This chapter assess water resources governance at different levels, including international, national, basin, provincial and metropolitan scales, aiming to identify key features and gaps of the existing multi-level system. Building on the assessment, the chapter highlights bottlenecks related to cooperation across levels of government, water planning, and basin management, and concludes with policy recommendations to better cope with water challenges in the face of climate change.

Water Governance in Argentina

Chapter 3. Water resources governance in Argentina

Abstract

The statistical data for Israel are supplied by and under the responsibility of the relevant Israeli authorities. The use of such data by the OECD is without prejudice to the status of the Golan Heights, East Jerusalem and Israeli settlements in the West Bank under the terms of international law.

Argentina’s climatic, hydrological and river basin system

Argentina is a large country with strong climate variability. The country extends longitudinally over 3 700 km and the continental portion of the territory is about 2 800 000 km² (around 5.5 times the size of Spain). The great latitudinal extension (between 22º and 55º south latitude) and the altimetry variation create wide climate variety from subtropical climates in the northern part of the country to the very cold weather in Patagonia. However, there is a predominance of mild climate in most of the country. When considering climatic and hydrological conditions, three regions can be identified in Argentina:

1. Humid region (Northeast, Litoral and the Pampa Húmeda region, the Tucuman Oranense Forest in the northwest and the Patagonian Andean Forests in the southwest): receives more than 800 mm/year of precipitation and occupies an area of 665 000 km² (24% of total country area). This region concentrates nearly 70% of the national population, 80% of agricultural production (essentially rainfed) and 85% of industrial activity.

2. Semi-arid region (central strip of the country north of the Colorado River): limited by the isohyets 500 mm to the west and 800 mm to the east, it occupies 405 000 km² (15% of total country area). The region concentrates 28% of the national population and irrigation is essential for the development of certain crops given the important water deficits during a large part of the year.

3. Arid region (most of the Northwest and central west of the country, the Patagonian Region and the Island of Tierra del Fuego): located to the west of the isohyet 500 mm up to near the foothills of the Andes mountain range, it occupies 61% of the country’s total area. The region concentrates only 6% of the population (density of 1.1 inhabitants/km²) and agricultural production is completely dependent on irrigation.

Argentina is a water-rich country with uneven distribution of water resources. Renewable resources in Argentina, accounting for long-term averages, are approximately 20 400 m3 per capita, which is above that of most OECD countries (Figure 3.1) and well above the water stress threshold defined by the United Nations Development Programme, as equivalent to 1 700 m3 per capita (MCTeIP, 2012). Around 76% of the national territory is subject to conditions of aridity or semi-aridity, with average rainfall of less than 800 mm per year. The Plate River Basin, which concentrates more than 85% of total national water resources, is the largest centre for human settlements, urban development and economic activity in the country. Outside the Sistema of La Plata, the most important rivers in Argentina are those that drain into the Atlantic Ocean (approx. 10% of total national resources), as they act as fluvial corridors of great economic and ecological importance. This is where the most important population settlements of the southern region of the country are located. The total contribution of the Atlantic slope, which includes the Cuenca del Plata, adds almost 95% of the total surface water supply of the country.

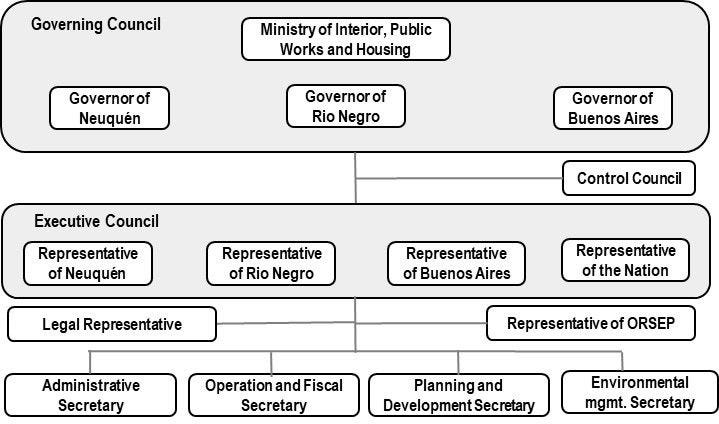

Figure 3.1. Total renewable freshwater resources per capita, long-term annual average values, 2014

Note: Data for Argentina for 2012.

Source: OECD (2015b), “Total renewable freshwater resources per capita, long-term annual average values”, in Environment at a Glance 2015, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264235199-graph23-en.

Legal framework for water resources management

National level

In 1994, Argentina underwent a constitutional reform that introduced an environmental provision (Article 124) acknowledging the historical right, whereby the 23 provinces and the Autonomous City of Buenos Aires own the water resources and have jurisdiction over them, including for interjurisdictional rivers. Their powers include policy making, policy implementation, operational management, financing and regulation. In practice, the national government can establish a national water policy, strategy, programme or plan, but needs the support of the provinces to implement it.

There is currently no water law or code at national level for water resources management or water services provision. The 2002 Law 25.688 “Regime of Environmental Management of Waters” created the interjurisdictional river basin committees to promote sustainable environmental management of inter-provincial river basins. This law was subject to numerous criticisms by most provincial water authorities. Provinces claimed that the law colluded with provincial competences that had not been delegated to the national government, such as river basin institutionalisation, management of natural resources, development of local institutions, and water planning and management (Pochat, 2005). Consequently, the 2002 law has not been fully enforced to date.

However, a plethora of laws in other sectors include water-related provisions (Box 3.1). The current national legislation is constituted by norms such as the Civil Code, the Commercial Code, the Mining Code, the Penal Code and other national laws related to energy, navigation, natural resources, etc., which contain provisions directly or indirectly related to water.

Box 3.1. Environmental laws concerning river basin management in Argentina

Law 25.688 “Regime of Environmental Management of Waters” (2002) establishes the minimum requirements for environmental preservation and use of water resources.

Law 25.675 “General Law of the Environment” (2002) establishes the minimum requirements for sustainable management of the environment and biodiversity preservation and protection.

Law 25.612 “Integral Management of Industrial and Services Waste” (2002) establishes the minimum requirements for sustainable management of all waste resources derived from industrial processes or service activities.

Law 25.831 “Free Access to Environmental Public Information” (2004) guarantees the right to access environmental information produced by national, provincial, and municipal governments, as well as from entities and companies (public, private or mixed) providing public services.

Law 25.916 “Management of Household Waste” (2004) establishes the minimum requirements for environmental protection with regards to household waste management.

Law 26.093 “Regime of Regulation and Promotion for the Sustainable Production and Use of Biofuels” (2006) establishes the normative framework for sustainable production and use of biofuels.

Law 26.331 “Minimum Budgets for Environmental Protection of Native Forests” (2007) establishes the minimum requirements for environmental protection of native forests.

Law 26.639 “Minimum Budgets for the Protection of Glaciers” (2010) establishes the minimum requirements for the preservation of glaciers and the periglacial environment.

In 2003, the 23 provinces, the Autonomous City of Buenos Aires and the national government signed a Federal Water Agreement that laid down the foundations of a national water policy. Through that agreement, the parties adopted 49 Guiding Principles for Water Policy, which acknowledge the value of water as a social and environmental resource for the society. The process to develop the 49 guiding principles involved about 3 000 participants through multiple workshops. The principles respect the historical importance of each jurisdiction and try to reconcile local, provincial and national interests. The principles call for the protection of the resource around the following building blocks: water cycle, water and the environment, water and society, water management, water institutions, water law, water economics, and water management tools. For example, some principles define the river basin as the appropriate scale for planning and managing water resources (No. 19) or call for long-term planning (No. 20) (COHIFE, 2003).

Sixteen years later, there has been some progress in making the principles operative, but important challenges remain. They include, among others, interjurisdictional conflicts over waters; planning focuses mainly on the delivery of hard infrastructure (and long-term planning is the exception rather than the rule, as planning is often ad hoc or short term); or discretional investments carried out with no evidence-based decision support system.

Provincial level

To date, all provinces have set their own water codes or laws (Table 3.1). The evolution of the provincial legal framework has gone through different periods (Pochat, 2005):

The first provincial water law was passed by the province of Mendoza in 1884. In this semi-arid province, the law established the General Irrigation Department (DGI), an autarkic institution with water police power, which should ensure irrigators’ participation in water management decisions. This law was an exception in the country landscape. In other provinces, without specific water laws, references to water were scattered throughout rural codes or other laws in topics such as drainage, sanitation works, construction of irrigation systems, etc.

1940s-1960s: Several water laws were passed in different provinces (e.g. Jujuy or Santiago del Estero). They included the definitions of public and private water sources, surface and groundwater, water quality, police power, and concessions of use of water resources, etc.

