This chapter provides a definition of end-of-life care (EOLC), introduces the OECD framework for assessing EOLC, summarises key challenges in the provision of EOLC and policy options to improve them. It shows that while the need for EOLC is growing, access to care is still limited and unequal across and within countries. The lack of awareness around death and dying among professionals and patients hampers the provision of people‑centred services. Furthermore, people at the end of life would benefit from high-quality EOLC that addresses all symptoms and avoids under- or over‑treatment. While services have proven cost-effective, particularly in community settings, public financing is often partial and geared towards hospital settings. Informal or family caregivers would also benefit from more public support. The governance of EOLC shows room for improvement, as the pandemic has recently highlighted. Improving research, data and quality indicators would inform policy making and align EOLC services with people’s needs.

Time for Better Care at the End of Life

1. Assessment and recommendations

Abstract

Introduction

Before the COVID‑19 pandemic, close to 7 million people died every year in OECD countries and increasingly people die in old age. Realising that the end of life is near can be a devastating experience for individuals and their families. There are many ways to help people plan and die with dignity. End-of-life care (EOLC) help improve quality of life through relieving pain and other symptoms but also through helping address mental, emotional, and social needs. Such services are also a relief for relatives and friends, who often provide care, by giving emotional and practical help. Yet too often people are unable to access the care and support they need and that is in line with their wishes.

This report sets out policy challenges in end-of-life care, highlights examples of best practices in the provision of end-of-life care and brings together these findings to set out a framework for ensuring better end-of-life care. This report shows that, while many people want a peaceful end, without pain or distress, with loved ones and in familiar surroundings, this is not always the reality. People often do not die at home, which is the preferred place of death, because of lack of appropriate services and poor care co‑ordination. Access to end-of-life care services is unequal across and within countries and leads to very different experiences at the time close to death. Many people experience unnecessary pain and other symptoms, and they are not always consulted or treated with dignity. Overtreatment and undertreatment at the end of life can occur simultaneously and there is a great use of resources that do not necessarily improve the quality at the end of life (Sallnow et al., 2022[1]). Out-of-pocket expenditure is substantial during the last year of life and places a high burden on the family of the dying person.

The COVID‑19 pandemic has brought to stark prominence the reality of death. Across countries, overwhelmed health systems struggled to provide quality care and visiting restrictions reduced the responsiveness and people‑centredness of care (Marie Curie UK, 2021[2]). In some countries, end-of-life care during the pandemic was not sufficient, particularly in long-term care (LTC) facilities, and regarding emotional support. In many countries, registering people’s wishes and recording advance care planning was delayed. In others, there was insufficient access to pain medication or oxygen. The pandemic has highlighted the need to improve such services and make health systems more resilient and able to provide adequate quality services.

Key findings

Gaps remain in access to end-of-life care. Less than 40% of those in need of EOLC receive it across OECD countries. Addressing staffing shortages – including palliative care specialised doctors and nurses, primary care teams and long-term care workers trained in palliative care – and mechanisms for early screening for palliative care needs are a key factor to promote timely access.

Currently, a lack of appropriate information for populations and communication between professionals and patients to care make end-of-life care insufficiently people‑centred. Fewer than one in two adults in OECD countries report having some knowledge around EOLC. Communication on health status and care possibilities at the end of life occur less frequently than they should: less than half of people have such conversations with their doctor. Campaigns, improved training on communication and the use of multidisciplinary teams can contribute to a more people‑centred care. Further to training, decision-making processes at the end of life need also to be improved, including through closer involvement of people at the end of life and their relatives.

Quality of care is still too often too poor for people at the end of life. Alongside the under-treatment of their symptoms, people receive aggressive treatment that is not likely to provide comfort, prolong life or be cost-effective. This is the case for around one‑third of older patients with advanced irreversible diseases who are hospitalised at the end of life. People can experience high levels of distress, depression, and anxiety at the end of life, yet only half of the surveyed countries include psychologists within EOLC multidisciplinary teams. There is also insufficient measurement and benchmarking about the quality of end-of-life care across countries. Less than two‑thirds (63%) of 24 OECD countries have quality standards, and those which do exist are rarely binding or internationally comparable. Better quality standards to monitor and evaluate quality of life, also considering international comparisons will be key.

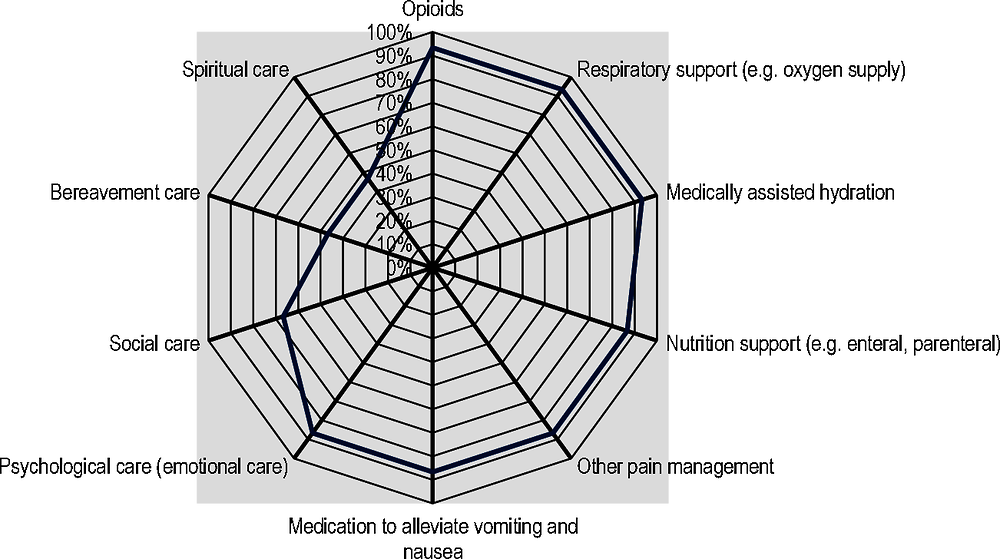

End-of-life care services are not always appropriately financed. While palliative care services have been shown to be cost-effective for health systems, public social protection schemes provide only partial coverage of expenses to alleviate the symptoms of end of life in just a third of the 21 surveyed countries, typically for some services such as opioids and other forms of pain management, for nutrition support and for medication to alleviate vomiting and nausea. Public funding of end-of-life care services is more predominant in hospitals, which likely influence the place of death and have an upward impact on public expenses. There is room to improve payment systems for end-of-life care services to improve value for money. Early access to palliative care services especially outside hospitals can both improve quality of end-of-life care and provide a better use of resources.

Finally, EOLC is not always well-governed and evidence‑based. Improving co‑ordination of services and the adaptability of health systems to increase access to end-of-life care services in case of extra demand due to emergencies. Besides increasing health workforce capacities, improving the use of advance care planning (ACP) and the availability of specific supplies in different care settings would allow carers to be better prepared for such events. Research in EOLC is insufficient and the data infrastructure to provide a full picture of end-of-life care across multiple services and data sets is still weak. Less than 30% of OECD countries have a national research agenda and less than 16% a local research agenda on the topic. Only 9 OECD countries collect data on EOLC that is integrated into other health and social systems. Countries could maximise the use of the wealth of available data by developing links across different datasets.

Population ageing and disease trajectories mean that end-of-life care needs will continue to rise.

End-of-life care refers to care provided to people who are in the last 12 months of life and receive palliative and curative care (Box 1.1 reports a more detailed definition of end-of-life care). This appears to be the timeframe most commonly adopted in definitions of end-of-life care (Hui et al., 2014[3]; Seow et al., 2018[4]) and this time period provides the opportunity to have Advance Care Planning discussions (Alliance for the Care of Dying People, 2014[5]; IKNL/Palliactief, 2017[6]) (for a definition of Advance Care Planning see Chapter 3). EOLC is considered to be the terminal stage of palliative care, provided in the very last period of a patient’s life (Cherny et al., 2003[7]; Helsinki University Hospital, 2020[8]). In addition to this, this analysis encompasses the actions intended to sustain or prolong life.

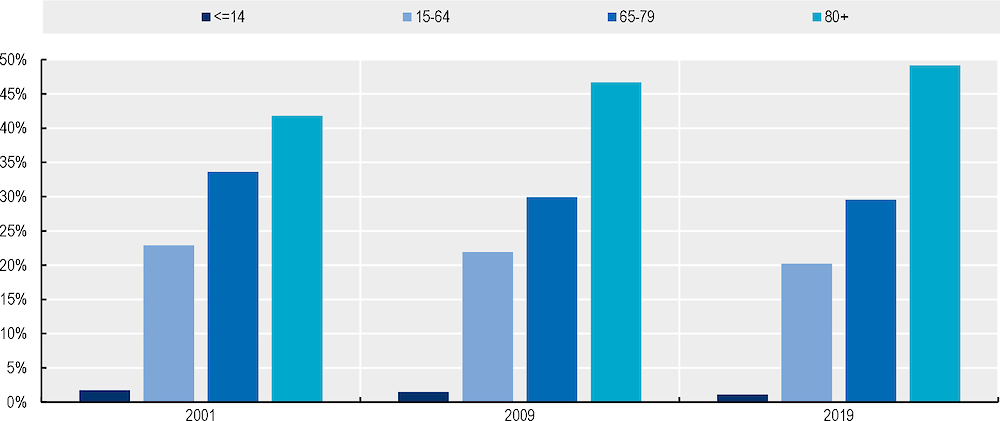

An ageing population will result in a growing share of the population likely to die from conditions that require end-of-life care. Because people are living longer, a growing share of the total number of deaths occur in the older population (Figure 1.1). Previous OECD analysis has highlighted the fast rise in the population aged 65 and over across OECD countries. The increase has been particularly rapid among the oldest old – people aged 80 years or older (OECD, 2019[9]). In 2001, 42% of deaths occurred in people over 80 years old, and by 2019 this had increased to 49%. With the proportion of people over 80 years old expected to double from 5% in 2017 to 10% in 2050 (OECD, 2019[9]), the number of people who will need access to quality EOLC across the OECD is likely to further increase.

