This chapter evaluates the main demographic factors underpinning population ageing in Korea. It looks at some of the main impacts population ageing is likely to have on Korea’s labour market and on social cohesion and, by extension, on the broader economy.

Working Better with Age: Korea

Chapter 1. The challenge of population ageing in Korea

Abstract

The statistical data for Israel are supplied by and under the responsibility of the relevant Israeli authorities. The use of such data by the OECD is without prejudice to the status of the Golan Heights, East Jerusalem and Israeli settlements in the West Bank under the terms of international law.

Korea is ageing more rapidly than any other OECD country

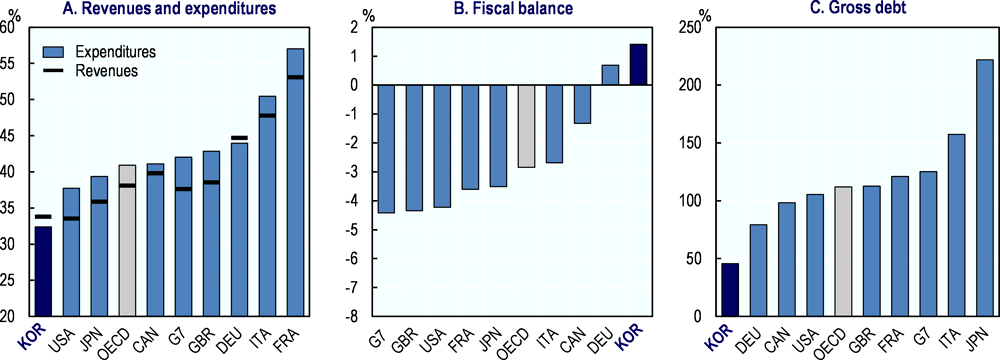

The population of Korea is ageing more rapidly than that of any other OECD country. This is expected to place an unprecedented economic burden on the working-age population and create a challenge for policy makers and fiscal institutions. The structure of Korea’s population has transformed rapidly over the past generation or two and is projected to change even more within the forthcoming two generations (Figure 1.1). While the numbers of younger Koreans have contracted significantly and are due to contract further in the coming decades, the numbers of older people have multiplied.

