This chapter provides an overview of the recent reform package in the institutions and organisations in the Italian labour market called the Jobs Act. Alongside its objective to reform the labour market to introduce flexicurity, the Jobs Act aims to restructure the system of employment services and to increase the quality of active labour market policies. The chapter discusses the first steps of the reform process such as establishing the network of employment services, creating the National Agency for Active Labour Market Policies to coordinate the network and introducing activation conditionality on benefit recipients. Furthermore, it displays the challenges of the implementation processes stemming from underdeveloped IT infrastructure and insufficient human resources in the local employment offices.

Strengthening Active Labour Market Policies in Italy

Chapter 2. Reforming the institutional landscape

Abstract

The statistical data for Israel are supplied by and under the responsibility of the relevant Israeli authorities. The use of such data by the OECD is without prejudice to the status of the Golan Heights, East Jerusalem and Israeli settlements in the West Bank under the terms of international law.

2.1. Introduction

Italy launched a set of reforms in 2014‑16 to address its deeply-rooted economic challenges. This chapter discusses the reform in the institutions and organisations in the Italian labour market called the Jobs Act, focussing on the reform process concerning strengthening the system of employment services.

The Jobs Act aims to introduce the flexicurity model in the Italian labour market by reforming the employment protection legislation, the system of unemployment benefits and the active labour market policies. Modest positive effects have occurred during the first few years since the changes regarding labour market flexibility and unemployment benefits were introduced. The number of new open-ended contracts increased by 63% in 2015 (though only temporarily) and the coverage of unemployment benefits increased from 6.7% in 2014 to 7.8% in 2016 (the share of unemployed receiving unemployment benefits).

Progress towards stronger active labour market policies has been more cumbersome. The design of the Jobs Act has good potential to significantly enhance the system of employment services. However, the implementation process has to be improved by stronger co‑operation between the stakeholders of the network of employment services (involving putting monitoring and accountability system in place), establishing the National Agency for Active Labour Market Policies as a strong support unit for local employment offices, building a modern IT infrastructure supporting local offices and strengthening the local offices regarding their staff numbers, skills and processes in place.

The chapter proceeds as follows. The second section provides a general overview of the Jobs Act and its objectives, particularly the changes that were introduced to increase labour market flexibility and the changes in the unemployment benefit system. The third section discusses the efforts to strengthen the system of employment services, in particular the restructuring of the system and the attempts to increase service quality. It discusses also the efforts to link unemployment benefits with activation conditionality, the establishment of the new National Agency for Active Labour Market Policies and the IT infrastructure and capacity of the local employment offices needed to implement the Jobs Act. The final section concludes the chapter.

2.2. Reforming the labour market

The Jobs Act, the latest reform of the labour market in Italy, introduces the flexicurity concept resting on three pillars: changing employment protection legislation (flexibility), reforming the benefit system (security) and strengthening the system of active labour market policies. The introduction of a single type of permanent contract and the exemptions from social security contributions for new contracts have reduced the labour market duality to some extent by encouraging converting temporary contracts to permanent positions and triggering new employment relationships. The coverage of unemployment benefits has increased as a new universal unemployment benefit scheme has been introduced and the weakly targeted wage supplementation schemes have been cut.

2.2.1. Objectives of the Jobs Act

The deep and lengthy economic crisis demonstrated Italy’s long-standing productivity problems, urging the Italian government to launch a set of broad and complementary reform strategies in 2014-16 in order to strengthen the economy and the labour market. Within this framework, the Italian government set a goal to modernise labour market institutions by implementing the “Jobs Act” as a major reform of the labour market. One of the main objectives of the reform is to create a new comprehensive and inclusive model of labour market governance to support employment growth. In March 2014, some preliminary new measures were introduced with the so-called “Poletti decree” to foster employment and simplify bureaucratic procedures for temporary contracts. Subsequently, a wide‑ranging law was passed in December 2014 that enabled passing eight legislative decrees in the following months, covering an extensive set of issues from active and passive labour market policies to reconciling work and family life. These decrees were all adopted by September 2015.

On the one hand, the reform relaxed employment protection legislation for open‑ended contracts while increasing stability for temporary workers, relying on a combination of hiring incentives and a reduction in firing costs. On the other hand, it aims at strengthening active labour market policies that have been traditionally very weak in Italy, while also reforming passive policies by linking them with active labour market policies through conditionality provisions and activation strategies.

More flexibility for firms is offset by more “security” for workers in the labour market. The “security” relies on the interplay of two components: i) income sustainability by means of solid benefit schemes and ii) concrete help that can be provided through ALMPs in order to re-integrate people in the labour market. With the intention of strengthening the governance of ALMPs and integrating them with unemployment benefits, the government created a new state agency – Agenzia Nazionale per le Politiche Attive del Lavoro (ANPAL) – assigning it with the tasks of modernising the Italian system of employment services and providing a new set of tools and incentives to apply conditionality of benefits and activate jobseekers. The original idea of the Jobs Act was to transfer the competencies and responsibilities for the design and delivery of ALMPs from the provincial to the national level. However, this restructuring needed a change in the constitution. The rejection of the constitutional referendum in December 2016 put a halt to this plan and it has only been possible to transfer the responsibilities from the provincial to the regional level.

The “Jobs Act” reform included also other novelties to modernise labour market regulation such as advancing greater organisational flexibility by allowing employers to modify duties of their employees in the course of the employment relationships. Other changes included a relaxation of some restrictions on remotely controlling workers, a simplification of administrative procedures encouraging the use of telematic channels to interact with labour market authorities, a unification of different separate inspectorates into a single National Work Inspectorate and new work-life balance measures that relaxed some criteria for parental leave.

The “Jobs Act” has been complemented by two additional reforms, Buona Scuola and Industria 4.0, aiming jointly at boosting productivity and improving the ability of the economy to adjust to external shocks due to global changes (Pinelli et al. (2017[1])). Buona Scuola aims more specifically at reinforcing skills formation and the linkages between education and work (see Box 2.1). The goal of Industria 4.0 is to stimulate innovative production systems and to boost them towards the technological frontier (see Box 2.2). These three reforms complement each other well as together they have the potential to increase the supply of skilled labour, the demand for skilled labour and improve the matching between the two.

Box 2.1. Buona Scuola

Skill mismatch and skill shortages have seriously affected Italian labour market and productivity in recent years, in addition to high levels of youth unemployment (ISTAT, 2016[2]), (OECD, 2017[3]). Among the provisions of Buona Scuola, a special chapter has been devoted to this problem, attempting to address the Italian skill imbalance by a tool called Alternanza Scuola-Lavoro (ASL), a work-based learning program aimed at improving school-to-work transition. This scheme has been a part of the Italian educational system already since 2003, playing however only a marginal role before Buona Scuola as it was not compulsory. The reform has substantially strengthened the tool introducing compulsory internship periods in secondary schools, both for vocational education tracks (technical and professional schools), for an amount of 400 hours, and for humanistic and scientific general education (licei, usually oriented to continue to study at the University), for 200 hours. This reform has the potential to improve the alignment between educational programs and employers’ needs, with the aim of overcoming the unfortunate tradition of scarce interaction between schools and firms.

ASL represents an attempt to emulate German dual vocational training system” (Duales System). However, important differences still remain between the two countries. The German model combines high public and private investments. The expenditure for the Duales System shows that 96.1% of new contracts in 2015 were mostly financed by companies, as opposed to 4.9% mostly publicly financed positions (BIBB, 2017[4]). Social partners and firms’ representatives are involved in the management of the dual vocational training system as well. This is different in Italy, where the participation of the firms’ representatives in the administration of vocational schools was abolished more than forty years ago (Decree 416/1974). At the same time, while the German model provides a real work experience, based on an apprenticeship contract and aimed at the achievement of standardised qualification degrees, in the Italian ASL, schools rely both on “soft” activities (such as orientation, visits to the companies, meetings with company staff), and more “heavy and demanding” activities (such as internships integrated with teaching, project works performed by students for companies, business simulations). The role of the state dominates in the funding of the system. Law 107/2015 earmarked 100 million per year from 2016 onwards to finance ASL, with the possibility to add further resources coming from the private sector, depending on the specific partnership implemented at the local level.

The first results of the reform are promising. For example, 90.6% of the graduate year students got enrolled to the work-based training program in 2015/2016 covering 96% of the high schools compared to only 17% of students covering 54% of high schools a year before (INDIRE, 2016[5]).

Source: ISTAT (2016[2]), Rapporto annuale. La situazione del Paese, https://www.istat.it/storage/rapporto-annuale/2018/Rapportoannuale2018.pdf; OECD (2017[3]), Getting Skills Right: Italy, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264278639-en; BIBB (2017[4]), Datenreport zum Berufsbildungsbericht 2017, https://www.bibb.de/dokumente/pdf/bibb_datenreport_2017.pdf; INDIRE (2016[5]), Presentati al Miur il monitoraggio nazionale e il programma “I Campioni dell’Alternanza”, www.indire.it/2016/10/18/presentati-al-miur-il-monitoraggio-nazionale-e-i-campioni-dellalternanza/.

Box 2.2. Industria 4.0

Inspired by similar national strategies in Germany (Platform Industrie 4.0) and France (Alliance Industrie du Futur), the Italian Ministry for Economic Development presented “Industria 4.0 National Plan” in September 2016. The government earmarked approximately EUR 20 billion s with the budgetary law 2017 for this National Plan.

