This chapter highlights the challenges that Quebec must meet in order to improve the transparency of the information disclosed in the Lobbyists Registry and to allow for public scrutiny over the policy development process. First, the chapter analyses the registration process and suggests ways to improve the content and granularity of the information declared by lobbyists in the registry. The chapter also discusses how to maximise the technological environment of the Lobbyists Registry as a vehicle for transparency and compliance. Second, the sharing of responsibilities for transparency between lobbyists and public officials is also discussed. Lastly, the chapter provides recommendations for the effective implementation of disclosure requirements and regular review of their application, in order to best meet stakeholder expectations and developments in lobbying.

The Regulation of Lobbying in Quebec, Canada

2. An approach to transparency of lobbying activities based on the relevance of the information declared

Abstract

Introduction

Transparency is the disclosure and subsequent accessibility of relevant public data and information (OECD, 2017[1]). It is a tool for public scrutiny of the policy-making process. The OECD Recommendation on Principles for Transparency and Integrity in Lobbying (hereafter "the Recommendation") therefore encourages countries and jurisdictions to provide an adequate degree of transparency to ensure that public officials, citizens and businesses can obtain sufficient information on lobbying activities (Principle 5), while taking into account the administrative burden of compliance, so that this does not become an impediment to fair and equitable access to government. (Principle 2). In particular, jurisdictions are encouraged to facilitate the monitoring of lobbying activities by stakeholders, including civil society organisations, businesses, the media and the general public (Principle 6) (OECD, 2010[2]).

In Quebec, transparency of lobbying activities is provided through the registration of persons making influence communications in the Lobbyists Registry. In order to fully achieve the objective of transparency of influence communications set out in section 1 of the Act, The Quebec Commissioner of Lobbying considers that the relevance of the information declared in the Lobbyists Registry must be a pillar of any future reform of the Act, while preserving a balance between transparency requirements and the reality of lobbying activities.

Furthermore, transparency objectives cannot be achieved if disclosure requirements are not respected by the actors concerned and properly implemented by the supervisory bodies. The OECD Recommendation therefore calls on countries to implement a coherent spectrum of strategies and practices to achieve compliance with transparency measures (Principle 9). The Recommendation also calls on countries to periodically review the application of their lobbying rules and guidelines and make necessary adjustments in light of experience (Principle 10).

This chapter analyses the transparency of information on lobbying in Quebec. Specifically, it examines the procedures for registering in the Lobbyists Registry, the relevance of the information declared, the technological environment as a vehicle for transparency and accountability, and the strategies implemented to ensure compliance with the transparency rules. The chapter also discusses mechanisms for raising awareness of the expected rules and standards, as well as the periodic review of the transparency framework to allow for adjustments in light of experience.

Clarify registration and disclosure procedures for all actors involved

The OECD Recommendation states that the public has a right to know how public institutions and public officials made their decisions, including, where appropriate, who lobbied on relevant issues (Principle 6 of the Recommendation). It also states that information on lobbying activities and lobbyists should be stored in a publicly available register (Principle 5 of the Recommendation). In order to achieve this objective, it is important to clarify the registration and disclosure requirements for actors subject to transparency obligations, including:

Registration as a prerequisite for the exercise of any lobbying activity.

Registration deadlines.

The persons or entities responsible for registration.

Possible adjustments to take account of the scale and nature of the lobbying sector.

The Act could specify that timely registration should be a prerequisite for any lobbying activity

Currently, any lobbyist covered by the Lobbying Transparency and Ethics Act must register in the Lobbyists Registry. This provision allows the Québec regime to be in line with international best practices. Indeed, voluntary registries or initiatives by lobbyists' associations remain limited in their impact (OECD, 2021[3]; OECD, 2014[4]). In most OECD countries that have established a transparency register, the registration of lobbyists is mandatory to conduct lobbying activities. Where registration is voluntary, such as in the Netherlands or the European Union, registration is required for access to certain public officials or public buildings, such as parliament. Similarly, in all US and Canadian jurisdictions that have instituted a transparency register, registration is also mandatory.

Currently, section 25 of the Act states that no person may lobby a public office holder without being registered in the registry of lobbyists in respect of such lobbying activities. Returns to the registry are made based on the duration of lobbying activities, corresponding to a period covered by the lobbying activities, which must include the name of any parliamentary, government or municipal institution in which any public office holder is employed or serves with whom the lobbyist has communicated or expects to communicate, as well as the ministerial, deputy-ministerial, managerial, professional or other nature of the functions of the public office holder;

In its Statement of Principles, the Quebec Commissioner of Lobbying considers that all individuals and entities must be required to register in the disclosure system established by the Act if they wish to carry out lobbying activities with or without an intermediary (Principle 8 of the Statement of Principles). This implies that entities and individuals wishing to engage in lobbying activities must register at the stage of intending to engage in such activities, and not after they have done so or within a limited time frame.

To pursue this objective, section 25 of the Act could be clarified to provide that a lobbyist may only engage in these activities if he or she is registered in the registry in respect of these activities within the time and in the manner prescribed by the Act or by regulation. These clarifications are essential in order to clarify the role of public office holders, particularly with respect to the verification that the lobbyist who lobbies the office holder complies with his or her obligation to disclose the activities in the Lobbyists Registry. Section 25 could also specify that a lobbying activity may only be carried out if the name of the public institution for which the public office holder with whom the lobbyist intends to communicate or has communicated is registered by the lobbyist within the prescribed time. This proposal, already considered by the Quebec Commissioner of Lobbying in its previous recommendations, would not only ensure timely access to such information, but also provide public officials with clear guidance on the interactions they are allowed to have with lobbyists. This aspect will be covered in Chapter 3.

The Act could reduce and harmonise registration deadlines for all lobbyists

Currently, the Quebec Lobbyists Registry is based on the principle of disclosure of the intent to conduct lobbying activities. Section 14 of the Act specifies different registration deadlines for consultant lobbyists and organisation lobbyists. In the case of a consultant lobbyist, registration must be made no later than the thirtieth day after the day on which the lobbyist begins to lobby on behalf of a client. In the case of an enterprise lobbyist or an organisation lobbyist, the deadline is 60 days.

These registration deadlines could be an obstacle to the objective of transparency and timely access to registration information, and could also be confusing for some public office holders who may wish to verify a lobbyist's registration before entering into communication with him or her (this issue will be addressed in Chapter 3). Several elected officials and leaders of public institutions interviewed by the Quebec Commissioner of Lobbying in 2018 raised the need to shorten the registration period, so that the lobbyist's registration can be verified before a meeting or within a few days of the interaction.

The Act could impose a shorter registration period, and apply the same period to all lobbyists, which could be derived from good practices in other Canadian jurisdictions, such as British Columbia's Lobbying Act, Newfoundland and Labrador's Act, and Toronto's and Ottawa's municipal systems (Table 2.1). This harmonisation of registration deadlines is also recommended by the Office of the Commissioner of Lobbying of Canada to improve transparency, ensure that all registrations are made in a timely manner and increase fairness between different categories of lobbyists (Office of the Commissioner of Lobbying of Canada, 2021[5]).

