Transparency is one of the central pillars of effective regulation, supporting accountability, sustaining confidence in the legal environment, making regulations more secure and accessible, less influenced by special interests, and therefore more open to competition, trade and investment. It involves a range of actions including standardised procedures for making and changing regulations, consultation with stakeholders, effective communication and publication of regulations and plain language drafting, codification, controls on administrative discretion, and effective appeals processes. It can involve a mix of formal and informal processes. Techniques such as common commencement dates can make it easier for business to digest regulatory requirements. The contribution of e‑government to improve transparency, consultation and communication is of growing importance.

Regulatory Policy in Slovenia

Chapter 4. Stakeholder engagement and access to regulations

Abstract

Stakeholder engagement and public consultations

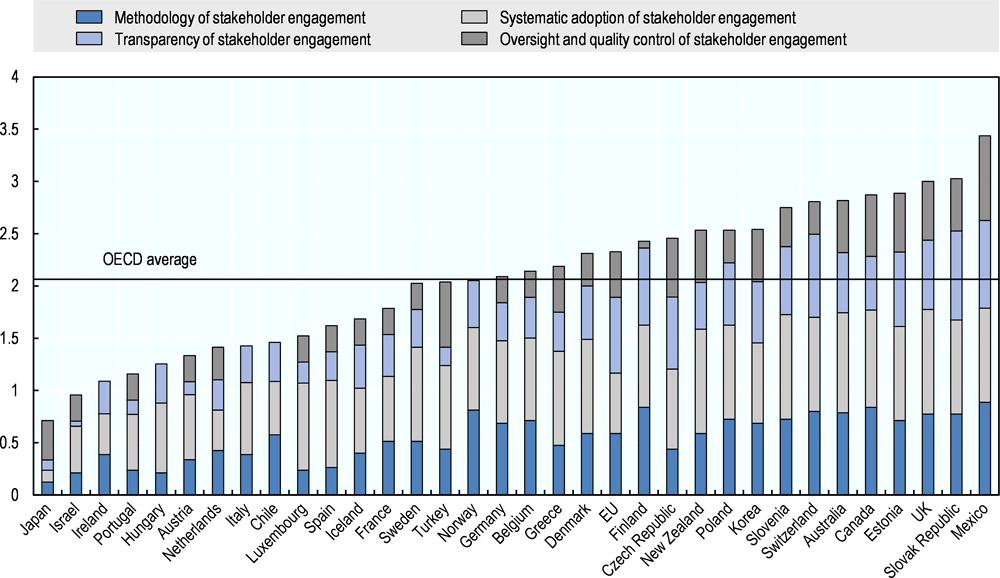

There is no government-wide, general policy on stakeholder engagement in drafting, implementing and reviewing regulations. There are, however, a number of legal and policy documents setting the formal obligation to engage with stakeholders, especially in the process of developing new regulations. Having in place these formal requirements is behind that fact that Slovenia scored relatively high in the 2014 OECD Indicators of Regulatory Quality (Figure 4.1 and Figure 4.2).

Figure 4.1. Stakeholder engagement in developing primary laws

Notes: The results apply exclusively to processes for developing primary laws initiated by the executive. The vertical axis represents the total aggregate score across the four separate categories of the composite indicators. The maximum score for each category is one, and the maximum aggregate score for the composite indicator is four. This figure excludes the United States where all primary laws are initiated by Congress. In the majority of countries, most primary laws are initiated by the executive, except for Mexico and Korea, where a higher share of primary laws are initiated by parliament/congress (respectively 90.6% and 84%). See the Annex 8.C for a description of the methodology of the iREG indicators.

Source: 2014 Regulatory Indicators Survey results, www.oecd.org/gov/regulatory-policy/measuring-regulatory-performance.htm.

