Maintaining the employability of workers throughout their working life is essential to ensure they can stay longer in the core labour market and hold decent jobs until they retire. For Korea, the challenge is threefold. First, as many workers have to start a second career after retiring from their main job, employment services and active labour market policies have an important role to play in helping workers make successful employment transitions. Second, in the medium term building an effective system of continuous vocational training is critical to ensure workers can use and upgrade their competencies and skills throughout their working life, to facilitate ending the practice of mandatory early retirement. Third, efforts to improve working conditions must continue to make working longer with full work capacity possible for older workers.

Working Better with Age: Korea

Chapter 3. Improving the employability and working conditions of older workers in Korea

Abstract

The statistical data for Israel are supplied by and under the responsibility of the relevant Israeli authorities. The use of such data by the OECD is without prejudice to the status of the Golan Heights, East Jerusalem and Israeli settlements in the West Bank under the terms of international law.

Maintaining and strengthening employability throughout the working life

Job retention rates of Korean workers aged 50 and over are low for a number of reasons which include work and retirement practices discussed in other chapters. Older workers are much less educated than their younger counterparts; this contributes to driving them out of quality career jobs. However, it is not workers’ educational attainment only that matters. Providing good opportunities for workers to upgrade their skills and learn new ones throughout their working lives is critical for fostering longer careers in rewarding jobs. In Korea, this is even more important as rapid economic transformation increases the risk of skill obsolescence, in a context where those workers lacking adequate skills are put at a particular disadvantage due to excessive labour market duality.

Many older workers in Korea have been left behind in the technology race

Jobs increasingly involve sophisticated tasks, require analysing and communicating information, and technology pervades all aspects of life. Hence, poor proficiency in information-processing skills not only restrains employment opportunities but also limits access to many services. More than ever, lifelong learning is of key importance, for all workers in all kinds of jobs. Workers in low-technology sectors and those performing low‑skilled tasks must learn to be adaptable, because they are at higher risk of losing their job, as routine tasks are increasingly performed by machines, and companies may relocate to countries with lower labour costs. In high-technology sectors, workers need to update their competencies and keep pace with rapidly changing techniques.

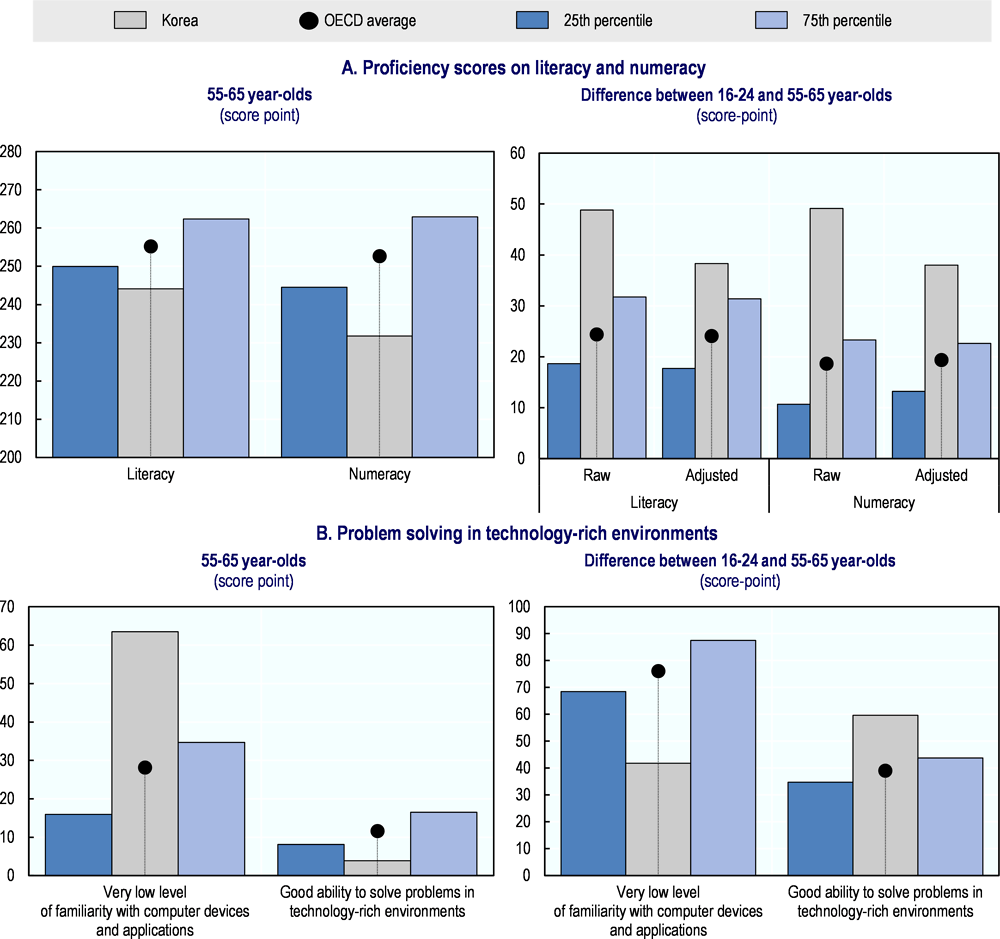

Results from the OECD Survey of Adult Skills (PIAAC) suggest that older workers in Korea are not well equipped to deal with skill requirements brought about by technological progress and globalisation. PIAAC provides insights into the availability of skills in 22 OECD countries, by measuring proficiency in several information‑processing skills, namely: literacy, numeracy and problem-solving in technology-rich environments (OECD, 2013a). The survey provides two pieces of information on the capacity of adults to manage information in technology-rich environments. One is the proportion of adults having sufficient familiarity with computers to perform information‑processing tasks. The other one is the proficiency of adults with at least some ICT skills in solving the types of problems commonly encountered in their roles as workers, citizens and consumers in a technology‑rich world. In all countries, skills proficiency reaches its highest levels during young adulthood and then declines with age. In Korea, this decline tends to be more pronounced than elsewhere (Figure 3.1); Korean 55-65 year-olds display low proficiency levels in all skills areas, compared to both their counterparts in other OECD countries and younger adults in their own country:

Korea displays the fourth-lowest score on literacy among 55-65 year‑olds and the third-lowest score on numeracy. Nearly two in three 55‑65 year-olds in Korea have no experience with the use of computers or a very low level of familiarity with computer devices and applications – more than twice the OECD average and the highest share among all countries. Conversely, only 4% of older people have a good ability to use computers and solve problems that may arise in their everyday lives, compared to an OECD average of close to 12%.

In Korea, the generation gap in proficiency is nearly twice as large as the OECD average, in all skill areas, due to 16-24 year‑olds scoring high and 55-65 year-olds scoring low by international standards. Accounting for educational attainment and socio‑economic background, the disadvantage among older adults in literacy and numeracy proficiency decreases substantially (by 20%). The adjusted generation gap, however, remains large: in literacy, it is 60% above the average across participating countries, and in numeracy, still double the cross-country average.

Figure 3.1. Korea’s older workers have much poorer skills than their younger counterparts or older workers in other OECD countries

Note: Very low level of familiarity with computer devices and applications: no prior computer experience or failed the ICT core test. Good ability to solve problems in technology-rich environments: proficiency score at level 2 or 3 on problem solving in technology-rich environments. For literacy and numeracy scores, adjusted differences are based on a regression model and take account of differences associated with the following variables: gender, education, immigration and language background, socio-economic background, and type of occupation. OECD is an unweighted average of the 22 countries in PIAAC Round 1.

Source: OECD (2013), OECD Skills Outlook 2013: First Results from the Survey of Adult Skills, OECD Publishing, Paris. Tables A3.2 and A3.3

Lower proficiency in foundation skills does not necessarily translate into greater risk of labour market disadvantage since older workers have acquired other skills through longer work experience which are valuable and that younger workers may not hold. However, their job-specific skills may put them at risk of exclusion from the core labour market if they lose their job. In particular, older jobseekers who lack basic skills to use computer devices and applications are likely to encounter strong difficulties in finding a job of high quality all the more so as many of them are in this situation in Korea.1

Moreover, the generation gap in both foundation and ICT skills is particularly large, which raises more general concerns about the employability of Korean older workers. For a significant part this skill gap is due to Korea’s rapid economic growth, which was accompanied by impressive investments in initial education. But it also suggests that lifelong learning policies have not adapted to the rapid transformation of Korea’s economy and society.

Boosting participation in vocational education and training

There is now compelling evidence that the benefits from continuous vocational training can be substantial, in terms of earnings and employment security (OECD, 2013a; OECD, 2006). Empirical studies suggest that overall wage returns to job-related training are relatively high, at 3% or more for one week of training in many cases (Leuven and Oosterbeek, 2008; Brunello et al. 2012; Picchio and van Ours, 2013). It can be safely argued that job-related training can have a significant impact on the income of older workers (beyond that on wages) if it allows them to delay their retirement or stay longer in their main job. Picchio and van Ours (2013), for example, found that firm-provided training significantly improves future employment prospects, in general but also for older workers: employees aged 50-64 are 4.2 percentage points more likely to retain employment if they have received training on the job in the previous year. This finding implies that continued training opportunities are essential to maintain the employability of workers throughout their working life.

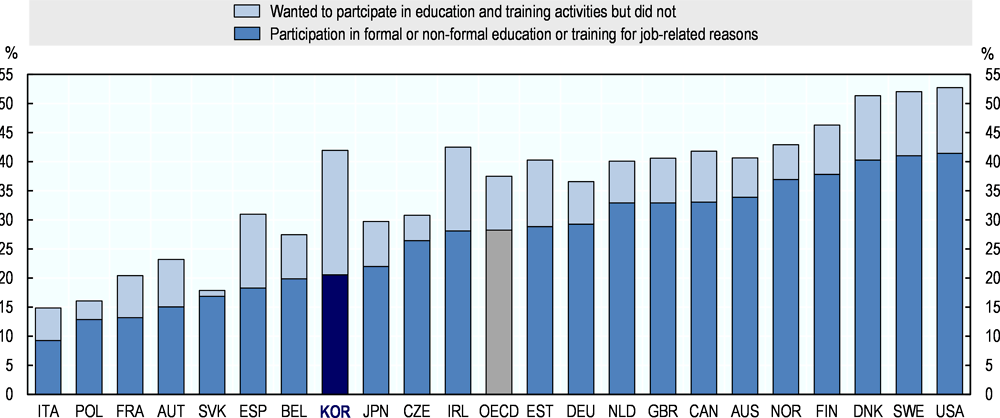

In Korea, only 20% of workers aged 55-64 have received work-related training during the 12 months prior to the OECD Survey of Adult Skills. This participation rate is relatively low compared with an OECD average of 28% and well below the rates of around 35-40% observed in countries such as Denmark, Finland, Norway, Sweden and the United States where vocational education and training (VET) is most widespread (Figure 3.2).

