This chapter presents key review findings and recommendations. The analysis is aligned to the HEInnovate framework with its seven dimensions and 37 statements. It provides a holistic framework for supporting entrepreneurship and innovation, including strategy, governance and resources, practices in organising education, research and engagement with business and society, and measuring impact. The analysis is based on study visits to nine institutions and the results of a system-wide HEI Leader survey.

Supporting Entrepreneurship and Innovation in Higher Education in The Netherlands

Chapter 2. Applying HEInnovate to higher education in the Netherlands

Abstract

Applying the HEInnovate guiding framework

HEInnovate describes the innovative and entrepreneurial higher education institution (HEI) as “designed to empower students and staff to demonstrate enterprise, innovation and creativity in teaching, research, and engagement with business and society. Its activities are directed to enhance learning, knowledge production and exchange in a highly complex and changing societal environment; and are dedicated to create public value via processes of open engagement”. How this can be translated into daily practice in HEIs is described through 37 statements which are organised within seven dimensions. This chapter presents key findings from applying the HEInnovate guiding framework to HEIs in the Netherlands. The information is based on the results of the HEI Leaders Survey in the Netherlands and information from detailed interviews with stakeholders in the case study HEIs.

Leadership and governance

Entrepreneurship is a major part of the strategy of the higher education institution

The entire higher education sector in the Netherlands – including research universities, technical universities and UAS – offers a variety of excellent examples of what it means for an HEI to be innovative and entrepreneurial. A central element is the valorisation of knowledge, that is, the process of creating value from knowledge by making it suitable and/or available for economic and/or societal use by translating knowledge into useful products, services, processes and entrepreneurial activity. Value creation encompasses all disciplines, and the impact of value creation goes well beyond economic aspects into generating societal and cultural value. For example, it also includes different ways of communicating research and research results in the media, expositions, community research, etc. In terms of support structures and dedicated education activities, entrepreneurship support can be considered the most developed part of value creation.

It is mandatory for HEIs in the Netherlands to have written and formally approved strategic plans. The surveyed HEIs reported that they review their strategies every four to six years in a participatory process which involves staff and students alongside a range of different external actors – local businesses and their representative organisations (84%), regional and local governments (80%), alumni (68%) and national government bodies (52%).

More than 60% of the surveyed HEIs have agreements with the government related to the entrepreneurship education activities they offer, and half for startup support measures. The term and concept of entrepreneurship is mentioned throughout the institutional strategies and several HEIs reported to have dedicated strategies for entrepreneurship support. All of the nine HEIs visited clearly demonstrated the embedding of entrepreneurship within their strategy and across the organisation as a whole. Dedicated and professional entrepreneurship teams continue to introduce new initiatives and bring in international partners. Entrepreneurship education and startup support are fully backed by senior management, often under the wider umbrella of value creation.

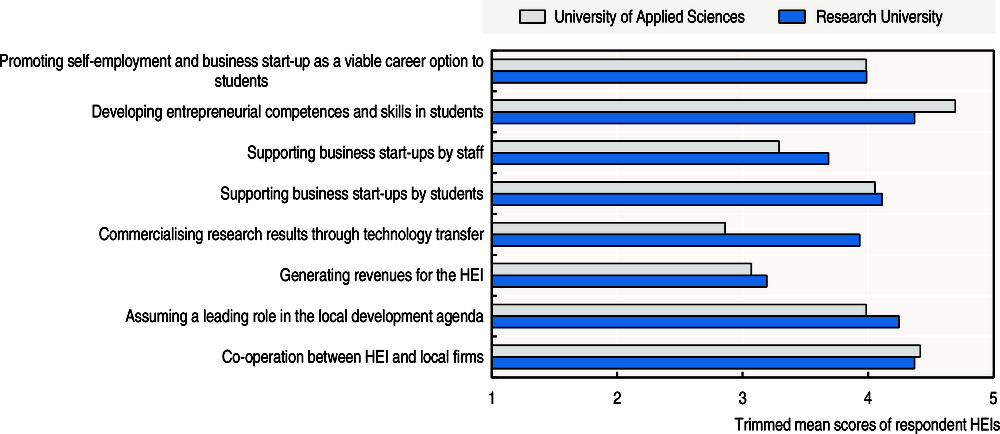

Figure 2.1 shows the varying entrepreneurship related objectives of the surveyed HEIs. In common is the desire of HEIs to help students develop entrepreneurial competences and skills, which both the research universities and the UAS rated as the most important objective of the entrepreneurial agenda. This was followed by co-operation between the HEI and local firms. Supporting startups amongst students was rated more important than supporting staff members in their venture creation activities. A notable difference exists with regard to commercialising research results through technology transfer: research universities saw this as having a greater importance than UAS. Lowest rated by all surveyed HEIs was generating revenues from the entrepreneurial agenda. Close to 80% of the HEIs reported to have performance measurements in place for these objectives.

Figure 2.1. Entrepreneurship objectives of Dutch higher education institutions

Notes: Higher education institutions (HEIs) were asked: “How important are the following objectives for your HEI?”. Respondents indicated the level of importance on a 5-point Likert scale from 1 = “Not important at all” to 5 = “Very important”. 5% trimmed mean scores are shown. The total number of responses was 25, of which 9 were from research universities and 16 from universities of applied sciences (UAS). The overall survey response rate was 48%. The survey response rates per HEI type are the following: research universities (60%), UAS (43%).

Source: OECD HEI Leader Survey The Netherlands (2016-17).

There is commitment at a high level to implementing the entrepreneurial agenda

An effective and sustainable implementation of the entrepreneurial agenda requires a high level of commitment. The starting point is building a shared understanding of what the entrepreneurial agenda means for the different stakeholders in the HEI, that is, leadership, academic staff, administrative staff and students, and for external partners (e.g. government, businesses, civil society organisations, donors). Central to this are communication and consultation about what the entrepreneurial agenda entails in terms of objectives, activities, priorities and resources. This can be linked with the process of defining and reviewing the HEI strategy. All surveyed HEIs reported involving staff and students in consultations. The information on entrepreneurship support is also well present on the institutional websites of the HEIs; it takes on average between two to three “clicks” to receive relevant and up-to-date information on the entrepreneurship education and startup support activities.

When considering the development of future policies to support value creation and entrepreneurship in Dutch higher education, consideration needs to be given to the co‐ordination of different policy actors. To build more and better synergies between the three core functions of Dutch higher education – education, research, value creation – co-ordination mechanisms between the different ministries are very important, as introduced, for example, in the Valorisation Programme (see Chapter 1).

Most of the HEIs surveyed offer entrepreneurship education activities which aim at competence development (92%), and slightly less offer targeted startup support (80%). More than half of the HEIs have created top-level management positions to support these activities, in addition to positions at departmental/faculty level and administrative staff (mostly for startup support). According to the HEI Leader Survey, on average one-third of students currently participate in entrepreneurship education activities, and the HEIs expect this to rise to over half of the student population in the next five years.

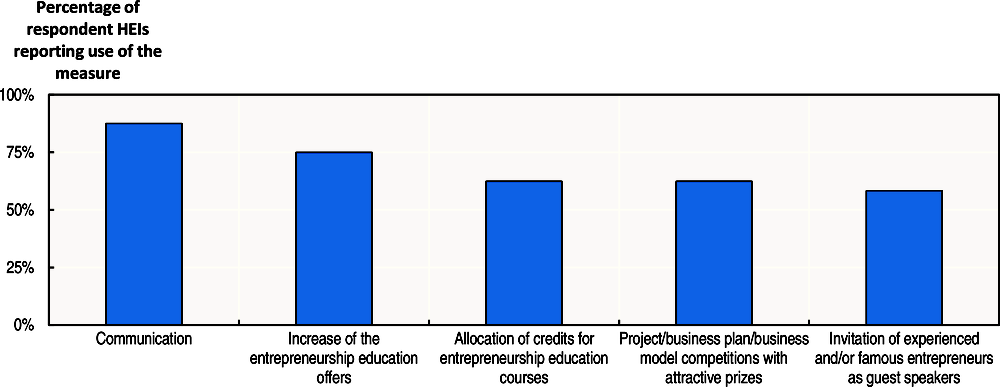

A range of targeted efforts are underway to increase participation rates and the offer of entrepreneurship education activities (Figure 2.2). Most common are the use of various communication channels and a greater offer of entrepreneurship education activities. Around 60% of the surveyed HEIs reported allocation of credits in line with the European Credit Transfer and Accumulation System (ECTS) as an effective way of raising the participation rate, along with the organisation of competitions with attractive prizes, and the invitation of experienced/famous entrepreneurs as guest speakers.

Figure 2.2. Measures to enhance participation in entrepreneurship education

Notes: Higher education institutions (HEIs) were asked: “What measures does your HEI implement to increase participation rates in entrepreneurship education activities?”. The total number of responses was 21, of which 8 were from research universities and 13 from universities of applied sciences (UAS). The overall survey response rate was 48%. The survey response rates per HEI type are the following: research universities (60%), UAS (43%).

Source: OECD HEI Leader Survey The Netherlands (2016-17).

There is a model in place for co-ordinating and integrating entrepreneurial activities across the HEI

HEIs across Europe have experimented with different approaches to establishing an effective model for co-ordinating and integrating various entrepreneurial activities across the institution, and to facilitate exchange of experiences and peer-support, particularly in education activities. A common approach is to anchor the entrepreneurial agenda within senior management, often in the form of a dedicated unit, which is part of the Rector’s/President’s or the Vice-Rector’s/Vice-President’s office. Another approach is to appoint a number of professors who have entrepreneurship in their title or a chair of entrepreneurship. An increasingly practiced approach is the establishment of an entrepreneurship centre to ensure easy access and visibility inside and outside the HEI. Whichever model is employed, it should take into account and build on existing relationships both inside the HEI and in the surrounding entrepreneurship ecosystem.

Examples of all three approaches are present in Dutch HEIs. The entrepreneurial agenda is supported and driven at senior management level most usually by a combination of the heads of faculty or departments and the valorisation or entrepreneurship centre. Most (76%) of the surveyed HEIs reported that they have a permanent contact point (e.g. entrepreneurship centre) where individuals or teams who would like to start up a business can go for support. More than two-thirds of these centres were an integral part of the HEI.

