This chapter describes the current situation in Latvia related to governance, co-ordination and culture on child protection and justice. It starts with providing an overview of the international standards, national legal frameworks and policies dealing with children’s rights. The chapter then highlights key institutions involved in protecting and safeguarding children’s rights in Latvia. Following that, the chapter provides an overview of practices undertaken by Latvian ministries and agencies to implement child-friendly justice, including roles and responsibilities, co-operation and co-ordination mechanisms, service delivery models, and accompanying resources. It also identifies challenges faced by different actors and institutions.

Towards a Child-friendly Justice System in Latvia

3. Co-ordination, governance and culture of a child-friendly system in Latvia

Abstract

3.1. Status of children and a child rights culture: overview of the vision, the legal and policy framework

Developing a child rights culture requires working to address ingrained societal attitudes, for example regarding violence against children or towards children as rights bearers. Such societal attitudes or inherent biases can influence individuals who work in the justice system and act as significant barriers to achieving child-friendly justice. In order to embed a child rights culture, it is vital that justice officials and the wider community (in which the justice system operates) share a commitment to upholding children’s rights in their work as well as day-to-day interaction with others.

Moreover, developing a child rights-based and child-friendly system requires the country to make children’s rights a cross-departmental priority, so that it becomes everyone’s responsibility to protect and promote a child-friendly system rather than a single institution. The collective effort will then help spread a child-friendly culture throughout Latvian society.

Additionally, it is critical that mutual trust be built between children and public services. Children need to encounter a safe environment in which they feel that they can ask for help, will be listened to and protected, particularly when they report abuse or violence. Equally, it is necessary to develop professionals’ understanding of children and children’s rights, so that they will believe children when they come forward and will trust in children’s ability to exercise their rights responsibly. In order to strengthen a child rights-based approach to services, a number of focus points are highlighted in Box 3.1 below.

Box 3.1. Strengthening a child rights-based approach

Article 1 of the United National Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC) defines a child as “every human being below the age of eighteen years unless under the law applicable to the child, majority is attained earlier” (OHCHR, 1989[1]). A child rights-based approach takes this definition as the base and brings together seven principles to identify the main approach to public services. These principles include:

Dignity

Dignity refers to the acknowledgement of the value, respect and nurturement of the inner dignity of every child and young person

Interdependence and indivisibility

‘Interdependence and indivisibility’ refer to the belief that rights cannot be picked based on the circumstances. In that sense, there is an emphasis for children and young people to enjoy all their rights regardless of the circumstances that might be present.

Best interests

“Best interests” underline that the best interests of children and youth must be prioritised in all decisions and actions that impact them and that children and young people should be active participants in decision-making processes that affect them directly.

Participation

“Participation” emphasises supporting children and young people to actively participate in their family lives, in their community and in broader society not only to be active participants in private and social spheres of life but also to get a chance to express their views and feelings in a free and frank manner.

Non-discrimination

‘Non-discrimination’ promotes treatment of every child and young person in a fair and non-discriminatory manner. In addition, non-discrimination involves supporting individuals who need to overcome barriers and difficulties, in line with the equity principle so that everyone is treated equally.

Transparency and accountability

‘Transparency and accountability’ stresses that open and transparent communication between children, young people, professionals, young people and politicians is needed to bring a rights-based approach into reality and to hold involved parties accountable

Life, survival and development

‘Life, survival and development’ indicates that every child has a right to life and each child and young person should be supported to enjoy the same opportunities to nurture safe, healthy growth as well as development (UNICEF, 2023[2]).

Source: (OHCHR, 1989[1]) Convention on the Rights of the Child, https://www.ohchr.org/sites/default/files/crc.pdf

As seen in the Box below, the legal definition of a child based on Latvian law highlights different conditions and exceptions of being considered a child (Box 3.2).

Box 3.2. Legal definition of a child in Latvia

The status of the child is embedded in the Law on the Protection of the Children’s Rights (LPCR), which defines a child as a person who has not reached the age of 18. Similarly, Section 219 of Latvia states that “the minority of persons continues until they reach the age of eighteen”.

Exceptions include persons who are declared to be of legal age in accordance with the law or have entered into marriage before reaching the age of 18. In accordance with sections 220 and 221 of the Latvian Civil Law, in special cases and upon confirmation by guardians or the minor’s next of kin, an The Orphan’s and Custody Court may declare a minor, who has reached the age of 16 years, as having reached the age of majority. Such a decision by the Orphan’s and Custody Court must be approved by a court of general jurisdiction.

Administrative and criminal liability applies from the age of 14, in accordance with Section 57 of the LPCR, Section 11 of the Criminal Law and Section 6 of the Law on Administrative Liability.

Section 70, Part 1 of the LPCR stipulates that if there are doubts regarding minority of a person, the person shall be deemed a minor until his or her age is ascertained, and such person shall be ensured a relevant assistance.

Source: (LIKUMI, 1998[3])Law on the Protection of Children’s Rights in Latvia, https://likumi.lv/ta/en/en/id/49096; (LIKUMI, 1937[4])Civil Law of Latvia, https://likumi.lv/ta/en/id/225418-the-civil-law; (LIKUMI, 1998[5])Criminal Law of Latvia, https://likumi.lv/ta/en/en/id/88966; (LIKUMI, 2018[6])Law on Administrative Liability, https://likumi.lv/ta/en/en/id/303007-law-on-administrative-liability.

3.1.1. International legal framework

Latvia is a party to seven out of nine core international human rights (OHCHR, n.d.[7]) which set down a solid set of principles to be followed by Latvia and hold it accountable (at legal, political and moral levels) for the respect, protection and realisation of the fundamental rights and freedoms (Box 3.3).

Box 3.3. Main International Human Rights Instruments and International Instruments Combatting Violence Against Children applicable in Latvia

International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination (21 December 1965)

Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (10 December 1984)

Protocol to Prevent, Suppress and Punish Trafficking in Persons, Especially Women and Children, supplementing the United Nations Convention against Transnational Organised Crime (15 November 2000)

ILO Convention No.182 concerning the Prohibition and Immediate Action for the Elimination of the Worst Forms of Child Labour (1 June 1999)

ILO Convention No. 138 on the Minimum Age for Admission to Employment (6 June 1973)

Hague Convention on the Civil Aspects of International Child Abduction (25 October 1980)

Hague Convention on Protection of Children and Co-operation in Respect of Intercountry Adoption (29 May 1993)

Juvenile Justice (Care and Protection of Children) Model Rules (2016)

UN Standard Minimum Rules for the Administration of Juvenile Justice (the Beijing Rules) (29 November 1985)

UN Guidelines for the Prevention of Juvenile Delinquency (the Riyadh Guidelines) (14 December 1990)

UN Rules for the Protection of Juveniles Deprived of their Liberty (14 December 1990)

UN Standard Minimum Rules for Non-Custodial Measures (the Tokyo Rules) (14 December 1990)

Vienna Guidelines for Action on Children in the Criminal Justice System (21 July 1997)

African Charter on the Rights and Welfare of a Child (June 2019)

African (Banjul) Charter on Human's and Peoples' Rights (21 October 1986); American Convention of Human Rights (18 July 1978)

Arab Charter on Human Rights (15 March 2008)

European Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms (3 September 1953)

European Social Charter and Revised Social Charter (26 February 1965)

Cairo Declaration on the Convention on the Rights of the Child and Islamic Jurisprudence (23-24 November 2009)

Source: (OHCHR, n.d.[7])The Core International Human Rights Instruments and their monitoring bodies, https://www.ohchr.org/en/core-international-human-rights-instruments-and-their-monitoring-bodies.