Table 2.1. Registration deadlines in Canadian provinces and some municipalities

|

Jurisdiction |

Registration deadlines for consultant lobbyists |

Registration deadlines for in-house lobbyists |

|---|---|---|

|

Canada (federal law) |

10 days |

2 months |

|

British Columbia |

10 days |

10 days |

|

Alberta |

10 days |

2 months |

|

Saskatchewan |

10 days |

60 days |

|

Manitoba |

10 days |

2 months |

|

Ontario |

10 days |

2 months |

|

Quebec |

30 days |

60 days |

|

New-Brunswick |

15 days |

2 months |

|

Prince Edward Island |

10 days |

2 months |

|

New England |

10 days |

2 months |

|

Newfoundland and Labrador |

10 days |

10 days |

|

Yukon |

15 days |

60 days |

|

City of Ottawa |

15 working days |

15 working days |

|

City of Toronto |

3 working days |

3 working days |

The registry should place the obligation to register on entities, not individuals, while including the identity of each lobbyist

In Quebec, registration is made, in the case of a consultant lobbyist, by the lobbyist himself and, in the case of an enterprise lobbyist or an organisation lobbyist, by the senior officer of the enterprise or group on whose behalf a lobbyist is acting. However, the registration of more than one enterprise lobbyist or organisation lobbyist may be done by filing a single return containing the information pertaining to each of these lobbyists. The current Act therefore places all the obligations related to the transparency of their activities on individuals, without recognizing that these activities are carried out for the benefit of an enterprise, an organisation or another individual. Furthermore, the records filed in the registry by consultant lobbyists are filed in the name of the lobbyist and not in the name of the corporation that was mandated to carry out the lobbying activities.

In its Statement of principles, the Quebec Commissioner of Lobbying proposes to assign the represented entities the responsibility of authorising any interest representative to carry out lobbying activities on its behalf and of ensuring the disclosure, truthfulness, reliability and follow-up of lobbying activities performed by their in-house interest representatives (Principle 9 of the Statement of Principles), and to assign external interest representatives the responsibility of ensuring the disclosure, truthfulness, reliability and follow-up of lobbying activities made on behalf of their clients (Principle 10 of the Statement of Principles). This proposal would, on the one hand, make external interest representatives - as legal persons, except in the case of an individual acting as an independent lobbyist - responsible for disclosing all activities carried out on behalf of their clients, which is already provided for in the law, and on the other hand, place the responsibility for registration, disclosure and monitoring of all lobbying activities on legal persons.

This proposal would ensure better access to the information contained in the register. To this end, entities can be designated by a unique identifier or reference number. Such a unique reference is also foreseen in the new registration platform being developed by the Quebec Commissioner of Lobbying, which was inspired by the approach adopted in France (Box 2.1). According to the draft terms and conditions of the Lobbyists Registry, any enterprise or organisation will have to have a "collective space" when an enterprise or organisation lobbyist engages in lobbying activities on its behalf; similarly, any consultant lobbyist's enterprise will have to have its collective space. To create this collective space, the Quebec enterprise number assigned by the Enterprise Register of Quebec must be used (Lobbyisme Québec, 2019[6]).

Box 2.1. Registration of interest representatives in France

In France, interest representatives must communicate their identity to the High Authority for Transparency in Public Life by entering their SIREN number (national company identifier) or their identification number in the national register of associations (RNA) in the teleservice provided for registration. If they do not have either of these two numbers, they can contact the High Authority's services via the teleservice to communicate their identity and be given an identification number to register.

Next, the names of the legal representatives who have the necessary prerogatives to act on behalf of the organisation and represent it in relation to third parties, whether or not they carry out interest representation activities, must be communicated to the High Authority. The identity of persons considered to be "in charge of interest representation activities" within a legal person is also recorded.

Finally, for interest representatives who carry out activities wholly or partly on behalf of third parties, the clients for whom interest representation activities are carried out must be disclosed.

These new arrangements for registering entities in the registry should make it easier to find accurate information about entities in the registry, whether the activities are registered by an in-house lobbyist or by an external lobbyist, and to avoid duplication.

In keeping with these developments, it will be important that any future review of the Act be able to shift the registration requirement from individuals to entities. This will further reduce the administrative burden of registration by allowing all entities employing enterprise, organisation or consultant lobbyists to designate a registrar to consolidate, harmonise and report on the activities of the entity. The Act could also maintain the obligation to disclose in the registry the names of all individuals who have engaged in lobbying activities. Such a disclosure regime would also allow an entity to be held accountable for potential breaches of the Act. This aspect is discussed later in the chapter.

The Act could give entities the option of assuming responsibility for reporting lobbying activities carried out by their member entities

Under the current Act, when an organisation adopts strategic orientations that are then the subject of lobbying activities with public institutions by the member entities of that organisation, each member entity must register those activities in the registry, which can create numerous duplications in the registry. In its discussions with several organisations subject to the Act, the Quebec Commissioner of Lobbying has noted the difficulties encountered by groups of organisations and the need to simplify disclosure requirements. In its Statement of Principles, the Commissioner recommends the implementation of an "umbrella disclosure", allowing an entity to disclose, for a specific mandate, the entirety of the lobbying activities undertaken by the individuals or entities that are its members, by assuming, on their behalf, the responsibility for and conformity of the lobbying activities (Principle 20 of the Statement of Principles). For example, an entity could report all activities of its subsidiaries or related entities. In the case of NPOs, federations, trade union organisations and groupings of organisations, whose primary mandate is to represent their members, could also report lobbying activities for their members.

However, this measure must be clarified to avoid any risk of regulatory loopholes. First, the Act should clarify that this umbrella disclosure should only apply to interest representation that is coordinated and/or determined at the level of the entity that brings together member entities. All other lobbying activities that are coordinated by a particular member on its own behalf should be subject to disclosure by that specific entity, not by the entity of which it is a member.

Secondly, the Act could require the umbrella entity to disclose on behalf of which specific interests or members the lobbying activities are being carried out. Indeed, it is generally accepted that organisations such as federations or business associations lobby on behalf of all their members. However, in practice, there may be an unwritten rule among members that allows some companies to lobby for their positions when key regulatory issues in their sector are discussed, and this often results in the most active and vocal members' views being adopted, even if they are sometimes in the minority. Therefore, it seems essential to strengthen the disclosure rules of umbrella organisations so that the specific beneficiaries of an advocated position that may represent minority interests within such an entity are disclosed, so that minority interests are not misrepresented as those of the general membership.

Thirdly, the Act could require that umbrella entities must contain the names of the organisations that form the entity; member entities, when registering, should also indicate in the register the organisations of which they are members, which could facilitate cross-checking information in the register. Such a provision exists for example in France, which requires all interest representatives to disclose "the professional or trade union organisations or associations related to the interests represented" to which they belong.

Lastly, the Act should clarify that the obligation to register umbrella entities applies regardless of the number or status of the employees of that entity. Currently, the Act covers coalitions and groupings to the extent that they are organisations formed for employer, trade union or professional purposes or if their members are predominantly for-profit companies. As specified in Chapter 1, all coalitions should be required to register when they engage in lobbying activities. The Act could clarify that this principle applies even to coalitions that do not have full-time employees. Similar recommendations have been made in Ireland by the Standards in Public Office Commission, which oversees the Lobbying Act, regarding the registration of coalitions and interest groups representing commercial interests (Box 2.2).

Box 2.2. Irish recommendations on communications by unpaid persons who hold office in bodies representing professional and/or business interests

In Ireland, representative bodies and coalitions representing professional and/or business interests are only covered by the Lobbying Act if they have one or more full-time employees.

However, the Standards in Public Office Commission has noted that there are a number of representative bodies that exist primarily to represent the interests of their members, but do not have full-time employees and are therefore not subject to the Act. This means that some bodies/associations that regularly communicate with public office holders are not covered by the Act, despite the fact that in some cases their members would fall within the scope. Organisations that represent members who are therefore independently within the scope of the law are able to avoid the registration requirement, simply because the representative body has no employees.