Some of the HEIs have established centralised support structures for valorisation and entrepreneurship support whereas others have opted for a decentralised approach to enhance proximity and create trust, and to diversify and target support services. Career services can also play a role in co-ordinating and integrating entrepreneurial activities across the HEI. These are relatively new in the Netherlands and started around the year 2000.

All visited HEIs have established Centres for Entrepreneurship to provide centralised support for entrepreneurship promotion. The entrepreneurship support activities and actors are not always well-connected across the HEI; there are cases when resources and programmes are located in different organisational units (entrepreneurship centre, valorisation centre, departments, research teams, entrepreneurs in residence, external lecturers, etc.). A better connection could be achieved by moving the institutional and logistical position from the periphery of the HEI to its centre; for example, anchoring valorisation and entrepreneurship in an institutionally more central position (e.g. Vice-Rector).

At the national level, the Dutch Centres for Entrepreneurship provide a platform for exchange and collaboration (Box 2.1).

Box 2.1. The Dutch Centres for Entrepreneurship

The Dutch Centres for Entrepreneurship (DutchCE) include 20 HEIs and engage them in four types of activity linked to entrepreneurship education. They engage in co-operation with each other to 1) foster a community, 2) exchange knowledge and best practices, 3) stimulate and promote entrepreneurship and entrepreneurship education in higher education, also via the development of new education techniques and methods), and 4) strengthen entrepreneurship research by facilitating national co-operation and stimulating new research that the community deems relevant to foster an entrepreneurial society.

In particular, the HEIs collaborating in DutchCE engage in applied research and they initiate and organise national or international activities to foster research on entrepreneurship. DutchCE also create wider impact by stimulating applicable insights from science, by sharing insights among a diverse audience using different channels, and by stimulating active participation in public and private contracts and the public debate.

In addition, the DutchCE also support policymaking by putting important topics related to entrepreneurship on the policy agenda, operating as a consultative body for government, politics and interest groups, and by offering validation and quality control through qualitative benchmarks. In addition, they connect with international networks and platforms such as the Global Entrepreneurship Network and academic organisations such as the Academy of Management and the International Council for Small Business.

Students are represented by a student division, the Dutch Students for Entrepreneurship (DutchSE). DutchSE aims to bring students and entrepreneurship together. They do this by creating a strong national network of (local) student entrepreneurship communities, in order to increase the passion, knowledge and resources of student entrepreneurship in the Netherlands.

Source: Interviews during the study visit in June 2016.

The HEI encourages and supports faculties and units to act entrepreneurially

Individual faculties and units in all of the HEIs visited clearly demonstrated an ability to develop faculty initiatives in both valorisation and entrepreneurship relevant to local, regional, national and, in some instances, international needs. This clearly shows the capacity of Dutch HEIs to be responsive to meet the needs of both internal and external stakeholders. The involvement of externals as guest speakers in the entrepreneurship education activities is, in most of the surveyed HEIs (86%), lower than one-quarter of the course. Most involved in teaching entrepreneurship were, in descending order, contracted staff, researchers, externals, full professors, associate/assistant professors, and PhD students.

An example of how to effectively support innovation in teaching and learning is the Utrecht Education Incentive Fund (Dutch: Stimuleringsfonds Onderwijs). Every year a total of EUR 2 million is made available to enhance educational innovations, for example in the area of digital teaching and assessment methods and active learning. Half of the funding is allocated to the departments based on the number of students. Deans decide the allocation of funding within the department in consultation with the Vice-Dean of Education and the Directors of Education. The funding can be used to support the career development of exceptionally talented teaching staff. EUR 1 million per year is allocated for university-wide development projects which last a maximum of three years, are supported by at least two faculties, tie in with the Utrecht University Strategic Plan 2016-20, and make a tangible contribution to knowledge sharing.

The HEI is a driving force for entrepreneurship and innovation in regional, social and community development

HEIs in the Netherlands are important actors in the social and economic development of their immediate environments, especially in a regional context. Based on the meetings conducted with external stakeholders, including regional development agencies, business and industry groups and local authority representatives, the HEIs are seen as key drivers for innovation in the wider regional, social and community environment. The HEIs visited have embedded academic expertise in local and regional development, capacity building, organisational development etc. within their own institutions. This practice was observed across all disciplines. Several examples of good and promising practice are discussed in Chapter 4, Chapter 5 and Chapter 6.

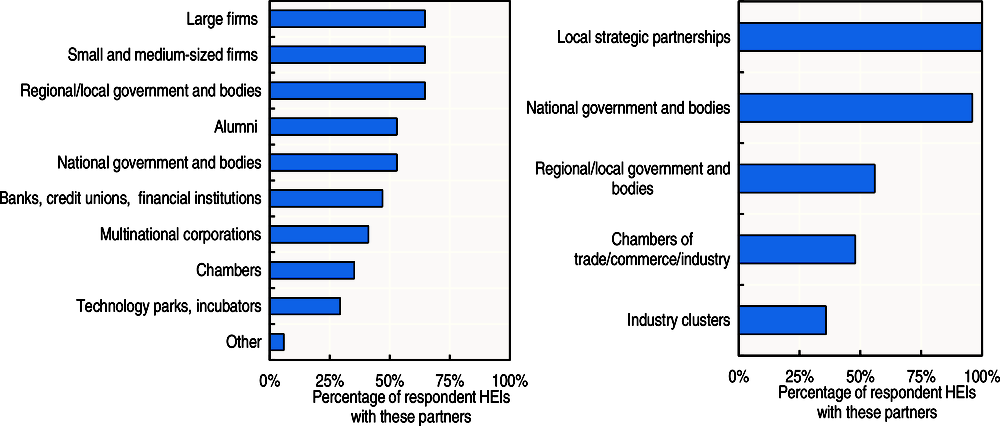

The HEI Leader Survey indicates that the HEIs have developed relationships with various public and non-public bodies for the purposes of contributing to local development (Figure 2.3). All of the surveyed HEIs reported to engage in local strategic partnerships; also very common was participation in regional government bodies that define the development directions of the surrounding economy. Less common was involvement of HEIs in industry clusters. Overall, less practiced was the participation of external stakeholders in the HEI’s governing bodies, which was reported by close to 70% of the surveyed HEIs. Approximately two-thirds of the surveyed HEIs reported that representatives of large firms, SMEs and regional/local government participate in their governing bodies. Less than one-third reported such collaboration with chambers of commerce and technology parks.

Figure 2.3. Strategic local development partners of Dutch higher education institutions

Notes: The chart on the left shows the involvement of external stakeholders in the governing bodies of Dutch higher education institutions (HEIs). Respondents were asked “Which of the following organisations or individuals are members of the governing board of your HEI?”. The total number of responses analysed was 17. The chart on the right shows the involvement of HEIs in governing boards or strategic positions of external stakeholders. Respondents were asked “Does your HEI participate in the governing boards of the following organisations and strategic initiatives to define the development directions of the surrounding local economy?”. All 25 HEIs responded to this question. The overall survey response rate was 48%.

Source: OECD HEI Leader Survey The Netherlands (2016-17).

There are numerous examples of how HEIs in the Netherlands act as driving forces for entrepreneurship and innovation in regional, social and community development.

Knowledge Mile is considered to be the street with the highest density of students in Amsterdam, with approximately 60 000 students in an area that stretches for about two kilometres from Nieuwmarkt to Amstelstation. The main initiator is the Amsterdam Creative Industries Network, one of the Centres of Expertise of the Amsterdam University of Applied Sciences (see Chapter 1 for more information on the Centres of Expertise in UAS). The aim is to establish a living laboratory which provides viable solutions to all kinds of urban challenges. Knowledge Mile works with more than 50 partners from industry, civil society, local and national governments to turn knowledge into value for all. One of them is Dopper!, a Dutch high-growth social enterprise producing re-useable plastic bottles. Together with Spotify, Beaver and the Design Thinking Center they kick-started with Knowledge Mile a challenge to make the area between Nieuwmarkt and Amstelstation the first PET-free street in the Netherlands (Knowledge Mile, 2017).

An example where collaboration with HEIs was initiated by industry is the Port of Rotterdam, a key European and global transport hub, which has actively engaged in research initiatives with the university sector to generate better solutions to the many challenges it faces. For the port, engaging with research and determining how to collaborate with HEIs is an ongoing process, with the aim of reducing the gap between science and practice in a pre-competitive way by engaging companies in scientific research. Smartport, one of the initiatives, serves as a common contact point and facilitates the application for public funding through pooling resources and reducing risk. The commercial and technological challenges of the port make it an ideal context for HEI-industry collaboration. Smartport provides an engaging and challenging environment for researchers who are willing to do things a bit differently and learn skills beyond the requirements of their academic institution. Rotterdam University of Applied Sciences, Erasmus University Rotterdam and Delft Technical University are key partners in Smartport (HEInnovate 2017a).

For the research universities, a lot has been documented by the umbrella organisation VSNU in an online publication with links to multimedia documentation (VSNU, 2017a). Information on how UAS interact with the local economy is usually available on the respective institution’s website. In the UAS, lectors, who often share their time between teaching, research and a business/industry appointment, play an important role in connecting education and research with local development needs and opportunities. The core aim of the lector is the integration of higher education and research and includes the supervision of research groups and acquisition of external funding (see Chapter 1).

Organisational capacity: Funding, people and incentives

Entrepreneurial objectives are supported by a wide range of sustainable funding and investment sources

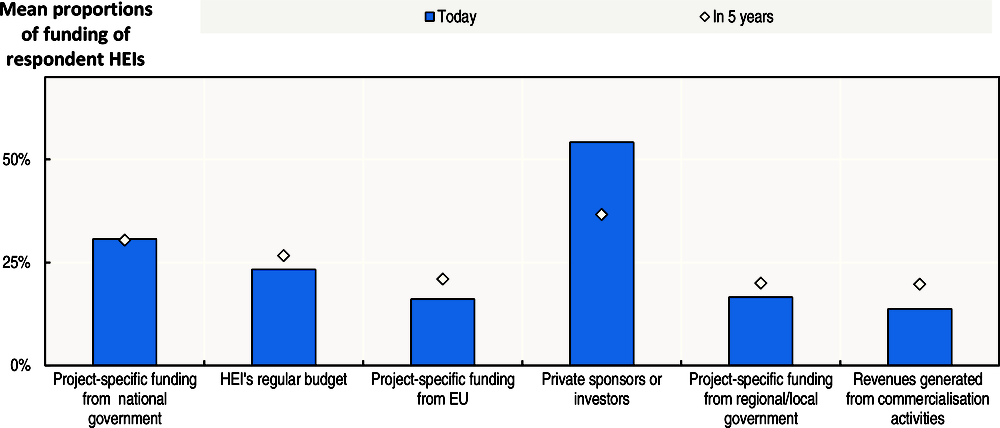

A particular feature of the Dutch higher education system, compared with the other countries that participated in HEInnovate reviews1, is that entrepreneurship support in HEIs receives a large share from private sponsors and investors, which account for more than 50% of the surveyed HEIs’ overall budgets for entrepreneurship support activities (Figure 2.4). Approximately one-third of the funding comes from national government, followed by the HEI’s own budget.

