This chapter presents the country profile for Malaysia. It provides an overview of the current de jure requirements for the institutions, tools and processes of regulatory governance and, where possible, how these have been implemented in practice. The profile focus on three aspects of regulatory governance pertinent to the past, present and near future of regulatory reforms in the ASEAN region. The first is whole-of-government approaches to regulatory policy making, including national and international commitments to better regulation that are driving domestic reform processes. The second is the use of good regulatory practices, including regulatory impact assessments (RIAs), stakeholder engagement and ex post review. The third is approaches to digitalisation, or how countries are using digital tools to respond to regulatory challenges, and is the newest frontier for better regulation reforms in both ASEAN and OECD communities. The information contained in this and the other profiles serves as the basis for the analysis of trends in regulatory reform presented in Chapter 1.

Supporting Regulatory Reforms in Southeast Asia

7. Malaysia

Abstract

Whole-of-government initiatives

Regional focus

Since 2018, Malaysia has continued improve its regulatory environment by participating in trade agreements that include provisions promoting better regulation. Malaysia is a signatory to the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement (RCEP), which came into force as of 18 March 2022 (Bernama, 2022[1]). Malaysia signed the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) but has not ratified it as of January 2022. In addition to tariff cuts, the CPTPP contains provisions on, among others, customs and trade facilitation; standards and technical barriers to trade; investment; services; intellectual property; e-commerce; procurement; labour; environmental issues; regulatory coherence; and others (OECD, 2021[2]). Malaysia is also involved in regional initiatives promoting good regulatory practices (GRPs). One such initiative is the ASEAN Regulatory Cooperation Project (ARCP), which addresses non-tariff barriers due to divergence of chemical management regulations by encouraging regulatory co-operation and convergence. ARCP helps to establish regulatory environments that encourages free and open trade and investment while protecting human health, safety, environment and security (APEC, 2020[3]).

Malaysia’s National Single Window has been in operation since 2009 and Malaysia has taken many steps to integrate it into the ASEAN Single Window (ASW). Malaysia joined the ASW Live Operation in 2019, which allowed the granting of preferential tariff treatment based on the ASEAN Trade in Goods Agreement electronic Certificate of Origin (ATIGA e-Form D) exchanged through the ASW (n.d.[4]). Moreover, Malaysia began the exchange of the ASEAN Customs Declaration Document (ACDD) through the ASW in 2021.

Malaysia has expressed that (GRPs) are consistently mentioned in treaty agreements, as it not only heightens trust among trading partners, but also corresponds to principles of good governance, transparency, productivity and accountability. The Government of Malaysia has also routinely asked their ministries, agencies and local authorities to publish their guideline in the issuance of permit and licensing through online so that they can manage and reduce the likelihood of corruption. MPC received mandate from the Special Cabinet Committee on Anti-Corruption (JKKMAR) to facilitate the process in ensuring the ministries and government agencies responsible for issuing licences and permits publish guidelines online for the public information. This initiative is under the strategies highlighted in the National Anti-Corruption Plan (NACP) 2019-2023 which is to establish a strong and effective mechanism in the issuance of permits and licensing in Malaysia

National focus

Malaysia is a regional leader in promoting regulatory policy that aligns with international good practice. The launch of the National Policy on the Development and Implementation of Regulations (NPDIR) in 2013 marked a change in the government’s approach to regulatory reform, from deregulation to a whole-of-government approach on GRPs (ERIA, 2020[5]).

Regulatory reform

The Shared Prosperity Vision (SPV) as the country's new direction was announced by the Prime Minister during the tabling of the Mid-Term Review of the Eleventh Malaysia Plan (MTR 11MP) in October 2018 in Parliament (Ministry of Economic Affairs, 2019[6]). Shared Prosperity Vision 2030 is a commitment to make Malaysia a nation that achieves sustainable growth as well as fair and equitable distribution across income groups, ethnicities and supply chains (Ministry of Economic Affairs, 2019[6]). Integrity and Good Governance is the thirteenth guiding principle of the vision. This principle emphasises the outcomes of 1) elevating the credibility of the legal system in tandem with social change; 2) strengthening accountability and integrity; and improving the rakyat1’s perception towards public administration (Ministry of Economic Affairs, 2019[6]).

The Prime Minister presented the Twelfth Malaysia Plan (12MP) as a development roadmap from 2021 to 2025. The 12MP is anchored on three key themes focusing on resetting the economy, strengthening security, wellbeing and inclusivity as well as advancing sustainability (Economic Planning Unit, Prime Minister's Department, 2021[7]). These themes are supported by four catalytic policy enablers focusing on developing future talent, accelerating technology adoption and innovation, enhancing connectivity and transport infrastructure as well as strengthening the public service, paving the way for a prosperous, inclusive and sustainable nation (Economic Planning Unit, Prime Minister's Department, 2021[7]). A driver identified in the plan is to remain committed to ensuring that Malaysia continues to be an attractive investment destination by introducing policy and regulatory reforms and improving governance. The use of Behavioural Insights (BI) has also been included in the 12MP.

In 2021, the Government of Malaysia replaced the 2013 National Policy on the Development and Implementation of Regulations (NPDIR) with the National Policy on Good Regulatory Practice (NPGRP). The NPGRP provides clearer and better guidelines on the adoption of GRPs and focuses on improving the quality of both new and existing regulations. The introduction of the new policy has also reinforced the importance of employing GRPs within the country. Updates to the 2013 NPDIR can be viewed in Table 7.1.

