative bodies of local government were women (Berevoescu and Ballington, 2021[37]).

Laws – particularly quotas – are fundamental to improving women’s representation. An increasing number of countries are enacting laws and implementing policies which establish gender quotas, with the aim of promoting women’s political representation. Worldwide, in 2023, more than half of countries (93 out of 178) have established constitutional and/or legislated gender quotas at the national level (OECD Development Centre/OECD, 2023[23]). At the global level, data from the fifth edition of the SIGI show that women’s representation in parliaments is significantly greater in countries where quotas exist than in countries where they do not. In particular, gender quotas at the national level have had a positive and statistically significant effect on women’s representation in parliaments in the Americas and Asia. Many countries have also established other measures than quotas such as disclosure requirements, parity laws, the obligation to alternate sexes on party lists and/or financial incentives for political parties, whereas, as of 2023, 76 countries have a national action plan supporting the legislation in place and promoting equality between women and men in political and public life (OECD Development Centre/OECD, 2023[23]).

The establishment of quotas and other temporary measures, together with policy frameworks and strategies promoting women’s representation in politics, is crucial in a global context where social norms and stereotypes of women’s and men’s ability to be political leaders continue to limit women’s agency and opportunities to be elected in parliaments. Worldwide, nearly half of the population (48%) believes that men make better political leaders than women. The ideal of men’s dominance and power which lies behind these attitudes is deeply embedded within restrictive masculinities (OECD, 2021[21]). In this context, gender political quotas are a powerful instrument to overcome these systemic barriers (OECD, 2023[20]; OECD, 2022[38]; OECD, 2016[39]). Yet, to be effective, gender quotas may require not only normative and cultural change, but also sanctions that are enforced when quotas are not respected. Among the 93 countries that have national-level quotas, only half (47 countries) have enacted legal provisions or mechanisms that enable legal or financial sanctions for parties or candidates who fail to comply with the law (OECD Development Centre/OECD, 2023[23]).

Safeguarding adolescents’ and women’s sexual and reproductive health and rights is fundamental to achieving gender equality

Multiple and simultaneous shocks characterised by strong interdependencies – COVID-19 pandemic, climate change, the global food crisis, etc. – are exacerbating women’s vulnerabilities, depleting scarce resources to advance gender equality and putting societies at risk of experiencing a backlash against gender equality. While the impact of crises on women spans all aspects of their lives, it can have lasting consequences on specific areas that are crucial to their empowerment and agency – such as sexual and reproductive health and rights (SRHR) which have recently been jeopardised on several fronts. For instance, the COVID-19 pandemic caused disruptions in family planning services leading to 1.4 million unintended pregnancies in 2020 (UNFPA, 2020[40]). Moreover, climate-related disasters can strain the capacity of health systems, thus limiting access to essential sexual and reproductive health services (Women Deliver, 2021[41]).

Despite SRHR being widely recognised as a human right, a global health imperative, and fundamental to promoting sustainable and inclusive development, millions of people are at least partially deprived of their sexual and reproductive rights. Crises and conflicts are likely to exacerbate this deprivation and reinforce inequalities in access to and realisation of SRHR. Gender is a key determinant of such inequalities, but its intersection with personal characteristics including sexual orientation, race, socio-economic status, class, disability or place of residence ultimately determines individuals’ but also specific populations’ ability to realise their rights and thus achieve optimal sexual and reproductive health outcomes.

Discriminatory social institutions are at the heart of gender inequalities in SRHR. Traditional gender roles and norms, unequal power hierarchies, social stigma and harmful practices disproportionately undermine adolescents’ and women’s agency, sexual, reproductive and bodily autonomy. Resulting SRHR inequalities tend to be amplified in developing countries where resource constraints affect access to information, service provision and quality of care (Guttmacher Institute and Lancet, 2018[42]). Addressing underlying legal, social and structural barriers is thus fundamental to secure access to SRHR for all women and girls as a key component of wider efforts to promote gender equality, reduce inequalities in access to education and employment and, ultimately, accelerate inclusive development.

Laws can support or restrict reproductive and sexual rights

Third-party or parental consent laws can restrict individuals’ access to sexual and reproductive health services and treatment. For instance, in more than 75% of countries with data available,13 adolescents under the age of 18 cannot get tested for the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) without parental consent, and in 44 out of 90 countries14, parental consent is needed to access contraceptives, including condoms (UNAIDS, 2021[43]). In addition, laws dictating that a woman must obey her husband can limit women’s ability to make relevant family planning decisions, including on whether to use contraception or attend prenatal healthcare appointments.

Weak legal frameworks on gender-based violence leave girls and women at particular risk of having their right to bodily integrity violated. Such shortcomings can stem from the absence of laws or loopholes within existing laws. For instance, when laws on sexual harassment do not explicitly apply to the school environment, students’ sexual and reproductive rights, and consequently their health, can be violated. Moreover, weak law enforcement and the persistence of informal (customary or religious) laws can negatively affect a person’s SRHR. This is the case, for example, with female genital mutilation or cutting, which continues to persist even in countries that specifically prohibit it (see Chapters 2 and 3).

The Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women calls on countries to legalise abortion at least in cases of rape, incest, threats to the life or health of the pregnant woman, and severe foetal impairment (CEDAW, 2022[44]). Yet, access to safe and legal abortion is uneven across the world. Globally, around 140 million women of reproductive age do not have access to abortion under any circumstances, even when their lives are in danger; and more than 60% of women of reproductive age (representing about 1.1 billion women) cannot have a legal abortion in the case of rape, statutory rape and/or incest. This comes at a high cost. Evidence shows that the share of unsafe abortions is significantly higher in countries with restrictive laws (Bearak et al., 2020[45]). Moreover, unsafe abortions are a leading cause of preventable maternal deaths and result in millions of girls and women being hospitalised every year (UNFPA, 2022[46]).