PIAAC provides additional information on unmet demand for training (workers who wanted to participate in training but did not). The willingness to learn among older workers is very high in Korea. Slightly more than one in five persons aged 55-64 report unmet demands for training, more than twice the OECD average for this age group (again, Figure 3.2). If all demand was met, Korea would rank among the best-performing countries with respect to education and training for older workers. This suggests older workers in Korea face strong obstacles to access training.

Figure 3.2. Many older workers in Korea want to participate in education or training but fail to do so

Note: OECD is a weighted average of the countries in the chart. Data for the United Kingdom refer to England and Northern Ireland, data for Belgium to Flanders.

Source: OECD Survey of Adult Skills (PIAAC), 2012, http://www.oecd.org/skills/piaac/.

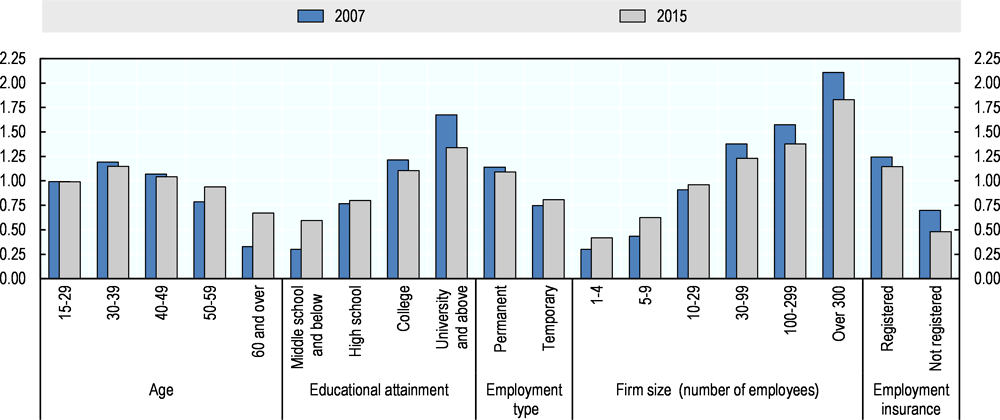

In virtually all OECD countries, VET is unequally distributed across workforce groups, with women, older workers, low-skilled workers and those in small firms and temporary jobs receiving the least training (OECD 2013; OECD 2006). While employer-sponsored VET is the main channel through which incumbent workers are upgrading their skills in Korea (see Box 3.1), firms’ incentives to invest in human capital are low for middle‑aged and older workers due to the widespread practice of mandatory early retirement at a relatively young age. Inequalities in access to training have been reduced in recent years, but more should be done. Workers aged 60 and over are still less likely to participate in VET, just as workers with less than middle-school education, workers in firms with 5‑9 employees and those not registered to Employment Insurance (Figure 3.4). Workers in firms with less than five employees are least likely to participate in VET among all groups of workers; this group makes up 28% of total employment in Korea.

Box 3.1. Vocational education and training in Korea

MOEL is the main body in charge of vocational education and training (VET), most of which is financed by the Employment Insurance (EI) fund. The EI system is also the main funding source for active labour market programmes, maternity and childcare leave benefits, as well as unemployment benefits. EI was introduced in 1995 and has gradually been expanded over time to cover most Korean employees, at least in theory; effectively, one in four salaried workers are not EI insured, most of them working in micro businesses (OECD, 2018a). However, there is a growing reliance on central funding, particularly for job‑search counselling and training for the unemployed, so that workers who are not eligible for EI can also receive support.

As part of the EI system, training is funded by a levy-grant scheme. All firms have to contribute to the EI fund, irrespective of whether their employees undertake training activities. Contribution rates vary from 0.25% to 0.85% of the total taxable wage bill depending on firm size, the lowest rate being applied to firms with fewer than 150 workers while the highest rate applies to firms employing 1 000 or more workers. There are two broad categories of subsidy schemes, depending on whether VET is initiated by an individual worker (employed or unemployed) or by an employer. In both cases, the subsidy amount does not necessarily cover VET expenditure completely, the co-financing element aiming at promoting rational and effective investments into VET. Applicants (individual workers or employers) can find all necessary information about VET courses and providers on a public internet portal (HRD-Net), including curricula, time schedule, available financial supports and eligibility criteria, as well as the assessment of various courses and providers. These assessments, required by the Framework Act on Employment Policy, are conducted on a regular basis by specific agencies under the umbrella of MOEL, with a strong focus on programme relevance to the labour market.

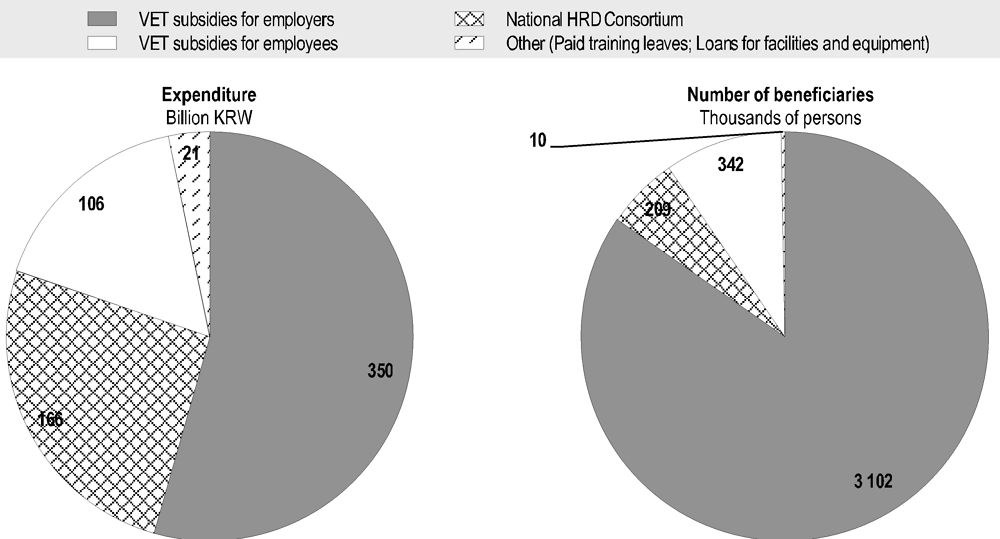

In practice, employer-provided VET is the main channel through which incumbent workers upgrade and develop their skills (Figure 3.3). Employers who provide VET to their employees can receive a subsidy amount of up to 100% of their EI contributions for large companies and up to 240% for SMEs (fewer than 300 workers), conditional on the approval of their training programme (its content, methods and number of hours per worker) by MOEL. They can implement the programme themselves or entrust the task to a private provider accredited by MOEL. SMEs are entitled to additional support to help them improve their organisational capabilities to train their employees. This includes public subsidies for overhead costs and consulting fees for the development of learning activities and on-the-job training. As part of the policy efforts to promote skills development for employees in SMEs, increasing attention is also being paid to collective training provision between large firms and SMEs. Under the National Human Resources Development Consortium (the CHAMP programme, introduced in 2001), large firms, business associations or universities are encouraged through public subsidies to set up a consortium with SMEs in order to share their training facilities and equipment, as well as their experience and knowhow. In 2014, 180 organisations were operating a training consortium under the CHAMP programme, which benefited more than 200 000 SME employees and accounted for 25% of total government expenditure on VET for incumbent workers.

Figure 3.3. Main categories of VET programmes for employees, 2014

For the unemployed and those workers who are not provided with adequate training opportunities by their employer, a system of Individual Training Accounts (ITA) has been implemented in 2010 (after a pilot phase launched in 2008). This scheme provides financial support in the form of vouchers for individual employees willing to undertake training on their own initiative (“My Work Learning Card System for Workers”) and to jobseekers (“My Work Learning Card System for Jobseekers”). All jobseekers can apply, but only incumbent workers aged 40 and over, SME employees, and non-regular workers (as well as self‑employed with employment insurance on a voluntary basis) are eligible. The training card is issued by the Public Employment Service, after a screening process aimed at evaluating the applicant’s training needs and aspirations. Card holders can select any courses within the list of programmes approved by MOEL, up to an amount of KRW two millions over one year (three million for jobseekers with low income). Information on the employment rate of each course and training provider is provided on the HRD-Net website so that potential trainees can see which courses are most effective. They should complete at least 80% of the programme in order to receive the grant and they have to pay 30-50% of the training costs out of their pocket, depending on whether the selected courses are closely related to work activities. Jobseekers who find a job can get a refund, and those from low-income households are exempted from the upfront payment. Since the introduction of ITAs in 2010, the screening process and the conditions for receiving training grants have been strengthened in order to increase their effectiveness in bringing people back into work.

Source: OECD (2014), Skills beyond School: Synthesis Report, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264214682-en.

Figure 3.4. Inequalities in access to training are considerable in Korea

Supports for and obstacles against the take-up of training

Additional financial supports are provided to vulnerable groups in order to enhance their training opportunities and curb inequalities (see Box 3.1). Workers aged 40 and over, non‑regular workers and those employed in SMEs who want to undertake VET on their own initiative can apply to a voucher programme in order to buy training courses approved by MOEL. In addition, the subsidy scheme for firm-sponsored VET is favourable to SMEs, which are also entitled to specific supports aimed at improving their organisational capabilities to train their employees. However, this various financial supports could be more effective if a centralised body with expertise in VET and adequate equipment was in charge of organising VET programmes for SMEs. Because they often lack experience and training facilities, it remains difficult for them to provide sufficient VET opportunities for their workforce.

