This chapter studies the extent of FDI-SME diffusion in Portugal based on the conceptual framework introduced in Chapter 1. It examines where Portugal stands in the core channels of FDI-SME diffusion – value chain relationships (buy/supply linkages and strategic partnerships), labour mobility and skills effects, competition and imitation effects – relative to peers in the OECD and European Union and across economic activities.

Strengthening FDI and SME Linkages in Portugal

3. FDI diffusion at play for Portuguese SMEs

Abstract

3.1. Summary of strengths, challenges and opportunities

The diagnostic assessment of key diffusion channels through which FDI spillovers on Portuguese SMEs can take place reveals a number of strengths and points to challenges and opportunities (Table 3.1). The subsequent chapters (Chapters 4-6) pick up on these challenges and opportunities, identifying policy actions to address them.

Table 3.1. Strengths and challenges/opportunities across FDI-SME diffusion channels in Portugal

|

Strengths |

Challenges and opportunities |

|

|---|---|---|

|

Value chain linkages |

|

|

|

Strategic partnerships |

|

|

|

Labour mobility and skills effects |

|

|

|

Competition and imitation effects |

|

|

Note: See Chapter 2, Table 2.1, clarifying sectoral groupings (i.e. lower and higher technology manufacturing and lower and higher technology services) used in this table. This report primarily uses Ireland, Czech Republic, Slovak Republic, and sometimes Belgium, Hungary and Lithuania, as comparators/peers. They were chosen based on their economic size, outward orientation driven by foreign investors and EU membership.

3.2. Value chain relationships between foreign investors and SMEs

Domestic Portuguese firms may benefit from the presence of affiliates of foreign MNEs through buy and sell linkages. Domestic backward linkages are formed when foreign affiliates source intermediate inputs from locally established companies. Foreign affiliates can also sell intermediates to local companies. These linkages are referred to as domestic forward linkages. This section benchmarks domestic backward and forward linkages of foreign affiliates in Portugal against linkages observed in some of its peers in the OECD.1

Foreign affiliates source more extensively from domestic firms in Portugal compared to affiliates in some comparator economies

Domestic backward linkages of foreign affiliates help domestic companies extend their market for selling and raise the quality and competitiveness of their outputs. They can also generate knowledge spillovers when MNEs require better-quality inputs from local suppliers and are therefore willing to share knowledge and technology with domestic companies to encourage their adoption of better practices (OECD, 2020[1]).

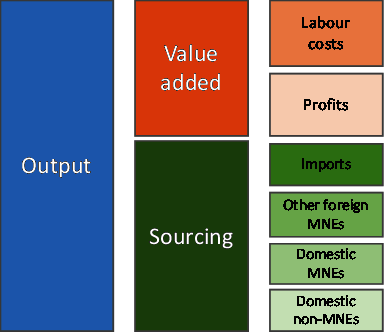

Backward linkages of foreign affiliates in Portugal can be analysed using the new OECD Analytical AMNE database. The data allow to compare the sourcing structure of foreign affiliates across OECD economies, including with respect to sourcing/linkages with domestically-owned firms (Box 3.1). In Portugal, purchased intermediates accounted for about 57% of foreign affiliates’ output in 2016 (where value added was responsible for the other 43% of total output). Foreign affiliates in Portugal source intermediate goods both from suppliers abroad (via imports) and firms located in Portugal. The share of inputs purchased internationally represented 38% of foreign firms’ total sourcing (Figure 3.1). The rest is local sourcing (62%) and can be further split into sourcing from other foreign affiliates established in Portugal (13%), domestically-owned multinational enterprises (domestic MNEs) (7%) and domestic non-MNEs (42%). The data do not allow to distinguish between domestic large firms and SMEs. However, based on existing knowledge on firms’ internationalisation, firms with FDI activity (i.e. MNEs) are often larger than those without. While this assumption may not hold for firms operating in the digital economy, it can be used for firms in more traditional sectors.

