This chapter presents an Assessment Framework for resilient, inclusive, sustainable and circular (RISC-proof) blue economies in cities and regions. The framework is a tool for subnational governments to self-evaluate the resilience, inclusiveness, sustainability and circularity of their blue economy and the level of implementation of the enabling governance conditions (policy making, policy coherence and policy implementation) to get there. Through bottom-up, multi-stakeholder dialogues, the framework aims to facilitate a comprehensive diagnosis of the blue economy and support a consensus on the governance improvements required over time.

The Blue Economy in Cities and Regions

4. An Assessment Framework for resilient, inclusive, sustainable and circular (RISC-proof) blue economies in cities and regions

Abstract

Methodology

Building on Chapter 3, this chapter presents an Assessment Framework for the RISC-proof blue economy in cities and regions (hereafter RISC Assessment Framework) as a tool for governments to self-evaluate the resilience, inclusiveness, sustainability and circularity of their blue economy, and the level of implementation of the enabling governance conditions to get there. The tool can be used to evaluate the state of play of the blue economy and the existence of enabling governance conditions in cities or regions, identify the main gaps and define priorities and actions to bridge them. The process provides an opportunity to collect data on the blue economy and information on the perception of non-government stakeholders to feed into decision making. Ultimately, the assessment could support the development of a local or regional blue economy strategy or feed into other related plans (e.g. coastal management plans, economic development plans, etc.).

The framework builds extensively on the multi-stakeholder approaches developed as part of existing OECD self-assessment frameworks for water governance and the circular economy, namely the OECD Water Governance Indicator Framework (OECD, 2018[1]) and the OECD Checklist for Action and Scoreboard on the Circular Economy in Cities and Regions (OECD, 2020[2]). The RISC Assessment Framework was pilot-tested in four OECD and non-OECD cities and regions: the region of Los Lagos in Chile, Korle-Klottey Municipal Assembly in Ghana, the city of Porto in Portugal and the city of eThekwini in South Africa. Cities and regions were asked to pilot-test the three-part framework by carrying out the five-step methodology and reporting on its validity, practicality and relevance. Pilot testers found the questions clear and accessible, and all three parts were useful and coherent in terms of sequencing. Their suggestions to finetune the framework have been integrated into the final version.

The RISC Assessment Framework is based on a bottom-up and multi-stakeholder approach rather than a reporting, monitoring or benchmarking perspective since the RISC and enabling conditions of the blue economy in cities and regions are highly place-based, thus requiring a territorial approach. The framework is designed for local and regional governments to engage in multi-stakeholder dialogues that facilitate a comprehensive evaluation of the RISC and enabling conditions of the blue economy at local or regional level and support a consensus on the improvements needed over time. It can help governments and blue economy stakeholders identify strengths, weaknesses and opportunities for improvement, thereby guiding strategic decision making and supporting RISC-proof blue economies.

The RISC Assessment Framework consists of three parts (Figure 4.1) and is carried out using a five-step multi-stakeholder methodology (Box 4.1).

Figure 4.1. RISC Assessment Framework building blocks

In Part 1, subnational governments are invited to assess the level of resilience, inclusiveness, sustainability and circularity (RISC-proof) of the blue economy in their city or region. Part 1 contains:

What? A definition of each dimension (resilience, inclusiveness, sustainability and circularity).

Why? A rationale for each dimension and examples of potential benefits for blue economy sectors and ecosystems.

How? Questions for the assessment of the level of resilience, inclusiveness, sustainability and circularity of the blue economy in the city or region, followed by additional questions to foster discussions and examples of indicators from the OECD and other sources to help assess how the city or region is doing on each dimension.

In Part 2, local and regional governments can assess the level of implementation of the enabling governance conditions for a RISC-proof blue economy in their city or region. This assessment consists of nine assessment questions (one for each of the “ways forward” identified in Chapter 3) for policy making, policy coherence and policy implementation.

In Part 3, local and regional governments wishing to build water security into their blue economies can use the “whole of water” checklist as a brainstorming tool. Recognising that water security is often a blind spot of subnational blue economy strategies, the checklist proposes a non-exhaustive list of actions for subnational governments to consider when designing blue economy strategies and policies.

Box 4.1. How to use the RISC Assessment Framework

To carry out the assessment, the following steps are recommended (Figure 4.2): i) identify the lead team within the local or regional government to co-ordinate the assessment; ii) define the objectives and scope of the assessment; iii) map stakeholders to participate in the assessment; iv) organise targeted workshops with key stakeholders to perform the assessment; and v) repeat the process regularly.

Figure 4.2. A five-step self-assessment methodology

Source: OECD (2020[2]), Synthesis Report: The Circular Economy in Cities and Regions, https://doi.org/10.1787/10ac6ae4-en.

Identify the lead team to co-ordinate the assessment. To ensure the success of the assessment process, the local or regional government should appoint a lead team (e.g. within a government department or agency) to co-ordinate the process. The lead institution should have the convening power to gather stakeholders and thoughtfully plan and manage the entire assessment process. In addition to having the human, financial and technical capacity to carry out the assessment process, the lead institution should be motivated and able to promote and put in practice the proposals for change resulting from the assessment.

Define the objectives and scope of the assessment. Several objectives can trigger the use of the RISC Assessment Framework, which is intended as a tool for dialogue among stakeholders to see where the government is performing well and where adjustments are needed. More specifically, the assessment can be carried out to promote collective thinking among stakeholders, share knowledge and address asymmetries of information across governments and stakeholders, identify gaps in existing institutional, legal, regulatory, financing frameworks and policies, and establish a consensus on the ways forward with stakeholders.

