This chapter examines the possible intergenerational transmission of educational disadvantage imposed by immigrant parents having fewer years of schooling than native-born parents. The first section compares the educational attainment of three groups of native-born students: those with at least one native-born parent; those with two parents born inside the European Economic Area (EEA); and those with two parents born outside the EEA. The second section focuses on the students’ performance at school. It aims at assessing the extent to which parental background characteristics influence skill scores across the different groups of students. This section also investigates the likelihood of students “succeeding against the odds” and other factors influencing school performance, such as language proficiency and the concentration of disadvantaged students at school. Lastly, the third section compares adult skills in numeracy, reading and problem solving between natives whose parents are also native and natives whose parents are foreign-born.

Catching Up? Intergenerational Mobility and Children of Immigrants

Chapter 3. The intergenerational educational mobility of natives with immigrant parents

Abstract

The statistical data for Israel are supplied by and under the responsibility of the relevant Israeli authorities. The use of such data by the OECD is without prejudice to the status of the Golan Heights, East Jerusalem and Israeli settlements in the West Bank under the terms of international law.

Main Findings

The results of this chapter indicate a persisting albeit narrowing gap in educational attainment between immigrants and their offspring and natives and their offspring. However, much of that gap can be explained by the socio-economic background of immigrants’ children, which tends to be lower than that of natives’ children. The extent to which parental characteristics impact their children’s ultimate educational attainment differs greatly between countries.

Natives with immigrant parents are more likely than natives with native parents to attain only a lower secondary education. The gap is largest in Belgium and Austria, where around 10% of natives’ children cease education at a lower level, compared with almost 30% of natives with immigrant parents.

Natives with immigrant parents are less likely than children with native parents to attain any level of tertiary education. On average, the share of those who reach higher educational attainment is 21% for natives with immigrant parents versus 29% for natives with native parents. In Austria, Belgium and Switzerland, natives’ children are two times as likely to enter tertiary education compared to immigrants’ children (around 30% and below 15%, respectively). In the United Kingdom on the other hand, the proportion of university-educated natives with immigrant parents (35%) exceeds the average for natives with native parents (28%).

Controlling for parental education reduces the observed educational attainment gap. The overrepresentation of natives with immigrant parents among the less educated is reduced in all countries, and the under-representation of natives with immigrant parents among the more highly educated is correspondingly reduced as well.

Yet even after controlling for their parents’ education, analysis of the chosen higher education stream (vocational vs. general) shows that natives with parents born outside the EU are 4 percentage points less likely to choose an academic higher education stream.

In most countries, intergenerational educational progress is much faster for natives with immigrant parents than for natives with native parents. In fact, the educational attainments of the two groups converge over time. Natives with immigrant parents generally reach much higher educational levels than their parents. While natives with native parents also reach higher educational levels than their parents, the difference is less pronounced than for natives with immigrant parents. That is partially because native parents already tend to have higher levels of education than immigrant parents.

The link between achieving higher PISA (Programme for International Student Assessment) maths test scores and the parents’ greater educational attainment is much more pronounced for the children of natives than it is for the children of migrants. Parental education thus has less of an effect on children’s test scores when their parents are foreign-born. This result is also found for test scores in reading and science.

Schooling systems that produce more resilient students among the children of natives (defined as children who perform well in school despite their disadvantaged background, also described as children who are “succeeding against the odds”) also increase the likelihood that the children of immigrants will become more resilient. Resilience among the children of immigrants seems to be higher in countries where it is also high for the children of natives.

It is generally difficult to disentangle socio-economic background from immigrant-specific effects in analysing school performance. Factors such as school quality and neighbourhood effects often concern children with a low socio-economic background and children with immigrant parents simultaneously. However, language proficiency seems to be extremely important for children’s success in school, especially for those 41% of children with immigrant parents that speak a language at home that is different from the language in which the PISA test was conducted. OECD analysis shows that the earlier host-country language skills are acquired, the higher the PISA test scores will tend to be.

On the school level, the analysis of PISA scores suggests that socio-economic disadvantage has a much stronger impact on the educational performance of students than the concentration of students with immigrant parents. For example, in Germany, Italy, Slovenia and the Netherlands, students in schools with a high concentration of immigrants perform around 50 points lower than the average. However, this gap disappears when the socio-economic background of parents is taken into consideration. In Denmark, students even perform better in schools with high shares of students with a migration background once socio-economic status is accounted for. On the average in OECD countries, score are reduced from 18 to 5 points.

Introduction

In most European countries, children with immigrant parents tend to have weaker educational outcomes than children with native-born parents. This is partly because the parental generation with a migrant background has on average fewer years of schooling than the native-born parents (OECD/EU, 2015). The objective of this chapter is to study the intergenerational transmission of this disadvantage, and to understand whether lower parental education is more likely to be transmitted among natives with immigrant parents than among natives with native-born parents. It also looks at whether and why there are differences across countries. The chapter is organised around three sections that measure different dimensions of education. The first section analyses educational attainment. The second focuses on the skills acquired in school, using test scores from the OECD Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA). Finally, the third uses data from the OECD Programme for the International Assessment of Adult Competencies (PIAAC) to assess measures of cognitive skills in the adult population.

This chapter’s first section compares educational attainment levels across migration backgrounds, and studies whether the educational gap, with respect to the parental generation, is closing between natives with and without a migration background. This is done by assessing whether students have on average more years of schooling than their parents, and compares that evolution for natives with and without immigrant parents. To capture potential differences in the intergenerational transmission by parental educational level, the section then analyses the association between parental education and the educational attainment of the adult child. The results indicate that children of immigrants attain a higher educational level than the one predicted by their parent’s background, compared to natives. Results overall reveal a narrowing of the educational gap between immigrants’ and natives’ children.

The second section of the chapter focuses on student performance at school. Relying on data from PISA – a standardised test for the reading, mathematics and science abilities of 15-year-old students – the section analyses cognitive skills by parental origin and, in a second step, the intergenerational transmission of education. To help understand differences by parental origin, there is an assessment of how much of the test score differences can be attributed to parental socio-economic background. The results suggest that to a large extent – about 37% – performance gaps are indeed explained by a child’s socio-economic background. However, the extent to which parental characteristics impact their children’s ultimate educational attainment differs greatly between countries.

Finally, the remainder of the chapter compares adults’ cognitive skills by migration background, relying on PIAAC data. In the European Union, natives with a migration background consistently score slightly lower on different measures of skills at each educational level tested, even after taking into account parental educational background. In recipient countries such as Canada and Australia, there are no differences in adults’ cognitive skills by migration background, which likely reflects the selective immigration policy in those countries.

The results from this chapter indicate that a large part of disadvantage is explained by lower socio-economic background, measured by the parental education level. Compared to their peers of native origin, children with immigrant parents complete fewer years of schooling and perform worse in cognitive tests, both in and after school. However, by many measures this gap is narrowing. In fact when taking into account parental education level this gap is greatly diminished and in some countries it disappears altogether. The transmission of any disadvantage is stronger among natives with immigrant parents: having low-educated parents has a stronger negative effect on the education level of natives with immigrant parents than it has on natives with low-educated native-born parents. That signals an “ethnic penalty”, (Heath, 2006) a disadvantage that goes beyond socio-economic status, albeit one much less common among younger cohorts. Overall, these findings are encouraging: the educational outcomes of natives with a migration background are converging towards those of their peers.

Educational attainment

This section compares the educational attainment of natives with a migration background to those without that background. It describes the distribution of attainment for three groups of native-born students: those with at least one native-born parent; those with two parents born in the European Economic Area (EEA), and those with two parents born outside the EEA (thus, natives with immigrant parents). The first sub-section documents a large gap in educational attainment: on average, those with native- or EEA-born parents obtain higher degrees than natives with immigrant parents. The second sub-section analyses the evolution of this educational gap, with respect to both the parent generation and for different cohorts over time. The findings show that natives with immigrant parents are closing the educational attainment gap, which becomes smaller with each new cohort in age of entering the labour market. Compared to their parents, all new cohorts of natives have on average more years of schooling, but this difference is even larger for natives with immigrant parents. Finally, when taking into account their parental background, natives with immigrant parents are no longer at a disadvantage in terms of schooling attainment. All the results point towards a convergence: natives with immigrant parents have on average fewer years of schooling, but are catching up with the natives with native parents.

The distribution of educational attainment

Low educational attainment

Natives with parents born in countries outside the EEA are overrepresented at the bottom end of the educational distribution. Figure 3.1 presents distribution by migration category and country using 2014 European Union Labour Force Survey (EU-LFS) data. The figure focuses on those aged 20 to 39 and shows that the proportion of those with lower education levels is higher among native children with immigrant parents than among natives without migration background, or among the natives with EEA-born parents. In 15 of the 21 countries for which comparable data are available, natives with immigrant parents are more likely than natives’ children to complete lower secondary education as their highest educational attainment. The gap in lower attainment rates between natives with immigrant parents and natives’ children is largest in Belgium and Austria, where around 10% of natives’ children cease education at a lower level while almost 30% of natives with immigrant parents do. The population-weighted average across the EEA countries analysed shows that 17% of natives’ children cease their education at a lower level, while almost 30% of the natives with immigrant parents do. The only exceptions are the three Baltic countries, Portugal and the United Kingdom. Independently of migration background, in Portugal the percentage of those low educated is high compared to other countries, whereas in the United Kingdom it is low.