One of the instruments is the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC), to which Latvia acceded in 1992, followed by ratification of two optional protocols - on the sale of children, child prostitution and child pornography in 2016. Under the UNCRC, Latvia is required to undergo regular reviews on the implementation of the convention provision by the committee of experts. The last review of Latvia took place in 2016, encouraging Latvia to make further progress in the implementation of the Convention. For a summary of concluding observations, see Box 3.4

Box 3.4. Child periodic report of Latvia: 2016 concluding observations of the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child

The concluding observations of the 2016 Child Periodic Review of Latvia by UNCRC urged Latvia to make progress on the following: 1) to provide adequate resources to be allocated for the implementation of various laws in order to bring them in full compliance with the Convention; 2) to develop a comprehensive policy and strategy; 3) ensure co-ordination and complementarity among government entities; 4) provide the resources necessary for their effective implementation. The Committee also recommended to strengthen the Children and Policy Department of the Ministry of Welfare and the Children’s Rights Division of the Ombuds Office, utilise a child-rights approach in the elaboration of state and municipal budgets, and organise campaigns to raise awareness about eliminating discrimination.

Source: (OHCHR, 2016[8]), CRC/C/LVA/CO/3-5: Concluding observations on the third to fifth periodic reports of Latvia , https://www.ohchr.org/en/documents/concluding-observations/crcclvaco3-5-concluding-observations-third-fifth-periodic-reports

The next review, including an examination of a country report and submissions from national human rights and NGOs, has been pending since May 2021 (see Box 3.5).

Box 3.5. Child periodic report of Latvia: 2016 recommendations of the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child

With regards to violence against children in Latvia, the Committee recommended to:

Establish an integrated information system for the comprehensive analysis of violence against children, monitor the efficiency of targeted measures and develop an evidence-based policy to prevent and address violence against children

Promptly investigate all reported cases of violence against children and prosecute and sanction perpetrators

Establish a clear procedure for medical staff to record and report cases of violence against children

Establish mechanisms, procedures and guidelines to ensure mandatory reporting of all cases of sexual abuse of children and educate children with mental health disorders about how they can identify and report incidents of sexual abuse

Immediately investigate all cases of sexual abuse in institutions for children with mental health disorders and prosecute and sanction offenders

Strengthen the monitoring of institutions for children with mental health disorders, including training health staff and social workers to detect signs of sexual abuse

Ensure that the Helpline personnel receive regular training on the Convention and its operational protocols, to provide child-sensitive and child-friendly assistance and procedures for following up on complaints

Complement the Helpline with a regular monitoring mechanism to ensure the quality of the support and advice provided

Collect regular and systematic data on the number and types of complaints received and the support provided to victims

Source: (OHCHR, 2016[9]), Child Periodic Report of Latvia: 2016 Recommendations of the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child, https://documents-dds-ny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/G16/049/25/PDF/G1604925.pdf.

Latvia’s membership in the regional organisations – including the European Union as well as the Council of Europe – provides Latvia with additional instruments that strengthen the country’s human rights framework. Latvia is required to respect the provisions of European Union treaties, including the Charter of Fundamental Rights, which guarantees the protection of children’s rights. To ensure that those objectives are properly considered in all relevant policies and actions, the country is also encouraged to apply targeted EU strategies and to continue efforts to develop the National Action Plan to implement the EU Child Guarantee.

In addition, Latvia, as a state party to key conventions of the Council of Europe, has an obligation to promote and protect children’s rights. For example, the Convention on the Protection of Children against Sexual Exploitation and Sexual Abuse (known as the Lanzarote Convention) entered into force in Latvia in 2014. The implementation of the obligations under the Convention is coordinated by five ministries – Welfare, Health, Education and Science, Justice and Interior (none of the ministries has been assigned as the main coordinator) (Box 3.6). In 2021, the Constitutional Court of Latvia ruled that the Istanbul Convention on Preventing and Combatting Violence against Women and Domestic Violence was compliant with the country’s constitution. Ratification of the convention is pending.

Box 3.6. Lanzarote Committee – recommendations for Latvia

The Lanzarote Committee assessed Latvia under the urgent monitoring round on “Protecting children affected by the refugee crisis from sexual exploitation and sexual abuse” (Council of Europe, 2021[10])

Some of the recommendations included:

To put in place effective mechanisms for data collection with a specific focus on children affected by the Ukrainian refugee crisis who are victims or presumed victims of sexual exploitation and sexual abuse and review the possible removal of obstacles to the collection of such data, in particular, where they exist, legal restrictions to do so, with due respect for the requirements of personal data protection

To encourage the co-ordination and collaboration of the different actors who intervene on behalf of and with children affected by the refugee crisis to ensure that preventive measures in regard to protection from sexual exploitation and sexual abuse are in place and protective measures are taken as quickly as possible

To encourage and support the setting up of specific information services such as telephone or Internet helplines to support child victims of sexual exploitation and sexual abuse affected by the refugee crisis as well as persons wishing to help them to provide advice in a language they understand

Source: (Council of Europe, 2021[10])Council of Europe contribution for the 38th UPR session (Jan-Feb 2021) regarding Latvia. Page 7, https://uprdoc.ohchr.org/uprweb/downloadfile.aspx?filename=8704&file=EnglishTranslation.

3.1.2. National legal framework

Latvia’s legal framework around child-rights is underpinned the Constitution of the Republic of Latvia (LIKUMI, 1922[11]) which calls on the state to protect and support the rights of the child. Furthermore, Section 110 of the Constitution sets the duty of the state to provide special support to disabled children, children left without parental care or who have suffered from violence.

The Law on the Protection of Children’s Rights (LPCR), passed in 1998, is Latvia’s main legal text on the protection of children’s rights at the national level (LIKUMI, 1998[12]). Additional aspects of children’s rights are regulated by other laws including Latvian Criminal Law, Criminal Procedure Law, Citizenship Law, Civil Law, Labour Law, Law on Administrative Liability and Law on The Orphan’s and Custody Courts. Several Cabinet Regulations also define the competence of various public institutions and procedures by which the rights of the child shall be upheld. Table 3.1 provides an overview of selected laws and regulations in Latvia covering children’ rights.

Latvia’s Law on the Protection of Children’s Rights

The LPCR (LIKUMI, 1998[12]) highlights the need to afford special protection and care for children, considering their limited physical and mental capabilities and specific vulnerabilities. It prescribes measures pertaining to juvenile rights, freedoms and protection. The law governs the parties responsible for protecting children: parents (or adopters, foster family, guardians of a child), different institutions (educational, cultural, health care, childcare, state and local government), public organisations and employers. In particular, parents are held liable for not fulfilling their parental duties and for abuse of custody rights, and the physical punishment or cruel treatment of a child. Some of the parental duties are also articulated in the Civil Law. It states that until reaching the age of 18, a child is under the custody of her or his parents and parents should care for the child and her or his property and should represent the child in her or his personal and property relations. Regarding civil law, care of the child extends to upbringing, supervision, provision of food, clothing, housing, healthcare, education and safety.

The LCPR places a duty on every citizen to safeguard children and report any cases of violence or any other criminal offence directed against a child to the police or another competent authority. Furthermore, institutions must be informed no later than the same day “with regards to any abuse of a child and criminal offence or administration’s violation against a child, violation of the rights of the child or other threat to a child, and also when the person has suspicions that the child has articles, substances, or materials which may be a threat to the life or health of the child herself/himself or of another person”. In particular, health care, pedagogical, social field or police employees, and elected state and local government officials are held liable for failing to report offences (Box 3.7).

Box 3.7. Definition of child abuse in Latvia

The LCPR (LIKUMI, 1998[12]) defines abuse as physical or emotional cruelty of any kind, sexual abuse, or any other form of mistreatment that endangers or may endanger the health, life, development, or self-respect of a child. This law distinguishes between four types of violence/abuse: sexual violence/abuse, physical violence/abuse, emotional abuse, and neglect. The law defines sexual abuse as the involvement of a child in sexual activities that the child does not understand or to which the child cannot knowingly give his or her consent. Physical abuse is the application of force that threatens the health or life of a child in connection with the child or intentional exposing of the child to harmful factors, including tobacco or smoke. Emotional abuse is the infringement of the self-respect of a child or psychological coercion (threatening, swearing, humiliating, abusing a relative of the child in her/his presence or otherwise harming the emotional development thereof). Neglect is also recognised as a form of violence, which endangers or may endanger the health, life, development or self-respect of a child. Continuous or systematic negligence against a child may harm the child’s development and cause physical or psycho-emotional suffering to the child. Protection from sexual abuse is specifically regulated in Sections 15, 51 and 52 of the LCPR as well as in the Criminal Law of Latvia, while neglect is regulated by Section 1 and Part 9 of the Law.