Industria 4.0 (I4.0) represents an ambitious set of measures aiming at supporting industrial change and boosting the competitiveness of Italian companies. These measures correspond to: tax-benefits based on different incentive structures; facilitation of firms’ access to investments oriented to technological transformation; and R&D initiatives and digital upskilling of workers. The main objectives of the reform are the support of innovative investments and the empowerment of skills related to the fourth industrial revolution. Big data, cloud computing, advanced internet connection, 3D printing and robots are some examples of technologies that firms can implement in their manufacturing production relying on tax benefits. Furthermore, concerning the empowerment of skills, I4.0 foresees several measures focusing on educational programs such as “Scuola Digitale” (a national programme modernising and restructuring learning processes of digital knowledge) and interacts with Alternanza Scuola-Lavoro (a work-based learning program aimed at improving school‑to‑work transition ), mainly strengthening the potential of technical high schools (Istituti Tecnici Superiori) for projects related to I4.0 topics.

To support the whole framework, a “National Network Industria 4.0” assists firms in digital transformation, disseminating knowledge and expertise related to the benefits emerging from the Plan, identifying technology needs, stimulating research projects and development.

The Plan has been relaunched, adding further 9.8 billion with the budgetary law 2018. A decree in June 2018 has also introduced new experimental incentives for digital upskilling of workers, recognising tax credits for training courses related to I4.0 topics, up to a yearly amount of EUR 300 000.

SVIMEZ (Cappellani and Prezioso, 2017[6]) has evaluated the impact of the policy at the territorial level. The main results show that investments will be 4 percentage points higher in the South compared to the Centre-North of the country. At the same time, regions in the Centre-North are those that should benefit more in the long-term, by an increase in productivity equal to 0.6 percentage points compared to the 0.2 in the South.

ISTAT (2018[7]) has conducted both a survey among firms and an econometric evaluation to study preliminary effects of the I4.0 reform. The majority of firms across all sectors consider the measures relevant for their investment decisions. At the same time, it is estimated that the tax benefits should produce an increase in the total increase of investments of 0.1 percentage points in 2018 and 0.2 in 2019 compared with 2017. Tax credits associated with R&D should lead to positive effects in terms of hiring specialists on topics related to I4.0.

Source: Cappellani, L. and S. Prezioso (2017[6]), Il “Piano nazionale Industria 4.0”: una valutazione dei possibili effetti nei sistemi economici di Mezzogiorno e del Centro-Nord, https://www.svimez.info/images/note_ricerca/2017_07_10_industria_4_0_nota.pdf; ISTAT (2018[7]) Rapporto sulla competitività dei settori produttivi. Edizione 2018, https://www.istat.it/storage/settori-produttivi/2018/Rapporto-competitivita-2018.pdf.

2.2.2. Decreasing labour market duality and fostering employment

Historically, firing costs have been high for permanent contracts in Italy which has hindered job creation and increased labour-market duality with respect to permanent and fixed‑term workers. Increasing labour market flexibility has been the aim of several reforms since the nineties when different types of fixed-term contracts were introduced. Introducing additional types of fixed-term contracts, however, did not increase flexibility, but rather fostered labour market dualism as the fixed-term contracts were also used as a cheap screening device before hiring on a permanent contract, other than using these contracts for temporary labour demand (Sestito and Viviano, 2016[8]).

Italy used to have uncertain and potentially high firing costs in case of open-ended contracts as an unfair dismissal meant reinstatement of the employee or paying up to six‑months‑salary1 preceded by a lengthy legal process. The “Fornero reform” in 2012 tried to lower the firing costs and the uncertainty of these costs for open-ended contracts by limiting the possibilities for reinstatement and shortening the related legal processes (Sestito and Viviano, 2016[8]). The uncertainty of firing costs was cut further by the Jobs Act in 2015 by restricting the grounds for reinstatement in cases of dismissal without just cause for newly signed permanent contracts (after 7 March 2015) of firms with more than 15 employees. Additionally, the Jobs Act replaced the different forms of open‑ended contracts with one permanent contract type with severance payments increasing with the job tenure (tutele crescenti). Following these changes, the strictness of employment protection legislation for permanent workers against individual dismissals has fallen from 2.74 to 2.54 in 2015 [preliminary estimations by Garda (2017[9])], leading to a smaller gap in protection between permanent and temporary contracts.

Moreover, all new permanent contracts were exempted from the social security contributions in 2015 (capped at EUR 8 060 annually for the first 3 years). In 2016, the social security exemptions were reduced (up to EUR 3 250 in 2 years). The budget for 2017 extended the social security exemptions for two more years, but limited them only to students newly hired to firms where they completed their internship or traineeship (up to EUR 3 250) or young workers hired in the southern regions with permanent or internship contracts [up to EUR 8 060, (OECD, 2017[10])].

Analysis of the reform conducted by the Italian National Institute of Social Welfare (Istituto Nazionale Previdenza Sociale, INPS), shows that the number of new open‑ended contracts increased indeed as expected in 2015 (by 63%), but fell again back to the 2014 level in 2016 when the social security exemptions were cut. The number of fixed‑term contracts increased as well in 2015 (although marginally), but continued to increase in 2016. The rise of new permanent contracts rose in 2015 both in terms of new hirings with permanent contracts as well of conversions of fixed-term contracts to permanent contracts (INPS, 2016[11]), (INPS, 2018[12]). In 2017, the number of new permanent contracts even decreased by 7% compared to 2014 (INPS, 2018[12]).

Additionally, the survival rates of employment relationships started by permanent contracts in the first quarter of 2015 using the social security exemptions have been higher in 12 and 18 months after the start of the relationship than the survival rates of those permanent contracts that did not yet use the social security exemption (signed in the first quarter of 2014; (INPS, 2017[13])). In 2019 it will be possible to estimate if these employment relationships have higher survival rates also beyond 36 months, the maximum period of social security exemptions for permanent contracts signed in 2015.

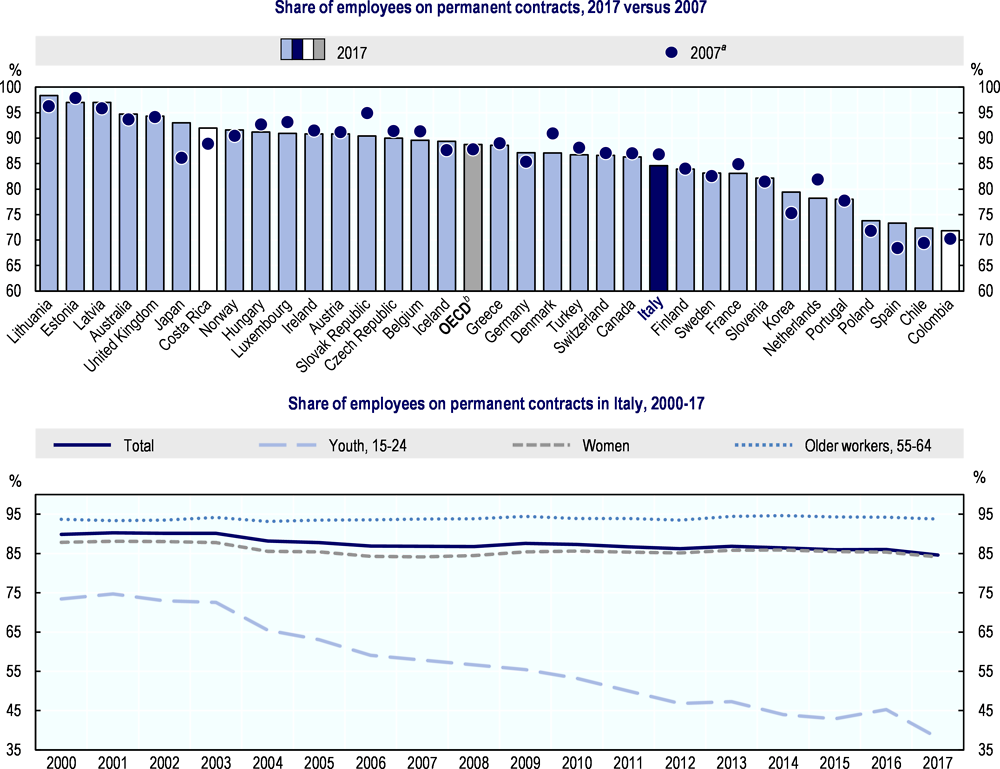

Despite the higher number of permanent contracts and their longer actual duration in 2015, the share of employees with permanent contracts has not visibly changed yet (Figure 2.1). The share of employees with permanent contracts has slightly decreased over the years and remained stable during the past few years in Italy, whereas this share has slightly increased over the past decade on average in the OECD countries (particularly in Spain and Japan).

Figure 2.1. The share of permanent contracts has not increased

a. 2010 instead of 2007 for Chile and Costa Rica.

b. Weighted average of the 32 OECD member countries shown in the chart above (data not available for Israel, Mexico, New Zealand and the United States). Colombia and Costa Rica are following the accession process to become OECD member countries.

Source: OECD Labour Force Database, Incidence of permanent employment Dataset, http://stats.oecd.org//Index.aspx?QueryId=9588.

