This chapter describes and assesses urban-rural linkages in Poland. First it provides a conceptual framework, reviewing the dimensions of urban-rural linkages, their determinants and their implications for territorial development and well-being. Then it describes the main factors and trends affecting urban-rural linkages in Poland, as well as key characteristics of urban and rural areas and urbanisation patterns in the country. Next, the chapter examines urban-rural labour market linkages within Functional Urban Areas and between Functional Urban Areas and the surrounding rural areas. The final section analyses the effects of urban-rural linkages on demographic growth in Polish municipalities.

Urban-Rural Linkages in Poland

1. Diagnosis of urban-rural linkages in Poland

Abstract

Key findings

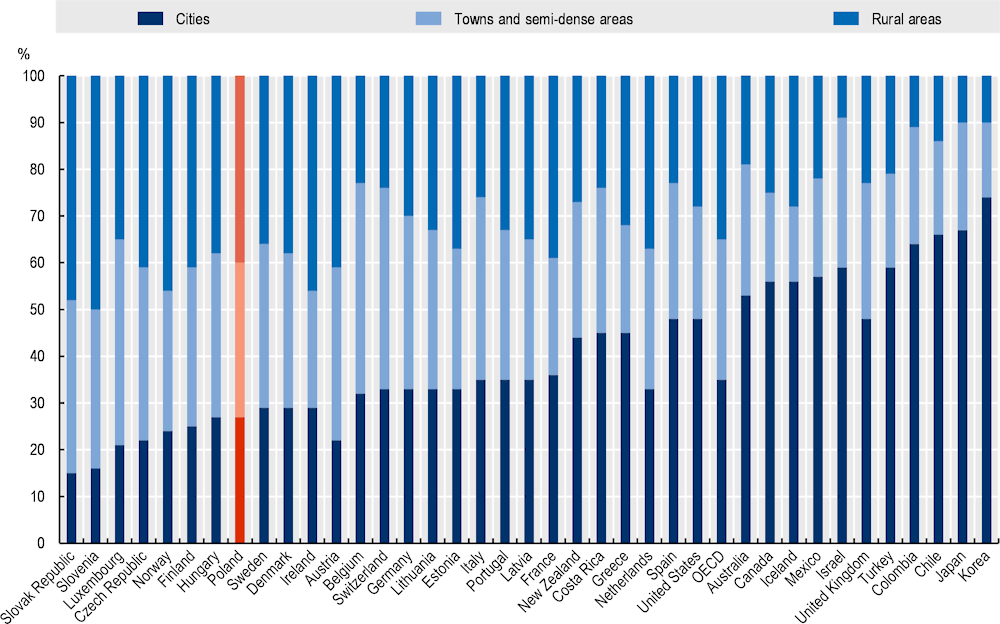

Poland has a larger share of population living in low- and medium- density areas than the OECD average (72% vs. the OECD average of 50%), and a smaller share in cities (28% vs. the OECD average of 50%) than OECD countries. Additionally, Functional urban areas (FUAs) – that is, core cities and their commuting zones – include a strong rural component, too: in 2019, 37% of FUA residents lived in municipalities that can either be classified as “towns and semi-dense areas” (15%) or “rural areas” (22%).

FUAs in Poland are also more dispersed than the OECD average: while across the OECD, only an average of 25% of FUA residents live in the commuting zones, in Poland the share is much larger, 43%, indicating the need and the potential for strong functional linkages.

Labour market linkages show that, while settlements are dispersed across urban and rural areas, cities are highly attractive for commuters (while rural areas have fewer job opportunities), and two-thirds of commuting flows are directed towards FUAs. In addition, in some FUAs there is a high level of diffusion of employment, also involving peri-urban and rural municipalities in commuting zones. However, while most large FUAs attract commuters, many small and medium-sized FUAs show a negative commuting balance. Additionally, in Poland, 9.2 million people live in FUA catchment areas (areas with a considerable high degree of commuting towards FUAs) Municipalities that are outside FUAs but in FUA catchment areas) have strong linkages with FUAs as well.

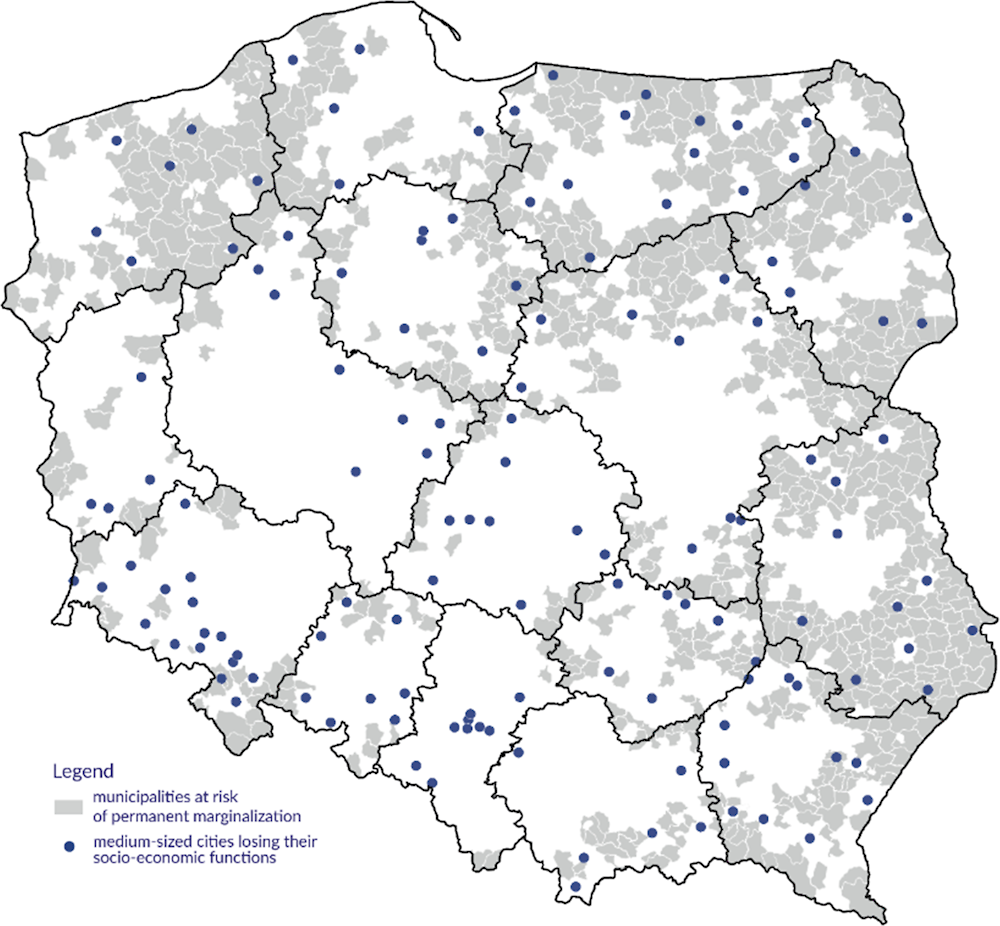

Demographic shrinking is challenging Polish urban and rural areas and their linkages. However, there are striking territorial differences: while few large cities are growing, three quarters of Polish FUAs are losing residents. Almost every mid- and small- sized FUA has lost residents over the last decade. While population in suburban areas and rural areas close to cities is increasing, rural areas far away from cities show a marked decline. Polish FUAs are also ageing, especially in core cities, while suburban areas have a younger age structure. This will lead to changing needs for public services.

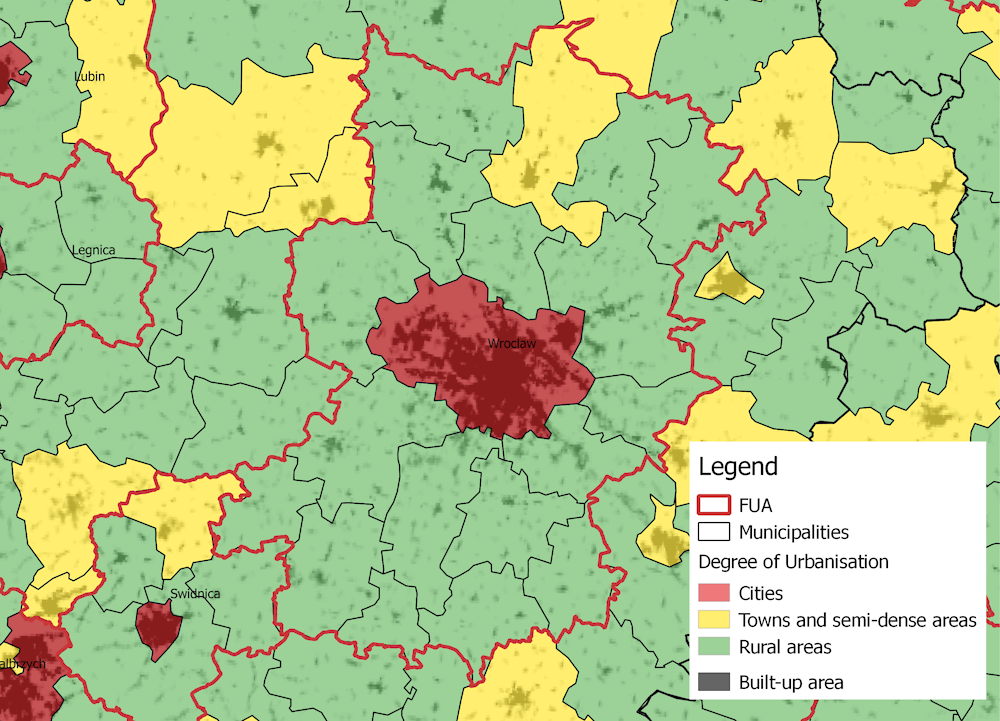

While Polish territories generally have good levels of physical and digital accessibility, there are large disparities among FUAs and large urban-rural gaps as well. Some key supra-local services are concentrated in large cities, and public transport outside FUAs is very limited. This highlights that infrastructures and connectivity are crucial factors to exploit the potential of mutual relationships between FUAs and their surrounding areas.

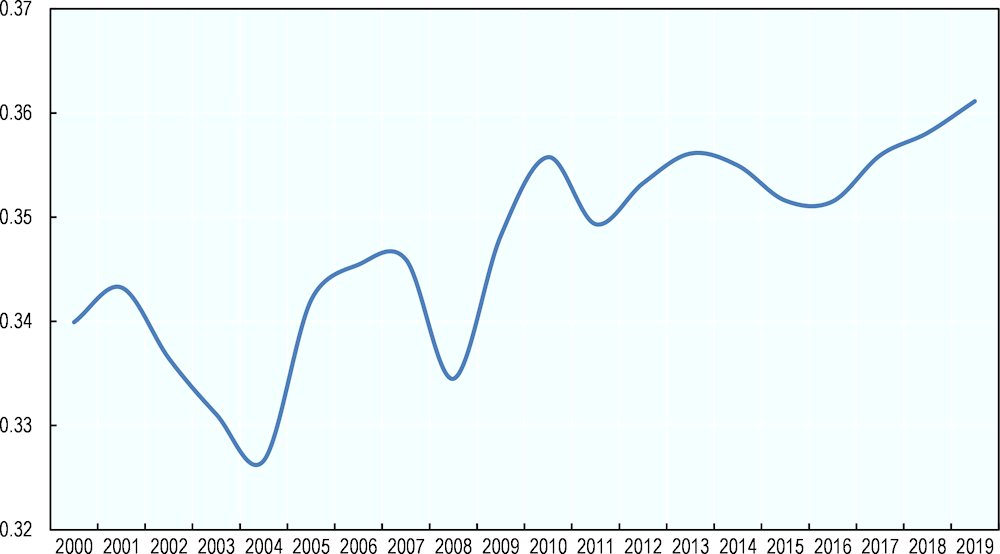

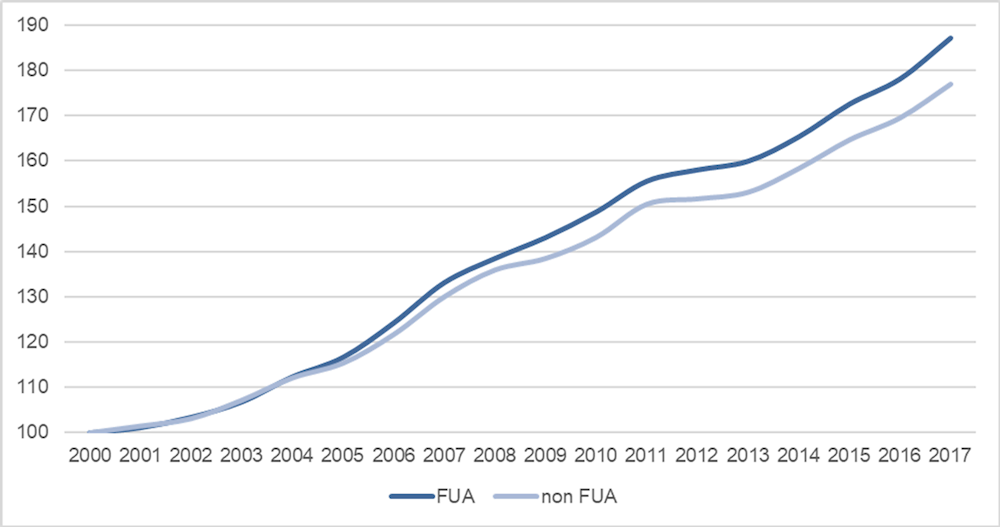

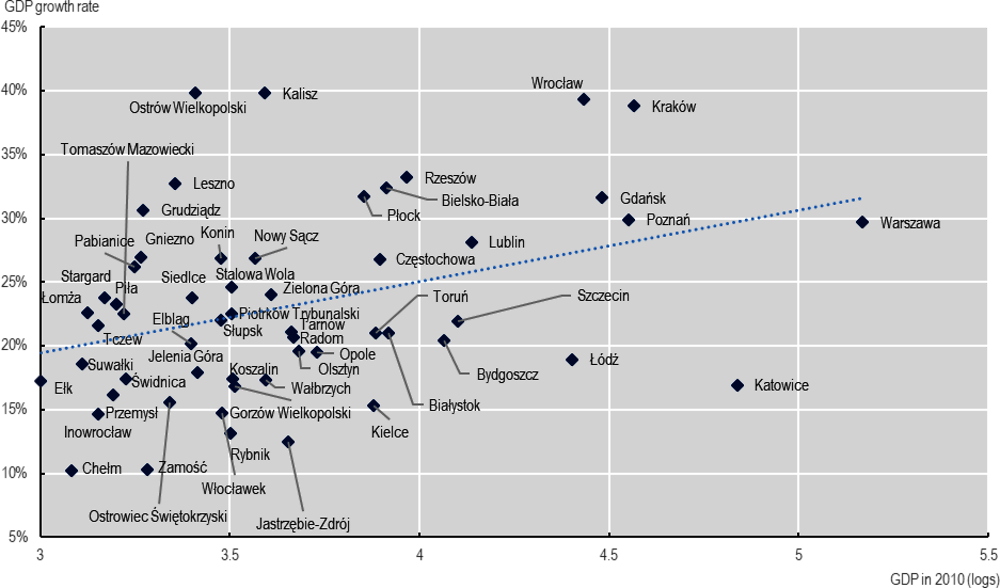

While Poland experienced a sustained economic growth, economic and social trends in Poland indicate increasing disparities in GDP per capita between FUAs and the rest of the country. Cities also strongly differ in terms of economic growth, and many smaller urban centres have experienced weak performance and loss of economic functions.

A deeper analysis on the determinants of population dynamics in Polish municipalities indicate that a series of demographic, economic and social drivers have led population growth (or decline) in the last two decades. At the same time, some variables connected to urban rural linkages, such as being part of a commuting zone of a FUA and being a rural area within a FUA played a role in population growth. Additionally, increased suburbanisation has been a driver for municipal growth, while time distance to core cities curbed increase in residents. However, being part of a FUA catchment area does not yield higher growth, indicating that agglomeration advantages end at the FUA boundaries.

Introduction

Urban and rural areas in Poland and across OECD countries are interlinked economically, socially and environmentally. Those links are critical in the context of territorial development, as they can potentially be leveraged to address long-term challenges such as poverty and limited water supplies, or to improve access to food or protect the environment. Urban or rural areas offer their residents different lifestyles, opportunities, and levels of access to services and products, but their development is interconnected. This is true from spatial perspective – in the flows of people, capital, goods and information – and in sectors such as agriculture, manufacturing and services (IIED, 2018[1]).

Poland has been going through a process of suburbanisation and sprawl over the last two decades, making it even more important to co-ordinate planning and service delivery across urban and rural areas. While in the past there was a marked urban-rural dichotomy, in Poland and worldwide, the distinctions have blurred over time, with larger areas, including rural settlements, becoming part of cities’ commuting zones.1 Those larger interconnected areas are known as functional urban areas. The OECD (2011[2]) has previously noted significant social and economic inequalities within urban areas, however, as well as that higher levels of poverty in small and medium-sized cities and deeper poverty in larger cities, despite they are the engines of national economic growth. A more integrated approach to the development of urban and rural areas could potentially help reduce socio-economic disparities while ensuring more effective land use and providing more equitable access to services and opportunities.