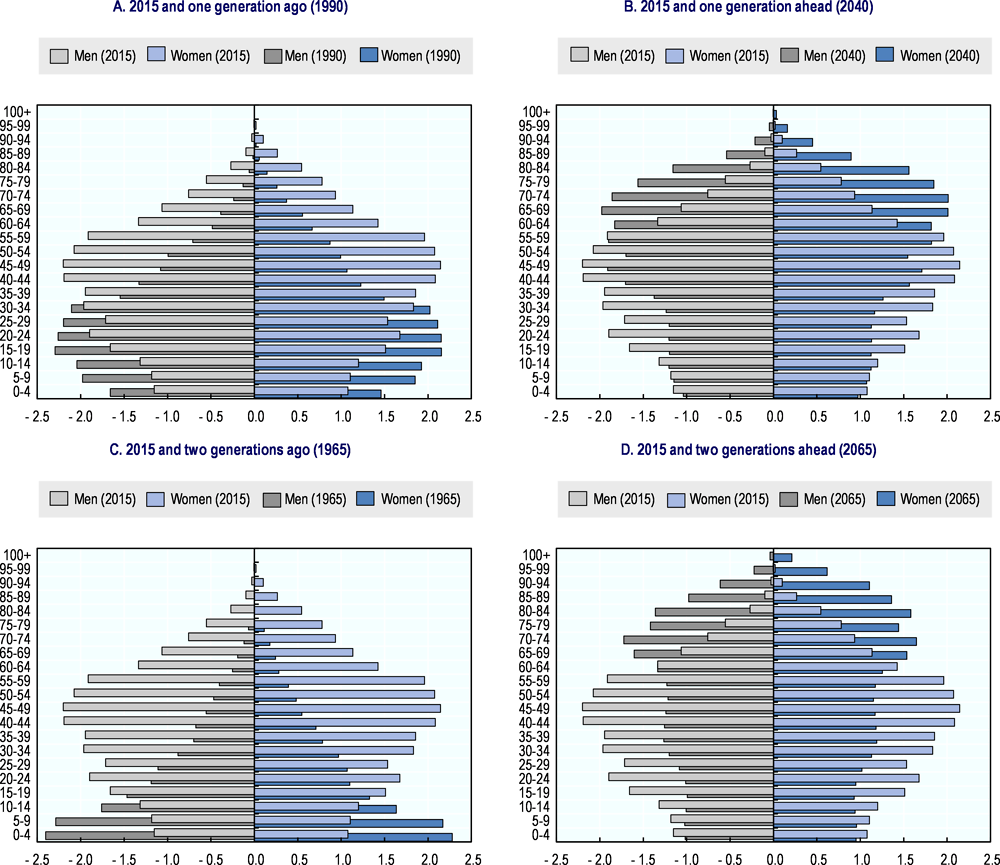

Such transformational demographic change has already caused individual segments of Korea’s working-age population to shrink in absolute terms (Figure 1.2, Panel A). The absolute number of children and adolescents in Korea (aged 0-14) reached a peak of 13.6 million in 1972 and has since declined to roughly half of that number. The number of young working-age adults (aged 15-29) peaked in 1989 at 13.2 million and has since fallen to less than 10 million. The number of prime working-age adults (aged 30-49) has also reached a peak at 17.2 million in 2006 and is now declining. According to the latest projections from the United Nations (UN-DESA), the older working-age population in Korea (aged 50-64) is forecasted to peak in 2024 while the number of those aged 65 and above will continue to expand until 2051 (Figure 1.2, Panel B).

The scale of demographic change is forecasted to make Korea’s population the oldest among OECD countries in the 2050s. The median age has increased from less than 20 years before the mid-1970s to around 41 years today – just above the OECD average – and is projected to increase to nearly 55 years before stabilising at 50-55 years thereafter. This would place Korea’s median age above the age of all other OECD countries.

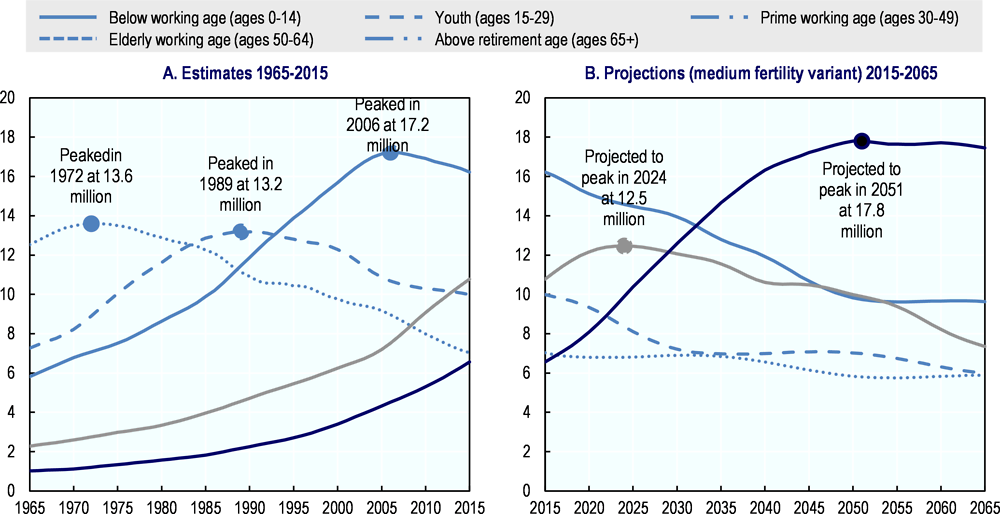

Demographic developments taking place in Korea will also alter the balance in society between the working-age and elderly populations. A much higher proportion of retirees for every working individual is likely to place strain on the fiscal institutions and on the delivery of public services. Korea currently has 177 residents aged 65 and above for every 1 000 persons of working age. This ratio – known as the old-age dependency ratio – was considerably lower than the OECD average of 246 in 2015. The figure for Korea, however, is projected to quadruple in the coming decades, exceeding the OECD average by around the year 2025 and peaking at a projected 760 by around 2065 – the highest ratio of any OECD country – according to the latest UN projections (Figure 1.3, Panel B). This represents a sharp contrast to most of the 1980s, when Korea’s dependency ratio was around 65-70 and thus one of the lowest in the OECD (Figure 1.3, Panel A).