Figure 1.1. Trends in share of deaths by age group in OECD countries, 2001, 2009 and 2019

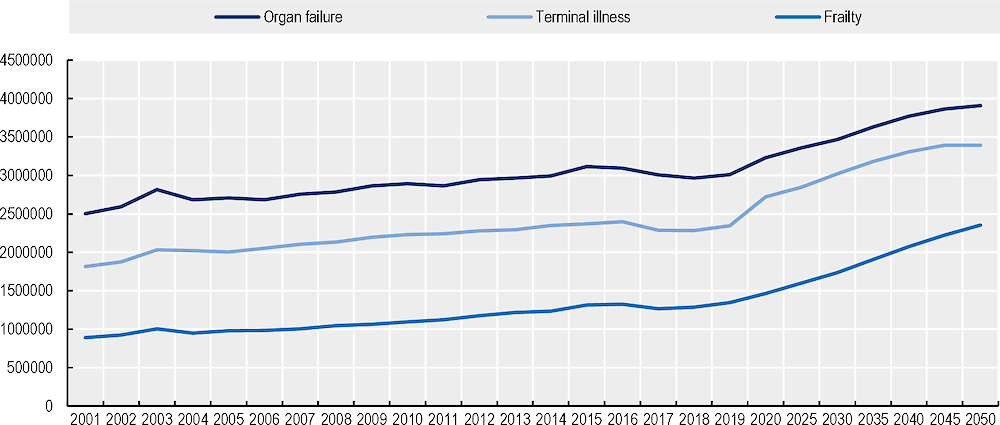

Figure 1.2 shows the estimated projection for the number of deaths that are likely to require palliative and EOLC for each of the EOL trajectories (organ failure, frailty, and terminal illness) up to 2050. According to these projections, the total number of deaths from diseases that would benefit from palliative and EOLC is forecast to move from 7 million in 2019 to close to 10 million in 2050. Annex 1.A provides data and methodological description of the projections. With such a high number of people affected by diseases that require EOLC, and an expected increase in the demand for these services in the coming years, EOLC is becoming a global public health priority.

Figure 1.2. Deaths from organ failure, terminal illness and frailty will increase until 2050

Note: The data include 33 OECD countries. Greece, Ireland and Türkiye are excluded for insufficient data.

Source: WHO mortality database (WHO, 2022[10]), UN database for mortality projections (United Nations, 2019[11]), (Qureshi et al., 2018[12]) for the definition of the EOLC death trajectories and (Etkind et al., 2017[13]) for the percentages of pain prevalence.

Box 1.1.What is end-of-life care?

There is no universally shared EOLC definition and a degree of heterogeneity exists on the timeframe to provide EOLC services. This report takes a broad interpretation and conceptualises EOLC as the care provided to people who are in the last 12 months of life. This includes patients whose death is imminent (expected within a few hours or days) and those with: a) advanced, progressive, incurable conditions; b) general frailty and co‑existing conditions that mean they are expected to die within 12 months; c) existing conditions if they are at risk of dying from a sudden acute crisis in their condition; or d) life‑threatening acute conditions caused by sudden catastrophic events (Leadership Alliance for the Care of the Dying People, 2014[14]).

In addition to the time frame, the definition of EOLC concerns the services and support provided. The EOLC concept utilised in this report refers to the terminal stage of palliative care, provided in the very last period of a patient’s life, as well as including some elements of curative care and help with mobility limitations. In essence, it means that the focus is on palliative care which entails physical, emotional, social, and spiritual support with a particular emphasis on symptoms management such as pain but also emotional support and mental health care and bereavement care for families.

With respect to curative care, the report provides evidence of avoidable hospitalisations, emergency care and the care provided in intensive care units (ICU), among others (Wentlandt and Zimmermann, 2012[15]). In relation to life‑sustaining care for individuals with life‑threatening diseases and at the last stage of life, it is often profoundly difficult to make treatment decisions as survival probabilities are difficult to estimate. At the same time, life‑prolonging measures are sometimes continued near the end of life, rather than focusing on improving quality of life due to a lack of other services. Decisions on commencing, as well as withholding and withdrawing treatments, are addressed in different ways across countries because of variation in legal frameworks and practices, as well as funding for certain treatments. This report’s definition of end-of-life care does not include euthanasia, but a table in the Annex summarises which countries do include euthanasia within end-of-life care policy.

A framework for assessing end-of-life care

The OECD drew on national action plans and strategies for palliative and end-of-life care to identify key principles for evaluating the performance of end-of-life care in countries, identifying best practices and evidence‑based strategies. In 2020, an expert workshop convened to discuss such framework, its key principles, and the best ways to measure them. In the future, countries wishing to improve end-of-life care should pay more attention to the five priorities which can help improve end-of-life care performance. Such priorities are outlined in the OECD’s framework illustrated below so that end-of-life care becomes:

1. Accessible, that is, individuals have access to well-staffed, well-distributed, equitable, and timely end-of-life care.

2. People‑centred, that is, individuals, their relatives and informal carers are informed, collaborate in key decisions, and receive inclusive care.

3. High quality, that is, individuals receive appropriate, comprehensive, and accountable care that provides comfort.

4. Appropriately financed, so that individuals and their families can afford care that is adequate, effective and whose burden is fairly shared.

5. Well-governed and evidence‑based, that is, individuals receive care that is integrated and adaptable. They benefit from research-based and data-driven decision making in the end-of-life care planning and provision.

Table 1.1. Key principles of the OECD’s framework for end-of-life care

|

Accessible |

People‑centred |

High-quality |

Appropriately financed |

Well-governed and evidence‑based |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Individuals and their support networks have access to well-staffed, well-distributed, equitable and timely end-of-life care |

Individuals and their support networks are empowered to take a central role in assessing and articulating their needs, and can access inclusive care that meets those needs |

Individuals receive appropriate, comprehensive, and accountable care that maximises their quality of life |

Individuals and their support networks can access sustainable, affordable, and effective care that does not place an undue burden on their support networks |

Individuals receive care that is integrated within the national social security system and is adaptable in case of emergencies. They benefit from evidence‑based decision making in the end-of-life care planning and provision. |

|

Well-staffed: People have access to sufficient staff having adequate competences in palliative care and end-of-life care |

Informed: People, relatives and informal carers are empowered to make informed decisions about their care through the provision of information on the services and support available to them |

Appropriate: People receive adequate symptom control and care that is in line with their preferences and appropriate to their circumstances. |

Adequate: Health and social services required to provide end-of-life care are sufficiently and sustainably financed. |

Adaptable: Health systems can continue to provide high-quality end-of-life care during unexpected shocks and end-of-life care |

|

Well-distributed: People can have access to services in their choice of setting, especially in the community |

Collaborative: People, relatives and informal carers have timely and focused conversations with professionals to collaboratively plan their end-of-life care and support. |

Comprehensive: Care is delivered through workers that work together in an interdisciplinary way, considering the psychosocial and spiritual needs of the person and their family. |

Fairly shared: Care provided in the home places minimal burden on relatives and informal carers. |

Integrated: Care is fully integrated into the wider health system and across all care settings. |

|

Equitable: People receive effective care irrespective of their socio‑economic background. |

Inclusive: People, relatives and informal carers take a central role in determining their care according to their needs, values, and preferences. Care is provided in a considered and culturally appropriate manner |

Accountable: Clear standards exist, and services are monitored, inspected, and regulated to ensure they meet these specifications. |

Effective: End-of-life care services prioritise cost-effective interventions and delivery models that improve care quality |

Data-driven: Governments implement a strategy for end-of-life care data with a minimum dataset. |

|

Timely: People receive effective care when they need it. |

Research-based: Governments and other stakeholders support end-of-life care research. |

1.1. Removing barriers to access EOLC remains a priority

1.1.1. Access to end-of-life care is insufficient due mainly to staffing shortages

Palliative care services are not yet available to all patients with serious chronic illness, and challenges in accessing end-of-life care are prominent across all OECD countries. Across OECD countries for which data was available, less than 40% of those dying in need of palliative care services receive such services. Within European countries, Austria, Estonia, Greece, Hungary, and Latvia report a lack of timely access to palliative care services for people in need (Palm et al., 2021[16]).