In recent years, the Polish government has sought to promote greater territorial cohesion through the Strategy for Responsible Development (2017), the National Strategy for Regional Development 2030 (2019) and the ongoing revision of the National Urban Policy. In order to fully realise the benefits of urban-rural linkages for development and well-being, Poland needs strategic design, improved capacity to co‑ordinate strategies across sectors and territories, and the right institutional frameworks and incentives to create synergies between urban and rural areas.

Russia’s war on Ukraine has also put significant new pressures on Poland, which shares a 500 km border with Ukraine. Between February and May 2022, Poland received more than 3.5 million refugees (UNHCR, 2022[3]), more than half of total Ukrainian refugee flows. Some refugees may move on to other countries or return home, but the UN Refugee Agency has predicted that 4.3 million refugees will enter and 2.6 million will remain by December 2022. Roughly half the refugees are adult women, and a majority of the rest are children. Most refugees have temporarily settled in large cities. For instance, as of early May 2022, about 300 000 were in Warszawa and 150 000 in Krakow, increasing the cities’ population by 17% and 20%, respectively (Urbańska, 2022[4]).

Polish cities are making great efforts to welcome refugees, employing 200 Ukrainian teachers in Warszawa schools, for instance, to help the children to integrate (UNHCR, 2022[5]). The large influx of refugees has put significant pressure on public services, however, as cities of all sizes, towns and villages work to provide temporary accommodations and basic services in the near term and to integrate refugees who settle more permanently. Pressure is particularly great on nurseries, kindergartens and schools. As of early May 2022, 7% of pupils in primary schools in Warsaw were Ukrainians (Urbańska, 2022[4]). The health care system and social services also face significant increases in demand.

Strengthening urban-rural linkages and fostering more integrated development could help Poland address its near-term challenges and improve economic opportunities and human well-being in the long term. This chapter provides a foundation for exploring that potential. It provides a conceptual framework for understanding urban-rural linkages, describing their multiple dimensions. It describes the methodology applied throughout this study. Next, , it reviews the characteristics of urban-rural linkages in Poland and current trends, applying two OECD approaches: analysis of functional urban areas (FUAs), and the Degree of Urbanisation method. It then focuses on the socio-economic linkages conceptualised and measured across the Polish territories in terms of commuting flows – one of the most relevant and direct measures of interrelationships across space. The, the chapter summarises the main features and trends affecting urban-rural linkages in FUAs in Poland, such as the demographic trends and the main features on physical and digital spatial accessibility. It focuses on how urban-rural linkages may affect the growth of municipalities in Poland. Finally, it summarises the main findings, identifies the limitations of the analysis, and provides directions for future research.

A new conceptual framework on urban-rural linkages

Urban-rural linkages are multi-dimensional

There are different perspectives on urban-rural linkages, but they are generally understood to be a multi-dimensional set of relationships, involving flows of people, goods, services, finances and much more across space, in both directions. Box 1.1 provides examples of how the OECD, the European Union (EU) and United Nations (UN) agencies have described those linkages.

Box 1.1. Defining urban-rural linkages: Examples from the OECD, the EU and the UN

The OECD Principles on Urban Policy and the OECD Principles on Rural Policy define linkages between urban and rural areas as “flows of goods, people, information, finance, waste, information, social relations across space, linking rural and urban areas” (OECD, 2019, p. 2[6]). They note that they “often cross traditional administrative boundaries, are based on where people work and live, are not limited to city-centred local labour market flows but rather include bi-directional relationships,” and they can “reinforce rural economic diversification.”

The OECD (2013[7]) had previously defined urban-rural linkages as “connections between urban and rural areas, along a functional dimension and within functional regions (the latter defined as spaces in which a specific territorial interdependence of function occurs and may need to be governed)”. The main categories were identified as “demographic linkages, economic transactions and innovation activity, delivery of public services, exchange in amenities and environmental goods, multi-level governance interactions”.

The EU Handbook of Sustainable Urban Development Strategies (EC, 2020[8]) describes urban-rural linkages as “the complex set of bi-directional links (e.g. demographic flows, labour market flows, public service provision, mobility, environmental and cultural services, leisure assets, etc.) that connect places (in a space where urban and rural dimensions are physically and/or functionally integrated), blurring the distinction between urban and rural, and cross traditional administrative boundaries.”

The European Committee of the Regions (2019[9]), meanwhile, notes that metropolitan regions have spill-over effects on their surrounding areas, in the form of societal links (migration, commuting, central facilities), economic links (agglomeration advantages, markets, consumers) and environmental links (space and land take, air and climate, water and waste).

The UN-Habitat Framework for Action to Advance Integrated Territorial Development highlights the “reciprocal and repetitive flow of people, goods and financial and environmental services (defining urban-rural linkages) between specific rural, peri-urban and urban locations” (UN-Habitat, 2019, p. 1[10]). The UN-Habitat Urban Policy Platform (UN-Habitat, n.d.[11]), which focuses mainly on developing countries, describes provides a more detailed and multi-faceted description:

“Urban-rural linkages touch on a broad variety of thematic areas ranging from urban and territorial planning, strengthening small and intermediate towns, from enabling spatial flows of people, products, services and information to fostering food security systems as well as touching mobility and migration, reducing the environmental impact in urban-rural convergences, developing legislation and governance structures and promoting inclusive financial investments among others.” The UN-Habitat Urban Policy Platform also notes that partnerships between urban and rural actors “are crucial for a transformative agenda”.

Source: OECD (2019[6]), Megatrends: Building Better Futures for Regions, Cities and Rural Areas, https://www.oecd.org/regional/ministerial/documents/urban-rural-Principles.pdf; OECD (2013[7]), Rural-Urban Partnerships: An Integrated Approach to Economic Development, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264204812-en; EC (2020[8]), Handbook of Sustainable Urban Development Strategies, https://urban.jrc.ec.europa.eu/urbanstrategies/full-report#the-chapter; UN-Habitat (n.d.[11]), Urban-Rural Linkages, https://urbanpolicyplatform.org/urban-rural-linkages/; UN-Habitat (2019[10]), Urban-Rural Linkages: Guiding Principles, https://unhabitat.org/sites/default/files/2020/03/url-gp-1.pdf; European Committee of the Regions (2019[9]), The Impacts of Metropolitan Regions on their Surrounding Areas, http://dx.doi.org/10.2863/35077.

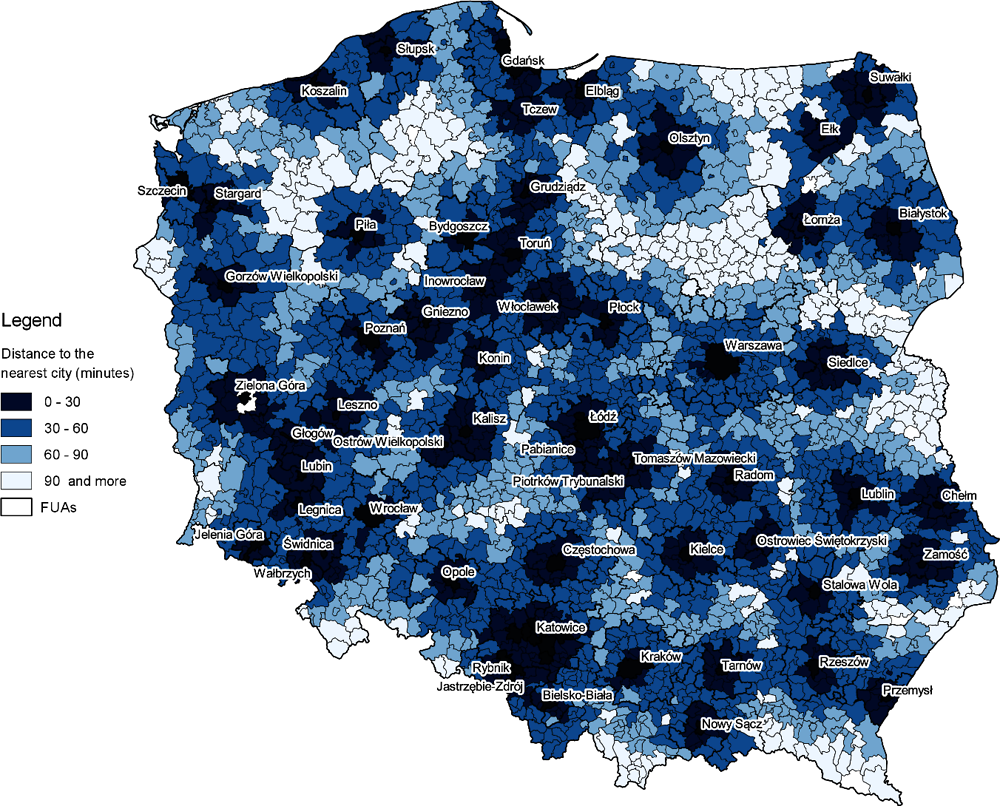

As summarised in Figure 1.1, the main linkages between urban and rural areas are:

Population, job opportunities and commuting: People travel daily between urban and rural areas as they commute to and from work or school. They also relocate from one to the other, driven by personal choices and by the location of jobs and other economic opportunities. At the population scale, these movements are labelled as rural-urban migration (urbanisation) or urban-rural migration (counter-urbanisation) – which can be directed towards suburbs (suburbanisation).

Investments and economic transactions: The structure of local markets and value chains and the location choices made by firms and institutions shape the economic relationships between urban and rural areas. There can be productive complementarities in certain industries (such as in food production), as well as agglomeration economies associated with urban centres, which attract business clusters and can spill overs into rural areas. For instance, firms may invest in rural areas to get access to the markets, services and opportunities offered by nearby urban centres.

Services provision: Cities provide “central” infrastructure and services for the areas in which they are situated, such as transport, education, healthcare, and recreational and cultural facilities. The strength of urban-rural linkages is determined by how accessible urban services are to rural residents, their quality and the type of public services available. While local services, such as primary schools, are usually easily accessible across space, supra-local services, such as universities, may be concentrated in a few larger cities. Intermediary cities and towns can play a role in making services better and more accessible.

Environmental goods and amenities: There are two main aspects to these linkages. First, rural areas typically supply ecosystem services to urban areas, including improved air quality, water supplies, wastewater disposal and biodiversity (OECD, 2013[7]). Second, rural areas provide environmental amenities, such as parks, lakes or hiking trails. The strength of the linkages is determined by the degree of accessibility of urban population to rural environmental goods and amenities and to the quality of the corresponding services.

Governance interactions and partnerships: Local governments and other stakeholders interact with one another, affecting territorial governance and, potentially, all the other dimensions listed above. Urban-rural partnerships are mechanisms of co-operation among local governments that manage and govern urban-rural linkages to reach common goals, improve well-being, and ensure sustainable relationships. Chapter 2 provides an in-depth assessment of urban-rural partnerships.

Figure 1.1. Urban-rural linkages and their affecting factors

Source: Adapted from OECD (2013[7]), Rural‑Urban Partnerships: An Integrated Approach to Economic Development, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264204812-en.

Some key features of urban-rural linkages may serve as a basis for assessing them in specific contexts. In particular, urban-rural linkages:

Encompass multiple dimensions of development and well-being, requiring an integrated approach to promote them.

Go beyond administrative borders and refer to functional geographies, which are based on the places where people live and work.

Apply to different territorial structures and sizes – for instance, large metropolitan areas and their surrounding areas, polycentric regions made up of small and medium-sized cities, less populated regions with market towns, etc.

Tend to blur the (traditional) distinction between urban and rural, and call for an approach tackling the urban-rural continuum.

Can be one-way (urban-to-rural OR rural-to-urban) or bi-directional (urban-to-rural AND rural-to-urban); bi-directional linkages are also described as urban-rural interdependencies.

Can have spill-over effects on wider regional development and well-being.

Call for multi-level and multi-stakeholder partnerships to fully exploit their potential.

Different types of urban-rural linkages can also be interdependent. The agglomeration benefits related to larger labour markets, for instance, can increase the attractiveness of cities, thus incentivising urbanisation. However, this can drive up housing costs, leading people to seek more affordable options in suburbs and rural areas. That, in turn, results in longer commutes and the loss of farmland, open space and environmental amenities in rural areas (especially when they are close to cities). Institutional mechanisms of co-operation can help to ensure more sustainable development. In some cases, municipal mergers may be appropriate to restructure the distribution of tasks and costs burdens between the levels of government (see Chapter 3). Therefore, the multi-dimensional nature of urban-rural linkages calls for a systemic view rather than a sector-specific approach. A multi-dimensional perspective is also crucial for ensuring the well-being of residents across the urban-rural continuum.

Urban-rural linkages are shaped by – and, in turn, affect – the structure of settlements, people’s well-being and governance

The extent to which urban and rural areas can benefit from their interlinkages depends on several factors (OECD, 2013[7]):

The spatial/settlement structure – for example, the size of the urban area and its accessibility.

Well-being – the material conditions, such as income and wealth, jobs and housing, and other factors, such as health, knowledge and skills, environmental quality and safety, that affect the quality of life, and which are also related to the economic structure of cities and surrounding rural areas (OECD, 2022[12]).

The governance structure – how urban and rural territories are managed, and the extent to which there are incentives for inter-municipal cooperation that can boost urban-rural synergies.

Urban-rural-linkages, in turn, can affect all these conditions. For instance, rural residents who can access more services and opportunities will have a better quality of life, and co-operation among local governments can foster a more balanced spatial structure and improve overall conditions.

The extent of urban-rural linkages, their quality and their outcomes can vary considerably. Urban-rural linkages in large metropolitan areas (which may include small and medium-sized cities and towns) are often stronger than in regions with only smaller cities, which also may provide fewer and lower-quality services. Core cities in large metropolitan areas are regional (and even national) economic engines, linking territories with international and global markets and opportunities. They also produce larger spill-over effects, while small and medium-sized cities and towns play more limited and more local roles (OECD/EC-JRC, 2021[13]). This heterogeneity is particularly evident in Poland, which has everything from large metropolitan areas, to polycentric regions, to sparsely populated territories2 (Stanny, Komorowski and Rosner, 2021[14]; Kurek, Wójtowicz and Gałka, 2020[15]). Activities in Poland are increasingly concentrated in the largest urban areas.

The physical distance between urban and rural areas affects the existence, the magnitude and the direction of urban-rural linkages. However, the interaction between urban and rural areas can increasingly be “virtual”, implying digital flows rather than physical flows. The megatrend of digitalisation of the service provision and the changes in the organisation of work, including the increasing role of remote working, which have been boosted by the COVID-19 pandemic, give a key role to digital connections across space. Turned into urban-rural linkages, digital accessibility is a major driver of “virtual interaction”.

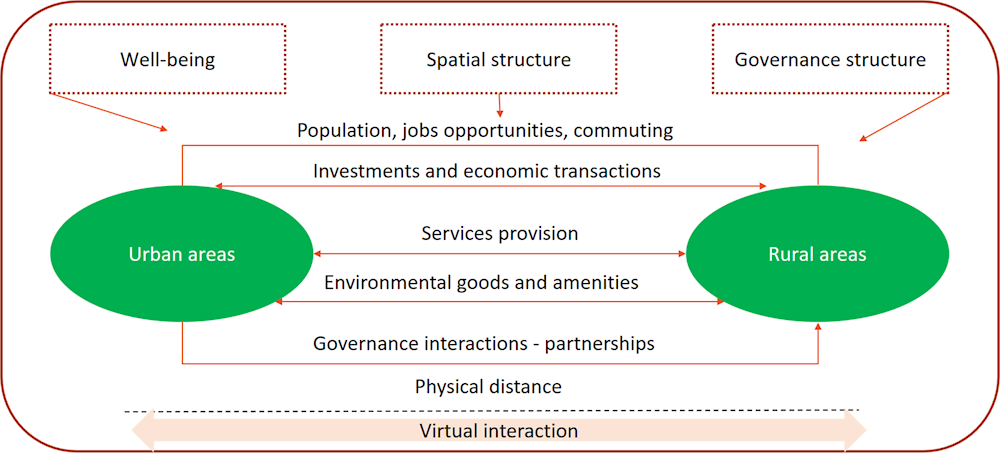

Stronger linkages between urban and rural areas can improve economic opportunities and well-being for citizens

Poland performs well on some aspects of well-being, such as education and skills, relative to other OECD countries. However, it has potential to improve some key dimensions of well-being, as measured by the OECD Better Life Index (Box 1.2). Disparities across regions are also increasing (OECD, 2020, pp. 16-17[16]); as shown in Figure 1.2, there are large gaps in jobs, incomes and digital accessibility, for instance (OECD, 2020[17]).

Disparities are also characterising municipalities, indicating low cohesion at the local level (Rosner and Stanny, 2017[18]; Gospodarowicz and Chmieliński, 2021[19]). In this context, better urban-rural linkages can contribute to improving well-being and reducing spatial inequalities and polarisation. For instance:

Better urban-rural linkages can help improve access to jobs and educational opportunities in all territories through physical and digital infrastructure.