Figure 1.1. The structure of Korea’s population is changing significantly

Note: One “generation” stands for a period of 25 years. Projections are based on the medium fertility variant. Estimates for age groups 80 and above in 1965 are missing.

Source: United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division (2017) World Population Prospects: The 2017 Revision.

Figure 1.2. Korea’s youth and working-age population is already declining in absolute terms

Note: Projections are based on the medium fertility variant.

Source: United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division (2017) World Population Prospects: The 2017 Revision.

Figure 1.3. Korea had the lowest dependency ratio of any OECD country during the 1970s and 1980s but is projected to have the highest by the 2060s

Note: Projections are based on the medium fertility variant.

Source: United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division (2017) World Population Prospects: The 2017 Revision.

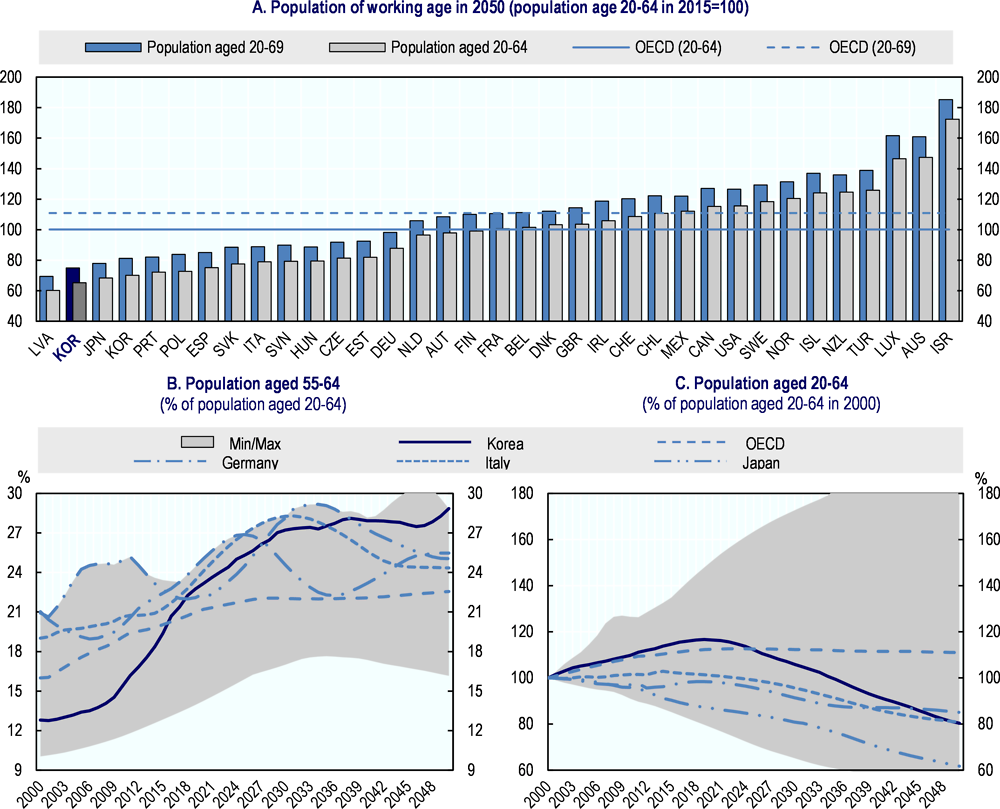

The workforce itself is also ageing fast. Korea’s older workers will soon play a major role in their country’s economic performance. Workers aged 55-64 years are projected to make up 28.6% of Korea’s 20-64 year-olds by 2050 – the highest proportion among all OECD countries (Figure 1.4, Panel B). Korea’s potential labour force, meanwhile, is projected to shrink dramatically by 2050, losing 30% of its absolute number in 2015 – second only to Japan among OECD countries (Figure 1.4, Panel C).1 In many OECD countries, including Japan and Korea but also many countries in the south and east of Europe, the number of people in the age group 65-69 – assuming people will work five years longer on average – will not be enough to compensate the potential rapid decline of the labour force (Figure 1.4, Panel A).