Figure 2.4. Financing entrepreneurship support in Dutch higher education institutions

Notes: Higher education institutions (HEIs) that currently offer entrepreneurship support were asked “What is the approximate ratio of the different funding sources your higher education institution uses to finance the entrepreneurship support activities?”, and “Looking ahead for five years what ratio do you expect to come from the following sources for financing these activities?”. The total number of responses was 23. The overall survey response rate was 48%.

Source: OECD HEI Leader Survey The Netherlands (2016-17).

When asked for their prognosis of how funding from private investors for entrepreneurship support will look in five years’ time, the surveyed HEIs expected a decline. The other sources are expected to grow, except for project-specific funding from national government, which is foreseen to remain at the same level.

The HEI has the capacity and culture to build new relationships and synergies across the institution

Several of the research universities and UAS have started to stimulate interdisciplinary initiatives, primarily in research but increasingly also linked with education activities (see Chapter 3 and Chapter 4).

The value of focusing on strategic interdisciplinary themes instead of discipline-focused niche areas will not be immediately obvious to all staff. The breadth of the themes and the requirement for interdisciplinary teams, however, can make people look at their research differently and recognise new value and connections. It is important that these themes allow for new and different perspectives to be explored on established issues, and that they offer opportunities for young researchers to get involved. This allows for research outside a specific discipline e.g. geographers or historians, to engage in future orientated entrepreneurial themes. Evaluating the impact and effectiveness of these approaches would be useful to clarify whether HEI-level initiatives are sufficient or need to be enhanced by national funding to establish (further) organisational support to organise and sustain interdisciplinary research and education.

At national level, new national research funding is also expected to stimulate cross-faculty co-operation (see Chapter 1 and Chapter 3). The valorisation centres and the policy advisors, who work directly with the HEI’s executive board, have proved to play important roles as scouts and gatekeepers, helping to spot opportunities and engineer interdisciplinary and external partnerships that will be increasingly relevant for the acquisition of external research funding.

According to the HEI Leader Survey, interdisciplinary study programmes are very common at bachelor’s level (92%) and master’s level (84%), and less common for doctorate programmes (44%). It is common that students participating in interdisciplinary courses and other education activities at both bachelor’s and master’s levels receive ECTS points, whereas this practice applies for less than half of the interdisciplinary activities available for doctoral students.

Collaboration between HEIs is well-established within the different parts of the higher education sector, that is, research universities with other research universities, and UAS with other UAS. Valorisation and entrepreneurship support has also increased collaboration between different types of HEIs, even though joint education programmes are still rare and difficult to organise because of accreditation matters and differences in student preparation and expectations. The national StartupDelta initiative, started in 2014, has been successful at keeping ecosystem initiatives focused on activities that are bottom-up and entrepreneur-led. In particular, the success of StartupDelta in building bridges between HEIs is relatively unique and should be encouraged (see Chapter 4).

The HEI is open to engaging and recruiting individuals with entrepreneurial attitudes, behaviour and experience

The valorisation agenda has been a major step towards supporting HEIs in their efforts to enhance knowledge exchange, innovation and entrepreneurship (see Chapter 1). When academic staff are recruited or promoted, their valorisation activities and outcomes are taken into account (e.g. considering patents and patent licensing agreements, contract research and development with companies or other organisations, spin-off creation, participation in non-governmental organisation (NGO) activities that contribute to local development or Triple/Quadruple Helix models of collaboration, teaching and learning activities, acting as a mentor to student entrepreneurs, etc.). Prior experience in the private sector is a common recruitment criterion for teaching and research staff in the UAS (75%) and less common amongst research universities (22%).

Highly qualified professionals who are fully dedicated to innovation and entrepreneurship activities have well-defined and attractive careers within the HEI with salaries that are partly funded from the HEI’s budget and not only from project-based funding and career development perspectives. This ensures that people with relevant knowledge and skills remain in such functions at the HEI or in the higher education sector. All of the visited HEIs have established the position of a policy advisor to the executive board, which took over the role of local HEInnovate co-ordinators. These positions seem to be crucial to allow the HEIs to contribute to national higher education policy making.

The HEI invests in staff development to support its entrepreneurial agenda

Training for teaching staff is well established in Dutch higher education. It has been practiced through formal programmes in the research universities since 2007 and similar initiatives are being introduced in the UAS. Maastricht University has created its own talent management through which people are identified by departments to enrol in training programmes. A standard approach is to mix researchers with administrative staff. Also common are retreats that last between three and four days with the aim of removing the pressure of research or teaching activities and helping participants to decide what could be good next steps in their career (What do I like? Where do I want to go?) with the help of a professional trainer.

Two-thirds of the surveyed HEIs offer training for staff involved in entrepreneurship support; training for staff involved in education activities is more common than training for staff involved in startup support activities (82% versus 67%).

In the training for teaching staff, closer connections could be developed with entrepreneurship education research, particularly with the entrepreneurial pedagogy whose pillars are co-operative learning, experiential learning and reflective learning. Focusing on entrepreneurship educators in particular, which typically includes a wide range of individuals with and without pedagogical qualifications, a national programme to train entrepreneurship educators could be considered to support teaching staff in innovative pedagogies and learning outcome assessment methodologies (see Chapter 4).

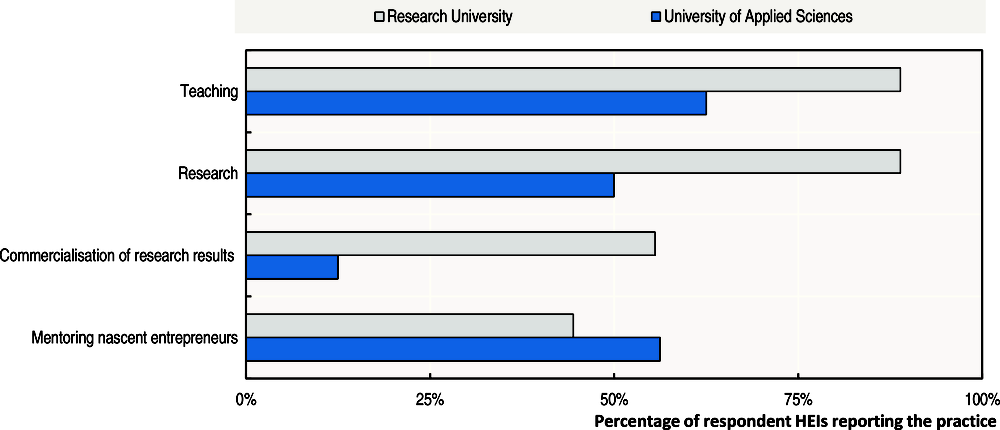

Incentives and rewards are given to staff who actively support the entrepreneurial agenda

Ensuring engagement of staff in valorisation activities requires resources, which ideally are made available on a long-term basis and are integrated into the wider resource development and incentive system. Individual HEIs reward excellent performance in teaching and research; this is more common for the surveyed research universities than the UAS. Less common are rewards for commercialisation of research results and mentoring of new entrepreneurs. The latter is more commonly practiced by UAS, but several of the surveyed HEIs reported that the introduction of such a practice was currently being discussed by their governing boards (Figure 2.5).

Figure 2.5. Rewarding excellent performance in Dutch higher education institutions

Notes: Higher education institutions (HEIs) were asked: “Are there formalised processes to identify and reward excellent performance in teaching?”, “Are there formalised processes to identify and reward excellent performance in research?”, “Does your HEI have an incentive system for staff, who actively support the commercialisation of research for example by making research results available, acting as mentors, etc.?”. The total number of responses was 25, of which 9 were from research universities and 16 from universities of applied sciences (UAS). The overall survey response rate was 48%. The survey response rates per HEI type are the following: research universities (60%), UAS (43%).

Source: OECD HEI Leader Survey The Netherlands (2016-17).

Supporting valorisation and entrepreneurship in higher education has led to the introduction of different staff profiles and several HEIs have undertaken initiatives to broaden the career paths for their academic staff to enhance more flexible mobility of staff between different areas of the HEI (e.g. policy advisors, business developers, etc.). These approaches offer valuable learnings; the examples of Erasmus University Rotterdam and the Amsterdam University of Applied Sciences are further discussed in Chapter 3.

Entrepreneurial teaching and learning

The HEI provides diverse formal learning opportunities to develop entrepreneurial mindsets and skills

Stimulating entrepreneurship plays an important role in Dutch higher education and entrepreneurship education is offered across the sector in various formats and across many disciplines. In all the HEIs visited for this report, there was clear evidence of the centrality of student development in the mission of the institutions and the desire to help students develop entrepreneurial mindsets and behaviours. Course modules and programmes in entrepreneurship commonly originated from the HEI’s business school. Increasingly these have been adapted and transferred into other disciplines and in some cases adopted across multiple disciplines within HEIs.

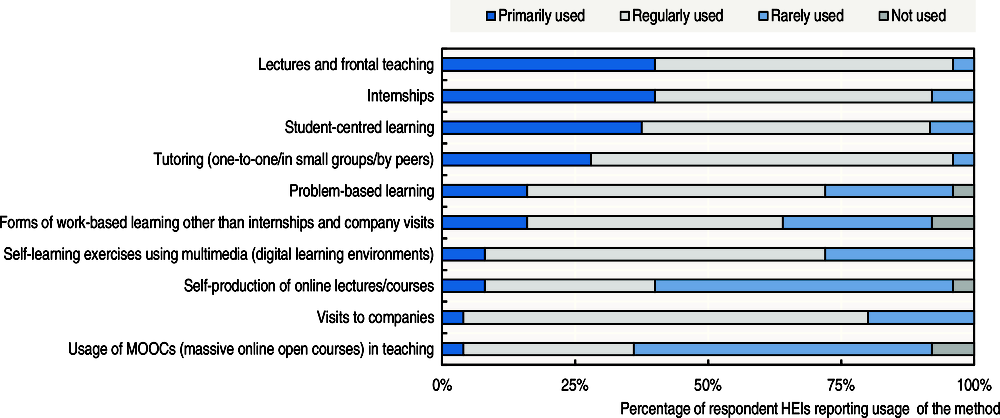

The HEI Leader Survey shows that the teaching and learning strategies in HEIs place significant emphasis on providing learners with greater exposure to real world experiences which promote entrepreneurial mindset and skills through internship programmes, student-centred learning, and tutoring (Figure 2.6). Methods used to deliver the programmes are also varied and include classroom delivery, one-to-one mentoring, peer mentoring and group work, use of live projects, case studies and hackathons. A wide range of teaching methods are used across the different study programmes, including problem-based learning, internships, visits to companies (more commonly practiced in UAS), tutoring, and self-learning exercises using digital learning environments. Less common are the self-production of online courses and lectures and the use of Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs).