Good access to medical services can help improve health outcomes.

Better public transport service can help improve work-life balance (by making commutes shorter and/or less stressful).

Box 1.2. Key elements of national well-being in Poland, based on OECD Better Life Index and Regional Well-being

Housing: Households in Poland spend on average 21% of their gross adjusted disposable income on housing, slightly above the OECD average of 20%.

Income: The average household net adjusted disposable income per capita is USD 23 675 per year, lower than the OECD average of USD 30 490. There is also a marked difference between the Warszawa region, which is above the OECD regional average level, and all other Polish TL2 regions,1 which are below the OECD regional average level.

Jobs: 69% of the working-age population aged 15 to 64 has a paid job, higher than the OECD average of 66%. However, there are large disparities, in particular between the Warszawa region, which is among the top 10% OECD regions, and the other Polish regions, which are all below the OECD median.

Community: 94% of people believe that they know someone they could rely on in time of need, more than the OECD average of 91%. The indicator shows a marked regional variation: while Pomorskie is among the top OECD 20% regions, four Polish TL2 regions are among the bottom OECD 20% regions.

Civic engagement: 68% of registered voters participated in the most recent election (2020), slightly lower than the OECD average of 69%.

Education: 93% of adults aged 25-64 have completed upper secondary education, much higher than the OECD average of 79% and one of the highest rates in the OECD. The average student in Poland scored 513 in reading literacy, maths and sciences, above the OECD average of 488. However, there are regional disparities in the quality of education.

Environmental pollution: Poland ranks 39th out of 40 OECD member countries and key partners for its environmental quality. PM2.5 levels are 22.8 micrograms per cubic meter, higher than the OECD average of 14 micrograms per cubic meter and much higher than the annual guideline limit of 10 micrograms per cubic meter set by the World Health Organization.

Health: Life expectancy at birth in Poland stands at 78 years, two years below the OECD average of 81 years. 60% of people in Poland are reported to be in good health, well below the OECD average of 68%.

Life satisfaction: When asked to rate their general satisfaction with life on a scale from 0 to 10, the average grade given by citizens was 6.1, lower than the OECD average of 6.7.

Work-life balance: Full-time workers devote 61% of their day on average, or 14.7 hours, to personal care (eating, sleeping, etc.) and leisure (socialising with friends and family, hobbies, games, computer and television use, etc.) – less than the OECD average of 15 hours.

1. Within OECD countries, TL2 regions (or “large regions”) represent the first administrative tier of subnational government. For European countries, this classification is largely consistent with the Eurostat NUTS 2016 (OECD, 2021[22]).

Source: OECD (2021[20]), “Better Life Index”, https://doi.org/10.1787/data-00823-en (accessed on 9 December 2021); OECD (2020[21]), OECD Regional Well-Being, https://www.oecdregionalwellbeing.org/ accessed on 25 March 2022.

Figure 1.2. Well-being regional gap, Poland

Note: Relative ranking of the regions with the best and worst outcomes on the 11 dimensions of well-being, with respect to all 440 OECD regions. The dimensions are ordered by the size of regional disparities within Poland. Data refer to OECD TL2 regions (or “large regions”), which are equivalent to the Eurostat NUTS 2016 (OECD, 2021[22]; Statistics Poland, 2021[23]).

Source: OECD (2020[17]), OECD Regions and Cities at a Glance 2020, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/959d5ba0-en.

Partnerships can foster beneficial urban-rural linkages

The OECD has recognised the relevance of urban-rural partnerships to guide both urban and rural development. Principle 3 in the OECD Principles on Urban Policy and the OECD Principles on Rural Policy (OECD, 2019[6]) recommends the management of linkages between urban and rural areas to attain common goals (Box 1.3).

Box 1.3. What do the OECD Principles on Urban and Rural Policy say on urban-rural partnerships?

The OECD Principles on Rural Policy (Figure 1.3) and the OECD Principles on Urban Policy (Figure 1.4), launched in 2019, seek to support governments in achieving global agendas through future-proof regional development policies (OECD, 2019[6]). Both are based on the premise that place-based policies should deliver opportunities for urban and rural residents alike. They also follow the principle of subsidiarity and call for a sound multi-level governance system based on a clear allocation of roles and responsibilities, with co-ordination across levels of government and local and regional actors.

Figure 1.3. OECD Principles on Rural Policy

Figure 1.4. OECD Principles on Urban Policy

Each of the sets of principles includes one (No. 3) on the importance of supporting interdependencies and co-operation between urban and rural areas by:

Leveraging the spatial continuity and functional relationships between urban and rural areas to inform public investment and programme design.

Carrying out joint strategies and fostering win-win urban-rural partnerships, as appropriate, to promote an integrated development approach. Specific strategies to promote rural-urban partnerships include:

Aligning fiscal incentives to partnership goals.

Ensuring coordination incentives exist in spatial planning legislation.

Creating legal partnership forms: e.g., shared service agreements.

Source: OECD (2019[6]), Megatrends: Building Better Futures for Regions, Cities and Rural Areas, https://www.oecd.org/regional/ministerial/documents/urban-rural-Principles.pdf.

Those principles and the renewed OECD approach to urban-rural partnerships are the guiding framework for this report. Well-being is now at the centre of the OECD regional development policy, which feeds a renewed OECD approach to urban-rural partnerships that focuses on improving well-being, going beyond single objectives of increasing growth and income.

Urban-rural partnerships are thus analysed in this report following three dimensions of well-being:

Economic: Partnerships to boost specific economic activities (e.g. agriculture, industry, tourism), entrepreneurship, labour productivity, and transport and digital infrastructure.

Social: Partnerships to improve the provision and quality of education, health and other public services.

Environmental: Partnerships to enhance management of natural resources (e.g. water, forests, land), accelerate the transition to a circular economy (e.g. waste management) and help meet climate goals (reduce emissions).

Box 1.4. Urban-Rural partnerships: An integrated approach to economic development

Urban-rural (or rural-urban) partnerships are mechanisms of co-operation that manage and govern urban-rural linkages in a given territory to reach common goals, improve well-being, and ensure sustainable relationships. A distinctive characteristic of partnerships is that stakeholders from both urban and rural places are directly involved in the process to define the common set of objectives. Urban-rural partnerships reveal existing and potential complementarities in the territories, as they are driven and emerge based on the linkages between urban and rural areas (e.g. existing commuting of people among areas or shared natural resources or development goals). Therefore, partnerships allow different type of regions and areas to join efforts and resources to reach common objectives that cannot be achieved in isolation (or at least not as effectively).

In 2013, the OECD undertook a comprehensive examination of urban-rural partnerships in 11 countries and identified different types of partnerships and guidelines that facilitate them. Based on that study, OECD identified two types of partnerships:

Explicit partnerships treat urban-rural linkages as a core aspect of the partnership that is deliberately pursued through the issues identified, initiatives realised and/or stakeholders involved.

Implicit partnerships do not explicitly address urban-rural linkages, but rather aim to improve co-operation through a common local development objective, strategy or project that involves both urban and rural municipalities.

Partnerships can also vary based on whether they have delegated authority that is entrusted with the responsibility to act and with recognition of its ability to realise objectives, or instead collaborate informally, through loose networks.

Finally, there are single-purpose partnerships, which foster co-operation on a specific issue, and multiple-purpose partnerships, which have a wider scope of activities. While urban-rural partnerships can only be sustainable with a degree of organisational structure, several forms are possible, and the architecture of the structure will depend on the regional setting (OECD, 2013[7]).

Based on the analysis of urban-rural partnerships, this framework identifies five ways to strengthen and urban-rural partnerships and make them more effective:

1. Promote a better understanding of socio-economic conditions in urban and rural areas and foster a better integration between them.

2. Address territorial challenges with an approach based on functional linkages between urban and rural areas.

3. Encourage the integration of urban and rural policies by working towards a common national agenda.

4. Promote an enabling environment for urban-rural partnerships.

5. Clarify the partnership objectives and related measures to improve learning and facilitate the participation of key urban and rural actors.

The traditional view of urban-rural partnerships emerging from territorial proximity is being challenged by the disruptive effects of digitalisation. The proximity of urban and rural areas facilitates the exchange of resources and public services as well as the flow of workers and goods, which might lead to the development of partnerships.

Yet, the increasing adoption of virtual modes of communication allows for further exchange of services among municipalities that are distant from each other and do not share any boundary. For example, rural communities could access virtually education and health services provided by another far away city. Other types of urban-rural partnerships that go beyond proximity may include economic relationships between firms, tourism and other flows related to exchange in amenities (e.g. recreation), as well as some specific forms of institutional collaboration.

Source: OECD (2013[7]), Rural-Urban Partnerships: An Integrated Approach to Economic Development, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264204812-en.

Analytical tools and methods used in the report

This report takes an integrated approach to analysing urban-rural linkages in Poland, starting by identifying the multiple analytical and policy dimensions involved, the driving factors, and the implications for territorial development and people’s well-being. Such an assessment requires a full set of information and data on actual flows of people, goods, information, finance, energy and the like, including their direction. Such detailed information is not available for territories, including regions and cities, for most countries, including Poland. This study applies two complementary approaches, FUAs and the Degree of Urbanisation, to provide a new perspective on urbanisation in Poland, identify trends across different types of settlements, and compare Poland with other OECD countries.

The functional urban areas approach considers cities together with their surrounding commuting zones to capture the full extent of a city’s labour market

One of the most important types of flows between municipalities is daily commuting, which plays a key role in the territorial integration between the places where people live and the places where they work (Partridge, Ali and Olfert, 2010[24]). Travel-to-work commuting flows are therefore good proxies for the broader functional relationships between “core cities” and their surrounding communities, which typically include municipalities with both “urban” and “rural” characteristics.

Travel-to-work commuting flows are the basis of the identification of FUAs, the main tool used by OECD (and European) countries to link cities and their surrounding zones, including rural areas (Dijkstra, Poelman and Veneri, 2019[25]). Box 1.5 summarises the methodology to identify FUAs, which has been applied to 34 EU-OECD countries, including Poland.3 The use of FUAs applies a uniform definition and identification criteria across countries, allowing for international comparisons that are not possible with disparate national definitions. FUAs encompass the economic and functional extent of cities, based on people’s flows in local labour markets, so they can better capture agglomeration economies than administrative units. FUAs can therefore be powerful tools for analysing spatial, social and economic trends in territories.

FUAs can also be a good spatial scale for designing policies that are integrated and adapted to the places where people live and work, and for better linking cities and surrounding rural areas (OECD, 2020[17]), in line with the OECD Principles on Urban Policy and the OECD Principles on Rural Policy (OECD, 2019[6]). Principle 1 on Rural Policy, for instance, recommends that national policies “maximise the potential of all rural areas […] by adapting policy responses to different types of rural regions including rural areas inside functional urban areas (cities and their commuting zones), rural areas close to cities and rural remote areas” (OECD, 2019, p. 6[26]). Principle 2 of Urban Policy, meanwhile, advises governments to “adapt policy action to the place where people live and work, by […] supporting a functional urban area approach” (OECD, 2019, p. 14[27]).

Box 1.5. The EU-OECD definition and method to identify FUAs

The EU and the OECD jointly developed a methodology to define FUAs to provide a consistent and internationally comparable way to analyse urban-rural linkages. The identification of FUAs relies on three main data sources:

A residential population grid with the number of people per cell of 1 square kilometre and the share of land in each cell.

Digital boundaries of the local administrative units (LAUs).

Commuting flows between the local units and number of employed residents per local unit.

A FUA is identified in four steps:

1. Identify an urban centre (or high-density cluster): an area of contiguous high-density grid cells (at least 1 500 residents per km2) and a population of at least 50 000 inhabitants in contiguous cells. In Poland, the 2011 Geostat grid was used as the population grid (OECD, 2022[28]).

2. Identify a city (or densely populated area): this is made up of one or more local administrative units (LAUs, such as municipalities or other local authorities) with at least 50% of their population living in an urban centre. Gminas (equivalent to municipalities) are the geographic building blocks for Poland (Eurostat, 2022[29]). Note that the term “core city” is used in the remainder of the report to refer to cities, to make it easier to make it distinct it from other definitions of cities.

3. Identify a commuting zone: this is a set of contiguous local units that have at least 15% of their employed residents working in the core of the FUA.

4. A FUA is the combination of the core with its commuting zone.

The full process for identifying FUAs is described in detail in Dijkstra, Poelman and Veneri: (2019[25]).

Source: OECD (2022[28]), Functional Urban Areas by Country, https://www.oecd.org/regional/regional-statistics/functional-urban-areas.htm; Eurostat (2022[29]), Local Administrative Units (LAU), https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/nuts/local-administrative-units; Dijkstra, L., H. Poelman and P. Veneri (2019[25]), “The EU-OECD definition of a functional urban area”, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/d58cb34d-en.

The use of FUAs in this study is consistent with previous OECD research focused on Poland (OECD, 2021[30]; 2018[31]) and in comparisons across OECD countries (OECD, 2020[17]). It is important to stress again that the EU-OECD definition of FUAs adopts a statistical approach that is likely to differ from national definitions, such as those used in local strategies in Poland (Kurek, Wójtowicz and Gałka, 2020[15]). The value of this approach is that it makes it possible to understand how Poland compares with other countries.

The Degree of Urbanisation captures the continuum between urban and rural areas, a more nuanced perspective than the traditional urban-rural dichotomy

In order to define areas as urban or rural, this study applies the Degree of Urbanisation, a novel method to identify “cities”, “towns and semi-dense areas” and “rural areas” based on population size and density (OECD/European Commission, 2020[32]) (Box 1.6). This method has several advantages:

It goes beyond the simplistic urban-rural dichotomy, capturing the entire urban-rural continuum;

It follows the internationally agreed principles specified in the Best Practice Guidelines for Developing International Statistical Classifications (UN Statistics Division, 2013[33]).

Because it is based on a statistical grid, it avoids the statistical distortions caused by the different sizes of administrative units, facilitating international comparisons.

It is based on the spatial concentration of people, which is a direct measure of urbanisation, instead of using statistical proxies such as night-time lighting.

It can be used to measure access to services and infrastructure in different territorial arrangements (e.g. with different population sizes or densities).

The Degree of Urbanisation makes it possible to classify local government units, such as municipalities, in a consistent and nuanced manner. It allows for a more granular analysis of the urban-rural continuum, making it possible to label each municipality in Poland as either a “city”, a “town or semi-dense area” or a “rural area”.

Box 1.6. The Degree of Urbanisation

The Degree of Urbanisation is a harmonised method to allow for international statistical comparisons on urbanisation, to complement the definitions used by national statistical offices. It was developed by the European Union, the OECD, the World Bank and several United Nations agencies (UN Statistical Commission, 2020[34]). It applies estimated population size and density thresholds applied to a global grid with cells of 1 km2 to identify three main settlement types (EU et al., 2021[35]):

Cities (or densely populated areas) have a population of at least 50 000 and are made up of contiguous grid cells that have a density of at least 1 500 inhabitants per km2 or are at least 50% built up.

Towns and semi-dense areas (or intermediate density areas) have a total population of at least 5 000 and are made up of contiguous grid cells that have a density of at least 300 inhabitants per km2 and are at least 3% built up.

Rural areas (or thinly populated areas) are cells that do not belong to a city or to a town or semi-dense area.

An extension of the methodology, currently in progress, further disaggregates the typologies, by identifying cities, towns, suburban or peri-urban areas, villages, dispersed rural areas and mostly uninhabited areas. These grids are used as building blocks for identifying FUAs.

Source: UN Statistical Commission (2020[34]), “A recommendation on the method to delineate cities, urban and rural areas for international statistical comparisons”, https://unstats.un.org/unsd/statcom/51st-session/documents/BG-Item3j-Recommendation-E.pdf; EU et al. (2021[35]), Applying the Degree of Urbanisation - A Methodological Manual to Define Cities, Towns and Rural Areas for International Comparisons, http://dx.doi.org/10.2785/706535.