Population ageing might have consequences for economic performance

OECD countries’ diverse experiences show that population ageing could, but need not, lead to worse economic outcomes. In Germany, for example, the working-age population has steadily declined in absolute terms over the past two decades, substantially increasing the financial burden on the workforce although Germany has managed to maintain a strong social model – though reformed under the “Hartz Reforms” of the early-2000s – and to maintain robust economic performance. Italy’s experience, by contrast, has been somewhat gloomier: despite a more favourable demographic context, Italy has faced a prolonged period of economic stagnation, low productivity growth and rising public debt; maybe because labour market reforms have been postponed for too long, until the Jobs Act in 2012 and 2014.

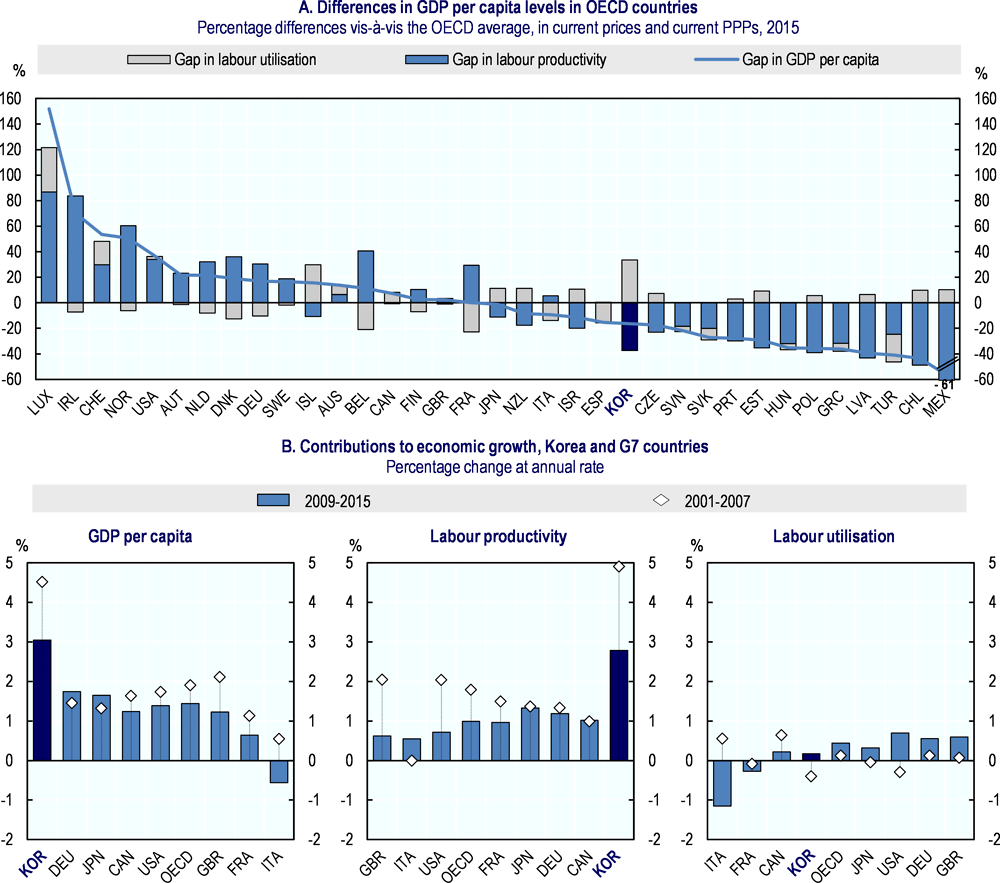

The pace and extent of Korea’s forthcoming demographic changes will likely have important consequences for economic performance given that labour resource utilisation is a key pillar of the Korean economy (Figure 1.5, Panel A). Labour productivity in Korea lags behind that of many other OECD countries. Korea’s below-average level of GDP per capita reflects a productivity gap not fully compensated by its comparative advantage in terms of labour utilisation. While the number of hours worked per capita in Korea was 36% higher than the OECD average (and the highest among all OECD countries), labour productivity – measured as GDP per hour worked – was 37% lower than the OECD average (the fifth lowest after Mexico, Chile, Latvia and Poland). Rapid population ageing in Korea will gradually erode its comparative advantage in terms of labour inputs, even alongside higher labour force participation rates. Policies to support productivity growth are therefore crucial for Korea to sustain the trend of rising living standards observed in previous decades.

Figure 1.4. The potential labour force will shrink fast in Korea in the next 30 years

