This chapter provides a comparative assessment of the institutional set-up of the revolving fund schemes for affordable housing in Latvia and four peer countries. It outlines the main features of the approach in each country and proposes a series of recommendations and good practice cases for consideration by the Latvian authorities to ensure that the Fund’s governance, scope of activities and range of engaged actors can, over time, contribute to achieve the country’s strategic objectives for housing.

Strengthening Latvia’s Housing Affordability Fund

3. Setting up a revolving fund scheme to channel investment into affordable housing in Latvia

Abstract

An effective institutional set-up for revolving fund schemes helps to ensure that the scope of the Fund’s activities is aligned with, and is designed to respond to, broader strategic housing policy objectives; that enabling legislation and structures are in place to facilitate the operation and evolution of the fund’s activities; and that relevant actors are involved in the activities of the funding scheme and have the capacity to carry out their responsibilities.

In line with these objectives, this chapter assesses three dimensions of the institutional set-up in Latvia and four peer countries:

the framework conditions to establish and operate the funding mechanism;

the scope of activities of the Fund (e.g. new construction, renovations, demolitions, maintenance, land acquisition, as well as the geographic scope of the interventions);

the actors and expertise involved in the affordable housing finance system.

For each of these dimensions, the chapter first provides a comparative snapshot, highlighting where Latvia stands in comparison with peer countries, and then builds on the international practices to point at policy recommendations of relevance for Latvia.

3.1. Framework conditions to establish and operate the funding scheme

3.1.1. Where does Latvia stand in comparison to peer countries?

Table 3.2 provides a comparative snapshot of the framework conditions to establish and operate a revolving funding scheme for affordable and social housing:

All five countries rely on enabling legislation at the national level to regulate the operation of the housing finance system. This legislation sets the terms of the benefits, limits and responsibilities of the different actors therein.

The four peer countries have linked the housing funding scheme to a broader national housing policy. This link can be set up through a strategy document based on a prioritisation analysis (Slovenia) or national targets and directions translated into subnational planning decisions (Austria and Denmark). In the Netherlands, the Ministry of the Interior and Kingdom Relations defines the overall housing agenda and framework within which the housing associations operate. Latvia is developing national housing guidelines to make the case for developing the fund and guide its operation.

The structure of the funding and financing mechanism varies widely across countries. Latvia’s Housing Affordability Fund is a dedicated fund designed to channel investment into affordable housing – similar to Denmark’s National Building Fund and the HFRS in Slovenia. Contrary to Latvia, the Danish and Slovenian funds are stand-alone institutions with a dedicated staff. Latvia, however, will embed the fund in existing funding institutions (the state‑owned development finance institution, Altum, and the Public Asset Manager, the Possessor). By contrast, Austria and the Netherlands do not have dedicated revolving funds per se; rather, the system of actors and financing tools (e.g. in the case of the Netherlands, loan guarantees) operate as a sort of revolving fund, with staff and resources to manage the funds located across housing associations and different government bodies.

Table 3.1. Comparative snapshot: Framework conditions to establish and operate a revolving funding scheme

|

Latvia |

Austria |

Denmark |

The Netherlands |

Slovenia |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Structure |

A dedicated housing fund: the Housing Affordability Fund, established through Cabinet regulations in July 2022. |

No single dedicated revolving housing fund. The LPHAs itself function as revolving funds and thus represent each a self-sustaining financing mechanisms. LPHA have high equity shares and out of this they are regarded as very secure lenders and receive commercial loans at favourable conditions. LPHA finance 100% of land cost and 10‑20% construction cost of new projects from their equity; tenant contributions (3‑7%) and have access to public loans regulated by federal provinces at favourable terms like other private and for-profit housing investors. |

A dedicated housing fund: the National Building Fund, an independent institution established in 1967. |

No dedicated revolving housing fund. Housing associations can access a guarantee fund (WSW) that backs the largest share of outstanding capital market loans. This system of housing associations together operates as a sort of revolving fund, based on the ability of housing associations to access lower interest rates from WSW and their co‑operation agreement to bail out housing associations if/when required. The State and municipalities serve as guarantors of last resort. |

A dedicated housing fund: the HFRS, a state‑owned fund established in 1991. Eight municipal housing funds complement the national fund. |

|

Enabling legislation |

Regulation on support for the construction of affordable rental houses (2022). |

Limited-Profit Housing Act, which regulates the institutional features and legal framework of the LPHA. (e.g. limitation of business activities and profits for stakeholders; cost-based rent calculation). |

1946 Housing Subsidy Act. 1949 Built-up Areas Act. |

New Housing Act (2015), which defines the core tasks and responsibilities of housing associations. |

2003 National Housing Act. 2008 Public Funds Act. 2015 Resolution on the National Housing Programme for the period from 2015 to 2025 (ReNSP15‑25). Article 78 of the Constitution of the Republic of Slovenia (decent housing). |

|

Links to housing policy |

A forthcoming national housing strategy, Housing Affordability Guidelines. |

National policy directions are provided via regular revisions to the Limited-Profit Housing Act. Housing policy is mainly set at a regional level via housing subsidy laws and regulations. |

The national government sets out quantitative thresholds for new social housing development to avoid concentrating social dwellings in specific neighbourhoods. This is further supported through the development of social master plans, co-financed by the National Building Fund and municipalities, to facilitate social mixing. Municipalities decide whether, where and what types of social housing can be built in their municipality, to ensure new housing matches local housing needs. |

The national government sets the overall housing policy framework and enabling environment for housing and construction, and also establishes the rules relating to rental regulations and supports. |

The National Housing Programme defines government goals and planning. The National Housing Fund implements the National Housing Programme and funds investment projects. The National Housing Act provides a legal framework for the Housing Programme and Fund since 2003. The HFRS identifies priority areas for housing development and investment (PROSO) at national scale. |

3.1.2. Recommendations for Latvia based on peer practices

Policy Action 1: Ensure the alignment of the Fund with the Housing Affordability Guidelines, complemented by local targets developed in co‑operation with municipalities