This overrepresentation of natives with immigrant parents at the bottom of the educational spectrum is partly explained by parental background. Immigrant parents from non/EU-EFTA countries have on average fewer years of schooling than native parents (OECD/EU, 2015). Given the degree of intergenerational transmission of education, it is expected that natives with immigrant parents also have lower years of schooling than their peers with native parents. However, countries differ greatly in the extent to which natives with immigrant parents are overrepresented at the bottom end of the educational spectrum. This is mostly because countries differ in their migration history, and thus in their shares of low-educated immigrants from non-EU countries in the population.

High and medium educational attainment

In most EU countries, natives with immigrant parents are under-represented in higher education, mirroring the overrepresentation in lower education. As shown in Figure 3.1, obtaining a higher education degree is more common for natives with native-born parents than for natives with immigrant parents. The exceptions are the United Kingdom and the Baltic countries, where, compared to natives’ children, natives with immigrant parents are either slightly overrepresented (in the United Kingdom) or equally represented (in Baltic countries) among the tertiary-educated.

Figure 3.1. Distribution of educational attainment of natives by migration background, 20-39 year-olds, percentages

Note: Lower education corresponds to ISCED 0-2, medium educated to ISCED 3-4, and highly educated to ISCED 5-6.

Source: EU-LFS, 2014; CPS data for the United States.

In 16 of the 21 countries, natives with immigrant parents are less likely than natives’ children to be tertiary-educated. Within these 16 countries, outcomes differ considerably. The largest gaps are found in Austria, Belgium and Switzerland. In those countries, around 30% of natives with native-born parents have attained a higher education degree. This proportion drops to less than 15% for the natives with immigrant parents. In other western European countries, the gap is somewhat smaller. For example, in France, the Netherlands and Sweden, around 35% of those with native parents have attained a tertiary degree compared to 25% of the natives with immigrant parents. In the 21 countries analysed, the population-weighted average of those who reach a higher educational attainment is 21% for the natives with immigrant parents and 29% for natives with native parents. In the United Kingdom, the proportion of university-educated natives with immigrant parents (35%) exceeds the average for natives with native parents (28%). In Baltic countries, natives with immigrant parents are proportionally represented in among the highly educated.

The attainment of medium-level degrees (such as completing secondary school and having a short tertiary degree) also differs by country and migration background. In Austria, Ireland and the United Kingdom, natives’ children are around 10 percentage points more likely to have medium-level educational attainment than natives with immigrant parents. However, this is not the case in the Netherlands, Belgium, France, Sweden or Switzerland, where natives with immigrant parents and natives’ children are roughly equally represented among the medium-educated.

Analysing highest educational attainment: Who drops out and who reaches university?

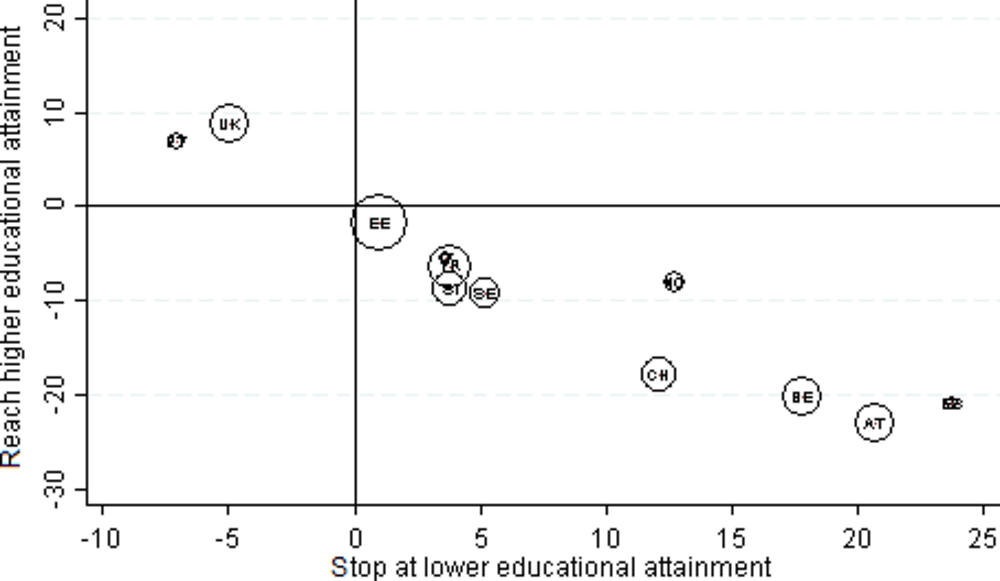

Figure 3.2 documents the difference between natives with immigrant parents and the children of natives, in the percentage of the population that a) stops at a lower level of educational attainment, and b) reaches a university degree. These differences are measured using an econometric model that takes into account gender and age. Children with parents born in the EEA are found to have educational attainment almost identical to those with native parents – hence the results for them are not shown. Two main facts emerge from the results presented in Figure 3.2. The first is that natives with immigrant parents are on average more likely to stop at a lower educational level and consequently also less likely to obtain a university degree. The second fact is that countries differ greatly with regard to both low and higher attainment rates.

In Austria, natives with immigrant parents are 20 percentage points more likely than natives to cease their education at a lower educational level (as shown on the horizontal axis), and 22 percentage points less likely to have a tertiary degree (as shown on the vertical axis). In the United Kingdom, natives with immigrant parents are slightly less likely than those with native parents to stop at a lower educational level (-5%), and are around 8% more likely to obtain a tertiary degree. A good illustration of the differences among countries shown in Figure 3.2 is the comparison between Norway and Switzerland. In both countries, the percentage of natives with immigrant parents that stops at lower educational attainment is around 12 points higher than for the natives’ children. However, these two countries differ when it comes to higher education. In Norway, natives’ children are 10 percentage points more likely than natives with immigrant parents to reach a university degree, while in Switzerland this difference is 22 percentage points.

Figure 3.2. Likely comparative educational attainment of immigrants’ children, ages 20-35, without controls for parental education

Notes: Two steps – first, probability of educational outcome, given migration category, age and gender. No controls for parental education. Second, marginal likelihood of being in either higher or lower education for the children of immigrants compared to natives’ children.

Taking Austria (AT) as an example, natives with immigrant parents are 22 percentage points less likely to attain a higher education than natives with no migration background, and around 20 percentage points more likely to stop their schooling at the lowest of three educational steps.

Source: EU-LFS, 2014.

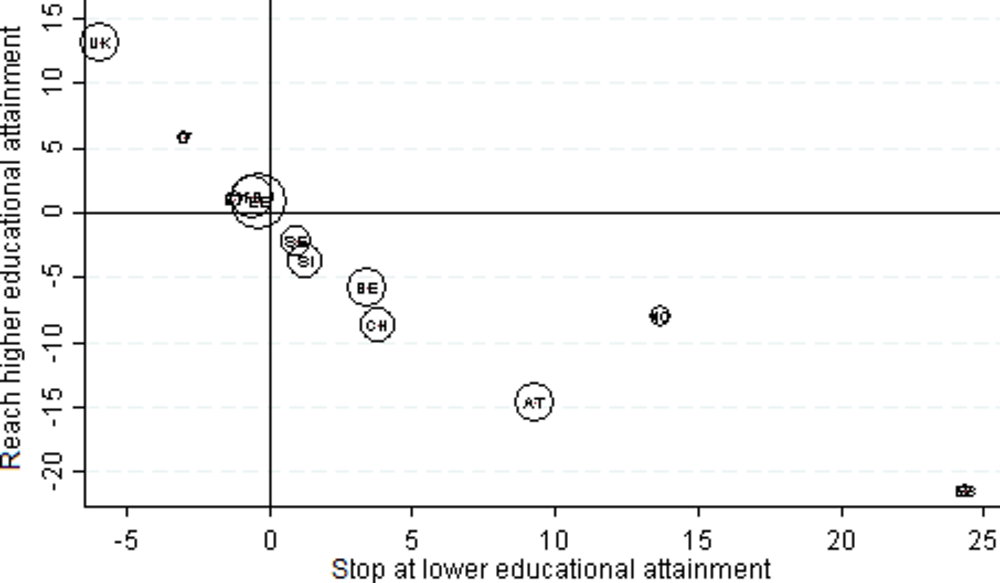

The results presented in Figure 3.2 do not, however, take into account parental educational background. If most of the achievement gap is due to socio-economic background, then one would expect that taking into account the parents’ highest educational attainment would reduce differences in attainment. Figure 3.3 reports the results from the same model, and adds parental background to the estimation.

Accounting for the education of the parents, the first and salient observation is that countries move to the upper left quadrant in Figure 3.3 as compared to Figure 3.2. Thus, controlling for parental education reduces the observed educational attainment gap. The overrepresentation of natives with immigrant parents among the low-educated is reduced in all countries, and the under-representation of natives with immigrant parents among the more highly educated is correspondingly reduced as well. Moreover, educational outcomes of natives with immigrant parents are no longer significantly smaller in six of the previous ten countries for which they were smaller.

Controlling for parental educational background reduces the attainment gap by a very large amount. In France and Sweden, the children of immigrants are no longer significantly different from natives’ children in their educational attainment. In Switzerland the difference in the share of the cohort that stops at a lower educational level is reduced from 13 percentage points to less than 3 percentage points. This reduction is even larger in the case of Belgium (17 percentage points to 4 percentage points).