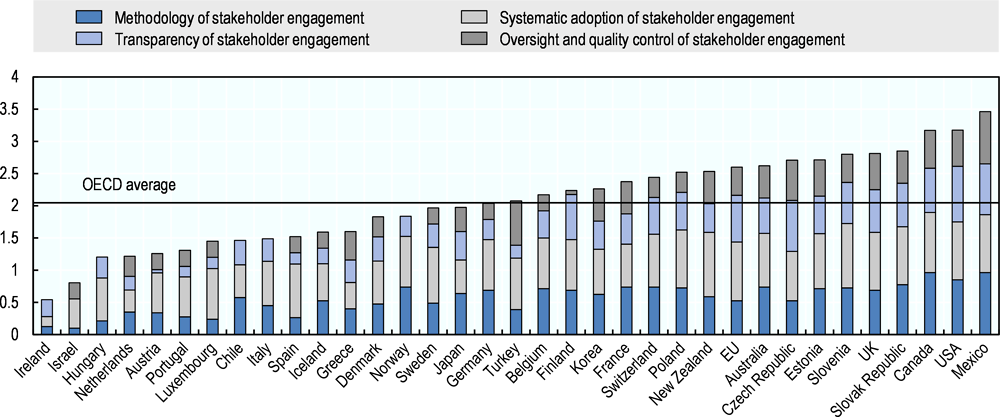

Figure 4.2. Stakeholder engagement in developing subordinate regulations

Note: The vertical axis represents the total aggregate score across the four separate categories of the composite indicators. The maximum score for each category is one, and the maximum aggregate score for the composite indicator is four.

Source: 2014 Regulatory Indicators Survey results, www.oecd.org/gov/regulatory-policy/measuring-regulatory-performance.htm.

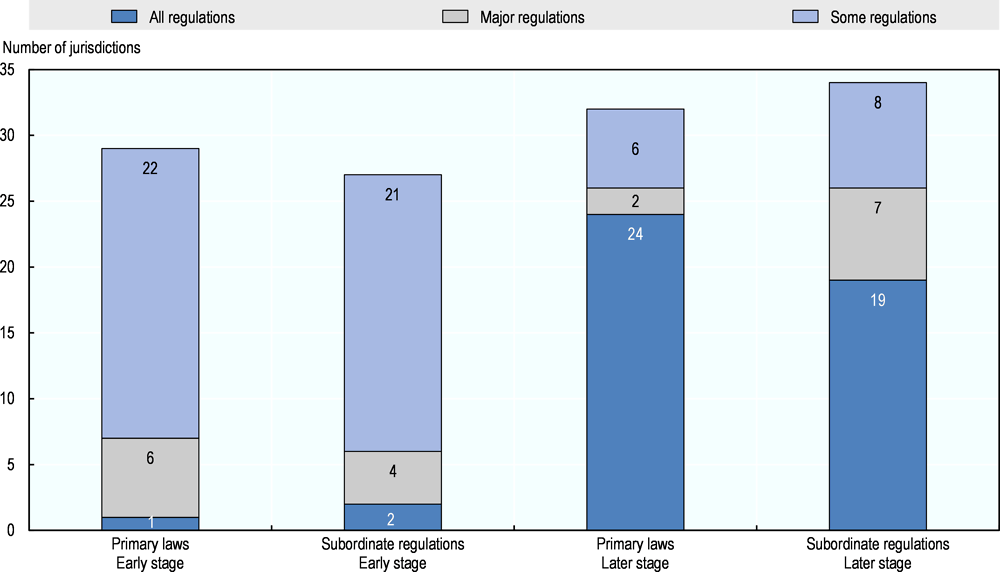

Formally, consultations with outside stakeholders are compulsory for all primary and subordinate regulations. Some ministries organise consultations early in the legislation-making process with the use of green papers, consultation documents, public hearings, etc. However, most of the consultations take place late in the process, when a regulatory draft is almost ready and there might be limited willingness on the side of the administration to substantively change it. As Figure 4.3 shows, this is still the case in many OECD countries.

Figure 4.3. Early stage and later stage consultations on regulatory drafts

Source: OECD Indicators of Regulatory Policy and Governance (iREG), www.oecd.org/gov/regulatory-policy/indicators-regulatory-policy-and-governance.htm.

The Resolution on Legislative Regulation, adopted by the National Assembly on 19 November 2009, represents a commitment to involve general public in developing policies and drafting new regulations, however, it is not binding for the government. The Resolution sets the following principles for stakeholder engagement in the legislation-making process:

Timeliness: the public (including experts, interested parties and general public) should be informed of newly prepared policies and regulations sufficiently in advance, ensuring reasonable time for their involvement in the process (including review of the draft and supporting materials and preparation of comments, opinions and proposals for change);

Openness: public administration must enable the submission of comments, suggestions and opinions at the earliest possible stage in the regulation-making process;

Accessibility: supporting materials and expert analyses used in the preparation of the regulatory draft should be made available to the consulted subjects;

Responsiveness: consultees must be informed about the reasons for the acceptance or rejection of their comments, suggestions and opinions;

Transparency: not just the regulatory draft and the accompanying documents, but also the decision-making process (its length, ways of involvement of stakeholders) should be presented in a transparent matter. All comments, suggestions and opinions provided should be also made available;

Traceability: possibility of tracing received proposals, comments and opinions back to their sources, transparency of documents which result from the engagement process itself (i.e. minutes from meetings and public hearings).