Source: (LIKUMI, 1998[12])The Law on the Protection of Children’s Rights (1998), https://likumi.lv/ta/en/en/id/49096

The legal provisions also stipulate the set up of an emergency assistance free of charge, to a child who is a victim of a criminal offence, exploitation, sexual abuse, violence or any other unlawful, cruel or demeaning act. It seeks to support a child in regaining physical and mental health and helps with reintegration into society. Such medical treatment and reintegration shall take place in an environment favourable to the health, self-esteem and honour of a child, carefully guarding the child’s intimate secrets. Such assistance is provided by special institutions (e.g., municipal social services) or dedicated sections in general medical institutions that are funded by the State.

Latvia’s Criminal Law defines criminal offenses against children including rape, sexual violence, acts of sexual nature, acts leading to depravity, acts encouraging involvement in sexual acts. The law also specifies the punishments for each offense. The definitions of the offences against children based on the Criminal Law of Latvia can be found in the box below (Box 3.8).

Box 3.8. Latvia’s Criminal Law

The Criminal Law of Latvia (LIKUMI, 1998[5]) defines criminal offenses against children, sets the punishments and outlines the main guidelines for the process. Importantly, definitions of emotional, physical and sexual violence provided in the Criminal Law differ from the ones set out in the LPCR. Criminalised forms of emotional and physical violence under general provisions applying to children include: intentional serious bodily injury (Section 125), intentional moderate bodily injury (Section 126), intentional slight bodily injury (Section 130), torture (Section 130¹), threatening to commit murder and to inflict serious bodily injury (Section 132), human trafficking (Section 154¹), causing condition of drunkenness of a minor, involving a minor in non-medical use of therapeutic medicaments and other means which cause intoxication (Section 173), cruelty towards and violence against a minor (Section 174).

Criminalised forms of sexual violence against children are:

Rape – an act of sexual intercourse taking advantage of the state of helplessness of a victim or an act of sexual intercourse against the will of the victim by means of violence, threats or using trust, authority or exerting other influence over the victim (Section 159).

Sexual violence - acts of a sexual nature for the purpose of sexual gratification in physical contact with the body of the victim, if such acts have been committed taking advantage of the state of helplessness of a victim or against the will of the victim by means of violence, threats or using trust, authority or exerting other influence over the victim (Section 160).

Acts of a sexual nature with a person who has not attained the age of sixteen years - an act of sexual intercourse, anal or oral act, or sexual gratification in an unnatural way, or other acts of a sexual nature in physical contact with the body of the victim, if it has been committed on a person who has not attained the age of sixteen years and if such offence has been committed by a person who has attained the age of majority (Section 161).

Leading to depravity (of a person who has not attained the age of sixteen years or who is in a state of helplessness) - acts of a sexual nature without physical contact with the body of the victim for the purpose of sexual gratification or to arouse the victim’s sexual instinct, if such act has been committed by a person who has attained the age of majority or it has been committed by taking advantage of the state of helplessness of the victim or against the will of the victim by means of violence, threats or using trust, authority or exerting other influence over the victim (Section 162).

Encouraging involvement in sexual acts - encourages a person who has not attained the age of sixteen years to meet with the purpose to commit sexual acts or enter into a sexual relationship using information or communication technologies or other means of communication, if such an act has been committed by a person who has attained the age of majority (Section 162).

Latvia’s Criminal Law also establishes that the age of criminal liability starts at 14 years of age and stipulates the forms of punishment for minors - persons who have not reached the age of 18 - until who have been convicted of committing a criminal offence. The basic forms of punishment are deprivation of liberty (up to 10 years and, in some cases, up to 15 years), community service, fine (only to those minors who have their own income), among others. If a person commits a criminal violation before reaching the age of 18, their criminal record will be erased after they have completed their punishment.

Source: (LIKUMI, 1998[5]), Criminal Law of Latvia, (1998), https://likumi.lv/ta/id/88966-kriminallikums.

In addition to the laws defined above, there are other laws and regulations in Latvia that regulates criminal offences against children (see Table 3.1).

In addition, to facilitate a successful introduction of the Barnahus model, the Latvian government reports that it has prepared a series of amendments to the legal framework laws to ensure the coherence of national legislation and practice and compliance with international standards. For example, the draft amendments of the LPCR aim to recognise the importance of the Barnahus model in providing intervention measures in the best interests of the child, in assessing the situation of children, who have suffered from criminal offences and in ensuring coordinated responses by relevant institutions (International Labour Organization, 2000[15]).

Table 3.1. Selected laws and regulations in Latvia

|

Laws and regulations |

Year |

Description |

|---|---|---|

|

Criminal Procedure Law |

2005 |

It regulates the investigation process involving juvenile victims by describing the main stakeholders involved in criminal proceedings, the rights of a minor in criminal proceedings and the interview process of a minor. Criminal proceedings related to violence committed by a person upon whom the minor victim is financially or otherwise dependent, or regarding a criminal offence against their morals or sexual inviolability, where the victim is a minor, take priority. |

|

The Law on Orphan’s and Custody Courts |

2007 |

It regulates the rights and duties of The Orphan’s and Custody Court - a guardianship and trusteeship institution established and financed by a local government. The Orphan’s and Custody Court can terminate custody rights, decide to provide out-of-family care to the child, decide on adoption of the child, deal with property issues, settle disputes and perform other functions specified in the law. |

|

Cabinet Regulations “Rules on the Minimum Amount of Child Support” |

2013 |

It stipulates the minimum amount of means of support that each parent, regardless of his or her ability is obliged to provide to each of his or her children (in 2021 this amount was EUR 150 00 per month for children who have reached the age of 7 and EUR 125 00 for children under 7). |

|

The Law on Administrative Liability |

2020 |

It establishes the age of administrative liability to be 14 years. It prescribes compulsory measures of a correctional nature to minors between 14 and 18 years of age who have committed administrative offences. An alternative is an administrative penalty set out as a half of the fine which would be applied to a person of legal age. |

|

The Law on Application of Compulsory Measures of a Correctional Nature to Children |

2005 |

It defines the following compulsory measures that may be applied to children in Latvia: a warning, a duty to apologise to the victims, placing a child in the custody of parents or guardians and other persons, authorities or organisations, a duty to eliminate by his or her work the consequences of the harm caused, a duty to reimburse the harm caused, specific behavioural restrictions, a duty to perform community services, placing a child in an educational establishment for social correction. |

Note: Criminal Procedural Law (2005); The Law on Orphan’s and Custody Courts (2006); The Law on Administrative Liability (2020); The Law on Application of Compulsory Measures of a Correctional Nature to Children (2005). In 2023, there will be an increase in the minimum wage from EUR 500 to EUR 620 per month. The minimum amount allocated for children under 7 will be EUR 155 and for children who have reached the age of 7 will be EUR 186 per month.

Source: (LIKUMI, 2001[13]), Legal Acts of the Republic of Latvia, https://likumi.lv/about.php; (European Commission, 2023[14]), European e-Justice Portal, https://e-justice.europa.eu/47/EN/family_maintenance

3.1.3. Policy framework

The ongoing efforts to establish a child-rights culture also require setting up a solid policy framework that outlines the main actions by the government, the state institutions as well as stakeholders. Together with Latvia’s national legal framework on children’s rights, a number of policies are also relevant for the implementation of child-friendly justice policies as well as a child rights-based culture. As noted, the key and long-term policy planning document is the Sustainable Development Strategy of Latvia until 2030. but the document highlights the range of important elements for children’s well-being, such as access to quality education and childcare, poverty eradication, social support to eliminate inequalities and exclusion, among other goals. The National Development Plan of Latvia for 2021-2027 in turn integrates measures to enhance violence prevention in educational institutions and among young people, improving the system for protection of the rights of the child and ensuring co-operation by reassessing the roles of national and municipal level authorities, including the Orphan’s and Custody Court, and by reforming the juvenile crime prevention system.