Map stakeholders. Stakeholder mapping should start with other government departments and agencies with a stake in the blue economy, including departments related to economic development, environmental protection and climate mitigation and adaptation, as well as water agencies, utilities, regulators, basin organisations, etc. Beyond government departments, public, private and non-profit actors in the blue economy can improve the representativeness and legitimacy of the assessment process. Once the lead team has mapped stakeholders and considered their responsibilities, core motivations and interactions between them, the lead team should engage with stakeholders in the assessment.

Organise targeted workshops with key stakeholders to perform the assessment. The workshops bring together blue economy stakeholders to vote on the RISC dimensions and the enabling conditions, share their views and compare them to those of other stakeholders, and build a consensus on the adjustments needed to blue economy policy. The number of workshops may change depending on the opportunities for stakeholders to provide input between workshops and to build consensus on the assessment and actions needed.

During each workshop, the lead team and stakeholders should:

Allow time to present the OECD RISC Assessment Framework and key concepts.

Vote and discuss on the score around:

The level of resilience, inclusiveness, sustainability and circularity (RISC-proof) of the blue economy in the city or region (Part 1).

The level of progress towards implementing the enabling governance conditions for a RISC‑proof blue economy in their city or region (Part 2).

In Parts 1 and 2, respondents should indicate their assessment by ticking the corresponding box in each table with a score. The potential scores range from Levels 1 to 4, listed in Table 4.1.

Collect additional information (e.g. examples and sources) from stakeholders to document the responses further. Consider expanding the scope of data collection by integrating insights from diverse external indicators, such as blue economy sector trends and expert analyses.

To reflect the diversity of opinions, the lead organisation reports the level of consensus among stakeholders during the voting process for each question by selecting the answer that corresponds to the level of agreement (Table 4.2).

Table 4.1. RISC Assessment Framework scoring process

|

Scoring |

Assessment of the resilience, inclusiveness, sustainability and circularity of the blue economy at the subnational level (Part 1) (4 categories with 11 questions in total) |

Assessment of the level implementation of the enabling governance conditions for a RISC-proof blue economy at the subnational level (Part 2) (3 categories with 9 questions in total) |

|---|---|---|

|

Level 1 |

Not resilient, inclusive, sustainable and/or circular |

Poor level of implementation of the enabling governance condition |

|

Level 2 |

Moderately resilient, inclusive, sustainable and/or circular |

Fair implementation of the enabling governance condition |

|

Level 3 |

Mostly resilient, inclusive, sustainable and/or circular |

Good level of implementation of the enabling governance condition |

|

Level 4 |

Highly resilient, inclusive, sustainable and/or circular |

Excellent level of implementation of the enabling governance condition |

Consider repeating this process regularly (e.g. annually). Progress towards a RISC-proof blue economy can be measured using the first RISC Assessment Framework as a baseline against which to compare a second assessment. Repeating the evaluation regularly (e.g. annually) can help engage stakeholders in the blue economy over time. However, it should be noted that changes in the enabling conditions may take more than one year to be implemented and reflected in the assessment results.

Table 4.2. Assessing the level of consensus among stakeholders

|

Do the assessment results show a consensus among stakeholders? |

||

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

Weak consensus |

Acceptable consensus |

Strong consensus |

The pilot testers flagged three points of attention for subnational governments using the framework:

1. Allow enough time to identify, map and convene blue economy stakeholders adequately since the blue economy involves a plethora of government and non-government actors. Pilot testers suggested involving government entities linked to cross-cutting issues (e.g. regional or local economic development and planning, coastal, basin and water and stormwater management, natural resources and biodiversity, forestry and parks) as well as blue economy sectors themselves (e.g. fisheries, ports, tourism, etc.). Non-government stakeholders would include blue economy businesses and players such as fishers, local communities, Indigenous communities, non-governmental organisations (NGOs), knowledge and research institutions, academia and media to support transparency and accountability.

2. Involve national governments if possible. Several pilot testers suggested that this would increase the relevance of the assessment given that responsibilities for blue economy sectors and governance are shared across levels of government. According to pilot testers, relevant ministries or departments would include those related to: local and regional development; finance; environment; water and sanitation; science, technology and innovation; transport; fisheries; and related entities (e.g. environmental protection agencies, port and harbour authorities, water authorities and resources commissions, and national statistical services).

3. Allow enough time to collect relevant data and information, which is often scattered across different government entities and non-government actors. Pilot testers suggested collecting data and information from existing policies, strategies and plans, as well as regional and national climate projections (e.g. ARClim and Futuros Territoriales platforms in Chile), geospatial data and other government departments and stakeholders.

Source: Based on OECD (2020[2]), Synthesis Report: The Circular Economy in Cities and Regions, https://doi.org/10.1787/10ac6ae4-en.