In the 1970s, more complex water codes were passed in the provinces of Córdoba, La Pampa, La Rioja, San Juan and San Luis. These codes included principles for water policy and established institutions with an interdisciplinary approach. They also introduced economic concepts such as valuing water.

1990s Water laws started to consider water as a resource of the wider natural environment (e.g. Water Code of the province of Buenos Aires, in 1999). These laws included concepts such as water policy and planning, water disasters, water risk, environmental impact, business concessions for works and services related to water, water registers, flexible water allocation regimes, river basin committees, protection of surface and groundwater sources, and river basins as a planning unit.

2000s onwards: Following the Federal Water Agreement (2003), the remaining provinces without a water code/law passed their own legislations as was the case for the provinces of Santa Fe and Tierra del Fuego.

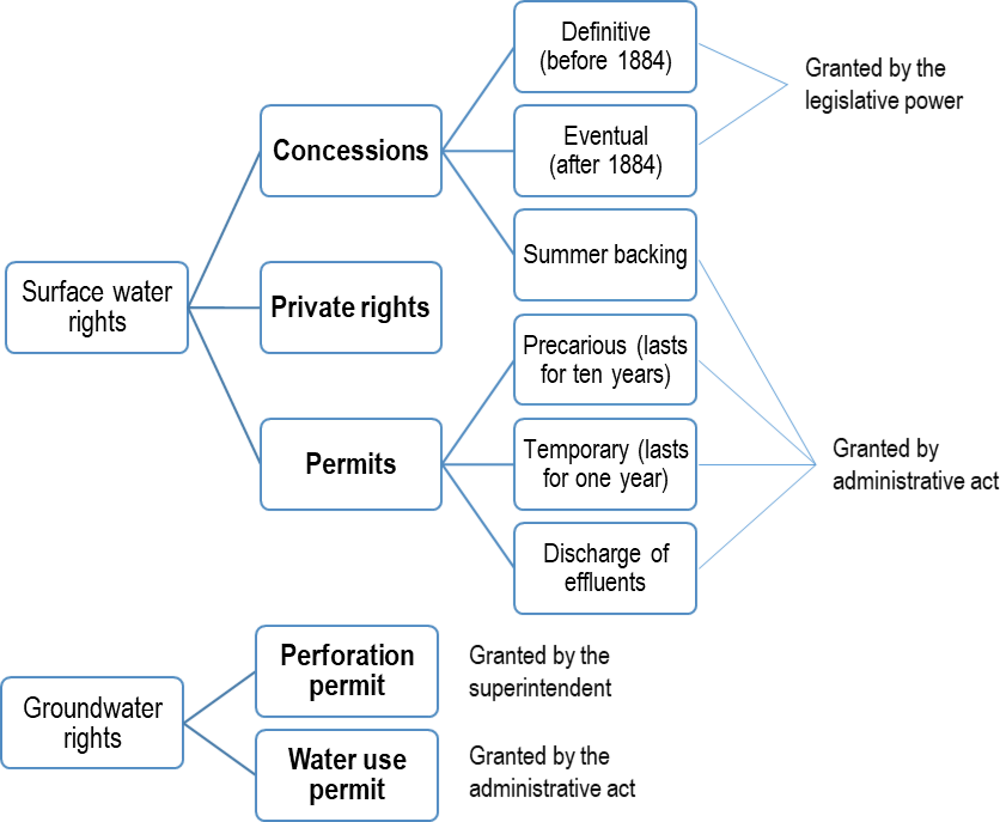

Legal frameworks for water resources management vary widely across provinces (Bergez, 2008) (Foro Argentino del Agua/SIPH, 2017) (Table 3.1). Some provinces have well-developed legislations while others do not regulate important aspects such as irrigation systems, users organisations, water rights nor enforce the polluter-pays or user-pays principles (FADA-IARH, 2015). To date, seven provinces do not have legal provisions for conjunctive management of surface and groundwater resources.

Overall, few provincial water laws refer explicitly to river basin management as a concept and appropriate scale. The Water Code of the Province of Buenos Aires (Law No. 12.257) has a full provision on basin committees and consortiums. In Santa Fe, Law 9.830 (1986) authorises “the establishment of basin committees that will act as legal entities under public law”, while in Chubut, Law 5.178 states that the executive power will establish and operate management units in river basins of its jurisdiction.

Table 3.1. Water laws and codes in Argentinian provinces

|

Province |

Year |

Water law/code |

Groundwater article |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Buenos Aires |

1999 |

12.257 – Water Code |

Arts. 82-89 |

|

Catamarca |

1973 |

2.577 – General Water Law (Legislative Decree) |

Arts. 13, 193, 195, 197, 199 |

|

Chaco |

1986 |

3.230 – Water Code |

Chapter 6 (Arts. 44-57) |

|

Chubut |

1996 |

4.148 – Water Code (Legislative Decree) |

- |

|

City of Buenos Aires |

2009 |

3.295 – Water Code |

- |

|

Córdoba |

1973 |

5.589 – Water Code (Legislative Decree) |

Arts. 19, 132, 160-162, 175 |

|

Corrientes |

2001 |

191/01 – Water Code |

Chapter 6 (Arts. 42-55) |

|

Entre Ríos |

1998 |

4 9.172 – Water Law |

Chapter 11 (Arts. 36-37) |

|

Formosa |

1997 |

1.246 – Water Code |

Title 8 (Arts. 184-222) |

|

Jujuy |

1950 |

161 – Water Code |

Art. 82 |

|

La Pampa |

2010 |

2.581 – Water Code |

Title 3, Chapter 9 (Arts. 44-60) |

|

La Rioja |

1983 |

4.295 – Water Code |

Title 6 (Arts. 162-185) |

|

Mendoza |

1884 |

General Water Law of Mendoza |

- |

|

Misiones |

1983 |

1.838 – Water Code |

Chapter 7 (Arts. 98-106) |

|

Neuquén |

1976 |

899 – Water Code (law) |

Title 6 (Arts. 59-79) |

|

Río Negro |

1995 |

2.952 – Water Code |

Title 5, Chapter I (Arts. 123-153) |

|

Salta |

1946 |

7.017 – Water Code (law) |

Chapter 7 (Arts. 140-158) |

|

San Juan |

1997 |

4.392 – Water Code |

Title 2 (Arts. 165-196) |

|

San Luis |

2004 |

5.122 – Water Law |

Title 4 (Arts. 95-112) |

|

Santa Cruz |

1982 |

1.451 – Water Code |

Chapter 8 (Arts. 74-84) |

|

Santa Fe |

2017 |

13.740 – Water Law |

- |

|

Santiago del Estero |

1950 |

4.869 – Water Code (law) |

Arts. 158-170 |

|

Tierra del Fuego |

2016 |

1.126 – Water Code |

Title 8 (Arts. 77-81) |

|

Tucumán |

2001 |

7.139 – Water Law |

- |

Source: OECD Questionnaire.

Institutional framework

National level

The Secretariat of Infrastructure and Water Policy (Secretaría de Infraestructura y Política Hídrica, SIPH), created in 2018 within the Ministry of Interior, Public Works and Housing, is the lead institution for water policy at the national level (see Chapter 2). The change from Undersecretary to Secretary of the SIPH somewhat testifies to the higher rank of water in the political agenda. Until the new structure of the SIPH in 2018, the Undersecretariat of Water Resources was responsible for water resources management at the national level. In addition to its leadership in national planning and investment related to water policy and infrastructure, the SIPH represents the national government in interjurisdictional river basin committees.

The Federal Water Resources Council (Consejo Hidrico Federal, COHIFE) was created in 2003 to promote a coherent implementation of the vision set in the 2003 Federal Water Agreement. COHIFE is made up of the SIPH and representatives from the ministries/ secretariats/authorities in charge of water resources of the 23 provinces and the Autonomous City of Buenos Aires. COHIFE’s role is to provide a platform to exchange ideas and experiences, in particular between provinces that are not part of a same river basin.

The Secretariat of Environment and Sustainable Development (Secretaría de Ambiente y Desarrollo Sustentable, SAyDS) (within the General Secretariat of the Presidency) is the responsible authority for environmental policy at the national level. The SAyDS’ main responsibilities include strategy and planning to ensure environmental preservation and protection, promoting sustainable development through the rational use of natural resources, and climate change adaptation and mitigation.

There are many other national agencies with water resources competences. For instance, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs represents Argentina in transboundary river basins institutions, the Ministry of Production and Labour leads the implementation of programmes to develop sustainable irrigation practices, the Ministry of Security deals with disaster risk management, or the Ministry of Energy leads hydroelectric power.