The central political document in Latvia is the Declaration on the Intended Activities of the Cabinet of Ministers. A Government Action Plan for the years 2019-2022 had been developed to implement the declaration. It aims to make Latvia the most child-friendly country and society for families, by implementing a comprehensive long-term state support programme for families with children. The tasks have been assigned to the co-operation platform “Centre for Demographic Affairs”. Building on these documents, each ministry develops its own mid-term and short-term policy planning guidelines.

Child related policy documents developed by Ministries in Latvia

There is a wide range of policy documents related to children’s well-being in Latvia, which have been developed by different institutions in Latvia in the areas of their authority:

The Plan for the Prevention of Child Crime and Protection of Children against Crime for 2023-2024 and other documents (Box 3.9), developed by the Ministry of Interior, which is responsible for developing three-year programmes for the prevention of crime committed by children and for the protection of children from crime

Box 3.9. Policy documents by the Ministry of Interior

The Plan for the Prevention of Child Crime and Protection of Children against Crime for 2023-2024 (Ministery of Interior Republic of Latvia, 2023[16])was adopted on 23 March 2023. The decision to develop this plan was based on the 2020 evaluation report of the implementation of the Guidelines for 2013-2019.1 The evaluation found that while most actions in the Guidelines had been successfully implemented, they were ineffective in reducing the number of crimes against children (Police of Latvia, 2019[17]). It pointed to data on a growing problem of sexual violence against children and online violence. Similarly, it stated that the results do not indicate an improvement in the co-ordination and planning of crime prevention and control measures.

The previous policy document, Guidelines for Prevention of Child Crime and Protection of Children against Criminal Offenses for 2013-2019, outlines various objectives related to tackling crimes perpetrated by children, prevention of factors that contribute to criminal behaviour, and improvement of safety of children by protecting them from health and life-threatening risks (Police of Latvia, 2019[17]). In total, the document included 49 actions to be implemented over a seven-year period and were divided into two sub-objectives: to improve the inter-institutional co-operation model and to promote a child-friendly environment. The document was drafted in accordance with international standards aimed to protect children from health and life-threatening risks.

1. The draft plan is prepared by the Ministry of Interior awaiting approval for the final version by the ministries.

Policy documents, developed by the Ministry of Welfare, which is responsible for developing long-term policies related to the protection of child rights, including alternative care for orphans and children left without parental care, in line with the LPCR (LIKUMI, 1998[3])(Section 62, Part 1), as well as for approving the annual state programme for the improvement of the condition of children and family (Box 3.10).

Box 3.10. Policy documents by the Ministry of Welfare

Latvia’s Family Policy Guidelines for 2011-2017 sought to promote family formation, stability, prosperity and birth rates, as well as to strengthen the institution of marriage and its value in society, articulated in 52 actions. Two action plans were developed for the implementation of the Guidelines, one for 2012-2014, another for 2016-2017. Each section included specific objectives and activities, namely promoting awareness about domestic violence, facilitating its detection, reporting, while improving inter-institutional co-operation of services and standardising the actions of specialists (“Family Stability”). Other goals included reducing the risks to the child’s physical and emotional integrity (“Support for the Exercise of Parental Responsibility”). An ex-post evaluation report from 2018 concluded that “in general, existing policies can be seen as reactive rather than proactive, with a stronger focus on promoting the recognition and detection of violence and providing of rehabilitation” and “the least attention is paid to the prevention of violence”.

The Ministry of Welfare has adopted the Guidelines for Development of Children, Youth and Family for 2021-2027, which was approved and came into force on 21 December 2022. The document is based on the National Development Plan for Latvia for 2021-2027 (Government of Latvia, 2020[18]) and sets the basic principles, goals and tasks of the state policy for children, youth and families. The main goal of the draft plan is the establishment of a child and family-friendly society that promotes the well-being of children and youth, healthy development, equal opportunities and the reduction of the risk of poverty and social exclusion for families with children. There are four objectives, one of which is to promote the safety, development, psychological and emotional well-being of children and young people. One of the lines of actions under this objective is to reduce all forms of violence with the corresponding five tasks:

Educational activities encouraging school children to recognise violence and respond to risks of violence;

Public awareness-raising campaigns to reduce tolerance of all forms of violence (United Nations, 2016[19]);

Expand protection and rehabilitation services for victims of violence;

Activities to reduce discrimination and violence (harassment and abuse) in educational institutions and online;

Establish an evidence-based and joint methodology-based violence monitoring system.

The draft plan also states that two additional policy documents will be developed: a “Plan to Promote Safety, Psychological and Emotional Well-Being of Children and Young People for 2022-2027”; and the adopted “Plan for the Prevention of Child Crime and Protection of Children against Crime for 2023-2024”. (Ministery of Interior Republic of Latvia, 2023[16])

Furthermore, the annual State Programme for Improving the Situation of the Child and Family aims to improve the situation of children and families, as well as to implement targeted measures to protect and respect children’s rights. The State Programme is jointly implemented by the Ministry of Welfare and the State Inspectorate for the Protection of Children’s Rights.

Source: (United Nations, 2016[19]), Committee on the Rights of the Child, https://tbinternet.ohchr.org/_layouts/15/treatybodyexternal/Download.aspx?symbolno=A%2F71%2F41&Lang=en, (Ministery of Interior Republic of Latvia, 2023[16]), Plan for the Prevention of Child Crime and Protection of Children against Crime for 2023 – 2024, https://likumi.lv/ta/id/340435-par-bernu-noziedzibas-noversanas-un-bernu-aizsardzibas-pret-noziedzigu-nodarijumu-planu-2023-2024-gadam.

Public Health Policy Guidelines for 2021-2027 and policy materials, prepared by the Ministry of Health, which is responsible for the development of policies related to children’s health care, in particular medical rehabilitation, as stated in the LPCR (LIKUMI, 1998[12])1(Box 3.11).

Box 3.11. Policy documents by the Ministry of Health of Latvia

Building on the World Health Organization’s Regional Strategy for Europe “Health 2020”, the Latvian Ministry of Health prepared the Public Health Policy Guidelines for 2021-2027 (LIKUMI, 2022[20]). The Guidelines included certain activities related to the prevention of violence, such as defining the necessary measures for regular training of health professionals on violence, identifying problems of inter-institutional co-operation and measures to address problems related to violence.

The Latvian Health Improvement Plan for Mother and Child for years 2018-2020 is another document that recognised the importance of tackling violence perpetrated against children. It provided for the education of 325 medical practitioners on preventing, recognising and reacting to violence against minors. The programme was not extended after 2020 but its activities were instead integrated into the Public Health Policy Guidelines for 2021-2027 (Ministry of Health Latvia, 2020[21]), while the Health Improvement plan for Mother and Child was not developed for the next period.

Source: (Ministry of Health of Latvia, n.d.[22]), Ministry of Health of Latvia, https://www.vm.gov.lv/lv.

The Plan for the protection of minors against criminal offences against morality and sexual inviolability for 2018-2021, prepared by the Ministry of Justice in co-operation with other ministries, institutions and NGOs (See Box 3.12).

Box 3.12. Plan for the Protection of Minors Against Criminal Offences, Against Morality and Sexual Inviolability for 2019-2020

The main objective of Plan for the Protection of Minors Against Criminal Offences, Against Morality and Sexual Inviolability for 2019-2020 was to reduce the risk for minors caused by crimes against morality and sexual inviolability by addressing global recommendations to promote the implementation of international conventions (of the United Nations and the Council of Europe). There are three actions outlined in the plan:

a. primary prevention measures (awareness of the general public – children, parents, family members, specialists who work with children);

b. secondary prevention measures (awareness of the high-risk target groups – children and parents, persons who fear that they could abuse minors, specialists that work with children);

c. tertiary prevention measures (support system for child victims and preventive coercive measures for former convicts).

The implementation of the plan was overseen by a supervisory committee formed by the institutions involved in the implementation of the plan.

Source: (LIKUMI, 2019[23]), Plan for the protection of minors from criminal offences against morality and sexual inviolability for 2019-2020, https://likumi.lv/ta/id/307955-par-planu-nepilngadigo-aizsardzibai-no-noziedzigiem-nodarijumiem-pret-tikumibu-un-dzimumneaizskaramibu-2019-2020-gadam.