Besides these general principles, the Resolution also sets minimum standards for stakeholder engagement processes:

Public consultations when drafting new regulations should last between 30 and 60 days (with some exceptions – urgent matters, regulations on the state budget, declarations, proposals of acts on the ratification of international treaties);

Explanatory documents should be drafted that summarise the draft, its key objectives and main issues to be solved and the background expert analysis;

A report summarising public consultations, including impacts on the draft, should be published at the end of the process;

Public consultations should be carried out in a way that ensures the response of all interested subjects and relevant experts, as well as the general public.

The Rules of Procedure of the Government of the Republic of Slovenia were amended in 2010, with a special focus on the process of impact assessment and stakeholder engagement. The technical aspects of these provisions were included in the Instruction No. 10 for Implementing the Provisions of the Rules of Procedure of the Government of the Republic of Slovenia. The Instruction specifically defines the content of a government material and the process of its preparation.

According to the Instruction, when drafting regulations, the drafting institution shall invite experts and general public to participate in public consultations organised through the dedicated government portal eDemocracy (see below). The deadline for submitting comments should be set to between 30 and 60 days from the publication of the draft. Besides public consultations, the drafting institution might individually address specific organisations, individual experts or stakeholders with a request to submit comments on the whole draft or specific issues. The drafting institution should inform those submitting comments in writing in case their significant comments were not taken into consideration including justification of why this was the case. The Instructions also sets exceptions from the process of public consultations (national budget, measures adopted under the emergency procedure, acts ratifying international treaties, etc.).

When a regulatory draft is published on the government website, the dossier should include the draft itself; all accompanying analyses including RIA, key issues and objectives; and the deadline for submitting comments including contacts. In case there will be a public hearing organised, the information on the date and a place should also be part of the dossier. The fact that stakeholders have a possibility to comment not just on the draft but also on other accompanying documents such as RIA is a good practice among OECD countries (see the example of Mexico in Box 4.1).

Box 4.1. Consultation as part of the RIA process in Mexico

Regulatory Impact Assessment (RIA) is conducted systematically in Mexico for all regulations issued by the Executive Branch of Government that impose compliance costs on the private sector and citizens. After ministries and regulatory agencies have prepared a regulatory proposal and an accompanying RIA, the RIA is formally submitted to the Federal Commission for Regulatory Improvement (COFEMER) in electronic format for scrutiny, and automatically published in COFEMER’s online system for publishing and consulting on RIAs (SIMIR).

Stakeholders can provide comments on the draft proposal and the RIA. The general public can comment through the COFEMER consultation portal or send comments via e-mail, fax, or letters. Consultations are required to be open for at least 30 working days before the intended date of their issuance. In practice, much longer consultation periods are the norm. Besides the public online consultation process, COFEMER also uses other means to consult with stakeholders. These include advisory groups, media and social networks (tweets) to diffuse the regulatory proposals and promote participation.

Stakeholder comments are published on the COFEMER website and required to be taken into account by COFEMER and the agency sponsoring the regulation. COFEMER is obliged to take into account all comments received during the consultation process for its official opinion on the RIA. The sponsoring agency must provide a reply to each comment received during the consultation respond to the official opinion of COFEMER. Once a satisfactory response has been received, the COFEMER certifies the RIA as final and the regulatory process proceeds. In practice, regulators’ responses to the COFEMER’s comments on the draft RIA frequently fail to address adequately all of the concerns raised in relation to the analysis. In such circumstances, the revised draft may be deemed by the COFEMER to constitute another draft RIA rather than a final document and a second round of consultation is conducted.

