Over the period 2012‑2016, French ODA fell from 0.45% to 0.38% of gross national income (GNI), and its geographical allocations did not reflect its stated priority countries for co‑operation. Furthermore, French humanitarian aid, action in fragile contexts, support for NGOs and gender equality still do not inadequately reflect France’s stated ambitions. On the other hand, France has focused its multilateral assistance on a few agencies through which it pursues its priorities, it has successfully developed innovative development financing mechanisms, and it now has a wide range of instruments capable of catalysing private sector development. France has pledged to devote 0.55% of its GNI to ODA in 2022. In order to achieve this target whilst still ensuring coherence with its geographical and thematic priorities, it will need to increase its donor‑driven bilateral aid significantly, and has planned to do so.

OECD Development Co-operation Peer Reviews: France 2018

Chapter 3. Financing for development

Abstract

Overall ODA volume

Peer review indicator: The member makes every effort to achieve ODA domestic and international targets

Over the period 2012‑2016, French ODA fell from 0.45% to 0.38% of its gross national income (GNI), and its geographical allocations did not reflect its stated priority countries for co‑operation. France has pledged to spend 0.55% of its GNI on ODA between now and 2022, which is an increase in ODA of almost EUR 6 billion compared with 2016. In order to achieve this target whilst still ensuring coherence with its geographical and thematic priorities, it has planned and will need to increase its donor‑driven bilateral aid significantly and issue the necessary commitment authorisations by 2020 at the latest.

The volume and distribution of ODA between 2012 and 2016 do not reflect France’s commitments

Over the review period (2012-2016), the amount and distribution of ODA did not reflect French pledges and priorities, especially as regards the total amount, least‑developed countries, priority countries and humanitarian aid. As Figure 3.1 shows, the decrease in total French ODA from USD 10.6 billion to USD 9.6 billion over the period is principally due to the decrease in bilateral grants (OECD, 2018a). The ODA/GNI ratio also decreased from 0.45% to 0.38% over the same period, even though it recovered in 2016 as compared with 2014 and 2015 (0.37%, its lowest level since 2001). In 2016, France was ranked fifth among DAC countries in terms of total ODA and in 12th place in terms of ODA/GNI ratio (Figure B.1).

Figure 3.1. Evolution of the make‑up of French ODA, 2012‑16

France relies heavily on its loan instrument, which accounted for 28% of total gross ODA (and 45% of gross bilateral ODA) in 2016, compared to 12% of total gross ODA (and 16% of gross bilateral ODA) for the whole of the DAC (Annex B, Table B.2). Each year during the period 2012‑16, the grant element of French ODA loans remained below the threshold of 90%, which is the DAC recommended grant element for loans to LDCs. In fact, the grant element actually decreased from one year to the next even though this was already identified as a weakness of French co‑operation during the last peer review (OECD, 2014). The AFD growth model is loan‑based; in 2016, 64% of the agency’s ODA portfolio consisted of loans. This model encourages it to invest in middle‑income countries to the detriment of less‑developed countries, and in potentially profitable sectors to the detriment of social sectors. This goes some way towards explaining the difference between the stated priorities and actual allocations of French ODA. In order to reverse this tendency, AFD could significantly increase the grant element of its portfolio (Section 3.2) (National Assembly, 2017b; Coordination SUD, 2017b).

France has pledged to commit 0.55% of its GNI as ODA by 2022

In July 2017, President Emmanuel Macron pledged that France would commit 0.55% of its GNI as ODA by 2022. That would increase French ODA from EUR 8.5 billion (0.38% of GNI) in 2016 to around EUR 14.5 billion by 2022 – in other words by nearly EUR 6 billion (MEAE, 2018b; National Assembly, 2017a). That commitment was reiterated at the meeting of the Interministerial Committee on International Co‑operation and Development (CICID) on 8 February 2018. This is the first step towards achieving the target of increasing ODA to 0.7% of GNI by 2030 – a target to which France recommitted itself in connection with the 2030 Sustainable Development Agenda. In order to achieve the intermediate target of 0.55%, whilst ensuring coherence with its geographical and thematic priorities, France will need to increase its state‑driven bilateral aid.1