The share of local sourcing in total sourcing of foreign affiliates in Portugal is comparable with that of Korea, Finland, Switzerland or the Netherlands (Figure 3.1). Foreign affiliates source comparatively more from domestic non-MNEs (often SMEs) than foreign firms in many other OECD economies. Large economies such as France, the United States, the United Kingdom or Canada report a similar foreign firm sourcing pattern from domestic non-MNEs as Portugal. Foreign affiliates in many other small open economies – like Ireland or Hungary – depend relatively more on imported inputs and source less from domestic non-MNEs than foreign firms in Portugal do. This is a general pattern seen in such economies and typically relates to smaller markets for domestic input sourcing in these countries (less variety of intermediates might be available in smaller markets) as shown in a recent study on Ireland for example (OECD, 2020[2]).

Figure 3.1. Sourcing structure of foreign affiliates, by supplier type/origin, 2016

Note: Foreign MNEs = foreign affiliates of multinational enterprises; domestic MNEs = domestically owned firms with foreign affiliates abroad; domestic non-MNEs = domestically owned firms with no operations abroad. Trend = OECD average domestic sourcing share of foreign affiliates in total sourcing of foreign affiliates (sum of shares reflecting sourcing from other foreign affiliates, domestic MNEs and domestic non-MNEs).

Source: OECD based on the OECD Analytical AMNE database, 2019, https://www.oecd.org/sti/ind/analytical-AMNE-database.htm

On the other hand, sourcing of foreign affiliates from other foreign affiliates established in Portugal is somewhat less common in Portugal than in Ireland or the Czech Republic for example. The share is however still in the middle range compared to other OECD countries. Relatively low sourcing from other foreign firms indicate that clusters of foreign MNEs that buy from and sell to each are relatively more present in other small EU economies, while foreign firms’ motives for establishment could relate to other considerations such as labour and production costs, availability of skills and other assets (as shown in Chapter 2).

Local sourcing of foreign affiliates is more prevalent in services than in manufacturing in Portugal. In higher technology services (such as R&D, technical services and design) and lower technology services (such as logistics and sales), the share of local sourcing is around 80% of total input sourcing.2 This share has remained stable since the mid-2010s (Figure 3.2, Panel B). In lower technology manufacturing activities about half of all inputs are sourced in Portugal; this share has decreased over the past decade in higher technology manufacturing and stood at 40% in 2016. The patterns of local sourcing in services and manufacturing value chain functions in Portugal are comparable with those in other OECD and developing countries and thus reflect common sourcing practices across value chain functions across countries and not a specificity of Portugal (Cadestin et al., 2019[3]).

In absolute terms, local suppliers in higher technology manufacturing and lower technology services benefit most from demand of foreign affiliates. Firstly, foreign firms in Portugal are sourcing the largest amounts of inputs (both goods and services) in lower technology services; USD 7 billion in 2016 (Panel D). However, foreign manufacturers have sourced even more locally; if lower and higher technology manufacturing is put together, sourcing stood at USD 8.5 billion in 2016. Despite a very high share of local sourcing in higher technology services, their sourcing in absolute values at around USD 2 billion is much lower.

Domestic firms in Portugal source less domestically than their foreign peers. The analysis of the FDI sector in Portugal needs to be compared to the relatively larger sector of domestic firms, measured in terms of value added (Panel C). Across all value chain functions, foreign firms in Portugal are sourcing relatively more locally than domestic firms (Panel A). Domestic firms have reduced local sourcing over the past decade in all value chain functions. In higher technology services the local sourcing share of domestic firms was 70% in 2016, down from 80% in 2006; 60% in lower technology services, down from 70%; 35% in lower technology manufacturing, down from 55%; and 15% in higher technology manufacturing down from 35% over the same ten year period.

Box 3.1. Foreign affiliates’ output, value added and sourcing - concepts

To understand foreign firms’ (foreign affiliates’) buy linkages with domestically established firms, it is important to clarify how firm output, value added and sourcing related to each other. Foreign firms’ output can be split into value added and sourcing of intermediate inputs (see figure).

This section focuses on the extent to which foreign firms source intermediates directly from firms established in Portugal as opposed to sourcing of inputs from abroad through imports. In particular, the section looks at the extent of sourcing from domestic firms, i.e. Portuguese domestically-owned firms. The domestic sourcing structure is therefore further split into sourcing from other foreign affiliates established in Portugal, domestic MNEs (i.e. Portuguese firms with establishments abroad, which are often – but not exclusively – larger firms) and domestic non-MNEs (i.e. Portuguese firms with no establishments abroad, which are often SMEs).