The Latvian Housing Affordability Fund is envisaged as a long-term instrument which, building on initial EU Recovery and Resilience Facility (RRF) funding, aims to address a range of housing affordability challenges in the country. To meet these objectives, it will be critical to align the Fund’s activities with the Housing Affordability Guidelines under development by the Ministry of Economics (Box 3.1), and to ensure co‑ordination with other housing-related investments and funding streams relating to, inter alia, social housing and housing renovation. The Guidelines are intended to serve as the country’s comprehensive strategic agenda for housing, establishing a core set of priorities related to housing quality and affordability. The Guidelines propose a wide, integrated vision for housing, with a scope that goes beyond that of the Fund (for example, with specific attention to housing for vulnerable groups and housing quality). The Fund focuses on one key priority outlined in the Guidelines: to increase housing affordability for the “missing middle.” It will be important to monitor the contributions of the Fund to the performance indicators at the national level that are set out in the Guidelines.

Box 3.1. Latvia’s forthcoming Housing Affordability Guidelines

The Latvian Ministry of Economics developed a draft document on Housing Affordability Guidelines in 2022, currently under review by stakeholders. The draft focuses on a core set of priorities related to housing quality and affordability, including an explicit mention of the creation of “a housing affordability fund that would ensure the reinvestment of funding invested in housing affordability measures in future housing affordability measures, promoting long-term financing of such measures.” The guidelines aim to promote the availability of quality housing for all population groups by investing in both the improvement of the existing housing stock and promoting investments in the development of new housing stock. Among the priority target groups: (1) vulnerable households; (2) middle‑income households (including through the establishment of a revolving fund for housing); and (3) households to acquire housing on market terms.

Equally, the activities of the Fund should be linked to specific targets at the local level, which should be developed in collaboration with municipalities. The experience from Slovenia in ensuring the alignment of the Fund with broader national and local housing targets can serve as a useful reference in this regard (Box 3.2).

Box 3.2. National guidance for housing investment: The role of the National Housing Fund in implementing Slovenia’s National Housing Programme

Slovenian housing policy is structured around three main pillars (ECSO, 2019[1]):

The National Housing Programme (Nacionalni Stanovanjski Program), which defines the government goals and planning, setting quantified objectives and priorities for intervention;

The National Housing Fund (Stanovanjski Sklad Republike Slovenije), which implements the National Housing Programme and funds investment projects, working collaboratively with municipalities to translate these priorities into action at the local level; and

The National Housing Act (Stanovanjski zakon), which since 2003 provides a legal framework for the Housing Programme and Fund, supporting greater efficiency in the provision and management of the housing stock.

A Resolution on the National Housing Programme for the period from 2015 to 2025 (ReNSP15‑25) adopted in 2015, defined the National Housing Fund as the main state authority for the implementation of the National Housing Programme, in collaboration with other bodies and agencies across government at the national and local level, such as municipalities, as required in the Resolution. Collaboration with municipalities is particularly important as it helps to identify priority areas for new housing development (PROSO).

Source: (Housing Fund of the Republic of Slovenia (HFRS), 2022[2]), Housing Fund of the Republic of Slovenia (HFRS), https://ssrs.si/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/P_LPSSSRS21.pdf. (European Commission, 2019[3]) (ECSO, 2019[1]; European Commission, 2019[3]), European Construction Sector Observatory – Policy Fact Sheet, Slovenia National Housing Programme; (Mežnar et al., 2013[4]), The Paradox of Slovenian Housing Stock: Lacking a Proper Management?, https://econpapers.repec.org/bookchap/tkpmklp13/1425-1433.htm.

Table 3.2. Policy Action 1: Ensure the alignment of the Fund with broader the Housing Affordability Guidelines, complemented by local targets developed in co‑operation with municipalities

|

Objective |

|

|

Actions and timeframe |

|

|

By 2026 |

|

|

Beyond 2026 |

|

|

Institutions/stakeholders involved |

|

|

Key implementation steps |

|

Policy Action 2: Establish a Supervisory Board to oversee the operations of the Fund and its evolution over time

Embedding the Fund within existing funding and asset management institutions (Altum and the State Asset Possessor) is an efficient choice in the initial phase. This institutional set-up allows the Latvian authorities to move quickly within the framework of the European Union’s Recovery and Resilience Fund, avoids the costs of establishing a new institution, and can facilitate alignment with existing housing support measures (for example, funding schemes to support housing renovation, which are already provided by Altum). As the Housing Affordability Fund evolves, the Latvian authorities could consider creating a Supervisory Board to guide the Fund’s activities, while maintaining a lean institutional structure. The Board could include representatives of the central government and municipalities from the outset. The experience from Slovenia, for instance, could serve as inspiration (Box 3.3).

Box 3.3. Providing strategic guidance to the national fund over time: Experiences from Denmark and Slovenia

Denmark: A dedicated board with representation from municipalities

The Danish NBF is managed by a board of nine members. Precise rules determine the members of the board. The chairman of the board and four other members are elected by the National Association of Housing Associations. Two members of the board, who must be social housing tenants, are elected by the Tenants’ National Organisation in Denmark. One member is elected by the National Association of Municipalities, and one member is elected jointly by Copenhagen and Frederiksberg municipalities. Elections of all members take place every four years.

Specific eligibility criteria for the Fund’s board members are described in the Public Administration Act (e.g. individuals who have reached the age of 70 cannot be elected as a member of the board or as a deputy for a member). The Act also contains rules about the board’s functions, voting procedures and frequency of meetings. The board’s tasks include decisions relating to the management of the day-to-day administration of the Fund and establishing guidelines for the organisation of the work. General regulations and instructions issued to depositors and borrowers must be approved by the board.