France has set itself clear targets in this area: it has decreed, inter alia, that two‑thirds of the cumulative rise in ODA commitment authorisations between now and 2022 will be allocated to bilateral aid (MEAE, 2018a). As a corollary to the increase in state‑driven bilateral aid, the amount of grants making up bilateral aid will also increase. Although France has presented an overall budget trajectory (annual change in the ODA/GNI ratio between 2018 and 2022) which allows these targets to be achieved, it has not published a detailed roadmap by sector, instrument, region or country. Drawing up the French roadmap is complicated by the fact that it is difficult to establish a link between budgets approved and the ODA amounts ultimately accounted for (Chapter 5).

The increase in ODA has already been implemented since 2017, and the ODA/GNI ratio was due to reach 0.43% in 2017 (OECD, 2018a) and 0.44% in 2018 (MEAE, 2018a). Figure 3.2 illustrates the efforts that France will need to make to achieve its target in the coming years, and compares them to those recently made by Germany and the United Kingdom to achieve their ambitious ODA targets.

As the French Development Agency (AFD) is now in charge of the majority of French aid, it is vital to issue commitment authorisations in 2019 and 2020 at the latest so that the corresponding disbursements can reach the intended target (which is measured as disbursements) in 2022. Achieving the 2022 target will be difficult because it means that it will be necessary to start monitoring the corresponding projects very swiftly, in countries where the capacity to absorb assistance is weak. Speeding up disbursements will also entail a change of methodology, in particular shortening distribution channels and targeting beneficiaries directly. Increasing aid that is channelled through NGOs, humanitarian aid and local governments, plus greater use of revenue from the financial transaction tax (FTT) in favour of development, are all means of achieving the desired target.

Figure 3.2. Growth of French ODA compared with Germany and the United Kingdom

Note: Dotted line represents forecasts for France

Source: for the period 2007‑17, OECD (2018a), OECD-DAC statistics, www.oecd.org/dac/stats (accessed 27 February 2018); for French 2018‑22 data MEAE (2018a), « Comité interministériel de la coopération internationale et du développement (CICID) 8 février 2018 Relevé de conclusions », www.diplomatie.gouv.fr/IMG/pdf/releve_de_conclusions_du_comite_interministeriel_de_cooperation_internationale_et_du_developpement_-_08.02.2018_cle4ea6e2-2.pdf

In terms of geographical allocation, France recommitted to paying 0.15% of its GNI in ODA to least-developed countries as part of the Istanbul Declaration (United Nations, 2011). Yet in 2016, French ODA to least-developed countries was only 0.08% of GNI, i.e. well below target, and slightly below the average of the other members of the OECD Development Assistance Committee (DAC) (0.09%).2

France’s ODA reporting to the DAC has improved

Reporting of French ODA to the DAC has improved in recent years. Data for 2016 have been reported in full, although the quality of certain information (commitment dates, loan terms, aid type, activity descriptions and aid channels) could still be improved.

Bilateral ODA allocations

Peer review indicator: Aid is allocated according to the statement of intent and international commitments

In the review period, France’s priority countries were not among the main beneficiaries of its aid. It allocated a significant share of bilateral aid to economic infrastructure, imputed student costs and grants for higher education in France. Almost half its activities were carried out with a climate co-benefit. Moreover, its humanitarian aid, activities in fragile contexts, support for non‑government organisations (NGOs) and gender equality aid are still lower than its stated ambitions. In its partner countries, French aid is spread over more than three sectors, which is at odds with the objectives of general French co‑operation policy.