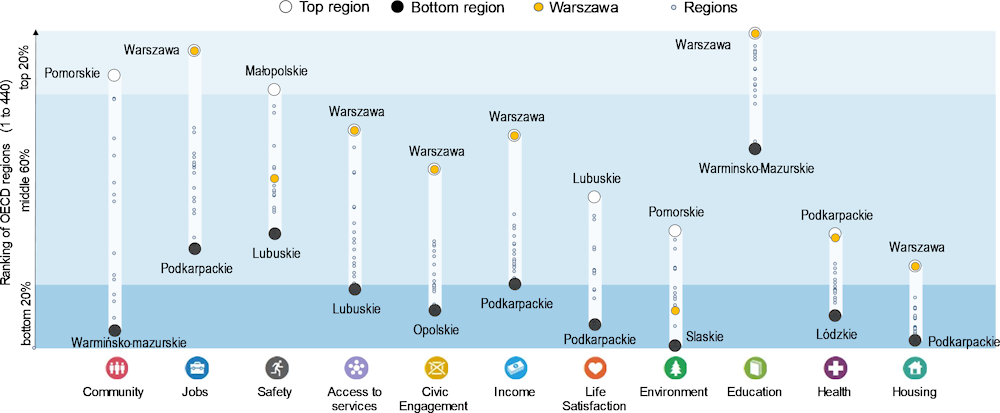

The two approaches – the FUAs and the Degree of Urbanisation – look at urban and rural territories from different perspectives. FUAs focus on functional linkages (commuting) among municipalities in areas characterised by a high level of interaction. The Degree of Urbanisation takes a morphological point of view, looking at population size and density and built-up areas, without considering relationships among municipalities. Both perspectives are useful and can be combined to better understand urban-rural linkages, including within FUAs, and how cities may provide services and opportunities to surrounding areas. Figure 1.5 presents the Wrocław FUA as an example; the city is the core of the FUA, while the rest of the municipalities in the FUA are either rural areas or towns and mid-dense areas.

Figure 1.5. Example of settlement patterns in the FUA of Wrocław

Note: Map based on data estimated for the year 2015.

Source: Based on data from European Commission (n.d.[36]) Global Human Settlement Layer, and OECD (2022[28]), Functional Urban Areas by Country, https://www.oecd.org/regional/regional-statistics/functional-urban-areas.htm.

Understanding existing urban-rural partnerships can highlight opportunities for greater spatial integration across Poland

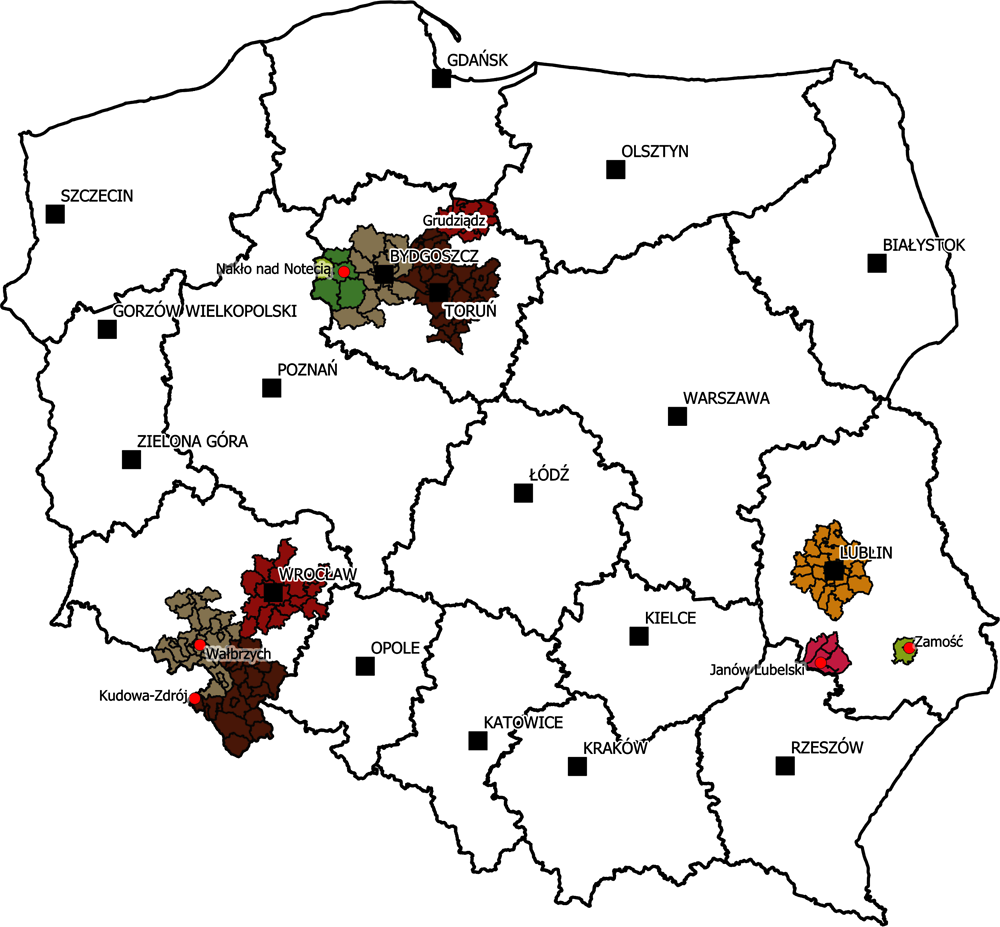

The analysis presented in this chapter is followed by a discussion in Chapter 2 of how fostering and strengthening urban-rural partnerships could benefit Poland and then, in Chapter 3, a review of policies and governance approaches needed to make the most of such partnerships. Those two chapters are grounded on the definitions of FUAs in the Polish strategic development framework, which are different from the FUAs as OECD units of analysis. Chapters 2 and 3 are informed by responses to a comprehensive questionnaire prepared by the OECD for the national government,4 as well as 19 online interviews conducted in 2021 with local and national level officials, academic experts and representatives of civil society organisations. The OECD supported this assessment with a questionnaire to local administrators in FUAs in three regions selected by the Ministry of Funds and Regional Policy (Figure 1.6):

Kujawsko-Pomorskie Region: FUA Bydgoszcz, county Nakielski, FUA Grudziądz.

Dolnośląskie Region: FUA Wrocław, health resort municipalities – with Jelenia Góra, FUA Wałbrzych.

Lubelskie Region: FUA Lublin, FUA Zamość, FUA Janów Lubelski.

Figure 1.6. Selected regions

Source: Ministry of Development Funds and Regional Policy of Poland.

All three regions face significant challenges, such more rapid population declines than across Poland as a whole. The three regions also share environmental challenges, all ranking in the bottom 16% OECD regions (OECD, 2020[21]), and in accessibility to services, as well as in labour market conditions, which limit the potential of well-being in their urban and rural territories.

The responses to the questionnaires inform discussions in this report of the economic, social and environmental dimensions of well-being. The analysis in these regions, together with desk research on other existing partnerships in the country, helped to scale up the report’s recommendations for ways to develop and improve urban-rural partnerships in Poland.

Characteristics of urban and rural areas in Poland

This section reviews the definitions and identification methods of urban and rural territories in Poland and in the OECD methodologies. Based on the OECD definitions, it provides a summary of the main characteristics of urban and rural areas, taking into account the national settlement structure, with a particular focus on FUAs.

The results show that the Polish spatial structure is characterised by a mixture of urban, mid-dense and rural territories, and the level of urbanisation is below the OECD average, since a large share of population lives in rural areas. Even FUAs include large numbers of rural municipalities, highlighting the importance of fostering complementarities and synergies. Poland also shows marked regional differences in the structure of urban and rural areas, which calls for a key role of regions and counties in exploiting the potential of urban-rural linkages.

The national classification of urban and rural areas follows administrative criteria

In Poland, the administrative classification, which is based on the National Official Register of Territorial Division of the Country (TERYT), includes three main tiers, namely regions (voivodeships), counties (powiats) and municipalities (gminas). Larger cities have county status. As of 1 January 2022, the administrative division of Poland included 16 regions, 314 counties, 66 cities with county status and 2 477 municipalities (Statistics Poland, 2021[37]).

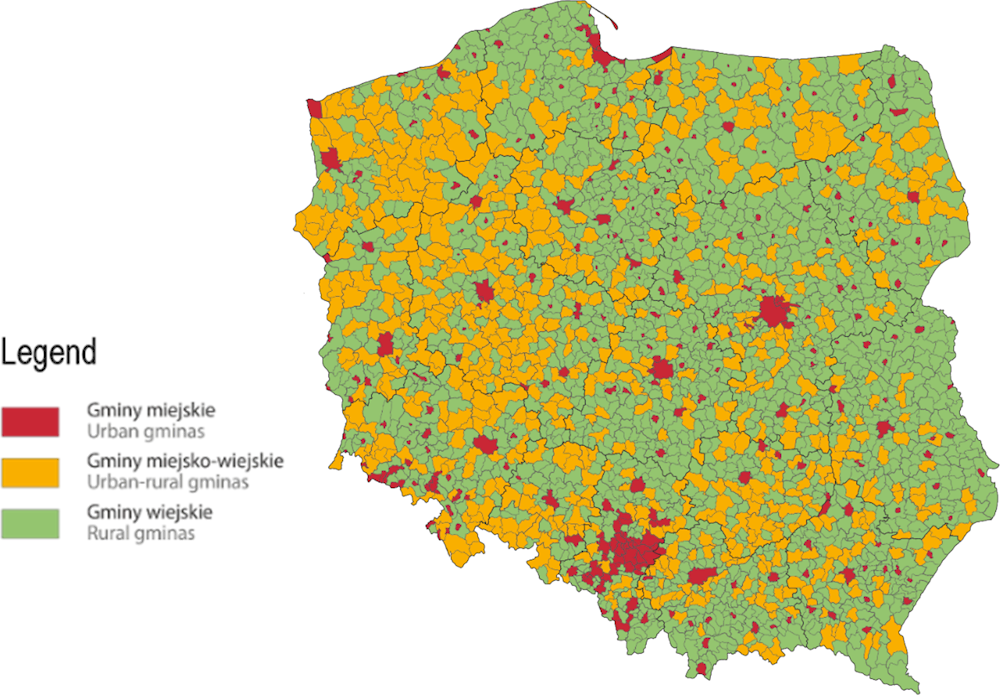

The administrative classification is at the basis of the identification of urban and rural areas, which considers administrative criteria and divides municipalities into three types (Figure 1.7):5

Urban municipalities, which coincide with the boundaries of the city or town6 forming the municipality (urban municipalities may also be cities with a county status).

Urban-rural municipalities, which include both the town and surrounding rural areas.

Rural municipalities, which do not have a city or town within their area.

The classifications are updated every year, as a result of changes in the national administrative division (Statistics Poland, 2021[37]). As of 1 January 2022, Poland had 302 urban municipalities, 662 urban-rural municipalities and 1 513 rural municipalities.

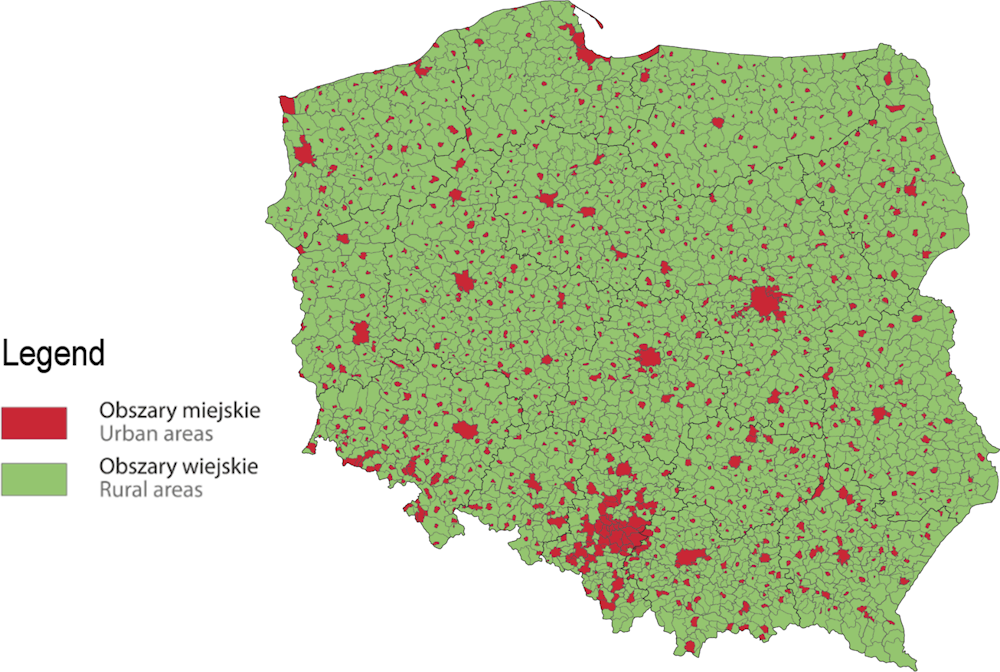

Based on those classifications, urban and rural areas are identified as follows (Figure 1.8):

Urban areas are identified by the administrative boundaries of cities and towns – that is, areas of urban municipalities and towns in urban-rural municipalities (Statistics Poland, 2022[38]).

Rural areas are the remaining areas outside the administrative boundaries of the cities – that is, the rural municipalities and the rural parts of urban-rural municipalities.

Figure 1.7. Types of municipalities in Poland, 2022

Note: Municipalities are classified according to the TERYT register as of 1 January 2022.

Source: Statistics Poland (2022[38]), Types of Gminas and Urban and Rural Areas, https://stat.gov.pl/en/regional-statistics/classification-of-territorial-units/administrative-division-of-poland/types-of-gminas-and-urban-and-rural-areas/.

Figure 1.8. Urban and rural areas in Poland, national classification, 2022

Note: Municipalities classified according to the TERYT register as of 1 January 2022.

Source: Statistics Poland (2022[38]), Types of Gminas and Urban and Rural Areas, https://stat.gov.pl/en/regional-statistics/classification-of-territorial-units/administrative-division-of-poland/types-of-gminas-and-urban-and-rural-areas/.

Poland has larger shares of its population in rural areas, towns and semi-dense areas than the OECD average, and a smaller share in cities

As described above, two OECD tools have been used to analyse urban and rural areas in Poland: the Degree of Urbanisation and FUAs.