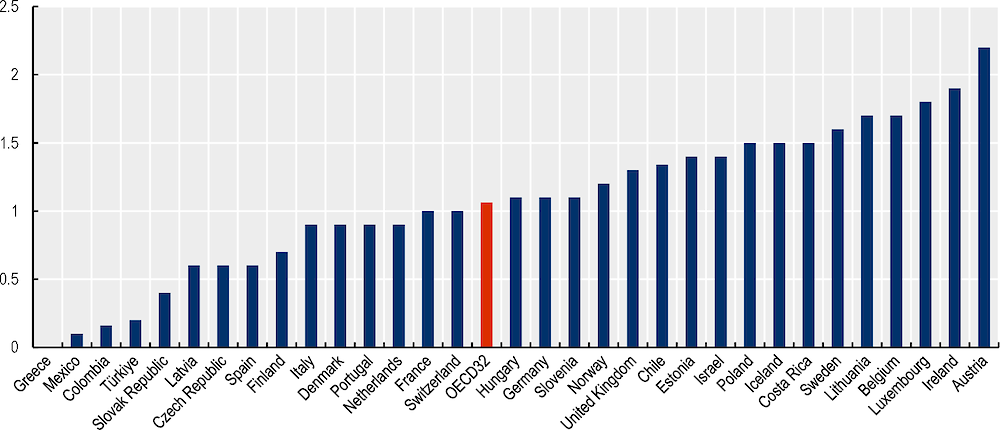

There is a lack of palliative care specialists across countries. To address a patient’s more complex needs, a multidisciplinary specialist team with extensive training in palliative care is typically suited. The European Association for Palliative Care recommends two specialised palliative care services team per 100 000 inhabitants (Centeno et al., 2016[17]) while the OECD average was 1.1 in 2017. In Europe, countries like Austria and Ireland appear to be better equipped in terms of the availability of palliative care teams, having close to two specialised palliative care teams per 100 000 population in 2017 (Figure 1.3). In Latin America, Chile and Costa Rica stand above the OECD32 average. On the other hand, Greece, Colombia and Türkiye show the lowest numbers.

Figure 1.3. Palliative care specialised teams in OECD countries with available data, 2017

Source: (Arias-Casais et al., 2019[18]) for Europe and (International Association for Hospice and Palliative Care, 2020[19]) for Latin American countries.

To ensure adequate access to end-of-life services, countries would need to make further efforts to train and recruit staff. While specialisations on palliative care for physicians are available in most OECD countries (75%), around one‑third of countries still report that undergraduate medical school curricula do not include mandatory training on palliative care. Furthermore, while palliative care is increasingly included into medical and nursing school’s curricula, there is high variability over the way countries embed it into the curricula. Palliative care is not always mandatory, and it is rarely mandatory per se, but often combined with other subjects (Arias-Casais et al., 2019[18]). France has set the objective to make palliative care training available in all health sector degrees and Australia also has several national and local initiatives to expand training on end-of-life care (Department of Health - Victoria, 2022[20]; French Ministry of Health, 2022[21]).Forecasting current and future care needs and enhanced workforce planning would provide a better idea of staffing needs and gaps. The United States, for example, has forecasted that given future needs, the number of physicians entering a palliative medicine fellowship training would need to increase from 325 to 500‑600 per year by 2030 (Lupu et al., 2018[22]).

It is also important to provide adequate on-the‑job training on end-of-life care to regularly develop and improve the skills of professionals in this area. Most countries (83%) already report on-the‑job training. However, in only 29% of countries it is mandatory for staff working in the field of end-of-life care. Some efforts are already in place across OECD countries to improve the availability of continuous training for the health care workforce. To ensure quality training, France is planning to develop on-the‑job training and to evaluate its quality through the monitoring of indicators and surveys of satisfaction (French Ministry of Health, 2022[21]), while England (United Kingdom) is improving the quality of end-of-life care training thanks to the use of technology, offering remote training sessions that reduce travel time and increase access to training (King's Fund, 2011[23]). Sweden also provides a guide and free online training on palliative care for all health care staff and other interested stakeholders. The United States have training centres to support the organisation and provision of on-the‑job training (CAPC, 2022[24]; Skillsforcare, 2022[25]).

Besides training more, retention strategies are also critically necessary to ensure that palliative care health professionals do not leave the sector due to burnout, insufficient compensation, or poor leadership. In Canada, 38.2% of palliative care physicians reported a high degree of burnout and workplace interventions to reduce stress can prove useful (Wang et al., 2020[26]).

1.1.2. Significant inequalities remain across socio‑economic groups at the end of life

Socio‑economic background has been found to influence the way people experience the end of their life. In fact, while people with lower socio‑economic background might be more in need of end-of-life care, due to higher prevalence of disease, disability and health risk factors, evidence from the United States, Canada and the United Kingdom shows that they are less likely to use palliative care, more likely to use acute hospital care and more likely to die at the hospital (Davies et al., 2021[27]; Simon et al., 2016[28]; Walsh and Laudicella, 2017[29]). OECD analysis of survey data confirms that people with higher education levels and in urban areas are also more likely to receive end-of-life care in many European countries, Korea, and the Unites States.

The reasons behind such outcomes are not yet well understood but evidence points to people from lower socio‑economic background facing barriers to access end-of-life care. Geographical accessibility might differ because service availability favours more advantaged areas (French, Keegan and Anestis, 2021[30]). Other reasons might be related to health literacy, knowledge about services and higher communication difficulties with health care providers about choices and preferences.

Some countries have placed special emphasis on reducing inequalities in access to end-of-life care. Currently, while more than 50% of the 24 OECD countries surveyed have policies to ensure equity in the access to EOLC, such policies are often quite general and do not define concrete measures to ensure equitable access to care. In Canada, on the other hand, the federal government has recently sought to address geographical disparities through higher funding. The federal government plans to invest CAN 26 million to incentivise professionals to work in rural areas, which are often underserved. The investment aims at forgiving student loans for physicians and nurses who practice in rural and remote areas (Department of Finance Canada, 2022[31]). In England (United Kingdom), people from a lower socio‑economic background can obtain access to an adequate care package within 48 hours from referral thanks to a Fast-Track Funding (NHS, 2021[32]). Only half of the surveyed countries exempt people with low income from co-payments while Austria, Denmark, Germany, Luxembourg, Norway, and Sweden set a ceiling for co-payments (OECD, 2019[33]). Involving people with diverse socio‑economic backgrounds in research and policy making could help tailor policies on people’s needs (Rowley et al., 2021[34]).

1.1.3. People prefer to receive end-of-life care at home, yet 50% die in hospitals

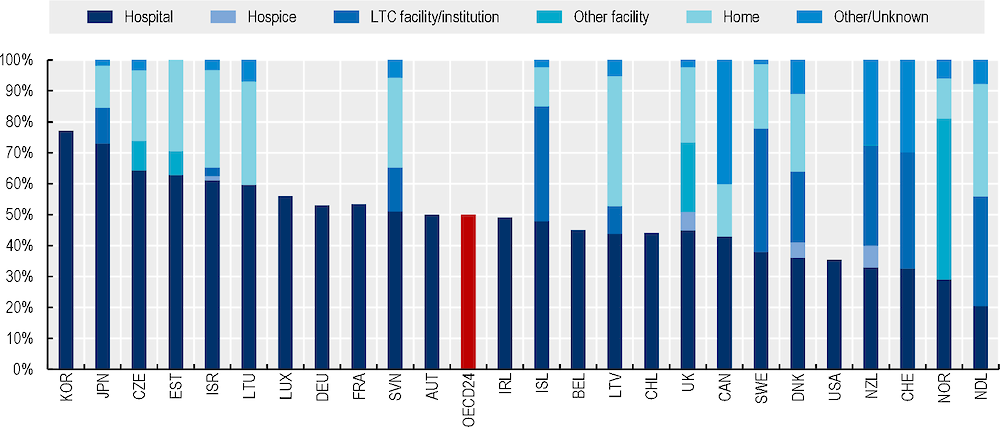

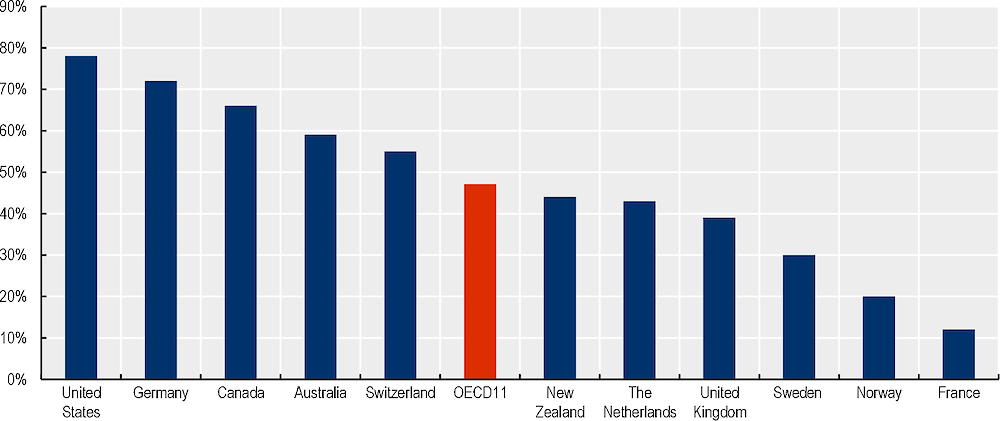

End-of-life care can be provided in a variety of settings, including hospitals, in people’s home, in a nursing home or in a hospice. One challenge is that the place of end of life is often poorly aligned with people’s preferences, often because of lack of services. While most people prefer to die at home,1 this rarely occurs, and when it happens it might not necessarily be a good death, because of lack of adequate services. In some cases, people at home are not able to receive end-of-life care services appropriate to their needs. While in Australia, Canada, New Zealand and Iceland, deaths in institutional care are common, representing more than one‑third of deaths, across OECD countries, hospitals are still the predominant place of death, accounting for more than 40% of deaths and up to 77% in some countries. (Broad et al., 2013[35]). Figure 1.4 shows the percentage of people dying in hospital or in other settings in 2019 or the latest year available for 24 OECD countries. Japan, Korea, and the Czech Republic appear among the countries with highest share of people dying at the hospital, as opposed to The Netherlands, Norway, Switzerland, and New Zealand, where hospital deaths are rarer.