The Slovenian Fund’s Supervisory Board

The Slovenian Fund is managed by a Supervisory Board and represented by a Director, who is appointed for a four‑year term. The Supervisory Board has five members. They include: two representatives of the competent Ministry (as of February 2023, the Ministry of Solidarity-based Future), who must be experts in the field of housing or spatial planning and construction of residential buildings; a representative of the ministry responsible for finance, who must be an expert in the accounting or financial field; one member from the beneficiaries or users of the fund services; one member for the legal area, who must be an expert in the real estate sector. The members of the supervisory board are appointed by the government upon a proposal from the competent minister. The term of office of the members of the Supervisory Board is four years with the possibility of reappointment.

Source: (Housing Fund of the Republic of Slovenia (HFRS), 2018[5]), The Housing Fund of the Republic of Slovenia – Short presentation, https://ssrs.si/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/Short-presentation-of-HFRS.pdf.

Table 3.3. Policy Action 2: Establish a Supervisory Board to oversee the operations of the Fund and its evolution over time

|

Objective |

|

|

Actions and timeframe |

|

|

By 2026 |

|

|

Beyond 2026 |

|

|

Institutions/stakeholders involved |

|

|

Key implementation steps |

|

3.2. Scope of activities financed

3.2.1. Where does Latvia stand in comparison to peer countries?

Table 3.4 provides a comparative snapshot of the scope of activities financed by the revolving fund schemes, focusing on the type of activities financed and their geographical reach:

In most peer countries, the scope of activities eligible for funding support is generally broad, including housing construction, renovation and maintenance. For example, in the Netherlands, there is a broad remit of housing associations’ activities and neighbourhood responsibilities. In Denmark, in addition to new housing construction and renovations, the Fund can also contribute to social and infrastructure investments. The scope of activities of Latvia’s Fund is narrower than that of peer countries, in that it is restricted to the development of new affordable rental housing. Currently developed as a pilot project, Latvia’s fund is established with initial financing of EUR 42.9 million through the RRF, and will only operate only in areas where the biggest market failures have been identified (outside the Riga and Pierīga regions).

In all peer countries, the geographic scope of projects funded through revolving fund schemes covers the entire national territory, with projects throughout the country generally eligible to receive funding support. Different approaches exist to geographically target affordable housing within the national territories. In the Netherlands, housing associations generally work in pre‑defined housing market regions, specific areas are not excluded from construction. Austria leaves decisions around new affordable housing construction to the LPHA, and the location of affordable units must be co‑ordinated with government planning permissions. Denmark provides dynamic criteria at the municipal level to avoid the concentration of affordable housing in social hotspots. Slovenia does not require specific geographic targets, but a majority of housing investments must align with the specific housing needs outlined in the PROSO. The geographic scope of Latvia’s Fund differs, however: at least in the initial phase, funding through the scheme is limited to projects developed in municipalities and rural areas outside the Capital region, in order to address housing investment gaps in regions.

Table 3.4. Comparative snapshot: Scope of activities financed

|

Latvia |

Austria |

Denmark |

The Netherlands |

Slovenia |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Types of housing activities |

Development of new affordable rental housing and maintenance. |

Housing construction, maintenance and renovation of buildings, as well as management of municipal housing stock. LPHA can also acquire existing dwellings to convert into social and affordable housing, but this happens rarely. |

Construction and renovation of social/affordable housing; modernisation and refurbishment of existing dwellings; social master plans (co-financed with municipalities). The fund can also contribute to social and infrastructure investments. |

New housing construction, maintenance, acquisition of dwellings, nursing and retirement homes. Dwellings must meet minimum quality standards, including relating to energy efficiency. |

Encouraging housing construction, renovation and maintenance of apartments and residential buildings |

|

Geographic scope of intervention |

In a first phase, dwellings must be built outside Riga and neighbouring municipalities. Initially, 120 rental apartments may be established simultaneously in selected administrative territories, and 60 rental apartments outside the territories. Further approvals can be made dependent on the fulfilment of a minimum occupancy rate. It is envisaged to potentially expand the geographic eligibility to include Riga and neighbouring towns in a subsequent phase if justified by a market gap analysis. |

Throughout the country (LPHA prioritise new development areas, dense regions and cities) |

Throughout the country, aligned with housing needs outlined in local development plans and with the aim of avoiding concentration of disadvantaged households in specific neighbourhoods. Construction of social housing in municipalities with vacancy issues (>2% vacancy rate) are not approved. |

Throughout the country. Each housing association has to limit its new activities to a certain ‘housing market region’ (19 regions in the Netherlands). |

Throughout the country, aligned with housing needs outlined in the PROSO |

3.2.2. Recommendations for Latvia based on peer practices

Policy Action 3: Ensure that the scope of the Fund’s activities is aligned with complementary interventions to address other housing challenges

Current plans to limit the activities of the Fund to the construction and maintenance of new affordable rental housing are sensible in the initial phase. Altum is already providing loans for renovation and improvements of existing dwellings. It would be important to ensure in the short- to medium-term that the support schemes complement each other. The distinct scope of each support scheme should help to avoid overlapping activities.

Over time, as the Fund builds up its funding capabilities (cf. see the recommendations under Policy Actions 9 and 11), it may also be relevant to broaden the scope of the Fund’s activities to include, for instance, housing improvements and/or neighbourhood revitalisation, as done in some peer countries (Box 3.4). This would be especially appropriate given the wide range of economic and demographic profiles and housing challenges that are faced by different Latvian regions. Indeed, while some regions, experience high industrialisation and economic development, others lag behind, as also evidenced by significant differences in average income levels across regions. Housing challenges are also diverse across Latvian regions: for example, some regions have an acute need for comprehensive repairs of dwellings constructed in industrialised areas during the Soviet era; others, particularly those in rural areas, require more upfront investments to make new housing development more attractive.

Box 3.4. Tailoring the scope of activities of the funding scheme to match needs: The broad remit of the Danish National Building Fund

The Danish National Building Fund can support a wide range of activities, including renovations of the existing housing stock, as well as social and preventative measures in vulnerable areas, the development of social master plans that are co-financed with municipalities to support interventions related to security and well-being, crime prevention, education and employment and parental support.