Figure 3.3. Likely comparative educational attainment of immigrants’ children, ages 20-35, controlling for parental education

Notes: The figure accounts for the highest parental educational attainment.

Two steps – first, probability of educational outcome, given migration category, age, gender and parental education. Second, marginal likelihood of being in either higher or lower education for the children of immigrants compared to natives’ children.

The percentage point differences in Austria for instance decrease from 22 to 15 percentage points for the children of immigrants, and from 20 to 8 percentage points for natives’ children.

Source: EU-LFS, 2014.

The intergenerational transmission of education: Is the educational gap closing?

This section looks at the intergenerational transmission of education, and analyses whether the educational gap has narrowed in recent years. Measuring this evolution does however pose a few methodological challenges. The age of leaving education may be different for each successive cohort. Given the general rise in educational attainment, the parents of each new cohort should have higher educational attainment than the previous cohort’s parents. Although this is the case for native parents, it is not always the case for immigrant parents, because for instance countries of origin change over time. This complicates the comparison between two different cohorts of natives with immigrant parents, which in turn renders assessment of the evolution compared to that for natives with native-born parents more difficult. (Three different methodologies to evaluate the evolution of the educational gap and the intergenerational transmission of education are presented in Annex 3.A.)

Evolution of the gap in educational attainment between parents and offspring

The educational attainment gap between parents and adult child is measured with respect to respondents’ own parents, allowing a direct link. As explained in the methodological box in Annex 3.A, each person interviewed in the EU-LFS is asked about the highest level of education attained by both parents. The evolution from one generation to the next is measured as the respondent’s education minus the higher of the two parents’ educational attainment. Education is measured using the 3-point ISCED scale for respondents and parents. This evolution is measured independently for each migration category, using the 20-35 age group taken from the 2014 EU-LFS.

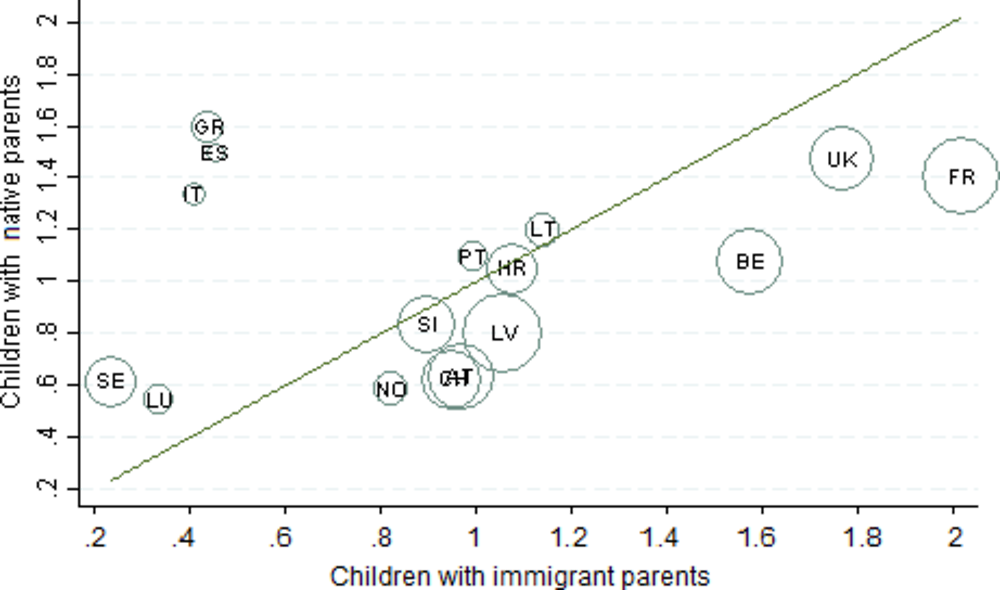

Figure 3.4. Evolution of educational attainment as compared to that of parents

Notes: The size of circles represents the share of the children of immigrants in the population of the country.

In Belgium for example, among those aged 20-35, natives with immigrant parents have 1.6 years of schooling more than their parents had, while those with native parents have 1.1 points more than their parents had. Countries under the green line indicate that compared to their parents, natives with immigrant parents progress faster than their native peers.

Source: EU-LFS, 2014.

The first and salient fact that emerges from Figure 3.4 is that in most countries, progress with respect to parental education is much faster for natives with immigrant parents than for natives with native parents. The figure shows the educational attainment of the two groups converge, especially in countries with large shares of natives with immigrant parents in their population. Natives with immigrant parents reach much higher educational levels than their parents and while this is also the case for natives, the difference with respect to their parents is less pronounced. This is partially because native parents already have on average high education levels, but it nonetheless shows a reduction of the gap between one generation and the next.

In France for example, natives with immigrant parents have around two more years of schooling than their parents had. Natives with native parents have 1.4 additional years of schooling with respect to their parents. Hence, taking into account that immigrant parents have fewer years of schooling, their offspring are converging in their educational attainment with the level of the natives with native parents.

Considering the 18 countries analysed in Figure 3.4, the population-weighted average indicates that natives with immigrant parents have on average 1.3 years of schooling more than their parents, while those with native parents have 0.7 years of schooling more than their parents. Among parents, the difference in educational attainment between natives and immigrants is roughly 1.24 years of schooling, while among natives with immigrant parents this difference is roughly 0.68 years of schooling. It emerges from this picture that the educational gap within the offspring cohort is smaller than the one observed among their parents. That gap has almost halved within one generation. Summing up, there is an unequivocal convergence in the educational attainment between natives with immigrant parents and those with native parents. Progress in the number of years of schooling with respect to parents is faster for natives with immigrant parents than for other natives.

Are natives with immigrant parents at a disadvantage?

This sub-section analyses whether natives with immigrant parents are at a disadvantage in terms of educational attainment after accounting for parental education, and whether intergenerational transmission of education differs between them and peers of native origin. Table 3.1 presents the results from a regression analysis with educational attainment as the main outcome of interest.1 The first column of the table presents the most basic model, in which educational attainment is explained by migration category, controlling for individual-level characteristics. The results indicate that compared to their peers with native parents, natives with immigrant parents have on average a half-year’s less schooling.

The second column presents a model in which the highest educational attainment of parents is taken into consideration. This reduces the initial educational gap from 0.54 to 0.17 years of schooling. Two-thirds of the educational attainment difference between natives with immigrant parents and those with native parents disappears when taking into account the fact that natives with immigrant parents have on average parents with fewer years of schooling. Column 2 also provides a measure of the intergenerational transmission of education. It shows that the correlation between parental and children’s education is 0.25. This intergenerational transmission of education means that for every extra year of schooling of the parent, a child has on average 0.25 years of schooling more. In other words, a parent with a university degree (compared to one with a high school diploma) has a child with an average of 1 year of schooling more than the child of a parent with a high school diploma.

Table 3.1. Comparative educational attainment of the children of immigrants, three models

Years of schooling; reference group = natives with native-born parents

|

Basic |

Parental education |

Interaction term |

|

|---|---|---|---|

|

Natives with parents born outside the EU |

-0.543*** |

-0.174*** |

0.98*** |

|

Natives with EU-born parents |

-0.0464 |

0.0337 |

0.361 |

|

Correlation with parental highest educational attainment |

0.254*** |

-0.266*** |

|

|

Interaction term |

-0.12*** |

||

|

Other controls |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Notes: The countries included in this regression are Austria, Belgium, Switzerland, France, Sweden, Norway, the United Kingdom, Spain and Italy. Basic = educational attainment explained by migration category, controlling for individual-level characteristics. Interaction = Parents’ highest educational attainment is coded on a three-point scale, with 1 being low, 2 medium and 3 high. Other controls include age, the square of age, gender, and country fixed effects. *** p<0.01, ** p<0.05, * p<0.1

Source: EU-LFS, 2014.

The model presented in column 2 assumes however that the strength of intergenerational transmission of education is the same for natives and immigrants. The next model presented, in column 3, relaxes this assumption. It allows for this coefficient to be different across migration categories, which proves highly important for assessing intergenerational mobility. When taking into consideration that parental education may have different effects for natives and immigrants, natives with immigrant parents are no longer at a disadvantage with respect to their native peers. In fact, natives with immigrant parents outperform their peers when the intergenerational transmission of education is allowed to differ by migration category. The 0.25 correlation between the parent’s and child’s education for natives is much lower for the immigrants’ children: as shown in the interaction, 0.12 points lower. The educational attainment of immigrants is thus less correlated with their children’s than is the case for natives. To analyse whether the results are driven by the United Kingdom, a separate analysis was performed excluding that country from the sample. The regression yields similar results.

Results from the regressions presented in Table 3.1 thus clearly show that natives with immigrant parents are less at a disadvantage in terms of schooling if their parental background is accounted for. The intergenerational transmission of education is stronger for those of native origin, which gives natives with immigrant parents an advantage. Immigrants’ children have a level of education converging towards that of their native-origin peers.