The National Human Resources Development Consortium (CHAMP programme) addresses a number of organisational and technical constraints faced by SMEs, as it provides financial incentives for large companies, business associations or universities to set up a consortium and to share their know-how, equipment and training facilities with SMEs through this consortium. Based on a win-win approach, this programme has expanded remarkably over time. The CHAMP programme offers good opportunities for building or strengthening partnerships between large firms and their subcontractors, firms in the same industry or region, or universities and businesses, which in turn can give rise to positive externalities. Because training sessions are organised in the context of these partnerships, they can be better focused and more relevant to business needs, with an immediate payoff in terms of increased productivity for both the beneficiaries (SME employees) and the organizers (in particular, large firms).

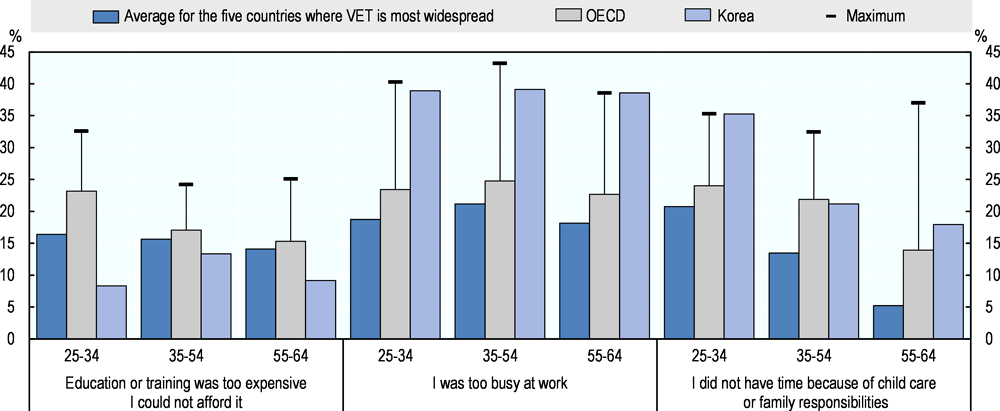

Time-related constraints are a major obstacle to training participation in Korea, for all age groups (Figure 3.5). Being too busy at work is the most prevalent reason reported by workers to explain why they did not participate in any VET programmes albeit they would have wanted to do so. This reason represents almost 40% of all answers in the age group 55-64, the highest proportion among the OECD countries for which information is available and nearly twice the average for these countries. When accounting for childcare and family responsibilities, time-related constraints represent 56% of all answers, 20 percentage points more than the cross-country average for this group. Conversely, financial constraints do not appear to constitute a major obstacle to training participation for older workers, accounting for only 9% of all answers in Korea. This is well below the OECD average for this age group.

Figure 3.5. Lack of time is the main obstacle in Korea to participate in vocational education and training

Note: The five countries are: Denmark, Finland, Norway, Sweden and the United States. OECD is a weighted average of the 22 countries in PIAAC Round 1.

Source: OECD Survey of Adult Skills (PIAAC), 2012, http://www.oecd.org/skills/piaac/.

Policy priority should be placed on easing the time constraints Koreans face to participate in training. The new guidelines on working time are an important step forward as they should help reduce the incidence of very long working hours. However, additional measures should be taken, notably for SMEs that often face labour shortages and therefore may experience strong difficulties in freeing up time for their employees to take training. This situation creates a vicious circle whereby poor working conditions and career prospects render it difficult for SMEs to attract skilled workers, which in turn deteriorates working conditions by imposing long working hours on incumbent workers, thereby limiting their training opportunities. Breaking this vicious circle would require measures helping SMEs to find and hire replacement workers quickly, in addition to financial supports such as hiring subsidies and/or subsidised training leaves for employees. These support measures could be combined with job placement services provided by the Public Employment Service (PES).

The Danish Job-rotation scheme is a good example of an integrated approach, combining up-skilling of incumbent workers with work practice and network building for unemployed persons. Under this scheme, employers can set up a training plan for their employees in cooperation with the municipal job centre, benefit from assistance in recruiting replacement workers and receive a public subsidy for hiring a long-term unemployed to replace the employee on training. The replacement worker can also receive a short training before starting work.

A similar scheme could be implemented in Korea, for example in cooperation with the Job Hope Centres for middle-aged and elderly people (see further below). Such a system could provide networking opportunities and on-the-job training to workers who have to start a second career after retirement from their main job, while ensuring better access to VET for middle-aged and older workers to upgrade their skills and stay longer in their main job. Such scheme could also be combined with the CHAMP programme to encourage temporary transfers of employees from large firms to SMEs and allow workers in SMEs to take time off work in order to receive training. To ensure a successful implementation, an integrated approach involving the PES and the VET consortiums established under the CHAMP programme could be an effective way to provide more and better training opportunities in Korea, notably for disadvantaged workers.

Enhancing the ability of the VET system to deliver the right skills for jobs

VET serves two main purposes: providing job-related skills with a direct return on productivity, employability and earnings, and providing foundation skills, which have less immediate returns but are essential to support lifelong employability. Effective VET systems must find the right mix, targeted to industries, firms and occupations, as well as workers. The appropriate skills mix tends to evolve throughout the working life, with foundation skills becoming less important as people grow older. Programmes designed on the basis of an apprenticeship concept – combining short classroom sessions with a firm-based approach – could be effective for older workers, as could be informal and self‑determined training with a clear focus on practical and relevant work problems.

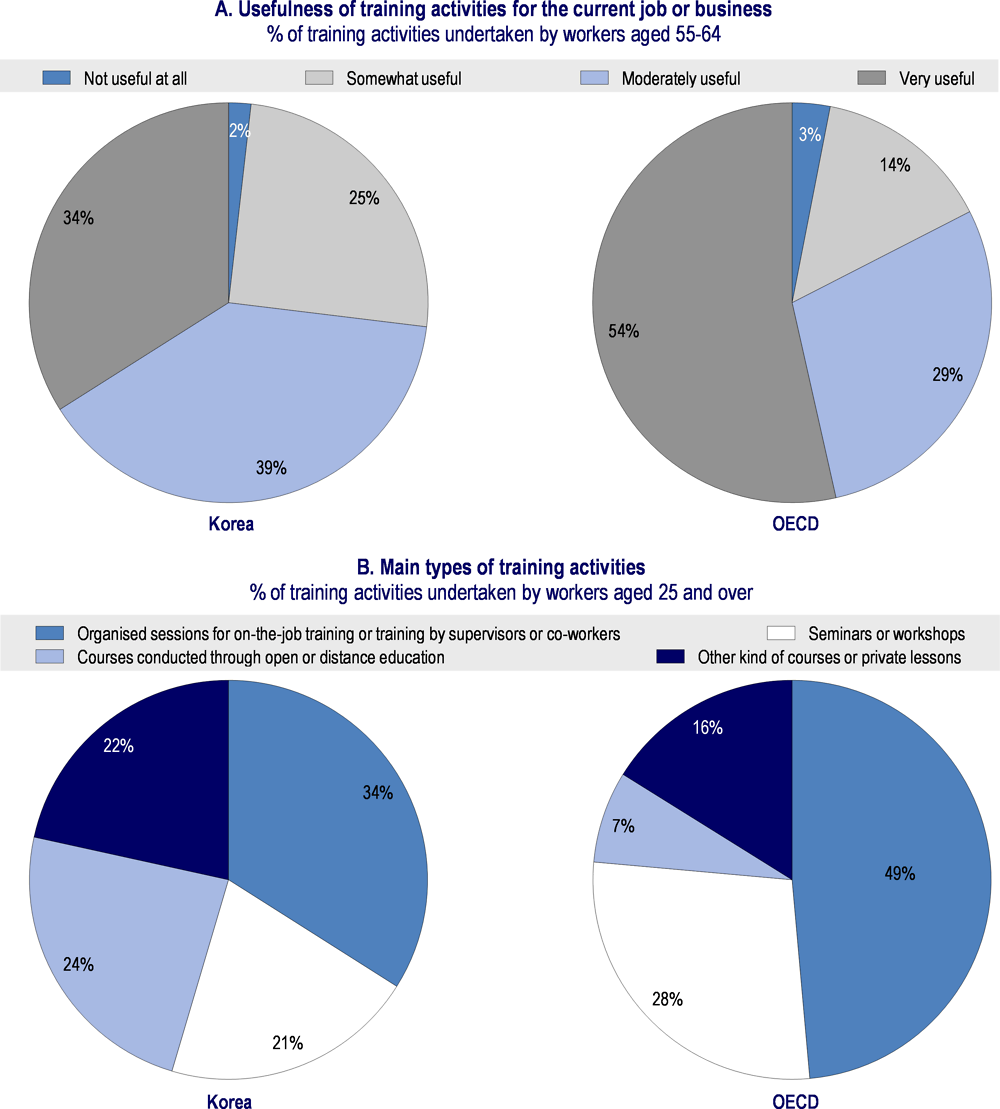

Results from PIAAC suggest there is scope for improvement in this respect. Only one in three older workers in Korea rate the relevance of their recent training activities as “very useful” for their current job, as compared with 54% on average in the 22 OECD countries for which information is available (Figure 3.6). Some 27% of these training activities were reported “somewhat useful” or “not useful at all”; this is well above the cross‑country average of 17% for this age group. With on-the-job training accounting for only one-third of all training activities, the Korean VET system focuses less on helping workers to deal with practical issues they may encounter in performing their current job duties than is the case in other OECD countries, where on average half of all training activities are on the job. By contrast, open or distance learning is relatively widespread in Korea, accounting for 24% of all training activities (7% on average in OECD countries). A common pitfall of these training methods is to follow a too theoretical approach that is not sufficiently attuned to real work activity, notably for older workers.

Figure 3.6. Fewer older workers in Korea than in other OECD countries consider their training activities as very useful

Note: Open or distance courses are similar to face-to-face courses, but take place via postal correspondence or electronic media, linking instructors/teachers/tutors or students who are not together in a classroom. Organised sessions for on-the-job training or training by supervisors or co-workers is characterised by planned periods of training, instruction or practical experience, using normal tools of work. Courses are typically subject oriented and taught by persons specialised in the field(s) concerned. They can take the form of classroom instruction (sometimes in combination with practice in real or simulated situations) or lectures. OECD is a weighted average of the 22 countries in PIAAC Round 1.