Table 7.1. Updates to the National Policy on Good Regulatory Practice

|

NPDIR |

NPGRP |

|

|---|---|---|

|

Title |

National Policy on the Development and Implementation of Regulations (NPDIR) |

National Policy on Good Regulatory Practice (NPGRP) |

|

Scope |

Business, investment and trade |

Economy, social and environment |

|

Tier of assessment |

Two-tier:

|

Three-tier:

|

|

Role of National Development Planning Committee (NDPC) |

|

|

|

Ex post evaluation |

Not included in NPDI but the clause available in Best Practice Regulation Handbook |

Existing regulation must be subjected to regulatory review once every 5 years |

|

Post implementation review (PIR) |

Not included in NPDIR but the clause is available in Best Practice Regulation Handbook |

Is required when a regulation has been introduced, removed or changed without a RIS. The PIR must be completed within two (2) years of the implementation of the regulation |

|

Behavioural Insights (BI) |

No |

Applying Behavioural Insights (BI) |

Source: (MPC, 2021[8]).

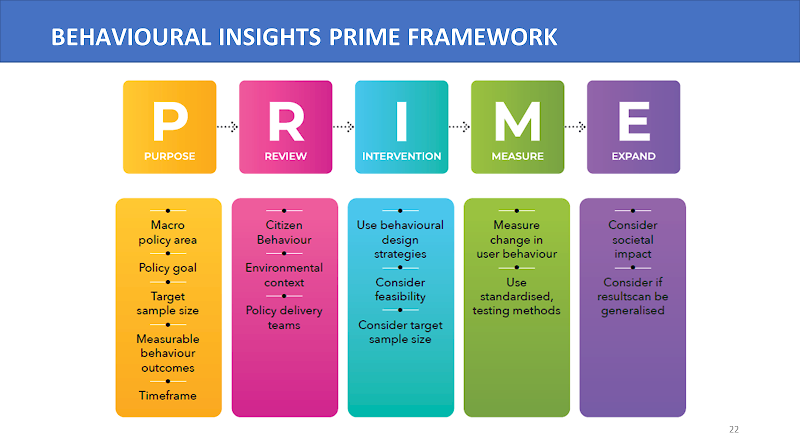

As part of the 12MP, Malaysia has committed to using Behavioural Insights (BI) to enhance regulatory quality and reduce unnecessary burdens. In February 2021, the MPC called for government ministries and agencies at federal, state and municipal level as well as regulatory authorities, to adopt BI in public services (Malaysiakini, 2021[9]). As part of the NPDIR, MPC is rolling out a Behavioural Insights (BI) Framework for government ministries and agencies, that sets out the fundamentals of applying BI in policymaking called the “PRIME” framework (see Figure 7.1). Malaysia notes that BI is being adopted as a complementary tool to enhance the Government’s services to the public. BI will be used to design and implement policies to guide the citizen towards making better decisions.

Figure 7.1. MPC’s PRIME framework for applying behavioural insights

Supporting SMEs

In 2019, the Ministry of Entrepreneur Development (MED) launched the National Entrepreneurship Policy (DKN 2030). DKN 2030 is the first policy document by MED in line with the functions of the Ministry that formulates policies for the development of an inclusive and competitive entrepreneurial community with a focus on the SME sector to enhance global competitiveness. “Strategic Thrust 2” includes a strategy to promote good governance, including enhancing ICT-based procedures for business registration, reporting and monitoring as well as promoting understanding and increasing access to information on business procedures, laws and regulation to improve compliance. Other strategies under Strategic Thrust 2 that are in line with good regulatory practices include enhancing and improving regulatory requirements for businesses and enhancing monitoring and assessments of outcomes and impacts.

At a Ministry level, Malaysia has worked to improve its regulatory framework to assist SMEs in innovation and use of digital technologies. Malaysia Digital Economy Corporation (MDEC), with government support, issued various policies for helping overseas start-ups establish their businesses in Malaysia. The policies include fast-tracking and special visas for start-ups, tax exemptions and allowances, and a facilitated process of registrations (Wisuttisak, 2020[11]). See examples of digitalisation and supporting SMEs in the section below on digital.

In the future, Malaysia is planning to release the New Industrial Master Plan 2030, which will provide strategic direction for resetting and realigning the industries towards achieving resilience, targeting 27 industries in Malaysia. Malaysia notes that there are several strategies outlined in the New IMP 2030 to facilitate and provide support to SMEs in adopting technology and digitalisation.

Digitalisation

To further enhance Malaysia’s readiness in harnessing the potential of the Fourth Industrial Revolution (4IR), Malaysia launched its national 4IR Policy 1 July 2021. The policy aims to transform the country into a high-income nation driven by technology and digitalisation by integrating efforts to transform the socio-economic development of the country through the use of advanced technology. This will complement the Malaysia Digital Economy Blueprint in driving the digital economy development.

Also to support Malaysia’s 4IR transition, the National Council on the Digital Economy and the Fourth Industrial Revolution (MED4IR) endorsed the establishment of the Digital Investment Office (DIO) on 23 April 2021. The DIO is a collaborative platform between MIDA and MDEC, which act as a single-window to co-ordinate and streamline digital investments and work closely with other Investment Promotion Agencies (IPAs) to promote and attract new digital investments in this fast-evolving industry. The DIO will streamline and expedite investment processes where investment strategy among the respective stakeholders will be aligned to decide the best location, incentive scheme, and other matters pertaining to digital investments. The DIO also provides end-to-end facilitation to investors covering pre and post project implementation. This includes providing information on the opportunities of digital investments, until the implementation of the project. The DIO has also launched the Heart of Digital ASEAN (MHODA) portal in 2021 to act as a single platform to attract and facilitate digital investments into Malaysia. Moving forward, the DIO seeks to continue working together with all State IPAs in accelerating the growth of digital investments, develop highly skilled local professionals, and groom digital global champions.