Intergenerational transmission of education may not be the same across all parental education levels. Table 3.1 shows average results across all three levels of parental education (high, medium and low), and does not allow for analysis of mobility patterns by parental education level. Given the overrepresentation of immigrant parents at the bottom spectrum of the educational distribution, however, it is important to analyse educational mobility for this group in particular, and compare it to mobility patterns of native-born parents that are equally low educated. In other words, the key question in this section is whether educational opportunities differ by parental migration background, considering that the parental education level is low across all groups. What is the probability for completing medium and/or high education for someone who has low-educated parents born outside the EU as opposed to someone whose parents are native-born and equally low educated? And second, controlling for parental educational background, do individuals choose different educational paths, i.e. academic vs. vocational/technical streams?

Results in the table show that natives with low-educated parents born outside the EU have a 5 percentage point lower probability of completing medium or higher education, compared to natives with equally low-educated native-born parents. Interestingly, when looking at the younger cohort (under 40 years of age), there is still an “ethnic penalty” (Heath, 2006) but it is much weaker, suggesting that the gap is narrowing over time.

An analysis of the chosen higher education stream (vocational vs. general) shows that natives with parents born outside the EU have a 4 percentage point lower probability of choosing an academic higher education track, even after controlling for their parental education (Table 3.2, column 3). Results for natives with parents born in the EU show no significant effects.

Table 3.2. Educational opportunities and the intergenerational transmission of disadvantage

Reference group: Natives with native-born low-educated parents (for columns 1 and 2)

|

|

Medium/higher education |

Medium/higher education Age<40 |

Academic higher education stream |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Natives with parents born outside the EU |

-0.046** |

-0.0174** |

-0.049* |

|

Natives with EU-born parents |

0.0198 |

0.0040 |

0.0353 |

|

Other controls |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Notes: Countries included in this regression are Austria, Belgium, Switzerland, France, Sweden, Norway, the United Kingdom, Spain and Italy. Sample includes only those individuals with low-educated parents. Controls include age, the square of age, gender and country fixed effects. The third column includes parental education as a control. Only those who are not in education and training anymore are kept in the analysis. *** p<0.01, ** p<0.05, * p<0.1.

Source: EU-LFS, 2014.

PISA scores by migration background

The previous section has shown that natives with immigrant parents attain on average lower educational levels than natives, although this disadvantage is greatly reduced after controlling for parental background. This section focuses on performance in school using PISA scores as the main measure. (Annex 3.B summarises the literature on how well PISA scores predict later achievement of students who are natives with immigrant parents.) The main objective of the section is to understand whether the PISA test scores of a given group of natives are more or less affected by their parental educational attainment. In other words, it analyses the influence of parental educational level on the PISA test scores for different groups of natives.

Figure 3.5 shows PISA test scores in mathematics by parental origin. In almost all countries the scores of natives with immigrant parents are worse than those of other natives with native parents. It can be seen that the performance of students with a migration background differs widely across countries.

Figure 3.5. PISA 2015 mathematics test scores by migration background

Source: OECD (2015), “PISA: Programme for International Student Assessment”, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/data-00365-en.

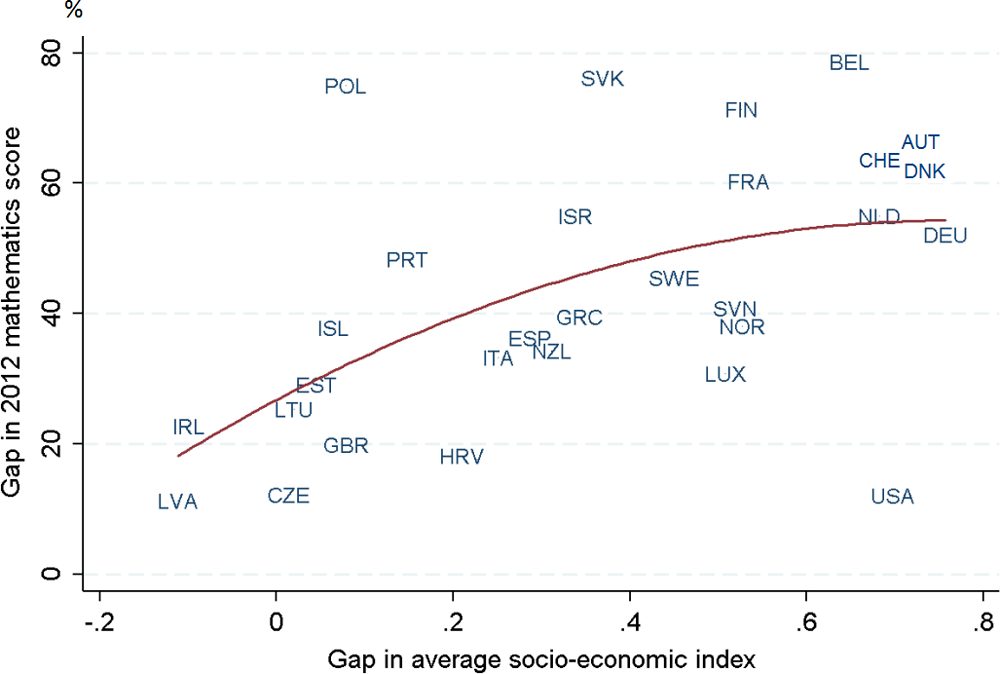

Figure 3.6. Gaps in PISA scores and in average socio-economic background

Source: OECD (2015), “PISA: Programme for International Student Assessment”, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/data-00365-en.

Figure 3.6 plots the average gap in socio-economic background between natives and migrants, and shows its relationship to the performance gap in mathematics and other test scores. As noted in OECD (2015), “Around 25% of the variation in test scores across countries is explained by differences in mother’s attainment level [between migrants and natives]”. The results show that the gap in PISA scores is higher in countries where the socio-economic gap is larger between natives and migrants. The larger gap in tests scores observed in Western European countries with large populations of natives with immigrant parents, such as Belgium, Germany and France, is partly explained by the large gap in socio-economic background in those countries.

How strongly is high parental education related to PISA performance?

Children’s test scores rise with the level of schooling of their parents. Given that immigrants have on average less schooling than natives, at least part of the test score gap between their children is attributed to the differences in parental education. However, countries differ in the extent to which educated parents are able to transmit this advantage to their children. In some countries, test scores are less determined by parental background. This sub-section studies the extent to which parental education is transmitted to children’s test scores, and the differences among countries and migration backgrounds.

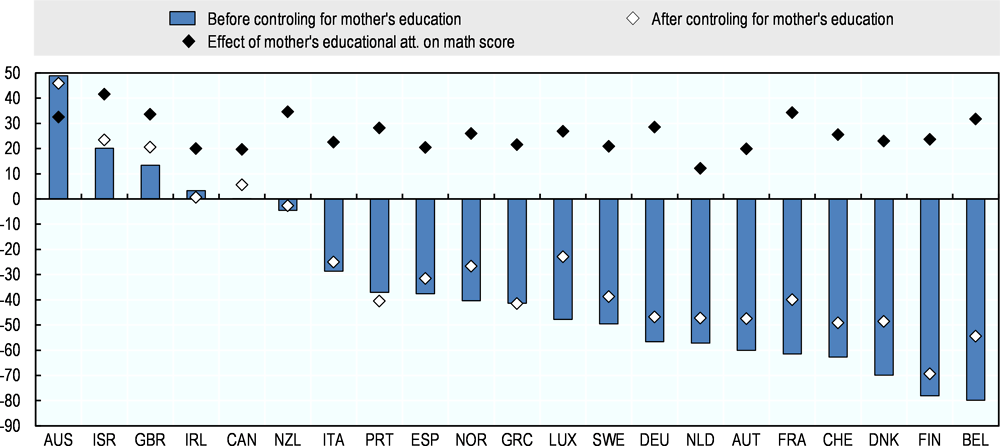

To better illustrate the link between parental education and children’s test scores, Figure 3.7 shows the gap in mathematics scores between natives with native parents and those with immigrant parents, before and after accounting for mothers’ education level. On average, the initial gap of 47 points is reduced to 30 points when taking into account the educational achievement of the mother and the broader socio-economic background of children’s families. This measure of socio-economic background is calculated by PISA and includes parental education, but also parental occupation, whether or not there are books at home, and other measures. Large disparities among countries can be observed in the extent to which the socio-economic background of the parents translates into higher test scores for children. In Sweden, the effect of the mother’s education on students’ test scores is around 20 points, whereas this increases to almost 35 in France. In the Netherlands, the child of a university-educated mother is on average only 12 points ahead in mathematics compared to a child whose mother has a high school diploma. This gap is much higher in other countries: it stands above 30 points in Belgium, France and the United Kingdom.