Restrictive gender norms result in low prioritisation of girls’ and women’s sexual and reproductive health and rights

Patriarchal norms restrain girls’ and women’s rights to safe, quality and affordable sexual and reproductive health services (Crear-Perry et al., 2021[47]). Unequal power structures have created inequalities in people’s ability to choose, voice and act on contraception and family planning preferences and can undermine women’s ability to seek essential sexual and reproductive health services and/or reach facilities when needed (Moreau et al., 2020[48]). In contexts where men take decisions for the couple, where women’s mobility is conditioned on the presence of a man and/or where women are economically dependent on men, women’s sexual and reproductive autonomy is curbed. Such norms are anchored in the population’s beliefs which determine the attitudes and behaviours of the next generation.

Evidence shows that adolescents are likely to reproduce dominant social norms that will underpin their sexual and reproductive health behaviour, decision making, and ability to exercise their rights and health outcomes now and in the future (Liang et al., 2019[49]; Pulerwitz et al., 2019[50]). Trying to comply with the social expectations and existing norms of what it means to be a man or woman and how one should act accordingly, adolescents may reinforce ideals of male strength and control and of female vulnerability and need for protection. Norms of masculinities, such as taking sexual risks, having multiple partners or avoiding healthcare can affect boys’ SRHR with consequences on their partners’ health and rights (Buller and Schulte, 2018[51]).

Social stigma and provider bias can result in the reluctant usage of health services, with implications on individuals’ SRHR. Evidence shows that, in certain contexts, service providers are not comfortable with providing family planning services to young, unmarried women without children (Solo and Festin, 2019[52]), and they discourage newly-married women from using contraception, in order to fulfil their role as mothers (Oduenyi et al., 2021[53]). Sexual orientation and gender identity can further heighten individuals’ risk of discrimination when seeking sexual and reproductive health advice or treatment. Finally, social stigma can prevent individuals from accessing quality information and/or seeking relevant care. Digital media and online resources can be useful tools to provide such information and advice but also bear certain risks for users (see Chapter 3).

The intersection of structural barriers and gender-based discrimination creates inequalities within and across countries

People across the world face different structural realities and challenges. At the country level, resources – or the lack of them – determine the quality and reach of healthcare systems. This includes the number of available healthcare facilities within reach, the reliability of commodity supply and the number of healthcare providers that received specific training, e.g. on gender-sensitive service provision (WHO, 2010[54]) (Roozbeh, Nahidi and Hajiyan, 2016[55]). Similarly, resources are required to establish well-functioning education systems, which are a necessary precondition for children and adolescents to access comprehensive sexuality education as taught in school. In times of crises and conflict, resources may be diverted to other issues, threatening the adequate and uninterrupted provision of sexual and reproductive health services.

In countries where the reach of affordable sexual and reproductive health care is limited, individual financial constraints and/or residence in remote areas can create inequalities in access. Discrimination on the basis of gender, sexual orientation, disability or education can further exacerbate inequalities within countries. When intersecting with discriminatory social institutions, adolescents, women and marginalised populations living in remote areas are most likely to be left behind.

Mitigating the impacts of climate change requires empowering women as agents of change

Among the multiple and simultaneous shocks the world currently faces, the impacts of climate change are systemic, profoundly and rapidly transforming and reshaping the world’s social, economic and political landscape. The effects of climate change can substantially exacerbate women’s vulnerabilities – for instance by increasing the time they dedicate to collecting firewood or by increasing their exposure to gender-based violence in the aftermath of disasters – and hamper their well-being in specific and sometimes disproportionate ways. These gendered consequences of climate change have been increasingly recognised since the early 1990s, and efforts to address them have strongly accelerated following the 2014 Lima Work Programme on Gender and the 2015 Paris Agreement, which highlights the need to develop and implement gender-responsive national climate policies (UNFCCC, 2015[56]; UNFCCC, 2014[57]).

Nevertheless, women’s inclusion as agents of change in designing and implementing responses that mitigate the impacts of climate change remains limited. Today almost 60% of long-term low-emission development strategies do not account for gender dynamics (UNFCCC, 2022[58]). Not only does excluding women weaken the effectiveness of the strategies aimed at coping with the effects of climate change, but it also constitutes a lost opportunity. Indeed, the policy and programmatic responses to the effects of climate change could constitute a window of opportunity to bridge gaps, empower women and put equality back at the heart of the global policy agenda.

Climate-resilient agriculture, disaster risk-reduction and renewable energy play crucial roles in mitigating the impacts of climate change and building resilience and capacity to adapt to its detrimental effects. Incorporating a gender perspective in climate change policies and initiatives from the outset can ensure that the needs and experiences of women are addressed and that their capacities are strengthened to cope with the impacts of climate change.

Empowering women farmers for climate-resilient agriculture

Climate change disproportionally affects women farmers and rural women due to structural gender inequalities and discriminatory social institutions (FAO, 2020[59]). Systemic gender inequalities result in women farmers generally having limited access to land, labour, smart technologies, agricultural inputs, and social and institutional networks (FAO, 2023[60]). Underlying drivers include discriminatory formal and informal laws restricting women’s ownership and management of agricultural land, but also gender norms that favour male decision-making power over land and resources, both at the household and public levels (UNFCCC, 2022[61]; FAO, 2020[59]). Moreover, smallholder farmers depend on natural resources for securing food, water and fuel and for their agricultural work. Climate change or shocks can reduce the availability of such resources in general and/or punctually, which disproportionately puts women farmers’ livelihoods at risk.