Finally, Futurise is a company that was established in 2018 under the purview of the Ministry of Finance to develop an innovation ecosystem inside the Malaysian government (OECD, 2021[12]). Futurise plays an active role as the Public Policy Advisor to ministries and agencies in developing anticipatory, progressive and inclusive regulatory framework that is imperative in shaping Malaysia for the Future Economy (Futurise, n.d.[13]). The first initiative created by Futurise was the National Regulatory Sandbox for digital technologies. The goal of the sandbox is to create a safe environment where pre-determined set of rules as agreed together with regulators will allow entrepreneurs to build, test their products and business models in a live environment in conjunction with new regulations (Singh, 2019[14]).

Improving trade facilitation

The Royal Malaysia Customs Department developed the National Authorised Economic Operator (AEO) Programme which focuses on trade facilitation. In addition to moving towards a whole-of-government approach with 44 participating government agencies, the National AEO Programme has had the effect of improving regulation in Malaysia by (AEO Malaysia, 2021[15]):

Fostering more transparent governance;

Encouraging more accurate payment of duties and taxes;

Simplifying import/export process through integrated trade facilitation methods;

Securing and facilitating legitimate trade, increasing operational efficiency; and

Aligning existing compliance programmes

Good regulatory practices

Regulatory impact assessments

Malaysia has remained committed to implementing good regulatory practices and has been embedding regulatory impact assessments (RIAs) across government since 2013. In 2013, the Government of Malaysia launched the National Policy for the Development and Implementation of Regulations (NPDIR), which reinforced mandates for better regulation within the country. Among the GRP initiatives that were implemented since 2013 (spanning the 10th, 11th and 12th Malaysia Plans) include:

July 2013: Established the NPDIR, with the aim to ensure the Ministries and Agencies implement the RIA and public consultation in developing new and review existing regulations. GRP Portal was developed to be used as a repository and reference for all regulators and stakeholders. A total of 180 Regulatory Coordinators (RCs, i.e. focal points) from 94 ministries and agencies registered with MPC and received training on Regulatory Impact Analysis or RIA from the OECD.

2013 and onward: Introduced and implemented the program on Reducing Unnecessary Regulatory Burden (RURB) or now it is known as #MyMudah that reviews all existing regulations. Regulations that are efficient and effective are regulations that contributes to the growth of nations while removing or improving regulations that are obsolete or burden. MPC and the National Institute of Public Administration (INTAN) carried out training on RIA to all government officers. MPC also provides advisory and developed guideline such as Best Practices on GRPs, public consultation procedures and others.

2016 and onward: Capacity building program and GRP management system created for the State Government and Local Authority. Among the State government that had succeed in developing GRP policy are Sarawak, Kelantan and Sabah.

2019 and onward: The development of Unified Public Consultation (UPC) as a one-stop online portal for public consultation for all Ministries and Government agencies. Aim is to facilitate the participation of the stakeholders in the regulation development process. UPC intended to contribute to the Government’s commitment towards accountability, transparency and inclusiveness.

2020 and onward: Introduced and developed capacity for government officials to apply the BI approach to enable effective policy formulation and implementation

2021 and onward: Expanded the establishment of MyMudah units to all federal ministries and agencies, state government, local authorities and industry associations to conduct regulatory reviews in a planned manner to facilitate the business environment to boost productivity and competitiveness and implementing regulatory experimentation programne that involves public and private stakeholders jointly assessing the efficiency and suitability of existing regulations.

As discussed above, this has been strengthened in 2021 with the release of the National Policy on Good Regulatory Practices (NPGRP), which replaces the NPDIR. The NPGRP is intended to be an update in line with core GRP methodologies of regularly updating policies after implementation. Under NPGRP, MPC's role is examine the adequacy of RIS and provide recommendations, provide guidance and assistance to regulators on RIS preparation and promote the transparency of RIS. For monitoring purpose, MPC will undertake assessment on the effectiveness of the implementation of the policy and report to NDPC. It's an updated version from the previous NPDIR.

In Malaysia, all new regulations and review of existing regulations must undergo a regulatory impact assessment (RIA) and are required to have their impacts and benefits systematically identify and assessed (OECD, 2018[16]). This also applies to any policy alternatives, such as non-regulatory options, as a way to ensure that all possible options are comprehensively reviewed and if required, are selected (OECD, 2018[16]). Should there be a case where the impact of a proposed regulation is minor and does not significantly change existing regulatory arrangements, the regulator could implement the regulation directly after the approval of the decision maker (in accordance with the law). That being said, the MPC must be notified when the regulation has been issued (OECD, 2018[16]).

MPC has digitalised the Regulatory Notification Submission process by launching the Digital Regulatory Notification (DRN) system, which aims to improve the efficiency of rule-making process and supporting GRPs. This move is in line with government ongoing digitalisation initiatives that seeks to bring further positive impact to the productivity and competitiveness of the country. The DRN also has the ability to automatically assess and provide feedback, which has reduced the time necessary to provide feedback on the type of RIA require from 10 days to almost instantly. The regulators are then notified if the proposal would require lite RIA, full RIA or only consultation. The magnitude of the impact of the regulations have towards the business, environment and public will determine the type of RIA that needs to be carry out.

In general, the MPC is responsible for providing guidance and assistance to regulators in RIA and preparation of regulatory impact statements (RIS), while the National Institute of Public Administration (INTAN) is responsible for providing public service RIA training (MPC, 2021[17]). MPC has actively conducted several “Training of Trainer” (ToT) sessions to all interested parties since the promulgation of the NPDIR as a means to grow RIA experts in the country (Zico Law, 2020[18]). Malaysia has also used the appointment of RCs to offer support to ministries with the application of regulatory tools.

In 2021, alongside the release of the NPGRP, Malaysia also released the Best Practice Regulation Handbook 2.0 (MPC, 2021[19]), which serves as a reference guide for regulators to implement the NPGPR and the Regulatory Process Management System (RPMS). It provides step-by-step guidance for the implementation of and compliance with the NPGRP and provides stage-by-stage guidance on how to do a RIA and prepare a RIS.