The Danish approach also comprises investments in technical and social infrastructure in the broader environment of affordable housing. Notably, the Fund has been used to provide support to the construction industry during periods of economic slowdown.

Table 3.5. Policy Action 3: Ensure that the scope of the Fund’s activities is aligned with complementary interventions to address other housing challenges

|

Objective |

|

|

Actions and timeframe |

|

|

By 2026 |

|

|

Beyond 2026 |

|

|

Institutions/stakeholders involved |

|

|

Key implementation steps |

|

Policy Action 4: Expand the geographic scope of the Fund over time to also include the capital region, based on a mapping of needs

Initially, the Fund aims to incentive investment in the housing stock outside the capital region, where fewer investment opportunities exist. This decision may be justified in the short term. Over time, depending on the resource capacity of the Fund and a clear mapping of housing needs, the Fund could expand the geographic scope to support investment in affordable housing in Riga and the surrounding region, following the approach taken by the four peer countries reviewed in this project. Currently, no systematic process exists in Latvia to monitor the diverse and changing housing needs across regions. The Latvian authorities could develop a clear process to assess regional needs to identify housing quality and investment gaps and address high levels of regional disparities. The decision-making on where, and for whom, the Fund’s action is most needed should crucially hinge on the collection of data and evidence on housing needs.

Assessing regional needs will allow for a better targeting of the Fund’s activities and might justify expansions to the Fund’s radius of action (see also Policy Action 3). For example, the extension of the Fund’s activities to the Capital region might call for greater diversification in the types of housing activities eligible to receive support through the Fund (e.g. beyond new construction), as Riga presents specific housing needs. In particular, as raised in the stakeholders´ activities organised as part of the project, the Fund’s actions in the Capital region (as well as in other regions, where relevant) could also include the acquisition and renovation of existing property, which could then be leased to eligible tenants at an affordable rent. This is the case in Slovenia, for instance, where the Housing Fund of the Republic of Slovenia (HFRS), takes on multiple roles, including as an investor and co‑investor of public rental units, a buyer of available housing units on the market, and a purchaser of land for housing construction. Together with its subsidiaries, the HFRS rents out 6 965 housing units across Slovenia as of end 2022. Following the Slovenian example, the Latvian Fund could play a more active role in the acquisition and management of already developed dwellings in the Capital region. Slovenia is also a relevant example for its system for mapping priority areas for development (Box 3.5).

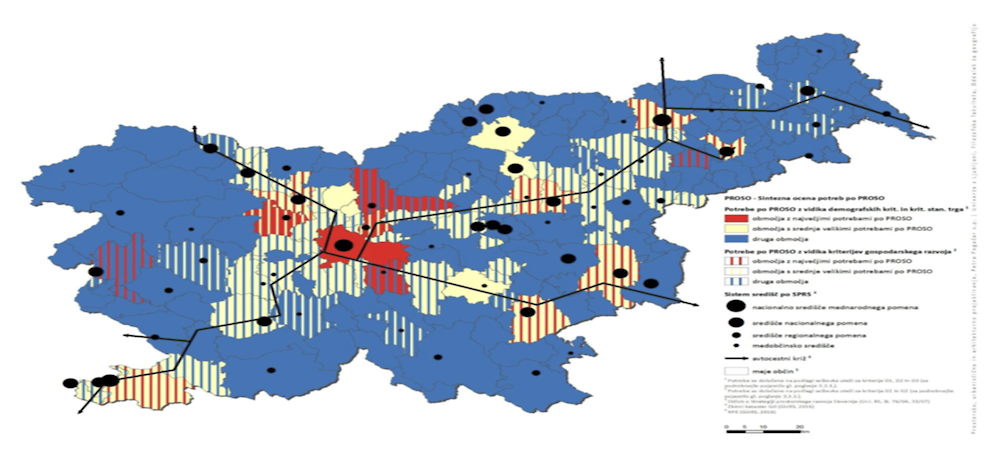

Box 3.5. A structured model to assess municipal housing needs: Slovenia’s Priority Development Areas for the Housing Supply

Slovenia devised priority development areas for the housing supply (PROSO) as the main tool to guide policy action and housing investment throughout the country. The two‑stage model quantifies housing needs in different parts of the country (Figure 3.1). The Housing Fund of the Republic of Slovenia is then obliged to allocate 60% of its investments according to the needs identified in the PROSO. The remaining 40% of investments are allocated on a needs’ basis assessed through applications submitted by municipalities to the Fund. As the PROSO was prepared in November 2016, relying on data collected since 2011, the HFRS complements the PROSO data with biannual surveys across all 212 local communities and public housing providers. The PROSO is expected to be updated in the framework of the preparation of the next National Housing Programme.

Figure 3.1. Results of a housing needs assessment in Slovenia

Source: Presentation by Mojca Štritof-Brus, Housing Fund of the Republic of Slovenia and Alen Červ, Ministry of Environment and Spatial Planning at the Working Meeting with Latvian stakeholders organised by the OECD in 2022. Information from Final report: Opredelitev in določitev prednostnih območij za Stanovanjsko oskrbo, PROSO, November 2016, page 78.

Table 3.6. Policy Action 4: Expand the geographic scope of the Fund over time to also include the Capital region, based on a mapping of needs

|

Objective |

|

|

Actions and timeframe |

|

|

By 2026 |

|

|

Beyond 2026 |

|

|

Institutions/stakeholders involved |

|

|

Key implementation steps |

|

3.3. Actors and expertise involved in the affordable housing finance system

3.3.1. Where does Latvia stand in comparison to peer countries?

Table 3.7 provides a comparative snapshot of the actors and expertise involved in affordable housing finance and describes their respective competencies. The comparison encompasses both public and private actors, including ministries, implementing agencies, municipalities, housing developers and tenants:

National ministries take on a lead policy making role for housing. Across countries (and including in Latvia), national-level ministries are responsible for overall housing policy making and for establishing the legal frameworks for housing policy. Differences in the housing-related tasks performed by each responsible Ministry depend on the particular set-up of the funding mechanism, as well as the overall mandate of the competent Ministry. None of the countries examined in this report has a dedicated Housing Ministry; for instance, the competence for housing policy is the responsibility of the Ministry of Economics (Austria, Latvia); the Ministry of Interior (Denmark, The Netherlands); or the Ministry of Solidarity-based Future (Slovenia)1 (Table 3.7). The scope of activities of the ministry can shape the scope of action relating to housing. For example, the Ministry of the Interior and Housing in Denmark also is also tasked with ensuring a balance between urban and rural areas.