Figure 1.4. Half of the deaths across OECD countries happen at the hospital

Further efforts are needed to expand access to end-of-life care at home and in non-hospital settings, such as long-term care institutions. Non-specialised care providers are often ill equipped to provide quality end-of-life care. Evidence showed that general practitioners who received training on identifying and planning palliative care are more likely to recognise people who need such services and to provide holistic palliative care (Lam et al., 2018[37]; Thoonsen et al., 2019[38]). In many countries, staff in long-term care facilities do not reach the 40% threshold in terms of staff´s palliative care training and more efforts are needed to prevent that older people are transferred to hospitals from nursing homes at the time of death (Arias-Casais et al., 2019[18]).

Training in end-of-life care should target better primary care professionals and long-term care staff, while finding innovative ways to co‑ordinate with specialist support. Several countries are already transforming the provision of end-of-life care towards a model of palliative care where hospital, community, primary care, and specialist palliative care work together to provide integrated care. Canada, Ireland and New Zealand, for example, have increased the number of health care professionals with end-of-life care knowledge in a variety of settings (CIHI, 2018[39]; HSE, 2019[40]; Koper, Pasman and Onwuteaka-Philipsen, 2018[41]). In Australia, there is positive evidence of nurse‑practitioner-led models in palliative care in rural areas. New Zealand decided to create regional managed clinical networks (MCNs) to link primary care professionals to specialists in case of need. Ireland is working on a model of palliative care where hospital, community, primary care, and specialist palliative care providers are supported to work together to provide an integrated care (HSE, 2019[40]). Australia and Germany have also made use of technology and training for generalists to ensure out-of-hours care at home (Health Research Board, 2019[42]; Victoria State Government, 2012[43]). In England, an innovative model of training was piloted and rolled out across nursing homes using a team from hospital including a palliative care consultant, a palliative care nurse consultant, a palliative care matron and three clinical nurse specialists to train and support nursing home staff (EJPC, 2020[44]).

1.1.4. Too often, people are unable to access appropriate end-of-life care when they need it

End-of-life care needs are often recognised late, delaying referral. Even when referral is obtained, the time span between referral and access to services can be lengthy, leading people to access the services they need only at the very end of life, in the last month before death. Countries are putting in place measures to prevent late identification of needs, but further efforts are still required to ensure that people have access to timely end-of-life care.

Ensuring timely access to adequate care is particularly crucial for people at the end of life but recognising when someone is reaching their end of life might be challenging, causing delays in diagnoses. Further delays take place between referral and actual access to end-of-life care services. Estimates from the United Kingdom report that 40% of referrals happen in the last 30 days of life (NIHR Dissemination Centre, 2018[45]). OECD analysis has also highlighted that more than half of the people receiving palliative care services only receive them in the last month of life. Supply constraints (e.g. insufficient specialists) and stigma from the patient side also represent barriers to timely access to EOLC.

OECD countries rarely monitor whether EOLC is provided in a timely manner and policies to ensure timely access are rare. Only Ireland, Italy and Norway provide national indication on the preferable timing for access to EOLC and only 7 countries have policies in place to monitor whether access to EOLC is timely.

Policies are in place in some countries to allow for early identification of needs and access to EOLC services, but they need to expand to achieve truly timely EOLC for all. Canada and Italy have programmes that have proven successful in providing people with the most appropriate care. Canada developed an Early Identification and Prognostic Indicator Guide to support providers, while Italy implemented a model of early identification of patients with palliative care needs through integration between primary care and home palliative care (Arianna Working Group, 2018[46]; CIHI, 2018[39]). The United Kingdom has monitored regional key performance indicators (KPIs) on timely access to EOLC services.

When the need of end-of-life care is recognised, referral should be fast to ensure that people who need care can receive it as soon as possible. Across OECD countries, EOLC services can be accessed mostly through referral from a GP or specialist (92%) or emergency department (69%). Virtual referral through digital health services is available in 31% of countries. Several examples of policies to improve referrals are available across the OECD. Maximum waiting times, regular evaluation, and assessment of waiting times and the introduction of fast-track pathways for people at the end of life are all in place in some OECD countries such as Ireland, the United Kingdom, and the United States (NHS, 2021[32]). Other measures that countries could develop include the early integration of end-of-life care in the care of people with life threatening and life‑limiting conditions, by improving the links between different settings of care and types of care provided. Such policies have proven successful in improving the quality of people’s life (Kaasa and Loge, 2018[47]; Vanbutsele et al., 2018[48]).

1.2. Towards more people‑centred end-of-life care

1.2.1. Improving communication around preferences for end-of-life care helps people make informed decisions about the end of their lives

A truly people‑centred end-of-life care entails that people at the end of life and their relatives participate in the care choices at the end of life. Having conversations around care preferences and formal expressions of their wishes for end-of-life care is useful to make sure that people’s wishes are respected when they approach death. This is particularly important for people who are affected by dementia or other cognitive diseases, who might not be able to express their wishes in their last period of life.

Only one in two people have conversations around end-of-life care preferences in surveyed countries. Despite the importance of having conversations on end-of-life care preferences, this is seldom discussed preferences as reported in Figure 1.5, although there is high cross-country variability.

Figure 1.5. On average, less than half of older people had conversations on their care preferences

Note: Data refers to people aged 65+ who had discussion with someone including family, a close friend, or a health care professional.

Source: (Commonwealth Fund, 2017[49]).

Barriers to conversation on end of life include difficulties to find the right moment to start conversations on the clinician’s side and poor understanding of end-of-life care on the patients’ side (Bamford et al., 2018[50]; Swerissen, 2014[51]). Health care professionals also often report insufficient knowledge of the instruments available to register patients’ care preference. Within LTC facilities, the lack of adequate space and low staff ratios further reduce the opportunities to engage in end-of-life care conversations (Harasym et al., 2020[52]).

Most OECD countries (77%) have some form of regulation that requires people at the end of life to designate an attorney for decision-making, namely choosing a relative who will make decisions on their end of life should they become unable to express their wishes. Nevertheless, the use of such instruments for decision making at the end of life is still limited and hampered by the biases mentioned above, and even where such tools are in place, they are not always followed.

Providing clinicians with training around end-of-life care and specifically on conversation and decision making at the end of life would reduce the communication barriers arising from stigma and disinformation. Results from Japan show that clinicians who received training on EOLC are more likely to have conversations and involve people at the end of life in the decisions regarding their end-of-life care (Tamiya, 2018[53]). Canada, Japan, and the United States are examples of countries already providing specific training on conversations at the end of life. In some cases, such training also includes specific guidance on EOLC conversations with people from diverse ethnic and cultural backgrounds (NHCPO, 2021[54]).

Enhancing multidisciplinary conversations would also improve the end-of-life experience. Clinicians who are informed about their patients’ history and their previous contacts with other professionals would be better able to reduce discontinuity of care and repetition of information during the conversations with their patients, which usually cause stress, higher costs of care and more aggressive care (Hafid et al., 2022[55]; Sharma et al., 2009[56]).

Finally, to ensure that EOLC conversations contribute to better quality of life for people at the end of life, countries could include questions regarding conversations within Patient Reported Experience Surveys (PREMS). According to OECD surveys, 7 out of 12 surveyed OECD countries currently include questions on EOLC discussion within PREMs. The measurement of communication’s quality at the end of life prioritised to assess how people centred EOLC is.

1.2.2. End-of-life care services should become more inclusive

Less than half of the surveyed countries require consideration of cultural preferences when providing end-of-life care. Ethnic and cultural minorities represent a growing share of the population in a number of OECD countries, but they tend to receive fewer end-of-life care services and more aggressive care, compared to the general population (Ejem et al., 2019[57]). Language and communication difficulties, personal beliefs and cultural factors, mistrust towards the health care sector and bias and discrimination are all barriers to people‑centred end-of-life care for ethnic and cultural minorities (Crist et al., 2018[58]; Isaacson and Lynch, 2017[59]).

The knowledge of health care professionals around such cultural and ethnic differences is still limited. Only 10 out of 24 OECD countries have developed some form of regulation to take cultural aspects into account in the decision-making process around the end of life. Translation of relevant information into other language and training among the health care professionals could ease communication and improve access to adequate care at the end of life for all people, regardless their ethnic and cultural background.

Inequalities in the way people experience their end of life also exist across gender, age groups, and diseases. OECD analysis shows that males and younger people receive more aggressive care at the end of life, with higher rates of hospitalisations in the last year of life in all seven surveyed countries and across all disease types. Younger people with cancer are more likely to receive chemotherapy in the last 30 days of life compared to older adults, in Denmark, Israel and Sweden and youth who wish to receive palliative care are less likely to access such services compared to older people with similar wishes (Parr et al., 2010[60]). On the other hand, patients with cancer are far more likely to receive palliative care services compared to patients affected by other diseases.

Social biases and stereotypes are among the drivers of such differences and mismatch between people’s preferences and care received. Requesting palliative care might be perceived as a sign of weakness and of “giving up the fight against the disease” and might be less acceptable for some groups. Furthermore, the death of a younger person might be considered less acceptable than that of an older person for some (Parr et al., 2010[60]). Health care workers should be made aware of such social biases and stereotypes, and they should be supported in fighting such biases, to ensure that everyone can receive the most appropriate end-of-life care services, regardless of their gender, age, and disease.

1.2.3. Improving awareness of end-of-life care is an important step to promote knowledge of services

Stigma and taboo related to death affect the general population, reducing knowledge around end-of-life care services and the capacity of patients to request specific services. Insufficient information around EOLC makes it challenging to provide truly people‑centred care, which entails the involvement of people in the decisions regarding their end of life. Campaigns to improve knowledge around end-of-life care and the role of other actors including patient and professional associations and groups of neighbours constituting compassionate communities (who provide support to patients and carers) can help making end-of-life care more centred on the person.