According to the Best Practice Regulation Handbook 2.0 (MPC, 2021[19]), the RIA must clearly identify all the groups affected, whether directly or indirectly, by the problem and its proposed solution. Groups should generally be distinguished as consumers, workers, business and the government. These groups may be further sub-categorised. Further, the RIS must demonstrate that the consultation process was credible, balanced and fair. Draft regulations should be made available to interested parties for them to be informed in greater detail on the government’s proposed course of action. The RIS should provide a summary of the consultation process, the main substantive comments received and how they were taken into account.

MPC has continually provided RIA guidance as well as training in recent years. Examples of efforts since 2018 by the MPC to enhance use of RIA include the following (MPC, n.d.[20]):

GRP Conference 2018: The conference addressed challenges of implementation of GRPs as a national transformation strategy and was held in conjunction with the 4th GRPN with the OECD as well as the Workshop on International Regulatory Co-operation (IRC) with ERIA.

Launching of Report on Modernisation of Regulations 2018: The report provides information on Malaysia’s regulatory reform journey and aims to inform stakeholders on improvements taking place in the regulatory environment and the progress achieved in the implementation of the National Policy on the Development and Implementation of Regulations (NPDIR). For the period of 2016 to 2017, 32 projects under Modernising Business Licensing, Reducing Unnecessary Regulatory Burden and Cutting Red Tape Programs were completed. These had resulted in potential compliance cost savings of RM1.18billion (2016) and RM1.20billion (2017).

National GRP Conference: The conference is part of a series of annual events that were originally held under the Programme on Modernising Business Regulation and has continued, following the completion of this programme, as an annual event to promote GRPs as well as share experiences and good practices among international and local experts and practitioners to enhance knowledge and capacity of government officials. It brings together policy-makers, regulatory agencies, experts and the private sector, with the most recent conference theme in 2021 being "Boosting Productivity Through Quality Regulation".

Stakeholder engagement

In October 2014, the government released a set of guidelines on public consultation procedures. The guidelines ensure that the following principles are met: 1) transparency with accessibility; 2) accountability; 3) commitment; 4) inclusiveness; 5) timely and informative; and 6) integrity with respect (OECD, 2018[16]).

Consultation is one of the seven elements of RIA in Malaysia. The 2021 NPGRP stipulates that Regulators proposing new regulations or changes must carry out timely and thorough consultations with affected parties. Moreover, notice of proposed regulations and amendments must be given so that there is time to make changes and to take comments from affected parties into account (MPC, 2021[17]) and the consultation process must be clearly set out by regulators. Public consultation can take many forms, such as (OECD, 2018[16]):

Stakeholder meetings

Public meetings

One-to-one interviews

Public surveys

Focus groups

Round table discussions

Web forums

The Best Practice Regulation Guidebook (MPC, 2021[19]) states that, in general, any proposed new regulation or change to regulation must involve consultation with relevant stakeholders particularly the parties affected by the proposal such as the community, businesses and non-governmental organisations (NGOs). Consultation must be held for a minimum of 30 days. Consultation must be conducted in a timely manner that reflects a genuine effort to hear and consider the views of stakeholders and must not be conducted as a “box-ticking” exercise after the policy decision has effectively been made. The RIS must include a summary of the consultation. It also requires post implementation reviews (PIRs) within 2 years when a regulation has been introduced, removed or changed without a RIS.

The guidelines further require that notifications that are required to be submitted to the World Trade Organization (WTO) should be included for proposals that fall within the scope of the notification obligations of the Agreement on Technical Barriers to Trade (TBT) and the Agreement on the Application of Sanitary and Phytosanitary Measures (SPS) The WTO TBT1 and SPS2 enquiry points should be consulted for advice and assistance in making the notifications.

The RIS must demonstrate that the consultation process was credible, balanced and fair. Draft regulations should be made available to interested parties for them to be informed in greater detail on the government’s proposed course of action. The RIS should provide a summary of the consultation process, the main substantive comments received and how they were taken into account.

An example of a national policy formulated through extensive stakeholder engagement is the National 4IR Policy. The National 4IR Policy was developed through various engagements with 25 ministries, 51 agencies, state governments and private sector including 460 companies, 22 industry associations and 33 technology providers through focused meetings, surveys and workshops (EPU, 2021[21]). Another example is the Twelfth Malaysia Plan, the development roadmap for Malaysia from 2021 to 2025. The Twelfth Plan has been drawn up based on extensive engagements with various stakeholders, including ministries, state governments, the private sector and civil society organisations (CSOs), as well as online engagements with the public (Economic Planning Unit, Prime Minister's Department, 2021[7]).

Malaysia has also made use of digital technologies to improve the quality of public consultations. The Unified Public Consultation (UPC) portal was established by the Government in 2019 in conjunction with the National Convention of Good Regulatory Practice 2019 to facilitate stakeholder engagement in rule‑making processes. As of 2021, there were 67 ministries and agencies that participated in UPC and 390 consultation documents were received which have been uploaded for public feedback (MPC, n.d.[20]). All regulators are required to utilise UPC for the purpose of public consultation on proposed new regulations or changes to regulation. This program focussed on reducing administrative burdens among companies and businesses as well as promoting stronger co-operation between the government and private sector by encouraging stakeholder engagement via online consultations (OECD, 2021[12]). The programme has also reportedly enhanced communications between central agencies and ministries and has new direction for the government to promote agile regulatory approaches.