Yet, women around the world play a pivotal role in agriculture and rural economies and are key to build strong and resilient global food systems. The agricultural sector remains one of the largest employers of women in developing countries. In South Asia and sub-Saharan Africa, more than 50% of women are employed in agriculture, compared to 25% at the global level (World Bank, 2023[62]). Women farmers’ knowledge is an invaluable source of insights on resilience and good practices and should be used to guide climate-resilient agriculture adaptation and mitigation measures. Women have expertise in local crops, plants and trees and have a comprehensive knowledge of traditional, sustainable, and local farming and agricultural practices (FAO, 2017[63]). In addition, women are active members in co-operatives, producer organisations and rural committees. If given the means and a voice, women can be key agents of change to accelerate the shift towards climate-resilient agriculture.

Disaster risk reduction must be gender-inclusive to enhance resilience

The impact of climate-related hazards and disasters is not gender-neutral. Evidence reveals that disasters perpetuate and amplify gender inequality. On average, women and girls face higher risks than men during and in the aftermath of a disaster (UNHCHR, 2022[64]; CARE International, 2014[65]). These risks include the loss of livelihoods, exposure to gender-based violence, early and forced marriage, deterioration in sexual and reproductive health, increased workloads, and limited access to education. At the heart of these gendered consequences are the roles and responsibilities men and women have historically assumed which are shaped by patriarchal values and unequal power structures (Ciampi et al., 2011[66]).

Socio-economic factors, cultural norms and traditional practices are the root causes of the inequality between women, girls, men and boys which determine the gendered impact of climate-related disasters. Access to resources and decision-making power affects how women prepare for and respond to disasters (Nellemann, Verma and Hislop, 2011[67]). The feminisation of poverty, different hierarchies at the household level, inequalities in access to financial resources and gender-blind communication when disasters strike all fuel gender inequality while preventing inclusive disaster risk reduction and mitigation attempts. Among others, these factors notably decrease power, mobility, and agency for women and girls in moments of crisis.

While the post-disaster context presents diverse challenges for women, it is important to recognise that women are not just victims of disasters. Women are powerful agents of change during and after disasters, but their inclusion in the design and implementation of disaster risk reduction policies and programmes remains limited. Consequently, designed policies and interventions risk being gender-blind, thus failing to prevent and mitigate the gendered impacts of climate change-induced disasters. Enhancing societies’ resilience requires addressing the underlying factors that result in women being more vulnerable during and in the aftermath of disasters, as well as systematically integrating a gender lens into any disaster risk reduction strategy.

Including women is key to enhancing the reach and use of renewable energies

Women tend to be the main users and producers of energy at household and community levels. In developing countries, traditional energy sources – often biomass – are still largely used for cooking. Due to traditional gender roles and practices, women continue to carry the bulk of unpaid care and domestic work – which includes collecting energy sources for daily domestic tasks. The consequences of climate change such as deforestation, land degradation and desertification have a disproportionate impact on women by increasing the time necessary to collect fuel for cooking (OECD, 2021[68]). At the same time, relying on firewood to cook is among the many causes of deforestation, land degradation and desertification, all of which aggravate the impact of climate change (Boskovic, 2018[69]). Women are also at the forefront of the negative effects of using traditional energy sources, such as household air pollution (UN Women, 2018[70]).

While countries around the globe are increasingly adopting renewable energy, universal access is out of reach – particularly for women. Many women are affected by the energy poverty phenomenon, both in more advanced economies, where the issue of affordability of energy is the main preoccupation, and in less advanced economies, where the issues are centred on energy availability, access and reliability (OECD, 2021[68]). This is especially true in households that are not equipped with electricity, which means women have no other choice than to collect biomass for energy purposes (GI-ESCR, 2021[71]).

Gender equality and female empowerment can improve and accelerate access to the supply of sustainable energy. To avoid the worst impacts of climate change, the world needs to reduce its emissions by almost half by 2030 and must reach net zero by 2050 (United Nations, 2023[72]). In this context, renewable energy appears as one of the solutions, and women have a central role to play as energy professionals, energy decision makers and energy consumers (OECD, 2021[68]). Women’s uptake of renewable energies would not only empower them economically, but could also benefit whole communities as women are powerful agents of change and can play a leading role to help shift energy consumption to renewable sources (OECD, 2021[68]; OECD/ASEAN, 2021[73]). However, women’s lack of decision-making power in the household and at the community level, which stems from discriminatory social norms, limits their use of cleaner sources of energy and prevents them from making a meaningful contribution to energy-related decisions in projects that affect them (REN21, 2022[74]; Yi-Chen Han et al., 2022[75]; Lozano Alejandra et al., 2021[76]). Women also remain largely underrepresented in the renewable energy sector, and those who work in it face discriminatory norms and implicit biases that limit their opportunities, careers and professional advancement (UN Women, UNEP, n.d.[77]). A 2018 survey covering both individuals and companies from the renewable energy sector across 144 countries revealed that 75% of women believe that women working in this sector or seeking to join it face gender-related barriers, such as biases on gender roles and on women’s technical and physical competencies, prevailing hiring practices, lack of flexibility in the workplace and lack of mentorship opportunities (International Renewable Energy Agency, 2019[78]).

Policy makers, together with other key actors, must take bold action to eliminate discrimination in social institutions

Gender equality is still far from being achieved. As outlined in this chapter, the world is not on track to achieve SDG 5, nor is it on track to achieve all the other gender-related indicators and targets of the 2030 Agenda – which fundamentally matter to women’s and girls’ well-being. Addressing current gender gaps and inequalities requires a co-ordinated effort from all stakeholders, from policy makers to bilateral and multilateral development partners, private and philanthropic actors, academic and research institutes, as well as feminist and civil society organisations. To ensure no one is left behind, this effort requires embedding an intersectional approach across all actions and initiatives, accounting for the fundamental characteristics of individuals – such as age, sexual orientation, race, ethnicity, socio-economic status, class, religion, disability, place of residence, and so forth – that can exacerbate vulnerabilities and deepen the impact of discrimination and crises.