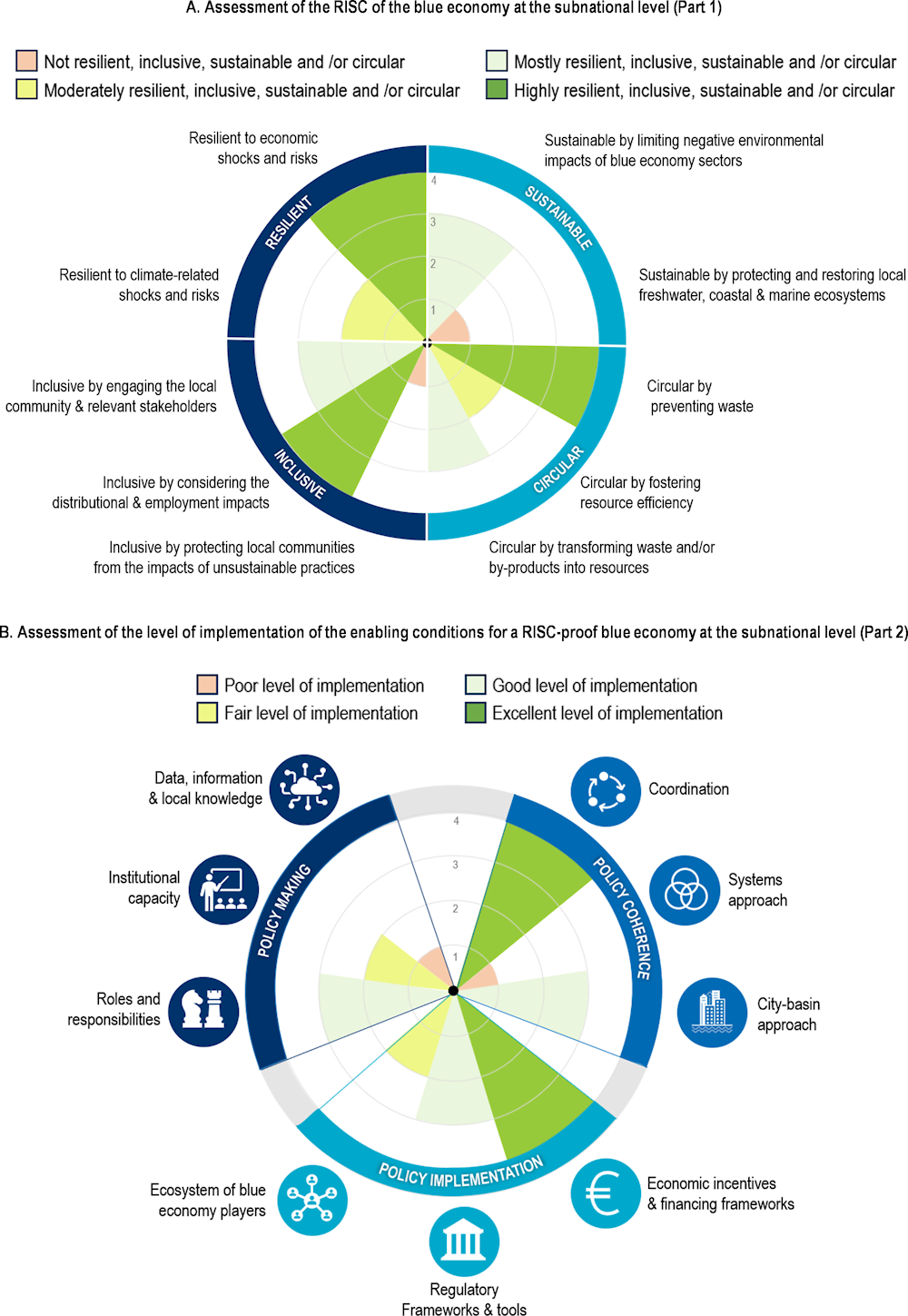

A visual representation of the results obtained with the RISC Assessment Framework is provided in Figure 4.3. It allows an overview of the RISC-proof level of the blue economy in the city or region (Panel A) and the level of implementation of the enabling governance conditions for a RISC-proof blue economy in the city of region (Panel B). This helps visually identify on which dimensions the city or region is performing best and where improvements are needed.

Figure 4.3. Example of a visualisation of the RISC Assessment Framework results

Source: Based on OECD (2020[2]), Synthesis Report: The Circular Economy in Cities and Regions, https://doi.org/10.1787/10ac6ae4-en.

Part 1. Assessment of the resilience, inclusiveness, sustainability and circularity of the blue economy at subnational level

Resilience

|

What? |

Definition |

Resilience reflects the ability of blue economies to prepare, absorb and recover from a range of shocks, risks or threats, in particular economic shocks and risks (e.g. economic crises, inflation) and climate-related events (e.g. floods, storms or droughts), which particularly affect water-dependent blue economies |

|||||

|

Why? |

Rationale and selected examples of benefits |

Economic and social shocks and stresses can negatively impact local gross domestic product (GDP) and jobs tied to the blue economy (e.g. shipping and tourism during the COVID-19 pandemic), and disruptions to strategic blue economy sectors (e.g. seafood, shipping or water-based energy) can have implications for food and energy security. Additionally, because they take place in and depend on freshwater, coastal and marine ecosystems and the services they provide, blue economy sectors are particularly vulnerable to climate-related shocks and stresses. For example, floods on land can introduce pollutants and invasive species into freshwater and coastal ecosystems, droughts and storms can generate changes in ocean salinity, disrupting marine biodiversity, and water scarcity can concentrate pollutants in rivers and lakes. A resilient blue economy can:

|

|||||

|

How? |

Assessment questions |

1. In your view, to what extent is the blue economy in your city/region resilient to economic shocks and risks (e.g. economic crises, inflation, supply chain disruptions, etc.)? 2. In your view, to what extent is the blue economy in your city/region resilient to climate-related shocks and risks (e.g. floods, storms, cyclones, landslides or droughts, etc.)? Please select one of the following options: |

|||||

|

Highly resilient |

Mostly resilient |

Moderately resilient |

Not resilient |

||||

|

Additional questions for discussion |

In your city, region or basin:

|

||||||

|

Additional sources of information (selected examples of indicators available online) |

Indicator |

Source |

Scale |

||||

|

Regions and Cities Statistical Atlas

|

Regional, local |

||||||

|

Copernicus Climate Data Store

|

National, regional |

||||||

|

Aqueduct Water Risk Atlas

|

National, regional, local |

||||||

|

Global Resilience Index |

National, regional, local |

||||||

Note: The resilience-related indicators presented in this table are additional and non-exhaustive sources of information at the national, regional and local levels that can be considered by subnational governments.