France does not provide sufficient aid for its priority countries

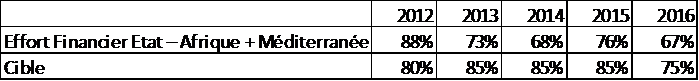

Over the review period, the geographical allocation of French bilateral aid did not reflect its priorities (aid for least-developed and priority countries). Neither has France achieved its regional objective in terms of financial effort3 for Africa and the Mediterranean since 2012 (MEAE, 2018b, and provisional 2016 data provided by the MEAE).4 Furthermore, that objective does not cover the entire loan component of ODA and does not distinguish between countries according to their wealth and means.5 In practice, the majority of French ODA to Africa and the Mediterranean was allocated to middle‑income countries: with Morocco, Côte d’Ivoire, Cameroon, Egypt and South Africa featuring among the top ten recipients of French aid in 2015‑16 (Table B.4).

At the same time, none of the 17 priority countries ranked among its top 10 beneficiaries in 2016, and only one ranked in the top 20. In 2016, only 14% of French bilateral ODA was allocated to the 17 priority countries. It is worth noting that in 2016 only 25% of bilateral ODA grants were allocated to those countries6 (OECD, 2018a). In that year least‑developed countries accounted for only 19% of allocable French bilateral aid, compared to 37% on average for the DAC. French ODA for least‑developed countries has decreased in volume over the review period, falling from USD 1.26 billion in 2012 to USD 1.05 billion in 2016 (Figure 3.3; Table B.3).

The considerable increase in ODA predicted by France for the next five years will enable it to significantly increase its actual commitment to the poorest countries, and especially its priority countries. France determines its priorities according to the added value that it can contribute: this is good practice. In February 2018, the CICID reaffirmed France’s 19 priority countries (section 2.1), (MEAE, 2018a). The Sahel is a priority region, due to its security situation, migratory flows and historical and linguistic links with France. The new doctrine of engagement in fragile situations will be put to the test in this region.

Figure 3.3. Gross bilateral ODA by income group, 2011-16

Source: OECD (2018a), OECD-DAC statistics, www.oecd.org/dac/stats (accessed 27 February 2018)

Bilateral ODA is too fragmented; too little goes to basic education, gender equality and NGOs

The 2014 LOP‑DSI lists France’s principal co‑operation action areas (Chapter 2). Although the share of aid allocated to education is relatively large (16% of bilateral commitments in 2015‑16), it is mostly earmarked for imputed student costs and scholarships for developing country students in French higher education (70% of commitments in the education sector), whereas a very small share (5%) has been allocated to basic education in developing countries themselves. The bilateral aid component earmarked for health is tiny (2%), but only because France uses the multilateral channel to support that sector (Section 3.3). The governance sector received 4% of French bilateral ODA. Aid for water distribution and sanitation rose from 6% to 10% of bilateral commitments between 2011‑12 and 2015‑16 (Annex B, Table B.5).

The economic infrastructure sector receives a large portion of French bilateral ODA. This is particularly evident for energy (14%) and transport (7%), involving AFD loans mainly in middle‑income countries, such as Morocco (Annex C). Agriculture receives 6% of bilateral aid. On the other hand, the low level of humanitarian aid (USD 153 million in 2016, or 1% of ODA, compared to an 11% average for the DAC) is inconsistent with French strategic objectives. In 2016, France committed USD 2 billion to fragile situations, in other words 27% of its bilateral aid. This is lower than the DAC average (33%) (Annex B, Table B.3). France is therefore devoting only modest amounts despite its renewed pledges to fragile contexts.

Country programmable aid represents 66.4% of total French ODA, which is higher than the DAC average (46.4%). In terms of cross‑cutting priorities, 45% of bilateral ODA commitments targeted climate change mitigation and/or adaptation objectives, while only 22% of commitments7 target gender equality (compared with an average of 40% for the DAC) (OECD, 2018b). The ratio of grants to loans, and the lack of emphasis on priority countries, explains the discrepancy between stated priorities and actual ODA flows. The only exception is climate change, the alleviation of which is indeed a priority sector for France’s allocations to middle‑income countries. Moreover, while France has doubled its assistance to and via NGOs since 2012, the level (3% of bilateral ODA) is still very low compared to the DAC average (15% of bilateral ODA) (OECD, 2018a).