Source: OECD Survey of Adult Skills (PIAAC), 2012, http://www.oecd.org/skills/piaac/.

Open or distance learning and on-the-job training can be useful to reach out to SMEs. These training methods are very flexible, making it possible to take better account of SMEs organisational problems and barriers for training. Sessions can be adapted to a daily work schedule as they can take place at the worksite and be scheduled according to the workload. To be effective, they require a properly designed assessment whereby training needs and objectives are identified precisely. Open or distance learning will best suit workers who prefer to learn alone at their own pace.

Open or distance learning programmes require high-quality service providers to be effective. While the same holds true for all employment and training measures, this is especially true in this case as a number of specific implementation issues must be handled by efficient intermediaries, able to identify specific needs and offer flexible and innovative solutions tailored to those needs. Regular and rigorous evaluation of training activities and providers is important in this regard. As mentioned in OECD (2014), these types of exercises are mostly done at the national level, whereas at the local level there tends to be less analysis of the overall impact of programmes and whether they are meeting their objectives. As local governments have a role in designing additional programmes, there should be a greater focus on evaluating local policies and programmes. Information on what works could be shared across localities in Korea as well as with national ministries to inform future programme and policy design.

Making skills and competencies acquired throughout working lives visible

Having a clear picture of existing skills and qualifications and a better understanding of future skill needs, is a requirement for rational and efficient investments in vocational education and training by individuals, firms and society as a whole. This requires two tools: relevant qualification systems, adequately reflecting the supply and demand of skills and competencies; and reliable procedures to assess and validate skills and competencies that people acquire during their careers. Formal validation is necessary in order to be able to recognise skills adequately and render them transparent to employers.

In case of involuntary job loss, the recognition of prior learning and acquired experience can play a crucial role in helping workers find a quality job that matches their actual competences and skills. This is especially important for mid-career and older workers, whose initial qualifications may be outdated. Many of them have acquired new skills through their work experiences, but most often they do not have certificates to prove it. In Korea, providing workers with opportunities to assess and validate their skills and competencies against a national qualification standard before or, at the very least, as soon as they have to leave their main job for mandatory early retirement, would help them build a second career that better matches their expectations and abilities. While there are some early-intervention measures designed to help workers approaching the age of mandatory retirement to prepare their employment transition, these measures mainly consist in outplacement services. As part of these initiatives, greater attention should be paid to formal validation of acquired experiences.

From a longer-term perspective, the main challenge faced by Korea is to better link education, including vocational education and training, with labour market needs. While the education level of young cohorts and business needs have changed dramatically in the last few decades, the VET system has not been responsive enough to this fast-changing environment. In particular, the national qualification system has remained focused on technical skills and does not constitute anymore an adequate screening device for employers, a proper signalling device for employees, and a relevant policy tool for public authorities to evaluate skill developments and anticipate skill needs (OECD, 2014).

The development of new National Competency Standards (NCS) is an important step forward as it provides a picture of the skills required for various jobs, in line with the competencies needed in the labour market. But the big remaining challenge for the government is to operationalise and promote the use of the NCS. This requires a comprehensive package of measures to reflect the NCS in both VET provision and qualification frameworks. The reform process is underway (MOEL, 2015), but more should be done to mobilise all relevant stakeholders, including VET providers, employer associations and trade unions, as ultimately they will be the main channel for disseminating and implementing successfully the NCS (OECD, 2014).

Labour market reforms could contribute to foster the interest of social partners in the NCS. From the perspective of trade unions, the benefits from having effective instruments for increasing, assessing and recognising the value of lifelong learning are currently limited due to the deeply-rooted seniority‑based system for setting wages and granting promotions, which weakens the link between competencies and earnings. From the perspective of employers, the widespread practices of long working hours and mandatory early retirements reduce the value of investing in the skills of their workforce: long hours can compensate for reduced productivity, and early retirements can be used when the gap between earnings and productivity becomes too large. The policy measures taken recently in those areas can bring about some changes in the status quo as an effective VET system, acknowledged by business associations and approved by trade unions, would constitute the best guarantee for ensuring a fair transition towards a competency-based labour market.

Helping older jobseekers back into quality jobs

Improvements in vocational education and training are critical for Korea to keep older workers employable and make it possible for them to stay in their jobs longer. But it will take time until the current wage and employment practices, including seniority wages and honorary retirement, will be overcome and even then, not all older workers will be able to retain their jobs. Providing older jobseekers with effective support to move back into rewarding and productive jobs, is essential to foster a more inclusive labour market. In the context of Korea’s rapidly ageing population, combined with a high degree of labour mobility of older workers, it is important that middle-aged and older jobseekers have access to good employment services and effective active labour market programmes (ALMPs) to help them make job transitions and to minimise the costs of those transitions.

Strengthening the capacity of the Public Employment Service

MOEL Job Centres are the primary point of contact for jobseekers in Korea which can be characterised by a labyrinth of employment services that exist alongside each other (see Box 3.2). MOEL Job Centres are responsible for administering unemployment benefits as well as providing job counselling, job training, job matching, placement, career guidance and vocational psychology testing. MOEL Job Centres also provide job-matching services for firms which have vacancies; administer wage and training subsidy programmes aimed at firms and workers; and visit firms to identify problems they face with recruitment and labour regulations. They also work with local governments and communities to encourage job creation at the regional level.

Box 3.2. The structure of employment service provision in Korea

Korea’s employment services are regulated through three Acts: the Framework Act on Employment Policy, the Employment Security Act, and the Employment Insurance Act (KEIS, 2012a). The Framework Act provides strategic orientation for labour market policies and sets out the governance structure for programme implementation and evaluation, while the other two acts contain practical provisions for implementing employment services and unemployment insurance benefits, respectively. In addition, the Framework Act sets up the Korean Employment Information Service (KEIS), responsible for collecting information and monitoring and assessing programmes and service providers on a regular basis.

For older workers, there are two broad categories of employment services in Korea: those available to all jobseekers and specific services for workers aged 40 and over. In both cases, publicly funded employment services can be classified into those directly managed by public agencies and those commissioned to non-governmental organisations or employment agencies in the private or not-for-profit sector. The service structure in Korea is rather complex, with many providers of employment services (see Table 3.1).

Table 3.1. Employment services for middle-aged and older workers (2014)

|

Job Centers (% change since 2007) |

Employment Support Centers |

Job Hope Centers |

Senior Citizen Talent Banks (% change since 2007) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Managing body |

Central government (MOEL) |

Local governments |

Tripartite organisation (KLF) |

Non-profit organisations |

|

Main services |

Unemployment benefits administration, job-matching services and ALMPs (including training) |

Job-matching services |

Job-matching and vocational guidance |

Job-matching services |

|

Beneficiaries |

All jobseekers |

All jobseekers |

Workers aged 40+ |

Jobseekers aged 50+ |

|

N° of centers |

86 |

243 |

25 |

53 (+6) |

|

N° of staff |

4 563 (+56) |

1 364 |

174 |

106 (+6) |

|

N° of registered job vacancies |

1 695 711 (+68) |

n.a |

46 242 |

195 916 (+146) |

|

N° of registered jobseekers |

||||

|

All age groups |

2 933 866 (+49) |

n.a |

- |

|

|

… among which EI recipients (%) |

33% |

n.a |

- |

|

|

Persons aged 40 and over |

1 306 362 (+82) |

n.a |

85 100 |

167 199 (+118) |

|

… among which EI recipients (%) |

45% |

n.a |

23% |

n.a |

|

Jobseekers per staff |

643 (-4) |

n.a |

489 |

1 577 (+106) |

|

Jobseekers per job vacancy |

1.73 (-11) |

n.a |

1.84 |

0.85 (-11) |

Source: Work-Net, Middle-aged Job Hope-Net, Employment Insurance.

The Job Centres run by the MOEL are the primary providers of employment services. Job Centres have seen a significant increase recently in the number of staff, jobseekers served and job vacancies handled. Middle-aged and older workers have greatly benefited from this improvement: the number of jobseekers aged 40 and over served by Job Centres increased by 82% (2007-14), compared with a 49% increase for all age groups over the same period. The number of vacancies handled by Job Centres also increased, by 68%, resulting in a slight decrease of the number of jobseekers per vacancy which in turn may facilitate their placement. However, with on average more than 600 registered jobseekers per staff, the caseload of a Job Centre counsellor remains extraordinarily high.

Local governments also provide employment services through a network of regional or municipal agencies, the Employment Support Centres, partly financed by the central government. The latter has primary responsibility for the design and implementation of national employment policies, while local governments develop specific programmes tailored to local labour market needs. Local governments have a more extensive network of agencies than the MOEL (243 Employment Support Centres in 2014 in comparison with 86 Job Centres nationwide), but their agencies tend to be small (5‑6 employees) and merely play a supporting role in the service delivery chain, with a focus on job-placement services in connection with direct job creation programmes offered by local governments. They are also responsible for activating recipients of social assistance.

To assist late career workers in their employment transitions, in 2013 the government integrated outplacement support centres and job centres for older professionals into Job Hope Centres for middle-aged and older workers. They are managed by the Korea Labour Foundation, a tripartite body under the umbrella of the MOEL, and provide services similar to those provided by MOEL Job Centres but they are better resourced as they tend to serve more vulnerable jobseekers, on a more individual basis. Only 23% of jobseekers registered with Job Hope Centres in 2014 were receiving EI benefits, while the proportion of EI recipients was nearly double for jobseekers (aged 40 and over) registered with a Job Centre. Job Hope Centres also provide vocational guidance and outplacement services to employees approaching the age of mandatory early retirement and willing to prepare for their second career. Considering the broad range of activities, the number of jobseekers per Job Hope Centres staff are high (albeit lower than that in Job Centres), all the more so as their customers need more intensive assistance and are harder to place.

To ease pressure on Job Centres, MOEL has been active in promoting the development of employment agencies in the private and not-for-profit sector. As a result, these play an increasingly important role in facilitating job matching for the most employable on the one hand and delivering the Employment Success Package Programme (ESPP) on the other. ESPP is directed towards specific groups facing difficulties in the labour market and at high risk of poverty – a significant number of whom middle-aged and older jobseekers – and provide these groups with customised assistance and enhanced services to help them back into work (OECD, 2013b; OECD, 2018a).