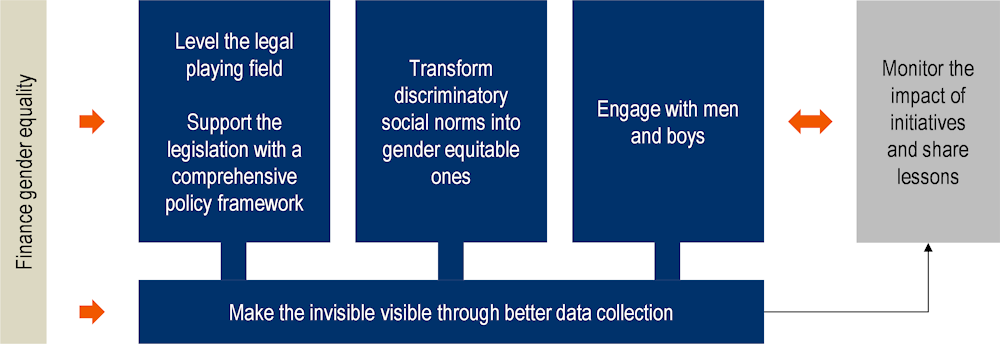

Results from the fifth edition of the SIGI shed light on the fundamental role of discriminatory social institutions in shaping gender inequalities. In this context, strengthening ongoing efforts and taking bold action to eradicate deeply embedded discrimination and transform social norms into gender-equitable ones are utmost priorities (Figure 1.4).

Figure 1.4. Policy options to advance gender equality and transform discriminatory social institutions into gender-equitable ones

Level the legal playing field and support the legislation with a comprehensive policy framework

Governments and policy makers must level the playing field to ensure men and women benefit from the same rights and opportunities.

Enact laws in favour of gender equality; reform and amend laws that contain discriminatory provisions: Ensuring that legal frameworks do not create inequalities between men and women and do not erect formal barriers to women’s empowerment is a fundamental prerequisite. Legislators should pay special attention to parallel and plural legal systems, notably when the coexistence of different legal systems – such as customary, statutory and/or religious rights – introduces incoherence and conflicting legal statuses.

Ensure that the legislation is enforced: Governments must ensure that existing laws apply. Moreover, individuals in general, and women in particular, do not necessarily know their rights or are aware of changes in the law. Efforts should therefore seek to raise awareness on the existing legislation to inform the population about their rights and provide free legal aid.

Develop national action plans and comprehensive strategies to guide and structure policies in favour of gender equality. For these legislative efforts to be effective, governments and policy makers should support the legislation with a comprehensive policy framework. In line with actions undertaken by many countries, and in order to go beyond the traditional perimeter of action of ministries of gender equality, these policy frameworks should systematically apply a gender lens and an intersectional approach to a broad range of areas, including economic affairs, education, employment and health.

Transform discriminatory social norms into gender‑equitable ones

To address the fundamental barriers to gender equality, governments and policy makers, together with civil society organisations, philanthropic organisations and the private sector, must design and implement policies and programmes that seek to transform discriminatory social norms into gender-equitable ones.

Leverage the power of edutainment and role models: Edutainment is the combination of education and entertainment in the form of soap operas, radio and television shows or delivered via chatbots. It constitutes a powerful tool to disseminate knowledge while deconstructing restrictive gender norms and promoting behavioural change. Productions in local languages and with local celebrities or influencers can increase the reach and acceptability and hence the impact of edutainment. To promote alternatives to the gender-restrictive status quo, leveraging the power of role models is also critical – both online and offline. Programmes and policies seeking to transform discriminatory social norms should engage with influencers and the media to shift the public discourse and promote more gender-equitable attitudes and behaviours.

Mobilise community leaders and gatekeepers: Transforming attitudes requires a whole-of-society approach that targets all individuals at all levels – from communities to national structures. Programmes and interventions designed to transform discriminatory social norms into gender-equitable ones must be carefully crafted to ensure they take into account all relevant stakeholders and include them from the outset. Specifically, interventions should be aware of the key role played by gatekeepers such as traditional and/or religious leaders, teachers, healthcare/education providers, and youth leaders. The social status of these individuals places them in a position to promote changes in social norms or maintain the status quo. Because social norms are collectively enforced, programmes limited to working with a single target group will be insufficient to achieve transformative change.

Recognise that the transformation of social norms takes time: Consistent commitment is required to change discriminatory attitudes and behaviours, in both developed and developing countries. This type of commitment requires sustained financial and technical support in favour of the organisations that are implementing interventions on the ground and/or promoting gender equality through their work. In developing countries, international development partners should closely work with the multiple actors in charge of designing and implementing programmes to allow for long-term programming over several years. These actors not only include governments and policy makers but also grassroots organisations and private development implementers. Budget should also be allocated for the monitoring and follow-up phases of programmes in order to evaluate their effectiveness, keep track of changes in norms and ensure that gains are sustained over time.

Engage with men and boys

Policies and programmes focusing on gender equality and aiming at transforming social norms must go beyond women and girls and should involve men and boys. Initiatives should seek to include areas that are often coined as relevant for girls and women only, such as maternal and newborn health.

Deconstruct traditional gender roles and responsibilities: Government and policy makers, together with all other actors, should develop and implement specific activities targeted at men and boys, including, for example, safe spaces where men and boys can learn about gender equality and discuss it without fear of judgement or receive training, support and resources on how to adopt more gender-equitable attitudes and behaviours.