The allocation of aid in the field largely reflects the demands of the country in question, and as a result, aid aligns to national priorities, reflecting partner country ownership. However, this can lead to aid being spread over too many sectors, which conflicts with France’s co‑operation policy objectives of choosing three priority sectors for each country (Chapter 2). During its field visits, the review team noted that, despite official priorities, France tended to be active in all sectors. This was particularly noticeable in Niger, but also to a lesser extent in Morocco (Annex C). This fragmentation can also complicate the channelling of aid and the identification of suitable technical expertise by embassies and local AFD agencies, which do not have the capability to lead projects in all fields.

Multilateral ODA allocations

Peer review indicator: The member uses the multilateral aid channel effectively

French multilateral ODA is targeted towards just a few agencies, through which it furthers its geographical and thematic priorities, with the exception of gender equality. In particular, France uses the multilateral channel to support its efforts in the health field. French contributions fund the core budgets of multilateral agencies, thereby strengthening the multilateral system.

French multilateral ODA targets just a few multilateral agencies and reflects its regional and thematic priorities

The share of multilateral aid in gross French ODA rose from 31% to 37% between 2012 and 2016, mainly due to a reduction in bilateral aid. The volume of multilateral aid rose slightly, and its distribution remained stable over the review period. France concentrates its assistance on a few priority multilateral agencies, which it uses to further its geographical and thematic priorities. The recipient agencies are the institutions of the European Union (USD 2.56 billion, or 57% of France’s multilateral ODA in 2016); the World Bank (10%); the Global Fund (8%); and the African Development Bank (4%) (Figure 3.4 and Annex B, Table B.2). In 2016, France reported contributions for the first time to the new Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, set up in 2014 by China, and which France joined in 2016 (Chapter 5, Box 5.1). These contributions amounted to USD 234 million, or 5% of French multilateral ODA (OECD, 2018a).

France hopes that its multilateral funding will complement its bilateral funding and is calling on multilateral banks to take greater account of climate issues in their financing decisions (Chapter 2). From a geographical perspective, France prioritises those institutions that are committed to the least‑developed countries, fragile states and sub‑Saharan Africa. This is certainly the case for the International Development Association of the World Bank, the African Development Bank, the Global Fund and, to a lesser extent, the European Union (OECD, 2018a). The vast majority of French contributions finance the core budget of multilateral agencies, thereby ensuring the financial sustainability and independence of the multilateral system (Chapter 2).

Figure 3.4. Distribution of French multilateral aid

Note: ADB: African Development Bank; AIIB: Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank

Source: OECD (2018a), OECD-DAC statistics, www.oecd.org/dac/stats (accessed 27 February 2018)

France relies very heavily on the multilateral channel to deliver its aid in the health sector: it is the second largest donor to the Global Fund since the creation of the fund, and contributed EUR 300‑350 million every year between 2012 and 2017. France also contributes to Unitaid (EUR 100 million in 2015, making it the largest donor); to the International Finance Facility for Immunisations (with a commitment of EUR 1.4 billion up until 2026); and to the Vaccine Alliance (GAVI), to which it is the fourth highest sovereign donor (MEAE, 2017). France also uses the multilateral channel and thematic funds (Global Environment Fund and Green Climate Fund) to complement its activities in connection with the environment and combatting climate change. In addition, France is now active in the educational field since President Macron announced a steep increase in France’s contribution to the Global Partnership for Education at the Financing Conference for the Global Partnership for Education, held in February 2018 in Dakar. That contribution will amount to EUR 200 million for the period 2018‑20 (MEAE, 2018a).

On the other hand, France has made less use of the multilateral channel for promoting its gender equality agenda, and the agencies interviewed by the review team did not refer to any systematic pressure from France in that respect. Moreover, France has made only modest contributions to United Nations Funds and Programmes. In recent years, its margin for manœuvre for increasing and adjusting its allocations has been limited, but it committed at the CICID meeting in February 2018 to increase its contributions to the United Nations, particularly in the humanitarian and food security fields. France would also like to continue to exert influence on the United Nations system in terms of environmental issues (Global Pact for the Environment) and the fight against climate change (Climate Convention).