Not all countries have a dedicated housing fund. Denmark and Slovenia operate a stand-alone revolving fund with dedicated staff; such a fund does not exist in Austria or the Netherlands. In addition, Slovenia also operates additional funds that operate in co‑ordination with the HFRS as part of the broader housing eco-system: eight municipal housing funds complement the national fund, alongside an Eco-Fund that facilitates investment in environmental projects (including environmentally-oriented residential renovations). HFRS and the Eco-fund collaborate on a project basis and exchange information on EU projects and housing financing opportunities. As mentioned, Latvia’s Housing Affordability Fund is not structured as a stand-alone fund with a dedicated staff.

Subnational governments also play a key role in housing development. Municipalities are important actors in housing development in Latvia, given their responsibilities for, inter alia, developing territorial plans and setting land use objectives. In peer countries, subnational actors also play an important strategic role in housing policy. In Austria, for instance, regional governments define housing policy through subsidy laws and land use planning. In Denmark, local governments determine whether, where and what types of social housing can be built in their municipality, and allocate up to one‑quarter of vacant social dwellings to households in urgent need.

Housing associations are important in some countries, while less so in others. In most peer countries, non- and low-profit developers play a central role in developing and renovating affordable housing. These actors are not widespread in Latvia or Slovenia, where the housing market is dominated by commercial for-profit developers.

Table 3.7. Comparative snapshot: Actors and expertise involved in the affordable housing finance system

|

Latvia |

Austria |

Denmark |

The Netherlands |

Slovenia |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

National-level ministry responsible for the Fund |

The Ministry of Economics is the primary decision-making body on the use of the Housing Affordability Fund. It is responsible for overall housing policy making; establishing the Regulations that govern the establishment, functioning and financing of the fund; and monitoring compliance with the provisions of the Regulation. |

The Federal Ministry for Digitisation and Economic Affairs (BMDW) is responsible for defining the legal framework conditions for the limited-profit housing industry. Federal/regional governments set the housing policy priorities; set laws and regulations (e.g. land zoning category of “subsidised housing” in Vienna); provide housing loans and subsidies and loans and are responsible for monitoring LPHA (with regional governments and the auditing association responsible for auditing). |

The Ministry of the Interior and Housing develops housing policy, approves the Fund’s budget, and ensures balance between urban and rural areas. |

The Ministry of the Interior and Kingdom Relations is responsible for overall housing policy making; creating an enabling environment for housing and construction; defining the legal framework conditions for the affordable and social housing sector, establishing the rules for, inter alia, subsidies, rent policy, rent allowances; supporting and monitoring housing market performance. Also responsible for backstop agreement with WSW. |

Since February 2023, the Ministry of Solidarity-based Future oversees housing policy and is part of the supervisory board of the Fund. [NB: housing policy was previously the responsibility of the Ministry of Environment and Spatial Planning] |

|

Other actors at the national level (including implementing bodies) |

Altum, a state‑owned development finance institution, is responsible for the administration of the Fund; selecting viable housing projects to be supported; monitoring the use and repayment of loans; and transferring the repayments of the principal and interest payments to the Fund. The Possessor, the State’s public asset manager, is responsible for monitoring after the commissioning of the affordable dwelling and the granting of the capital rebate to developers. |

N/A |

The National Building Fund is an independent institution that operates outside the state budget. The Fund is governed by a board of nine members, with an independent Secretariat. The Housing and Planning Agency (Bolig- og Planstyrelsen) – an agency under the responsibility of the Ministry of Interior and Housing – is responsible for the development of the social/affordable housing sector, urban renewal, construction, spatial planning and rural development. |

The Social Housing Guarantee Fund (Waarborgfonds Sociale Woningbouw, WSW) ensures favourable financing for housing associations by providing guarantees to lenders for social housing projects. WSW deals with guarantee issues, sets guarantee ceilings, and assesses and manages risks at association and portfolio levels. The Housing Associations Authority (Autoriteit woningcorporaties, AW) acts as the supervisory body of housing associations and oversees their activities, governance and financial management; AW supervises WSW. BNG bank is a Dutch public sector bank that provides loans to the public sector (inc. housing associations) to maximise social impact. |

The Housing Fund of the Republic of Slovenia operates within the framework of the state but is a separate legal entity and financially independent. The Slovenian Environmental Public Fund (Eco Fund), established in 1993, is a revolving fund providing financial support to individuals, companies and municipalities (including municipal housing funds) for environmental projects. This includes the distribution of grants and loans for residential building renovation with favourable conditions directly to citizens. |

|

Municipalities |

Municipal authorities are responsible for developing territorial plans, setting land use objectives, and solving housing issues of residents. Regarding the Housing Affordability Fund, they must establish an entrustment act with the real estate developer that defines the public service to be provided by the developer. They must also establish and monitor a queue of eligible tenants for the units. |

Municipalities are responsible for local planning permissions and the availability of land. In parallel to LPHA, they may also be responsible for providing affordable housing. If affordable/social housing is financed via public subsidies, municipalities have priority on the allocation rights and the rest is allocated by LPHA. Housing allocated by municipalities is means-tested and the income ceilings are stated in housing subsidy laws and vary by federal province/region. |