The use of fixed-term contracts has been particularly common practice in Italy for young employees. During the past years, more than half of the young employees were working on short-term contracts. In 2016, the share of permanent contracts for young employees saw a slight increase, but in 2017 this share decreased again.

Sestito and Viviano (2018[14]) use microdata for the Veneto region and apply a difference‑in‑difference approach to estimate the impact of firing cost reductions and hiring incentives introduced in 2015. They conclude that the exemptions on social security contributions and changes in the employment protection legislation have both contributed to a reduction in the duality on the Italian labour market and have encouraged labour demand. However, by exploiting the differences in the design of the policies (differences in the timing of the announcement of the reforms and which firms and employees they concerned), they conclude that the larger part of the effect can be attributed to the social security exemptions. Nevertheless, the decrease in the uncertainty of firing costs had a significant effect on new permanent contracts. This was not only achieved through the effect of converting more temporary contracts into permanent ones, but also through the increased willingness of employers to hire new (yet “untested”) employees using permanent contracts. Cirillo et al. (2017[15]) have shown similarly that the effect of new permanent contracts has emerged mainly through monetary incentives, but also that the new permanent contracts were mostly fixed-term contracts transformed into permanent ones. A remarkable share (41% in January to September 2015) of new permanent contracts concerned part-time jobs, while the increase in employment concerned mostly older employees. The new permanent jobs emerged more in low-skilled and low-tech service sectors. The fact that the change in the employment protection legislation concerned firms with more than 15 employees is used by Boeri and Garibaldi (2018[16]) to study the effects of the new single type of permanent contract. They conclude that hiring with permanent contracts, the transformations of fixed-term contracts to permanent contracts and also firing increased in firms with more than 15 employees relative to smaller firms due to the changes in employment protection legislation.

However, more time is needed to estimate the longer term effects of the exemptions on the social security contributions and the changes in the employment protection legislation. Besides increasing employment, the reduction in employment protection has the potential to increase productivity through improved labour allocation and skill match as the firms can more easily adapt their workforce according to changing demand conditions and technology and as the workers have better opportunities to find better matching jobs (OECD, 2013[17]). Bassanini and Garnero (2013[18]) show additionally that the high extent of reinstatement in case of unfair dismissals, which has been the case in Italy, is a particularly hindering factor for worker flows. Skill mismatch has been one of the key problems on the Italian labour market hobbling productivity (see Chapter 1). Berton et al. (2017[19]) have shown that the Fornero reform, which was a step towards less strict employment protection before the introduction of the Jobs Act, indeed favoured labour reallocation, somewhat increased better skill matches and even led to a small increase in productivity. Similarly Hijzen et al. (2013[20]) show that before the Fornero reform higher employment protection in bigger firms was associated with lower labour productivity.

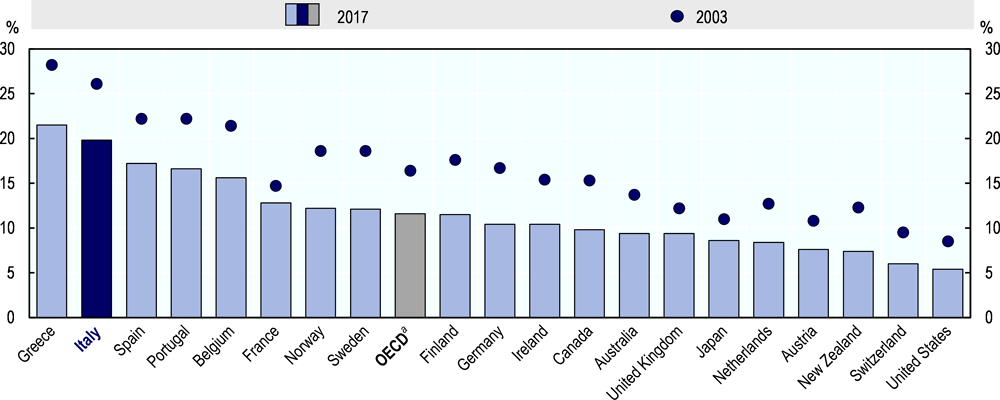

The exemptions form the social security contributions and the changes in the employment protection legislation together with concentrating all the inspection activity related to undeclared work in a single new body (National Inspection Agency) have also the potential to decrease the extent of undeclared work in the Italian labour market. A recent estimate by Schneider and Boockmann (2017[21]) puts the share of the shadow economy to close to 20% of GDP in 2017 (Figure 2.2). Although the share has recently decreased, it is still higher than in many other OECD countries. A study by the Study Foundation (Fondazione Studi) of Labour Consultants (Consulenti del Lavoro) claimed that in 2015 the number of persons informally employed decreased to 1.9 million i.e. 200 000 persons lower than the year before due to the Jobs Act and the three-year social security contributions exemptions (Consulenti del Lavoro, 2016[22]). If the conversion of informal employment to formal employment indeed has taken place during this period, the statistics for the additional employment contracts might overestimate the impact of the Jobs Act. Nevertheless, the study on the informal economy by ISTAT indicates that the total number of employees working unofficially (no formal employment contracts, including people working in a family business or farm) increased slightly in 2015 compared with 2014, from 3 667 thousand employees to 3 724 thousand employees [from 15.7% of employees to 15.9% of employees, (ISTAT, 2017[23])].

Figure 2.2. Italy has large shadow economy

a. Unweighted average of the 20 OECD member countries shown in the chart above.

Source: Data from Schneider, F. and B. Boockmann (2017), Die Größe der Schattenwirtschaft – Methodik und Berechnungen für das Jahr 2017, www.iaw.edu/index.php/aktuelles-detail/734.

Regardless of some positive effects on labour demand and the labour market duality due to the Jobs Act, recent developments in Italy have put further positive effects under question. First, the Italian Constitutional Court declared in the end of September 2018 that rigid indemnities upon unfair dismissal dependent solely on seniority are unconstitutional. Second, the new Italian government coming to power in 2018 increased the level of firing costs. The “Dignity Decree” approved in July 2018 states that in case of unfair dismissal, the employer has to cover for the employee salary costs for 6 to 36 months depending on tenure. Due to the decision by the Constitutional Court, the exact amount depends on the decision by the courts as the judge has to consider also other factors besides tenure. In addition, the Dignity Decree constrains the use of fixed-term contracts by decreasing its maximum duration and limiting possibilities to extend the contract (new fixed‑term contracts signed after 14 July 2018 or renewed after 31 October 2018). Although the aim of the Dignity Decree is to decrease the labour market duality by discouraging the use of fixed-term contracts, the changes introduced with this decree might make employers more hesitant to hire additional employees altogether which might limit further improvements in the employment rate.

2.2.3. Introducing more equal and universal unemployment benefits

The Italian unemployment benefit system has been characterised by long-lasting problems of fragmentation, limited and unequal coverage, generous levels and absence of any link between passive and active labour market policies.

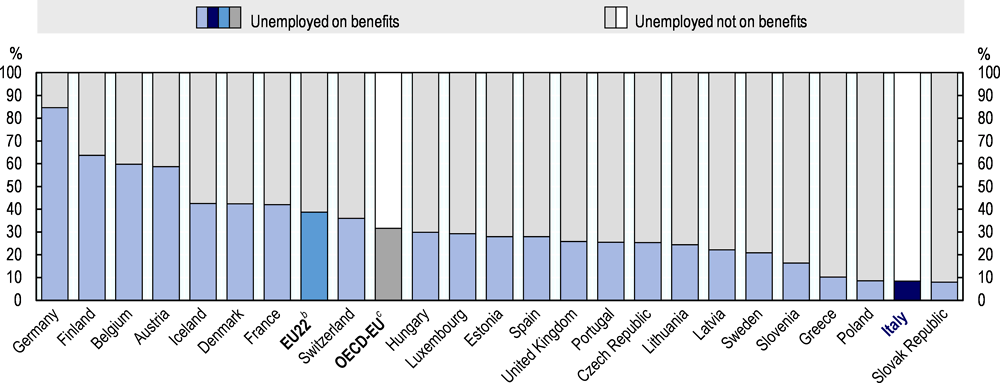

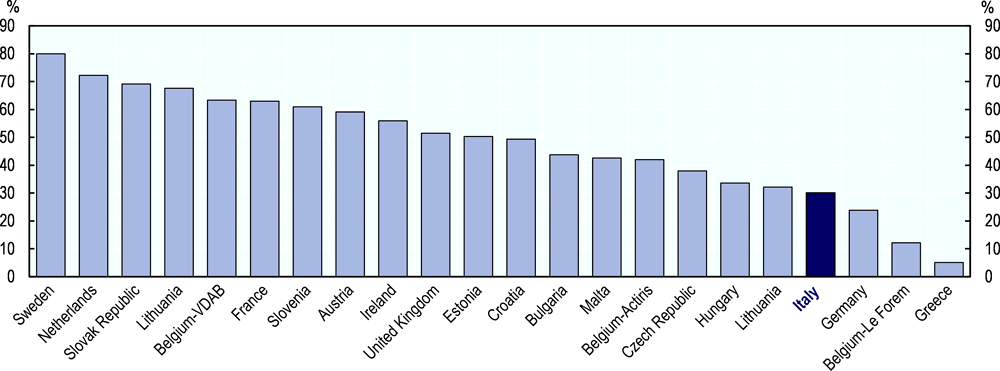

The expenditure on passive labour market policies has been relatively high in Italy compared to other OECD countries (1.29% of GDP in Italy and 0.79% on average in OECD countries in 2015, see Figure 1.13 in Chapter 1). During 2012-15, both the unemployment rate and the spending on passive labour market policies relative to GDP in Italy were 60% to 70% higher than the respective average figures for the OECD. Yet, only 8.5% of unemployed people received unemployment benefits in Italy in 2016, which is one of the lowest shares in the European Union, second lowest after the Slovak Republic (see

Figure 2.3). A large share of expenditures are dedicated to wage supplementation schemes for workers on reduced working hours. This is one of the main reasons why the share of benefit recipients among the unemployed is so low even though expenditures on passive labour market measures are high in comparison with those in other OECD countries.