The Commission has also noted a number of cases where informal coalitions of business interests have been formed to lobby as a group on an issue of mutual interest to the industry. These informal coalitions usually have a name but in most cases do not have employees. The Commission found examples of such coalitions in the airline sector, software companies and in the entertainment and leisure sector. In such circumstances, where the coalition has no employees, it is not necessary for it to register.

Whether or not these coalitions or informal bodies were formed with the intention of circumventing the provisions of the law, their lobbying activities fall outside the scope of the law and are not made transparent. The Commission has made several recommendations that any business representative body or 'coalition' of business interests, regardless of the number or status of employees, should fall within the scope of the Act, provided that one or more of the members of the body or coalition would fall within the scope if they were acting themselves. The Commission also considers that the members of the body/coalition should be required to be named in the declarations in order to promote greater transparency.

Source: Standards in Public Office Commission, 2019 Legislative Review of the Regulation of Lobbying Act 2015: Submission by the Standards in Public Office Commission, https://www.lobbying.ie/about-us/legislation/2019-legislative-review-of-the-regulation-of-lobbying-act-2015-submission-by-the-standards-in-public-office-commission/.

The registration of non-profit organisations should not include the names of volunteers engaged in lobbying activities

The OECD Recommendation states that basic disclosure requirements should take into account the scale and nature of the lobbying sector, particularly where there is limited supply and demand for professional lobbying, and the administrative burden of compliance, so that this does not become an obstacle to fair access to the administration (Principle 2 of the Recommendation). While non-profit organisations active at federal and provincial level often have departments dedicated to lobbying, communication and public relations activities, this is not necessarily the case for small local organisations.

In order to clarify registration requirements for non-profit organisations, registration could be simplified with regard to the disclosure of the names of individuals engaged in lobbying activities. The registration should only disclose the names of individuals who are employees or who have been appointed to participate in the governing bodies (for example the board of directors), who would be responsible for ensuring the disclosure, veracity, monitoring and centralisation of lobbying activities carried out on behalf of the entity. Lobbying activities carried out by volunteers should be tracked and recorded without the names of the individuals acting as volunteers appearing in the register.

Strengthening the content of information reported to the register

The OECD Recommendation states that disclosure of lobbying activities should provide sufficient, pertinent information on key aspects of lobbying activities to enable public scrutiny. In order to adequately serve the public interest, the Recommendation states that information on lobbying activities and lobbyists should be stored in a publicly available register and regularly updated to provide accurate information for effective analysis by public officials, citizens and businesses (Principle 5 of the Recommendation). To achieve this objective, the Quebec legislator may consider the following key elements

The expectations of various stakeholders (citizens, public decision-makers, companies, shareholders, journalists, researchers) to better delimit the disclosure regime.

The basic disclosure requirements enabling public officials, citizens and businesses to obtain sufficient information on lobbying activities.

Measures to monitor lobbying activities through a system of regular disclosures.

The Quebec legislator could take into account the expectations of various stakeholders in order to define a relevant disclosure regime

The OECD Recommendation provides a set of guidelines for delineating core disclosure obligations as well as supplementary information taking into account legitimate information needs of key players in the public decision-making process (Principle 5 of the Recommendation). From this perspective, the expectations expressed in Quebec and internationally provide guidance on what is in the public interest to make transparent in a disclosure regime.

The OECD's interviews with various stakeholders revealed a consensus on the need to supplement the information currently reported to the registry, particularly on the targets of lobbying and the amounts invested. On the citizen side, interviews and focus groups conducted by the Quebec Commissioner of Lobbying in 2018 to develop the Statement of Principles revealed a growing demand to identify elected officials, managers or staff of public institutions who have been the target of lobbying activities. Some researchers interviewed by the OECD regretted that they could not assess, for example, the number of meetings between representatives of a specific industry and the ministry concerned over a given period of time, by comparing it with the number of meetings obtained by non-profit organisations on the same issues. Similarly, some journalists stressed the relevance of obtaining information on the amount of money invested annually in lobbying, in order to appreciate and compare the size of the lobbying sector in certain industries. Most of the stakeholders interviewed also stressed the need to indicate the specific decisions targeted by lobbying activities, in order to ensure the traceability of the public decision.

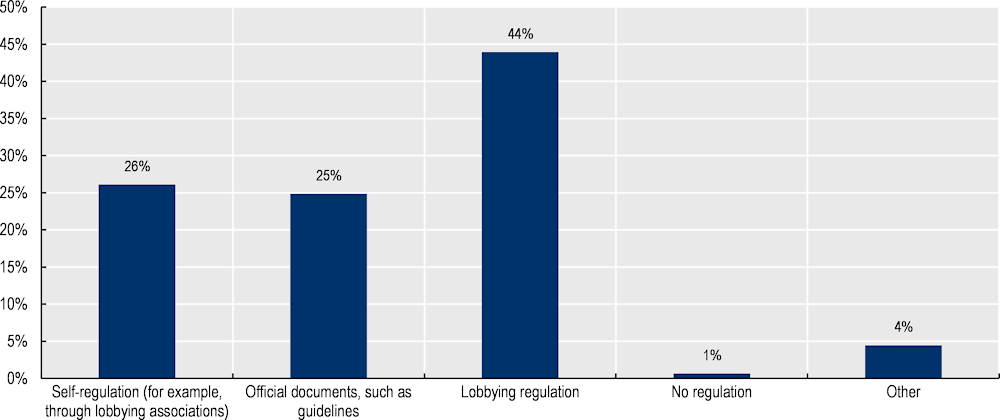

It is generally assumed that professional lobbyists oppose the creation of lobbying registers and the public disclosure of their lobbying activities. However, many lobbyists surveyed by the OECD in 20201 expressed a willingness to participate in a mandatory lobbyist registry, and many felt that this was necessary to protect the integrity of the profession (OECD, 2014[4]; OECD, 2021[3]). These attitudes reflect a commitment to integrity in public decision-making and the importance of maintaining public trust (Figure 2.1).

Figure 2.1. Best means for regulating lobbying, according to lobbyists

Source: Enquête de l’OCDE sur le lobbying (2020).

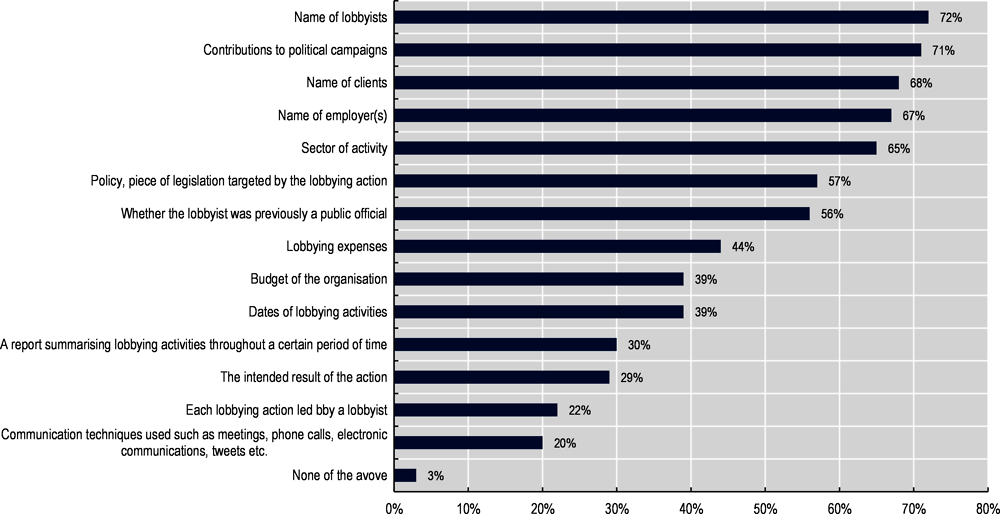

The same lobbyists surveyed by the OECD in 2020 were 71% of the opinion that lobbyists' contributions to political party funding should be made transparent (Figure 2.2). However, several Quebec lobbyists stressed in discussions with the OECD the need to strike a balance between making relevant information available to the public and protecting confidential information; legitimate exemptions should be considered to preserve certain information in the public interest or to protect commercially sensitive information if necessary.