Despite the comprehensive sectoral coverage of the protection of children’s rights, a coherent, comprehensive, cross-government vision for children’s access to justice in Latvia is still lacking. Significantly, there is currently no overarching strategy for children, for children’s rights, or for child-friendly justice in Latvia. There is a need to strengthen the interactions between sectoral plans and strategies that could accelerate the process of developing the system for protecting children’s rights. Any action in that regard could have a greater, inter-sectoral impact. To that end, the role and significance of the centre of government (e.g., State Chancellery), which operates under the direct authority of the Prime minister, which oversees the development of national planning and co-ordination, could be strengthened (Cross Sectoral Co-ordination Center, n.d.[24]).

3.1.4. Child-rights culture in Latvia

Stakeholders reported that Latvian culture, as well as the LPCR and Civil Law (LIKUMI, 1998[3]), put an emphasis on parental responsibility and family privacy. When children experience problems, their parents are considered responsible for their care and are held liable if they fail to protect or control them. Some of the attitudes that were highlighted concern the way adults behave. For example, it was mentioned that when children commit offences, adults may show little sympathy for the underlying reasons and they are often in favour of harsh penalties. When they need help and support, many children and young people were reported to not believe that adults would listen to them, take them seriously, or act in their best interests.

There is also widespread fear and shame in society about discussing child abuse and sexual violence against children, as well as a concern for confidentiality of such sensitive and personal information. Parents are often reluctant to talk about incidents with anyone outside the family, so they may not approach general practitioners or social workers. Violence within families is considered a private matter by a high percentage of the population (United Nations, 2006[25]). However, parents are often reported to be reluctant to talk about sensitive situations even within their family circles. Stakeholders reported that these phenomena reflect a mind-set that runs deep in the culture of Latvian society. For instance, there is often a lack of understanding and sympathy for children in vulnerable situations. Parents can become angry with their children and blame them for accessing illegal content online. Such attitudes within society can create a difficult environment for developing a positive culture towards children’s rights within the justice system.

There is a risk that some of the attitudes found in wider society are also reflected within the Latvian justice and child protection systems. One study found that many professionals within law enforcement institutions shared the opinion that children and adolescents who had offended were solely to blame for their behaviour and deserved harsh penalties (Kronberga and Zermatten, 2012[26]).

Indeed, although the overall impression is that the justice system in Latvia is making progress in terms of developing a child rights-based culture, the system can appear, at times, more focussed on punishing offenders than protecting and supporting victims. For example, the resources allocated to investigating and prosecuting offenders vastly outweigh those expended on supporting victims.

A key area for development is creating safe environments for children and young people to feel comfortable to ask for help or report abuse and violence knowing that they will be protected. When asked to identify why detection rates in child abuse cases are low, both police and prosecutors sometimes pointed to children’s reluctance to report, whereas other interviewees cited children’s lack of trust in authorities. At the same time, some interviewees said that evidence submitted by children or their opinions and points of view were not always reliable, as they could be influenced by their parents. And indeed, while many professionals demonstrate a deep commitment, paternalistic attitudes may prevail where the child is deemed not to know what is in their best interest or that they cannot ‘be right’.

While many professionals demonstrate a deep commitment, some highlighted that children’s evidence and views were not always reliable as they could be influenced by their parents.

These attitudes can create an environment in which it becomes challenging to establish a positive child rights culture in a justice system that is currently geared more towards punishing offenders while offering insufficient support to victims. To that end, efforts to establish practices to change attitudes within society towards child victims of abuse, violence and crime are essential in creating a child rights-based culture.

3.2. Towards a whole-of-state approach to child-friendly justice

Supporting children’s and young people’s needs requires strategic action and effective responses by different levels of government and state. Unified under a whole-of-state approach, those responses need to be centred around children’s specific needs, rights as well as their changing capacities and circumstances (OECD forthcoming, 2023[27]). Yet ensuring an effective whole-of-state response requires breaking down silos and embedding horizontal co-ordination and integration into policy design and implementation processes. The whole-of-state approach strongly correlates with integrated public service delivery. To enhance capacities to respond to children’s unique and complex needs and problems, and to improve the effectiveness of traditionally fragmented service delivery, this model draws on the wide variety of joined-up services to serve children and young people, such as the Barnahus model. For the establishment of an effective child-friendly system governance, some guiding principles are stated in the box below, in line with the forthcoming OECD Framework for Child-friendly justice, see Box 3.13.

Box 3.13. Guiding principles for a child-friendly justice system governance

The OECD forthcoming Framework on Child-Friendly Justice recommends the following principles for the implementation of an effective child-friendly justice system governance.

A clear leadership structure should be in place to deliver child-friendly justice, supported by high-level political commitment and a whole-of-government approach that recognises the inter-relationship of children’s needs.

Multi-dimensional, targeted, unified and coordinated responses by different levels of government are needed for effective design, implementation and delivery of services.

Children’s specific needs, rights and particular circumstances as well as their changing capacities should be considered for effective policy design and targeted service delivery. A clear vision for the desired outcomes as well as identification of conditions for long-term sustainability of child-friendly policies are essential for successful service delivery.

In order to ensure a system of justice that is fair, impartial and trusted by children and wider society, the state upholds the rule of law by ensuring judicial independence and eradicating bias and corruption.

Sufficient national investment in children’s access to justice should be made with child-specific budgets clearly identified in government strategies and plans.

Sufficient resources should be made available to local authorities and NGOs to ensure the effective local implementation of child-friendly justice measures.

Adequate staffing, facilities, IT and other infrastructure should be in place to ensure the effective implementation of child-friendly justice measures.

Effective systems should be implemented to monitor and scrutinise the efficient use of resources for child-friendly justice.

Source: (OECD forthcoming, 2023[28]) OECD Framework for Child-friendly Justice (forthcoming).

3.2.1. Key institutions involved in safeguarding children’s rights in Latvia

The LPCR lays the foundation for inter-institutional co-operation stating that protection of the rights of the child shall be implemented in collaboration with the family, state and local government authorities, public organisations, and other natural and legal persons. This provides for a system-wide approach which recognises that all public institutions and branches of the state have a strong role to play in safeguarding children’s rights.

In general terms, child protection and justice services are provided by a wide range of actors, including government ministries and agencies, independent institutions such as courts and Ombuds office, municipalities, NGOs, community-based organisations, and other stakeholders (see below).

Institutions formulating laws and policies and providing justice services

The LPCR specifies the competence of the Cabinet of Ministers, different ministries, local governments and other institutions to develop relevant laws, policies and necessary regulations to protect children’s rights (See Table 3.2). The scope encompasses various areas of child well-being as well as institutional setups and service provision that require mobilisation of various stakeholders and their close co-operation.

Table 3.2. Main tasks and responsibilities of key institutions in Latvia

|

Institution |

Main tasks and responsibilities |

|---|---|

|

Ministry of Welfare |

|

|

Ministry of Justice |

|

|

Ministry of Education and Science |

|

|

Ministry of Health |

|

|

Ministry of Interior |

|

|

Municipality, local government and a town local government |

|

1. If a child is found in dangerous conditions (for life and health) local governments and state institutions shall provide assistance. Section 67, Part 5 of the Law on the Protection of Children’s Rights (LIKUMI, 1998[12]) define dangerous conditions as including lack of secure accommodation, warmth and clothing, and nutrition appropriate to the age and the state of health of the child, and violence against the child.

Source: Information provided by the Government of Latvia (2022).

Institutions engaged in child protection and justice

There are a number of institutions protecting children’s rights in Latvia, with the main ones being: the Orphan’s and Custody Courts, The State Inspectorate, the Ombuds Office and the Children’s Clinical University Hospital.