Figure 2.3. Unemployed by benefit receipt in the European Union

Note: EU: European Union. PES: Public employment service. Data refer to all unemployed people regardless of being registered or not at the PES, by whether they receive benefits or assistance.

a. Data refer to 2013 for Germany.

b. Unweighted average of the 22 EU countries in the figure.

c. Unweighted average of the EU countries in the figure which are OECD member countries, excluding Lithuania.

Source: European Union Labour Force Survey (EULFS) Database, http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/lfs/data/database.

Wage supplementation schemes dominate passive labour market policies

Italy’s passive labour market policies have historically relied on wage supplementation schemes (Cassa Integrazione Guadagni Ordinaria – CIGO and Cassa Integrazione Guadagni Straordinaria – CIGS). These benefits are paid for workers on reduced working hours (including in the cases when working hours are reduced to zero, but the working contract is formally maintained). They were introduced in the 1950s and 1960s to help firms cope with temporary difficulties or lengthier processes of restructuring. Nevertheless, over time these kinds of benefits were used increasingly to cover permanent redundancies. Since they are not universal, one of the consequences of the massive reliance on these schemes has been a high level of differentiation in the coverage of workers, mainly by contract type and seniority, firm size and sector of activity as well as by the discretion of the public authority who can decide the access to the funds.2 These schemes are very generous as they replace up to 80% of the wage and require a contribution from employers which does not exceed 8% of the benefit. These generous conditions make them more popular than the unemployment benefit schemes for both employers and employees. However, they limit the potential for mobility across firms and reallocation to more productive jobs, they leave room for opportunistic behaviour due to the lack of job‑search conditionality and they cover only some workers while many others lack effective protection (Calligaris et al., 2016[24]).

These schemes are used as substitutes for the unemployment benefit system, but only for the workers in specific sectors. The coverage of sectors was extended in the period following the crisis by applying the “social shock absorbers in derogation” (ammortizzatori sociali in deroga – AD) which relaxed the entitlement criteria for both wage supplementation schemes and for the occupational mobility allowance (Mobilità in deroga, which serves in essence the same purpose as CIGO and CIGS).3 These new criteria allowed regional authorities to include firms that were previously not covered because of their sector or size as well as employees on non-standard contracts. Newly admitted firms accessed the system without making any contributions, as the cost was covered by the state budget. At the same time, the maximum period for wage supplementation was extended indefinitely.4 The government earmarked almost EUR 12 billion between 2009 and 2015 for this purpose (8.1 billion for wage supplementation schemes and 3.5 billion for the mobility allowance, partially co-financed by the regions and the European Social Fund).

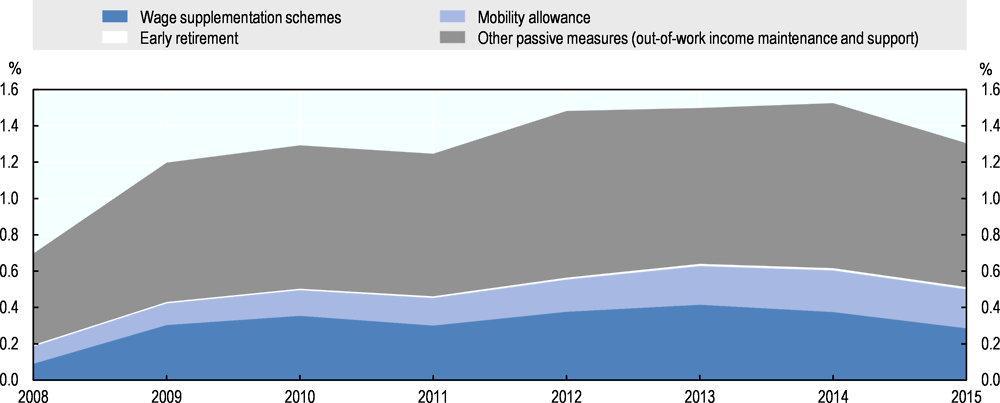

The share of wage supplementation schemes and occupational mobility allowance has formed around 40% of the total expenditure of PLMPs in Italy in the past years (Figure 2.4). The increase during the crisis was due to the introduction of AD.

Figure 2.4. Almost half the expenditures on passive labour market policies go to wage supplementation and mobility allowance

Note: GDP: Gross domestic product.

Source: OECD/Eurostat Labour Market Programme Database, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/data-00312-en.

Table 2.1 compares CIGO and CIGS with the two general unemployment benefit schemes existing before the Fornero reform in 2012 – the full requirements unemployment benefit (Indennità di disoccupazione a requisiti pieni) and the reduced requirements unemployment benefit (Indennità di disoccupazione a requisiti ridotti).5 It shows that the wage supplementation schemes used to be more generous and had lighter requirements than the unemployment benefits that existed at the time. For employers, they represented a tool for internal flexibility in response to the strict employment protection legislation (Sacchi, Pancaldi and Arisi, 2011[25]).

Table 2.1. Wage supplementation schemes and general unemployment benefit schemes before the Fornero reform in 2012

|

Full requirements unemployment benefit |

Reduced requirements unemployment benefit |

Ordinary supplementation fund |

Emergency supplementation fund |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Entitlement criteria |

52 weeks of contribution in the last 2 years. |

78 working days in the year the benefit is claimed for. |

Dependent workers of firms authorised to access the fund (workers on non‑standard contracts excluded). |

Dependent workers of firms authorised to access the fund (workers on non‑standard contracts excluded) with at least 90 days of contributions. |

|

Duration |

8 months (12 for over 50‑year‑olds). |

Number of days in the reference year, with a maximum of 180. |

3 months in a row, extendable up to 12 months in 2 years. |

Up to 48 months for restructuring (24 + 12 + 12). |

Changes in the system of passive labour market policies

The Jobs Act intends to introduce three main changes in the system of passive labour market policies: i) reduce the reliance on wage supplementation schemes, ii) harmonise the unemployment benefit system into one universal insurance scheme linking the duration of benefits with the previous working history, and iii) strengthen the link between active measures and benefit recipiency by strengthening the principle of activation conditionality.

Regarding the wage supplementation schemes, the Jobs Act brought about a harmonisation of CIGO and CIGS and reduced the ground for redundancies, extended their coverage and linked the schemes better with ALMPs. The coverage of contract types was extended to all employees and the length was reduced to a maximum of 24 months over a moving five‑year period (cumulated length of CIGO and CIGS). The cost for firms was made more responsive to the actual use of the schemes by making their contribution proportional to the extent of the CIGO and CIGS used.6 Bureaucratic procedures were simplified by smoothing the access procedure to the funds as the wage supplements are now granted directly by INPS and the local committees were abolished.7 Concerning the link with ALMPs, workers whose working hours are reduced by more than 50% are required to sign the “personalised service pact” with employment services (similarly to the recipients of unemployment benefits) in order to help them to be reintegrated into the labour market.

Concerning the unemployment benefit schemes, the Jobs Act created one single main insurance scheme called “New Social Insurance for Employment” (Nuova Assicurazione Sociale per l’Impiego, NASPI) and a smaller one dedicated to dependent self‑employed workers (Disoccupazione collaborator, DIS-COLL). NASPI was introduced in March 2015 replacing the “Social Insurance for Employment” (Assicurazione Sociale per l’Impiego – ASPI) and the “Mini-Social Insurance for Employment” (mini-ASPI) which had been introduced with the Fornero reform in 2012.

The Jobs Act harmonised the entitlement and eligibility criteria and extended both the coverage and the duration of the benefits (see Table 2.2 for a comparison of the eligibility conditions and benefit characteristics of NASPI with ASPI and mini-ASPI). First of all, contrary to the previous system, NASPI applies also to workers whose contract has been terminated consensually or by resignation. An increase in the coverage rate of unemployment benefits has been achieved also by loosening the entitlement criteria.

Table 2.2. Unemployment benefit schemes after the Fornero reform (ASPI and mini-ASPI) and after the Jobs Act (NASPI)

|

New Social Insurance for Employment (NASPI) |

Mini‑ASPI |

Social Insurance for Employment (ASPI) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

|

Entitlement criteria |

13 weeks of contributions in the 4 years before the beginning of the period of unemployment, and at least 30 working days in the 12 months preceding the same period. |

First contribution payment at least 2 years before the beginning of the period of unemployment. 12 months of contributions in the 2 years preceding the same period. |

13 weeks of contributions during the 12 months preceding the beginning of the period of unemployment. |

|

Duration |

Half the number of weeks for which contributions were paid in the 4 years before the start of unemployment. Maximum duration was 24 months in 2015 and 2016. |

From 10 to 16 months depending on age. |

Half of the number of weeks for which contributions were paid over the 12 months preceding the beginning of unemployment. |

|

Amount |

75% of the first EUR 1 195 of wage. 25% of wage over EUR 1 195. The maximum allowance is EUR 1 300. The benefit decreases by 3% each month starting from the fourth month. |

75% of the first EUR 1 195 of wage. 25% of wage over EUR 1 195. The maximum allowance in 2015 was EUR 1 167. The benefit decreases by 15% after the first 6 months and by a further 15% after 12 months. |

75% of the first EUR 1 195 of wage. 25% of wage over EUR 1 195 The maximum allowance in 2015 was EUR 1 167. |

Note: ASPI: Assicurazione Sociale per l’Impiego. NASPI: Nuova Assicurazione Sociale per l’Impiego.