Municipalities provide capital, guarantees and subsidies to housing associations. They also approve rent schemes, administer rent subsidies, organise the production and maintenance of schemes and have a key role in monitoring and regulating associations. Their role also includes implementing national guidelines through municipal plans; determining whether, where and what type(s) of social dwellings may be built; and they may allocate a quarter of vacant social housing units to households in urgent need (the remainder are allocated via waiting lists). |

Municipalities are responsible for land policy and planning, and land use and zoning regulations, within the boundaries set at national/provincial level. Since 2015, social housing associations are required to engage in annual agreements with municipalities and representatives of their tenants on issues such as new construction, investments in sustainability and rent price policy (e.g. rent increases). With the ministry, they are responsible for the backstop agreement. |

Municipalities adopt and implement the municipal housing programme, including providing capital for the construction, acquisition and leasing of non-profit and residential buildings for social housing; encouraging owner-occupied and rental housing; providing capital for subsidising non-profit rents. They are responsible for financing their own housing programmes. The Housing Act enables municipalities to establish a public housing fund or a budgetary housing fund to support housing at the local level. |

|

Housing developers |

For-profit, as well as non- and low-profit housing developers are eligible to benefit from public incentive schemes; however, non- and low-profit developers are not widespread in Latvia. |

Affordable and social rental housing is provided by Limited Profit Housing Associations (LPHA) and local public authorities. LPHA are independent institutions with a specific legal form: either limited-liability companies (GesmbH) or public limited companies (Aktiengesellschaft) with no tradeable shares or co‑operatives. |

Around 520 non-profit housing associations develop affordable/social housing. They are responsible for the daily operations of the developed social/affordable housing units, the allocation of units and making decisions to initiate new developments, which must be approved by the local government. |

Housing associations develop most of the social housing stock and contribute to meeting housing needs in the municipality in which they work. They are responsible for the management of their housing stock; contractual relations with tenants; and quality of life in the neighbourhood. With tenant organisations, they make performance agreements to determine the number of houses to be built. Aedes: sector association of most Dutch housing associations; acts as a platform for its members to safeguard their interests and as an employer organisation. |

Non-profit housing associations can be established under the provisions of Article 152 of Housing Act as state‑ or municipal-owned entities. In collaboration with municipalities, their role is to manage and lease non-profit housing, and determine and manage land use. Non-profit housing associations can apply for co-financing of non-profit housing projects under HFRS programmes. |

|

Tenants |

Tenants: in addition to paying rent, tenants are responsible for making utility payments, real estate tax and insurance payments, and covering maintenance and management expenses. |

Tenants contribute to the financing of LPHA activities (3‑7% on average) by granting a quasi-loan to the association, in the form of a down payment. This amount is returned to tenants when they move out, depreciated by 1% for each year of occupation of the dwelling. |

Tenants play a key role given their financial contributions to the Fund through their rents. Tenant democracy: All Danish housing associations are managed on the principle of “tenant democracy,” which enables social housing tenants to hold a majority vote in the board of housing associations, where they influence issues such as estate management, budget, maintenance and refurbishment projects. |

Tenant organisations advocate on behalf of tenants on various topics of interest, including housing quality, availability affordability, as well as corporate responsibility for social housing associations. |

Municipalities may establish a council for the protection of tenants’ rights, which consists of representatives of tenants. Representatives of municipal councils for the protection of tenants’ rights assemble in the National Council for the Protection of Tenants’ Rights. This represents the interests of tenants before state authorities when they deal with issues related to housing. |

3.3.2. Recommendations for Latvia based on peer practices

Policy Action 5: Facilitate the emergence of new housing actors, such as housing associations and/or limited-profit developers. While housing associations currently play a very limited role in affordable housing development in Latvia, there is merit in considering how to foster their development over time. The experience in Austria, Denmark and the Netherlands can serve as inspiration (Box 3.6). This could take the form of targeted outreach to existing associations and capacity development for these types of providers, as well as the creation of tax incentives. For example, Austria and Denmark grant corporate tax exemption for housing associations that engage in the construction of affordable rental housing. In Denmark, housing associations are also exempted from VAT.

Based on peer country experiences, the residential units produced by not-for-profit and limited-profit developers generally offer lower rents than those of market-rate rental housing, and such providers are usually obliged to reinvest revenue surpluses back into new affordable housing development and maintenance. Moreover, such developers can channel funds from both public and private sources to support affordable housing development, in compliance with EU State Aid regulation (Box 3.7).

The experience of other countries, and in particular Austria, suggests that non-profit housing associations typically target a distinct segment of the housing market that is otherwise not covered by commercial for-profit developers. As such, there could be a role for limited-profit developers, smaller local contractors and/or municipal housing companies to support the Fund’s housing development across Latvia.

Box 3.6. Engaging housing associations and limited-profit developers in affordable housing development: Experiences from Austria and the Netherlands

Housing associations as a distinct third sector in the Austrian housing market

In Austria, housing associations are a distinct third sector in the housing market, which are neither state‑owned nor profit-driven, building on an obligation to reinvest their profits into affordable housing. Housing associations are responsible for more than two‑thirds of the social and affordable housing stock, in a country that has the second highest social housing stock in the OECD (24% of the total housing stock in 2019).

The segmentation of the Austrian housing market helps serve the needs of different target groups. In practice, limited-profit developers target a different share of the market than the for-profit sector. They provide housing for both low- and medium income households, with also a mitigating effect on rents in the for-profit sector (Klien et al., 2023[6]).

The multi-stakeholder Dutch model for affordable housing

In the Dutch multi-stakeholder system, different actors at the central and local levels co‑operate to build, allocate and maintain social housing. The central government establishes the eligibility criteria to access social housing and rent subsidies; rental market regulations; and regulations that govern social housing organisations. Municipalities are responsible for developing a housing vision, determining local housing targets, and managing land policy and planning. Housing associations, which develop the majority of the social housing stock, must help meet the housing needs in the respective municipality in which they operate, and together with the tenant organisations make performance agreements (e.g. the number of houses to be built).