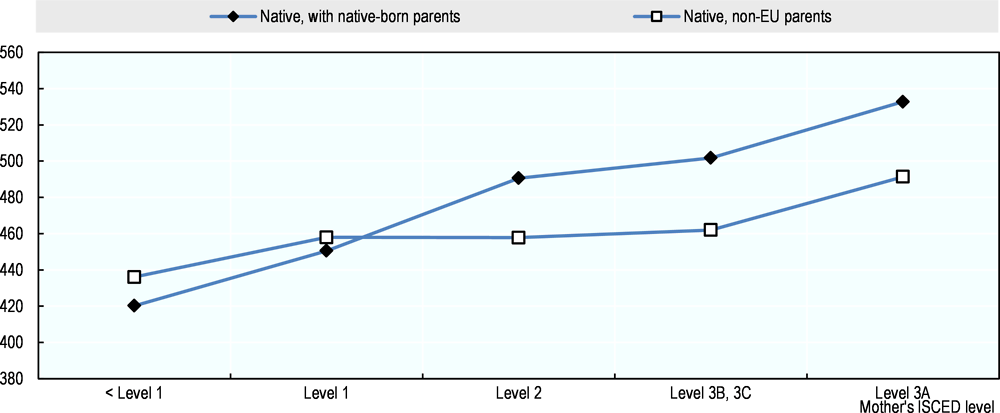

However, the relationship between mothers’ education and test scores differs for natives with and without a migration background. The relationship between the mother’s highest educational attainment and her children’s test scores is further analysed by migration background in Figure 3.8. Analysing EEA countries, this figure plots the average test scores by mother’s educational attainment, for children of different migration backgrounds. The main result that emerges from this analysis is that the relationship between test scores and mother’s educational achievement is much steeper for natives with native-born parents as compared to natives with parents born outside the EU. The test scores of the natives with immigrant parents increase less with their mother’s educational achievement than for any other migration category. This result is very similar to the one found in Bratsberg (2011), where the link between test scores and the parental educational attainment is much more pronounced for the children of natives than it is for the children of migrants.

Figure 3.7. PISA score gaps between students with immigrant parents and students with native parents, before and after accounting for the mother's education

Source: OECD (2015), “PISA: Programme for International Student Assessment”, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/data-00365-en.

This intergenerational transmission of education is further analysed using an econometric modelling of test scores (Table 3.3) using students’ test scores in 28 EEA countries. Test scores are initially regressed on migration categories and individual characteristics. The results from Table 3.3 indicate that the lower educational attainment of the migrant mother explains almost a third of the difference in test scores between natives’ and migrants’ children (column 2).

Figure 3.8. PISA 2015 mathematics scores by parental origin and mother's educational level in EU/EEA countries

Source: OECD (2015), “PISA: Programme for International Student Assessment”,

Table 3.3. Association between parental educational level and origin and child's math score

Reference group: Natives with two native-born parents

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Native with 1 foreign-born parent |

-7.675*** |

-7.746*** |

-7.769*** |

-8.578*** |

-7.984*** |

|

|

Native with 2 foreign-born parents |

-47.48*** |

-35.51*** |

-15.53*** |

-26.88*** |

-26.11*** |

|

|

Mother's educational attainment |

28.21*** |

28.74*** |

|

|||

|

Interaction Mother education*native with migration background |

|

|

-6.973*** |

|

|

|

|

Index of socio-economic background |

|

|

|

39.02*** |

33.37*** |

|

|

|

|

|

||||

|

Females |

-11.14*** |

-11.16*** |

-11.18*** |

-10.62*** |

-14.63*** |

|

|

School characteristics |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Log class size |

|

|

|

|

69.02*** |

|

|

Average level of mother's education at school |

|

|

|

|

31.5*** |

|

|

Percentage of children with migration background |

|

|

|

|

-43.51*** |

|

|

Observations |

202 707 |

192 440 |

192 440 |

201 459 |

126 629 |

|

|

R-squared |

0.073 |

0.147 |

0.147 |

0.215 |

0.259 |

|

Notes: *** p<0.01, ** p<0.05, * p<0.1. OLS regression output table. Controlling for gender, age, socio-economic index, mother's education, log class size, school-level controls (column 5 only). With country FE.

Source: OECD (2015), “PISA: Programme for International Student Assessment”, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/data-00365-en.

The first column of Table 3.3 compares the test scores of children with native-born parents to children with one and with two foreign-born parents. Natives with immigrant parents score on average 47 points fewer than natives with native or EU parents. Columns 2 and 4 add the mother’s highest educational attainment and an index of socio-economic background. After controlling for parental background, the gap observed for natives with immigrant parents is reduced from the initial 47 points to around 36 points. Higher parental education is found to have a positive effect on test scores, independently of the specification chosen. The implicit assumption in columns 2 and 4, however, is that the effect of parents’ education is the same for native and migrant parents.

Column 3 relaxes this assumption and tests whether the intergenerational transmission of education differs by migration background, by introducing an interaction term between the migration background and mother’s education. The performance gap between natives with immigrant parents and natives’ children is thus further reduced to only 16 points. The interaction is negative and significant, suggesting that parental education has less of an effect on children’s test scores when their parents are foreign-born. This result is also found for test scores in reading and science.

Resilient children

Children who perform well in school despite their disadvantaged background are often referred to as being “resilient” – they have succeeded against the odds. This sub-section compares the likelihood of being a resilient child across migration backgrounds and countries. Children are categorised as resilient when their test scores are in the country’s top 25%, while coming from a household in the bottom 25% of the country’s socio-economic index. This index captures parental education, income, and other household characteristics.

Resilience rates differ greatly by country and by migration background. Overcoming the lower socio-economic background of their parents is around twice less likely for native children with parents born outside the EEA, compared to native children. On average, in the EEA countries analysed, a child from a household in their country’s bottom quintile of the socio-economic index has a 13% chance of being resilient (OECD, 2015b). The gap in resilience between natives with native parents and natives with parents born outside the EU differs greatly across countries. The average resilience rate, when weighted by population, is 8% for natives with immigrant parents and 14% for those with native or EU parents. In Switzerland, the United Kingdom and Norway, resilience is found among 12% of natives with immigrant parents but more than 20% of those with EU or native parents. At the other end of the spectrum, natives with immigrant parents have very low resilience rates in France, Belgium and Germany (less than 7%), while the resilience of natives’ children is around 12%.

Table 3.4 presents the results from a model that looks at the characteristics that correlate with being resilient. To improve the comparability between children of native parents and children with immigrant parents and avoid reliance on language skills, only the pupils’ mathematics scores are considered. The reference category is natives with native or EU-born parents. Compared to this category, native-born children with immigrant parents are on average 2.6 percentage points less likely to become resilient children, as shown in column 1. This gap in the rate of resilience changes relatively little when teacher and school characteristics are included (columns 2 and 3). Schooling systems that produce more resilient kids for natives also increase the likelihood that the children of immigrants become resilient. In countries where disadvantaged children of natives are more likely to be resilient, children of migrants do better as well. Resilience among the children of migrants seems to be higher in countries where it is also high for the children of natives.

Table 3.4. Likelihood of being resilient

Reference: Native with native or EU parents

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

|

|---|---|---|---|

|

Native with parents born outside the EU |

-0.026*** |

-0.0228** |

-0.0202* |

|

Index of the feeling of belonging at school |

0.00182 |

0.000469 |

|

|

Index of teacher relationship |

0.0155*** |

0.0146*** |

|

|

Index of discipline |

0.0151*** |

0.0162*** |

|

|

Class size (log) |

0.158*** |

||

|

Females |

-0.0409*** |

-0.0508*** |

-0.0612*** |

|

Observations |

1 180 708 |

935 132 |

798 115 |

Notes: *** p<0.01, ** p<0.05, * p<0.1. Controlling for age. With country FE. EU and EFTA countries only.

Source: OECD (2015), “PISA: Programme for International Student Assessment”, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/data-00365-en.

Other factors related to performance in school

The lower performance in test scores for natives with immigrant parents relative to their peers is due to many different factors. Those related to parental socio-economic background have been covered in the previous sub-section. As seen in Table 3.3, the parental educational background explains around a third of the gap between immigrants’ and natives’ children, and it is the most important predictor of a child’s test scores. However, even after accounting for the schooling attainment of parents or for their socio-economic status, there remains a performance gap. It seems that there are other factors explaining that gap between the different groups of natives. This subsection covers the factors that are less related to parents and more to the schooling environment. Two different dimensions are covered: the characteristics of the school (in terms of teachers, rules, independence, parent-school relations, the discipline environment) and those of the student’s peers.

School characteristics

Exposure to a high-quality school or preschool, as compared to children who do not attend preschool, has been shown to improve the outcomes of children with less educated parents. Cunha and Heckman (2010) reviewed the body of evidence from different randomised programmes, such as the Perry Preschool Program in the United States. Their results show that attending preschool significantly improved the children’s outcomes, especially the non-cognitive attributes of disadvantaged children. The characteristics of the schooling system itself – the degree of school autonomy, the quality of teachers, and their readiness to teach to children of immigrants – may be linked to the low performance observed for the children of immigrants.

Peer characteristics and the concentration of disadvantage

The comparatively low performance of students with immigrant parents may also be an outcome of an accumulation of disadvantage that occurs when immigrant families settle in low-income neighbourhoods and send their children to schools where the share of disadvantaged students is high. However, the economic literature on peer effects suggests that socio-economic disadvantage has a much stronger impact on educational performance than the concentration of students with immigrant parents itself. See Annex 3.C for lessons from schools in overcoming children’s disadvantaged backgrounds.

The economic literature studying these peer effects has documented them at two levels: the classroom level, and at the neighbourhood level. At the classroom level, students that have been exposed to domestic violence have been found to significantly affect the test scores of their peers (Carrell, Hoekstra and Kuka, 2016), and also affect other long-run outcomes such as labour earnings years after. Carrell and Hoekstra (2016) also find effects from behavioural problems in school. Black, Devereux and Salvanes (2013) find that boys (but not girls) benefit from being exposed to peers from high-earnings families, by having lower likelihood of dropping out, higher test scores, and higher earnings in adulthood. At the neighbourhood level, low-income families that move to higher-income neighbourhoods also benefit in terms of better test scores, lower likelihood of dropping out of school, and higher earnings later in life (Chetty and Hendren, 2015).