For job-matching services, a network of private employment agencies and training institutions, the so-called “Senior Citizen Talent Bank” designated by the MOEL, is directed especially at helping jobseekers aged 50 and over find a new job. This network has expanded markedly over the last decade, with the number of jobseekers served and job vacancies handled more than doubling since 2007. However, the majority of Talent Banks are micro businesses with one or two employees, offering placement service for rather precarious jobs in most cases (part-time jobs and jobs of short duration).

Finally, the increased use of the internet as a job-search tool is also contributing to the expansion and development of employment services in Korea. MOEL’s Work-Net website is an important tool for connecting jobseekers with available vacancies. Work‑Net was launched in 1998 and its functions have expanded over time. From 2011, users have been able to search for jobs listed on other privately operated websites and from local governments. Users can also view their job application history, take vocational aptitude tests and manage their relationship with the Job Centre online, including updating their jobseeker registration and applying for courses or counselling sessions. Employers can list vacancies and search for new staff. The system also provides information for counsellors and local governments providing employment services.

Source: KEIS (2012a), Public Employment Information System, Korea Employment Information Service, Eumseong, OECD (2013), Korea: Improving the Re-employment Prospects of Displaced Workers, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264189225-en, OECD (2018), Towards Better Social and Employment Security in Korea, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264288256-en.

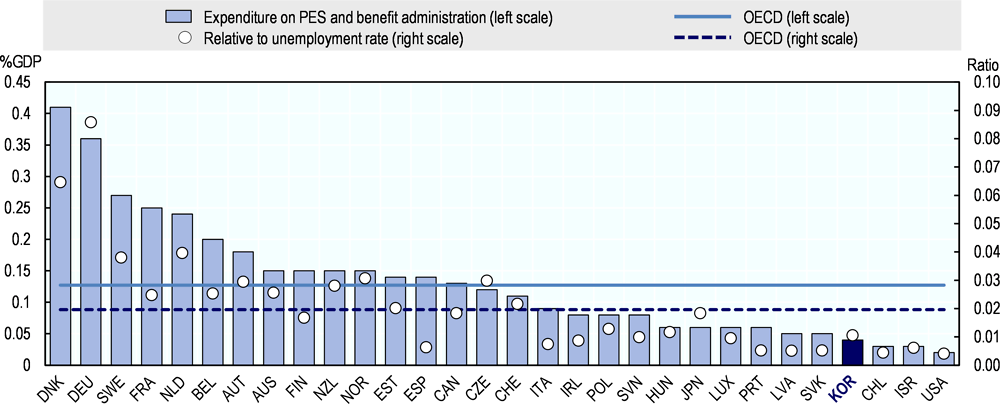

In view of their extensive responsibilities and central importance in the delivery of employment services, MOEL Job Centres are under-resourced. At 0.04% of GDP, public expenditures on delivering services, administering benefits and dealing with clients are the fourth-lowest in the OECD area; less than a quarter than the OECD average of 0.13% of GDP and only about a tenth of the spending in some high-spending countries like Germany and Denmark (Figure 3.7). Even taking into account the low level of unemployment in Korea, public spending on employment service operations remains low: The ratio of PES spending (as a share of GDP) to the unemployment rate is nearly half the average ratio for OECD countries, and four to eight times lower than in the countries with the highest spending-to-unemployment ratios.

Figure 3.7. Employment services in Korea are highly under-resourced

Note: Data for France, Italy and Spain refer to 2015.

Source: OECD Dataset on Public Expenditure and Participant Stocks on LMP, https://stats.oecd.org//Index.aspx?QueryId=8540.

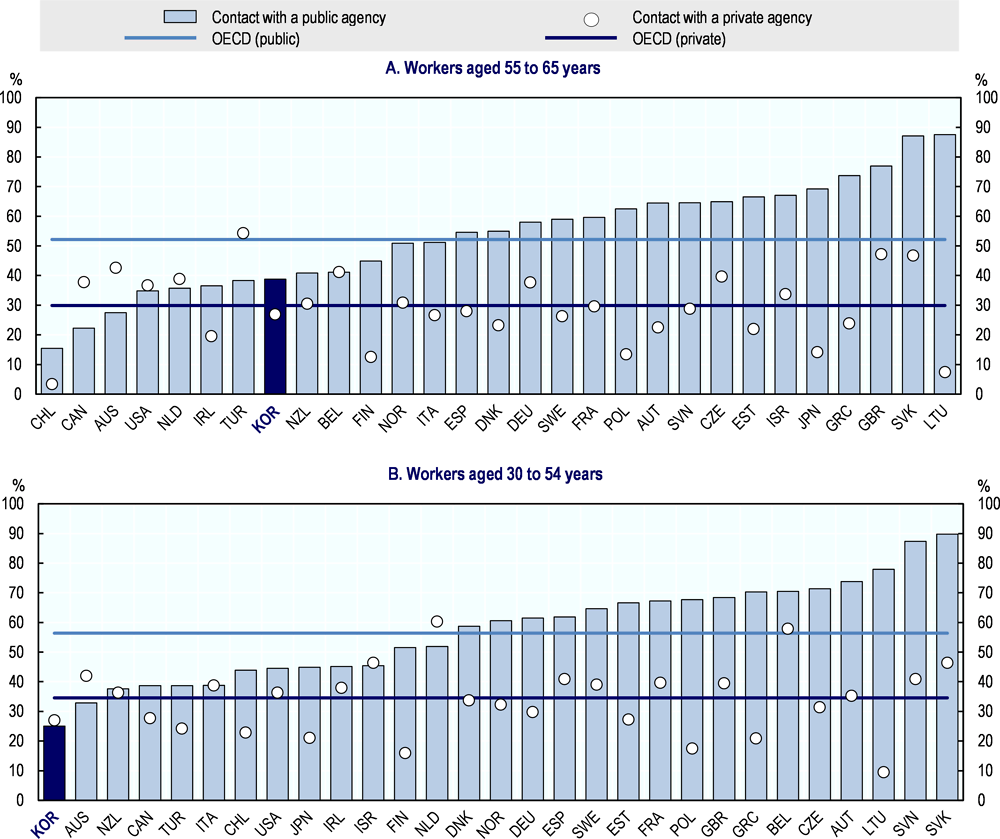

Consequently, although the number of jobseekers who register with MOEL Job Centres has increased markedly over the past decade, there are still relatively few people in Korea who use the PES to find a new job. Only one in four prime-age jobseekers in Korea report they have been in contact with the PES in the past month to find work, the lowest proportion in the 22 OECD countries for which information is available, and 30 percentage points below the cross-country average. Among jobseekers aged 55 to 64 years, at close to 40%, the share using the PES in their job search is somewhat higher – though still 15 percentage points below the corresponding OECD average (Figure 3.8).

Figure 3.8. Employment services are used less often in Korea than elsewhere by people looking for a job

Important steps have been taken in recent years to ease pressure on the under‑resourced MOEL Job Centres, with a significant increase in the number of Job Centre staff as well as an increased use of external providers to contract out more employment services, in particular for middle-aged and older workers. In addition, the MOEL’s Work-Net website has become an important tool for connecting jobseekers with available vacancies, which should allow staff to spend more time providing face-to-face counselling to jobseekers. Yet, older people, notably the most vulnerable among them, seldom use the internet as a job‑search tool because they often lack the basic ICT skills needed to use online services. For jobseekers aged 50 and over, a recent study by Choi (2016) shows that personal contacts through family, friends, former colleagues or business contacts remain the primary way of finding work. This tends to lengthen unemployment spells as employment agencies are more effective than personal contacts in providing older jobseekers with adequate employment opportunities.

In order to secure successful employment transitions, additional public resources should be devoted to employment service provision in Korea. Despite recent improvements, Job Centre staff remains overloaded and has no choice other than concentrating on the provision of job-matching services, with limited attention to reaching out to older jobseekers, monitoring job-search activities and assuring the quality of job matches. Older jobseekers in particular benefit from face-to-face help by professionals to find a decent job after they retire from their main job. As long as early and honorary retirement practices force older workers out of employment, even if on a “voluntary” basis, every effort must be made to help them back into good salaried jobs or self-employment.

Improving the quality of employment services

A pressing concern is to improve the quality of job matches for older jobseekers, who often move into low-paid and insecure jobs that in practice do not provide entitlement to social insurance. Many non‑regular workers are trapped in a vicious circle whereby they are more difficult for the public authorities to reach because they are not eligible for EI benefits, which in turn puts them under pressure to take up any job in order to make ends meet, no matter what kind of job it is. When the pension system will be fully mature, there is a distinct risk that the employment rate of older workers could decline as for many of them there will be a real trade-off between continuing to work in a job of low quality and retiring. It is important that public service providers are given incentives to pay greater attention to the quality of jobs offered, beyond helping older jobseekers return to employment quickly.

In Korea, there is a legal requirement for public authorities to evaluate and assess on a regular basis the performance of public employment agencies, as well as that of contracted agencies in the for-profit or non-profit sector. The evaluation results have an impact for Job Centre staff, in terms of pay, and for external private providers, on conditions of the renewal of their contract with the PES and the amount of payment they receive from the government.

The incentives for private providers have been changed several times in the past few years, moving the system from paying for services to paying for employment results and further to rewarding more sustainable employment and, in the most recent step, in 2017, employment of better quality (measured by the person’s wage in the new job). This is the right strategy although an evaluation of the system is lacking and the frequent changes, sometimes from one contract to the next, make it difficult for providers to adjust to any new setup. Added to this, the duration of provider contracts is very short – just one year – making it difficult for providers to invest into longer-term competencies of their staff. A quality assurance framework is also in place in Korea to ensure only good service providers stay in the market. However, the framework could be strengthened and better enacted, as it has proven difficult to eliminate underperforming providers in a period of rapidly growing outsourcing and service demand (OECD, 2018a).