Burden reduction/ex post review

In July 2021, the Government of Malaysia released the NPGRP, which replaces the NPDIR. Similar to the NPDIR, the NPGRP also has a periodic review mechanism. It requires ex post reviews on all existing regulations once every 5 years. It also requires post implementation reviews (PIRs) within 2 years when a regulation has been introduced, removed or changed without a RIS. The 2021 Best Practice Regulation Handbook 2.0, released alongside the NPGRP, gives some further guidance for each of these review mechanisms. Moreover, the NPGRP introduces business compliance costs as a new feature to make the use of impact analysis more “user friendly”. The NPGRP encourages the adoption of the widely used Standard Cost Model (SCM), particularly for ex-post reviews, as a means to measure compliance costs and quantifying administrative burdens for businesses (Zico Law, 2021[22]).

Malaysia has also improved its regulatory environment in terms of reducing unnecessary burdens. As noted in OECD (2018), since 2007, PEMUDAH has been working with the MPC to address regulatory issues concerning the ease of doing business. Malaysia reports that some of the success story on the initiative by PEMUDAH to ease of doing business include:

Improving the Efficiency in Dealing with Construction Permits in Kulim Kedah: Previously it took 24 months on average to obtain permits and licenses, from planning approval to factory operation. This is due to approval processes are conducted sequentially. Under MyMudah initiatives, regulators and business work together to review and improve the process. Some of the process is now made concurrently. As the result, the process is now take 10 months and this initiative has been scaled-up to other states.

Expediting the process of obtaining Certificate of Completion and Compliance (CCC): During movement control order, numbers of completed buildings and premises cannot be occupied due to CCC are yet to be issued. The delay was due to pending in the issuance of ‘Clearance Letter' by Technical Agencies, which is one of the requirements for the professionals to issue the CCC. Through #MyMudah, a concept called ‘silence implies consent’ was introduced, meaning that if no feedback is given by the Technical Agencies after 14 or 28 days from the date they received complete application, approval will be given automatically. By addressing this issue, businesses can start their operation faster and created RM1.75 billion compliance cost savings per year.

In the 10th Malaysia Plan (2010-15), MPC was granted the mandate to improve the government’s regulatory management system, which led MPC to undertake a review to assess, repeal or modify unnecessary rules and compliance costs that negatively impact businesses or the economy (OECD, 2018[16]). This regulatory review was carried out as part of Malaysia’s Modernising Business Regulation (MBR) programme, which included the following key initiatives implemented by the MPC (OECD, 2018[16]):

Reducing Unnecessary Regulatory Burden (RURB).

Facilitating initiatives in Ease of Doing Business.

Conducting comprehensive scanning of business licensing.

Promoting Business Enabling Framework for 18 services subsectors.

Developing policy and guidelines for ensuring the quality of new regulations such as the National Policy on the Development and Implementation of Regulations.

Burden reduction is part of government and ministry initiatives. For example, the Twelfth Malaysia Plan (2021–2025) reiterated the government’s commitment to regulatory reform through efforts to strengthen the public service for greater efficiency. This includes reviewing and streamlining structures and functions of ministries and agencies to reduce unnecessary bureaucratic practices and to optimise the use of resources. The Malaysia Productivity Blueprint (MPB) launched in May 2017 also contains provisions regarding burden reduction. In order to promote business growth, the Blueprint recommends the restructuring of non-tariff measures, including customs regulations, to ensure streamlined processes and regulations for export and import permits and regulations. Moreover, the Blueprint also recommends expanding the guillotine approach2, which is used widely around the world to rapidly streamline regulations (ERIA, 2018[23]). The Malaysia Cyber Security Strategy also mandates the review of regulations as necessary to remove outdated regulations that could hinder the growth of digitalisation (EPU, 2021[24]).

A Guideline on Reducing Regulatory Burden (MPC, n.d.[25]) was established to help guide policymakers in identifying and analysing areas for burden reduction. Initial activities under the programme have been focused on increasing efficiency within the government by simplifying the administrative requirements related to the issuance of permits and licenses.

Additionally, as mentioned briefly in the section above, the #MyMUDAH initiative (MPC, 2021[26]) was implemented in July 2020 as a fast-forward solution to address the economic impact of COVID-19. It was initially a strategy to improve regulatory quality to mitigate against regulatory challenges being faced by businesses due to COVID-19 and has since been adapted to also help in achieving national economic recovery in the endemic period. On 24 November 2021, YAB Prime Minister chaired an Economic Action Council (EAC) meeting that decided the #MyMUDAH Initiative should be strengthened by establishing #MyMUDAH units in all federal ministries and agencies. The meeting also proposed for #MyMUDAH units to be established at the State Government level, local authorities and industry associations to holistically facilitate the doing of business country-wide.

Digital

In recent years, Malaysia has committed both to using digital technologies to improve regulatory management and policy responses and to reforming its regulatory framework to foster innovation in the digital era. In the UN E-Government Survey 2020, Malaysia improved its ranking to 47th in the E‑Government Development Index (EGDI) as compared to 60th in 2016 (EPU, 2021[21]).

MyDIGITAL, which was launched in February 2021 by the Prime Minister, is a national initiative that symbolises the Government's aspiration to transform Malaysia into a digitally-enabled and technology-driven high-income nation, and a regional leader in digital economy (EPU, 2021[24]). The MyDIGITAL initiative sets out various measures and targets to be implemented in three phases until 2030. The initiative comprises several action plans, which adopt a whole-of-government approach to complement the existing national development policies and initiatives, including the 12MP (RMK-12) and the Shared Prosperity Vision 2030 (27Group, 2021[27]). Regulation plays a substantive role throughout the document with a particular focus on Thrust 2, “Boost Economic Competitiveness Through Digitalisation”, Thrust 3, “Build Enabling Digital Infrastructure”, and Thrust 5, “Create an Inclusive Digital Strategy” (see Table 7.2).

The current implementation of the MyDIGITAL agenda and its accompanying policy documents i.e. the Malaysia Digital Economy Blueprint (MDEB) and the National 4IR Policy (N4IRP), outline specific initiatives on improving regulatory coherence and legislative transparency pertinent to digital economy development in Malaysia. The various initiatives under MyDIGITAL also translated Malaysia’s priorities in digital transformation for SMEs to achieve the set target of 22.6% of digital economy contribution to the national GDP and a collective of 875 000 MSMEs adopting e-commerce by 2030.