Evidence from most OECD countries shows that most adults in the general population have no or very limited knowledge around what services are available for people reaching the end of their life. Between 40% and 80% of adults across OECD countries are not able to provide a definition of end-of-life care or do not know what services are available to people reaching the end of their life. Even more noteworthy, significant shares of health care professionals (e.g. 17% of health professionals in Lithuania, 60% of nursing home and care home staff in the Netherlands) lack good knowledge around available tools to plan care in advance (Evenblij et al., 2019[61]; Peicius, 2017[62]).

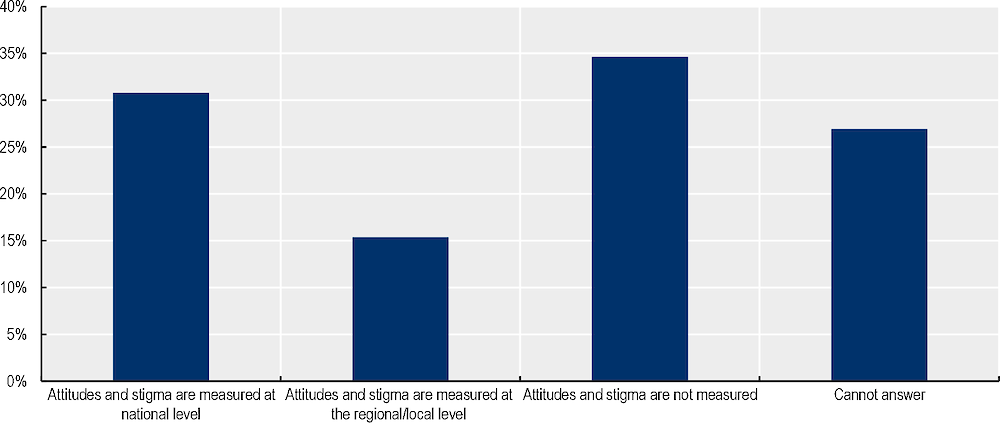

Taboos around death, lack of conversations between health care professionals, patients and their close ones, and lack of funding are all recognised barriers to a wider spread of knowledge on end-of-life care. Despite this being a well-known issue, attitudes, and stigma around death and EOLC are not widely measures across OECD countries, with only 8 out of 26 OECD countries measuring them at the national level (Figure 1.6).

Figure 1.6. A third of the OECD countries surveyed do not measure stigma around EOLC

Note: N=26; Countries’ answer to the question “Do you have any way of measuring attitudes or levels of stigma around EOLC or discussion on death?”

Source: (OECD, 2020-2021[63]).

Strengthening campaigns about end-of-life care would raise awareness and improve acceptance of EOLC services. Evidence suggests that being informed about end-of-life care also increases the likelihood of being willing to request and receive such services (Kleiner et al., 2019[64]; Lane, Ramadurai and Simonetti, 2019[65]). Better knowledge of EOLC among both the general population and health care professionals would also facilitate open conversations on the health status and care preferences for people at the end of life, allowing tailoring of care decisions on the person’s preferences. Some countries have established programmes and campaigns to improve knowledge around palliative (83%) and end of life (72%) care, while more detailed campaigns on specific end-of-life care services are still rare. Awareness raising campaigns have proven effective. In France, for example, 84% of adults interviewed reported that information diffused through websites and social media was useful to learn about end-of-life care (Fin de vie soins palliatifs - centre national, 2019[66]).

A vital community can help improve the knowledge around end-of-life care, fight stigma and stereotypes and putting end-of-life care under the spotlight in policy making. Compassionate communities are building up across OECD countries. Made up of groups of people within the community providing support to people in need, also provide a measure of how much people are involved and engaged in end-of-life care decision making and services provision, their goal is to support people with limiting conditions and those who are at the end of life, as well as their loved ones, and they can foster their voices. Examples of compassionate communities exist in Belgium, Canada, Costa Rica, Germany, New Zealand, Spain, United Kingdom, and the United States (Compassionate Communities UK, 2022[67]; NHS UK, 2021[68]; Pallium Canada, 2022[69]).While compassionate communities often start as a local initiative, non-governmental organisations are playing an important role to foster the development of communities across the whole country.

Associations on end-of-life care can help spread EOLC knowledge across professionals and also bring the topic to the attention of policy makers. Most European countries have at least one national association on palliative care as of 2019 and in Latin America, Chile, Colombia, and Costa Rica have more than one, while Mexico has none (Arias-Casais et al., 2019[18]). The number of associations and lobbying groups devoted to end-of-life care also varies widely across countries, with Ireland and Canada showing the highest numbers across OECD countries whose data is available. Furthermore, Among OECD countries with data available, Luxembourg, Slovenia and Australia reported the highest numbers of national professional associations on EOLC.

1.3. Renewing focus on care quality

1.3.1. The end-of-life treatment that people receive is not always appropriate to their circumstances

When people are reaching the end of life, they risk experiencing suffering due to under-treatment of their symptoms. On the other end, some people are provided treatment that is not likely to provide any further curative benefit, resulting in overtreatment and aggressive care until the very end of life, which delays the use of palliative care. This is both inefficient and reduces the quality of life of people at the end of their lives.

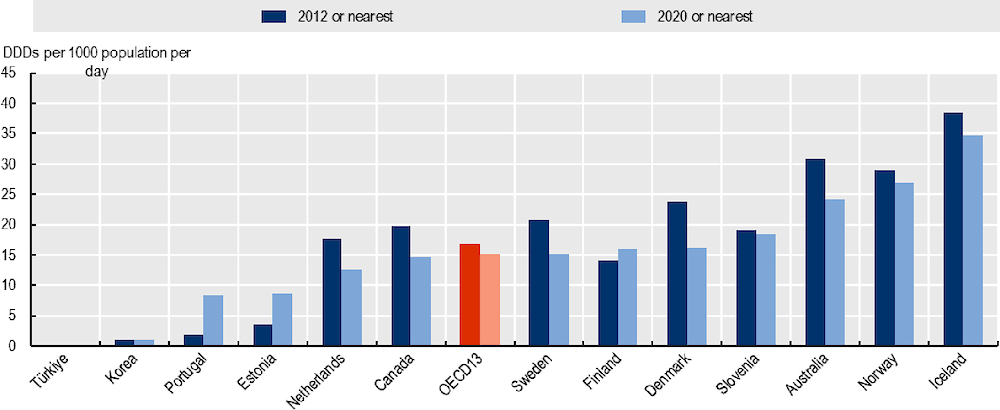

The treatment of physical symptoms requires the use of pain-relieving medications, including opioids. Following concerns raised by the abuse and misuse of opioids in some OECD countries, the prescription of such medication fell between 2012 and 2020, although opioid overuse is still an issue in some countries (Figure 1.7). In Canada, the share of population using opioids fell between 2015 and 2017, but emergency department visits due to opioid poisoning and opioid-related deaths still increased in the same period in the provinces of Alberta, Yukon, and Ontario (CCSA, 2020[70]). In the United States, the national opioids dispensing rates decreased between 2012 and 2020, but some areas of the country still show particularly high rates (US CDC, 2021[71]). At the same time, pain relieving medications remain highly unequally distributed across countries, leaving some people’s symptoms untreated, with older people appear to receive lower treatment for their physical symptoms compared to younger people (Dalacorte RR, 2011[72]; Fineberg IC, 2006[73]).

Figure 1.7. Opioid consumption has declined in most countries in the last decade

Reducing barriers to pain relief is of paramount importance to ensure that everyone experiences a good quality of life until the very end. Addressing this requires:

Tackling barriers to pain relief medication include changing regulation. For example, in Canada, palliative drug programs have been put in place in several territories and provinces. In Australia, the position statement of Palliative Care Australia on Sustainable Access to Prescription Opioids for Use in Palliative Care also provides recommendations for a sustainable opioid management, to improve the access to such medications while minimising the risks linked to their use (Canadian Institute for Health Information, 2018[75]; PCA, 2019[76]; TGA, 2018[77]).

Raising knowledge and skills among health care professionals, who report they lack adequate knowledge to safely prescribe opioids (Bhadelia et al., 2019[78]). Training has been shown to improve professionals’ confidence to prescribe opioids and allowing some well-trained non-physicians to prescribe opioids increases the access to pain-relief. Evidence from the Netherlands and the United Kingdom showed that training is an effective way to support physicians to prescribe opioids appropriately (British Medical Association, 2017[79]).

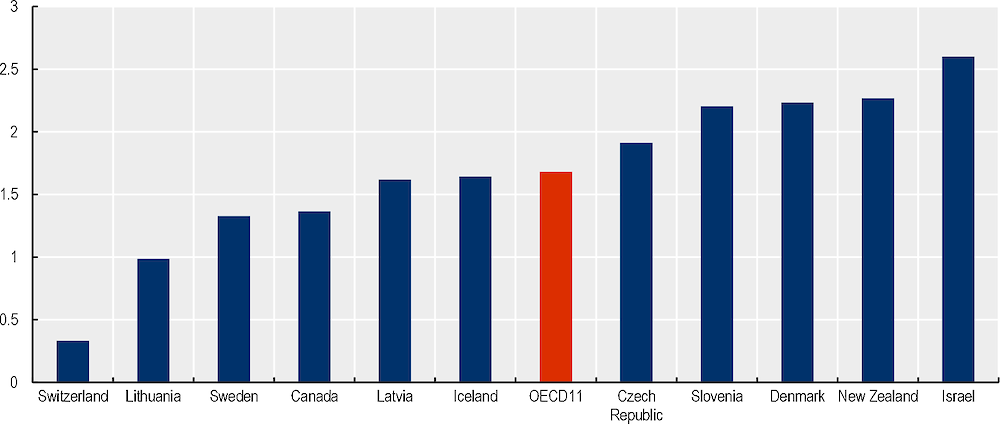

People at the end of life also experience overtreatment, with more than one‑third of older people hospitalised near the end of life receiving interventions unlikely to provide either survival or palliation benefit (Cardona-Morrel et al., 2016[80]). Figure 1.8 shows that hospitalisations in the last year of life are common in OECD countries and further OECD analysis has shown that people tend to be hospitalised more than once in the last year of life. Admissions to Intensive Care Units and visits to Emergency Departments are also common in the last 30 days of a person’s life, particularly among younger people.