Interjurisdictional level

The role of interjurisdictional river basin committees is to provide a space to promote a common vision on water resources management and negotiate agreements across provinces on shared rivers to prioritise actions. In total, there are 16 interjurisdictional river basin committees in Argentina. When conflicts between provinces cannot be resolved, COHIFE may act as a mediating body to facilitate agreements (COHIFE, 2006). The Supreme Court of Justice is the official channel to settle conflicts.

The functions of an interjurisdictional river basin committee are granted by the provinces that establish the committee and, generally, with the endorsement of the national government. Therefore, functions can vary from one committee to another (Table 3.2). In addition to conflict management, the following four interjurisdictional river basin committees have water resources management competences, such as the operation of reservoirs, control of water quality or early warning systems for water-related disasters:

1. Interjurisdictional Committee of the Colorado River (Comité Interjurisdiccional del Río Colorado, COIRCO): Created in 1976, this committee has representation from the provinces of Buenos Aires, Mendoza, Neuquén, La Pampa and Río Negro, and from the national government. Its main role is to implement sustainable irrigation programmes in the basin. Throughout the years, the committee’s powers have been extended to water resources planning, environmental control, public water dominion definition, construction, operation and maintenance of dams. COIRCO also enforces water management and environmental standards for dams in the basin.

2. Regional Commission of the Bermejo River (Comisión Regional del Río Bermejo, COREBE): Created in 1981, this commission has representation from the provinces of Chaco, Formosa, Jujuy, Salta, Santa Fe, Santiago del Estero and the national government. COREBE’s main objective is to achieve integrated water resources management in the basin. It also has international agreements with the Regional Development Corporation of Tarija (the Plurinational State of Bolivia) to manage water resources in the upper basin of the Bermejo River and of the Rio Grande de Tarija.

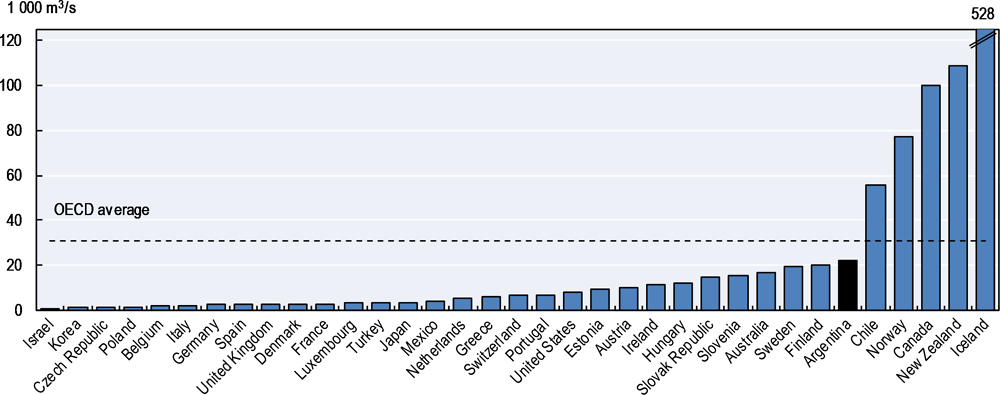

3. Interjurisdictional Authority of the Limay, Neuquén and Negro River Basins (Autoridad Interjurisdiccional de las Cuencas de los ríos Limay, Neuquén y Negro, AIC): Created in 1985 after a federal pact between the provinces of Buenos Aires, Neuquén, Río Negro and the national government, which was ratified in three provincial laws in 1986 and in a national law in 1990. The key objective of the authority is to promote the sustainable use of water resources in the basin. The authority manages concession contracts related to hydroelectricity; enforces water management, environmental and dam safety regulations; co‑ordinates the use of water resources by each of the provinces; monitors water quality; and produces climate, hydrological and environmental data.

4. La Picasa Lagoon Basin Committee (Comisión Interjurisdiccional de la laguna La Picasa, CILP) was created by the provinces of Buenos Aires, Córdoba and Santa Fe in 1999 to jointly face the challenges posed by the unprecedented growth of water height in the lagoon (due to more overflows from agricultural activities in the three provinces). In 2016, the committee was formally established and, besides the three provinces, the SIPH also participates in the committee. The SIPH has promoted the construction of infrastructure and the establishment of a water quality monitoring system. The committee has achieved important milestones, such as the agreement to conduct a water transfer to the Salado River Basin in the province of Buenos Aires to reduce the risk of uncontrollable overflows of the lagoon. However, remaining challenges persist in mitigating conflicts across the provinces.

Table 3.2. Interjurisdictional river basin committees in Argentina

|

Role |

Name of the committee |

Provinces |

Year |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Deliberative, consultative |

Inter-provincial Commission of the Lower Atuel (CIAI) |

La Pampa, Mendoza and the national government |

2017 |

|

Interjurisdictional Commission of the Arroyo Medrano Basin (CICAM) |

Autonomous City of Buenos Aires, Buenos Aires and the national government |

2016 |

|

|

Interjurisdictional Organisation of the Senguerr River Basin (SENGUERR) |

Chubut and Santa Cruz |

2006 |

|

|

Interjurisdictional Committee of the Chubut River Basin (COIRCHU) |

Chubut, Río Negro and the national government |

2004 |

|

|

Decision making; deliberative, consultative |

Interjurisdictional Committee of the Vila-Cululú and Northeast Stream Basin of the Province of Córdoba (CAVICU) |

Córdoba, Santa Fe and the national government |

2018 |

|

Interjurisdictional Committee of the Submeridional Lowlands (CIRHBAS) |

Chaco, Santa Fe, Santiago del Estero and the national government |

2018 |

|

|

Interjurisdictional Commission of the La Picasa Basin (CICL) |

Buenos Aires, Còrdoba, Santa Fe and the national government |

2016 |

|

|

Interjurisdictional Committee of the Hydrological Region of the Northwest of the Pampas Plain (CIRHNOP) |

Buenos Aires, Còrdoba, La Pampa, Santa Fe and the national government |

2016 |

|

|

Interjurisdictional Commission for the Carcarañá River Basin (CIRC) |

Córdoba, Santa Fe and the national government |

2016 |

|

|

Monitoring Commission of the Water Region of the Desaguadero River (DESAGUADERO) |

Buenos Aires, La Pampa, La Rioja, Mendoza, Neuquén, Rio Negro, San Juan, San Luis and the national government |

2010 |

|

|

Interjurisdictional Committee of the Pilcomayo River Basin (National) (PILCOMAYO) |

Formosa, Jujuy, Salta and the national government |

2008 |

|

|

Río Azul River Basin Authority (ACRA) |

Chubut and Río Negro |

1997 |

|

|

Juramento River Basin Committee – Salado (JURAMENTO) |

Catamarca, Salta, Santa Fe, Santiago del Estero, Tucumán and the national government |

1972 |

|

|

Interjurisdictional Committee of the Sali Dulce Basin (SALI DULCE) |

Catamarca, Córdoba, Salta, Santiago del Estero, Tucumán and the national government |

1971 |

|

|

Decision making; deliberative, consultative |

Interjurisdictional Authority of the Limay, Neuquén and Negro River Basins (AIC) |

Buenos Aires, Neuquén, Río Negro and the national government |

1985 |

|

Regional Committee of the Bermejo River (COREBE) |

Chaco, Formosa, Jujuy, Salta, Santa Fe, Santiago del Estero and the national government |

1981 |

|

|

Interjurisdictional Committee of the Colorado River (COIRCO) |

Buenos Aires, La Pampa, Mendoza, Neuquén, Río Negro and the national government |

1957 |

Notes: Role: decision making (decisions on water resources management are taken within the river basin organisation), deliberative (deliberates on water policy and issues recommendations for action), consultative (decisions are consulted with the river basin organisation), executive (executes the mandate of provinces or the national government).

Sources: OECD Questionnaire.

The financial and staff capacity of interjurisdictional committees also vary across provinces. COIRCO, COREBE and AIC have their own legal status and budget for operational, managerial, technical and administrative personnel costs. In the case of the La Picasa Lagoon Basin Committee, the national government funds the committee’s activities, including the development of infrastructure. The other committees do not have a legal status nor a dedicated budget for their activities and function in a similar manner to the CILP. Staff working in the committees are often officials from provincial governments, and financial resources to sustain the committee’s activities come from diverse sources, including the provinces, the national government or international co-operation (development banks).

Provincial level

There are a plethora of water authorities at the provincial level, including ministries, secretariats, undersecretariats, directorates, authorities, departments and institutes (Table 3.3).