Figure 2.2. In OECD countries, lobbyists favour disclosure of political campaigns contributions when registering lobbying activities

Source: OECD 2020 Survey on Lobbying.

Examining a company's lobbying activities has also become an increasingly common practice by some shareholders or institutional investors, as discussed in Chapter 1. For example, some shareholders of listed companies have become particularly active in recent years in passing resolutions that require increased transparency of lobbying activities. The content of these resolutions gives an indication of what is not always required in transparency registers but is considered relevant by these actors. In most cases, shareholders request disclosure of lobbying activities carried out, including any indirect lobbying or grassroots communications, as well as the amounts allocated to these activities (Ceres, 2021[7]; Principles for Responsible Investment, 2018[8]; Glass Lewis, 2021[9]).

Finally, interviews conducted by the Quebec Commissioner of Lobbying with parliamentary and municipal elected officials in 2018 showed that while they adhere to the principle of transparency of lobbying activities, some municipal elected officials stressed that transparency could compromise certain benefits. The OECD's interviews with parliamentarians confirmed these trends. The elected officials interviewed highlighted the undeniable progress made by the Lobbyists Registry, and the majority supported disclosure of the purpose of any lobbying activity, while expressing some reservations about the extent of information that should be declared so as not to increase the administrative burden or lead to an overabundance of information.

The current reporting obligations only imperfectly meet the transparency objectives of the Act and would benefit from being clarified to include the objective pursued and the public decision targeted

The OECD Recommendation states that core disclosure requirements should elicit information on in-house and consultant lobbyists, capture the objective of lobbying activity, identify its beneficiaries, in particular the ordering party, and point to those public offices that are its targets. Supplementary disclosure requirements might shed light on where lobbying pressures and funding come from (Principle 5 of the Recommendation). In other words, the OECD Recommendation encourages the disclosure of information on who is lobbying, on what and how (Table 2.2).

In his Statement of Principles, the Quebec Commissioner of Lobbying proposes to require all relevant information to be disclosed, including the identity of interest representatives and entities undertaking or benefiting from lobbying activities, public institutions targeted and all information, financial or otherwise, that is deemed relevant for understanding the goals of a lobbying activity and the means used to carry it out (Principle 17 of the Statement of Principles).

Currently, the Lobbying Transparency and Ethics Act already covers some of these elements and is therefore in line with international best practices. Returns in the registry are made in the form of "time periods" covered by lobbying activities. The Act requires the disclosure of the identity of the lobbyist and his or her employer, the subject matter and purpose of the lobbying activities, as well as the public institutions targeted by the lobbying activities and the means of communication that the lobbyists intend to use. The Act also requires disclosure of any person, corporation, subsidiary or association, who, to the knowledge of the lobbyist, controls or directs the activities of the client (in the case of a consultant lobbyist) and/or the employer (in the case of a consultant lobbyist and an organisation or enterprise lobbyist) and has a direct interest in the outcome of the lobbyist's activities. This provision could be complemented by the disclosure of any affiliation with a coalition or professional association, as well as the name of each member - where the member is a corporation - of such organisations, as they may also benefit from the lobbying activities (this recommendation is elaborated above). Finally, the Act requires the disclosure any financial compensation received by consultant lobbyists, by tranche of amounts paid.

Table 2.2. Who undertakes lobbying activities, on what and how?

|

Information to shed light on lobbying activities |

Lobbying Transparency and Ethics Act |

|---|---|

|

WHO - Information on lobbyists and beneficiaries |

|

|

Name of lobbyists |

✓ |

|

If the lobbyist was previously a public official |

✓ |

|

Name of lobbyists' employer |

✓ |

|

Business sector or sector of activities |

x |

|

Names of clients, if any |

✓ |

|

Parent or subsidiary company benefiting from the lobbying activities |

✓ |

|

Name of any members or affiliation with an association/organisation |

x |

|

Public funding received |

✓ |

|

WHAT - Objectives, decisions and targeted agents |

|

|

Targeted legislation, proposals, decisions or regulations |

x |

|

Identity of the targeted public institutions |

✓ |

|

Type of public official targeted (general nature of duties) |

✓ |

|

Identity of targeted public officials |

x |

|

Subject matter of lobbying activities |

✓ |

|

Objectives and desired outcomes |

✓ |

|

Objectives and results achieved |

x |

|

HOW - Details of communications or meetings with public officials |

|

|

Financial information |

✓ |

|

Communications and lobbying techniques used |

✓ |

|

Overview of lobbying actions undertaken |

✓ |

|

Each lobbying action undertaken |

x |

|

Specific date and/or location of communications |

x |

|

Political contributions |

x |

Notes : In the case of Quebec, the financial amounts dedicated to lobbying activities are only disclosed in the case of a consultant lobbyist. Lobbyists must select a range in which the amount or value of what has been received or will be received for lobbying activities falls: less than USD 10 000, USD 10 000 to USD 50 000, USD 50 000 to USD 100 000 and USD 100 000 or more.

Source: (Légis Québec, 2002[10]).

Although the Interpretation bulletin 2012-01 of the Commissioner of Lobbying requires lobbyists to provide sufficient details in relation to the time period and public decisions targeted (Lobbyisme Québec, 2012[11]), the Act does not explicitly require the disclosure of certain information that would help identify the specific public decisions being targeted. Nor is it required to specify the number of meetings or the frequency with which communications take place. This is because the Act requires the disclosure of lobbying activities at the stage of intent. Journalists interviewed for this report pointed out that the Lobbyists Registry at the federal level provides more information on the dates and target of lobbying activities, while the Quebec legal framework only requires a window of dates that is often too broad. Similarly, citizens interviewed in 2018 by the Quebec Commissioner of Lobbying pointed out that the disclosure of financial amounts at the stage of the intention of lobbying activities, and not of completed activities, could mislead them into believing that the lobbying activity had been carried out, whereas the amount is only an estimate.

In sum, the initial declaration could be simplified, for example by removing information that is not relevant at the stage of the intention to lobby, such as financial amounts. More precise information, such as the dates of lobbying activities, and the specific public officials and decisions targeted, could be required in regular updates, in order to allow citizens to fully grasp the scope and depth of these activities.

The initial return could also include information that is currently not disclosed but which may give relevant indications on the different means that can be mobilised for lobbying activities. For example, the disclosure of public funding received could be extended to any type of funding received, in order to shed light on the so-called astroturfing practices discussed in Chapter 1. Following the same model as the European Union, this disclosure should allow entities to provide either a link to an existing webpage providing information on funding received, or to detail this information in the register if it does not exist in the public domain. A similar recommendation had already been made by the Quebec Commissioner of Lobbying in 2012. The recommendation stated that a lobbyist's return should indicate the name of any person, enterprise or organisation that contributes, financially or otherwise, to a lobbying activity, as entities may have an interest in the lobbying activities of an interest group by contributing financially without having control or direction over the activities of that interest group.

The Act could provide for monitoring of lobbying activities by implementing regular disclosure mechanisms to ensure timely access to information on lobbying

The OECD Recommendation recalls that to adequately serve the public interest, disclosure on lobbying activities and lobbyists should be updated in a timely manner in order to provide accurate information that allows effective analysis by public officials, citizens and businesses. (Principle 5 of the Recommendation). In Quebec, regular disclosures are limited to an update of the information contained in the initial return (Table 2.3).