Financing for development

Peer review indicator: The member promotes and catalyses development finance additional to ODA

France has successfully established some innovative development financing mechanisms, including the financial transaction tax, the solidarity levy on air tickets; the “1% water”, “1% waste” and “1% energy” facilities, and debt reduction and development contracts. Continued development of these mechanisms could help to promote their use by other donors and enable France to be a leading protagonist in this field. In addition, France has a broad range of catalysing instruments for supporting private‑sector development and reports a large proportion of its non‑ODA contributions to the DAC.

France has successfully developed innovative development financing mechanisms

In 2015, France adopted the Addis Ababa Action Agenda and the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. It also played a leading role in the Paris Agreement on climate at the 21st yearly session of the Conference of Parties (COP21), which it hosted. These three action programmes contain very serious commitments to development financing. They recognise the need to mobilise public internal resources, private funding and innovative financing mechanisms in addition to ODA in order to achieve sustainable development objectives in developing countries.

Moreover, France has successfully developed some innovative financing mechanisms: the financial transaction tax (FTT) and the solidarity levy on air tickets (TSBA) together brought in EUR 1 billion for ODA in 2017 and are set to do the same in 2018 (Box 3.1). However, a significant share of FTT revenue has been used for purposes other than development;8 furthermore, the fact that it is capped and substitutes for – rather than supplements – ODA budget credits in the past few years could harm both its credibility and potential imitation by other countries. Ways of increasing the rate of FTT and increasing its share of revenue assigned to development are currently under study (Coordination SUD, 2017a; National Assembly, 2017b). Their implementation could help France to achieve its ambitions for increasing its ODA volume in the coming years.

France has a broad range of instruments for private‑sector development in developing countries

Relying principally on the AFD Group, France has a broad range of instruments (loans, guarantee funds, equity capital investments and technical assistance) to assist private‑sector development in developing countries. Technical assistance can also be provided to support project development for infrastructure construction, intermediation with banks, microfinance, assistance with private‑sector regulation, and support for the proliferation of SMEs, as in Morocco and Niger, where such assistance is highly valued. In addition, France grants non‑sovereign loans (for example, to Morocco) to support certain projects that are thought to be sufficiently profitable. In 2016, these non-sovereign loans amounted to USD 958.4 million from AFD and USD 924.2 million from Proparco, a subsidiary of AFD.9 These loans are offered to private or public companies without the guarantee of the state (Annex C).

In middle‑income countries, France also uses loans to mobilise other forms of financial support, particularly from national resources. These are used for infrastructure, urban development and the environment and also in the productive sectors. For example, in Morocco they have been used in the fields of renewable energy, water and transport (Annex C). ODA loans go hand in hand with technical assistance and supplement contributions from other partners with major funding capabilities (such as the European Investment Bank, European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, KfW, World Bank, and the African Development Bank), as well as the state’s own resources.

Proparco also supports the private‑sector by way of loans and equity. It has significantly increased its activities in line with French priorities: its strategy for 2017‑21 is to double its 2015 annual commitment of EUR 1.05 billion to EUR 2 billion by 2020. It is also aiming to increase its equity capital investment from 10% to 25% of its activities in order to triple its impact on sustainable development in the areas of employment, climate, innovation, education, health and energy infrastructure (Proparco, 2017). In addition, Proparco wants to increase its activities in Africa and in fragile states. In order to realise that positive ambition, it will need to adjust its procedures, for example by reducing the barrier to entry for loans or by calling on local financial intermediaries.