The LPCR entrusts parents or child’s guardians with the primary responsibility and duty of protection of a child and her or his rights. Where child’s family is unable to fulfil its duties, the protection of and representation of the rights and interests of a child are guaranteed by the Orphan’s and Custody Courts (LIKUMI, 2006[29]). Despite its name, the Orphan’s and Custody Court does not belong to the judiciary but is positioned as a guardianship and trusteeship institution. It exercises its powers and perform its duties for custody rights, out-of-family care, adoption, property issues, and dispute settlement among others. The establishment, management (e.g., education and psychological support) and financing of the Orphan’s and Custody Courts lie with the local governments (municipalities), though some functional supervision and assistance are provided by central institutions. For instance, the State Inspectorate oversees matters related to termination, deprivation, restoration of terminated custody and out-of-family care. It provides methodological assistance and organises the assessment of professional development of key employees. Likewise, the Ministry of Justice provides methodological assistance related to certification and settlement of inheritance matters. The decisions by the Orphan’s and Custody Court may be appealed in court by the interested party in accordance with the Administrative Procedure Law. The Orphan’s and Custody Court officials in turn have the right to talk to a child regarding some matters where it is necessary to hear child’s opinion without the parent or a representative being present. In addition, social service representatives also have a duty to hear child’s opinion when necessary, within the limits of their competence.

The State Inspectorate in turn is a central state institution responsible for the protection of children's rights. The functions of the State Inspectorate are twofold: first, it holds broader responsibilities related to monitoring, research, analysis, and training; second, it provides a direct support to children and adolescents, as well as to foster families. The major tasks of the State Inspectorate include monitoring compliance with the law regulating the protection of children’s rights; researching and analysing the overall situation in the protection of children’s rights; producing recommendations for ensuring and improving the protection and implementation of children’s rights (both by national and municipal institutions); informing the public about children’s rights; and providing training and seminars for professionals working with children. The State Inspectorate has the power to engage with children directly, i.e., it can conduct negotiations or interview children without the presence of other persons. It is further responsible for ensuring the operation of the helpline for children and adolescents; for examining complaints regarding children's rights; providing psychological and emotional support to children and their parents in critical situations (via helpline, e-mail or meetings); and working with foster families (i.e., co-ordination, psychological help and support groups). The State Inspectorate also has the right to speak to children without parents or other representatives being present (State Inspectorate for the Protection of Children’s Rights in Latvia, n.d.[30]).

Furthermore, in the context of a wider human rights protection system in Latvia and on the basis of the LPCR, the Ombuds Office plays an important role in informing the public of the rights of a child, examining complaints regarding violations of the rights of the child, paying particular attention to violations committed by state or local government institutions and their employees, and submitting proposals that ensure laws and policies are compliant with children’s rights (Ombudsman Office of the Republic of Latvia, n.d.[31]). The Ombuds Office is a full member of the European Network of Ombudspersons for Children and acts as the Ombudsperson for Children.

Finally, the Children’s Clinical University Hospital provides state-funded and targeted health care services to children at the out-patient clinic (outpatient department, multifunctional building) along with emergency and critical care services. At the end of 2021, the hospital had 2 007 employees, of which 533 were doctors, 632 were medical and patient care staff (certified/registered physician assistants, nurses, midwives, biomedical laboratory assistants, radiologist assistants, radiographers, masseuses, podiatrists), 279 were medical and patient care support staff (nursing assistants) (Children's Clinical University Hospital, Latvia, 2021[32]).

In addition, there are several institutions of the justice system in Latvia that deal with issues involving child rights and justice:

Court system - the judicial power is exercised by city, district, regional and supreme courts. Civil and criminal proceedings are heard in 40 courts. There are 34 city/district courts, 5 regional courts and a Supreme Court. There is no special court system in Latvia that is designed specifically for children or that would only deal with matters related to children or families; all cases are heard in the ordinary courts. In case of violence against children, criminal justice institutions in Latvia are involved in the legal protection of children’s rights. They perform their duties within their general mandates; although there is a lack of specialisation across police, prosecution office or courts, some efforts have been taken to improve the capacities of the system to assist children (see Chapter 4).

State police - standard tasks of the state police include: to guarantee the safety of persons and the society, to prevent criminal offences and other violations of law, to detect criminal offences and search for persons who have committed criminal offences, to provide assistance to institutions, private individuals and associations of persons in the protection of their rights and performance of the tasks specified by law, to carry out administrative and criminal punishments. Within this mandate, any child can seek help directly from the state police. To assist children, police have developed informative and educational presentations for children and youth on safety on the internet, pointing out the possible dangers online, and in interpersonal relations – with special attention to violent behaviour. Only police officers with special knowledge regarding communication with a minor during criminal proceedings can interview minors.

The Prosecution Office – the primary role of the Prosecution Office is to respond to violations of law and ensure that the case is decided in accordance with the procedures laid down by law. Prosecutors must have special knowledge and training in the field of protection of the rights of the child. The Prosecution Office is also responsible for ensuring that the rights of the child are complied with during pre-trial investigations.

All these institutions play a critical role in child protection and justice in Latvia. At the same time, stakeholders reported a certain level of fragmentation of roles and responsibilities, with some elements of overlapping responsibilities between the State Inspectorate and municipalities, as well as uneven coordination and collaboration between different actors. In recognition of these challenges, Latvian authorities have been taking active steps, including the creation of Co-ordination Council on Child Matters, which includes representatives from the main public institutions, municipalities, NGOs and other stakeholders (see below). Yet further efforts would be beneficial, including the provision of a clear framework for action, developing clear policies and guidelines that define the roles and responsibilities of all involved stakeholders, enhancing inter-agency protocols, including processes for communication, referral, and collaboration, strengthening capacity, fostering a culture of collaboration and putting in place robust systems for monitoring and evaluation, including data collection on service delivery and child outcomes.

3.2.2. Role of NGOs and civil society

Civil society and NGOs can play a key role in designing and delivering joined-up policies and services that meet the holistic needs of children as opposed to the rigid structures of large institutions. The Government of Latvia reports providing opportunities for their involvement, for instance, as part of the Co-operation Council on Child Matters. As per the LPCR (LIKUMI, 1998[3])), the Council serves as an advisory collegial body with the objective of promoting a unified understanding on the conformity with the principle of priority of a child's interests in local government and State action policies. The Council also aims to promote coordinated activity of authorities, including cooperation groups, in the protection of children's rights (also see below).

Box 3.14. Examples of collaborative initiatives with NGOs and civil society

A few examples of collaborative initiatives are outlined below:

The development of the Barnahus model in Latvia was driven by the Dardedze Centre initially, with support from the Government.

The Latvian Child Welfare Network (Latvian Child Welfare Network, n.d.[33])is contracted by the Ministry of Welfare to lead the provision of social rehabilitation services for children (LIKUMI, 2009[34]) and has set up safe rooms for interviewing children in several crisis centres throughout Latvia.

The Marta Centre provides joined-up support to girls and women involved in legal proceedings through a team of social workers, lawyers and psychologists.

Social rehabilitation services for victims of human trafficking are provided by the Shelter Safe House and the MARTA Centre (Ministry of Interior of Latvia, 2023[35]).

NGOs play an important role in other key services for children and young people.

The “Plan for the Protection of Minors against Criminal Offences against Morality and Sexual Inviolability for years 2018-2021” involved NGOs in its development.

The establishment of the NGO Fund in 2016, a State budget programme managed by the Social Integration Fund, aims to promote sustainable development in Latvia’s civil society (OHCHR, n.d.[7]).

Note: UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR), National report submitted in accordance with paragraph 5 of the annex to Human Rights Council resolution 16/21: Latvia, 2021, A/HRC/WG.6/38/LVA/1

Source: (Latvian Child Welfare Network, n.d.[33]), About us, https://www.bernulabklajiba.lv/about-us/; (LIKUMI, 2009[34]), Procedure for providing the necessary assistance to a child who has suffered from illegal activities; https://likumi.lv/ta/id/202912-kartiba-kada-nepieciesamo-palidzibu-sniedz-bernam-kurs-cietis-no-prettiesiskam-darbibam; (Ministry of Interior of Latvia, 2023[35]), Informative Website about trafficking in human beings, http://www.cilvektirdznieciba.lv/lv/valsts-nodrosinatie-socialas-rehabilitacijas-pakalpojumi-cilvektirdzniecibas-upuriem; (OHCHR, n.d.[7]), The Core International Human Rights Instruments and their monitoring bodies, https://www.ohchr.org/en/core-international-human-rights-instruments-and-their-monitoring-bodies.