Figure 1.8. People are admitted to hospital on average 1.68 times in the last year of life

Evidence on measures to reduce unnecessary treatment at the end of life is still emerging, but studies have shown that community-based palliative care is associated with less unnecessary hospital use at the end of life (Canadian Institute for Health Information, 2018[75]). Doctors who received training on end-of-life care are also less likely to choose aggressive care at the end of life, but family members can sometimes influence the professionals’ choices, especially in the absence of written documents reporting the patients’ wishes (e.g. living wills, do not attempt resuscitation, advance directives) (Piili et al., 2018[81]).

In some cases, wishes for continuing curative care and overtreatment come from family members of the patient. Disagreements can arise between professionals and family members which complicates decision-making on end-of-life care. Studies have shown that the use of ethics consultations is associated with lower use of aggressive care and shorter stays in intensive care units (Au et al., 2018[82]; Schneiderman, Gilmer and Teetzel, 2000[83]) Three‑fifths of OECD countries have national guidelines to manage these situations of misalignment and around one‑third have interdisciplinary ethics committees or employees assistants in most or all facilities to support health care professionals in complex decision-making (OECD, 2020-2021[63]).

1.3.2. There are considerable gaps still in measuring and monitoring the quality of end-of-life care

Good quality end-of-life care would require clear quality standards, clinical care guidelines and quality measures that can be regularly collected. In nearly two‑thirds of OECD countries there are quality standards for EOLC services at the national level. Such standards typically focus on early identification of people who are reaching the end of their life, shared decision-making with patients and their relatives, symptoms and pain control, holistic care that includes support to patient’s relatives, advance care planning, multidisciplinary and co‑ordinated care provision. For instance in Australia the Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care published standards that focus on two areas: i) process of care (i.e. patient-centred communication, share decision-making, care co‑ordination, recognition of patients reaching the end of life) and ii) organisational prerequisites (governance, education and training, support to multidisciplinary teams, monitoring and evaluation) (Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care, 2015[84]). In the United Kingdom, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence provides comprehensive quality standards for end-of-life care for adults, identifying 12 recommendations for high-quality end-of-life care2 (NICE, 2021[85]). Quality domains include identification of those approaching the end of life having advance care planning, receiving co‑ordinated care and having access to 24‑hour care support. Some countries, such as Germany and Ireland, also have quality standards for specific care settings. In Ireland, for example, the Hospice Foundation provides specific standards for end-of-life care in hospitals (Hospice Foundation, 2013[86]).

However, quality standards are not always mandatory or regularly monitored. Countries differ in the availability of audit and quality evaluation programmes and in their characteristics (e.g. whether they entail internal or external assurance and inspection). Three‑fifths of OECD countries have audit or quality evaluations for end-of-life care, but they do not always cover all settings of care. In the United Kingdom, the National Audit of Care at the End of Life (NACEL) evaluates how hospitals perform vis-à-vis existing quality standards (NHS, 2022[87]). Similarly, the United States has a Hospice Quality Reporting Program for all Medicare‑certified hospice programs that has quality reporting requirements for hospice providers and public reporting of quality measures (Centers for Medicare and Medicaid, 2021[88]).

Clinical care guidelines specific to EOLC provide clear guidance on the best care for people at the end of life and can represent a mechanism to avoid over- and under-treatment at the end of life. Across OECD countries, Norway, Denmark, and England have EOLC guidelines for several settings of care, while in other countries, EOLC guidance is included within clinical care guidelines for specific conditions (e.g. cancer). This can be a challenge if much end-of-life care was developed to care for people dying of cancer, but is not always fit for purpose for other conditions. Some countries such as Denmark and the Netherlands use other levers to drive service improvement in EOLC, including clinical quality programmes and payment systems that can drive care quality (Danish Ministry of Health, 2018[89]; Palliaweb, 2019[90]).

There is often a lack of nationally used sets of measures with benchmarking that applies across populations and settings. Quality indicators based on administrative and clinical data are also not widely in place. The most available outcome indicator is place of death, which is available in at least 14 OECD countries, followed by hospital admissions in the last year of life (in 12 countries), hospital 30‑day readmission (9 countries) and visits to the emergency department in last 30 days of life (7 countries). Other indicators of poor quality, such as use of chemotherapy in the last days of life, as well as positive quality indicators such as the number of people using palliative care, recording advanced directives, or being referred to palliative care appear to be less widespread. Few indicators dealt with the organisational structure of palliative care. Moreover, not all domains of palliative care were covered to the same degree, with a notable underrepresentation of psychosocial, spiritual, and cultural domains. Finally, most indicators were restricted to one setting or patient group, often cancer patients (Daryl Bainbridge and Hsien Seow, 2016[91]).

Nearly half of the responding OECD countries (12 out of 25) held no system in place to monitor and evaluate palliative care experiences and outcomes such as patient reported outcomes and measures. In Australia and New Zealand, the Palliative Care Outcomes Collaboration collects patients’ outcomes to measure quality of end-of-life care. The indicators measure responsiveness to urgent needs, pain management and timely commencement of palliative care, among other things (PCOC, 2022[92]). Other examples of national quality measures for end-of-life care are the measures in the Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (CAHPS) Hospice Survey, Hospice Item Set (HIS) and the Bereaved Family Survey (bereaved family survey BFS) in the United States. Internationally comparable quality indicators are still rare, making cross-country benchmarking difficult, though some efforts are in place to improve international comparability. The Palliative Care Outcome Scale, the McGill Quality of Life Questionnaire (MQOL) and the Cambridge Palliative Assessment Schedule (CAMPAS-R) are examples of questionnaires collecting Patient Reported Outcome Measures (PROMs) and Patient Reported Experience Measures (PREMs) on end-of-life care that aim to make such information internationally available and comparable.

1.3.3. Holistic care that addresses all the person’s needs improves the quality of life for people at the end of life and their relatives

People at the end of their life have inter-related needs which are often not addressed sufficiently. When people reach the end of their life, they often face several physical, psychosocial, and spiritual needs, which require a holistic approach to be adequately addressed and managed. Psychosocial and spiritual support is key to ensure good quality of life until death for the dying person, as well as easing the grieving phase for the relatives. For instance, symptoms of depression increase in the last year of life and 60% of people have depression in the last month before death (Kozlov et al., 2019[93]). Nevertheless, surveys often report that both psychological and spiritual support at the end of life is inadequate, showing wide room for improvement (Evangelista et al., 2016[94]; McInnerney et al., 2021[95]; Thomas, 2021[96]).

Addressing all symptoms holistically entails that different professionals collaborate to take care of the person and their relatives at the end of life. Many countries are developing the use of multidisciplinary teams. England (United Kingdom) and France recommend the use of multidisciplinary teams within guidelines on end-of-life care. Canada makes regular use of multidisciplinary teams to provide end-of-life care, while Czech Republic started a pilot project in 2017 to implement multidisciplinary palliative care teams across the country. Ireland, Japan, and the United States have set up multidisciplinary training where professionals can learn together and exchange knowledge and experience. Despite the existence of multidisciplinary teams, the professionals included in such teams vary across countries, with psychologists and psychotherapists only included in 14 and 7 countries, respectively, across 27 OECD countries.

In addition, the death of a person is a mentally distressing moment for the relatives and carers. Patients’ families also report declining mental health near the death of their loved ones. Between 7% and 39% of cancer patients’ families experience grief disorders (Kustanti et al., 2021[97]). Follow-ups after death to help support relatives in the grieving and bereavement process and already exist in some countries, such as the Bereavement Support Line set up in Ireland.

1.4. Ensuring affordable end-of-life services

Public funding for EOLC is geared towards hospital settings and the lack of integrated funding streams reduce opportunities for early palliative care which has proved to be cost-effective. At the same time, out of pocket (OOP) costs are high in some countries for families because of partial public coverage of services. With EOLC needs expected to grow, there is a risk that this increases public expenditures heavily but also that families bear a great share of both the direct and indirect costs associated with providing informal care.