Table 2.3 shows the number of unemployed people entitled to NASPI in 2015 and 2016 and compares this with the situation in which they would have filled requirements to access the previous ASPI/mini-ASPI system. In both years, the number of benefit recipients would have been almost 6% lower. The new system appears to benefit particularly the workers on temporary contracts, which is possibly a result of the more relaxed entitlement criteria. It means that the new scheme might enable an easier accumulation of working records, as career breaks probably have a smaller impact on the benefit entitlement.

Table 2.3. Extension in coverage of NASPI compared with previous ASPI/mini‑ASPI system

|

2015 |

2016 |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Total number of recipients |

Number of recipients who would have not been entitled to ASPI/mini‑ASPI |

Percentage of persons not entitled under the old system |

Total number of recipients |

Number of recipients who would have not been entitled to ASPI/mini-ASPI |

Percentage of persons not entitled under the old system |

||

|

Total |

1 300 385 |

73 616 |

5.7 |

1 579 311 |

91 800 |

5.8 |

|

|

Open‑ended contracts |

429 650 |

15 007 |

3.5 |

581 998 |

19 339 |

3.3 |

|

|

Fixed‑terms contracts |

625 486 |

38 061 |

6.1 |

726 631 |

50 553 |

7.0 |

|

Note: ASPI: Assicurazione Sociale per l’Impiego (unemployment benefit). NASPI: Nuova Assicurazione Sociale per l’Impiego (unemployment benefit).

Source: INPS (2017), XVI Rapporto annuale, https://www.inps.it/nuovoportaleinps/default.aspx?sPathID=%3b0%3b46396%3b50544%3b&lastMenu=50544&iMenu=12&iNodo=50544&p4=2.

The maximum duration of NASPI is longer than of ASPI. NASPI is granted for a number of weeks equal to half the weeks of insurance contribution in the last four years,8 while this window was restricted to one year for ASPI. The maximum potential period of NASPI is now in total a few months longer than it was for ASPI (see Table 2.4 for a full comparison of the two schemes). The increase is particularly high for open-ended contracts due to the higher number of weeks of contributions in the period before unemployment that is used to establish benefit duration. This means that people working more continuously (with less career breaks) might benefit more from the new system.

Table 2.4. Extension in duration of NASPI compared with previous ASPI/mini-ASPI system

|

2015 |

2016 |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Total number of benefits granted |

Average duration of NASPI (months) |

Average duration of ASPI (months) |

Total number of benefits granted |

Average duration of NASPI (months) |

Average duration of ASPI (months) |

||

|

Total |

816 574 |

13.8 |

10.9 |

966 716 |

13.8 |

12.8 |

|

|

Open-ended contracts |

319 410 |

17.7 |

11.3 |

433 603 |

17.5 |

13.1 |

|

|

Fixed-terms contracts |

383 480 |

11.8 |

10.7 |

405 398 |

11.4 |

12.5 |

|

Note: ASPI: Assicurazione Sociale per l’Impiego (unemployment benefit). NASPI: Nuova Assicurazione Sociale per l’Impiego (unemployment benefit).

Source: INPS (2017), XVI Rapporto annuale, https://www.inps.it/nuovoportaleinps/default.aspx?sPathID=%3b0%3b46396%3b50544%3b&lastMenu=50544&iMenu=12&iNodo=50544&p4=2.

The amount of the benefit has not changed. NASPI grants 75% of the monthly “standardised” wage9 for those who earn up to a threshold of EUR 1 195 per month.10 For wages above the threshold, the benefit is equal to 75% of EUR 1 195 plus 25% of the difference between the monthly wage and the threshold itself, limiting the maximum benefit at EUR 1 300.11

The smaller-scale unemployment benefit scheme dedicated to dependent self-employed workers (Disoccupazione collaboratore – DIS-COLL)12 requires a minimum of three months of contributions, from the beginning of the year preceding unemployment. The duration and amount of the benefit are the same as for NASPI, with the only difference that the maximum duration cannot exceed six months. It represents the first protection introduced for an emblematic category in the Italian dual labour market, the dependent self‑employed workers. These are mainly so-called collaborators (collaborazione a progetto), whose share in the Italian labour market has dramatically increased after the liberalisation of this kind of contracts by the “Biagi reform” in 2003.

Another important novelty in the Jobs Act was the introduction of the Assegno Sociale di Disoccupazione (ASDI) that relies on general taxation. This benefit is targeted to those unemployed who do not fulfil the minimum entitlement criteria for NASPI or who have exhausted its maximum period, but who continue to be unemployed and also in poverty.13 In 2017, it was replaced by the “Inclusion Income” Reddito di Inclusione (REI),14 which extended both the benefit coverage and duration. REI was originally designed with entitlement criteria related both to the family composition15 and the household’s income16 and then changed with the 2018 budget removing family requirements from 1 June 2018. All persons in the household have to agree to a “personalised project”, involving not only employment services but also social assistance services. Very importantly, this benefit is conditioned on active job search, but also on other commitments, such as healthcare and attendance of school for minors, in order to help families to overcome poverty and address social exclusion.

For the new benefit schemes to serve the purpose of providing income support during job search, activation conditionality is aimed at concerning all the benefits introduced with the Jobs Act. Activation conditionality (obligation to look for a job, accept suitable job offers, etc.) applied on unemployment benefits is a common and crucial feature of developed systems of labour market policies among OECD countries (OECD, 2013[17]), (OECD, 2015[26]). In addition, in the intention of the Italian policy-makers, the introduction of the new means-tested unemployment benefit (REI) would enable the Italian income support system to conform with the most widespread model in the Western Europe, i.e. the protection against unemployment is organised on two pillars, unemployment insurance and unemployment assistance (Sacchi, 2014[27]).

The new Italian government, which came to power in 2018, aims to reform REI to transform it into a universal income benefit, i.e. a universal measure against poverty. Some changes were implemented already in June 2018 (abolishing the requirements on family situation) and further and more extensive changes are foreseen for 2019. The budget law for 2019 allocates a substantial additional funding for this reformed benefit indicating an increase in its generosity. However, the exact details of the new scheme are not fixed yet as of autumn 2018. If the new scheme will be indeed more generous, the activation conditionality becomes even more crucial for the benefit scheme to have positive effects on the employment rate.

2.3. Strengthening the system of employment services

The Jobs Act aims to strengthen activation policies through a restructuring of the system and the institutions responsible for the design and delivery of ALMPs and the creation of the National Agency for Active Labour Market Policies as the coordinator of the network of employment services. In addition, it strengthens the activation concept supported by modernising the IT infrastructure, updating the service models and introducing monitoring and transparency to the system. These changes have the potential to make the system of employment services more effective and efficient.

2.3.1. Restructuring the system and enhancing service quality

Although there have been many attempts to advance labour market flexibility and passive labour market policies in Italy during the past 30 years, the provision of active labour market policies has been lagging behind.

The previous reforms of employment services have shifted the responsibilities across different government levels, but the concept and content of active measures have remained nearly untouched. The reform of active measures within the Jobs Act brings about on the one hand yet another restructuring of the system, this time aiming at harmonisation and decreasing fragmentation. In addition to that, the Jobs Act targets the content and above all the quality of active labour market policies. First, it identifies general principles of active labour market policies and sets grounds for introducing minimum service standards across Italy. Second, it aims to increase the quality of employment services by enhancing the quasi-market for employment services and stimulating competition between the public and private providers (this issue is discussed more thoroughly also in Chapter 3 of this report). Third, activation conditionality on benefit recipients is enforced to shift the focus from passive measures to active measures in the system.

Restructuring the system: some fragmentation will likely remain

The initial intention of the Jobs Act was to fundamentally restructure the system of employment services to increase the effectiveness of active labour market policies across Italy by centralising the competencies for active measures from the provincial level to the national level. The newly created National Agency for Active Labour Market Policies (ANPAL) was tasked with setting the objectives and strategies for the employment services in Italy. However, this step of centralised competencies required a constitutional reform preceded by a referendum.17 Due to the negative outcome of the referendum in December 2016 it was not possible to centralise the responsibilities to the national level, but only consolidate the competencies to the regional level. This process had started already in 2014, but is not completed yet. One of the difficulties in this process has been the negotiations with the trade unions of the staff in the local employment offices that are not welcoming the new regional approaches.

Although this partial transfer of responsibilities was not the desired outcome, it was a step forward from the highly fragmented system, in which more than hundred provinces were implementing the employment services, to a system of 19 regions and 2 autonomous provinces.