Table 7.2. MyDIGITAL national initiative

|

Strategic thrust |

National initiative and description |

|---|---|

|

THRUST 02: Boost economic competitiveness through digitalisation |

Adopt an agile regulatory approach to meet the needs of digital economy businesses This initiative aims to identify priority regulations to review and update Developing code of conduct (for regulators) to encourage industry involvement in regulatory designs for the digital economy Identifying areas of involvement in developing a typology of relevant regulatory approaches to capitalise on opportunities and mitigate the challenges of digital transformation Expanding regulatory sandboxes |

|

THRUST 03: Build enabling digital infrastructure |

Review laws and regulations to improve provision for digital infrastructure This initiative aims to review, improve and streamline all relevant federal and state legislations and regulations regarding digital infrastructure development |

|

THRUST 05: Create an inclusive digital society |

Providing an online platform to facilitate better access for vulnerable groups This initiative aims to provide a one-stop online platform through integration of existing platforms, designated for vulnerable groups such as the B40, women and people with disabilities to obtain information and resources to grow their online businesses. The platform provides information and services such as business-related information including business registration procedures, regulations, business opportunities, existing government assistance programmes and financial resources. |

Source: (EPU, 2021[24]).

Additionally, under the National e-Commerce Strategic Roadmap (NeSR) 2.0, endorsed by the Malaysian Council on Digital Economy and Fourth Industrial Revolution on 22 April 2022, more targeted activities were identified to encourage SMEs in Malaysia to use e-commerce as the engine for catalytic growth for businesses. The NeSR 2.0 recognises that enhancing e-commerce ecosystem development and strengthening policy and regulatory environment are some of the guiding principles to accelerate growth & innovation of Malaysia’s e-commerce especially among SMEs. The implementation of the NeSR 2.0 with the involvement of 11 Ministries/Agencies via 6 Strategic Thrusts with 16 Strategic Programmes includes legislative review and national standards development relevant to the digital economy ecosystem.

Digital technologies are also increasingly used to support the stakeholder engagement process in Malaysia. The #MyMudah Programme allowed companies and businesses to highlight regulatory issues through the Unified Public Consultation (UPC) Portal, as well as to take part in dialogues organised by the government (OECD, 2021[12]). UPC was established to make stakeholder engagement in the rule making process more uniform, effective and efficient. It gives the public easy access to regulatory consultations through a single website. UPC also contributes to achieving the Government’s commitment to accountability, transparency and inclusiveness.

Malaysia also has several online databases relevant to regulatory policy and support for businesses including SMEs. These include:

Good Regulatory Practice: This database provides information on regulatory impact analysis, reducing unnecessary regulatory burdens and regulatory stock. It is available to the public.

Malaysia Digital Economic Blueprint (MDEB): MPC has been mandated to lead the initiative, Agile Regulatory approaches to meet the needs of the digital economic businesses (Thrust 2, Strategy 3, Initiative 4). The strategic objectives are to create a regulated environment that is conducive for the economic digital environment; to review regulation requirement to facilitate innovation and expand coverage to include new technologies and business models.

MyGov: This portal is a mobile application of the Malaysian Government Portal and has the aim to diversify Government service channels to the people for access to digital services and information.

MyAssist MSME (SME Corporation, 2022[28]) was created under the economic recovery plan “Pelan Jana Semula Ekonomi Negara” (PENJANA) that was announced by the Prime Minister of Malaysia on 5th June 2020. This initiative is lead by the SME Corporation Malaysia to create an avenue for MSMEs to obtain information and advisory services on conducting business especially during post COVID-19. It features an online one-stop business advisory platform online and via mobile application that is dedicated to assist SMEs in their business-related problems and issues through the provision of business advisory and information, digital marketing opportunities and guidance; technology and business innovation support facilitation; business matching services; and various channels of online initiatives that are linked to implementing agencies under PENJANA. This platform also offers information dissemination through webinar sessions and e-commerce platform. Its components consists of information centre, advisory services and feedback mediums that is used to gather feedbacks through direct interactions via live chat. Other services that is available on the platform are the integration of SMEinfo portal, MeetME (online business advisory), MatchME (online business matching) as well as e-exhibition platform (see more details in the section on digital).

SMEinfo Portal is a centralised online information gateway for MSMEs that offers information on all aspects of MSME development in Malaysia, including links to helpful websites and news. The portal provides MSMEs with access to information on all Government programmes for MSME development, including the various financing schemes and business support services. In addition, the Portal also provides information on business guides for different stages of business, as well as financial tools to assist MSMEs to manage their financial management.

MySOL: This is an online system whereby more than 4 800 Malaysian Standards (MS) can be accessed for purchase. MySOL is a new service delivery system offered by the Department of Standards Malaysia as the National Standards Body in Malaysia. The public can easily access and purchase the MS through this system.

Accredited Organisation Directories: This database provides information on accredited conformity assessment bodies in Malaysia that help the industry explore the availability of accredited conformity assessment services. Conformity assessment services are required by the industry to verity their products, services or systems meet the requirements of a standard.