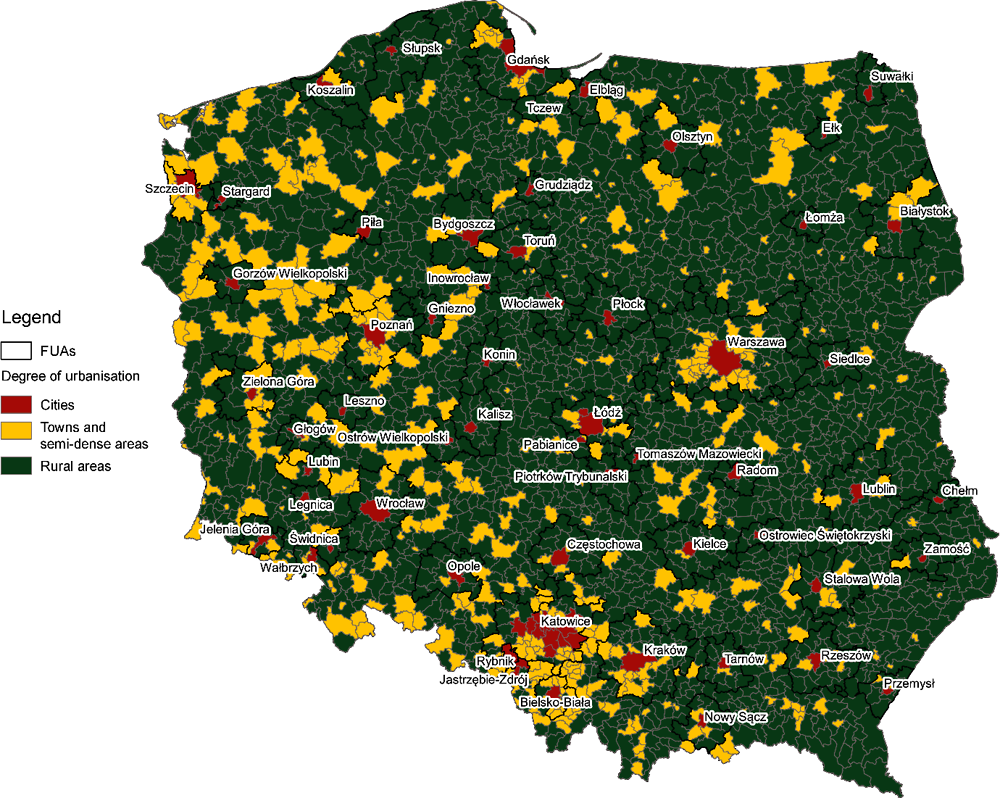

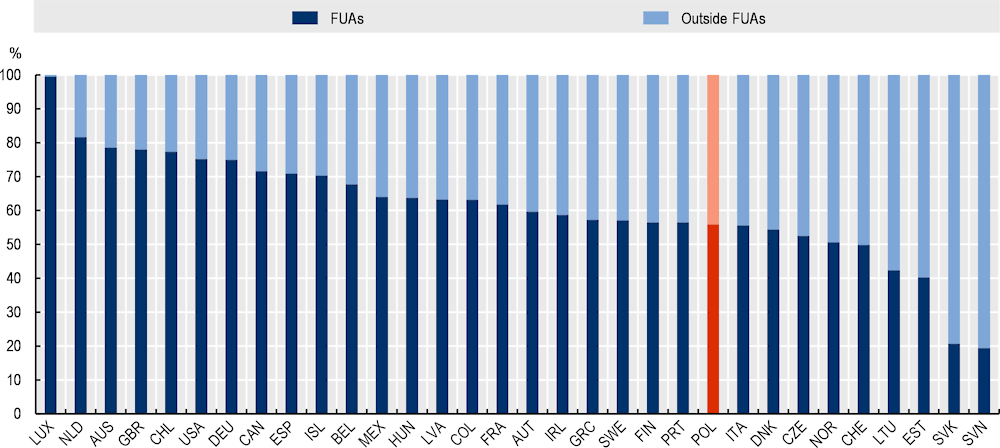

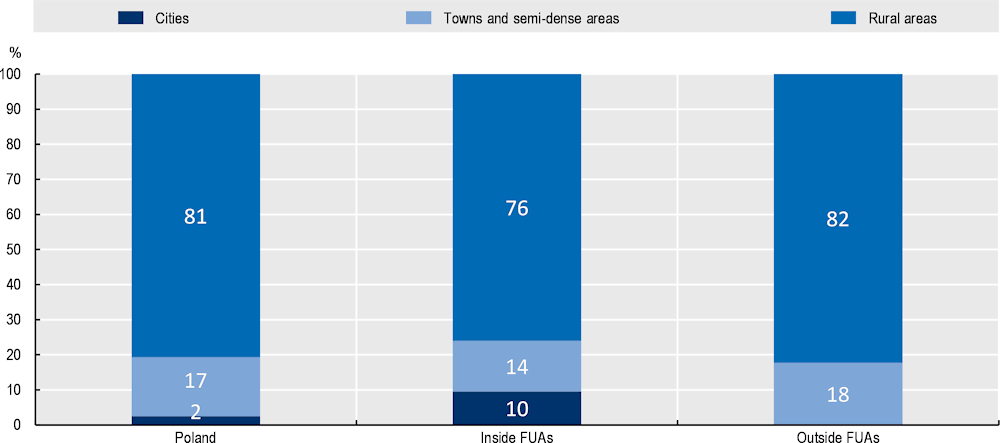

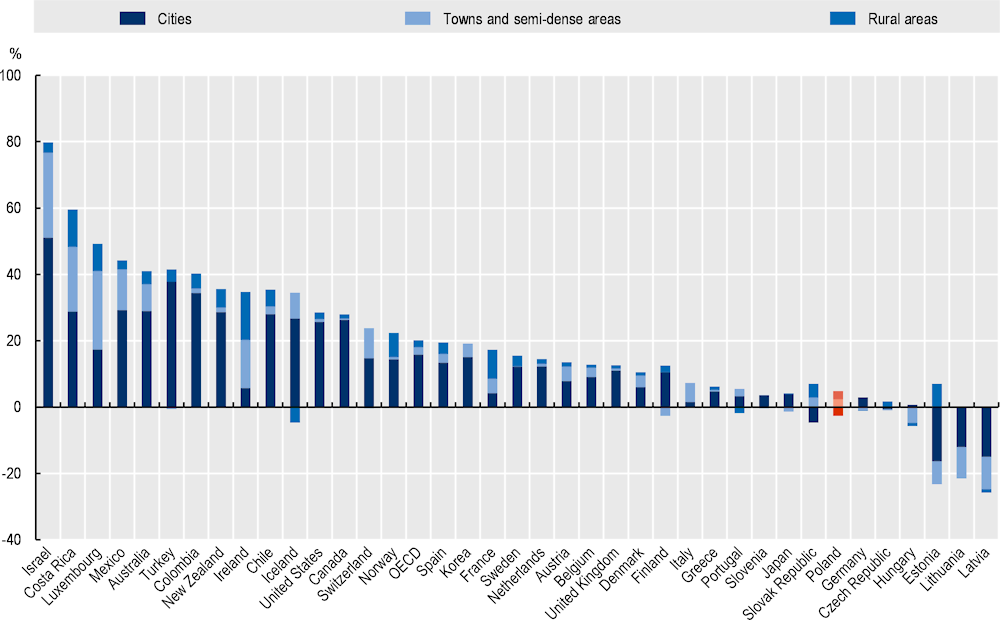

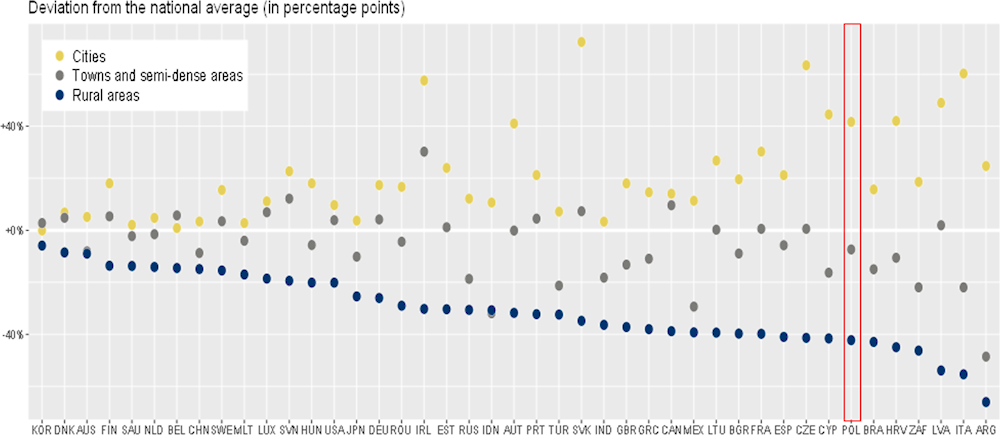

Measured by the Degree of Urbanisation, 76% of Poland’s municipalities are classified as rural areas (accounting for 81% of the total national surface area), while 21% are classified as towns and semi-dense areas (17% of total surface area), and the remaining 3% are classified as cities (2% of total surface area).7 Poland also has just 28% of its population living in cities, compared with the OECD average of 50%. Conversely, as shown in Figure 1.9, a larger share of Poland’s population lives in towns and semi-dense areas (33% vs. the OECD average of 26%) and in rural areas (40% vs. the OECD average of 24%). This calls for better integration between the settlements types to exploit the country’s development potential. While cities are the engines of economic growth and provide agglomeration economies, their attractiveness in Poland is clearly limited, as discussed further below. Better integration between urban and rural areas should guarantee services and opportunities to people living in rural areas (as well as population living in towns and semi-dense areas) across all the territory.

Figure 1.9. Share of population in cities, towns and semi-dense areas, rural areas: a comparison between Poland and other OECD countries, 2015

Source: Population data estimates based on the European Commission (n.d.[36]) Global Human Settlement Layer (GHSL) grid and OECD (n.d.[39]), OECD Regional Statistics, https://doi.org/10.1787/region-data-en.

As Figure 1.10 shows, towns and semi-dense areas are found close to core cities, especially the largest ones (e.g. Katowice, Poznań, Warszawa). This suggests a dispersed urban form around the main cities. However, the spatial structure varies across the country: while regions in southern and western Poland have a relatively high number of towns and semi-dense areas, eastern and central Poland have mainly rural municipalities. In both cases, improved urban-rural linkages can foster economic development and ensure a more sustainable use of land and natural resources, and (especially in less dense regions) could address accessibility to (urban) services and opportunities.

Figure 1.10. Municipalities in Poland classified according to the Degree of Urbanisation

Note: Map based on data estimated for the year 2015.

Source: Author’s elaboration from European Commission (n.d.[36]) Global Human Settlement Layer and OECD (2022[28]), Functional Urban Areas by Country, https://www.oecd.org/regional/regional-statistics/functional-urban-areas.htm.

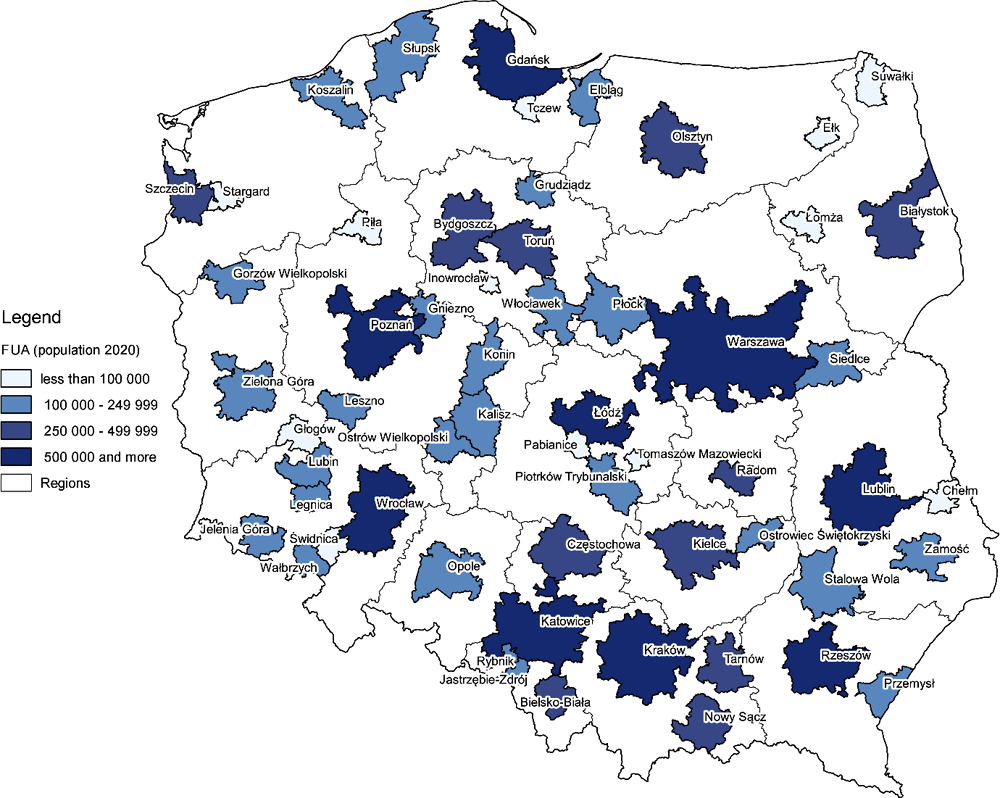

The cities identified according to the Degree of Urbanisation are also identified as the core cities of FUAs. In Poland, 58 FUAs have been identified by applying the OECD methodology and official statistics on population (Figure 1.11), which applies a minimum threshold of 50 000 inhabitants (in the year 2020). Out of the 58 FUAs, 9 FUAs have more than 500 000 inhabitants (metropolitan areas); 11 FUAs have between 250 000 and 500 000; 27 FUAs have between 100 000 and 250 000; and 11 FUAs have between 50 000 and 100 000. A dedicated webpage (OECD, 2021[40]) shows the list of municipalities for each FUA in OECD countries, including Poland.

As noted in the previous section, FUAs identify territories beyond administrative borders and provide a functional perspective on a key type of urban-rural linkages, commuting, which is also related to other linkages, such as agglomeration benefits, housing and the provision of services. The polycentric settlement structure of Poland provides a great potential for FUAs to promote a diffusion of urban agglomeration benefits beyond the limits of cities and thereby support balanced regional and national growth.

In 2020, Poland’s 58 FUAs were home to 21.25 million people, or 55.8% of the national population – much lower than the OECD average of 66% (Figure 1.12). This confirms the relatively low “urban” dimension of the Polish national spatial structure and – conversely – the relevance of non-urban areas for the country.

Figure 1.11. FUAs in Poland, classified by population size, 2020

Source: Based on OECD (2022[28]), Functional Urban Areas by Country, https://www.oecd.org/regional/regional-statistics/functional-urban-areas.htm.

Figure 1.12. Share of national population in FUAs in OECD countries, 2019

Note: No data available for the following countries: Costa Rica, Japan, Korea, Israel, New Zealand, and Turkey. Data for Belgium refer to FUAs with population larger than 250 000 inhabitants.

Source: Based on OECD (2022[41]), “Metropolitan areas”, https://doi.org/10.1787/data-00531-en (accessed on 7 March 2022).

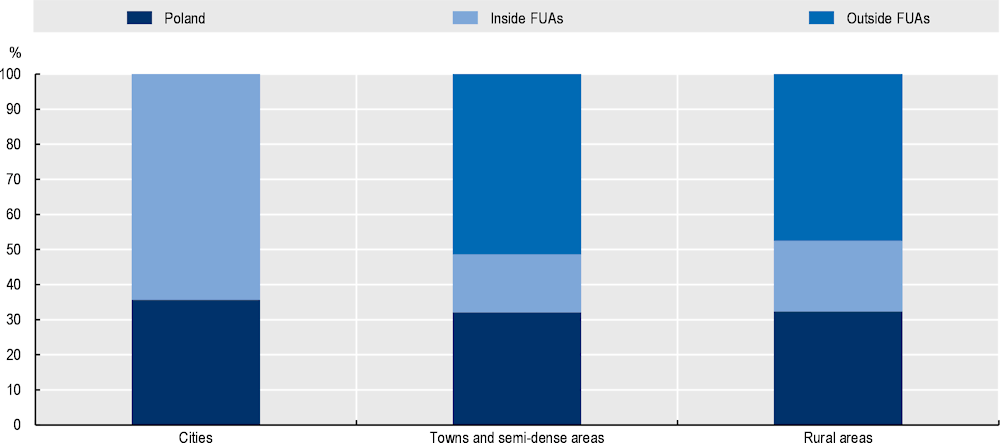

Large shares of commuting zones within FUAs in Poland are rural

Urban areas in Poland are characterised by relatively low-density development (Kurek, Wójtowicz and Gałka, 2020[15]). Within the Polish FUAs, in 2019, 37% of the population lived in municipalities that can either be classified as towns and semi-dense areas (15%) or rural areas (22%) according to the Degree of Urbanisation (Figure 1.13). Furthermore, more than three-quarters of municipalities within FUAs can be classified as rural (Figure 1.14).

Figure 1.13. Share of population living in municipalities in FUAs and outside FUAs, by Degree of Urbanisation, 2019

Note: Population refers to residents in municipalities.

Source: Based on European Commission (n.d.[36]) Global Human Settlement Layer (GHSL), and data from the Ministry of Development Funds and Regional Policy of Poland.

Figure 1.14. Share of area in FUAs and outside FUAs, by the Degree of Urbanisation, 2019

Source: Based on European Commission (n.d.[36]) Global Human Settlement Layer (GHSL), and data from the Ministry of Development Funds and Regional Policy of Poland.

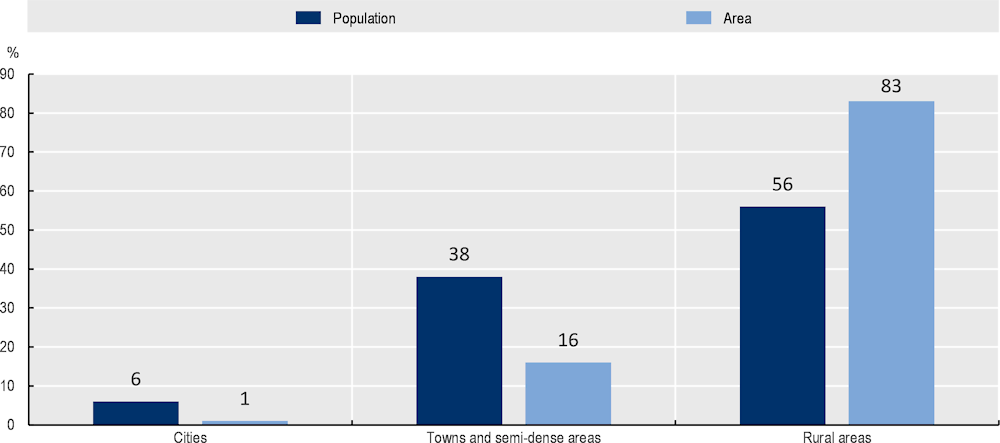

The mix of urban and rural settlement types is particularly evident in the commuting zones within FUAs in Poland, where only 6% of the population lives in municipalities that can be classified as cities, while 56% lives in rural settlements, and 38% in towns and semi-dense areas (Figure 1.15). In such a spatial structure, more integration and linkages among municipalities within FUAs would be a key tool to achieve the benefits associated with urban agglomerations (Ahrend et al., 2017[42]). Outside Polish FUAs, while 53% of the population lives in municipalities classified as rural areas, the remaining 47% lives in towns and semi-dense areas. This shows the potential of towns to serve as focal points for rural development.

Figure 1.15. Share of population and surface area in the commuting zones of FUAs in Poland, by the Degree of Urbanisation, 2019

Note: Population refers to residents in municipalities.

Source: Based on European Commission (n.d.[36]) Global Human Settlement Layer (GHSL), and data from the Ministry of Development Funds and Regional Policy of Poland.