Table 2.3. Updating and renewal of the information of the initial return in Quebec

|

Current deadlines |

|

|---|---|

|

Registration renewal (consultant lobbyist) |

30 days after the anniversary date of the first registration |

|

Registration renewal (enterprise lobbyist or organisation lobbyist) |

60 days after the end of the financial year |

|

In the event of a change in the content of a lobbyist's declaration (e.g. termination of his or her engagement, taking up new activities) |

30 days (notice of change) |

Source: (Légis Québec, 2002[10]).

This lack of monitoring can be particularly problematic as disclosures are made at the stage of intent. It may hamper the possibility of public scrutiny, as the information disclosed does not allow stakeholders to monitor lobbying activities or to obtain precise indications of the activities that were effectively carried out, which are the only ones that have an impact on the public decision targeted. The declaration of intent in the initial declaration should therefore be followed up more closely, to validate whether the activity has taken place, been postponed or simply not followed up. In its Statement of Principles, the Quebec Commissioner of Lobbying recommends requiring the disclosure of any intention to undertake lobbying activities and the follow-up of any activity undertaken, especially if an elected official or an officer designated by a public institution is being lobbied (Principle 19 of the Statement of Principles).

In order to simplify the registry and reduce the administrative burden on the one hand, while improving the granularity of information on the other, Quebec could consider providing for a simplified initial registration, complemented by a requirement to publish regular activity reports on all lobbying activities conducted with an elected official or designated officer of a public institution. In Canada, for example, the requirement for lobbyists to publish monthly communications reports has resulted in the prompt publication of information on lobbying activities related to COVID-19 and the identification of the objectives of the lobbying activities as well as the policies and public officials targeted (Box 2.3).

Box 2.3. In Canada, the regular publication of communication reports has allowed for the timely disclosure of information

Recognising that "Canadians have a right to know who has communicated with the country's decision-makers during this unprecedented period" of COVID-19, the Office of the Commissioner of Lobbying of Canada has not granted any extensions and has issued regular reminders, including through social networks. In May 2020, the Office of the Commissioner of Lobbying of Canada also added a new feature to the Online Registry of Lobbyists, allowing users to view lobbying registrations related to COVID-19. The tool searches for the criteria "COVID-19", "COVID", "coronavirus" and "pandemic" in the subject line details of all lobbying registrations. Users can then filter the information by type of activity, topic and public institution targeted, and access the associated monthly communications reports. The Office has also issued guidelines on COVID-19 registration and emergency funding requirements to advise lobbyists whether an application for a federal funding program related to COVID-19 should be published, as well as the periods for updating the information.

The Quebec Commissioner of Lobbying recognised, however, that this type of requirement adds a considerable administrative burden to interest representatives and would be difficult to apply in Quebec, where the Act also covers the municipal level, the health and social services network and, potentially, the education network, as well as several non-profit organisations. Regular disclosure could thus be envisaged on a quarterly or semi-annual basis, as is the case in Ireland or the United States, for example (Table 2.4). The Commissioner had previously recommended in 2017 that lobbyists be required to declare, every three months, no later than January 15, April 15, July 15 and October 15, the results of their lobbying activities for the last quarter, in accordance with the procedures determined by the Commissioner. (Lobbyisme Québec, 2017[13]).

Table 2.4. Frequency of disclosure of communications and meetings between lobbyists and public officials in selected countries

|

Initial registration |

Updating and subsequent recording of information on lobbying activities |

|

|---|---|---|

|

Canada |

Lobbyists’ registration is mandatory to conduct lobbying activities:

|

Information must be updated every six months. If a communication has been made with a “designated public office holder”, a “Monthly return” must be filed, including: 1. The name of the designated public office holder who was the object of the communication. 2. The date of the communication. 3. Subject-matter of the communication. |

|

France |

Lobbyists’ registration is mandatory to conduct lobbying activities. Registration must be done within two months of the start of lobbying activities. |

When lobbying activities are carried out on behalf of a new client, the client’s identity must be registered within one month. Lobbyists must file “annual activity reports”, submitted within three months of the end of the lobbyist’s financial year. Lobbyists must file “annual activity reports”, submitted within three months of the end of the lobbyist’s financial year. The report contains the following information: 1. Types of public decisions targeted by lobbying activities. 2. Type of lobbying activities undertaken. 3. Issues covered by these activities, identified by their purpose and area of intervention. 4. Categories of public officials the lobbyist has communicated with. 5. The identity of third parties. 6. The amount of expenditure related to lobbying activities in the past year, identified by thresholds. |

|

Ireland |

Lobbyists’ registration is mandatory to conduct lobbying activities. Lobbyists can register after commencing lobbying, provided that they register and submit a return of lobbying activity within 21 days of the end of the first “relevant period” in which they begin lobbying (The relevant period is the four months ending on the last day of April, August and December each year). |

The 'returns' of lobbying activities are made at the end of each 'relevant period', every four months. They are published as soon as they are submitted and contain the following elements: 1. Information relating to the client (name, address, main activities, contact details, registration number). 2. The designated public officials to whom the communications concerned were made and the body by which they are employed. 3. The relevant matter of those communications and the results they were intended to secure. 4. The type and extent of the lobbying activities, including any “grassroots communications”, where an organisation instructs its members or supporters to contact DPOs on a particular matter. 5. The name of the individual who had primary responsibility for carrying on the lobbying activities. 6. The name of each person who is or has been a designated public official employed by, or providing services to, the registered person and who was engaged in carrying on lobbying activities. |

|

United States |

Lobbyists’ registration is mandatory to conduct lobbying activities. Registration is required within 45 days: (i) of the date lobbyist is employed or retained to make a lobbying contact on behalf of a client; (ii) of the date an in-house lobbyist makes a second lobbying contact. |

Lobbyists must file quarterly reports on lobbying activities and semi-annual reports on political contributions. Quarterly reports on lobbying activities (LD-2), include: 1. Specific issues on which the lobbyist(s) engaged in lobbying activities. 2. Houses of Congress and specific Federal Agencies contacted. 3. Disclosing the lobbyists who had any activity in the general issue area. |

Source: Recherches complémentaires par le Secrétariat de l’OCDE.

The content of regular disclosures could include the specific decision being targeted, the names of certain public officials designated as "designated officials" who have been the subject of an influence communication, as well as financial information on the resources allocated to lobbying activities. This type of identification of designated officials is already present in several Canadian jurisdictions, including at the federal level (Table 2.5).

Table 2.5. Monitoring of representations made to elected or designated officials in Canadian jurisdictions with lobbying legislations in place

Interest representatives must state whether they have made, or plan to make, representations to…

|

Member of Parliament |

Minister |

Staff member of a public institution |

|

|---|---|---|---|

|

Canada (Federal level) |

○ |

● |

● |

|

Alberta |

● |

● |

● |

|

British Columbia |

● |

● |

● |

|

Prince Edward Island |

● |

○ |

● |

|

New Brunswick |

● |

○ |

● |

|

New England |

● |

○ |

● |

|

Ontario |

● |

● |

● |

|

Saskatchewan |

● |

● |

● |

|

Newfoundland and Labrador1 |

● |

○ |

● |

|

Yukon2 |

● |

● |

● |

|

Manitoba |

○ |

○ |

○ |

|

Quebec |

○ |

○ |

○ |

|

● Yes |

9 |

6 |

10 |

|

❍ No |

3 |

6 |

2 |

1. In addition to members of the City Council of the City of St. John's.

2. In addition to deputy heads as defined in the Public Service Act.

Source: (Lobbyisme Québec, 2019[14]).