Documentation on the consultation processes are publicly available. Each regulatory proposal has its file on the SIMIR system, which includes a summary of all documents received and issued (e.g. comments, opinions). Hence, the file shows the “life story” of a regulatory proposal, including how the regulatory draft was modified during the regulatory review process and how comments influenced the draft during public consultation. In addition, COFEMER’s annual reports summarise information on the consultation processes, including information on the number of comments received grouped by government agency, and whether the comments were submitted by the private sector, government agencies or the general public.

Source: OECD Pilot database on stakeholder engagement practices in regulatory policy. www.oecd.org/gov/regulatory-policy/pilot-database-on-stakeholder-engagement-practices.htm.

The Instruction also sets an important exception from public consultations based on a request from the drafting institution. A minister or director of a government office may submit a request to the Secretary General of the Government that a regulatory draft is submitted to the Government without going through the consultation process in cases where there is an “urgent need” to adopt such a proposal. The reasons for such a request have to be provided. The term “urgent need” is, however, defined rather vaguely. Therefore, according to the analysis done by the Ministry of Public Administration, a large proportion of regulatory drafts actually use this “shortcut”.

To complement the regulatory framework for stakeholder engagement described above and as a result of the “Strengthening the capacity to implement the impact assessment of regulations and integrate the public in the preparation and implementation of public policies” project (Box 4.2), the Ministry of Public Administration prepared two additional guidance documents – the Manual for planning and implementation of consultative processes and Guidelines for stakeholder involvement in the preparation of regulations.

Box 4.2. Strengthening the capacity to implement the impact assessment of regulations and integrate the public in the preparation and implementation of public policies

With the aim of improving quality and efficiency of public participation in drafting regulations, the Ministry of Public Administration of the Republic of Slovenia carried out the project called “Strengthening the capacity to implement the impact assessment of regulations and integrate the public in the preparation and implementation of public policies”. The project was carried out in co-operation with a number of different stakeholder groups, including CNVOS (Centre for information service, co-operation and development of NGOs), Chamber of Commerce and Industry of Slovenia, Chamber of Craft of Slovenia, trade unions.

In the context of the implementation of the project trainings of public officials on the planning and implementation of consultative processes were carried out in the period between February and May 2015. The result of trainings is more than 130 basic-skilled public servants and 18 trainers who are responsible for the training of public servants in ministries where they are employed.

In the context of the project, new Manual for planning and implementation of consultative processes and Guidelines for stakeholder involvement in the preparation of regulations were prepared.

Source: Information provided by the Government of Slovenia.

The Manual focuses on the organisation of the process of public consultations, including careful planning of public consultation processes, setting their objectives, mapping and identification of potential stakeholders, selection of consultation methods and tools, collection of input and their analysis and processing, drafting on reports and, rather importantly, evaluation of consultation activities. The Manual includes helpful good practice examples from the Slovenian practice.

The Guidelines provide instructions on individual steps of the consultation process. The Guidelines, among other issues, instruct those drafting regulations to consult with general public electronically before a legislative text is actually drafted as well as at the end of the process. Experts and interested parties should be, according to the Guidelines, consulted throughout the whole regulation-making process, not just at its end.

It is not entirely clear, why there are two separate guidance documents, on top of several legal documents covering public consultations. While providing guidance and technical assistance to those involved in the consultation processes is certainly useful, having a plethora of binding and non-binding documents might be actually confusing and counter-productive.

Open public consultations usually take place through the Government's eDemocracy1 portal. All regulatory drafts prepared at the level of the executive are published through the portal. Potential consultees can present their comments and views on the draft through the portal. The list of regulations is searchable by the title of the draft, responsible institution, area of regulation, etc. Most of the drafts that are published through the eDemocracy portal are in the final stage of preparation, however, the portal enables to publish drafts at any stage of the regulation-drafting process. The portal allows the public to follow the regulation making process through 'statuses' that are refreshed automatically as a regulation draft makes its way through different stages of the process. It also offers users the chance to subscribe to any news regarding regulation from areas that might interest them. The users then regularly receive e-mails with information regarding what regulation and which area are to be a subject of change and additional information on changes when they occur. Regarding its functionality, the portal is in line with the OECD best practice.