France is also involved in broader initiatives for developing the private sector. For example, both France and Germany play a key role in the G20 Compact with Africa to promote private investment in Africa (particularly infrastructure). France is an influential supporter of the “cascade” concept, which seeks to create markets and increase private financing (World Bank/IMF, 2017). It is also involved in the future joint investment fund STOA between AFD and the Caisse des Dépôts et Consignations (Deposits and Consignments Fund, CDC), for investment in infrastructure, half of which (EUR 300 million over seven years) will be earmarked for Africa.10 Furthermore, France has taken steps to reduce the cost for migrants of remitting funds to their country of origin,11 funds which amounted to USD 12.5 billion in 201612, higher than France’s total ODA. It has drawn up a programme to provide financial backing for members of the diaspora when setting up businesses in their country of origin.13

France reports the majority of its non‑ODA contributions to the DAC

France reports its non‑ODA public‑sector contributions, notably Proparco loans, to the DAC. It also took part in the survey carried out by the OECD in 2016 into sums mobilised by the public sector to support the private sector, the results of which showed that it had mobilised USD 2.8 billion over the period 2012‑15 (OECD, 2018c). France has also started to include this information in its regular reports to the DAC, thereby complying with the committee’s directives.14 However, it has only partially reported to the DAC the equity investments made by Proparco, and no longer reports any of the publicly‑funded export credits (offered by Coface).15

Box 3.1. France at the forefront of innovative financing

At the instigation of France and Brazil, the solidarity levy on air tickets (TSBA) was adopted by five countries1 in September 2005 at the Paris Ministerial Conference on Innovative Financing for Development2. The revenue generated by that tax, which is earmarked solely for international development, has been around EUR 210 million per year since 2006.

The financial transaction tax (FTT) was introduced in France on 1 August 2012. The tax is levied on the share transactions of listed French companies with market capitalisation in excess of EUR 1 billion; the initial rate of the tax was 0.2%, raised to 0.3% in 2017.3 Half of the revenue generated by the FTT is earmarked for development, and the tax is not levied on intraday transactions.4 Revenue from the FTT allocated to development amounted to EUR 497 million in 2016 and EUR 798 million in 2017; the forecast for 2018 is similar to 2017.

Overall, these innovative funding mechanisms produced EUR 1 008 million per year for ODA in 2017 and 2018. The Solidarity Fund for Development was set up as a dedicated fund for revenue from the FTT and TSBA. For the first time, an annex to the Finance Law 2018 has set out how revenue from innovative development funding mechanisms is to be used. In 2017‑18, it is mostly to be earmarked for health (Global Fund, International Finance Facility for Immunisation and Unitaid); climate and environmental issues (Green Climate Fund, bilateral AFD projects, LDC Fund); and the Vulnerability Mitigation and Crisis Response Facility of AFD. France is the Permanent Secretary of the Leading Group on Innovative Financing for Development. At the CICID meeting in February 2017, France reiterated its support for extending the FTT to other EU countries.

France has also devised other innovative development funding mechanisms:

Since 2015, the “1% water”, “1% waste” and “1% energy” facilities have enabled French local authorities to finance appropriate projects in developing countries.

Debt reduction and development contracts (C2Ds), which refinance ODA credits in the form of grants and are then reassigned to financing poverty‑reduction projects and programmes, or to issuing “climate” bonds. Since 2001, France has signed 33 C2Ds with 18 countries; by the end of 2014, almost EUR 1.7 billion had already been re‑financed in the form of grants to recipient countries.

1. Brazil, Chile, France, Norway and the United Kingdom.

2. The levy applies to all tickets for flights departing from the participating country; in France, it amounts to EUR 1.13 to EUR 45.07 per ticket, depending on the flight type and travel class

3. It also includes two other mechanisms: a tax on cancelled orders in connection with high‑frequency trading and a tax on credit default swaps

4. In 2016, parliament had voted to extend the FTT to intraday trades as from 1 January 2018, but that provision was annulled by the new parliament in 2017 (Coordination SUD, 2017a).