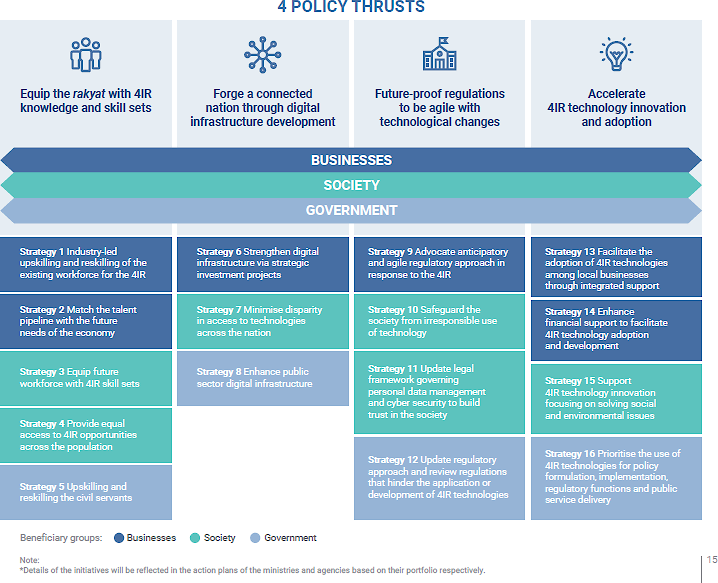

Malaysia’s National Fourth Industrial Revolution (4IR) Policy is a broad, overarching national policy that drives coherence in transforming the socioeconomic development of the country through ethical use of 4IR technologies (EPU, 2021[21]). It aims to ensure that the people will enjoy an improved quality of life through leveraging technologies and enabling a conducive doing-business environment that allows more technology innovation for business to flourish (EPU, 2021[21]). The policy advocates for the use of technology to the advantage of society, businesses and the government. In the area of government, the policy recognises that a technologically-enabled government will provide more efficient, effective and modernised public services (EPU, 2021[21]) and aims to ensure that national planning will become smarter and data-driven. Moreover, the third policy thrust, Future-proof Regulations to be Agile with Technological Changes, calls for an agile regulatory framework, approach and governance to build trust in society and to provide a conducive environment for innovation (see Figure 7.2).

Policies to enhance regulation for specific sectors in the digital era are also in place in Malaysia. The Industry 4WRD policy is a national policy launched in 2018 by the Ministry of International Trade and Industry (MITI) with the aim of transforming the manufacturing sector and related services from 2018 to 2025. The policy encourages small and medium-sized enterprises (SME) in increasing efficiency and productivity to remain relevant and competitive at domestic and global levels (MITI, n.d.[29]). One of its objectives is to “create a holistic ecosystem to support the adoption of Industry 4.0 by industries and co‑ordinate existing initiatives in various related aspects such as talent and workforce, funding, infrastructure and regulation”, with regulatory frameworks being identified as one of the primary enablers.

In addition, Biz4 WRD is a portal launched by the Ministry of International Trade and Industry MITI on 30 October 2019. This portal is a collaborative platform to connect and match companies intending to adopt Industry 4 0 solutions. It establishes a central repository and creates an ecosystem for businesses to establish their Industry 4.0 offerings and allows businesses seeking solutions to engage one another. It allows parties to search, promote, connect and exchange information with businesses and companies across the manufacturing and services industries.

Figure 7.2. National Fourth Industrial Revolution (4IR) policy thrusts

Source: Economic Planning Unit, Prime Minister’s Department, 2021.

Malaysia’s National Single Window has been in operation since 2009. It is an initiative of the Malaysian Government, led by the Ministry of Finance. NSW for Trade Facilitation system was developed, operated and managed by Dagang Net Technologies Sdn Bhd (Dagang Net) (MITI, 2018[30]). The NSW serves as a main gateway for trade in Malaysia and as a platform that provides an effective and economical means for traders to submit their data in electronic format through a web-based application, i.e., myTRADELINK (www.mytradelink.gov.my) (MITI, 2018[30]). The 6 modules in the NSW gateway include (MITI, 2018[30]):

Electronic Customs Declaration (eDeclare): Preparation and submission of electronic Customs Declarations online;

Electronic Customs Duty Payment (ePayment): Preparation and submission of Customs Duty payments via Electronic Funds Transfer, Duty Net and FPX;

Electronic Manifest (eManifest): Submission of vessel cargo manifests to respective authorities by shippers and shipping agents;

Electronic Permit (ePermit): Application for permits from relevant Permit Issuing Authorities (PIAs) and obtain approval online;

Electronic Preferential Certificate of Origin (ePCO): Application for Preferential Certificate of Origin and obtain approval online; and

Electronic Permit Strategic Trade Act (ePermitSTA): Application for pre-registration and permits under the Strategic Trade Act 2010 online.

Implementation of the Malaysian National Single Window has contributed to more efficient and streamlined processes in trade. The one-stop Trade Facilitation system links the trading community with relevant Government agencies and various other trade and logistics parties through one single window, which allows for a seamless and transparent process (Dagangnet, n.d.[31]).

The ASEAN Single Window (ASW) is a regional electronic trade facilitation initiative that connects and integrates the National Single Window (NSW) of all 10 ASEAN Member States (AMS) to strengthen trade relations and intensify trade activities among AMS. The essential prerequisite for an AMS to participate in the ASW initiative is to have a running and a functional NSW which can cater to the electronic exchange of cross-border trade-related documents. Where exchange of electronic trade document is concerned, e‑Preferential Certificate of Origin (e-PCO), one of 6 modules developed in the Malaysia’s NSW, is interoperable with other ASEAN Member States’ NSWs to allow submission of electronic Certificate of Origin within the ASW environment.

Malaysia also serves as an active member in the ASW Steering Committee (SC) and ASW Technical Working Group (TWG), which have proposed, aligned and harmonised the ASW processes and procedures to ensure smooth exchange of Malaysia NSW with AMS’ counterparts’ NSW. As a result, Malaysia has started utilising the ATIGA e-Form D to enjoy preferential tariff treatment for goods produced and traded within ASEAN. The digitisation of this document has allowed for a swifter preferential tariff treatment to happen by doing away with the administrative burdens and waiting time of processing and producing hard copy documents that were required when dealing with issuing authorities and custom authorities of the importing countries. Consequently, Malaysia notes that this initiative has helped traders save time and costs, expedites cargo clearance and reduces possibility of errors from the manual exchange of forms.