Figure 2.6. Teaching methods in Dutch higher education

Notes: Higher education institutions (HEIs) were asked: “To what extent are the following teaching methods used at your HEI?”. Response options were “not used”, “rarely used”, “regularly used”, “primarily used”. The total number of responses was 25, of which 9 were from research universities and 16 from universities of applied sciences (UAS). The overall survey response rate was 48%. The survey response rates per HEI type are the following: research universities (60%), UAS (43%).

Source: OECD HEI Leader Survey The Netherlands (2016-17).

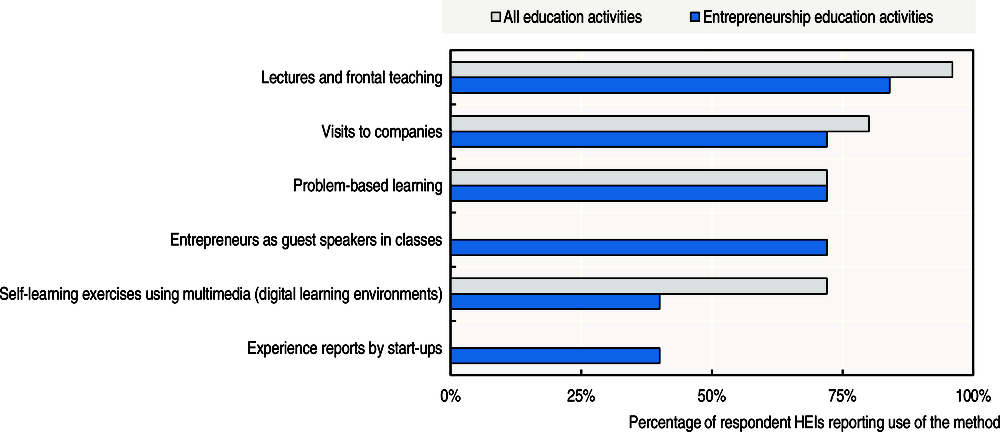

All but two of the surveyed HEIs offer entrepreneurship education activities, most of which are an integral part of the study programmes for all students. Looking more specifically at entrepreneurship education, lectures and frontal teaching are the most common teaching methods, followed by entrepreneurs as guest speakers in class, visits to companies and problem-based learning. Overall, not much difference can be noted when comparing the teaching approaches in entrepreneurship education activities with the teaching approaches in all education activities. Frontal teaching, visits to companies, and digital learning environments are less commonly practiced in entrepreneurship education activities. Experience reports by startups are common or regularly organised in 40% of the surveyed HEIs which currently offer entrepreneurship education activities (Figure 2.7). This could be increased as startups are relevant role models for would-be entrepreneurs.

Figure 2.7. Teaching methods in entrepreneurship courses in Dutch higher education

Notes: Higher education institutions (HEIs) were asked: “To what extent are the following teaching methods used at your HEI?” and “To what extent are the following teaching methods used in the entrepreneurship education activities currently offered at your HEI?”. Response options for both questions were “not used”, “rarely used”, “regularly used”, “primarily used”. Accumulated responses for “regularly used” and “primarily used” are shown. The total number of responses was 25, of which 9 were from research universities and 16 from universities of applied sciences (UAS). The overall survey response rate was 48%. The survey response rates per HEI type are the following: research universities (60%), UAS (43%).

Source: OECD HEI Leader Survey The Netherlands (2016-17).

An interesting example of problem-based learning is the B302 at Arnhem and Nijmegen University of Applied Sciences. B302 is a student-run company located on campus in which students “learn how to learn”, from tasks, from each other and from working with clients (see Chapter 4).

The HEI provides diverse informal learning opportunities and experiences to stimulate the development of entrepreneurial mindsets and skills

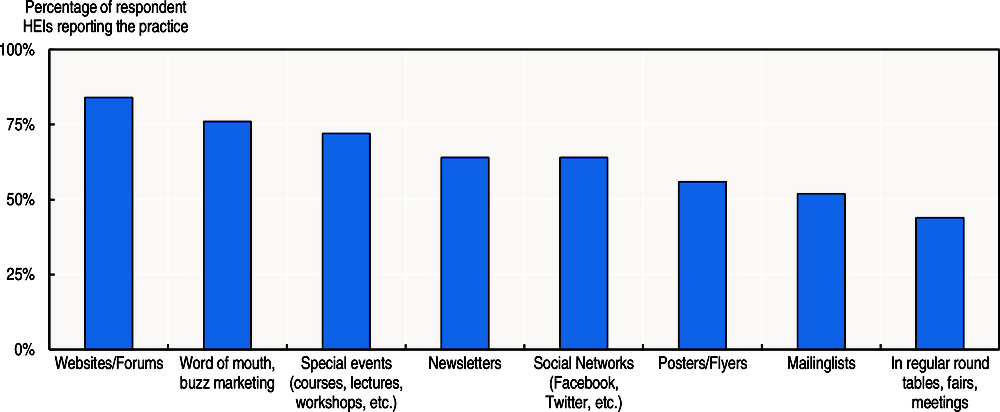

In addition to the aforementioned entrepreneurship education activities included in the study programmes, the surveyed Dutch HEIs also offer extra-curricular learning opportunities. A very popular informal learning method among students is to participate in student associations, which are well established in all Dutch HEIs. The HEI Leader Survey shows that the demand for informal learning opportunities has increased across nearly all surveyed HEIs. The HEIs have prepared the ground for this with a broad range of communication tools used to advertise extra-curricular education activities on entrepreneurship (Figure 2.8). Most common was the use of websites and word of mouth/buzz marketing. Approximately one-third use social networks and more than half of the surveyed HEIs communicate through posters, flyers and mailing lists. Less commonly used are regular events and fairs.

Figure 2.8. Advertising extra-curricular entrepreneurship activities in Dutch higher education

Notes: Higher education institutions (HEIs) that currently offer entrepreneurship education activities were asked: “How do you advertise the entrepreneurship education activities that are organised outside study curricula/programmes or open across faculties?”. The total number of responses was 25, of which 9 were from research universities and 16 from universities of applied sciences (UAS). The overall survey response rate was 48%. The survey response rates per HEI type are the following: research universities (60%), UAS (43%).

Source: OECD HEI Leader Survey The Netherlands (2016-17).

An example of a student-led initiative is the DesignLab at Twente University, which offers a physical location for the application of academic research (see Chapter 4). The slogan of the DesignLab is “Science2design4society” which reflects not only the DesignLab’s goal of providing opportunities for the design of valorisation activities by students based on academic learning and research, but also the ultimate goal of serving the broader community with those valorisation activities. Students sign up for the so-called “Dream Team”, which co-ordinates the DesignLab. As Dream Team members, students experientially acquire social, managerial, administrative and leadership skills.

The HEI validates entrepreneurial learning outcomes which drives the design and execution of the entrepreneurial curriculum

All but one of the surveyed HEIs which offer entrepreneurship education activities, also undertake formal evaluations. Where practiced, this is mostly an obligatory procedure. The focus is on satisfaction of participants (100%) and competence development (80%); half of the HEIs also measured the motivation of participants to start a business. In the majority of HEIs (70%) a specifically tailored survey instrument was used. When a questionnaire was used it was at the end of the course (100%), during the course (40%), and at a point of time after the course but before graduation (20%).

An interesting initiative of service-learning for local SMEs is De Rotterdamse Zaak (DRZ), which is aimed at entrepreneurs who are financially unable to find solutions to their problems. Students of Rotterdam University of Applied Sciences work closely together with entrepreneurs in difficulty. They learn to give advice on how to improve the business operations of these entrepreneurs – financially and commercially – and help to develop their entrepreneurial skills. The research team leading DRZ at Rotterdam University of Applied Sciences has undertaken various evaluations and regular monitoring of the learning outcomes of students and the impact on entrepreneurs and SMEs. Results are used to re-orient the teaching and overall course programme (see Chapter 4).

Exchange of experience is promoted at national level through the Festival of Entrepreneurial Learning (FOEL). The idea is that educators learn from each other, exchange experiences, share latest insights, new tools and programmes, and start joint activities. The FOEL festival was held for the first time in November 2016 with more than 200 participants. The intention is to organise the festival every year.

The HEI co-designs and delivers the curriculum with external stakeholders

Contact with external stakeholders in Dutch HEIs is primarily focused on improving the relevance and impact of education, R&D activities and engagement strategies, and occurs at all levels and across all units of the HEI. The HEIs also utilise the expertise of external stakeholders on a regular short term, part-time and occasional basis in their entrepreneurship education and startup support activities. Examples of this include the use of industry experts in course development and delivery and the involvement of entrepreneurs as student mentors.