In itself, the clustering of students with immigrant parents in certain schools does not have a negative impact on educational performance. “Educational segregation” is particularly pronounced in Norway, Denmark, Canada, Italy and Greece, where 70% to 80% of all native and foreign-born students with immigrant parents go to schools where at least half of the student body also has a migration background (OECD, 2015b). Negative peer effects are found to come from students with lower educated parents, but not specifically from the children of immigrants.

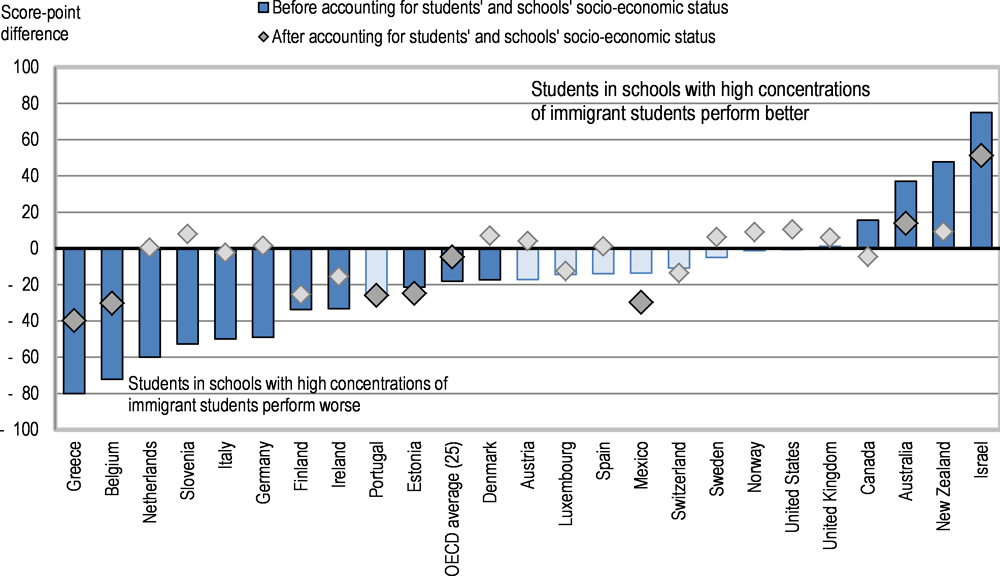

The lower performance of students in schools with a highly diverse population is a product of socio-economic disadvantage rather than of immigrant background, as shown in Figure 3.9. The figure shows that in most countries, students who go to schools with a high share of natives with immigrant parents (here defined as more than 25% of a school’s student population) do worse than students in schools with low shares of natives with immigrant parents. However, these differences shrink considerably when accounting for the socio-economic background of students.

Figure 3.9 suggests that socio-economic disadvantage has a much stronger impact on educational performance than the concentration of students with immigrant parents. For example, in Germany, Italy, Slovenia and the Netherlands, students in schools with a high concentration of immigrants perform around 50 points lower than the average. However, this gap disappears when the socio-economic background of parents is taken into consideration. In Denmark, students even perform better in schools with high shares of students with a migration background once socio-economic status is accounted for. On average, score differences are reduced from 18 to 5 points. Although score differences are approximately halved in Greece and Belgium, they remain large. In Finland, Portugal and Estonia, initial gaps are somewhat smaller, and in fact little affected by socio-economic status.

The finding that a higher concentration of immigrants’ children in schools does not necessarily pose a disadvantage is also supported by country-specific studies. Birkelund and Hermansen (2015) have looked at long-term educational outcomes of students in Norway, using registry data covering more than 750 schools. They found that students in cohorts with more immigrant peers had an even higher likelihood to complete higher secondary education compared to those with less exposure, with the effect higher for the children of immigrants. These peer effects seem to mainly reflect the presence of immigrant classmates from high-achieving origin regions, while the corresponding negative effects of exposure to immigrant classmates from low-achieving origin regions is not found.

Figure 3.9. Concentration of disadvantage and performance in school

Source: OECD (2015), “PISA: Programme for International Student Assessment”, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/data-00365-en.

Language proficiency

Another important predictor of children’s performance at school is their language skills. These skills predict test scores not only for students aged 15 in PISA, but also for children in primary school. Schnepf (2007) looked at how language skills explain the performance gap between natives with immigrant parents and their peers. For the analysis, she used three sources of test scores: PISA, TIMMS and PIRLS, and looked at 10 different OECD countries. Her results show that when controlling for the language spoken at home, part of the gap between natives with immigrant parents and native’s children disappears, even after controlling for the socio-economic and migration background of children. This result is also backed by Levels, Dronkers and Kraaykamp (2008).

Early exposure to the host country language is extremely important for children’s success at school. It predicts surprisingly well the test score of children of immigrants. Children who arrived in their early childhood and who benefited from language exposure early in their life, have higher test scores than those who arrived aged 6-11, who in turn also perform better compared to those who arrived later (OECD, 2015b). Nursery education enrolment, in ages from 0 to 3, is likely to be a factor improving the language skills of the natives with immigrant parents, independently of the language spoken at home.

Many of the students with a migration background mainly speak a different language at home. Within EU-15 countries, around 40% of the natives with immigrant parents speak a foreign language at home, although this percentage varies significantly by country. In the United Kingdom and Ireland, less than 25% of natives with immigrant parents speak a foreign language at home. In France and Germany this proportion increases to around one-third. In Denmark, Sweden, Switzerland and Belgium, around half of natives with immigrant parents speak a foreign language at home. After accounting for the language spoken at home, the test-score gap is further reduced. As seen in Table 3.5, children of immigrants have on average 48 points fewer than children of natives in PISA scores. Controlling for parental background reduces the performance gap by almost one-third, to around 36 points. Controlling for the language spoken at home (column 4) reduces it even further, to make it insignificant.

Table 3.5. Language skills and the test score gap

Dependent variable: Mathematics test scores; Reference: Natives with two native or EU-born parents.

|

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Native with parents born outside the EU |

-47.86*** |

-36.23*** |

-14.45** |

-2.72 |

|

Foreign-born with EU-born parents |

-19.04*** |

-19.66*** |

-19.72*** |

-15.7*** |

|

Foreign-born with parents born outside the EU |

-54.81*** |

-43.81*** |

-43.68*** |

-31.89*** |

|

Mother's highest education level |

|

28.23*** |

28.8*** |

28.49*** |

|

Mother's highest education level * natives with immigrant parents |

|

|

-7.5*** |

-8.813*** |

|

Foreign language at home |

|

|

|

-13.92*** |

|

Observations |

208 953 |

195 918 |

195 918 |

188 240 |

Notes: *** p<0.01, ** p<0.05, * p<0.1.

Source: OECD (2015), “PISA: Programme for International Student Assessment”,http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/data-00365-en.

Adult skills in PIAAC

The skills used in everyday life and at work are an important correlate to labour market inclusion and productivity, and have a direct bearing on people’s lives. Previous research has found that schooling attainment is an imperfect proxy for skills, particularly for immigrants who have obtained their education abroad (OECD, 2016). Hence, when controlling for the educational background of immigrants, one might be overestimating their skills. The implication from this finding is that controlling for parental education overestimates the educational background of natives with immigrant parents. It also implies that observing a lower “return” to parental education might be explained by their parents’ lower skills. It may be the case that immigrant parents are just as able as native parents to transmit human capital.

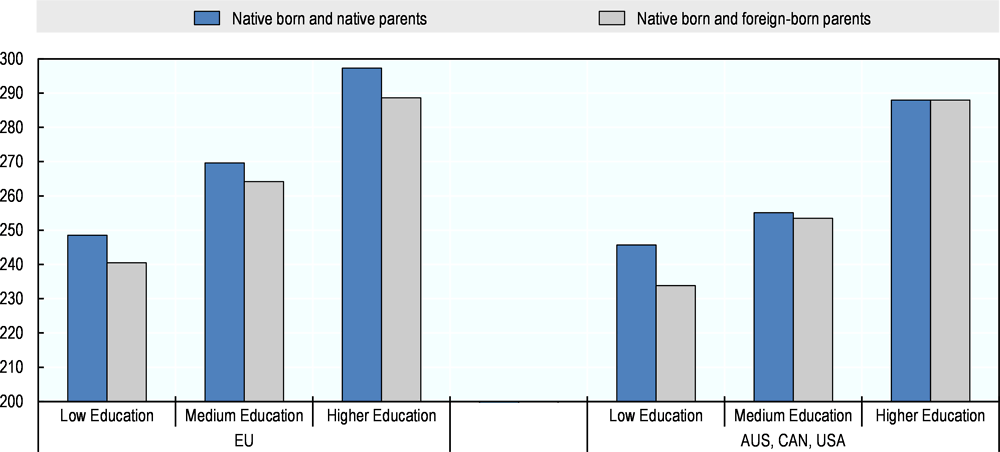

The next paragraphs compare adult skills in numeracy, reading and problem solving of natives whose parents are native and natives whose parents are foreign-born, using PIAAC data. Due to data limitations, no distinction is made between parents from EU and non-EU countries.