As will be discussed later in this chapter, a special-purpose public fund (WSW) and the public banks, BNG and NWB, together provide funding outside the State budget and ensure the financial viability of the system through a system of loan guarantees. Other actors, including commercial banks, pension funds and international capital markets provide additional funding for housing associations. The Housing Associations Authority (AW) provides an overall supervisory function for housing associations, and for the sector as a whole.

Box 3.7. Not-for-profit and limited profit housing providers and state aid in Austria and Denmark

The EU defines State Aid as a distortionary market intervention by a state entity or with state resources that provide recipients with an advantage over competitors on a selective basis that likely has an effect on trade between member states. For this purpose, the European Commission enforces rules that regulate State aid. Economic activities that represent Services of General Economic Interest (SGEI) are exempted from State Aid regulation. SGEI describe economic activities that would not be provided under equal conditions if market forces alone were at play. As social housing falls within the scope of SGEI, EU State Aid rules do not inhibit public support for social housing investment. Despite the general exemption of social housing, the good practice examples illustrate strict conditions for agents in the sector to qualify their activities as SGEI:

In Austria, Limited Profit Housing Associations (LPHA) have access to favourable financing terms (due to their high equity ratio as they are each long-term revolving funds) and benefit from corporate tax exemption. At the same time, they are obliged through the Limited-Profit Housing Act (LPHA) to reinvest their profits into affordable housing on cost-based pricing. They have also, like private and for-profit investors, access to public loans and guarantees if they fulfil the given conditions.

In Denmark, the rental balance principle ensures that social housing is a non-profit sector, meaning that tenants pay the same amounts in rents that housing associations incur for building, maintaining and managing dwellings. Even though public incentives for housing associations in the form of tax advantages exist, the recipients fully pass the savings to the tenants.

Source: (European Commission, 2022[7]), Competition Policy: State Aid Overview, https://competition-policy.ec.europa.eu/state-aid/state-aid-overview_en; (European Commission, 2011[8]), State aid: Commission adopts new package on State aid rules for services of general economic interest (SGEI) – frequently asked questions, https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/MEMO_11_929.

Table 3.8. Policy Action 5: Facilitate the emergence of new housing actors, such as housing associations and/or limited-profit developers

|

Objective |

|

|

Actions and timeframe |

|

|

Beyond 2026 |

|

|

Institutions/stakeholders involved |

|

|

Key implementation steps |

|

Policy Action 6: Assign a greater strategic role to municipalities in planning the Fund’s housing investments

Increased engagement of municipalities can help to ensure that the scope of the Fund’s activities more closely reflects and responds to local needs. Such involvement would also be in line with international practices (e.g. Denmark, Slovenia Box 3.8) that facilitate an important role for municipalities in the housing sector, for example in terms of contributing to the development of a housing vision or guiding the decision-making on the location of new affordable housing construction.

Box 3.8. The role of municipalities in advancing housing policies in Denmark and Slovenia

Denmark

Municipalities are key actors for housing in Denmark, where they provide capital, guarantees and subsidies to housing associations. They also approve rent schemes, administer rent subsidies, organise the production and maintenance of schemes and have a key role in monitoring and regulating associations. Moreover, support from the National Building Fund is obtained through applications submitted by housing organisations and the development of a fiscal master plan, agreed upon with municipalities, is the precondition to access support from the Fund. The master plan should contain information such as a brief description of the residential challenges, statistical key figures for the housing organisation, a budget estimate of a minimum of 25% local co-financing and a municipal recommendation.

Municipalities decide whether (and which) housing associations can build in their municipality and which types of dwellings will be built (number of family homes, residences for the elderly, etc.). They play an important role in the process allowing for new social housing to better match local housing needs. Decisions on where new affordable housing projects will be built are taken based on need and social mixing criteria, which aim to create neighbourhoods with a mix of income levels and social groups. Municipalities may allocate 25% of all social housing units, giving priority to certain groups, such as families with children, people with disabilities, people exiting institutional care, the elderly, and people experiencing homelessness.

Slovenia

Slovenian municipalities play a significant role in advancing housing policies, which includes adopting and implementing a municipal housing programme, and providing capital for the construction of social housing buildings. The Public Housing Fund of the Municipality of Ljubljana (PHF) currently manages 4 433 housing units, of which 3 817 are not-for-profit accommodation units that are rented to individuals and families via public tenders.

The Housing Act also enables municipalities to establish a public housing fund to support housing at the local level. Accordingly, several municipalities have set up local housing funds: Ljubljana, Nova Gorica, Novo mesto, Murska Sobota, Koper and Ajdovščina Local authorities can join forces to set up a housing fund together; for instance, Maribor’s public housing fund is co‑owned by four municipalities. The National and Local Housing Funds can co-finance projects and act independently.

Table 3.9. Policy Action 6: Assign a greater strategic role to municipalities in planning the Fund’s housing investments

|

Objective |

|

|

Actions and timeframe |

|

|

Beyond 2026 |

|

|

Institutions/stakeholders involved |

|

|

Key implementation steps |

|

Policy Action 7: Plan an active involvement of tenants in the activities of the Fund from the start

The Regulation establishing the Fund stipulates that a share of the rental revenue will eventually be channelled into the Fund to contribute to the funding of new affordable housing construction (Cabinet of Ministers (Latvia), 2022[9]). This “revolving” dimension of the funding scheme relies implicitly on an important role for tenants; however, their role in developing affordable housing in Latvia could be more explicit in the Fund’s activities, and recognised from the start. Once the dwellings are put into operation and occupied, tenants could be represented in the Supervisory Board of the Fund, as is the case in other peer countries (e.g. Denmark and the Netherlands, Box 3.9). As the ultimate beneficiaries/users of the Fund, tenants can serve as a sounding board to new investments and help provide advice and feedback on the management of the existing stock. In addition, a Tenant Committee should be established to handle disputes and complaints related to the management and operation of the affordable rental units.