Inclusiveness

|

What? |

Definition |

Inclusiveness refers to the ability of cities and regions to engage with local communities and relevant stakeholders in decision making related to the blue economy and water security, consider the distributional and employment impacts of green policies on the blue economy and protect local communities (especially vulnerable groups) from the impacts of unsustainable blue economy practices. |

|||||

|

Why? |

Rationale and examples of benefits |

The voices of local communities (especially vulnerable groups, such as low-income groups, women, children, the elderly, the disabled, migrants, ethnic minorities and Indigenous peoples, depending on local context) are often poorly considered in decision-making processes, potentially leading to suboptimal policy outcomes. For example, nature-based solutions can be planned in ways that exacerbate inequality, especially when designed with a focus on economic development and return on investment, which can lead to the neglect of social benefits and drive social exclusion. Additionally, because the digital and green transitions can have adverse impacts on local jobs in the blue economy (e.g. driving down jobs in sectors such as port activities or offshore oil and gas), considering the impacts of green policies on the local blue economy and workers is vital to ensure that digital and green transitions are just. Similarly, the impacts of unsustainable blue economy practices (e.g. overfishing, illegal fishing, unsustainable coastal development, lack of wastewater treatment, water pollution, etc.) on local communities, especially the most vulnerable, should be considered in blue economy policies to avoid costs related to well-being and health. An inclusive blue economy can:

|

|||||

|

How? |

Assessment questions |

1. In your view, to what extent is the blue economy in your city/region inclusive by engaging the local community and relevant stakeholders in blue economy policy making and implementation? 2. In your view, to what extent is the blue economy in your city/region inclusive by considering the distributional and employment impacts of green policies on the blue economy? 3. In your view, to what extent is the blue economy in your city/region inclusive by protecting local communities (especially the most vulnerable) from the impacts of unsustainable blue economy practices (e.g. overfishing, illegal fishing, unsustainable coastal development, lack of wastewater treatment, water pollution, etc.)? Please select one of the following options: |

|||||

|

Highly resilient |

Mostly resilient |

Moderately resilient |

Not resilient |

||||

|

Additional questions for discussion |

In your city, region or basin:

|

||||||

|

Additional sources of information (selected examples of indicators available online) |

Indicator |

Source |

Scale |

||||

|

Regional Income Distribution and Poverty Database

|

National, regional |

||||||

|

Regional Economy Database

|

National, regional |

||||||

Note: The resilience-related indicators presented in this table are additional and non-exhaustive sources of information at the national, regional and local levels that can be considered by subnational governments.

Sustainability

|

What? |

Definition |

Sustainability refers to the ability of cities and regions to limit the adverse environmental impacts of the blue economy, while protecting blue ecosystems and biodiversity. |

||||

|

Why? |

Rationale and examples of benefits |

Blue economy sectors and related practices risks (e.g. overfishing, unsustainable fishing practices, oil spills, ballast water discharge from ships and the discharge of untreated wastewater) can have adverse impacts on blue ecosystems, including the depletion of fish stocks, habitat destruction and biodiversity loss. For example, unsustainably designed energy infrastructure, such as hydropower dams, can prevent fish migration and the flow of sediments, and offshore energy infrastructure can damage natural habitats. The blue economy can also hinder blue ecosystem services such as food provision, storm surge mitigation and water purification. Additionally, most blue economy sectors contribute to air pollution and greenhouse gas emissions and, thus, climate change, further exacerbating disruptions to the water cycle. A sustainable blue economy can:

|

||||

|

How? |

Assessment questions |

1. In your view, to what extent is the blue economy in your city/region sustainable by limiting negative environmental impacts of blue economy sectors (e.g. greenhouse gas emissions, overfishing, untreated sewage discharge or air pollution) through policy measures (e.g. regulations, standards, incentives, investments, capacity-building programmes, etc.)? 2. In your view, to what extent is the blue economy in your city/region sustainable by protecting and restoring local freshwater, coastal and marine ecosystems (e.g. natural river systems, wetlands or mangroves) through policy measures (e.g. regulations, standards, incentives, investments, capacity-building programmes, etc.)? Please select one of the following options: |

||||

|

Highly sustainable |

Mostly sustainable |

Moderately sustainable |

Not sustainable |

|||

|

Additional questions for discussion |

In your city, region or basin:

|

|||||

|

Additional sources of information (selected examples of indicators available online) |

Indicator |

Source |

Scale |

|||

|

Regions and Cities Statistical Atlas Database

|

Regional, local |

|||||

|

Green Growth Database

|

National |

|||||

|

Sustainable Ocean Economy Database

|

National |

|||||

|

Data Platform on Development Finance for the Sustainable Ocean Economy

|

National |

|||||

|

Water Database

|

National |

|||||

Note: The resilience-related indicators presented in this table are additional and non-exhaustive sources of information at the national, regional and local levels that can be considered by subnational governments.