The project has a strong support of the CNVOS (Centre for information service, co-operation and development of NGOs) which has a strong advocating and supervisory role in the field of stakeholder engagement.2

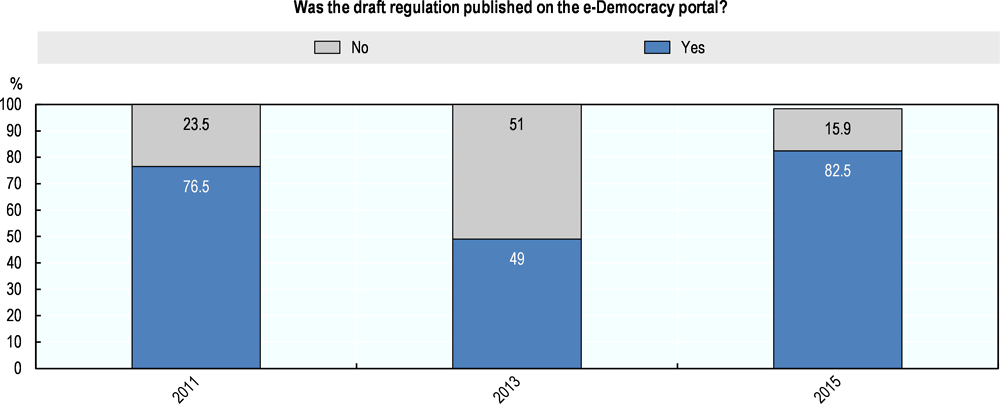

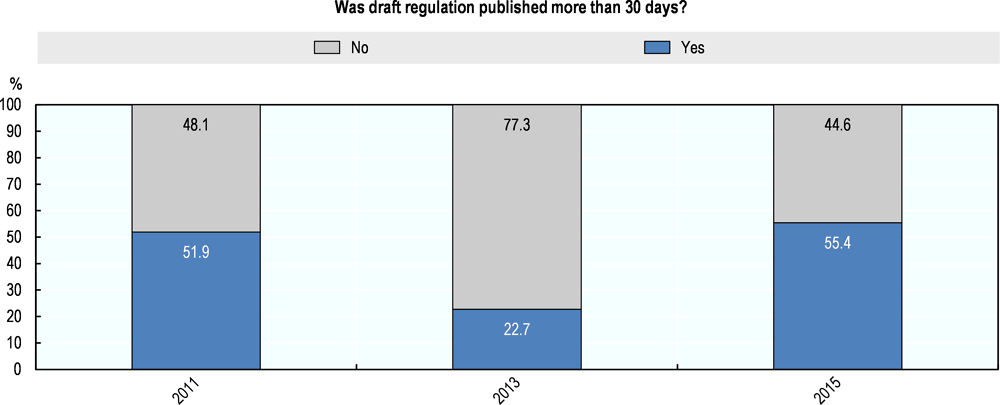

The data provided by the Slovenian government show that the number of regulatory drafts that are published on the eDemocracy portal has been growing with a dip in 2013 (Figure 4.4). Most of the drafts are now consulted through the portal, however, the 30 days minimum time for publication is not respected in almost half of the cases (Figure 4.5).

Figure 4.4. Number of regulations published on the e-Democracy portal

Notes: In 2013, because of the economic crisis, Slovenia experienced a short period of political instability and government change. This led to an increase of regulations adopted through the fast-track procedure, where public consultation is not necessary.

Source: Analysis of the Ministry of Public Administration.

Figure 4.5. Number of days regulatory drafts are published through the eDemocracy portal

Source: Analysis of the Ministry of Public Administration.

When the draft is submitted to the government, the drafting institution has to, according to the Instruction No. 10, summarise the consultation process in the letter accompanying the submission to the government. It has to state whether the draft has been published on the eDemocracy portal (and if not, provide reasons why), and to list all stakeholders that provided comments and their suggestions. In case of “substantial”3 comments, the letter must provide reasons for disregarding these comments.

The drafting institution should also publish a summary of the process of public consultations, including the ways how the proposal was communicated to stakeholders (portals, public hearings), and a list of 'substantial' comments received. The summary is part of the dossier published on the government portal as well as on the website of the National Assembly.

Using the SME Test (an electronic tool to evaluate impacts of regulatory drafts) by individual stakeholders represents an interesting innovation in the area of stakeholder engagement. When a draft is published on the eDemocracy portal (including its impact assessment), those commenting on the draft might use the SME Test to evaluate impacts of the alternatives proposed by themselves. The analysis might then be used as a supporting argument for their suggestion.4

In addition to the above mentioned documents, the Access to Public Information Act also stipulates that public authorities must inform the public about their work to the greatest extent possible, including publication of regulatory drafts. The Act also sets the obligation to publish information on external experts that were involved in the preparation of any regulation that had entered into force. Article 7 of the implementing regulation and the Decree on communication and re-use of public sector information, stipulate that official bodies must publish draft regulations, programmes, strategies and other documents on the internet for purposes of public announcement and consultation with the public and key stakeholders, and that regarding the method and deadlines, the provisions of the resolution governing regulatory activities and the Government Rules of Procedure should be applied mutatis mutandis.