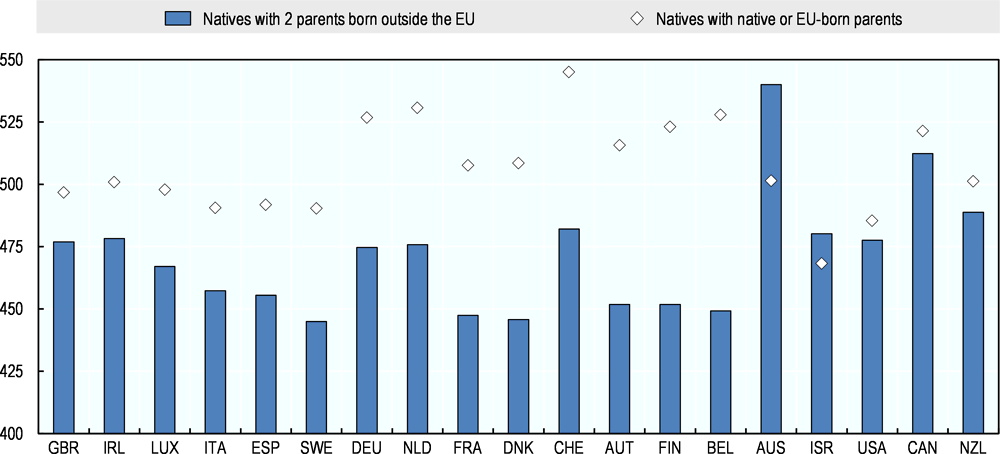

In western European countries, adult skills in numeracy and problem solving are lower for natives with immigrant parents than those with native parents. Figure 3.10 shows that among the low, medium and highly educated, natives with native parents score higher than those with two foreign-born parents. Some of the gap in scores might be explained by certain background characteristics. However, when taking into consideration age, gender, educational attainment, parents’ educational attainment, and country of residence, natives with foreign-born parents still score lower than their peers, as shown in Table 3.6. At the same time, the highly and medium educated adult natives with immigrant parents in the United States, Canada and Australia do not score significantly lower than other natives even after taking into account their educational level and parent’s education, as shown in Figure 3.10.

Figure 3.10. PIAAC numeracy scores by education level

Source: OECD (2015a), Survey of Adult Skills (PIAAC).

Table 3.6. PIAAC score estimations

PIAAC Numeracy 1 scores, OLS

|

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

EU |

EU |

EU |

USA, CAN, AUS |

USA, CAN, AUS |

USA, CAN, AUS |

|

Native, foreign parents |

-15.56*** |

-14.12*** |

-12.43*** |

-3.162*** |

-1.972** |

0.336 |

|

Foreign, native language |

-14.72*** |

-15.25*** |

-15.95*** |

1.834 |

-13.43*** |

-15.81*** |

|

Foreign, foreign lang. |

-48.19*** |

-43.12*** |

-42.67*** |

-19.06*** |

-29.17*** |

-29.76*** |

|

Education levels |

23.56*** |

20.53*** |

29.11*** |

24.73*** |

||

|

Parents' education |

9.247*** |

12.22*** |

||||

|

Observations |

43,364 |

42,170 |

38,858 |

31,942 |

31,118 |

28,649 |

1. Robust standard errors in parentheses, *** p<0.01, ** p<0.05, * p<0.1.

2. Controlling for gender, age. With country FE.

3. EU selected countries: Belgium (Flanders), Netherlands, Denmark, France, Austria, the United Kingdom and Germany.

4. The reference category is the natives with native-born parents, speaking the native language at home. Source: PIAAC data.

Conclusion

This chapter has investigated the intergenerational transmission of education in EU and OECD countries. Three main outcomes were analysed: highest educational attainment, test scores in schools using PISA data, and adult skills measured by OECD PIAAC data. The educational disadvantage of the children of immigrants is documented for European countries, and also compared to non-European OECD countries.

In most European countries, children with immigrant parents perform less well in terms of educational outcomes compared to their peers without a migration background. However, differences in educational outcomes differ considerably across countries. In western continental European countries, the gaps are particularly large, whereas in the United Kingdom and in recipient countries such as the United States, Canada, Israel, Australia and New Zealand, the children of immigrants are either on a par with or perform better than the children of natives. This chapter has documented these gaps for each measure and each country.

In most western continental European countries, natives whose parents were born outside the EEA (natives with immigrant parents) are overrepresented at the bottom of the educational spectrum, and under-represented at the top. Therefore, it is no real surprise that their children have a much smaller educational gap from the parental generation, as compared to their peers with native-born parents. This indicates that from one generation to the next, the educational gap is narrowing. At the same time, natives with immigrant parents who are particularly of non-EU origin perform considerably less well in standardised tests such as PISA. By age 15, their skills are on average one year behind their native peers. Even after accounting for their parental socio-economic status, natives with immigrant parents still underperform. The children of more highly educated non-EEA immigrants also lag behind their peers with similarly highly educated parents. In addition, among the offspring of lower-educated parents, the children of natives are more likely to achieve higher test scores than the children of immigrants. The test score results suggest that it is more difficult for children with immigrant parents to navigate and succeed in the education system, compared to their peers with native parents.

In the United Kingdom, Ireland and the Baltic countries, these trends are different. The schooling gap in the parent generation is lower than in continental Europe and natives with immigrant parents overcome the lower educational background of their parents. This group reaches the same schooling levels as natives with native parents, and perform similarly in test scores at school. In recipient countries such as Canada, the United States and Australia, this trend is even stronger. Despite their parents having fewer years of schooling than native parents, these children catch up and reach the same years of schooling and test scores as their peers.

For individuals who were born in a given country, the education system has the potential to mitigate socio-economic disadvantages and its intergenerational transmission. Well-functioning schools, quality teachers, school autonomy and targeted support all contribute to a better school environment (OECD, 2015). Educational attainment is an important outcome to be considered, but the issues that students from disadvantaged backgrounds face begin long before education is about to be completed, and are likely to have long-term consequences. In other words, countries that are unable to mitigate the impact of socio-economic background during and prior to compulsory education may face greater challenges in ensuring equal opportunities for all once students enter the labour market.

References

Angrist, J.D., P.A. Pathak and C.R. Walters (2013), “Explaining charter school effectiveness”, American Economic Journal – Applied Economics, Vol. 5, No. 4, pp. 1‑27.

Becker, R., F. Jäpel and M. Beck (2013), “Diskriminierung durch Lehrpersonen oder herkunftsbedingte Nachteile von Migranten im Deutschschweizer Schulsystem?”, Swiss Journal of Sociology, Vol. 39, No. 3, pp. 517-49.

Behaghel, L., M. Gurgand and C. de Chaisemartin (2016), “Ready for boarding ? The effects of a boarding school for disadvantaged students”, American Economic Journal – Applied Economics, Vol. 9, No. 1, pp. 140-64.

Bertschy, K., E. Böni and T. Meyer (2008), “Young people in transition from education to labour market: Results of the Swiss youth panel survey TREE, Update 2007”, TREE, Basel, www.tree.unibe.ch/e206328/e305140/e305154/files307441/Bertschy_Boeni_Meyer_2007_Results_Update_en_ger.pdf (accessed 22 October 2017).

Bertschy, K., M.A. Cattaneo and S.C. Wolter (2009), “PISA and the transition into the labour market”, LABOUR, Vol. 23, Issue 1, pp. 111–137.

Birkelund, G.E. and A.S. Hermansen (2015), “The impact of immigrant classmates on educational outcomes”, Social Forces, Vol. 84, No. 2, pp. 615-46.

Black, S., P.J. Devereux and K.G. Salvanes (2013), “Under pressure? The effect of peers on outcomes of young adults”, Journal of Labor Economics, Vol. 31, No. 1, pp. 119-53, www.jstor.org/stable/10.1086/666872 (accessed 22 October 2017).

Bratsberg, B., O. Raaum and K. Røed (2011), “Educating children of immigrants: Closing the gap in Norwegian schools”, IZA Discussion Paper 6138, Institute for the Study of Labor (IZA).

Carrell, S.E., M.L. Hoekstra and E. Kuka (2016), “The long run effects of disruptive peers”, NBER Working Paper Series No. 22042, www.nber.org/papers/w22042 (accessed 22 October 2017).

Cedefop (2015) “Stronger VET for better lives, Cedefop’s monitoring report on vocational education and training policies 2010-14”, European Centre for the Development of Vocational Training, www.cedefop.europa.eu/en/publications-and-resources/publications/3067 (accessed 22 October 2017).

Chetty, R. and N. Hendren (2015), “The impacts of neighborhoods on intergenerational mobility : Childhood exposure effects and county-level estimates”, May, https://scholar.harvard.edu/files/hendren/files/nbhds_paper.pdf (accessed 22 October 2017).

Crocker, R., T. Craddock, M. Marcil and J. Paraskevopoulos (2010), National Apprenticeship Survey, 2007: Profile of Participants, Human Resources and Skills Development Canada, www.red-seal.ca/docms/nas_profiles_eng.pdf (accessed 22 October 2017).

Cunha, F. and Heckman J. (2010), “Investing in our Young People”, NBER Working Paper Series 16201, http://www.nber.org/papers/w16201.pdf , (accessed on 6 November 2017).