The section does not specifically focus on better understanding to what extent value added generated by foreign affiliates stays in Portugal or may be repatriated to home economies, which is also of key interest in the context of direct contributions of foreign firms have to host economy growth and development. Part of foreign affiliates’ value added is used to pay salaries of their (mostly local) employees and therefore ‘stays’ in the domestic economy. The remaining part, including earnings, may or may not leave the host economy. The latter is particularly important in the context of tax policy.

Source: OECD based on (Cadestin et al., 2019[3])

This shift in supply chain practices of domestic firms reflects increased integration in GVCs of domestic firms, which is also observed in many other OECD and EU economies over the past decade, and is often associated with a process of their technology upgrading (Cadestin et al., 2019[3]; OECD, 2020[2]; OECD-UNIDO, 2019[4]). Integration in global value chains, which typically includes importing higher quality and cost-effective goods and services, has enabled domestic firms, particularly SMEs, in OECD and partner economies to move up the value chain, improve productivity and increase their market for exporting (OECD, 2019[5]; OECD-UNIDO, 2019[4]; Farole and Winkler, 2014[6]; López González et al., 2019[7]). This finding can thus be considered as positive for two reasons: On the one hand, domestic firms in Portugal have enhanced their integration in GVCs over recent years and, on the other hand, foreign affiliates established in Portugal take extensive advantage of the local economy by sourcing from domestically owned firms.

Figure 3.2. Sourcing of domestic and foreign firms by sectoral groups in Portugal

Source: OECD based on the OECD Analytical AMNE database, 2019, https://www.oecd.org/sti/ind/analytical-AMNE-database.htm

Production of foreign affiliates feeds back into domestic value chains and more so than in some of peer countries

Domestic firms in Portugal benefit more from (quality) inputs produced locally by foreign affiliates than in some peers according to the OECD Analytical AMNE database (Figure 3.3). In Portugal, more than 60% of the production of foreign affiliates feeds back into domestic value chains: in 2016, 24% of foreign affiliates’ output was used as an input by domestic non-MNEs, 4% by domestic MNEs and 7% by other foreign affiliates in Portugal. Another 24% was sold in the domestic market for final consumption. Hence, foreign affiliates produce relatively more intermediates (35%) than final goods for the domestic market in Portugal. The 35% output share acquired by domestically operating firms as inputs into their production, corresponds to the OECD average (see trend line in the figure). A number of other small economies – like Belgium, Ireland and the Slovak Republic – benefit relatively less from the use of intermediates produced locally by foreign firms. Forward linkages between MNEs and local buyers often have a positive impact on local enterprise productivity mostly through the acquisition of better quality inputs which were not locally available before. In addition, many MNEs, especially in industrial sectors such as machinery, often offer training to their customers on the use of their products and provide information on international quality standards (Jindra, 2006[8]). They may also help set the standards for the industry, which in turn can help better diffuse innovation. Firms adopting those international standards can more easily integrate in markets abroad.

Given the relatively smaller size of the Portuguese economy and the focus of public policies on attracting export-intensive FDI during the post 2008 crisis recovery (see Chapter 5), a relatively higher share of the production of foreign affiliates in Portugal is destined to international markets compared to the OECD overall: 40% in Portugal versus 30% in the OECD (Figure 3.3, OECD average export share not reflected in figure). Some other small open OECD economies show similar export orientation of foreign affiliates (e.g. Poland or Austria), while a number of other small economies have yet higher shares of exports in total output of foreign affiliates, such as Ireland, Belgium, or the Slovak Republic. Due to larger domestic markets in OECD economies like Japan, United States or Germany, market seeking motives of foreign firms appear as relatively more important. In these economies, foreign affiliates export lower shares of output, i.e. around 20-30%.

Figure 3.3. Use of outputs of foreign affiliates, by buyer type/origin, 2016

Note: Foreign affiliates = foreign affiliates of MNEs; domestic MNEs = domestically owned firms with foreign affiliates abroad; domestic non-MNEs = domestically owned firms with no operations abroad. Trend line = OECD average use of foreign affiliates’ intermediates in domestic value chains (sum of shares reflecting acquisitions/use by other foreign affiliates, domestic MNEs and domestic non-MNEs).