Circularity

|

What? |

Definition |

Circularity refers to the ability of cities and regions within the blue economy to prevent waste, to use resources (e.g. natural resources, materials) efficiently and keep them in use for as long as possible, and to transform waste and/or byproducts into resources. |

||||

|

Why? |

Rationale and examples of benefits |

Blue economy sectors can be major consumers of materials and disposers of waste, thus contributing to the depletion of natural resources (including freshwater) and damaging freshwater, coastal and marine ecosystems through waste generation and pollution. A circular blue economy can:

|

||||

|

How? |

Assessment questions |

1. In your view, to what extent is the blue economy in your city/region circular by preventing waste through policy measures (e.g. regulations, standards, incentives, investments, capacity-building programmes, etc.)? 2. In your view, to what extent is the blue economy in your city/region circular by fostering efficient resource use and keeping resources in use for as long as possible through policy measures (e.g. regulations, standards, incentives, investments, capacity-building programmes, etc.)? 3. In your view, to what extent is the blue economy in your city/region circular by transforming waste and/or by-products into resources through policy measures (e.g. regulations, standards, incentives, investments, etc.)? Please select one of the following options: |

||||

|

Highly circular |

Mostly circular |

Moderately circular |

Not circular |

|||

|

Additional questions for discussion |

In your city, region or basin:

|

|||||

|

Additional sources of information (selected examples of indicators available online) |

Indicator |

Source |

Scale |

|||

|

Regions and Cities Statistical Atlas

|

Regional, local |

|||||

|

Circular Economy Database

|

National |

|||||

|

Environment - Cities and Greater Cities Database

|

Local |

|||||

Note: The resilience-related indicators presented in this table are additional and non-exhaustive sources of information at the national, regional and local levels that can be considered by subnational governments.

Part 2. Assessment of the implementation of the enabling conditions for a RISC‑proof blue economy at the subnational level

Policy making

Clarify roles and responsibilities for blue economy policy

|

What and why? |

Governments should clarify roles and responsibilities for RISC-proof blue economy policy (including water and marine policy) in legal and institutional frameworks, and co‑ordinate across levels of government to avoid gaps, overlaps and inefficiencies. |

|

|

How? |

Assessment question |

Does the local or regional government clearly define roles and responsibilities for RISC-proof blue economy policy? |

|

Level 1 |

There is no clear allocation of roles and responsibilities for blue economy policy in the local or regional government. |

|

|

Level 2 |

Roles and responsibilities for blue economy policy are defined in legal and institutional frameworks but not implemented in practice. There is a lack of clarity and understanding of roles and responsibilities among the entities concerned. |

|

|

Level 3 |

The responsibility for blue economy policy is clearly assigned to a lead department and several other departments and agencies are involved but there is a lack of effective communication and co-ordination. |

|

|

Level 4 |

The local or regional government demonstrates clear leadership in blue economy policy. Roles and responsibilities are clearly defined in legal and institutional frameworks, and government departments and agencies co-ordinate effectively with one another. |

|

|

Examples of suggested actions |

Clearly define roles and responsibilities in legal and institutional frameworks in terms of blue economy policy making, implementation and operational management. . |

|

|

Where gaps and overlaps are identified, clarify the roles and responsibilities of local and regional governments with national ones. |

||

|

Ensure that government departments and agencies co-ordinate effectively with one another and communicate updates regularly through co-ordination mechanisms. |

||

|

Acknowledge local specificities, contexts and heritage in the design of policies that affect the blue economy |

||

Match the level of institutional capacity to blue economy policy needs

|

What and why? |

Governments should match the level of government capacity to RISC-proof blue economy policy needs to ensure effective policy design and implementation. |

|

|

How? |

Assessment question |

Do relevant government departments and entities (e.g. regulatory, water or environmental agencies) have adequate capacities and skills for RISC-proof blue economy policy making and implementation? |

|

Level 1 |

There is a low level of awareness, human resources and technical capacities on the blue economy and related policies within the lead department for blue economy policy and across the local or regional government. |

|

|

Level 2 |

The lead department for blue economy policy has a fair level of capacity for blue economy policy making and implementation, but other departments and agencies with a stake in the blue economy (e.g. water or environmental agencies) are lagging. Some capacity-building activities (e.g. creation of guidance, training) for the local or regional government are planned. |

|

|

Level 3 |

The local or regional government has good capacities and skills for blue economy policy making and implementation. It takes part in capacity-building activities (e.g. training and education programmes, peer learning networks). |

|

|

Level 4 |

The local or regional government has strong capacities and skills for blue economy policy making and implementation and is recognised as an example to follow at the national and international levels. |

|

|

Examples of suggested actions |

Promote the education and training of civil servants on the blue economy through dedicated training programmes (e.g. from higher levels of government, international associations or NGOs) and peer-to-peer learning (e.g. international networks of cities and regions and policy fora on the blue economy). |

|

|

Provide civil servants with technical support and guidelines for implementing blue economy policy. |

||

|

Implement policies to attract and retain talent with merit-based, transparent processes that are independent from political cycles. |

||

Collect, analyse and share data and information and local knowledge

|

What and why? |

Governments should support the collection, analysis and disclosure of sufficiently timely and granular socio-economic and environmental data that can be used to inform, assess and adjust RISC-proof blue economy policy when needed. |

|

|

How? |

Assessment question |

Are data and information on the blue economy collected, analysed and shared in a sufficiently granular and timely way to inform, assess and adjust a RISC-proof blue economy policy? |

|

Level 1 |

The local or regional government does not collect or have access to sufficiently granular and timely socio-economic and environmental data to inform blue economy policy and it does not share information on the blue economy publicly. |

|

|

Level 2 |

The local or regional government has an understanding of the impacts of the blue economy (e.g. in terms of GDP, jobs and greenhouse gas emissions) thanks to the analysis of broader socio-economic and environmental indicators at functional the national and subnational levels, but it does not have dedicated blue economy indicators. The government has mapped existing indicators and datasets across private, public and civil society sources and identified new indicators to be collected. |