Table 3.3. Subnational authorities in charge of water resources management in Argentina

|

Province |

Institution |

Autarkic (Yes/no) |

|---|---|---|

|

Buenos Aires |

Water Authority |

No |

|

Catamarca |

Secretariat of Water Resources (MOySP) |

No |

|

Chaco |

Provincial Water Administration |

No |

|

Chubut |

Provincial Water Institute |

No |

|

Córdoba |

Ministry of Water, Environment and Energy |

No |

|

Corrientes |

Institute of Water and Environment of Corrientes |

Yes |

|

Entre Ríos |

Ministry of Planning, Infrastructure and Services |

No |

|

Formosa |

Provincial Unit for Water Co-ordination |

No |

|

Jujuy |

Ministry of Infrastructure, Public Services, Land and Housing |

No |

|

La Pampa |

Secretariat of Water Resources |

No |

|

La Rioja |

La Rioja Provincial Water Institute (IPALAR) |

Yes |

|

Mendoza |

General Department of Irrigation |

Yes |

|

Misiones |

Water and Sanitation Institute of Misiones |

Yes |

|

Neuquén |

Undersecretariat of Water Resources |

No |

|

Río Negro |

Provincial Water Department |

No |

|

Salta |

Ministry of Environment and Sustainable Production |

No |

|

San Juan |

Hydraulic Department of San Juan |

No |

|

San Luis |

San Luis Agua S.E. |

No |

|

Santa Cruz |

Ministry of Economy and Public Works |

No |

|

Santa Fe |

Ministry of Infrastructure and Transport |

No |

|

Santiago del Estero |

Ministry of Water and the Environment |

No |

|

Tierra del Fuego |

Secretariat of Environment, Sustainable Development and Climate Change |

No |

|

Tucumán |

Water Resources Directorate of Tucumán |

No |

Source: COHIFE (2019), “Representantes jurisdiccionales”, www.cohife.org/s52/representantes-fundacionales (accessed in June 2019).

At the provincial level, two basic institutional frameworks can be observed for water resources management:

1. Centralised administration: In such situations, the key institution with water responsibilities is dependent of the provincial government. In the majority of provinces, the institution in charge of the water portfolio is the line ministry or secretariat within the government.

2. Decentralised management: In some provinces, the lead institution for water resources management enjoys significant independence from the government. This is the case of Mendoza for instance, where the General Irrigation Department (DGI) is institutionally and financially independent from the provincial government. Among others, the DGI plans and implements allocation regimes, controls and administers water concessions for different uses (a large part of water rights are for agricultural use), and collects water charges. According to their water law, other provinces with autarkic institutions in charge of water resources management are Corrientes, La Rioja and Misiones.

A few provinces, such as Chubut and Santa Fe, have provincial river basin committees and others provinces have created more ad hoc river basin committees such as the Committee for the Sustainable Development of the San Roque Lake Basin, constituted in the province of Córdoba to deal with a water pollution issue.

Metropolitan level

Argentina has 92% of its population living in urban areas (higher than the Latin American region average of 80.2%). The Metropolitan Area of Buenos Aires hosts more than 37% of the total population, followed by large cities with more than 1 million inhabitants (Córdoba, Mendoza, Rosario and Tucumán) and 34 cities with a population between 100 000 and 1 million inhabitants.

Key urban water management challenges include:

Geographic location: The geographic position of cities determines the main challenges they are exposed to as well as their capacity to respond due to possible physical constraints. In Argentina, delta cities, such as the Metropolitan Area of Buenos Aires (AMBA) face different water-related risks than those located in mountainous dry areas (e.g. city of Mendoza). For instance, the AMBA must deal with flood risks while in Mendoza scarcity is the most pressing water challenge.

Size: Large water demands in metropolitan areas can have an impact on water quality and quantity. For instance, in the Matanza-Riachuelo and Reconquista Basin located within the AMBA, water quality has been impaired by lack of access to sanitation services as well as industrial activities generating water pollution. Another well-known case of water pollution located near a large urban area is the Salí-Dulce Basin in the province of Tucuman.

Spatial organisation has an impact on water consumption trends and infrastructure development. Urban sprawl is high in Argentinian agglomerations. According to the inter-census data for 2001 and 2010, a higher density loss was identified for the most fragmented agglomerations, i.e. in those with a larger number of municipalities (National Presidency Report, 2017). Urban sprawl puts greater pressure on the environment than compact cities, due to land-use stress, fragmentation of natural habitats and increasing air pollution emissions. As a result of poor urban planning, settlements are developed in areas with poor infrastructure conditions or which are highly vulnerable to floods. This is the case of the metropolitan area of Córdoba, where the lack of proper water infrastructure results in turn in a higher impact on water quality that altogether brings the city into a downward spiral of environmental quality

Demographic dynamics affect water demand and supply and can challenge the capacity of local governments to meet increasing demands for water and sanitation services. In Argentina, informal housing settlements for low-income households raise particular challenges, reinforcing the growth of precarious areas in places that already have limited access to basic infrastructure. The National Registry of Disfavoured Neighbourhoods (RENABAP) estimates that 4 million people currently live in more than 4 400 precarious settlements, which often lack access to water or basic services and have no property rights.

The last 15 years have seen the establishment of four basin committees to manage urban water risks in the Metropolitan Area of Buenos Aires:

1. Committee of the Reconquista River Basin (COMIREC) was created in 2001 (Law 12.653) to manage water pollution risks in the Reconquista River Basin, which covers 1 700 km2 including 18 municipalities of the AMBA. Among others, the Reconquista River is the second most polluted river in Argentina, registering high levels of heavy metals and pathogenic microorganisms, due to poor industrial wastewater treatment. COMIREC has legal capacity to plan, co-ordinate, execute and control aspects related to basin management.

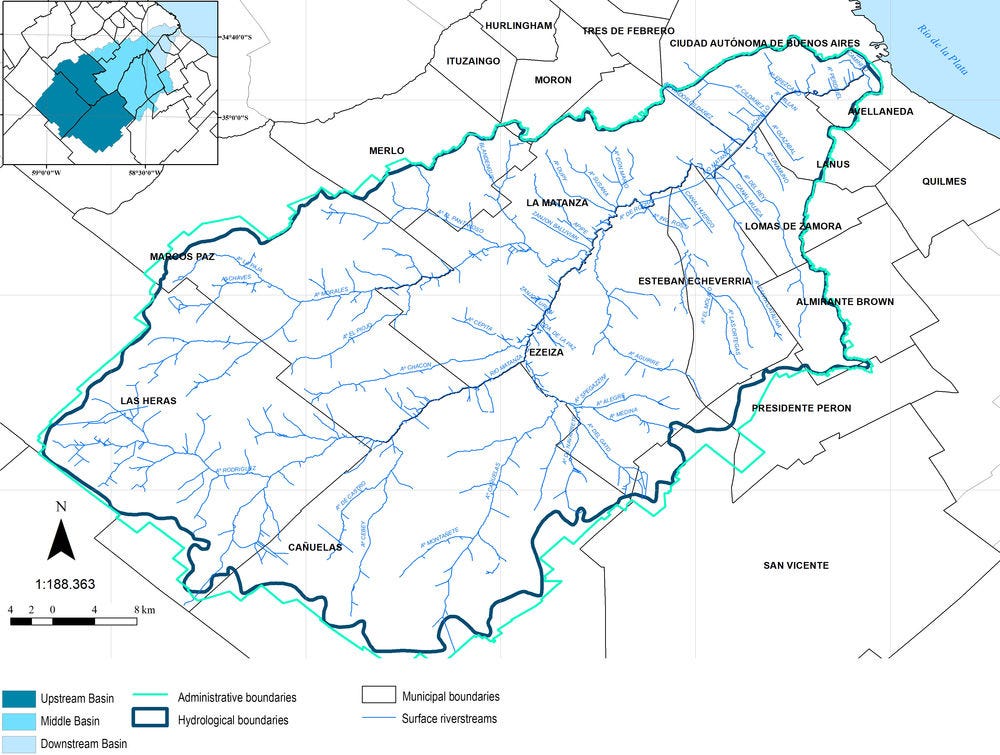

2. Matanza Riachuelo Basin Authority (ACUMAR): The most well-known case in Argentina of a river basin approach to manage urban water risks is located in the Matanza-Riachuelo River Basin (Figure 3.2). The Matanza-Riachuelo River Basin has been suffering from a long-standing severe water pollution problem. Around 80% of pollution comes from untreated wastewater of urban households, while 20% is from industrial activities (ACUMAR, 2019). ACUMAR was created in 2006 (Law 26.168) in response to the worrying situation of environmental deterioration. It is an autonomous, self-governing and interjurisdictional entity (national government, province of Buenos Aires and Autonomous City of Buenos Aires). In 2008, the Supreme Court of Justice of the Nation urged ACUMAR to implement a sanitation plan in response to the legal case known as “Causa Mendoza”, a claim filed in 2004 by a group of neighbours (Box 3.2). Launched in 2009 (and updated in 2016), the Comprehensive Environmental Sanitation Plan (Plan Integral de Saneamiento Ambiental, PISA) guides the activities of ACUMAR. PISA is organised around 14 action lines that compile projects in the AMBA to control, prevent and manage environmental degradation. Despite improvements in the past years, the basin has not achieved yet established water quality and ecosystems biodiversity goals.