Source: OECD based on the OECD Analytical AMNE database, 2019, https://www.oecd.org/sti/ind/analytical-AMNE-database.htm.

3.3. Strategic partnerships between foreign firms and SMEs in Portugal

The emergence of GVCs has brought new types of FDI-SME partnerships, especially in high-technology and knowledge-intensive industries, which are based on the transfer of technology and the development of cross-border R&D projects and thus contribute extensively to spillovers of FDI. These partnerships can take many forms, including joint ventures, licensing agreements, research collaborations, globalised business networks (i.e. membership-based business organisations, trade associations, stakeholder networks), and R&D and technology alliances.3 A study for Portugal produced during the post-2008 crisis recovery showed that SMEs involved in partnerships, cooperation and networking arrangements (with other SMEs, large companies, public institutions, higher education and research and development institutions, social partner organisations and professional organisations) deal better with restructuring and are more innovative than other firms (Pereira and Correia Leitão, 2013[9]). This sections provides some insights on strengths and opportunities related to strategic Partnerships in Portugal.

SMEs could improve integration in innovation networks, while partnerships in terms of technology licensing are widespread

As analysed in Chapter 1, Portuguese SMEs remain weakly integrated into innovation networks on average compared to SMEs in most other OECD economies, despite their relatively good performance with respect to innovation outcomes and digitalisation. Part of this weakness may be due to comparatively fewer firms with internationally recognised quality certificates in Portugal. Across all types, manufacturers in Portugal are less likely to have quality certificates compared to the same types of firms in other OECD economies for which data are available (including Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, the Slovak Republic and Slovenia) (Figure 3.4, Panel B). As expected, larger and foreign-owned firms are more likely to have certificates compared to smaller domestic firms. It would useful to further examine the costs of certification and monitoring and evaluation of certification processes across sectors and countries, but related data were not available for this study (see Chapter 5 on policy efforts in Portugal to enhance certification).

Figure 3.4. Foreign technology licensing and international certification in the Portuguese manufacturing sector, 2019

Note: Selected OECD include: Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Slovak Republic and Slovenia

Source: OECD based on World Bank Enterprise Surveys.

Focusing on a specific form of partnerships – namely technology licensing – reveals a more encouraging perspective on partnerships in manufacturing sectors of Portugal. Domestic firms – including medium-sized firms – extensively engage in licensing agreements with foreign firms, which as showed in numerous existing studies helps to deepen linkages between SMEs and foreign MNEs and thereby supports performance improvements. Approximately 40% of medium-sized and large manufacturing firms have technology licensing agreements with foreign companies (Figure 3.4, Panel A); this share is lower for small firms and non-exporting firms. Almost all affiliates of foreign manufacturers in Portugal (90%) use technologies licensed from (other) foreign firms; this share is much higher compared to foreign-invested companies in other selected OECD countries for which data are available. This underlines that foreign firms engage in operations in Portugal that require a certain level of technological sophistication, supporting skills improvements and productivity of the local workforce. The gap between foreign and domestic firms in terms of use of foreign licensing is lowest in the Lisbon Metropolitan area (see Chapter 1, Figure 1.16).

Partnerships of SMEs deliver innovation and learning opportunities and market access

A 2020 survey of SME owners/managers in the Portuguese automobile and parts sector (Franco and Haase, 2020[10]), shows that innovation and learning (e.g. consolidation of market position, quality improvement, sharing of resources and competences) is their main motive to engage in business partnerships with other firms (Figure 3.5). Other key motives for inter-firm partnerships relate to exploiting market opportunities (e.g. achieve competitive advantages and gain access to new markets).

The survey further shows that 45 of the 65 SMEs (or 70% of the SMEs) engage in only formal or both formal and informal partnerships with clients and suppliers (Table 3.2). The majority of these arrangements take place with partners within Portugal

Figure 3.5. Motives for inter-firm partnerships of SMEs in the automobile sector in Portugal

Note: This figure is based on interviews with 65 SME owners/managers in the Portuguese automotive and parts sector.