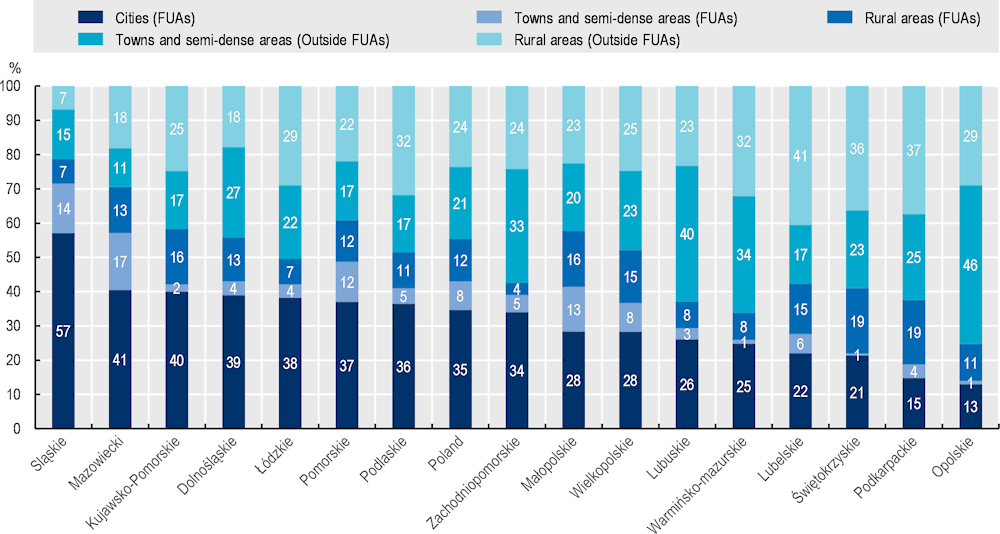

The settlement structure differs across regions and FUAs

The share of population living in urban and rural areas varies considerably across Poland. Śląskie is the most urbanised region in Poland, with 79% of its population living in FUAs, including 57% living in municipalities classified as cities. Mazowieckie region, which includes Warszawa, also has a large share of its population living in FUAs (71%), but its population is more dispersed, with 41% of FUA residents living in cities, 17% in towns and semi-dense areas, and 13% in rural municipalities. At the opposite end of the spectrum, the Opolskie region has just 25% of its population living in the region’s only FUA, while most others live in towns and semi-dense areas (Figure 1.16).

This settlement pattern highlights the heterogeneity of Poland, which is likely to have differentiated impacts in terms of linkages between urban and rural areas. Conversely, existing linkages may shape future settlement patterns (Korcelli, 2018[43]). For example, metropolitan regions tend to have a higher concentration of people and economic activities, as well as closer integration of urban centres with their surrounding areas. As a result, they are likelier to face challenges related to congestion, and rural areas in those regions are likelier to show peri-urban features. More sparsely populated regions are likely to face different issues, such as limited access to public services. However, some smaller market-towns (equivalent to small towns) can have a relatively high level of integration with their surrounding rural areas (Mayfield et al., 2005[44]).

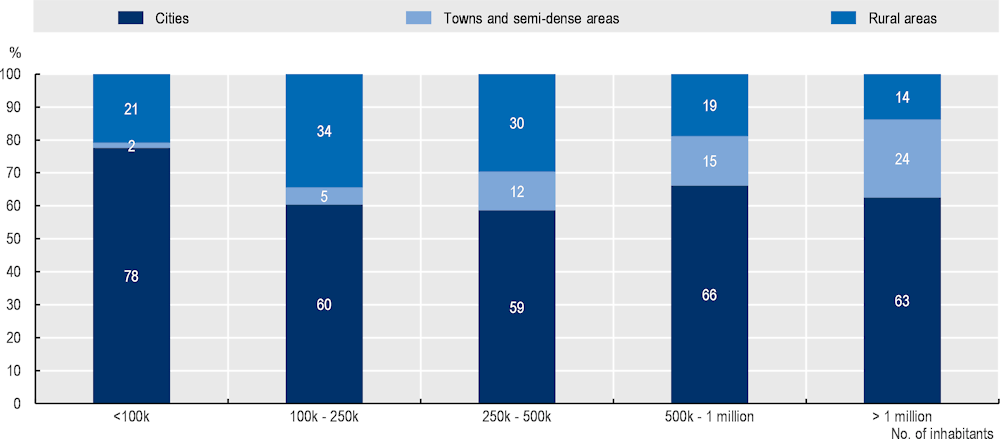

Poland’s 58 FUAs are also heterogeneous in their size. The population size of the 58 FUAs ranges from 3.17 million (Warszawa) to 73 200 inhabitants (Ełk). With the exception of FUAs smaller than 100 000 inhabitants, the larger the size of the FUA, the larger the share of population living in towns and semi-dense areas.8 The share of rural population, on the other hand, decreases with FUA size. This latter may imply potential challenges in terms of public service provision and accessibility for the rural settlements, which tend to be more dispersed than urban settlements (Figure 1.17).

Figure 1.16. Share of population in regions, by the Degree of Urbanisation, 2019

Note: population refers to residents in gminas. Regions are ranked from the largest to the lowest share of regional population living in FUAs.

Source: Based on Global Human Settlement Layer (GHSL) and data from the Ministry of Development Funds and Regional Policy of Poland.

Figure 1.17. Share of population in FUAs, by FUA size, 2019

Note: Population refers to residents in gminas.

Source: Based on Global Human Settlement Layer (GHSL) and data from the Ministry of Development Funds and Regional Policy of Poland.

Urban-rural labour market linkages

This section shows the main characteristics of urban-rural linkages emerging from commuting flows, which link places where the people work and live. With a high share of population living in commuting zones, Poland FUAs are rather dispersed as compared with OECD FUAs. Therefore, flows connecting places are rather dispersed as well and involve a high level of rural-to-urban interactions. Cities, especially the largest ones, are highly attractive for commuters, while rural areas have fewer jobs than residents. Additionally, many small and medium-size FUAs have negative commuting balances, indicating a low attractiveness. A deeper look on the internal spatial structure of FUAs shows that, in many (often large) FUAs, mid- and low-dense municipalities attract commuters, suggesting functional interdependencies within urban and rural areas in FUAs. Finally, FUAs show a high level of attractiveness for residents outside FUAs.

Commuting flows show a high level of rural-to-urban interactions in Poland

Polish FUAs are dispersed, with a higher share of population living in commuting zones than the OECD average, especially in large FUAs. As of 2020, 43% of Poland’s FUA population lived in commuting zones, far above the 25% OECD average. Functional relationships are also likely to be dispersed across space. The most populated FUAs have even larger shares of people in commuting zones, indicating that urban growth in those areas involved spatial dispersion, or sprawl. The distribution of people within 50 FUAs remained relatively stable from 2000 to 2020, while the largest FUAs decentralised more. Almost all the FUAs with more than 500 000 inhabitants (except for Lublin and Rzeszów) have seen rising shares of population in commuting areas and decreasing shares in the core city (Table 1.1).

Table 1.1. Concentration in core cities of FUAs with more than 500 000 inhabitants

|

Population (2020) |

Concentration in core cities (%, 2020) |

Var. % concentration in core cities (2000-20) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

|

Warszawa |

3 209 784 |

56 |

-3.32 |

|

Katowice |

2 486 510 |

55 |

-0.50 |

|

Kraków |

1 423 235 |

55 |

-2.27 |

|

Gdańsk |

1 170 990 |

61 |

-5.82 |

|

Poznań |

993 656 |

54 |

-8.18 |

|

Łódź |

903 719 |

82 |

-2.46 |

|

Wrocław |

883 468 |

73 |

-2.61 |

|

Lublin |

670 856 |

50 |

0.13 |

|

Rzeszów |

508 044 |

40 |

0.30 |

Note: Concentration is measured by the share of population of the core city over total FUA population.

Source: Based on OECD (2022[41]), “Metropolitan areas”, https://doi.org/10.1787/data-00531-en (accessed on 7 March 2022).

Both the strength and the direction of commuting flows are indicative of functional relationships across territories. When population and jobs are evenly distributed, commuting flows are likely to be. People may be able to work closer to where they live, with shorter commutes that do not require going into urban areas, and commuting flows between urban and rural areas may be bi-directional. When jobs are spatially concentrated, however, commuters all tend to flow into the main (urban) hubs. It is particularly useful to assess commuting flows between municipalities within FUAs, between FUAs and their catchment areas, and among municipalities outside FUAs. The balance between in-commuting and out-commuting also helps to gauge the relative attractiveness of cities, towns and semi-dense areas, and rural areas as places to work. Some cities that are attractive are the core cities of FUAs, while others are part of their commuting zones.

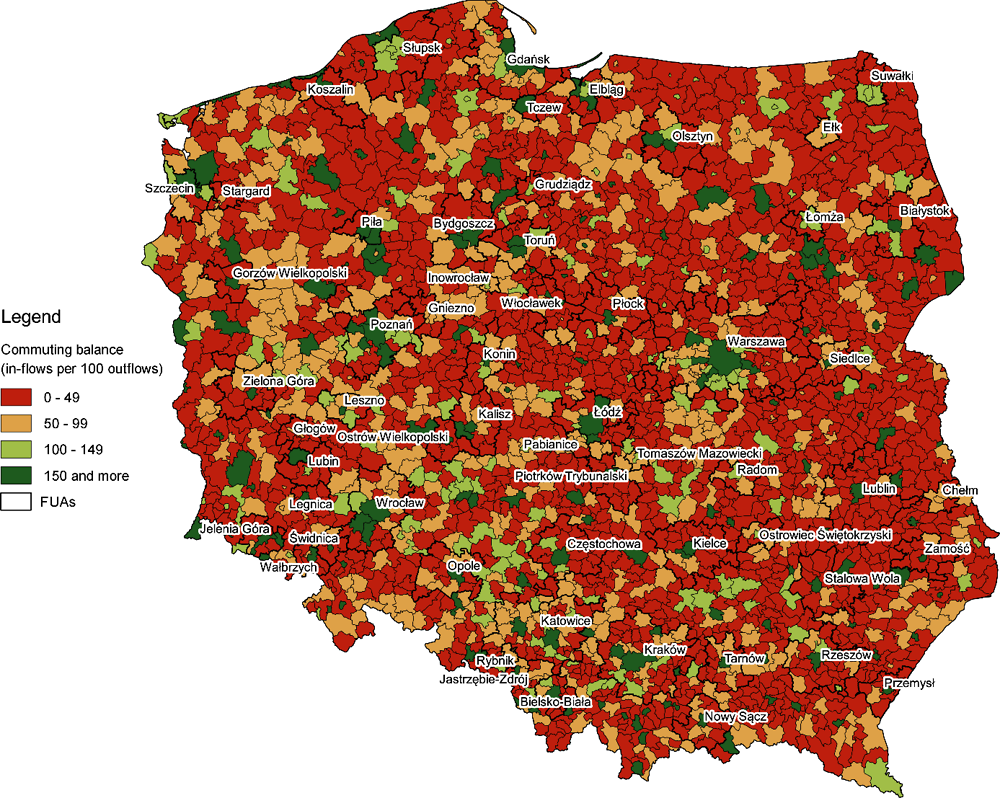

Commuting strongly differs between urban and rural areas. In Poland, only 19% of commuting originates from cities, while cities receive 46% of commuting flows (Table 1.2). Overall, for every 100 commutes out of municipalities classified as cities (according to the Degree of Urbanisation), there are 249 commutes into cities. Rural municipalities receive only 20% of commuting flows, but account for 46% of out-flows. For every 100 commuters leaving rural areas, only 44 come in. Towns and semi-dense areas originate 35% of flows and receive 34%. For every 95 commutes into towns and semi-dense areas, there are 100 commutes out, suggesting they have are relevant both for housing and for employment (Figure 1.18). It should be noted, however, that these data might underestimate actual commuting flows, as suggested for instance by a recent study analysing cell phone data (Office of Spatial Planning of the City of Gdynia, 2021[45]).

Table 1.2. Commuting flows by Degree of Urbanisation of municipalities of origin and destination, 2016

|

Urbanisation degree |

Origin (residence) (%) |

Destination (work) (%) |

Balance (in-flows per 100 out-flows) (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Cities |

19 |

46 |

249 |

|

Towns and semi-dense areas |

35 |

34 |

95 |

|

Rural areas |

46 |

20 |

44 |

Source: From data retrieved from Statistics Poland (2019[46]), Employment-related Population Flows in 2016, https://stat.gov.pl/obszary-tematyczne/rynek-pracy/opracowania/przeplywy-ludnosci-zwiazane-z-zatrudnieniem-w-2016-r-,20,1.html.

Figure 1.18. Commuting balances (in-flows per 100 out-flows) of Polish municipalities, 2016

Source: From data retrieved from Statistics Poland (2019[46]), Employment-related Population Flows in 2016, https://stat.gov.pl/obszary-tematyczne/rynek-pracy/opracowania/przeplywy-ludnosci-zwiazane-z-zatrudnieniem-w-2016-r-,20,1.html.

While settlements are dispersed across urban and rural areas, jobs opportunities are still mainly in urban areas. The ability to commute means that residents of rural areas can access job opportunities in cities (which are linked with their agglomeration benefits) while maintaining a rural lifestyle. In fact, urban areas host most of the economic functions and workplaces. Rural areas host a variety of non-residential functions (e.g. agriculture, forestry, tourism), but they have far fewer jobs than residents. This can increase traffic flows and put pressure on transport infrastructure, with implications for greenhouse gas emissions and air pollution.