3. Interjurisdictional Commission of the Arroyo Medrano Basin (CICAM): The Arroyo Medrano Basin cuts across the administrative boundaries of the Autonomous City of Buenos Aires and the municipalities of San Martín, Tres de Febrero and Vicente López in the province of Buenos Aires. Numerous floods throughout the years, some of them with important consequences such as the flood in April 2013 which killed eight people, have triggered the creation of the CICAM. The commission was created in 2016 and is comprised of the Autonomous City of Buenos Aires, the province of Buenos Aires and the national government, to reduce the impact of floods in the basin.

4. Committee of the Lujan River Basin (COMILU) was created in 2016 (Law 14.817) mainly to mitigate the serious consequences of floods of the Lujan River Basin in the AMBA. The Luján River Basin is one of the most populous, with an area of 2 690 km2, and partially crosses 15 municipalities of the Metropolitan Area of Buenos Aires (Campana, Chacabuco, Escobar, Exaltación de la Cruz, General Rodríguez, José C. Paz, Luján, Malvinas Argentinas, Mercedes, Moreno, Pilar, San Andrés de Giles, San Fernando, Suipacha, Tigre). COMILU’s main responsibilities are territorial and environmental planning, and control of clandestine channels and pollution of the basin.

Box 3.2. The judicial case of the Matanza Riachuelo (The “Mendoza Case”)

The Matanza Riachuelo Basin, located in the Metropolitan Area of Buenos Aires, is the largest most polluted basin in Argentina. It covers the southern part of the Autonomous City of Buenos Aires and 14 municipalities of the province of Buenos Aires (see Figure 3.2). Although the pollution issue dates back to the industrial development of the Metropolitan Area of Buenos Aires, it was in the last decades that it gained political and media visibility.

In 2004, residents of the neighbourhood of Avellaneda filed a lawsuit about the environmental deterioration of the basin, based on the right to a healthy environment established in Article 41 of the national Constitution. The claim took legal-institutional viability when, in 2006, the Supreme Court of Justice of the Nation declared its competence in the matter. The court dictated that the state has the obligation to restore the environmental damage caused to the ecosystems as well as to prevent future damage. The three administrations with jurisdiction in the area (national government, province of Buenos Aires and the Autonomous City of Buenos Aires) were thus required to design an Integral Plan for Environmental Sanitation of the basin. The Matanza Riachuelo Basin Authority (ACUMAR) was created to design such a plan. Since 2008, several advances have been achieved (cleaning of margins and waste dumps, eliminating towpaths, controlling industrial pollution, etc.), although serious challenges still persist to achieve the full environmental recovery of the basin.

Figure 3.2. The Matanza-Riachuelo river basin

Source: ACUMAR (2019a), “Mapas de la cuenca”, www.acumar.gob.ar/institucional/mapa (accessed in June 2019); ACUMAR (2019b), “Institucional”, http://www.acumar.gob.ar/institucional/ (accessed in June 2019).

International level

Argentina shares water resources with its neighbouring countries (Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Paraguay and Uruguay), with varying institutional arrangements:

Institutions established to manage water at basin or sub-basin level: Intergovernmental Co-ordinating Committee of the Plata Basin (Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Paraguay and Uruguay), Binational Administrative Commission of the Lower Basin of the Pilcomayo River (Argentina and Paraguay), Binational Commission for the Development of the Upper Bermejo River Basin and the Rio Grande de Tarija (Argentina and Bolivia), Trinational Commission for the Development of the Basin of the Pilcomayo River (Argentina, Bolivia and Paraguay).

Institutions established to manage water in some river sections: Administrative Commission of the Plata River (Argentina and Uruguay), Mixed Technical Commission of the Maritime Front (Argentina and Uruguay), Administrative Commission of the Uruguay River (Argentina and Uruguay), Argentine-Paraguayan Joint Commission of the Paraná River (Argentina and Paraguay).

Institutions established to manage one issue or project: large multi-purpose reservoir, such as Mixed Technical Commission of Salto Grande (Argentina and Uruguay) and Yacyretá Binational Entity (Argentina and Paraguay); or navigation such as the Intergovernmental Committee of the Paraguay-Paraná Waterway (Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Paraguay and Uruguay).

Argentine-Chilean Working Group on Shared Water Resources, which is responsible for inventorying and planning tasks for shared water resources.

Provinces and the national level should agree on or coordinate actions in international committees (e.g. signature of agreements or other negotiations), which will have an impact at subnational level. Provinces and the national level should therefore define consultation mechanisms that help establish a common federal position in international committees.

Water resources governance challenges

Fragmentation of roles and responsibilities

As in many countries, water resources governance in Argentina is scattered across ministries, public agencies and levels of government. There is no national water authority or equivalent concentrating most water-related competences. In the absence of effective co-ordination, silo approaches can result in incoherence between subnational policy needs and national policy initiatives, and deliver suboptimal outcomes. At the provincial level, the overlapping of competences with regards to water resources is also frequent and poses challenges for integrated water resources management (Berardo, Olivier and Meyer, 2013).

The absence of comprehensive legal frameworks at the national level does not help address this institutional complexity. Existing mechanisms to co-ordinate water resources policies across levels of government have not been effective. The Federal Water Resources Council (COHIFE), created in 2003 to promote a coherent implementation of the vision set in the Federal Water Agreement, has neither enforcement nor coercive powers. Moreover, COHIFE faces capacity challenges due to shortage of a dedicated secretariat (presidency rotates every year) and permanent technical staff. This can potentially undermine the continuity of knowledge-sharing activities as well as other initiatives undertaken by COHIFE.

Even when interjurisdictional river basin committees are in place, the fragmentation of competences, heterogeneity of water management capacity, and difficulties to reach agreements, have generated conflicts between provinces (Box 3.3). In Argentina, 90% of water availability is inter-provincial, which necessitates co-operation and co-ordination among provinces (Rodriguez and Dardis, 2011). The large heterogeneity of provincial water agencies’ technical and financial capacity makes inter-provincial management of water resources a complicated daunting task. There are cases such as the province of Mendoza, with a sophisticated framework of water regulations, while other provinces have only recently begun to develop their water management institutions, with many of them passing provincial water codes/laws in the last two decades. Moreover, there are cases where it is not optimal from an economic standpoint for the provincial authorities to co‑ordinate actions with other provinces. For instance, the province of Tucumán has historically avoided meaningful action to reduce water pollution in the Salí River produced by citrus and sugar cane farmers, who contribute greatly to the provincial economy. The river runs through Tucumán and then enters the provinces of Santiago del Estero and Córdoba, which have complained for decades about high pollution levels generated upstream (Berardo, Olivier and Meyer, 2013). Lastly, it is not clear whether COHIFE can serve as an effective platform to solve conflicts of a large magnitude. Despite the fact that one of its goals is to “become a mediating or arbitrating venue (when the parties in conflict request it) in all issues related to interjurisdictional waters”, conflicts have remained even after COHIFE established a voluntary mechanism to solve this type of conflict.

The interface between water resources at the river basin scale and land-use management is also highly fragmented. While provincial jurisdictions are in charge of regulating resources (water, mining, etc.), land regulation is under the exclusive responsibility of local governments. Because of the split of competences for water management and land use across provincial and municipal levels, there is a considerable spatial heterogeneity in terms of compliance and enforcement for two main reasons. First, land-use planning and management tools at local and provincial level are not widely used. In 2018, only 34% of local governments had territorial plans (National Presidency Report, 2017). Second, there is a mismatch in how water and territorial development are managed across multiple scales. There is an absence of provincial integrated land-use plans to guide municipal plans and that would factor in water resources.

Box 3.3. Water conflicts across jurisdictions in Argentina

Allocation regimes

The inter-provincial conflict between Mendoza and La Pampa over the Atuel River is an illustrative example of disputes over river allocation regimes. The Atuel flows from the southern area of the province of Mendoza (upstream user) into the northern section of the province of La Pampa (downstream user). Both provinces depend heavily on this body of water for the well-being of their economies largely made up by the agriculture and tourism industries, and struggle to find agreements on water allocation.