|

|

Level 3 |

The local or regional government has carried out a socio-economic and environmental assessment on the impact of the blue economy (e.g. in terms of GDP, jobs and greenhouse gas emissions) at the subnational level and is defining a framework for the systematic collection and dissemination of data to inform, assess and adjust blue economy policy. |

|

|

Level 4 |

The local or regional government has a dedicated data and information system for blue economy policy that is sufficiently granular and timely to effectively inform, assess and adjust blue economy policy. |

|

|

Examples of suggested actions |

Map existing indicators and data sources (including private, public and civil society ones) and identify gaps, as in many cases, data are available but fragmented across different sources, and collect new indicators where needed. |

|

|

Build trust and encourage data sharing from third parties that might be reluctant by defining guidelines and regulatory frameworks to ensure data privacy and security. |

||

|

Ensure that timely and regularly updated data and information on the blue economy is publicly available, preferably on a single platform. |

||

|

Ensure that data and information effectively feed into policy making, including periodically reviewing data collection, using and sharing methods to identify overlaps and synergies and track unnecessary data overload. |

||

|

Engage in local knowledge-sharing and bottom-up learning, including indigenous knowledge, to feed into blue economy policy and acknowledge local specificities, contexts and heritage. |

||

Policy coherence

Ensure effective co-ordination across water and marine ecosystems

|

What and why? |

Governments should foster effective co-ordination across government departments and agencies in charge of oceans and freshwater to ensure a RISC-proof blue economy from source to sea. |

|

|

How? |

Assessment question |

To what extent do local or regional government departments or agencies responsible for freshwater policy and ocean policy co-ordinate to ensure a RISC-proof blue economy? |

|

Level 1 |

The local or regional government has specific departments or agencies responsible for freshwater policy and ocean policy but they do not co-ordinate with one another. |

|

|

Level 2 |

The local or regional government has specific departments or agencies responsible for freshwater policy and ocean policy that co-ordinate on an ad hoc basis. |

|

|

Level 3 |

The local or regional government has specific departments or agencies responsible for freshwater policy and ocean policy that co-ordinate on a regular basis. |

|

|

Level 4 |

The local or regional government has either brought together ocean and freshwater departments or agencies under a single roof or it has specific departments or agencies responsible for ocean and freshwater that co-ordinate regularly and effectively. |

|

|

Examples of suggested actions |

Create ad hoc co-ordination bodies, such as committees, commissions, agencies or working groups. |

|

|

Organise ad hoc co-ordination meetings when needed. |

||

|

Draw up cross-sectoral plans with jointly designed and implemented measures benefitting both entities. |

||

|

Share data, knowledge and best practices to enhance understanding of the interconnectedness between freshwater and marine ecosystems and support evidence-based decision making. |

||

Nurture a systems approach to blue economy policy

|

What and why? |

Governments should nurture a systems approach to RISC-proof blue economy policy to overcome fragmentation, manage trade‑offs between sectors and align blue economy policy objectives with economic and environmental ones. |

|

|

How? |

Assessment question |

Is blue economy policy linked to and coherent with other sectoral policies (e.g. climate mitigation, adaptation, economic development, etc.) in terms of strategies, plans and programmes developed by the local or regional government? |

|

Level 1 |

The local or regional government is defining or has defined a formal or informal vision for the blue economy but it is not connected with other relevant policy sectors and related strategies or programmes and objectives. |

|

|

Level 2 |

The local or regional government has defined a formal or informal vision for the blue economy but it is poorly connected with other relevant policy sectors and related strategies or programmes and objectives. |

|

|

Level 3 |

The local or regional government’s long-term vision for blue economy policy establishes clear links with other relevant sectoral policies but it does not always align with the objectives of related strategies or programmes. |

|

|

Level 4 |

The local or regional government’s long-term vision for blue economy policy is coherent with several other relevant sectoral policies and aligned with corresponding objectives, strategies and programmes. |

|

|

Examples of suggested actions |

Leverage systems approaches to policy making for the blue economy. |

|

|

Meaningfully engage with public, private and non-profit blue economy players from all sectors by mapping actors with a stake in the blue economy, defining the expected use of stakeholder inputs and adapting the type and level of stakeholder engagement to needs, paying particular attention to involving under-represented groups (e.g. low-income or informal workers, women, youth, etc.) and mitigating risks of consultation capture from over-represented or overly vocal categories. |

||

|

Consider defining a formal long-term vision for the blue economy in co-ordination with relevant departments and stakeholders involved in the design and implementation. |

||

|

Identify, assess and address barriers to policy coherence using monitoring, reporting and reviews as well as cross-departmental co-ordination mechanisms. |

||

Promote a “city-basin” approach to water resources management

|

What and why? |

Governments should promote a “city-basin” approach to water resources management to enhance water security (i.e. maintain acceptable levels of the risks of too much, too little, too polluted water and disruption to freshwater systems) from source to sea, to the benefit of the RISC-proof blue economy. |

|

|

How? |

Assessment question |

To what extent does the local or regional government take part in water resources management at the basin scale, through a “city-basin” or “region-basin” approach with its local basin organisation, to foster a RISC‑proof blue economy? |

|

Level 1 |

The local or regional government does not have a local basin organisation or does not interact with its local basin organisation. |

|

|

Level 2 |

The local or regional government interacts with its local basin organisation on an ad hoc basis, with a view to managing water resources sustainably. It does not yet consider the implications for the blue economy. |

|

|

Level 3 |

The local or regional government plays an active role in water resources management by interacting regularly with its local basin organisation. It considers the impacts of the blue economy on the basin system (including the coast) and the impacts of water security in the basin on the local blue economy. |