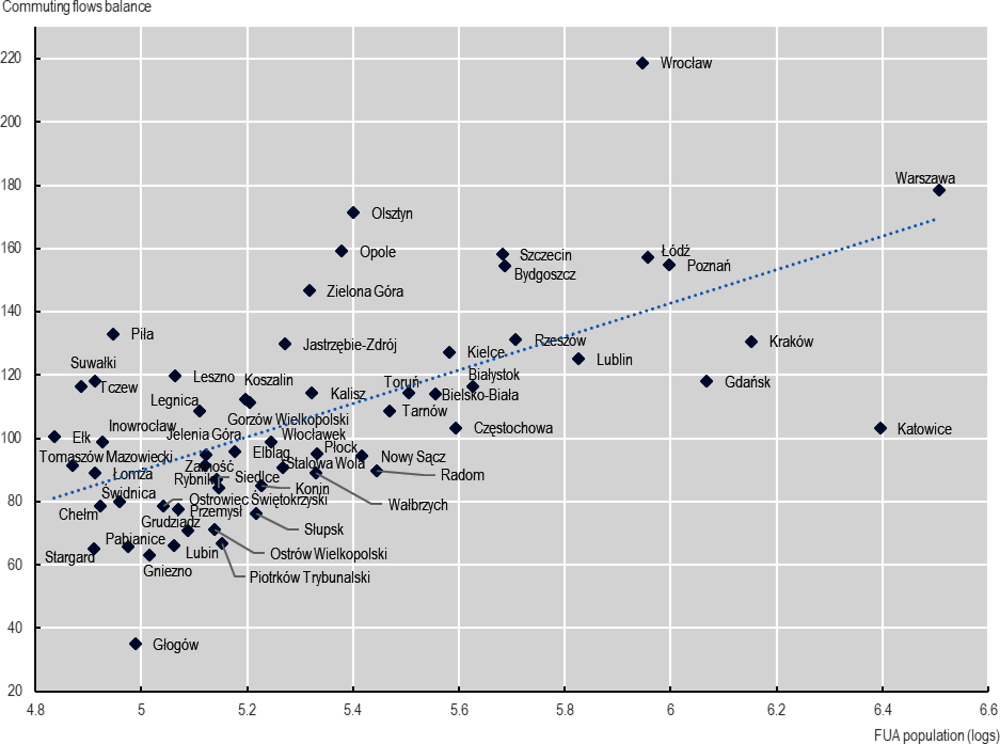

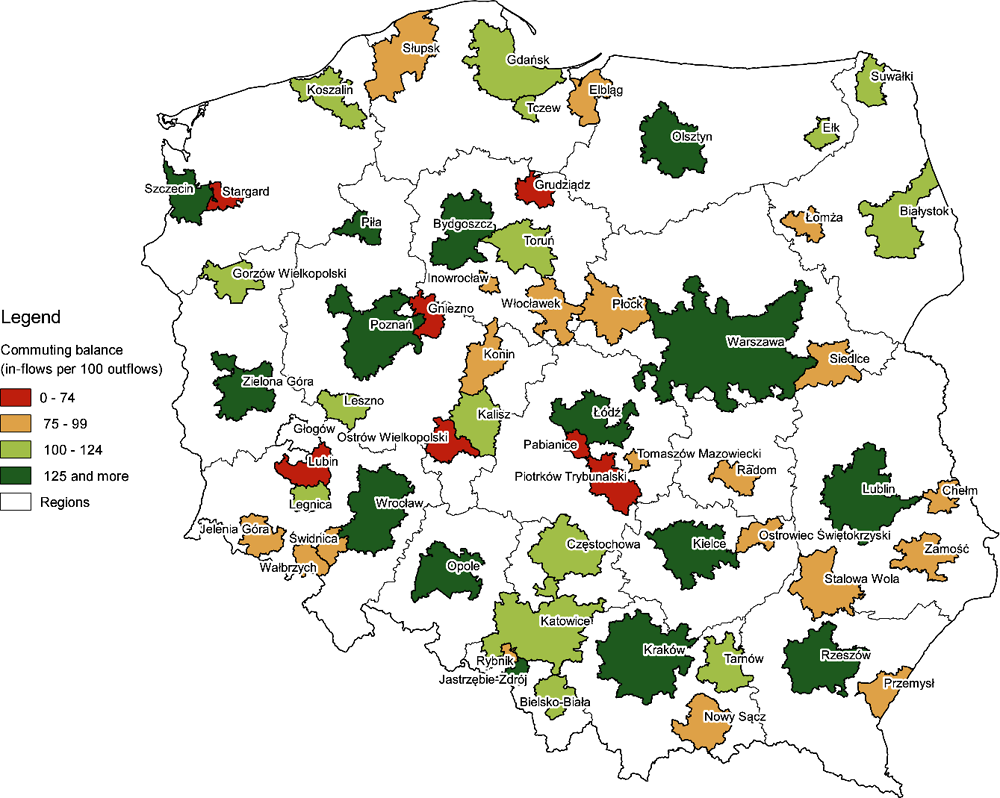

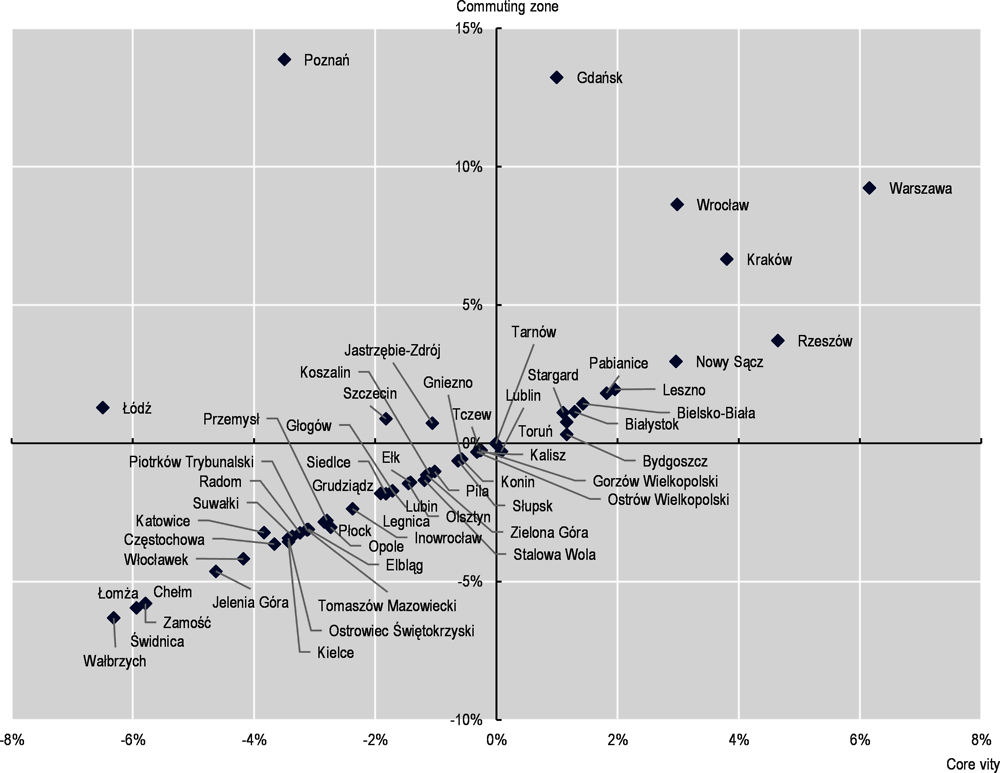

Most large FUAs are attractive to commuters, but many small and medium-size FUAs have negative commuting balances

The most recent data available, for 2016,9 indicate that 51% of flows originate from FUAs (so 49% originate outside FUAs), and 65% of total commuting flows are to destinations within FUAs (reflecting both inbound commutes and commutes within FUAs). There are large differences in commuting balances among FUAs, with the main economic hubs standing out from the rest (Figure 1.19). While 90% of FUAs with more than 250 000 inhabitants have positive commuting balances, about two thirds of FUAs with fewer than 250 000 inhabitants show a negative commuting balance. Proximity to a larger FUA is also relevant for the labour market linkages, since residents of smaller FUAs may commute to larger FUAs (Figure 1.20). Urban-rural linkages may provide opportunities to strengthen the attractiveness of (mainly smaller) FUAs that have negative commuting balances.

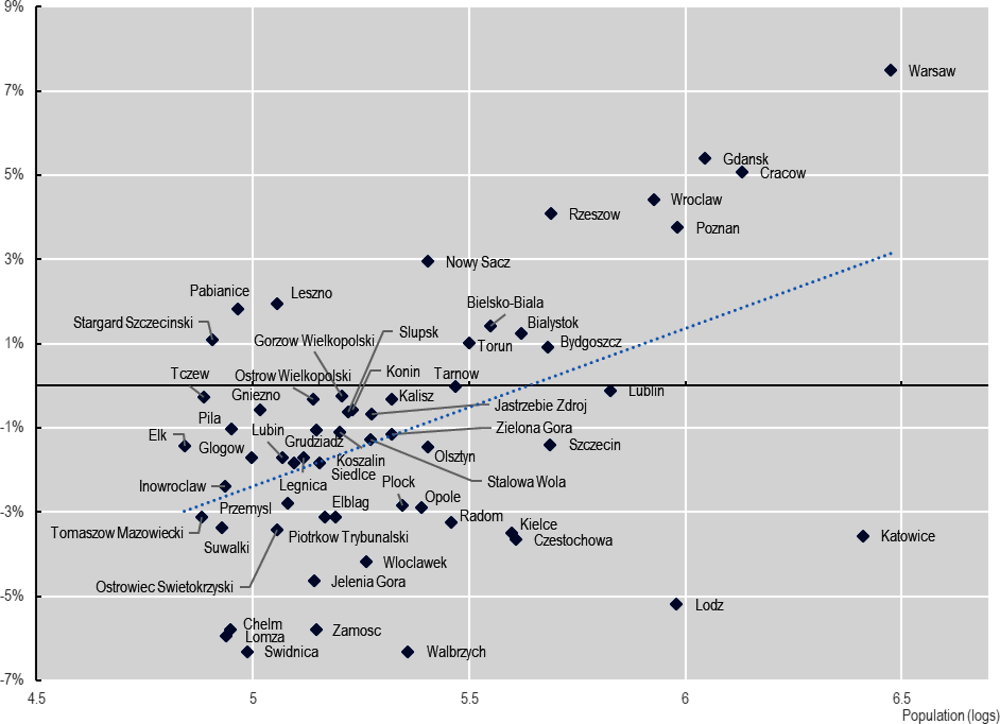

Figure 1.19. Commuting balances (in-flows per 100 out-flows) and FUA population size, 2016

Note: Population size is expressed in logarithms.

Source: From data retrieved from Statistics Poland (2019[46]), Employment-related Population Flows in 2016, https://stat.gov.pl/obszary-tematyczne/rynek-pracy/opracowania/przeplywy-ludnosci-zwiazane-z-zatrudnieniem-w-2016-r-,20,1.html.

Figure 1.20. Commuting balances (in-flows per 100 out-flows) of Polish FUAs, 2016

Note: Values over 100 indicates that the in-commuting towards a FUA exceeds out-commuting from the FUA.

Source: From data retrieved from Statistics Poland (2019[46]), Employment-related Population Flows in 2016, https://stat.gov.pl/obszary-tematyczne/rynek-pracy/opracowania/przeplywy-ludnosci-zwiazane-z-zatrudnieniem-w-2016-r-,20,1.html.

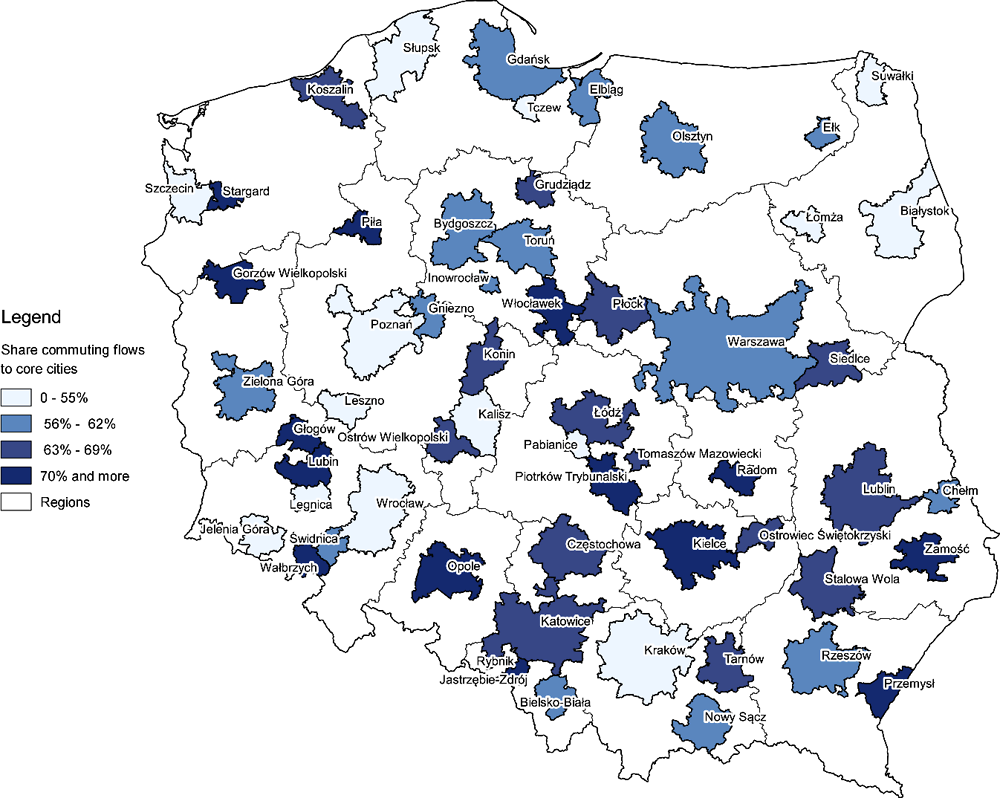

In many FUAs, peri-urban and rural areas attract commuters

Commuting data show that within FUAs, 61% of flows are directed into the core cities from the commuting zones. This still leaves a large share of commutes (39%) directed out of the core cities, indicating considerable dispersion within FUAs. Municipalities in commuting zones, including rural municipalities, have jobs that attract people living outside the municipalities. This suggests that some FUAs are integrated and interdependent in terms of functions – especially the larger FUAs. Other FUAs with a higher concentration index are strongly based on their core cities and might exploit the potential of urban-rural linkages to leverage development across all municipalities within the FUAs (Figure 1.21).

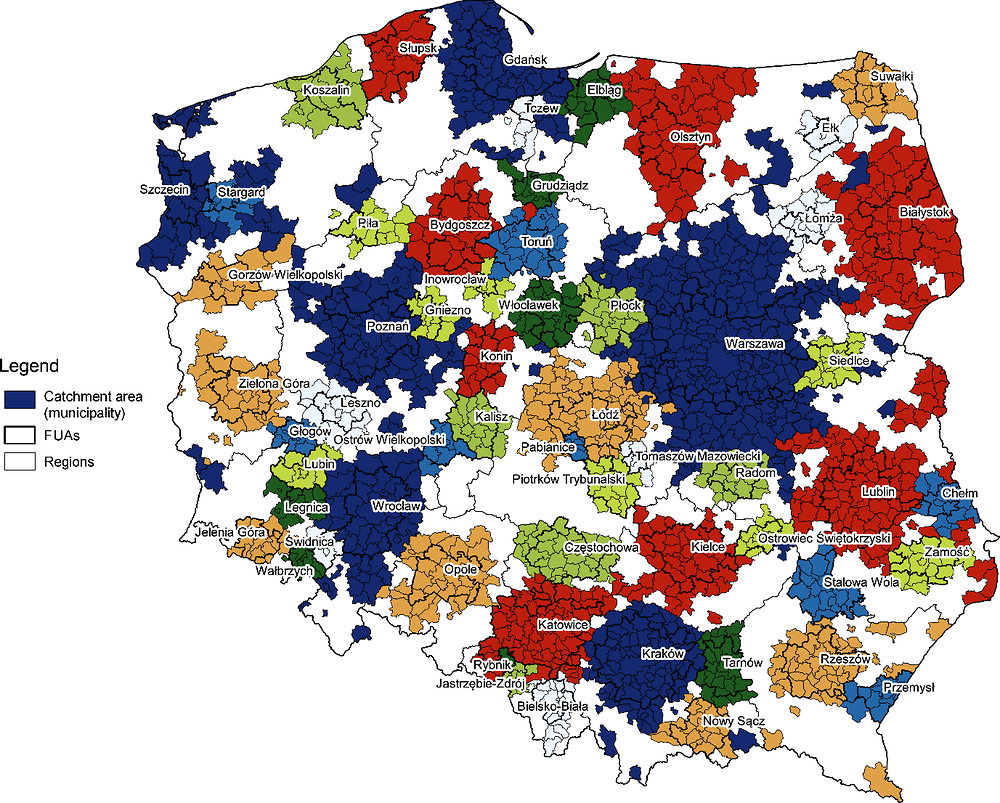

FUAs attract commuters from wider catchment areas

Commuting flows can also be used to measure linkages between FUAs and their surrounding areas, better reflecting functional relationships than distance or travel times can. The data show FUAs are attracting commuting flows from nearby municipalities. These “catchment” areas are clusters of (mainly rural) municipalities outside FUAs that can effectively “borrow” the opportunities and amenities of urban areas. Figure 1.22 shows the catchment areas of FUAs in Poland, which were home to about 9.20 million people in 2020. Combined with the 21.25 million living in FUAs, this means that across Poland, about 30.4 million people, almost 80% of the population, lived either in an FUA or in a catchment area in 2020. Catchment areas are more urbanised than other territories outside FUAs. In catchment areas, 52% of the population lived in municipalities classified as towns and semi-dense areas in 2020, and the rest in rural areas, while areas outside FUAs that are not catchment areas, 59% of the population was in rural areas.

Figure 1.21. Share of commuting flows within FUAs going into core cities, 2016

Note: The figure only reflects internal flows within FUAs (i.e. flows coming from outside the FUAs are excluded)

Source: From data retrieved from Statistics Poland (2019[46]), Employment-related Population Flows in 2016, https://stat.gov.pl/obszary-tematyczne/rynek-pracy/opracowania/przeplywy-ludnosci-zwiazane-z-zatrudnieniem-w-2016-r-,20,1.html.

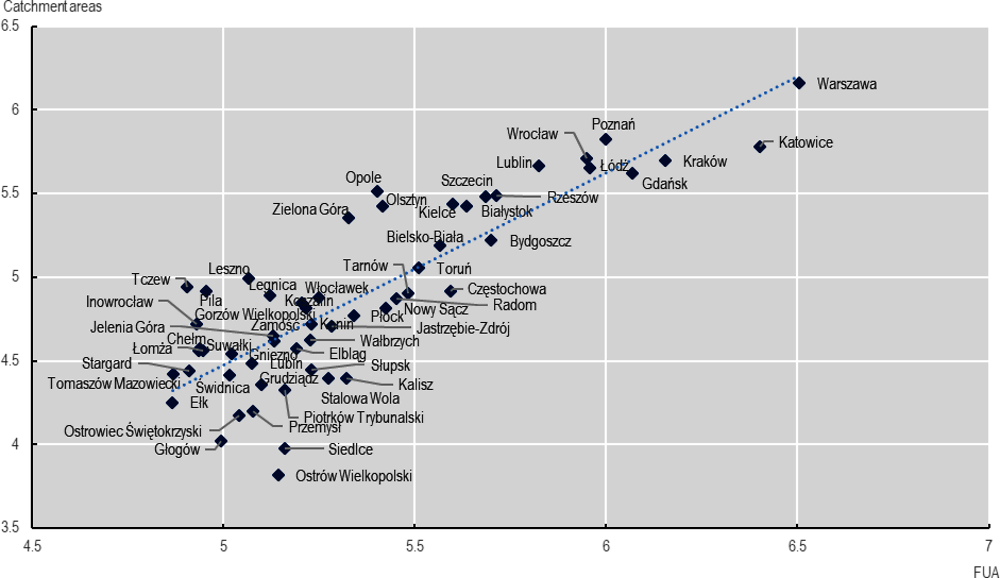

Almost all FUAs in Poland have catchment areas. The only exceptions are Pabianice and Rybńik, which are small and close to larger FUAs (Łódź for Pabianice FUA and Katowice for Rybńik FUA). The larger the FUA, the wider the catchment area (Figure 1.23).