Sources: AFD (2017), “Revue de la politique du contrat de desendettement et de développement (C2D)”, (in French), French Development Agency, Paris, www.afd.fr/fr/revue-de-la-politique-du-contrat-de-desendettement-et-de-developpement-c2d; MEAE (2018b), ), “Politique française en faveur du développement”, Document de politique transversale (in French), MEAE, Paris, www.performance-publique.budget.gouv.fr/sites/performance_publique/files/farandole/ressources/2018/pap/pdf/DPT/DPT2018_politique_developpement.pdf; MEAE (2017), “Mémorandum de la France sur ses politiques de coopération : Comité d'aide au développement, OCDE”, (in French) MEAE, Paris ; MEAE (2016), “Revue de la politique du contrat de désendettement et de développement” (in French), MEAE, Paris, www.tresor.economie.gouv.fr/Ressources/13827_revue-de-la-politique-du-contrat-de-desendettement-et-de-developpement (consulted 27 February 2018); Toustou, E. (2014), “Prendre les airs coûte plus cher”, L’Express, 3 April 2014 (in French), https://votreargent.lexpress.fr/consommation/prendre-les-airs-coute-plus-cher_1583837.html (consulted 13 March 2018).

References

AFD (2017), “Revue de la politique du contrat de desendettement et de developpment (C2D)”, (in French), French Development Agency, Paris, www.afd.fr/fr/revue-de-la-politique-du-contrat-de-desendettement-et-de-developpement-c2d.

Coordination SUD (2017a), “Premier test-clé du quniquennat pour la solidarité internationale” (in French), Coordination SUD, Paris, www.coordinationsud.org/wp-content/uploads/PLF-2018-Coordination-Sud-vf-web.pdf.

Coordination SUD (2017b), “Une revue alternative du bilan politique de développement et de solidarité internationale de la France entre 2013 et 2017 par la société civile” (in French), Coordination SUD, Paris, www.coordinationsud.org/document-ressource/revue-alternative-de-societe-civile-bilan-2013-2017-de-politiques-francaise-de-developpement-de-solidarite-internationale/

Lemmet, S. and P. Ducret (2017), “Pour une stratégie française de la finance verte” (in French), www.economie.gouv.fr/files/files/PDF/2017/rapport_finance_verte10122017.pdf.

Macron, E. (2017), “Initiative pour l'Europe - Discours d'Emmanuel Macron pour une Europe souveraine, unie, démocratique”, speech by the President of the Republic, 26 septembre 2017 (in French), www.elysee.fr/declarations/article/initiative-pour-l-europe-discours-d-emmanuel-macron-pour-une-europe-souveraine-unie-democratique/ (accessed 19 February 2018).

MEAE (2018a), “Comité interministériel de la coopération internationale et du développement (CICID) 8 février 2018. Relevé de conclusions” (in French), MEAE, Paris, www.diplomatie.gouv.fr/IMG/pdf/releve_de_conclusions_du_comite_interministeriel_de_cooperation_internationale_et_du_developpement_-_08.02.2018_cle4ea6e2-2.pdf.

MEAE (2018b), ), “Politique française en faveur du développement”, Document de politique transversale (in French), MEAE, Paris, www.performance-publique.budget.gouv.fr/sites/performance_publique/files/farandole/ressources/2018/pap/pdf/DPT/DPT2018_politique_developpement.pdf.

MEAE (2017), “Mémorandum de la France sur ses politiques de coopération : Comité d'aide au développement, OCDE”, (in French) MEAE, Paris.

MEAE (2016), “Revue de la politique du contrat de désendettement et de développement” (in French), MEAE, Paris, www.tresor.economie.gouv.fr/Ressources/13827_revue-de-la-politique-du-contrat-de-desendettement-et-de-developpement (accessed 27 February 2018).

National Assembly (2017a), “Aide publique au développement : projet de loi de finances pour 2018”, vol. 275/3 (in French), National Assembly, Paris, www.assemblee-nationale.fr/15/pdf/budget/plf2018/a0275-tIII.pdf.

National Assembly (2017b), “Rapport d'information déposé par la Commission des affaires étrangères en conclusion des travaux d’une mission d’information constituée le 27 avril 2016 sur sur les acteurs bilatéraux et multilatéraux de l’aide au développement” (in French), National Assembly, Paris, www.assemblee-nationale.fr/14/pdf/rap-info/i4524.pdf.

OECD (2018a), OECD/DAC statistics, www.oecd.org/dac/stats (accessed 27 February 2018).