Incentives for MOEL Job Centres could be strengthened along these lines, to reflect the recent shift to a stronger focus on finding good-quality employment also for older jobseekers. The current performance evaluation of Job Centres is predominantly based on outputs such as the number of jobseekers served, job vacancies handled and successful placements. Such approach could encourage the PES to place older jobseekers quickly into low-paid and highly insecure jobs, although a new performance management system was introduced in 2011 that includes job quality indicators such as the earnings level, actual social insurance coverage and employment stability of new hires (KEIS, 2012b). Job quality aspects should be given greater attention and Job Centre staff should have incentives to examine basic working conditions, including the safety of the working environment, before matching jobseekers with employers.

Measuring and monitoring the quality of services should also include a thorough evaluation of active labour market programmes, as required under the Framework Act on Employment Policy, with the aim to abolish ineffective and to promote the most effective and efficient programmes. It is important that rigorous programme evaluation includes a variety of outcomes including post‑programme employment rates but also a number of job quality indicators such as career progression, employment stability, employment security and the level of wages.

Providing effective employment service at an early stage

In a strongly segmented labour market like in Korea, the first job after mandatory early retirement can have important consequences for the remaining working life. Early intervention measures can be particularly effective in helping workers keep a firmer foothold in the core labour market as they age. Early intervention in this case would mean to assist workers before they reach the age of mandatory early retirement. The situation here is similar to that of workers who were made redundant for economic reasons who, as recent OECD analysis shows, are helped best and most effectively through measures that start before their actual dismissal (OECD, 2018b).

Starting a second career is challenging and needs to be well prepared so that it can be achieved successfully, in a productive and rewarding job. As the age for mandatory early retirement is known well in advance by both parties and without uncertainty, early intervention should be relatively easy to organise. Information about existing employment services and support measures should be provided on a systematic basis to all workers who are approaching the age of mandatory early retirement in order to encourage and enable them to prepare for their second career and to make the best use of their acquired skills and competencies.

There are different ways to provide early intervention or outplacement services for (potential) early retirees. Such services can be provided by firms themselves, either publicly subsidised or not, or by the PES, or by specialised employment services. A number of large companies in Korea provide in-house outplacement services to smooth the dismissal and retirement process, to maintain good community relations and to help workers approaching mandatory retirement with the transition into their “second career”. In this regard a forthcoming reform, which was long debated before actually implemented (MOEL, 2014), is very welcome: The government plans to revise the law to make the provision of outplacement services to early retirees mandatory for larger companies. The initial plan was to include all companies with 300 or more employees but this number is still under discussion. Consideration should be given to expanding this regulation to also include mid‑sized companies with 50-299 employees. Evidence suggests that initiatives by companies can have good outcomes in terms of the quantity and quality of job opportunities for their early retirees. In part these positive outcomes may reflect the good reputation these large companies have among prospective employers as well as their large network of subcontractors which often face labour shortages (because they pay a much lower wage) and may constitute a source of potential employers for those retiring early from a large firm.2

Between 2001 and 2013, a special programme was in place in Korea – the Job Transfer Support Programme – to encourage more firms to provide outplacement services. It was financed from the EI scheme and applied to contributing firms and employees. The number of workers benefitting from the programme, however, was small – some 1 400 workers per year (MOEL, 2012) – because the take-up in small companies was very low and deadweight costs were massive (KLI and KRIVET, 2007) as the subsidy was used mostly by large companies, which would have offered such services themselves anyway, as part of their normal management practices. The recent abolition of the programme was, therefore, reasonable. However, early intervention services for small and medium-sized companies, matching the mandatory outplacement services of large companies, are critical. Such services must be provided by the existing employment service infrastructure and include active outreach to workers approaching the age of retirement from their main job. Active outreach is also important because older jobseekers entitled to EI and severance payments may not be aware initially of how precarious their situation is, and will tend to turn to the employment service much later than they should have done.

Much can be learned in this regard from policies targeting displaced workers, i.e. workers who have lost their jobs for economic reasons (e.g. due to plant closure or downsizing). The most vulnerable among them are also older workers with long tenure and workers who worked in small companies. Sweden and Canada have effective policies in place to secure prompt support for this group, which offer good benchmarks for mandatory retirees in Korea. Displaced workers in Sweden will be supported very quickly through the Job Security Councils. These Councils, which are funded by employer contributions and regulated in collective agreements, provide services to all workers in a sector or an occupational field. Services are provided even before a worker is actually dismissed and irrespective of the size of a company or a dismissal thus also including all supply-chain workers (OECD, 2015a). Workers in Canada who are displaced from a firm in the course of a dismissal that affects less than 50 people can enrol in an outplacement plan run by the countries’ public employment service. In this way, workers from small enterprises can receive the same kind of support as those dismissed from big enterprises which, similar to Korea, are obliged to set-up their own outplacement programme (OECD, 2015b).

Acknowledging the importance of (re-) employment support for the many early retirees, Job Hope Centres were created in Korea in 2013 as employment agencies specialised in the challenges of middle-aged and older workers (those over age 40). The centres, most of which operated by the tripartite Korea Labour Foundation (KLF), originated from the previous outplacement support centres which existed since 2005. Job Hope Centres offer outplacement programmes and counselling services to businesses which plan to provide outplacement services to their employees close to retirement as well as retirees. Services are tailored to individual needs and can include training or retraining before starting job search, as vulnerable older workers often lack basic ICT skills needed to use online job services. Job Hope Centre services are commonly processed in three stages, including diagnosis through one-on-one consultation with a professional to determine the direction of service; actual service execution based upon the employment activity plan prepared in stage one; and post-service management (KLF, 2016).

In 2016, there were 31 Job Hope Centres operating around the country. Their success has not been evaluated yet but the large caseload of almost 500 jobseekers per counsellor working in those centres (see Table 3.1 in Box 3.2) makes it difficult to provide services tailored to individual needs and to achieve the stated objectives. Funding for Job Hope Centres will have to be beefed up considerably to ensure all early retirees needing help – whether EI insured or not and including those retiring from companies with fewer than 300 employees – can be supported quickly and effectively. Effective employment services in other OECD countries typically operate with caseloads of around 100 clients, and caseloads much smaller than this to deal with disadvantaged jobseekers.

Streamlining and coordinating employment services

The plethora of employment services provided in Korea can make it difficult for jobseekers to know what services are available; how to access them; and which services to approach in which situation. There is also considerable room in the current structure for unnecessary duplication of services. There is scope in Korea for better coordinating the various employment services as well as streamlining and, possibly, merging some of them, to make the provision of services more efficient and more effective.

Korea is well aware of the complexity of its service landscape and has taken steps towards a more integrated delivery of employment and welfare services, through the creation of Employment and Welfare Plus Centres which will gradually replace the current network of close to 100 MOEL Job Centres. These new Plus Centres operate as a one-stop service which includes all MOEL and EI employment services but also welfare services provided by the local government and other outsourced services to address financial and family problems – the aim being to be able to offer the right service to the right people faster and more efficiently. The planned integration of the Job Hope Centres for middle-aged and elderly people into the Employment and Welfare Plus Centres could contribute to providing more integrated labour market services for older workers and enhancing their access to services. However, care must be taken in this process that the integration of services is not used to reduce total spending further as each and every service is under-resourced, as discussed above.

The biggest continuing segmentation in Korea is that between MOEL‑funded services – which are gradually integrated – and the employment services funded and provided by local governments. There is potentially considerable overlap and duplication of services although there may be a role for both sides. For instance, local government services can be better tailored to local needs and take advantage of closer links with local businesses. That said, in other countries local links would typically be exploited by local offices of an otherwise nationally or regionally structured service with a national supervisory authority. In Korea, the two services exist alongside each other, with limited links between them.

In this regard an initiative in one larger Korean city is a promising step to help jobseekers understand the services available and get in contact with the most appropriate provider to help them find new work: In Busan City, all employment service providers meet on a regular (quarterly) basis to share information and develop joint programmes. Bringing this idea to a structural level, recent efforts to give MOEL a broader role in coordinating services on a regional level are highly welcome. Sufficient resources need to be provided to ensure this role is taken serious and sufficient power be given to the coordinator to ensure the avoidance of duplication and to improve service efficiency.

Streamlining of services would also come with efficiency gains because, contrary to MOEL, local governments seldom devote sufficient resources to properly evaluate their programmes, even in well-resourced areas such as Seoul City. This limits opportunities for local governments to learn from each other’s (and from their own) experiences and for the most effective local programmes to be rolled out more widely. Future efforts to increase the role of local governments in providing active labour market programmes, in the context of an ongoing decentralisation process, should include a requirement for mandatory evaluation of all programmes, at least the larger ones, and devoting adequate resources for evaluation and sharing of results and experiences between regions.

In this regard, the approach in Denmark is worth mentioning where municipalities are in charge of delivering social and employment policy. Three steps are taken to ensure strong and coherent outcomes across the country: First, performance of every municipality is monitored rigorously by a regional supervisory body which can also provide support to poor performers. Secondly, the results of every single municipality (such as employment outcomes of single programmes for various groups of jobseekers) are made transparent and published instantly on a public website that can be accessed by every Danish citizen. Thirdly, regular exchange of good practices stimulates cross-municipality learning. In addition, Denmark has a system of financial incentives for municipalities to ensure that funding provided to them by the national government is used in an “active” way, to minimise people’s dependence on social benefits and maximise employment.