Note: Data in Panel A show the extent to which the decline in the population age 20-64 could be compensated by a shift in the age span of the working population to also include the age group 65-69 (which roughly corresponds to an increase in the retirement age by five years).

Source: OECD Historical population data and projections (1950-2050).

On a more positive note, it is noteworthy that productivity gains remain an important engine of economic growth in Korea (Figure 1.5, Panel B). Labour productivity rose at an annual rate of 3% over 2009-15 – three times the OECD average over the same period.

While the global economic crisis substantially slowed down productivity growth in many OECD countries, demographic pressures could potentially make things worse for Korea, ceteris paribus. Nevertheless, there is room for improvement. First, Korea’s absolute gap in productivity with more advanced countries implies that there remains important untapped potential for productivity gains that the government is currently pursuing through a wide range of reforms (see OECD, 2016). Second, Korea’s population is becoming rapidly more highly educated (Figure 1.6), which is a key enabling factor for investment in innovation and productivity gains.

Figure 1.5. Economic performance, labour utilisation and labour productivity

Note: Labour utilisation is measured by the number of hours worked per capita; labour productivity refers to GDP per hour worked.

Source: OECD (2017), OECD Compendium of Productivity Indicators.

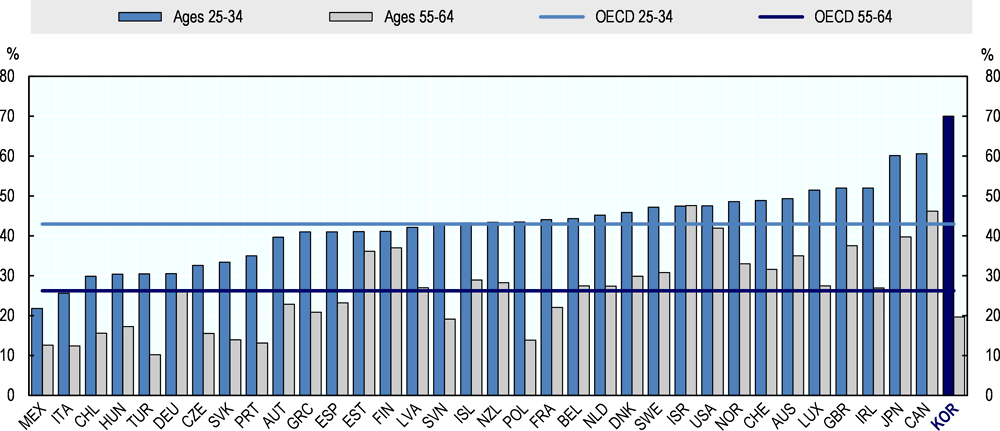

While only 20% of Koreans aged 55-64 had a tertiary-level qualification in 2016 (compared with 26% on average in OECD countries), a full 70% of those aged 25-34 did – the highest share for that age-group of any other OECD country and well above the OECD average of 43%. The magnitude of this difference in educational attainment between younger and older cohorts is a unique feature of the Korean workforce. Provided that available skills can adequately meet businesses’ needs in the coming decades, expanding tertiary education can be a major source of productivity gains.