The Access to Public Information Act also regulates the co-operation of representative trade unions in the procedure of adopting legal acts on the national level. The Government or competent minister must enable representative trade unions of the branch or professions in state bodies and local community administrations to give their opinion prior to the adoption of any regulation that affects the working conditions or status of civil servants in state bodies and local community administrations.

The Access to Public Information Act also regulates social partnership on the level of individual bodies. Prior to the adoption of a general act that affects the rights or duties of civil servants, the head of the body must also enable the representative union working in the body to offer an opinion. The Government or competent minister must send the draft regulation or act to the representative unions and set a reasonable deadline for them to formulate an opinion. The length of the deadline depends on the complexity and scope of the regulation being considered. If a union gives its opinion or remarks, they must be considered, or the union must be invited to participate in harmonisation. If regarding certain issues no harmonisation is achieved, a written explanation must be given as to why the union’s opinion was not taken into account and the explanation must be sent to the unions.

Institutional set up for overseeing the quality of stakeholder engagement

There is no specific body with a gatekeeping function overseeing the quality of stakeholder engagement processes. Formally, compliance with the Rules of Procedure of the Government is checked by the General Secretariat of the Government, however, it does not have enough powers nor capacities to control the actual quality and completeness of the engagement processes (see Chapter 3 for more information).

Stakeholder engagement in reviewing regulations

There is no binding policy on how to involve stakeholders in the process of reviewing regulations. It is left to the discretion of the ministries and government agencies whether they consult the regulated subjects and discuss potential issues with the quality of the regulatory framework. Some ministries have regular contact with stakeholders, especially businesses operating in the sectors regulated by those ministries (i.e. the Ministry of Economic Development and Technology, Finance or Agriculture). It is not, however, a general rule.

To open a channel for citizens, businesses and other stakeholders to communicate with the government and its institutions and to identify potential issues with the regulatory framework, the government created a website in 2009 called "predlagam.vladi.si" (mysuggestion.gov.si). The portal is run by the Government Communication Office (UKOM), a service that mediates information between the government, its representatives, public agencies, and different members of the public. The portal working with software originally developed for the Estonian government had, in its first five years, almost 13 000 registered users which contributed with 5 000 suggestions (on average 3 per day). The individual proposals might be commented on and can also receive positive and/or negative votes. 1 675 suggestions (33%) received the required level of support and were submitted for government response. Policy makers are required to contribute to the discussion on the portal as well. So far, around two dozens of suggestions have been implemented which is a relatively low number compared to the number of suggestions. There is no formal mechanism on how to make sure that those suggestions receiving positive votes will be dealt with.

Another electronic tool that might be used by stakeholders to contribute to improving regulatory framework is the portal Stop Birokraciji (Stop the Bureaucracy). Through his portal, stakeholders may submit their proposals for reducing administrative burdens and simplifying administrative procedures. When a proposal is published on the portal, it is assigned to a responsible ministry that has to provide feedback which is then published on the portal. All comments are published and available on the portal by publishing the status of an individual proposal, whereby sorting according to individual fields or competent ministries considering the individual regulation to which a proposal/comment refers is also available. Currently the database includes 470 initiatives, 387 are already closed and accepted. Measures that the competent ministry considers to be appropriate for implementation and are included in its programme of work are also included in the Single Collection. Proposers can monitor the progress and the state of implementation of the proposed measure through the website.

Access to regulations

All regulations (including primary laws and secondary regulations) are published through the Legal Information System of the Republic of Slovenia5 administered by the Government Office for Legislation. The portal provides free access to the rules and other general acts in force and applicable to the territory of the Republic of Slovenia, along with links to the regulations of the European Union and the case law of the Republic of Slovenia, and other relevant information in connection the law of the Republic of Slovenia. All regulations are also published on the websites of the line ministries.