Finding the right mix of services for older jobseekers

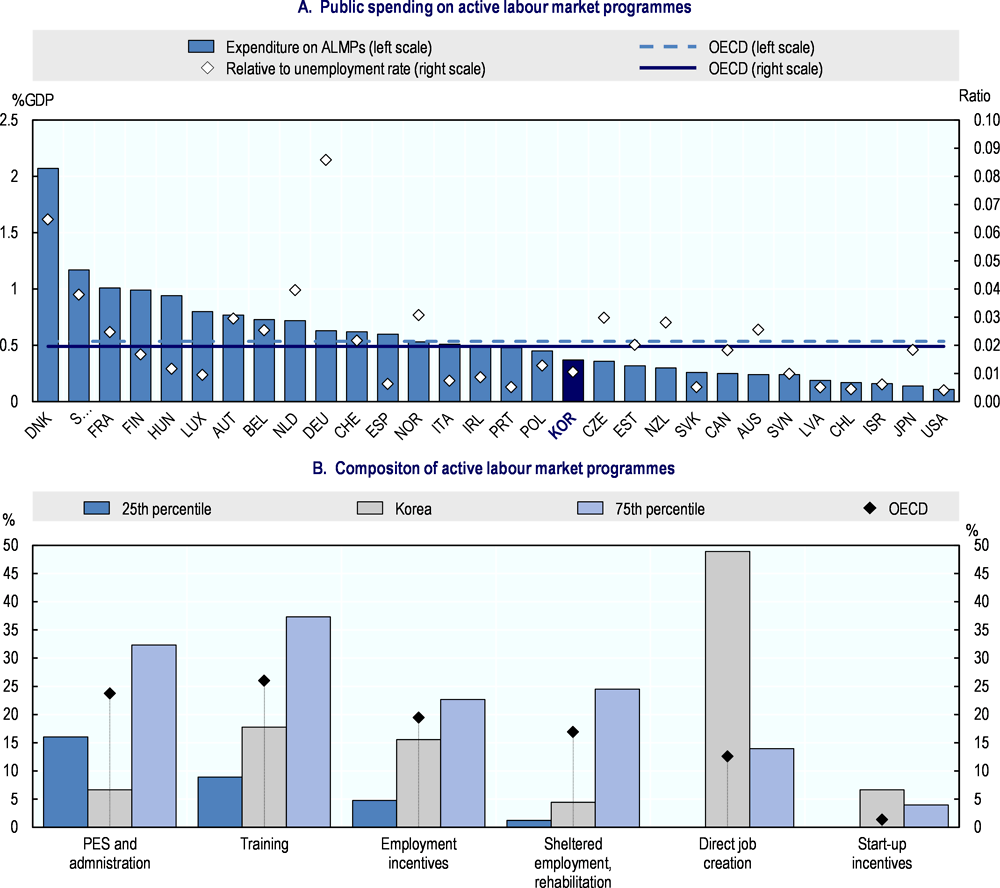

In 2016, following a continuous increase over a period of about a decade, Korea spent 0.37% of its GDP on active labour market programmes (ALMP), which is lower than the OECD average of around 0.5% of GDP (Figure 3.9, Panel A). The mix of programmes is very different from the mix provided in other OECD countries. Half of Korea’s ALMP spending is on direct job creation while spending on training and service operations – the biggest components in most other OECD countries – is rather low (Figure 3.9, Panel B).

Direct job creation

Direct job creation programmes have gradually been abolished in the past one or two decades in most OECD countries because they were shown to be ineffective, trapping people into low quality, public local service jobs rather than helping them into regular, non‑subsidised employment. To that extent, Korea should phase out some of its spending on such programmes especially for younger jobseekers in exchange for increased spending for measures that help them into higher-quality work.

Figure 3.9. Active labour market programmes in Korea are in most cases delivered as direct job creation schemes

Note: Data refer to 2015 for France, Italy and Spain.

Source: OECD Database on Labour Market Policies, https://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=LMPEXP.

However, direct job creation in Korea also has another important role as a programme to tackle the enormously high levels of poverty of older people, both in the age group 50-64 and 65 and over. Very different from other OECD countries, more than half of the total spending on direct job creation in Korea is for people over the age of 65 i.e. above the legal retirement age. This situation hints towards an important issue which characterises the policy challenge in Korea in many areas: the system must support those currently in troubles while being made fit for the future, when the structure and problems of the population will look different. The many very poor older people today, with low skills and low employability, need direct help which these job creation programmes provide. But in the medium term, direct job creation of this kind – which is to a large extent provided by local employment services – must be phased out as it is ineffective in helping people into well‑paid jobs of good quality. Meanwhile, as direct job creation traps older people in precarious employment, it should be coupled with efforts to improve their employability through vocational training so that more people can step into the regular, private labour market.

Employment incentives

Employment subsidies will also help older workers and jobseekers to access the labour market. Such subsidies can be useful in two forms: Incentives to retain workers in their main job and incentives to help jobseekers into new jobs of decent quality. Remaining longer in the main job is the most effective way to keep the quality of employment high. The main policy tool encouraging employers in Korea to retain their older workers longer is the subsidy for the wage peak system, introduced in 2006 and given to employees who accept a wage cut which is partially compensated. In view of the gradual increase in the age of mandatory retirement, the wage peak system should be introduced by firms more widely. Trade unions also need to cooperate on introducing the system to improve employment prospects. Otherwise, firms facing a loss in competitiveness would be prompted to continue pushing out older workers before the mandatory retirement age.

The most important hiring subsidy for older jobseekers in Korea is the Internship Programme of the Middle and Older‑aged, introduced in 2013, which provides internship opportunities for unemployed people aged 50 and over to connect to regular jobs. Firms that hire an eligible worker can receive a subsidy equal to 50% of the wage paid (up to KRW 800 000 per month) during an internship period of three months. After this period, KRW 650 000 per month can be paid for another six months if the employer offers a regular job to the intern. Take-up of the scheme, however, is low: In 2014, 7 734 older workers had been hired as interns and 4 795 of them had then been converted to regular workers. More can be done to promote the scheme, especially also among smaller companies. Changes could include: i) reducing red tape to make it easier for companies to apply for the subsidy; ii) making the subsidy more flexible in time as the six-month period may be too short for employers to consider applying for it; and iii) integrating the hiring subsidy with targeted training schemes to improve the employability of eligible jobseekers to make them more attractive for potential employers.

Individualised services for individual needs

The most innovative labour market programme in Korea in recent years is the Employment Success Package Programme (ESPP). ESPP is a comprehensive intervention which can last up to one year and is tailored to individual needs and targeted on three groups: jobseekers with very low income of less than 60% of the median wage, irrespective of age; youth and other disadvantaged groups such as disabled jobseekers or lone parents, irrespective of their income; and other vulnerable groups with incomes below the median, including middle-aged and older jobseekers.

The strength of the programme is that it combines: 1) intensive counselling, including psychological testing, group counselling and the establishment of an individual action plan; 2) targeted training in line with individual needs, including vocational training and business start‑up training; 3) job placement support, including the provision of job-search skills; and 4) financial incentives for jobseekers to participate in the programme and in training and to stay in employment afterwards. Such, it combines all those elements that have been shown to make activation successful.

ESPP was first introduced in 2009. The number of participants increased rapidly and continuously, from 20 000 in 2010 to 300 000 in 2016. The increase concerned young people mostly, who initially were not included in the target group, but also affected all other groups. In 2015, one in four ESPP participants were over age 40, most of them belonging to the low-income group, 12% were over age 50 and 3% over age 60.

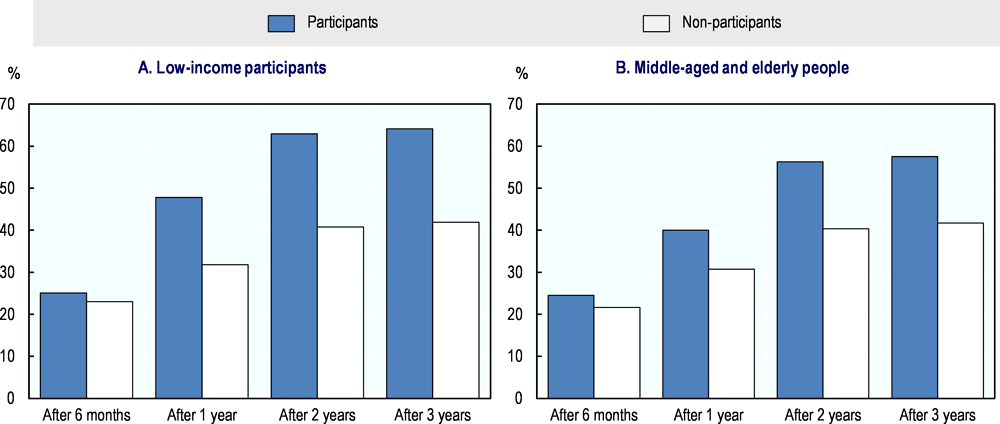

A recent performance evaluation has shown that ESPP is effective in bringing programme participants into employment, including middle-aged and older jobseekers as well as the low-income group of which 20% are over age 50 and 44% over age 40 (Figure 3.10).

Figure 3.10. ESSP participation improves employment outcomes for all participants, including older jobseekers

Note: ESPP: Employment Success Package Programme. Non-participants are people who have applied for ESPP but were not selected for the programme.

Source: Lee, B. (2016), “An evaluation of the employment impact of the Employment Success Package Program”, Korea Labour Institute, Seoul.

ESPP participation should be expanded further to include a larger share of older jobseekers which benefit from the more individualised support. Administrative data also suggest that in the future more emphasis should be put on securing employment of better quality for those using ESPP: while most participants complete the programme, many of those initially moving into employment are jobless again six months later and half of those finding employment are in low-paid, non-regular jobs (OECD, 2018a).

Improving the working conditions for older workers

Good working conditions can play a significant role in an era of rapidly ageing societies as a means to keep older workers in the labor market longer. Korea has seen significant progress on working conditions over the past decade through declining working hours and the establishment of occupational health and safety systems. However, the situation still needs to be improved especially for older workers. They face relatively poor working conditions including long working hours and more frequent occupational accidents.