Figure 1.6. Educational attainment has drastically improved for young Koreans

Note: Data for Chile and Ireland refer to 2015.

Source: OECD Dataset on Educational Attainment and Labour Force Status, http://stats.oecd.org//Index.aspx?QueryId=79284.

Policies for addressing population ageing should follow a broad perspective covering both short- and longer-term issues. Korea could have the best qualified cohort of older workers in the OECD within one generation if young cohorts are provided with adequate opportunities to upgrade their skills and learn new ones throughout their working lives.

Population ageing could also threaten social cohesion

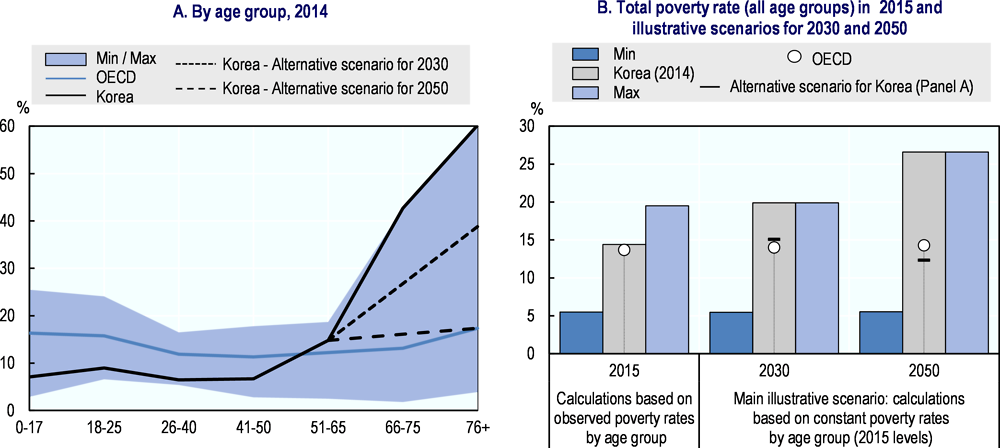

In 2014, one in every seven Koreans lived in households with a disposable income below 50% of the median – a proportion similar to the OECD average (Figure 1.7, Panel A). But the risk of poverty is unevenly distributed across age in Korea, much more so than in other OECD countries: while poverty rates for young and prime‑age Koreans are nearly half the OECD average, they are significantly higher for those in their 50s and above. At almost 15% in 2014, the poverty rate for Koreans aged 51-65 was more than double that of their counterparts aged 41-50. Furthermore, just over two fifths of Koreans aged 66-74 and three fifths of those aged 75 and above were poor – both groups more than three times the relevant OECD average. In part, these outcomes reflect the fact that Korea’s pension system is not yet fully mature. More generally, however, these outcomes point towards a need for stronger social protection measures that older people can access.

For Korea’s rapidly ageing population, tackling old-age poverty – including among older workers – is essential to maintaining social cohesion. Assuming that the level and age composition of poverty rates would remain unchanged, Korea could face the highest overall poverty rate among OECD countries by 2030 (Figure 1.7, Panel B). While the expected change in the population structure by age – all else being equal – would have almost no impact on poverty among other OECD countries, on average, the incidence of poverty in Korea could increase to 20% of the total population by 2030 and exceed 25% by 2050. Ameliorating this would require bringing the poverty risk faced by Koreans aged 65 and above in line with the OECD average. While these figures are merely illustrative (and must not be regarded as projections), they demonstrate the enormous pressure population ageing is putting on social protection expenditure in Korea.

Figure 1.7. The likelihood to live in a low-income household is very high for older Koreans

Note: For the Min, Max and OECD average, data refer to 2015, except for Australia, Hungary, Iceland and New Zealand (2014) and Japan (2012).

Source: OECD Database on Income Distribution and Poverty, http://stats.oecd.org//Index.aspx?QueryId=66596.