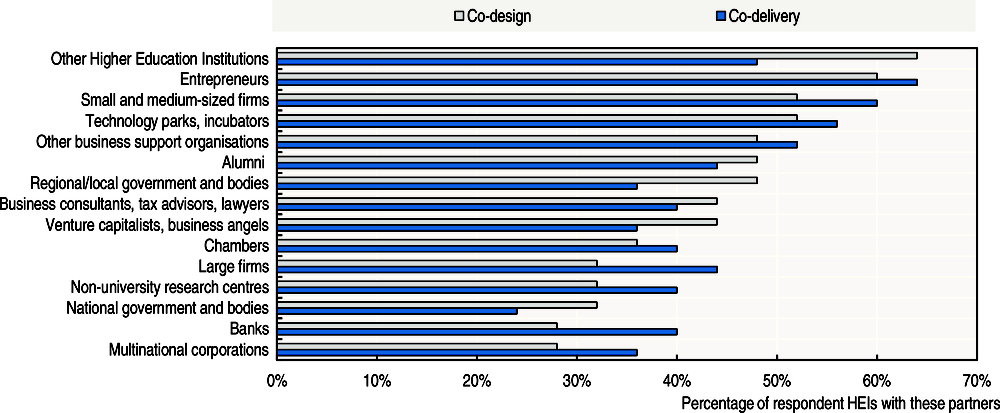

Figure 2.9 shows the extent to which the various stakeholders in higher education are engaged in entrepreneurship education activities. There is more involvement in the design of entrepreneurship education activities than in the delivery. For close to two-thirds of the surveyed HEIs key partners in the design of entrepreneurship education activities are other HEIs (64%), followed by entrepreneurs (60%), technology parks and incubators, and SMEs (52%). Less than one-third collaborate in the design phase with national government, public research centres, large firms, multinational corporations and banks. For the delivery of entrepreneurship education activities key partners are entrepreneurs (64%), SMEs (60%), and technology parks and incubators (56%). More than one-third of the surveyed HEIs involve banks and venture capitalists in their entrepreneurship education activities, and more than 40% collaborate with their alumni via entrepreneurship education activities. Technology parks and incubators, large firms and multinational corporations appear to collaborate more with the research universities than with the UAS in the sample.

Figure 2.9. Partners of Dutch higher education institutions for entrepreneurship education

Notes: Higher education institutions (HEIs) that currently offer entrepreneurship education activities were asked: “With which of the following organisations or individuals does your HEI collaborate regularly in the conceptual development of the entrepreneurship education activities?”, “With which of the following organisations or individuals does your HEI maintain regular collaboration with in the delivery of the entrepreneurship education activities?”. A total of 19 higher education institutions (8 research universities, 11 universities of applied sciences) responded to these questions. The overall survey response rate was 48%. The survey response rates per HEI type are the following: research universities (60%), UAS (43%).

Source: OECD HEI Leader Survey The Netherlands (2016-17).

A commonly practiced approach by the HEIs visited for this review is to invite local entrepreneurs and alumni to participate in entrepreneurship education activities on campus, including delivering guest lectures in courses and working with students on startup or consultancy projects. It is important that these activities are visible and accessible to students so that they can identify with them as role models. Celebrating successful student startups is important. These ventures are often easier for other students to identify with because these entrepreneurs are their peers. Successful student entrepreneurs could be featured at entrepreneurship events and even within entrepreneurship education.

Presentation of HEI-internal startup support programmes, and participation of individual staff members in international venture programmes and the local organisation of large entrepreneurship events (e.g. Get in the Ring) have been important in building powerful networks for new entrepreneurs and those providing entrepreneurship support in HEIs.

Results of entrepreneurship research are integrated into the entrepreneurial education offer

Many Dutch HEIs have leading European entrepreneurship researchers amongst their staff. Furthermore, there are several well-connected networks of entrepreneurship educators and of people working in the valorisation and entrepreneurship centres across the Netherlands. DARE, the Dutch Academy of Research in Entrepreneurship is an active research community of distinguished researchers on entrepreneurship, involving more than ten research universities and ten UAS (DARE, 2017). The Dutch Centres for Entrepreneurship which bring together several entrepreneurship centres and a strong student network (DutchCE, 2017), and the Nederlands Lectoren Platform Ondernemerschap, a national network of entrepreneurship lectors in the UAS (NLPO, 2017) also play an important role in integrating entrepreneurship research into the entrepreneurial education offer.

Preparing and supporting entrepreneurs

The HEI increases awareness of the value of entrepreneurship and stimulates the entrepreneurial intentions of students, graduates and staff to start up a business or venture

Students can choose from a variety of modules, courses and entire study programmes at bachelor’s and master’s levels. These activities are however, not always offered early on in study programmes (awareness raising), not for all students and not across all disciplines (interdisciplinary). It is important that students receive acknowledgement of the competencies acquired from entrepreneurship education activities (e.g. ECTS, diploma supplements). Some HEIs already offer this.

Communication is a priority and it is easy to find information about the entrepreneurial activities on the HEI’s websites; on average it takes three “clicks” to get up-to-date information on entrepreneurship courses, hackathons, incubation facilities, co-working spaces, and other startup support measures. Erasmus University Rotterdam is building on the approach to inspire followers through role models with the “I Will” initiative. Across campus, 15 000 large posters with “I Will” statements inspire students and staff to take initiative. Started by the Rotterdam School of Management (RSM) the aim is to visualise the power of a diverse community of international students, faculties, alumni, business leaders and staff and the bond of the unifying commitment to make business a force for positive change (RSM, 2017). The excellent design and great visibility of the “I Will” statements clearly show that the effectiveness of such campaigns depends on visibility and accessibility.

It is not easy for students to manage the requirements of a full-time study programme and pursue a “startup dream” at the same time. There are already good examples of how HEIs support these students, for example by making it possible for them to partially or fully focus their graduation thesis on a research question that is related to a/their startup. For example, the Amsterdam University of Applied Sciences offers students the possibility to write their bachelor graduation thesis on a research question related to their startup. As discussed in Chapter 4, this is an approach that could be used in more HEIs.

The adoption of rules and regulations concerning the use of trademarks and for the commercialisation of research results was more common for research universities (67% and 100% respectively) than for UAS (13% and 44%). Approximately 80% of the surveyed research universities and around 20% of the UAS were, at the time of the survey, shareholders in firms founded by staff or students.

The HEI supports its students, graduates and staff to move from idea generation to business creation

Supporting startups is well-established in Dutch higher education, both in terms of entrepreneurial mindset development through educational activities, and in supporting would-be entrepreneurs in their first steps to create a new venture. The majority of research universities and most of the UAS have established rich support infrastructures with co-working and incubation facilities on campus, and startup training and mentoring by staff and experienced entrepreneurs. These facilities and services are not always accessible to alumni.

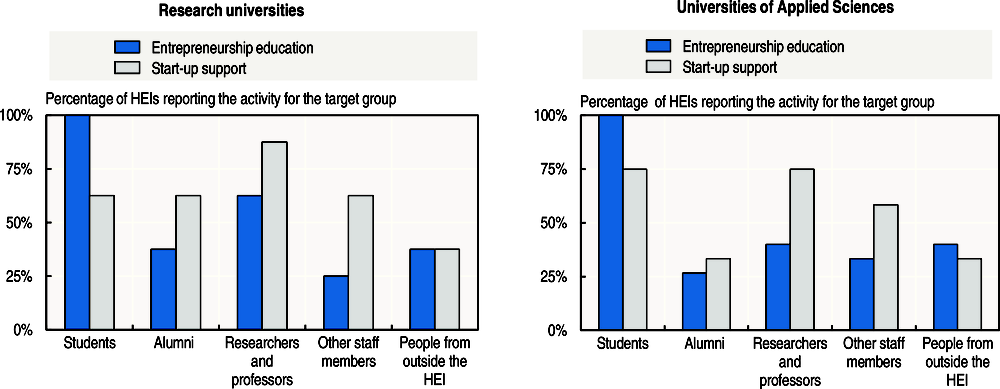

Comparing the current offer of entrepreneurship education activities with the startup support measures, there appears to be a gap for students in terms of startup support. While students are the number one target for entrepreneurship education activities in both research universities and UAS, overall startup support is more oriented towards researchers, professors, other staff members, alumni and people from outside the HEI (Figure 2.10). This gap is less obvious in the surveyed UAS. Across the Dutch higher education sector, researchers, professors and other HEI staff members seem to have less access to entrepreneurship education activities than to startup support. This might be a missed opportunity, as such activities, particularly if organised in a highly creative context, often provide a fertile ground for idea generation and startup team building.

Figure 2.10. Target groups for entrepreneurship support in Dutch higher education institutions

Notes: Higher education institutions (HEIs) that currently offer entrepreneurship education activities were asked: “Which of the following are target groups for the entrepreneurship education activities?” A total of 23 higher education institutions (8 research universities, 15 universities of applied sciences), responded to the question. HEIs that currently offer startup support were asked “Which of the following are target groups for the startup support measures offered at your HEI?”. A total of 20 higher education institutions (8 research universities, 12 universities of applied sciences) responded to these questions. The overall survey response rate was 48%. The survey response rates per HEI type are the following: research universities (60%), UAS (43%).

Source: OECD HEI Leader Survey The Netherlands (2016-17).

Business incubation programmes and facilities are available in all the visited HEIs and are available to both students and staff. Some have obtained international recognition, such as YES Delft and Utrecht Inc., which ranked amongst the top six in the 2015 European ranking of University Business Incubators. Ideally, such support is available for all interested students, regardless of their area of study. There are benefits to scaling the offer across departments and across different HEIs, providing would-be entrepreneurs with the possibility to participate in startup programmes outside their core area of studies/research, and allowing them to work with and be inspired by others (Chapter 6).

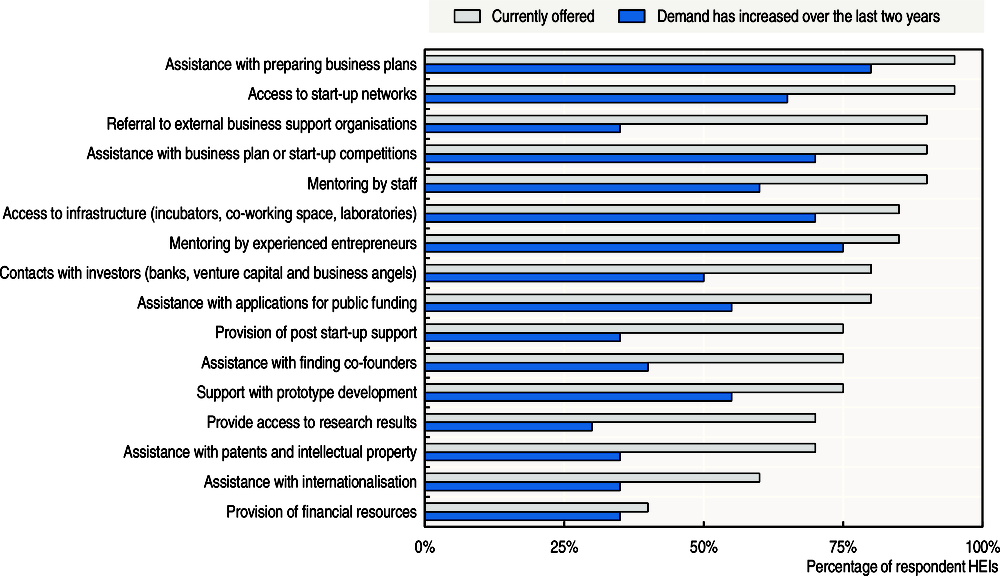

All of the surveyed HEIs offer a wide range of startup support measures (Figure 2.11). Most common were assistance with the preparation of business plans, access to startup networks, mentoring by staff, assistance with business plan competitions, and referral to business support organisations. Less common, but still practiced by 60% of the surveyed HEIs, is assistance with internationalisation; 40% reported to provide financial resources for startups, whereas 80% facilitate contacts with investors (e.g. banks, venture capital providers and business angels), and assist founders with applications for public funding. More than half of the HEIs reported an increased demand for several startup support measures over the last two years. Top of the list were assistance with the preparation of business plans (80%) and mentoring by experienced entrepreneurs (75%). Also, access to infrastructure, that is, incubators, co-working spaces and laboratories and mentoring by HEI staff members were increasingly demanded in more than two-third of the surveyed HEIs.