Malaysia has also started joining the live operation of ASEAN Customs Declaration Documents (ACDD) exchange to respectively expedite movement of goods across border and as a mean to provide pre-arrival information that is useful in risk assessment by Customs. Expansion plans of the ASW have been planned to take off particularly in exchanging the Electronic Phytosanitary (e-Phyto), Electronic Animal Health (e‑AH) and Electronic Food Safety (e-FS) between the AMS.

References

[27] 27Group (2021), What is MyDIGITAL Initiative & Digital Nasional Berhad about?, https://27.group/what-is-mydigital-initiative-digital-nasional-berhad-about/.

[15] AEO Malaysia (2021), GRPN Presentation, https://www.oecd.org/gov/regulatory-policy/04-Malaysia-Asha.pdf.

[3] APEC (2020), ASEAN Regulatory Cooperation Project.

[4] ASW (n.d.), , https://asw.asean.org/.

[1] Bernama (2022), “RCEP comes into force for Malaysia on March 18, 2022”, Bernama, http://prn.bernama.com/melaka/news.php?c=02&id=2063032 (accessed on 4 July 2022).

[31] Dagangnet (n.d.), NSW for Trade Facilitation, http://www.dagangnet.com/trade-facilitation/national-single-window/#:~:text=In%20Malaysia%2C%20the%20backbone%20of,single%20window%2C%20which%20allows%20for.

[7] Economic Planning Unit, Prime Minister’s Department (2021), Twelfth Malaysia Plan 2021-2025 Executive Summary.

[24] EPU (2021), Malaysia Digital Economy Blueprint, Economic Planning Unit (EPU), Prime Minister’s Department, https://www.epu.gov.my/sites/default/files/2021-02/malaysia-digital-economy-blueprint.pdf (accessed on 5 July 2022).

[21] EPU (2021), National Fourth Industrial Revolution(4IR) Policy.

[5] ERIA (2020), Interconnected Government: International Regulatory Cooperation in ASEAN.

[23] ERIA (2018), Reducing Unnecessary Regulatory Burdens in ASEAN: Country Studies, Economic Research Institute for ASEAN and East Asia.

[13] Futurise (n.d.), , https://www.futurise.com.my/about.

[32] Jacobs, S. and I. Astrakhan (2006), Effective and Sustainable Regulatory Reform: The Regulatory Guillotine in Three Transition and Developing Countries, World Bank Conference on Reforming the Business Environment, https://regulatoryreform.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/Evaluation_of_the_regulatory_guillotine_in_7_countries_2006.pdf (accessed on 17 August 2022).

[9] Malaysiakini (2021), MPC calls for adopting behavioural insights in government policies, https://www.malaysiakini.com/announcement/562420.

[6] Ministry of Economic Affairs (2019), Shared Prosperity Vision 2030.

[30] MITI (2018), National Single Window, https://www.miti.gov.my/index.php/pages/view/1149.

[29] MITI (n.d.), Industry4WRD, https://www.miti.gov.my/index.php/pages/view/4832.

[26] MPC (2021), #MyMudah, http://mymudah.mpc.gov.my/ (accessed on 19 June 2021).

[19] MPC (2021), Best Practice Regulation: Handbook 2.0, Malaysia Productivity Corporation (MPC), National Competitiveness Section, https://www.mpc.gov.my/npgrp/newfiles/handbook_BI.pdf (accessed on 8/03/2022).

[8] MPC (2021), National Policy on Good Regulatory Practice (NPGRP), Malaysia Productivity Corporation, https://www.mpc.gov.my/npgrp/ (accessed on 28 September 2022).

[17] MPC (2021), National Policy on Good Regulatory Practices.

[10] MPC (2020), Prime Framework: Applying Behavioural Insights for Better Public Policy, Malaysia Productivity Corporation (MPC), Kuala Lumpur, https://grp.mpc.gov.my/static_files/media_manager/52/PRIME%20Book%20UPDATED%2018-12-20.pdf (accessed on 27 September 2022).

[20] MPC (n.d.), GRP Portal, https://grp.mpc.gov.my/ria/training.

[25] MPC (n.d.), Regulatory Impact Assessment (RIA), Malaysia Productivity Corporation (MPC), Official Portal for Good Regulatory Practice, https://grp.mpc.gov.my/ria/ris (accessed on 28 September 2022).

[2] OECD (2021), Economic Outlook for Southeast Asia, China and India 2021: Reallocating Resources for Digitalisation, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/711629f8-en.

[12] OECD (2021), “Regulatory responses to the COVID-19 pandemic in Southeast Asia”, OECD Policy Responses to Coronavirus (COVID-19), OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/b9587458-en.

[16] OECD (2018), Good Regulatory Practices to Support Small and Medium Enterprises in Southeast Asia, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264305434-en.

[14] Singh, K. (2019), Digital News Asia, https://www.digitalnewsasia.com/digital-economy/futurise-aims-unlock-value-malaysias-digital-economy.

[28] SME Corporation (2022), MyAssist MSME, https://myassist-msme.gov.my/ (accessed on 4 July 2022).

[11] Wisuttisak, P. (2020), Comparative Study on Regulatory and Policy Frameworks for Promotion of Startups and SMEs in Japan, the Republic of Korea, Malaysia, and Thailand, ADB.

[22] Zico Law (2021), The NPGRP Strengthens Public Sector Governance and the Regulatory Reform Initiative.

[18] Zico Law (2020), The role of RIA in Policy Making.

Notes

← 1. Citizens are referred to as rakyat in Malaysia.

← 2. The guillotine strategy refers to rapidly reviewing a large number of regulations and eliminating those that are no longer needed without any lengthy processes for each regulation (Jacobs and Astrakhan, 2006[32]).