Korea has a number of strengths and opportunities to help it meet the challenge of population ageing. First, higher educational attainment among future cohorts of elderly workers in Korea should help them to sort into more productive and rewarding jobs. Second, more robust old-age pension rights will enable future cohorts of retirees in Korea a higher standard of living. Finally, Korea also has the fiscal space to comprehensively strengthen its social protection institutions while ensuring that public social spending remains cost-effective, employment-friendly and efficiently financed (OECD, 2016).

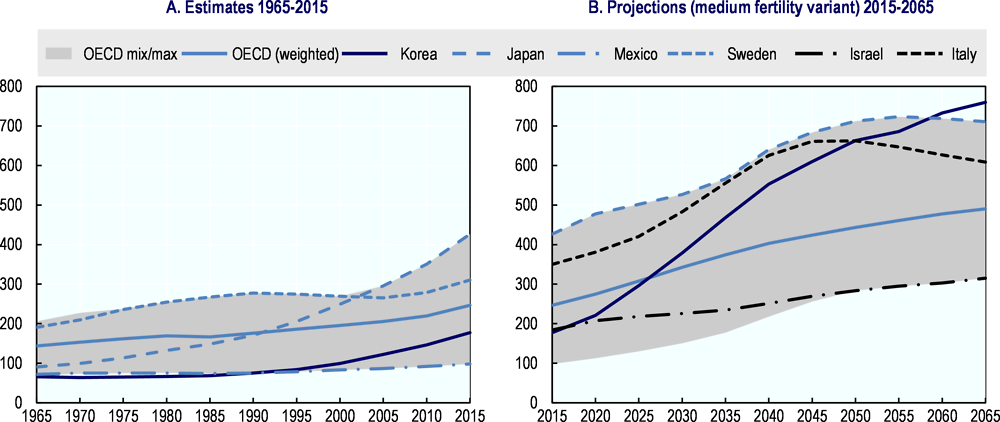

Meeting these conditions could enable Korea’s government to increase both public expenditures and revenues to levels closer to the OECD average without endangering growth prospects (Figure 1.8). Stable growth is further ensured by Korea’s strong fiscal position and low government debt. Korea had a budget surplus of 1.4% of GDP in 2015, as compared with a budget deficit averaging 2.8% of GDP across all OECD countries. Korea’s general government debt was equal to 45.8% of GDP in 2014 – less than half of the OECD average.

Figure 1.8. Korea’s sound public finances provide room for social protection reforms

Conclusion

Korea’s population is ageing faster than that of any other OECD country. While many of the key trends are already being felt, the biggest change will occur within the next three or four decades. The number of Koreans aged 65 and above per 1 000 of the working-age population is forecast to quadruple between 2015 and the late-2050s – the highest old-age dependency ratio of any OECD country. Over the same period, the median age of the Korean population is projected to increase from its current 41 years – just one year higher than the OECD average – to nearly 54 – also the highest of any OECD country. Only five decades ago, Korea’s median age was 18, one of the lowest in the OECD.

Demographic change on such a significant scale will require concerted policy action on several fronts to safeguard Korea’s economy and ensure social cohesion. The following chapters focus, in particular, on what precisely can be done to improve outcomes for Korea’s ageing workforce. Three key themes include tackling old-age poverty through more rewarding work; improving opportunities for older workers to find and retain quality work; and boosting individuals’ employability throughout their working lives.

Note

← 1. Among the G7 economies, only Germany, Japan, and (to a lesser extent) Italy are facing comparable demographic challenges and declining working-age populations. In Germany, the working-age population started to decrease in the mid-1990s (shrinking by 4.1% between 1996 and 2015). In Japan, this happened slightly later but at a higher pace (down 10.4% by 2015 from a peak in 1998). In Italy, the working-age population has continued to grow over the past two decades but at a very low rate. These three countries have experience with population ageing, as also witnessed by their old-age dependency ratios which, at 35% or above in 2015, were high by OECD standards – much higher than Korea’s current ratio (see Figure 1.1).