Nevertheless, in 2016, the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child indicated that NGOs were “not systematically involved in the development, implementation and monitoring of actions regarding children’s rights” and recommended that the State party establish an effective mechanism for doing so (United Nations, 2016[19]). The OECD’s interviews with multiple stakeholders re-confirmed those challenges and found that state institutions’ involvement of and co-operation with civil society and NGOs could be improved. There was a sense of a mutual distrust caused by limited funding and disagreements over practice and policies. Despite successful initiatives, consistent collaboration, support and adequate funding for civil society and NGOs are still required. To that end, there is scope to reconsider the budget available for the NGOs for the services they provide.

3.3. Inter-institutional co-operation and co-ordination at national and municipal levels

To respond to the unique pattern of children’s needs, the inter-related nature of their legal and justice problems, and the common fragmentation of services for this age group, it is vital that co-ordination and co-operation between relevant institutions be continually strengthened. Indeed, the key aim of improving co-ordination and co-operation between institutions is to improve the support and services that children receive. This is particularly important in order to protect children who have suffered violence or abuse and need to be safeguarded from the risks of re-victimisation. Efforts in this area need to go beyond legal and justice institutions to extend across the health, education, social, children and families, and youth sectors as part of a whole-of-government approach to children’s access to justice. Improved co-ordination is also needed at both policy and service levels, and at national, regional and local levels.

Sound co-ordination of systems and services for children and young people is a challenge in many countries, including in Latvia, as also underscored in the recent evaluation of a Ministry of Interior’s programme on child crime prevention and protection of children against crime (Ministry of Interior Latvia, 2021[36]). It was reported that government departments and large institutions tend to end up operating in silos, each with their own responsibilities, aims, budgets and culture, with little capacity to focus on the broader picture. Ultimately, this was seen as resulting in services for children that are fragmented, inaccessible and inefficient.

The OECD country experiences show that successful co-ordination for child-friendly justice requires many elements covered elsewhere in this assessment to be in place, including:

Joined-up policy-making and a shared vision for multidisciplinary and integrated services among all relevant stakeholders

A child rights-based and child-friendly justice culture across all partners

Mechanisms for building trust between different professions

Clear leadership for child-friendly justice, a whole-of-government approach and adequate resources

Early intervention and prevention approaches (OECD forthcoming, 2023[28]).

To this end, the next sections provide an overview of co-operation mechanisms at national and local levels, as well as referral and reporting protocols at the level of service delivery.

3.3.1. Co-operation mechanisms at national and local levels

The importance of co-operation between different institutions working in the field of protection of children rights in Latvia was underscored by the LPCR (LIKUMI, 1998[3]), (Cabinet Ministers Republic of Latvia, 2017[37]). It requires institutions to put in place the Co-operation Council in Children Matters (Ministry of Welfare, 2020[38]) at the national level and Children’s Rights Co-operation Groups (CRCG) at the municipal level.

The Co-operation Council in Child Matters is an advisory collegial institution, the aim of which is to promote a common understanding of the observance of the principle of the best interests of the child in local and state policies, as well as to promote coordinated action of authorities, including co-operation groups. The Council was established in 2017 and its tasks and composition have been approved by the Minister of Welfare. Regulations of the Council list members’ representatives from 25 institutions and NGOs. This presents a promising practice to strengthen the co-operation between various stakeholders at national and municipal levels. Unfortunately, the frequency of the Council’s meetings (one meeting in 2022, one in 2021, two in 2022) prevents it from unleashing its full potential and meaningfully contribute to the work on children’s rights. The recent changes in the Council’s structure (e.g., creation of thematic working groups) could present an opportunity to improve its functioning. Looking ahead it would also be important to overcome role fragmentation at the policy level among different stakeholders involved in child protection, ensure adequacy of resources to support its activities and programmes, as well as overcoming resistance to change by some stakeholders involved in child protection.

Children’s rights co-operation groups in municipalities

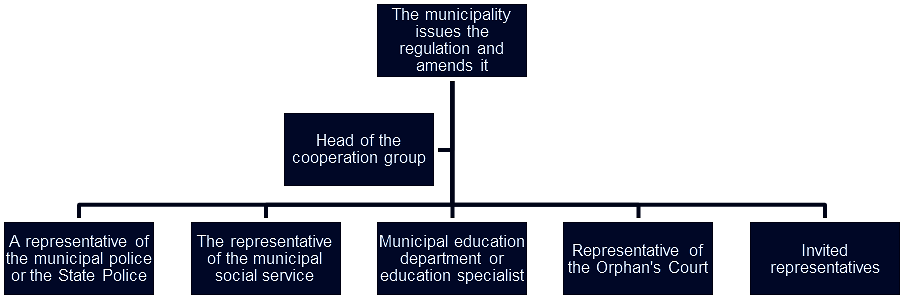

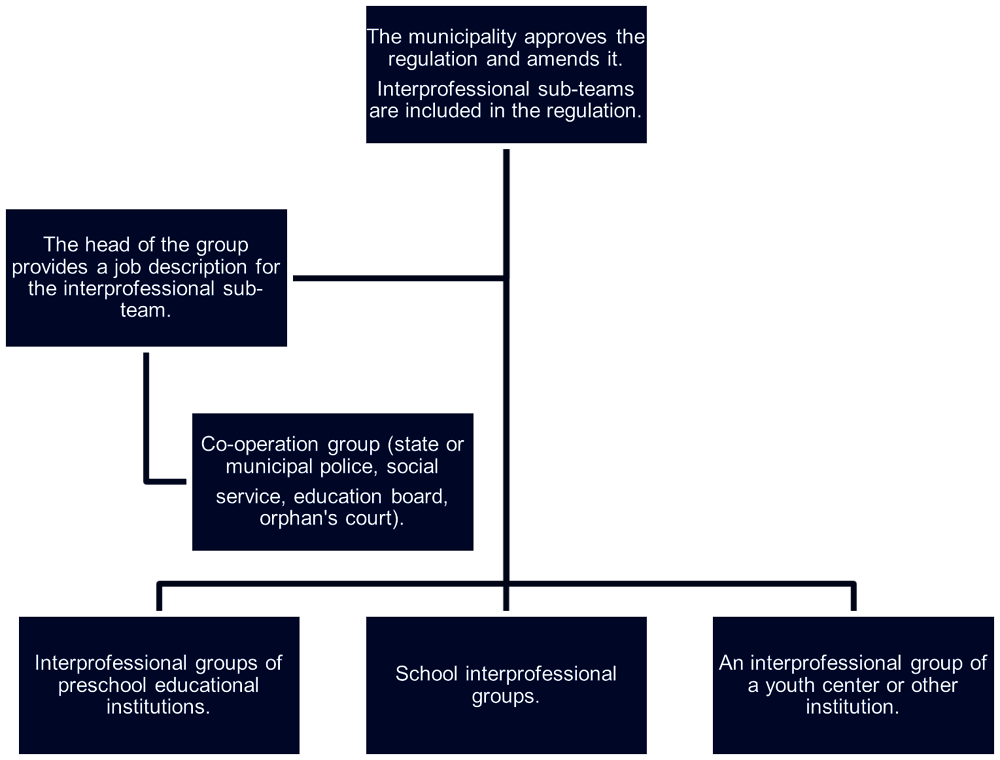

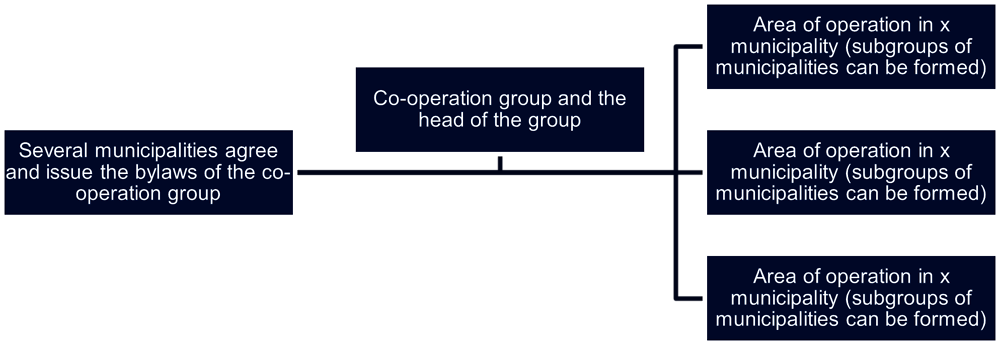

Given that most services and assistance are provided at the municipal level, the Children’s Rights Co-operation Groups (CRCGs) play a crucial role for advocating for children’s rights. These groups are consultative collegial institutions established by the local government and it operates within the administrative territory of the relevant county or city. The CRCGs operate in 42 municipalities as of 2021 in accordance with the regulations issued by the municipal council. Several co-operation groups may be established in one county or city. Alternatively, several local governments may establish one joint co-operation group. Therefore, three different operational models of the Group are possible:

one Co-operation Group in one municipality;

several Co-operation Groups of different levels in one municipality, among which the division of responsibilities is determined by the regulation of a municipal council;

several local governments have agreed on the establishment of one inter-institutional Co-operation Group, which is responsible for the protection of children’s rights in several local governments (Litvins and Kronberga, 2021[39]).