Assessment and recommendations

The Slovenian legal and policy framework creates conditions for efficient stakeholder engagement in regulatory policy, especially with regard to developing new regulations and their amendments. However, there is a substantial need to strengthen the enforcement of this framework, which is not often adhered to, to the extent that would enable successful engagement of stakeholders in the process of developing, implementing and reviewing regulations. This is similar to the situation concerning other regulatory management tools, such as the regulatory impact assessment.

Although some of the ministries engage with stakeholders early in the regulation-making process, this is still not systematic and mostly left to their discretion.

There is no systematic policy on engaging stakeholders in the process of reviewing existing regulations. While some ministries are in regular contact with regulated subjects, it is not a general rule. The portal “predlagam.vladi.si” could serve as a useful tool in this regards. However, as the experience of the United Kingdom shows (see Box 4.3), in case of such initiatives, formal mechanisms have to be established to make sure that proposals received through such portals are seriously considered by responsible ministries and, if possible, implemented.

Box 4.3. UK Red Tape Challenge

The Red Tape Challenge was run by the UK Government between 2011 and 2014 and aimed to reduce “cost to business” by removing regulatory burdens unless they could be justified. Specifically, the objective was to scrap or improve at least 3 000 regulations and save GBP 850m per year for business. The Red Tape Challenge was designed to crowdsource the views from businesses, organisations and the public on which regulations should be improved, kept or scrapped. It invited the general public to comment via the internet on the usefulness of regulations within a set time limit. People could comment both publically through comments on the website or through a non-public e-mail inbox.

The initial scope included 21 000 statutory rules and regulations and the enforcement of regulations. Regulations in relation to tax or national security were excluded. The consultations during the Red Tape Challenge finally covered 5 662 regulations. These were clustered in 28 themes and over 100 sub-themes. Six themes covered general regulations (e.g., equalities, environment) and were open throughout the entire time. Twenty themes covered a specific sector or industry and were open for consultation over several weeks each (“Theme Spotlight”). Two additional themes covered “Disruptive Business Models/Challenger Businesses” and “Enforcement” and were open for consultation during dedicated periods.

Over 30 000 comments from the public were received during the Red Tape Challenge, which were scrutinised by government and external actors. The responsible departments had 5-6 weeks to deliver proposals and arguments on whether to scrap, modify, improve or keep regulations. These proposals were challenged internally by so-called “Tiger Teams” made up of departmental staff who would review their own policies independently of the Red Tape Challenge, and externally by “Sector Champions” representing businesses, industries and stakeholder groups, as well as business panels. The proposals were then reviewed in the “Star Chamber”, which was chaired by the Cabinet Office and Business, Innovation and Skills ministers and involved key government advisors. The Star Chamber then issued a recommendation to which departments could respond. Finally, the Cabinet sub-committee decided on actual changes, supported by other Cabinet sub-committees where necessary.

The Red Tape Challenge has resulted in a range of regulatory changes. 3 095 regulations were to be scrapped or improved. 1 376 of the changes made had a material benefit (where “the reform has an impact for business/civil society, individuals or the taxpayer and that is over and above tidying the statute book”). Scrapped or improved regulations are reported to have led to annual savings for businesses over GBP 1.2 billion.

Source: OECD Pilot database on stakeholder engagement practices in regulatory policy. www.oecd.org/gov/regulatory-policy/pilot-database-on-stakeholder-engagement-practices.htm.

The access to regulation is in line with the OECD best practice, all regulations in force are available electronically through the government portal with free access. Links to international regulations including the EU legislation are provided.

A body close to the centre of government should be held responsible for controlling the quality of the stakeholder engagement process in developing new regulations. This could be closely linked to the process of checking the quality of the impact assessment process.

The body should make it clear whether the draft was sufficiently discussed with all interested parties (or whether they were given sufficient opportunity to comment) and whether all respective timelines for consultations were adhered to. This information should be made public and should be available to the government in the moment of discussing the proposal.

The government policies on stakeholder engagement should be updated so they cover also the process of reviewing and enforcing regulations. For the moment, the policy only covers the process of developing new or amending existing regulations. The policy should make it clear that when reviewing the existing regulatory framework, stakeholders’ views should always be taken into account (see the example of the European Commission, Box 4.4).