Curto, V.E. and R.G. Fryer (2014), “The potential of urban boarding schools for the poor : Evidence from SEED”, Journal of Labour Economics, Vol. 32, No. 1, pp. 65-93.

Dobbie, W. and R.G. Fryer (2013), “Getting beneath the veil of effective schools: Evidence from New York City”, American Economic Journal – Applied Economics, Vol. 5, No. 4, pp. 28-60.

Diehl, C., M. Friedrich and A. Hall (2009), “Jugendliche ausländischer Herkunft beim Übergang in die Berufsausbildung: Vom Wollen, Können und Dürfen”, Zeitschrift für Soziologie, Vol. 38, No. 1, pp. 48-67.

Dustmann, C., S. Machin and U. Schoenberg (2010), “Ethnicity and educational achievement in compulsory schooling”, The Economic Journal, Vol. 120, Issue 546 (August), pp. 272-97, http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0297.2010.02377.x.

European Union Labour Force Survey (EU-LFS) and its Ah-Hoc Module 2014.

Hadjar, A. and Hupka-Brunner, S. (2013), “Geschlecht, Migrationshintergrund und Bildungserfolg“, Beltz Juventa publishing, Weinheim.

Heath, A. and Cheun S. (2006). “Ethnic penalties in the labour market: Employers and Discrimination”, UK Department for Work and Pensions, Research Report Nr. 341, http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20130125104217/http://statistics.dwp.gov.uk/asd/asd5/rports2005-2006/rrep341.pdf , (accessed 06 November 2017).

Levels, M., J. Dronkers and G. Kraaykamp (2008), “Immigrant children’s educational achievement in Western countries: Origin, destination, and community effects on mathematical performance”, American Sociological Review, Vol. 73, Issue 5, pp. 835-53, http://doi.org/10.1177/000312240807300507, (accessed 22 October 2017).

Liebig, T., S. Kohls and K. Krause (2012), “The labour market integration of immigrants and their children in Switzerland”, OECD Social, Employment and Migration Working Papers No. 128, Directorate for Employment, Labour and Social Affairs, OECD Publishing, Paris.

Murdoch, J., C. Guégnard, M. Koomen, C. Imdorf and S. Hupka-Brunner (2014), “Pathways to higher education in France and Switzerland: Do vocational tracks facilitate access to higher education for immigrant students?”, in G. Goastellec and F. Picard (eds.), Higher Education in Societies: A Multi Scale Perspective, Sense Publishers, Rotterdam/Boston/Taipei, pp. 149-69.

OECD (2016), Skills Matter: Further Results from the Survey of Adult Skills, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264258051-en.

OECD (2015), “PISA: Programme for International Student Assessment”, OECD Education Statistics (database). http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/data-00365-en.

OECD (2015a), PIAAC: Programme for the International Assessment of Adult Competencies, PIAAC Data Explorer (database). http://piaacdataexplorer.oecd.org/ide/idepiaac/ .

OECD (2015b), Immigrant Students at School: Easing the Journey towards Integration, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264249509-en.

OECD (2012) Jobs for Immigrants (Vol. 3): Labour Market Integration in Austria, Norway and Switzerland, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264167537-en.

OECD/EU (2015), Indicators of Immigrant Integration 2015: Settling In, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264234024-en.

Picot, G. and F. Hou (2013), “Why immigrant background matters for university participation : A comparison of Switzerland and Canada”, International Migration Review, Vol. 47, No. 3, pp. 612-42.

Rangvid, B.S. (2012), “The impact of academic preparedness of immigrant students on completion of commercial vocational education and training”, AKF, Danish Institute for Governmental Research.

Scharenberg, K., M. Rudin, B. Müller, T. Meyer and S. Hupka-Brunner (2014) “Education pathways from compulsory school to young adulthood: Results of the Swiss panel survey TREE, Part I”, TREE, Basel, www.tree.unibe.ch/ergebnisse/e305140/e305154/files305155/Scharenberg_etal_2014_Synopsis_TREE_Results_Part-I_Education_en_ger.pdf, (accessed 22 October 2017).

Schnepf, V.S. (2007), “Immigrants’ educational disadvantage: An examination accross ten countries and three surveys”, Journal of Population Economics, Vol. 20, No. 3, pp. 527-45, http://doi.org/10.1007/ s00148-006-0102-y.

Annex 3.A. Measuring the evolution of the educational gap between groups of natives

A first and intuitive way of measuring the evolution of an educational gap is to compare it over time for a given age group (for example the 25-34 year-olds). Two steps are needed for measuring this evolution. The first step involves measuring the educational gap of the 25-34 year-olds in the year t (for example in year 2004). The second involves measuring the same gap of the 25-34 year-olds later in time, for example in year t+10 (in 2014), to ensure that each single person initially measured has left the cohort. This measures the evolution of the educational gap between one cohort and the next, using the following formula:

In the above formula, S stands for the average years of schooling, while the subscript N stands for natives’ children and the subscript NIP stands for the native children of immigrant parents. An alternative version of this first method would consist of measuring the educational gap for different cohorts at a given point in time. For example, measuring the educational gap between natives with immigrant parents and native’s children for the 18-24 year-olds, the 25-34 year-olds, and the 35-45 year-olds. This alternative method is in essence the same as the one described above, as it compares the gap between different cohorts. The chapter follows this alternative method first.

Yet the methodology chosen has a flaw: it does not control for the characteristics of the cohort in question. To take a hypothetical case: earlier immigrants are highly educated and consequently have highly educated children, while more recent immigrants are less educated, and therefore have less educated children. In this hypothetical case, one is likely to observe that the education gap, with respect to natives’ children, is increasing. This increasing gap will mostly be due to the fact that two cohorts with very different characteristics are compared. It could very well be that the education system is very inclusive, and improving its effectiveness in reducing educational gaps. However, this measure will not be able to capture that, as it will instead capture the differences in the cohorts’ characteristics.

Estimates will therefore be more insightful when taking into account parents’ education levels. In the context of rising average education, each new cohort has on average more years of schooling than the parents. The question is therefore whether children of immigrants exceeded their parents’ educational attainment to a greater extent than the children of natives. If natives with immigrant parents have many more years of education than their parents, while the increase in years of education compared to parents is smaller for the other natives, then the educational gap is closing. This evolution of the educational gap is hence measured using the following formula:

This second measure has two advantages. First, it takes into account parent’s educational attainment and second, it only requires data for a given year, as data on parents’ and children’s educational attainment can be taken from the same year. The EU-LFS has collected, in two ad hoc modules in 2008 and 2009, information on the educational attainment of each of the respondents’ parents. Using the 2008 and 2009 EU-LFS data therefore permits linking the parent’s and the respondent’s educational attainment, and provides this second measure of how the educational gap has evolved.

The third way is to use an econometric approach. A regression on schooling attainment takes into account parental schooling attainment and migration category. This approach can answer the question of whether immigrants’ children are disadvantaged in terms of educational attainment, holding parental education constant. The regression not only reports the intergenerational transmission of education, but also indicates whether immigrants’ children are at a specific disadvantage (or advantage) compared to natives’ children. Thus, the regression estimated is:

where S_i stands for the years of schooling of person i. The intergenerational transmission of education is captured through the coefficient β_1, while β_2 captures whether children of immigrants are on average less educated after accounting for parental background. The interaction between parental schooling and being the children of immigrants reports whether the association between parental and child education is different for the children of immigrants compared to the children of natives. There is no “preferred” or “best” methodology. The chapter utilises all three methodologies, as each one shows a different facet of the evolution of the educational gap.

Annex 3.B. How well do PISA scores predict later achievements of native students with immigrant parents?

PISA test scores are generally regarded as a rather precise measure of students’ skills and labour market preparedness. However, there is little longitudinal evidence available on how predictive PISA scores are of future academic advancement and labour market outcomes among youth with a migration background. The Transition from Education to Employment (TREE) data set is a notable exception. It covers approximately 6 000 students who participated in the Swiss PISA test in 2000 and follows their transition from compulsory schooling to work or further education in seven annual waves until 2007, with two further follow-ups in 2010 and 2014. TREE not only provides detailed information on educational outcomes and employment trajectories, but also registers the country of birth of respondents and their parents. As such it has been widely used to study school-to-work transition among youth with a migration background in Switzerland – investigating, for instance, the impact of discrimination (Becker, Jäpel and Beck, 2013), gender (Hadjar and Hupka-Brunner, 2013) and vocational training (Murdoch et al., 2014).

Bertschy, Böni and Meyer (2008) observe educational outcomes six years after the PISA test and find that generally, literacy at age 15 and socio-economic background are the most strongly predictive factors for educational trajectories. Having low reading skills and low socio-economic status increase the likelihood of dropping out by the factor of 2.8 and 2.7, respectively. Youth with fathers from the Balkans, Turkey or Portugal are found to be three times more likely (20%) to drop out of post-secondary education, including apprenticeship schemes, than those with native-born fathers (7%). However, when controlling for socio-economic status and reading scores, their father’s country of birth becomes insignificant. For students who successfully finished their vocational education, neither immigrant status – here operationalised as having two parents born abroad – nor language spoken at home had a significant influence on the likelihood of finding a job with a matching skill level (Bertschy, Cattaneo and Wolter, 2009). PISA reading scores, however, were found to be a significant factor in finding employment: scores of graduates who found employment had on average 30 points higher than those of unemployed graduates.