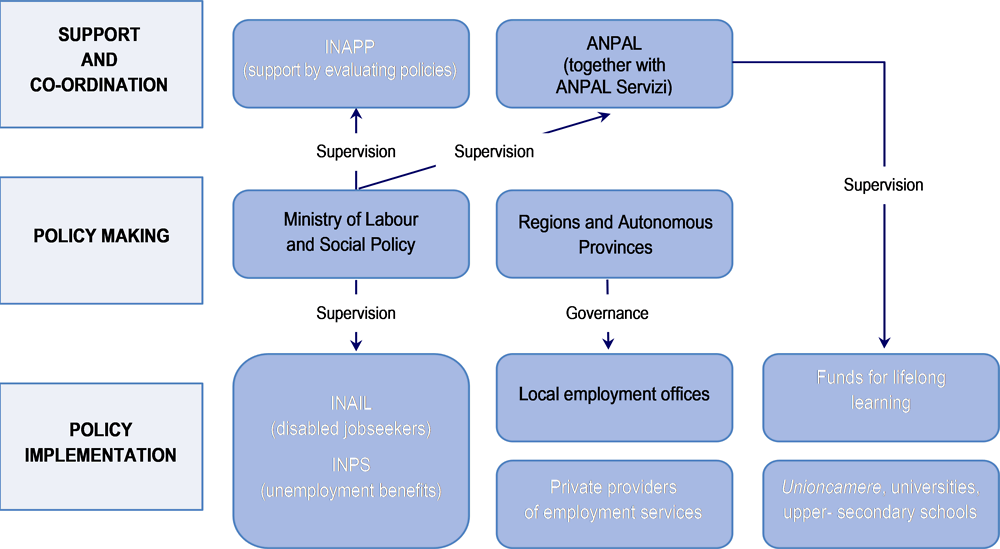

Additionally, the roles and relationships between the stakeholders had to be redefined compared with the initial model. ANPAL is now the coordinator of the activities of the relevant stakeholders involved in the delivery of employment services.

The Jobs Act established a network of employment services with the task to introduce actions and services aimed at improving the efficiency of the labour market for both employers in terms of satisfying skill needs and for jobseekers by providing support for labour market integration. The network is composed of a number of actors:

The National Agency for Active Labour Market Policies (ANPAL), formerly the General Directorate for Active Policies, Employment and Training Services of the Ministry of Labour and Social Policies. ANPAL is tasked to be the coordinator of the network of employment services. Monitored and steered by the Ministry of Labour and Social Policies.

The regional structures for active labour market policies. The regions have the competencies to provide the employment services thorough their local employment offices (Centri per l’Impiego, CPIs). Previously, the provinces were in charge of the local employment offices. About half of the regions (nine of them) have a regional agency for employment services to manage the local employment offices, in others regional administration manages the employment offices directly.

The National Institute for Social Protection (INPS) being in charge of employment subsidies and income support measures (i.e. also passive labour market measures), a national centralised organisation (no change due to the reform). Monitored and steered by the Ministry of Labour and Social Policies.

The Institute for Insurance against Accidents at Work (INAIL) co‑operating with the system of public employment services regarding job integration of people with work-related disabilities (no change due to the reform). Monitored and steered by the Ministry of Labour and Social Policies.

Private (accredited) providers of employment services providing active measures alongside the public local employment offices. These service providers existed also before the reform, though the reform aims at developing the market for private service providers further.

Inter-professional funds for lifelong training and bilateral funds i.e. funds for training measures for which the task of supervision is given by the reform to ANPAL.

The Institute for the Development of Workers’ Professional Training (ISFOL) changed by the same decree to the National Institute for Public Policy Analysis (INAPP). Some staff of ISFOL was transferred to ANPAL as part of the reform. The main task of INAPP is to study, monitor and evaluate public policies, including labour market policies. Monitored and steered by the Ministry of Labour and Social Policies.

Italia Lavoro S.p.A. changed to ANPAL Servizi S.p.A. and transformed to an in‑house entity of ANPAL. While Italia Lavoro used to be a joint-stock company owned by the Ministry of Economy and Finance mainly to manage locally the provision of employment services from ESF funding, the transformed ANPAL Servizi (now a joint-stock company owned by ANPAL) should assist and support ANPAL in its activities. As ANPAL Servizi contrary to ANPAL has employees also in the regional level, it assists also the regions and CPIs locally (though considering the guidelines from ANPAL).

The Union of the Chambers of Commerce, Industry, Crafts and Agriculture called Unioncamere) regarding an input for trainings (anticipating skill needs), universities and upper secondary schools regarding training provision.

All of these organisations existed in some form also before the reform. Thus, the creation of this network was a slight rearrangement of responsibilities between the organisations rather than creating a new set-up of employment services. For example, prior to the reform, ANPAL existed as a directorate in the Ministry of Labour and Social Policies and had somewhat similar responsibilities as after the reform. ANPAL is today still steered and monitored by the Ministry of Labour, similarly to several other organisations in the network of employment services. ANPAL was created transferring some staff from the Ministry and from the ISFOL/INAPP together with the respective funds aiming at no additional burden to be generated to the public sector in terms of costs.

All stakeholders of employment services in Italy are depicted in Figure 2.5 by their function, highlighting the core actors of public employment services in black font. Although ANPAL coordinates the network of employment services,18 it is not responsible for active labour market policies. The Ministry of Labour and Social Policies together with the Regions and Autonomous Provinces (hereinafter referred to as the Regions) identify the relevant strategies, objectives and priorities. Specifically, the Ministry of Labour and Social Policies acting together with the State-Regions Conference is responsible for fixing three-year strategies and yearly objectives regarding active labour market policies and for defining minimum service levels throughout the country. The Ministry and the Regions sign yearly framework agreements regulating the relations and obligations concerning the management of employment services and active labour market policies, the activities that are outsourced from the private accredited bodies and the duties entrusted to ANPAL.19 However, ANPAL coordinates the preparation process for the different strategic documents and thus can have an influence over activation policies. ANPAL established for that a Committee of Active Labour Market Policies as one of its first steps. This committee involves all regional directors, is chaired by the general director of ANPAL and meets about ten times a year to discuss strategic issues regarding employment services.

Figure 2.5. The system of employment services in Italy by function

Note: Column 1 refers to the function of actors, Columns 2 to 4 to actors. The Ministry of Labour and Social Policy is not a member of the network of employment services.

Active labour market policies are delivered by the local employment offices (CPIs) or outsourced to private (accredited) providers for employment services. After the full implementation of the reform, the CPIs are steered by the Regions. Although the consolidation of the competencies from the provinces to the regional level began already in 2014, this process was still ongoing as of June 2018 (only 10 out of 19 regions had completed the consolidation process).20 In addition, the financial resources were not moved to the regional level alongside the responsibilities, which hinders the consolidation process. As an (intermediary) solution, the funding of the CPIs was shared between the Ministry and the Regions and regulated by the yearly framework agreements in 2016 and 2017. The budget law for 2018 established a permanent transfer from the State budget to the Regions.

Due to the consolidation of responsibilities, the fragmentation of the system has decreased as there are 21 Regions implementing employment services instead of over a hundred different provinces. Yet, the number of partners in the system is still too high for a smooth and harmonious implementation of active policies. The fragmentation has caused delays in the progress of improvements in the system and is considered to be one of the main challenges by many stakeholders. The main actors in the system of employment services should co‑operate more to overcome the fragmentation of the system and make progress in implementing the Jobs Act.

The co‑operation is particularly low among the Regions as they do not see the clear benefits from the activities of ANPAL and from co‑operating with other Regions. The wide-spread belief that the regional labour markets are very different leaves little scope for learning from each other and co‑operating. However, in reality, the Regions share many similar features and challenges and the regional labour markets are indeed interconnected (see for example ISTAT (2014[28]) and Franconi et al. (2017[29])).

The benchlearning initiative of the EU PES Network has demonstrated the benefits of co‑operation and sharing of best practices despite important differences in the labour market situation and business models among the public employment services in the EU. In that context, a method has been developed to monitor performance of employment services, detect best practices and mutually learn good practices from each other and for which the feedback through the satisfaction surveys has been very positive by the public employment services (see Box 2.3 for more details). Spain, a country with a decentralised system of employment services and relatively high regional labour market disparities (OECD, 2017[10]), has successfully adapted the same methodology to apply it in its regional employment services and encourage thus mutual learning and continuous improvement. In Italy, this approach could be managed and supported by ANPAL to promote co‑operation between the Regions.

Box 2.3. Benchlearning initiative in the EU PES Network

The Decision of the European Parliament and Council on enhanced co‑operation between public employment services in 2014 established a network of PES in the European Union and set a method called “benchlearning” as one form of co‑operation to integrate benchmarking and mutual learning activities to improve sharing of best practices. Benchlearning is a systematic, indicator-based learning method supporting PES to improve their performance.

Benchlearning involves two exercises – benchmarking and mutual learning. Benchmarking consists of quantitative benchmarking of PES performance and qualitative benchmarking of organisational arrangements. This double benchmarking method enables to identify relationships between PES organisational arrangements and performance while controlling for institutional and economic context. An econometric modelling exercise is conducted to identify the “true enablers” of PES performance.

Quantitative benchmarking involves comparing quantitative performance indicators related to transitions of registered unemployed persons to employment, filling of vacancies and satisfaction of employers and jobseekers with PES. For this purpose, data is gathered in a harmonised methodology from PES registers, aiming at comparable data regardless of different institutional contexts.