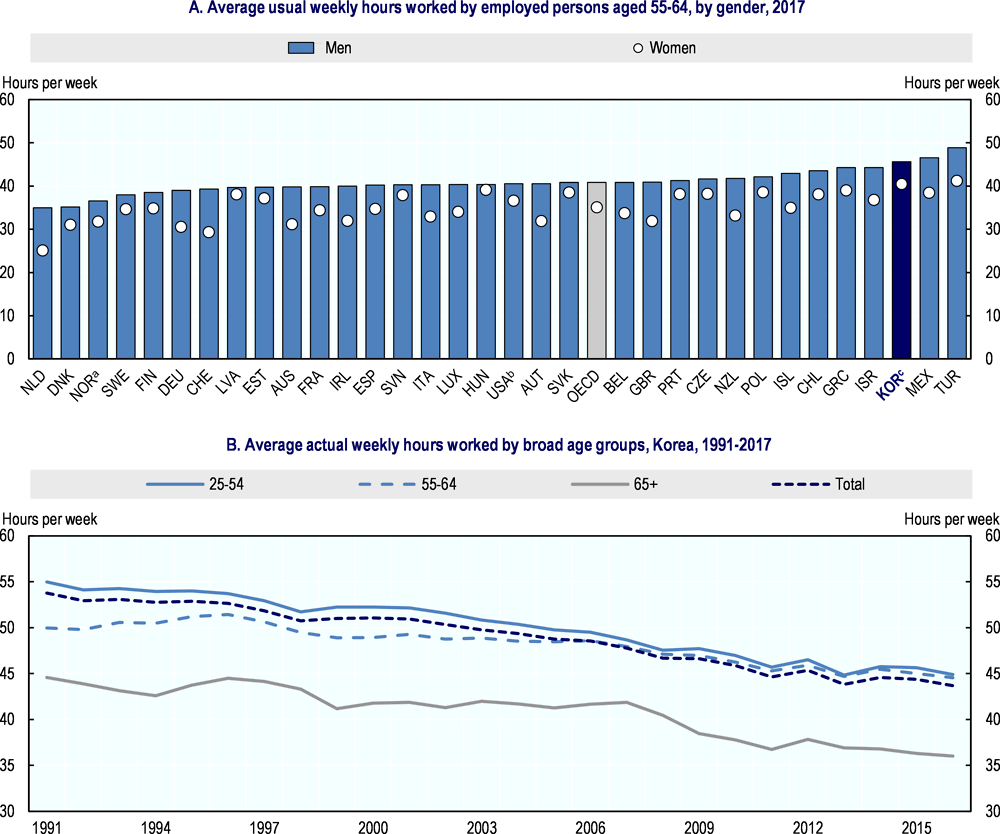

Reducing long working hours

Korea has had among the longest working hours in the OECD area for many decades. The average number of hours actually worked per workers in 2017 was 2 024, well above the OECD average of 1 759 hours. Long working hours are widespread regardless of age, gender, company size, industry, and region, and older workers are no exception: usual weekly working hours for Koreans aged 55-64 years are among the longest in the OECD for men and the longest for women (Figure 3.11, Panel A). While accustomed to long working hours, they also choose to work longer to complement their low hourly wages.

Figure 3.11. Older workers in Korea work longer than in almost any other OECD country

Note: The OECD is an unweighted average of the countries shown.

a. Data refer to 2016.

b. Data refer to employees only.

c. Data refer to actual hours worked.

Source: OECD Dataset on Average usual weekly hours worked on the main job https://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=AVE_HRS.

Long working hours can have particularly harmful consequences for older workers, in terms of both their health and their skill development, as this has adverse impacts on their participation in education and vocational training (see above) which in turn perpetuates the high incidence of low-quality jobs. Older workers in Korea, on average, work just as much as their younger peers. However, recent efforts by the Korean government to reduce working hours have borne fruit: average monthly hours of work across all age groups have declined from 217 hours in 1993 to 198 hours in 2006 and 180 hours in 2017, according to the Survey on Labour Conditions. The downward trend in average hours worked has affected all age groups to a similar extent (Figure 3.11, Panel B). A further reduction in working hours for all workers in Korea is essential.

The decline in Korea in average hours worked is a direct consequence of the recent reduction in statutory working hours. Since 2004, the legal work week in Korea is 40 hours (previously 44 hours and before 1990, 48 hours) plus up to 12 hours of overtime work. Like in previous instances, the 40-hour week in Korea was introduced gradually over time, according to enterprise size, in a first step, in 2004, affecting companies with 1 000 or more employees only and in a last step, in 2008, those with 5-19 employees.

In practice long working hours remain widespread, however. Firms prefer to meet increased demand by lengthening working time rather than expanding the number of workers, in view of high fixed hiring and firing costs. Workers also choose to work overtime to cover their expenses for housing and private education for their children. The legal framework still has a number of significant loopholes that allow overly long overtime work. First, in practice the maximum work week is often 68 hours, instead of 52 hours, because the Labour Standards Act does not specify whether weekend working hours should be included in the maximum. Secondly, 26 businesses3 currently have no upper limit on overtime work since they are exempted from the provisions on working hours, because they are regarded necessary for the convenience of the public or in consideration of their business characteristics. Around 3.3 million people are employed in these businesses. Finally, provisions on working hours, recess and holidays do not apply to workers engaged in companies with less than five employees or in certain industries such as agriculture, forestry, and fishery.

There have been long and intense debates on the reduction of working hours among trade unions, employers and the government for several years. In September 2015, the tripartite partners had reached an agreement which was included in a package on structural labour market reform but the agreement became invalid when the social partners split up soon afterwards. In autumn 2017, Korea’s new government is putting forward a new proposal which includes most of the previous agreements, including the following:

Weekend work should be considered as overtime; to be implemented gradually, depending on the size of the company. Special overtime work shall be allowed for justifiable reasons (e.g. a rise in orders) and with a written agreement between representatives of the employer and the workers, with an upper limit of 8 hours per week.

The number of businesses that are excluded from the provisions on working hours shall be reduced from the current 26 to 10, and measures to address the long-hour work practice in the 10 excluded occupations shall be identified.

The biggest remaining loophole after acceptance of this reform would be the lacking regulations for micro-businesses. This is critical as almost 40% of all older workers are employed in companies with less than five employees. It will therefore be very important for the tripartite partners to find measures that better regulate work and working time in this part of the labour market.

Lower working hours, however, will also lead to lower incomes. This is problematic for older workers, in view of their low incomes and high levels of poverty. To address this issue, the Korean government introduced a new allowance system for older workers over age 50 beginning in 2016, which compensates 50% of their income loss if they work 32 hours or less per week. This system could be a significant channel not only to promote the reduction of working hours, but also to retain older worker longer at their main job with the wage peak system. It may also give older workers more time for vocational training, which is needed to enhance their productivity. In addition to providing financial support on the reduction of work hours, the government needs to introduce a system which provides older workers with a right to request a reduction in working hours if necessary for health reasons. The combination of a legal right and financial support could lay a solid foundation on facilitating the reduction of working hours for older workers.

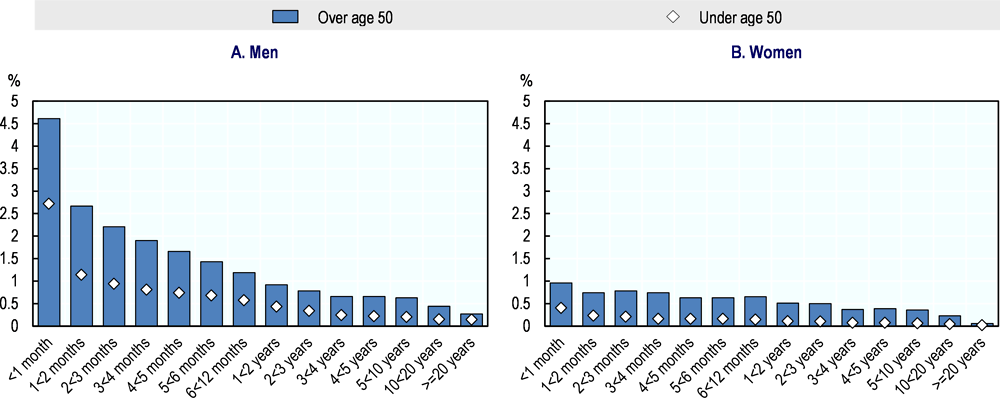

Addressing occupational accidents

High standards of occupational health and safety can help workers remain productive for longer and promote higher labour force participation among older workers. Korea has made progress in reducing occupational accidents and establishing safety regulations and policies through legislation, financial support, education and awareness campaigns. Consequently, the total industrial accident rate has declined substantially from around 4% in the 1970s to around 0.5% in 2013. In 2013, a total of approximately 90 000 workers had an occupational accident.

Three factors strongly determine the rate of occupational accidents: job tenure, gender and age. The majority of occupational accidents happen to older male workers with limited experience on their job. Among men age 50 and over with job tenure of less than one month, the risk of an occupational accident is as high as 4.16% in 2013 whereas for female workers of all ages and for male workers with job tenure over two years, the rate is below 0.5%. With job tenure of more than 20 years, the risk goes down to 0.2% (Figure 3.12). Hence, while employees aged 50 and over are only about one-third of the workforce, they account for more than half of all occupational accidents. Data also indicate that occupational accidents often occur in the transition from the main job to the new job in an unfamiliar environment, which will often be a job that is highly insecure, low paid and more dangerous to work in. Thus, during their second career, older workers often face several different working environments and are exposed to a range of new hazardous work factors. This is further proof of how important it would be to ensure older workers can stay in their core jobs longer, ideally until effective retirement, and – if that is not possible – to help them proactively into better second-career jobs.

Figure 3.12. Occupational accidents are still frequent in Korea in precarious jobs

Source: OSHRI (2014), Issue Report, Occupational Safety and Health Research Institute, Ulsan.

More can be done by the government to improve the working and health conditions of older workers in a rapidly ageing society, going beyond reducing the risk of occupational accidents. Older workers must be made aware of the risk factors in their new jobs and about how to deal with them. Employers must have strong responsibilities and incentives to provide working conditions conducive to their (older) workers’ health and to prevent job strain, occupational diseases and work accidents. They should take workers’ physical and mental health into account when designing overall working environments, including the machinery, working tools, work methods and working hours. The government could establish a system to monitor the health status of (older) workers regularly, in cooperation with local health institutions, especially for those moving in and out of unemployment and insecure employment. In addition, steps should be taken to introduce employer-paid sick leave and a cash sickness benefit, as discussed in detail in OECD (2018a); like the United States but contrary to almost all other OECD countries, Korea lacks statutory or collectively-agreed regulations that address sickness as a major labour market issue.

Conclusion

The high employment rates of older workers in Korea seem to suggest that the country is well prepared for the rapid ageing of its population in the years ahead but this is only partly true. Older workers in Korea often work in jobs of very poor quality and because they have to work to make ends meet. Much has to be done to ensure employability of workers throughout their life and to retain workers in high-quality jobs or bring them back into such jobs in their second career. The challenge in Korea is threefold: to ensure that workers have the skills needed in a fast-changing labour market, throughout life; that those losing a job are helped back quickly into jobs of equal quality; and that working conditions allow workers to work productively for longer.