Figure 2.11. Offer and demand for startup support measures in Dutch higher education institutions

Notes: Higher education institutions (HEIs) that currently offer startup support were asked: “You’ve stated earlier that your HEI currently offers special support measures for individuals or teams, who are interested in starting-up a business. What special support measures are currently offered?”, “How has the demand for the special support measures developed over the last two years?”. A total of 20 higher education institutions (8 research universities, 12 universities of applied sciences) responded to these questions. The overall survey response rate was 48%. The survey response rates per HEI type are the following: research universities (60%), UAS (43%).

Source: OECD HEI Leader Survey The Netherlands (2016-17).

Training is offered to assist students, graduates and staff in starting, running and growing a business

Startup training courses, offered as part of the entrepreneurship education activities, provide relevant knowledge on financing, legal and regulatory issues, and human resource management. HEIs in the Netherlands offer training to assist students, graduates and staff in starting, running and growing a business as part of the entrepreneurship education activities and through the incubation facilities. Soft skills, which are very important to effectively marshal resources and handle the startup process, are often acquired through extracurricular activities.

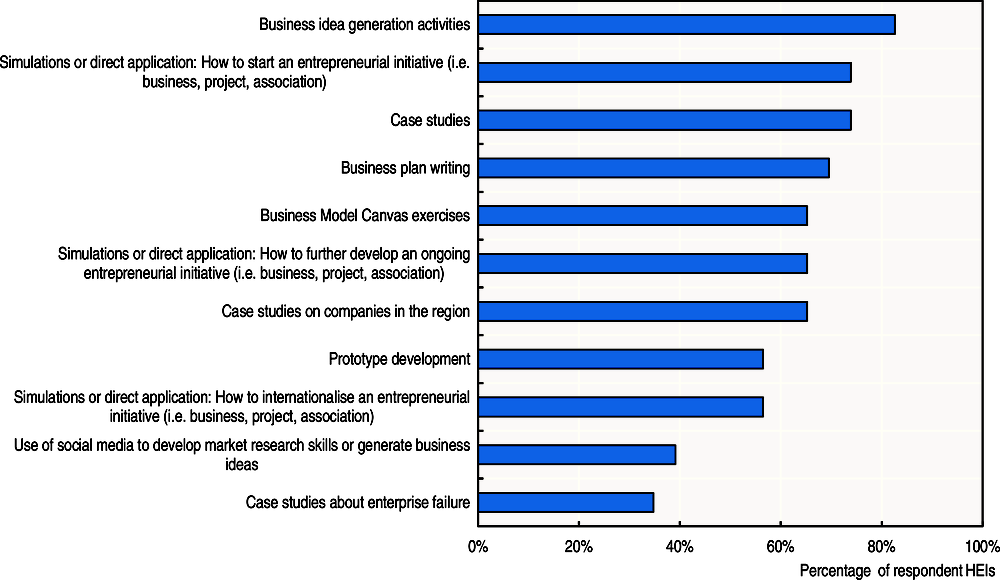

The HEI Leader Survey shows the most practiced training methods in education activities are case studies, business idea generation activities, business plan writing, and simulations or direct applications of how to start up a business or further develop an entrepreneurial initiative (Figure 2.12). Less practiced, but still common to more than half of the surveyed HEIs, are prototype development, case studies on companies in the region, exercises using the Business Model Canvas methodology, and case studies on company failure. Least practiced were simulations or direct applications of how to internationalise an entrepreneurial initiative.

Figure 2.12. Startup training offer in Dutch higher education institutions

Notes: Higher education institutions (HEIs) that currently offer entrepreneurship education activities were asked: “To what extent are the following teaching methods currently used in the entrepreneurship education activities at your HEI?” The total number of responses was 23, of which 8 were from research universities and 15 from universities of applied sciences. The overall survey response rate was 48%. The survey response rates per HEI type are the following: research universities (60%), UAS (43%).

Source: OECD HEI Leader Survey The Netherlands (2016-17).

Mentoring and other forms of personal development are offered by experienced individuals from academia or industry

Almost all HEIs reported that they offered mentoring by staff and slightly less offered mentoring by experienced entrepreneurs (Figure 2.11). Demand for mentoring has increased over the last two years, more for entrepreneurs (88%) than for staff members (67%). Half of the surveyed HEIs reported that mentoring nascent entrepreneurs was recognised along with other outstanding achievements in areas other than research and teaching.

The HEI facilitates access to financing for its entrepreneurs

The HEIs reported that they offer a range of measures to facilitate access to finance (Figure 2.11). 80% provide assistance with applications for public funding and facilitate contacts with potential investors, and 40% of the HEIs provide financial resources.

An interesting example of facilitating and providing access to finance for new entrepreneurs is the Dutch Student Investment Fund, founded in 2016 at Twente University.

Box 2.2. Dutch Student Investment Fund

The Dutch Student Investment Fund, founded in 2016 at Twente University, is one of the first student investment fund in Europe. The fund is not only provided for students, it is also managed by students. It seems risky to let students handle huge amounts of money, but the University leadership believes that this is a great learning experience for students. The fund is managed day to day by a board consisting of four students who are supervised by three business professionals with experience in investing. DSIF invests up to EUR 50 000 in startups created by bachelor’s, master’s, or PhD students from either the UT or Saxion, or students that have graduated a maximum of 12 months previously.

The Dutch Student Investment Fund is looking for ambitious startups that aim for growth. Deliberately, there is no sector-specific focus; the intention is to be accessible for all student entrepreneurs aiming to grow their ideas into viable businesses. As long as the team of entrepreneurs is strong, the product or service has a lot of potential, and the business model is sound, the Dutch Student Investment Fund will get involved.

Source: Interviews at Twente following the study visit in June 2016.

The HEI offers or facilitates access to business incubation

All surveyed research universities and 75% of the UAS offer business incubation facilities on campus. More than 70% of the incubators offer free or subsidised temporary rental, tenants have access to the HEI’s laboratories and research facilities, and can use the HEI’s information technology services. Also commonly offered are coaching and training, and facilitation in accessing financing, but less than half of the incubators offer help with internationalisation. New entrepreneurs, who do not belong to the HEI, can access the incubators. This practice is more common for research universities (75%) than for UAS (45%).

Knowledge exchange and collaboration

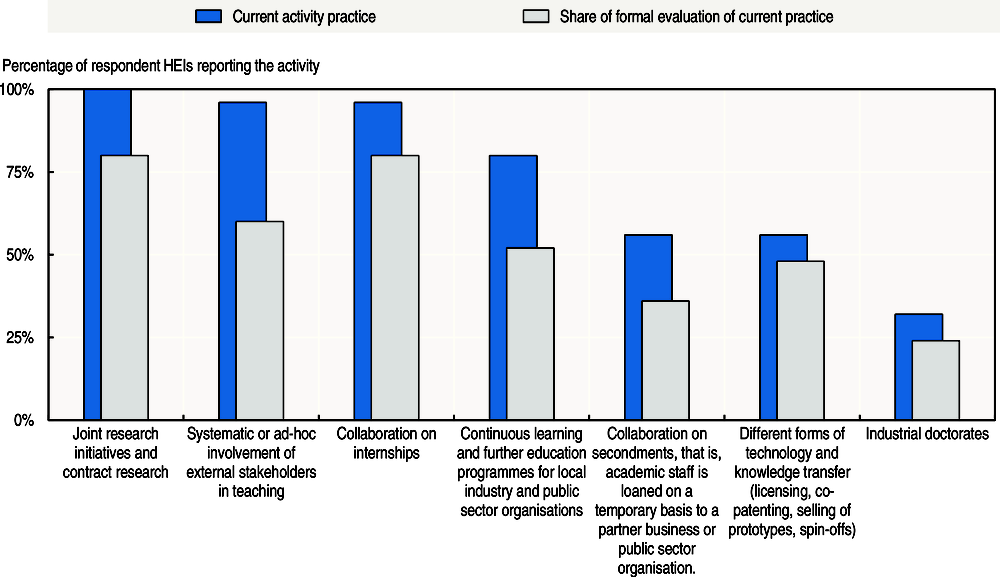

The HEI is committed to collaboration and knowledge exchange with industry, the public sector and society

Valorisation is a key mission pillar for HEIs in the Netherlands. All of the HEIs visited demonstrated active involvement in partnerships and relationships with a wide range of stakeholders. This includes, for example, active participation and involvement with local, regional and national organisations, such as county development boards, local and regional authorities, business and industry representative groups, chambers of commerce, professional bodies and state boards.

Maastricht, one of the most international universities in the Netherlands, has a strong regional responsibility and commitment to make a difference by joining forces with the region’s industrial players. The result of this is Brightlands, a vibrant knowledge network with four campuses spread throughout the Limburg region: smart materials and sustainable manufacturing; regenerative medicine, precision medicine and innovative diagnostics; data science and smart services; and Food and nutrition. Brightlands is grounded on a strong Triple Helix involving education/research, industry and government with shared resources. The collaboration between the university and the regional government is very strong and has served as a learning model for other regions in the Netherlands and abroad (Brightlands, 2017). The co-location of fundamental and applied research has attracted new research groups to move to Limburg. This has jump-started research efforts and provided new ways of involving students in research. It requires an alternative mindset to spread amongst university administrators, scientists and students, which could be seen as a natural next step following the problem-based learning for which Maastricht University has become known worldwide.