Box 4.4. Stakeholder engagement throughout the policy cycle at the European Commission

Following the adoption of the 2015 Better Regulation Guidelines, the European Commission has extended its range of consultation methods to enable stakeholders to express their view over the entire lifecycle of a policy. It uses a range of different tools to engage with stakeholders at different points in the policy process. Feedback and consultation input is taken into account by the Commission when further developing the legislative proposal or delegated/implementing act, and when evaluating existing regulation.

At the initial stage of policy development, the public has the possibility to provide feedback on the Commission's policy plans through roadmaps and inception impact assessments (IIA), including data and information they may possess on all aspects of the intended initiative and impact assessment. Feedback is taken into account by the Commission services when further developing the policy proposal. The feedback period for roadmaps and IIAs is four weeks.

As a second step, a consultation strategy is prepared setting out consultation objectives, targeted stakeholders and the consultation activities for each initiative. For most major policy initiatives, a 12 week public consultation is conducted through the website “Your voice in Europe” and may be accompanied by other consultation methods. The consultation activities allow stakeholders to express their views on key aspects of the proposal and main elements of the impact assessment under preparation.

Stakeholders can provide feedback to the Commission on its proposals and their accompanying final impact assessments once they are adopted by the College. Stakeholder feedback is presented to the European Parliament and Council and aims to feed into the further legislative process. The consultation period for adopted proposals is 8 weeks. Draft delegated acts and important implementing acts are also published for stakeholder feedback on the European Commission’s website for a period of 4 weeks. At the end of the consultation work, an overall synopsis report should be drawn up covering the results of the different consultation activities that took place.

Finally, the Commission also consults stakeholders as part of the ex post evaluation of existing EU regulation. This includes feedback on evaluation roadmaps for the review of existing initiatives, and public consultations on evaluations of individual regulations and 'fitness checks' (i.e. “comprehensive policy evaluations assessing whether the regulatory framework for a policy sector is fit for purpose”). In addition, stakeholders can provide their views on existing EU regulation at any time on the website “Lighten the load – Have your say”.

Source: OECD Pilot database on stakeholder engagement practices in regulatory policy. www.oecd.org/gov/regulatory-policy/pilot-database-on-stakeholder-engagement-practices.htm.

At the same time, the Government should consider codification of the different legal and policy documents governing stakeholder engagement. It should be made clearer which provisions are obligatory and which ones have only a guidance character.

Better links should exist between bodies developing new regulations and institutions responsible for their enforcement (regulators, inspections). These might have valuable insights on the level of compliance with regulations and potential issues with the regulatory framework that might lead to not achieving the desired regulatory outcomes.

Bibliography

Divjak, T. and G. Forbici (2014), “Public Participation in the Decision Making Process: International Analysis of the Legal Framework with a Collection of Good Practices”.

OECD (2018, forthcoming), OECD Best Practice Principles on Stakeholder Engagement in Regulatory Policy, OECD Publishing, Paris.

OECD (2012a), Recommendation of the Council on Regulatory Policy and Governance, OECD Publishing, Paris, www.oecd.org/gov/regulatory-policy/2012-recommendation.htm.

OECD (2012b), Slovenia: Towards a Strategic and Efficient State, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264173262-en.

Notes

← 2. CNVOS is national NGO umbrella network providing support through information service, consultancy, education, research, policy making, advocacy, networking and promotion. CNVOS regularly monitors proposed changes of legal acts and provides comments and proposals from NGO sector’s point of view. Since 2009, CNVOS advocacy experts have been monitoring the openness of the governmental institutions toward the public and NGOs in policy making within the framework of the project ‘The Mirror to the Government’. With special Counter of breaches (www.stevec-krsitev.si/ in Slovene) they count in how many cases and how severely different state bodies breached consultation deadlines that are set in the Government’s rules of procedure (www.cnvos.si/article?path=/english/about_cnvos/cnvos_in_a_nutshell).

Counter of breaches shows the total number of draft regulations by individual ministries, the total number of proposals where the Resolution was violated; number of proposals put to public debate without deadline for comments; number of proposals put to public debate with a deadline for comments shorter than 30 days; number of proposals not put to public debate and total percentage of violations. The statistics is updated on a weekly basis (every Monday).

Based on the Counter of breaches the Resolution was not complied with in 59% (1 452 regulations) in this mandate (from 18 September 2014 until today).

← 3. Those that are not considered as unrelated, undefined or derogatory.

← 4. The SME Test should be available as of October 2017.