Source: OECD based on Franco and Haase (2020[10]).

Table 3.2. Characterisation of inter-firm partnerships in the Portuguese automotive sector, 2020

% of SMEs out of a sample of 65 SMEs interviewed

|

Inter-firm partnerships’ characteristics |

% |

|---|---|

|

Type of partner Supplier |

23 |

|

Supplier and client |

23 |

|

Client and complementary firm |

15.4 |

|

Others |

38.6 |

|

Formality of the agreement |

|

|

Formal |

41.6 |

|

Informal |

30.7 |

|

Formal and informal |

27.7 |

|

Number of partners |

|

|

1 firm |

20 |

|

2 firms |

15.4 |

|

3 to 6 firms |

35.4 |

|

7 to 9 firms |

7.7 |

|

More than 10 firms |

21.5 |

|

Geographical Area |

|

|

Portugal |

60 |

|

Abroad |

15.4 |

|

Portugal and abroad |

24.6 |

Note: This table is based on interviews with 65 SME owners/managers in the Portuguese automotive and parts sector.

Source OECD based on Franco and Haase (2020[10]).

3.4. Labour mobility and skills effects related to FDI entry in Portugal

Labour mobility can be an important source of knowledge spillovers in the context of FDI, notably through the move of MNE workers to local SMEs. This can occur through temporary arrangements such as detachments, long-term arrangements such as open-ended contracts, or through the creation of start-ups (i.e. corporate spin-offs) by (former) MNE workers. However, mobility can also occur in the opposite direction, also involving potential for spillovers. This section assesses spillover potential through labour mobility and associated skills effects in Portugal.

Dynamic FDI and SME sectors in Portugal facilitate labour mobility from foreign firms to SMEs

Up-to-date evidence on labour mobility practices and related productivity spillovers on SMEs is currently lacking for Portugal. Detailed evidence from studies in the early 2000s, tracing all spells of inter-firm worker mobility in Portugal (covering both the manufacturing and services sectors) over 1990-2000 provides some insights whose implications may be relevant for today’s discussion (Martins, 2011[11]; Martins, 2005[12]).

The studies reveal that labour mobility between foreign affiliates and domestic firms was a rather rare phenomenon in Portugal in the 1990s. Those few workers that moved from foreign to domestic firms experienced a decrease in average wages, which could be interpreted by involuntary mobility during a period of a significant fall of FDI inflows in Portugal related to a slowdown of privatisation, economic recession in Europe and radical geopolitical changes, namely the fall of the Soviet Union (Castro and Buckley, 2001[13]). This low mobility from foreign to domestic firms suggests that worker mobility was most likely not a major source of productivity spillovers from foreign to domestic firms in the 1990s.

Over recent years (pre-COVID-19), however, Portugal experienced an opposite trend with FDI stocks increasing from 30% to 60% of GDP over 2005-2020 and a dynamic and innovative SME and start-up sector has been developing (see Chapter 2). Accordingly, a pattern of increased labour mobility due to a more dynamic economy could have occurred recently, as evidenced by the case of Ireland that has experienced a similar rise of FDI over recent year (OECD, 2020[2]). Evidence in support of this hypothesis is currently not available.

FDI in high technology activities in Portugal is associated with an increase of supply of skills in the medium term

The analysis in Chapter 1 shows that Portugal is competing for FDI in high technology activities, particularly in manufacturing. While this strategy supports Portugal’s productivity growth and overall upgrading, it is important to recognise that any new establishment of high technology foreign firms involves new demand for skilled workers in the vicinity of the foreign firms’ location (Becker et al., 2020[14]).

As foreign firms are often more productive than their domestic peers, due to their higher capital, technological and managerial endowments, they can typically pay higher wages and attract the most talented workers. In Portugal, workers employed by foreign manufacturers earn 80% higher wages compared to those employed by average domestic firms; similar wage premia of workers in foreign firms are observed in the Czech Republic and Hungary for example (Figure 3.6, Panel A). Recent evidence shows that in Portugal large firms pay 20% higher wages than SMEs (OECD, 2019[15]); accordingly, the premia provided by foreign firms are likely to relate to their large size and higher productivity. Evidence of labour mobility from domestic to foreign firms in Portugal and other EU countries further confirms that such movements translate into considerable pay increases for workers (Becker et al., 2020[14]; Martins, 2011[11]).