OECD (2018b), “Aid in support of gender equality and women’s empowerment: donor charts”, OECD, Paris, http://www.oecd.org/development/financing-sustainable-development/development-finance-topics/Aid-to-gender-equality-donor-charts-2018.pdf.

OECD (2018c), “Amounts mobilised from the private sector for development”, Development Finance Statistics (dataset), OECD, Paris, www.oecd.org/dac/stats/mobilisation.htm (accessed 27 February 2018).

OECD (2014), OECD Development Co-operation Peer Reviews: France 2013, OECD Development Co‑operation Peer Reviews, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264196193-en.Proparco (2017), “Stratégie 2017-2021 Proparco”, press release (in French), January 2017, Proparco, Paris, www.proparco.fr/sites/proparco/files/2017-12/Dossier%20de%20presse%20Strat%C3%A9gie%202017-2020%20de%20Proparco.pdf.

Senate (2014), “Agence française de développement : quelles ambitions pour 2014-2016 ?” (in French), Senate, Paris, www.senat.fr/rap/r13-766/r13-7660.html (accessed 12 March 2018).

Toustou, E. (2014), “Prendre les airs coûte plus cher”, The Express, 3 April 2014 (in French), https://votreargent.lexpress.fr/consommation/prendre-les-airs-coute-plus-cher_1583837.html (accessed 13 March 2018).

United Nations (2011), “Report of the fourth United Nations conference on the least developed countries”, United Nations, New York, http://unohrlls.org/UserFiles/File/A-CONF_219-7%20report%20of%20the%20conference.pdf.

World Bank/IMF (2017), “Forward look: a vision for the World Bank Group in 2030 – progress and challenges”, The World Bank, Washington DC, http://siteresources.worldbank.org/DEVCOMMINT/Documentation/23745169/DC2017-0002.pdf.

Notes

← 1. By their very nature, France’s bilateral loans mainly benefit middle‑income countries, but these are not its priority countries. Moreover, a large proportion of French grants are earmarked for tuition fees and grants (11% of gross bilateral ODA in 2016), and for refugee reception in France (6%) (Annex B, Table B.2). Furthermore, France has limited control over the allocations of its multilateral aid to its priorities.

← 2. These figures include imputed bilateral and multilateral inputs (Annex B, Table B.7).

← 3. ODA subsidies plus cost to the state of ODA loans by AFD and concessional loans by the Treasury plus cost of debt cancellations granted in the context of the Paris Club (MEAE, 2018b, page 16).

← 4. The State’s financial outlay and targets were as follows:

← 5. A Senate report on the AFD contract of objectives and means 2014‑2016 also draws attention to the problem in terms of measuring aid to priority countries (Senate, 2014).

← 6. Data from 2016 as a proportion of gross bilateral ODA, excluding unspecified bilateral aid.

← 7. This percentage is calculated solely on activities screened against the gender marker (82% of France’s aid activities); this differs from the percentage (19%) given in Table B.5 (Annex B), which is calculated on the basis of total allocable bilateral aid.

← 8. Although initially the FTT was not wholly intended to finance development, numerous advocates – including President Macron, in his speech of 26 September 2017 at the Sorbonne (Macron, 2017) – have called for a larger proportion – if not all of it – to be used for development.

← 9. Almost all non-sovereign loans extended by AFD are counted as ODA, whereas those provided by Proparco are “other official flows”.

← 10. The STOA fund is intended to promote investment that is compatible with the Paris Agreement and to have a leveraging effect on private funds (Lemmet and Ducret, 2017).

← 11. Including, for example, by setting up a website for comparing the prices quoted by money transfer services (www.envoidargent.fr).

← 12. Voir le site de la Banque mondiale : www.worldbank.org/en/topic/migrationremittancesdiasporaissues/brief/migration-remittances-data

← 13. The Franco‑German programme “MEETAfrica” – European mobilisation for entrepreneurship in Africa (http://meetafrica.fr).

← 14. France has played a leading role in this notification, especially in the context of the Change Expert Group and private financing mobilised in favour of climate and development.

← 15. France does report export credits that benefit from public support from Bpi-France international, but only reports to the Export Credit Group.