Communicate on the benefits of gender equality for all: Governments and policy makers, with the active support of development partners, private sector actors as well as grassroots and civil society organisations, must invest in research and communication to show men and boys that gender equality is not a zero-sum game. Communication is key to ensuring the benefits of more gender-equal societies are clearly outlined and demonstrated to all, including how addressing norms of restrictive masculinities could substantially improve the well-being and mental health of men and boys.

Make the invisible visible through better data collection

To maximise impact and understand the true nature of discrimination, it is essential to make the invisible visible through better data collection.

Improve data collection and dissemination: Given the hidden nature of discriminatory social institutions and the current scarcity of good, comparable and timely gender-disaggregated, gender‑relevant and intersectional data, efforts to collect representative data and to expand their availability in terms of both coverage and quality are critical. Governments, through national statistical offices, must be at the heart of these efforts, with the active support of bilateral and multilateral development partners that are able to mobilise the necessary resources and statistical knowledge (PARIS21, 2023[79]).

Minimise costs: Strategies to develop and improve gender-disaggregated, gender-relevant and intersectional data should seek to minimise costs, for instance by incorporating gender equality indicators into surveys that are already carried out on a regular basis.

Seize new opportunities: With the emergence of new players and tools – technology firms, social networks, big data, Artificial Intelligence, etc. – the data landscape is rapidly evolving (Data2X, 2021[80]). The volume and timeliness of the generated data offer vast and new opportunities, especially to monitor the gendered impact of crises. Governments and policy makers, with the support of the private sector, development partners and research institutes, should seek to leverage these new data tools to improve the understanding of issues and the monitoring of policies and programmes. At the same time, they must ensure that shortcomings and risks are carefully monitored and handled, including issues related to privacy and lack of representative samples.

Monitor the impact of initiatives and share lessons

Building on quality data, all actors must strive to better monitor the impact of initiatives and share lessons about what works and what does not. It requires close co-operation among distinct actors on an equal footing, particularly to ensure that local expertise and best practices are taken into account.

Uncover the root causes of discriminatory social norms: To maximise impact and optimise the use of limited resources, it is critical to assess the impact of programmes and policies and to adapt them if necessary. Bilateral and multilateral development partners, philanthropic actors as well as academic institutions should invest time and resources in research to detect the most impactful approaches and to clearly identify the causes of discriminatory social norms.

Assess the gender impact of programmes and policies: As actors are increasingly expected to include a gender lens when designing and implementing programmes, policies, strategies and laws – including in initiatives for which gender equality is not a core objective – gender impact assessments are a useful tool to evaluate the effectiveness of gender mainstreaming. Gender impact assessments should serve to replicate useful programmes and adjust them when no or only limited impact is achieved.

Support civil society organisations and activists: In parallel, civil society organisations and activists must play a key role in holding governments and policy makers accountable for their actions and commitments towards gender equality, which requires clear metrics to track progress. Ensuring grassroots and feminist organisations are able to fulfil their accountability role requires development partners as well as philanthropic and private actors to support them technically and financially.

Financing gender equality

Achieving gender equality and the empowerment of all women and girls requires substantial investments. In a context of scarce resources, contributions from all actors should be leveraged, co-ordination should help minimise cost and innovative approaches should allow finding new sources of funding.

Increase the leverage of Official development assistance (ODA) for gender equality: In the context of development, members of the OECD Development Assistance Committee should aim to commit a substantial share of ODA to gender equality and women’s empowerment, which currently stands at 44% of ODA (OECD, 2023[81]; OECD, 2023[82]).

Complement efforts from development partners with innovative approaches, using new funding instruments: For instance, blended finance funds and facilities have the power to mobilise more financial resources for gender equality and the empowerment of women and girls (OECD, 2022[83]; OECD, 2022[84]). Private and philanthropic actors also have a critical role to play in supporting efforts from public actors through innovative approaches. For example, foundations could help de-risk investments by providing first-loss capital (Criterion Institute, 2020[85]).

Adopt good public financial management and budgeting tools: To improve the management and allocation of funds dedicated to advancing gender equality, governments and policy makers must adopt good practices such as gender-responsive public financial management and budgeting. These approaches require strong commitments from governments, combined with technical support from development partners and public finance experts, to expand the use of ex ante gender-impact assessments, gender budget tagging, gender budget statements and gender budget audits.

Mainstream gender into green financing: As green and sustainable financing tools are rapidly developing, policy makers must ensure that gender- and environment-related considerations do not operate in silos but are rather integrated into common metrics and tools. In particular, policy makers and development partners should systematically mainstream gender considerations in green infrastructure planning, financing, procurement and delivery. This would ensure that sustainable infrastructure better meets the needs of women and vulnerable groups while reducing environmental externalities and improving the quality of life for all (OECD, 2022[86]).

Finance frontline actors: Entities funding actions and initiatives in favour of gender equality and women’s empowerment must specifically target frontline actors, notably grassroots and feminist organisations, when it comes to financial support. These players, who relentlessly advocate for gender equality and know the issues through their direct interactions with project beneficiaries and evidence from the ground, are critical to the achievement of SDG 5. Yet, they are often ignored and tend to lack resources to deploy and maintain their programmes and to fulfil their strategic role of holding accountable other actors.

References

[45] Bearak, J. et al. (2020), “Unintended pregnancy and abortion by income, region, and the legal status of abortion: estimates from a comprehensive model for 1990–2019”, The Lancet Global Health, Vol. 8/9, pp. e1152-e1161, https://doi.org/10.1016/s2214-109x(20)30315-6.

[37] Berevoescu, I. and J. Ballington (2021), Women’s political representation in local governement: A global analysis, UN Women, New York, https://www.unwomen.org/sites/default/files/2022-01/Womens-representation-in-local-government-en.pdf.