Given the relative technological sophistication of foreign firms vis-à-vis domestic (mostly smaller) firms, workers are likely to acquire new knowledge in foreign firms, which then translates into productivity spillovers from this type of labour mobility. Beyond acquiring knowledge from foreign firms on-the-job, formal in-house training may also occur. The training and on-the-job learning opportunities offered by MNEs may also be extended to the workforce of local companies with which they develop linkages. These training opportunities are prevalent in the context of value chain relationships (vertical linkages) by which foreign-owned firms provide staff training to domestic suppliers as a way to ensure efficiency and product quality (OECD, 2019[5]).

Skills are a scarce resource in any OECD and partner economy, including in Portugal, and particularly in remote and less developed regions. The presence of foreign firms in high technology sectors is thus likely to put pressure on the labour market and increase demand for highly skilled workers. Increased demand will not only contribute to increased salaries for workers at foreign firms but will provide any worker with incentives to train themselves and for domestic SMEs to engage in training activities for their workers. This is likely to increase supply of skills in the medium-term. In Portugal (as well as in the Czech Republic for example), domestic firms are relatively more likely to engage in formal training as compared to foreign firms, illustrating domestic firms’ appetite to improve skills and remain competitive (Figure 3.6, Panel B). Establishing partnerships and collaboration with domestic vocational schools or higher education institutions (HEIs) (e.g. joint dual education programmes) is another way for foreign MNEs to address skills shortages in the local labour market and lower staff recruitment and requalification costs, with positive effects on skills endowments of the local workforce in the longer term (OECD, 2021[16]).

This is further supported by the OECD scoreboard on skills and global value chains (OECD, 2017[17]): the scoreboard uses selected indicators from the Programme for the International Assessment of Adult Competencies (PIAAC) and the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) to identify the extent to which relevant skills for the integration in GVCs have improved (e.g. decreasing shares of unskilled adults, improvements of cognitive skills among adults and secondary school students, or growth in tertiary graduation). Portugal outperformed all other OECD economies in terms of skills improvements relevant for GVC integration over 2000-15. This finding supports the argument that FDI entry, GVC integration through trade, capacities of SMEs and workers are interdependent; improvements or growth in one area may support improvements in another area. Determined policy action for skills development has been key in Portugal in this context and will be discussed further in Chapter 5, also see (OECD, 2018[18]).

Figure 3.6. Foreign firms’ premia relative to domestic firms, 2019

Note: See methodology in OECD (2019[5]).

Source: OECD FDI Qualities Indicators 2019 based on World Bank Enterprise Surveys, 2020

Figure 3.7. Changes in participation in global value chains and skills

Note: The figure shows the scoreboard indicators capturing the development of participation in GVCs and the evolution of skills relevant for GVC integration (OECD, 2017[17]). Countries in the upper part of the figure are among the top 25% that have increased their participation in GVCs the most while those in the lower part of the figure are among the bottom 25% that have increased their participation in GVCs the least. Countries in the right-hand side of the figure are among the top 25% that have increased their skills the most while those in the left-hand side of the figure are among the bottom 25% that have increased their skills the least. Countries in the middle of the figure are around the average.

Source: (OECD, 2017[17]).

3.5. Competition and imitation effects of FDI

Existing concepts on FDI-SME diffusion also look at competition and imitation effects of FDI on SME productivity and innovation. This section discusses how and to what extent such effects might be at play in the Portuguese FDI and SME sectors, arguing that these effects take place in specific situations of market interactions (including competition for talent and skills), value chain linkages, strategic partnerships and labour mobility The section thus builds extensively on the discussion above and in Chapter 2.

Competition and imitation effects are likely to benefit relatively more productive and innovative SMEs in Portugal

Beyond labour mobility effects, the previous section also argued that the entry of foreign firms heightens the level of competition on domestic companies, putting pressure on them to become more innovative and productive – not least to retain skilled workers (Becker et al., 2020[14]). The new standards set by foreign firms – in terms of product design, quality control or speed of delivery – can stimulate technical change, the introduction of new products, and the adoption of new management practices in local companies, all of which are possible sources of productivity growth (OECD, 2020[1]). This rising competitive pressure due to foreign firm entry and related productivity spillovers may also be associated with new incentives for workers to improve skills and SMEs to engage in skills upgrading in the medium term, as shown for Portugal in the previous section (Figure 3.7).