Flood management

The management of the La Picasa lagoon, which flows through the provinces of Buenos Aires, Córdoba and Santa Fe, has generated long-standing conflicts between these provinces since the 1990s. Land-use changes due to the growth of agricultural activities in the land surrounding the lagoon led to increased works by the different provinces to carry water from the lagoon into neighbouring land. Due to the uncoordinated nature of these works by different provincial authorities as well as clandestine channelling of water into private land, the lagoon ballooned in size as a result of increased drainage. It grew from 8 000 ha to approximately 35 000 ha, with the result of exceptional flooding in the surrounding provinces and the consequent destruction of crops and properties. Works conducted by the different provinces have also altered the natural regime of the basin systems, resulting in lawsuits among them. Even after the establishment of the La Picasa Lagoon Basin Committee, conflicts have continued to arise during times of flooding.

Water quality

The Salí-Dulce River Basin shared by the provinces of Santiago del Estero and Tucumán has created entrenched conflict between the two provinces. Human activity has caused massive pollution of surface water, in the form of waste from the sugar, paper, textile and mining industries; alcohol distillers; citrus and refrigeration activities; compounded with the generation of urban solid waste from neighbouring urban centres. The water from the Salí-Dulce River carries an elevated amount of organic matter into the Hondo River Reservoir, causing massive fish mortalities and the appearance of a large amount of algae. The resulting foul smell stemming from the decomposition of the detritus in the water negatively affects the tourism industry of the Hondo River, which is its main source of income. This situation motivated the creation of the Interjurisdictional Committee of the Salí-Dulce River Basin as a way to encourage co-operation, collaboration and co-ordination between the provinces that make up the basin and the national authorities involved in the matter.

Sources: Berardo, R., T. Olivier and M. Meyer (2013), “Adaptive governance and integrated water resources management in Argentina”, https://dx.doi.org/10.7564/13-IJWG9; SAyDS (2019), “Río Salí Dulce”, https://www.argentina.gob.ar/ambiente/agua/cuencas/salidulce (consulted in June 2019).

Weak water planning framework at all levels of government

National water-related planning focuses on infrastructure delivery

Policy objectives are weakly co-ordinated across the various national plans, but good co‑operation can be found at project level. The ethos of the National Water Plan (NWP) is to consider water as a key aspect for economic performance and to bridge social gaps through better access to services and infrastructure. Water resources preservation and ensuring projects respect environmental standards (namely, through environmental impact assessments) are key features of the implementation of the NWP. However, the NWP could also be more prominently linked to overall national environmental objectives. For instance, through a more systemic approach to water security looking at all water risks. Currently there is a strong focus on universal access to water services (Axis 1 of the NWP) and on managing floods and droughts risks (Axis 2 of the NWP), but no systemic approach to deal with risks related to the disruption of aquatic ecosystems. Similarly, the National Irrigation Plan aims to develop new irrigation systems and improve the efficiency of the irrigation sector, but also has limited connections to broader national environmental objectives. The Belgrano Plan focuses on delivering infrastructure in ten provinces in the north of the country, which together with the Metropolitan Area of Buenos Aires are home to the largest number of poor households in the country (Box 3.4). However, at project level there are examples of good co-operation across national level ministries and secretaries as well as with provinces. For instance, to define multi-purpose infrastructure developments, the National Directorate of Multipurpose Achievements is working jointly with the Secretariat of Energy; the Secretariat of Environment and Sustainable Development; the Secretariat of Agriculture, Livestock and Fisheries; and the Secretariat of Tourism. Through this co‑operation, the secretariats share the information they have on specific projects and help determine the socio-economic and environmental impacts of the project. This work is also closely co-ordinated with the provinces that will benefit from the investment.

Interjurisdictional river basin committees are still not equipped to operate as planning agencies

Where they exist, interjurisdictional river basin committees are still not equipped to operate as planning entities, with few exceptions. The NWP encourages the development of plans for interjurisdictional river basins and in shared basins with neighbouring countries. These plans identify, define and prioritise measures to solve specific problematics of the basin. However, they have been limited in scope, since they usually focus on individual projects to solve specific issues rather than seeking to align national and provincial policy priorities and objectives. The NWP aims to change the current project-based approach followed by the interjurisdictional river basin plans towards more systemic drought and flood management (i.e. plans that combine both structural and non-structural measures to deal with water risks). Moreover, most of the committees still do not have technical or financial capacity to develop or implement such plans, despite recent support by SIPH. Their main role has traditionally consisted of providing a space to negotiate agreements between provinces on interjurisdictional rivers. The objective of the current administration is to enlarge the role of the committees towards planning and management of water resources. For instance, AIC is one of the committees that has solid capacities on operational hydrology (flood forecasting, drought forecasting), hydrometeorological predictions, defining water quality standards, or inventorying water resources, among others, and that could become a planning entity.

Box 3.4. National water-related plans in Argentina

The National Water Plan (NWP), launched in 2016, set ambitious objectives to manage water risks and place water at the core of economic and social development. By 2023, the national government aims to increase coverage to 100% for drinking water supply and 75% for sewage connections. The NWP also aims to increase protection against floods and droughts through strategic actions that combine both hard infrastructure – such as building flood protection infrastructure in cities or increasing the number of dams – along with better early warning and information systems, including a network of meteorological double polarization radars (SINARAME). Finally, the NWP seeks to support the irrigation needs of the agricultural sector by expanding the cultivated area by 300 000 ha by 2022 (an increase of 17%). To achieve these objectives the plan set ambitious targets to deliver infrastructure projects through both public and private investment (see Box 2.). It also proposed implementing actions on four cross-sectoral axis:

Preservation of water resources, including mitigation and recovery of disrupted ecosystems, by ensuring infrastructure projects respect the natural environment

Capacity building: the Plan aims to develop knowledge and tools that help implement policies more effectively and efficiently

Advancing technological developments related to the preservation of the quality and quantity of water

Using the plan as an engagement mechanism through which perspectives and opinions of water stakeholders help choose the best solutions and investments to achieve the objectives of the plan.

The main goal of the National Irrigation Plan (NIP), developed by the Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock and Fisheries, is to promote sustainable development of irrigated agriculture throughout the country. The NIP aims to duplicate the current irrigated area to reach 4 million hectares by 2030 and to increase water efficiency for irrigation. For this purpose, the plan has seven specific action lines:

1. public and private institutions: strengthen the capacities of national and provincial public actors, as well as of irrigator organisations and private agents

2. education and training: train public and private agents in the design, implementation and management of policies required for the use, expansion, renovation and maintenance of the different irrigation systems

3. research and information: co-ordinate research conducted by different institutions on water resources use in irrigation, adapting agriculture to climate change, and technologies to improve irrigation

4. public investment: co-ordinate public investment on irrigation systems across national and provincial levels of government

5. financing: stimulate public and private financing to fund investments in the expansion and renewal of irrigation systems

6. environment: strengthen activities to increase environmental preservation, in particular by raising awareness for the need to preserve land and water to adapt to climate change

7. legislation: co-ordinate activities across national and provincial governments to establish a clear and homogenous legislative scheme of water use and ownership.

The Belgrano Plan, launched in 2015, seeks to compensate the historic lack of investments in the north of Argentina, promote productive development, combat drug trafficking and improve security. The plan focuses heavily on investment in large infrastructure projects (e.g. roads, railways, airports) as well as on promoting infrastructure for the production of renewable energies and gas. It also focuses on improving poor and remote neighbourhoods, including providing better water and sanitation services and street lighting, building decent housing (the plan proposes housing for over 250 000 families), providing childcare infrastructure and improving telecommunications. Total investment amounts to USD 16 billion over ten years. The water section of the Belgrano Plan focuses on water and sanitation services and is under the portfolio of the SIPH, which finances infrastructure through loans from multilateral banks (Inter-American Development Bank, the World Bank and the Development Bank of Latin America). In the last 3 years, 11 projects have been executed for a total of Argentinian pesos 6.5 billion.

Sources: SIPH (2016), “Plan Nacional de Agua”, Ministry of the Interior, Public Works and Housing, Buenos Aires, https://www.argentina.gob.ar/sites/default/files/2017-09-29_pna_version_final_baja_0.pdf. ; Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock and Fisheries (n.d.), “Plan Nacional de Riego”, https://www.agroindustria.gob.ar/sitio/areas/riego/plan_riego (consulted in June 2019); Chief of Cabinet (2019), “Unidad Plan Belgrano”, https://www.argentina.gob.ar/planbelgrano (consulted in June 2019).

Provincial water planning varies across jurisdictions

Provincial water plans are the exception rather than the rule in Argentina, and where they do exist, they usually have an exclusive infrastructure or sectoral focus. For instance, the province of Entre Rios has a Plan on Water Supply that focuses on expanding coverage of water services, but it does not address water resources management.