The HEI demonstrates active involvement in partnerships and relationships with a wide range of stakeholders

External stakeholders interviewed as part of the review process all expressed the view that HEI participation in networks and partnerships was essential to the operation of these groups given the strength and range of expertise the HEIs had at their disposal. There are several examples of how researchers in HEIs have helped firms, civil society organisations and local authorities to scale up their innovation activities.

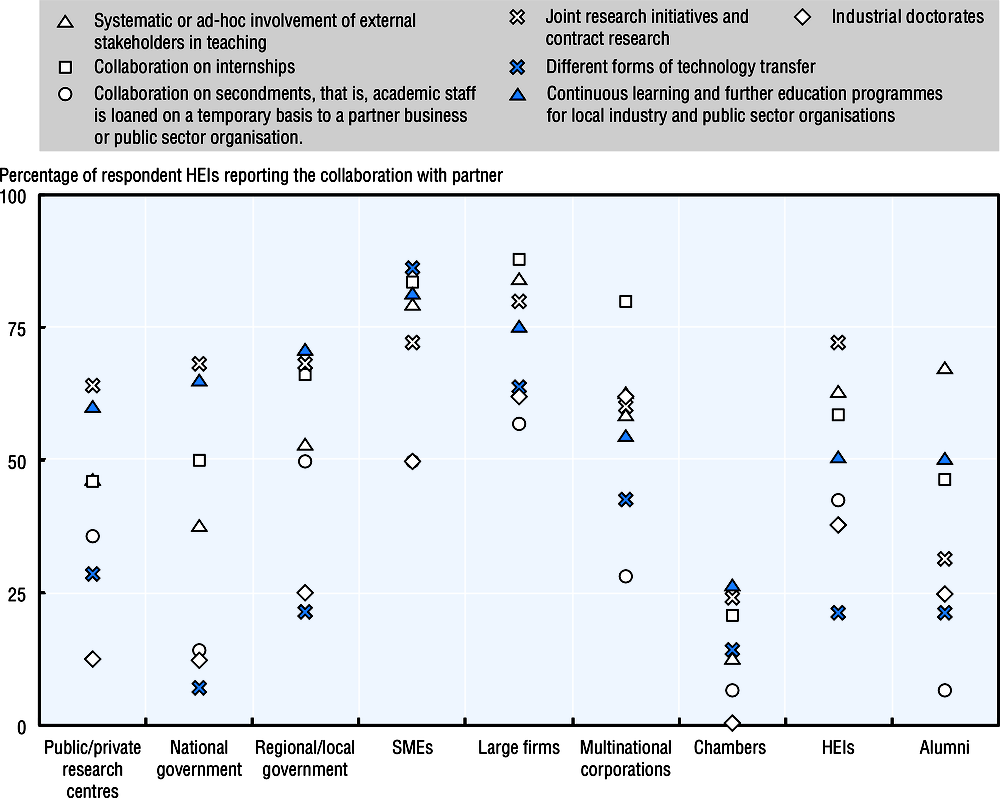

The results of the HEI Leader Survey show the range of knowledge exchange practices and partners of HEIs (Figure 2.13). With regard to ad hoc or systematic involvement of external stakeholders in teaching, most common were partnerships with large firms, SMEs and alumni. Key partners for the organisation of internships are large firms, SMEs and multinational corporations. Similar patterns can be observed for different forms of technology and knowledge transfer and industrial doctorate programmes. Temporary mobility schemes of academic staff (i.e. secondments) are organised mainly with large firms, regional government and SMEs. Lifelong learning programmes are organised for, and with, a variety of organisations, most commonly with SMEs, large firms and regional/local governments. Key partners for joint research initiatives and contract research include SMEs, large companies and other HEIs. Overall, the most common knowledge partners of Dutch HEIs are SMEs (92%), large firms (88%), regional and local governments (84%) and other HEIs (84%). Less common were knowledge partnerships with Chambers (44%). Larger HEIs in the sample had more collaboration with public/private research centres, regional/local governments and SMEs, and research universities had more partnerships with multinational corporations than the UAS in the sample.

Figure 2.13. Partners of Dutch higher education institutions in knowledge exchange activities

Notes: Higher education institutions (HEIs) were asked: “Knowledge exchange can take on various forms. The focus can be on teaching, research or any form of strategic collaboration. Which of the following are currently practiced at your HEI?”; “Which of the following are currently knowledge exchange partners of your HEI?”. The total number of responses was 25, of which 9 were from research universities and 16 from universities of applied sciences (UAS). The HEIs reported to have knowledge exchange relationships with public/private research centres (19, 76%), national government (20, 80%), regional/local government (21, 84%), SMEs (23, 92%), large firms (22, 88%), multinational corporations (20, 80%), Chambers (11, 44%), other HEIs (21, 84%), alumni (19, 76%). The overall survey response rate was 48%. The survey response rates per HEI type are the following: research universities (60%), UAS (43%).

Source: OECD HEI Leader Survey The Netherlands (2016-17).

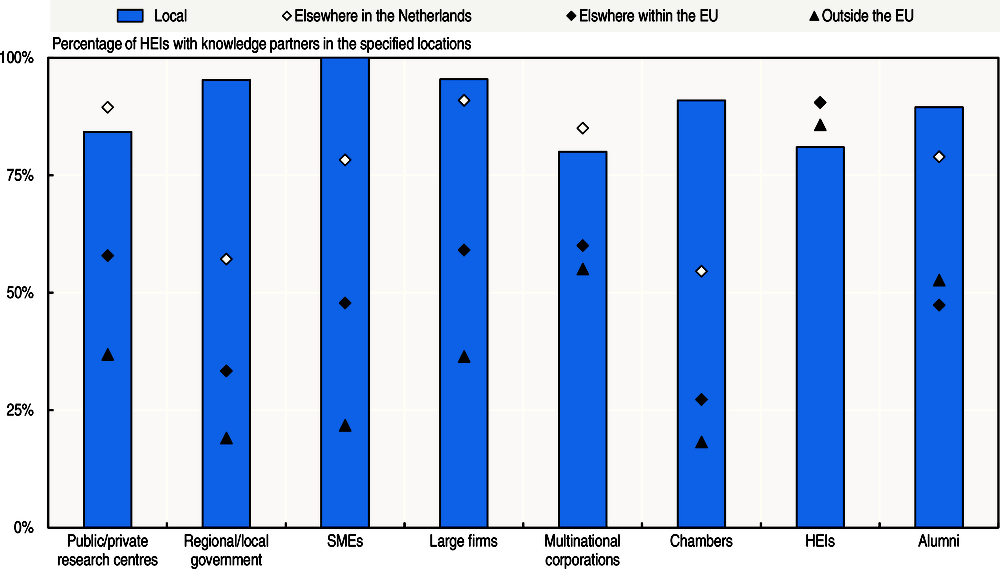

The geographic radius of knowledge exchange partners is large for the surveyed HEIs and included local contacts, as well as relationships with organisations located elsewhere in the Netherlands and within and outside the EU (Figure 2.14). Contacts with public/private research centres were both within their local area, and elsewhere in the country, as well as within the wider EU area (58%) and beyond (37%). Relationships with other HEIs occur at all levels of geographic distance and they account for close to 90% of the HEIs’ links with partners outside the EU, followed by multinational corporations (55%) and alumni (53%). Collaboration with regional/local governments is focused on the close proximity to the HEI although 57% of the respondents also collaborate with these organisations elsewhere in the country. All of the surveyed HEIs have relationships with SMEs in the local economy and close to 80% with SMEs located elsewhere in the country. For close to half of the HEIs these relationships also cover the wider EU area, and 22% have global contacts with SMEs. Partners from large firms and multinational corporations are locally concentrated and spread across the Netherlands. Contacts with Chambers are mainly national; only 55% collaborate with the local Chamber organisations, taking into account that Chambers in general are one of the less common knowledge partners of HEIs. Knowledge exchange partnerships with alumni are mainly across the country but also have global scope (47%).

Figure 2.14. Location of knowledge exchange partners of Dutch higher education institutions

Notes: Higher education institutions (HEIs) were asked: “Where are current knowledge exchange partners of your HEI located?”. The total number of responses was 25, of which 9 were from research universities and 16 from universities of applied sciences (UAS). All HEIs reported to have knowledge exchange relationships with local partners (25, 100%), elsewhere in the country (23, 91%), elsewhere within the European Union (23, 90%), outside the European Union (21, 86%). The overall survey response rate was 48%. The survey response rates per HEI type are the following: research universities (60%), UAS (43%).

Source: OECD HEI Leader Survey The Netherlands (2016-17).

The HEI has strong links with incubators, science parks and other external initiatives

Of the surveyed HEIs that currently offer startup support, all of the research universities and 75% of the UAS have a business incubator on campus. Almost one-third have a representative of a technology park as a member of the HEI’s governing body and more than two-thirds collaborate with technology parks and incubators on their entrepreneurship support, and on the design and delivery of entrepreneurship support activities (Figure 2.9). In 70% of the surveyed HEIs the demand for incubation facilities has increased over the last two years.

The HEI provides opportunities for staff and students to take part in innovative activities with business and the external environment

Opportunities exist to support staff and student mobility between academia and the external environment. Internships are a common practice to offer students the opportunity to participate in innovative activities with the external environment. More than two-thirds of the HEIs offer internships for their students; 72% have mandatory internships across most of their programmes at bachelor’s level, 44% at master’s level, and 20% for doctoral study programmes. More than 70% offer students support for the organisation of internships, which includes, in order of current practice: access to information on internship opportunities (94%), continuous support during mobility (89%), financial support (67%), and incentives for students to share their experiences with other students afterwards (50%).

Fewer initiatives exist to support the temporary mobility of HEI staff into industry and public organisations. Current practice was reported by half of the surveyed HEIs and a further two HEIs indicated that the introduction of secondment schemes is being considered by their governing boards. The support offered, in order of current practice, includes: information on mobility opportunities (93%), continuous support during mobility (86%), incentives for staff to share their experiences after mobility (79%), and funding (57%).