In most of these jurisdictions, there is a clear delineation of which public office holders are subject to these additional disclosure obligations, based on the nature of their duties or the degree of decision-making power they have. Canada is an example: if contact has taken place with a "designated public office holder", the interaction must be recorded in the Lobbyists Registry on a monthly basis, in a detailed "Monthly Communication Report", and include the names of the individuals contacted, the location of the meeting and the topics discussed during the exchange. The Quebec legislator could reflect on the categories of public office holders who could be concerned by additional disclosure obligations. In any case, it is recommended that the list of "designated public officials" be precisely delimited, publicly accessible and kept up to date. In Ireland, for example, each public body is required to publish and maintain a list of designated public officers under the Lobbying Act 2015; the Standards in Public Office Commission also publishes a list of public bodies with designated public officers on the lobbying website (Box 2.4). The Quebec Commissioner of Lobbying has already taken steps in this direction, as the new platform includes a list of specific functions adapted according to the level of government (parliamentary, governmental, organisations, municipal).

Box 2.4. Obligation to publish a list of designated public officials in Ireland

In Ireland, Section 6(4) of the Lobbying Act 2015 requires each public body to publish a list showing the name, rank and brief details of the role and responsibilities of each 'designated public official' of the body. This list must be kept up to date. The purpose of the list is twofold:

To enable members of the public to identify individuals who are designated public officials; and

To serve as a resource for lobbyists filing a return with the registry who may need to find contact information for a designated official.

The list of designated public officials should be prominently displayed and easily found on the home page of each organisation's website. This page should also contain a link to the lobbying register http://www.lobbying.ie.

Source: Standards in Public Office Commission, Requirements for public bodies, https://www.lobbying.ie/help-resources/information-for-public-bodies/requirements-for-public-bodies/.

In order to promote compliance and registration, the Quebec Commissioner of Lobbying could propose guidelines for lobbyists to monitor their lobbying activities. Such guidelines, in the form of monitoring guidance, exist for example in British Columbia and France (Box 2.5).

Box 2.5. “How to trace your lobbying activities” tool developed by the HATVP in France

Pursuant to Article 3 of Decree No. 2017-867 of 9 May 2017 on the digital directory of interest representatives, the latter are required to send the High Authority for Transparency in Public Life details of the activities carried out over the year within three months of the close of their accounting period. This annual declaration takes the form of a consolidated report by subject and declared in the form of returns on the disclosure platform.

Designate a "referent" responsible for consolidating, harmonising and declaring the activity returns in the teleservice

Designating a "referent" person, such as the organisation's operational contact, has several advantages: (i) the consolidation of representation actions is centralised and facilitated; (ii) the title of the objects is harmonised and therefore more coherent and intelligible; (iii) as the referent is previously trained on the directory, this avoids confusion and misinterpretation of the scope of application of the system; (iv) the online declaration is carried out by a single person; (v) internally, the organisation's employees have a clearly identified contact person for these issues.

Identify all persons likely to be qualified as "persons responsible for interest representation activities”

Identify a priori the persons likely to fall within the scope, on the basis of job titles and the tasks generally carried out.

Ask all identified persons to trace their communications with public officials.

After a period of six and then twelve months, analyse whether the required threshold has been reached;

Register the persons identified in the register and disclose their activities.

Implement an internal reporting tool

This tool must allow for the consolidation of all the information that should be included in the annual declaration of activities, in particular:

|

Date |

Indicate the date or period in which the advocacy action was carried out |

|

Action carried out by |

Indicate the name of the person in charge of interest representation activities who initiated the action |

|

Objet |

Indicate the objective of the interest representation action, preferably by indicating the title of the public decision concerned and using a verb (e.g. "PACTE law: increase the tax on ...") |

|

Area(s) of intervention |

Choose one or more areas of intervention from the 117 proposals (several choices possible, up to a maximum of 5 choices) |

|

Name of the public official(s) requested |

Indicate the name of the public official(s) requested |

|

Category of public official(s) requested |

Choose the type of public official(s) you want from the list (several choices possible) |

|

Category of public official(s) requested: Member of the Government or ministerial cabinet". |

If you have selected "A member of the Government or Cabinet", choose the relevant ministry from the list |

|

Category of public official(s) applied for: Head of independent administrative authority or independent administrative authority |

If you have selected "A head of an independent administrative authority or an independent administrative authority (director or secretary general, or their deputy, or member of the college or of a sanctions committee)", choose the authority concerned from the list |

|

Type of interest representation actions |

Choose the type of interest representation action carried out from the list (several choices possible) |

|

Time spent |

Indicate the time spent in increments of 0.25 of a day worked; 0.5 corresponding to a half day and 1 corresponding to a full day |

|

Costs incurred |

Indiquez tous les coûts liés au travail de représentation (commande d'une étude, invitation à déjeuner, etc.). |

|

Annexes |

Attach all necessary supporting documents: cross-reference to diary, working documents, email, expense report, etc. |

|

Observations |

Comments (optional) |

Lastly, the disclosure of financial information remains a marginal practice in Canada, and Quebec is the only province to require such disclosure with respect to compensation received by consultant lobbyists. However, disclosure of such information remains relevant. In the United States, the amounts spent on lobbying activities are systematically disclosed. In France and in the European transparency register, expenses are also disclosed in categories. In these jurisdictions, the disclosure of such information makes it possible to better measure the size of a certain lobbying sector and to identify imbalances in the forces of influence. The Quebec legislator could therefore consider maintaining this obligation, while extending it to in-house lobbyists of corporations and organisations, as well as to contingent fees, and requiring it only at the stage where the lobbying activities have actually taken place.

The vast majority of American jurisdictions also require the disclosure of any political contribution, financial or otherwise, to political parties or candidates. However, the Quebec Commissioner of Lobbying considers this obligation disproportionate and not a meaningful indicator in the Quebec context, as the legal framework in Quebec imposes a maximum donation of CAD 100 for each elector. As for the disclosure of lobbyists' political activities, the Charbonneau Commission had proposed to "protect the financing of political parties from influence in order to draw a line between legitimate influence relationships in a democratic society and others”. The Commission recommended, among other recommendations, that the Election Act specify that volunteer work must at all times be done personally, voluntarily and without consideration and require political entities to disclose in their annual financial report and in their return of election expenses the names of persons who have done volunteer work in the field of expertise for which they are usually remunerated, in order to prevent bogus volunteerism compensated by businesses. Similarly, the Commission recommended combating the use of nominees in political financing, which has allowed some companies to finance provincial and municipal political parties by asking their employees and relatives to make personal contributions that are reimbursed by the company, by requiring the identification of the political contributor's employer in the political parties' returns.

While these measures relate more specifically to electoral laws, political activities of companies or organisations (assimilated to third party interventions) can be considered as lobbying activities, and it may be relevant to include certain information in the register in order to provide clarification on where lobbying pressures and funding come from (Principle 5 of the OECD Recommendation). In addition, the interviews conducted by the OECD confirmed that the intervention of third parties, for example NPOs whose financing is not known, during the pre-election period, could constitute a significant risk. In this perspective, regular disclosures could be requested for political activities outside the election period for companies and organisations that lobby, which are not regulated in Quebec (Box 2.6).

Box 2.6. Regulation of partisan interventions by third parties in Quebec

Within the meaning of the electoral laws, it is prohibited for third-party groups, including any organisation acting neither on behalf of a political party nor on behalf of a candidate (businesses, NPOs, legal persons or partnerships, associations, unions, organisations or groups of persons) to make partisan interventions during an election period. An intervention is considered partisan if it offers visibility to a party or a candidate, for example by promoting or opposing the election of a candidate, and if it generates costs, for example the printing of documents, such as posters or pamphlets, as well as the creation of a website or the purchase of advertisements on social media.