However, some provinces are well-advanced in developing long-term water planning linked to regional development objectives. For instance, in the province of San Luis, water features prominently in the strategic goal of the province. The Province of San Luis Water Plan 2012-2025 prompts the use of policy instruments to deal with water risks at provincial level. In particular, the plan is structured around six strategic axes: infrastructure, planning, monitoring, culture, quality and management (Province of San Luis, 2011).

Challenges to co-ordinate national, provincial and basin planning

There are multiple challenges to implementing the national plans, at the provincial level. These include the need of further engagement from the provinces in the design process; complex, multiple, and heterogeneous legal and institutional frameworks at subnational level; and difficulties in aligning political priorities across levels of government:

The design of national water-related plans could be better co-ordinated across levels of government. Provinces are not involved in the national planning process, which can lead to a lack of ownership over the goals, objectives and measures included in them. For instance, the design process of the NWP, the National Irrigation Plan (NIP) or the Belgrano Plan could have better engaged the provinces to target and align with their infrastructural capacities, needs and priorities.

Shifting policy priorities and agendas also challenge the possibility of aligning national and provincial planning. Provinces usually design their own portfolio of projects and seek national funding to implement them, although not necessarily always linked to national plans (even with the financial incentive of the national government to cover 67/70% of projects related to the NWP). The risk of overinvestment in large infrastructure often due to the lack of alignment of policy priorities across levels of government, should be contained by a systematic economic, social and environmental assessment of the proposed infrastructure developments. There are examples of projects delivered not because they will add the maximum value to the economy or close a large social divide, but because they are appealing in terms of their multi-level financial agreements.

Heterogeneous legal and institutional frameworks across provinces are also a source of complexity. For instance, ten provinces are expected to execute the Belgrano Plan water supply and sanitation infrastructure. In such cases, there are important differences in concession contracts to service providers (e.g. Córdoba, Corrientes, Misiones and Santiago del Estero have private operators, while other utilities in the country are publicly owned), and regulators for water supply and sanitation, which range from the existence of a dedicated multi-sectoral regulator in the cases of Catamarca, Formosa, Jujuy, Salta and Tucumán, to a series of provincial water and sanitation regulators for Chaco, Corrientes, Misiones and Santiago del Estero. Thus, ten very different water services governance models have to be taken into account to implement the Belgrano Plan.

Weak basin management practices

The general sense of water abundance in some basins in Argentina (e.g. La Plata Basin) does not help to fully engage all ministries and levels of government in the shift from crisis management to risk management. At metropolitan, provincial and interjurisdictional scale, basin management is reactive, remedial and unplanned, rather than proactive, pre-emptive and planned, with few exceptions. It also obscures problems of water pollution, demand, availability and conflicts. While basins are acknowledged as the appropriate scale for water management by the 2003 Federal Water Agreement, sound basin management is overall the exception rather than the rule in Argentina. In terms of water resources management, optimisation at the provincial level leads to suboptimal results, and can lead to serious maladaptation, thus failing to achieve or worsening water risks in the face of climate change in the medium to long term in the use of scarce (financial and water) resources, constraining economic growth and preventing efficiency gains.

Insufficient use of economic instruments

The use of economic instruments varies across jurisdictions: some provinces do not charge for bulk water withdrawal or for pollution; others charge according to the water use or the category of users; and some apply, to a certain extent, the polluter-pays principle. It is common to have tariffs for certain industrial uses such as petroleum activities, while other categories of users do not pay for water abstraction use and pollution. Irrigators pay a “canon” expressed in an annual fee per hectare, under the concept of water-land ownership.

The current, insufficient, level of implementation of economic instruments in Argentina (Foro Argentino del Agua/SIPH, 2017) does not promote the efficient use of water resources. In many cases, the level of tariffs or fees does not reflect the economic value of water, and the current system does not offer incentives to change behaviours, promote water use efficiency and better manage water demand. Water charges focus on recovering costs related to the activities required for water management, and are not designed to increase efficiency, improve equity in water use or reduce consumption. A cross-sectoral analysis of economic instruments in the city of Buenos Aires and the provinces of Buenos Aires, Córdoba, Corrientes, Entre Ríos, La Pampa and Santa Fe concluded that as they currently exist, economic instruments for water use do not encourage efficient use of water resources (Deraiopian, 2016). The analysis reveals, for example, that in the case of the province of Córdoba, the payments for water use are regressive (i.e. water users with higher volumetric consumption pay less per volume unit). It also reveals that, with the exception of the provinces of Buenos Aires and Córdoba and the city of Buenos Aires, economic instruments for water pollution lack a methodology for calculating tariffs. In fact, there are quite a few emblematic cases where the externalities associated with the use of water have resulted in grave environmental degradation, for example, groundwater (Puelches in Buenos Aires), rivers (Matanza Riachuelo River, in Buenos Aires, Salado in Santa Fe) or lakes (San Roque in Córdoba). Similar results were found in a similar exercise conducted by Padin Goodall (2015) between provinces located in the regions of Cuyo and Patagonia. This could be an indication that current use of economic instruments throughout Argentina is not fit-for-purpose (Andino, 2016).

Patchy and insufficient data and information

Water-related data are dispersed among a wide range of sources, which include the public sector (at national, provincial and municipal level), users associations, research institutions and others. Each province produces its own water-related data, and there is no formal requirement to share such data with the national government, nor a unified collection or monitoring system. Dispersion of data is resulting in a lack of basic water information at national and provincial level on indicators such as abstraction rate by water use at basin level or infrastructure maintenance data. Moreover, the quality of data collected can vary across provinces.

Important efforts are underway to harmonise data across levels of government, although there is still room for improvement (Foro Argentino del Agua/SIPH, 2017). The largest databank in relation to water resources management is the National Hydrological Network (RHN) established in 1907. The RHN is a nationwide database that incorporates data from the SIPH’s gauging stations as well as from other institutions that have adhered voluntarily to the database. Such institutions include national and provincial research institutes: National Institute for Water (Instituto Nacional del Agua, INA), National Technological Institute for Agriculture (Instituto Nacional de Tecnología Agropecuaria, INTA) and the Argentine Institute of Nivology, Glaciology and Environmental Sciences (Instituto Argentino de Nivología, Glaciología y Ciencias Ambientales, IANIGLA) (which operates under the umbrella of the National Scientific and Technical Research Council [CONICET], the National University of Cuyo and the Government of the Province of Mendoza). It also includes data from the provincial water authorities/departments Corrientes, Chaco, Entre Rios and Río Negro. The RHN is being modernised and expanded. It has incorporated new instruments and technology for the transmission of real-time data via cellular and satellite networks in 422 existing stations and the objective is to have more than 650 stations by 2023, of which more than 500 will transmit data several times a day. Once the expansion of the RHN is completed, it will provide a comprehensive inventory on water resources as well as real-time data and information.

However, in order to become a comprehensive information system on water resources, the RHN should be complemented with other types of data and information. First, there is a lack of data and information in a large number of domains. For instance, there is no information on which type of economic instruments exist at provincial level nor the levels of the tariff, no data on agricultural production or industrial activities and water use, no economic analysis on the impact of water-related decisions, etc. Second, it is difficult to find disaggregated data and information at different scales and levels of government (interjurisdictional basins, provinces, provincial basins and municipalities) and from different jurisdictions. Third, there is also a need to expand groundwater data and information availability (Foro Argentino del Agua/SIPH, 2017).

Stakeholder engagement

In general, water users are rather poorly engaged in the planning, management and control of water resources. When assessing stakeholder engagement mechanisms in Argentina against OECD standards (Box 3.5), several flaws can be observed. First, formal or informal mechanisms to engage stakeholders are not well-known among non-governmental actors (FADA-IARH, 2015). Second, in many instances, there is little political will to engage non-governmental actors in decision-making processes. For instance, although COHIFE provides a multi-level forum to help governmental representatives take decisions on water resources management issues, no mechanisms exist to involve non-governmental actors in decision making. Lastly, there is a lack of technical knowledge in non-governmental organisations with regards to rational and sustainable use of water resources (FADA-IARH, 2015).