Qualitative benchmarking assess organisational arrangements in seven areas: i) strategic performance management; ii) design of operational processes; iii) sustainable activation and management of transitions; iv) relations to employers; v) evidence‑based design and implementation of PES services; vi) effective management of partnerships with stakeholders; vii) allocation of PES resources. First, the PES conducts the evaluation of its organisational arrangements as a self-assessment, and second a team of external experts including from peer PES carry out an assessment. The assessment follows a Common Assessment Framework (CAF) model adapted to PES, which in turn is the Excellence Model of the European Foundation for Quality Management (EFQM) adapted to public sector organisations. The organisational arrangements are assessed following a plan-do-check-act cycle. As an output of qualitative assessment, the PES receives a report providing suggestions and recommendations for peer PES as potential exchange partners.

Mutual learning builds on the evidence from quantitative and qualitative benchmarking results. Benchmarking exercises identify learning needs (topics), potential thematic clusters and best practices that can be shared. Mutual learning takes place for example in thematic review workshops, PES Network seminars, conferences as well as smaller‑scale formats such as study visits, smaller working groups or mutual assistance projects for PES that need more intense support. In addition, the key outputs of the mutual learning exercise such as the fiches of best practices, analytical papers and toolkits, are disseminated in the PES Knowledge Centre also externally. 21

The main factor of success of this methodology in the EU PES Network has been that the participants do not perceive this exercise as a contest of performance, but have a strong motivation to learn from others and share their own good practices. Thus, they contribute to open and truthful self-assessments and external assessments and exhibit a strong will to improve.

A similar exercise could be applied in Italy to encourage a structured and evidence‑based sharing of good practices between the Regions. As gathering quantitative data depends on the IT developments and might still take some time, as a first step the qualitative benchmarking could be implemented to detect potential good practices and to build mutual learning on. The exercise needs coordination [organising practical arrangements concerning qualitative assessments and mutual learning events, potentially involving external partners to support the exercise, disseminating the good practices detected (potentially also through a repository), collect and process data, etc.], which should be done by ANPAL.

Source: Fertig, M. and N. Ziminiene (2017[30]), PES Network Benchlearning Manual, EC, Brussels, http://dx.doi.org/10.2767/254654; European Parliament and the Council (2014[31]), “Decision No 573/2014/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council”, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=uriserv%3AOJ.L_.2014.159.01.0032.01.ENG.

Setting minimum standards

The Jobs Act aims at harmonising the concept of employment services and setting minimum quality standards in the otherwise diverse regionalised system. The Decree 150/2015 implementing the Jobs Act defines the basic concepts such as the status of unemployment and it identifies general principles of active labour market policies.22 Given the institutional setting in Italy and the decentralised responsibilities for the design and implementation of active measures, the set of measures varies greatly across Italy. The Jobs Act outlines the minimum set of active labour market policies that has to be available for all the jobseekers across Italy. However, the Regions can (and they do) provide additional measures to this minimum set of measures.

In addition, the Jobs Act calls for the establishment of minimum quality standards for the outlined active measures with the help of ANPAL. The agreement for these minimum standards was reached with the Regions the first time at the end of 2017 and these are fixed in the Triennial Strategy for the Action on Active Policies. The concluded agreement has been a step forward in guaranteeing access to employment services for citizens across Italy. In principle, ANPAL has the right to manage labour market programmes directly in case the essential service standards are not guaranteed and hence intervene in the management of CPIs in case of weak performance. However, monitoring of the implementation of these minimum quality levels has remained yet problematic. ANPAL did conduct a monitoring survey among the local employment offices in 2016‑17, but this did not follow (yet) precisely the minimum service standards agreed upon and the monitoring framework itself did not follow any agreed framework. Nevertheless, these monitoring results indicate that while basic activities of the minimum service standards tend to be in place in most of the CPIs, many activities are still problematic across Italy (ANPAL, 2018[32]). The preliminary performance management system (including the management information system) has to be developed further to accommodate monitoring of the quality of services and actions have to be agreed when the service quality is below the minimum agreed level.23

Enhancing quasi-market

A true novelty in the law 150/2015 regarding the set of active measures is the provision of individual “reintegration vouchers” (“replacement vouchers”) which allows the jobseeker to decide which service provider to use for an intensive support service for job search. This legal provision aims at increasing the role of private providers of employment services to complement the limited resources of the public providers as well as stimulating competition between the public and private providers to enhance service quality. The value of the reintegration voucher depends on the employability profile of the jobseeker (the harder to place jobseekers needing more intensive support) and the payments depend on the employment results achieved, thus aiming at performance, but avoiding creaming. The development of the operational scheme and monitoring methods of the reintegration vouchers have been some of the tasks delivered by ANPAL during the first year of its operation. The actors in the network of employment services share the view that the complementarity from the private service providers is welcome as the resources in the public system are insufficient. Yet, the provision of reintegration voucher during its piloting year in 2017 has not been viewed as a success as the take-up has been lower than expected, the employment outcomes have been weak [the evaluation results for the experimental phase of the voucher by ANPAL show no statistically significant improvement in employment outcomes due to the vouchers (ANPAL, forthcoming[33])] and the information on job quality has been largely missing.

Linking passive with active measures: enforcing conditionality

The link between unemployment benefit recipiency and active job-search requirement (job‑search conditionality) has traditionally been weak in the Italian system. Until the Jobs Act the job-search conditionality was regulated very rigidly in the law, establishing a complete loss of benefit in any lack of compliance with commitments agreed with employment services. Despite this strict definition, conditionality was never applied in practice. The Decree 150 of September 2015 strengthened the principle of conditionality through two main changes. First, there is a more gradual application of sanctions in case jobseekers are not complying with commitments agreed. Second, it establishes mechanisms to implement conditionality by relaunching setting mutual obligations for employment offices and jobseekers and by incentivising employment offices to apply sanctions.

With the aim to increase the activity of jobseekers and make benefit receipt conditional on job-search activity on the one hand and to increase the personalised support for the jobseekers on the other, “an individual service pact” (“patto di servizio personalizzato”), is introduced by the law. After registration through an online system as unemployed, a jobseeker has to contact a local employment office within 30 days to validate his/her status as unemployed. The local employment office has to propose an individual service pact within 60 days after registration. The service pact is in essence an individual action plan (or job integration agreement) used in some form by all of the public employment services in the European Union [see e.g. Wittenberg et al. (2016[34]) and Tubb (2012[35])].

The service pact lays down mutual obligations of the jobseeker and the employment office. The employment service commits to providing labour market services according to the individual needs of the jobseeker (e.g. job‑search counselling, training, reintegration voucher, unemployment benefit REI) and the jobseeker agrees to participate in these activities, take steps to find employment and accept suitable job offers. A failure to comply with the activation activities (no-show to an appointment in the employment office, failure to participate in an active measure or refusal of a suitable job offer) incurs sanctions on benefits ranging from the reduction to the termination of unemployment benefits (NASPI and DIS-COLL, REI), as well as the reduction or loss of income support measures (CIGO, CIGS, Solidarity Contract and Solidarity Funds). However, so far the service pact has not been applied in a homogenous way across Italy and not always covering all benefit recipients (involving for example only recipients of certain services such as the reintegration voucher).24 This is why ANPAL proposed a common form to be used for the service pact in May 2018 (see Chapter 3), which is however not binding for the employment offices to use.

Although the activation conditionality on benefits existed in the legislation already before the introduction of the Jobs Act, these principles were never implemented (Pinelli et al., 2017[1]). One of the reasons the conditionality has not been enforced in the past is the lack of IT infrastructure which would enable the employment services to communicate with INPS which is responsible for the benefit delivery to the unemployed. The Jobs Act specifies that the employment offices have to use the online system to communicate violations of activation activities by jobseekers to ANPAL and INPS which executes the resulting benefit adjustments. However, the integrated single IT system has not yet been completed, which makes any communication attempt rather burdensome.

In order to strengthen job-search conditionality, the Jobs Act foresees disciplinary and financial sanctions for the staff in employment offices failing to apply the sanctions on benefit recipients and rewards them in case of compliance. The Regions receive 50% of the benefits saved from applying sanctions which can be used as incentive tools for staff in local employment offices and the remaining 50% of benefit savings goes to the national fund for active labour market policies.

The biggest obstacle in the implementation of activation conditionality has been that the concept of a suitable job offer was not furnished and approved by the Ministry of Labour and Social Policies until July 2018. As such, the CPIs and operators were afraid to apply the activation conditionality due to the possible lawsuits as it would not have been possible for them to prove that the job offer was suitable.

The Ministerial decree from July 2018 defines suitable job offer through i) the match between the job offer and jobseeker regarding experience and skills (better match required when shorter unemployment duration), ii) geographical distance and commuting times (obligation to accept jobs up to 50 km distance when the unemployment duration is less than 12 months, but 80 km thereafter), iii) wage level in case of unemployment benefit recipients (wage should be 20% higher than benefit). Additionally, the job offer should be at least for three months, with at least 80% working time, provide at least the minimum wage required by the applicable collective agreement and be compatible with health limitations in case of a disabled jobseeker. The application of the suitable job offer is set to be dependent on the new IT system for providing employment services (an integrated single IT system of active labour market policies, see Subsection 2.3.3). The employment offices should receive data about the amount of unemployment benefit from INPS through the IT system to apply the income criterion. The matching of skills and experience depends on what is agreed in the service pact using the classifications for occupations and economic sectors from the new IT system. Thus, the decree postpones the application of criteria related to skill match until the full operation of the new IT system.