These rules apply in provincial elections, in municipal elections in municipalities with a population of 5 000 or more, and in school elections. For example:

An individual may not print posters promoting a candidate at his or her own expense in the workplace or in any other public place.

A business may not buy an advertisement in a newspaper to denounce the position of a party or candidate on an issue.

A non-profit organisation cannot post a PDF brochure that rates the policies of candidates in its municipality on a scale of 1 to 10.

A union cannot pay for a Facebook ad that promotes or opposes a party or candidate policy.

An association cannot create a website to support a candidate or party, as there is a cost to creating and maintaining that website.

As of June 10, 2016, the Chief Electoral Officer has the power to claim from a political entity a contribution or part of a contribution for which he or she has convincing evidence that it was made contrary to election laws, regardless of when the contribution was made. In the interest of public transparency, the election laws further provide that the Chief Electoral Officer shall make public on his website, 30 days after the receipt of the claim for contributions to a political entity, various information related to those contributions as of June 10, 2016. Whether or not the political entity has made the repayment is also indicated.

Source: Élections Québec, Intervenir dans le débat électoral, https://www.electionsquebec.qc.ca/francais/municipal/financement-et-depenses-electorales/intervenir-debat-electoral.php.

In sum, more regular monitoring of lobbying activities could be required, while avoiding too tight timetables, which could increase the administrative burden of registration, as well as too extensive timetables, which could lead to disclosure of lobbying activities after the decisions targeted by the activities have been taken, thus altering the timeliness and relevance of information declared.

Maximising the technological environment of the Lobbyists Registry as a vehicle for transparency and accountability

In order to achieve broad stakeholder support for the Act, a key challenge is to design tools and mechanisms for the collection and management of information on lobbying practices, and to publish them in an open and reusable format allowing users to identify trends in the large volumes of data. To this end, it is important to facilitate the registration as well as the monitoring of lobbying activities by stakeholders, including civil society organisations, companies, the media and the general public.

The OECD Recommendation encourages jurisdictions to enable stakeholders – including civil society organisations, businesses, the media and the general public – to scrutinise lobbying activities, including through the use of information and communication technologies, such as the Internet, to make information accessible to the public in a cost-effective manner (Principle 6 of the Recommendation). The Recommendation also encourages providing lobbyists with convenient electronic registration and report-filing systems, facilitating access to relevant documents and consultations by an automatic alert system (Principle 9 of the Recommendation). In this perspective, it is necessary to:

Maximise the use of disclosure platforms to make the practical reality of lobbying visible.

Implement incentives for lobbyists when registering, in order to foster a culture of compliance.

Provide, depending on the resources available, automatic verification mechanisms to strengthen controls.

The Commissioner of Lobbying could maximise the use of the new platform to make the practical reality of lobbying more visible

In its Statement of Principles, the Quebec Commissioner of Lobbying stresses the need to establish a mandatory, public disclosure system for lobbying activities based on open data and providing free access, at all times, to relevant and verifiable information allowing anyone to be aware of and understand the lobbying activities and respond to them in a timely manner (Principle 16 of the Statement of Principles). To this end, online disclosure platforms should allow information to be properly structured to facilitate the understanding of lobbying activities and its analysis by users.

In June 2019, with the adoption of Bill 6, the Quebec Commissioner of Lobbying was given the responsibility of designing and administering a new, simple and effective platform to replace the current registry. This measure responds to the wishes expressed by the Commissioner, which recommended in its Statement of Principles to confer the responsibility and administration of the disclosure system on the Commissioner of Lobbying (Principle 18 of the Statement of Principles). The administration of the registry was previously entrusted to the Office of the Register of personal and movable real rights, under the Department of Justice, which acted as registrar of lobbyists. Above all, this measure is an important step towards easing the regulatory burdens on entities subject to transparency obligations.

Above all, this measure has enabled the Commissioner to initiate a process of revision of the Lobbyists Registry to improve the registration process and the technological environment. The Commissioner is expected to launch a new platform in 2022 to address, among other issues, the technological shortcomings of the current Lobbyists Registry (Box 2.7).

Box 2.7. Overview of improvements to the Quebec Lobbyists Registry planned for spring 2022

For citizens and registry users, the new platform will include several new features, including:

A clearer presentation of mandates in the form of detailed records, including the lobbyists who carry them out, the public decision-makers they try to influence during a given period, and any updates made.

A news feed allowing users to follow new registrations and thus to know about ongoing lobbying activities, including in relation to certain themes.

A better performing search tool allowing advanced searches according to predefined criteria (e.g. search by public institutions, by sector of activity, by registered entity etc.).

A personalised interface experience with the possibility to create a user account, allowing to save the results of certain searches, to program preferences and to receive notifications according to the programmed preferences.

A lobbying information area, including lobbying news, international comparisons, institutional announcements or communications, statistical reports.

For lobbyists, the platform aims to make registration easier and more efficient:

Lobbying activities over a time period can be registered and amended quickly and without delay by authorised persons. The Commissioner's checks will be ex-post, to allow timely transparency.

Formatted selection fields will limit the need to manually enter information, while others will be connected to certain public databases (e.g. the Enterprise Register, Légis Québec, etc.) in order to promote the consistency and validity of the information.

Lobbyists will have access to a Professional Space and a Collective Space, including reporting assistance processes for drafting, monitoring, updating and managing mandates, and allowing the collective drafting of a return before its publication.

From their Professional Space, lobbyists will be able to manage their returns on a simplified dashboard, which will display their profile, contact information, notifications, the mandates that concern them and the Collective Spaces to which they are attached.

Source: Commissaire au Lobbyisme du Québec, Registre des lobbyistes : aperçu des améliorations, https://lobbyisme.quebec/registre-des-lobbyistes/apercu-des-ameliorations/; Projet de modalités de tenue du registre des lobbyistes https://lobbyisme.quebec/fileadmin/Centre_de_documentation/Documentation_institutionnelle/projet-modalites-tenue-registre-lobbyistes.pdf

To define the contours of this new platform and meet the expectations of various stakeholders, the Quebec Commissioner of Lobbying conducted a public consultation on the terms and conditions of disclosures to the future lobbying disclosure platform, spread over 45 days from May 11 to June 21, 2021. A total of 15 persons submitted comments or questions, including 4 consultant lobbyists, 3 enterprise lobbyists, 5 organisation lobbyists, 1 citizen and 2 public office holders (Lobbyisme Québec, 2021[15]). The Commissioner also relied on a User Committee to provide advice in the development of the future platform, made up of representatives concerned with the regulation of lobbying in Quebec, including lobbyists, public office holders, journalists and individuals acting as citizens (Lobbyisme Québec, n.d.[16]). These efforts to engage all key players are a noteworthy good practice and contribute to a common understanding of the expected disclosure obligations. They also allow the Commissioner to better understand the factors that influence compliance with registration requirements, and to update enforcement strategies and mechanisms accordingly, which is a key principle of the OECD Recommendation (Principle 10 of the Recommendation). Most importantly, they help to better address the above-mentioned new expectations of various stakeholders regarding the transparency and integrity of lobbying activities.

Depending on the announced functionalities and when operational, this platform would be one of the best practices in force in OECD countries. The lobbying information zone, similar to the "Tout savoir sur le lobbying" (“Everything you should know about lobbying”) platform currently being implemented in France, will mainly document the practical reality of lobbying. The Commissioner has already implemented efforts in this direction, including:

The publication, every week, of statistics on the evolution of the number of registered lobbyists, active lobbyists, declarations or opinions, enterprises and organisations with at least one active lobbyist, active clients and active returns.