1.4.1. Publicly funded end-of-life care is available, but there are significant gaps

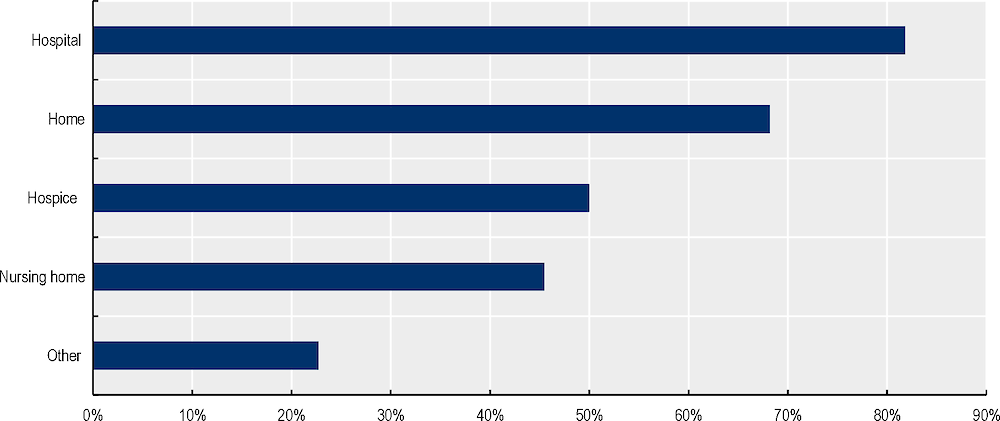

EOLC still heavily relies on hospital settings and can lead to the experience of death being more challenging in other settings, influencing the choice of place of care and death, but also, the overall spending. Funding for EOLC mainly typically comes from health and social security schemes, with health benefit packages being the most common funding system. Current EOLC funds mainly target hospital settings, with 82% of OECD countries having public financing mechanisms for EOLC in hospitals, while only half of the countries have similar mechanisms for hospice and fewer still for nursing home services (Figure 1.9). Studies highlight that 80% of the costs in the last three months of life were attributable to hospital acute care while the costs of palliative care were only close to 10% (Yi et al., 2020[98]). In contrast, palliative care, especially outside of inpatient settings, is correlated with higher patient satisfaction and lower overall health care costs (Public Health England, 2017[99]).

Incentivising home or community care and early access to palliative care services through more appropriate payment mechanisms are paramount. Finding ways to incentivise or removing negative incentives for care outside hospitals is important. For instance, in Victoria, Australia, each additional hospital admission attracts additional funding while this is not the case for community or home‑based palliative care, creating a greater incentive for admissions to hospitals than for community-based treatment (Duckett, 2018[100]). Better pricing and reimbursement mechanisms can incentivise providers to promote palliative care (Duckett, 2018[100]; Groeneveld EI, 2017[101]). Bundled payments have been suggested as an alternative option to integrate curative and palliative care. The United States are moving towards value‑based payments which might favour more palliative care and tested allowing paying for patients to receive hospice services as they continued to receive curative care (CSM, 2022[102]) while the United Kingdom has applied pay-for-performance systems incentivising GPs to identify and manage palliative care needs.

Figure 1.9. Public funding for EOLC mainly targets hospital settings

Affordability of services at the end of life remains an issue. In most countries, a plethora of EOLC services is publicly available or financed (Figure 1.10) but often require out-of-pocket payments that can be high. For instance, while most countries cover opioids and other pain management, in a third of countries this represents partial coverage, similarly to nutrition support and for medication to alleviate vomiting and nausea. Other services, such as spiritual care and bereavement, are not publicly funded in one‑fourth of the countries. Even when they are funded, coverage is partial in 4 out of 10 surveyed countries. Complementary health services such as aromatherapy, relaxation, music therapy, art therapy and reflexology are less widely available, and their availability varies within countries.

Figure 1.10. Publicly available and funded EOLC services in OECD countries

In addition to specific end-of-life care services, care utilisation is high at the end of life, which raises the overall significance of out-of-pocket spending. For instance, data from the United States show that for 25% of households, the total out-of-pocket spending during the last 5 years of life exceeds total household assets and for 40% of the households it exceeds their financial assets (Kelley and al., 2010[103]). Out-of-pocket (OOP) expenses for end-of-life care are significant and there is a risk that gaps in public funding generate unmet needs or catastrophic expenditures. Often the largest single category of out-of-pocket spending is nursing home and hospital expenditures (French and al., 2017[104]). Insufficient public funding for EOLC is likely to exacerbate existing inequalities in the access to such services. Increasing demand for end-of-life care services will require governments to pay particular attention to affordability of these services for users. Some countries, like Korea, have introduced policies to limit out-of-pocket costs.

1.4.2. Heavy reliance on informal carers places a considerable burden on families

Informal carers play an important role in the provision of end-of-life care, but also bear a heavy direct and indirect financial burden related to the OOP expenditure for EOLC and the time invested in providing care, sometimes at the expenses of their job. While informal carers constitute a valuable support for people at the end of life, countries should support them adequately through the provision of financial and psychological support, legislation on work leave and training.

Informal carers face direct and indirect financial burden of end-of-life care. Among OECD countries, between 46% and 86% of people who die at the age of 65 or older received some informal care at the end of life (SHARE, the Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe, 2020[105]). Family caregivers providing EOLC had either given up work, reduced hours at work, or used annual leave or sick leave to cope with the demands of caregiving. Providing informal care can be distressing and affect the carer’s mental health, leading to additional health expenses. Carers also face sometimes additional direct costs such as travel expenses and additional household costs. Total care costs met by informal caregivers are substantial, although they vary widely across countries, with estimates of caregiving ranging from 26.6% – 80% of total costs (Gardiner et al., 2014[106]).

Despite informal carers providing a substantial share of end-of-life care, not all countries provide support to informal carers. Only half of OECD countries provide financial support to informal carers. Better financial support to informal carers would reduce their burden, balancing the generosity of benefits with the size of eligible population, without trapping carers and preventing their labour force participation. While many countries have leave for care at the end of life, in many this is for a reduced period of time or unpaid. Belgium, Denmark, and France have generous paid leave for informal caregivers who are in the labour market.

In addition to financial support, counselling and training are often needed to reduce mental distress when accompanying a relative towards the end of life and improving the quality of care. In addition to being useful to the carers themselves, psychosocial support can have a broader societal financial impact, reducing caregivers’ care utilisation and improving their productivity (KPMG, 2020[107]). Nevertheless, respite care, counselling, training, and other forms of support to informal carers are still inadequate in many OECD countries.

1.5. Strengthening governance and the evidence base for EOLC

1.5.1. The COVID‑19 crisis has highlighted the importance of ensuring adaptability of systems to provide EOLC

The pandemic caught countries unprepared on several fronts. Staff and supply shortages impaired the delivery of care, while lockdowns and other restrictions caused loneliness among people living within facilities or at home with life limiting diseases. End-of-life care services were overwhelmed in the face of the COVID‑19 crisis and people who were dying did not always have their wishes realised. This led to people often dying far from their relatives or at home without adequate care.

Despite most countries issuing guidelines for health care at the onset of the COVID‑19 pandemic, only 6 OECD countries (Canada, Latvia, Luxembourg, Norway, Portugal, and the United States) mentioned palliative care needs and modes of delivery in their guidelines (Rocard, Sillitti and Llena-Nozal, 2021[108]).

Further shocks are expected to happen in the future and countries should prepare now to ensure better resilience of end-of-life care during future crises. In view of future crises, there is a clear need to adapt EOLC services based on the lessons learned during the pandemic. Including EOLC experts within task forces and issuing guidelines on EOLC resilience is the way to prepare the sector to future shocks. The use of shared decision-making tools such as advance directives and living wills can ease decision making in the event of a crisis. During the COVID‑19 crisis, Canada, Ireland, France, the United Kingdom, and the United States issued guidelines on EOLC. The guidelines provided support to professionals transferring patients at the end of life across settings, providing supportive therapies for COVID‑19, performing advance care planning and adequately supporting patients living with dementia (Comas-Herrera, Ashcroft and Lorenz-Dant, 2020[109]; Government of France, 2020[110]; OECD, 2020-2021[63]; Rocard, Sillitti and Llena-Nozal, 2021[108]).

The COVID‑19 pandemic has accelerated the recognition that all people working in health services should be competent in supporting those dying and their families. This requires alternatives to hospital admission with sufficient medical supplies for symptom management and staffing. To avoid staff shortages at home and in the community, in the future, countries need to find better ways of integrating specialist expertise within primary and community settings such as the long-term care sector. During the pandemic, Canada, Norway, Sweden and Slovenia developed training and support concerning EOLC for health care workers (National Competence Service for Aging and Health, 2020[111]; Pallium Canada, 2021[112]; Rocard, Sillitti and Llena-Nozal, 2021[108]).

Countries – such as Belgium, Canada, Sweden, and the United States – also made use of technology to improve care co‑ordination, reduce the movement of patients across settings and facilitate contacts between patients and their relatives despite lockdowns and restrictions. Among OECD countries, 40% among the 25 surveyed countries used technology in EOLC already before 2020, while 24% introduced the use of technology in EOLC during the pandemic.

1.5.2. There is a need for better integrating EOLC into the broader health and social care systems

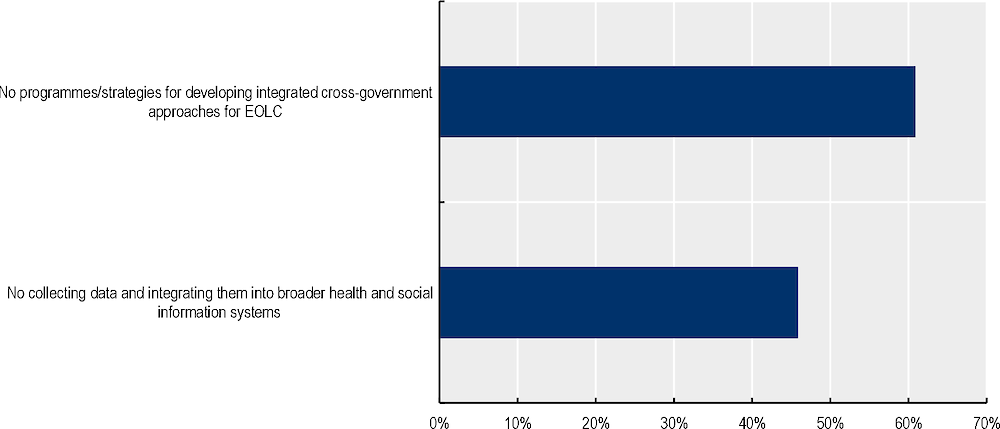

Across OECD countries, 60% of 23 countries surveyed do not have any programme to implement an integrated approach across different levels of government and nearly 50% of 24 countries surveyed do not collect and integrate data on EOLC into broader health and social information systems (Figure 1.11).