[69] Boskovic, B. (2018), “The Effect of Forest Access on the Market for Fuelwood in India”, Toulouse School of Economics, https://publications.ut-capitole.fr/id/eprint/26050/1/wp_tse_925.pdf (accessed on 1 June 2023).

[51] Buller, A. and M. Schulte (2018), “Aligning human rights and social norms for adolescent sexual and reproductive health and rights”, Reproductive Health Matters, Vol. 26/52, pp. 38-45, https://doi.org/10.1080/09688080.2018.1542914.

[65] CARE International (2014), Evicted by Climate Change: Confronting the Gendered Impacts of Climate-Induced Displacement, https://www.care-international.org/sites/default/files/files/CARE-Climate-Migration-Report-v0_4.pdf (accessed on 1 June 2023).

[44] CEDAW (2022), Access to safe and legal abortion: Urgent call for United States to adhere to women’s rights convention, https://www.ohchr.org/en/statements/2022/07/access-safe-and-legal-abortion-urgent-call-united-states-adhere-womens-rights (accessed on 1 June 2023).

[66] Ciampi, M. et al. (2011), “Gender and disaster risk reduction: A training pack”, http://www.oxfam.org.uk (accessed on 1 June 2023).

[1] Cohen, G. and M. Shinwell (2020), “How far are OECD countries from achieving SDG targets for women and girls? : Applying a gender lens to measuring distance to SDG targets”, OECD Statistics Working Papers, No. 2020/02, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/17a25070-en.

[47] Crear-Perry, J. et al. (2021), “Social and Structural Determinants of Health Inequities in Maternal Health”, Journal of Women’s Health, Vol. 30/2, https://doi.org/10.1089/JWH.2020.8882.

[85] Criterion Institute (2020), Gender as Material to Infrastructure Projects: Reaching Better Outcomes by Applying a Gender Lens from Project Inception, https://www.convergence.finance/resource/gender-as-material-to-infrastructure-projects:-reaching-better-outcomes-by-applying-a-gender-lens-from-project-inception/view.

[80] Data2X (2021), The Landscape of Big Data and Gender, https://data2x.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/Landscape-of-Big-Data-and-Gender_3.5_FINAL.pdf.

[2] Equal Measures 2030 (2022), 2022 SDG Gender Index, https://www.equalmeasures2030.org/2022-sdg-gender-index/.

[87] Equality Now (2021), Consent-Based Rape Definitions, https://www.equalitynow.org/resource/consent-based-rape-definitions/.

[60] FAO (2023), The status of women in agrifood systems, FAO, https://doi.org/10.4060/cc5060en.

[59] FAO (2020), “Agriculture and climate change – Law and governance in support of climate smart agriculture and international climate change goals”, Legislative Studies, No. 115, FAO, https://doi.org/10.4060/cb1593en.

[63] FAO (2017), Enabling policies and institutions for gender-responsive climate-smart agriculture, https://www.fao.org/climate-smart-agriculture-sourcebook/enabling-frameworks/module-c6-gender/chapter-c6-7/en/.

[7] Ferrant, G. and A. Kolev (2016), “Does gender discrimination in social institutions matter for long-term growth?: Cross-country evidence”, OECD Development Centre Working Papers, No. 330, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/5jm2hz8dgls6-en.

[71] GI-ESCR (2021), Women’s Participation in the Renewable Energy Transition: A Human Rights Perspective, https://www.geres.eu/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/Briefing-paper-on-womens-participation-in-the-energy-transition-1.pdf (accessed on 15 May 2023).

[19] Göckeritz, S., M. Schmidt and M. Tomasello (2014), “Young children’s creation and transmission of social norms”, Cognitive Development, Vol. 30, pp. 81-95, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cogdev.2014.01.003.

[42] Guttmacher Institute and Lancet (2018), Accelerate Progress: Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights for All — Executive Summary | Guttmacher Institute, https://www.guttmacher.org/guttmacher-lancet-commission/accelerate-progress-executive-summary.

[12] Inglehart, R. et al. (2022), “World Values Survey: All Rounds – Country-Pooled Datafile Version 3.0”, World Values Survey, JD Systems Institute and WVSA Secretariat, Madrid, Spain and Vienna, Austria, https://www.worldvaluessurvey.org/WVSDocumentationWVL.jsp (accessed on 1 June 2023).

[30] International Labour Organization (2023), World employment and social outlook : Trends 2023, ILO, Geneva, https://doi.org/10.54394/sncp1637.

[33] International Labour Organization (2021), “World: Employment by sex and economic activity - ILO modelled estimates, Nov. 2022 (thousands)”, Statistics on employment, ILOSTAT, https://www.ilo.org/shinyapps/bulkexplorer45/?id=X01_A&indicator=EMP_2EMP_SEX_ECO_NB (accessed on 1 June 2023).

[34] International Labour Organization (2019), Global Wage Report 2018/19: What lies behind gender pay gaps, ILO, Geneva, https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---dgreports/---dcomm/---publ/documents/publication/wcms_650553.pdf.

[31] International Labour Organization (2018), Care work and care jobs for the future of decent work, ILO, Geneva, https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---dgreports/---dcomm/---publ/documents/publication/wcms_633135.pdf.

[78] International Renewable Energy Agency (2019), Renewable energy: A gender perspective, https://www.irena.org/publications/2019/Jan/Renewable-Energy-A-Gender-Perspective.

[35] Inter-Parliamentary Union (2023), IPU Parline, https://data.ipu.org/.

[36] Inter-Parliamentary Union and UN Women (2023), “Women in politics: 2023” map, https://www.unwomen.org/en/digital-library/publications/2023/03/women-in-politics-map-2023.