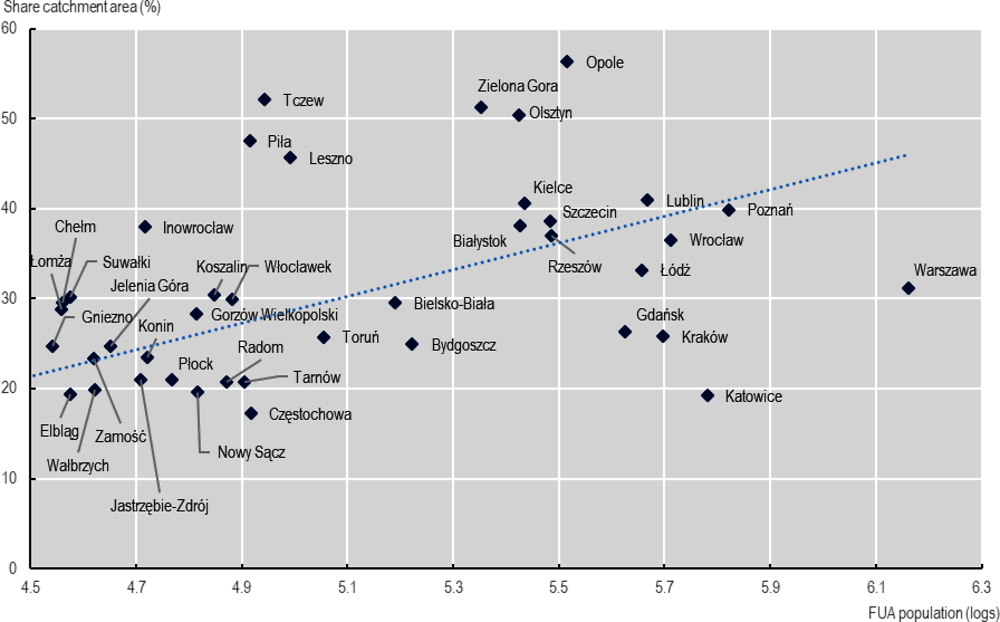

As Figure 1.24 shows, some catchment areas host considerable populations. The catchment areas of the Opole, Olsztyn and Tczew FUAs have more residents than the FUA themselves. Populated catchment areas can exploit mutual beneficial relationships with their FUAs. People hosted in catchment areas benefit from the urban labour markets and urban services and amenities. Moreover, FUAs have local markets they can serve. Leveraging the potential win-win outcomes for urban and rural territories in FUAs and their catchment areas passes through adequate service accessibility and quality. To this extent, infrastructures and connectivity are crucial factors.

Figure 1.22. FUAs and their catchment areas in Poland

Note: Each colour shows a different catchment area. The catchment areas were identified by OECD analysing data from the 2016 municipalities-to-municipalities commuting matrix, assigning each municipality outside FUAs to the FUA that is the top commuting destination for its residents, and then applying a minimum threshold: a municipality was deemed to be a catchment area of an FUA if at least 20% of its total commuting flows went into that FUA.

Source: Based on data retrieved from Statistics Poland (2019[46]), Employment-related Population Flows in 2016, https://stat.gov.pl/obszary-tematyczne/rynek-pracy/opracowania/przeplywy-ludnosci-zwiazane-z-zatrudnieniem-w-2016-r-,20,1.html.

Figure 1.23. Population in FUAs and in FUAs catchment areas.

Note: Population expressed in logarithms.

Source: From data retrieved from Statistics Poland (2019[46]), Employment-related Population Flows in 2016, https://stat.gov.pl/obszary-tematyczne/rynek-pracy/opracowania/przeplywy-ludnosci-zwiazane-z-zatrudnieniem-w-2016-r-,20,1.html.

Figure 1.24. Share of population in FUA catchment areas and FUA population, 2016

Note: Population expressed in logarithms.

Source: From data retrieved from Statistics Poland (2019[46]), Employment-related Population Flows in 2016, https://stat.gov.pl/obszary-tematyczne/rynek-pracy/opracowania/przeplywy-ludnosci-zwiazane-z-zatrudnieniem-w-2016-r-,20,1.html.

Main trends affecting urban-rural linkages in Poland

This section summarises key demographic trends in Poland with implications for urban-rural linkages, as well as changes in physical and digital accessibility.

Poland’s population is declining overall, but there are large territorial differences

Poland’s population declined by 0.4% from 2010 to 2010, while on average, OECD countries saw a 5.8% population increase (OECD, 2022[47]). Projections to 2060 show Poland’s population shrinking by another 14.4%, while OECD countries are projected to see gains averaging 9.3%. Among OECD countries, only Greece, Korea, Japan, Lithuania and Latvia are expected to faster population declines than Poland.

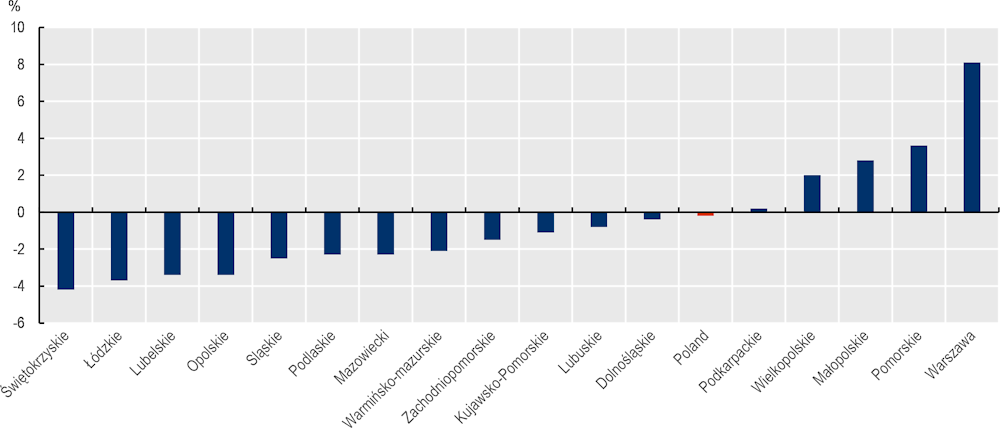

Depopulation in Poland shows striking territorial differences. First, the dynamics of depopulation highly differentiate across Polish regions: from 2010 to 2020, Warszawa’s population grew by 8.1%, while on the opposite end, Świętokrzyskie’s population declined by -4.2% (Figure 1.25).

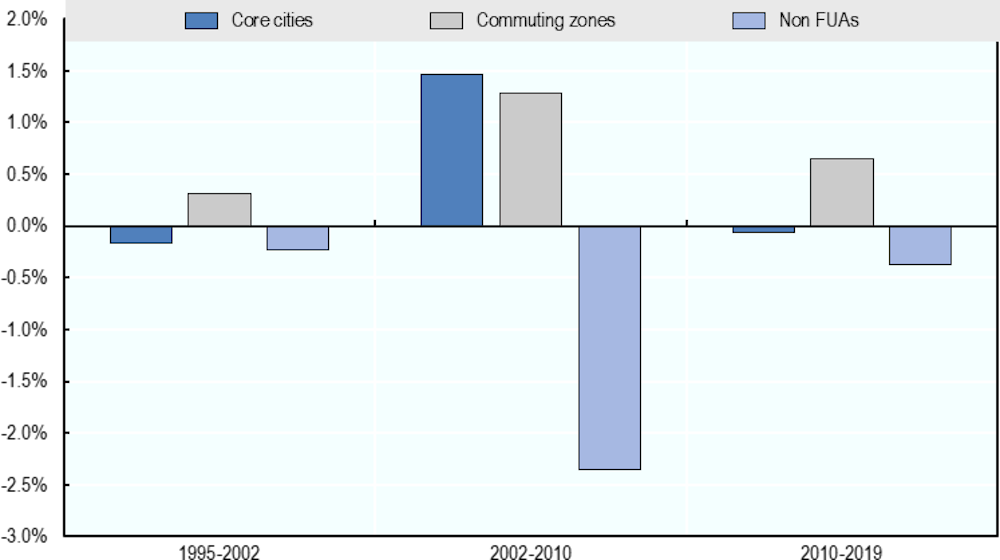

The population of Poland’s FUAs has grown, albeit slowly, while areas outside FUAs saw declines – but three-quarters of FUAs are also shrinking. Between 2010 and 2020, the population outside FUAs in Poland declined by 1.9% (about 331 000 people), while within FUAs, it grew by 0.8% (about 170 000 people). Still, that was one of the lowest growth rates for FUAs in the OECD; on average, the population in FUAs across the OECD grew by 8.1%.10 Moreover, 44 of the 58 Polish FUAs saw population declines (Figure 1.26). This continues a trend, as between 2000 and 2010, 34 FUAs had lost population, and only three of them reversed their trajectory in the last decade (Białystok, Stargard, and Wrocław).

Figure 1.25. Population growth rates in Polish TL2 regions, 2010-20

Note: data refer to OECD TL2 regions (or “large regions”), which are equivalent to the Eurostat NUTS 2016 (OECD, 2021[22]; Statistics Poland, 2021[23]).

Source: Based on OECD (2022[48]), “Regional economy”, https://doi.org/10.1787/6b288ab8-en (accessed on 4 March 2022).

Figure 1.26. Population size and growth rates in Polish FUAs, 2010-20

Source: Based on data from OECD (2022[41]), “Metropolitan areas”, https://doi.org/10.1787/data-00531-en (accessed on 7 March 2022).

The largest FUAs are still gaining population, but most others are shrinking.11 Between 2010 and 2020, most FUAs with more than 500 000 inhabitants gained population, except in a few places experiencing large industrial declines (e.g. Katowice, Łódź).12 In contrast, 35 over 38 FUAs with fewer than 250 000 inhabitants lost population. Notably, official statistics – which are based on registered population in municipalities – can understate population decline, as highlighted by a recent report (Office of Spatial Planning of the City of Gdynia, 2021[45]). If these trends continue, they will put pressure on service provision in both urban and rural areas, making it important to develop mechanisms to guarantee efficient and equitable access to services.

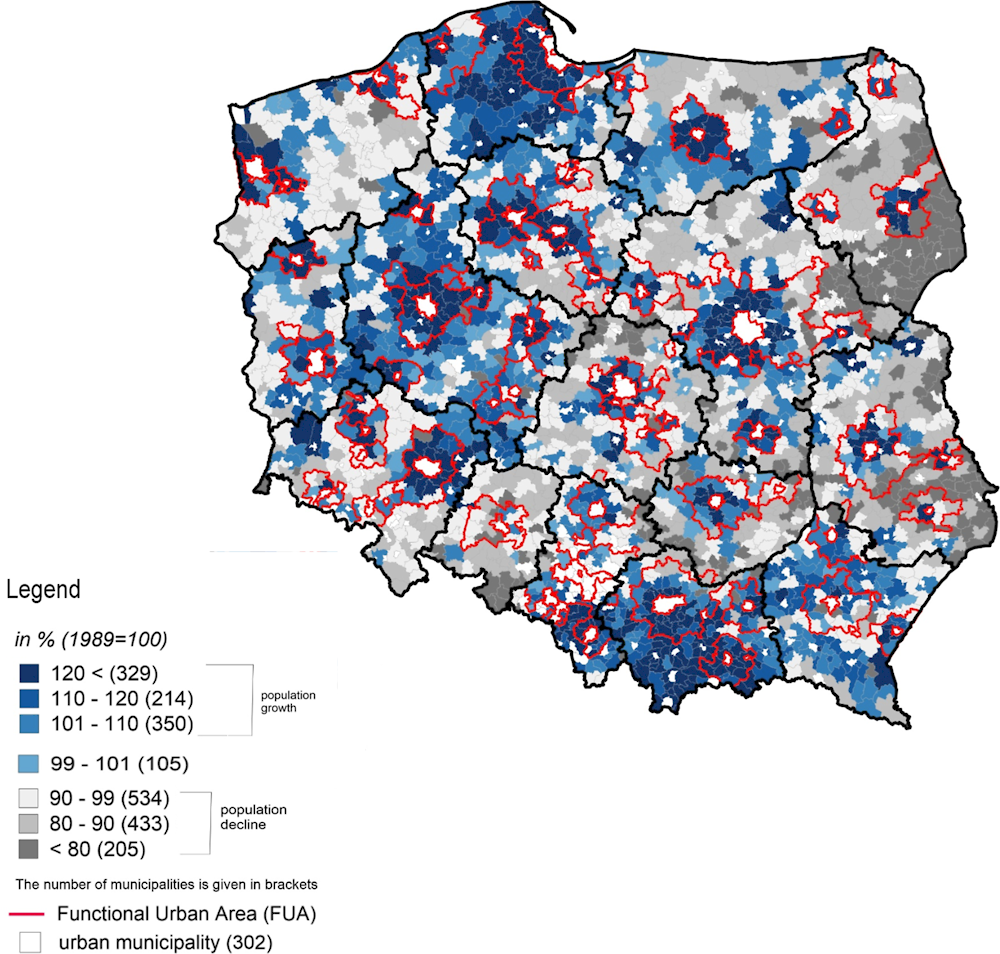

While the rural population outside FUAs is decreasing, commuting zones in FUAs are gaining residents. Estimates based on the Degree of Urbanisation show that in the period 1990-2015, the population of cities declined by 8.6%, while towns and semi-dense areas saw 5.2% growth, and rural areas, 5.4%. This pattern strongly differs from most OECD countries, where cities led national population growth. Actually, in the same period, population growth across the OECD countries averaged 36% in cities, 7.6% in towns and semi-dense areas, and 7.7% in rural areas. Figure 1.27 shows the effects on aggregate national growth of OECD countries provided by the settlement types: while the aggregate population in Poland grew by 2.13% (vs. the OECD average 20.09%), cities gave a negative net contribution by 2.69% (vs. the OECD average 15.82%), towns and semi-dense areas contributed by 2.37% (vs. the OECD average 2.22%) and rural areas contributed by 2.45% (vs. the OECD average 2.08%). As Figure 1.28 shows, the population grew in rural municipalities closer to urban areas (highlighted in red in the figure), while in areas far from cities, the population mostly declined between 1989 and 2018 (Stanny and Strzelecki, 2020[49]). This means the focus of efforts to strengthen urban-rural linkages will have different priorities in different areas. Where rural areas are closer to cities, the focus may be on pressures on land use and resources and on traffic congestion, while for more isolated rural areas, the priority may be to increase rural residents’ access to jobs, infrastructure and services in the FUAs.

Figure 1.27. Contribution to national population growth rate by Degree of Urbanisation, 1990-2015

Source: Using population data estimates based on the European Comission (n.d.[36]) Global Human Settlement Layer (GHSL) grid and OECD (2022[28]), Functional Urban Areas by Country, https://www.oecd.org/regional/regional-statistics/functional-urban-areas.htm.

Figure 1.28. Changes in rural population, 1989-2018

Source: Stanny, M. and P. Strzelecki (2020[49]), “Ludność wiejska”, in Wilkin, J. and A. Halasiewicz (eds.), Polska wieś 2020. Raport o stanie wsi, Wydawnictwo naukowe Scholar, FDPA, Warszawa.

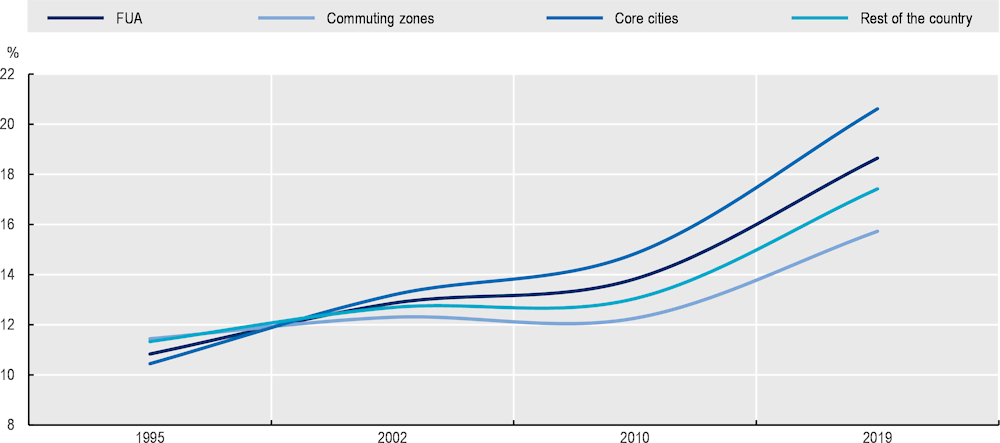

Altogether, from 1995 to 2019, the population in FUAs grew by 2.36 million (12%), while outside FUAs, it decreased 4.32 million (almost 20%). Poland’s total population dropped by 1.86 million (0.5%). Population growth in FUAs has been led by the commuting zones, which grew by 17% from 1995 to 2019 while the population of core cities grew by 10% (Figure 1.29). Suburbanisation in Poland goes beyond shifts in population from large cities to suburbs; people re-settled both from core cities to suburbs and from peripheral areas to suburbs. This includes shifts from rural areas to suburban areas and other mid-density settlements, such as towns (Spórna and Krzysztofik, 2020[50]). However, the above-mentioned patterns differentiate across FUAs. Despite overall population in FUAs increased, over the last decade most FUAs have been characterised by a decrease of population, and in most cases, both core cities and commuting zones registered a population decrease (Figure 1.30).

Figure 1.29. Annual growth rates of population in Poland: FUA core cities, commuting zones and outside FUAs, 1995-2019