|

|

Level 4 |

The local or regional government and the basin organisation have a strong relationship that plays a crucial role in achieving a RISC-proof blue economy and sustainable water resources management. The government implements measures to address the impacts of water security in the basin on the local blue economy. It takes part in a range of activities with the basin organisation, including decision making, stakeholder engagement, data collection and funding. |

|

|

Examples of suggested actions |

Take part in the governance structure of the basin organisation, from simply taking part in meetings to sitting in and/or advising executive committees, voting or making decisions. |

|

|

Take part in water resources management planning activities with the basin organisation, including consultations and other forms of engagement for designing, implementing and monitoring basin management plans. |

||

|

Exchange data and information relative to water security in the basin (e.g. monitoring indicators for bathing water quality). |

||

|

Jointly fund upstream or downstream projects (e.g. support farmers in reducing pesticide use and support local communities protecting headwaters) to improve water security in the basin, city and/or region. |

||

Policy implementation

Set sound economic incentives and financing frameworks

|

What and why? |

Governments should set sound economic incentives and financing frameworks to catalyse financial resources for the RISC-proof blue economy, allocate them efficiently and “tip the playing field” in favour of more sustainable blue economy sectors or practices and more resilient freshwater, coastal and marine ecosystems. |

|

|

How? |

Assessment question |

Does the local or regional government mobilise and allocate financial resources for the RISC-proof blue economy efficiently and effectively through economic incentives and financing frameworks? |

|

Level 1 |

The local or regional government does not have a framework for prioritising and allocating financial resources for the blue economy. It does not leverage economic tools to foster a RISC-proof blue economy, and counter-productive instruments (e.g. fossil fuel subsidies or subsidies harmful to biodiversity) can be in place. |

|

|

Level 2 |

The local or regional government has an understanding of the economic and financial instruments that foster a RISC-proof blue economy and makes some use of them. |

|

|

Level 3 |

The local or regional government is planning to define a financing framework for the RISC-proof blue economy and already leverages a range of economic instruments and tools to mobilise and allocate financial resources efficiently. |

|

|

Level 4 |

The local or regional government has a clear financing framework, including sound economic incentives, in place for the RISC-proof blue economy, allowing the efficient and effective prioritisation and allocation of financial resources for the blue economy. |

|

|

Examples of suggested actions |

Implement economic tools that foster sustainable blue economy sectors and resilient blue ecosystems while raising revenues, such as taxes applying the polluter-pays principle, charges, fees and payments for ecosystem services. |

|

|

Clarify existing financing opportunities at the national (e.g. subsidies, grant funding, loans, loan guarantees, tax credits, green and blue bonds, etc.) and international (e.g. international loans and grant funding) levels by liaising with the national government. |

||

|

Channel funding and financing to public entities, businesses and civil society related to the blue economy through grants, subsidies, loans, loan guarantees and waivers on local taxes. |

||

|

Support sustainable blue economy start-ups and small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) by launching customers, facilitating access to public and private funds (e.g. through awareness raising, training and having a single window for such information), implementing green public procurement and making public tenders more accessible to start-ups and SMEs (e.g. by dividing tenders into smaller lots or explicitly prioritising SMEs). |

||

|

Allocate funds efficiently by clearly defining financing priorities or a financing strategy for the blue economy and removing counter-productive, environmentally harmful subsidies (e.g. fossil fuel subsidies, subsidies harmful to biodiversity, etc.). |

||

Leverage regulatory frameworks and command-and-control tools

|

What and why? |

Governments should leverage regulatory frameworks and command-and-control tools to balance RISC-proof blue economy activity with environmental and social protection. |

|

|

How? |

Assessment question |

Does the local or regional leverage regulatory tools (e.g. licenses, permits, standards, restrictions, bans, etc.) to balance blue economy activity with environmental protection? |

|

Level 1 |

The local or regional government makes very little or no use of regulatory tools to balance blue economy sector activity with environmental protection. |

|

|

Level 2 |

The local or regional government uses regulatory tools on an ad hoc basis to manage trade-offs between blue economy activity and environmental protection but in practice they are not always implemented. |

|

|

Level 3 |

The local or regional government leverages regulatory tools to manage blue economy sector activity while limiting adverse environmental impacts. Regulations are followed and regulatory tools are generally implemented in practice. |

|

|

Level 4 |

The local or regional government has a comprehensive set of regulatory tools in place that allow it to manage trade-offs between blue economy sectors and environmental protection and are systematically enforced. |

|

|

Examples of suggested actions |

Review regulations that affect the blue economy at the subnational level, identifying gaps and overlaps. |

|

|

Leverage all regulatory tools and incentives available within the jurisdiction, such as licenses, authorisations, permits and permit trading schemes, restrictions, extended producer responsibility, environmental impact assessments and offsetting requirements. |

||

|

Ensure adequate enforcement and compliance through inspections and non-compliance penalties to give regulatory tools full force. |

||

Build an “ecosystem” of blue economy players

|

What and why? |

Governments should strive to build effective ecosystems of blue economy players, including businesses, research and knowledge institutions, universities, public entities and civil society, to drive sustainable growth and a just transition within the RISC-proof blue economy. |

|

|

How? |

Assessment question |

Does the local or regional government foster innovation networks that gather different players (e.g. public research institutes, large businesses, SMEs, universities and other public agencies) to work together on innovations fostering a RISC-proof blue economy? |

|

Level 1 |

The local or regional government does not facilitate connections between different blue economy players across different sectors and institutional settings. It has not carried out a mapping of blue economy stakeholders in the city or region. |