Foreign firms can also become a source of emulation for local companies, for example by showing better management practices. Imitation, reverse engineering and tacit learning can, therefore, become a channel to strengthen enterprise productivity at the local level. Foreign firms may also participate in innovation clusters and collaborative innovation activities where cross-fertilisation of ideas can increase productivity both of domestic and foreign firms. Section 3.3 showed that, on average, SMEs in Portugal engage relatively less often in collaboration networks, in which peer-to-peer learning including with foreign firms may take place, compared to SMEs in other OECD economies. Yet, the small sub-group of SMEs that is innovating new products or processes in Portugal often does so in contexts of cooperation with other firms. This illustrates that positive imitation/demonstration effects through cooperation with other firms take place in Portugal but could be further strengthened.

FDI involves increased competitive pressure for domestic SMEs

If local companies are not quick or not able to adapt, competition from foreign-owned companies may also result in the exit of some domestically-owned firms. This will of course also depend on other factors such as the market size and growth rate of the market, whether or not foreign firms serve the same market (engage in the same activities) and on the number of producers in the market. Increased competition for talent may also make it more difficult for local companies to recruit skilled workers (Lembcke and Wildnerova, 2020[19]) (see also Section 3.4). These effects are more likely to happen to local companies which operate in the same sector or value chain function of the foreign-owned company, which is the main reason why positive horizontal spillovers from FDI are so rare and, when they happen, they mostly involve larger domestic companies (Gorodnichenko, Svejnar and Terrell, 2014[20]; Farole and Winkler, 2014[6]).

As discussed throughout this report, the capacity of domestic firms to absorb knowledge from foreign firms will determine whether increased competition results in higher or lower productivity (positive or negative spillovers). Comparing performance of European countries in Becker et al. (2020[14]) reveals that limited spillovers in less developed regions, including in Portugal, are related to challenges to absorb foreign knowledge. This is also supported by other evidence for Portugal showing that geographical proximity between the locations of MNEs and domestic firms facilitates the occurrence of FDI spillovers (Crespo, Fontoura and Proenca, 2009[21]). The impact is negative in the case of horizontal externalities, i.e. domestic firms experience a negative productivity impact in proximity of foreign firms in the same sector, which may result from the competition effect at the regional level and limited absorptive capacities. With regard to vertical externalities (value chain linkages), a positive productivity shock is observed, further supporting arguments made in Section 3.2 on the importance of value chain relationships.

Evidence for Portugal further indicates that the presence of foreign firms benefits the small fraction of highly productive domestic firms but not necessarily the bulk of less productive firms (Fernandes, 2013[22]). Inequality in productivity among Portuguese companies has increased over time, evidencing a slowdown in the catching up process of companies during a period of strong FDI inflows (CompNet, 2020[23]). In this context, the productivity of the top performing companies (the most productive in each industry) presents an important contribution in the evolution of aggregate productivity, both through their performance as well as by the way they spread new technologies and business practices in the economy. This further illustrates that the potential for FDI spillovers is higher when firms have a sufficient set of absorptive capacities (Castellani and Pieri, 2010[24]).

References

[14] Becker, B. et al. (2020), “FDI in hot labour markets: The implications of the war for talent”, Journal of International Business Policy, Vol. 3, 107–133.

[3] Cadestin, C. et al. (2019), Multinational enterprises in domestic value chains, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9abfa931-en.

[24] Castellani, D. and F. Pieri (2010), The Effect of Foreign Investments on European.

[13] Castro, F. and P. Buckley (2001), “Foreign direct investment and the competitiveness of Portugal”, https://www.fep.up.pt/docentes/fcastro/CISEP2001.pdf.

[23] CompNet (2020), Firm Productivity Report, https://www.comp-net.org/fileadmin/_compnet/user_upload/Documents/Productivity_Report_FINAL-.pdf.