When stakeholder engagement mechanisms do exist, they can be limited in scope and it is difficult to assess whether they are effectively delivering their functions. One of the few institutions that has a dedicated space to involve stakeholders in the decision-making process can be found in the province of Salta. The provincial water law passed in 1998 (Law 7.017) created the Provincial Water Council. The objective of this entity is to advise responsible public authorities on water resources planning and management. Five representatives from the agricultural sector, one from the industrial sector and one from the mining sector compose the council. The provincial application authority must gather the Provincial Water Council at least once a month to discuss and inform about water policy (Province of Salta, 1998). However, the scope of the Provincial Water Council seems somewhat limited. The province of Salta has around 1.3 million inhabitants and hosts one of the largest indigenous communities; however, households and indigenous groups do not have a seat in the council. Moreover, it is difficult to assess the accountability of the council’s activities. There are no public reporting systems on the council’s discussions, or on how inputs provided by stakeholders influenced the decision-making process.

Box 3.5. OECD stakeholder engagement in the water sector: Key principles

The OECD (2015a) proposes a set of key principles and a Checklist for Public Action, with indicators, international references and self-assessment questions that can help guide stakeholder engagement processes and identify areas for improvement. The key principles of this framework are:

Principle 1: Map all stakeholders who have a stake in the outcome or that are likely to be affected, as well as their responsibility, core motivations and interactions.

Principle 2: Define the ultimate line of decision making, the objectives of stakeholder engagement and the expected use of inputs.

Principle 3: Allocate proper financial and human resources and share needed information for result-oriented stakeholder engagement.

Principle 4: Regularly assess the process and outcomes of stakeholder engagement to learn, adjust and improve accordingly.

Principle 5: Embed engagement processes in clear legal and policy frameworks, organisational structures/principles and responsible authorities.

Principle 6: Customise the type and level of engagement to the needs and keep the process flexible to changing circumstances.

Source: OECD (2015a), Stakeholder Engagement for Inclusive Water Governance, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264231122-en.

Policy recommendations

While the 2003 Federal Water Agreement recognises the role of water as a driver for sustainable development, the underpinning institutional, policy, regulatory and operational architecture is not necessarily set to support that intended outcome. There is room to strengthen the current water resources governance framework to better cope with water challenges in the face of climate change.

Rejuvenate the Federal Water Agreement to improve water resources governance

The 2003 Federal Water Agreement was a significant step towards strengthening water resources governance. It acknowledged the need for flexibility and context-specific solutions in a diverse federal country such as Argentina, and introduced topics that were until then often overlooked, such as basin management, the economic value of water, interdependence of water and the environment, or long-term planning.

Argentina should work towards a rejuvenated agreement or pact (see recommendation in Chapter 2) across national and provincial levels to enhance water resources governance. A rejuvenated agreement could help overcome the mistaken idea that Argentina is in a deadlock with respect to water resources governance due to its federal system and related complexity for multi-level governance. Federalism precisely is an opportunity and offers strong potential for multi-level partnerships to deal with water challenges at all appropriate levels of government in a shared responsibility.

There are three key priorities that provinces and the national government should aim to advance in a rejuvenated federal agreement:

1. Establishing a multi-level water planning framework that helps align national and provincial priorities, and provides a uniform unit of analysis and methodology for the development of plans. Planning can be a powerful co-ordinating vehicle across ministries and levels of government, but its potential has not been fully exploited in Argentina.

2. Strengthening existing basin governance arrangements to tackle water issues at the right scale. Water conflicts across provincial jurisdictions prevail even with the creation of 16 interjurisdictional basin committees and the explicit reference to interjurisdictional management of waters in the Federal Water Agreement.

3. Improving basin management practices. Argentina should support effective basin management practices, in particular on three fronts: 1) economic instruments; 2) data and information systems; and 3) stakeholder engagement.

Establish multi-level water planning framework for Argentina

Argentina should establish a comprehensive, effective and efficient long-term planning framework at all levels of government to address issues of federative management, and factor in both short-term considerations (economic, social and environmental performance) and long-term projected impacts (e.g. climate change, population growth). Plans should have a different focus depending on the level of government (national, interjurisdictional, provincial).

National planning should link water policy and the country’s broader development strategy and set clear targets on allocation regimes, water entitlements and infrastructure development. While the NWP takes stock of necessary actions in Argentina to promote economic development and close social gaps and acknowledges the need to preserve water resources, it does not relate sufficiently to the overall environmental and other water-related sectors’ policy objectives.

Interjurisdictional basin planning should set targets for allocation regimes and environmental flows and the level of the tariff of economic instruments, among others, to foster co-operation and alignment of provincial priorities across the river basin.

Provincial planning should tailor national priorities to the territorial specificities, link water planning to the broader regional development strategy, and put in place policy tools to achieve the objectives set: deciding on allocation regimes (water uses), developing a project portfolio, setting the level of tariffs, etc.

Box 3.6. California’s Water Plan, building a shared vision for the future

The California Water Plan is the state’s strategic plan for sustainably managing and developing water resources for current and future generations. The water plan is much more than a document as it provides a forum for elected officials, agencies, California Native American tribes, resource managers, businesses, academia, stakeholders and the public to collaboratively develop findings and recommendations that inform decisions about water policies, actions and investments. The California Water Plan is a key tool for strengthening these partnerships.

Perhaps most importantly, Update 2018 (the 12th in a series of such plans since 1957) prioritises supporting local and regional efforts to build water supply resilience across California. This approach recognises that different regions of the state face different challenges and opportunities, yet all benefit from co-ordinated state support. In April 2019, Governor Newsom signed an executive order calling for state agencies to work together to form a comprehensive strategy for building climate-resilient water systems through the 21st century. Update 2018 is timely as most of the content in the plan can inform this work.A shared vision for California’s water future

Update 2018 presents a vision where all Californians benefit from such desirable conditions as reduced flood risk, more reliable water supplies, reduced groundwater depletion, and greater habitat and species resiliency – all for a more sustainable future. Planning and policy priorities will have a mutual understanding of resource limitations, management deficiencies and shared intent, with a focus on sustainability and actions that result in greater public health and safety; healthy economy; ecosystem vitality; and cultural, spiritual, recreational and aesthetic experiences.

In this vision, investments result in intended outcomes through the application of adaptive management by first focusing and agreeing on the end in mind, then recommending and implementing actions. Learning and adaptation cycles strengthen decision making, maximise return on investment and support proactive management.

Operational definition of sustainability

Update 2018 provides an operational definition of sustainability. Sustainability of California’s water systems means meeting current needs – expressed by water stakeholders as public health and safety, a healthy economy, ecosystem vitality, and opportunities for enriching experiences – without compromising the needs of future generations. This definition is further carried into the Sustainability Outlook, which is a tool or method for tracking local, regional and state actions and investments to assist in guiding investment and policy changes.

Challenges to sustainability facing California

Update 2018 documents the critical challenges that significantly affect California’s ability to manage water resources for sustainability. These include challenges from flood, access to safe clean water and sanitation, declining ecosystems, groundwater overdraft, forest health and wildfires, and the additional strain on all these challenges due to climate change.

Many of these critical challenges have been known for some time. It is more the systemic and institutional challenges that hamper the ability to address these critical challenges. Early investment in resolving the systemic and institutional challenges will pay the largest dividend for California. These systemic challenges fall into several categories:

fragmented and non-coordinated initiatives and governance

inconsistent and confliction regulations

insufficient capacity for data-driven decision making

insufficient and unstable funding

inadequate performance tracking of state and local investment.

Recommended actions

This plan recommends significant additional investment in infrastructure and ecosystem improvements to overcome challenges to sustainability. It also recommends actions to resolve systemic and institutional issues that contribute to many of California’s water challenges and the ability to resolve them. These actions are organised around the following six goals:

1. improve integrated river basin management

2. strengthen resiliency and operational flexibility of existing and future infrastructure

3. restore critical ecosystem functions

4. empower California’s under-represented or vulnerable communities

5. improve inter-agency alignment and address persistent regulatory challenges

6. support real-time decision making, adaptive management and long-term planning.

These actions will require a USD 90.2 billion investment over 50 years. Of this, USD 77.8 billion is for financial and technical assistance to regional and local entities, USD 9.7 billion for state-managed water infrastructure, and USD 2.7 billion (less than 3%) to resolve systemic and institutional challenges.

Sustainable water management requires alignment and integration among water sectors

The Sustainability Outlook was developed as part of Update 2018 to provide a well‑organised and consistent approach for tracking local, regional, and state actions and investments. It is an evolving method of informing the strategic planning and prioritisation of water management actions. This method, or tool, involves evaluating status and trends of conditions within a river basin or region, setting intended outcomes consistent with societal values, and determining whether actual outcomes are consistent with intended outcomes. Through progressive application of the Sustainability Outlook, decision makers should be able to identify needed analytical tools and data gaps, build capacity to take decisions and set priorities, and describe how individual and collective actions have affected the management of water resources for sustainability. The Sustainability Outlook was informed by stakeholder input and initial pilot projects, as described in The Sustainability Outlook: A Summary.