[22] Kabeer, N. (2009), “Women’s economic empowerment: Key issues and policy options”, Women’s Economic Empowerment, SIDA, https://www.empowerwomen.org/en/resources/documents/2015/10/womens-economic-empowerment-key-issues-and-policy-options.

[49] Liang, M. et al. (2019), “The State of Adolescent Sexual and Reproductive Health”, Journal of Adolescent Health, Vol. 65/6, pp. S3-S15, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2019.09.015.

[76] Lozano Alejandra et al. (2021), Towards a Gender-Just Transition: A Human Rights Approach to Women’s Participation in the Energy Transition, https://gi-escr.org/en/resources/publications/women.

[25] Maswikwa et al. (2015), “Minimum Marriage Age Laws and the Prevalence Of Child Marriage and Adolescent Birth: Evidence from Sub-Saharan Africa”, International Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health, Vol. 41/2, p. 58, https://doi.org/10.1363/4105815.

[24] McGavock, T. (2021), “Here waits the bride? The effect of Ethiopia’s child marriage law”, Journal of Development Economics, Vol. 149, p. 102580, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdeveco.2020.102580.

[32] Mohapatra, K. (2012), “Women Workers in Informal Sector in India: Understanding the Occupational Vulnerability”, International Journal of Humanities and Social Science, Vol. 2/21, http://www.ijhssnet.com.

[48] Moreau, C. et al. (2020), “Reconceptualizing Women’s and Girls’ Empowerment: A Cross-Cultural Index for Measuring Progress Toward Improved Sexual and Reproductive Health”, International Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health, Vol. 46, pp. 187-198, https://doi.org/10.1363/46e9920.

[67] Nellemann, C., R. Verma and L. Hislop (2011), Women at the Frontline of Climate Change. A Rapid Response Assessment., United Nations Environment Programme, Norway.

[29] Nnyombi, A. et al. (2022), “How social norms contribute to physical violence among ever-partnered women in Uganda: A qualitative study”, Frontiers in Sociology, Vol. 7, https://doi.org/10.3389/fsoc.2022.867024.

[53] Oduenyi, C. et al. (2021), “Gender discrimination as a barrier to high-quality maternal and newborn health care in Nigeria: findings from a cross-sectional quality of care assessment”, BMC Health Services Research, Vol. 21/1, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-021-06204-x.

[82] OECD (2023), Development finance for gender equality and women’s empowerment, https://www.oecd.org/dac/financing-sustainable-development/development-finance-topics/development-finance-for-gender-equality-and-women-s-empowerment.htm (accessed on 1 June 2023).

[20] OECD (2023), Joining Forces for Gender Equality: What is Holding us Back?, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/67d48024-en.

[81] OECD (2023), Official development assistance for gender equality and women’s empowerment in 2020-21: A snapshot, OECD, https://www.oecd.org/dac/official-development-assistance-gender-equality.pdf.

[9] OECD (2023), “Social Institutions and Gender Index (Edition 2023)”, OECD International Development Statistics (database), https://doi.org/10.1787/33beb96e-en (accessed on 19 May 2023).

[5] OECD (2023), The OECD’s Contribution to Promoting Gender Equality, OECD Ministerial Council Meeting 2023, https://www.oecd.org/mcm/documents/The-OECD-Contribution-to-Promoting-Gender-Equality.pdf.

[84] OECD (2022), Blended finance for gender equality and the empowerment of women, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://www.oecd.org/dac/2022-blended-finance-gender-equality.pdf.

[83] OECD (2022), Gender Equality and the Empowerment of Women and Girls: Guidance for Development Partners, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/0bddfa8f-en.

[38] OECD (2022), Report on the implementation of the OECD Gender Recommendations, https://www.oecd.org/mcm/Implementation-OECD-Gender-Recommendations.pdf.

[86] OECD (2022), “Supporting women’s empowerment through green policies and finance”, OECD Environment Policy Papers, No. 33, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/16771957-en.

[68] OECD (2021), Gender and the Environment: Building Evidence and Policies to Achieve the SDGs, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/3d32ca39-en.

[21] OECD (2021), Man Enough? Measuring Masculine Norms to Promote Women’s Empowerment, Social Institutions and Gender Index, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/6ffd1936-en.

[8] OECD (2020), Call to Action for the OECD: Taking Public Action to End Violence at Home, https://www.oecd.org/gender/VaW2020-Call-to-Action-OECD.pdf.

[28] OECD (2020), Issues Notes: OECD High-Level Conference on Ending Violence Against Women, OECD, Paris, https://www.oecd.org/gender/VAW2020-Issues-Notes.pdf.

[6] OECD (2019), SIGI 2019 Global Report: Transforming Challenges into Opportunities, Social Institutions and Gender Index, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/bc56d212-en.

[39] OECD (2016), 2015 OECD Recommendation of the Council on Gender Equality in Public Life, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264252820-en.

[16] OECD Development Centre/OECD (2023), “Gender, Institutions and Development (Edition 2023)”, OECD International Development Statistics (database), https://doi.org/10.1787/7b0af638-en (accessed on 17).

[23] OECD Development Centre/OECD (2023), SIGI 2023 Legal Survey, https://oe.cd/sigi.

[17] OECD Development Centre/OECD (2019), “Gender, Institutions and Development (Edition 2019)”, OECD International Development Statistics (database), https://doi.org/10.1787/ba5dbd30-en.

[18] OECD Development Centre/OECD (2014), “Gender, Institutions and Development (Edition 2014)”, OECD International Development Statistics (database), https://doi.org/10.1787/data-00728-en.

[73] OECD/ASEAN (2021), Strengthening Women’s Entrepreneurship in Agriculture in ASEAN Countries, https://www.oecd.org/southeast-asia/regional-programme/networks/OECD-strengthening-women-entrepreneurship-in-agriculture-in-asean-countries.pdf (accessed on 5 April 2023).