Figure 1.11. Most countries do not have well integrated EOLC

Note: Share of countries that replied “No” to the following questions: i) Do you have any national or subnational programmes/strategies for developing integrated cross-government approaches (i.e. across different levels of government and/or across ministries) to EOLC governance; ii) Is data about EOLC (e.g. access, outcomes, financing) collected through specific indicators integrated into broader health and social information systems?

Source: (OECD, 2020-2021[63]).

Some countries have initiatives for integrating end-of-life care into the health care system. Australia, Belgium, Northern Ireland (United Kingdom), England (United Kingdom), Italy and Sweden all have programs to improve the integration of EOLC. Integrating end-of-life care into primary care, for instance, allows earlier detection of patients who need EOLC and thus earlier provision of EOLC services. Shared electronic systems can facilitate co‑ordination across services. Currently, around 60% of OECD countries have a system of secure electronic note sharing for EOLC, such as Australia, Costa Rica, and the United Kingdom. The Netherlands and Norway are currently developing electronic notes sharing and Australia is further improving the existing data availability.

When people reach the end of their life, they are often affected by multi-morbidities that require care from several different professionals, yet there is a lack of an integrated approach to end-of-life care across countries. People often need to repeat the same information to different professionals and might receive discordant opinions and inconsistent service standards. Disjointed services can also generate discontinuities in care when people are discharged from the hospitals. Lack of integrated end-of-life care leads to a hospital-focus in the provision of palliative care.

Interdisciplinary teams and case management would make end-of-life care more integrated in the health care system. Evidence from the Netherlands shows that the percentage of patients who die at home is higher and the number of hospitalisations in the last 30 days of a patients’ life is lower when a case manager is involved offering advice and support (van der Plas AG, 2015[113]).

1.5.3. Countries need a stronger evidence and data infrastructure to monitor and improve end-of-life care

Policies on end-of-life care should be based on strong scientific evidence and thorough research. Nevertheless, more than half of OECD countries (56%) do not have a research agenda for EOLC at the national, regional, or local level, while public funding for EOLC research has fluctuated in recent years (OECD, 2020-2021[63]). In addition to low and fluctuating public funding, the number of funded projects has also been limited, with high variation across countries. The United States appear to have by far the highest number of research projects on EOLC, which are increasing over time, but they still represent a minority in comparison to other areas of research (American Cancer Society, 2021[114]).

Because of the limited research on the topic, gaps exist in the methodologies applied and the topics of focus. Studies are mainly observational and clinical trials only represent a minority of research projects. Improvements in end-of-life care should draw upon scientific evidence. Evidence of people’s preferences, care outcomes and clinical best practices should guide the provision of end-of-life care services. In addition, more efforts must be taken for research to translate scientific results into clinical practice, as evidence is not always incorporated into routine care.

Governments could encourage more research to overcome knowledge gaps which are particularly salient and prioritise funding for research with respect to timeliness of access, models of care, and cost-effectiveness. In addition to reducing barriers around the stigma related to the topic, public efforts should also target addressing broader systemic barriers, especially the limited number of funding sources for palliative care and lack of well-trained investigators (Chen et al., 2014[115]). Belgium, Canada and Norway have provided public funding to specific research centres focusing on end-of-life care, while Ireland, France and the Netherlands have organisations supporting palliative care research (OECD interviews, 2021) (Plateforme nationale pour la recherche sur la fin de vie, 2021[116]; ZonMw, 2021[117]).

Measuring quality of end-of-life care in a systematic and comparable way requires a strong data infrastructure, with comprehensive health data governance, legislation, and policies that allow health data to be linked and accessed. Across the OECD:

16 countries currently have mortality data with the possibility of linkages with health datasets and 10 countries regularly apply such linkages. This is mostly the case for Nordic countries (Oderkirk, 2021[118]).

Sweden and the United States have well-established datasets for end-of-life care, while Ireland and the United Kingdom have already developed specific indicators to measure the quality of EOLC.

Other countries, such as Korea, Luxembourg, and Costa Rica, are currently working on the development of data and indicators on end-of-life care. Further efforts are required to make data available and linked and to design appropriate indicators to monitor end-of-life care services.

References

[5] Alliance for the Care of Dying People (2014), One chance to get it right Improving people’s experience of care in the last few days and hours of life. Alliance members.

[114] American Cancer Society (2021), Current Grants by Cancer Type, https://www.cancer.org/research/currently-funded-cancer-research/grants-by-cancer-type.html (accessed on 2021).

[46] Arianna Working Group (2018), “The “ARIANNA” Project: An Observational Study on a Model of Early Identification of Patients with Palliative Care Needs through the Integration between Primary Care and Italian Home Palliative Care Units”, Journal of Palliative Medicine, Vol. 21/5, pp. 631-637, https://doi.org/10.1089/jpm.2017.0404.

[18] Arias-Casais, N. et al. (2019), EAPC Atlas of Palliative Care in Europe 2019, EAPC Press, http://dadun.unav.edu/handle/10171/56787 (accessed on 16 October 2019).

[82] Au, S. et al. (2018), Outcomes of ethics consultations in adult ICUs: A systematic review and meta-analysis, https://doi.org/10.1097/CCM.0000000000002999.

[84] Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care (2015), National Consensus Statement: essential elements for safe and high-quality end-of-life care, https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/sites/default/files/migrated/National-Consensus-Statement-Essential-Elements-forsafe-high-quality-end-of-life-care.pdf (accessed on 2022).

[50] Bamford, C. et al. (2018), “What enables good end of life care for people with dementia? A multi-method qualitative study with key stakeholders”, BMC Geriatrics, Vol. 18/1, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-018-0983-0.

[78] Bhadelia, A. et al. (2019), “Solving the Global Crisis in Access to Pain Relief: Lessons From Country Actions”, American Journal of Public Health, Vol. 109/1, pp. 58-60, https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.2018.304769.

[79] British Medical Association (2017), Improving analgesic use to support pain management at the end of life, https://www.bma.org.uk/media/2102/analgesics-end-of-life-1.pdf.

[35] Broad, J. et al. (2013), “Where do people die? An international comparison of the percentage of deaths occurring in hospital and residential aged care settings in 45 populations, using published and available statistics”, Int J Public Health, Vol. 58, pp. 257-267, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00038-012-0394-5.

[75] Canadian Institute for Health Information (2018), Access to Palliative Care in Canada, CIHI.

[24] CAPC (2022), Welcome to the CAPC, https://www.capc.org/.

[80] Cardona-Morrel, M. et al. (2016), “Non-beneficial treatments in hospital at the end”, International Journal for Quality in Health Care, Vol. 28/4, pp. 456-469, https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzw060.

[70] CCSA (2020), prescription opioids, https://www.ccsa.ca/sites/default/files/2020-07/CCSA-Canadian-Drug-Summary-Prescription-Opioids-2020-en.pdf.

[17] Centeno, C. et al. (2016), “Coverage and development of specialist palliative care services across the World Health Organization European Region (2005–2012): Results from a European Association for Palliative Care Task Force survey of 53 Countries”, Palliative Medicine, Vol. 30/4, pp. 351-362, https://doi.org/10.1177/0269216315598671.

[88] Centers for Medicare and Medicaid (2021), Hospice Quality Reporting Program (HQRP): Current Meaures, https://www.cms.gov/files/document/current-measuresoct2021.pdf.

[115] Chen et al. (2014), “Why is High-Quality Research on Palliative Care So Hard To Do? Barriers to Improved Research from a Survey of Palliative Care Researchers”, J Palliat Med., pp. 782–787.

[7] Cherny, N. et al. (2003), ESMO takes a stand on supportive and palliative care, Oxford University Press, pp. 1335-1337, https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdg379.

[39] CIHI (2018), Access to Palliative Care in Canada, https://www.cihi.ca/sites/default/files/document/access-palliative-care-2018-en-web.pdf.

[109] Comas-Herrera, A., E. Ashcroft and K. Lorenz-Dant (2020), International examples of measures to prevent and manage COVID-19 outbreaks in residential care and nursing home settings.

[49] Commonwealth Fund (2017), International Health Policy Surveys, https://www.commonwealthfund.org/series/international-health-policy-surveys (accessed on 2022).

[67] Compassionate Communities UK (2022), , https://www.compassionate-communitiesuk.co.uk/ (accessed on 2022).

[58] Crist, J. et al. (2018), “Knowledge Gaps About End-of-Life Decision Making Among Mexican American Older Adults and Their Family Caregivers: An Integrative Review”, Journal of Transcultural Nursing, Vol. 30/4, pp. 380-393, https://doi.org/10.1177/1043659618812949.

[102] CSM (2022), Medicare Care Choices Model, https://innovation.cms.gov/innovation-models/medicare-care-choices.

[72] Dalacorte RR, R. (2011), “Pain management in the elderly at the end of life.”, N Am J Med Sci., pp. 348-354, https://doi.org/10.4297/najms.2011.3348.

[89] Danish Ministry of Health (2018), “National Goals of the Danish Healthcare System”, https://sum.dk/publikationer/2018/november/national-goals-of-the-danish-healthcare-system (accessed on 17 March 2022).

[91] Daryl Bainbridge and Hsien Seow (2016), “Measuring the Quality of Palliative Care at End of Life: An Overview of Data Sources”, Healthy Aging & Clinical Care in the Elderly, Vol. 8, pp. 9-15, https://doi.org/10.4137/hacce.s18556.