The established members of the children’s rights groups are municipal police (or State Police if the municipality has no municipal police), social service office, municipal education board or education specialist, the Orphan’s and Custody Court. Other representatives can be invited from educational institutions, childcare institutions, places of imprisonment, municipal pedagogical medical commission, municipal administrative commission, State Probation Service, State Police, or NGOs. For the examination of individual cases, the CRCG may invite other specialists or to examine individual cases or ask them to provide specific information related to cases.

Several municipalities have agreed on the establishment of one inter-institutional co-operation group, whose mandate involves the protection of children's rights in several municipalities.

Figure 3.1. Co-operation group in one municipality

Source: Author’s elaboration based on (Litvins and Kronberga, 2021[39]). Inter-institutional co-operation for the protection of children's rights in municipalities, https://juristavards.lv/wwwraksti/JV/BIBLIOTEKA/PRAKSES_MATERIALI/SARPINST_SADARBIBA_BERNU_TIESIBU_AIZSARDZIBAI_2021.PDF

Figure 3.2. Co-operation groups at different levels in one municipality

Note: The division of responsibilities is specified in the relevant regulations.

Source: Author’s elaboration based on (Litvins and Kronberga, 2021[39]). Inter-institutional co-operation for the protection of children's rights in municipalities, https://juristavards.lv/wwwraksti/JV/BIBLIOTEKA/PRAKSES_MATERIALI/SARPINST_SADARBIBA_BERNU_TIESIBU_AIZSARDZIBAI_2021.PDF

Figure 3.3. Inter-institutional co-operation group

Source: Author’s elaboration based on (Litvins and Kronberga, 2021[39]). Inter-institutional co-operation for the protection of children's rights in municipalities, https://juristavards.lv/wwwraksti/JV/BIBLIOTEKA/PRAKSES_MATERIALI/SARPINST_SADARBIBA_BERNU_TIESIBU_AIZSARDZIBAI_2021.PDF

The main task of the CRCG is to examine individual cases related to possible violations of the rights of the child, if prompt action and co-operation of several institutions are required, and/or if the situation cannot be resolved within one institution or has not been resolved in a long period of time. The Group agrees on the measures to be taken by each represented institution in line with their respective competence.

The Group also analyses the situation in the field of protection of children's rights and provides the municipality with proposals for the development of a programme for the protection of children's rights in the county or state city, including the necessary measures to improve the system of institutional co-operation and co-ordination. The group also submits proposals to the Ministry of Welfare for the improvement of regulations and co-operation in the field of protection of children's rights.

Box 3.15. Guidelines for municipalities in the protection of children’s rights

To assist municipalities in organising the work of the Co-operation Groups, the State Inspectorate has published a document entitled “Guidelines for Municipalities in the Protection of Children’s Rights”, which encompasses the following:

Co-operation groups are created by local governments to deal with particularly difficult cases and provide proposals for ensuring the rights and interests of children at the local and national levels.

The municipal council, when developing the regulations of the co-operation group, should include information on the composition, competence, rights of the co-operation group, as well as on the work organisation including the procedure for the exchange of information between the members of the co-operation group. It should also indicate how matters are brought up during meetings. The council must determine the structural unit or employee responsible for the material and technical support for the co-operation group’s work.

The frequency at which the co-operation group reports on its work to the municipal council should be specified in the regulations governing the municipalities and local governments.

If the municipal council forms several co-operation groups, then the regulations of each co-operation group must determine its own jurisdiction.

Additionally, the State Inspectorate has published methodological recommendations entitled “Competence of educational institutions, social services, the Orphan’s and Custody Courts and other institutions in inter-institutional co-operation, performing preventive work and solving cases of violence against children”, which provide detailed recommendations in the form of situation descriptions on how institutions should co-operate in solving cases related to violations of children’s rights.

When dealing with issues of protection of the rights of a child who falls victim to violence, it is necessary to take into account the following aspects:

immediate needs of the child, as well as long-term needs (need for safety, care and special assistance),

the need to share useful information that helps ensure the immediate and permanent safety of the child,

there is one specialist who manages the work with the specific case and coordinates co-operation, inter-institutional assessment and research planning best meets the interests of the child and ensures availability of resources.

Source: (State Inspectorate for the Protection of Children’s Rights, n.d.[40]), Guidelines for Municipalities in the Protection of Children’s Rights, https://www.cilvektiesibugids.lv/lv/temas/gimene/berns/berns-vina-aizsardziba-valsts-proceduras.

A study conducted in 2019 found that the establishment of the Co-operation Groups had been successful and that the groups had potential to develop further (Kronberga et al., 2019[41]). Various stakeholders repeatedly mentioned the CRCG during the interviews. While they are still fairly new and developing, they appear to offer a sound basis for further strengthening co-ordination and co-operation. To reach their full potential however, it would be important to ensure sufficient resources, especially in smaller municipalities, overcome role fragmentation among different stakeholders (e.g., multiple government agencies and non-governmental organisations), address cultural attitudes towards child protection and the role of children and young people in decision-making processes, overcome participation barriers for children and young people (e.g., language barriers, lack of transportation, lack of resources or support for participation, and stigma or discrimination), as well as put in place effective data protection mechanisms to address privacy concerns. This will help ensure sound functioning of CRCGs with a view to promoting rights of children and young people in municipalities.

3.3.2. Reporting, referrals and information sharing

Reporting and referral obligations

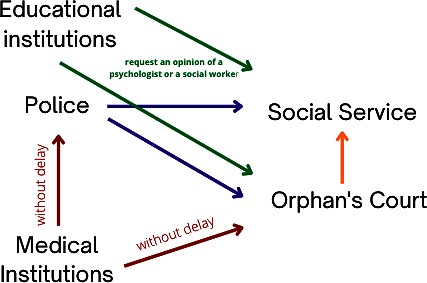

The LPCR (LIKUMI, 1998[12]) states that the child her/himself and other persons have the right to seek assistance from state and local government institutions and these institutions are obliged to take action in order to prevent abuse or provide support and assistance to the child. The heads of childcare, educational, health care, and similar institutions have an obligation to determine the procedures for submitting and processing children's complaints and make those mechanisms and procedures known and accessible to children. Both the Ombud’s Office and the State Inspectorate report to the responsible authorities by forwarding official information. The State Inspectorate is legally obligated to ask the child if s/he agrees that the information will be forwarded to other institutions. Sometimes, they have very little information and need to use other means of acquiring information if it is a serious case (e.g., speaking with school, social service). The relevant institutions must then visit the family or perform other tasks and then report back to the State Inspectorate. The Law requires institutions to report violation of children’s rights and refer cases to each other. Under the law, the four main identified entry points are: police, medical institutions, educational institutions, and The Orphan’s and Custody Courts. At the national level, all state institutions are responsible for reporting the implementation of the UNCRC to the Ombuds Office and to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Figure 3.4 below provides an overview of the reporting pathways available for children in Latvia.

Figure 3.4. Reporting pathways available to children in the Latvian justice system

Source: (LIKUMI, 1998[3]), Law on Protection of Children’s Rights, and Latvian civil law, https://likumi.lv/ta/en/en/id/49096-law-on-the-protection-of-the-childrens-rights.