[21] Crespo, N., M. Fontoura and I. Proenca (2009), “FDI spillovers at regional level: Evidence from Portugal”,”, Papers in Regional Science, Vol. 88(3): 591–607.

[6] Farole, T. and D. Winkler (2014), Making Foreign Direct Investment Work for Sub-Saharan Africa: Local Spillovers and Competitiveness in Global Value Chains, World Bank, Washington, DC, http://dx.doi.org/10.1596/978-1-4648-0126-6.

[22] Fernandes, N. (2013), Investimento Directo Estrangeito e Produtividade: uma análise ao Nível da Empresa, Universidade do Minho, https://repositorium.sdum.uminho.pt/bitstream/1822/26813/1/TESE_Nuno%20Miguel%20Ribeiro%20Fernandes_2013.pdf.

[10] Franco, M. and H. Haase (2020), “Interfirm Partnerships and Organisational Innovation: Study of SMEs in the Automotive Sector”, Journal of Open Innovation Technology Market and Complexity, Vol. 6(193).

[20] Gorodnichenko, Y., J. Svejnar and K. Terrell (2014), “When does FDI have positive spillovers? Evidence from 17 transition market economies”, Journal of Comparative Economics, Vol. 42(4), 954-969.

[8] J., S. (ed.) (2006), The Theoretical Framework: FDI and Technology Transfer, Palgrave Macmillan, London.

[19] Lembcke, A. and L. Wildnerova (2020), Does FDI benefit incumbent SMEs? FDI spillovers and competition effects at the local level, OECD Publishing, Paris, p. No. 2020/02, https://doi.org/10.1787/47763241-en.

[7] López González, J. et al. (2019), Participation and benefits of SMEs in GVCs in Southeast Asia, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/3f5f2618-en.

[11] Martins, P. (2011), “Paying More to Hire the Best? Foreign Firms, Wages, and Worker Mobility”, Economic Inquiry,, Vol. 49 (2), 349-363, http://ftp.iza.org/dp3607.pdf.

[12] Martins, P. (2005), “Inter-Firm Employee Mobility, Displacement, and Foreign Direct Investment Spillovers”, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/228614727_Inter-Firm_Employee_Mobility_Displacement_and_Foreign_Direct_Investment_Spillovers.

[16] OECD (2021), Geography of Higher Education (GoHE), https://www.oecd.org/cfe/smes/geo-higher-education.htm.

[1] OECD (2020), Enabling FDI diffusion channels to boost SME productivity and innovation in EU countries and regions: Towards a Policy Toolkit, Concept Paper for joint EC-OECD project..

[2] OECD (2020), FDI Qualities Assessment of Ireland, http://www.oecd.org/investment/FDI-Qualities-Assessment-of-Ireland.pdf.

[5] OECD (2019), FDI Qualities Indicators: Measuring the sustainable development impacts of investment, https://www.oecd.org/fr/investissement/fdi-qualities-indicators.htm.

[15] OECD (2019), SME and Entrepreneurship Outlook 2019, SME and Entrepreneurship Outlook 2019, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/d2b72934-en.

[18] OECD (2018), OECD (2018), Skills Strategy Implementation Guidance for Portugal: Strengthening the Adult-Learning System, OECD Skills Studies, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264298705-en.

[17] OECD (2017), OECD Skills Outlook 2017: Skills and Global Value Chains, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264273351-en.

[4] OECD-UNIDO (2019), Integrating Southeast Asian SMEs in Global Value Chains.Enabling Linkages with Foreign Investors, http://www.oecd.org/investment/Integrating-Southeast-Asian-SMEs-in-globalvalue-chains.pdf.

[9] Pereira, D. and J. Correia Leitão (2013), Restructuring in SMEs Portugal, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/284654674_Restructuring_in_SMEs_Portugal.

Notes

← 1. This report primarily uses Ireland, Czech Republic, Slovak Republic, and sometimes Hungary and Lithuania, as comparators. They were chosen based on their economic size, outward orientation driven by foreign investors and EU membership.

← 2. See Chapter 2, Box 2.1, for an introduction to the classification of sectors used in this report.

← 3. See (OECD, 2020[1]) for a review of the literature.