The HEI integrates research, education and industry (wider community) activities to exploit new knowledge

There are several examples of projects where HEIs bring together research, education and the business community. They will be discussed in Chapter 4, Chapter 5 and Chapter 6. One example that stands out is The Hague University of Applied Sciences and its Research Unit for Financial Inclusion and New Entrepreneurship. The Research Unit is very proactive in engaging with students. The research publications involve collaboration with the student community and are active educational projects. A key educational aim of the Research Unit is to support students to learn and understand more about value creation in a changing economy, related new forms of entrepreneurship and a new type of IT-based and self-controlled financing (HEInnovate 2017c).

The internationalised institution

Internationalisation is an integral part of the HEI’s entrepreneurial agenda

The international strategies of HEIs in all areas, including student recruitment, exchange and placement activities; research and development; and staff mobility and recruitment, are firmly rooted and have evolved largely from the HEIs’ active participation in international networks. The HEI Leader Survey confirms this: 90% of the surveyed HEIs have knowledge exchange partners from across the European Union, and more than 86% have global relationships (Figure 2.14).

All HEIs visited presented strong and ambitious international strategies of an entrepreneurial nature, which are largely focused on income generation from international student recruitment and participation in international education and R&D initiatives.

In 2016, 15.9% of the entire student population registered in government funded HEIs in the Netherlands had completed the prerequisite studies abroad and were not Dutch citizens. Most foreign students come from EU countries; Germany is by far the most common country of origin. China constitutes the largest group of non-EU international students (VSNU, 2017c). The growing number of students and staff from abroad is an excellent opportunity to enrich the academic entrepreneurship scene and should be taken into account more broadly.

The Dutch HEIs set their own internationalisation agenda and strategies based on their institutional profile. The representative umbrella organisations of the UAS and the research organisations advocate for a greater orientation of these individual strategies with the two national branding initiatives, “Nederland kennisland” (Netherlands, knowledge economy) and the “Holland” branding. These underline the key strengths of Dutch higher education, namely the very broad range of English taught programmes at all levels (bachelor’s, master’s, PhDs), study programmes that focus on global challenges, and a teaching and research culture in which freedom of expression, intellectual independence, curiosity, and the right to question are paramount (VH/VSNU, 2014).

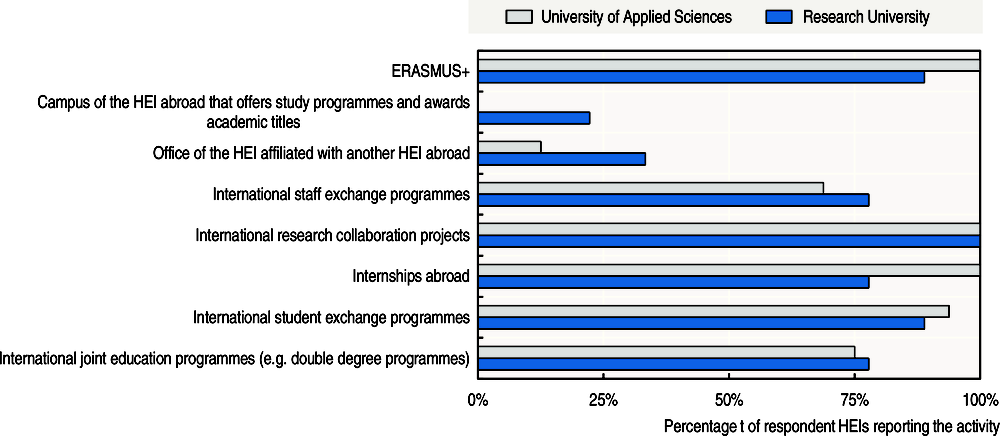

The HEI explicitly supports the international mobility of its staff and students

Common internationalisation practices of Dutch HEIs include collaboration within Erasmus+ (part of the European Region Action Scheme for the Mobility of University Students), international student exchange programmes and student internships abroad, international research collaboration, and joint international education programmes (e.g. double degree programmes). The practices of either having offices affiliated with another HEI abroad, or their own campus abroad were uncommon and reported mostly by the research universities (Figure 2.15).

Figure 2.15. Internationalisation activities of Dutch higher education institutions

Notes: Higher education institutions (HEIs) were asked to report on their current internationalisation activities. The total number of responses was 25, of which 9 were from research universities and 16 from universities of applied sciences. The overall survey response rate was 48%. The survey response rates per HEI type are the following: research universities (60%), universities of applied sciences (43%).

Source: OECD HEI Leader Survey The Netherlands (2016-17).

The HEI seeks and attracts international and entrepreneurial staff

Dutch HEIs are attractive employers for researchers and academic staff members from abroad. The internationalisation of staffing has gained momentum over the past few years, with HEIs increasingly competing internationally to attract talents. 60% of the surveyed HEIs reported to have recruitment policies and practices that seek to attract international staff; this included 89% of the surveyed research universities and 44% of the UAS. More than half of the surveyed HEIs reported to recruit staff for their entrepreneurship support activities.

The percentage share of non-Dutch nationals in research staff is highest for PhD candidates with above 45% and a 10% increase for the period 2006-16, and lowest for full professors at approximately 16% with a less than 3% increase since 2016 (VSNU, 2017b).

The international dimension is reflected in the HEI’s approach to teaching

All HEIs visited have a teaching and learning environment tailored to a more global audience and provide access to new ideas for teaching and learning in the international environment. This increases the HEI’s ability to compete on the international market and orients students to globalised job markets. A good example of how to stimulate internationalisation in higher education teaching and learning is the International Classroom at the University of Maastricht, which is a holistic approach to teaching and learning involving both students and staff in promoting a culture of inclusion and respect and preparing students for the global labour market through support activities that develop intercultural communication skills, coaching skills and conflict management (EDLAB, 2017).

International service-learning has also become a common practice for many Dutch HEIs. An example is the Theewaterskloof Programme, an initiative of the Arnhem and Nijmegen University of Applied Sciences with two South African universities (Box 2.3).

Box 2.3. Theewaterskloof Programme: international service-learning in practice

The Theewaterskloof programme is an international community development project based in the Theewaterskloof Municipality in the Western Cape province of South Africa. The original impulse behind the programme came from the observation that, in order to respond to the increasing slumification of South African towns and cities, it was necessary to develop rural regions.

The programme, part of a network of wider activities and initiatives, is made up of a consortium of six organisations in the Netherlands and South Africa: two South African universities, Western Cape University (historically black) and Cape Peninsula University of Technology; Theewaterskloof Municipality; the South Africal Netherlands Chamber of Commerce, CoCreateSA; Elgin Learning Foundation; and the University of Applied Sciences Arnhem and Nijmegen (HAN). Specific challenges were identified in the municipality (food insecurity, HIV/AIDS, unemployment, low levels of literacy, weak entrepreneurial culture, skills shortage, etc.), and the programme was intended to deliver a sustainable contribution to social, as well as economic development, significantly through the community having ownership over the programme, and skills transfer to the community in order to build capacity to that end.

The programme takes a service-learning approach to rural community development, something the HAN participants learned from their South African partners. This methodology, which is more common in the south, combines community service with more structured academic learning, where students “give something back” to society during their education. By engaging directly with complex social issues, students learn about the connection between their field of study and the kinds of problems and issues it can be used to engage with in a community. 1 500 students have participated in this programme since its inception in 2004, of which 600 were HAN students, with the remainder from Western Cape University and Cape Peninsula University of Technology. An awareness of the importance of tacit knowledge encourages students to step outside a European or Dutch mindset in order to engage with the Theewaterskloof community. Projects in the Theewaterskloof programme have focused on food gardens, waste management, arts and crafts centres, tourism and leisure promotion, “Sports for all & Train the trainer”, and architecture in the Dutch Cape style. Of the 600 HAN students involved, the majority have come from health, social work and sport, with a smaller number from education, business and engineering.

HAN’s involvement is in terms of training and skills transfer, while the content of the programme is taken care of by the South African partners. The role of HAN’s students is that they are not there to bring in money, but to bring in skills and capacity building. In terms of how funding is structured, the programme costs EUR 140 000 a year, which is a 0.4 time position in HAN, and four full-time staff in South Africa. Various costs, such as minibuses etc., are overheads coming out of this funding, but students pay their own way for travel, food, and accommodation. The funding is not simply recurrent, however. By not looking for large EU-levels of money, but by being required to reapply to HAN for funding, this brings commitment from HAN, keeping the idea and impulse behind the programme fresh in the mind of management. The Theewaterskloof programme is a valuable resource for those interested in social entrepreneurship, and brings significant innovation in moving beyond the traditional social justice model of international development and engagement education.

Source: Interviews at the Arnhem and Nijmegen University of Applied Sciences visit in July 2016.

In entrepreneurship education courses and startup training, simulation of direct application of how to internationalise an entrepreneurial initiative (i.e. business, project and association) was a regularly or primarily used teaching method in 57% of the surveyed HEIs.

The international dimension is reflected in the HEI’s approach to research

Many HEIs are part of various international research networks with reach beyond the EU. More than 80% of the surveyed HEIs have knowledge exchange relationships with HEIs in the wider EU area, and 50% also with HEIs globally. Collaboration with public/private research organisations located elsewhere in the EU was practiced by 60% of the surveyed HEIs, and close to one-third collaborated with research organisations globally.

Measuring impact

The HEI regularly assesses the impact of its entrepreneurial agenda

A central element of the entrepreneurial agenda of Dutch HEIs is the valorisation of knowledge, that is, creating value for economic and/or societal use by translating knowledge into useful products, services, processes and entrepreneurial activity (see Chapter 1). Valorisation encompasses all disciplines, and the impact of valorisation goes well beyond economic aspects into generating societal and cultural value.

From 2005 onwards, HEIs have included valorisation in their strategic plans as a function in addition to, and in synergy with, education and research. For the universities of applied sciences, the emphasis on valorisation has brought new attention and specific support to strengthen research activities. The focus on valorisation of knowledge has successfully introduced a wider understanding amongst the Dutch HEIs and individual researchers of impact in terms of education, research, engagement and networks, and in terms of academic and non-academic results inside and outside the HEI.

Impact is generated through non-linear processes, which are multi-iterative, parallel, multidimensional, absorptive and combine push and pull factors. Impact is not just about individual endeavours but is systemic, taking into account how individual actions related to past, current and future activities at departmental, faculty and institutional levels. Generation and diffusion of impact needs supportive and flexible structures, communication infrastructure and skilled people. Communication is particularly important as impact related information is both qualitative and quantitative, it can be fuzzy in its nature, and it is spread over time and different sources.