The sending of a newsletter every Monday ("Info Registre Hebdo"), allowing users to receive the most recent entries registered in the registry, and to obtain information on lobbying activities conducted with parliamentary, governmental and municipal public institutions.

The sending of a monthly newsletter on lobbying news (“Lobbyscope”).

The new platform will allow the Commissioner to pursue these efforts, for example by publishing dashboards and data visualisation systems to facilitate access and understanding of the large volumes of data collected in the registry. The Commissioner will also be able to use the data in the registry to produce targeted analyses on the practical reality of lobbying. In France, for example, the obligation to declare the objective of lobbying activities makes it possible to trace the influence communications made on a specific bill or decision (Box 2.8).

Box 2.8. Thematic analyses on lobbying published by the High Authority for transparency in public life in France

In 2020, the High Authority for the Transparency of Public Life implemented a new platform on lobbying. This platform contains practical factsheets, answers to frequently asked questions, statistics as well as thematic analyses based on data from the register.

For example, the High Authority has published two reports on declared lobbying activities on specific bills, which shed light on the practical reality of lobbying.

Source: HATVP, https://www.hatvp.fr/lobbying.

The registry could include incentive for lobbyists such as automatic reminders of disclosure obligations

Jurisdictions need to find innovative solutions to simplify registration and disclosure mechanisms and foster a culture of compliance. While the existence of a sanctions regime does act as a deterrent, the OECD Recommendation states that enforcement strategies and mechanisms should provide incentives for lobbyists, including automatic alert systems. Sending automatic reminders to lobbyists and public officials about disclosure obligations can help limit the risk of non-compliance (OECD, 2021[3]) (Box 2.9). A similar system could be implemented in Quebec.

Box 2.9. Automatic reminders to raise awareness of disclosure deadlines produce results

Australia

Registered organisations and lobbyists receive reminders about mandatory reporting obligations via biannual emails. Registered lobbyists are reminded that they must advise of any changes to their registration details within 10 business days of the change occurring, and confirm their details within 10 business days of 31 January and 30 June each year.

France

Interest representatives receive an email fifteen days before the deadline for submitting annual activity reports.

Germany

In the absence of updates for more than a year, interest representatives receive an electronic notification requesting them to update the entry. If the information is not updated it within three weeks, the interest representative’ is marked as "not updated".

Ireland

Registered lobbyists receive automatic alerts at the end of each of the three relevant periods, as well as deadline reminder emails. Return deadlines are also displayed on the Register of Lobbying’s main webpage.

United States

The Office of the Clerk of the House of Representatives provides an electronic notification service for all registered lobbyists. The service notifies, by email, of future filing deadlines or relevant information regarding disclosure-filing procedures. Reminders on filing deadlines are also displayed on the Lobbying Disclosure Website of the House of Representatives.

Source: (OECD, 2021[3])

The implementation of automatic verifications by the Lobbyists Commissioner could be useful in promoting public scrutiny

The use of data analysis and artificial intelligence can facilitate the verification and review of data, particularly with regard to the section on the objectives pursued by lobbying activities. In France, in addition to the electronic submission of registrations and activity reports, including features to facilitate disclosure, the High Authority for the Transparency of Public Life has implemented an automatic verification mechanism using an artificial intelligence-based algorithm to detect potential flaws in the validation of annual lobbying activity reports (Box 2.10). Given the similarities between the Quebec and French regimes with respect to the section concerning the objectives pursued by lobbying activities, a similar verification system could be implemented by the Commissioner of Lobbying.

Box 2.10. Implementation of an algorithm based on artificial intelligence technology to detect potential deficiencies and improve the quality of annual lobbying activity reports

In France, registered lobbyists must submit an annual activity report to the High Authority for Transparency in Public Life within three months of the lobbyist’s financial year. During the analysis of activity reports for the period 1 July 2017 to 31 December 2017, the High Authority noted the poor quality of some of the activity reports due to a lack of understanding of what was expected to be disclosed. Over half of the 6 000 activity reports analysed did not meet any of the expected criteria. Very often, the section describing the issues covered by lobbying activities – identified by their purpose and area of intervention – was used to report on general events, activities or dates of specific meetings.

In January 2019, the High Authority implemented a series of mechanisms to enhance the quality of information declared in activity reports. In addition to the provision of practical guidance explaining how the section on lobbying activities should be filled in and the display of a pop-up window with two good examples of how this section is supposed to be completed, the High Authority implemented an algorithm based on artificial intelligence technology to detect potential defects upon validation of the activity report, and detect incomplete or misleading declarations.

Source: (OECD, 2021[3])

Sharing responsibility for transparency with public decision-makers

The OECD Recommendation encourages jurisdictions to establish principles, rules and procedures that give public officials clear guidance on the relationships they are permitted to have with lobbyists (Principle 7 of the Recommendation). This is elaborated in more detail in Chapter 3. However, these principles could include a sharing of transparency obligations:

Through public agendas; or

Through the implementation of the legislative footprint.

The Quebec legislator could consider setting up open agenda initiatives for certain public officials

As in Quebec, the transparency measures introduced by countries generally assign the burden of disclosure to lobbyists through a lobbying registry. An alternative and potentially complementary approach is to assign this responsibility to public officials targeted by lobbying activities, requiring them to disclose information about their meetings with lobbyists, through a registry (Chile, Peru and Slovenia), open agendas (Spain, the United Kingdom and the European Union ) and/or by requiring public officials to inform their superiors of their meetings with lobbyists (Hungary, Latvia and Slovenia).

These 'open agenda' policies can include information about a public official's meetings, such as dates and times, stakeholders met and the purpose of the meeting. In countries that combine lobbying registers with open agendas (e.g. the United Kingdom and Romania), cross-checking the agendas and lobbying information from registers can provide an opportunity to further analyse who has tried to influence public officials and how (Box 2.11). In other countries, agendas are made available on request or in special circumstances. In Norway, the Ombudsman has stated that the right of inspection includes access to ministers' personal diaries (OECD, 2021[3]).

Box 2.11. Open agendas initiatives in Spain

In Spain, since 2012, the agendas of elected members of the Government are published online, on the Government website. The agenda lists daily the visits, interventions or meetings in which members of the Government participate. Each item discloses at least:

The minister in charge, and other minister(s) assisting.

The time of the meeting.

The organisation met or visited.

In October 2020, the Boards of both Houses of the Spanish Parliament adopted a Code of Conduct for members of the Congress and the Senate, which requires the publication of the Senators’ and Deputies' agendas, including their meetings with interest representatives. An agenda section is available on the webpage dedicated to each deputy.

Source: (OECD, 2021[3])

In Quebec, at the moment, the responsibility for transparency rests solely with lobbyists. Only the agenda of ministers is public and more or less detailed: the information is updated every three months, which does not allow for an adequate and timely level of transparency on the dates of the meetings held. Quebec could therefore consider legal reform to encourage public officials to publish their meetings with interest representatives (somewhat lower down the scale, such as cabinet directors and appointed officials). Since the current Lobbyists register does not indicate with whom the meeting took place within the public entity, or indeed whether it actually took place, this information could be relevant. Following the European model, the publication of these meetings, and not of the entire agenda, could be made mandatory for certain public officials: members of the government, members of cabinets, chairpersons of committees within the National Assembly (OECD, 2021[3]).

Disclosure of the normative footprint could also complement the information contained in the Lobbyists Registry