Box 3.9. Representing tenants’ interests: Approaches in Denmark and the Netherlands

Tenant democracy in Denmark

The Danish social housing sector has a tradition of tenant participation and self-governance. All Danish housing associations are managed on the principle of “tenant democracy”. This unique feature of the Danish social housing model enables tenants of housing associations to exert significant influence over estate management. Since the 1970s, each housing association has been led by a Management Board where residents have the majority, and municipalities are also often represented. Each estate owned by a housing association is treated as a separate financing entity and has its local tenant board. Every year, at an annual tenant meeting, the tenants of each housing estate elect a tenant board responsible for estate management and financial governance. Majority votes of tenants are required for major changes (e.g. estate management rules and major maintenance and refurbishment projects).

Among other things, tenants approve or alter the budget, as well as potential increases in rent levels (OECD Affordable Housing Database). A majority of tenants must also approve any proposed sales of dwellings in their estates. The sale of property (e.g. an entire building) also requires permission from the State. This model is beneficial for tenants, who can contribute to the management of their dwellings while housing associations take care of maintenance and operations. Moreover, the tenant democracy principle creates an incentive for tenants to play an active role in the housing sector and for landlords to be responsive to residents’ needs and to maintain affordable rental prices.

In addition, the Danish system foresees dedicated complaints bodies, in the form of tenants’ boards of appeal composed by three persons; an impartial chairperson with a legal background, a representative of the landlord and a tenants’ representative. In the case of house‑rule violations a social counsellor, typically a social worker employed by local government, attends the board in order to give advice with respect to the kind of sanctions judged appropriate. The counsellor has no voting right. Boards have a mediation role. In certain cases, they can issue a notice to the tenant to quit but cannot expel a tenant.

Tenant organisations in the Netherlands

The Dutch system gives special attention to tenants as key actors in the housing system, with strong rules and regulations protecting tenants’ rights. Tenant organisations advocate on behalf of tenants and owner-occupants on various topics of interest, including housing quality, availability affordability, as well as corporate responsibility for social housing associations. Tenant organisations operate throughout the Netherlands in cities, localities, at the housing association level and even the building level. Housing associations can set up or join with other housing associations to set up a complaint committee that can handle disputes between tenants and the housing association as the landlord. The committee serves as an appeal board if the tenant and the landlord do not reach an agreement or the tenant is not satisfied with the proposed solution.

Since 2018, these tenant groups are also involved in the discussions of housing strategy at the municipal level. The new rule mandates tenant groups, municipalities and housing corporations to convene yearly and discuss future goals in housing (e.g. strategy for development of new housing, renovations, affordability and long-term goals). In line with increasing responsibilities, the ministry has been increasing funding to tenant groups to help them with resources for training and professionalisation.

Source: (Vestergaard and Scanlon, 2014[10]), Social Housing in Denmark, https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118412367.ch5; (Crites, 2018[11]), Woonbond: Representing the Tenants of the Netherlands, https://housing-futures.org/2018/01/11/woonbond-representing-the-tenants-of-the-netherlands-2/.

Table 3.10. Policy Action 7: Plan an active involvement of tenants in the activities of the Fund from the start

|

Objective |

|

|

Actions and timeframe |

|

|

By 2026 |

|

|

Beyond 2026 |

|

|

Institutions/stakeholders involved |

|

|

Key implementation steps |

|

References

[9] Cabinet of Ministers (Latvia) (2022), Regulations of the Cabinet of Ministers No. 459, Regulations on support for the construction of residential rental houses in the European Union Recovery and Resilience Mechanism Plan 3.1, https://likumi.lv/ta/id/334085-noteikumi-par-atbalstu-dzivojamo-ires-maju-buvniecibai-eiropas-savienibas-atveselosanas-un-noturibas-mehanisma-plana-3-1 (accessed on 23 May 2023).

[11] Crites, J. (2018), “Woonbond: Representing the Tenants of the Netherlands”, Housing Futures, https://housing-futures.org/2018/01/11/woonbond-representing-the-tenants-of-the-netherlands-2/.

[1] ECSO (2019), “Policy Fact sheet, Slovenia, National Housing Programme, Thematic objectives 1&3”, European Construction Sector Observatory (ECSO).

[7] European Commission (2022), Competition Policy: State Aid Overview, https://competition-policy.ec.europa.eu/state-aid/state-aid-overview_en.

[3] European Commission (2019), European Construction Sector Observatory: Policy fact sheet - Slovenia, National Housing Programme.

[8] European Commission (2011), State aid: Commission adopts new package on State aid rules for services of general economic interest (SGEI) – frequently asked questions.

[2] Housing Fund of the Republic of Slovenia (HFRS) (2022), Annual Report of the Housing Fund of the Republic of Slovenia for 2021, https://ssrs.si/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/P_LPSSSRS21.pdf (accessed on 23 May 2023).

[5] Housing Fund of the Republic of Slovenia (HFRS) (2018), The Housing Fund of the Republic of Slovenia - Short presentation, https://ssrs.si/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/Short-presentation-of-HFRS.pdf (accessed on 23 May 2023).

[6] Klien, M. et al. (2023), The Price-Dampening Effect of Non-profit Housing, WIFO Research Briefs, (6), 10 Seiten. Auftraggeber: Magistrat der Stadt Wien, https://wifo.at/pubma-datensaetze?detail-view=yes&publikation_id=70772 (accessed on 24 May 2023).

[4] Mežnar, Š. et al. (2013), “The Paradox of Slovenian Housing Stock: Lacking a Proper Management?”, pp. 1425-1433, https://EconPapers.repec.org/RePEc:tkp:mklp13:1425-1433 (accessed on 23 May 2023).

[10] Vestergaard, H. and K. Scanlon (2014), “Social Housing in Denmark”, Social housing in Europe, https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118412367.ch5.

Note

← 1. Up to February 2023, Slovenian housing policy was under the responsibility of the Ministry of Environment. This has changes with the Act on State Administration which transferred this responsibility to the Ministry of Solidarity-based Future.