As a result, it is unlikely that the concept of suitable job offer will be applied as part of the activation conditionality before the new IT system is functional. In addition, even if drawing up service pacts incorporating jobseekers’ skills and suitable job offers will be supported by the new IT system, there would be difficulties for the operators to prove that the jobseeker refused the job offer. For the new IT system to support the application of activation conditionality in general, the activities agreed with the jobseeker and the activities of the jobseeker executed should be recorded in the IT system.

Clearly, it will be unavoidable that the application of conditionality will incur some appeals and lawsuits from jobseekers and thus the Regional authorities will have to devote some additional budget for legal costs. Yet, the additional legal costs will be marginal compared to the additional benefits that the application of activation conditionality brings if implemented properly. For example, in Estonia the reform of labour market policies took place in May 2009 incurring activation conditionality to be applied on registered jobseekers supported by fundamental changes throughout the business model, including building a modern IT infrastructure to support the changes. Although the eligibility criteria for unemployment benefits (e.g. conditions for availability for work, job‑search requirements, etc.) in Estonia are some of the strictest among the OECD countries (Langenbucher, 2015[36]), the share of appeals by jobseekers has been around 0.5% relative to the stock of registered unemployed and only a third of the appeals have been settled in favour of the jobseekers.25 Furthermore, activating jobseekers does not only occur costs, but also significant benefits. Activating jobseekers brings them quicker to the labour market and saves costs for the system of employment services. The meta-analysis of evaluations of early activation policies in 11 EU countries conducted by Csillag et al. (2018[37]) indicates that many early activation programs are effective and cost efficient (high positive benefit to cost ratio). This is particularly the case of intensified early support programmes involving individual job counselling (stronger evidence than for example for early group job counselling, early participation in training programs or early measures in case of collective dismissals).

To strengthen the enforcement of activation conditionality, the operators in the CPIs have to be trained to implement activation, making them aware of its objectives and build the know-how to use the appropriate tools. The difficult conditions in the labour market together with no prior experience in applying conditionality make the employment offices and their staff reluctant to impose sanctions on benefit recipients and share this information with INPS and ANPAL.

The monitoring and performance management system have to be developed further to accommodate activation activities. In the set of indicators agreed in the Triennial Strategy for the Action on Active Policies in December 2017, also indicators for the sanctions applied on benefit recipients and for the number of service pacts signed are included. However, no target has been set for these indicators yet26 nor is it clear how to gather the data for them.

Finally, a key factor which may limit the applicability of the activation conditionality is the very small number of vacancies mediated by the public employment services, which makes it harder for the operators in the CPIs to refer jobseekers to suitable jobs. Hence, shifting the system of employment services towards activation also requires putting a strategy for employer outreach in place (see Chapter 3 for more details on this matter). Given all these constraints and the limited progress so far, it is possible that the implementation of activation conditionality on benefit recipients will take a few years despite the additional new mechanisms provided by the Jobs Act.

If the proposal by the new government to transform the means-tested benefit REI into a universal benefit scheme will be implemented, the implementation of activation conditionality becomes even more critical as the number and potentially the level of benefit will be substantially increased. This scheme will reduce poverty and increase employment only in case benefit recipients are well supported by the employment services helping them to actively seek work and providing them with the necessary active measures to succeed in job search.

2.3.2. The crucial role of the National Agency for Active Labour Market Policies

Despite the change in ANPAL’s role following the outcome of the referendum, the organisation is still one of the key actors in the system of employment services and has a critical role to play. The main tasks of ANPAL are laid down in the decree implementing the Jobs Act regarding active labour market policies (decree 150/2015). Besides co‑ordinating the network of employment services, ANPAL is tasked with developing methodologies for different tools (reintegration voucher, jobseeker profiling, services for enterprises going through downsizing / services for displaced workers, training programmes), developing the support systems for service provision (integrated IT system, system of accrediting service providers, system of employment incentives) and contributing to the management of the related funds (ESF funding, EGF funding, funds for life-long learning). Very importantly, ANPAL is also setting the (minimum) standards for providing employment services and monitoring and evaluating the service provision.

Thus, the decree provides ANPAL with many different responsibilities which are similar in nature to the ones that the respective previous directorate of the Ministry of Labour and Social Policies used to have. Despite that, the law does not provide ANPAL with a main objective, the raison d’être. In reality, of course, ANPAL has an important main role to fill in coordinating the network of employment services and supporting the Regions to reform the system of employment services.

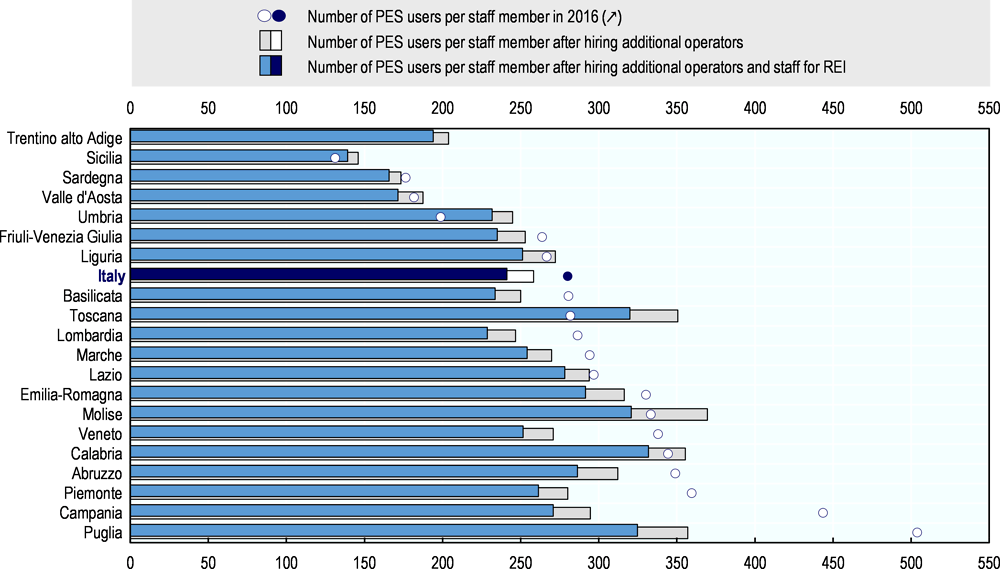

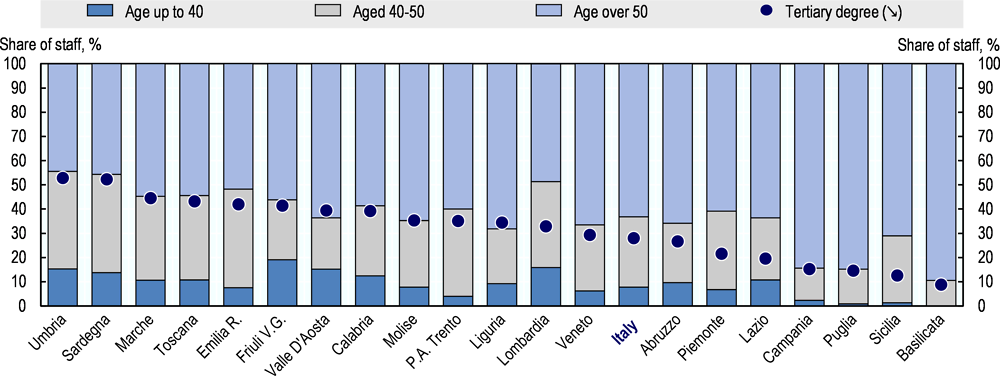

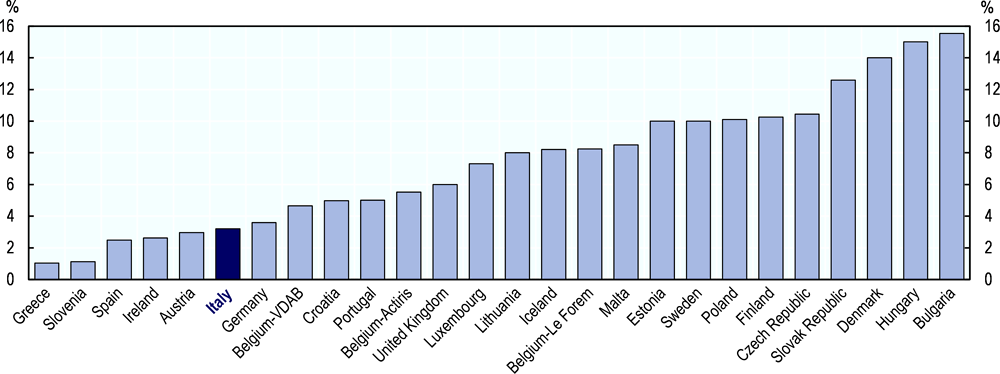

The statute of ANPAL (a presidential decree effective from June 2016) declares that ANPAL performs the functions and tasks assigned to it by the Decree 150 from 2015 in order to promote the effectiveness of the rights to work, training and professional development and the right of every individual to access free placement services, through interventions and services aimed at improving efficiency of the labour market.