[79] PARIS21 (2023), Couting on Gender Data: Findings from Gender Statistics Assessments in Nine Countries, https://paris21.org/node/3565.

[50] Pulerwitz, J. et al. (2019), “Proposing a Conceptual Framework to Address Social Norms That Influence Adolescent Sexual and Reproductive Health”, Journal of Adolescent Health, Vol. 64/4, pp. S7-S9, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2019.01.014.

[74] REN21 (2022), Renewables 2022 Global Status Report, https://www.ren21.net/gsr-2022/ (accessed on 4 April 2023).

[55] Roozbeh, N., F. Nahidi and S. Hajiyan (2016), “Barriers related to prenatal care utilization among women”, Saudi Medical Journal, Vol. 37/12, pp. 1319-1327, https://doi.org/10.15537/smj.2016.12.15505.

[52] Solo, J. and M. Festin (2019), “Provider Bias in Family Planning Services: A Review of Its Meaning and Manifestations”, Global Health: Science and Practice, Vol. 7/3, pp. 371-385, https://doi.org/10.9745/GHSP-D-19-00130.

[70] UN Women (2018), Turning Promises into Action: Gender Equality in the 2030 agenda for Sustainable Development, https://www.unwomen.org/sites/default/files/Headquarters/Attachments/Sections/Library/Publications/2018/SDG-report-Gender-equality-in-the-2030-Agenda-for-Sustainable-Development-2018-en.pdf (accessed on 6 April 2023).

[77] UN Women, UNEP (n.d.), EmPower: Women for Climate-Resilient Societies, https://www.empowerforclimate.org/en/resources/g/e/n/gender-integration-in-renewable-energy-policy (accessed on 4 April 2023).

[43] UNAIDS (2021), Young people and HIV, https://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/young-people-and-hiv_en.pdf (accessed on 13 April 2023).

[10] UNDP (2021), “Gender Development Index (GDI)”, Thematic Composite Indices (database), https://hdr.undp.org/gender-development-index#/indicies/GDI.

[11] UNDP (2021), “Gender Inequality Index (GII)”, Thematic Composite Indices (database), https://hdr.undp.org/data-center/thematic-composite-indices/gender-inequality-index#/indicies/GII.

[61] UNFCCC (2022), Dimensions and examples of the gender-differentiated impacts of climate change, the role of women as agents of change and opportunities for women, https://unfccc.int/documents/494455.

[58] UNFCCC (2022), Implementation of gender-responsive climate policies, plans, strategies and action as reported by Parties in regular reports and communications under the UNFCCC, https://unfccc.int/sites/default/files/resource/cp2022_06E.pdf.

[56] UNFCCC (2015), The Paris Agreement, https://unfccc.int/process-and-meetings/the-paris-agreement (accessed on 1 June 2023).

[57] UNFCCC (2014), Decision 18/CP.20: Lima work programme on gender, United Nations, https://unfccc.int/resource/docs/2014/cop20/eng/10a03.pdf#page=35.

[46] UNFPA (2022), Seeing the unseen. The case for action in the neglected crisis of unintended pregnancy, https://www.unfpa.org/swp2022 (accessed on 12 May 2023).

[40] UNFPA (2020), Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Family Planning and Ending Gender-based Violence, Female Genital Mutilation and Child Marriage, https://www.unfpa.org/sites/default/files/resource-pdf/COVID-19_impact_brief_for_UNFPA_24_April_2020_1.pdf (accessed on 25 August 2020).

[64] UNHCHR (2022), Gender, Displacement and Climate Change, https://www.unhcr.org/5f21565b4.pdf (accessed on 3 April 2023).

[13] UNICEF (2023), Is an End to Child Marriage within Reach? Latest trends and future prospects. 2023 update, UNICEF, New York, https://data.unicef.org/resources/is-an-end-to-child-marriage-within-reach/.

[26] UNICEF (2023), Prospects for Children in Polycrisis: A 2023 Global Outlook, Innocenti Publications, UNICEF Office of Research - Innocenti, Florence, https://www.unicef.org/globalinsight/media/3001/file/UNICEF-Innocenti-Prospects-for-Children-Global-Outlook-2023.pdf.

[14] UNICEF (2022), “Percentage of women (aged 20-24 years) married or in union before age 18”, UNICEF Data Warehouse (database), https://data.unicef.org/resources/data_explorer/unicef_f/.

[4] UNICEF (2021), COVID-19: A threat to progress against child marriage, UNICEF, New York, https://data.unicef.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/UNICEF-report-_-COVID-19-_-A-threat-to-progress-against-child-marriage-1.pdf.

[15] UNICEF (2018), Child Marriage: Latest trends and future prospects, UNICEF, New York, https://data.unicef.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/Child-Marriage-Data-Brief.pdf.

[72] United Nations (2023), Climate Action: Renewable energy – powering a safer future, https://www.un.org/en/climatechange/raising-ambition/renewable-energy (accessed on 1 June 2023).

[3] United Nations (2022), The Sustainable Development Goals Report 2022, United Nations, New York, https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/report/2022/The-Sustainable-Development-Goals-Report-2022.pdf.

[27] United Nations (1993), Declaration on the Elimination of Violence against Women, General Assembly resolution 48/104, United Nations, https://www.ohchr.org/en/instruments-mechanisms/instruments/declaration-elimination-violence-against-women.

[54] WHO (2010), Increasing access to health workers in remote and rural areas through improved retention, https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/44369/9789241564014_eng.pdf;jses (accessed on 25 April 2023).

[41] Women Deliver (2021), The Link between Climate Change and Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights, https://womendeliver.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/Climate-Change-Report.pdf (accessed on 21 April 2023).