|

|

Level 2 |

The local or regional government facilitates connections between blue economy players on an ad hoc basis and has an understanding of the blue economy “ecosystem” of actors in the city or region. It often facilitates connections on a sectoral basis. |

|

|

Level 3 |

The local or regional government facilitates connections between blue economy players through informal mechanisms such as meetings or the sharing of contact details. |

|

|

Level 4 |

The local or regional government has a formal innovation network in place that favours the systematic connection of blue economy players between themselves. The innovation network is in line with the government’s RISC-proof blue economy policy objectives. |

|

|

Examples of suggested actions |

Create innovation networks that combine a diversity of blue economy players (e.g. public research institutes, large businesses, SMEs, universities and other public agencies) into flexibly organised networks working on various scientific and technological innovations across different blue economy sectors. |

|

|

Mainstream the blue economy in existing entrepreneurship and employment programmes. |

||

|

Ensure that local education and training programmes related to the blue economy match the needs of the blue economy. |

||

|

Raise public awareness of the blue economy to enhance ocean literacy, especially among youth, through targeted communications, such as awareness-raising campaigns, events, employment fora and activities in schools. |

||

Part 3. “Whole of water” checklist for the blue economy

The blue economy, which is based in and depends on healthy coastal, marine and freshwater environments, is strongly dependent on good “whole of water” management, an approach that links freshwater and ocean systems with the surrounding human settlements and their accompanying activities and structures. As a result, blue economy activities and infrastructure are particularly vulnerable to water-related shocks and stresses, the cascading effects of which are magnified by climate change. At the same time, blue economy sectors can deteriorate freshwater and seawater quality and disrupt blue ecosystems and the services they provide, thus weakening overall water security.

The “whole of water” checklist (Table 4.3) aims to guide governments in considering both the impacts of water-related risks on the blue economy and the impacts of the blue economy on freshwater, coastal and marine ecosystems. By focusing on water-related impacts of the blue economy, the checklist leverages 15 years of OECD work on water governance as part of the OECD Water Governance Programme.

As a complement to Parts 1 and 2, the checklist proposes a list of ten actions that governments and stakeholders can consider to build a resilient, inclusive, sustainable and circular blue economy strategy that fosters water security. It can be used as part of the design phase of a blue economy strategy or policy to brainstorm or engage in dialogue and co-ordinate with blue economy stakeholders (e.g. businesses, universities, river basin organisations, local communities, etc).

Table 4.3. The “whole of water” checklist

|

1. |

Conduct a vulnerability or risk assessment to determine geographical hotspots for water-related risks, shocks and stresses, the vulnerability of infrastructure related to the blue economy (e.g. ports, water supply and sanitation systems, transport networks, etc.) and the vulnerability of blue economy sectors (e.g. fisheries, tourism) to water-related risks of too much, too little and too polluted water. |

|

2. |

Identify the main forms of blue ecosystem degradation due to blue economy sectors (e.g. unsustainable fishing practices, untreated sewage and/or wastewater from all sectors, single-use plastics from tourism and shipping, unsustainably designed water-based energy infrastructure, etc.), including potential implications for local communities, especially vulnerable groups. |

|

3. |

Assess the freshwater abstraction and consumption levels of blue economy sectors and their impact on freshwater availability, including potential implications for local communities, especially vulnerable groups (e.g. women, youth, the elderly, migrant or informal workers, Indigenous peoples, ethnic minorities, etc.). |

|

4. |

Ensure coherence between land use plans, basin management plans, coastal zone management plans and marine spatial plans to enhance resilience to water-related risks. |

|

5. |

Consider measures to minimise the adverse impacts of water-related shocks and stresses on the blue economy, such as short-term contingency measures to ensure critical infrastructure and services (e.g. ports) in case of shocks (e.g. floods), offsetting mechanisms (e.g. payments for ecosystem services) to improve marine and freshwater quality and ecosystem services (e.g. community-led blue carbon projects) and the management of the entire urban water cycle. |

|

6. |

Consider measures to limit the negative impacts of blue economy sectors on blue ecosystems (e.g. plastic pollution, untreated wastewater discharge, illegal fishing, overtourism and excessive coastal development) with instruments such as single-use plastic bans on beaches, fish catch quotas, restrictions on fishing gear and practices, design standards and licensing rules for energy infrastructure, urban planning rules that limit the impacts of waterside development on blue ecosystems, a city tax on tourism, mandating the tertiary treatment of wastewater from tourist accommodation, etc. |

|

7. |

Consider different water demand management tools, a demand management strategy and a communication strategy to reach all blue economy sectors in the event of a drought. |

|

8. |

Facilitate the use of nature-based solutions to protect blue ecosystems and enhance resilience to water risks, including by updating land use planning frameworks and rules (e.g. to reduce permeable surfaces, increase setbacks and improve drainage systems), enhancing government capacity (e.g. to facilitate the uptake of nature-based solutions in procurement) and leveraging adequate funding and financing tools. |

|

9. |

Ensure that bulky waste from blue economy sectors (e.g. from coastal and waterside development, shipbuilding, and waterborne vessels in general) is recovered, recycled and adequately treated to avoid environmental leakage, including into blue ecosystems. |

|

10. |

Consider measures to transform by-waste from blue economy sectors (e.g. by-waste from seafood processing, sludge from sewage and wastewater treatment) into resources for other economic activities to avoid environmental leakage, including into blue ecosystems. |

References

[2] OECD (2020), The Circular Economy in Cities and Regions: Synthesis Report, OECD Urban Studies, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/10ac6ae4-en.

[1] OECD (2018), Implementing the OECD Principles on Water Governance: Indicator Framework and Evolving Practices, OECD Studies on Water, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264292659-en.